Introduction

There are many obstacles that Industry 4.0 brings for manufacturing firms and their employees. In order to adjust to the ever-changing landscape of manufacturing technology and production settings, creative and practical training approaches are crucial [

1]. Workers in the industry play a vital role in its development. They shape the direction of the industry and meet the public demands. The ideal organization is operated by flawless workers for sustainable operations to be executed. It has been challenging for the industry to get a highly-trained workforce [

2]. Many businesses have suggested using immersive virtual reality (VR)-based training to help employees become more adept at identifying hazards and modifying risky behavior.

On the other hand, not much is known about how VR-based training affects user behavior and learning [

3]. Organizations spend millions of dollars annually to train employees-. Employees should be trained in health, security, machine usage, and other duties. This issue is so critical that it is significantly costly for an organization to lose highly skilled employees [

4]. Arranging training sessions, buying training equipment, and maintaining damage tolerance consume vast amounts of funds from the organization. Traditional training has used expensive actual equipment, running the risk of damage and injury, wear and tear being accounted for [

5]. The widespread use of virtual simulators in employee cognitive training can improve productivity, accuracy, economy, and efficiency of training and manufacturing [

6]. Therefore, the VR Training and Maintenance System (VRTMS) is an innovative training tool for staff working in sensitive and strategic environments.

Belen Jiménez et al. [

7] used digital 3D models of cultural heritage sites, using Unity 3D, as a prerequisite to the essential VR technology for its preservation. Gabriela et al. [

8] used prototype modeling for an efficient and safe workspace to identify and correct design flaws before actual construction. In our work, we modeled a prototype infrared computer tomography (CT) machine [

9,

10] and designed a workspace fed into the Unity engine.

Consumers' VR headsets were released to the public by the 1990s, though the first concept was revealed to the world in 1935 by American science fiction writer Stanley Weinbaum [

11]. This has revolutionized the world, giving an experience never imagined. This industry got so much promotion that with time, it started being used in factories, medical, and other industries, in addition to being used for entertainment [

12].

VR systems have proved to be significantly efficient for education purposes. They have given students an immersive experience of exploring the system in a virtual space [

13]. Students may control the components, observe the product on the proper scale, and better explore it from various angles by utilizing head-mounted devices (HMDs) to experience the VR application, which recreates an immersive environment [

14].

Daling and Schlittmeier [

15] reviewed that traditional training techniques are expensive, involving the maintenance cost of simulated equipment, face-to-face sessions, and the risk of damage to expensive lab equipment. VR has recently gathered significant interest as a tool that surpasses the limitations of traditional approaches by offering chances for novel encounters devoid of temporal or spatial restrictions while guaranteeing a secure educational setting [

16]. Further, Bulu [

17] investigated the trainee experience of co-presence with the virtual entities in the VR system to be aware that other individuals were present and perceived us.

Xie et al. [

18] discussed numerous training applications in the development of VR technology, viz., medical training [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], workforce training [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], and military training [

29,

30,

31,

32]. In this context, VR technology allows users to interact with a computer-simulated environment. In the past, the SARSCoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic made VR a beneficial substitute [

33]. VR applications offer a safe, affordable, and controlled environment where staff can practice with virtual tools, mimicking scenarios that could happen in the real world. This technology enhances learning by enabling medical practitioners, engineers, and technicians to develop technical skills and build confidence through risk-free experimentation. This allows them to learn from mistakes without causing harm or damage. With technology, VR can also imitate the haptic, olfactory, kinesthetic, and aural senses [

34].

According to Hernandez-de-Menendez et al. [

35], conventional training programs usually require high investments in infrastructure, including specialized laboratories and state-of-the-art technological equipment. Interpersonal skills are traditionally taught through role-playing. Participants receive performance feedback (e.g., by watching their recordings, receiving comments from peers or instructors, or giving a brief presentation in front of other trainees) and encounter certain social settings [

36]. VR technology was initially used in educational science and showed promising results [

37,

38]. The effect of virtual teachers has also been explored by [

39].

Much research was conducted on using various concepts to support this new technology in industrial training settings. While some have succeeded, others still require development [

40]. Advances in research have proffered enhanced quality and affordability for VR systems. Hardware and software costs for VR have been reduced, making it more available to most businesses and institutions [

41]. These advances have also elevated immersion and realism in the VR training environment, making it more and more effective for learning or training purposes. Therefore, VR systems increasingly offer the attraction missing in the training systems for others, both with immersion and interactivity. The industrial assembly must keep up with the most recent advancements in automation, complexity, and industrial trends. Mass customization has replaced mass production as the dominant industrial trend [

42]. Good training is expected to seek to instill the appropriate skills and decision-making in trainees that they would need in the field rather than guide them directly [

43]. Information should be presented in a clear, manageable format and pace for successful learning to maintain learner engagement. The effectiveness of immersive VR assembly training depends on various factors, including individual differences, didactic concepts, visual rendering quality, and documentation quality [

44].

Virtual and augmented realities offer immersive, contextual visualization, enhancing learning outcomes through interactive engagement. This approach creates a sense of presence and relevance, making learning environments more authentic and engaging. By situating learning in an immersive setting, students learn meaningfully, retain information better, and apply it more effectively [

45]. Where there is Augmented and Virtual Reality (AVR) experiential learning, the development of deeply immersed learning is deepened with learners thrown into interactive virtual environments. Research within the AVR training skills assessment model proves that developing skills and knowledge is expected to be practical.

Over and above, there are many obstacles that Industry 4.0 brings for manufacturing firms and their employees. Ulmer et al. [

1] introduced a novel idea for flexible assembly related to an industrial problem and its evaluation strategy. Workers are crucial to shaping the industry's direction and meeting demands, but securing a highly skilled workforce has been a persistent challenge [

2,

46]. Further, Boden et al. [

47] provided the potential for immersive and interactive learning experiences that can significantly enhance the training process on the application of manufacturing and logistics procedures. Fitz-Enz [

4] disclosed that companies invest heavily in training employees in health, safety, and machine operation, as losing skilled workers is costly. MacLeod [

5] has described that traditional training methods rely on expensive, damage-prone equipment, while virtual simulators enhance productivity, accuracy, and efficiency. Our VRTMS offers an innovative, cost-effective solution for training staff in sensitive environments.

Using computer graphics (CG) to build realistic and aesthetically appealing virtual environments increases user immersion and improves the quality of the training experience [

48]. We have designed a visually appealing environment for our virtual workplace that grabs the user’s attention and motivates them to interact with the system more efficiently. Through the use of proper lighting and shaders, we are able to render fine details of the hardware, providing maximum information to the user.

In addition to all the above, with VR, data can be gathered about how long a task takes to finish, how far it needs to go, whether there are any ergonomic hazards (like bad body posture), and how well a layout works. The highly skilled workforce and data are critical to maximizing technology investments and ensuring efficient and effective outcomes for educational institutions, industries, governments, and communities [

46]. The theory postulates that working memory has limited capacity; for effective learning, the incoming information must be integrated with prior knowledge to create long-term memory schemas. It also accounts for things like aging and aids in designing instructional methods that conform to cognitive limitations for better learning outcomes [

49].

Research has indicated that training using simulation, mainly when using simulators, can efficiently teach technical and non-technical skills together. The dynamic learning environment is also highly cognitively and emotionally engaging and can directly influence what students learn [

50,

51]. VR applications enable users to perceive and modify the world as accurate, simulating physical things in realistic surroundings. VR has improved the cognitive performance of the subjects under training. The dynamic learning environment is also highly engaging both cognitively and emotionally and can directly influence what students learn [

51,

52]. It also accounts for things like aging and aids in designing instructional methods that conform to cognitive limitations for better learning outcomes [

49]. According to Bloom's Taxonomy, cognitive learning is an individual's ability to remember and utilize previously learned information. The rise in mental-intensive professional activities has consequently fueled the growth of cognitive ergonomics, which has important implications for planning and evaluating training programs. Its goal is to enhance cognitive function in dynamic, technologically advanced environments by designing supportive systems and comprehending the basic ideas behind human behavior as they relate to engineering design and development[

53]. Cognitive and psychomotor training enhances cognitive function and motor skills in young and older adults, improving performance and maintaining functional abilities, especially as aging impacts task execution effectiveness [

54]. VR technology allows users to interact with a computer-simulated environment. VR applications enable users to perceive and modify the world as accurate, simulating tangible things in believable surroundings [

55].

Using VR for an assembly simulation enables employees to receive training at a reasonable cost. To prevent undesirable training effects in these assembly simulations, however, the training content must be as realistic as feasible [

56]. VR training helps alleviate these problems by offering lower-cost alternatives with minimal logistical and financial burdens and minimal equipment wear. Traditional training challenges can be lifted now that VR technology has finally arrived. VR negates the need for expensive hardware and maintenance to create immersive simulations on-demand where trainees can practice with virtual tools and devices that simulate real-world equipment [

57].

On the other hand, VR technology was relatively expensive in past times, making it barely applicable to most training settings. For most of the fifty years that have passed, VR technology has mainly been used by military organizations and big research agencies that could afford its costs [

58]. Early adopters have applied VR to quite specific and complex simulation training needs where the capability to create a controlled environment is an advantage. However, its high cost has prevented its wide diffusion across industries, thwarting its growth as a mainstream tool for training. VR is believed to close the gap between the user and the experience since it presents the knowledge more realistically or more closely than traditional learning materials like books or films [

59].

This study aims to design and develop a cognitive interactable system for training, assembly, and disassembling machines in the VR ecosystem. The product is user-friendly and provides an essential toolkit for assembling and disassembling classified machines. The system provides tasks for users to perform and evaluate the performance. The system is aided by the guidance system, which guides the user throughout the session to perform the tasks in the sequence. We focused on the Prototype Infrared Computed Tomography (PI-CT) machine for research purposes, demonstrating the system’s effectiveness in industrial training contexts. The proposed framework allows users to practice it in a virtual environment, minimizing the risks and costs associated with using physical equipment for training. By offering an immersive, interactive experience, the system improves technical skills and enhances cognitive performance as trainees engage with the material more meaningfully. The key contributions of this study may be given by:

It introduces an optimized methodology for training engineers in machine assembly/disassembly, mitigating risks to physical equipment. The research addresses the limitations of conventional training approaches by using VR to deliver an immersive and interactive training experience.

The developed tool enhances cognitive performance, equipping trainees to proficiently operate on actual hardware in production environments.

A comprehensive evaluation system is incorporated to assess trainee performance. It features a leaderboard that ranks participants based on completion time and error frequency metrics.

This study proposes a cost-effective framework for training personnel in industrial assembly tasks.

The paper is organized as follows: The Materials and Methods section outlines the assembly procedure for the PI-CT machine, including model design, graphic quality, optimization, and VR-assisted assembly. The Results and Discussion section presents the findings and analyses, leading to the Conclusions section, which summarizes the key takeaways.

3. Results and Discussion

We developed software that uses VR to train engineers to assemble hardware for several machines. The project is robust to this kind of machine, but we specify the assembly of the PI-CT machine as the reference. The project tracks the performance of the engineers and benchmarks each engineer based on how long it took him to complete the tasks and the number of errors he made. We provide an overall immersive user experience that engages the users to get hands-on training on engineering problems and efficiently train at minimal cost to the organization.

