1. Introduction

Online social media, including social networking sites and instant messengers, have become a central part of everyday life. Today, young people grow up in a hybrid world where offline and online environments, interactions, and experiences are deeply intertwined. Indeed, recent research among North-American and European youth found that almost four in ten adolescents use popular social media platforms almost constantly throughout the day [

1,

2,

3]. Although social media help adolescents navigate critical developmental tasks, such as constructing a self- and social identity and maintaining relationships with peers, there is a growing recognition that some youths are unable to regulate their social media use (SMU) and, as a result, experience difficulties in important life domains (e.g., [

4,

5,

6]).

Problematic social media use (PSMU), also referred to in the literature as social media addiction, social media disorder, and compulsive social media use, is generally defined as maladaptive use of social media characterized by addiction-like symptoms and/or reduced self-regulation despite unfavorable consequences [

6,

7]. Studies have linked PSMU to lower mental well-being and life satisfaction (e.g., [

6,

8,

9]), attention difficulties (e.g., [

10,

11]), lower sleep quality (e.g., [

4,

12,

13]), and poorer academic performance (e.g., [

9,

14]).

Considering these impacts, it is critical to determine when and which youth are at higher risk of developing PSMU, as well as key factors that should be targeted for prevention and (early) intervention. This is the focus of this study. In order to achieve this, we propose using two complementary approaches, namely, logistic regression analysis and psychological network analysis, to approach the problem from both a theory-driven and a data-driven perspective. We demonstrate empirically that richer insights are generated with this approach compared to either approach applied on its own.

This paper is structured as follows. In

Section 2, we provide a background on research about problematic social media use, as well as on the two analytical approaches used in our study.

Section 3 starts with an overview of the specific aims, introduces the data and measures, and provides details for our analysis methodology.

Section 4 provides both descriptive statistics for our data and empirical results for the two approaches we contrast and combine here. We discuss our findings at length in

Section 5, and conclude in

Section 6.

2. Related Work

2.1. Theory-Driven vs. Data-Driven Approaches

In quantitative social sciences, efforts to understand social phenomena like PSMU have traditionally been guided by confirmatory-explanatory approaches that seek to test theory-derived hypotheses about causal processes (e.g., risk and protective factors) by collecting empirical data and evaluating the goodness-of-fit of these data to the hypothesized models [

15]. Because they are constrained by theory, designs and data analysis tools within this tradition (e.g., randomized controlled trials, regression models) prioritize parsimony, considering only a few factors believed to affect the outcome of interest [

16,

17]. Such theory-driven, parsimonious models can help explain individual effects, refine theory, and guide interventions. However, they often fail to provide a comprehensive understanding of the phenomena being studied.

With the emergence of big data analysis approaches, social scientists have grown increasingly interested in more inductive-exploratory approaches to data analysis. These alternative approaches rely on computer-aided analysis and methods from computer science (e.g., expert systems, machine learning algorithms, data mining) to iteratively estimate complex models of social phenomena that best represent the observed data [

15]. Data-driven techniques enable the exploration of different objectives and questions; for example, they can be used to analyze the structure of multivariate data in the absence of theory on how variables are related and identify patterns of risk and resilience that theory-driven approaches to model building may have missed. These structures might then generate new causal hypotheses that can be tested empirically [

16,

17]. Given the distinct advantages of theory-driven and data-driven approaches, the current study aims to combine both strategies to deepen our understanding of the factors that differentiate adolescents at risk of developing PSMU from normative users.

From a theoretical perspective, the various risk and protective factors involved in the development of PSMU do not operate in isolation but through a complex system of multiple pathways and dynamic interactions [

18]. That is, the components within the system likely influence not only PSMU but also have positive, negative, unidirectional, or reciprocal effects on each other. However, as we will detail in the next subsection, traditional analytical approaches to studying PSMU often focus on discrete aspects of this system. Even when a broader range of variables is investigated, covariances among these factors are either not the focus of attention or explained in terms of a common underlying variable (e.g., PSMU) rather than direct interactions. For example, multiple regression models that aim to describe the linear relationship between a key outcome variable and several predictor variables compute the unique variance in the target variable explained by each predictor while removing the effect of all other predictors from that relation. Similarly, at the symptom level, the use of principal component analysis and sum scores of symptoms to describe PSMU is based on the idea that these symptoms (e.g., preoccupation, withdrawal, problems) are passive indicators of which PSMU is the common underlying cause. Such methods provide important insights, but cannot account for the complex interrelations among risk and protective factors, or for the possibility that intervening in one factor may positively affect other components in the system.

2.2. Predictors of Problematic Social Media Use

Until now, most empirical work on factors involved in PSMU has concentrated on intrapersonal characteristics. For instance, in line with the body of evidence linking attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to addictions more generally (e.g., [

19]), studies have demonstrated that ADHD symptoms (e.g., attention problems, impulsivity, hyperactivity) predict higher levels of PSMU [

10,

11,

20]. Adolescents with ADHD symptoms may be more easily distracted by the constant stream of information and notifications inherent in social media platforms and have more difficulty inhibiting their immediate impulses, resulting in more compulsive SMU. In addition, the association with psychological distress and mental well-being factors has been extensively analyzed. Studies have shown that individuals with depression, low life satisfaction, and low (physical) self-esteem are more likely to engage in PSMU (e.g., [

6,

20,

21,

22]). These relationships are frequently depicted as cyclic: adolescents turn to social media to manage emotional issues or psychosocial vulnerabilities, leading to immediate rewards such as mood enhancement and increased self-efficacy, which then drive them to continued and increased SMU. This increased engagement, in turn, reinforces preexisting issues, prompting further reliance on social media as a coping mechanism [

5,

6]. Others, however, have argued that the relationships between mental well-being factors and PSMU are highly complex; influenced by culturally relevant factors like gender difference [

23], but also intervening and mediating variables with poorly understood underlying mechanisms [

22,

24].

In addition to psychological functioning and well-being factors, several personality traits have been linked to PSMU. For instance, individuals with elevated narcissistic traits are thought to be more prone to developing PSMU because the specific attributes of social media (e.g., carefully curated self-presentation, explicit validation in the form of “likes” and followers, a potentially large audience) offer them an ideal environment to fulfill their self-enhancement and self-validation needs [

21,

25]. Moreover, a growing body of research has highlighted the role of fear of missing out (FoMO) in the etiology of PSMU. FoMO, defined as “a pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent” [

26], may trigger compulsive SMU through a strong desire to remain continuously connected with what others are doing [

26,

27]. FoMO has also been found to act as a mediator between deficits in psychological needs (i.e., competence, autonomy, and relatedness) and PSMU [

26,

27,

28], explaining, for example, observed associations between depression or low life satisfaction and PSMU [

22,

24].

Surprisingly, the role of the social environment in PSMU has received much less attention, despite both theoretical perspectives (e.g., ecological systems theory, [

18]; transactional model, [

29]) and empirical studies emphasizing the crucial role of the family and peer context in developmental processes and outcomes during adolescence, including in the domain of problematic behavior [

30]. Moreover, SMU is inherently interpersonal and pivotal to forming and maintaining relationships. Studies have suggested that adolescents who suffer from loneliness and poor (perceived) social competencies tend to prefer online social interactions over offline encounters with peers because they find them less threatening and more efficacious in positively presenting themselves. The perceived benefits and control experienced through SMU may subsequently foster maladaptive beliefs (e.g., that one can only be successful online) that can eventually lead to PSMU [

31,

32].

