1. Introduction

Migrant women with schizophrenia experience compounded vulnerabilities stemming from trauma, cultural dislocation, and barriers to care

[1]. These risks are especially pronounced among refugees, who face higher rates of psychosis than non-refugee migrants and native-born populations. These risks are especially pronounced among refugees, who face higher rates of psychosis than non-refugee migrants and native-born populations. As the authors point out, refugee women are at a greater risk of developing schizophrenia compared to both non-refugee migrants and individuals born in the host country. Contributing factors include limited social support, language barriers, and poor access to mental health services

[1]. Although empirical research on AI applications for this population remains limited, emerging tools show promise for culturally responsive, multilingual mental health support

[2]. This review explores the potential of AI to address these gaps while considering ethical, structural, and clinical challenges.

1.1. Definition and Theoretical Evolution

Schizophrenia is a chronic and severe psychiatric disorder characterized by disturbances in perception, thought, emotion, and behavior, typically manifesting in late adolescence or early adulthood [

3]. Core symptoms include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking and behavior, and negative symptoms such as diminished emotional expression or avolition [

3]. The DSM-5 conceptualizes schizophrenia as a heterogeneous disorder, favoring dimensional assessments over rigid subtypes to reflect its clinical diversity and progression better [

3]. It’s a serious disorder that affects not only individuals but broader communities as well. The disorder presents a substantial economic burden, with global costs ranging from 0.02% to 1.65% of GDP, particularly in high-income countries [

4]The annual economic cost of schizophrenia varies widely, from US

$94 million to US

$102 billion [

4]. In developed nations, healthcare expenses for schizophrenia constitute 1.4% to 2.8% of national health expenditures, with up to 20% of mental health costs attributed to the disorder [

5]. Moreover, schizophrenia has the highest median societal cost per patient when compared to other mental health conditions [

6] making the treatment of individuals with this disorder a priority.

Contemporary research supports the neurodevelopmental hypothesis, suggesting that schizophrenia arises from early brain development disruptions influenced by both genetic and environmental factors [

7]. Genomic evidence further places schizophrenia on a continuum with other neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), ADHD, and intellectual disability. These conditions share overlapping genetic risk factors, including common alleles and rare copy number variants, supporting a gradient model of developmental impairment [

7].

Historically, Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) conceptualized schizophrenia as

dementia praecox, unifying diverse psychotic conditions into a single disease entity characterized by early onset and a progressive course of cognitive and behavioral decline [

8]. Eugen Bleuler (1857–1939) redefined Kraepelin’s concept by coining the term

schizophrenia and broadening it to include cases without terminal deterioration, emphasizing core features like thought derailment, ambivalence, affective incongruence, and social withdrawal. He viewed schizophrenia as a group of related disorders rather than a single disease entity [

8]. In the following decades, clinicians expanded the schizophrenia spectrum by introducing subtypes such as schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform psychoses, and distinctions like process–nonprocess and paranoid–nonparanoid forms. Kurt Schneider further refined diagnostic criteria by proposing nine “first-rank symptoms” (FRS) that he believed held decisive diagnostic weight, including thought broadcasting, auditory hallucinations, delusional perception, and experiences of external control [

8]. Additionally, contemporary spectrum-based theories increasingly conceptualize schizophrenia alongside related conditions such as schizotypal personality disorder and bipolar disorder. The clinical validity of schizophrenia as a distinct diagnostic category is further challenged by global variations in prevalence and inconsistencies in diagnostic reliability [

9]. Differences in study design, geographic region, and diagnostic definitions significantly influence reported prevalence rates, with broader spectrum criteria increasing case identification by as much as 90% [

9].

1.2. Understanding Women’s Migration: Definitions, Historical Patterns, and Post-Migration Challenges

Women’s migration has long been framed through a lens of dependency, where women were viewed primarily as accompanying male family members during migration. This perspective dominated much of the early migration literature and policy narratives, which treated women as passive dependents rather than active agents [

10]. However, more recent scholarship has challenged this narrow view by emphasizing women’s increasing roles as autonomous and strategic migrants who initiate movement for reasons such as economic opportunity, family reunification, or personal safety [

11].

In many cases, women migrate independently due to forced displacement, conflict, or gender-based violence, assuming the responsibility for rebuilding family lives and navigating complex resettlement systems on their own [

11]. Their experiences are shaped by intersecting challenges both before and after migration, including trauma, loss, and ongoing concerns for family members left behind [

12]. Upon arrival in host countries, women often face layered barriers such as language difficulties, cultural stigma, lack of culturally competent health services, and socioeconomic marginalization, which can significantly impact their ability to access care and build support networks [

12].

Despite these difficulties, studies show that women display remarkable resilience and adaptability [

11]. In Australia, refugee women who arrived under the Women at Risk visa scheme demonstrated the ability to mobilize both local and transnational social ties to support their mental health and well-being, often serving as emotional and financial anchors for family members across borders [

11]. Similarly, in Canada, immigrant and refugee women used informal support systems, self-care practices, and culturally grounded coping mechanisms to manage mental health issues in the face of systemic exclusion from formal care pathways [

12] These evolving narratives suggest that women are not only central actors in migration processes but also key figures in post-migration adaptation and resilience, often taking on leadership roles in sustaining their families and communities across borders [

11,

12].

Gender-specific motivations and vulnerabilities significantly shape the migration experience, with structural factors, including socio-economic pressure and demographic imbalances, influencing patterns of movement [

13]. For instance, rural male demographic imbalances in South Korea have led to an increase in cross-border marriages with women from countries such as Vietnam. Among these women, approximately 62% reported experiencing at least one form of discrimination, which significantly contributed to depressive symptoms, increasing the explained variance of such symptoms by 17% [

13] Forced migration due to war, political instability, and persecution has particularly impacted women, leading the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to classify many as “women-at-risk.” Countries such as Australia have accepted thousands of women under resettlement visas, often arriving without male protection and facing additional risks including gender-based violence, social isolation, and limited access to services [

11].

Upon resettlement, migrant women face persistent post-migration stressors that significantly affect their mental health. One major factor is discrimination, which often prevents women from seeking help due to fear of stigma and mistrust of healthcare systems [

12]. Many delays care until symptoms become severe, including psychosis and suicidal ideation. Another key issue is acculturative stress, which stems from adjusting to a new culture, language, and social norms. This stress has been directly linked to increased rates of depression (55.3%) and anxiety (45.6%) among Iraqi refugee women in the U.S. [

14]. The more acculturative stress they experienced, the greater their mental health risks. Lastly, community disconnection and family violence play a critical role. Even more than war-related trauma, family violence was the strongest predictor of depression, anxiety, and somatization in a study of 620 refugee women in Germany [

15]. Despite being less frequent, such violence had a more severe psychological impact.

A longitudinal study by Vromans et al. [

16] investigated the psychological wellbeing of 83 refugee women-at-risk resettled in Australia, one year after arrival. These women, identified as vulnerable by the UN due to factors like gender-based violence and lack of protection, were assessed for trauma exposure, post-migration stressors, and levels of trust in their communities. The findings revealed that 39% of participants reported traumatization and depression, 32% experienced anxiety, and 20% met clinical criteria for PTSD. High levels of somatization and loss-related distress were also reported. The study emphasized that post-migration problems and absence of trust in community members were key predictors of poor mental health outcomes [

16].

While local and transnational social ties can act as protective buffers, these are often fragile or inaccessible due to social, linguistic, and cultural barriers [

11]. Moreover, women’s migration needs to be examined through an intersectional framework that integrates gender-based vulnerabilities, historical patterns, and cumulative migration-related stressors [

17]. Such understanding is essential for creating trauma-informed, culturally competent, and gender-sensitive mental health interventions in migrant contexts [

15]. Given these multifaceted challenges, there is an urgent need to explore alternative, scalable interventions such as AI-based mental health technologies, which have demonstrated success in improving treatment adherence and detecting relapse risks among individuals with schizophrenia [

18].