3.1. System Interaction

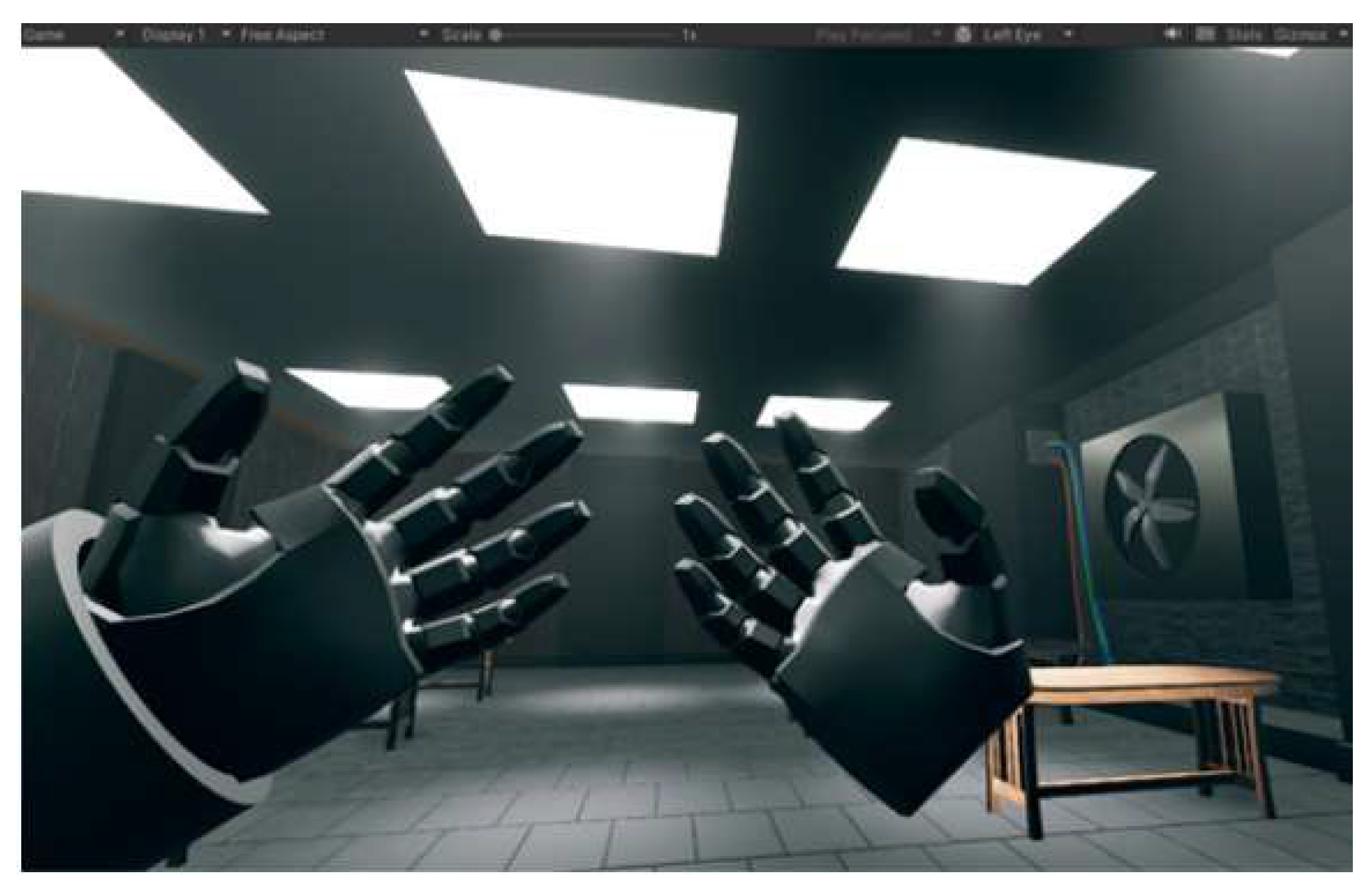

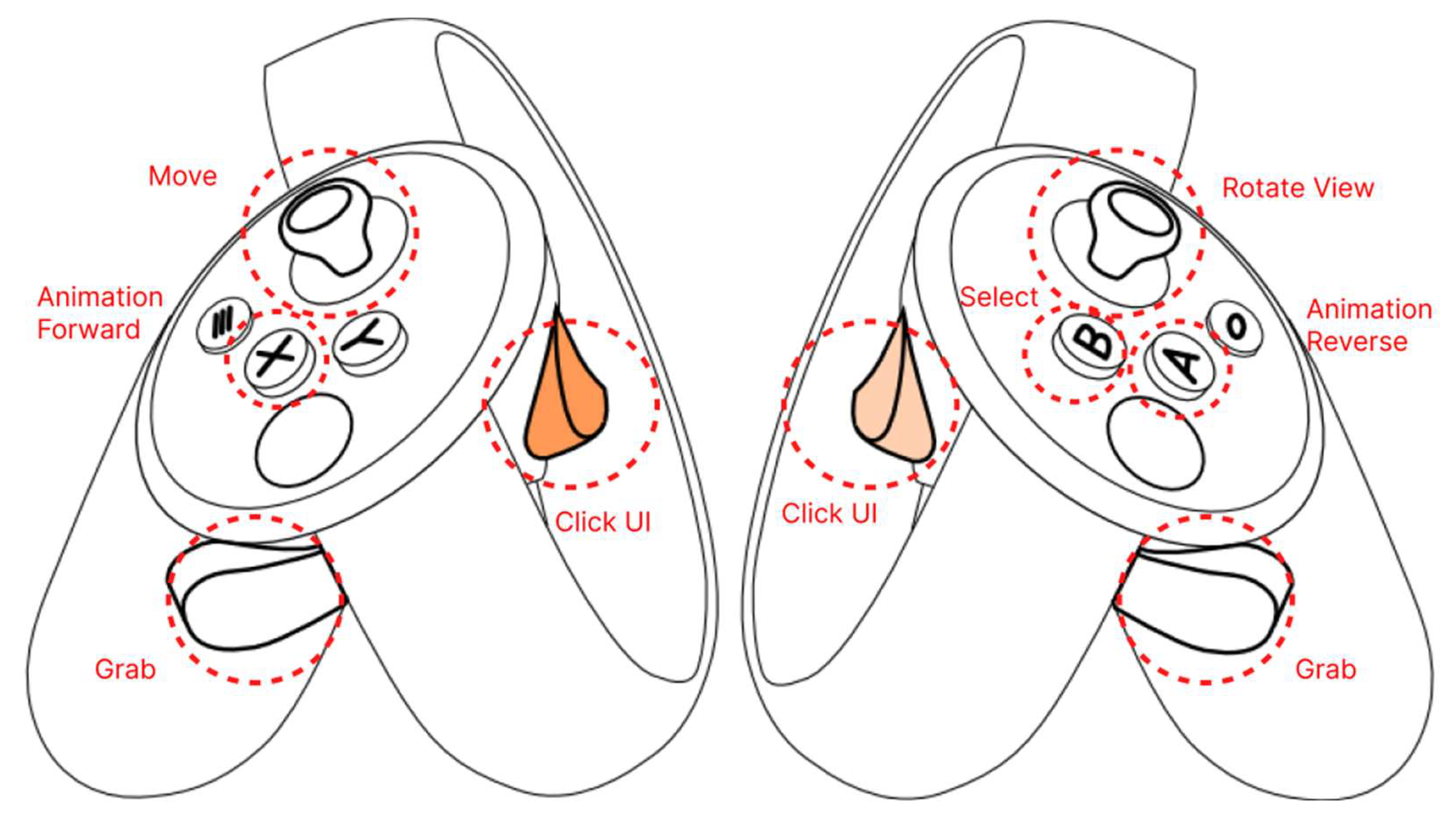

The highly interactive system provides a professional toolkit for assembling the machine. All components in the machines are separate entities, and physics is simulated to reflect the essential attributes of the digital twin. The software simulates the player with IK-powered hands that can be controlled through the touch controllers, as described in

Figure 17.

The user controls through a touch controller; VR hardware includes two of them, each for one hand, and each controller controls the respective hand in the software. These touch controllers take the spatial information and simulate the hands accordingly in the scene, e.g., if the user raises the right hand, the right hand is expected to be raised in the software. Each touch controller is bundled with buttons, triggers, and joysticks for creating events like holding, moving, and rotating. It can easily be observed using

Figure 17 that the left-hand controller is responsible for the user's movement, while the right-hand controller is responsible for rotation. If the player's hand overlaps the interactable object in the scene, and the grab trigger is held, the Grab event is expected to be called, and that respective hand is expected to pick the object. The front trigger of touch controllers is responsible for simulating the finger; its role is to interact with UI elements of the interactable scene.

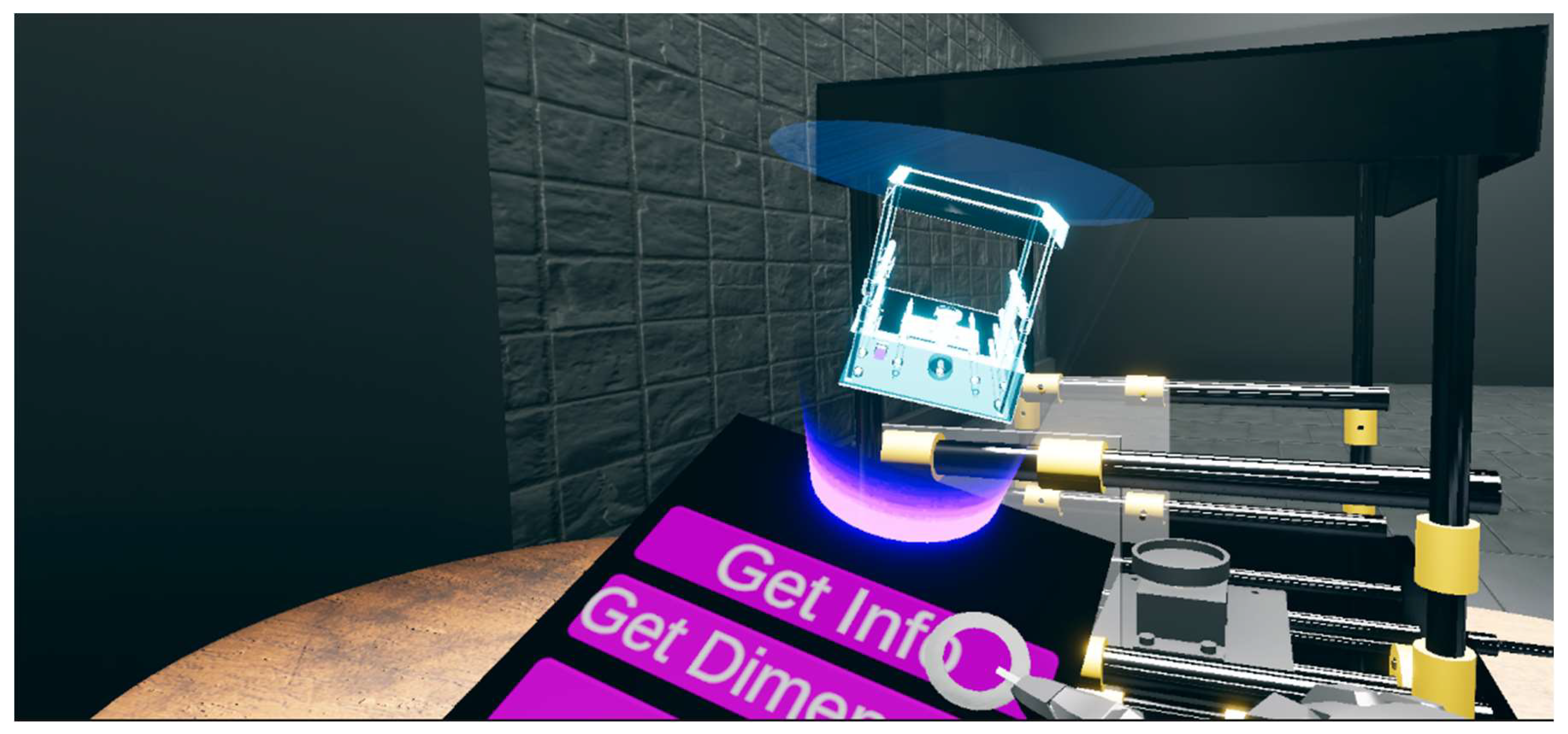

Using modern HCI techniques, we have designed a panel that demonstrates the general information of each component of the user's interest.

Figure 18 demonstrates the GUI interaction with the components to understand their core properties and functions. It provides general information like its dimension and its role in the system's component design.

3.2. User Objectives

After demonstrating expertise in managing the virtual components and familiarizing themselves with the fundamental mechanics of the software, the user is given particular tasks to do. A thorough Objective System is integrated into the software, forming the basis of its training and assessment procedures. This system gives users well-defined objectives, evaluates their real-time performance, and monitors their advancement through significant assignments. The software's performance is assessed in a variety of ways. Along with monitoring the user's general progress, it also logs essential metrics such as the time needed to finish jobs and the number of mistakes made during assembly. Using these indicators, users can receive feedback on their overall performance, accuracy, and efficiency.

The Objective System has an integrated Progress Tracking System that shows users how far they have come. The progress meter is updated dynamically when the user completes each objective, ranging from 0% to 100%. When a user reaches 100% progress, they indicate that all goals have been successfully fulfilled. At this stage, the software considers the user's productivity and the time needed to finish the assembly to create an overall evaluation.

