1. Introduction

Studies on insect-plant interactions have traditionally focused on key topics such as insect feeding, oviposition, and their effects on plants, as well as plant responses aimed at avoiding insect herbivory through diverse defense strategies (Schoonhoven et al., 2005). When insects feed or oviposit they transfer a variety of molecular patterns, serving as herbivore-associated signals that modulate plant responses to insect herbivores (Rondoni et al., 2018; Erb and Reymond, 2019; Mostafa et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2024). However, sap-sucking herbivores like, aphids, whiteflies, scale insects, mealybugs, planthoppers, and leafhoppers (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha and several Auchenorrhyncha) not only damage plants directly through feeding punctures with injection of saliva and indirectly by transmitting plant viruses (Whitfield et al., 2015), but they also influence plant ecology, physiology and health through the release of honeydew (Nelson and Mooney, 2022; de Bobadilla et al., 2024).

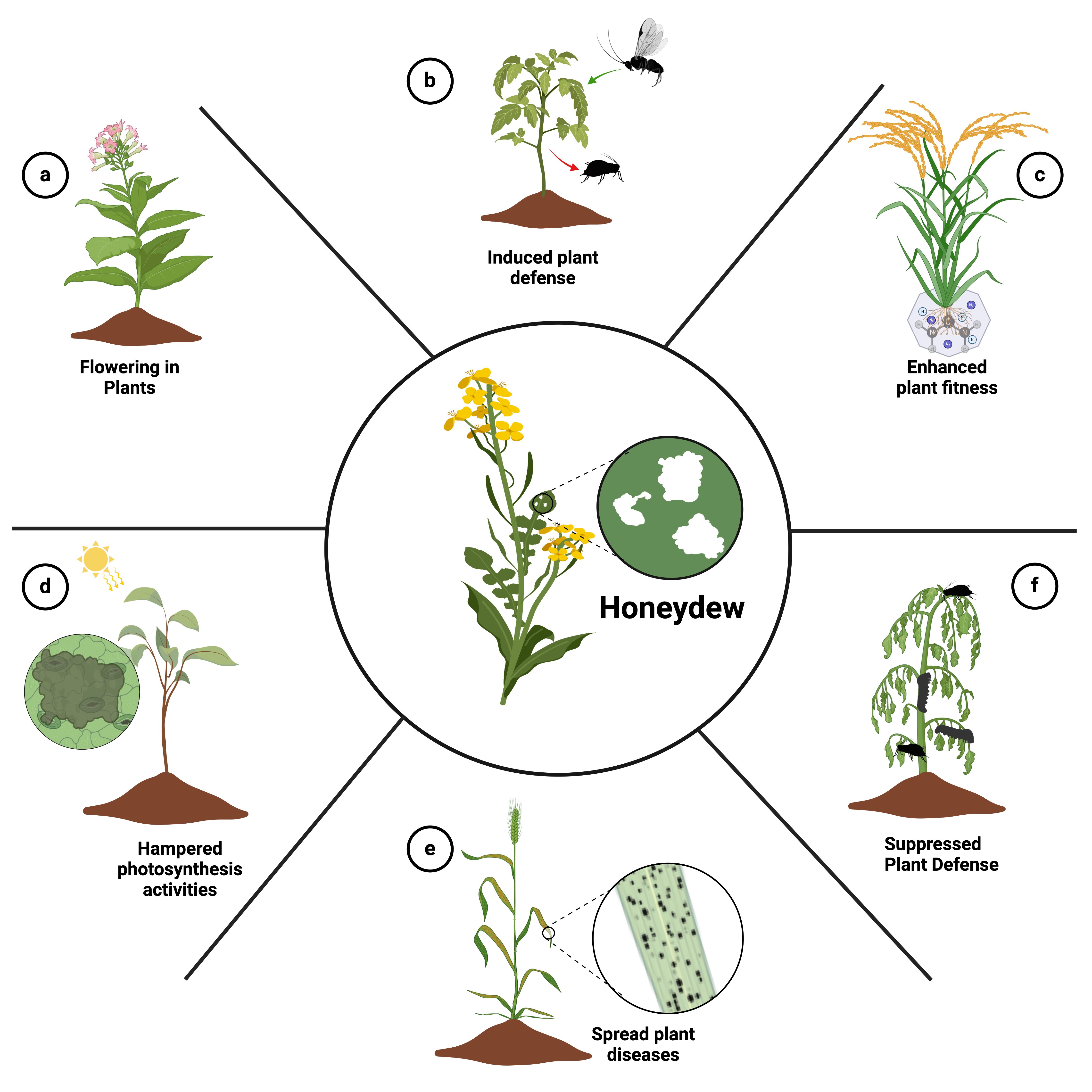

Honeydew, a sugary excretion emitted via anal opening by sap-sucking insects, interacts with plants in various ways, exhibiting both negative and positive effects (

Figure 1). Often overlooked, honeydew acts as a important substance, influencing plant health and affecting responses between insects and plants. The composition and quantity of honeydew are influenced by various ecological factors, including the insect species involved, the plant species involved, the nutritional quality of plant sap, and environmental conditions (Fischer and Shingleton, 2001; Schillewaert et al., 2017; Blanchard et al., 2022). Beyond its role as waste, honeydew has ecological importance that extends to various aspects of the ecosystem. This sticky substance serves as a nutrient source for a many organisms, including parasitic Hymenoptera (Buitenhuis et al., 2004; Tena et al., 2016; van Neerbos et al., 2020; Colazza et al., 2023), insect predators (Rondoni et al., 2018) ants (Nelson and Mooney 2022) and microorganisms (Álvarez-Pérez et al., 2024). The microbial communities thriving in honeydew, in turn, contribute to the broader ecological landscape (van Neerbos et al., 2020; Colazza et al., 2023). Recognising honeydew as a vital substance with a significant impact on plant physiology, including reproduction and health, opens the door to understanding its complex contributions to ecological processes (Owen and Wiegert, 1976; Tena et al., 2016; Álvarez-Pérez et al., 2024). Additionally, the excretion of honeydew droplets gives the plant a chance to recognise insect herbivores (VanDoorn et al., 2015). Thus, honeydew represents another potential source of herbivore associated molecular patterns (HAMPs); however, this area has not been studied in detail yet (Wari et al., 2019).

