Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

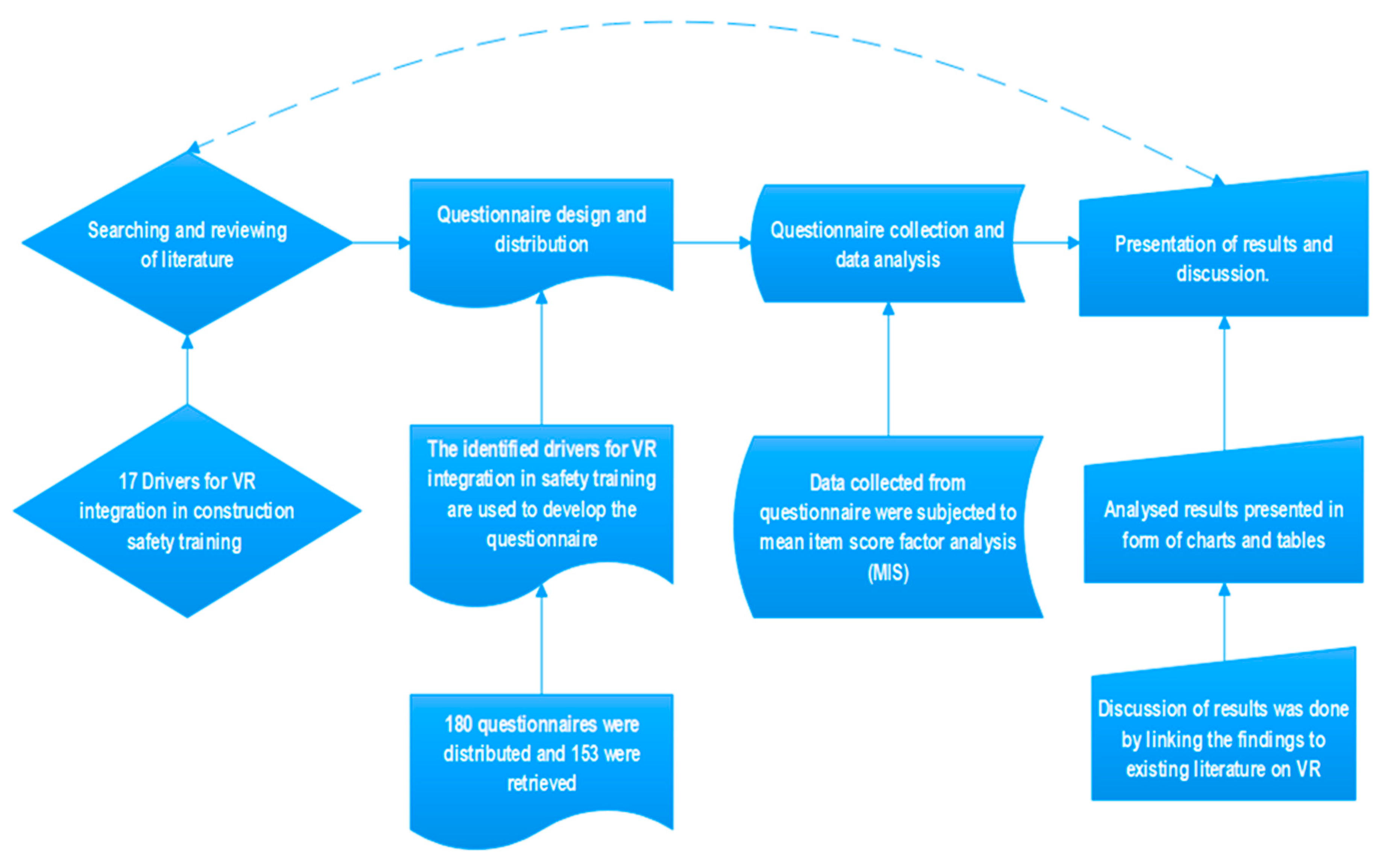

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Respondents

3.2. Ranking Drivers for Virtual Reality Integration in the Construction Industry Safety Training

3.3. Kruskal Wallis (One-Way Analysis of Variance ANOVA) Test in Examining Differences in Respondents' Perceptions of Drivers for VR Integration in Safety Training

