Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Fucoidan and Hyaluronic Acid Modified ZE21B Alloy

2.3. Characterization of Fucoidan and Hyaluronic Acid Modified ZE21B Alloy

2.4. Hemolysis Rate of Fucoidan and Hyaluronic Acid Modified ZE21B Alloy

2.5. Fibrinogen Adsorption of Fucoidan and Hyaluronic Acid Modified ZE21B Alloy

2.6. Growth Behavior of ECs and SMCs on ZE21B Alloy Modified with Fucoidan and Hyaluronic Acid

2.7. Coculture of ECs and SMCs on ZE21B Alloy Modified with Fucoidan and Hyaluronic Acid

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

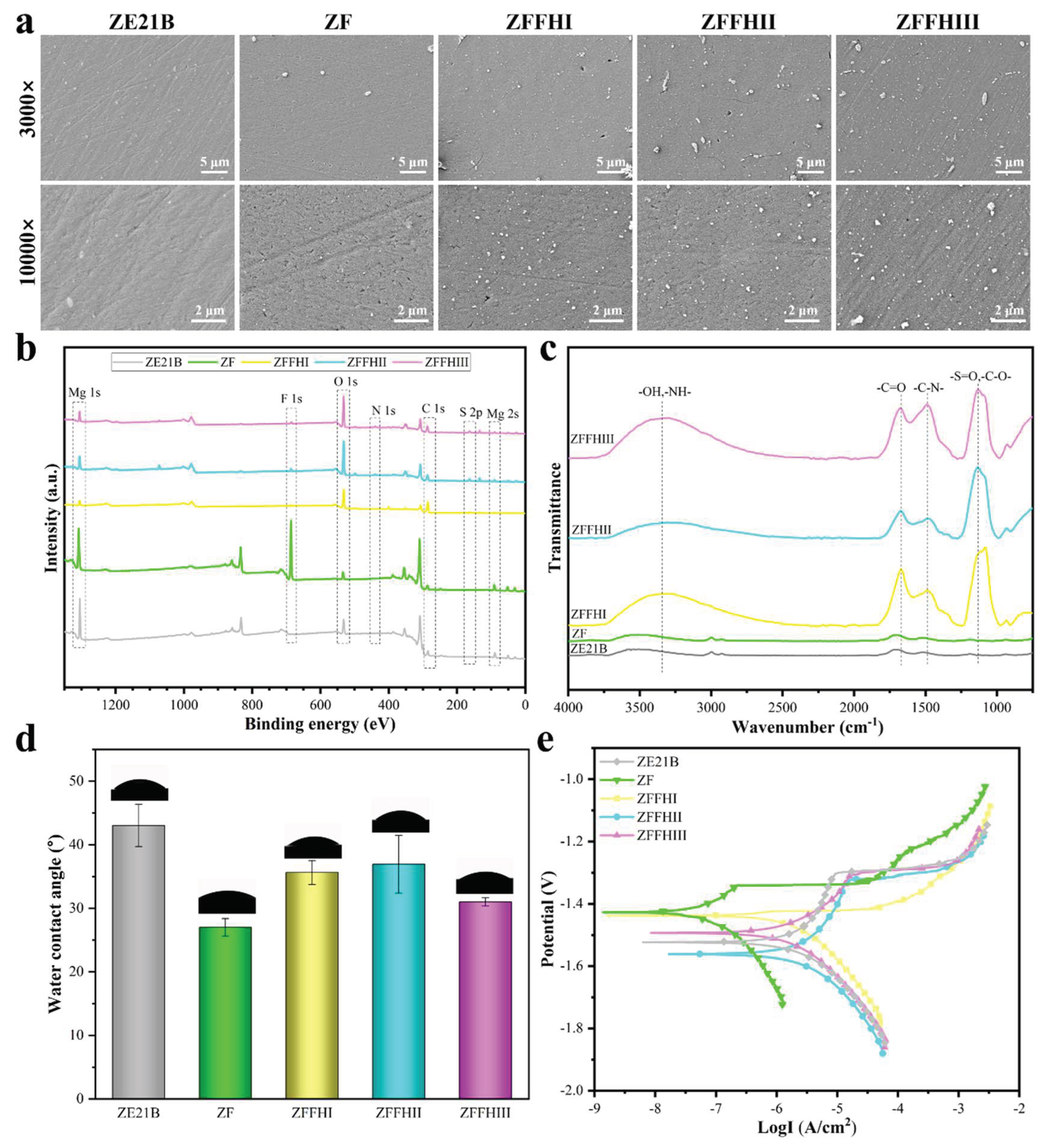

3.1. Characterization of Fucoidan and Hyaluronic Acid Modified ZE21B Alloy

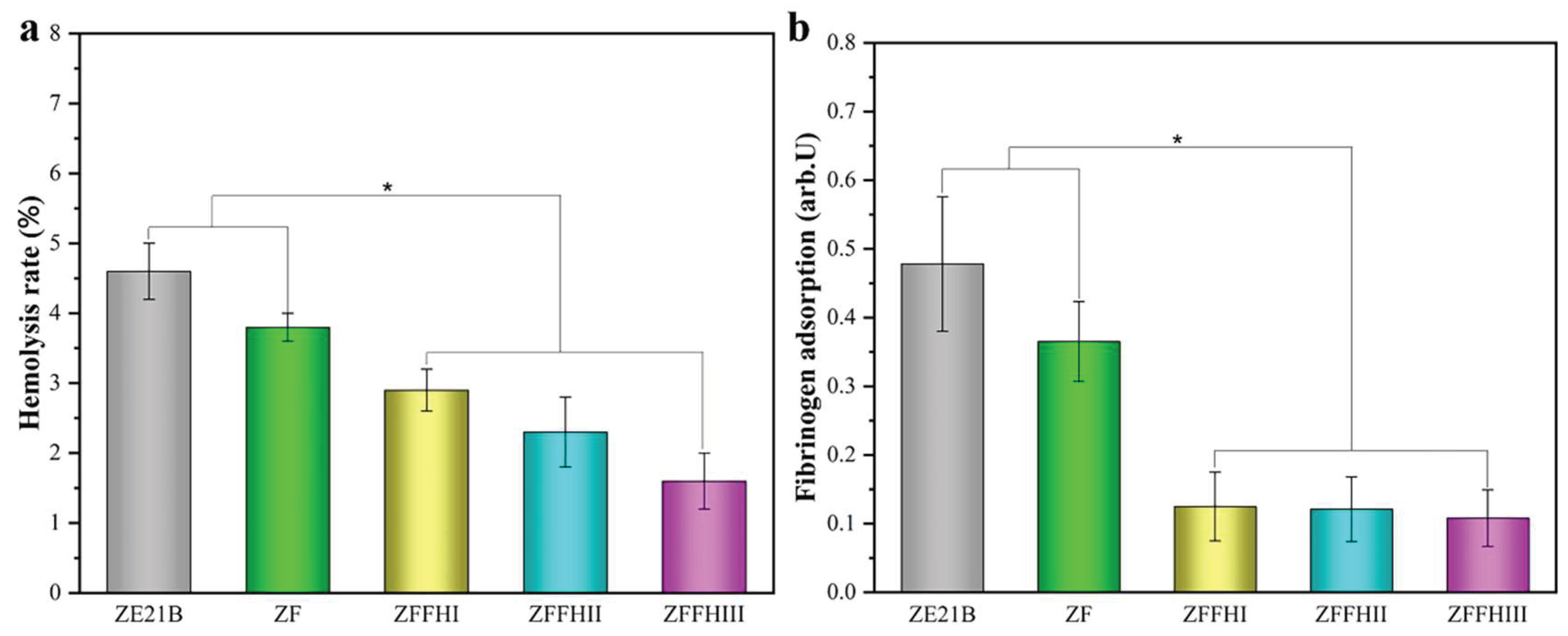

3.2. In Vitro Hemocompatibility of Fucoidan and Hyaluronic Acid Modified ZE21B Alloy

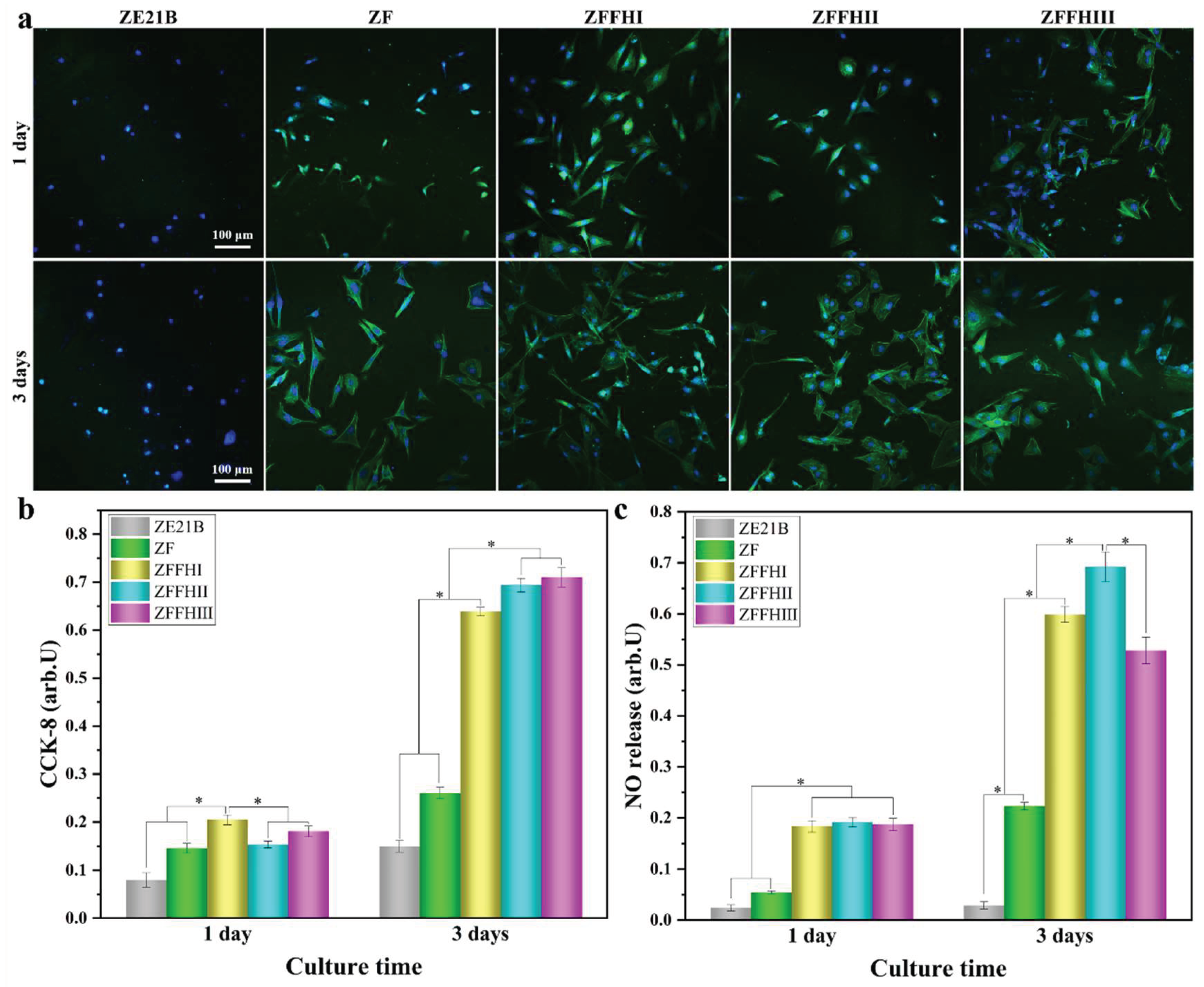

3.3. Adhesion, Proliferation, and NO Release of ECs on Modified ZE21B Alloy

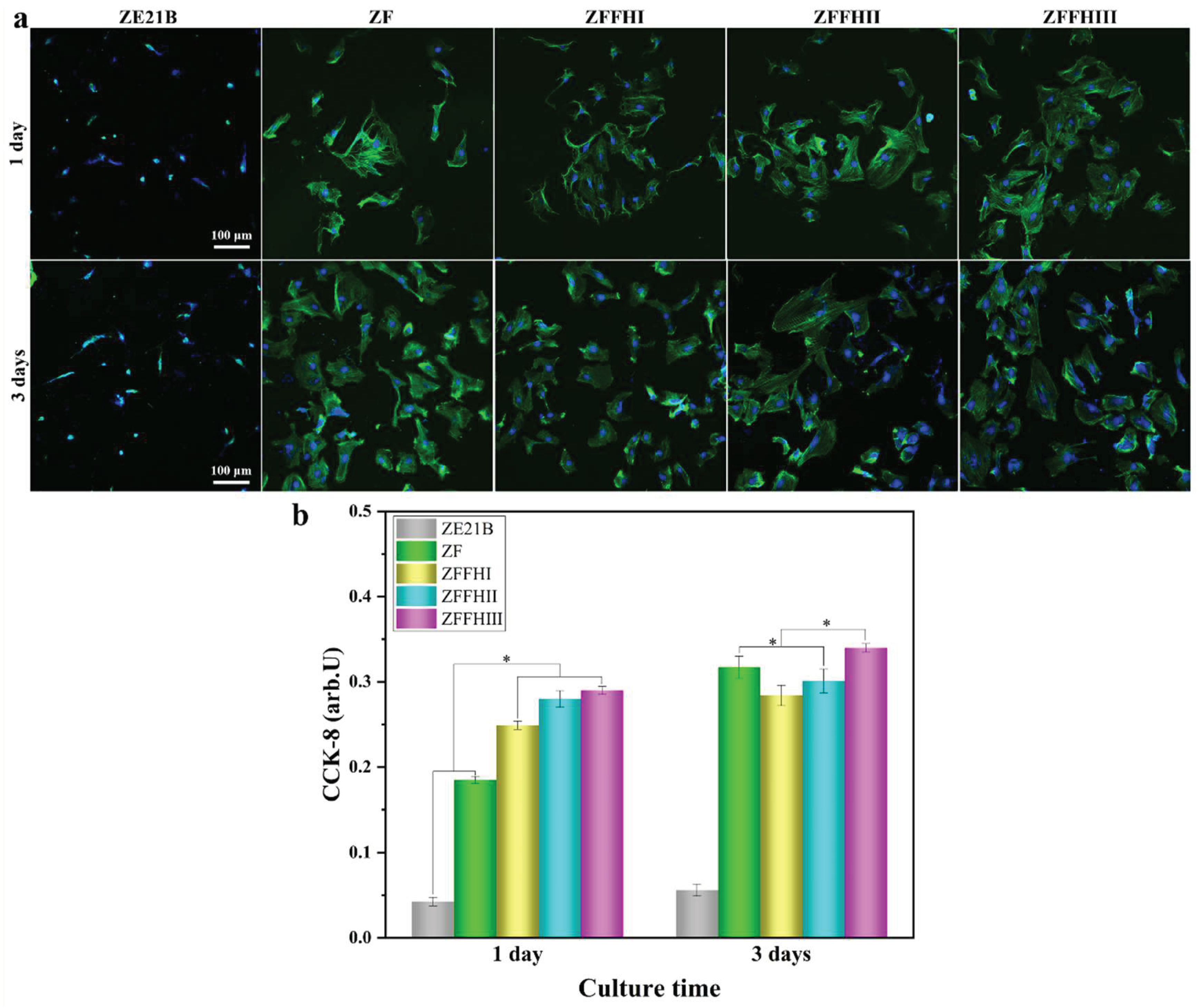

3.4. Adhesion and Proliferation of SMCs on Modified ZE21B Alloy

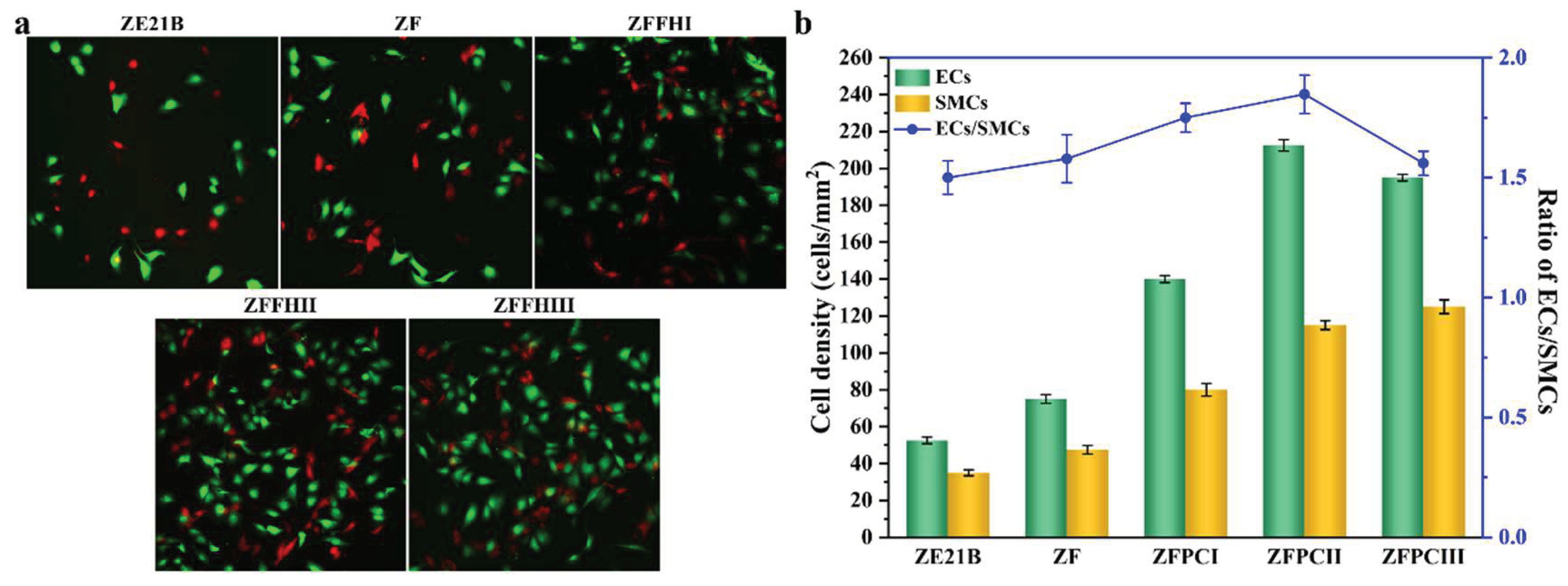

3.5. Competitive Growth of ECs and SMCs on Modified ZE21B Alloy

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, S.Q.; Ludman, P.F. Percutaneous coronary intervention. Medicine 2022, 50, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.H.; Im, D.H.; Park, S.J.; Jung, Y.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.H. Current status and future direction of metallic and polymeric materials for advanced vascular stents. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 126, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Mei, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Du, P.H.; Bai, L.C.; Yan, C.; Li, J.A.; Wang, J.; Zhu, S.J. Mg alloy cardio-/cerebrovascular scaffolds: Developments and prospects. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 4011–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.C.; Wang, Y.H.