1. Introduction

The pervasiveness of digital media in the lives of young children has sparked growing concern about problematic media use (PMU) – excessive or uncontrolled exposure that can negatively impact their developing minds and bodies [

1]. Preschoolers, in a period of rapid brain development, are particularly vulnerable to the potentially negative effects of PMU, with excessive screen time linked to impairments in crucial cognitive skills, including executive functions [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Among these, working memory—a cornerstone of learning, reasoning, and problem-solving [

5]—is of vital importance for academic and social success. Despite the recognized importance of working memory and the growing prevalence of PMU, research exploring the neural mechanisms underlying this relationship in preschoolers remains scarce, with only limited investigation using neuroimaging techniques, such as functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) [

9]. This study addressed this critical gap by employing fNIRS to examine the neural correlates of PMU and its impact on working memory in young children, providing critical insights for developmental theory, educational practices, and effective parenting strategies.

1.1. Problematic Media Use in Early Childhood: Theoretical Perspectives

Problematic media use (PMU) in early childhood can be understood through the lens of several interconnected theoretical frameworks. Cognitive developmental theory [

10,

11] emphasizes children's cognitive immaturity and susceptibility to media influence, which can impact their ability to distinguish between fantasy and reality and potentially hinder opportunities for crucial social interaction. Social cognitive theory [

12] emphasizes observational learning and modeling, suggesting that media can shape children's behaviors and attitudes. Self-determination theory [

13] posits that excessive media use may hinder children's innate psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The displacement hypothesis highlights how media consumption can supplant developmentally vital activities, such as play and social interaction [

14]. Uses and gratifications theory [

15] considers children's active choices in media consumption as a means to fulfill specific needs, while Bronfenbrenner's [

16] ecological systems theory emphasizes the interplay of various environmental systems, including family and cultural norms, in shaping media use patterns. These frameworks collectively provide a comprehensive perspective on the complex interplay of developmental, social, and environmental factors that contribute to PMU in early childhood.

In particular, the Interactional Theory of Childhood Problematic Media Use (IT-CPU) provides a valuable framework for understanding this complex phenomenon [

1]. This theory posits that PMU emerges and persists due to the interaction of distal, proximal, and maintaining factors. Distal factors, representing broader contextual influences, lay the groundwork for potential PMU. Socioeconomic status (SES), parental education, and the digital environment within the home all contribute to children’s early media habits. Research consistently indicates that children from lower SES backgrounds [

17,

18]and those experiencing higher levels of household chaos [

19,

20] exhibit greater screen time, thereby elevating their risk for poor mental health outcomes. Parental modeling also plays a significant role; children of parents with problematic screen use are more likely to develop similar patterns [

21], suggesting a learned behavior component.

Proximal factors, operating at a more immediate level, directly influence children’s media use. Children’s temperament, particularly traits like emotional dysregulation and oppositional behavior, can contribute to PMU. Caregivers often utilize digital devices as a calming or behavioral management tool in challenging situations, such as during public outings or when children display negative affect [

6,

22]. This reinforces the association between media use and emotional regulation, potentially leading to increased reliance on screens. Parental media parenting practices are also crucial. A lack of clear media-use guidelines and structure, coupled with parental media use in the presence of children, can unconsciously encourage excessive screen time [

23]. These proximal factors, interacting with distal influences, create a context where PMU can take root.

Maintaining factors perpetuate established patterns of PMU. While not extensively explored in the literature regarding young children, these factors could include the reinforcing nature of digital media content, habit formation, and the potential for withdrawal symptoms when media access is restricted. Further research is needed to fully understand the maintaining factors contributing to PMU in early childhood.

1.2. PMU and Working Memory: A Complex Relationship

The relationship between media use and working memory, particularly in young children, is complex and marked by inconsistent findings. While some research suggests potential cognitive benefits associated with specific types of media engagement (e.g., educational apps, interactive games)[

24,

25], these studies often focus on older children and adolescents, limiting their generalizability to preschoolers. Moreover, a growing body of evidence highlights the detrimental effects of excessive or unregulated screen time, especially smartphone overuse, on working memory and broader cognitive abilities. For instance, studies have linked frequent mobile phone use to decreased accuracy and slower performance on working memory tasks in school-aged children [

26,

27]. However, other research has found no significant association between mobile phone use and working memory in this age group [

28]. These inconsistencies may stem from methodological variations across studies, including differences in sample characteristics, measurement tools, and definitions of PMU. Crucially, few studies have directly examined this relationship in preschoolers, a population particularly vulnerable to the impact of early media exposure due to the rapid development of prefrontal regions crucial for working memory [

29].

This study addresses this critical gap by using a combined behavioral and neuroimaging (fNIRS) approach to investigate the association between PMU and working memory performance in preschoolers, aiming to provide a more nuanced understanding of the cognitive consequences of early media exposure in this vulnerable population. In particular, this study seeks to examine the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Preschoolers with higher levels of PMU will exhibit significantly lower behavioral performance on working memory tasks, as measured by accuracy and response time.

Hypothesis 2: Preschoolers with higher levels of PMU will exhibit reduced activation in the prefrontal cortex during working memory tasks, as measured by fNIRS oxygenated hemoglobin changes.

Hypothesis 3: The relationship between PMU and working memory performance will be moderated by individual factors such as gender, exploring potential differential vulnerabilities to the effects of excessive media use.

This study, by testing these hypotheses, will address a critical gap in the existing literature by providing the first neuroimaging evidence of the relationship between PMU and working memory in preschool children, paving the way for future research in this important area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

All participants were initially recruited from two private kindergartens in Jinan, Shandong Province, China. A total of 456 parents of children aged 3 to 7 years (238 boys, 218 girls,

Mage = 5.57 years,

SDage = 0.74) completed the Problematic Media Use Measure-Short Form (PMUM-SF) questionnaire. Based on the scores of PMUN-SF, the high- and low-problematic media use groups were recruited using the extreme grouping method, resulting in a total of 79 children. All participants were reported to be right-handed, with normal intelligence and no history of neurological disease, loss of consciousness, sensory impairment, autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or learning disabilities. After the experiment was formally conducted, a total of three participants were lost. Another 14 participants were excluded due to poor data quality or missing data, resulting in a final sample of 62 children, with 32 in the low group (

Mage = 4.53 years,

SDage = 0.67) and 30 in the high group (

Mage = 4.67 years,

SDage = 0.66). A priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 [

30], assuming a medium effect size (ƒ = 0.25), an alpha level of .05, and a power of .85, indicated a minimum sample size of 44 participants. So, the sample size is adequate for this study. The Research Ethics Committee of Shanghai Normal University approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents, kindergarten principals, and educational directors (class teachers) prior to participation. Participants were informed of the study’s voluntary nature and their right to withdraw at any time. All participants received a toy as a reward for participating in the study.

2.2. Measures

Combined Raven’s Test (CRT): The CRT was administered to all participants to assess individual and group differences in intelligence quotient (IQ). Li et al. [

31] adapted the test and validated it in a sample from Shanghai (a city in China). The findings demonstrated that the CRT aligns well with the cognitive development levels of Chinese children, exhibiting high reliability and moderate validity. Given the potential upward trend in children’s IQ scores over the past few decades, this study utilized raw scores for statistical analyses [

32].

