1. Introduction

In recent years, attempts to utilize natural polymers for biomedical applications, including drug delivery, wound dressings, and tissue engineering scaffolds, have notably increased [

1,

2]. Scientists and industrialists foresee that such attempts could yield environmentally friendly products that are renewable and sustainable. Among various natural polymers, cellulose has garnered significant attention in the biomedical field owing to its biocompatibility, structural tunability, and natural abundance, rendering it ideal for applications such as drug delivery, wound dressing, and tissue engineering (

Figure 1a).

The advent of nanotechnology suggests new means for cellulose utilization, particularly in the form of nanocellulose. Nanocellulose, encompassing both cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) and cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs), has garnered substantial attention from academic and industrial researchers owing to its versatile properties and extensive applications [

3,

4]. CNFs, occasionally designated as nanofibrillated cellulose or microfibrillated cellulose, are malleable, elongated fibrils with lengths exceeding 1 μm and a cross-section of approximately 5 nm. Typically, CNFs are produced by the high-energy mechanical homogenization of wood pulp, often in conjunction with enzymatic treatment [

5], 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO) oxidation [

6], or other chemical modifications [

7] to enhance colloidal stability and reduce the energy input required for fibrillation.

The distinctive structural and physicochemical characteristics of CNFs render them particularly well-suited for biomedical applications. CNFs exhibit exceptional physical and chemical properties, including high tensile strength and modulus (in the range of 130–150 GPa), a large specific surface area (up to several hundred meter square per gram), low density (1.6 g/cm³), reactive surface chemistry, and intrinsic biodegradability and renewability [

8]. These attributes, in conjunction with a high aspect ratio and partially crystalline nature, enable CNFs to form robust networks at low concentrations (< 1 wt%) [

9]. Interestingly, the usability of CNFs can be extended further when combined with a hydrogel system. Hydrogels represent a class of soft materials formed by three-dimensional networks of cross-linked polymer chains that can hold large volumes of water (up to 99.9%). The combination of CNFs with hydrogels yields an innovative biomaterial that synergizes the inherent properties of CNFs with the advantages of hydrogels.

CNF hydrogels have attracted considerable attention owing to their superior biocompatibility and biodegradability, rendering them suitable for safe application in biomedical and tissue engineering [

10,

11]. The versatility of CNF hydrogels permits their adaptation to specific biomedical applications, each of which has a unique set of requirements (

Figure 1b). For example, cell and organoid cultures necessitate a malleable three-dimensional mechanical support coated with adhesion proteins that exhibit a sol-gel transition, thereby allowing the biological material to be manipulated at various stages [

12]. In tissue engineering applications, such as engineered cartilage and skin regeneration, CNF hydrogels can be designed to control mechanical properties, including strength, rigidity, and elongation, and facilitate processing into complex shapes [

13,

14]. Moreover, in the field of drug delivery, CNF hydrogels have the potential to safeguard therapeutic agents until the target site is reached, where the agents are released in a controlled manner [

15]. In diagnostic applications, these hydrogels can be designed to selectively retain a specific marker or biomolecule at a very low concentration and communicate the presence or concentration of this analyte [

16].

CNF-based hydrogels offer notable advantages in terms of biocompatibility, renewability, and mechanical tunability. However, the widespread application of these hydrogels in the biomedical field has been constrained by several technical and chemical limitations. In particular, conventional fabrication methods often require the use of toxic polyfunctional crosslinkers that can leave harmful residues and require time-consuming purification. These drawbacks raise concerns regarding biosafety and hinder scalable production [

17]. To address these limitations, novel crosslinking strategies that exploit the inherent functional groups of CNFs must be developed, enabling the design of safe, sustainable hydrogel systems.

This review provides comprehensive information regarding the fabrication and characterization methods used for CNF-based hydrogels and presents case studies of the use of these hydrogels in various biomedical applications, including drug delivery and tissue engineering. Furthermore, the current technical challenges and prospective research directions are examined. This review elucidates the potential of CNF hydrogels and clarifies their contribution to future biomedical research and industrial development.

2. Methods for Preparing CNF Hydrogels

2.1. Physical Crosslinking Methods

CNF hydrogels formed via physical crosslinking exhibit distinct structural and rheological characteristics, primarily owing to the anisotropic morphologies and high aspect ratios of nanocellulose fibrils. Unlike conventional polymer-based hydrogels that typically originate from molecular solutions, CNF dispersions exist as colloidal suspensions, critically influencing gelation mechanisms and viscoelastic behavior [

18,

19]. Fibrils, measuring between 5–50 nm in diameter and extending up to several microns in length, can entangle and form percolated networks via hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions, enabling stable hydrogel formation without the presence of chemical crosslinkers [

18,

20].

Figure 2a reveals that the physical crosslinking of such polymeric networks involves conjugation between polymeric chains via irreversible interactions such as hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, hydrophobic interactions, and crystalline formation.

CNF hydrogels can be cross-linked through several key approaches, and the most fundamental approach involves controlling surface charge density. At a given solid content, increasing the surface charge density of a CNF prevents agglomeration by electrostatic repulsion and promotes network entanglement. Im et al. [

21] reported that three different composite hydrogels of CNF and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) were prepared with various surface charges of CNFs (

Figure 2b,c). The group containing untreated CNFs (U-CNFs) possessed a zeta potential value of 0 mV. The hydrogels with carboxymethylated (CM-CNF) and quaternized (Q-CNF) CNFs possessed zeta potentials of −40 mV and +70 mV, respectively (

Figure 2c). Interestingly, these three hydrogels demonstrated different transmittance values, crystallinities, distributions of nanofibrils, shear viscosities, and storage moduli.