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Li, J.A.; Zhu, S.J.; Wang, L.G.; Guan, S.K. Preparation of functional coating on magnesium alloy with hydrophilic polymers and bioactive peptides for improved corrosion resistance and biocompatibility. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 10, 1957–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Yang, Y.X.; Li, J.A.; Zeng, R.C.; Guan, S.K. Advances in coatings on magnesium alloys for cardiovascular stents–a review. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 4729–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Chen, L.; Hou, R.Q.; Bai, L.C.; Guan, S.K. Rapamycin-loaded nanocoating to specially modulate smooth muscle cells on ZE21B alloy for vascular stent application. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 615, 156410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.C.; Wang, Y.H.; Xie, J.; Zhao, Y.; Guan, S.K. Fucoidan-based coating on magnesium alloy improves the hemocompatibility and pro-endothelialization potential for vascular stent application. Mater. Des. 2023, 233, 112235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imandoust, A.; Barrett, C.D.; Al-Samman, T.; Inal, K.A.; El Kadiri, H. A review on the effect of rare-earth elements on texture evolution during processing of magnesium alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Tan, Y.; Lu, Q.; Yi, H.; Cheng, C.; Wu, L.; Saji, V.S.; Pan, F. Recent advances in protective coatings and surface modifications for corrosion protection of Mg alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 3238–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Xie, Y.D.; Bai, L.C.; Guan, S.K. Fucoidan/collagen composite coating on magnesium alloy for better corrosion resistance and pro-endothelialization potential. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 255, 128044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Wu, L.; Wang, J.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, D.; Serdechnova, M.; Shulha, T.; Blawert, C.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Pan, F. Micro-arc oxidation of magnesium alloys: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 118, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Bai, L.C.; Guan, S.K. Co-immobilization of natural marine polysaccharides and bioactive peptides on ZE21B magnesium alloy to enhance hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 272, 132747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Bai, L.; Chen, L.; Guan, S. Chondroitin sulfate and Cys-Ala-Gly peptides coated ZE21B magnesium alloy for enhanced corrosion resistance and vascular compatibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 143895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.D. , Chen A.Y., Gan B.; Jiang H.; Gu L.J. Corrosion protection investigations of carbon dots and polydopamine composite coating on magnesium alloy. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 10, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhen, Z.; Liu, J.; Xi, T.; Zheng, Y.; Guan, S.; Zheng, Y.; Cheng, Y. Multifunctional MgF2/polydopamine coating on Mg alloy for vascular stent application. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2015, 31, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Du, H.; Huang, H.; Wei, Y.; Hou, L.; Wang, Q.; Wei, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; He, H.W. Deposition of modifiable MAO-PDA coatings on magnesium alloy based on photocatalytic effect. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 669, 160522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, J.; Murugan, S.S.; Seong, G.H. Fucoidan-based nanoparticles: Preparations and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 217, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zaw, A.M.; Anderson, D.E.J.; Hinds, M.T.; Yim, E.Y.K. Fucoidan functionalization on poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogels for improved endothelialization and hemocompatibility. Biomaterials 2020, 249, 120011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinval, N.; Morenc, M.; Labour, M.N.; Samotus, A.; Mzyk, A.; Ollivier, V.; Maire, M.; Jesse, K.; Bassand, K.; Niemiec-Cyganek, A.; Haddad, O.; Jacob, M.P.; Chaubet, F.; Charnaux, N.; Wilczek, P.; Hlawaty, H. Fucoidan/VEGF-based surface modification of decellularized pulmonary heart valve improves the antithrombotic and re-endothelialization potential of bioprostheses. Biomaterials 2018, 172, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simińska-Stanny, J.; Podstawczyk, D.; Delporte, C.; Nie, L.; Shavandi, A. Hyaluronic acid role in biomaterials prevascularization. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2024, 13, 2402045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, N.; Huang, K.; Wu, X.; Tan, Y.; Hu, Q.; Luo, R.; Wang, Y. Multifunctional hyaluronic acid-based coating to direct vascular cell fate for enhanced vascular tissue healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 288, 138741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.; Liu, L.; Li, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, H.; Weng, H.; Gu, G.; Xiao, M.; Chen, Z. Construction of enzyme-laden vascular scaffolds based on hyaluronic acid oligosaccharides-modified collagen nanofibers for antithrombosis and in-situ endothelialization of tissue-engineered blood vessels. Acta Biomater. 2022, 153, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Cai, K.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, J.; Ma, N.; Gao, B.; Yu, S. VEGF loading heparinized hyaluronic acid macroporous hydrogels for enhanced 3D endothelial cell migration and vascularization. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 167, 214094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.A.; Shi, J.; Guo, J.Y.; Wang, S.F. Recent strategies for improving hemocompatibility and endothelialization of cardiovascular devices and inhibition of intimal hyperplasia. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 3781–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, H.; Arzaghi, H.; Bayandori, M.; Shiralizadeh, A.; Pazoki-Toroudi, H.; Shafiee, A.; Moradi, L. Controlling cell behavior through the design of biomaterial surfaces: a focus on surface modification techniques. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1900572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.T.; Mendes, A.X.; Duchi, S.; Duc, D.; Aguilar, L.C.; Quigley, A.F.; Kapsa, B.M.I.; Nisbet, D.R.; Stoddart, P.R.; Silva, S.M.; Moulton, S.E. Wired for success: Probing the effect of tissue-engineered neural interface substrates on cell viability. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 3775–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.R.; Garren, M.R.S.; Wilson, S.N.; Handa, H.; Batchinsky, A.I. Development and in vitro whole blood hemocompatibility screening of endothelium-mimetic multifunctional coatings. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 2212–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, S.; Abdelrasoul, A. Impact of membrane modification and surface immobilization techniques on the hemocompatibility of hemodialysis membranes: A critical review. Membranes 2022, 12, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, C.H.; Nguyen, N.T.; Ta, H.T. Unravelling surface modification strategies for preventing medical device-induced thrombosis. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2024, 13, 2301039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchinka, J.; Willems, C.; Telyshev, D.V.; Groth, T. Control of blood coagulation by hemocompatible material surfaces—a review. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Bai, S.; Zhu, K.; Yuan, X. Electrospun membranes of diselenide-containing poly (ester urethane) urea for in situ catalytic generation of nitric oxide. J. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 35, 1157–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Liu, T.; Zeng, P.; Xie, Y.; Li, L.; Tan, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Bian, Q.; Xiao, H.; Liang, S.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, L. Enhancing vascular implants with heparin-polylysine-copper nanozyme coating for synergistic anticoagulation and antirestenotic activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 309, 143048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.K.; Heo, S.H.; Yoon, J.K. In-stent re-endothelialization strategies: Cells, extracellular matrix, and extracellular vesicles. Tissue Eng. Part B 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Xun, M.; Chen, Y. Adaptation of vascular smooth muscle cell to degradable metal stent implantation. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 4086–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Qi, P.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Tan, X.; Xiao, Y.; Maitz, M.F.; Huang, N.; Yang, Z. Biomimetic engineering endothelium-like coating on cardiovascular stent through heparin and nitric oxide-generating compound synergistic modification strategy. Biomaterials, 2019, 207, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. , Feng Y. Surface engineering of cardiovascular devices for improved hemocompatibility and rapid endothelialization. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2020, 9, 2000920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).