Problematic Media Use Measure-Short Form (PMUM-SF): The PMUM-SF was developed to assess problematic media use (PMU) in young children. The Chinese version of the PMUM has been validated for use in Chinese preschoolers [

33]. This PMUM-SF consisted of 9 items (e.g., “It is hard for my child to stop using screen media”), which required parents to rate their children’s frequency of daily media use on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “never” to “always” (1 =

Never, 5 =

Always). The final score of PMU was calculated by summing the scores of each item. The reliability of this scale, as measured by Cronbach’s α, was found to be 0.93.

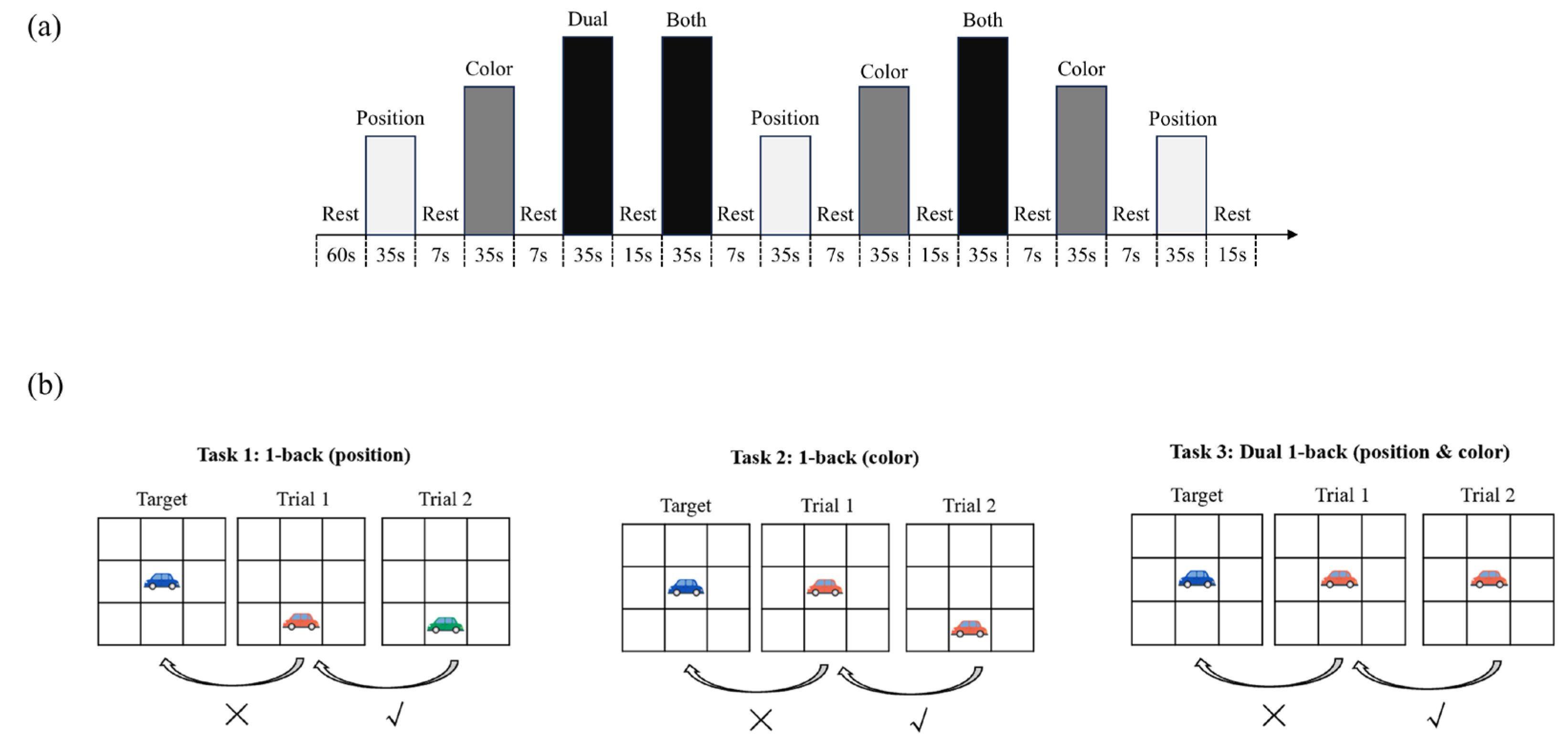

Dual 1-back Task: Based on the dual n-back paradigm [

34] and the visuospatial n-back Task adapted for children [

35], this study employed a modified dual 1-back task to assess the visuospatial working memory of preschool children aged 4–6. To enhance engagement and child-friendliness, we redesigned the stimuli using cartoon vehicles with bright colors, replacing the standard geometric shapes typically used in previous versions. The Task required participants to track both the position and color of the stimulus (a cartoon car) on a 3×3 grid displayed at the center of a gray computer screen. The working memory task consisted of three experimental conditions designed to tap into different cognitive demands: (1) Position-only 1-back, in which children were asked to judge whether the car appeared in the same spatial location as in the previous trial; (2) Color-only 1-back, where they judged whether the car’s primary color matched that of the preceding trial; and (3) Dual 1-back, where both spatial position and color had to match simultaneously. Each condition was repeated in three blocks, presented in a pseudo-randomized order, resulting in a total of nine blocks and 81 trials across the task. (see

Figure 1a). Within each block, nine stimulus trials were presented, with each trial containing one matching stimulus and six non-matching ones (i.e., match:non-match ratio = 3:6+1). Before the formal experiment began, a guided practice session was conducted. Children received auditory feedback during the practice: a cheerful “Oh-ho!” sound for correct responses and a neutral “beep” for errors or missing responses. Once the child achieved an accuracy rate above 80%, the formal experiment began without auditory feedback.