In the family context, only a few studies have explored how parental mediation can promote or prevent PSMU, and findings on the role of parental mediation in general compulsive Internet use have been somewhat inconsistent due to assessment differences. Nevertheless, the available evidence suggests that restrictive parental rule-setting (i.e., setting clear rules in advance regarding adolescents’ access to social media) may be more effective in protecting against PSMU than reactive parental rule-setting (i.e., ad-hoc restrictive responses to adolescents’ SMU; [

33,

34]). In line with this finding, a recent study found that restricting Internet access through rule-setting may no longer have the desired protective effect when adolescents have already become highly engaged users [

35]. [

36] investigated parental mediation in gaming addiction, and found minimal effects. Finally, studies have suggested that parent-adolescent communication about online behavior based on mutual respect, in which adolescents feel comfortable, understood, and taken seriously by their parents, may help prevent PSMU [

34].

In sum, prior research indicates that many factors on the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels may be involved in the etiology of PSMU. However, to our knowledge, studies have yet to look at personal, peer, and parent factors simultaneously to understand their relative contribution in predicting PSMU among adolescents.

2.3. Two Analytical Approaches to Studying Problematic Social Media Use

In recent years, a promising alternative analytical approach in psychological research –the psychological network approach– has gained traction that allows for a better understanding of the structure of psychopathology. The network approach assumes that psychological phenomena form complex systems of causally interacting components (e.g., [

37,

38]). According to this perspective, PSMU consists of the networks of relationships between cognitions, traits, emotional states, behaviors, and contextual factors; it is the emergent phenomenon from a system of dynamic interactions between these components rather than the root cause of all of them.

Psychological network analysis offers insight into the structural organization of psychological phenomena and the roles played by specific factors in the network in a data-driven manner. The network structures can be graphically depicted as nodes representing observed variables and edges indicating pathways on which nodes affect each other [

37,

39]. This approach also identifies “central” factors defined by strongly connected nodes. Due to their strong relations with other nodes and/or their high interconnectedness, such factors are likely to have a greater influence over the entire network [

40].

It should be noted that although network edges are conceptualized as causal effects between factors, psychological network analysis is a fundamentally exploratory technique, and the estimated connections can, therefore, only be considered as hypothesis-generating for potential causal pathways that require further statistical testing [

40].

To our knowledge, only a few studies have utilized psychological network analysis to investigate PSMU, and these have either focused on the organization of PSMU symptoms (e.g., [

13,

41]) or the associations between PSMU and personal factors (e.g., [

42,

43]). No studies have explored patterns of relationships among potential personal, peer, and parent predictors of PSMU using the psychological network approach. It has been applied in other, related healthcare domains, such as prediction of treatment responses [

44], with promising results.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview

Our study adds to the existing literature on the risk and protective factors of PSMU in at least three ways. First, based on the number of PSMU symptoms present, we discriminate between normative social media users vs. at-risk and problematic users. A recent representative study among 6,626 Dutch adolescents [

31] found that only 3.6% of adolescents met criteria for PSMU (i.e., six to nine symptoms); however, a substantial group (34.8%) reported at-risk SMU (two to five symptoms). Importantly, this study concluded that not only problematic, but also at-risk users were more likely than normative users to experience adverse consequences due to their SMU. Therefore, the current study seeks to identify risk and protective factors for at-risk/problematic SMU.

Second, because many interrelated factors may be involved in the development of PSMU, we simultaneously investigate a set of personal, peer, and parent characteristics that previously have been linked to PSMU or, more generally, to Internet-use disorders. Specifically, within the personal domain, we investigate the role of ADHD symptoms, depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, self-esteem, physical self-esteem, narcissism, and FoMO. Within the peer domain, we explore perceived social competence and the intensity of face-to-face meeting with friends. Finally, within the parent domain, we investigate restrictive and reactive parental rules regarding SMU and the quality of communication about Internet-related matters. Studying these three domains of influence together yields a more comprehensive profile of youth at risk for developing PSMU and may improve predictive accuracy.

Third, given that traditional statistical approaches to studying psychopathology are less suited for capturing the interrelatedness of risk and protective factors that drive PSMU, the current study utilizes two complementary methods to explore which factors are particularly relevant in identifying at-risk/problematic SMU among adolescents. We use logistic regression analysis to evaluate the relative contribution of the personal, peer, and parent factors in predicting the likelihood of being an at-risk/problematic social media user in three consecutive years. In addition, we use psychological network analysis to explore the network structure of potential risk and protective factors and identify central factors in the network. These two complementary approaches provide novel insights into key factors and processes that distinguish at-risk/problematic social media users from normative users.

3.2. Participants and Procedure

Data for this study came from the Digital Youth Project project, a longitudinal study on online behaviors and wellbeing among Dutch secondary school students [

9]. For the present study, data from the second, third, and fourth waves were used, which took place in February and March of 2016, 2017, and 2018, respectively. Data from the first assessment (2015) were excluded, as some of the variables of interest were not measured in this wave. The waves included in the current study are further referred to as T1, T2, and T3. In total, n=3,799 respondents participated in at least one of the three assessments (n=644 contributed data at all three waves, n=1,622 at two waves, and n=1,533 at one wave). Non-response and variation in sample sizes between waves were mainly due to entire schools or classes (e.g., exam classes) dropping out of the project and new schools or classes joining the project.

At T1, 1,928 adolescents participated in the study (56.7% boys). Respondents were between 10 and 16 years of age (M=13.31, SD=0.91), and 37.1% were first year (7th grade) students. Most adolescents (74.3%) had a Dutch ethnic background. Students were enrolled in pre-vocational (68.9%), higher general (27.1%), and pre-university (4.0%) education. At T2, 2,708 adolescents between 11 and 17 years of age (M=13.94, SD=1.20) completed the survey. Sample characteristics at T2 were similar to T1 (53.9% boys; 74.6% Dutch ethnic background; 62.6% pre-vocational, 27.4% higher general, 10.0% pre-university levels). At T3, 2,073 adolescents between 11 and 18 years of age (M=14.37, SD=1.49) participated. Due to practical reasons, two pre-vocational level schools and several pre-vocational level classes from mixed schools dropped out at this wave, resulting in a sample with a higher educational level than T1 and T2 (52.1% boys; 78.7% Dutch ethnic background; 45.2% pre-vocational, 39.9% higher general, 14.9% pre-university levels).

Data were collected through online self-report questionnaires administered in the classroom setting using Qualtrics survey software. Trained research assistants were present to supervise data collection, answer questions, and ensure respondents’ privacy. Prior to the survey assessment, parents were provided information about the study and the opportunity to decline their child’s participation. Adolescents with passive informed parental consent were informed about the purpose of the study, that participation was voluntary and anonymous, and that they could withdraw their participation at any time.