Hydrogel gelation is highly dependent on controlling pH and ionic strength. Adding salt or reducing solution pH induces gelation by reducing surface charge via counterion-driven charge screening of surface carboxyl groups. The stability of these gels strongly depends on pH and salt concentration, which directly affect the network-bound water content and overall gel structure [

23]. Fall et al. demonstrated that the degree of deprotonation and the number of charged carboxyl groups in hydrogels can be precisely controlled by varying salt concentration and pH. Moreover, CNF concentration influences hydrogel formation, and studies have shown that stable gels can form at concentrations as low as 0.125 wt% when using enzymatically treated and homogenized CNFs [

5]. This is particularly significant as it represents a concentration two orders of magnitude lower than that required for other nanocellulose materials [

24].

Furthermore, structured CNF-based hydrogels are being developed by controlling the orientation of CNFs. Håkansson et al. [

25] demonstrated that hydrodynamic forces and ionic interactions can be used to achieve fibril alignment and gelation by exposing CNFs to a focused flow. Similarly, Cai et al. [

22] fabricated aligned filaments solely consisting of CNFs via flow-assisted assembling, as illustrated in

Figure 2d. The aligned structure imparted better mechanical properties to the CNF-based hydrogel than the randomly oriented nanofibrils and improved applicability in the biomedical engineering field, such as muscle and neuronal engineering.

2.2. Chemical Crosslinking Methods

Chemically crosslinking CNFs creates strong and permanent network structures via various bonding mechanisms (

Figure 3a). Chemically crosslinked networks can be achieved via covalent bonds formed through radical polymerization, chemical reactions, irradiation, or enzymatic reactions [

26,

27,

28]. The preparation process begins with the challenging step of dissolving cellulose chains, governed by the balance between entropy and molecular interactions [

29,

30]. To commence the gelation procedure, different chemical procedures and modification protocols have been developed to dissolve cellulose in water or organic solvents [

31,

32]. For instance, aqueous solutions of NaOH/urea and LiOH/urea have been used to dissolve cellulose at temperatures as low as −10 °C [

33,

34].

The next step of fabricating CNF-based hydrogels via chemical crosslinking involves exposing CNFs to specific crosslinking agents, such as epichlorohydrin, metal ions, citric acid, and succinic anhydride [

39,

40,

41], to form the hydrogel structure. Among the available agents, metal ions are particularly effective for CNF hydrogel preparation. The hydrogelation of carboxylated cellulose fibers (produced by TEMPO oxidation) proceeds rapidly on adding di- or trivalent metal cations such as Ca²⁺, Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺, Al³⁺, and Fe³⁺ (

Figure 3b,c) [

35]. The gelation mechanism causes the cation-carboxylate interactions to screen the repulsive charges on the nanofibrils [

38]. As shown in

Figure 3c, Yang et al. [

36] demonstrated that the tensile strength and toughness of CNF hydrogels increased owing to the incorporation of multivalent metal ions, following the order Zn²⁺ < Ca²⁺ < Al³⁺ < Ce³⁺, highlighting the critical role of ionic crosslinking in modulating mechanical performance.

Composite hydrogel preparation offers another approach to enhance mechanical properties. CNFs can be used as reinforcing agents in polymer matrices; however, the loading levels of these CNFs must be carefully controlled to avoid entanglement. Such composites are more commonly prepared using synthetic polymers, such as PVA, poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG), or polyacrylamide, because such polymers are stable and malleable with excellent mechanical properties. Takeno et al. [

37] and Zhang et al. [

39] successfully fabricated a CNF/PVA hydrogel crosslinked with borax. They demonstrated that the mechanical properties of the PVA-based hydrogel improved owing to the addition of CNF and borax. In particular, Takeno et al. emphasized the effect of CNF size on gel properties. The composite gel containing the CNF with a smaller length demonstrated better stretchability than the ones with longer fiber lengths. The self-healing capability of these two reported composite hydrogels was another significant feature. As shown in

Figure 3e, the CNF/PVA hydrogel cut in half was healed in 5 min of physical contact.

The self-healing capacity of these composite CNF/PVA hydrogels reveals that chemical crosslinking can impart various interesting functionalities to the system. For example, ultraviolet radical polymerization has been used to prepare hydrogels from bacterial nanocellulose and poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate). These composite hydrogels exhibit significantly improved tensile strengths and Young’s moduli with respect to single-component systems [

40]. Moreover, temperature-responsive properties can be incorporated via specific chemical modifications. Specifically, PNIPAm-based CNF hydrogels have demonstrated characteristic temperature-dependent swelling behavior. Therefore, the mechanical properties of these thermoresponsive systems can be tuned by controlling the CNF content [

41,

42].

3. Biomedical Applications of CNF Hydrogels

3.1. Drug Delivery Systems

Drug delivery systems represent bioengineered technologies designed for the targeted transport of therapeutic agents to specific tissues and organs. These systems incorporate carrier vessels and coating treatments to control the release of medicines and biomolecules [

43]. Such modifications enhance pharmacokinetics and optimize the biodistribution of substances in the human body. The development of effective drug delivery systems requires careful consideration of stability factors, including pH, ionic strength, and temperature variations before reaching the target site, to prevent premature release and ensure controlled release [

44]. CNF-based hydrogels have emerged as promising carriers for bioactive molecules owing to their unique advantages involving nanostructures, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and tunable surface chemistry [

45,

46,

47]. These hydrogels demonstrate excellent bioavailability and drug loading capacity, attributable to their open pore structure and large surface area [

48].

