Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Effect of Tensile Strain Conditions on Mass Loss

2.1. Materials and Methods

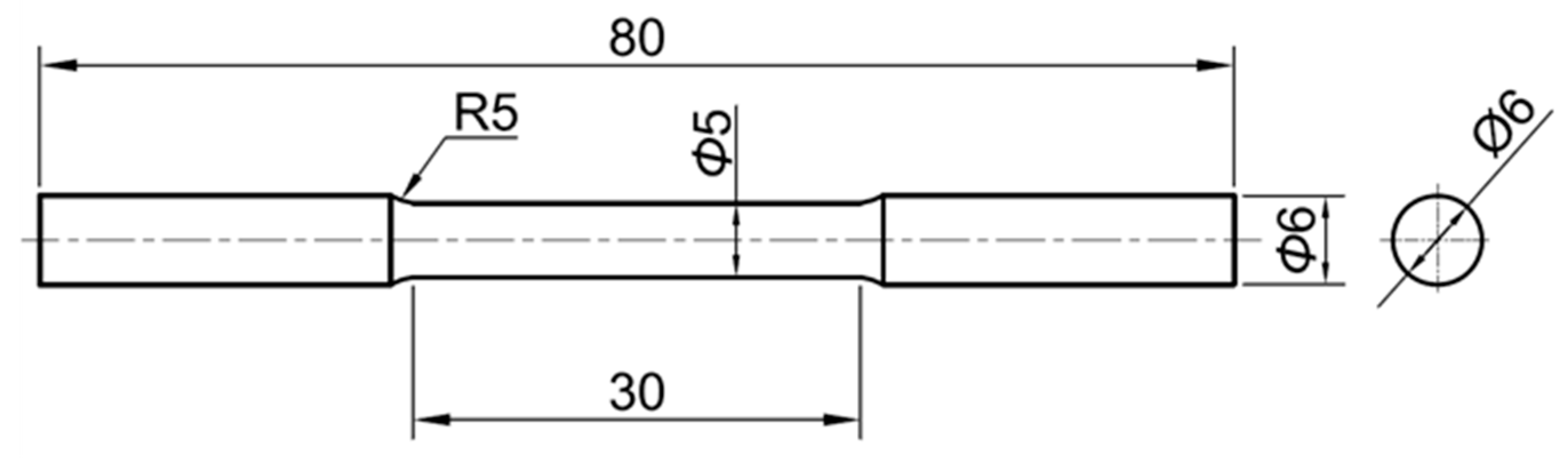

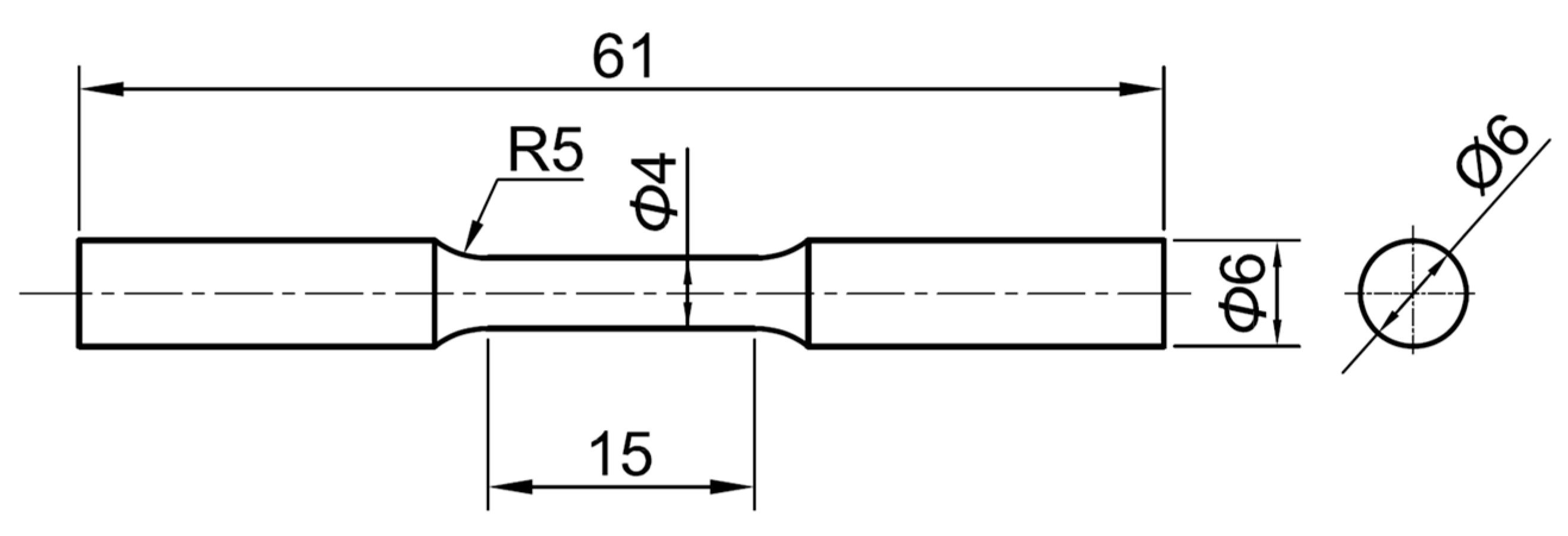

2.1.1. Specimens

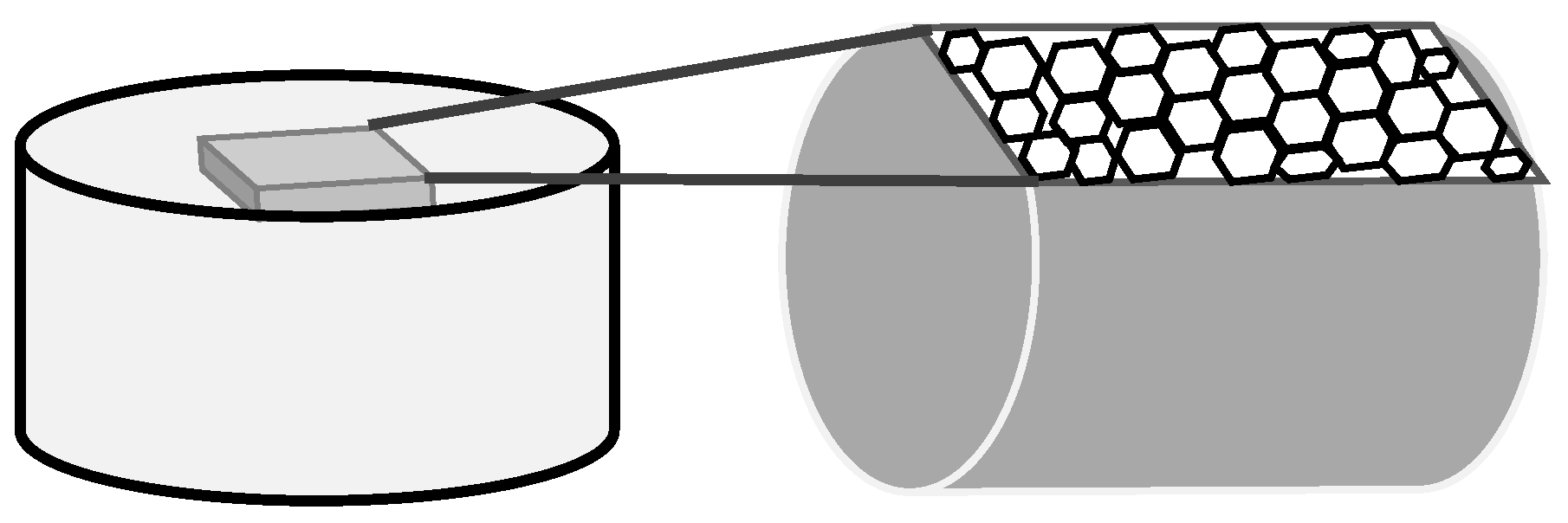

2.1.2. Experimental Procedure

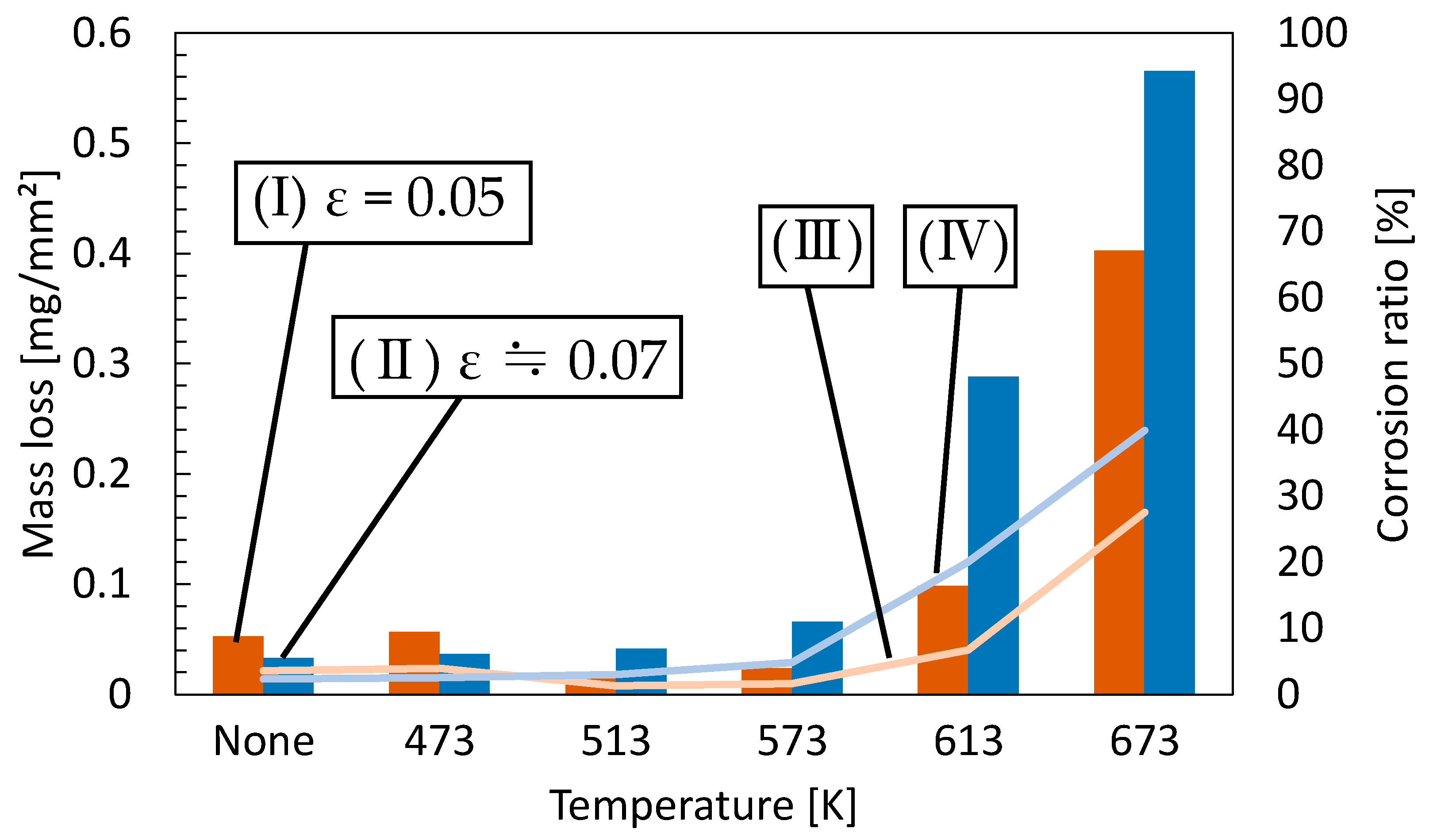

2.2. Results and Discussions of Tensile Strain

2.2.1. Corrosion Immersion Test

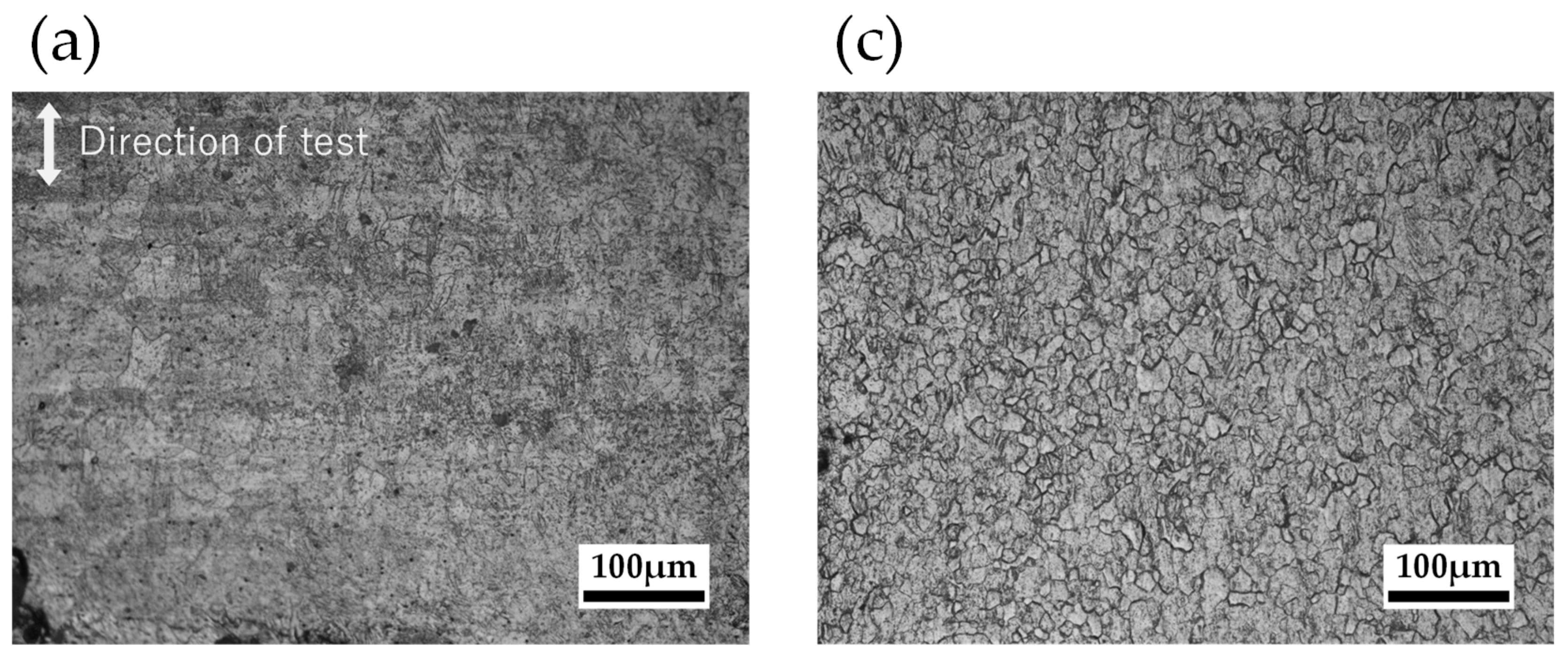

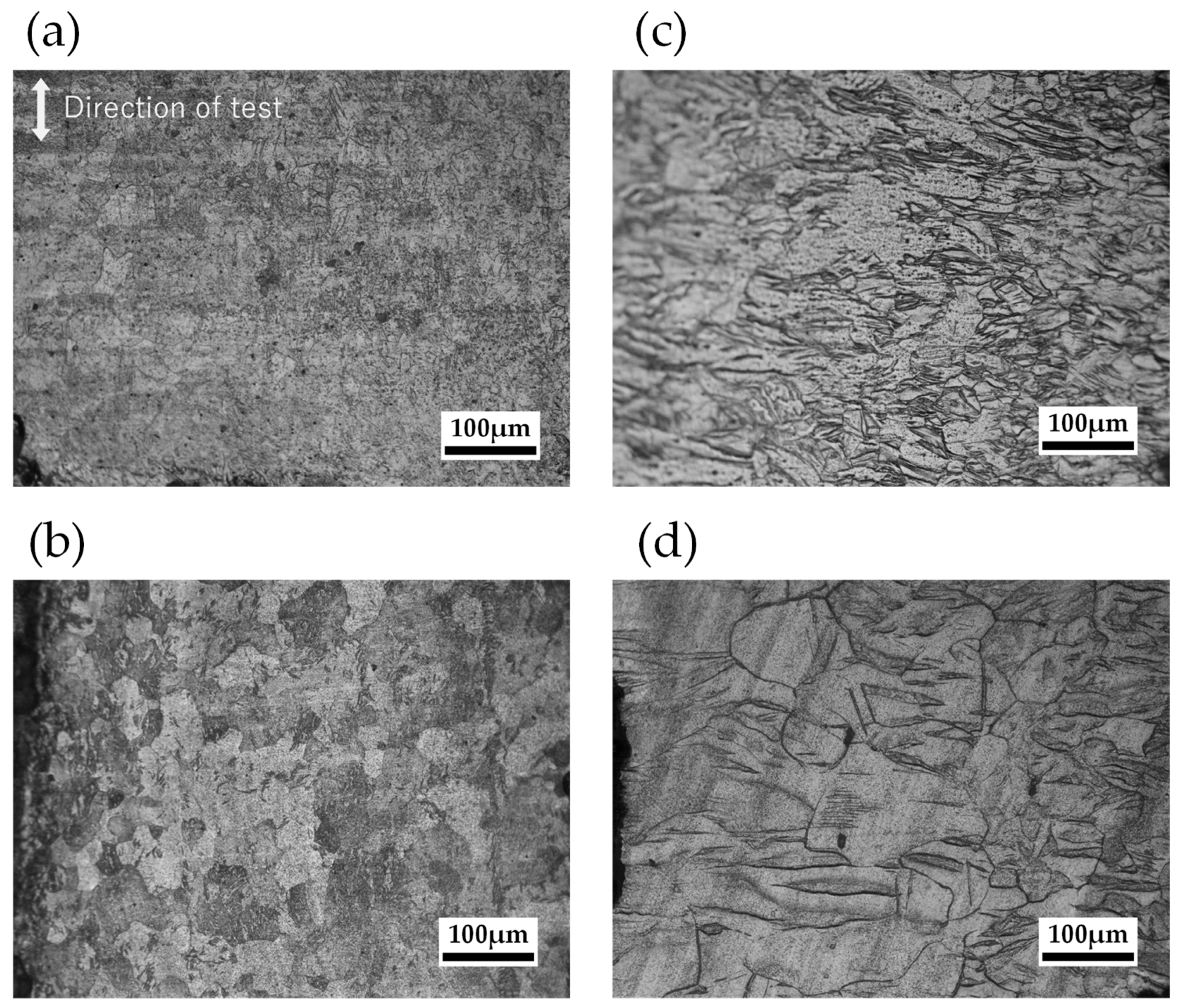

2.2.2. Grain Size Observation

3. Effect of Compressive Strain Conditions on Mass Loss