The software also includes a robust leaderboard system that tracks and scores the performance of users interacting with the system. Key performance indicators, like the time needed to do a task and the number of mistakes made during assembly, are used to evaluate each user's performance. This creates a competitive and exciting learning environment. These performance indicators are saved and presented in a scoreboard format. Users are motivated to improve their performance by the leaderboard, which lets them assess their abilities compared to others.

Further, five people tried the software in an experimental context.

Table 2 illustrates how their performance was assessed using two primary metrics: the total number of errors committed throughout the procedure and the time required to finish the assembly. The data gathered from these users was examined to evaluate the efficacy of the Objective System and Progress Tracking System, which improved the software's capacity to produce precise and insightful evaluations.

This careful approach to performance monitoring, task-based learning, and user assessment highlights the software's worth as an effective virtual training tool for complex machine assembly. In addition to making practical learning more accessible, it gives users the tools they need to improve, thanks to organized feedback and a dynamic, performance-driven environment. The software uses the experiment results to collect and store comprehensive data on each user's productivity and cognitive behavior, giving essential insights into how they performed during the machine assembly process. This information is safely kept in the company database, enabling continuous examination and assessment of employees' cognitive abilities.

The software creates an extensive profile of each user's performance under different settings by tracking essential parameters, including task completion time, mistake count, and overall efficiency. This information is essential for comprehending how various workers approach solving problems, adhere to guidelines, and control mental strain when completing challenging jobs in a virtual setting. The data the business has stored can be used for several analytical purposes. For example, it is possible to spot trends in an employee's performance, which can be employed to identify people who could be particularly good at one thing or need more training in another. The organization can evaluate employees' capacity to follow specific procedures, adjust rapidly to new problems, and handle pressure using cognitive behavior analysis. Organizations can identify workers with high mental and technical capabilities who are qualified for more advanced tasks using this information, which can be extremely helpful for talent management.

Furthermore, the information might be utilized for long-term staff development and advancement evaluations. Organizations can monitor learning curves, gauge the value of extra training, and gauge the overall efficacy of the virtual training program by comparing results over several sessions. Aside from helping to customize upcoming training programs and guarantee that workers receive targeted support when required, trends and anomalies in cognitive performance data can also aid in maximizing both individual and team performance. Significant strategic advantages can be gained by storing and analyzing this performance data at the organizational level. It makes it possible to take a data-driven approach to workforce development and ensure that workers are sufficiently ready to put their training to use in the real world. Organizations may uphold high-performance standards, guarantee adherence to procedures, and improve their staff's productivity and efficiency by regularly assessing cognitive behavior. Thus, the software's integrated data gathering and analysis features go beyond the context of the current training program to facilitate long-term staff development and foster a continuous improvement culture.

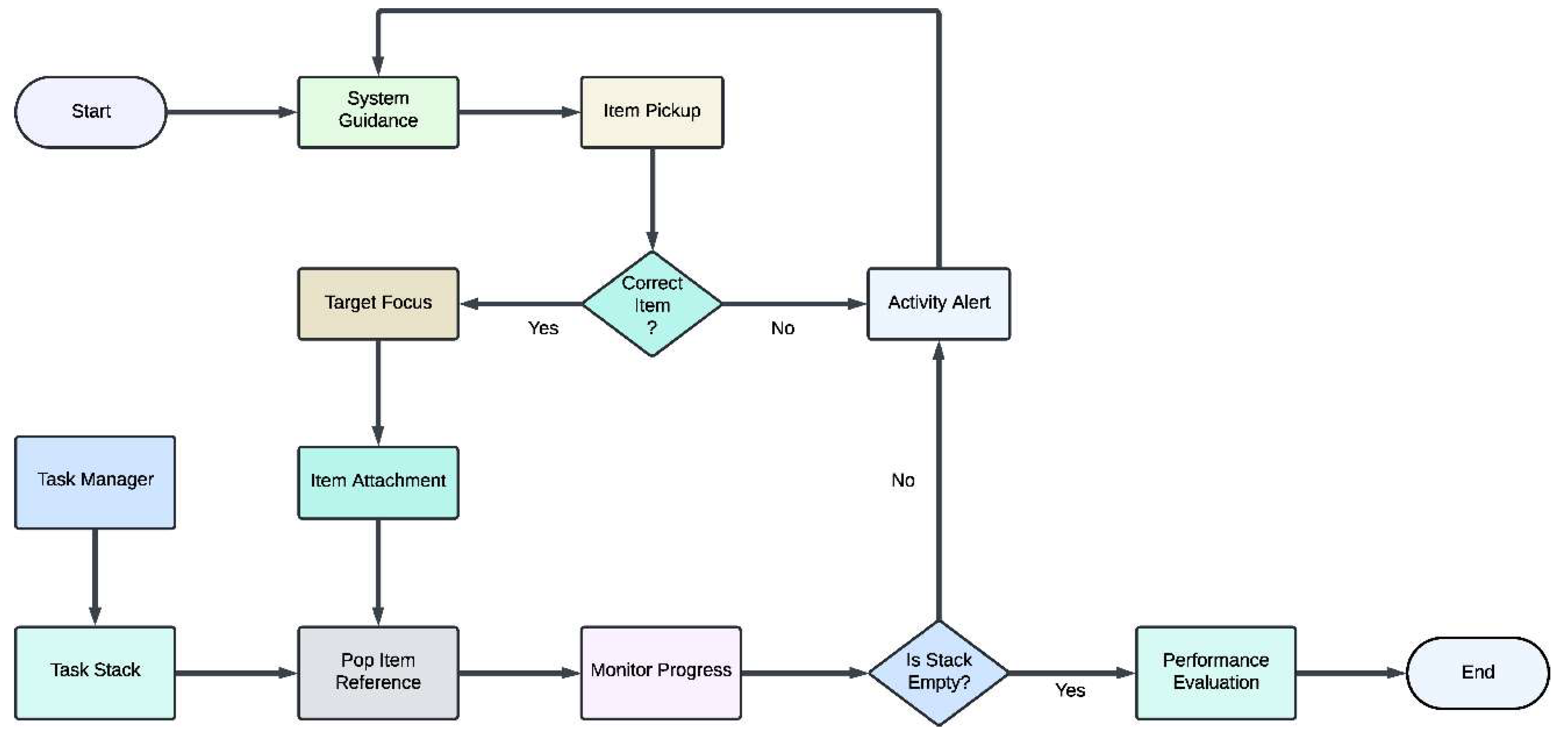

Figure 19 shows the whole training workflow from the very start of the session to its end. Once the session has started, it will walk the trainees through goals by informing them which components to click on and which order to follow. If a trainee does something out of order, the system will pause briefly and make the trainee comply before continuing. Once an objective has been achieved, it is removed from the queue and replaced with another. This process continues until all goals have been achieved to mark the end of the assembly process. Upon completion of the session, the trainee will be evaluated in terms of time, accuracy, and precision in execution.

The user's progress is tracked, and his performance can be evaluated once he has completed the assembly.

Figure 20 illustrates the final assembly of the PI-CT machine after placing all components in the target destination. The user can now get the general information of the system. This assembly precisely reflects the assembly of a PI-CT machine.

3.3. Assistance System

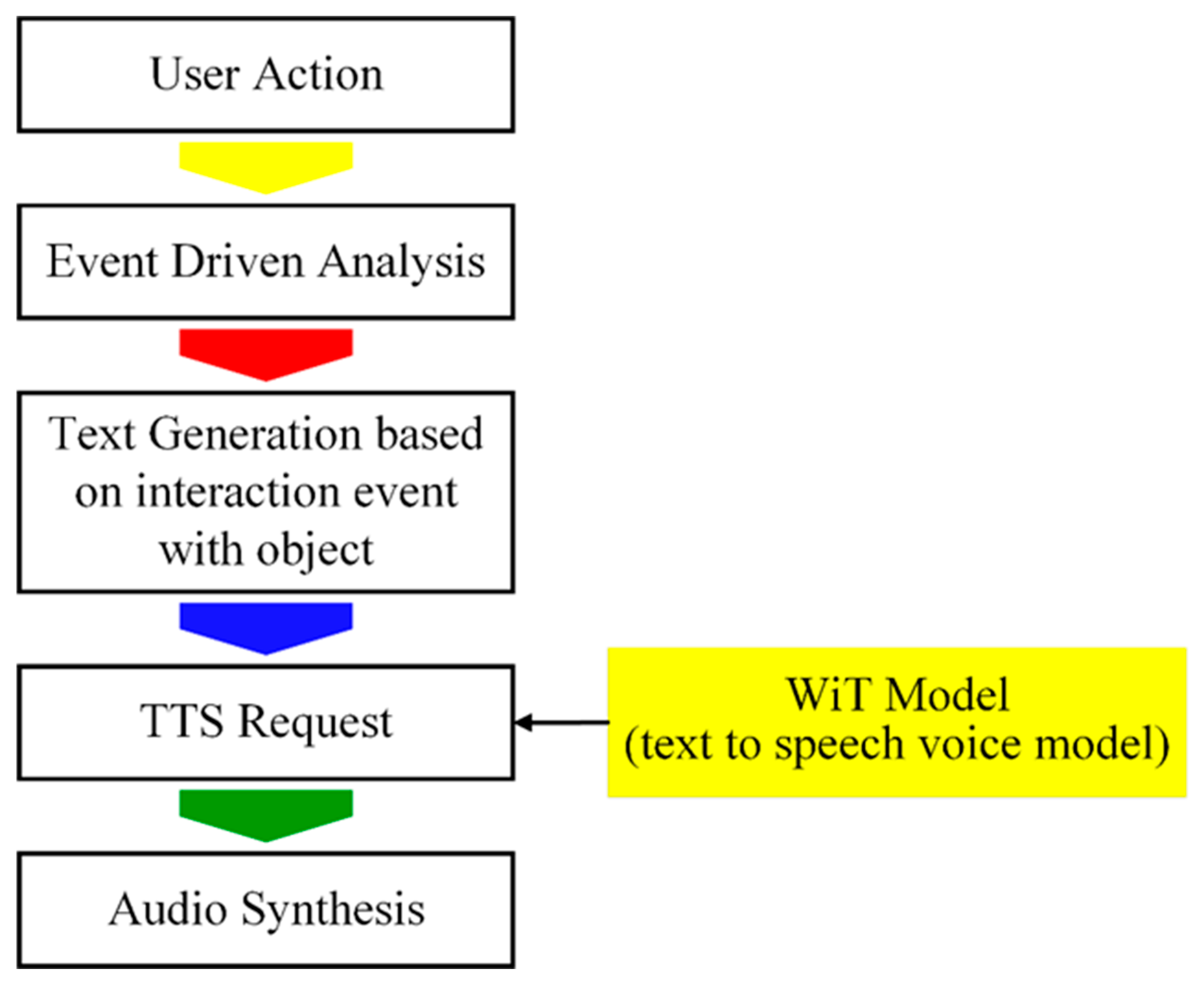

The program has a sophisticated help system that guides users through the real-time engagement stage. This method ensures that users can accomplish tasks precisely and effectively, especially in complicated machine assembly. The speech agent, which gives users precise, step-by-step directions to help them stay on task and complete tasks correctly, is an essential part of this aid system. To provide an interactive learning environment, the speech agent gives instructions, suggestions, and corrections while continuously monitoring the user's progress. This voice-guided system utilizes the Oculus Voice SDK built into Unity and takes advantage of cutting-edge text-to-speech (TTS) technology. A powerful TTS engine powers the voice agent, translating software-generated instructional text into smooth, natural English speech. The system's voice agent offers a smooth user experience by giving conversational and engaging instructions, improving user focus, and lowering cognitive burden.

The system is also flexible and scalable, so when new exercises or training modules are added, the speech agent may be trained to deliver the most recent instructions, keeping the training material current and applicable. This makes it an effective tool for long-term training applications, especially in settings where accuracy and attention to detail are crucial.

Figure 21 illustrates how user actions within the system influence the text-to-speech process. User Action: In this step, the user engages with the program or takes particular activities in the surrounding environment. After that, the user's activities are forwarded to the Analysis step, where the game manager assesses them to ascertain the proper reaction or educational feedback. The system proceeds to the Text Generation stage after the analysis is finished. Here, the system creates the appropriate language, which represents the instructions or feedback expected to be sent to the user based on the analysis's findings. Following the completion of the request processing stage by the TTS engine, the audio synthesis stage is when the synthesized speech output is produced and sent back to the user as audio feedback. This guarantees that users get voice-based, in-the-moment guidance directly related to what they do within the program.