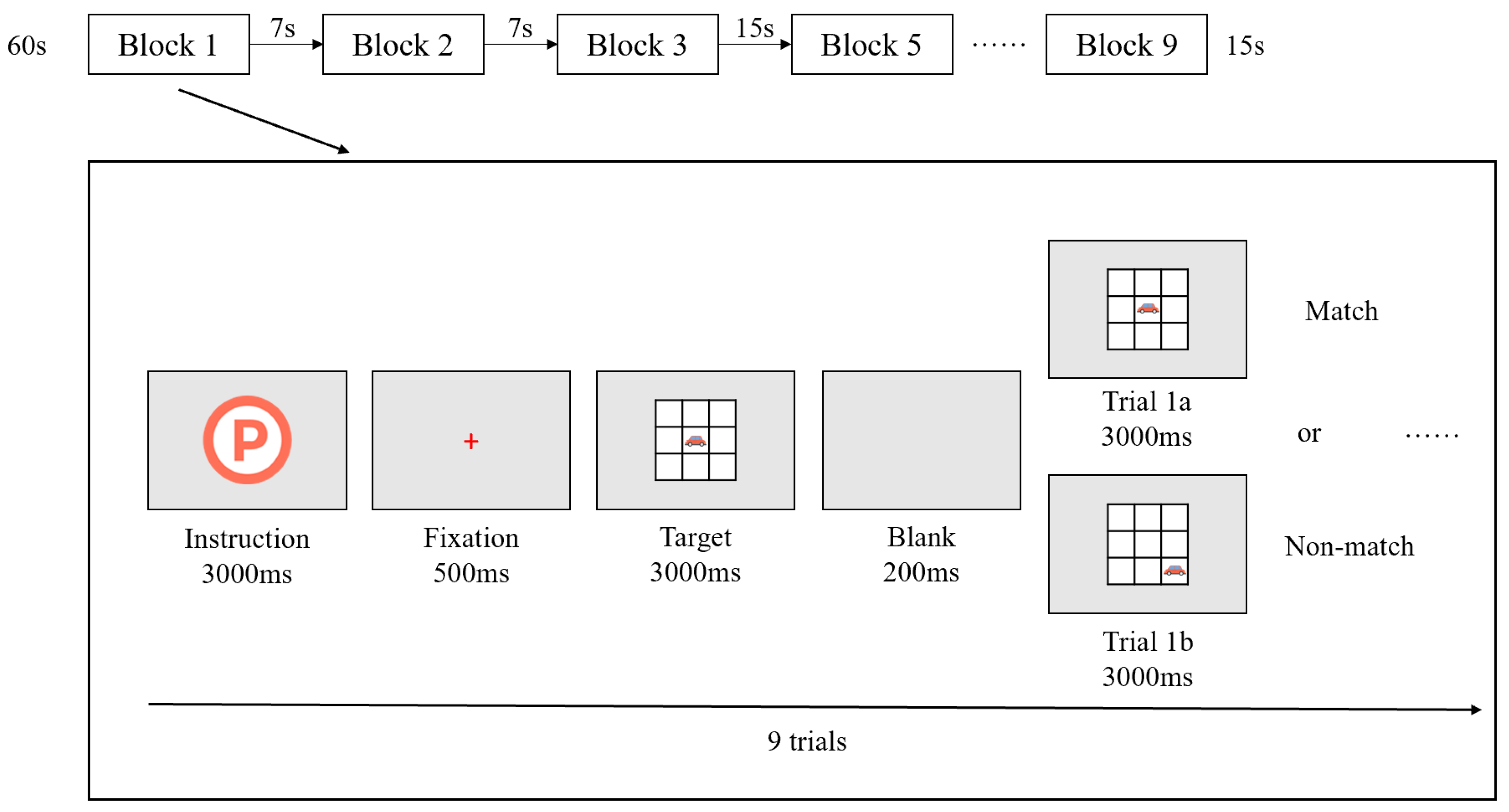

The Task was programmed and presented using

E-Prime 3.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA), and all stimuli were displayed on a 16-inch laptop screen with a resolution of 1024 × 768 pixels. Each block began with a 300-ms task instruction screen indicating the type of upcoming condition, followed by a red fixation cross displayed for 500 ms. Then, the target stimulus (a cartoon car) appeared on the screen for 3000 ms. During each trial, participants had to respond to whether the current stimulus matched the one presented in the previous trial based on the task condition. As shown in

Figure 1b, they need to respond by pressing either the “✓” key (match) or the “×” key (non-match). If no response was made within 5000 ms, the stimulus disappeared automatically. A 200 ms blank screen followed each trial before the next stimulus appeared. The entire Task lasted approximately 7–8 minutes (

Figure 2).

2.3. fNIRS Data Recording and Processing

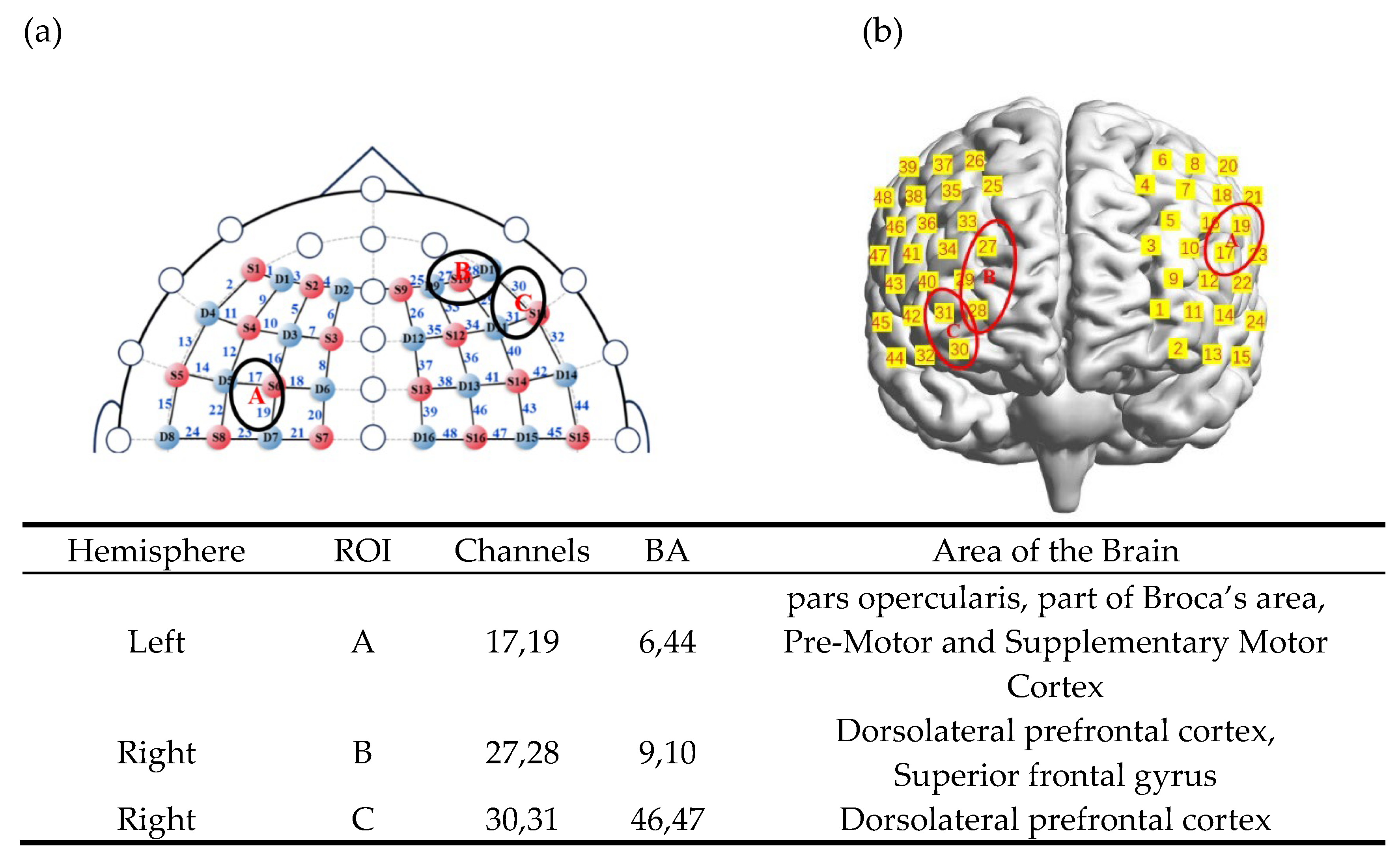

A portable fNIRS device (NirSport2, NIRx Medizintechnik GmbH, Germany) was used to collect brain imaging data from children. The system employed wavelengths of 760 and 850 nm, with a sampling frequency of 5.1 Hz, and operated using the Aurora fNIRS 2021.9 acquisition software. According to the international 10-10 transcranial localization system, 16 sources and 16 detectors were arranged to mainly cover bilateral prefrontal regions, including the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), middle frontal gyrus (MFG), and superior frontal gyrus (SFG), with a standard inter-optode distance of 3 cm. To minimize external environmental interference on children’s performance, the fNIRS experiment was conducted in a well-insulated meeting room within the kindergarten.