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Specimens

3.1.2. Experimental Procedure

3.2. Results and Discussions of Compressive Strain

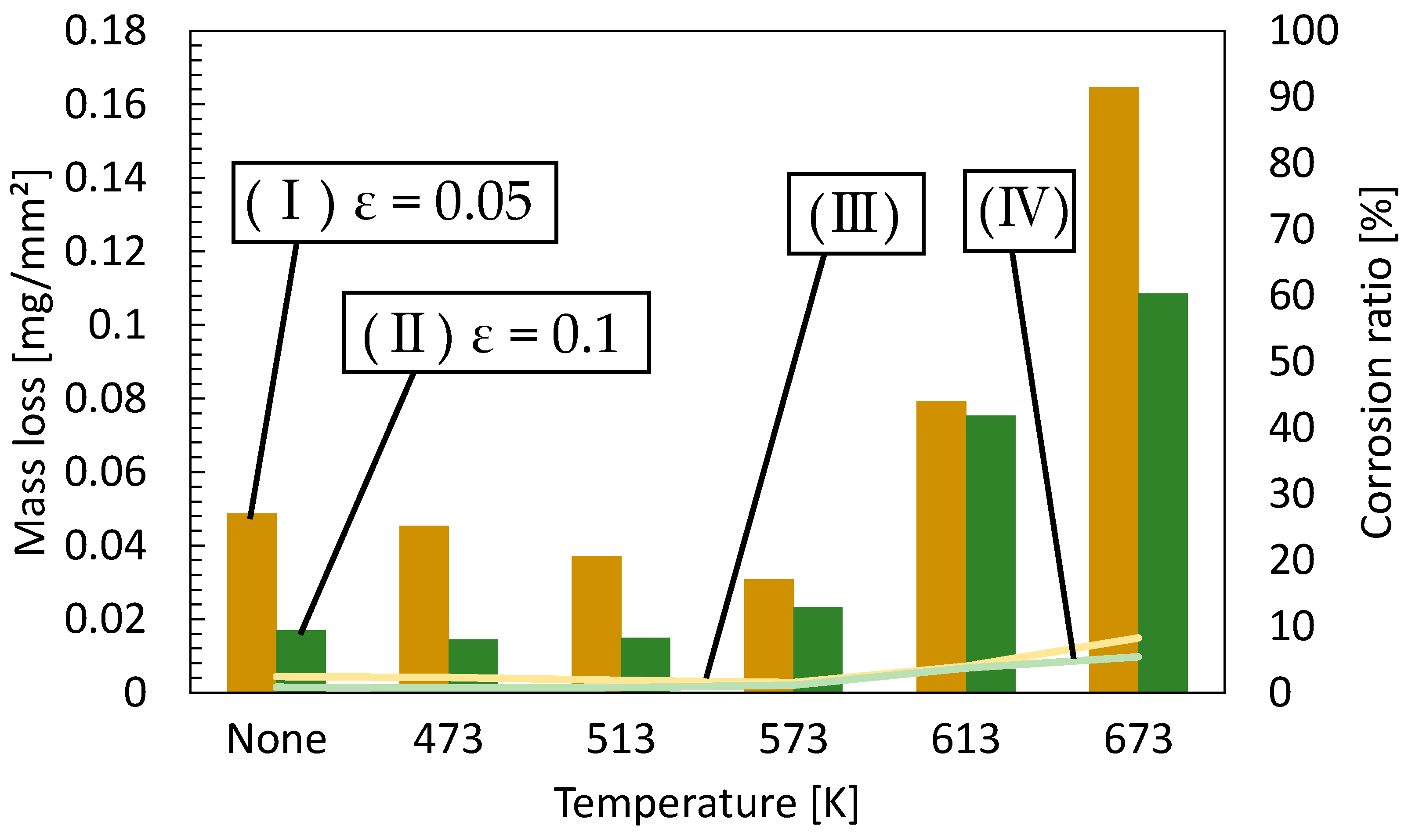

3.2.1. Corrosion Immersion Test

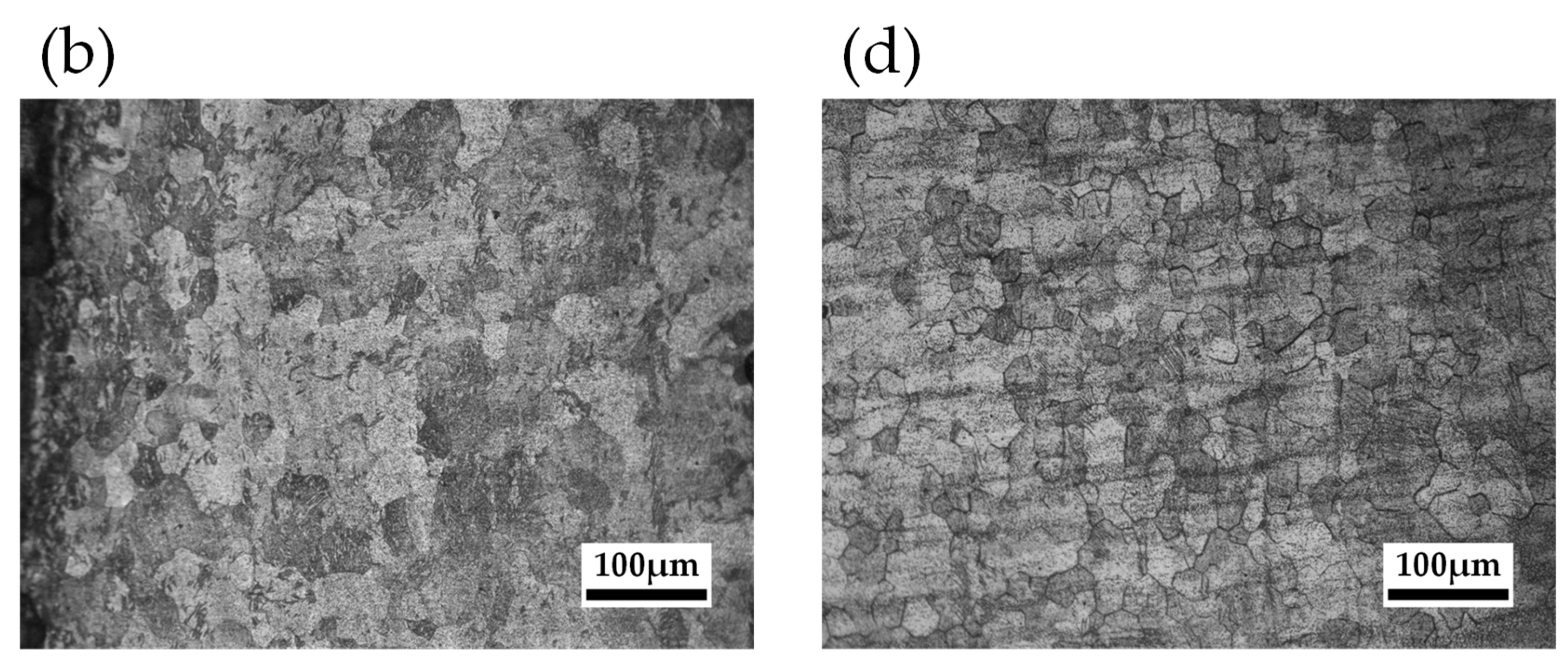

3.2.2. Grain Size Observation

3.3. Comparison of Tensile and Compressive Strain

4. Effect of Cyclic Tensile-Compressive Stress Conditions on Mass Loss

4.1. Materials and Methods

4.1.1. Specimens

4.1.2. Experimental Methods

4.2. Results and Discussions of Tensile-Compressive Stress

4.2.1. Corrosion Immersion Test

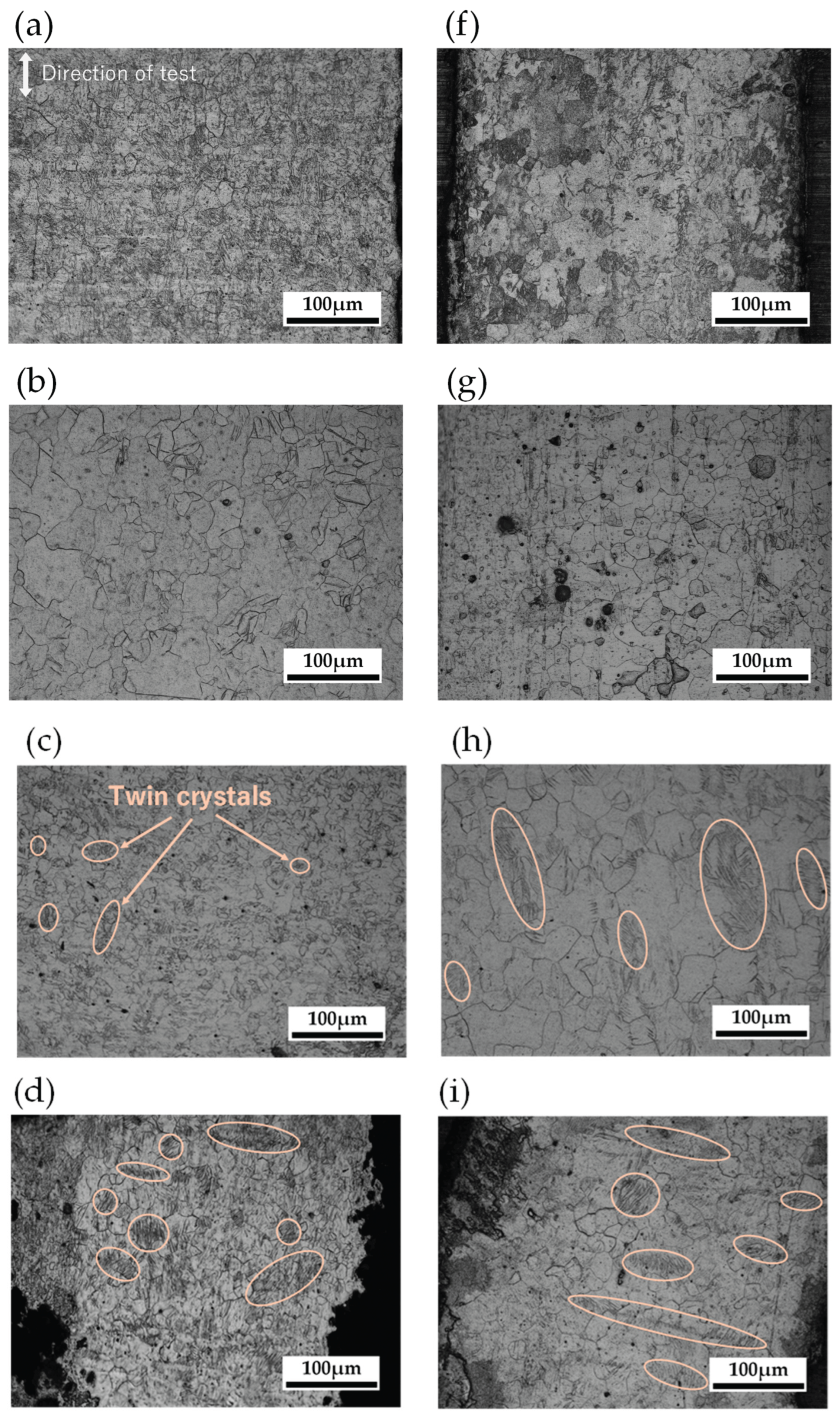