Exploring the dual impact of honeydew on plant physiology, we evaluate both its negative and positive aspects. A negative effect of honeydew interactions with plants is that it creates an environment conducive to microbial pathogens, potentially escalating instances of plant health issues (Wari et al., 2019). Moreover, the deposition of honeydew and consequent development of fungi (sooty moulds) on leaf surfaces holds the potential to impede photosynthetic activities due to surface coverage (Nelson, 2008; Chomnunti et al., 2014). However, honeydew also plays a role in plant defenses, exerting both suppressive and inductive effects (Schwartzberg and Tumlinson, 2014). Additionally, it has been linked to flowering regulation, though this remains largely unexplored (Cleland, 1974). Studies further suggest that honeydew can enhance soil fertility, contributing to improved plant health (Owen and Wiegert, 1976; Buckley, 1987).

Moreover, studies explore the release of volatile compounds from honeydew and its kairomonal activities, as well as its significance in recruiting biocontrol agents and managing pests (Leroy et al., 2014). Notably, while the effects of honeydew on plant defense have been partially explored, its impact on other aspects of plants remains an underexplored field (Leroy et al., 2011; Schwartzberg and Tumlinson, 2014; Wari et al., 2019). A limited number of studies from almost five decades ago briefly touched upon honeydew’s role in plant flowering, with no subsequent research in that direction (Cleland, 1974; Cleland and Ajami, 1974). Similarly, poorly explored topics include honeydew’s potential contributions to plant disease, its role in enhancing secondary infections through the proliferation of microbial pathogens, the consequences of its deposition on leaf surfaces, and its effects on the photosynthetic activity of plant Here, we highlight the least explored areas, pointing out the gaps in our current understanding and suggesting potential directions for future research and practical applications of honeydew in ecological practices. These include strategies like integrated pest management, where honeydew could support biological control agents, as well as enhancing pollination and promoting biodiversity conservation through the attraction of beneficial insects. In this review, we focus on a structured analysis, examining the complex interaction between honeydew composition, regulatory mechanisms, and plant-related factors. We investigate the detrimental effects of honeydew deposition on plant surfaces, such as challenges posed by the proliferation of sooty moulds and microbes, ultimately affecting photosynthetic activities by covering the plant surface. We also explore the consequences of the honeydew-plant relationship in agricultural settings. Our exploration of the positive effects of honeydew on plants includes improved flowering, strengthened direct and indirect defence mechanisms, and an indirect yet important impact on soil fertility, boosting overall plant health.

2. Origin and Composition of Honeydew

Honeydew is a sugary excretion produced by various hemipteran insects, including aphids (Aphididae), whiteflies (Aleyrodidae), mealybugs (Pseudococcidae), scale insects (Coccidae), psyllids (Pysillidae), leafhoppers (Cicadellidae), treehoppers (Membracidae) and froghoppers (Cercopidae). These insects feed on plant sap using their specialised mouthparts to pierce plant tissues and extract phloem and/or xylem sap. While most honeydew-excreting insects primarily feed on phloem (suborder Sternorrhyncha), leafhoppers, treehoppers, and froghoppers (suborder Auchenorrhyncha) are mainly xylem sap feeders (Lt and Rodriguez, 1985; Byrne and Bellows Jr, 1991; Dietrich, 2009; Hodkinson, 2009; Weintraub, 2009; Van Emden and Harrington, 2017; Nelson and Mooney, 2022; de Bobadilla et al., 2024) .

Phloem sap is rich in sugars and other nutrients but lacks sufficient amino acids for the insects’ needs. After ingestion, the sap undergoes processing within the insect’s digestive system. Surplus sugars and other non-essential components are then excreted as honeydew (waste). This process allows the insects to concentrate the essential amino acids and nutrients while eliminating excess sugars. Honeydew may also contain secondary plant compounds or even unmetabolised residues of systemic insecticides, depending on the insect’s diet and environment (Molyneux et al., 1990; Fischer and Shingleton, 2001; Tena et al., 2016; Calvo-Agudo et al., 2020; Quesada et al., 2020; Shaaban et al., 2020; Starr, 2021; Álvarez-Pérez et al., 2023).

Honeydew, in addition to sugars, contains a range of amino acids and various proteins from both the insect host and its microbiota (Molyneux et al., 1990; Douglas, 2009; Dhami et al., 2011; Sabri et al., 2013). For example, the honeydew of the pineapple mealybug (Dysmicoccus brevipes) comprises up to 98% carbohydrates, including 55% cane sugar, 25% invert sugar, and 13.9% dextrin, along with amino acids (Auclair, 1963; Dhami et al., 2011; Shaaban et al., 2020).

The sugars found in honeydew, such as melezitose, erlose, raffinose, trehalose, and trehalulose, are produced through the action of gut enzyme derived from plants within insects (Hendrix, Wei and Leggett, 1992; Wäckers, 2000). The composition and quantity of sugars present in honeydew can vary depending upon the insect species, the host plants, plant-rhizobia interactions, host plant infection by pathogens, and environmental conditions (

Table 1) (Fischer and Shingleton, 2001; Fischer et al., 2002; Hogervorst et al., 2007; Tena et al., 2013; Hijaz et al., 2016; Blanchard et al., 2022). For instance, aphids like

Metopeurum fuscoviride and

Cinara spp. (Hemiptera: Aphididae) produce honeydew rich in melezitose, while others like

Macrosiphoniella tanacetaria and

Macrosiphum euphorbiae produce minimal amounts of this sugar (Hendrix et al., 1992; Völkl et al., 1999). The age of aphids significantly influences honeydew production, with sugar concentration remaining stable while amino acid levels increase as the aphids age (Fischer et al., 2002). Honeydew composition varies not only among different insect species on the same host plant but also among different host plants for the same insect species (Schillewaert et al., 2017).The production of honeydew is a complex process and also the quantity produced is influenced by various factors. Certain species release more honeydew than their own body weight on an hourly basis, and this process is affected by factors such as insect age, size, species, seasonal and geographical location of the host plant, diurnal shifts, climate, plant-rhizobia interactions and host plant infection by pathogens (Hertel and Kunkel, 1977; Hendrix et al., 1992; Douglas, 1993, 2009; Fischer and Shingleton, 2001; Fischer et al., 2002; Wool et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2012; Whitaker et al., 2014; Hijaz et al., 2016; Blanchard et al., 2022). A comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing honeydew composition and quantity is crucial for elucidating the broader implications of its production, thereby illuminating the complex relationship between honeydew and plant biochemistry, and consequently, the resultant composition of honeydew (Fischer et al., 2005; Douglas, 2009; Dhami et al., 2011; Hijaz et al., 2016).