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. At-Risk/Problematic SMU

Adolescents’ PSMU was assessed with the Social Media Disorder Scale (SMDS) [

45]. This scale consists of nine dichotomous items (0=no, 1=yes) that cover symptoms of addiction to social media, including preoccupation, withdrawal, tolerance, persistence, displacement, conflict, deception, escape, and problems. For example, to measure withdrawal, respondents were asked, “During the past 12 months, have you often felt bad when you could not use social media?” The SMDS corresponds to the nine diagnostic criteria for internet gaming disorder outlined in the appendix of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition [

46] and has been found to have solid structural, convergent, and criterion validity and good reliability among adolescents [

31,

45].

A sum score was computed to reflect the number of present criteria. Based on a recent representative Dutch study [

31], respondents who reported zero or one symptom were classified as normative users, and respondents who reported two or more symptoms were classified as at-risk/problematic users. Given the dichotomous nature of the SMDS, internal consistency was calculated using the tetrachoric correlation matrix. This yielded an ordinal

that varied between .83 and .86 across waves.

3.3.2. Predictors of At-Risk/Problematic SMU

To examine which factors are particularly relevant in identifying at-risk or problematic SMU among adolescents, a set of personal, peer, and parent characteristics was assessed. Table 1 summarizes the instruments used to measure these constructs. Unless stated otherwise, mean scores were calculated for each predictor variable, with higher scores indicating a higher level of the measured construct.

3.4. Analytical Approach

3.4.1. Imputation of Missing Data

Due to the aforementioned variation in sample sizes across waves, missing data on the study variables was substantial. To retain respondents with partially missing data in the analysis, multiple imputation (MI) via chained equations was used to impute missing values. MI has been shown to be superior to listwise deletion as it improves statistical power and reduces potential bias related to missing data [

47].

Prior to imputation, steps were taken to ensure that only intended values were imputed. First, as the Digital Youth Project focuses on secondary school students, only cases who were in secondary school during all three waves were eligible for imputation. Respondents who did not participate in earlier waves because they were still in primary school during that time and respondents who did not participate in later waves because they had already left secondary school were excluded, as imputation of missing data would not be justified in their case. This resulted in a final sample of N=2,441 respondents.

Second, missing values in demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, educational level) were replaced or calculated using observed information from other waves. The percentage of missing data on study variables ranged from 25.7% (PSMU, T2) to 57.2% (quality of communication, T3). Using R’s mice 3.9.0 package [

48], five multiple imputed datasets were created using fully conditional specification (i.e., iterative, based on a predefined imputation model). The imputation models included gender, age, educational level, and the study variables as predictors (variables were included only if they had at least 50% usable cases and a minimum correlation of 0.2 with the target variable). For continuous items, imputation was based on predictive mean matching, whereas logistic regression was used for dichotomous items.

3.4.2. Data Analysis

Because the current study aimed to identify factors distinguishing at-risk/problematic social media users from normative users by using both logistic regression methods and psychological network analyses (i.e., rather than testing longitudinal associations), waves were treated as three separate, cross-sectional datasets.

First, descriptive statistics were calculated for the total sample and normative and at-risk/problematic social media users separately. Bivariate correlations between study variables were obtained for the total sample. Second, logistic regression analyses were performed in R to identify personal, peer, and parent factors associated with higher odds of at-risk/problematic SMU at each wave. All predictor variables were entered simultaneously into the regression model with at-risk/problematic SMU as dependent dichotomous variable (0=normative SMU, 1=at-risk/problematic SMU). Third, psychological networks were estimated using Gaussian graphical models [

49]. In these models, nodes represent personal, peer, and parent variables and edges represent their partial correlations (i.e., the relationship between two variables after controlling for the effect of all other variables in the network). Given the large number of parameters typically estimated in psychological networks, it is recommended to regularize partial correlations using the graphical LASSO algorithm (glasso; [

50]). This algorithm reduces small or unstable edges to zero to obtain a parsimonious network that only reflects the most robust interactions between nodes.

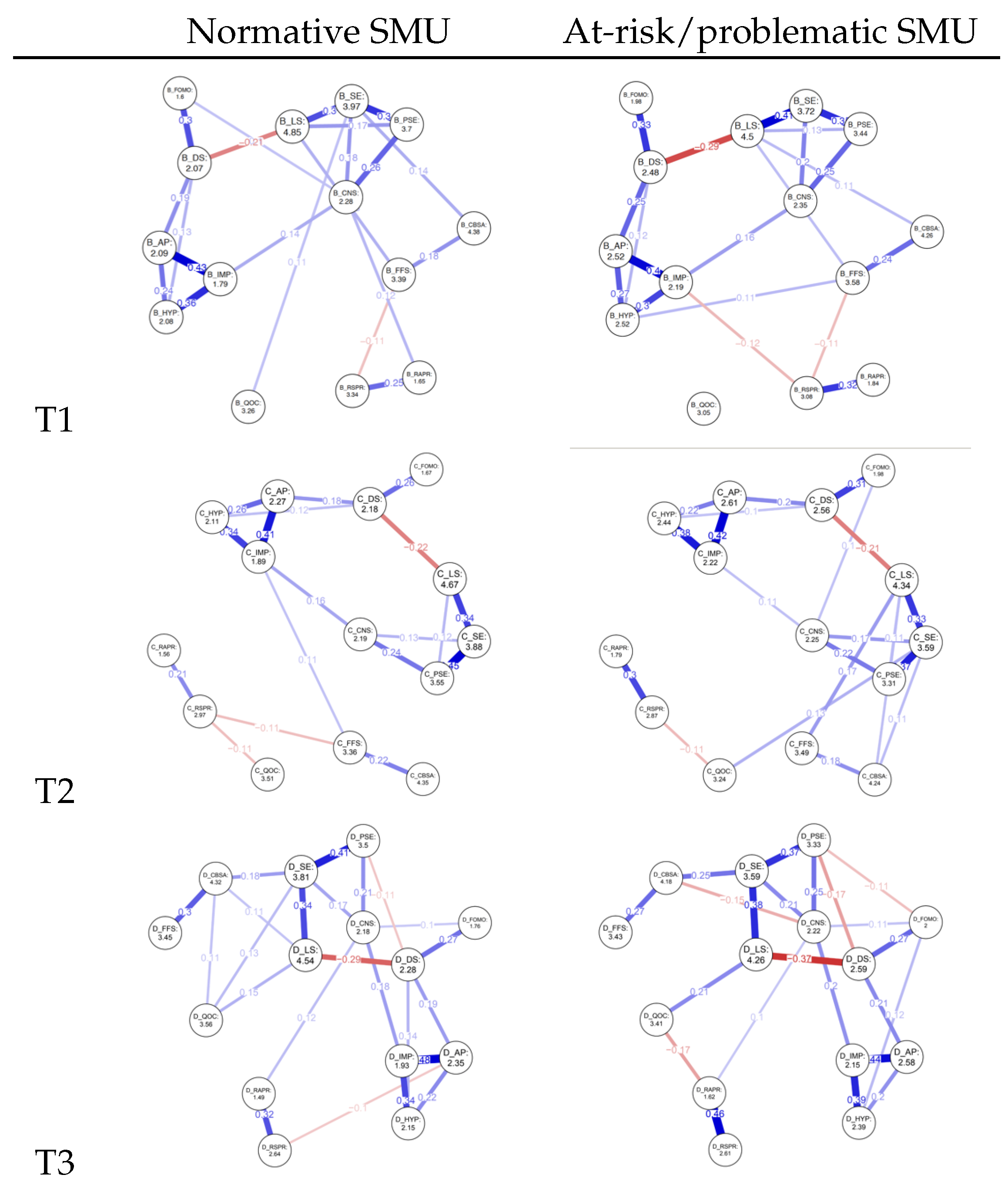

Separate networks were estimated for normative and at-risk/problematic users at each wave. Networks were estimated in R using the qgraph package [