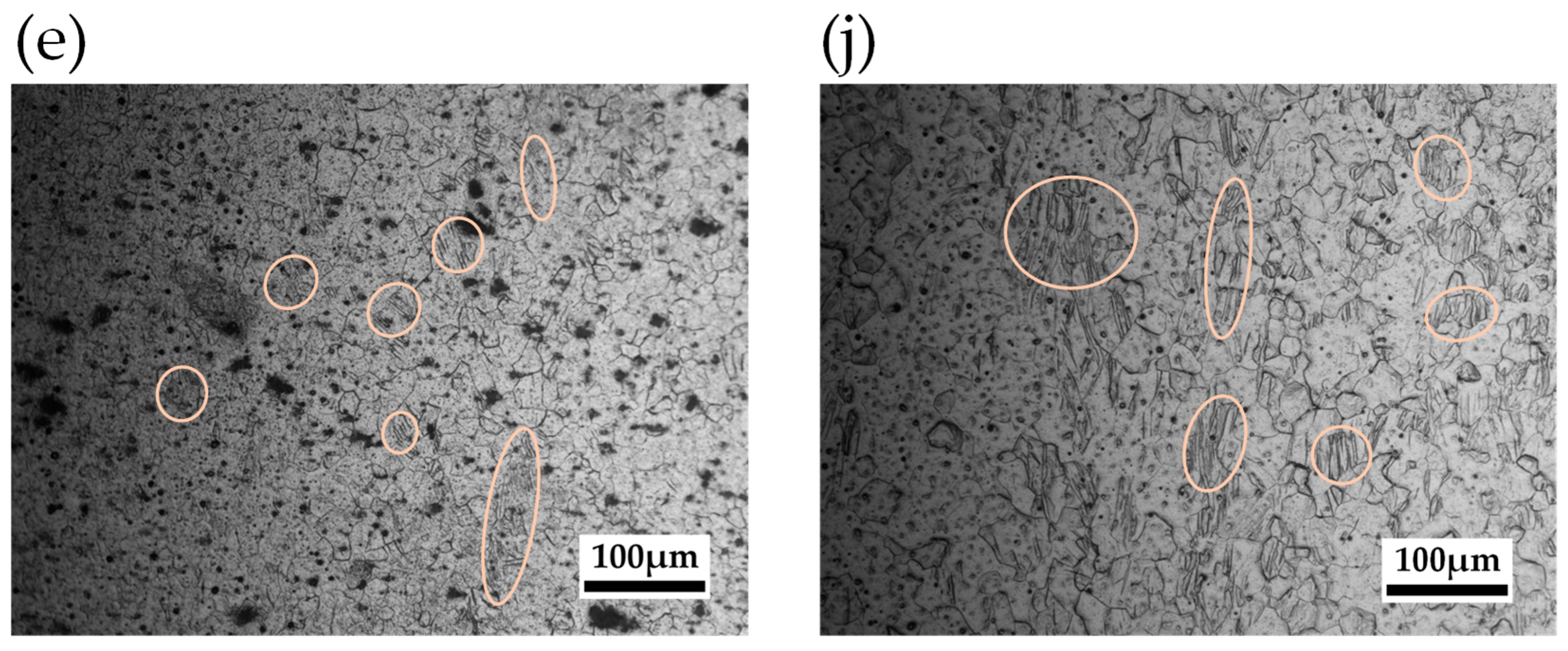

4.2.2. Grain Size Observation

5. Conclusion

- Samples with a tensile strain of 0.05 had fewer dislocations in the material than those with a tensile strain of 0.07, which is considered to have reduced mass loss. Furthermore, the mass loss of the specimens with small grain diameters at annealing temperatures around 500 K was lower than that of the 673 K specimens with coarse grains. This phenomenon improved corrosion resistance since grain boundaries increased and dense corrosion products were generated by the recrystallization of the annealing process.