3.4. Exploratory Factor Analysis on the Drivers for Virtual Reality Integration in Safety Training Within the Construction Industry

Factor Cluster Report

4. Discussion

4.1. Cluster One - Technological and Safety Enhancements

4.2. Cluster Two - Regulatory and Financial Drivers

4.3. Cluster Three - Customization and Accessibility

4.4. Cluster Four – Operational Efficiency and Risk Management

4.5. Substantial Contributions and Implications

4.6. Practical Implications

- Investment in Technology: The leading position of technological advances means that construction firms need to prioritize investment in cutting-edge VR technologies. This includes the purchase of VR hardware and software, allowing for the creation of realistic, high-quality simulations that can be used to support immersive and safe training exercises. Organizations that continue to be technologically up-to-date will experience improved training outcomes and more effective safety cultures.

- Enhancing Safety Culture: The study highlights the necessity of VR in developing a stronger safety culture within the construction industry. The integration of VR allows companies to promote better safety behaviors by providing immersive training that effectively simulates actual hazards in real-life settings without risking the workers with actual danger. Industry captains need to stress promoting VR as a method of inculcating a safety-first culture across all levels of employees.

- Scalable and Customizable Training Solutions: The ability of VR to provide personalized training experiences based on specific learning needs is of utmost importance. Construction companies should design VR modules addressing the distinctive challenges of different tasks and roles in the industry so that training is current and engaging. In addition, the scalability of VR allows it to be implemented with huge, geographically dispersed teams, making it an ideal solution for companies with dispersed or remote operations.

- Focus on Engagement and Retention: One of the greatest advantages of VR is its potential for increasing engagement and retention of learning content. Businesses must emphasize the experiential capacity of VR as a way of enhancing employee participation, with the effect of enhanced retention and a better workforce. Integrating VR as part of safety training can result in enhanced training systems that are more enjoyable yet simultaneously bring about lasting transformations in labor performance and work safety.

- Collaboration of Industry Players: Industry players such as construction companies, training providers, and technology firms need to collaborate to create quality VR training programs. This can lead to pooled resources, better content creation, and more affordable access to VR equipment for small businesses. Standardization of VR training programs and ensuring alignment with industry requirements through collaboration will make them more effective.

4.7. Recommendations

- Enhance Technological Infrastructure: Construction companies must invest heavily in VR technology to create and enhance their training facilities. These involve buying VR headsets, designing in-house training modules, and entering into collaborations with vendors of VR software to create training programs specific to the industry's needs.

- Creating a Strong Safety Culture Through VR: In order to improve safety measures, businesses must integrate VR into their safety procedures and make it a part of the training process. Simulating real-world dangers in a secure environment, VR enables employees to learn more about safety procedures.

- Tailoring Training for Different Roles: VR's flexibility facilitates the development of customized training to suit the singular needs of varying construction roles. Companies need to develop VR modules tailored to various tasks and skill levels, ensuring that training remains effective and relevant throughout the workforce.

- Collaboration of Industry Players: In order to make VR adoption more convenient, industry players like large building firms, small contractors, and technology providers should collaborate. Mutual sharing of knowledge and resources enables companies to lower the costs associated with integrating VR and develop communal training programs for the benefit of the entire sector.

- Remote Team Accessibility Enhanced: Construction companies can leverage the ability of VR to train remote or distributed teams. Giving employees, wherever they may be located, access to the same top-quality training will improve consistency and raise safety levels across the industry.