51], which implements the glasso regularization in combination with the extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC) to select the most optimal estimation [

50]. The Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm was used to visualize networks so that closely spaced nodes represent strongly connected variables and thicker edges represent stronger associations. To interpret the estimated networks, stability and centrality indices were calculated using R’s bootnet package. Stability indices provide insight into (a) the accuracy of edge weights by calculating their bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs), and (b) the stability of centrality indices by applying a case-dropping subset bootstrap and calculating a correlation-stability (CS) coefficient [

40]. Centrality indices reflect the importance of nodes in the network. For each node, strength (the sum of the absolute edge weights connected to a node), betweenness (the number of times a node is on the shortest path between two other nodes, indicating a potential bridging factor), and closeness (how closely located, on average, a node is to other nodes) were calculated. We refer the reader to [

39,

40] for more details on network estimation, regularization, stability, and centrality.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

At T1, 34.5% of respondents were classified as at-risk/problematic social media users (of which 1.7% were problematic users with six or more symptoms), at T2 33.7% (1.7% problematic users), and at T3 36.6% (0.9% problematic users).

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the total sample and for normative and at-risk/problematic social media users. Correlations between the study variables are available in Supplementary Material S1. Independent samples t-tests (Benjamini-Hochberg corrected, Q=0.05) revealed significant differences between normative users and at-risk/problematic users on most personal, peer, and parent variables. Across waves, at-risk/problematic users reported significantly more ADHD symptoms, depressive symptoms, FoMO, intensity of meeting with friends, and reactive parental rules regarding SMU than normative users. At-risk/problematic users also consistently reported lower life satisfaction, self-esteem, physical self-esteem, perceived social competence, and quality of communication with parents.

4.2. Logistic Regression Analyses

Table 2 displays results of the logistic regression analyses examining the contribution of personal, peer, and parent factors in predicting adolescents’ at-risk/problematic SMU. Across all waves, higher levels of FoMO and reactive parental rules regarding SMU were associated with higher odds of being an at-risk/problematic social media user. Odds ratios ranged between 1.23-1.54 for FoMO and 1.26-1.39 for reactive parental rules. Other associations were less consistent across waves. Regarding personal factors, higher levels of impulsivity (

=1.26;

=1.27), depressive symptoms (

=1.32;

=1.29), and narcissism (

=1.36) were associated with significantly higher odds of at-risk/problematic SMU. Conversely, higher self-esteem levels (

=0.76) were associated with lower odds of at-risk/problematic SMU. Among the peer variables, increased intensity of meeting with friends was associated with higher odds of being an at-risk/problematic social media user (

=1.20;

=1.20). Finally, regarding parent variables, more restrictive parental rules regarding SMU (

=0.84) and higher communication quality (

=0.80) were associated with lower odds of at-risk/problematic SMU. The set of personal, peer, and parent variables accounted for 10%-19% of the variance in at-risk/problematic SMU.

4.3. Psychological Network Analyses

4.3.1. Network Structure

Figure 1 presents the estimated psychological networks at each time point for normative (left) and at-risk/problematic social media users (right). Supplementary Material S2 shows their bootstrapped edge weight means and 95% CIs. Overall, the networks had much of their structure in common. Two clusters of tightly connected personal variables were consistently observed: one cluster representing attention problems, impulsivity, and hyperactivity (i.e., ADHD symptoms), and another consisting of narcissism, physical self-esteem, self-esteem, life satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and FoMO. Additionally, stable intra-domain relations between perceived social competence and intensity of meeting with friends and between reactive and restrictive parental rules were present in all networks. As expected, the strongest edges were observed within the two personal clusters: attention problems and impulsivity; impulsivity and hyperactivity; self-esteem and physical self-esteem; self-esteem and life satisfaction; depressive symptoms and FoMO. Bridging these clusters, stable connections were found between attention problems and depressive symptoms and between impulsivity and narcissism. Inter-domain edges appeared less consistent and stable (based on bootstrapped CIs); however, stable links between self-esteem and perceived social competence, and between life satisfaction and quality of communication were present for both groups at T3.