The development of stimuli-responsive CNF hydrogels has garnered particular attention due to their ability to release drugs on-demand in response to specific stimuli such as pH, temperature, and ionic strength. Masruchin et al. [

49] synthesized dual-responsive composite hydrogels based on TEMPO-oxidized CNFs and thermally responsive Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) for drug delivery. These hydrogels responded to both pH and temperature. The pH sensitivity of these hydrogels originates from the tunable ionization of the carboxyl groups on CNFs, whereas temperature responsiveness is imparted by PNIPAM, enabling control over swelling behavior via external thermal input (

Figure 4a). In another significant development, Zhang et al. [

50] fabricated pH-responsive gel macrospheres using sodium alginate (SA) and TEMPO-oxidized CNFs, exhibiting remarkable stability in simulated gastric fluid while enabling controlled release under intestinal conditions. The stability of these macrospheres in simulated gastric fluid ensured excellent protection of encapsulated probiotics in an acidic environment, and these macrospheres swell in simulated intestinal fluid for controlled release.

Liu et al. [

51] further enhanced the CNF hydrogel-based drug delivery system by combining mesoporous polydopamine (MPDA), graphene oxide (GO), and CNF to prepare an MDPA@GO/CNF composite hydrogel to demonstrate efficient and safe delivery of tetracycline hydrochloride (TH) with improved sustainability. MPDA loaded with TH were wrapped in GO sheets that were eventually incorporated within the CNF-based hydrogel (

Figure 4b, left). As the GO sheets protected the burst release of TH from the MPDA particles, the drugs were released sustainably. Moreover, the hydrogen bonds and π- π stacking formed between the GO sheets and the released TH further delayed the drug release, increasing the overall efficiency of drug delivery. The biocompatible protection of the MPDA@GO/CNF composite hydrogel exhibited controlled drug release via the regulation of environmental pH and near-infrared irradiation (

Figure 4b, right).

Research has been conducted on using injectable CNF hydrogels to further enhance in vivo drug delivery applications. Lauren et al. [

53] demonstrated that technetium-99m-labeled CNF hydrogels allow the tracking and monitoring of hydrogel localization and evaluation of drug delivery in vivo as a function of time. These biocompatible and non-toxic CNF hydrogels were disintegrated into glucose by locally administering cellulose metabolizing enzymes, enabling an additional level of control over the delivery system. This characteristic renders these hydrogels particularly suitable for applications requiring precise control throughout drug delivery.

The practical aspects of CNF hydrogels used for drug delivery have been extensively investigated. Research has shown that freeze-drying and subsequent rehydration do not affect the drug release properties of re-dispersed CNF hydrogels [

54]. This finding has significant implications for storage and handling, as these hydrogels can be stored in a dry form and only re-dispersed when needed, thus benefiting real clinical applications. Recent studies have also explored the development of highly complex drug delivery systems. For instance, composite hydrogels incorporating multiple functional components have been developed to achieve sequential drug release patterns, as demonstrated by Lin et al. [

55] (

Figure 4c) using a double-membrane hydrogel system. Single-membrane microspheres were first fabricated by mixing SA with CNC for crosslinking with Ca ions to obtain a double-membrane structure by forming an additional outer layer of the crosslinked alginate. The ability to control the release of multiple therapeutic agents in a predetermined sequence represents a significant advancement in drug delivery technology.

Despite these advances, several challenges remain in the development of CNF-based drug delivery systems. A key area for development is the formation of hydrogel systems for simultaneously releasing different drugs at varying rates, particularly advantageous for multidrug treatments for diseases such as cancer [

56]. CNF functionalization must be further optimized for efficient responsiveness to specific conditions to advance the development of smart materials for drug delivery systems. Additionally, the scaling up of production processes while maintaining consistent quality and performance remains a significant challenge.

3.2. Tissue Engineering

In recent years, CNF-based hydrogels have garnered considerable attention in tissue engineering applications [

57,

58] owing to their highly hydrated three-dimensional porous structure that mimics biological tissue [

59]. These biomaterials possess unique advantages in terms of biocompatibility, mechanical strength, and structural similarity to the natural extracellular matrix. The fundamental requirements for tissue engineering scaffolds include the ability to promote nutritional transport, vascularization through their porous gel structure [

60,

61,

62], and natural degradation in body fluids to prevent surgical removal [

61]. The scaffold must afford excellent mechanical properties to sustain cell proliferation and support differentiation into specialized, structured tissues. The high concentration of hydroxyl groups in CNF ensures the presence of a hydrated layer, beneficial for tissue regeneration and cell attachment.