3. Negative Effects of Honeydew on Plants

Honeydew introduces negative physiological and ecological impact on plants and can compromise their fitness. This section explores the adverse effects of honeydew on plants, categorising them into distinct dimensions.

3.1. Impact on Photosynthetic Activity and Pollination

The excretion of honeydew by hemipteran sap-feeding insects poses a detrimental impact on plant physiology. The honeydew accumulation on foliage and stems provides a conducive environment for the growth of epiphytic fungi (sooty moulds). Sooty moulds, with its black and dense nature, hinders photosynthesis by blocking essential light on leaf surfaces, leading to a theoretical cessation of photosynthesis and subsequent starvation of plant tissues (Crawford, 1921; Nelson, 2008; Chomnunti et al., 2014). Not only sooty moulds but the presence of honeydew itself may impede the efficiency of photosynthetic activities, potentially leading to reduced plant productivity and growth. For instance, winter wheat experiences adverse effects due to honeydew application. Rabbinge et al. (1981) observed a decrease in the maximum rates of photosynthesis in wheat flag leaves one day and one week after honeydew application in a controlled environment. The immediate reduction in photosynthesis was attributed to hindered gas exchange caused by stomatal clogging. For the long-term impact, honeydew was linked to accelerated leaf senescence, negatively affecting leaf photosynthesis (Vereijken, 1979; Rabbinge et al., 1981). Honeydew promotes the growth of perthotrophic fungi, which form a layer on the leaf surface. This fungal layer interferes with the leaf’s gas exchange processes, leading to a reduction in maximum photosynthesis rates (Dik, 1990). In maize, heavily honeydew-coated tassels and/or silks can lead to disrupted pollination, consequently causing yield losses. The occurrence of excessive honeydew on maize ears can lead to them becoming visually unattractive and unsuitable for the market (Carena and Glogoza, 2004; Edde, 2022), as also happens with other agricultural products. Moreover, the invasive mealybug Pseudococcus comstocki (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) exacerbates the situation by causing severe damage to apples, pears, and peaches in Italy through honeydew-fuelled sooty mould outbreaks, adversely impacting agricultural productivity (Pellizzari et al., 2012).

3.2. Making Plant Surface Prone for Pathogens

Honeydew serves as a breeding ground for microbial pathogens, creating conditions that promote plant infections and diseases. Its deposition on plant surfaces is often linked to the growth of fungal pathogens and saprophytes on plant leaves (Fokkema et al., 1983). However, beyond facilitating pathogen facilitation, honeydew can also provide insights into plant resistance mechanisms. For instance, Fujita et al., (2013) reported that honeydew from plant hoppers feeding on resistant Oryza lines contained higher levels of cholesterol and beta-sitosterol, which act as feeding deterrents. This suggests that honeydew composition can reflect biochemical differences between resistant and susceptible plants, influencing pest feeding behaviour.

Aphid honeydew enhances wheat leaf infection by necrotrophic pathogens like Septoria nodorum and Cochliobolus sativus, increasing spore germination rates 2.5 to 4 times by stimulating the formation of multiple germ tubes per conidium and promoting overall germ-tube growth during C. sativus’ pre-penetration phase (Fokkema et al., 1983). Its nutrient-rich composition enhances fungal growth and aggressiveness by promoting cell wall-degrading enzymes, facilitating the infection process. Conversely, the presence of aphid honeydew on wheat leaves significantly increases the colonisation of various saprophytic fungi such as Sporobolomyces roseus, Cryptococcus laurentii var. flavescens, Aureobasidium pullulans, and Cladosporium cladosporioides, with their population densities increasing tenfold within about six days (Fokkema et al., 1983). While honeydew stimulates both saprophytic and pathogenic fungi, competition between these groups can influence plant health. In some cases, rapid saprophyte growth depletes nutrients, limiting pathogen proliferation and potentially reducing infection rates. However, in controlled experiments, honeydew’s stimulatory effects on pathogens are more pronounced than in field conditions, likely due to complex microbial interactions on leaf surfaces (Fokkema et al., 1983). Beyond promoting pathogen growth, honeydew reduces fungicide efficacy against necrotrophic pathogens in wheat (Rabbinge et al., 1984; Dik and Van Pelt, 1992). Field studies indicate that honeydew interferes with fungicidal activity, particularly when broad-spectrum fungicides suppress natural saprophytes. In the absence of saprophytes, honeydew creates conditions that allow pathogens to thrive despite fungicidal treatments (Dik and Van Pelt, 1992). This effect is especially pronounced in pathogens with short latent periods, such as S. nodorum, which rapidly exploit honeydew’s nutrient availability (Dik and Van Pelt, 1992). Unconsumed honeydew also serves as a substrate for soil microorganisms (Lazzari and Zonta-de-Carvalho, 2012). In New Zealand, honeydew from the passion-vine hopper (Scolypopa australis, Hemiptera: Ricaniidae) contributes to up to 85% of kiwifruit losses (Tomkins et al., 2000). Similarly, the date palm hopper (Ommatissus lybicus, Hemiptera: Tropiduchidae) can cause up to 50% yield losses in date crops, with honeydew-induced sooty mold further reducing photosynthesis and weakening plant health (Shah et al., 2016).

3.3. Suppression of Plant Defences

The dynamic interaction between honeydew and plants encompasses various aspects, one of which is its negative impact on the plant’s defense system. The composition of insect honeydew is remarkably complex, encompassing a diverse array of proteins from insects, plants, and microbes. These components have the potential to shape various interactions within plant-insect-microbe systems. VanDoorn et al. (2015), demonstrated that honeydew application on tomato plant leaves alters in phytohormonal signalling. This discovery implies a potential mechanism through which honeydew may weaken plant defences. The underlying reason for honeydew’s suppression of plant defences lies in the crosstalk between the salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) pathways induced by aphid honeydew (Schwartzberg and Tumlinson, 2014). Specifically, the study highlights how honeydew application leads to the inhibition of wound-induced JA accumulation, thereby impairing the plant’s ability to respond effectively to damage. This effect is primarily attributed to the presence of SA in aphid honeydew, which induces SA within the leaf tissue rather than accumulating from exogenous application (VanDoorn et al., 2015).

