1. Introduction

Herbivory is a central ecological interaction that has driven the evolution of complex plant defense mechanisms [

1]. Plants face continuous pressure from herbivores and have developed a variety of defensive strategies to mitigate the impact of herbivory, ranging from structural barriers to chemical deterrents [

2]. These adaptations are particularly dynamic in tropical ecosystems, where the diversity and abundance of herbivores increase the selection pressures on plants, promoting intricate defenses and even inducible responses to deter their herbivores [

3,

4]. Thus, the understanding of these interactions is essential for elucidating the ecological and evolutionary significance of plant defenses in natural ecosystems.

To counteract herbivory, plants employ a wide range of defense mechanisms. Physical defenses, such as trichomes and cell wall thickening, are often coupled with chemical defenses, including compounds like phenolics and alkaloids, to reduce palatability and slow herbivore growth [

5]. In this context, the hypersensitivity response (HR) has emerged as an effective defense against insect herbivores, providing a localized reaction that limits damage and contains nutrient loss [

6]. While HR was traditionally associated with pathogen resistance, studies now suggest it also serves as an herbivore deterrent, particularly against insects, by inducing cell death around the feeding site, thereby restricting further damage [

7,

8]. Together, these defenses create a multifaceted system that enables plants to withstand and adjust to herbivory pressure.

Silicon (Si) has gained attention as a key element in plant defense against environmental stresses, including herbivory [

9,

10]. The presence of Silicon has been discussed as a multimodal defense mechanism, whose effects range from higher attractiveness of natural enemies [

11] to differential protein expression, presenting direct and indirect effects on herbivores and herbivory defense mechanisms [

12]. Silicon accumulates in plant tissues, enhancing structural rigidity and deterring herbivory by making leaves tougher and less digestible [

13,

14]. This mineral element has been shown to reduce herbivore feeding rates and overall damage, establishing its protective role, particularly in environments with high herbivory [

15]. A recent meta-analysis has shown that silicon-rich plants experience herbivory levels ~33% lower than silicon-poor plants [

16]. In addition, silicon’s role in herbivory resistance can be amplified when combined with other defense mechanisms, providing a comprehensive approach to deterring herbivores through multiple channels [

17].

Besides its well-established importance on herbivory defense, recent studies have proposed that the feeding habit of the herbivore can be a determinant for its sensitivity to Si induced defenses [

16]. The effects of Si defenses against exophagous herbivores are well established in the literature, and the attacks of feeding guilds like phloem-feeders [

18], and chewers [

15] are commonly referred as being lower in plants with higher Si content. In this context, fluid-feeders are pointed as less adversely impacted by Si induced defenses when compared to chewing insects, mammals and plant-boring arthropods [

16]. However, Si effects on the resistance against endophytic herbivores are less clear and overlooked in herbivory defense studies.