4.3.2. Centrality

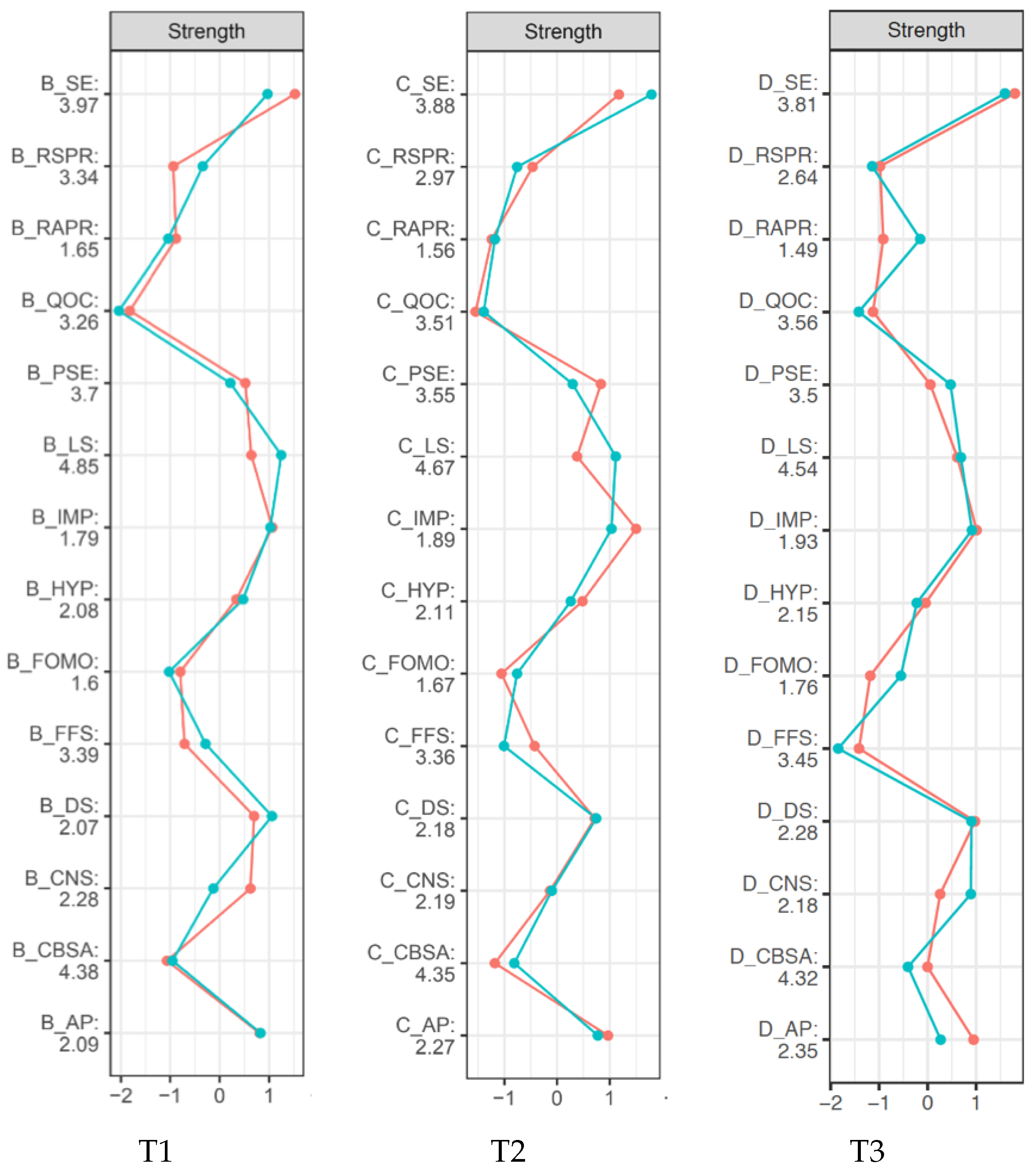

Before identifying the most influential nodes in the networks, the centrality indices’ stability –and thus reliability– was evaluated. Strength was highly stable across networks with CS-coefficients >0.67 (in most networks exceeding 0.75), indicating that dropping at least 67% of the samples would retain, with 95% probability, a strength correlation of 0.7 (default) or higher with the full samples. Consistent with previous studies (e.g., [

52,

53,

54], betweenness was instable under subsetting (CS-coefficients between 0.00–0.36). Closeness stability was sufficient to high for the normative SMU networks (CS-coefficients between 0.45–0.75) but could not be determined for T1 and T2 at-risk/problematic SMU networks (see Supplementary Material S3 for all stability analyses). Considering these results and earlier debates on the interpretation of betweenness and closeness in psychological networks (e.g., [

53]), we focus our analysis of central nodes solely on strength.

Figure 2 presents standardized strength values for normative SMU (red) and at-risk/problematic SMU (blue) networks at each time point. Self-esteem, attention problems, impulsivity, and depressive symptoms consistently appeared as the most central nodes in the normative SMU networks, with the highest sum of absolute edge weights connected to these nodes. In the at-risk/problematic SMU networks, self-esteem, impulsivity, life satisfaction (particularly at T1 and T2), and depressive symptoms (particularly at T1 and T3) were the most central factors.

5. Discussion

5.1. General findings

Problematic social media use has been associated with various adverse outcomes. It is therefore critical to identify youths at increased risk for developing PSMU, as well as factors to target in prevention and intervention efforts. This study, to our knowledge, is the first to combine two analytical approaches to examine key factors distinguishing at-risk/problematic social media users from normative users: theory-driven logistic regression analysis to assess the relative contribution of personal, peer, and parent factors in predicting the likelihood of adolescents engaging in at-risk/problematic SMU, and data-driven psychological network analysis to explore the structure of relationships between potential risk and protective factors that drive PSMU. Overall, our findings demonstrate that these two approaches emphasize different factors involved in the emergence of at-risk/problematic SMU among adolescents, illuminating how psychological network analyses can provide unique insights into complex social phenomena beyond those offered by conventional regression modeling techniques. In what follows, we discuss these findings and their implications.

Logistic regression analyses revealed that FoMO, impulsivity, depressive symptoms, intensity of meeting with friends, and reactive parental rules explained unique variance in at-risk/problematic SMU across multiple waves. Holding other variables constant, higher scores on these factors increased the likelihood of adolescents being at-risk/problematic social media users. FoMO and reactive parental rules consistently showed the strongest associations with at-risk/problematic SMU. These findings align with previous studies and theoretical frameworks suggesting that adolescents with psychological vulnerabilities are prone to developing PSMU, either as a maladaptive coping mechanism for negative emotions and/or due to reduced ability to resist social media urges [

6,

31]. Furthermore, the finding that reactive parental rule-setting was associated with increased odds of at-risk/problematic SMU corresponds with previous research describing differential effects of restrictive and reactive parental mediation on adolescents’ SMU [

33,

34]. It has been suggested that ad-hoc restrictive intervening reflects more inconsistent parenting, and that the resulting unpredictability of reactive measures may exacerbate symptoms of PSMU (e.g., tolerance, withdrawal, conflict; [

33,

55]). Moreover, reactive parental rule-setting may result from, rather than lead to, at-risk/problematic SMU, suggesting parents impose restrictions when their child shows PSMU tendencies (e.g., problems, displacement). Since the cross-sectional design of this study prohibits drawing conclusions about the direction of effects, future research should investigate whether reactive parental rule-setting has (short-term effects) on PSMU or vice versa.

Our findings challenge the social compensation hypothesis, which suggests that adolescents engage in PSMU to compensate for insufficient face-to-face interactions or poor social skills [

32,

56]. Perceived social competence did not explain unique variance in at-risk/problematic SMU in this study, and meeting with friends more frequently increased, rather than decreased, the odds of being an at-risk/problematic user. This finding is consistent with a recent study of American college students, which found that increased social activity was positively related to symptoms of Snapchat addiction (but not Facebook and Instagram addiction) and that communicating with friends was the primary motivation for using various social media platforms, implying that SMU intensifies rather than replaces face-to-face interactions [

57]. However, this study assessed SMU addiction on a continuum, and participants reported low average addiction scores for each social media platform. In the current study, most adolescents who classified as at-risk/problematic users also reported few PSMU symptoms. Hence, it is possible that the social compensation hypothesis holds among problematic users but not at-risk users.

Psychological network analyses revealed a relatively stable overall structure of personal, peer, and parent factors both over time and between normative and at-risk/problematic SMU groups. Across all networks, two clusters of tightly connected personal variables –one with ADHD symptoms and another involving mental well-being and personality factors– were observed, which were linked via bridge pathways between attention problems and depressive symptoms, and between impulsivity and narcissism. These findings align with recognized comorbidity between ADHD and depression [

58], and between narcissism and impulsivity [

59]. Self-esteem, attention problems, impulsivity, depressive symptoms, and life satisfaction emerged as the most central factors in the networks based on strength centrality indices.

The finding that factors from the two personal clusters were connected and most influential in the networks aligns with the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model of specific Internet-use disorders [

60]. According to this model, PSMU develops as a result of interactions between predisposing variables (such as personality and psychopathology) and response variables (including cognitive and attention biases, coping styles, and reduced inhibitory control) that act as mediators and moderators between predisposing variables and PSMU. Moreover, due to conditioning processes, these associations are believed to strengthen during the addiction process. The I-PACE model may also explain why the network structures of normative and at-risk/problematic social media users were largely similar: instead of forming entirely distinct networks, elevated levels of predisposing and response variables in at-risk/problematic users, along with significant associations between these factors, could potentially trigger network activation and initiate causal risk mechanisms for this group. Future studies with larger sample sizes and longitudinal data should further explore these potential mechanisms. Our study did not find evidence for conditioning processes (i.e., stronger associations or interconnectedness among factors) in the networks of at-risk/problematic users compared to normative users (although differences in edge weights’ strength were not tested); however, this could be because at-risk and problematic social media users were grouped together. As only <2% of adolescents met criteria for problematic SMU, differences in interconnectedness, if any, were likely obscured.