Additionally, honeydew contains biologically active constituents such as sugars and sugar conjugates, which may influence plant defence responses (Schwartzberg and Tumlinson, 2014). Pea aphid honeydew is composed of various sugars, including fructose, glucose, sucrose, and trehalose, the latter of which has been implicated in regulating wound- and pathogen-related gene expression (Bae et al., 2005; Douglas, 2006). Furthermore, approximately half of the SA in honeydew exists in a conjugated form, which may contribute to SA accumulation in plants (Klick and Herrmann, 1988). The presence of bacteria in honeydew may also play a role, as bacterial flagellin has been shown to induce systemic acquired resistance (SAR) in plants (Zipfel et al., 2004). Despite these important findings, this area remains understudied. Interestingly honeydew produced as result of infection by the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea is a microorganism from different domain contains pathogenesis-related enzymes such as CatD, an extracellular catalase This enzyme is thought play role in pathogenicity and suppression of plant defence mechanisms (Garre et al., 1998). Therefore, further research is needed to comprehensively understand the specific mechanisms and compounds not only associated with sucking insects but also with honeydew produced by other organisms that may suppress plant defence.

4. Positive Effects of Honeydew on Plants

Honeydew, while showing negative impact on plants, also offers various benefits.

4.1. Regulation of Flowering in Plants

A crucial interaction highlighting the positive effects of honeydew on plants lies in its potential role in regulating flowering. In a study conducted by Cleland, (1974), extracts of honeydew collected from aphid Dactynotus ambrosiae, feeding on both vegetative and flowering Xanthium, was investigated. Notably, fractions from this honeydew were introduced into the culture medium for Lemna gibba plants, showcasing a function that suggests at honeydew’s impact extends beyond its conventional role. Furthermore, Cleland and Ajami (1974) found salicylic acid (SA) in the phloem of Xanthium plants, derived from both plant material and aphid honeydew. While SA in honeydew primarily exists in a free form, Xanthium hosts it predominantly in a bound state, likely as a glycoside. This nuanced interaction suggests a sophisticated interplay between honeydew composition and the complex regulatory mechanisms within the plant. The incorporation of honeydew fractions into the culture medium for L. gibba raises intriguing questions about how honeydew components, potentially including SA, may contribute to signalling pathways involved in the regulation of flowering (Cleland, 1974). This underlines one layer of the positive impact of honeydew on plants, emphasising its role in influencing key physiological processes, such as flowering regulation.

4.2. Induction of Plant Defences

The dynamic interaction between honeydew and plants encompasses various aspects, one of which is its impact on the plant’s defence system. This influence can be categorised into several dimensions. To begin with, Schwartzberg and Tumlinson (2014) reported honeydew’s manipulative role in as a potent plant defense elicitor by inducing plant defenses primarily through converting SA levels into a less active form glycoside form, salicylic acid glycoside (SAG), which can still induce a defense response without triggering an immediate strong reaction. Moreover, honeydew excreted by the brown plant hopper (BPH) Nilaparvata lugens (Hemiptera: Delphacidae)) was found to elicit both direct and indirect defences in rice plants (Wari et al., 2019). This effect was attributed to the accumulation of phytoalexins in the leaves and the release of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Additionally, it activates defence-related genes (PR1 and PRP6, PR10), prompting the synthesis of defensive compounds, including SA and phytoalexins (VanDoorn et al., 2015; Wari et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020). These compounds play a role in affecting insect physiology and performance on the plants (Alamgir et al., 2016).

Beyond these direct and indirect defence pathways, honeydew emerges as a key player in shaping early events in the rice defence cascade, significantly influencing phytohormone levels and potentially affecting downstream signal transduction mechanisms (Wasternack and Song, 2017). The complex interaction between honeydew and plant defence extends beyond phytohormones, prompting a comprehensive exploration of additional signalling components. This investigation encompasses Ca2+-mediated responses (Arimura et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2020), levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Zebelo and Maffei, 2015; Shinya et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2020), and the activity of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (Hettenhausen et al., 2015). Furthermore, the role of honeydew-induced transcription factors as crucial connectors, directly linking signalling events to the activation of defence genes (Woldemariam et al., 2011; Wari et al., 2019). Honeydew deposition is also utilised by plants for the detection of insect herbivores. For instance, some insects, such as whiteflies, feed on plants without causing considerable damage to mesophyll cells, making it difficult for plants to detect them. However, honeydew deposition by whiteflies on plants aids in the identification of the pest due to the presence of whitefly-associated molecular patterns in the honeydew (VanDoorn et al., 2015).

4.3. Indirect Positive Effects of Honeydew on Plants

In addition to its direct positive effects, honeydew indirectly benefits plants in several ways. The presence of honeydew on plants helps attract beneficial insects, such as parasitoids and predators, that feed on it. Honeydew contributes to this in two ways: first, it directly serves as a food source for natural enemies due to its nutrient composition (Wäckers et al., 2008); second, the microorganisms in honeydew release volatiles with kairomonal properties that attract natural enemies (Leroy et al., 2011). For instance, bacterial volatiles from the cotton-melon aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover honeydew have been shown to mediate oviposition site selection in ladybird beetles, a key predator of aphids. Volatiles such as DL-lactic acid, 4,6-dimethyl-2-heptanone, and didodecyl phthalate, produced by Acinetobacter sp. and Pseudomonas sp., significantly attracted mated females of Propylea japonica and influenced their egg-laying behaviour (Li et al., 2025). This mechanism ensures that emerging larvae have immediate access to food sources, reinforcing natural aphid suppression and strengthening plant protection. This honeydew-plant relationship benefits plants by promoting natural biological control, protecting them from insect herbivores (Álvarez-Pérez et al., 2024). Additionally, pollinator insects use honeydew as a source of carbohydrates, and while foraging for it, they visit numerous plants, thereby increasing the likelihood of plant pollination (Wäckers et al., 2008; Leroy et al., 2011)

4.4. Honeydew and Its Diverse Roles in Soil and Plant Ecosystems:

Sap feeding insects excrete honeydew, which, though seemingly minute individually, has a substantial accumulative impact on a larger scale (Owen and Wiegert, 1976; Buckley, 1987). For example, aphids like Tuberolachnus salignis /Hemiptera: Aphididae) drain 1- 4 mg of sugar daily from plants (Mittler, 1958). Over its 30-day life cycle, a single aphid can remove 30-120 mg of sugar. Even smaller aphids, such as Eucallipterus tiliae L., at about 1/20 the size of T. salignis, contribute by removing 0.38 mg of sugar daily (Llewellyn, 1972; Llewellyn et al., 1974). Scaling up, a 14 m high lime tree may host over a million aphids at its peak, resulting in a daily release of 407 g of sugar per square meter and an estimated annual honeydew deposition of 1 kg m-² yr-¹ beneath aphid-infested lime trees (Llewellyn, 1972).