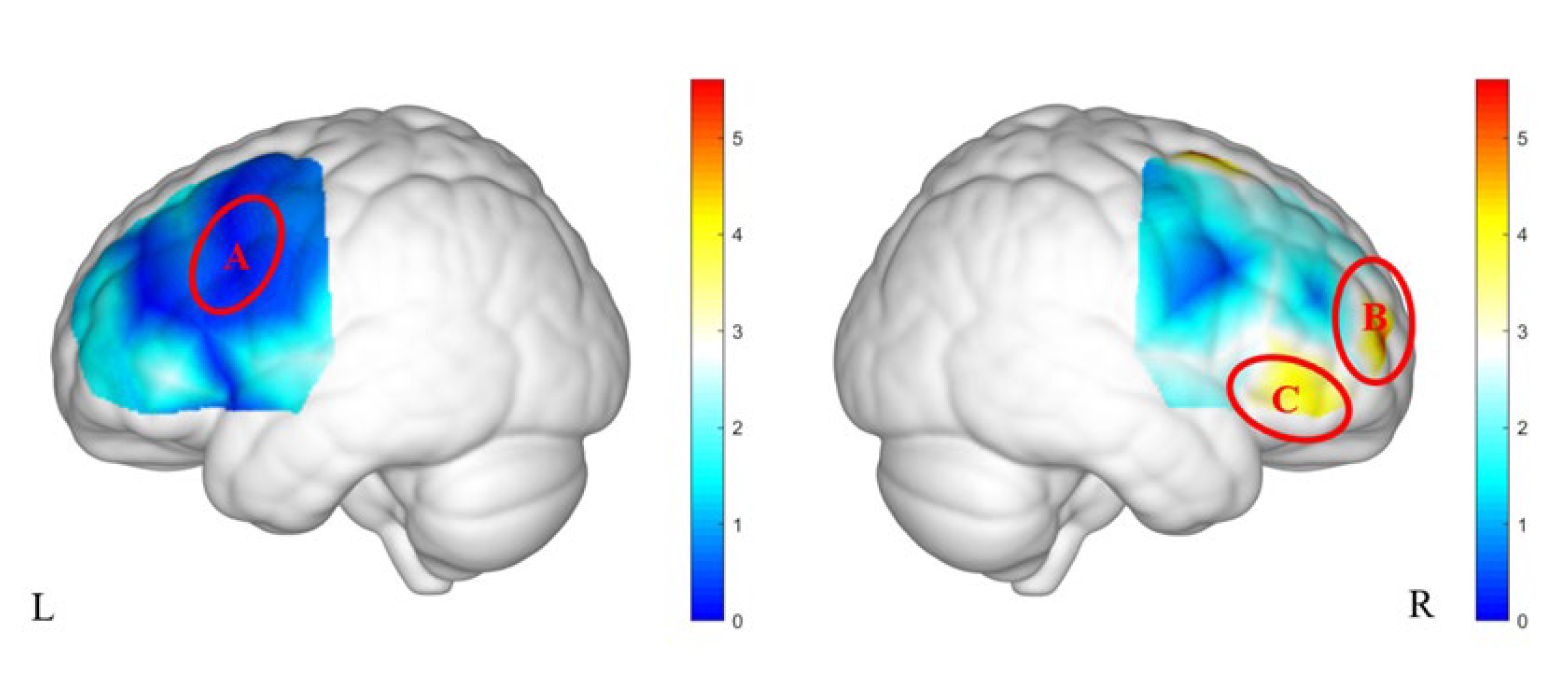

After data collection, a probabilistic registration method was applied in MATLAB to map the channel positions to MNI space. Corresponding Brodmann areas (BA) are listed in

Table A1. As illustrated in

Figure 3a, the 48 channels were grouped into three regions of interest (ROIs): ROI-A included channels 17 and 19, corresponding to BAs 6 and 44; ROI-B included channels 27 and 28, corresponding to BAs 9 and 10; and ROI-C included channels 30 and 31, corresponding to BAs 46 and 47 (

Figure 3b).

Brain imaging data preprocessing was performed using MATLAB R2017b and R2021b, including artifact screening, motion correction, filtering, and averaging. The

Homer2 NIRS toolbox [

36] was employed to apply discrete wavelet transform for motion artifact removal, followed by bandpass filtering (0.01–0.2 Hz) to reduce low-frequency drifts and high-frequency physiological noise [

37]. Subsequently, raw optical signals were converted into hemoglobin concentration changes using the modified Beer-Lambert law [

37]. Considering that oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) is the most sensitive indicator of local cerebral blood flow changes [

38,

39], average HbO concentration changes in each channel were extracted and exported for further analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Behavioral data, including accuracy and reaction time from the working memory task, were first exported from E-Prime 3.0 and merged using E-Merge 3. After removing invalid trials, the data were converted into Excel files for further analysis. A 2 (Group: high problematic media use vs. low problematic media use) × 2 (Gender: boys vs. girls) × 3 (Stimulus condition: position, color, dual) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to examine differences in behavioral performance among preschool children under different conditions. Multiple comparisons were corrected using the false discovery rate (FDR) method to control for Type I errors. Statistical analyses of both behavioral data and fNIRS-measured brain activation were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0.

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Results

To examine whether the two groups of participants were matched on background variables, a multivariate analysis of variance (

MANOVA) was conducted with age, intelligence, parents’ education level, parents’ occupation, family annual income, and socioeconomic status (SES) as dependent variables, and the group as the independent variable. The

MANOVA results showed no significant overall group effect, with

Wilks’ Lambda = 0.905 and

F(7, 54) =

0.808,

p =

0.584.

Table A2 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants in the fNIRS experiment along with the results of further univariate analyses. There were no significant differences in age, intelligence, or other variables between the high and low PMU groups. Additionally, a chi-square test of gender distribution showed no significant difference between the two groups,

χ²(1) = 0.972,

p =

0.438. These results first exclude the influence of individual differences and environmental factors on the subsequent experimental outcomes.

The behavioral performance differences in working memory between preschool children with high and low levels of problematic media use (PMU) are presented in

Table 1. A 2 (group: high-PMU, low-PMU) × 2 (gender: boys, girls) × 3 (stimulus condition: spatial, color, dual) repeated measures

ANOVA was conducted on both accuracy and reaction time. For accuracy, the analysis revealed a significant main effect of stimulus condition,

F(61) = 8.268,

p = 0.001,

= 0.125, with accuracy under the position condition (

M = 0.60,

SD = 0.17) significantly lower than under the color (

M = 0.69,

SD = 0.16,

p = 0.001) and dual-task conditions (

M = 0.66,

SD = 0.15,

p = 0.011). The main effects of group (

F = 1.561,

p = 0.217,

= 0.026) and gender (

F = 2.652,

p = 0.109,

= 0.044) were not significant. No significant interaction effects were found for group × gender, stimulus condition × group, stimulus condition × gender, or the three-way interaction (all

p > 0.3). For reaction time, no significant main effects or interaction effects were observed. Specifically, the main effects of group (

F = 0.032,

p = 0.859,

= 0.011), gender (

F = 2.699,

p = 0.106,

= 0.044), and stimulus condition (

F = 0.240,

p = 0.787,

= 0.004) were all non-significant. Likewise, all interaction effects (group × gender, stimulus condition × group, stimulus condition × gender, stimulus condition × group × gender) were non-significant (all

p > 0.3).

