1. Introduction

The creation of reliable electrochemical energy storage devices is a primary task for the storage, conversion and further use of renewable (clean) energy [

1,

2,

3]. There are two main types of energy storing and accumulating devices: supercapacitors and lithium-ion batteries [

4,

5,

6]. Supercapacitors (SC) are electrochemical energy sources characterised by high power, long life and stability over multiple charge/discharge cycles, safety and environmental friendliness [

7,

8,

9]. The performance of supercapacitors directly depends on the active material of the electrode [

10,

11]. There is currently a lot of work using transition metal oxides as the active material of the electrodes [

12,

13]. The redox behavior of these oxides is related to the multivalent nature of transition metals. Promising materials include iron-based materials such as hematite (Fe

2O

3) [

14,

15], magnetite (Fe

3O

4) [

16], FeOOH [

17], FeO

x [

18] and CoFe

2O

4, [

19] etc. They have attracted attention as promising materials for SC electrodes due to their high theoretical capacitance, wide negative potential range (-1.2 - 0 V), abundance in nature, low cost and non-toxicity. [

20,

21,

22]. Despite the high values of specific capacitance, most transition metal oxides have low conductivity, poor stability, low charging rate and short life during the charge/discharge process [

23,

24]. One way to improve the conductivity of iron-based materials is to combine them with conductive carbon materials. Due to the synergistic effect of the high capacitance of iron oxides and the high conductivity of carbon materials, composite materials demonstrate better electrochemical characteristics than the original pseudocapacitive materials [

25,

26,

27]. Carbon nanotubes are characterised by high conductivity, large specific surface area, mesoporosity, environmental friendliness and chemical stability. These properties make them a promising material for supercapacitor electrodes [

28,

29].

Conventional electrode manufacturing processes use binders. These binders usually have high resistivity and low electrochemical activity. Their use degrades the electrochemical performance of the electrode by increasing the internal resistance [

30]. In addition, conventional binders are often based on organic solvents, which can have an impact on the environment. Therefore, the study of binder-free electrode preparation methods has become an important area of research to improve the performance of supercapacitors. The preparation of binder-free electrodes increases the amount of active material in the electrodes and also significantly increases the conductivity of the electrode. One way to prepare binder-free electrodes is to grow electrochemically active materials on conductive substrates [

31].

Synthesis of the MWCNT on metal substrates allows improving electrochemical properties due to a decrease in the contact resistance between the active electrode material and the current collector [

32,

33]. Aluminum is a promising material for supercapacitor electrodes due to its high electrical conductivity and plasticity [

34]. Electrodes made of aluminum foil coated with a MWCNT layer are suitable for use in flexible supercapacitors [

35]. Composite electrodes based on carbon nanotubes with transition metal oxides combine physical and chemical mechanisms of charge accumulation on a single electrode. Nanotube-based materials promote charge generation through the formation of an electric double layer (EDLC) and also provide a large specific surface area [

36], which in turn increases the contact area between the electrolyte and the pseudocapacitive materials applied to the MWCNT. In this case, pseudocapacitive materials increase the specific capacitance values due to fast redox reactions (Faraday reactions) [

37,

38]. There are various technologies for the production of composite materials. Methods such as hydrothermal deposition [

39], electrochemical deposition [

40,

41,

42] and electrospinning [

43] are used to produce an electrode without a binder.

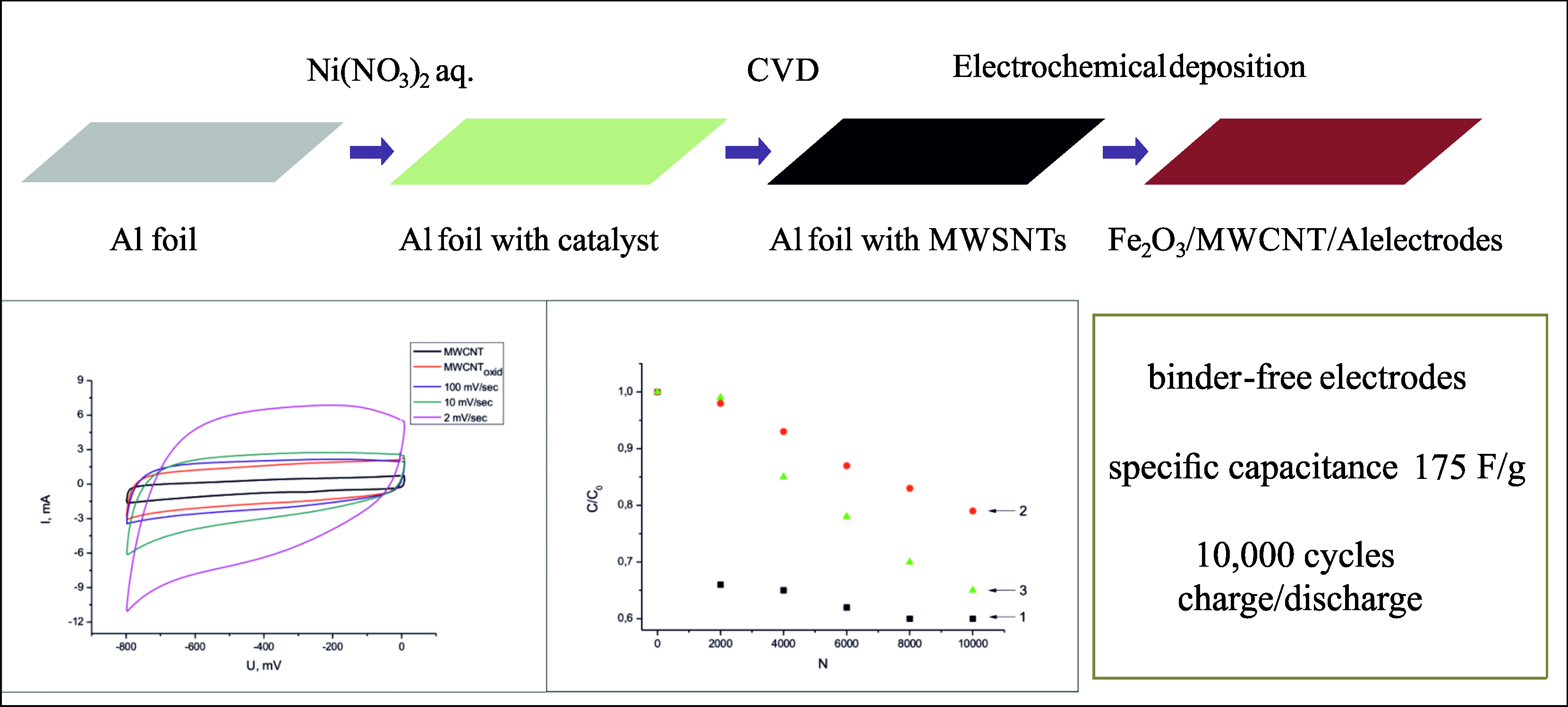

In this work, the possibility of producing a composite electrode based on multi-walled carbon nanotubes and iron oxide without the use of binders was investigated. Thin films of Fe2O3 were deposited on the surface of carbon nanotube arrays grown on aluminum foil by electrochemical deposition. The optimal mode of preliminary electrochemical oxidation of the carbon nanotubes was selected, which allowed obtaining a composite electrode with high resistance to numerous charge/discharge cycles (10,000). The dependence of the specific capacity and stability of the electrode material on the annealing temperature was studied. The electrochemical properties of the composite were studied as a function of the parameters of iron hydroxide film formation on the surface of the carbon nanotube array. The optimum mode of composite formation was selected, which allowed a fivefold increase in specific capacitance. All samples were characterised by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Raman spectroscopy (RS) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

2. Materials and Methods

Synthesis of MWCNTs on Aluminum Foil

The synthesis of carbon nanotubes was carried out using a previously developed method [

44]. A CVD synthesis setup was used for deposition. MWCNTs were deposited at atmospheric pressure onto aluminum foil substrates coated with a catalyst layer. The deposition temperature was 600°C, and the synthesis duration was 1 hour. Ethanol consumption was 6–7 ml/h.