Honeydew produced by sap-feeding insects such as aphids, scale insects, and leafhoppers, plays a crucial role in influencing soil fertility through various ecological interactions and nutrient dynamics. For instance, honeydew from scale insects significantly influences fungal community diversity and ecological interactions, serving as a vital carbon source supporting microbial and fungal activity in the soil (Dhami et al., 2011, 2013; Michalzik, 2011).

Aphid-produced honeydew, such as that secreted by Cinara spp., contributes dissolved and particulate organic matter to the forest floor, enhancing soil nitrogen availability and net primary production. This contribution increases soil respiration and alters nitrogen fluxes, impacting overall soil fertility (Michalzik and Stadler, 2005). In semi-natural experiments under aphid-infested and uninfested Norway spruce trees, solutions under infested trees showed higher concentrations of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) but lower concentrations of dissolved organic nitrogen (DON), NO3--N, and NH4+-N in throughfall solutions, as well as lower NH4-N in forest floor solutions (Michalzik and Stadler, 2005). Interactions among Tamarix plants, the leafhopper Opsius stactogalus (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae), and litter fungi emphasise the broader ecological impact of insect-produced honeydew on soil and plant health. Honeydew contributes organic matter and nutrients that support microbial biomass and activity, enhancing nutrient cycling processes crucial for maintaining soil fertility (Michalzik, 2011).

Honeydew serves as an additional carbon source for soil microorganisms, particularly on the soil surface, leading to increased microbial biomass over time (Grier and Vogt, 1990; Stadler and Michalzik, 1998; Seeger and Filser, 2008). This easily degradable carbon source stimulates microbial metabolism and activity, thereby enhancing soil fertility. Honeydew deposition affects throughfall composition, impacting soil solution chemistry and nutrient dynamics under Norway spruce trees (Stadler and Michalzik, 1998). While honeydew does not directly increase available soil nitrogen, it may reduce nitrogen mineralisation rates and nitrogen uptake by plants, negatively impacting soil fertility (Grier and Vogt, 1990). Honeydew indirectly creates complex interactions within the soil food web. It influences not only microbial biomass but also the activity of soil fauna such as Collembola (springtails), which can indirectly benefit plant growth by enhancing soil health (Grier and Vogt, 1990; Seeger and Filser, 2008). Changes in soil chemistry due to honeydew deposition can influence plant nutrient uptake and overall plant fitness via interconnectedness of aboveground aphid activity and belowground soil processes, honeydew impacts plant health through its effects on nutrient dynamics (Stadler and Michalzik, 1998).

In conclusion, honeydew enriches microbial biomass and activity by providing a valuable carbon source, potentially enhancing soil fertility. It plays a significant role in influencing soil solution chemistry, thereby impacting nutrient dynamics. However, honeydew’s influence on soil nitrogen availability may lead to a reduction, which could negatively affect soil fertility (Grier and Vogt, 1990; Seeger and Filser, 2008). Although honeydew does not directly boost plant fitness through increased soil nitrogen, it affects plant health through complex interactions within the soil ecosystem and changes in soil solution chemistry. These indirect effects can either promote or impede plant growth, depending on the dynamics within the soil environment (Grier and Vogt, 1990; Stadler and Michalzik, 1998; Seeger and Filser, 2008). Collectively, these studies bring attention to the multifaceted role of honeydew in soil and plant ecosystems, emphasising its dual impact on both soil fertility and plant fitness.

5. Consequences at the Agricultural Level

The impacts of honeydew on agriculture are significant, with both positive and negative effects. On the positive side, honeydew can support important ecosystem services like natural pest control and pollination (Álvarez-Pérez et al., 2023; Ali et al., 2024; de Bobadilla et al., 2024). However, honeydew also has negative effects, such as reducing plant photosynthesis, lowering crop yields, and contaminating fruits, vegetables, and flowers, which makes them unfit for market (Capinera, 2020; Ali, 2023). Additionally, aphid honeydew increases microbial activity in the soil, altering nitrogen levels and potentially affecting plant nutrient uptake (Whitaker et al., 2014). Moulds that develop on honeydew are also a significant threat, as they reduce photosynthesis and decrease crop yields. For example, Tosh and Brogan, (2015) showed that untreated whitefly infestations, which cause honeydew deposition on plants, can lead to the growth of sooty mould. While sooty mould is often considered mainly an aesthetic issue, its build-up can reduce photosynthesis and negatively impact crop yields. In the U.S., cotton growers suffer financial losses due to ‘sticky cotton’ caused by sooty mould on cotton lint contaminated with aphid and whitefly honeydew (Hequet, Henneberry and Nichols, 2007). From an ecological perspective, honeydew also plays a role in soil microbial processes, increasing microbial immobilisation and potentially limiting nitrogen uptake by plants (Wardle, 2013). Moreover, microorganisms alter the volatile properties and nutritional composition of honeydew, which can affect its interactions with the environment (Leroy et al., 2011; Francis et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2024). These diverse impacts of honeydew on agriculture highlight the importance of balancing its negative effects with its potential benefits for plant protection.

6. Conclusions and Future Prospects

This review highlights the complex relationship between honeydew and plant physiology, emphasising its crucial role in shaping plant health. While existing research mainly focuses on honeydew composition, regulation, microbial communities, and its influence on insect-plant interactions, the connection between honeydew and plant health, as well as its direct impact on plant health, remains largely unexplored. Despite early findings suggesting honeydew’s role in regulating flowering, enhancing soil fertility, and modulating plant defence mechanisms, aspects such as its potential contribution to plant diseases and its effects on photosynthesis have received limited attention. There is an urgent need for further investigation into these overlooked areas to gain a more comprehensive understanding of honeydew’s influence on plant health. Future research should explore the mechanisms underlying honeydew-mediated plant diseases, including the spread of secondary infections and their impact on overall plant fitness. Additionally, studying the effects of honeydew deposition on photosynthesis and its long-term consequences for plant growth and productivity is essential. Furthermore, it is important to consider honeydew in agricultural practices, recognising that its impacts extend beyond farming and affect various aspects of ecosystem functioning. Effective management strategies are crucial to reduce the negative effects of honeydew on crop yields and overall agricultural productivity. By addressing these research gaps and implementing comprehensive management approaches, it will be possible to use honeydew to optimise plant health and promote ecosystem resilience.