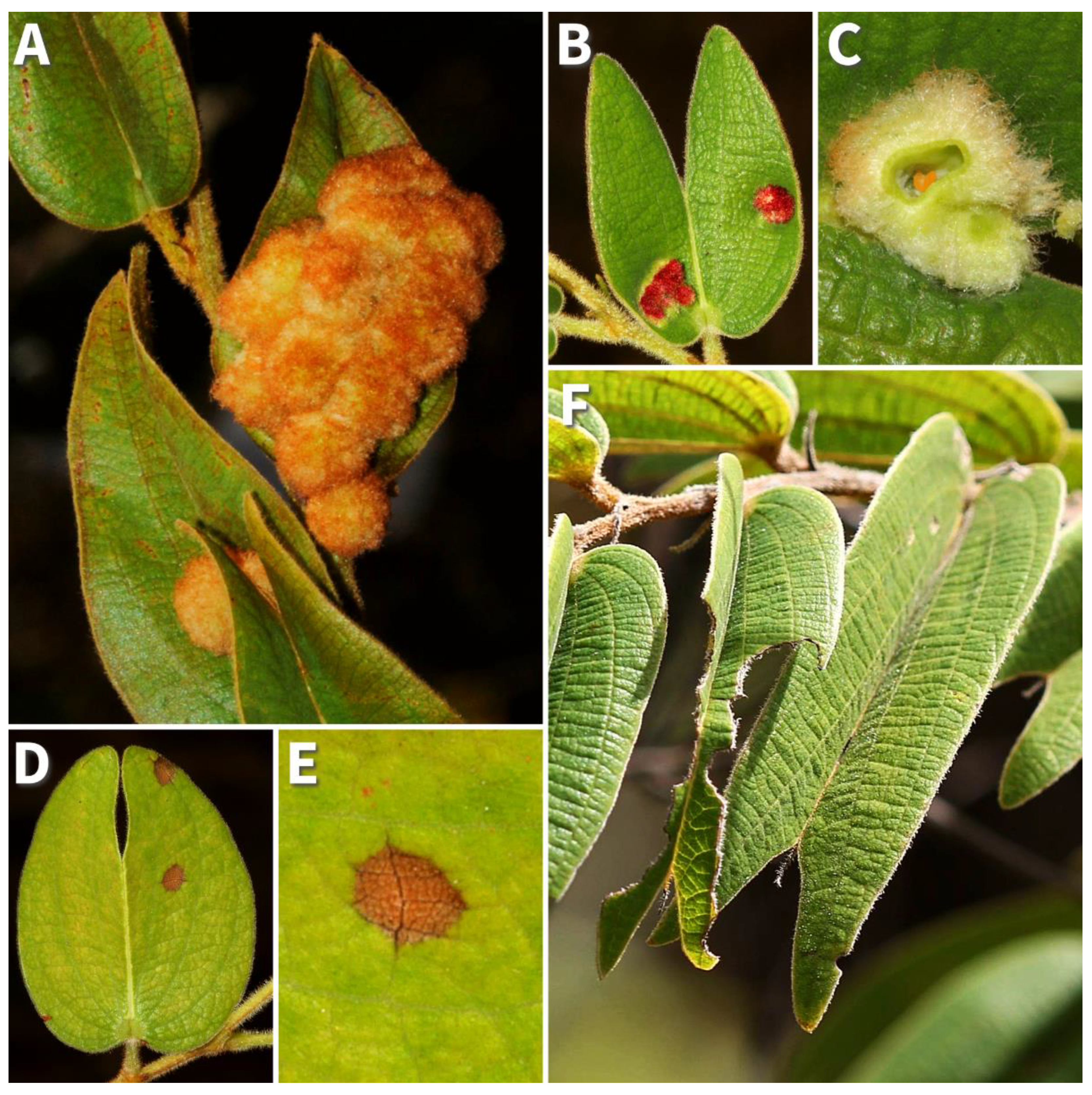

Bauhinia genus represents a focal group for studies on plant-herbivore interactions due to its complex relationships with insect herbivores and gall-inducing insects, as well as its array of defensive strategies [

19,

20]. Known for its structural defenses [

21],

Bauhinia also demonstrates inducible responses to herbivory as HR (hypersensitivity reactions), and that may include silicon accumulation [

8]. Studies on

Bauhinia brevipes Vogel revealed how this plant leverages both silicon and HR as effective responses against insect herbivores and gall-forming insects, which are known to specialize in attacking determined plant species and tissues [

22]. In this host plant, HR is better understood in the defense against galls of

Schizomyia macrocapillata Maia, 2005 (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) [

8,

23,

24]. HR is induced during the early ontogenetic stages of

S. macrocapillata galls, resulting in almost 90% mortality of this gall-inducing population [

23]. However, little is known about the relationship between HR and other defense mechanisms in the

B. brevipes system (

Figure 1). Therefore, exploring the dual role of silicon and HR in

Bauhinia provides valuable insights into the adaptive significance of these defenses against highly specialized insect threats.