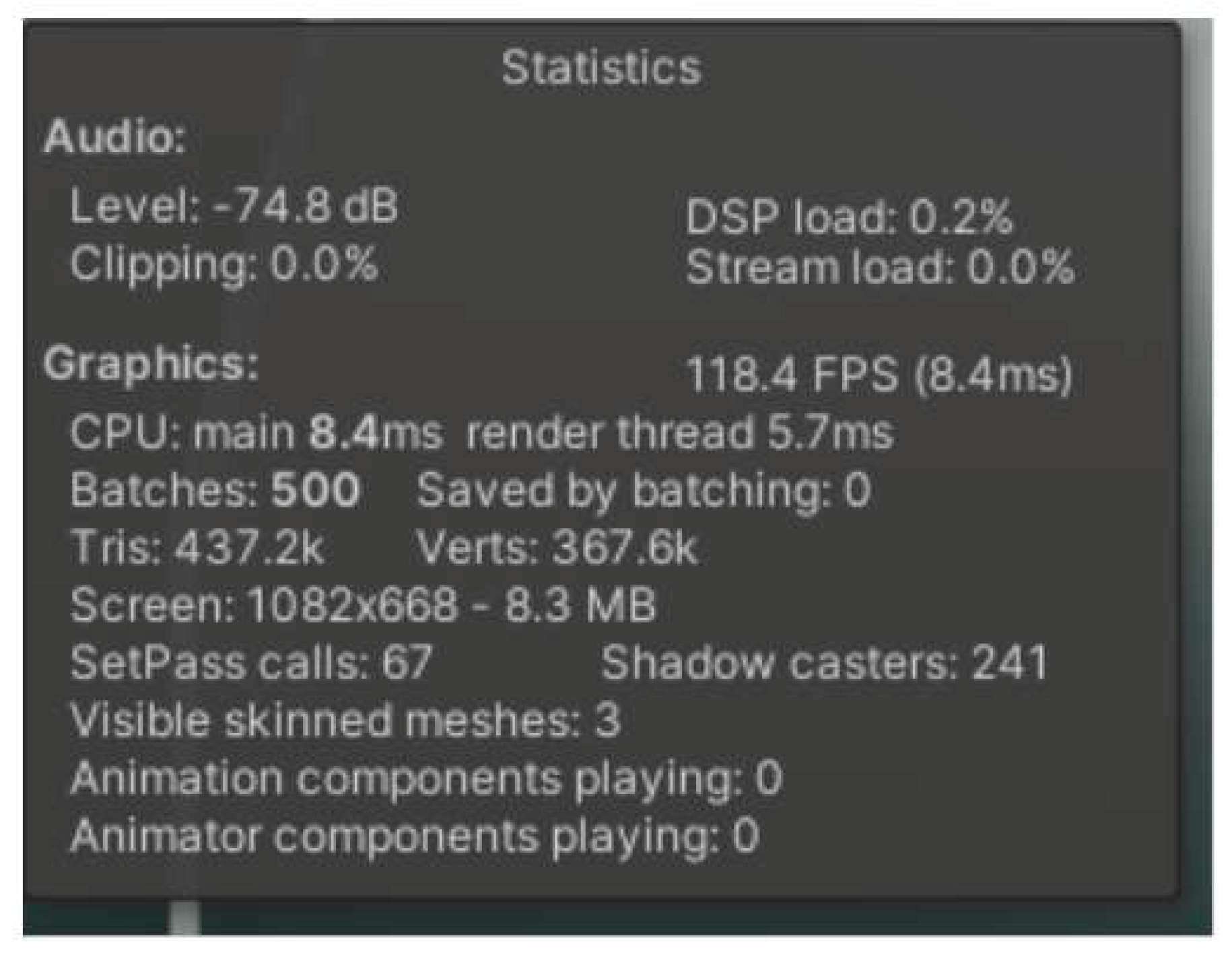

3.4. Performance improvements using DLSS

We have utilized Deep Learning Super Sampling (DLSS) in this research. This algorithm, proposed by Nvidia, uses AI to upscale low-quality to high-quality frames. Generally, GPU computes low-resolution frames more efficiently than high-resolution frames, giving a better frame rate but compromising the quality. DLSS enables us to convert these low-resolution frames into high resolution without much throttling the performance, as modern Nvidia GPUs have specific DLSS cores specially designed for this job in parallel. Combining these optimizations allows the simulator to provide a smooth and immersive experience at an impressive 118 FPS, even on demanding scenes, as shown in

Figure 22. This robust hardware foundation, coupled with intelligent optimization strategies, ensures that the simulator can handle the complex visual requirements of the PI-CT machine assembly process while providing a seamless user experience. We can observe that the CPU latency is 8.4 ms, with a 500 batch count, and the scene is flooded with 437k tris. By utilizing the performance enhancement from DLSS, we are witnessing a significant increase in performance.

DLSS has significantly improved project performance and reduced hardware usage, providing a safe user experience on low-end devices with minimal compromise on quality. We have run various tests to benchmark performance before and after applying DLSS. We used the Speed Fan application, which gives information about hardware usage as described in

Table 3. We can figure out the less utilization of hardware when DLSS is enabled, which has significantly increased FPS and reduced the hardware temperature, boosting its longevity.

DLSS has significantly improved project performance and reduced hardware usage, providing a safe user experience on low-end devices with minimal compromise on quality. We have run various tests to benchmark performance before and after applying DLSS. We can figure out the less utilization of hardware when DLSS is enabled, which has significantly increased FPS and reduced the hardware temperature, boosting its longevity.

3.5. Main Findings

The main findings of this work may be summarized as follows: (1) The work developed here is an efficient and cost-effective VR training solution. It primarily targets the empowerment of engineers to assemble and maintain very complex machinery. Thus, immersive VR technology considerably minimizes the required number of training sessions in actual physical interactions, saving associated time and logistical challenges. It is highly accurate and engaging but scalable for traditional training approaches. (2) One of the significant characteristics of the system is that it offers a completely interactive environment through which users can very conveniently assemble and disassemble. The VR platform simulates real-world conditions that allow hands-on experience in an entity with well-controlled conditions. It is highly interactive and thus promotes an intuitive understanding of machine structure and behavior, and it helps learners develop skills needed to handle actual components in a production environment. The modularity of this system relies on the potential for realism in a training simulation by making it look like actual machinery. (3) The system uses the latest graphical rendering technology: NVIDIA's Deep Learning Super Sampling (DLSS) provides attractive graphics while maintaining performance. The system can support smooth and immersive interactions with high frame rates and greater visual fidelity, even on hardware with limited computational power. Using DLSS allows the system to use much greater visual fidelity more extensively, reduces latency, and enhances the responsiveness of the virtual environment in general. (4) Other than providing a functional setting for training, the system includes an advanced framework for monitoring and assessing the trainee's performance. This framework would track completion and error rates while simultaneously tracking cognitive behavior by the trainee, offering insight into how much the trainee comprehends the machine and their ability to perform complex operations. Through this learning, the system provides personalized feedback for learners to improve their performance and achieve competency levels before interacting with physical machines.

Our research is based on modern Human-Computer Interaction techniques. We offer an intuitive and responsive system with quality training outcomes that require a minimum of a physical trainer, thus saving time, cost, and energy. Besides, our VR training system provides the user with in-depth knowledge of machinery and helps enhance his ability to handle the physical machine effectively once he is placed in the production environment.

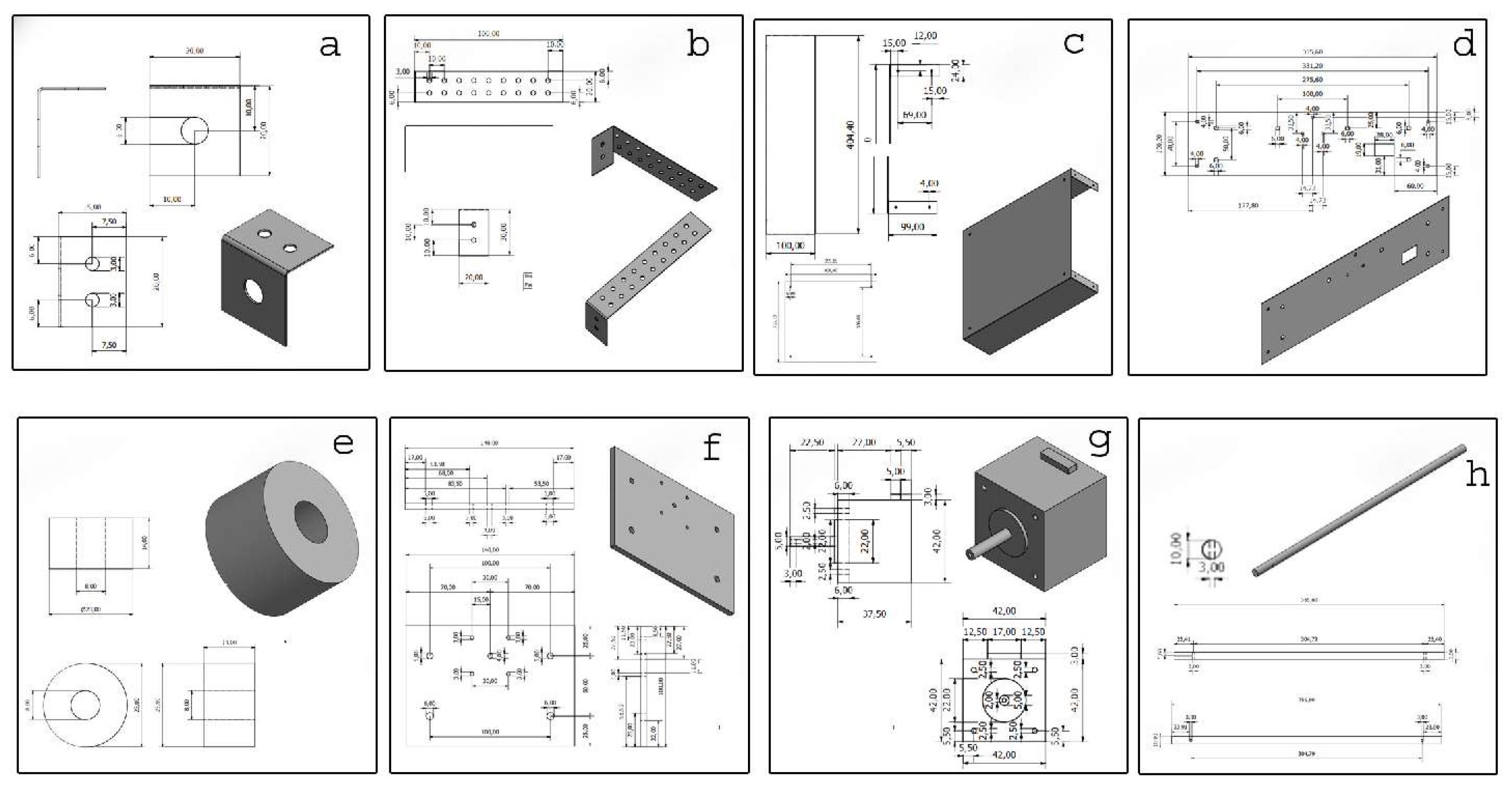

Figure 1.

Engineering drawings and 3D models: (a) l-bracket, (b) long bracket, (c) u-channel, (d) flat plate, (e) washer, (f) plate, (g) stepper motor, and (h) thin rod.

Figure 1.

Engineering drawings and 3D models: (a) l-bracket, (b) long bracket, (c) u-channel, (d) flat plate, (e) washer, (f) plate, (g) stepper motor, and (h) thin rod.