- The specimens subjected to a compressive strain of 0.1 exhibited better corrosion resistance than those at 0.05 strain due to the formation of twin crystals, producing denser corrosion products. Additionally, the test pieces heat-treated at temperatures near 500 K had smaller diameter grains than those treated at 673 K, and hence, the magnitude of mass loss decreased.

- Slip deformation of dislocations occurs mainly in tensile deformation of pure magnesium, while twin deformation predominantly occurs in compressive de-formation. The growth of dislocation density by tensile deformation has accelerated the corrosion rate of pure magnesium. In particular, the results have shown that dislocations generated inside the coarse-grained material have a higher effect on the corrosion resistance of the material than dislocations in the fine-grained material. Twinning might be considered to act to improve the corrosion resistance of the material regardless of the annealing temperature.

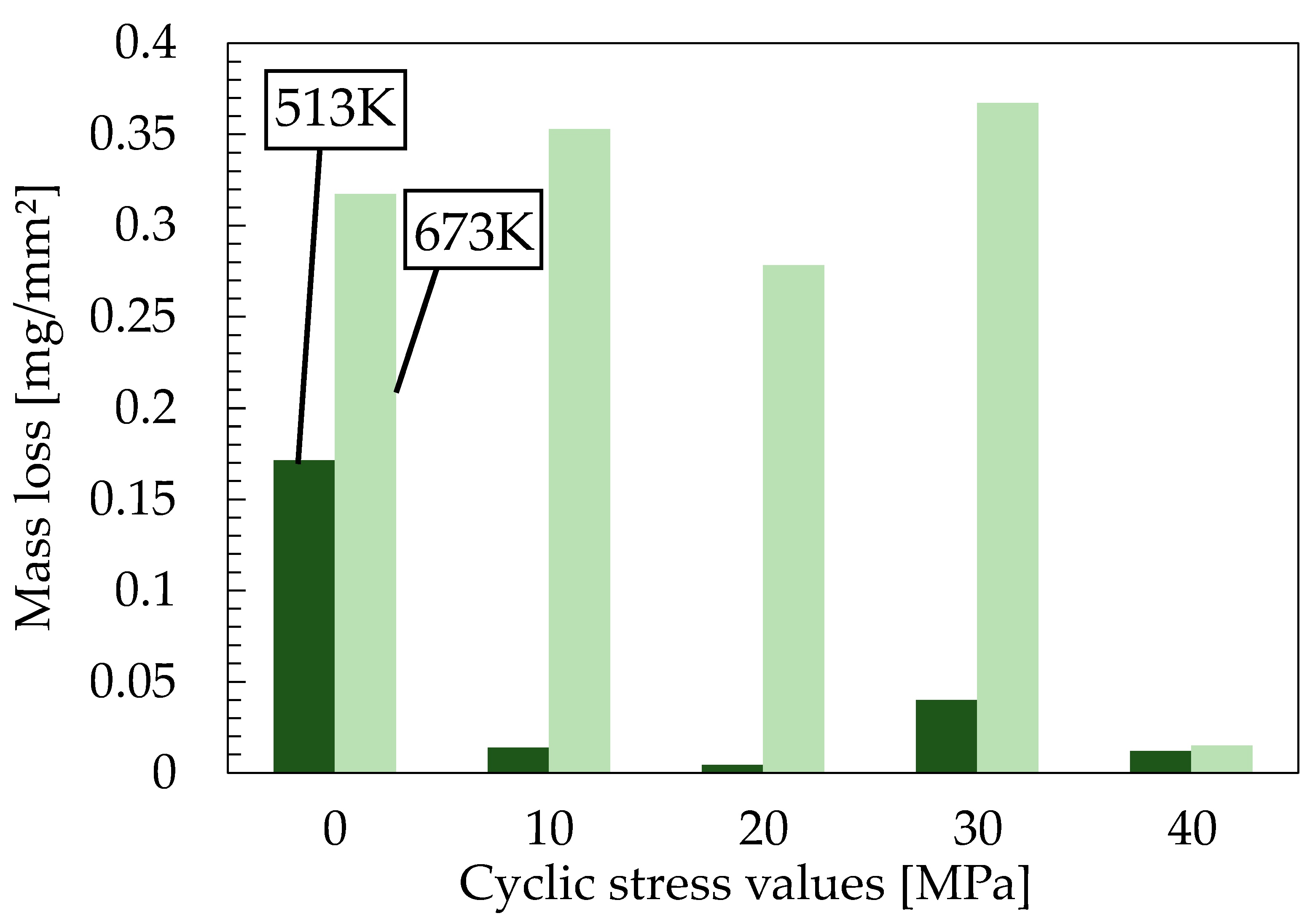

- Twinning is formed inside the material when pure magnesium is subjected to cyclic compressive and tensile stresses. Mass loss at a cyclic stress of 20 MPa is considered to have decreased because of the action of the twin crystals formed. The specimens tested at a cyclic stress of 30 MPa had increased mass loss due to the possibility of twinning-detwinning being converted to dislocations in fatigue tests under high-stress amplitudes. Specimens that fail by fatigue testing could have dislocations inside the material reduced because the dislocations are released or the crack penetrates the dislocations during crack initiation. Thus, specimens subjected to a cyclic stress of 40 MPa had improved corrosion resistance. Regardless of the cyclic stress, the test pieces at an annealing temperature of 513 K showed better corrosion resistance than those at 673 K.