The present study investigates the role of silicon in B. brevipes and its relationship with the occurrence of gall-inducing insects, with a focus on hypersensitivity reactions as potential defense mechanisms. Specifically, we aim to determine whether silicon accumulation in leaves of B. brevipes correlates with a decrease in gall formation and if HR modulates this relationship by containing damage locally. To address these questions, we examined silicon content across different leaf tissue types: galled, ungalled, and gall tissue. Thus, our aim was to understand the relationship between the foliar Si content of B. brevipes and herbivory by chewing insects and gall-inducing insects. We sought to answer the following questions: 1. Does the amount of silicon in leaves affect the occurrence of gall-inducing insects in B. brevipes? 2. Does the amount of silicon in leaves mediate defense mechanisms against chewing and gall-inducing herbivores in B. brevipes? 3. Is there a difference in silicon content when comparing tissues of leaves without galls, leaves with galls, and the gall tissue itself? and 4. How does this silicon content mediate the relationships between gall-inducing insects and other herbivores in B. brevipes? We hypothesized that: 1. The higher the silicon content, the lower the number of galls found on the leaves of B. brevipes. 2. Silicon has a negative effect on the attack rates of chewing insects. 3. Leaves with galls will have lower silicon content compared to leaves without galls, and the silicon content in the gall tissue will be lower than in the adjacent tissue of gall-bearing leaves, due to the ability of galling insects to manipulate chemical compounds in plant tissues, and 4. A higher number of galls will occur on leaves with lower silicon content, which will result in a positive relationship with the herbivory rate.

2. Results

The number of galls per plant ranged from 0 to 52, with a mean of 4 ± 11 galls per plant. The average herbivory rate was 2.57 ± 3.45 %, ranging from 0 to 15.97 %. The mean silicon content in leaves was 0.13 ± 0.02, varying between 0.09 and 0.17. The mean defense rate was 86.47 ± 23.19 %, with values ranging from 0 to 100%. The number of hypersensitivity reactions (HRs) averaged 36.6 ± 42.44, with a range from 0 to 257.