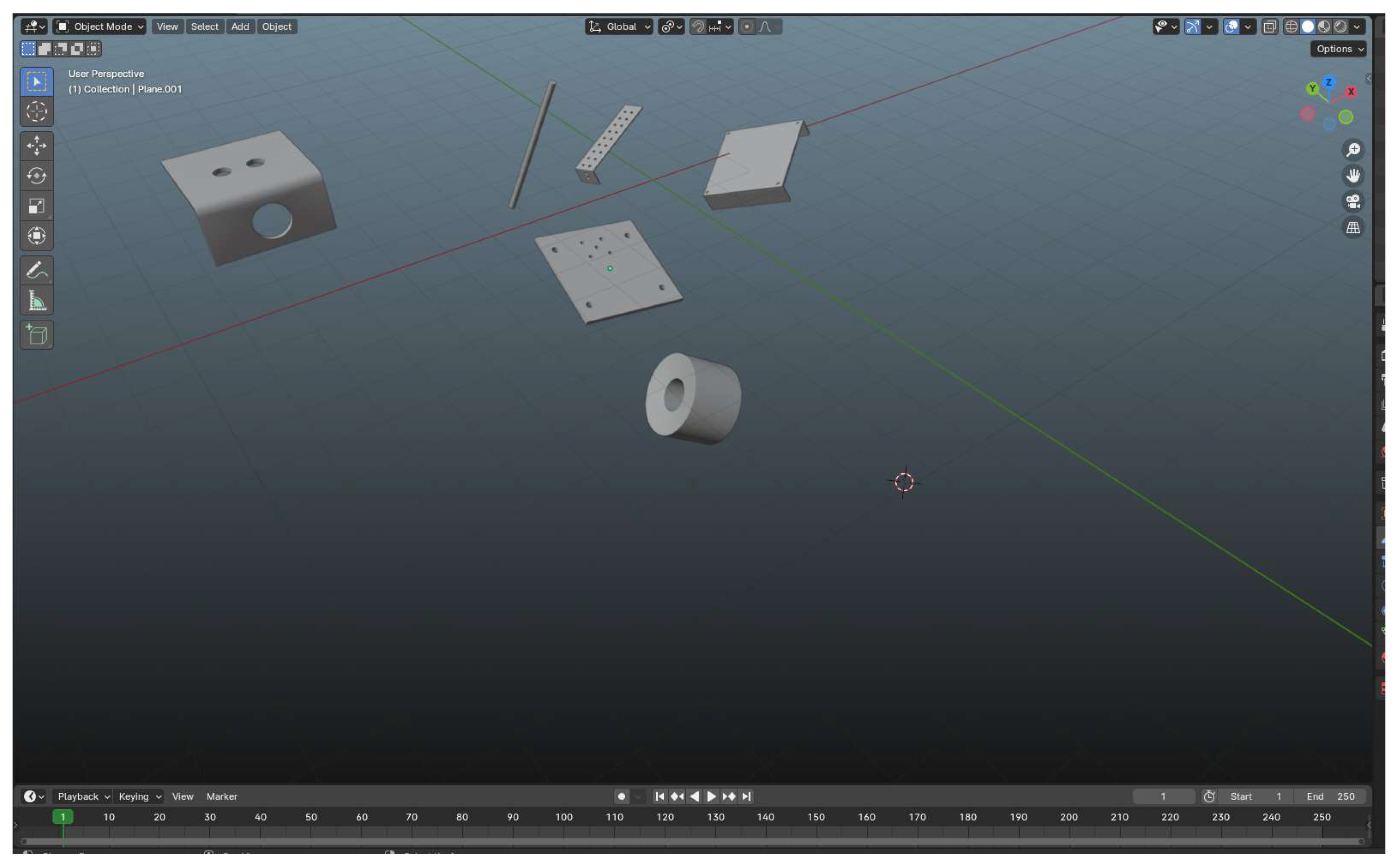

Figure 2.

CAD models converted into game engine supported models.

Figure 2.

CAD models converted into game engine supported models.

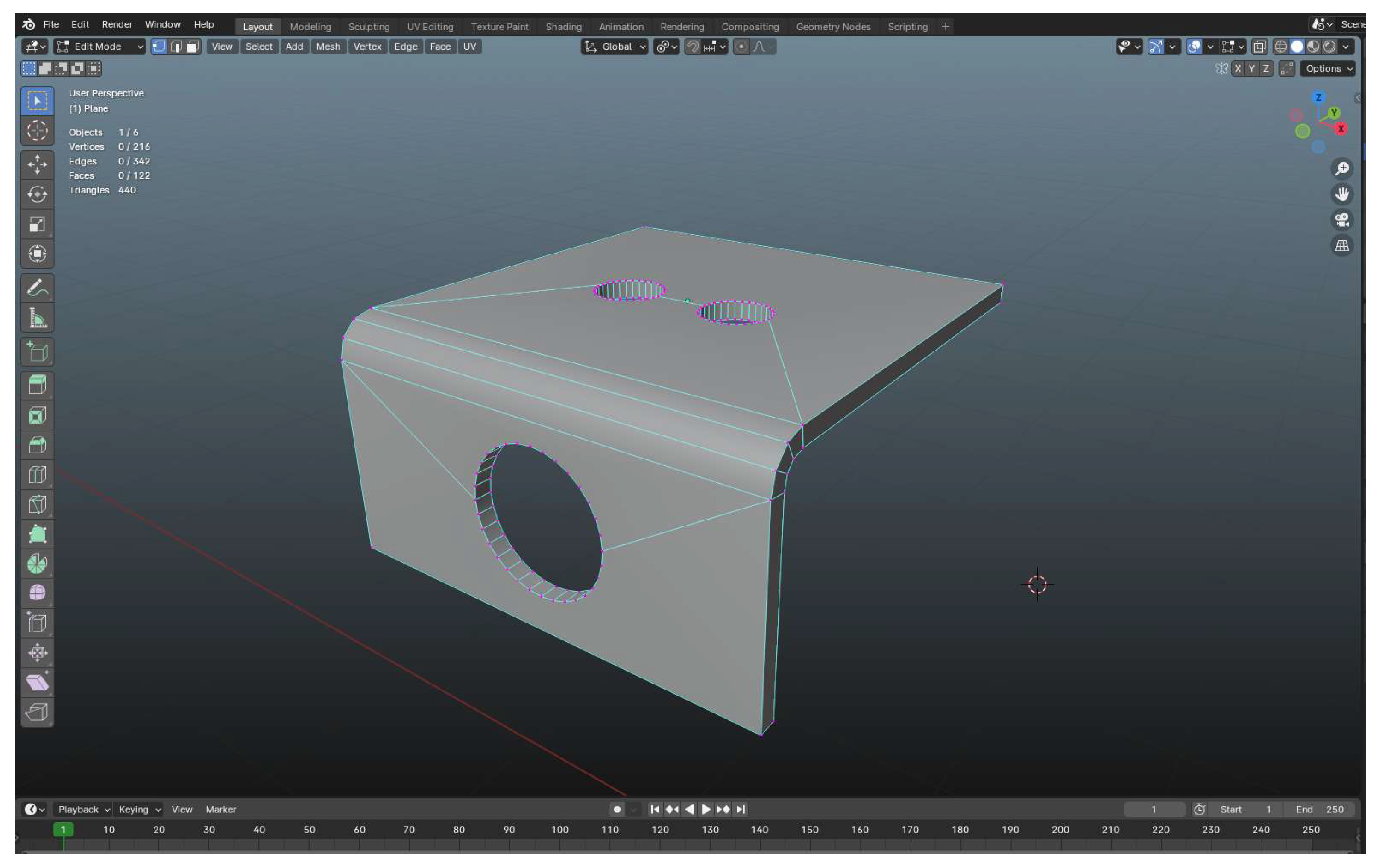

Figure 3.

A 3D mesh model in Blender, highlighting the topology with visible edge loops and vertices. Proper topology is critical for optimizing the model's geometry, ensuring smooth deformation, and efficient UV mapping, particularly in the curved mesh areas.

Figure 3.

A 3D mesh model in Blender, highlighting the topology with visible edge loops and vertices. Proper topology is critical for optimizing the model's geometry, ensuring smooth deformation, and efficient UV mapping, particularly in the curved mesh areas.

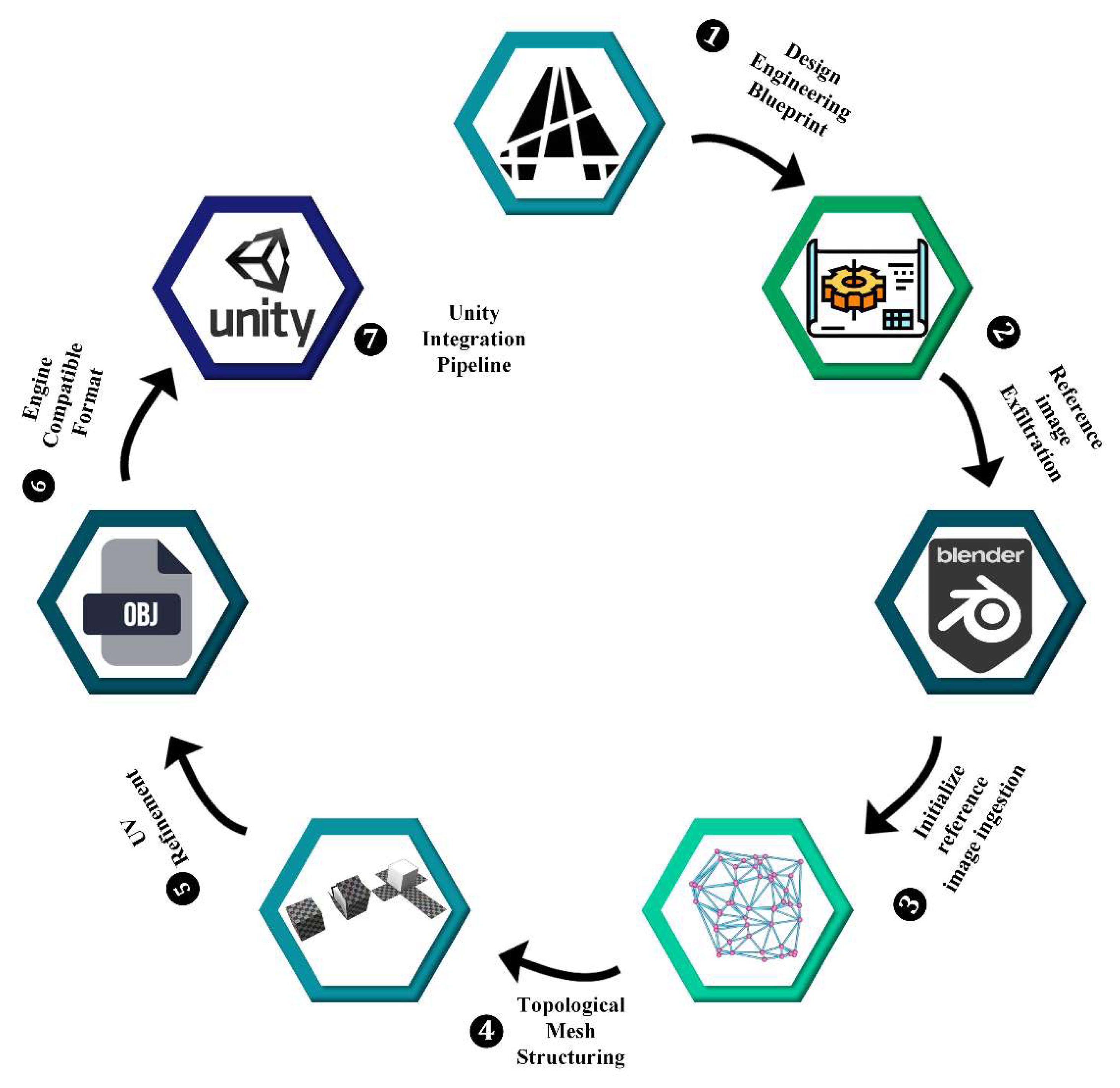

Figure 4.

Designing the PI-CT machine in AutoCAD, creating a mesh from reference images in Blender, adjusting topology and UV mapping, and saving the model as an ".obj" file for import into Unity.

Figure 4.

Designing the PI-CT machine in AutoCAD, creating a mesh from reference images in Blender, adjusting topology and UV mapping, and saving the model as an ".obj" file for import into Unity.