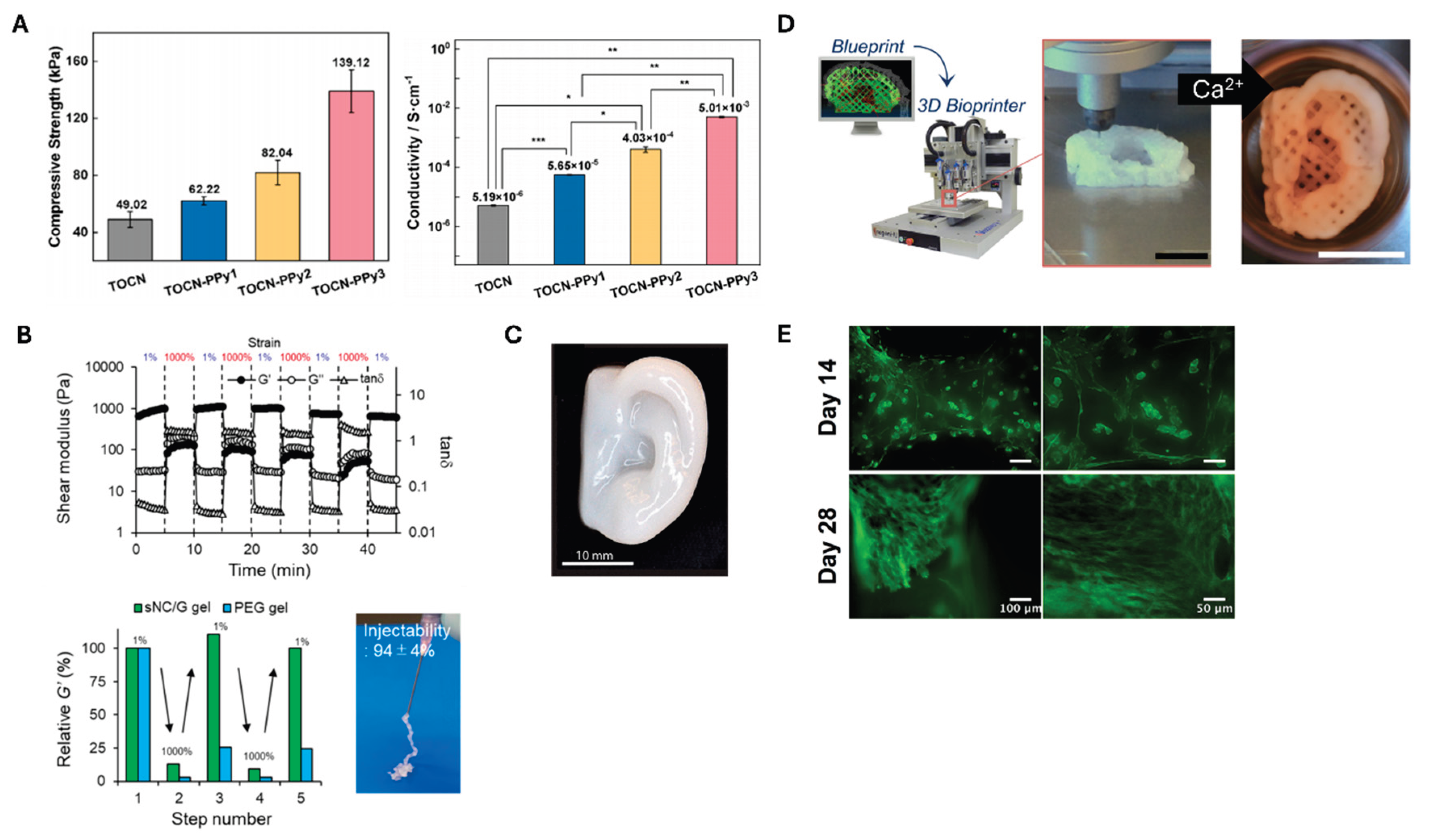

Hou et al. [

63] prepared a conductive nanocellulose-based hydrogel system by polymerizing TEMPO-oxidized CNF (TOCN) with polypyrrole (PPy). Cellulose can be crosslinked to a hydrogel by adding Fe ions after being oxidized with TEMPO. The resulting TOCN can subsequently be polymerized with PPy to yield a conductive hydrogel, which can be used as scaffolds for myocardial tissue regeneration.

Figure 5a reveals that TOCN alone exhibited reasonable strength of 49.2 kPa; however, the hydrogel strength increased to 62.22 kPa. This value further increased to 82.04 and 139.12 kPa after repeating the PPy polymerization step once and twice, respectively. In addition, the stepwise polymerization of PPy gradually increased the conductivity of the composite hydrogel (

Figure 5a).

Injectable CNF-based hydrogels are particularly promising owing to their minimally invasive application and ability to conform to irregular defect shapes [

67]. These hydrogels can be designed to maintain moisture and pH over time [

68], crucial for tissue regeneration. The ability to deliver cells and bioactive molecules directly to the target site while maintaining their viability makes injectable CNF hydrogels particularly valuable for tissue engineering applications. As displayed in

Figure 5b, Nishiguchi et al. [

64] demonstrated the thixotropic property of the CNF-based injectable hydrogels by showing the reversible changes in shear modulus along with the alternating strain between 1% and 1000%. This reversibility is evident when compared with the non-injectable PEG gel. Doench et al. [

69] demonstrated that injectable CNF-filled chitosan formulations can be successfully used for intervertebral disc tissue engineering. When tested in pig models, these formulations demonstrated successful intradiscal injection and in situ gelation, effectively restoring the viscoelastic properties of the discs and increasing disc height.

A significant breakthrough in CNF applications has been the development of 3D bioprinting techniques [

70,

71,

72]. This technology has revolutionized the production of highly structured tissue engineering scaffolds, allowing precise control over scaffold architecture. The ability to dispense hydrogels in three dimensions with precision and increasing resolution has opened new possibilities for preparing complex tissue structures. Markstedt et al. [

65] developed a bioink composed of CNF (80%) and alginate (20%) with exceptional shear-thinning properties and rapid cross-linking ability. This formulation, known as Ink8020, demonstrated minimal shape deformation and maintained good cell viability, with human chondrocytes showing 73% and 86% viability after 1 and 7 days of 3D culture, respectively. Moreover, as shown in

Figure 5c, Ink8020 can print from small grids to ear-like forms. Avila et al. [

66] further advanced auricular cartilage tissue engineering using a similar CNF-alginate bioink, as shown in

Figure 5d. Patient-specific auricular constructs maintained excellent shape and size stabilities during 28 days of culture (

Figure 5e). The study demonstrated the successful proliferation of human nasal chondrocytes and chondrogenesis, enabling the synthesis and accumulation of a cartilage-specific extracellular matrix. This achievement represents a significant step toward forming functional tissue replacements using CNF-based materials.

The combination of precise 3D printing capabilities [

73,

74] with the inherent biocompatibility of CNF hydrogels offers promising opportunities for creating highly sophisticated tissue engineering solutions. Recent advances in surface modification and functionalization techniques have expanded the potential applications of CNF hydrogels in tissue engineering. The ability to control structural parameters and incorporate bioactive molecules renders CNF hydrogels particularly versatile for various tissue engineering applications, as demonstrated in recent studies [

75,

76].

4. Summary and Outlook

Over the past decades, biomedical materials have advanced substantially in terms of CNF hydrogel research and development. These advanced materials possess intricate three-dimensional networks that can retain substantial amounts of water while maintaining robust structural integrity. This unique combination of properties has established CNF hydrogels as promising candidates across multiple biomedical domains, including cellular research, regenerative medicine, and therapeutic delivery systems.