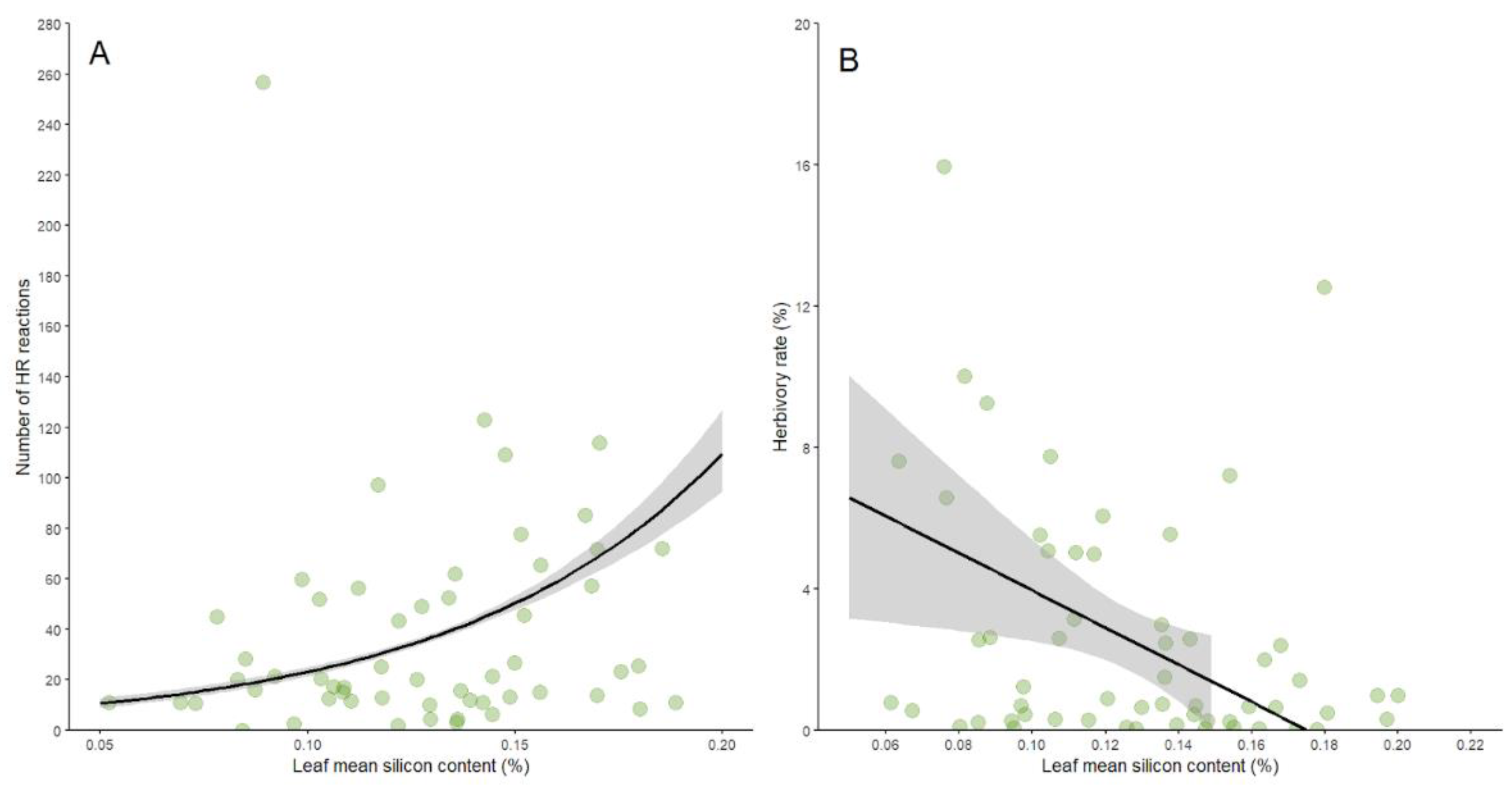

The number of galls per plant was not influenced by the mean silicon content in leaves (d.f.=1, p=0.723), suggesting that gall-inducing insects may bypass silicon-based defenses. Regarding defense mechanisms, although the defense rate of B. brevipes was not related to the mean silicon content in leaves (d.f.=1, F=0.789, p=0.378), the number of HRs was positively influenced by silicon content (R²=0.97,

Table 1,

Figure 2A). Conversely, herbivory by chewing herbivores was negatively influenced by silicon content in leaves (R²=0.09,

Table 1,

Figure 2B), indicating differential effects on plant defenses.