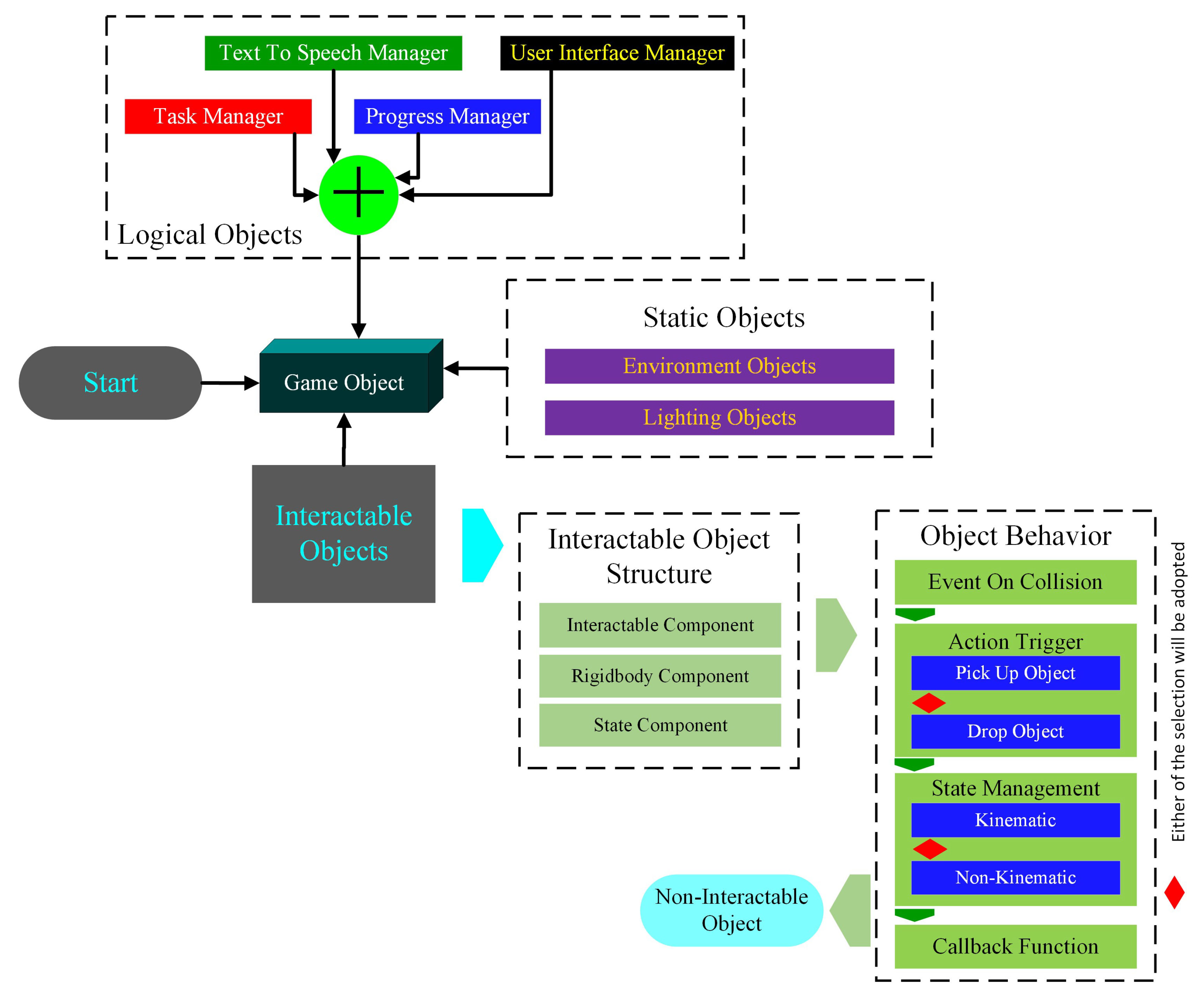

Figure 5.

Implementing interactive behaviors in VR: object manipulation and engagement.

Figure 5.

Implementing interactive behaviors in VR: object manipulation and engagement.

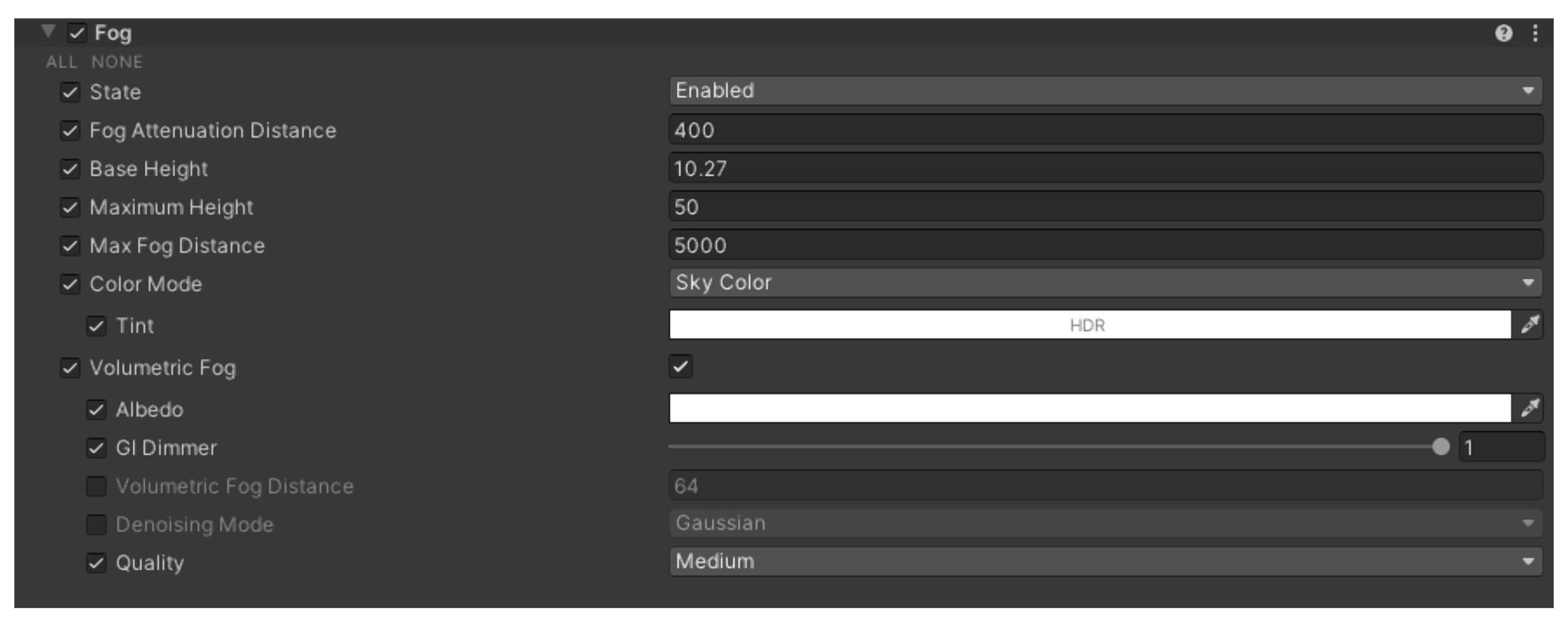

Figure 6.

Fog settings panel in a game engine or 3D software. Displaying various parameters to control fog effects, including distance, height, and color.

Figure 6.

Fog settings panel in a game engine or 3D software. Displaying various parameters to control fog effects, including distance, height, and color.

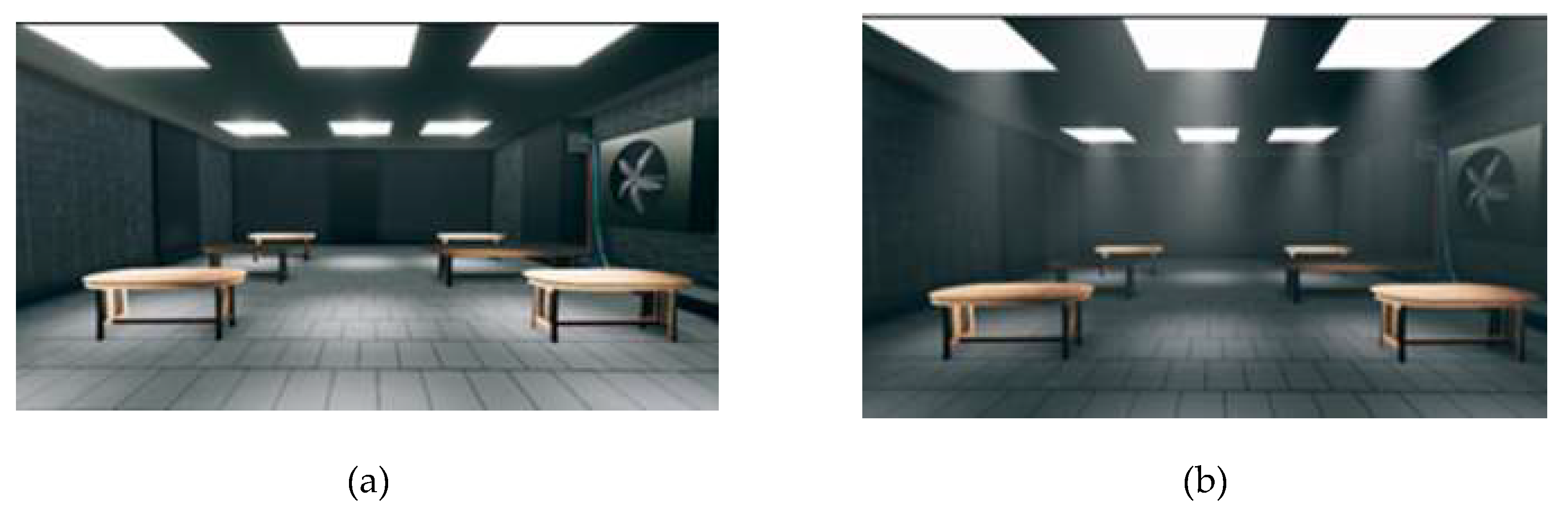

Figure 7.

Comparison of lighting effects in a 3D rendered room, (a) without volumetric lighting, (b) with volumetric lighting, showing enhanced atmosphere and light scattering.

Figure 7.

Comparison of lighting effects in a 3D rendered room, (a) without volumetric lighting, (b) with volumetric lighting, showing enhanced atmosphere and light scattering.

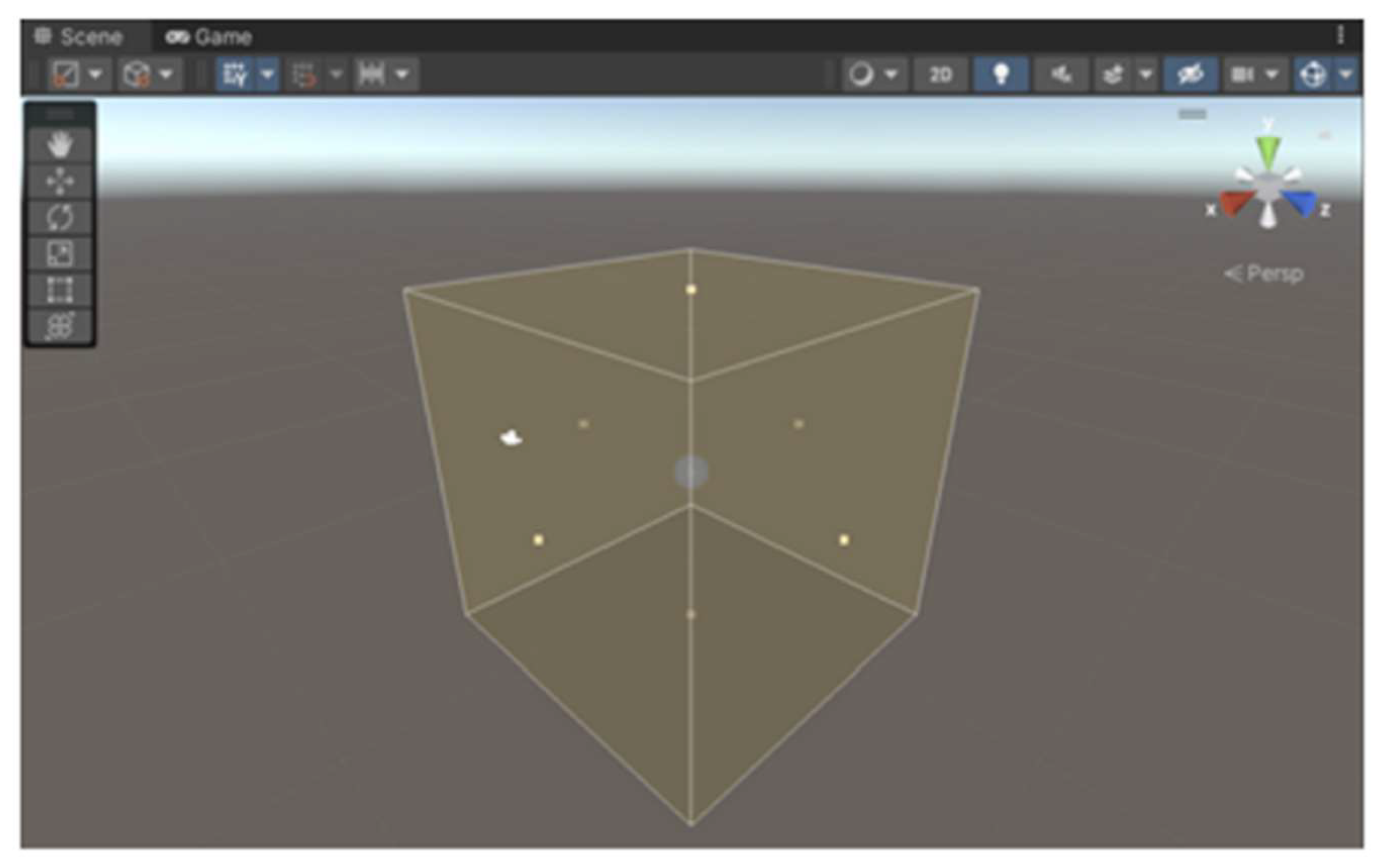

Figure 8.