1.3. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence to Improve Mental Health Access for Migrant Women with Schizophrenia

Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to the ability of machines to replicate human cognitive tasks such as learning, reasoning, and decision-making, often with adaptive, communicative, or data-driven capabilities [

19]. One of the earliest examples of AI in mental health was ELIZA, a symbolic program designed to simulate therapist–patient dialogue through pre-programmed scripts. Although limited in complexity, ELIZA demonstrated the potential for computers to engage in human-like communication [

20]. Since then, AI has evolved to incorporate machine learning models capable of analyzing complex psychiatric data. These models have shown strong potential in identifying patterns across neuroimaging, behavioral, and clinical datasets to assist in the early detection of schizophrenia [

21].

In a recent study, Hansen and colleagues applied machine learning classifiers such as XGBoost and elastic net logistic regression to over 24,000 electronic health records to predict diagnostic progression toward schizophrenia [

22]. The models performed particularly well when using unstructured clinical notes, highlighting the value of narrative data in psychiatric prediction [

22]. These technological advancements hold significant promise for improving mental health care among migrant women, who often face systemic barriers, cultural stigma, and limited access to early psychiatric assessment [

21,

22].

More recently, Hansen et al. [

22] applied advanced ML models, including XGBoost and elastic net logistic regression, to predict diagnostic progression to schizophrenia or bipolar disorder using data from over 24,000 Danish patients. Their findings revealed that schizophrenia was more reliably predicted than bipolar disorder, and that unstructured clinical notes contributed significantly to predictive accuracy [

22]. These results underscore the promise of ML in early identification and risk stratification of severe mental illnesses [

21,

22]. For migrant and refugee women, who often face diagnostic delays due to cultural stigma, language barriers, and systemic exclusion, AI-based tools that integrate clinical narratives and contextual variables may offer earlier and more equitable access to mental health care [

21,

22].

In their development of the Community Therapeutic Space (CTS) model, Natividad et al. [

23] include digitalization in healthcare as one of the key thematic areas to support women living with schizophrenia. This focus is represented by the “Black Corner,” which draws on findings from three studies addressing how digital tools can enhance access to and participation in mental health services. Although discussed briefly, this component acknowledges the growing importance of digital inclusion in mental health care delivery, especially for populations that may face social, economic, or systemic barriers [

23]. By incorporating digitalization as a core element, the CTS model aims to improve outreach and engagement strategies for women with complex clinical and social needs, contributing to a more holistic and accessible care framework [

23].

In a more targeted analysis, Pozzi et al. [

24] examine how artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled mental health chatbots have been deployed among Syrian refugees to deliver cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and low-intensity psychological support. The authors underscore the ethical challenges these tools may pose, particularly in contexts where users face linguistic, cultural, or epistemic marginalization [

24]. They advocate for capability-sensitive AI design that respects the lived experiences and cultural contexts of vulnerable populations [

24]. This emphasis on ethical design is echoed in studies involving individuals with schizophrenia. For example, women participants using an AI-enhanced mobile health platform reported the system to be supportive and acceptable for managing their symptoms and medication adherence [

18]. Likewise, patients in a relapse prediction study appreciated how AI tools promoted self-reflection and improved communication with providers, though they stressed the need for empathy and privacy in such interventions [

25]. These findings reinforce the argument that AI tools, when ethically implemented and aligned with user needs, can play a meaningful role in extending mental health support to structurally marginalized populations, including refugee women living with schizophrenia.

Given the significance of AI tools in providing mental health interventions to vulnerable populations, it is critical to understand the benefits and challenges more fully. This review addresses three central themes: (1) the capacity of AI tools to deliver culturally and linguistically responsive care to migrant women with schizophrenia; (2) the ethical, structural, and clinical barriers to AI implementation; and (3) the effectiveness of these technologies in enhancing care access and engagement among this population. Together, these themes offer a framework for evaluating how AI may complement conventional care and address longstanding service gaps affecting a highly vulnerable group.

2. Methods

This study adopts a narrative literature review methodology. As noted by Sukhera [

26], narrative reviews differ from systematic reviews in that they allow flexibility in the selection of sources, prioritizing a broader understanding of diverse perspectives over strict inclusion or exclusion criteria. Rather than aiming for exhaustive coverage, narrative reviews focus on generating meaningful interpretations shaped by the researchers’ contextual, institutional, or historical lenses. Grounded in interpretivist and subjectivist traditions, this approach is well-suited for exploring the nuanced dimensions of emerging educational innovations. It also supports the ongoing refinement of research questions and scope throughout the review process, enabling responsiveness to the evolving nature of the topic [

26]. Accordingly, this review draws from peer-reviewed sources accessed through ERIC, EBSCOhost, PsycINFO, and PubMed, with a particular emphasis on literature that explores the educational and ethical implications of ChatGPT in higher education contexts

A systematic Boolean search approach was created to facilitate the literature search for the present narrative review. The table below presents the key concepts, Boolean connectors, and justification for the combination. The use of a structured approach ensures thorough coverage for relevant studies on artificial intelligence and mental health, schizophrenia, and the distinct experience of migrant women.

Table 1 outlines the Boolean search approach employed to identify relevant peer-reviewed studies.

Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were established for this narrative review to ensure relevance quality and methodological clarity. These criteria guided the selection of studies addressing the intersection of artificial intelligence mental health care schizophrenia and the experiences of migrant women.