Synthesis of Fe2O3/MWCNT/Al Composite Material

Pre-oxidized MWCNT/Al samples were used to prepare the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al composite material. Electrochemical oxidation of the MWCNT/Al material was carried out in a two-electrode cell. A platinum wire served as a counter electrode. A strip of aluminum foil coated with a MWCNT layer acted as an anode during the oxidation process. A 0.005 M Na

2SO

4 solution was used as an electrolyte. The oxidation time was 10 minutes at a voltage of 4 V [

45]. A three-electrode electrochemical cell was used to form the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al composite material. The process was carried out using a P-40X potentiostat (Electrochemical Instruments, Chernogolovka, Russia). A mixture of 0.1 M aqueous solution of Fe(NH

4)

2(SO

4)

2 (iron ammonium sulfate) and 0.08 M CH

3COONa (sodium acetate) in a 1:1 ratio was used as an electrolyte. A saturated calomel electrode was used as the reference electrode and a pure platinum wire as the counter electrode. The voltage range was from -10 to 700 mV, and the voltage sweep rate varied from 2 to 100 mV/sec. The samples were then washed in distilled water and dried in air for 24 hours. The material obtained was annealed in air at temperatures of 200, 300 and 400°C.

Structural Characterization

The Raman spectra of the obtained samples were studied in the range of 150-2000 cm-1 with a spectral resolution of 9-15 cm-1 using a Bruker Senterra micro-Raman system coupled to an OLYMPUS BX51 optical microscope. The spectra were recorded under excitation by a solid-state laser at a wavelength of 532 nm. The laser operating power was 5 mW. X-ray photoelectron spectra of the sample were obtained on a SPECS electron spectrometer with a FOIBOS-150 energy analyser (SPECS GmbH, Berlin, Germany) using non-monochromatic Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV). The spectra were measured at an anode voltage of 12.5 kV and an emission current of 19.0 mA on the XR50 X-ray source. The spectra obtained were processed using the CasaXPS software (version 2.3.25PR1.0). To compare and study the morphology of the samples obtained, an AURIGA CrossBeam microscope (Carl Zeiss NTS, Germany) was used in scanning mode with an acceleration voltage of 5 kV. An attachment to the JEOL 6490 INCA Oxford Instruments electron microscope was used to study the elemental composition of the samples. The electron accelerating voltage was 15 kV and the current was ~1 nA.

Electrochemical Measurements

Electrochemical tests on the original and modified samples (cyclic voltammetry, impedance spectroscopy) were carried out in a three-electrode cell. A saturated calomel electrode was used as the reference electrode. A platinum wire was used as the counter electrode. The working electrode was a strip of aluminum foil (0.75 × 2 cm2) coated on both sides with a composite material. A 0.5 M aqueous solution of Na2SO4 was used as the electrolyte. Electrochemical impedance measurements were carried out in the presence of a 0.5 M aqueous solution of Na2SO4 at a constant potential of 0 V, superimposed on an alternating potential with an amplitude of 20 mV in the frequency range from 50 kHz to 100 mHz. Electrochemical measurements were performed using a P-40X potentiostat equipped with an FRA-24M frequency analyser module (Electrochemical Instruments, Chernogolovka, Russia).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Formation of Fe2O3/MWCNT/Al Composite Material

An array of carbon nanotubes grown directly on aluminum foil can serve as a basis for obtaining Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al composites with high specific capacitance values due to the pseudocapacitive properties of iron oxide. An analysis of the literature shows that the fictionalization of the carbon material plays an important role in the formation of an iron oxide layer on the surface of a carbon material [

46]. The technique of electrochemical oxidation in a weak Na

2SO

4 solution allows the optimal conditions for processing the MWCNT/Al material to be selected. It is important to select conditions for preoxidation of the sample that not only ensure further formation of the composite, but also do not lead to destruction of the MWCNT layer. During the experiments, it was found that the optimum processing conditions are achieved by electrochemical oxidation of MWCNT/Al samples for 10 minutes in 0.005 M aqueous Na

2SO

4 solution at an oxidation voltage of 4 V. Fe(NH

4)

2(SO

4)

2 was used as the source of iron in the formation of the composite. CH

3COONa was used as a reducing agent to prevent destruction of the MWCNT layer. An iron hydroxide layer was formed on the MWCNT surface [

47]. The resulting material was annealed in air at 200, 300 and 400°C to form the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al composite material.

In order to select the optimum conditions for obtaining the composite, preliminary tests were carried out at different voltage sweep rates. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) of the surface layer of all samples processed showed the presence of carbon, oxygen and iron as the main components of the active layer. At a voltage sweep rate of 2 mV/s, the composite material contained the largest amount of not only iron but also oxygen (25.2 and 39.9 mass %, respectively). The lowest amount of iron was found in the sample obtained at a voltage sweep rate of 100 mV/s (9.2 mass %). The electrochemically oxidised MWCNT/Al sample contained 85 mass % carbon and 15 mass % oxygen. The samples obtained at a voltage sweep rate of 2 mV/s were selected for further investigation. To convert the iron hydroxide layer to oxide, the material was annealed at 200, 300 and 400 °C. The morphology of the composite material was studied using scanning electron microscopy.

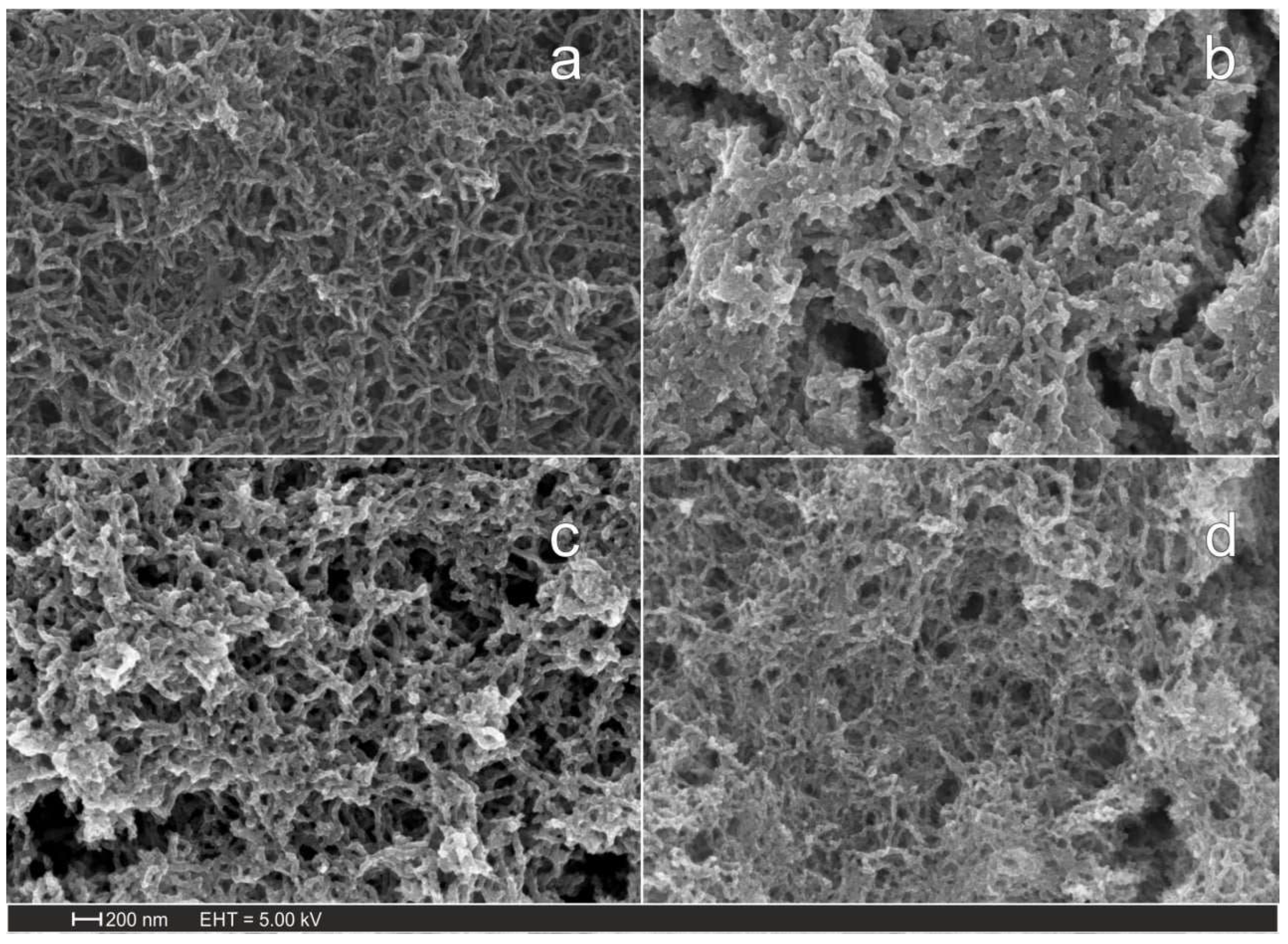

Figure 1 shows the scanning electron microscopy images of carbon nanomaterials (

Figure 1a) and Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al composites (

Figure 1b-d). The studies were carried out on samples obtained at annealing temperatures of 200 (

Figure 1b), 300 (

Figure 1c) and 400°C (

Figure 1d). In all cases, we observe intertwined MWCNTs, and in the case of the composite material, the surface of the carbon nanotubes is covered with a layer of iron oxide.