Although the repeated measures

ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of the PMU group on either accuracy or reaction time, descriptive statistics (

Table 2) showed a consistent trend in which children in the high PMU group tended to exhibit lower accuracy and slower responses across task conditions. This performance pattern was particularly evident among boys. These trends, while not statistically significant, are aligned with the significant interaction effects observed at the neural level. In Condition 1 (Position Task), children in the low PMU group showed generally higher accuracy, with girls (

M = 0.64,

SD = 0.18) and boys (

M = 0.62,

SD = 0.13) outperforming those in the high PMU group. Notably, boys in the high PMU group had the lowest accuracy (

M = 0.56,

SD = 0.15). In Condition 2 (Color Task), the overall accuracy improved compared to the location task. Girls in the low PMU group achieved the highest accuracy (

M = 0.74,

SD = 0.17), whereas boys in the high PMU group performed the worst (

M = 0.61,

SD = 0.13), suggesting that PMU may negatively affect performance on the color task. In Condition 3 (Dual Task), girls in both the low (

M = 0.71,

SD = 0.17) and high (

M = 0.68,

SD = 0.17) PMU groups showed higher accuracy, while boys in both the low (

M = 0.62,

SD = 0.12) and high (

M = 0.62,

SD = 0.11) PMU groups performed similarly. Overall, children in the low PMU group demonstrated higher accuracy across all tasks compared to those in the high PMU group. In addition, girls consistently outperformed boys under all conditions, with gender differences particularly pronounced in the color and dual tasks.

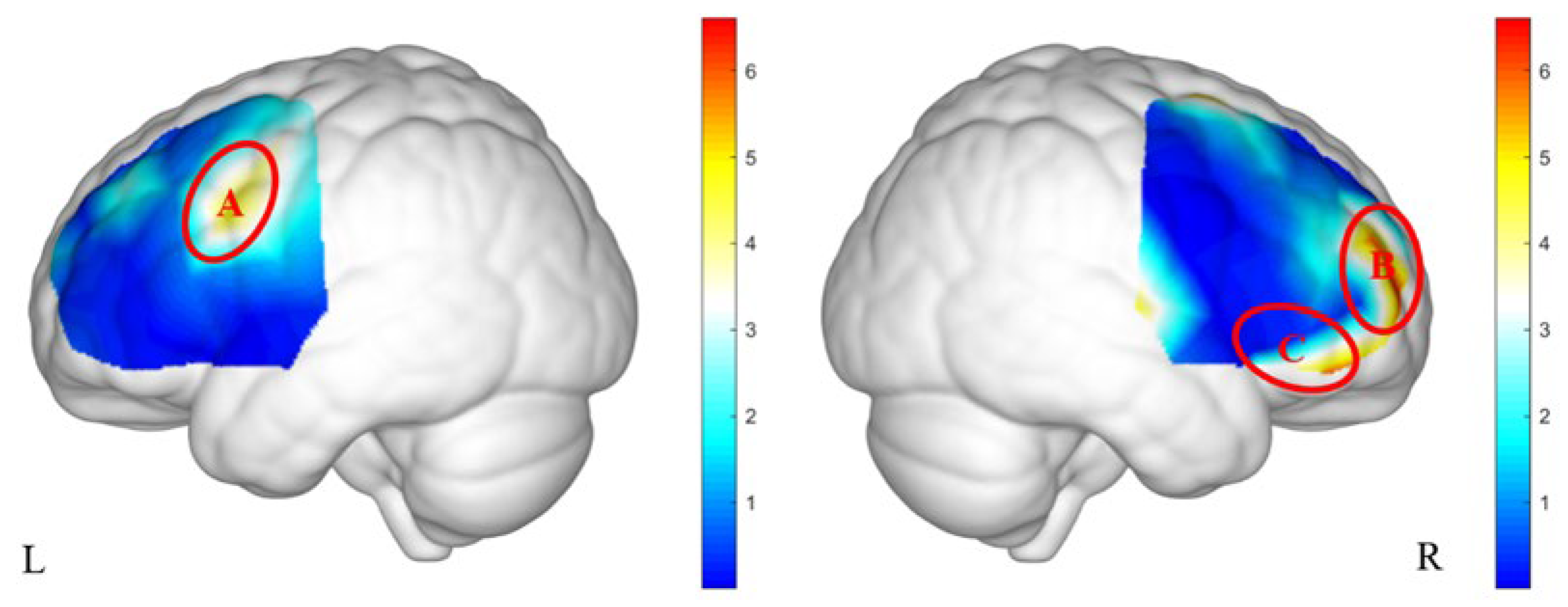

3.2. fNIRS Results

3.2.1. Differences in Brain Activation Between PMU Groups

The repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to compare brain activation levels between children with high and low levels of PMU. The results showed no significant differences between the two groups in all regions of interest (ROIs). Specifically, no significant group differences were found in ROI A (F = 0.48, p = 0.490, = 0.01), ROI B (F = 0.01, p = 0.934, = 0.00), and ROI C (F = 0.04, p = 0.848, = 0.00).

3.2.2. Differences in Brain Activation Between Genders

To examine potential gender differences in brain activation during the working memory task, a repeated measures ANOVA was performed. The results showed no significant differences between boys and girls across all ROIs. Specifically, no gender differences were found in ROI A (F = 0.19, p = 0.662, = 0.00), ROI B (F = 0.44, p = 0.510, = 0.01), and ROI C (F = 0.05, p = 0.822, = 0.00).

3.2.3. Differences in Brain Activation Under Different Stimulus Conditions

A repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to investigate the effects of different stimulus conditions (position, color, and dual-task) on brain activation. The results revealed no significant main effects of stimulus condition on brain activation in any ROI. Specifically, ROI A (F = 2.39, p = 0.096, = 0.04), ROI B (F = 0.99, p = 0.372, = 0.02), and ROI C (F = 0.34, p = 0.712, = 0.01) showed no significant activation differences under different task conditions.

3.2.4. Brain Activation Differences Under the Interaction Between Group and Gender

As shown in

Figure 4, significant interaction effects between group and gender were observed in ROI A (

F(61) = 5.88,

p = 0.027,

= 0.09), ROI B (

F(61) = 7.59,

p = 0.024,

= 0.12), and ROI C (

F(61) = 4.67,

p = 0.035,

= 0.08).

Post hoc analyses (see

Table 3) revealed that in ROI A, boys in the high PMU group exhibited significantly higher brain activation than boys in the low PMU group (p = 0.048). In contrast, in the low PMU group, girls showed significantly greater activation than boys (

p = 0.049). In ROI B, girls in the high PMU group showed higher activation compared to girls in the low PMU group (

p = 0.029), whereas in the low PMU group, boys exhibited greater activation than girls (

p = 0.020). No significant post hoc differences were observed in ROI C.