5. Conclusions

Appendix A

| Demographic Information | No. of Respondents | % | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional background | |||

| Project manager | 12 | 7.8 | 7.8 |

| Builder | 31 | 20.3 | 28.1 |

| Mason | 8 | 5.2 | 33.3 |

| Electrician | 5 | 3.3 | 36.6 |

| Plumber | 11 | 7.2 | 43.8 |

| Carpenter | 5 | 3.3 | 47.1 |

| Site Supervisor | 32 | 20.9 | 68.0 |

| Contractor | 7 | 4.6 | 72.5 |

| Health and Safety Officer | 7 | 4.6 | 77.1 |

| Site Inspector | 4 | 2.6 | 79.7 |

| Civil Engineer | 14 | 9.2 | 88.9 |

| Architect | 5 | 3.3 | 92.2 |

| Quantity Surveyor | 12 | 7.8 | 100.0 |

| Academic qualification | |||

| BECE | 2 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| WASSCE | 11 | 7.2 | 8.5 |

| BSc Degree | 17 | 11.1 | 19.6 |

| BTECH | 34 | 22.2 | 41.8 |

| Certificate (CTC, EET) | 8 | 5.2 | 47.0 |

| Diploma | 4 | 2.6 | 49.6 |

| Higher National Diploma | 67 | 43.8 | 93.4 |

| Master's Degree | 8 | 5.2 | 98.6 |

| PhD | 2 | 1.3 | 100 |

| Years of Experience | |||

| Less than 1 year | 48 | 31.4 | 31.4 |

| 1-5 years | 72 | 47.1 | 78.4 |

| 6- 10 years | 19 | 12.4 | 90.8 |

| 11-15 years | 5 | 3.3 | 94.1 |

| 16-20 years | 5 | 3.3 | 97.4 |

| More than 20 years | 4 | 2.6 | 100.0 |

Appendix B

| Drivers | DR-1 | DR-2 | DR-3 | DR-4 | DR-5 | DR-6 | DR-7 | DR-8 | DR-9 | DR-10 | DR-11 | DR-12 | DR-13 | DR-14 | DR-15 | DR-16 | DR-17 | |

| Project manager | Rank | 4 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Mean | 86.92 | 67.92 | 93.29 | 86.58 | 86.79 | 79.88 | 92.38 | 90.50 | 97.50 | 88.67 | 80.13 | 91.92 | 81.63 | 81.17 | 91.46 | 95.88 | 82.00 | |

| Builder | Rank | 5 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 9 |

| Mean | 86.68 | 88.60 | 80.27 | 79.76 | 79.32 | 81.68 | 72.61 | 73.55 | 68.31 | 74.23 | 74.60 | 83.29 | 78.97 | 75.74 | 74.82 | 67.47 | 70.87 | |

| Mason | Rank | 7 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 2 | 12 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| Mean | 76.50 | 42.69 | 45.25 | 51.31 | 40.75 | 52.56 | 63.06 | 98.38 | 79.56 | 68.56 | 75.00 | 58.13 | 74.75 | 77.06 | 70.19 | 74.31 | 69.56 | |

| Electrician | Rank | 3 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 6 | 13 | 12 |

| Mean | 90.30 | 56.50 | 64.60 | 95.60 | 105.80 | 67.00 | 90.70 | 77.10 | 67.50 | 78.20 | 87.80 | 67.00 | 65.80 | 70.50 | 82.10 | 62.20 | 67.60 | |

| Plumber | Rank | 2 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 6 |

| Mean | 95.55 | 86.09 | 75.82 | 67.91 | 74.32 | 92.86 | 84.82 | 80.91 | 93..45 | 75.09 | 81.95 | 92.82 | 81.64 | 91.45 | 98.50 | 71.73 | 75.27 | |

| Carpenter | Rank | 11 | 7 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 |

| Mean | 64.20 | 75.30 | 62.20 | 93.30 | 103.90 | 104.70 | 62.60 | 103.20 | 63.10 | 84.40 | 71.00 | 51.80 | 48.20 | 81.30 | 70.90 | 80.70 | 73.70 | |

| Site Supervisor | Rank | 1 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 11 | 7 |

| Mean | 69.44 | 79.19 | 69.80 | 78.39 | 80.64 | 70.53 | 82.27 | 68.59 | 73.64 | 78.95 | 74.66 | 79.41 | 77.41 | 82.53 | 70.64 | 67.17 | 74.38 | |

| Contractor | Rank | 10 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 9 | 13 | 9 | 13 | 12 | 2 |