5.2. Logistic Regression vs. Psychological Network Analysis

Although results of the logistic regression and psychological network analysis cannot be directly compared because they serve different purposes, the two analytical approaches reveal some intriguing distinctions that merit further consideration (see

Table 3). First, FoMO was one of the most consistent risk factors of at-risk/problematic SMU in the logistic regression analyses; however, it seemed more peripheral in the network structures. Indeed, most significant bivariate associations between FoMO and other PSMU correlates were not direct links in the network, but connected through depressive symptoms (and then life satisfaction).

This finding underscores an important contribution of psychological network analysis beyond logistic regression analysis: by offering a structured method to evaluate relationships among variables, it facilitates the identification of potential mediating processes and conditional probabilities. Compared to other factors that have been theoretically linked to PSMU because of their relevance in other behavioral addictions (e.g., low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, impulsivity), FoMO has been introduced as a factor unique to social media engagement to explain why certain individuals may be especially drawn to social media [

27].

Some studies have suggested that, besides acting as an independent predictor, FoMO may mediate relationships between certain personality traits or predisposing psychopathology and PSMU [

22,

27]. Additionally, FoMO was found to be negatively associated with life satisfaction [

26]. The current study’s psychological network analysis findings reinforce the notion that FoMO needs to be considered in the context of other psychological mechanisms and predisposing psychopathology, possibly as a response category variable in the I-PACE model.

Second, reactive parental rule-setting was a consistent risk factor for at-risk/problematic SMU in logistic regression analyses and positively associated with other personal, peer, and parent factors in bivariate correlations. However, it was not linked to other risk and protective factors in the networks (i.e., no stable edges other than with restrictive parental rules). This finding could imply that reactive parental rule-setting does not share PSMU variance with other factors. Indeed, in graphical models, unconnected nodes are conditionally independent given other nodes in the network. As previously stated, reactive rule-setting may be a parental response to PSMU tendencies in children, rather than a risk factor for the development of at-risk/problematic SMU. Thus, while reactive parental rule-setting may be part of a PSMU risk profile, it may not be part of the causal pathways leading to PSMU. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that reactive parental rules are connected to other parts of the network through unincluded third variables. For instance, general parenting practices, including warmth, support, supervision, rules, and autonomy granting, are crucial for meeting essential psychological needs and fostering an optimal pedagogical environment for healthy development [

28]. Parenting styles characterized by low levels of these core dimensions have been associated with a wide range of adverse outcomes, including PSMU (e.g., [

33]). Hence, the general parenting context may connect SMU-specific parenting practices with risk and protective factors for PSMU in other domains.

Third, self-esteem, life satisfaction, and attention problems appeared among the most central factors in the network analyses; however, unlike depressive symptoms and impulsivity, they did not significantly predict at-risk/problematic SMU in the logistic regression analyses. The absence of significant associations in the logistic regression analyses might stem from the substantial variance shared among these factors (depressive symptoms and self-esteem, r=.40; depressive symptoms and life satisfaction, r=.50; and impulsivity and attention problems, r=.60), constraining our capacity to estimate the isolated effect of each risk and protective factor on at-risk/problematic SMU. This methodological ‘limitation’ of logistic regression analyses could have important implications for prevention and intervention decisions. Research suggests that high centrality nodes are vital in the etiology and maintenance of psychopathology networks, and that prioritizing these nodes in prevention and intervention efforts might be more effective and efficient in reducing network activation than targeting peripheral nodes [

39,

52]. Consequently, if self-esteem, life satisfaction, and attention problems are causally linked with multiple other PSMU risk and protective factors, alterations in these domains could trigger changes in a substantial portion of the network. Efforts aimed at mitigating attention problems, for instance, might reduce activation of depressive symptoms, which in turn could reduce activation of FoMO and increase life satisfaction and related protective factors (i.e., self-esteem, physical self-esteem), leading to further reductions in depressive symptoms and FoMO, ultimately deactivating significant portions of the PSMU network. Although our network analyses are exploratory, and our cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, future studies could further investigate and validate these potential causal pathways.

Together, our findings suggest that theory-driven and data-driven approaches to studying PSMU and other social phenomena can offer distinct insights that have important implications for theory and practice. From a scientific perspective, psychological network analysis provides a valuable tool for investigating adolescent PSMU as the emergent phenomenon from a complex system of causally interacting cognitions, traits, emotional states, behaviors, and contextual factors. It allows insight into the structural organization of this system and the relative importance of each variable in it that more conventional statistical approaches within the social sciences cannot provide.

Unlike regression models, network models do not require a priori assumptions about unidirectional causal relations. Additionally, although both approaches in the current study used the same set of personal, peer, and parent variables hypothesized to be involved in the emergence of PSMU, psychological network analysis is not constrained by the number of parameters included in the model. Hence, it is possible to explore interrelations between large sets of potential risk and protective factors in a data-driven manner and identify patterns of risk and resilience that traditional approaches to model building may have missed [

16,

17]. Considering that the logistic regression models in our study explained only 10-19% of the variance in at-risk/problematic SMU, psychological network analysis holds promise in identifying unexplored predictors and mechanisms involved in PSMU.

Network insights can be used to generate novel hypotheses about causal processes, which can then be tested using confirmatory methods. Consequently, inductive-exploratory and confirmatory-explanatory approaches can complement one another to advance our understanding of when and which youth are at a higher risk of developing PSMU. From a clinical perspective, identifying central factors in networks of risk and protective factors can assist in early identification of at-risk users and guide targeted interventions that substantially disrupt the system as a whole. As previously noted, targeting central nodes may be more effective and efficient in reducing overall risk than targeting peripheral nodes [

52,

61].

Our results indicate that factors identified as significant predictors in multiple regression models may not necessarily be central nodes. For example, whereas FoMO appeared as the most consistent predictor of at-risk/problematic SMU in the logistic regression analysis, targeting depressive symptoms –a central and bridging factor– may affect multiple causal pathways involved in PSMU. At the same time, it should be noted that network edges were undirected and thus do not indicate whether factors were central because they had a greater influence on other nodes in the network or because they were particularly susceptible to the influence of other nodes. Furthermore, the degree to which risk and protective factors are modifiable by means of intervention may vary. Thus, it is crucial that researchers not only identify central factors but also verify their causal role and assess the effects of behavioral interventions on these factors through longitudinal and experimental studies.