The chemical structure of the composite material was studied using Raman spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.

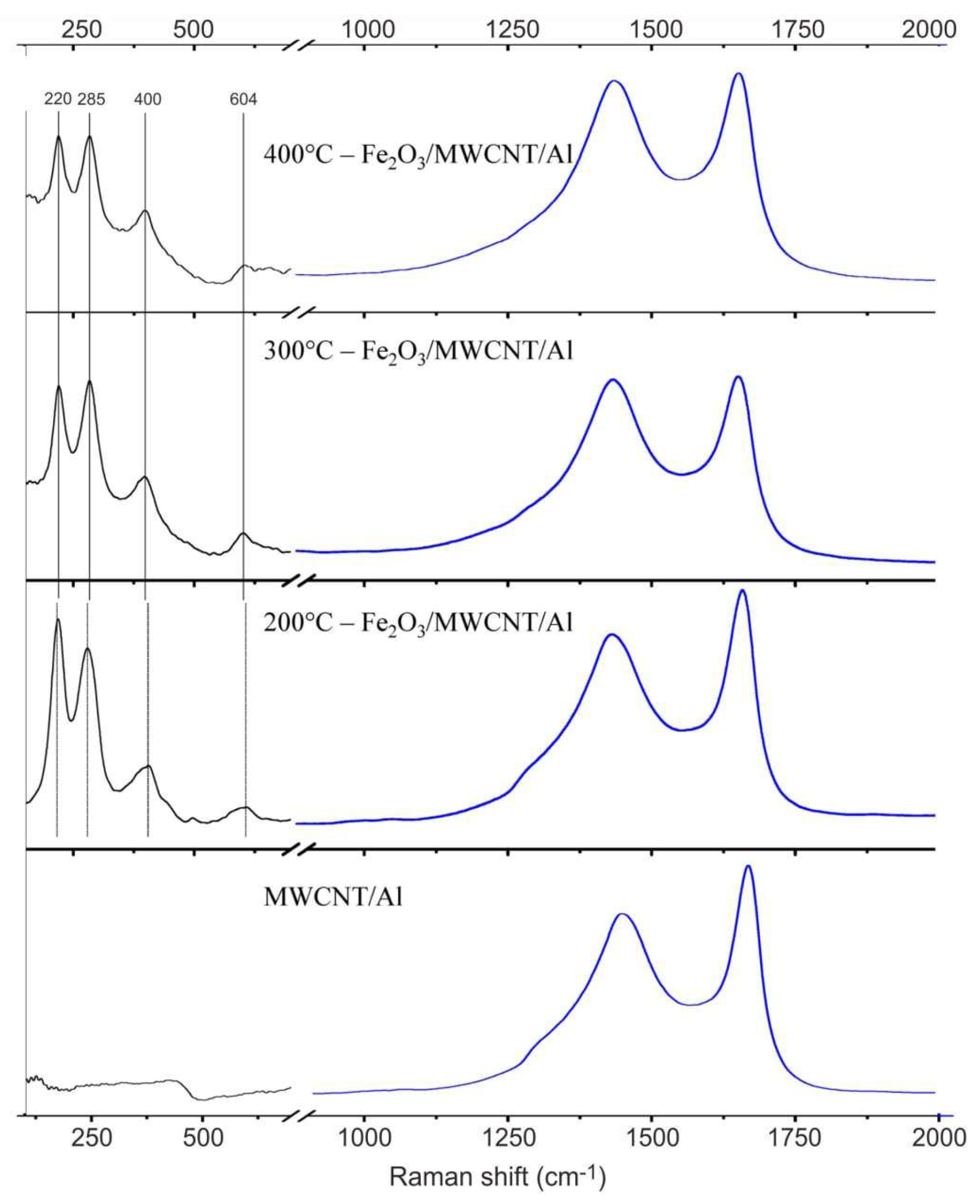

Figure 2 shows the Raman spectra for the MWCNT/Al (1) and Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al (2-4) composite material samples.

All spectra show two broad peaks at about 1335 and 1600 cm

-1 [

48], which belong to MWCNTs (peaks D and G, respectively). Band G corresponds to the vibrations of the hexagonal crystal lattice of carbon and band D characterises the disorder of the MWCNT structure [

49]. Since hematite belongs to the crystal space group D6 3d, the phonon modes A1g (220 cm

-1) and Eg (285, 400, and 604 cm

-1) can be distinguished in the spectra obtained [

50]. The results show that three samples are covered with a layer of hematite. However, for the composite obtained at 200°C, the decrease of the intensity of the peak Eg1 (400 cm

-1) to the intensity of the peak Eg (285 cm

-1), as well as a slight shift of the peaks A1g and Eg (285 cm

-1) towards the low frequency region, may indicate a less perfect crystalline structure of the material [

51]. This may also be indicated by a change in the ratio of the intensities of peaks A1g and Eg (285 cm

-1) [

52].