| Mean | 68.50 | 88.07 | 91.86 | 77.50 | 91.21 | 82.71 | 77.00 | 70.43 | 84.21 | 99.00 | 74.00 | 60.71 | 47.21 | 75.57 | 56.64 | 65.07 | 86.07 | |

| Health and Safety Officer | Rank | 8 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Mean | 74.79 | 94.50 | 112.21 | 62.64 | 77.79 | 98.36 | 108.57 | 88.64 | 119.17 | 84.36 | 97.50 | 105.71 | 97.50 | 70.57 | 89.93 | 104.71 | 86.07 | |

| Site Inspector | Rank | 9 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 9 | 13 | 11 | 11 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 11 |

| Mean | 112.13 | 73.88 | 73.00 | 95.50 | 87.25 | 64.50 | 66.38 | 67.38 | 65.88 | 71.50 | 95.63 | 51.50 | 95.50 | 87.50 | 90.50 | 103.00 | 68.50 | |

| Civil Engineer | Rank | 13 | 11 | 5 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 13 | 11 | 5 | 5 |

| Mean | 56.71 | 64.82 | 82.57 | 65.07 | 54.14 | 55.00 | 48.04 | 70.82 | 60.96 | 73.71 | 56.57 | 54.64 | 69.46 | 58.75 | 69.29 | 80.96 | 80.07 | |

| Architect | Rank | 6 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 13 | 5 | 13 | 9 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 9 | 13 |

| Mean | 81.80 | 89.70 | 91.60 | 87.80 | 81.20 | 93.60 | 47.70 | 87.20 | 68.00 | 42.80 | 103.80 | 72.60 | 103.90 | 92.70 | 66.00 | 70.40 | 67.60 | |

| Quantity Surveyor | Rank | 12 | 10 | 11 | 7 | 11 | 7 | 2 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| Mean | 61.58 | 67.38 | 64.58 | 78.83 | 67.67 | 80.79 | 92.46 | 69.25 | 75.42 | 73.88 | 77.38 | 81.33 | 76.96 | 65.79 | 83.79 | 100.46 | 99.25 |

References

- Onyesolu, M. O., & Eze, F. U. (2011). Understanding virtual reality technology: advances and applications. Adv. Comput. Sci. Eng, 1, 53-70.

- González-Franco, M., & Lanier, J. (2017). Model of illusions and virtual reality. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1125. [CrossRef]

- Dhalmahapatra, K., Maiti, J., & Krishna, O. B. (2021). Assessment of virtual reality-based safety training simulator for electric overhead crane operations. Safety science, 139, 105241. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Guerrero, F., Sanchez, R., & Neira-Tovar, L. (2020, September). Virtual Reality Trainer in the Evaluation of International Safety Standards in Fire Situations. In 2020 IEEE Games, Multimedia, Animation and Multiple Realities Conference (GMAX) (pp. 1-4). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Shi, C., Miao, X., Liu, H., Han, Y., Wang, Y., Gao, W., Liu, G., Li, S., Lin, Y., Wei, X., & Xu, T. (2023). How to promote the sustainable development of virtual reality technology for training in construction filed: A tripartite evolutionary game analysis. Plos one, 18(9), e0290957. [CrossRef]

- Wahidi, M. M., Khan, Y. A., Ong, C. S., & Annabi, M. A. (2022). The role of virtual reality in medical education: A focus on cardiothoracic surgery training. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 14(9), 3488-3499. [CrossRef]

- Nickel, P. E., Lungfiel, A. N., Nischalke-Fehn, G. E., & Trabold, R. J. (2013). A virtual reality pilot study towards elevating work platform safety and usability in accident prevention. Safety Science Monitor, 17(2), 10-17.