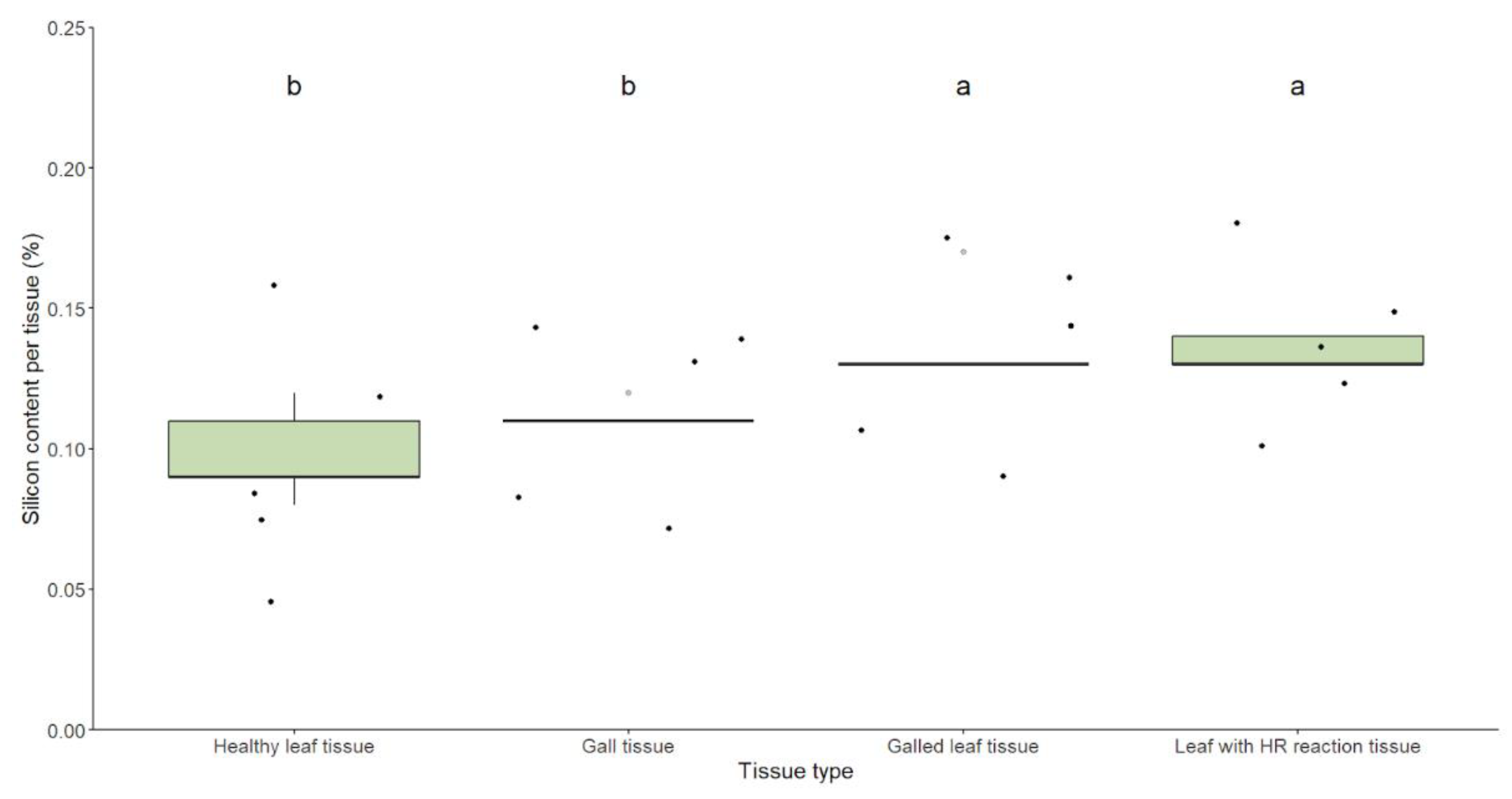

Silicon content varied among different tissue types (d.f.=3, F=11.11, p=0.00003). Gall-bearing leaves and leaves with hypersensitivity reactions did not differ significantly in silicon content and exhibited the highest values. Both tissue types differed from gall tissues and healthy leaves, which did not differ from each other and displayed the lowest silicon content (

Table 2,

Figure 3).