Adjustment of the reflection probe volume that is expected to be responsible for rendering the accurate reflection of the surroundings.

Figure 8.

Adjustment of the reflection probe volume that is expected to be responsible for rendering the accurate reflection of the surroundings.

Figure 9.

A detailed comparison of visuals, (a) the scene which doesn’t include any reflection probe, (b) the scene which include reflection, it provides the accurate reflection and stable lighting.

Figure 9.

A detailed comparison of visuals, (a) the scene which doesn’t include any reflection probe, (b) the scene which include reflection, it provides the accurate reflection and stable lighting.

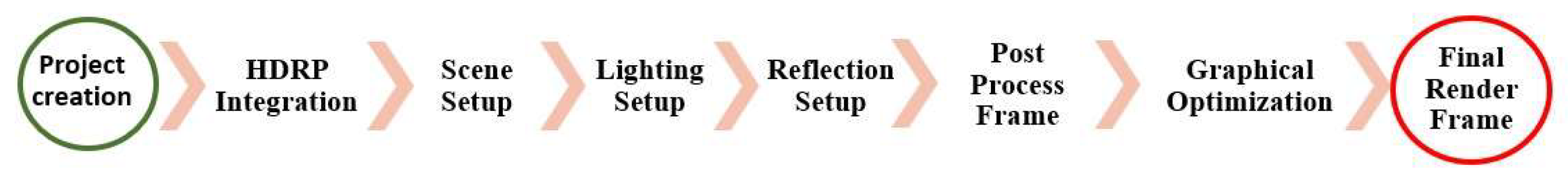

Figure 10.

Workflow for creating a high quality rendered scene in a virtual environment. It outlines the essential steps, including project creation, HDRP integration, scene setup, lighting setup, graphical optimization, and post-processing.

Figure 10.

Workflow for creating a high quality rendered scene in a virtual environment. It outlines the essential steps, including project creation, HDRP integration, scene setup, lighting setup, graphical optimization, and post-processing.

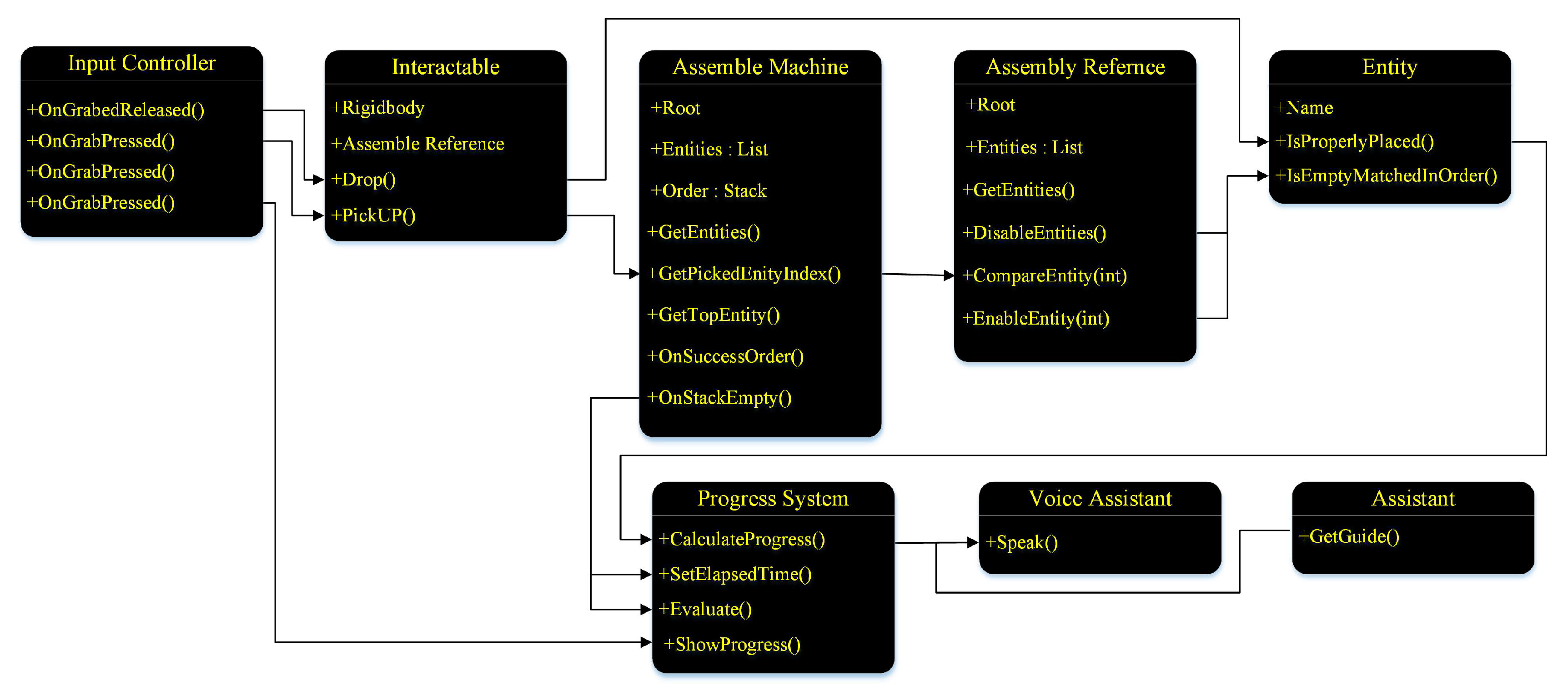

Figure 11.

Depiction of the proposed VRTMS using UML perspective. It includes an Input Controller that manages input events like grabbing and menu interactions and an InteractableClass for object interactions, such as picking up and dropping items. The Assemble Machine and Assembly Reference classes handle the assembly process, managing entities and their order in a stack. The Entity Class ensures items are placed correctly during assembly. The Progress System tracks and evaluates progress, while the Voice Assistant provides spoken guidance and the Assistant offers additional support and information.

Figure 11.

Depiction of the proposed VRTMS using UML perspective. It includes an Input Controller that manages input events like grabbing and menu interactions and an InteractableClass for object interactions, such as picking up and dropping items. The Assemble Machine and Assembly Reference classes handle the assembly process, managing entities and their order in a stack. The Entity Class ensures items are placed correctly during assembly. The Progress System tracks and evaluates progress, while the Voice Assistant provides spoken guidance and the Assistant offers additional support and information.

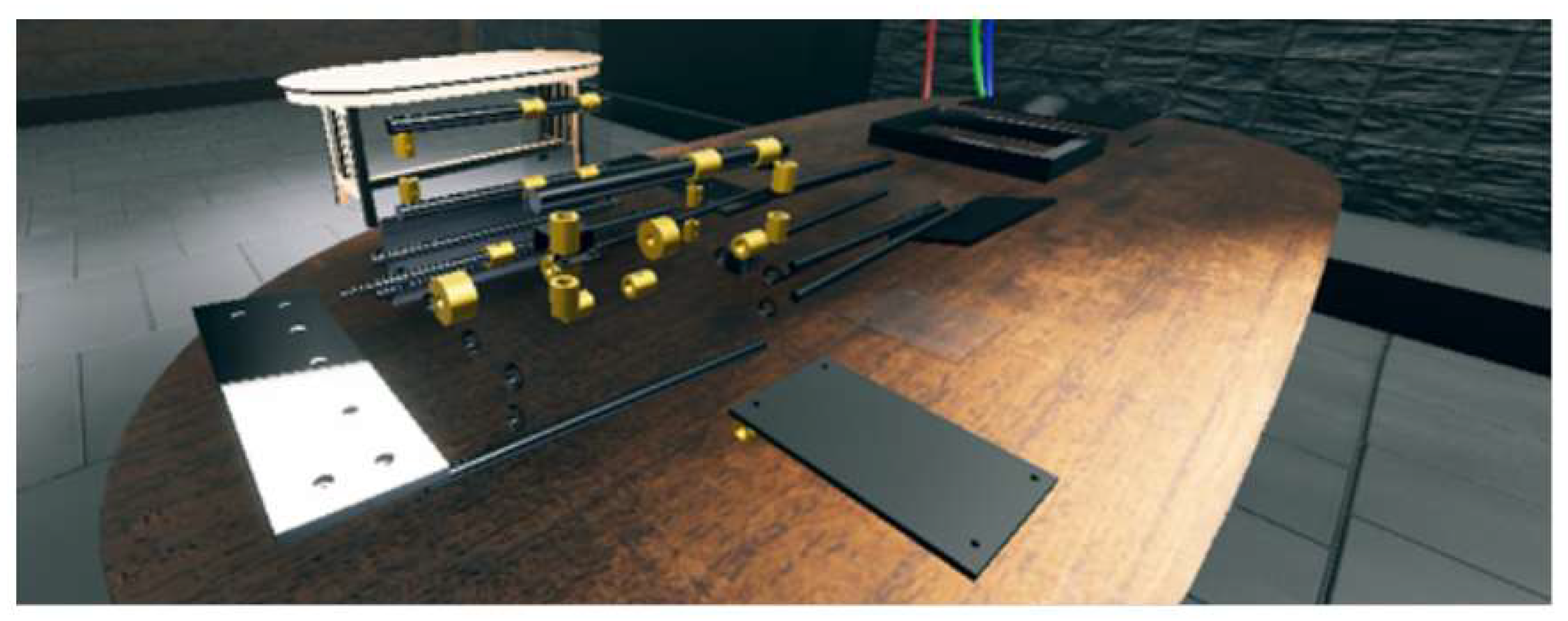

Figure 12.

Set of interactable components of PI-CT machine that can be interacted using hand touch controllers.

Figure 12.

Set of interactable components of PI-CT machine that can be interacted using hand touch controllers.