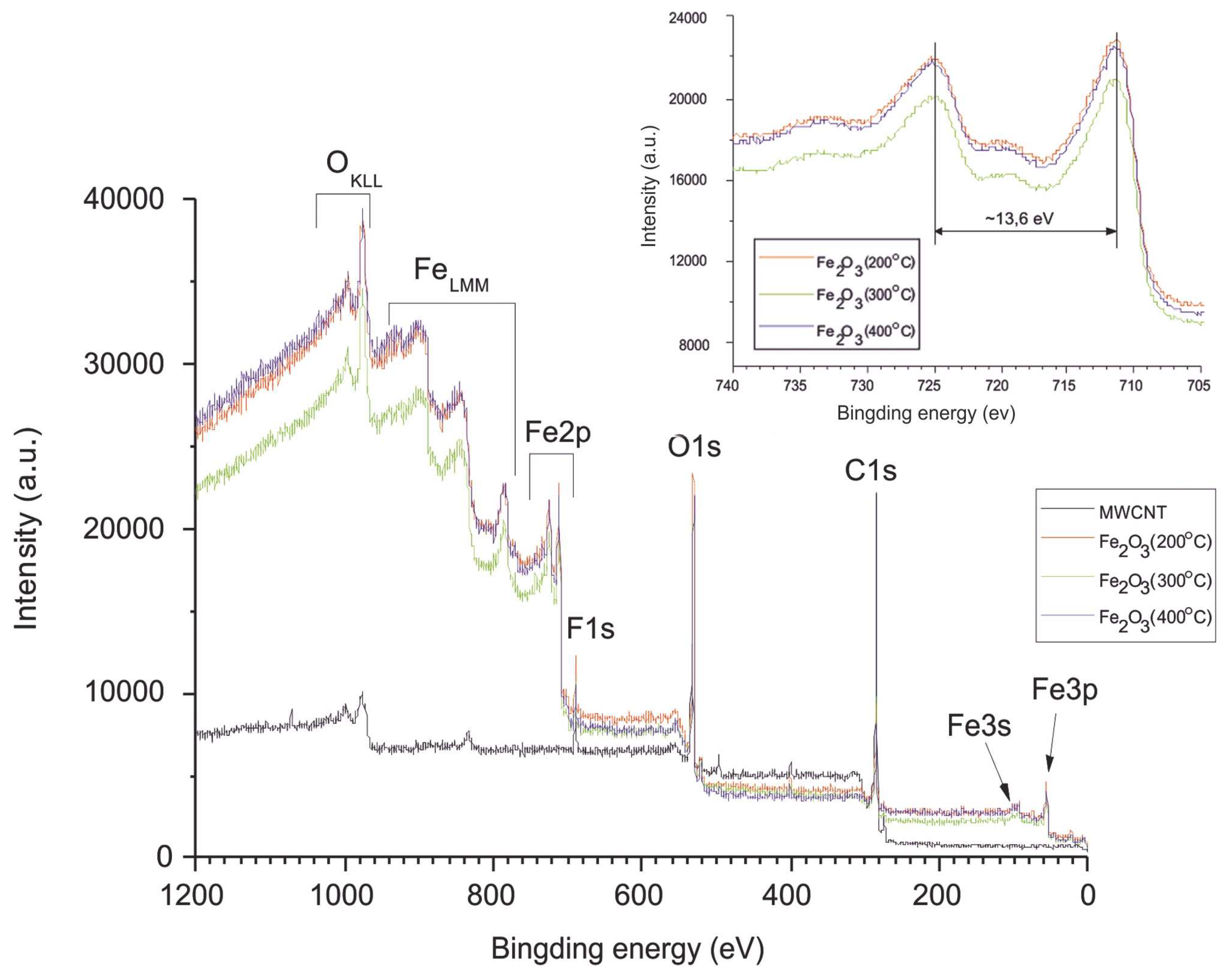

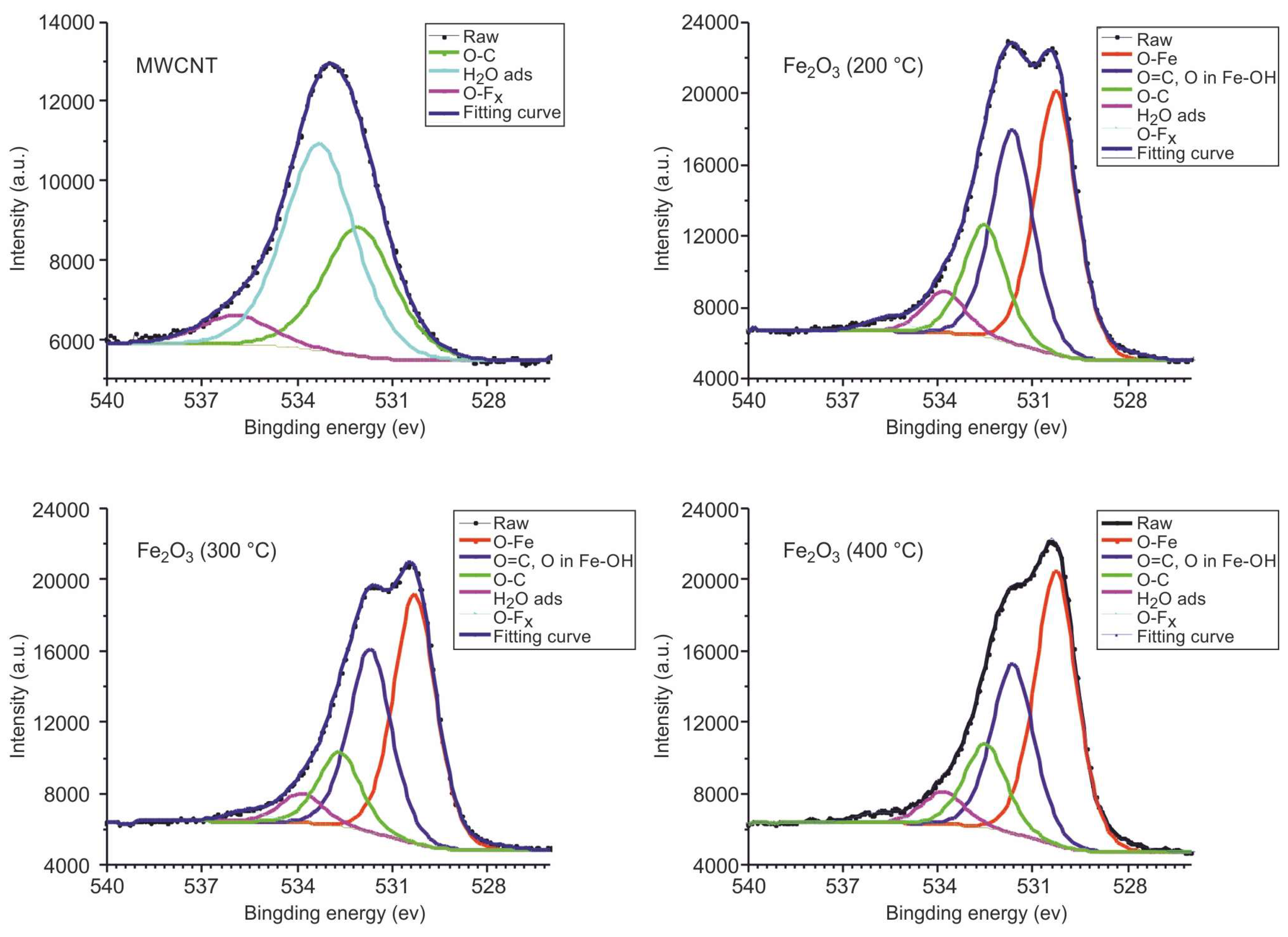

Typical XPS spectra are shown in

Figure 3. The main intense lines in the survey spectrum with AlKα excitation are the series of iron, carbon and oxygen spectra.

The high resolution spectrum of Fe2p (

Figure 3, inset) shows for all iron containing samples two distinct peaks (Fe 2p 3/2 and 2p 1/2) separated by a broad satellite peak at 711.4 and 725 eV respectively. The separation of the spin energies of Fe 2p 3/2 and 2p 1/2 is 13.6 eV, indicating that Fe in the composite is in the Fe

3+ state [

53].