- Sacks, R., Perlman, A., & Barak, R. (2013). Construction safety training using immersive virtual reality. Construction Management and Economics, 31(9), 1005-1017. [CrossRef]

- Avveduto, G., Tanca, C., Lorenzini, C., Tecchia, F., Carrozzino, M., & Bergamasco, M. (2017). Safety training using virtual reality: A comparative approach. In Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Computer Graphics: 4th International Conference, AVR 2017, Ugento, Italy, June 12-15, 2017, Proceedings, Part I 4 (pp. 148-163). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D., Wang, X., Liu, J., Li, J., & Tang, W. (2022). Virtual reality safety training using deep EEG-net and physiology data. The visual computer, 38(4), 1195-1207. [CrossRef]

- Pedram, S., Ogie, R., Palmisano, S., Farrelly, M., & Perez, P. (2021). Cost–benefit analysis of virtual reality-based training for emergency rescue workers: a socio-technical systems approach. Virtual Reality, 25(4), 1071-1086. [CrossRef]

- Mossel, A., Peer, A., Göllner, J., & Kaufmann, H. (2015). Requirements analysis on a virtual reality training system for CBRN crisis preparedness. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the ISSS-2015 Berlin, Germany (Vol. 1, No. 1).

- Lawson, G., Salanitri, D., & Waterfield, B. (2015). The future of Virtual Reality in the automotive industry. In VR Processes in the Automotive Industry, 17th International Conference, HCI International 2015, Los Angeles, CA.

- Ghobadi, M., & Sepasgozar, S. M. (2020). An investigation of virtual reality technology adoption in the construction industry (pp. 1-35). London, UK: IntechOpen.

- Smith, J., Jones, A., & Brown, L. (2020). Enhancing Remote Training through Virtual Reality. Journal of Occupational Safety, 15(4), 233-245.

- Johnson, M., & Brown, C. (2021). Virtual reality in healthcare education: A systematic review. Nurse Education Today, 97, 104652.

- Bell, B. S., & Federman, J. E. (2013). E-learning in postsecondary education. The Future of Children, 23(1), 165-185.

- Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2013). Feedback in Higher and Professional Education: Understanding It and Doing It Well. Routledge.

- Chan, S., Huang, Y. M., & Chang, C. S. (2010). A case study on the relationship between computer self-efficacy and behavior intention toward using augmented reality in nursing education. Nurse Education Today, 30(5), 499-505.

- Rosen, M. A., Salas, E., Silvestri, S., Wu, T. S., & Lazzara, E. H. (2008). The role of teamwork in healthcare: Promoting high-reliability and teamwork in healthcare systems. Human Resource Management Review, 18(3), 207-216.

- Smith, J., Jones, A., & Brown, L. (2020). Enhancing Remote Training through Virtual Reality. Journal of Occupational Safety, 15(4), 233-245.

- Johnson, R., & Miller, T. (2021). Virtual Reality in Workplace Safety Training: Bridging the Gap for Remote Teams. International Journal of Safety and Ergonomics, 27(2), 120-130.

- Huang, H., & Liaw, S. (2018). Scaling Up Workplace Safety Training with Virtual Reality. International Journal of Training Research, 16(3), 242-255.

- Patel, K., Jain, M., & Desai, V. (2019). The Economics of VR in Large-Scale Safety Training Programs. Journal of Safety Research, 70, 123-134.

- Rizzo, A., Buckwalter, J. G., & Van der Zaag, C. (2017). Virtual Reality for Training: Current Status and Future Prospects. Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 23(2), 213-229.

- Bruder, R., & Uhl, A. (2019). Simulating High-Risk Scenarios in VR for Safety Training. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 3841.

- Shi, C., Miao, X., Liu, H., Han, Y., Wang, Y., Gao, W., Liu, G., Li, S., Lin, Y., Wei, X., & Xu, T. (2023). How to promote the sustainable development of virtual reality technology for training in construction filed: A tripartite evolutionary game analysis. Plos one, 18(9), e0290957. [CrossRef]

- Wahidi, M. M., Khan, Y. A., Ong, C. S., & Annabi, M. A. (2022). The role of virtual reality in medical education: A focus on cardiothoracic surgery training. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 14(9), 3488-3499. [CrossRef]

- Nickel, P. E., Lungfiel, A. N., Nischalke-Fehn, G. E., & Trabold, R. J. (2013). A virtual reality pilot study towards elevating work platform safety and usability in accident prevention. Safety Science Monitor, 17(2), 10-17.