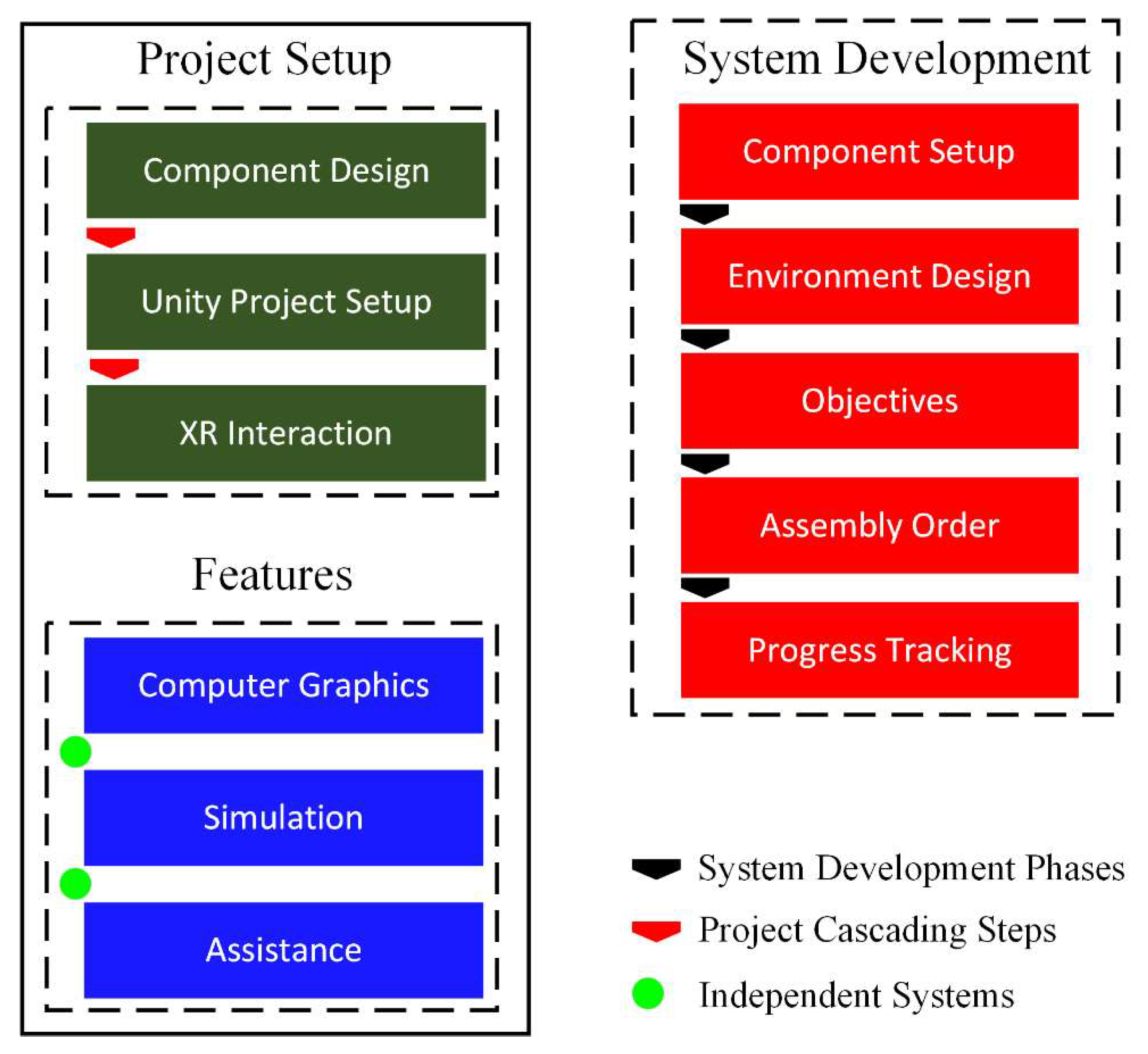

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram of the workflow of a VR Assembly Workspace, outlining the key stages involved in project setup, features, project cycle, and objectives, providing a visual representation of the process from initial component design to the final assembly.

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram of the workflow of a VR Assembly Workspace, outlining the key stages involved in project setup, features, project cycle, and objectives, providing a visual representation of the process from initial component design to the final assembly.

Figure 14.

Player controller in the scene with hands that can be controlled through touch controllers.

Figure 14.

Player controller in the scene with hands that can be controlled through touch controllers.

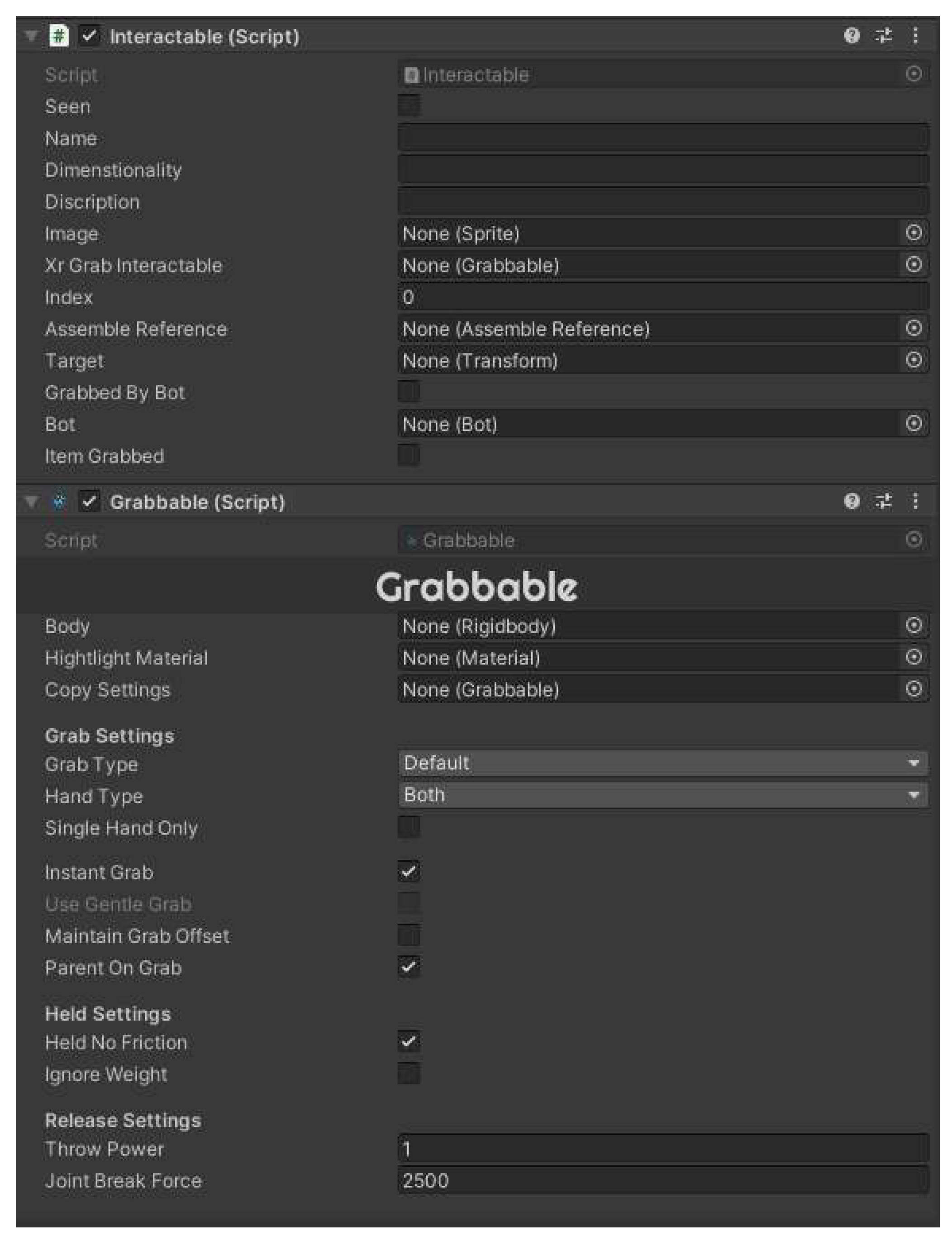

Figure 15.

Unity editor displaying two custom scripts: Interactable and Grabbable. The Interactable script manages object properties like Name, Xr Grab Interactable, and Assemble Reference. The Grabbable script configures grabbing behavior, including Grab Type, Hand Type, Instant Grab, and physics settings like Throw Power and Joint Break Force.

Figure 15.

Unity editor displaying two custom scripts: Interactable and Grabbable. The Interactable script manages object properties like Name, Xr Grab Interactable, and Assemble Reference. The Grabbable script configures grabbing behavior, including Grab Type, Hand Type, Instant Grab, and physics settings like Throw Power and Joint Break Force.

Figure 16.

IK controlled interaction of each component of PI-CT machine.

Figure 16.

IK controlled interaction of each component of PI-CT machine.

Figure 17.

Controls’ instructions using the hand-touch controller of the Meta Quest 2.

Figure 17.

Controls’ instructions using the hand-touch controller of the Meta Quest 2.

Figure 18.

An interactive training setup for assembly tasks. The user holds a holographic interface with options to "Get Info," "Get Dimension," and "Close" while interacting with a 3D model of a cylindrical component on a workbench. Various machine parts are laid out in the background for assembly.

Figure 18.

An interactive training setup for assembly tasks. The user holds a holographic interface with options to "Get Info," "Get Dimension," and "Close" while interacting with a 3D model of a cylindrical component on a workbench. Various machine parts are laid out in the background for assembly.

Figure 19.

Flowchart of a virtual assembly task outlining the steps involved, including system guidance, user interaction, collision checking, component placement, progress monitoring, and performance evaluation. It also depicts the role of a manager in overseeing the process and maintaining a stack of components to be placed.

Figure 19.

Flowchart of a virtual assembly task outlining the steps involved, including system guidance, user interaction, collision checking, component placement, progress monitoring, and performance evaluation. It also depicts the role of a manager in overseeing the process and maintaining a stack of components to be placed.

Figure 20.

The final assembly of the PI-CT machine in a virtual environment. All modular components are securely in place, demonstrating the complete structure. The interface provides interactive options for further exploration of the machine's features, such as retrieving information and dimensions.

Figure 20.

The final assembly of the PI-CT machine in a virtual environment. All modular components are securely in place, demonstrating the complete structure. The interface provides interactive options for further exploration of the machine's features, such as retrieving information and dimensions.

Figure 21.

The user action triggering the instruction of the speech synthesis by the WiT text-to-speech model.

Figure 21.

The user action triggering the instruction of the speech synthesis by the WiT text-to-speech model.

Figure 22.

Unity profiler statistics displaying key performance metrics. The frame rate is 118.4 FPS with a total frame time of 8.4 ms. The CPU's main thread runs 8.4 ms, and the render thread is 5.7 ms. Graphics data includes 500 batches, 437.2k triangles, and 367.6k vertices. DSP load stands at 0.2%.

Figure 22.

Unity profiler statistics displaying key performance metrics. The frame rate is 118.4 FPS with a total frame time of 8.4 ms. The CPU's main thread runs 8.4 ms, and the render thread is 5.7 ms. Graphics data includes 500 batches, 437.2k triangles, and 367.6k vertices. DSP load stands at 0.2%.

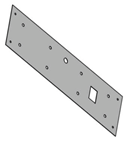

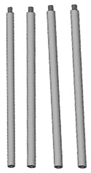

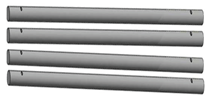

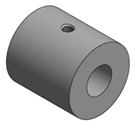

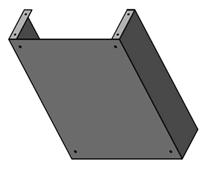

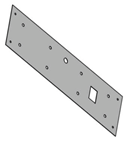

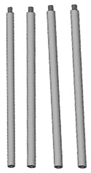

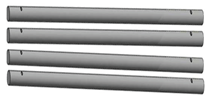

Table 1.

Various components of a mechanical assembly, including (a) base plate, (b) front plate, (c) vertical rods, (d) horizontal rods, (e) slide beds and threaded rods, (f) phantom, (g) stepper motor, (h) strip of stepper motor, (i) phantom holder, (j) washer, (k) stepper motor coupling, and (l) slider thread trans. Each labeled part is essential for constructing the system's structure and enabling precise movement.

Table 1.

Various components of a mechanical assembly, including (a) base plate, (b) front plate, (c) vertical rods, (d) horizontal rods, (e) slide beds and threaded rods, (f) phantom, (g) stepper motor, (h) strip of stepper motor, (i) phantom holder, (j) washer, (k) stepper motor coupling, and (l) slider thread trans. Each labeled part is essential for constructing the system's structure and enabling precise movement.

(a) |

(b) |

(c) |

(d) |

(e) |

(f) |

(g) |

(h) |

(i) |

(j) |

(k) |

(l) |

Table 2.

Experimentation conducted by the users, monitoring their time taken and a number of mistakes they made in the session.

Table 2.

Experimentation conducted by the users, monitoring their time taken and a number of mistakes they made in the session.

| USER |

TIME TAKEN (IN MINS) |

NO. OF WRONG ATTEMPTS |

| USER 01 |

25 |

2 |

| USER 02 |

32 |

0 |

| USER 03 |

18 |

5 |

| USER 04 |

35 |

1 |

| USER 05 |

40 |

10 |

Table 3.

Performance Comparison Without and With DLSS.

Table 3.

Performance Comparison Without and With DLSS.

| Metric |

Without DLSS |

With DLSS |

| CPU Usage |

12-14% |

6-7% |

| GPU Usage |

69% |

29%-31% |

| GPU temperature |

82 C |

62 C |

| FPS |

50-61 |

80-114 |