Acknowledgments

References

- Daniel, L.; Stefan, J. Bioresorbable Stents in PCI. Supring journal 2016, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stefan, K.J.; Ulf, S.; Johan, L.; Jörg, C.; Fredrik, S.; Tage, N.; Lars, W.; Bo, L. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Drug-Eluting versus Bare-Metal Stents in Sweden. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1933–1945. [Google Scholar]

- Wansong, H.; Jun, J. Hypersensitivity and in-stent restenosis in coronary stent materials. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dario, B.; Davide, P.; Giuseppe, A.; Bernardo, C. Understanding and managing in-stent restenosis: a review of clinical data, from pathogenesis to treatment. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.L.; Hung, P.L.; Ming, L.Y. Characterization of a Sandwich PLGA-Gallic Acid-PLGA Coating on Mg Alloy ZK60 for Bioresorbable Coronary Artery Stents. J. Mater. 2020, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jiayin, F.; Yingchao, S.; Yi, X.Q.; Yufeng, Z.; Yadong, W.; Donghui, Z. Evolution of metallic cardiovascular stent materials: A comparative study among stainless steel, magnesium and zinc. BMs 2020, 230, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, P.S.; Alexis, M.P.; Jerawala, H.; George, D. Magnesium and its alloys as orthopedic biomaterials: A review. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 1728–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ron, W.; Raimund, E.; Carlo, D.M.; Jozef, B.; Bernard, d.B.; Franz, R.E.; Paul, E.; Michael, H.; Mark, H.; Charles, I.; Dirk, B.; Hans, B.; Jacques, K.; Thomas, F.L.; Neil, J.W. Early- and Long-Term Intravascular Ultrasound and Angiographic Findings After Bioabsorbable Magnesium Stent Implantation in Human Coronary Arteries. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 312–320. [Google Scholar]

- Raimund, E.; Carlo, D.M.; Jozef, B.; Johann, B.; Bernard, d.B.; Franz, R.E.; Paul, E.; Michael, H.; Bernd, H.; Mark, H.; Charles, I.; Dirk, B.; Jacques, K.; Thomas, F.L.; Neil, W.; Ron, W. Temporary scaff olding of coronary arteries with bioabsorbable magnesium stents: a prospective, non-randomised multicentre trial. Lancet 2007, 369, 1869–1875. [Google Scholar]

- Sasak, M.; Wei, X.; Koga, Y.; Okazawa, Y.; Wada, A.; Shimizu, I.; Niidome, T. Effect of Parylene C on the Corrosion Resistance of Bioresorbable Cardiovascular Stents Made of Magnesium Alloy ‘Original ZM10’. J. Mater. 2022, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.Z.; Yong, X.Y.; Jing, A.L.; Rong, C.Z.; Shao, K.G. Advances in coatings on magnesium alloys for cardiovascular stents - A review. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 4729–4757. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang, K.; Markus, D.; Frank, B.; Klaus, P.; Niels, G.; Olaf, K. In-situ investigation of stress conditions during expansion of baremetal stents and PLLA-coated stents using the XRD sin2 ψ-technique. Science Direct 2015, 49, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zongmin, M.; Heyan, D.; Min, Q. A Study on Fatigue test for Cardiovascular Stent. Mech. Mater. 2012, 157–158, 197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Shoichi, K.; Takashi, H.; Soichiro, E.; Tomohiro, S.; Masashi, I.; Toru, M.; Takenori, D.; Kyohei, Y.; Yoshimitsu, S.; Makoto, H.; Shinichi, S.; Kenji, A. Incidence and Clinical Impact of Stent Fracture After PROMUS Element Platinum Chromium Everolimus-Eluting Stent Implantation. JACC Cardiovasc. 2015, 8, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Haidong, F.; Sylvie, A.; Athanasios, A.; Jaafar, A.E.A. Grain size effects on dislocation and twinning mediated plasticity in magnesium. Scr. Mater. 2016, 112, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifei, W.; Ye, L.; Hua, C.; Guangsheng, H.; Xinwei, F.; Xiaoqing, C. Effect of residual tensile stress and crystallographic structure on corrosion behavior of AZ31 Mg alloy rolled sheets. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yan, L.; Jihua, C.; Zhengyang, Z. Effects of tensile and compressive deformation on corrosion behaviour of a Mg–Zn alloy. Corros. Sci. 2015, 90, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, G.; Eliezera, D.; Wagner, L. The relation between severe plastic deformation microstructure and corrosion behaviorof AZ31 magnesium alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 468, 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Parastoo, M.K.; Mehdi, M.; Ahmad, B.; Mehrab, L.; Seyed, M.F.; Soraya, B.Z. Combination of severe plastic deformation and heat treatment for enhancing the corrosion resistance of a new Magnesium alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 927, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jianwei, LI.; Youmin, QIU.; Junjie, Y.; Yinying, S.; Yanliang, Y.; Xun, Z.; Lianxi, C.; Fengliang, Y.; Jiangzhou, S.; Tiejun, Z.; Xin, T.; Bin, G. Effect of grain refinement induced by wire and arc additive manufacture (WAAM) on the corrosion behaviors of AZ31 magnesium alloy in NaCl solution. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2023, 11, 117–229.

- Zeinab, S.; Hamed, M.; Rouhollah, M.A.; Reza, M. Effect of grain size on the mechanical properties and bio-corrosion resistance of pure magnesium. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 3100–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Chun, C.; Lingyu, L.; Jialin, N.; Shaokang, G.; Hua, H.; Hui, Z.; Guangyin, Y. Microstructure design for biodegradable magnesium alloys based on biocorrosion behavior by macroscopic and quasi-in-situ EBSD observations. Corros. Sci. 2023, 221, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, B.; Mehrab, L.; Milad, T.; Kim, W.J. Corrosion behavior of severely plastically deformed Mg and Mg alloys. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2022, 10, 2607–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilsoo, H.; Ji, Y.L.; Y., C.K.; Ji, H.P.; Dong, I.K.; Hyung, S.H.; Seok, J.Y.; Hyun, K.S. Preferred crystallographic pitting corrosion of pure magnesium in Hanks’ solution. Corros. Sci. 2012, 63, 316–322. [CrossRef]

- Liying, H.; Kuaishe, W.; Wen, W.; Jie, Y.; Ke, Q.; Tao, Y.; Pai, P.; Tianqi, Li. Effects of grain size and texture on stress corrosion cracking of friction stir processed AZ80 magnesium alloy. Eng Fail Anal. 2018, 92, 392–404. [Google Scholar]