Table 2 outlines the applied criteria along with their respective rationales

Review Process

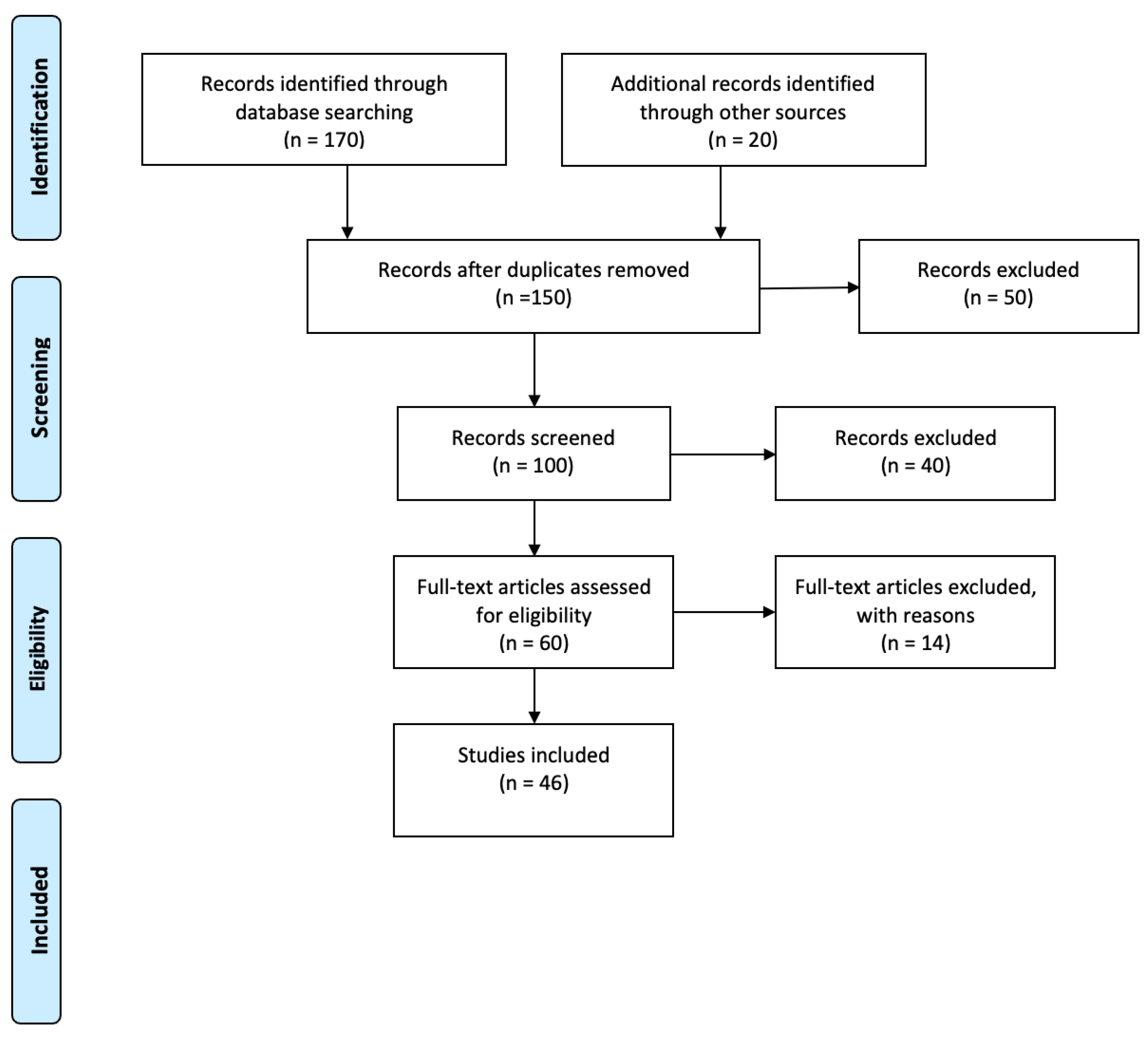

Article selection began with screening the title, abstract, and conclusion for alignment with the predetermined review criteria. Duplicate entries were then deleted, and the remaining articles were subjected to a detailed full-text appraisal for relevance to the focus of the review. A total of 46 studies were finally included. The narrative appraisal was informed by the SANRA scale (Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles), created by Baethge et al. [

27], a six-point scale designed to assess non-systematic narrative reviews. SANRA assesses crucial dimensions, including the clarity of aims, the search strategy, citation standards, the rationality of argument, and the inclusion of relevant supporting information. Each element receives a score on a scale ranging from 0 (low) to 2 (high), for a total score of 12. The tool’s initial validation showed acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.68) and inter-rater agreement (ICC = 0.77). To maintain a transparent approach to screening, we employed the PRISMA-ScR flowchart, as described by Tricco et al. [

28].

3. Results

3.1. Screening Overview

The preliminary database search retrieved 190 records. After removing duplicates and an initial review of titles and abstracts, a reduced set of articles was subjected to a full-text assessment. Based on the defined criteria for inclusion and exclusion, a total of 46 studies were ultimately included in the final review. The step-by-step selection process is outlined in

Figure 1.

3.2. Study Profile

The overall set of 46 studies encompassed a range of research methods, including reviews, qualitative and quantitative studies, as well as mixed-methods research. The articles cover a variety of countries and educational institutions, offering a diverse international perspective on the application and impact of AI-based detection tools within academia.

4. Discussion

Schizophrenia is a chronic and disabling psychiatric disorder affecting nearly 24 million people globally [

25], with migrant women experiencing heightened risks due to trauma, cultural stigma, and limited access to care [

1]. AI systems must incorporate cultural sensitivity, allowing for more empathetic support for migrant women who face unique stressors that traditional mental health systems fail to address [

29]. By integrating cultural context into AI models, these tools can bridge linguistic and cultural gaps, improving engagement and care outcomes [

29]. This discussion explores how artificial intelligence (AI) tools can enhance culturally and linguistically appropriate care, address ethical and structural challenges, and improve access and engagement for this underserved population

4.1. The Role of AI Tools in Improving Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Care for Migrant Women with Schizophrenia

Due to intersecting linguistic, cultural, and systemic barriers, migrant women with schizophrenia often remain underserved in traditional mental health systems [

2]. Recent advances in AI offer new possibilities for tailoring care to their specific needs through language-sensitive communication, cultural adaptation, and remote engagement [

2]. Given this potential, this section explores how AI tools, particularly those leveraging natural language processing, cultural ontologies, and emotion recognition, can improve the cultural and linguistic responsiveness of mental health care for this vulnerable group [

2].

4.1.1. Enhancing Linguistic Accessibility Through NLP and Translation

Artificial intelligence tools equipped with natural language processing (NLP) have shown strong potential in identifying emotionally nuanced expressions in individuals with schizophrenia

[2] . For instance, individuals with schizophrenia often exhibit deficits in emotional prosody processing, including reduced ability to express emotions through tone, pitch, speech rate, and rhythm features that AI-based speech analysis can detect more precisely than traditional clinical methods

[2]. These deficits are well-established in clinical literature. A meta-analysis of 29 studies confirmed that individuals with schizophrenia demonstrate significant impairments in emotional prosody processing, with a large overall effect size (d = –0.92), particularly in emotion identification tasks (d = –0.95), and greater difficulty with emotional than neutral stimuli. These deficits were linked to dysfunction in right-lateralized brain regions such as the auditory cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, and auditory-insula connectivity, along with impaired pre-attentive and attentive processes

[30].

Building on this evidence, recent advancements in machine learning have leveraged prosodic speech features, such as pitch variability, rhythm, and pause patterns for classification tasks in psychiatric assessment

[31]. In this context, classification refers to the algorithmic process of distinguishing between individuals with schizophrenia and healthy controls based on their speech characteristics

[31]. A recent study demonstrated that acoustic prosodic features alone enabled machine learning models to achieve classification accuracy of approximately 90%, outperforming models that relied solely on lexical or syntactic features

[31]. This suggests that emotional and temporal speech patterns offer unique, language-independent diagnostic signals

[31]. Furthermore, the authors emphasized that prosody-enhanced AI tools can provide more interpretable, scalable, and culturally inclusive solutions for the clinical screening and monitoring of schizophrenia

[31]. NLP models can also evaluate semantic coherence and language fluency, offering insight into disorganized thinking and cognitive disruptions

[2]. By integrating NLP with neurophysiological and neuroimaging data, AI systems improve diagnostic accuracy and enable more comprehensive modeling of symptomatology

[2]. Additionally, digital platforms powered by AI, including chatbots, provide continuous monitoring and support, which is particularly beneficial for individuals experiencing social withdrawal or symptom fluctuations

[2].

Machine learning has also been demonstrated to model blunted vocal affect (BvA) and alogia accurately from speech features, achieving high classification accuracy for these symptoms using computerized vocal expression analysis

[32]. The study found that machine learning models, particularly when computed separately by speaking task, could accurately predict BvA and alogia, offering valuable insights into improving diagnostic accuracy and monitoring the severity of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Additionally, there has been a growing interest in using natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning to develop linguistic biomarkers for schizophrenia, emphasizing the need to integrate these techniques for improved diagnosis and symptom tracking

[33]. The application of deep learning-based models for detecting schizophrenia from speech has also been explored, incorporating emotional stimuli and features such as Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) to improve detection accuracy. Integrating emotional stimuli with demographic data has been shown to enhance both sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing schizophrenia from healthy controls, with an accuracy of 91.7% and a ROC-AUC of 0.963

[34]. These capabilities underscore the potential of AI in delivering more personalized and linguistically sensitive care for individuals with schizophrenia.

4.1.2. Culturally Responsive AI for Personalized Mental Health Support

International migration has increased significantly in recent decades, with over 125,000 women immigrating to Canada annually, most in their childbearing years and many having given birth before migration [

35]. Migration policies and economic constraints often result in prolonged family separation, particularly affecting women who migrate without their children. These “dual-country” (DC) mothers, that is, women who gave birth in Canada after being separated from their children who remain in their home country, face a unique intersection of stressors, including emotional trauma from separation, adaptation challenges in new sociocultural environments, and limited access to healthcare and social support [

35]. Recognizing the compounded vulnerabilities of this population, a study of 514 multiparous migrant women who gave birth in Canada found that 18% were classified as DC mothers [

35]. Cultural beliefs surrounding mental illness influence how migrant women express symptoms and whether they seek care. Many DC mothers faced elevated risks of postpartum depression, anxiety, and trauma-related symptoms upon giving birth in Canada [

35]. Despite these risks, their distress often remained underreported, shaped by expectations of maternal duty, emotional strength, and barriers to care access.