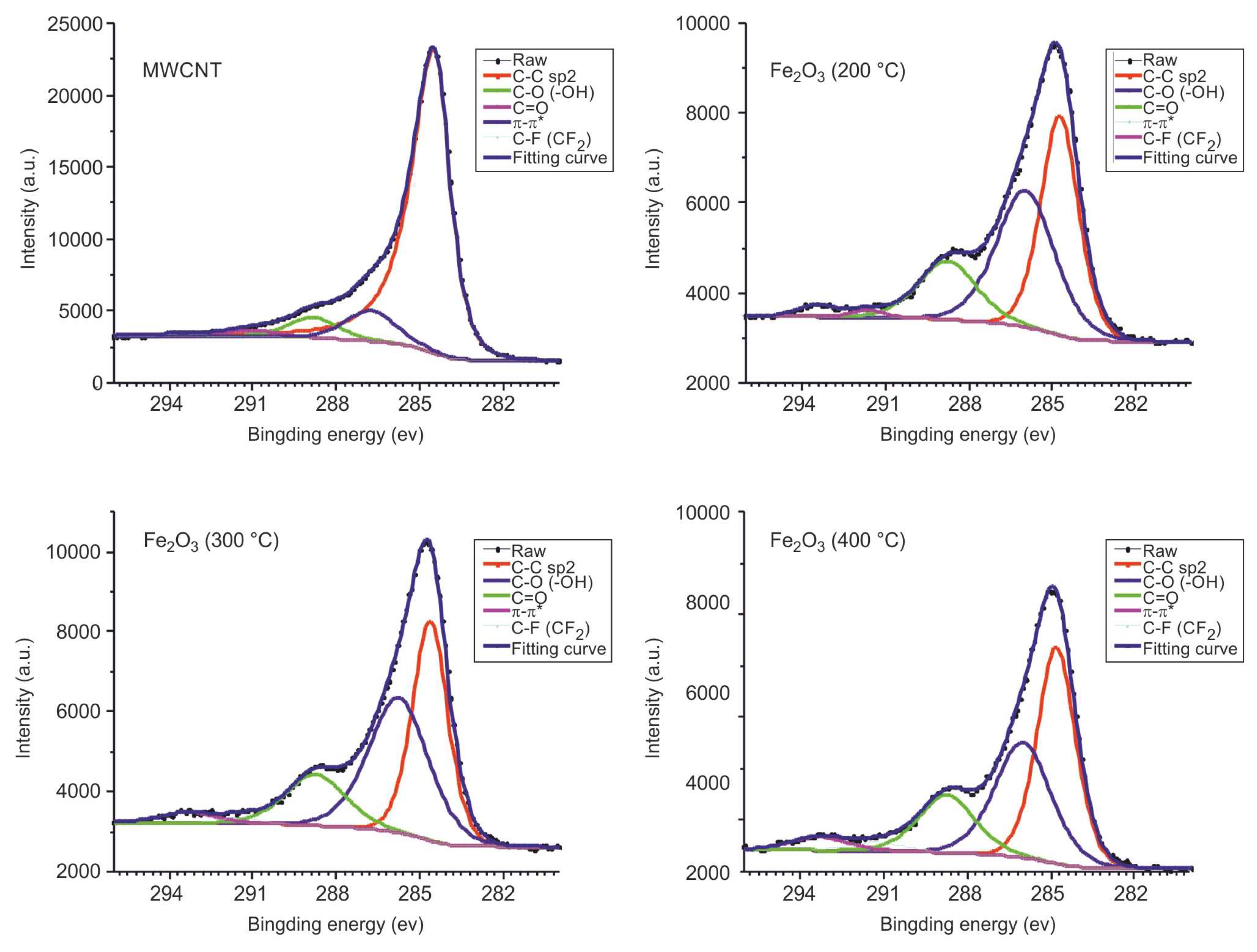

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the high resolution XPS spectra of carbon (C1s) and oxygen (O1s). As can be seen from

Figure 4, the spectra of carbon (C1s) are multi-component [

54]. For sample 1, the spectrum corresponds to lightly oxidised carbon. Carbon in samples 2-4 is more oxidised. The C1s spectrum can be resolved into three peaks centred at 284.6 eV (C-C), 286.2 eV (C-O) and 288.6 eV (C=O) [

55].

The oxygen spectrum is also multi-component (

Figure 5). In sample 1, the main contribution comes from the bond lines with carbon and hydrogen in the water adsorbed by the sample. In samples 2-4 there are two lines (530.2 eV and 531.7 eV) associated with iron in the oxide and hydroxide [

56]. In the sample obtained at an annealing temperature of 200°C, the line corresponding to the hydroxide is more pronounced.

From the data obtained, it can be concluded that a layer of Fe2O3 is formed on the surface of the carbon nanotube array at all annealing temperatures (200, 300 and 400°C). The optimum annealing temperature is 300°C and above.

3.1. Study of the Electrochemical Properties of Fe2O3/MWCNT/Al Composites

A series of electrochemical measurements were carried out to investigate the possibility of using the obtained Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al material as supercapacitors electrodes. The ability of a system to accumulate charge is usually determined by the specific capacitance (C

spm) of the electrode materials and is calculated from data obtained by cyclic voltammetry (CVs) methods [

57]. A common unit of measurement for specific capacitance is F/g. The specific capacitance for the CVs method is calculated using equation (1).

In expression (1), ∫IdV is the total area under the CV curve, i.e., the accumulated charge, ΔV is the voltage range (V); ν is the scan rate (V/s), mel is the mass of the active material on the working surface of the electrode.

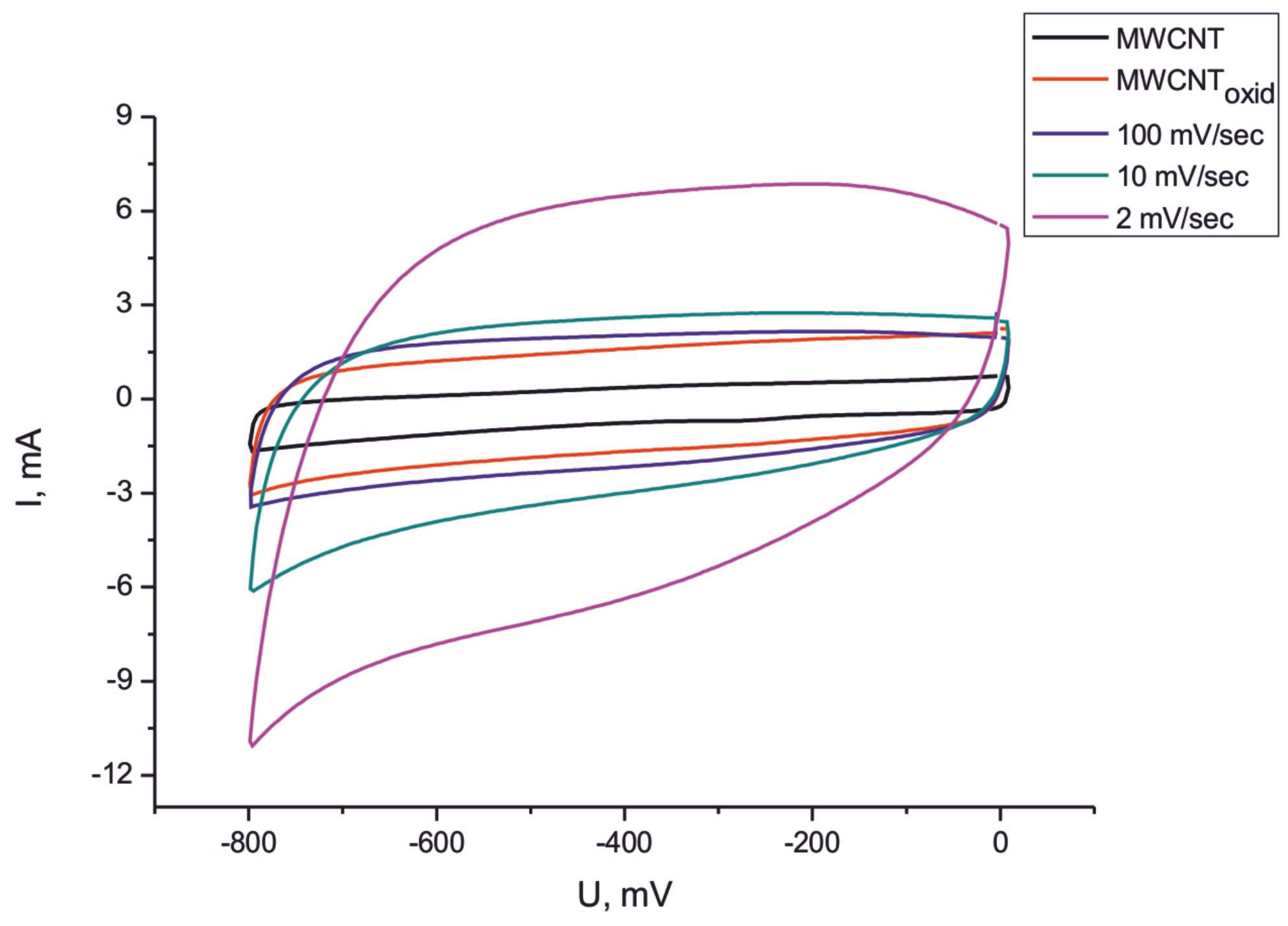

The cyclic voltammetry method showed a significant increase in the capacitance of the MWCNT/Al samples after the formation of the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al composite material.

Figure 6 shows examples of cyclic voltammograms for the initial MWCNT/Al samples, the electrochemically oxidised samples and the composite material obtained at different voltage sweep rates.