Author Contributions

J.A. R.C. A.B. and E.C. conceived the idea. J.A., C.R., M.D., R.R. T.D. A.A.Y. E.C. and A.B. wrote the first draft of the paper with input from all authors.

Data Availability Statement

This review paper does not contain original data; therefore, data availability is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 was created using Biorender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Alamgir, K. M. et al. (2016) ‘Systematic analysis of rice (Oryza sativa) metabolic responses to herbivory’, Plant, Cell & Environment, 39(2), pp. 453–466. [CrossRef]

- Ali, J. (2023) ‘The Peach Potato Aphid (Myzus persicae): Ecology and Management’, 1, p. 132. [CrossRef]

- Ali, J. et al. (2024) ‘Honeydew : A keystone in insect – plant interactions , current insights and future perspectives’, (January), pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Pérez, S., Lievens, B. and de Vega, C. (2023) ‘Floral nectar and honeydew microbial diversity and their role in biocontrol of insect pests and pollination’, Current Opinion in Insect Science, p. 101138. [CrossRef]

- Arimura, G.-I., Ozawa, R. and Maffei, M. E. (2011) ‘Recent advances in plant early signaling in response to herbivory’, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 12(6), pp. 3723–3739. [CrossRef]

- Auclair, J. L. (1963) ‘Aphid feeding and nutrition’, Annual review of entomology, 8(1), pp. 439–490.

- Bae, Hanhong et al. (2005) ‘Exogenous trehalose alters Arabidopsis transcripts involved in cell wall modification, abiotic stress, nitrogen metabolism, and plant defense’, Physiologia plantarum, 125(1), pp. 114–126. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, S. et al. (2022) ‘Combined Elevation of Temperature and CO2 Impacts the Production and Sugar Composition of Aphid Honeydew’, Journal of Chemical Ecology, 48(9–10), pp. 772–781.

- de Bobadilla, M. F. et al. (2024) ‘Honeydew management to promote biological control’, Current Opinion in Insect Science, 61, p. 101151. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. C. (1987) ‘Interactions involving plants, Homoptera, and ants’, Annual review of Ecology and Systematics, 18(1), pp. 111–135. [CrossRef]

- Buitenhuis, R. et al. (2004) ‘The role of honeydew in host searching of aphid hyperparasitoids’, Journal of chemical ecology, 30, pp. 273–285. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. N. and Bellows Jr, T. S. (1991) ‘Whitefly biology.’.

- Calvo-Agudo, M. et al. (2020) ‘IPM-recommended insecticides harm beneficial insects through contaminated honeydew’, Environmental Pollution, 267, p. 115581. [CrossRef]

- Capinera, J. (2020) Handbook of vegetable pests. Academic press.

- Carena, M. J. and Glogoza, P. (2004) ‘Resistance of maize to the corn leaf aphid: a review.’.

- Chomnunti, P. et al. (2014) ‘The sooty moulds’, Fungal diversity, 66, pp. 1–36.

- Cleland, C. F. (1974) ‘Isolation of flower-inducing and flower-inhibitory factors from aphid honeydew’, Plant Physiology, 54(6), pp. 899–903. [CrossRef]

- Cleland, C. F. and Ajami, A. (1974) ‘Identification of the flower-inducing factor isolated from aphid honeydew as being salicylic acid’, Plant Physiology, 54(6), pp. 904–906. [CrossRef]

- Colazza, S., Peri, E. and Cusumano, A. (2023) ‘Chemical ecology of floral resources in conservation biological control’, Annual Review of Entomology, 68, pp. 13–29. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D. L. (1921) ‘Annual Address. Honey-Dew Smut and Photosynthesis’.

- Dhami, M. K. et al. (2011) ‘Species-specific chemical signatures in scale insect honeydew’, Journal of chemical ecology, 37, pp. 1231–1241. [CrossRef]

- Dhami, M. K. et al. (2013) ‘Diverse honeydew-consuming fungal communities associated with scale insects’, PLoS One, 8(7), p. e70316. 0316. [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C. H. (2009) ‘Auchenorrhyncha:(cicadas, spittlebugs, leafhoppers, treehoppers, and planthoppers)’, in Encyclopedia of insects. Elsevier, pp. 56–64.

- Dik, A. J. (1990) ‘Population dynamics of phyllosphere yeasts: influence of yeasts on aphid damage, diseases and fungicide activity in wheat’.

- Dik, A. J. and Van Pelt, J. A. (1992) ‘Interaction between phyllosphere yeasts, aphid honeydew and fungicide effectiveness in wheat under field conditions’, Plant pathology, 41(6), pp. 661–675. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A. (2006) ‘Phloem-sap feeding by animals: problems and solutions’, Journal of experimental botany, 57(4), pp. 747–754. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A. E. (1993) ‘The nutritional quality of phloem sap utilized by natural aphid populations’, Ecological Entomology, 18(1), pp. 31–38. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A. E. (2009) ‘Honeydew’, in Encyclopedia of insects. Elsevier, pp. 461–463.

- Edde, P. A. (2022) ‘7-Arthropod pests of maize Zea mays (L.)’, Field crop arthropod pests of economic importance. Academic Press, Richmond, VA, pp. 410–465.

- Van Emden, H. F. and Harrington, R. (2017) Aphids as crop pests. Cabi.

- Erb, M. and Reymond, P. (2019) ‘Molecular interactions between plants and insect herbivores’, Annual review of plant biology, 70, pp. 527–557. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M. K. et al. (2002) ‘Age-specific patterns in honeydew production and honeydew composition in the aphid Metopeurum fuscoviride: implications for ant-attendance’, Journal of Insect Physiology, 48(3), pp. 319–326. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M. K. and Shingleton, A. W. (2001) ‘Host plant and ants influence the honeydew sugar composition of aphids’, Functional Ecology, 15(4), pp. 544–550. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M. K., Völkl, W. and Hoffmann, K. H. (2005) ‘Honeydew production and honeydew sugar composition of polyphagous black bean aphid, Aphis fabae (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on various host plants and implications for ant-attendance’, European Journal of Entomology, 102(2), pp. 155–160.