3.2.5. Brain Activation Differences under the Interaction between Stimulus Condition and Gender

The interaction effects between stimulus condition and gender were not statistically significant in any of the regions of interest, including ROI A (F(61) = 0.83, p = 0.439, = 0.01), ROI B (F(61) = 2.64, p = 0.078, = 0.04), and ROI C (F(61) = 0.55, p = 0.577, = 0.01). These results suggest that the influence of stimulus conditions on brain activation did not vary significantly by gender.

3.2.6. Brain Activation Differences under the Interaction between Stimulus Condition and Gender

Further analysis revealed significant three-way interaction effects among the group, stimulus condition, and gender in ROI B (

F(61) = 6.42,

p = 0.006,

= 0.10) and ROI C (

F(61) = 5.81,

p = 0.006,

= 0.19), as presented in

Figure 5.

Post hoc results (

Table 4) indicated that in ROI B, during the color task, boys in the low PMU group exhibited significantly higher activation than girls (

p = 0.001), and their activation during the color task was also greater than during the position task (

p = 0.039). In the high PMU group, boys showed significantly higher activation during the dual-task condition compared to the color task (p = 0.025). In ROI C, boys in the high PMU group showed higher activation during the dual-task condition than those in the low PMU group (

p = 0.009), while girls in the high PMU group exhibited lower activation than those in the low PMU group (

p = 0.027). Furthermore, within the low PMU group, girls showed greater dual-task activation than boys (

p = 0.021). In contrast, in the high PMU group, boys exhibited significantly greater activation than girls during the same condition (

p = 0.012).

4. Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between PMU and working memory in preschoolers, exploring behavioral performance and underlying neural activation patterns. The findings offer valuable insights into the cognitive and neural consequences of PMU in early childhood and highlight the moderating role of gender.

4.1. Working Memory Performance and Problematic Media Use

Although preschoolers with higher levels of PMU exhibited a trend toward lower accuracy on working memory tasks compared to their low-PMU peers, this difference did not reach statistical significance. This null finding at the behavioral level requires careful consideration. One possibility is that the sample size, while adequate for detecting neural effects, may have lacked the power to reveal subtle behavioral differences. Another explanation could be that the behavioral measures employed were not sensitive enough to capture the specific working memory processes affected by PMU. It is also plausible that the observed neural changes reflect compensatory mechanisms that allow children with high PMU to maintain behavioral performance despite underlying neural inefficiencies. This interpretation aligns with the neural compensation hypothesis [

40,

41], which posits that alternate neural pathways are recruited to maintain performance when primary cognitive circuits are compromised. Future research with larger samples and more sensitive behavioral measures is needed to clarify the relationship between PMU and working memory performance.

The absence of significant gender differences in working memory performance between PMU groups was unexpected. This may be attributed to the relative homogeneity of the sample regarding distal (e.g., socioeconomic status, digital environment), proximal (e.g., parenting style), and maintaining factors (e.g., parental regulation strategies) proposed by the IT-CPU [

1]. These factors may exert a more decisive influence than gender in this particular sample, potentially obscuring subtle gender-related differences in working memory performance at the behavioral level. Future studies with more demographic variables are needed.

4.2. Gender-Specific Brain Activation Patterns

While behavioral differences were non-significant, fNIRS data revealed distinct neural activation patterns. Girls exhibited greater activation in left-hemisphere regions associated with language processing (Broca's area, premotor cortex, supplementary motor area [BA6], inferior frontal gyrus [BA44]), while boys showed stronger activation in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC; BA9 and BA10), associated with spatial processing and executive functions [

42,

43]. These findings suggest that even in preschool, gender-specific neural pathways for cognitive processing are evident, potentially reflecting a preference for verbal encoding in girls and visuospatial strategies in boys, consistent with Dual-Coding Theory [

44].

The significant interaction between gender and PMU on brain activation further supports the moderating role of gender. Boys with high PMU showed increased activation in the same left-hemisphere language areas preferentially activated in girls with low PMU. Conversely, girls with high PMU exhibited increased activation in the right DLPFC, typically more active in boys with low PMU. These findings suggest compensatory neural recruitment in response to cognitive demands that are overloaded by excessive media exposure. Boys may shift away from their typical visuospatial dominance toward language-related areas, while girls may engage more in domain-general executive regions. Nevertheless, we need more empirical evidence to verify this compensatory neural recruitment mechanism.

4.3. Three-Way Interaction Effects

It is interesting to note that the three-way interaction of group, condition, and gender on DLPFC activation (ROI B and C) provides further nuance. In ROI B, boys with low PMU showed higher activation during the color task than girls and during the color task compared to the position task. Boys with high PMU showed higher activation during the dual-task than during the color task. In ROI C, boys with high PMU exhibited higher activation during the dual Task than those with low PMU, while girls showed the opposite pattern. These findings suggest that PMU's impact on neural function is context-specific, varying depending on the cognitive demands of the Task and the individual's gender. These complex interactions warrant further investigation to understand the precise mechanisms by which PMU affects specific working memory processes and, ultimately, to elucidate the sophisticated relationships between task, gender, and working memory.

In conclusion, this study provides emerging evidence that excessive media exposure in early childhood is associated with altered neural engagement during working memory tasks and that these effects are moderated by gender. These results underscore the need for tailored intervention strategies that account for gender differences in cognitive processing styles and neural plasticity. Future longitudinal studies are warranted to track whether these compensatory patterns persist, intensify, or diminish over time and to investigate their relationship with long-term cognitive and emotional development.

5. Conclusion, Limitations, and Implications

In conclusion, this study provides novel insights into the relationship between problematic media use (PMU) and working memory in preschool-aged children. While behavioral performance on the dual 1-back task did not differ significantly between high and low PMU groups, neuroimaging data revealed distinct patterns of prefrontal activation associated with PMU levels and gender. Specifically, high-PMU boys and low-PMU girls exhibited heightened activation in the left prefrontal regions, suggesting that PMU may differentially influence neural functioning across genders. Moreover, the observed three-way interaction among the PMU group, task condition, and gender underscores the context-dependent nature of these neural effects. These findings highlight the importance of considering both individual and situational factors when examining the cognitive and neural implications of early media exposure. Future research should further investigate the developmental trajectories and long-term consequences of PMU on executive functioning, ideally incorporating longitudinal designs and a range of diverse cognitive tasks.

This study has limitations, including reliance on parent-reported PMU, lack of control for pre-existing cognitive differences and socioeconomic status, the limited spatial resolution of fNIRS, and a relatively small sample size. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating objective measures of media use, controlling for relevant covariates, and using larger and more diverse samples. Longitudinal studies are crucial to track the developmental trajectory of these neural patterns and their long-term cognitive and emotional consequences. Furthermore, research exploring the effectiveness of interventions designed to mitigate the adverse effects of PMU on working memory, tailored to address gender-specific neural vulnerabilities, is warranted.