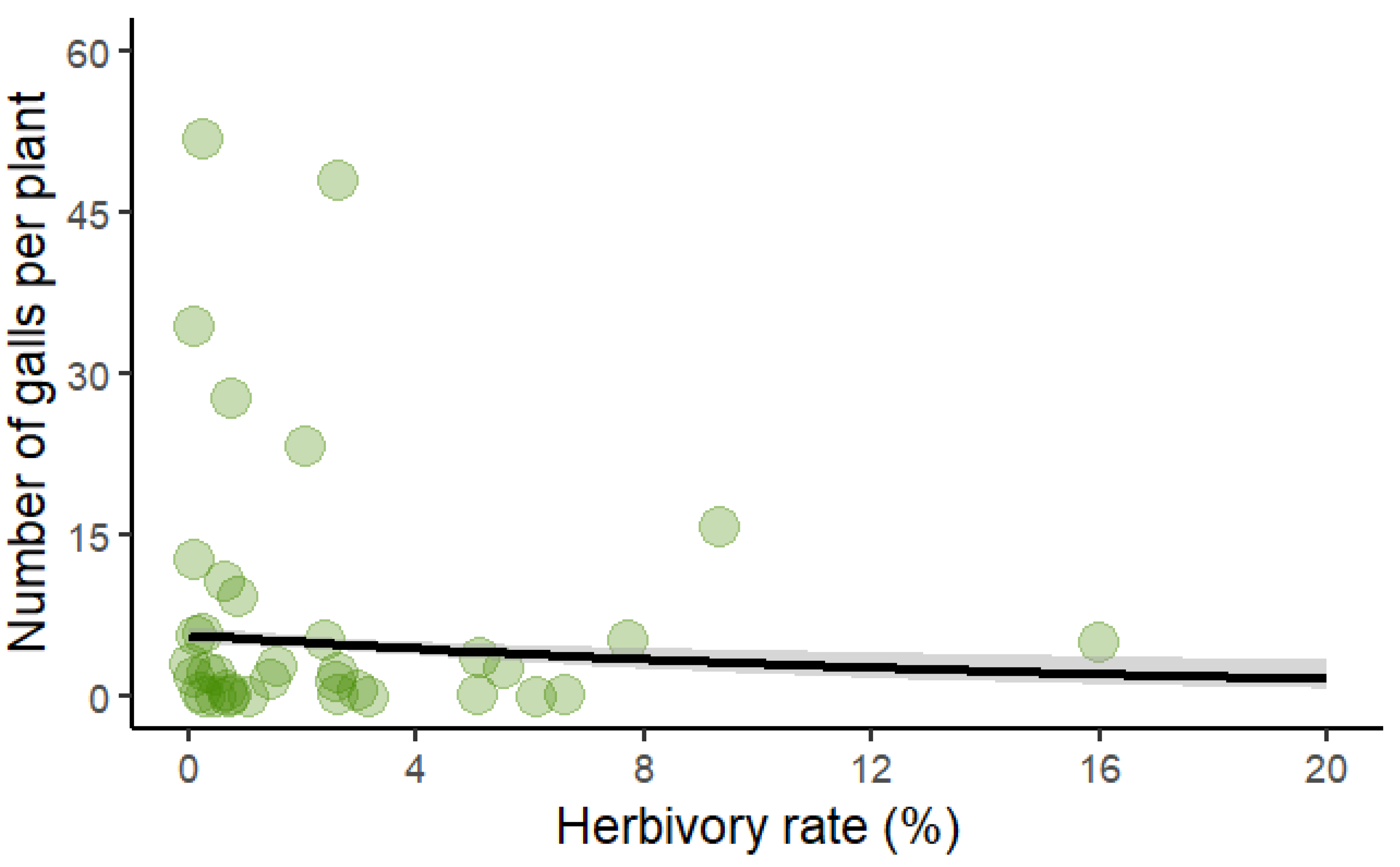

Finally, the number of galls was negatively affected by the herbivory rate, with more heavily consumed leaves exhibiting a lower number of galls (

Table 3,

Figure 4).

3. Discussion

Our study provides new insights into the role of silicon (Si) in Bauhinia brevipes, revealing its differential impact on plant-herbivore interactions. While silicon did not directly influence the occurrence of gall-inducing insects, our results suggest that it enhanced hypersensitivity reactions (HRs), a localized defense that is crucial against specialized herbivores. Additionally, a strong negative correlation was observed between foliar silicon content and herbivory by chewing insects, reinforcing the protective role of silicon as a structural plant defense. Intriguingly, we also found that galls exhibited lower silicon content compared to tissues associated with HRs and ungalled leaves, suggesting a potential mechanism by which gall-inducing insects may manipulate silicon distribution to mitigate its defensive effects.