- Fokkema, N. J. et al. (1983) ‘Aphid honeydew, a potential stimulant of Cochliobolus sativus and Septoria nodorum and the competitive role of saprophytic mycoflora’, Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 81(2), pp. 355–363. [CrossRef]

- Francis, F. et al. (2020) ‘From diverse origins to specific targets: role of microorganisms in indirect pest biological control’, Insects, 11(8), p. 533. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, D., Kohli, A. and Horgan, F. G. (2013) ‘Rice resistance to planthoppers and leafhoppers’, Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 32(3), pp. 162–191. [CrossRef]

- Garre, V., Tenberge, K. B. and Eising, R. (1998) ‘Secretion of a fungal extracellular catalase by Claviceps purpurea during infection of rye: putative role in pathogenicity and suppression of host defense’, Phytopathology, 88(8), pp. 744–753. [CrossRef]

- Grier, C. C. and Vogt, D. J. (1990) ‘Effects of aphid honeydew on soil nitrogen availability and net primary production in an Alnus rubra plantation in western Washington’, Oikos, pp. 114–118. [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, D. L., Wei, Y. and Leggett, J. E. (1992) ‘Homopteran honeydew sugar composition is determined by both the insect and plant species’, Comparative biochemistry and physiology part B: Comparative Biochemistry, 101(1–2), pp. 23–27. [CrossRef]

- Hequet, E. F., Henneberry, T. J. and Nichols, R. L. (2007) ‘Sticky Cotton: Causes, Effects, and Prevention’, United States Department of Agriculture, (1915), pp. 1–219.

- Hettenhausen, C., Schuman, M. C. and Wu, J. (2015) ‘MAPK signaling: a key element in plant defense response to insects’, Insect science, 22(2), pp. 157–164. [CrossRef]

- Hijaz, F., Lu, Z. and Killiny, N. (2016) ‘Effect of host-plant and infection with “C andidatus Liberibacter asiaticus” on honeydew chemical composition of the Asian citrus psyllid, D iaphorina citri’, Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 158(1), pp. 34–43.

- Hodkinson, I. D. (2009) ‘Life cycle variation and adaptation in jumping plant lice (Insecta: Hemiptera: Psylloidea): a global synthesis’, Journal of natural History, 43(1–2), pp. 65–179. [CrossRef]

- Hogervorst, P. A. M., Wäckers, F. L. and Romeis, J. (2007) ‘Effects of honeydew sugar composition on the longevity of Aphidius ervi’, Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 122(3), pp. 223–232. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C. et al. (2024) ‘Molecular interaction network of plant-herbivorous insects’, Advanced Agrochem, 3(1), pp. 74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.aac.2023.08.008. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, P. D. et al. (2011) ‘Microorganisms from aphid honeydew attract and enhance the efficacy of natural enemies’, Nature communications, 2(1), p. 348. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, P. D. et al. (2014) ‘Aphid honeydew: An arrestant and a contact kairomone for Episyrphus balteatus (Diptera: Syrphidae) larvae and adults’, European Journal of Entomology, 111(2), pp. 237–242. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. et al. (2025) ‘Bacterial volatiles from aphid honeydew mediate ladybird beetles oviposition site choice’, Pest Management Science. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. et al. (2024) ‘Chemical cues from honeydew-associated bacteria to enhance parasitism efficacy: from laboratory to field assay’, Journal of Pest Science, 97(2), pp. 873–884. [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, M. (1972) ‘The effects of the lime aphid, Eucallipterus tiliae L.(Aphididae) on the growth of the lime Tilia x Vulgaris Hayne. I. Energy requirements of the aphid population’, Journal of Applied Ecology, pp. 261–282. [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, M., Rashid, R. and Leckstein, P. (1974) ‘The ecological energetics of the willow aphid Tuberolachnus salignus (Gmelin); honeydew production’, The Journal of Animal Ecology, pp. 19–29. [CrossRef]

- LT, L. and RODRIGUEZ, J. G. (1985) ‘The leafhoppers and planthoppers’.

- Michalzik, B. (2011) ‘Insects, infestations, and nutrient fluxes’, in Forest hydrology and biogeochemistry: synthesis of past research and future directions. Springer, pp. 557–580.

- Michalzik, B. and Stadler, B. (2005) ‘Importance of canopy herbivores to dissolved and particulate organic matter fluxes to the forest floor’, Geoderma, 127(3–4), pp. 227–236. [CrossRef]

- Mihaela Fericean, L. (2012) ‘the Behaviour, Life Cycle and Biometrical Measurements of Aphis Fabae’, Research Journal of Agricultural Science, 44(4), pp. 31–37.

- Mittler, T. E. (1958) ‘Studies on the feeding and nutrition of Tuberolachnus salignus (Gmelin)(Homoptera, Aphididae) II. The nitrogen and sugar composition of ingested phloem sap and excreted honeydew’, Journal of Experimental Biology, 35(1), pp. 74–84. [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, R. J., Campbell, B. C. and Dreyer, D. L. (1990) ‘Honeydew analysis for detecting phloem transport of plant natural products: implications for host-plant resistance to sap-sucking insects’, Journal of Chemical Ecology, 16, pp. 1899–1909.

- Mostafa, S. et al. (2022) ‘Plant responses to herbivory, wounding, and infection’, International journal of molecular sciences, 23(13), p. 7031.

- van Neerbos, F. A. C. et al. (2020) ‘Honeydew composition and its effect on life-history parameters of hyperparasitoids’, Ecological Entomology, 45(2), pp. 278–289. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A. S. and Mooney, K. A. (2022) ‘The evolution and ecology of interactions between ants and honeydew-producing hemipteran insects’, Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 53(1), pp. 379–402. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S. (2008) ‘Sooty mold’.

- Owen, D. F. and Wiegert, R. G. (1976) ‘Do consumers maximize plant fitness?’, Oikos, pp. 488–492. [CrossRef]

- Pellizzari, G. et al. (2012) ‘Phenology, ethology and distribution of Pseudococcus comstocki, an invasive pest in northeastern Italy’, Bulletin of Insectology, 65(2), pp. 209–215.