Current research has revealed several areas that require further investigation before the widespread implementation of these hydrogels becomes feasible. In cellular applications, a major concern centers on the methodology used for hydrogel dissolution post-culture. Recent studies rely heavily on enzymatic breakdown processes; however, insufficient research exists on the extended impact of these enzymes on cellular health and function. The scope of cellular research using CNF hydrogels has remained relatively narrow, focusing predominantly on specific cell lines while leaving vast areas of potential applications, such as complex human organ culture systems, largely unexplored. The field of regenerative medicine presents additional limitations, particularly in terms of optimizing bioprinting processes. Current evidence suggests that pure CNF systems rarely achieve optimal printing outcomes without requiring supplementary biomaterials to be incorporated. Additionally, applications in wound management typically require antimicrobial agents to be integrated to achieve the desired therapeutic outcomes.

Initial medical trials have generated encouraging results in terms of biocompatibility. Notable research involving burn treatment applications yielded favorable safety profiles with the minimal occurrence of adverse reactions, i.e., clinical trials [

77] showed no allergic reaction or inflammatory response to CNF wound dressings. These preliminary findings, though promising, highlight the critical need for further comprehensive safety evaluations. The toxicology assessment and long-term evaluation of in vivo toxicity and biocompatibility of CNF-based hydrogels remain a crucial issue for real clinical applications [

78]. The development of standardized assessment protocols remains essential for advancing medical implementation.

The transition to commercial-scale production introduces additional complexities. A critical challenge involves understanding and controlling material variability owing to different source materials and processing methods. Although some studies have investigated the effects of aspect ratio, surface charge, and fabrication conditions on CNF properties [

79,

80,81], maintaining consistent quality under high production volumes remains challenging. Advanced manufacturing technologies, particularly in the realm of precision printing, show promise in terms of addressing some of these challenges by forming precisely controlled structures. However, these processes need to be optimized for large-scale implementation, and therapeutic delivery systems could benefit significantly from the adaptable nature of CNF hydrogels, particularly for developing responsive release mechanisms. The potential for enhancing diagnostic capabilities through the precise control of surface chemistry represents another promising avenue for investigation. Additionally, the development of comprehensive testing standards will be crucial for regulatory compliance across various applications.

Moreover, technological advancements in processing methods are promising. Recent innovations in manufacturing techniques have demonstrated potential for generating sophisticated structural arrangements while maintaining material integrity. These developments could yield efficient production methods while enabling excellent control over final product characteristics. Integration with existing medical technologies represents another critical area for development, requiring careful consideration of practical aspects such as sterilization procedures and storage requirements.

The environmental and economic advantages of using CNF hydrogels position them favorably for future development. The renewable nature and potential for cost-effective production of these hydrogels align well with current sustainability initiatives. However, realizing this potential will require continued advancement in processing efficiency and scale-up capabilities. The successful translation of laboratory findings to practical applications will depend on addressing the aforementioned challenges while maintaining the fundamental properties that render these materials attractive for biomedical applications.

Future research directions should focus on developing sophisticated controlled-release mechanisms, improving drug loading efficiencies, and addressing the challenges of large-scale production. Integrating multiple stimuli-responsive elements and developing precise targeting mechanisms represent promising areas for investigation. Research efforts should clarify the long-term stability and degradation behavior of CNF hydrogels under physiological conditions and the interactions with various therapeutic agents. The cost-effectiveness and sustainability of CNF enhance its attractiveness from the environmental and financial perspectives, rendering it a promising material for next-generation drug delivery systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.W., M.G., H.J.H., and K.G.; methodology, H.J.H., Y.K., and K.H.Y.; software, M.C., C.L., J.M., Y.K., J.P., K.L.; validation, C.L., J.M., K.L., K.C.; formal analysis, J.P. and K.C.; resources, K.G.; writing—original draft preparation, T.W., M.G., H.J.H., Y.K., K.H.Y., K.L., J.P., K.C., S.L., and K.G.; writing—review and editing, H.J.H., and K.G.; visualization, C.L., J.M., and S.L.; supervision, K.G.; project administration, K.G.; funding acquisition, K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Kyungpook National University Research Fund, 2024

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNF |

Cellulose nanofibril |

| CNC |

Cellulose nanocrystal |

| TEMPO |

2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscope |

| U-CNF |

Untreated CNF |

| CM-CNF |

Carboxymethylated CNF |

| Q-CNF |

Quaternized CNF |

| PVP |

Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| PEG |

Poly (ethylene glycol) |

| SA |

Sodium alginate |

| TH |

Tetracycline hydrochloride |

| MPDA |

Mesoporous polydopamine |

| GO |

Graphene oxide |

| TOCN |

TEMPO-oxidized CNF |

| PPy |

Polypyrrole |

References

- M. I. Khan, X. An, L. Dai, H. Li, A. Khan, Y. Ni, Chitosan-based polymer matrix for pharmaceutical excipients and drug delivery, Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 2502–2513. [CrossRef]

- N. Lin, A. Dufresne, Nanocellulose in biomedicine: Current status and future prospect, Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 59, 302–325. [CrossRef]

- M. Rajinipriya, M. Nagalakshmaiah, M. Robert, S. Elkoun, Importance of agricultural and industrial waste in the field of nanocellulose and recent industrial developments of wood based nanocellulose: a review, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2807–2828. [CrossRef]

- H. Xie, H. Du, X. Yang, C. Si, Recent strategies in preparation of cellulose nanocrystals and cellulose nanofibrils derived from raw cellulose materials, Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2018, 2018, 7923068. [CrossRef]

- M. Pääkkö, M. Ankerfors, H. Kosonen, A. Nykänen, S. Ahola, M. Österberg, J. Ruokolainen, J. Laine, P.T. Larsson, O. Ikkala, Enzymatic hydrolysis combined with mechanical shearing and high-pressure homogenization for nanoscale cellulose fibrils and strong gels, Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 1934–1941. [CrossRef]

- T. Saito, S. Kimura, Y. Nishiyama, A. Isogai, Cellulose nanofibers prepared by TEMPO-mediated oxidation of native cellulose, Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 2485–2491.