Despite these limitations, the findings offer important implications for early childhood education and parenting practices. First, the study reinforces the potential cognitive risks associated with excessive media use in early childhood, particularly concerning the development of working memory. This highlights the importance of collaborative efforts between educators and parents in establishing healthy media habits and minimizing excessive screen time. Second, the observed gender-specific neural responses underscore the need for tailored educational strategies that take into account individual differences. For example, interventions targeting boys might emphasize spatial cognitive games and attention training, given the observed differences in neural activation patterns. Third, this research contributes to the growing body of literature utilizing neuroimaging techniques in early childhood education, providing biological evidence to inform media usage guidelines and cognitive development strategies. Ultimately, the findings suggest the creation of sensory-rich, low-tech learning environments that prioritize face-to-face interaction, exploratory play, and balanced media exposure to foster optimal brain development in preschoolers. By integrating these findings into educational practice, we can better support children's cognitive development in the digital age.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.D.,X.D. and H.,L.; methodology, K.D.,X.D. and H.,L; analysis, K.D. and X.D; data curation, K.D., X.D and Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, K.D. and X.D; writing—review and editing, H.,L; supervision, K.D. and H.,L.; funding acquisition,K.D. and H.,L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant Numbers: 62277037 and 62407029] and the Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation [Grant Numbers: 24YJC880026].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shanghai Normal University (Ref. no. [2024] - 093).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

We are committed to sharing our data openly and transparently. The dataset of the present study, including deidentified participant data, processed brain measures, and functional assessments, will be made available upon reasonable request. Requests may be made to the corresponding authors, and approval from the sponsoring institution (Shanghai Normal University) is required.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PMU |

Problematic Media Use |

| fNIRS |

functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy |

| IT-CPU |

Interactional Theory of Childhood Problematic Media Use |

| SES |

Socioeconomic Status |

| P.R.C |

People's Republic of China |

| PMUM-SF |

Problematic Media Use Measure-Short Form |

| CRT |

Combined Raven’s Test |

| IFG |

Inferior Frontal Gyrus |

| MFG |

Middle Frontal Gyrus |

| SFG |

Superior Frontal Gyrus |

| MNI |

Montreal Neurological Institute |

| BA |

Brodmann Areas |

| ROI |

Regions of Interest |

Table A1.

Brodmann Areas Corresponding to fNIRS Channels.

Table A1.

Brodmann Areas Corresponding to fNIRS Channels.

| Channels |

BA |

Brain Coverage(%) |

| CH1 |

10 - Frontopolar area |

38.6% |

| 46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

35.7% |

| CH2 |

46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

51.9% |

| 47 - Inferior prefrontal gyrus |

47.3% |

| CH3 |

10 - Frontopolar area |

84.5% |

| CH4 |

10 - Frontopolar area |

99.3% |

| CH5 |

46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

87.6% |

| CH6 |

9 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

51.6% |

| CH7 |

9 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

48.0% |

| 46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

52.0% |

| CH8 |

8 - Includes Frontal eye fields |

55.5% |

| 9 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

44.5% |

| CH9 |

46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

83.7% |

| CH10 |

45 - pars triangularis Broca’s area |

70.6% |

| CH11 |

45 - pars triangularis Broca’s area |

54.5% |

| 46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

36.5% |

| CH12 |

45 - pars triangularis Broca’s area |

94.4% |

| CH13 |

38 - Temporopolar area |

100.0% |

| CH14 |

48 - Retrosubicular area |

59.9% |

| CH15 |

21 - Middle Temporal gyrus |

100.0% |

| CH16 |

45 - pars triangularis Broca’s area |

51.7% |

| CH17 |

44 - pars opercularis, part of Broca’s area |

75.4% |

| CH18 |

9 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

79.4% |

| CH19 |

6 - Pre-Motor and Supplementary Motor Cortex |

92.5% |

| CH20 |

6 - Pre-Motor and Supplementary Motor Cortex |

77.2% |

| CH21 |

4 - Primary Motor Cortex |

60.7% |

| CH22 |

43 - Subcentral area |

68.7% |

| CH23 |

1 - Primary Somatosensory Cortex |

34.4% |

| CH24 |

10 - Frontopolar area |

100.0% |

| CH25 |

10 - Frontopolar area |

100.0% |

| CH26 |

9 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

52.8% |

| 10 - Frontopolar area |

36.8% |

| CH27 |

10 - Frontopolar area |

81.1% |

| CH28 |

10 - Frontopolar area |

38.2% |

| CH29 |

46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

75.6% |

| CH30 |

46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

47.7% |

| 47 - Inferior prefrontal gyrus |

52.3% |

| CH31 |

45 - pars triangularis Broca’s area |

46.2% |

| 46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

47.8% |

| CH32 |

38 - Temporopolar area |

96.0% |

| CH33 |

46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

76.1% |

| CH34 |

45 - pars triangularis Broca’s area |

57.1% |

| 46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

42.9% |

| CH35 |

9 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

63.8% |

| 46 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

36.2% |

| CH36 |

45 - pars triangularis Broca’s area |

41.9% |

| CH37 |

8 - Includes Frontal eye fields |

60.2% |

| 9 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

39.8% |

| CH38 |

9 - Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

77.8% |

| CH39 |

6 - Pre-Motor and Supplementary Motor Cortex |

75.4% |

| CH40 |

45 - pars triangularis Broca’s area |

100.0% |

| CH41 |

44 - pars opercularis, part of Broca’s area |

78.4% |

| CH42 |

48 - Retrosubicular area |

51.0% |

| CH43 |

6 - Pre-Motor and Supplementary Motor Cortex |

32.3% |

| 43 - Subcentral area |

63.6% |

| CH44 |

21 - Middle Temporal gyrus |

100.0% |

| CH45 |

21 - Middle Temporal gyrus |

33.0% |

| 22 - Superior Temporal Gyrus |

67.0% |

| CH46 |

6 - Pre-Motor and Supplementary Motor Corte |

94.3% |

| CH47 |

1 - Primary Somatosensory Cortex |

35.1% |

| CH48 |

4 - Primary Motor Cortex |

57.6% |

| 6 - Pre-Motor and Supplementary Motor Cortex |

34.5% |

Table A2.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

Table A2.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

| Variable |

Low PMU Group(n = 32)

|

High PMU Group

(n = 30)

|

F |

p |

|

|

M(SD)

|

M(SD)