From the plots shown in

Figure 6, it is clear that the specific capacitance of the composite material is significantly higher than that of the original MWCNT/Al sample. From the CVs results it can be concluded that the maximum increase in specific capacitance was achieved for the sample obtained at a voltage sweep rate of 2 mV/s (175 F/g at a scan rate of 100 mV/s). No significant increase in specific capacitance was observed as the voltage sweep rate was increased. At 10 mV/s, the specific capacitance increased by a factor of about 3, and at 100 mV/s by a factor of about 2. The increase in the specific capacitance of the composite material is due to the pseudocapacitive properties of the iron oxide. Redox reactions take place at the electrode surface. Since an aqueous solution of sodium sulphate is used as the electrolyte, the charge storage mechanism can be described by the following equations [

58,

59]:

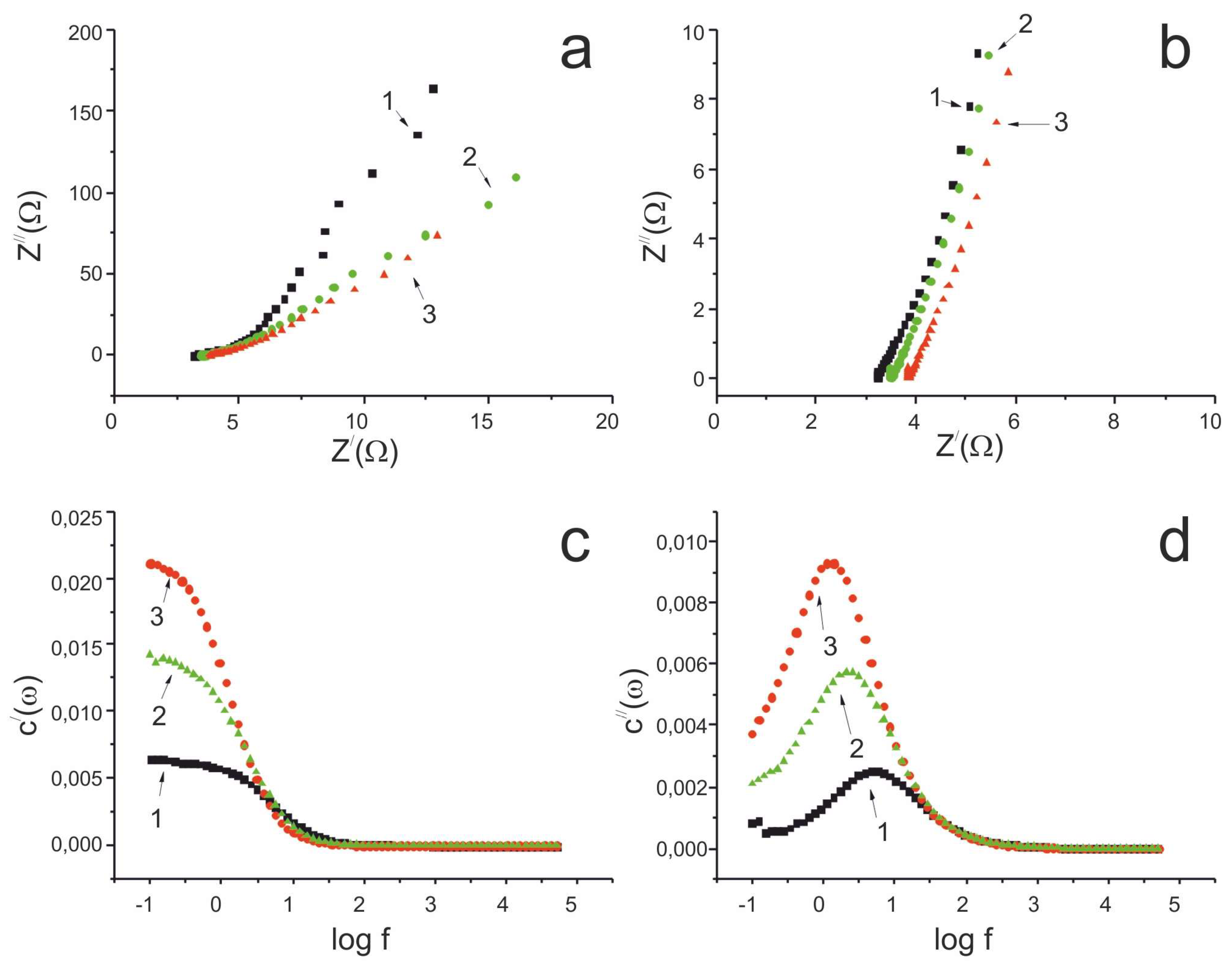

The electrochemical properties of the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al electrodes were further investigated using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

Figure 7a, b shows the Nyquist plots of the original MWCNT/Al sample, the pre-oxidised MWCNT/Al sample and the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al sample formed at a voltage sweep rate of 2 mV/s. The use of a Randles-like equivalent circuit is optimal for the obtained material [

60,

61,

62].

In the low frequency range, the Nyquist plots for the initial, oxidised and composite Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al samples were almost linear, indicating good capacitive characteristics (

Figure 7a). The ohmic resistance of the initial MWCNT/Al sample was 3.2 ohms, which increased to 3.5 ohms after electrochemical oxidation in a Na

2SO

4 solution. Further deposition of Fe

2O

3 on the MWCNT surface did not significantly increase the ohmic resistance (3.85 ohms). As a result, the Fe

2O

3 in the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al composite electrode has good electrical contact with the conductive substrate. At the same time, the slope of the Nyquist plot for the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al sample decreased in the low frequency region compared to the original MWCNT/Al sample (

Figure 7a), which can be explained by the pseudocapacitive properties of Fe

2O

3.

The frequency dependence of the actual capacitance confirms an increase in the electrode capacitance of about 1.5 times after electrochemical oxidation and about 5 times after Fe

2O

3 deposition (

Figure 7c). The study showed that during the anodic oxidation of MWCNTs, the increase in the specific capacity of the material is due to the increase in oxygen-containing groups covalently bonded to the surface of the nanotubes. Another reason is the increase in porosity and specific surface area of the MWCNTs resulting from the electrochemical etching of the nanotube surface [

45]. The specific capacitance of the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al composite increases due to the oxidation-reduction reactions taking place on the surface of the electrode (2) and (3). The imaginary capacitance dependence curves have maxima, the position of which characterises the charge/discharge rate. The τ

r value for the initial MWCNT/Al electrode was 0.22 s; for the oxidised sample - 0.48 s; for the final Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al sample - 0.88 s. Pseudocapacitance limits rapid charge/ion transfer and results in a long response time. Therefore, the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al electrode has a higher τ

r value of 0.88s. However, when applied to pseudocapacitors, this value indicates very good charge/discharge characteristics of the resulting binder-free composite electrodes [

63].