6. Conclusions

Considering the widespread use of social media among adolescents and the growing body of literature describing adverse outcomes associated with compulsive or problematic SMU, it is critical to pinpoint when and which youth are at higher risk of developing PSMU and identify key factors to target in prevention and intervention. This study illustrated how theory-driven and data-driven approaches offer unique insights into this matter. Logistic regression analyses on personal, peer, and parent factors revealed that FoMO, impulsivity, depressive symptoms, intensity of meeting with friends, and reactive parental rules explained unique variance in at-risk/problematic SMU. Furthermore, psychological network analyses illuminated the structural relationships among risk and protective factors, identifying self-esteem, attention problems, impulsivity, depressive symptoms, and life satisfaction as central factors most strongly connected in the entire network.

Together, these findings point to potential causal pathways involved in the development of PSMU that warrant further investigation. Understanding the dynamic risk and resilience patterns that comprise PSMU will yield a more comprehensive profile of at-risk youth, enhance predictive accuracy, and contribute to more effective prevention and intervention.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. First, our cross-sectional design does not permit conclusions about the direction of relationships. While we utilized multiple waves of data, our study aimed not to assess longitudinal associations but to identify, employing two different data-analytical approaches, the most relevant factors in distinguishing at-risk/problematic social media users from normative users. Cross-sectional designs were better suited for this purpose. Nevertheless, our design allows generation of hypotheses regarding causal processes involved in PSMU, which can be evaluated in future longitudinal and experimental studies.

Second, although we evaluated a broad range of personal, peer, and parent factors in relation to adolescents’ at-risk/problematic SMU, predictor set was not exhaustive. For instance, the logistic regression models explained only 10-19% of the variance in at-risk/problematic SMU. Future research should investigate other factors and mechanisms that may be involved in the emergence and maintenance of PSMU. In this regard, data-driven approaches such as psychological network analysis could help identify risk and resilience patterns that have not yet been explored.

Third, the prevalence of problematic SMU in our sample was low (<2%). To retain power, we grouped at-risk and problematic social media users together. Although previous research among a representative Dutch sample found that at-risk users were more likely than normative users to experience adverse consequences due to their SMU [

31], the inclusion of less extreme cases may have resulted in weaker associations and/or different network structures for the at-risk/problematic group compared to when problematic users would have been singled out.

Finally, due to classes and schools entering and exiting the study over time, there was a considerable amount of missing data on the study variables. To enhance statistical power and mitigate potential bias, we imputed missing values using multiple imputation; nevertheless, the psychological networks were estimated based on only one of the imputed sets. Different network structures might have emerged if alternative sets had been used. That being said, we evaluated the stability of edge weights and centrality indices using bootstrap techniques and only interpreted results meeting both accuracy and reliability criteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R. vd. E.; methodology, V.H. and S.V.; software, V.H. and S.V.; validation, I.K., A.A.S. and R. vd. E.; formal analysis, V.H.; data curation, R. vd. E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D. and A.A.S.; writing—review and editing, S.D., V.H., I.K., A.A.S. and R. vd. E.; supervision, A.A.S. and R. vd. E.; funding acquisition, A.A.S. and R. vd. E. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a Dynamics of Youth Invigoration Grant from Utrecht University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the board of ethics of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Utrecht University (FETC16-076 Eijnden).

Informed Consent Statement

Data were collected through online self-report questionnaires administered in the classroom setting using Qualtrics survey software. Trained research assistants were present to supervise data collection, answer questions, and ensure respondents’ privacy. Prior to the survey assessment, parents were provided information about the study and the opportunity to decline their child’s participation. Adolescents with passive informed parental consent were informed about the purpose of the study, that participation was voluntary and anonymous, and that they could withdraw their participation at any time.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available online, because the data are part of an ongoing study, and access requires ethical screening procedures. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADHD |

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| CS |

Correlation-stability |

| EBIC |

Extended Bayesian Information Criterion |

| I-PACE |

Interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution |

| FoMO |

Fear of missing out |

| LASSO |

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| M |

Mean |

| MI |

Multiple imputation |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| PSMU |

Problematic social media use |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| SEM-NN |

Structural equation modeling neural network |

| SMDS |

Social Media Disorder Scale |

| SMU |

Social media use |

References

- Boer, M.; Van Dorsselaer, S.; De Looze, M.E.; De Roos, S.; Brons, H.; Van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Monshouwer, K.; Huijnk, W.; Ter Bogt, T.F.M.; Vollebergh, W.A.M.; et al. HBSC 2021. Gezondheid en welzijn van jongeren in Nederland, 2022.

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Budisavljevic, S.; Torsheim, T.; Jåstad, A.; Cosma, A.; Kelly, C.; Arnarsson, Á.; Samdal, O. Spotlight on adolescent health and wellbeing. Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey in Europe and Canada. International report: Key data (Volume 2); WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2020.

- Vogels, E.A.; Gelles-Watnick, R.; Massarat, N. Teens, social media and technology; Pew Research Center, 2022.

- Andreassen, C.S. Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive review. Current Addiction Reports 2015, 2, 175–184. [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [CrossRef]

- Marino, C.; Gini, G.; Vieno, A.; Spada, M.M. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2018, 226, 274–281. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.W.J.; Ho, S.S.; Lwin, M.O. Explicating problematic social network sites use: A review of concepts, theoretical frameworks, and future directions for communication theorizing. New Media and Society 2017, 19, 308–326. [CrossRef]

- Boer, M.; Van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Wong, S.L.; Inchley, J.C.; Badura, P.; Craig, W.M.; Gobina, I.; Kleszczewska, D.; Klanšček, H.J.; et al. Adolescents’ intense and problematic social media use and their well-being in 29 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health 2020, 66, S89–S99. [CrossRef]

- Van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Koning, I.M.; Doornwaard, S.M.; Van Gurp, F.; Ter Bogt, T.F.M. The impact of heavy and disordered use of games and social media on adolescents’ psychological, social, and school functioning. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2018, 7, 697–706. [CrossRef]

- Boer, M.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Finkenauer, C.; Van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder-symptoms, social media use intensity, and social media use problems in adolescents: Investigating directionality. Child Development 2020, 91, e853–865. [CrossRef]

- Mérelle, S.; Kleiboer, A.; Schotanus, M.; Cluitmans, T.; Waardenburg, C. Which health-related problems are associated with problematic video-gaming or social media use in adolescents? A large-scale cross-sectional study. Clinical Neuropsychiatry 2017, 14, 11–19.

- Alonzo, R.; Hussain, J.; Stranges, S.; Anderson, K. Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2020, 56, 101414. [CrossRef]

- Šablatúrová, N.; Rečka, K.; Blinka, L. Validation of the Social Media Disorder Scale using network analysis in a large representative sample of Czech adolescents. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 907522. [CrossRef]

- Domoff, S.E.; Foley, R.P.; Ferkel, R. Addictive phone use and academic performance in adolescents. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2020, 2, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Di Franco, G.; Santurro, M. Machine learning, artificial neural networks and social research. Quality & Quantity 2021, 55, 1007–1025. [CrossRef]

- Hofman, J.M.; Watts, D.J.; Athey, S.; Garip, F.; Griffiths, T.L.; Kleinberg, J.; Margetts, H.; Mullainathan, S.; Salganik, M.J.; Vazire, S.; et al. Integrating explanation and prediction in computational social science. Nature 2021, 595, 181–188. [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G. To Explain or to Predict? Statistical Science 2010, 25. [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological systems theory. Annals of Child Development 1989, 6, 187–249.