- Quesada, C. R., Scharf, M. E. and Sadof, C. S. (2020) ‘Excretion of non-metabolized insecticides in honeydew of striped pine scale’, Chemosphere, 249, p. 126167. [CrossRef]

- Rabbinge, R. et al. (1981) ‘Damage effects of cereal aphids in wheat’, Netherlands Journal of Plant Pathology, 87, pp. 217–232.

- Rabbinge, R. et al. (1984) ‘Effects of the saprophytic leaf mycoflora on growth and productivity of winter wheat’, Netherlands Journal of Plant Pathology, 90, pp. 181–197. [CrossRef]

- Rondoni, G. et al. (2018) ‘Vicia faba plants respond to oviposition by invasive Halyomorpha halys activating direct defences against offspring’, Journal of Pest Science, 91, pp. 671–679. [CrossRef]

- Sabri, A. et al. (2013) ‘Proteomic investigation of aphid honeydew reveals an unexpected diversity of proteins’, PloS one, 8(9), p. e74656. [CrossRef]

- Schillewaert, S. et al. (2017) ‘The effect of host plants on genotype variability in fitness and honeydew composition of Aphis fabae’, Insect science, 24(5), pp. 781–788. [CrossRef]

- Schoonhoven, L. M. et al. (2005) Insect-plant biology. Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Schwartzberg, E. G. and Tumlinson, J. H. (2014) ‘Aphid honeydew alters plant defence responses’, Functional Ecology, 28(2), pp. 386–394. [CrossRef]

- Seeger, J. and Filser, J. (2008) ‘Bottom-up down from the top: Honeydew as a carbon source for soil organisms’, European Journal of Soil Biology, 44(5–6), pp. 483–490. [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, B. et al. (2020) ‘Sugar, amino acid and inorganic ion profiling of the honeydew from different hemipteran species feeding on Abies alba and Picea abies’, PLoS One, 15(1), p. e0228171. [CrossRef]

- Shinya, T. et al. (2016) ‘Modulation of plant defense responses to herbivores by simultaneous recognition of different herbivore-associated elicitors in rice’, Scientific reports, 6(1), p. 32537. [CrossRef]

- Stadler, B. and Michalzik, B. (1998) ‘Linking aphid honeydew, throughfall, and forest floor solution chemistry of Norway spruce’, Ecology Letters, 1(1), pp. 13–16. [CrossRef]

- Starr, C. K. (2021) Encyclopedia of social insects. Springer.

- Taylor, S. H., Parker, W. E. and Douglas, A. E. (2012) ‘Patterns in aphid honeydew production parallel diurnal shifts in phloem sap composition’, Entomologia experimentalis et applicata, 142(2), pp. 121–129. [CrossRef]

- Tena, A. et al. (2013) ‘Energy reserves of parasitoids depend on honeydew from non-hosts’, Ecological Entomology, 38(3), pp. 278–289. [CrossRef]

- Tena, A. et al. (2016) ‘Parasitoid nutritional ecology in a community context: the importance of honeydew and implications for biological control’, Current opinion in insect science, 14, pp. 100–104. [CrossRef]

- Tosh, C. R. and Brogan, B. (2015) ‘Control of tomato whiteflies using the confusion effect of plant odours’, Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 35(1), pp. 183–193. [CrossRef]

- VanDoorn, A. et al. (2015) ‘Whiteflies glycosylate salicylic acid and secrete the conjugate via their honeydew’, Journal of Chemical Ecology, 41, pp. 52–58. [CrossRef]

- Vereijken, P. H. (1979) Feeding and multiplication of three cereal aphid species and their effect on yield of winter wheat. Wageningen University and Research.

- Völkl, W. et al. (1999) ‘Ant-aphid mutualisms: the impact of honeydew production and honeydew sugar composition on ant preferences’, Oecologia, 118, pp. 483–491. [CrossRef]

- Wäckers, F. L. (2000) ‘Do oligosaccharides reduce the suitability of honeydew for predators and parasitoids? A further facet to the function of insect-synthesized honeydew sugars’, Oikos, 90(1), pp. 197–201. [CrossRef]

- Wäckers, F. L., Van Rijn, P. C. J. and Heimpel, G. E. (2008) ‘Honeydew as a food source for natural enemies: making the best of a bad meal?’, Biological Control, 45(2), pp. 176–184. [CrossRef]

- Wardle, D. A. (2013) Communities and ecosystems: linking the aboveground and belowground components (MPB-34). Princeton University Press.

- Wari, D. et al. (2019) ‘Honeydew-associated microbes elicit defense responses against brown planthopper in rice’, Journal of experimental botany, 70(5), pp. 1683–1696. [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C. and Song, S. (2017) ‘Jasmonates: biosynthesis, metabolism, and signaling by proteins activating and repressing transcription’, Journal of Experimental Botany, 68(6), pp. 1303–1321.

- Weintraub, P. G. (2009) ‘Physical control: an important tool in pest management programs’, Biorational Control of Arthropod Pests: Application and Resistance Management, pp. 317–324.

- Whitaker, M. R. L., Katayama, N. and Ohgushi, T. (2014) ‘Plant–rhizobia interactions alter aphid honeydew composition’, Arthropod-Plant Interactions, 8, pp. 213–220.

- Whitfield, A. E., Falk, B. W. and Rotenberg, D. (2015) ‘Insect vector-mediated transmission of plant viruses’, Virology, 479, pp. 278–289. [CrossRef]

- Woldemariam, M. G., Baldwin, I. T. and Galis, I. (2011) ‘Transcriptional regulation of plant inducible defenses against herbivores: a mini-review’, Journal of Plant Interactions, 6(2–3), pp. 113–119. [CrossRef]

- Wool, D., Hendrix, D. L. and Shukry, O. (2006) ‘Seasonal variation in honeydew sugar content of galling aphids (Aphidoidea: Pemphigidae: Fordinae) feeding on Pistacia: host ecology and aphid physiology’, Basic and Applied Ecology, 7(2), pp. 141–151. [CrossRef]

- Zebelo, S. A. and Maffei, M. E. (2015) ‘Role of early signalling events in plant–insect interactions’, Journal of Experimental Botany, 66(2), pp. 435–448. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. et al. (2020) ‘Proteomics of the honeydew from the brown planthopper and green rice leafhopper reveal they are rich in proteins from insects, rice plant and bacteria’, Insects, 11(9), p. 582. [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, C. et al. (2004) ‘Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception’, Nature, 428(6984), pp. 764–767. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).