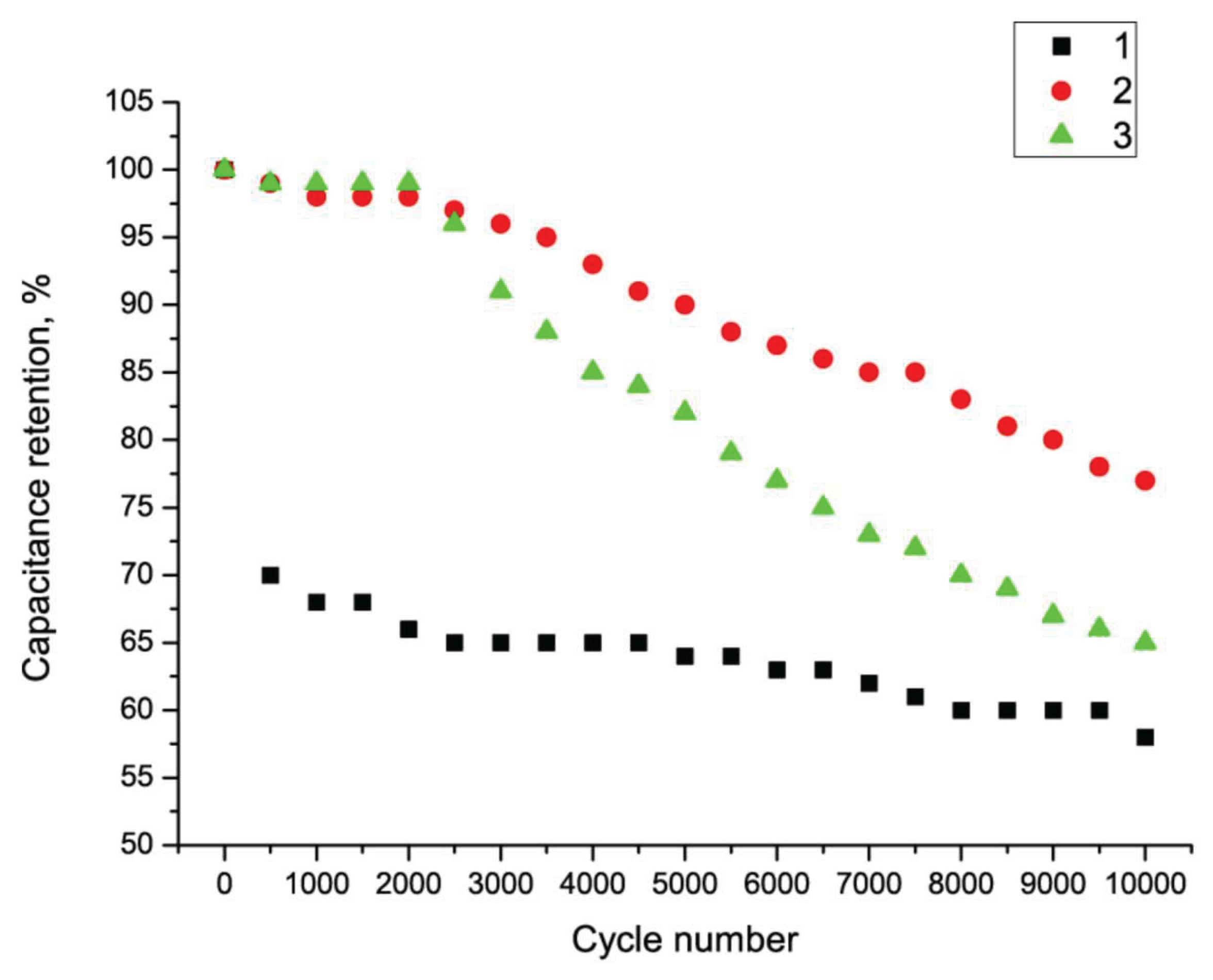

An important feature of SC electrodes is their resistance to multiple charge/discharge cycles. A series of measurements were taken at different annealing temperatures of the composite.

Figure 8 shows the resistance of the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al composite to multiple charge/discharge cycles as a function of annealing temperature.

Figure 8 shows that the Fe

2O

3/MWCNT/Al composite exhibited the highest cycle resistance at an annealing temperature of 300°C. Such results suggest that annealing temperatures below 300°C may not be sufficient to convert iron hydroxide to oxide. On the other hand, the MWCNT layer can be destroyed at a temperature of 400°C.

4. Conclusions

In summary, binder-free electrodes increase the specific capacitance of the supercapacitor and also exhibit high response speed and cyclic stability. A method for the preparation of a binder-free Fe2O3/MWCNT/Al composite electrode has been developed. The aluminum substrate has excellent electrical conductivity, low specific gravity and low cost. Excellent adhesion of the MWCNT layer to the substrate ensures good electrical contact between all electrode components. For the first time, conditions for the electrochemical oxidation of MWCNTs grown directly on the surface of aluminum foil were selected to allow the formation of a Fe2O3/MWCNT/Al composite. Fe2O3/MWCNT/Al electrodes without binder were obtained by electrochemical oxidation of MWCNT/Al samples in a mixture of aqueous solutions (Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 0.1 M and CH3COONa 0.08 M).

Optimal processing conditions have been selected to ensure a significant increase in electrode capacitance, while protecting the MWCNT layer and substrate from damage. Electrochemical oxidation of MWCNT/Al samples in an aqueous solution (Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2 0.1 M and CH3COONa 0.08 M) at a voltage sweep rate of 2 mV/s followed by annealing at 300°C increases the specific capacitance of the active material of the samples by a factor of 5 to 175 F/g. At the same time, excellent adhesion and electrical contact of the work material to the aluminum substrate is maintained. The Fe2O3/MWCNT/Al electrodes obtained have a high resistance to multiple charge/discharge cycles. After 10,000 cycles, the capacitance loss does not exceed 25%.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N.R.; methodology, A.A.M.; investigation, A.A.M., E.E.Y., M.A.K. and V.I.K; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.A.M., E.E.Y., M.A.K. and V.I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, grant number 24-22-00240.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dissanayake K., Kularatna-Abeywardana D. A review of supercapacitors: Materials, technology, challenges, and renewable energy applications. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 96, 112563. [CrossRef]

- Blaabjerg F., Ionel D. M. Renewable energy devices and systems–state-of-the-art technology, research and development, challenges and future trends. Electric Power Components and Systems 2015, 43, 1319-1328. [CrossRef]

- Zeng T. et al. Scalable Hybrid Films of Polyimide-Animated Quantum Dots for High-Temperature Capacitive Energy Storage Utilizing Quantum Confinement Effect. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 2419278. [CrossRef]

- Zhan Y. et al. Enhancing prediction of electron affinity and ionization energy in liquid organic electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries using machine learning. Journal of Power Sources 2025, 629, 235992. [CrossRef]

- Chen X. et al. Lithium insertion/extraction mechanism in Mg2Sn anode for lithium-ion batteries. Intermetallics 2024, 169, 108306. [CrossRef]

- Cao M. et al. Cross-linked K2Ti4O9 nanoribbon arrays with superior rate capability and cyclability for lithium-ion batteries. Materials Letters 2020, 279, 128495. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J., Gu M., Chen X. Supercapacitors for renewable energy applications: A review. Micro and Nano Engineering 2023, 100229. [CrossRef]

- Ariyarathna T. et al. Development of supercapacitor technology and its potential impact on new power converter techniques for renewable energy. IEEE journal of emerging and selected topics in industrial electronics 2021, 2, 267-276. [CrossRef]

- Olabi A. G. et al. Supercapacitors as next generation energy storage devices: Properties and applications. Energy 2022, 248, 123617. [CrossRef]

- Attia S. Y. et al. Supercapacitor electrode materials: addressing challenges in mechanism and charge storage. Reviews in Inorganic Chemistry 2022, 42, 53-88. [CrossRef]

- Gao L. et al. Zinc selenide/cobalt selenide in nitrogen-doped carbon frameworks as anode materials for high-performance sodium-ion hybrid capacitors. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials 2024, 7, 144. [CrossRef]

- Yadav M. S. Metal oxides nanostructure-based electrode materials for supercapacitor application. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2020, 22, 367. [CrossRef]

- Ansari M. Z. et al. Critical aspects of various techniques for synthesizing metal oxides and fabricating their composite-based supercapacitor electrodes: a review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1873. [CrossRef]

- Phakkhawan A. et al. Reagent-and solvent-mediated Fe2O3 morphologies and electrochemical mechanism of Fe2O3 supercapacitors. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2022, 919, 165702. [CrossRef]

- Shivakumara S., Penki T. R., Munichandraiah N. High specific surface area α-Fe2O3 nanostructures as high performance electrode material for supercapacitors. Materials Letters 2014, 131, 100-103. [CrossRef]

- Nithya V. D., Arul N. S. Progress and development of Fe3O4 electrodes for supercapacitors. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2016, 4, 10767-10778. [CrossRef]

- Barik R., Jena B. K., Mohapatra M. Metal doped mesoporous FeOOH nanorods for high performance supercapacitors. RSC advances 2017, 7, 49083-49090. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H. et al. Controllable design of polycrystalline synergies: hybrid FeOx nanoparticles applicable to electrochemical sensing antineoplastic drug in mammalian cells. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2018, 275, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Kumbhar V. S. et al. Chemical synthesis of spinel cobalt ferrite (CoFe2O4) nano-flakes for supercapacitor application. Applied Surface Science 2012, 259, 39-43. [CrossRef]

- Owusu K. A. et al. Low-crystalline iron oxide hydroxide nanoparticle anode for high-performance supercapacitors. Nature communications 2017, 8, 14264. [CrossRef]

- Lorkit P., Panapoy M., Ksapabutr B. Iron oxide-based supercapacitor from ferratrane precursor via sol–gel-hydrothermal process. Energy Procedia 2014, 56, 466-473. [CrossRef]