- Baceviciute, S., Cordoba, A. L., Wismer, P., Jensen, T. V., Klausen, M., & Makransky, G. (2022). Investigating the value of immersive virtual reality tools for organizational training: An applied international study in the biotech industry. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(2), 470-487. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q. L., Tran, S. V. T., Yang, J., Pedro, A., Pham, H. C., & Park, C. (2024). Token incentive framework for virtual-reality-based construction safety training. Automation in Construction, 158, 105167. [CrossRef]

- Mikropoulos, T. A., & Natsis, A. (2011). Educational virtual environments: A ten-year review of empirical research (1999–2009). Computers & Education, 56(3), 769-780. [CrossRef]

- Bell, B. S., & Federman, J. E. (2013). E-learning in postsecondary education. The Future of Children, 23(1), 165-185.

- Rosen, M. A., Salas, E., Silvestri, S., Wu, T. S., & Lazzara, E. H. (2008). The role of teamwork in healthcare: Promoting high-reliability and teamwork in healthcare systems. Human Resource Management Review, 18(3), 207-216.

- Anderson, P., Williams, K., & Thompson, H. (2019). Customizing Safety Training with Virtual Reality. Journal of Occupational Health and Safety, 14(3), 198-210.

- Lee, S., & Kim, J. (2020). Personalized VR Training for Enhanced Workplace Safety. International Journal of Training and Development, 24(1), 45-58.

- Bailenson, J., Yee, N., & Blascovich, J. (2018). The Impact of Virtual Reality on Learning: A Comprehensive Study. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(2), 321-340.

- Fernandez, M. (2019). Enhancing Engagement in Safety Training through VR Gamification. Journal of Workplace Learning, 31(5), 354-370.

- Waller, M., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (2019). Training via Simulation: A Review of Virtual Environments and Their Impact on Skill Acquisition. Simulation & Gaming, 50(5), 607-636.

- Buttussi, F., & Chittaro, L. (2018). Effects of Different Types of Virtual Reality Display on Presence and Learning in a Safety Training Scenario. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 24(2), 1063-1076. [CrossRef]

- Kothgassner, O. D., Felnhofer, A., Hauk, N., Kastenhofer, E., & Kryspin-Exner, I. (2019). The Potential of Virtual Reality for Safety Training in the Construction Sector. Journal of Safety Research, 69, 41-50.

- Dede, C. (2009). Immersive Interfaces for Engagement and Learning. Science, 323(5910), 66-69. [CrossRef]

- Bohle, P., & Quinlan, M. (2020). The Role of Virtual Reality in Enhancing Safety Culture. Safety Science, 127, 104706.

- Lucas, J., Bell, R., & Sutherland, D. (2018). Virtual Reality as a Tool for Improving Safety Culture in the Workplace. Journal of Safety Research, 67, 35-44.

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques (2nd ed.). New Age International Publishers.

- Collins, H. (2010). Creative Research: The Theory and Practice of Research for the Creative Industries. AVA Publishing.

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric Theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Pallant, J. (2016). SPSS Survival Manual (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Aigbavboa, Clinton Ohis, John Edward Cobbina, Simon Ofori Ametepey, and Wellington Didibhuku Thwala. "A Quantitative Study of Sustainable Urban Transformation in Developing Countries: Results from Ghana." In Urban Alchemy: A Governance and Planning Framework for Sustainable Urban Transformation in Developing Economies, pp. 95-154. Emerald Publishing Limited, 2025.

- Kumar, R. (2011). Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- DeVellis, R. F. (2016). Scale Development: Theory and Applications (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- McCormick, K., Salcedo, J., & Poh, A. (2015). SPSS Statistics for Dummies (3rd ed.). Wiley.

- Bohle, P., & Quinlan, M. (2020). The Role of Virtual Reality in Enhancing Safety Culture. Safety Science, 127, 104706.