-

L. Wågberg, G. Decher, M. Norgren, T. Lindström, M. Ankerfors, K. Axnäs, The build-up of polyelectrolyte multilayers of microfibrillated cellulose and cationic polyelectrolytes, Langmuir 2008, 24, 784–795.

-

R.J. Moon, A. Martini, J. Nairn, J. Simonsen, J. Youngblood, Cellulose nanomaterials review: structure, properties and nanocomposites, Chemical Society Reviews 2011, 40, 3941–3994. [CrossRef]

-

C. Aulin, S. Ahola, P. Josefsson, T. Nishino, Y. Hirose, M. Osterberg, L. Wagberg, Nanoscale Cellulose Films with Different Crystallinities and Mesostructures Their Surface Properties and Interaction with Water, Langmuir 2009, 25, 7675–7685. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lu, A.A. Aimetti, R. Langer, Z. Gu, Bioresponsive materials, Nature Reviews Materials 2016, 2, 1–17.

- J. J. Green, J.H. Elisseeff, Mimicking biological functionality with polymers for biomedical applications, Nature 2016, 540, 386–394. [CrossRef]

- J.W. Haycock, 3D cell culture: a review of current approaches and techniques, 3D cell culture: methods protocols (2010) 1-15.

- N. Fu, X. N. Fu, X. Zhang, L. Sui, M. Liu, Y. Lin, Application of scaffold materials in cartilage tissue engineering, Cartilage Regeneration (2017) 21-39.

- R. Jayakumar, M. Prabaharan, P.S. Kumar, S. Nair, H. Tamura, Biomaterials based on chitin and chitosan in wound dressing applications, Biotechnology advances 2011, 29, 322–337. [CrossRef]

- Fenton, K.N. Olafson, P. S. Pillai, M.J. Mitchell, R. Langer, Advances in biomaterials for drug delivery, Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1705328. [Google Scholar]

- J. Tavakoli, Y. Tang, Hydrogel based sensors for biomedical applications: An updated review, Polymers 2017, 9, 364. [CrossRef]

- E. Caló, V.V. Khutoryanskiy, Biomedical applications of hydrogels: A review of patents and commercial products, European polymer journal 2015, 65, 252–267. [CrossRef]

- K. J. De France, T. Hoare, E.D. Cranston, Review of hydrogels and aerogels containing nanocellulose, Chemistry of Materials 2017, 29, 4609–4631. [CrossRef]

- L. Mendoza, W. Batchelor, R.F. Tabor, G. Garnier, Gelation mechanism of cellulose nanofibre gels: A colloids and interfacial perspective, Journal of colloid interface science 2018, 509, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufresne, Nanocellulose: a new ageless bionanomaterial, Materials today 2013, 16, 220–227. [CrossRef]

- W. Im, S.Y. Park, S. Goo, S. Yook, H.L. Lee, G. Yang, H.J. Youn, Incorporation of CNF with different charge property into PVP hydrogel and its characteristics, Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 426. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cai, L. Geng, S. Chen, S. Shi, B.S. Hsiao, X. Peng, Hierarchical assembly of nanocellulose into filaments by flow-assisted alignment and interfacial complexation: conquering the conflicts between strength and toughness, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 32090–32098. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Fall, S.B. Lindstrom, O. Sundman, L. Ödberg, L. Wågberg, Colloidal stability of aqueous nanofibrillated cellulose dispersions, Langmuir 2011, 27, 11332–11338. [CrossRef]

- E. E. Ureña-Benavides, G. Ao, V.A. Davis, C.L. Kitchens, Rheology and phase behavior of lyotropic cellulose nanocrystal suspensions, Macromolecules 2011, 44, 8990–8998. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Håkansson, A.B. Fall, F. Lundell, S. Yu, C. Krywka, S.V. Roth, G. Santoro, M. Kvick, L. Prahl Wittberg, L. Wågberg, Hydrodynamic alignment and assembly of nanofibrils resulting in strong cellulose filaments, Nature communications 2014, 5, 4018. [CrossRef]

- X. Shen, J.L. Shamshina, P. Berton, G. Gurau, R.D. Rogers, Hydrogels based on cellulose and chitin: fabrication, properties, and applications, Green chemistry 2016, 18, 53–75. [CrossRef]

- C. Demitri, R. Del Sole, F. Scalera, A. Sannino, G. Vasapollo, A. Maffezzoli, L. Ambrosio, L. Nicolais, Novel superabsorbent cellulose-based hydrogels crosslinked with citric acid, Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2008, 110, 2453–2460. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Navarra, C. Dal Bosco, J. Serra Moreno, F.M. Vitucci, A. Paolone, S. Panero, Synthesis and characterization of cellulose-based hydrogels to be used as gel electrolytes, Membranes 2015, 5, 810–823. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Del Valle, A. Díaz, J. Puiggalí, Hydrogels for biomedical applications: cellulose, chitosan, and protein/peptide derivatives, Gels 2017, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Lindman, B. Medronho, L. Alves, C. Costa, H. Edlund, M. Norgren, The relevance of structural features of cellulose and its interactions to dissolution, regeneration, gelation and plasticization phenomena, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2017, 19, 23704–23718. [CrossRef]

- V. S. Raghuwanshi, Y. Cohen, G. Garnier, C.J. Garvey, R.A. Russell, T. Darwish, G. Garnier, Cellulose dissolution in ionic liquid: ion binding revealed by neutron scattering, Macromolecules 2018, 51, 7649–7655. [CrossRef]

- N. Mohd, S. N. Mohd, S. Draman, M. Salleh, N. Yusof, Dissolution of cellulose in ionic liquid: A review, AIP conference proceedings, AIP Publishing, 2017.