- Yadav A. A. et al. Chemically synthesized iron-oxide-based pure negative electrode for solid-state asymmetric supercapacitor devices. Materials 2022, 15, 6133. [CrossRef]

- Zeng Y. et al. Iron-based supercapacitor electrodes: advances and challenges. Advanced Energy Materials 2016, 6, 1601053. [CrossRef]

- Xu B. et al. Iron oxide-based nanomaterials for supercapacitors. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 204002. [CrossRef]

- Samuel E. et al. Flexible and freestanding manganese/iron oxide carbon nanofibers for supercapacitor electrodes. Ceramics International 2022, 48, 18374-18383. [CrossRef]

- Ishaq S. et al. One step strategy for reduced graphene oxide/cobalt-iron oxide/polypyrrole nanocomposite preparation for high performance supercapacitor electrodes. Electrochimica Acta 2022, 427, 140883. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao C., Lee C., Tai N. Reduced graphene oxide/oyster shell powers/iron oxide composite electrode for high performance supercapacitors. Electrochimica Acta 2021, 391, 138868. [CrossRef]

- Tundwal A. et al. Developments in conducting polymer-, metal oxide-, and carbon nanotube-based composite electrode materials for supercapacitors: a review. RSC advances 2024, 14. 9406-9439. [CrossRef]

- Baby A. et al. Hybrid architecture of Multiwalled carbon nanotubes/nickel sulphide/polypyrrole electrodes for supercapacitor. Materials Today Sustainability 2024, 26, 100727. [CrossRef]

- Gerard O. et al. Fast and green synthesis of battery-type nickel-cobalt phosphate (NxCyP) binder-free electrode for supercapattery. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 497 154842. [CrossRef]

- Kumbhar M. B. et al. Enhancing energy storage with binder-free nickel oxide cathodes in flexible hybrid asymmetric solid-state supercapacitors. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2025, 1010, 177311. [CrossRef]

- Avasthi P., Kumar A., Balakrishnan V. Aligned CNT forests on stainless steel mesh for flexible supercapacitor electrode with high capacitance and power density. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2019, 2, 1484-1495. [CrossRef]

- Hussain S., Amade R., Moreno H., Bertran E. RF-PECVD growth and nitrogen plasma functionalization of CNTs on copper foil for electrochemical applications. Diamond Relat. Mater 2014, 49, 55–61. [CrossRef]

- Vicentini R. et al. Direct growth of mesoporous Carbon on aluminum foil for supercapacitors devices. Journal of materials Science: materials in electronics 2018, 29, 10573-10582. [CrossRef]

- Ghai V., Chatterjee K., Agnihotri P. K. Vertically aligned carbon nanotubes-coated aluminium foil as flexible supercapacitor electrode for high power applications. Carbon Letters 2021, 31, 473-481. [CrossRef]

- Das H. T. et al. Recent trends in carbon nanotube electrodes for flexible supercapacitors: a review of smart energy storage device assembly and performance. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 223. [CrossRef]

- Kanwade A. et al. A review on synergy of transition metal oxide nanostructured materials: Effective and coherent choice for supercapacitor electrodes. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105692. [CrossRef]

- Liu R. et al. Fundamentals, advances and challenges of transition metal compounds-based supercapacitors. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 412, 128611. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood D., Lim K., Patsios C., Lyons P., Lim Y., Taylor P. Frequency response services designed for energy storage. Appl. Energy 2017, 203, 115–127. [CrossRef]

- Tian Y. et al. Accessing the O Vacancy with Anionic Redox Chemistry Toward Superior Electrochemical Performance in O3 type Na-Ion Oxide Cathode. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 34, 2316342. [CrossRef]

- Li X. et al. Effect of microstructure on electrochemical performance of electrode materials for microsupercapacitor. Materials Letters 2023, 346, 134481. [CrossRef]

- Bai Y., Wang W., Wang R., Sun J., Gao L. Controllable synthesis of 3D binary nickel-cobalt hydroxide/graphene/nickel foam as a binder-free electrode for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 12530–12538. [CrossRef]

- Wang J., Li C., Yang Z., Chen D. Chemical vapor deposition-assisted fabrication of a graphene-wrapped MnO/carbon nanofibers membrane as a high-rate and long-life anode for lithium ion batteries. RSC Adv 2017, 7, 50973–50980. [CrossRef]

- Redkin A. N., Mitina A. A., Yakimov E. E. Simple technique of multiwalled carbon nanotubes growth on aluminum foil for supercapacitors. Materials Science & Engineering B 2021, 272, 115342. [CrossRef]

- Redkin A.N., Mitina A.A., Yakimov E.E., Kabachkov E.N. Electrochemical Improvement of the MWCNT/Al Electrodes for Supercapacitors. Materials 2021, 14, 7612. [CrossRef]

- Meng X. et al. Fe2O3 nanoparticles anchored on thermally oxidized MWCNTs as anode material for lithium-ion battery. Nanotechnology 2022, 34, 015602. [CrossRef]

- Rokade A. et al. Realization of electrochemically grown a-Fe2O3 thin films for photoelectrochemical water splitting application. Engineered Science 2021, 17, 242-255. [CrossRef]

- Roy D. et al. Analysis of carbon-based nanomaterials using Raman spectroscopy: principles and case studies. Bulletin of Materials Science 2021, 31. [CrossRef]

- Li W., Zhang H., Wang C., Zhang Y., Xu L., Zhu K., Xie S. Raman Characterization of Aligned Carbon Nanotubes Produced by Thermal Decomposition of Hydrocarbon Vapor. Appl. Phys. Lett 1997, 70, 2684. [CrossRef]

- De Faria D. L. A., Venâncio Silva S., de Oliveira M. T. Raman microspectroscopy of some iron oxides and oxyhydroxides. Journal of Raman spectroscopy 1997, 28, 873-878. [CrossRef]

- Lohaus C. et al. Systematic investigation of the electronic structure of hematite thin films. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2017, 4, 1700542. [CrossRef]

- Marshall C. P., Stockdale G., Carr C. A. Raman Spectroscopy of Geological Varieties of Hematite of Varying Crystallinity and Morphology. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita T., Hayes P. Analysis of XPS spectra of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions in oxide materials. Applied surface science 2008, 254, 2441-2449. [CrossRef]

- Chen X., Wang X., Fang D. A review on C1s XPS-spectra for some kinds of carbon materials. Fullerenes, Nanotubes and Carbon Nanostructures 2020, 28, 1048-1058. [CrossRef]

- Orisekeh K. et al. Processing of α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles on activated carbon cloth as binder-free electrode material for supercapacitor energy storage. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 33, 102042. [CrossRef]

- Li M., He H. Study on electrochemical performance of multi-wall carbon nanotubes coated by iron oxide nanoparticles as advanced electrode materials for supercapacitors. Vacuum 2017, 143, 371-379. [CrossRef]

- Stoller M. D., Ruoff R. S. Best practice methods for determining an electrode material’s performance for ultracapacitors. Energy & Environmental Science 2010, 3, 1294-1301. [CrossRef]

- Abdi A., Trari M. Investigation on photoelectrochemical and pseudo-capacitance properties of the non-stoichiometric hematite α-Fe2O3 elaborated by sol–gel. Electrochimica Acta 2013, 111, 869-875. [CrossRef]

- Toupin M., Brousse T., Bélanger D. Charge storage mechanism of MnO2 electrode used in aqueous electrochemical capacitor. Chemistry of Materials 2004, 16, 3184-3190. [CrossRef]

- Moya A. A. Identification of characteristic time constants in the initial dynamic response of electric double layer capacitors from high-frequency electrochemical impedance. Journal of Power Sources 2018, 397, 124-133. [CrossRef]

- Devillers N. et al. Review of characterization methods for supercapacitor modeling. Journal of Power Sources 2014, 246, 596-608. [CrossRef]

- Mainka J. et al. A General Equivalent Electrical Circuit Model for the characterization of MXene/graphene oxide hybrid-fiber supercapacitors by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy–Impact of fiber length. Electrochimica Acta 2022, 404, 139740. [CrossRef]

- Perdana M. Y. et al. Understanding the Behavior of Supercapacitor Materials via Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy: A Review. The Chemical Record 2024, 24, e202400007. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).