- Anderson, P., Williams, K., & Thompson, H. (2019). Customizing Safety Training with Virtual Reality. Journal of Occupational Health and Safety, 14(3), 198-210.

| Drivers for VR Integration for Safety Training in the Construction Industry | Authors | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Technological Advancements in industry | Onyesolu & Eze, 2011 [1] |

| 2 | Government/Organizational Regulations and policies | Dhalmahapatra et al., 2022, Torres-Guerrero et al., 2020, Shi et al., 2023, Wahidi et al., 2022 [3,4,27,28] |

| 3 | Under-performance of Safety Statistics (number of injuries to enforce improved training standards) | Nickel et al., 2013, Sacks et al., 2013, Avveduto et al., 2017, Huang et al., 2022 [8,9,10,29] |

| 4 | Cost of Safety Training | Pedram et al., 2021, Avveduto et al., 2017 [9,11] |

| 5 | Stakeholder Pressure | Mossel et al., 2015, Lawson et al., 2015, Ghobadi & Sepasgozar, 2020 [12,13,14] |

| 6 | Competitive Advantage | Baceviciute et al., 2022, Bao et al., 2024 [30,31] |

| 7 | Realistic training environments and high-quality simulations | Smith et al., 2020, Johnson & Brown, 2021, Lee et al., 2019 [16,21] |

| 8 | Risk- free environment as compared to real world training | González-Franco & Lanier, 2017, Mikropoulos & Natsis, 2011 [2,32] |

| 9 | Real-time/immediate training feedback and performance tracking for workers | Bell & Federman, 2013, Boud & Molloy, 2013 [18,33] |

| 10 | Data-Driven Insights | Chan et al., 2010, Rosen et al., 2008 [19,34] |

| 11 | Enhanced Accessibility for Remote or Distributed Teams | Smith et al., 2020; Johnson & Miller, 2021 [21,22] |

| 12 | Customization and Personalization of Training Programs | Anderson et al., 2019, Lee & Kim, 2020 [35,36] |

| 13 | Engagement and Retention of Training Content | Bailenson et al., 2018, Fernandez, 2019 [37,38] |

| 14 | Scalability of Training Programs | Huang & Liaw, 2018; Patel et al., 2019 [23,24] |

| 15 | Reduction in Training Time | Waller & Cannon-Bowers, 2019, Buttussi & Chittaro, 2018, Kothgassner et al., 2019, Dede, 2009 [39,40,41,42] |

| 16 | Simulation of Rare or High-Risk Scenarios | Rizzo et al., 2017, Bruder et al., 2019 [25,26] |

| 17 | Improvement in Safety Culture | Bohle & Quinlan, 2020, Lucas et al., 2018 [43,44] |

| S/N | Drivers for Virtual Reality Integration in Safety Training Within the Construction Industry | Mean | Std. | t-Value (μ = 3.5) | df | Sig.(2-Tailed) | Mean Difference | Rank | Significant (p< 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DR-1 | Technological Advancements in the industry | 4.03 | 0.980 | 6.643 | 152 | .001 | .526 | 1 | Yes |

| DR-17 | Improvement in Safety Culture | 4.03 | 0.903 | 7.208 | 152 | .001 | .526 | 2 | Yes |

| DR-11 | Enhanced Accessibility for Remote or Distributed Teams | 3.86 | 0.877 | 5.026 | 152 | .001 | .356 | 3 | Yes |

| DR-13 | Engagement and Retention of Training Content | 3.84 | 0.904 | 4.695 | 152 | .001 | .343 | 4 | Yes |

| DR-12 | Customization and Personalization of Training Programs | 3.81 | 0.937 | 4.098 | 152 | .001 | .310 | 5 | Yes |

| DR-6 | Competitive Advantage | 3.80 | 0.955 | 3.851 | 152 | .001 | .297 | 6 | Yes |

| DR-8 | Risk-free environment as compared to real-world training | 3.80 | 1.041 | 3.534 | 152 | .001 | .297 | 7 | Yes |

| DR-10 | Data-Driven Insights | 3.78 | 0.966 | 3.640 | 152 | .001 | .284 | 8 | Yes |

| DR-7 | Realistic training environments and high-quality simulations | 3.76 | 0.937 | 3.493 | 152 | .001 | .265 | 9 | Yes |