- Orlov, D.; Ralston, K.D.; Birbilis, N.; Estrin, Y. Enhanced corrosion resistance of Mg alloy ZK60 after processing by integrated extrusion and equal channel angular pressing. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 6176–6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Lopez, M.; María, D.P.; del Valle, J.A.; Fernandez-Lorenzo, M.; Garcia-Alonso, M.C.; Ruano, O.A.; Escudero, M.L. Corrosion behaviour of AZ31 magnesium alloy with different grain sizes in simulated biological fluids. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1763–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yin, S.M.; Li, S.X.; Zhang, Z.F. Crack initiation mechanism of extruded AZ31 magnesium alloy in the very high cycle fatigue regime. Mater. Sci. Eng: A 2008, 491, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.B.; Chu, J.H.; Sun, W.T.; Jiang, Z.H.; Zou, D.N.; Wang, K.S.; Kamado, S.; Zheng, M.Y. Development of high-performance Mg–Zn–Ca–Mn alloy via an extrusion process at relatively low temperature. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 825, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.P.; Zhen, Z.; Huan, H.C.; Qian, H.Z.; Liang, Y.C.; Ting, T.G.; Sheng, L. Tension-compression asymmetry and Bauschinger-like effect of AZ31 magnesium alloy bars processed by ambient extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng: A 2023, 862, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Amro, H.A.; Junaidi, S.; Zainuddin, S. Deformation behavior of single-crystal magnesium during Nano-ECAP simulation. Heliyon 2022, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ehsan, G.; Reza, A.; Terence, G.L. Effect of crystallographic texture and twinning on the corrosion behavior of Mg alloys: A review. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2022, 10, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, N.A.; Wei, Z. Effect of grain size and twins on corrosion behaviour of AZ31B magnesium alloy. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbaghian, M.; Mahmudi, R.; Shin, K.S. Effect of texture and twinning on mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of an extruded biodegradable Mg–4Zn alloy. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2019, 7, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guodong, Z.; Qiuming, P.; Yanan, W.; Baozhong, L. The effect of extension twinning on the electrochemical corrosion properties of Mg–Y alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 618, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, X.; Tao, Z.; Jie, Y.; Yi, Y.; Xinghua, G. Effect of Twin-Induced Texture Evolution on Corrosion Resistance of Extruded ZK60 Magnesium Alloy in Simulated Body Fluid. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 5710–5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md. Shahrier Hasan.; Rachell, L.; Wenwu, X. Deformation nanomechanics and dislocation quantification at the atomic scale in nanocrystalline magnesium. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2020, 8, 1296–1303. [CrossRef]

- Zhuoran, Z.; Mengran, Z.; Peter, L.; Frédéric, M.; Qinfen, G.; Mohsen, E.; Yuanming, Y.; Yao, Q.; Shiwei, X.; Hidetoshi, F.; Chris, D.; Jian, F.N.; Nick, B. Deformation modes during room temperature tension of fine-grained pure magnesium. Acta Mater. 2021, 206, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidetoshi, S.; Masato, W.; Alok, S. Enhancing ambient temperature grain boundary plasticity by grain refinement in bulk magnesium. Mater. Sci. Eng: A 2022, 848, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, P.S.; Alexis, M.P.; Jerawala, H.; George, D. Magnesium and its alloys as orthopedic biomaterials: A review. BMs 2006, 27, 1728–1734. [Google Scholar]

- Haixuan, W.; Wenzhen, C.; Wenke, W.; Zhichao, F.; Wencong, Z. Reducing the cyclic tension-compression asymmetry and cyclic hardening of ZK61 magnesium alloy via the compression-extrusion process. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2003, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, S.M.; Yang, H.J.; Li, S.X.; Wu, S.D.; Yang, F. Cyclic deformation behavior of as-extruded Mg–3%Al–1%Zn. Scr. Mater. 2008, 58, 751–754. [Google Scholar]

- Saeede, G.; Brandon, A.M.; Marko, K. Effects of environmental temperature and sample pre-straining on high cycle fatigue strength of WE43-T5 magnesium alloy. Int J Fatigue. 2020, 141, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, H.P. Effect of initial twins on the stress-controlled fatigue behavior of rolled magnesium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng: A 2017, 680, 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner, S.; Uggowitzer, P.J. Mechanical anisotropy of extruded Mg–6% Al–1% Zn alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng: A 2004, 379, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.N.; Huang, J.C. The role of twinning and untwinning in yielding behavior in hot-extruded Mg–Al–Zn alloy. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoqian, G.; Yao, C.; Yunchang, X.; Wei, W.; Chao, M.; Ke, A.; Peter, K.L.; Peidong, W.; Qing, L. Crystal plasticity modeling of low-cycle fatigue behavior of an Mg-3Al-1Zn alloy based on a model, including twinning and detwinning mechanisms. J Mech Phys Solids. 2022, 168, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Xiyan, Z.; Qi, S.; Jiangping, Y.; Guangjie, H.; Qing, L. Pyramidal slips in high cycle fatigue deformation of a rolled Mg-3Al-1Zn magnesium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng: A 2017, 699, 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.; Ruixiao, Z.; Stefanus, H.; Takuro, K.; Kazuya, A.; Nobuhiro, T. In-situ observation of twinning and detwinning in AZ31 alloy. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2022, 10, 3418–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, S.; Jiang, Z.; Tianjiao, L.; Haoge, S.; Dongdi, Y.; Jinsong, R. Quantitative analysis of the deformation modes and cracking modes during low-cycle fatigue of a rolled AZ31B magnesium alloy: The influence of texture. Mater. Sci. Eng: A 2022, 844, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, X.; Yi, Y.; Xiaxia, H. Fatigue behavior of modified ZK60 magnesium alloy after pre-corrosion under stress-controlled loading. Eng Fract Mech. 2022, 260, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, X.; Zengyuan, Y.; Tao, Z.; Yanyao, J. Effect of texture evolution on corrosion resistance of AZ80 magnesium alloy subjected to applied force in simulated body fluid. Mater. Res. Express. 2020, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, L.; Fang, W.; Siyan, R.; Guiqiu, X.; Gang, L.; Rulan, G.; Xiangguo, Z. Plastic deformation response during crack propagation in Mg bicrystals with twin boundaries. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 3337–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Curtin, W.A. Brittle and ductile crack-tip behavior in magnesium. Acta Mater. 2015, 88, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Annealing Time [h] | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Temperature [K] | none | 473 | 513 | 573 | 613 | 673 |

| Solution | 0.9 (mass%) NaCl |

| Corrosion time [h] | 24 |

| Corrosive environment | immersion |

| Stress ratio | -1 |

| Environment | atmosphere |

| Frequency [Hz] | 20 |

| Number of cycles [N] | 2.0×107 |

| Tensile stress [MPa] | 10, 20, 30, 40 |

| Compressive stress [MPa] | 10, 20, 30, 40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).