They were also significantly more likely to experience poverty, social isolation, and food insecurity, all of which further strained mental health [

35]. Compared to non-DC migrant mothers, DC mothers were more likely to face structural disadvantages: poverty (36.0% vs. 18.6%), food insecurity (16.3% vs. 7.6%), lack of a partner (40.2% vs. 11.4%), and absence of social support (23.1% vs. 12.2%). Additionally, over 83% of DC mothers were asylum seekers or refugees, increasing their vulnerability. These factors were linked with higher rates of postpartum depression (28.3% vs. 18.6%), clinical depression (23.1% vs. 13.5%), and trauma-related anxiety (16.5% vs. 9.4%) [

35]. Seeman[

36] emphasizes that individuals from different cultural backgrounds may interpret the same psychotic symptoms (e.g., hallucinations or delusions) very differently, at times viewing them as culturally normative rather than pathological. This variation can result in over-diagnosis or missed diagnoses, depending on a clinician's cultural lens [

36]. She further explains that sex and gender differences affect the incidence, expression, and outcomes of schizophrenia, which is shaped by both biological mechanisms (e.g., hormones, genetics) and social roles [

36].

For instance, women tend to experience later onset, more affective symptoms like depression, and better short-term outcomes, while men are more prone to negative symptoms such as disorganized behavior or emotional withdrawal [

36]. Moreover, reproductive stages including menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause significantly influence symptom patterns and treatment responses in women, which are often overlooked in standard clinical guidelines [

36]. These findings emphasize the importance of culturally and gender-responsive diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in schizophrenia care. In response to such diagnostic limitations, emerging research explores how artificial intelligence (AI) can enhance culturally and gender-sensitive mental health care, especially for marginalized groups [

37,

38].

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly recognized as a promising tool to alleviate maternal mental health (MMH) challenges, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where access to psychological services remains limited [

37]. Perinatal depression and anxiety (PDA) are especially prevalent and often go undiagnosed in these regions due to compounding factors such as poverty, social stigma, and inadequate health infrastructure [

37]. In response, researchers have begun applying AI for early identification, risk assessment, and the delivery of supportive interventions. A recent systematic review analyzing 19 studies from eight LMICs found that supervised machine learning was the most frequently employed approach for detecting PDA [

37]. Additionally, the review highlighted the emerging role of chatbots and conversational agents as accessible platforms for delivering psychological support, although these technologies remain underused and insufficiently explored [

37].

These developments point to the broader applicability of AI in mental health care, with potential benefits for other at-risk populations such as migrant women vulnerable to schizophrenia. As digital mental health infrastructure and data sources expand, machine learning (ML) is gaining traction as an effective strategy for addressing psychiatric disparities among underserved communities [

38]. In particular, ML models have been utilized to classify and predict mental health conditions in immigrants, refugees, and racial or ethnic minorities groups often burdened by trauma, cultural stigma, and systemic obstacles to care [

38]. A recent scoping review encompassing 13 peer-reviewed studies found that supervised learning techniques dominated these efforts [

38]. However, the lack of clinical validation across many studies limits their translation into practical settings. Despite this limitation, the review underscores the growing momentum behind AI-driven approaches aimed at bridging diagnostic gaps and enhancing culturally responsive mental health interventions for marginalized populations [

38].

Refugee women-at-risk face compounded psychological vulnerabilities stemming from pre-migration trauma, displacement, and gender-based violence, along with post-migration challenges such as cultural dislocation, language barriers, and social isolation [

39]. In their study of recently resettled refugee women in Australia, Schweitzer et al. [

39] identified widespread symptoms of trauma, depression, anxiety, and somatization across participants. These mental health concerns were closely linked to the number of traumatic experiences women had endured, such as sexual assault, imprisonment, and family separation, as well as ongoing post-migration difficulties like loneliness, disrupted family networks, and communication problems [

39]. The presence of children limited social support, and cultural unfamiliarity further intensified psychological strain for many participants. Given these complex and intersecting stressors, the study emphasizes the critical need for culturally appropriate and gender-responsive mental health care that reflects the lived realities of refugee women-at-risk [

39]. Together, these findings highlight the promising potential of culturally and gender-responsive AI tools to improve diagnostic accuracy, enhance access, and deliver personalized mental health support for marginalized groups such as migrant women with schizophrenia.

4.1.3. Emotion Recognition and Community-Based Engagement

AI-driven emotion recognition tools offer a promising complement to traditional mental health care, particularly for women with schizophrenia who face structural and cultural barriers to consistent in-person evaluation [

2,

31]. In a comprehensive review, Jiang et al. [

2] examined how artificial intelligence (AI) technologies can enhance the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of schizophrenia by addressing the disorder’s clinical heterogeneity and limitations in current psychiatric practices. They emphasize that machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models are capable of processing complex, multidimensional datasets, allowing for more objective and precise clinical decisions [

2].

Their findings show that AI systems can integrate neuroimaging data, behavioral indicators, genetic profiles, and language patterns to improve the early identification of at-risk individuals and tailor treatment strategies for those with treatment-resistant schizophrenia [

2]. A key focus of the review is on natural language processing (NLP), which enables the detection of linguistic disruptions such as reduced semantic coherence and impaired emotional prosody markers often associated with cognitive and affective symptoms in schizophrenia [

2]. These AI techniques can monitor speech-related changes over time, making them particularly useful in remote and asynchronous care settings where frequent clinical interactions are not feasible [

2].

Additionally, Jiang et al., [

2] note that AI-based analysis of language and behavioral data supports dynamic symptom tracking, which is essential for recognizing disease progression and adjusting interventions accordingly. However, they caution that AI should serve as a supplementary tool within a clinician-led framework, reinforcing the need for professional oversight and human-centered care [

2]. Yoo et al. [

25]investigated how individuals with lived experience of schizophrenia perceive AI-based relapse prediction tools. Their study addressed a critical gap in the literature by focusing not only on the technical aspects of AI but also on patients’ subjective experiences with these systems [

25]. In the first phase, the researchers conducted semi-structured interviews with 48 participants in South Korea who had previously experienced schizophrenia and were currently in recovery [

25]. These interviews explored how patients conceptualized relapse and responded to the idea of AI systems using behavioral and social data, such as language use on social media, for predictive purposes [

25].

Thematic analysis revealed a recurring skepticism among participants regarding the reliability of algorithm-generated predictions [

25]. Many reported that relapse events were often shaped by social and interpersonal dynamics, such as conflict or isolation, which AI tools typically fail to capture or contextualize [

25]. This led to concerns about mismatches between AI predictions and lived experiences, with participants warning that inaccurate alerts could lead to emotional distress or unnecessary clinical intervention [

25]. To examine these concerns more concretely, the research team developed a prototype system that used participants’ Facebook data to forecast relapse risk [

25]. Feedback was collected from a subset of seven participants who interacted with the prototype [

25]. While a few found the idea of early warnings beneficial for self-monitoring, others expressed discomfort about the possibility of being misunderstood or surveilled by the system, especially without human context or support [

25]. Ethical concerns were also raised, including issues of transparency, autonomy, and the emotional consequences of receiving predictive alerts [

25]. Overall, the study emphasized that AI tools for relapse detection must be designed in ways that are not only clinically accurate but also socially and ethically responsive to users’ lived realities [

25].

Community-based therapeutic models are essential in addressing the specific psychosocial and health needs of women with schizophrenia, particularly those facing socioeconomic exclusion [

23]. The Community Therapeutic Space (CTS), developed by the Mutua Terrassa Functional Unit for Women with Schizophrenia, offers a structured intervention built around personalized care, health promotion, and social interaction [

23]. The program includes individual appointments that consider both pharmacological and social factors, group sessions focused on healthy habits, and community-linked activities that support environmental and social engagement [

23]. These interventions are organized into seven thematic “corners,” such as mindfulness, gynecological screening, green and blue space engagement, and digital health participation, each tailored to support different dimensions of well-being [

23]. The authors also propose that peer-to-peer and volunteer initiatives could help maintain the effectiveness of these interventions by reinforcing routine and strengthening social connectedness [

23].