- Lee, S.S.; Humphreys, K.L.; Flory, K.; Liu, R.; Glass, K. Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review 2011, 31, 328–341. [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Billieux, J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Mazzoni, E.; Pallesen, S. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2016, 30, 252–262. [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S.; Griffiths, M.D. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors 2017, 64, 287–293. [CrossRef]

- Oberst, U.; Wegmann, E.; Stodt, B.; Brand, M.; Chamarro, A. Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: The mediating role of fear of missing out. Journal of Adolescence 2017, 55, 51–60. [CrossRef]

- Vejmelka, L.; Matković, R. Online interactions and problematic internet use of croatian students during the covid-19 pandemic. Information 2021, 12, 399.

- Elhai, J.D.; Yang, H.; Fang, J.; Bai, X.; Hall, B.J. Depression and anxiety symptoms are related to problematic smartphone use severity in Chinese young adults: Fear of missing out as a mediator. Addictive Behaviors 2020, 101, 105962. [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Banchi, V. Narcissism and problematic social media use: A systematic literature review. Addictive Behaviors Reports 2020, 11, 100252. [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; Dehaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, G.; Casale, S.; Benucci, S.B.; Prostamo, A.; Falone, A.; Ricca, V.; Rotella, F. Fear of missing out and social networking sites use and abuse: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 122, 106839. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist 2000, 55, 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Sameroff, A. The transactional model. In The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other; Sameroff, A., Ed.; American Psychological Association, 2009; pp. 3–21.

- Nielsen, P.; Favez, N.; Rigter, H. Parental and family factors associated with problematic gaming and problematic internet use in adolescents: A systematic literature review. Current Addiction Reports 2020, 7, 365–386. [CrossRef]

- Boer, M.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Finkenauer, C.; Koning, I.M.; Van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M. Validation of the Social Media Disorder Scale in adolescents: Findings from a large-scale nationally representative sample. Assessment 2022, 29, 1658–1675. [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S.E. Preference for online social interaction: A theory of problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being. Communication Research 2003, 30, 625–648. [CrossRef]

- Geurts, S.M.; Koning, I.M.; Vossen, H.G.M.; van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M. Rules, role models or overall climate at home? Relative associations of different family aspects with adolescents’ problematic social media use. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2022, 116, 152318. [CrossRef]

- Koning, I.M.; Peeters, M.; Finkenauer, C.; Van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M. Bidirectional effects of internet-specific parenting practices and compulsive social media and internet game use. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2018, 7, 624–632. [CrossRef]

- Van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Geurts, S.M.; Ter Bogt, T.F.M.; Van der Rijst, V.G.; Koning, I.M. Social media use and adolescents’ sleep: A longitudinal study on the protective role of parental rules regarding Internet use before sleep. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 1346. [CrossRef]

- Lakić, N.; Bernik, A.; C̆ep, A. Addiction and Spending in Gacha Games. Information 2023, 14, 399.

- Borsboom, D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 5–13. [CrossRef]

- Borsboom, D.; Cramer, A.O.J.; Kalis, A. Brain disorders? Not really: Why network structures block reductionism in psychopathology research. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2019, 42, 1–63. [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavioral Research Methods 2018, 50, 195–212. [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I. A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods 2018, 23, 617–634. [CrossRef]

- Baggio, S.; Starcevic, V.; Studer, J.; Simon, O.; Gainsbury, S.M.; Gmel, G.; Billieux, J. Technology-mediated addictive behaviors constitute a spectrum of related yet distinct conditions: A network perspective. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2018, 32, 564–572. [CrossRef]

- Faelens, F.; Hoorelbeke, K.; Fried, E.; De Raedt, R.; Koster, E.H.W. Negative influences of Facebook use through the lens of network analysis. Computers in Human Behavior 2019, 96, 13–22. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Niu, Z.; Mei, S.; Griffiths, M.D. A network analysis approach to the relationship between fear of missing out (FoMO), smartphone addiction, and social networking site use among a sample of Chinese university students. Computers in Human Behavior 2022, 128, 107086. [CrossRef]

- Esfahlani, F.Z.; Visser, K.; Strauss, G.P.; Sayama, H. A network-based classification framework for predicting treatment response of schizophrenia patients. Expert Systems with Applications 2018, 109, 152–161.

- Van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Lemmens, J.S.; Valkenburg, P.M. The Social Media Disorder Scale: Validity and psychometric properties. Computers in Human Behavior 2016, 61, 478–487. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.); 2013. [CrossRef]

- Manly, C.A.; Wells, R.S. Reporting the use of multiple imputation for missing data in higher education research. Research in Higher Education 2015, 56, 397–409. [CrossRef]

- Van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C.G.M. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software 2011, 45. [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, S.L. Graphical models; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1996.

- Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Glasso: Graphical Lasso: Estimation of Gaussian Graphical Models. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=glasso, 2019.

- Epskamp, S.; Cramer, A.O.; Waldorp, L.J.; Schmittmann, V.D.; Borsboom, D. qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software 2012, 48, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Beard, C.; Millner, A.J.; Forgeard, M.J.; Fried, E.I.; Hsu, K.J.; Treadway, M.T.; Leonard, C.V.; Kertz, S.J.; Björgvinsson, T. Network analysis of depression and anxiety symptom relationships in a psychiatric sample. Psychological Medicine 2016, 46, 3359–3369. [CrossRef]

- Bringmann, L.F.; Elmer, T.; Epskamp, S.; Krause, R.W.; Schoch, D.; Wichers, M.; Wigman, J.T.W.; Snippe, E. What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2019, 128, 892–903. [CrossRef]

- Forrest, L.N.; Jones, P.J.; Ortiz, S.N.; Smith, A.R. Core psychopathology in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A network analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2018, 51, 668–679. [CrossRef]

- Van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Spijkerman, R.; Vermulst, A.A.; Van Rooij, T.J.; Engels, R.C. Compulsive Internet use among adolescents: Bidirectional parent–child relationships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2010, 38, 77–89. [CrossRef]

- Boer, M.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Finkenauer, C.; De Looze, M.E.; Van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M. Social media use intensity, social media use problems, and mental health among adolescents: Investigating directionality and mediating processes. Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 116, 106645. [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.; Antony, M.G.; Sykes, B. Predictors of problematic social media use: Personality and life-position indicators. Psychological Reports 2021, 124, 1110–1133. [CrossRef]

- Oddo, L.E.; Felton, J.W.; Meinzer, M.C.; Mazursky-Horowitz, H.; Lejuez, C.W.; Chronis-Tuscano, A. Trajectories of depressive symptoms in adolescence: The interplay of maternal emotion regulation difficulties and youth ADHD symptomatology. Journal of Attention Disorders 2021, 25, 954–964. [CrossRef]

- Vazire, S.; Funder, D.C. Impulsivity and the self-defeating behavior of narcissists. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2006, 10, 154–165. [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Young, K.S.; Laier, C.; Wölfling, K.; Potenza, M.N. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 2016, 71, 252–266. [CrossRef]

- Robinaugh, D.J.; Millner, A.J.; McNally, R.J. Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2016, 125, 747–757. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).