- T. Heinze, A. Koschella, Solvents applied in the field of cellulose chemistry: a mini review, Polímeros 2005, 15, 84–90. [CrossRef]

- J. Cai, L. Zhang, Rapid dissolution of cellulose in LiOH/urea and NaOH/urea aqueous solutions, Macromolecular bioscience 2005, 5, 539–548. [CrossRef]

- H. Dong, J.F. Snyder, K.S. Williams, J.W. Andzelm, Cation-induced hydrogels of cellulose nanofibrils with tunable moduli, Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 3338–3345. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, F. Xu, C.-R. Han, Metal ion mediated cellulose nanofibrils transient network in covalently cross-linked hydrogels: mechanistic insight into morphology and dynamics, Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 1019–1028. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, C. Fu, L.C. Yong, N. Sun, F.G. Liu, Flexible and Transparent PVA/CNF Hydrogel with Ultrahigh Dielectric Constant, ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2024, 6, 5706–5713. [CrossRef]

- N. E. Zander, H. Dong, J. Steele, J.T. Grant, Metal cation cross-linked nanocellulose hydrogels as tissue engineering substrates, ACS applied materials interfaces 2014, 6, 18502–18510. [CrossRef]

- H. Takeno, H. Inoguchi, W.-C. Hsieh, Mechanical and structural properties of cellulose nanofiber/poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogels cross-linked by a freezing/thawing method and borax, Cellulose 2020, 27, 4373–4387. [CrossRef]

- R. Hobzova, J. Hrib, J. Sirc, E. Karpushkin, J. Michalek, O. Janouskova, P. Gatenholm, Embedding of bacterial cellulose nanofibers within PHEMA hydrogel matrices: Tunable stiffness composites with potential for biomedical applications, Journal of Nanomaterials 2018, 2018, 5217095. [CrossRef]

- J. Wei, Y. Chen, H. Liu, C. Du, H. Yu, Z. Zhou, Thermo-responsive and compression properties of TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofiber-modified PNIPAm hydrogels, Carbohydrate polymers 2016, 147, 201–207. [CrossRef]

- K. Syverud, H. Kirsebom, S. Hajizadeh, G. Chinga-Carrasco, Cross-linking cellulose nanofibrils for potential elastic cryo-structured gels, Nanoscale research letters 2011, 6, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- C. A. García-González, M. Alnaief, I. Smirnova, Polysaccharide-based aerogels—Promising biodegradable carriers for drug delivery systems, Carbohydrate polymers 2011, 86, 1425–1438. [CrossRef]

- T. R. Hoare, D.S. Kohane, Hydrogels in drug delivery: Progress and challenges, Polymer 2008, 49, 1993–2007. [CrossRef]

- R. Curvello, V.S. Raghuwanshi, G. Garnier, Engineering nanocellulose hydrogels for biomedical applications, Advances in colloid interface science 2019, 267, 47–61. [CrossRef]

- D. Plackett, K. Letchford, J. Jackson, H. Burt, A review of nanocellulose as a novel vehicle for drug delivery, Nordic Pulp Paper Research Journal 2014, 29, 105–118. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xue, Z. Mou, H. Xiao, Nanocellulose as a sustainable biomass material: structure, properties, present status and future prospects in biomedical applications, Nanoscale 2017, 9, 14758–14781. [CrossRef]

- C. A. García-González, M. Alnaief, I.J.C.p. Smirnova, Polysaccharide-based aerogels—Promising biodegradable carriers for drug delivery systems, 2011, 86, 1425–1438. [CrossRef]

- N. Masruchin, B.-D. Park, V. Causin, Dual-responsive composite hydrogels based on TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibril and poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) for model drug release, Cellulose 2018, 25, 485–502. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, C. Yang, W. Zhou, Q. Luan, W. Li, Q. Deng, X. Dong, H. Tang, F. Huang, A pH-responsive gel macrosphere based on sodium alginate and cellulose nanofiber for potential intestinal delivery of probiotics, ACS Sustainable Chemistry Engineering 2018, 6, 13924–13931. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, Q. Fan, Y. Huo, C. Liu, B. Li, Y. Li, Construction of a mesoporous polydopamine@ GO/cellulose nanofibril composite hydrogel with an encapsulation structure for controllable drug release and toxicity shielding, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 57410–57420. [CrossRef]

- N. Lin, A. Gèze, D. Wouessidjewe, J. Huang, A. Dufresne, Biocompatible double-membrane hydrogels from cationic cellulose nanocrystals and anionic alginate as complexing drugs codelivery, ACS applied materials & interfaces 2016, 8, 6880–6889. [CrossRef]

- P. Laurén, Y.-R. Lou, M. Raki, A. Urtti, K. Bergström, M. Yliperttula, Technetium-99m-labeled nanofibrillar cellulose hydrogel for in vivo drug release, European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2014, 65, 79–88. [CrossRef]

- H. Paukkonen, M. Kunnari, P. Laurén, T. Hakkarainen, V.-V. Auvinen, T. Oksanen, R. Koivuniemi, M. Yliperttula, T. Laaksonen, Nanofibrillar cellulose hydrogels and reconstructed hydrogels as matrices for controlled drug release, International journal of pharmaceutics 2017, 532, 269–280. [CrossRef]

- N. Lin, A. Gèze, D. Wouessidjewe, J. Huang, A. Dufresne, Biocompatible double-membrane hydrogels from cationic cellulose nanocrystals and anionic alginate as complexing drugs codelivery, ACS applied materials interfaces 2016, 8, 6880–6889. [CrossRef]

- A. N. Zelikin, C. Ehrhardt, A.M. Healy, Materials and methods for delivery of biological drugs, Nature chemistry 2016, 8, 997–1007. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Furth, A. Atala, Tissue engineering: future perspectives, Principles of tissue engineering, Elsevier2014, pp. 83–123.