Migration, especially under forced circumstances, is widely recognized as a significant social determinant of mental health [

40]. Refugees often endure pre-migration trauma, including war, persecution, and displacement, followed by post-migration stressors such as social isolation, economic hardship, and barriers to healthcare access [

40]. cumulative adversities place refugees at heightened risk for various psychiatric conditions, including psychosis [

40]. Previous research has consistently shown that immigrants and their descendants are at an elevated risk for schizophrenia and other non-affective psychotic disorders, but the extent to which refugee status compounds this risk has remained less clear [

40]. To address this gap, Hollander et al. [

40] conducted a large cohort study in Sweden involving 1.3 million individuals to examine whether refugees are at a greater risk of psychosis than non-refugee migrants and the native-born population [

40]Their findings revealed that refugees had a 2.9 times higher adjusted hazard ratio for psychosis than the Swedish-born population and a 1.7 times higher risk than non-refugee migrants, with male refugees showing particularly elevated rates [

40]. These results underscore the need for early, culturally sensitive mental health interventions tailored to the unique vulnerabilities of refugee populations [

40].

4.2. Ethical, Structural, and Clinical Challenges in Applying AI for Migrant Women with Schizophrenia

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into mental health care introduces significant ethical, structural, and clinical complexities, particularly when addressing the needs of migrant women with schizophrenia [

2]. These individuals often exist at the intersection of multiple vulnerabilities including trauma exposure, language barriers, cultural displacement, and systemic inequities, making the application of AI both promising and precarious. Recent literature highlights the multifaceted barriers that must be navigated to ensure the ethical and equitable implementation

4.2.1. Ethical Issues

These ethical concerns are particularly significant for individuals with schizophrenia, as Yoo et al.

[25] found that many patients felt alienated from the development and application of AI technologies used to predict relapse. Participants expressed that these systems often failed to reflect their lived realities, especially when models made predictions without patient input or the opportunity for contextual interpretation

[25]. Several individuals feared that AI-driven alerts could lead to automatic clinical responses, such as hospitalization, without their consent, undermining their sense of agency and trust in the mental health system. Others described a strong discomfort with being monitored by algorithms trained on their social media data, linking these systems to feelings of being surveilled, judged, or profiled

[25]. For patients with paranoia or persecutory delusions, a common feature of schizophrenia, such surveillance-related concerns were not just theoretical but could actively worsen symptoms or trigger psychological distress. Furthermore, participants highlighted that the use of opaque or non-personalized AI models could damage the therapeutic alliance between patients and providers, especially when predictions were shared without context or explanation. These findings point to the urgent need for transparency, contestability, and patient-centered design in the deployment of AI for mental health care

[25].

Pozzi et al.

[24] examined the ethical risks associated with the use of AI-based mental health technologies among vulnerable populations. These tools, such as chatbots delivering cognitive behavioral therapy, are often promoted as cost-effective solutions to address global shortages of mental health professionals

[24]. However, the authors argue that this technological approach may introduce a less visible form of harm: epistemic injustice, particularly participatory injustice, where users are excluded from meaningful engagement in knowledge construction and therapeutic dialogue

[24]. To illustrate this concern, the authors analyzed the case of

Karim, a chatbot deployed to provide mental health support to Syrian refugees. It was not marketed as a psychotherapeutic tool, but rather as a “friend”. The use of Karim in this context was not supervised by trained professionals, raising serious ethical concerns. Moreover, the refugees are not given participatory status in the development of the application. Instead, they were treated as mere test subjects with a limited role

[24]. Finally, the experiment imposed Western criteria on the use of psychotherapy in Middle Eastern populations. This, the authors argue, introduces an identity bias into the technology. The authors further highlight how culturally unresponsive design and limited user input can undermine the ethical goal of justice in mental health care, as it did in this case. As a response, they propose Capability Sensitive Design as a framework to enhance user participation and reduce epistemic harms in AI-driven interventions

[24].

Ethical concerns surrounding the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in schizophrenia care are deeply tied to issues of fairness, privacy, and individualized treatment [

41]. One major issue is that many AI systems are developed using datasets that lack sufficient diversity, particularly in terms of demographic and clinical representation. This can lead to biased predictions that fail to generalize across underrepresented populations, thereby reinforcing healthcare disparities [

41]. Privacy concerns are also critical, as AI in schizophrenia research often involves the use of highly sensitive neuroimaging data. Handling such data requires rigorous compliance with privacy laws like GDPR and HIPAA, which poses ethical challenges for institutions with limited resources [

41].These challenges are further amplified when patients may have cognitive impairments that limit their ability to provide fully informed consent for the use of their data in algorithmic systems.

In addition, there is growing concern that overdependence on AI-generated outputs could reduce the clinician’s role in interpreting and personalizing care. In complex psychiatric cases like schizophrenia, relying too heavily on automated tools without critical reflection may result in depersonalized treatment decisions that do not account for a patient’s lived experience [

41]. Finally, ethical questions of justice arise in terms of who benefits from these technologies. Advanced AI systems require robust computational infrastructure and consistent data quality, which are not always available in low-resource settings. As a result, disparities may widen between institutions that can implement AI effectively and those that cannot [

41].

4.2.2. Structural Challenges

Dual-country migrant mothers face significant structural challenges including poverty, lack of health coverage, social isolation, and restrictive immigration policies that heighten their vulnerability to mental health problems [

35]. These systemic inequities are mirrored in the design and implementation of artificial intelligence (AI) systems used in mental health care, as these technologies often reflect the biases embedded in the datasets on which they are trained [

2]. Artificial intelligence (AI) systems in mental health care are frequently developed using training datasets that lack sufficient representation of culturally and linguistically diverse populations [

38]. AI algorithms may inherit biases from the data they are trained on, which can result in disparities in diagnosis and treatment, particularly for different demographic groups. To ensure equitable care, efforts must be made to identify and reduce these biases in AI systems [

29]. Additionally, AI tools need to be culturally sensitive to effectively meet the needs of diverse populations, as a lack of cultural awareness can lead to misinterpretations of symptoms and inadequate interventions, especially for marginalized groups. While AI can offer valuable insights, it should not replace human expertise. Human professionals must remain involved in decision-making, especially for complex or high-risk cases, where AI is insufficient on its own [

29].

This structural gap undermines the applicability and equity of such technologies in clinical settings [

38]. A recent scoping review found that out of more than 22,000 machine learning based mental health studies, only 13 focused specifically on immigrants, refugees, or racial and ethnic minorities [

38]. The review further noted that many studies either failed to report racial or ethnic data or treated such demographic variables as marginal, limiting the models’ relevance for underrepresented communities. As a result, AI systems risk misclassifying symptoms or failing to capture culturally specific expressions of psychological distress, thereby reinforcing diagnostic inequities rather than addressing them [

38].

Artificial intelligence (AI) systems in mental health care often face structural limitations that hinder their effectiveness, particularly for diverse populations. One challenge is that these systems are trained on datasets that may not adequately reflect the complex, multidimensional realities of schizophrenia, including cultural and linguistic diversity, which can reduce diagnostic accuracy and treatment personalization [

2]. Moreover, while AI holds great promise for early detection and prognosis, overreliance on automated predictions without clinical oversight may compromise patient safety and erode trust in AI tools [

2]. These findings underscore how AI-driven care, when not accompanied by culturally responsive access strategies, risks privileging digitally connected users while leaving the most vulnerable underserved.