|

| Gender1

|

11/21 |

14/16 |

0.972 |

0.438 |

- |

| Age |

4.67 (0.66) |

4.53 (0.67) |

0.640 |

0.427 |

0.011 |

| SPM2

|

22.56 (9.68) |

21.87 (6.01) |

0.114 |

0.737 |

0.002 |

| Father’s education level |

5.00 (0.14) |

5.03 (0.14) |

0.033 |

0.864 |

0.000 |

| Mother’s education level |

4.88 (0.79) |

5.17 (0.59) |

1.317 |

2.664 |

0.108 |

| Father’s occupation |

3.63 (1.54) |

3.50 (1.98) |

0.078 |

0.781 |

0.001 |

| Mother’s occupation |

5.03 (2.60) |

5.37 (2.39) |

0.280 |

0.599 |

0.000 |

| Annual family income |

8.13 (2.35) |

8.03 (2.53) |

0.022 |

0.883 |

0.000 |

| SES |

- 0.25 (2.00) |

0.27 (1.67) |

1.210 |

0.276 |

0.020 |

References

- Domoff, S.E.; Borgen, A.L.; Radesky, J.S. Interactional Theory of Childhood Problematic Media Use. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2020, 2, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.; Rees, P.; Hale, L.; Bhattacharjee, D.; Paradkar, M.S. Association between Portable Screen-Based Media Device Access or Use and Sleep Outcomes. JAMA Pediatrics 2016, 170, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiro, M.; Overington, D. Self-Luminous Devices and Melatonin Suppression in Adolescents. Lighting Research & Technology 2016, 48, 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Yim, H.W.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, H.K.; Potenza, M.N.; Jo, S.-J.; Son, H.J. Reciprocal Relationship between Depression and Internet Gaming Disorder in Children: A 12-Month Follow-up of the iCURE Study Using Cross-Lagged Path Analysis. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2019, 8, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wu, D.; Yang, J.; Luo, J.; Xie, S.; Chang, C. Tablet Use Affects Preschoolers’ Executive Function: FNIRS Evidence from the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task. Brain Sciences 2021, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radesky, J.S.; Christakis, D.A. Increased Screen Time. Pediatric Clinics of North America 2016, 63, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venetsanou, F.; Kambas, A.; Gourgoulis, V.; Yannakoulia, M. Physical Activity in Pre-School Children: Trends over Time and Associations with Body Mass Index and Screen Time. Annals of Human Biology 2019, 46, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Dong, X.; Liu, D.; Li, H. How Early Digital Experience Shapes Young Brains during 0-12 Years: A Scoping Review. Early Education and Development 2023, 35, 1395–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, D.; Luo, J.; Xie, S.; Chang, C.; Li, H. Neural Correlates of Mental Rotation in Preschoolers With High or Low Working Memory Capacity: An fNIRS Study. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piaget, J.; Cook, M. The Origins of Intelligence in Children; International universities press: New York, USA, 1952; pp. 18–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Cole, M., Vera, J.-S., Sylvia, S., Ellen, S., Eds.; Harvard University Press: London, England, 1978; pp. 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutz, D.C.; Roberts, D.F.; Vuuren, D.P. van Reconsidering the Displacement Hypothesis. Communication Research 1993, 20, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.G.; Gurevitch, M. Uses and Gratifications Research. Public Opinion Quarterly 1973, 37, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C.; Cao, S.; Li, H. Profiles and Predictors of Young Children’s Digital Literacy and Multimodal Practices in Central China. Early Education and Development 2022, 33, 1094–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikken, P.; Opree, S.J. Guiding Young Children’s Digital Media Use: SES-Differences in Mediation Concerns and Competence. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2018, 27, 1844–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, E.N.; Whitaker, R.C.; Marino, A.J.; Anderson, S.E. Screen Time at Home and School among Low-Income Children Attending Head Start. Child Indicators Research 2013, 7, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emond, J.A.; Tantum, L.K.; Gilbert-Diamond, D.; Kim, S.J.; Lansigan, R.K.; Neelon, S.B. Household Chaos and Screen Media Use among Preschool-Aged Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Georgiou, G.K.; Manolitsis, G. Modeling the Relationships of Parents’ Expectations, Family’s SES, and Home Literacy Environment with Emergent Literacy Skills and Word Reading in Chinese. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 2018, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domoff, S.E.; Lumeng, J.C.; Kaciroti, N.; Miller, A.L. Early Childhood Risk Factors for Mealtime TV Exposure and Engagement in Low-Income Families. Academic Pediatrics 2017, 17, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hefner, D.; Knop, K.; Schmitt, S.; Vorderer, P. Rules? Role Model? Relationship? The Impact of Parents on Their Children’s Problematic Mobile Phone Involvement. Media Psychology 2018, 22, 82–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.; Nussbaum, M.; Preiss, D.D. Is the Use of Information and Communication Technology Related to Performance in Working Memory Tasks? Evidence from Seventh-Grade Students. Computers & Education 2011, 57, 2068–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanasiou, K.; Drosos, C.; Tseles, D.; Piromalis, D.; Tsotsolas, N. Digital Storytelling as a Teaching Method in Adult Education - The Correlation between Its Effectiveness and Working Memory. European Journal of Education Studies 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Benke, G.; Dimitriadis, C.; Inyang, I.; Sim, M.R.; Wolfe, R.; Croft, R.J.; Abramson, M.J. Use of Mobile Phones and Changes in Cognitive Function in Adolescents. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2010, 67, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharony, N.; Zion, A. Effects of WhatsApp’s Use on Working Memory Performance among Youth. Journal of Educational Computing Research 2019, 57, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmayne, M.; Smith, C.L.; Benke, G.; Croft, R.J.; Dalecki, A.; Dimitriadis, C.; Kaufman, J.; Macleod, S.; Sim, M.R.; Wolfe, R.; et al. Use of Mobile and Cordless Phones and Cognition in Australian Primary School Children: A Prospective Cohort Study. Environmental Health 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive Functions. Annual Review of Psychology 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behavior Research Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Hu, K.; Chen, G.; Jin, Y.; Li, M. “A Pilot Study Report on the Combined Raven’s Test (CRT) in Urban Shanghai ”(in Chinese). Journal of Psychological Science 1988, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.R. Massive IQ Gains in 14 Nations: What IQ Tests Really Measure. Psychological Bulletin 1987, 101, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, T.; Geng, F.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, F. Training on Abacus-Based Mental Calculation Enhances Visuospatial Working Memory in Children. The Journal of Neuroscience 2019, 39, 6439–6448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Xiao, B.; Li, Y.; Li, H. Translation and Validation of the Chinese Version of the Problematic Media Use Measure. Early Education and Development 2023, 35, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzadi, S.; Einalou, Z.; Dadgostar, M. Investigation of Functional Connectivity During Working Memory Task and Hemispheric Lateralization in Left- and Right- Handers Measured by fNIRS. Optik 2020, 221, 165347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, T.J.; Diamond, S.G.; Franceschini, M.A.; Boas, D.A. HomER: A Review of Time-Series Analysis Methods for near-Infrared Spectroscopy of the Brain. Applied Optics 2009, 48, D280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, Y.; Hiraki, K. Neural Origin of Cognitive Shifting in Young Children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 6017–6021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpy, D.T.; Cope, M.; Zee, P. van der; Arridge, S.; Wray, S.; Wyatt, J. Estimation of Optical Pathlength through Tissue from Direct Time of Flight Measurement. Physics in Medicine and Biology 1988, 33, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaram, R.; Zhang, H.; Guan, C.; Thulasidas, M.; Hoshi, Y.; Ishikawa, A.; Shimizu, K.; Birbaumer, N. Temporal Classification of Multichannel Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Signals of Motor Imagery for Developing a Brain–Computer Interface. NeuroImage 2007, 34, 1416–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, R.; Anderson, N.D.; Locantore, J.K.; McIntosh, A.R. Aging Gracefully: Compensatory Brain Activity in High-Performing Older Adults. NeuroImage 2002, 17, 1394–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter-Lorenz, P.A.; Cappell, K.A. Neurocognitive Aging and the Compensation Hypothesis. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2008, 17, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, O.; Ernst, T.; Braun, J.; Koch, C.; Miller, E.; Chang, L. Gender Differences in the Functional Organization of the Brain for Working Memory. NeuroReport 2000, 11, 2581–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S.L.; Mohamed, F.B.; Platek, S.M. Common Ground for Spatial Cognition? A Behavioral and fMRI Study of Sex Differences in Mental Rotation and Spatial Working Memory. Evolutionary Psychology 2005, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.M.; Paivio, A. Dual Coding Theory and Education. Educational Psychology Review 1991, 3, 149–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).