- L. Moroni, J. Schrooten, R. Truckenmüller, J. Rouwkema, J. Sohier, C.A. van Blitterswijk, Tissue engineering: an introduction, Tissue engineering, Elsevier2014, pp. 1–21.

-

R.M. Domingues, M.E. Gomes, R.L. Reis, The potential of cellulose nanocrystals in tissue engineering strategies, Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 2327–2346. [CrossRef]

-

S.J. Hollister, Porous scaffold design for tissue engineering, Nature materials 2005, 4, 518–524. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Drury, D.J. Mooney, Hydrogels for tissue engineering: scaffold design variables and applications, Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4337–4351. [CrossRef]

- Khademhosseini, R. Langer, Microengineered hydrogels for tissue engineering, Biomaterials 2007, 28, 5087–5092.

- R. Hou, Y. Xie, R. Song, J. Bao, Z. Shi, C. Xiong, Q. Yang, Nanocellulose/polypyrrole hydrogel scaffolds with mechanical strength and electrical activity matching native cardiac tissue for myocardial tissue engineering, Cellulose 2024, 31, 4247–4262. [CrossRef]

- Nishiguchi, T. Taguchi, A thixotropic, cell-infiltrative nanocellulose hydrogel that promotes in vivo tissue remodeling, ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2020, 6, 946–958. [CrossRef]

- K. Markstedt, A. Mantas, I. Tournier, H. Martínez Ávila, D. Hagg, P. Gatenholm, 3D bioprinting human chondrocytes with nanocellulose–alginate bioink for cartilage tissue engineering applications, Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 1489–1496. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Ávila, S. Schwarz, N. Rotter, P. Gatenholm, 3D bioprinting of human chondrocyte-laden nanocellulose hydrogels for patient-specific auricular cartilage regeneration, Bioprinting 2016, 1, 22–35. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu, X. Zeng, C. Ma, H. Yi, Z. Ali, X. Mou, S. Li, Y. Deng, N. He, Injectable hydrogels for cartilage and bone tissue engineering, Bone research 2017, 5, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhong, Y. Zhang, C. Lim, Tissue scaffolds for skin wound healing and dermal reconstruction, Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine Nanobiotechnology 2010, 2, 510–525.

- Doench, M.E. Torres-Ramos, A. Montembault, P. Nunes de Oliveira, C. Halimi, E. Viguier, L. Heux, R. Siadous, R.M. Thiré, A. Osorio-Madrazo, Injectable and gellable chitosan formulations filled with cellulose nanofibers for intervertebral disc tissue engineering, Polymers 2018, 10, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. V. Murphy, A. Atala, 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs, Nature biotechnology 2014, 32, 773–785. [CrossRef]

- C. Mandrycky, Z. Wang, K. Kim, D.-H. Kim, 3D bioprinting for engineering complex tissues, Biotechnology advances 2016, 34, 422–434. [CrossRef]

- H. -W. Kang, S.J. Lee, I.K. Ko, C. Kengla, J.J. Yoo, A. Atala, A 3D bioprinting system to produce human-scale tissue constructs with structural integrity, Nature biotechnology 2016, 34, 312–319. [CrossRef]

- L. Dai, T. Cheng, C. Duan, W. Zhao, W. Zhang, X. Zou, J. Aspler, Y. Ni, 3D printing using plant-derived cellulose and its derivatives: A review, Carbohydrate polymers 2019, 203, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. C. Piras, S. Fernández-Prieto, W.M. De Borggraeve, Nanocellulosic materials as bioinks for 3D bioprinting, Biomaterials science 2017, 5, 1988–1992. [CrossRef]

- T. -S. Jang, H.-D. Jung, H.M. Pan, W.T. Han, S. Chen, J. Song, 3D printing of hydrogel composite systems: Recent advances in technology for tissue engineering, International Journal of Bioprinting 2018, 4, 126. [CrossRef]

- S. Shin, S. Park, M. Park, E. Jeong, K. Na, H.J. Youn, J. Hyun, Cellulose nanofibers for the enhancement of printability of low viscosity gelatin derivatives, BioResources 2017, 12, 2941–2954. [CrossRef]

- T. Hakkarainen, R. Koivuniemi, M. Kosonen, C. Escobedo-Lucea, A. Sanz-Garcia, J. Vuola, J. Valtonen, P. Tammela, A. Mäkitie, K. Luukko, Nanofibrillar cellulose wound dressing in skin graft donor site treatment, Journal of Controlled Release 2016, 244, 292–301. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Seabra, J.S. Bernardes, W.J. Fávaro, A.J. Paula, N. Durán, Cellulose nanocrystals as carriers in medicine and their toxicities: A review, Carbohydrate polymers 2018, 181, 514–527. [CrossRef]

- I. A. Sacui, R.C. Nieuwendaal, D.J. Burnett, S.J. Stranick, M. Jorfi, C. Weder, E.J. Foster, R.T. Olsson, J.W. Gilman, Comparison of the properties of cellulose nanocrystals and cellulose nanofibrils isolated from bacteria, tunicate, and wood processed using acid, enzymatic, mechanical, and oxidative methods, ACS applied materials interfaces 2014, 6, 6127–6138. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, J.-J. Zhao, C.-R. Han, J.-F. Duan, F. Xu, R.-C. Sun, Tough nanocomposite hydrogels from cellulose nanocrystals/poly (acrylamide) clusters: influence of the charge density, aspect ratio and surface coating with PEG, Cellulose 2014, 21, 541–551.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).