4.2.3. Clinical Limitations

Although AI-driven technologies are increasingly integrated into mental health care, they often fail to capture the lived realities of individuals with schizophrenia. Yoo et al.’s [

25] study primarily involved individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, including both men and women, who reported challenges in relating AI-generated relapse predictions to their personal experiences. These participants described the AI outputs as often irrelevant or emotionally unsettling, which contributed to mistrust toward the technology and complicated their clinical care. Many expressed discomforts with automated predictions that failed to consider their unique circumstances, raising concerns about depersonalization and a loss of agency during treatment [

25]. Complementing this, Al-Hamad et al. [

42] focused specifically on Syrian refugee women in Canada, highlighting how systemic healthcare structures often exclude the perspectives of marginalized patients. These women faced significant cultural and linguistic barriers, resulting in care that was frequently misaligned with their needs and experiences [

42].

One major challenge with AI-based diagnosis is the wide variation in how symptoms present among patients[

43]. This symptom diversity, along with the absence of well-defined biological markers, makes it difficult for AI systems to detect consistent diagnostic patterns [

43]. Another limitation arises from the overlap between schizophrenia and other mental health conditions such as schizoaffective and mood disorders. Because these disorders can have similar features, AI models may struggle to accurately distinguish between them, especially if they rely on rigid classification frameworks [

43]. Additionally, the effectiveness of AI depends on the quality of MRI data, which can be compromised when patients are unable to remain still during scanning. This is a particular concern in schizophrenia, where restlessness or cognitive symptoms may interfere with cooperation. Furthermore, the limited ability of fMRI to capture rapid changes in brain activity restricts its usefulness in real-time diagnostic support [

43].

Despite the remarkable potential of AI in improving schizophrenia diagnostics, its clinical application is hindered by several limitations [

41]. One of the primary challenges is the “black box” nature of many AI models, particularly deep learning algorithms, which lack transparency in how decisions are made, making them difficult for clinicians to interpret or trust in a healthcare setting [

41]. Additionally, the broad heterogeneity of schizophrenia presents a significant obstacle; since the disorder manifests in highly variable ways across individuals, AI systems often struggle to generalize beyond controlled research environments [

41].

While AI tools have advanced diagnostic accuracy, most current models remain limited in their ability to support therapeutic planning or provide actionable treatment guidance, thereby reducing their immediate clinical relevance [

41]. Moreover, integrating AI technologies into routine psychiatric practice poses logistical burdens. These include the need for substantial technical infrastructure, extensive clinician training, and navigation of regulatory pathways, all of which can delay implementation in real-world settings [

41].

Privacy and ethical concerns further complicate adoption, especially given the sensitivity of neuroimaging data used in AI training and analysis; ensuring compliance with data protection laws like GDPR and HIPAA requires significant institutional resources [

41]. Finally, there is a growing concern that clinicians may overly defer to AI-generated outputs in ambiguous cases, potentially compromising individualized care and diminishing the clinician’s role in nuanced diagnostic decision-making [

41].

4.3. The Role of AI Tools in Improving Care Access and Engagement for Migrant Women with Schizophrenia

AI technologies offer new ways to support migrant women with schizophrenia by addressing language, access, and personalization gaps in care

[2]. This section explores how AI can enhance mental health service delivery for this group while also recognizing the structural and ethical challenges that shape its effectiveness.

4.3.1. Improving Access to Culturally Sensitive Mental Health Care

AI is playing a crucial role in improving access to culturally sensitive mental health care. Hansen et al. [

22] highlight that machine learning models, utilizing data from electronic health records (EHRs), can help predict the progression to schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, facilitating early diagnosis and intervention. These models incorporate clinical notes, which capture patients’ personal experiences and symptoms, allowing for a more culturally sensitive approach to care [

22]. By analyzing these notes with natural language processing and deep learning, AI can uncover patterns that may signal the onset of mental health conditions [

22]. This approach ensures that interventions are timelier and more tailored, especially for marginalized populations [

22]. AI is increasingly integrated into everyday communication, including applications that support mental health management. Zúñiga et al. [

19] note that AI technologies, such as chatbots and conversational agents, help manage mental health by facilitating communication and emotional expression. These tools can also convey nonverbal cues, such as emojis, and help foster social connections, making them valuable for mental health support [

19].

AI tools have shown effectiveness in reducing language and access barriers through natural language processing (NLP), multilingual support, and asynchronous communication [

2]. Moreover, AI shows great promise in advancing new drug development. Its integration into psychiatry and fields such as pharmacology has notably enhanced treatment planning and monitoring, indicating that similar methods could support more individualized and real-time patient care systems [

2]AI enhances psychological treatments for schizophrenia (SZ), such as social cognitive training and computerized cognitive remediation therapy (CCRT), improving brain activity and cognitive abilities [

2]. Predictive models like random forest are effective in identifying high-response patients and tailoring treatments [

2]. AI optimizes therapies like repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) by predicting individual responses, improving treatment efficacy [

2]. Additionally, AI integrates biopsychosocial factors to deliver more personalized and effective care for SZ patients [

2].

The findings from Gellert et al. [

44] further support the promise of AI-enhanced care for displaced women. In their study of an AI-based virtual triage platform in Poland, Ukrainian refugee women representing 76.8% of the migrant users engaged with the system at disproportionately high rates, especially when using the Ukrainian language interface. These users reported significantly higher rates of anxiety, insomnia, and generalized anxiety disorder than Polish nationals. This suggests that culturally and linguistically attuned AI systems can effectively engage migrant women experiencing psychological distress aligning with the goals of this review to explore inclusive, scalable mental health tools for migrant women with schizophrenia [

44].

4.3.2. Enhancing Engagement Through Personalization and Monitoring

AI systems hold promise in improving mental health engagement by adapting interventions to individual experiences of migration, trauma, and family structure[

35]. Dual-country mothers, who parent across national borders, are particularly vulnerable to psychological distress due to the persistent emotional burden of prolonged separation from their children, feelings of guilt, and the tension created by conflicting cultural expectations surrounding maternal responsibility. These complex and intersecting stressors are often overlooked within conventional mental health frameworks, leading to inadequate recognition and support in standardized clinical models [

35].

AI tools, including machine learning models and natural language processing (NLP), can be trained to detect contextual risk factors through behavioral data, structured interviews, and language use [

45]. These tools are predominantly used for support, monitoring, and self-management, providing personalized alerts, referrals, or digital interventions tailored to individual needs. This type of tailored approach enhances therapeutic engagement, reduces wait times, and improves symptom tracking, ultimately fostering a stronger therapeutic alliance and helping to reduce dropout rates among individuals navigating complex mental health challenges [

45].

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have demonstrated significant potential in diagnosing schizophrenia through the use of neuroimaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [

43]. These AI-driven systems, including deep learning and machine learning models, are particularly valuable in identifying structural and functional abnormalities in the brain that might otherwise be challenging for clinicians to detect. By automating the analysis of MRI data, these AI tools provide more accurate, efficient, and reproducible results, which can complement traditional clinical evaluations and improve the diagnostic process [

43]. Further, González-Rodríguez et al. [

1] emphasize that migrant women with schizophrenia are often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed due to cultural misunderstandings, language barriers, and trauma-related masking of symptoms. Their review highlights how caregiving burdens and gendered trauma, such as experiences of sexual violence or forced family separation contribute not only to the onset of schizophrenia but also to sustained disengagement from clinical care.

Integrating these insights into AI algorithms can enhance the detection of high-risk cases by incorporating background variables that are often neglected by conventional systems [

29]. These advanced models could leverage diverse datasets, enabling the identification of subtle risk factors linked to cultural, socioeconomic, and familial contexts, which are typically overlooked in traditional diagnostic approaches [

29]. Furthermore, AI systems can be designed to deliver culturally appropriate psychoeducation and behavioral nudges tailored to the specific needs of patients, considering the complexities of cultural stigma and family obligations that often influence engagement with mental health services [

29]. For example, AI-powered platforms could deliver personalized interventions that are sensitive to the unique stressors experienced by individuals from different cultural backgrounds, ensuring that the support provided is not only relevant but also accessible in a manner that respects cultural norms. These personalized, culturally aware AI solutions could play a critical role in maintaining consistent patient engagement by offering real-time feedback and continuous support, which is particularly vital for populations with a history of treatment disengagement due to cultural barriers or stigma [

29]. Together, these studies point to the need for AI systems that do not merely automate clinical tasks but actively adapt to the lived experiences of marginalized patients.