| DR-14 | Scalability of Training Programs | 3.76 | 0.896 | 3.564 | 152 | .001 | .258 | 10 | Yes |

| DR-9 | Real-time/immediate training feedback and performance tracking for workers | 3.75 | 1.003 | 3.021 | 152 | .003 | .245 | 11 | Yes |

| DR-16 | Simulation of Rare or High-Risk Scenarios | 3.66 | 0.981 | 2.019 | 152 | .045 | .160 | 12 | No |

| DR-4 | Cost of Safety Training | 3.63 | 0.931 | 1.693 | 152 | .092 | .127 | 13 | No |

| DR-15 | Reduction in Training Time | 3.62 | 1.094 | 1.367 | 152 | .174 | .121 | 14 | No |

| DR-3 | Under-performance of Safety Statistics (number of injuries to enforce improved training standards) | 3.61 | 1.040 | 1.361 | 152 | .176 | .114 | 15 | No |

| DR-2 | Government/Organizational Regulations and Policies | 3.56 | 0.979 | .785 | 152 | .434 | .062 | 16 | No |

| DR-5 | Stakeholder Pressure | 3.50 | 1.027 | -.039 | 152 | .969 | -.003 | 17 | No |

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | .872 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 891.894 |

| df | 136 | |

| Sig. | <.001 | |

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 6.061 | 35.654 | 35.654 | 6.061 | 35.654 | 35.654 | 2.808 | 16.520 | 16.520 |

| 2 | 1.280 | 7.529 | 43.183 | 1.280 | 7.529 | 43.183 | 2.583 | 15.196 | 31.716 |

| 3 | 1.197 | 7.041 | 50.224 | 1.197 | 7.041 | 50.224 | 2.462 | 14.481 | 46.198 |

| 4 | 1.114 | 6.555 | 56.780 | 1.114 | 6.555 | 56.780 | 1.799 | 10.582 | 56.780 |

| 5 | .985 | 5.795 | 62.575 | ||||||

| 6 | .945 | 5.559 | 68.134 | ||||||

| 7 | .884 | 5.199 | 73.333 | ||||||

| 8 | .663 | 3.900 | 77.233 | ||||||

| 9 | .617 | 3.630 | 80.863 | ||||||

| 10 | .570 | 3.353 | 84.216 | ||||||

| 11 | .490 | 2.884 | 87.100 | ||||||

| 12 | .453 | 2.666 | 89.766 | ||||||

| 13 | .436 | 2.566 | 92.332 | ||||||

| 14 | .393 | 2.310 | 94.642 | ||||||

| 15 | .333 | 1.958 | 96.600 | ||||||

| 16 | .314 | 1.845 | 98.444 | ||||||

| 17 | .264 | 1.556 | 100.000 | ||||||

| Component | Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Technological and Safety Enhancements (6) | Technological Advancements in the industry | .520 | 0.792 | |||

| Competitive Advantage | .446 | |||||

| Realistic training environments and high-quality simulations | .732 | |||||

| Risk- free environment as compared to real-world training | .654 | |||||

| Real-time/immediate training feedback and performance tracking for workers | .608 | |||||

| Improvement in Safety Culture | .613 | |||||

| Regulatory and Financial Drivers (5) | Government/Organizational Regulations and Policies | .611 | 0.719 | |||

| Under-performance of Safety Statistics (number of injuries to enforce improved training standards) | .506 | |||||

| Cost of Safety Training | .731 | |||||

| Stakeholder Pressure | .791 | |||||

| Data-Driven Insights | .447 | |||||

| Customization and Accessibility (4) | Enhanced Accessibility for Remote or Distributed Teams | .532 | 0.758 | |||

| Customization and Personalization of Training Programs | .659 | |||||

| Engagement and Retention of Training Content | .734 | |||||

| Scalability of Training Programs | .759 | |||||

| Operational Efficiency and Risk Management (2) | Reduction in Training Time | .850 | 0.715 | |||

| Simulation of Rare or High-Risk Scenarios | .758 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).