4.3.4. Challenges and Partial Effectiveness

While artificial intelligence (AI) offers significant potential for improving the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia, several limitations hinder its full clinical implementation. One of the core challenges lies in the nature of psychiatric disorders themselves, which typically lack clear biological markers unlike other medical conditions making it difficult for AI systems to accurately detect and classify symptoms through imaging techniques [

2]. Additionally, the heterogeneity of schizophrenia, with its widely varying symptom patterns and progression trajectories, complicates the development of standardized models for individualized diagnosis and treatment [

2]. Current diagnostic systems, such as the DSM-5 and ICD, are primarily symptom-based and rely heavily on clinical interpretation rather than objective measures, further limiting the utility of AI tools that require structured input data [

2]. Moreover, some deep learning models, particularly traditional multilayer perceptrons, are constrained by their need for large datasets and their lack of interpretability, raising concerns about transparency and clinical trust [

2]. This is demonstrated by Shoeibi et al.’s [

2] study. The EEG datasets that were available for schizophrenia diagnosis in that study were limited in size, which makes it difficult to develop and access effective deep learning tools for this application [

46]. Additionally, the dataset used by the authors was designed for diagnosis only and did not assess the severity of the disorder. However, among the various deep learning and machine learning methods they evaluated, the 13-layer CNN-LSTM models demonstrated the highest accuracy and efficiency [

46]. Jiang et al. [

2] also emphasize that relying on a single data source, such as MRI, may reduce diagnostic accuracy, and advocate for multimodal integration of behavioral, genetic, and neurophysiological data to enhance predictive reliability. Finally, while AI can augment psychiatric care, it is not a substitute for human expertise; clinicians' judgment and empathy remain indispensable components of effective schizophrenia treatment [

2].

Migrant women with schizophrenia often experience misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis due to cultural misunderstandings, trauma experienced before and during migration, and language barriers [

1]. Gender-specific stressors, such as exposure to sexual violence, forced migration, and caregiving under economic hardship, intensify these challenges and contribute to ongoing disengagement from mental health care. Additionally, stigma and fear of institutional exposure particularly affect undocumented women, hindering their willingness to seek help. These findings highlight the importance of developing AI systems that are trauma-informed and culturally sensitive rather than relying solely on standard psychiatric criteria [

1].

5. Limitations of the Current Review

This narrative review offers an integrative perspective on the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) in supporting migrant women with schizophrenia. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the review relies exclusively on peer-reviewed articles published in English between 2010 and 2025, which may exclude valuable insights from non-English or gray literature, including NGO reports and community-based initiatives, particularly from low- and middle-income countries. As a result, the findings may reflect a bias toward Global North perspectives and technological environments.

Second, while the review emphasizes cultural and gender responsiveness, most of the studies included do not directly examine AI interventions developed specifically for migrant women with schizophrenia. Many findings are extrapolated from general AI or schizophrenia research, or from studies on migrant women with other mental health concerns. This limits the specificity and transferability of the conclusions drawn, especially given the intersectional nature of schizophrenia, gender, and migration experiences.

Third, the narrative design of this review, while suitable for capturing emerging themes and diverse contexts, does not follow a systematic meta-analytic approach. This may introduce interpretive bias, particularly in the thematic synthesis process. Although efforts were made to ensure methodological rigor through the SANRA scale and PRISMA-ScR flowchart, the inclusion criteria relied on author judgment, which can affect replicability.

Finally, technological advancements in AI are evolving rapidly, and several studies referenced are conceptual or based on pilot programs without long-term evaluation. The absence of robust empirical trials and longitudinal data on the effectiveness, safety, and user trust of AI tools limits the evidence base supporting AI applications in this high-risk population. Future research must address these gaps through participatory design, intersectional data frameworks, and evaluation in diverse real-world settings.

6. Suggestions for Future Research

Future research should focus on developing AI tools that are specifically tailored to the needs of migrant women with schizophrenia. Current technologies are often generalized and do not adequately capture the intersection of migration, gender, culture, and psychosis. There is a pressing need to co-design these tools in collaboration with the target population to ensure cultural sensitivity, emotional safety, and usability.

Studies should also move beyond theoretical models and short-term pilots to include longitudinal and real-world evaluations. These should assess not only clinical outcomes but also levels of trust, user satisfaction, and long-term engagement with AI tools. Including a diverse range of cultural and migration backgrounds in these studies will improve the generalizability and inclusivity of findings.

In addition, future research must address the lack of culturally representative training data in existing AI models. Expanding datasets to reflect non-Western expressions of mental illness, such as somatic symptoms or idiomatic language, will enhance diagnostic accuracy and reduce bias. Research should explore how AI can adapt to context-specific expressions of distress without misinterpretation or over-pathologization.

There is also a need to investigate how trauma-informed and gender-responsive design principles can be integrated into AI-based interventions. Factors such as reproductive history, caregiving roles, and experiences of forced migration or violence should be considered when creating personalized support systems.

Lastly, future research should examine how AI can be embedded within hybrid care models, where digital tools support but do not replace human relationships. Integrating AI with therapeutic communities, peer support structures, and culturally safe care environments may offer a more holistic and sustainable approach for addressing the complex mental health needs of migrant women with schizophrenia.

7. Conclusions

Artificial intelligence (AI) offers transformative potential for enhancing mental health care among marginalized populations, including migrant women with schizophrenia, who face unique cultural, linguistic, and systemic challenges. This narrative review has critically examined how AI tools can address these complexities, focusing on culturally responsive care, ethical and structural barriers, and improvements in care access and engagement. Findings suggest that while AI holds significant promise, its current application remains underdeveloped. AI tools show potential in providing culturally responsive care through natural language processing and culturally adaptive frameworks; however, these developments are not yet sufficiently tailored to the specific needs of migrant women with schizophrenia. Ethical and structural challenges, such as algorithmic bias, lack of participatory design, and the misalignment of AI tools with the sociocultural context of migrant populations, have been widely discussed. Yet, there remains a lack of concrete, tested solutions to address these issues. Concerning care access and engagement, AI tools have demonstrated some success in increasing engagement through multilingual support and personalized platforms, but the evidence is preliminary and inconsistent, with no conclusive, long-term validation.

In sum, while the three research questions are addressed in the existing literature, AI’s capacity to offer culturally responsive care, the ethical and structural barriers to its implementation, and its effectiveness in improving access and engagement – the evidence remains inconclusive and the challenges substantial. The field will require participatory, intersectional, and longitudinal research to develop ethically grounded, culturally responsive AI systems capable of achieving real-world efficacy and sustainability.

References

- González-Rodríguez, A.; Palacios-Hernández, B.; Natividad, M.; Susser, L.C.; Cobo, J.; Rial, E.; et al. Incorporating Evidence of Migrant Women with Schizophrenia into a Women’s Clinic. Women. 2024, 4, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Jia, Q.; Peng, Z.; Zhou, Q.; An, Z.; Chen, J.; et al. Can artificial intelligence be the future solution to the enormous challenges and suffering caused by Schizophrenia? Vol. 11, Schizophrenia. Nature Research; 2025.

- Tandon, R.; Gaebel, W.; Barch, D.M.; Bustillo, J.; Gur, R.E.; Heckers, S.; et al. Definition and description of schizophrenia in the DSM-5. Schizophrenia Research. 2013, 150, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H.Y.; Teoh, S.L.; Wu, D.B.C.; Kotirum, S.; Chiou, C.F.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Global economic burden of schizophrenia: A systematic review. Vol. 12, Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. Dove Medical Press Ltd; 2016. p. 357–73.

- Weber S, Scott JG, Chatterton M Lou. Healthcare costs and resource use associated with negative symptoms of schizophrenia: A systematic literature review. Schizophrenia Research. 2022, 241, 251–259.

- Kotzeva, A.; Mittal, D.; Desai, S.; Judge, D.; Samanta, K. Socioeconomic burden of schizophrenia: a targeted literature review of types of costs and associated drivers across 10 countries. Journal of Medical Economics. Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 2023, 26, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, M.J.; O’Donovan, M.C. Schizophrenia and the neurodevelopmental continuum:evidence from genomics. World Psychiatry. 2017, 16, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablensky, A. The diagnostic concept of schizophrenia: its history, evolution, and future prospects [Internet]. Vol. 12, Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010. Available from: www.dialogues-cns.

- Simeone, J.C.; Ward, A.J.; Rotella, P.; Collins, J.; Windisch, R. An evaluation of variation in published estimates of schizophrenia prevalence from 1990-2013: A systematic literature review. BMC Psychiatry. 2015, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maureen O’Mahony, J.; Truong Donnelly, T. A postcolonial feminist perspective inquiry into immigrant women’s mental health care experiences. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2010, 31, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.E.; Lenette, C.; Brough, M.; Reid, K.; Correa-Velez, I.; Vromans, L.; et al. The Importance of Local and Global Social Ties for the Mental Health and Well-Being of Recently Resettled Refugee-Background Women in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, T.T.; Hwang, J.J.; Este, D.; Ewashen, C.; Adair, C.; Clinton, M. If i was going to kill myself, i Wouldn’t be calling you. i am asking for help: Challenges influencing immigrant and refugee women’s mental health. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011, 32, 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.J.; Jang, Y.; Ko, J.E.; Lee, S.H.; Moon, S.K. Perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms: a study of Vietnamese women who migrated to South Korea due to marriage. Women Health. 2020, 60, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Ahmed, S.R.; Hauson, A.O.; Al-Delaimy, W.K. The Relationship Between Acculturative Stress and Postmigration Mental Health in Iraqi Refugee Women Resettled in San Diego, California. Community Ment Health J. 2021, 57, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, J.K.; Jesuthasan, J.; Schalinski, I.; Kurmeyer, C.; Oertelt-Prigione, S.; Abels, I.; et al. Traumatic Life Events and Association with Depression, Anxiety, and Somatization Symptoms in Female Refugees. JAMA Netw Open. 2023, 6, E2324511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vromans, L.; Schweitzer, R.D.; Brough, M.; Asic Kobe, M.; Correa-Velez, I.; Farrell, L.; et al. Persistent psychological distress in resettled refugee women-at-risk at one-year follow-up: Contributions of trauma, post-migration problems, loss, and trust. Transcult Psychiatry. 2021, 58, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngameni, E.G.; Moro, M.R.; Kokou-Kpolou, C.K.; Radjack, R.; Dozio, E.; El Husseini, M. An Examination of the Impact of Psychosocial Factors on Mother-to-Child Trauma Transmission in Post-Migration Contexts Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Child Care in Practice. 2024, 30, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, E.E.; Shafner, L.; Walling, D.P.; Othman, A.A.; Chuang-Stein, C.; Hinkle, J.; et al. Use of a novel artificial intelligence platform on mobile devices to assess dosing compliance in a phase 2 clinical trial in subjects with schizophrenia. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil de Zúñiga, H.; Goyanes, M.; Durotoye, T. A Scholarly Definition of Artificial Intelligence (AI): Advancing AI as a Conceptual Framework in Communication Research. Vol. 41, Political Communication. Routledge; 2024. p. 317–34.

- Weizenbaum, J. ELIZA—a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Commun ACM. 1966, 9, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, D.B.; Falkai, P.; Koutsouleris, N. Machine Learning Approaches for Clinical Psychology and Psychiatry. 2025, Available from, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, L.; Bernstorff, M.; Enevoldsen, K.; Kolding, S.; Damgaard, J.G.; Perfalk, E.; et al. Predicting Diagnostic Progression to Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder via Machine Learning. JAMA Psychiatry. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Natividad, M.; Chávez, M.E.; Balagué, A.; Paolini, J.P.; Picó, P.; Hernández, R.; et al. Community Therapeutic Space for Women with Schizophrenia: A New Innovative Approach for Health and Social Recovery. Women. 2025, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, G.; De Proost, M. Keeping an AI on the mental health of vulnerable populations: reflections on the potential for participatory injustice. AI and Ethics. 2025, 5, 2281–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.W.; Woo, H.; Nguyen, V.C.; Birnbaum, M.L.; Kruzan, K.P.; Kim, J.G.; et al. Patient Perspectives on AI-Driven Predictions of Schizophrenia Relapses: Understanding Concerns and Opportunities for Self-Care and Treatment. In: Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings. Association for Computing Machinery; 2024.

- Sukhera, J. Narrative Reviews: Flexible, Rigorous, and Practical. J Grad Med Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. American College of Physicians 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, A.; Gupta, A.; De Sousa, A. Artificial intelligence in positive mental health: a narrative review. Vol. 6, Frontiers in Digital Health. Frontiers Media SA; 2024.

- Lin, Y.; Ding, H.; Zhang, Y. Emotional prosody processing in schizophrenic patients: A selective review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Moshe, T.; Ziv, I.; Dershowitz, N.; Bar, K. The contribution of prosody to machine classification of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia. 2024, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.S.; Cox, C.R.; Le, T.P.; Cowan, T.; Masucci, M.D.; Strauss, G.P.; et al. Using machine learning of computerized vocal expression to measure blunted vocal affect and alogia. NPJ Schizophr. 2020, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazur, M.; Krukow, P. The Significance of Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning in Schizophasia Description. Identification of Research Trends and Perspectives in Schizophrenia Language Studies. Current Problems of Psychiatry. 2024, 25, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Z.; Qu, W.; Du, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Hearing vocals to recognize schizophrenia: speech discriminant analysis with fusion of emotions and features based on deep learning. BMC Psychiatry. 2025, 25, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouris, S.S.; Merry, L.A.; Kebe, A.; Gagnon, A.J. Mothering Here and Mothering There: International Migration and Postbirth Mental Health. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012, 2012, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, M.V. Schizophrenia Psychosis in Women. Women. 2020, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaduaka, U.S.; Oladosu, A.O.; Katsande, S.; Frempong, C.S.; Awuku-Amador, S. Leveraging artificial intelligence in the prediction, diagnosis and treatment of depression and anxiety among perinatal women in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. BMJ Mental Health. BMJ Publishing Group 2025, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.K.; Saleem, M.; Al-Garadi, M.A.; Ahmed, A. Machine learning applications in studying mental health among immigrants and racial and ethnic minorities: an exploratory scoping review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2024, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, R.D.; Vromans, L.; Brough, M.; Asic-Kobe, M.; Correa-Velez, I.; Murray, K.; et al. Recently resettled refugee women-at-risk in Australia evidence high levels of psychiatric symptoms: Individual, trauma and post-migration factors predict outcomes. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollander, A.C.; Dal, H.; Lewis, G.; Magnusson, C.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Dalman, C. Refugee migration and risk of schizophrenia and other non-affective psychoses: Cohort study of 1. 3 million people in Sweden. BMJ (Online). 2016, 15, 352. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano, V.; D’Angelo, M.; Monaco, F.; Vignapiano, A.; Martiadis, V.; Barone, E.; et al. Decoding Schizophrenia: How AI-Enhanced fMRI Unlocks New Pathways for Precision Psychiatry. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hamad, A.; Forchuk, C.; Oudshoorn, A.; Mckinley, G.P. Listening to the Voices of Syrian Refugee Women in Canada: an Ethnographic Insight into the Journey from Trauma to Adaptation. J Int Migr Integr. 2023, 24, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, D.; Shoeibi, A.; Ghassemi, N.; Moridian, P.; Khadem, A.; Alizadehsani, R.; et al. An overview of artificial intelligence techniques for diagnosis of Schizophrenia based on magnetic resonance imaging modalities: Methods, challenges, and future works. Vol. 146, Computers in Biology and Medicine. Elsevier Ltd; 2022.