Our results align with prior studies showing that silicon contributes to herbivory resistance by reinforcing structural defenses, such as thickened cell walls and increased leaf toughness, which reduce palatability and digestibility [

11,

13,

14,

25,

26]. Silicon has been stated as an efficient defense enhancer, since it can act in various defensive paths, as reducing the herbivores growth [

27], or altering the production of secondary metabolites, and inducing defense signaling pathways [

28]. The observed suppression of chewing herbivores supports findings from meta-analyses indicating that silicon-rich plants experience significantly reduced herbivory [

16]. The enhancement of HR in response to increased silicon content provides further evidence of its multifaceted role in plant defense. Silicon may amplify localized cell death or other defensive responses, as suggested in studies of other stress responses [

7,

9,

29,

31]. However, the lack of a direct effect of silicon on gall-inducing insects aligns with observations that endophytic herbivores can circumvent physical defenses by residing within plant tissues, where they are less exposed to silicon-induced rigidity [

16,

18].

Our findings highlight the complexity of silicon’s role in plant defense, particularly in ecosystems like the Cerrado, where plants are under intense herbivory pressure [

31,

32,

33]. The complementary nature of silicon and HRs in

B. brevipes reflects an adaptive advantage in the Cerrado, where high herbivore diversity exerts strong selective pressures [

33]. These findings highlight potential conservation strategies, such as promoting silicon-rich habitats to support plant resilience. While silicon alone may be insufficient to deter gall-inducing insects, its role in enhancing HR could provide a synergistic defense by increasing the mortality of gall-makers during early ontogeny [

23]. This potentially positive interaction between Si and HR may have significant implications for the distribution of herbivorous insects on host plants. In this case, the increased Si content in the leaves of B. brevipes, which were heavily infested with gall-inducing insects, resulted in reduced herbivory. Consequently, it is hypothesized that plants with high HR rates will exhibit fewer galls and a potentially lower abundance of chewing herbivore insects. Thus, we propose that the distribution of herbivorous insects on the host plant may be mediated by both constitutive (Si) and induced (HR) plant defense mechanisms, resulting in indirect interactions between herbivore insect guilds. Numerous studies have demonstrated that herbivores can interact directly or indirectly, mediated by the host plant (e.g. [

34]).

Interestingly, the similar silicon content in galled leaves and healthy leaves, combined with the lower silicon content in gall tissues, suggests that gall-inducing insects may actively manipulate silicon allocation within their host. It is already known that galls are able to accumulate secondary metabolites produced by plants to improve its own survival [

35,

36], and also to control the nutrient levels in the galle tissue, in comparison with the surroundings of the leaf [

37]. In this sense, silicon uptake can be linked to herbivory intensity, and more damaged leaves seem to accumulate higher rates of this element [

38]. Therefore, by mobilizing silicon away from the attacked tissues, gall-makers might reduce its defensive effects and create a more favorable microenvironment for their development. This hypothesis aligns with studies suggesting that gall-inducing insects can hijack host resources to suppress plant defenses and sustain gall growth [

17,

19,

39].

While our study provides compelling evidence for the defensive role of silicon, it is limited by the sample size of galled tissues and the reliance on observational data for some analyses. Experimental manipulations of silicon content in controlled environments could provide more definitive evidence of causality. Additionally, environmental factors such as soil silicon availability, water stress, and plant nutritional situation, which were not explicitly measured, might influence the observed patterns [

40,

41]. The apparent redistribution of silicon in galled tissues could also reflect a passive response to gall formation rather than active manipulation by gall-makers, a hypothesis requiring further investigation.

The role of silicon in enhancing plant defense has practical implications for both natural and managed ecosystems. Silicon supplementation in agricultural settings has been shown to reduce herbivore damage and improve crop resilience [

9,

15,

42]. The findings of our study suggest that similar strategies could be applied in biodiversity-rich systems like the Cerrado to bolster plant defenses against herbivory. Additionally, understanding how gall-inducing insects manipulate silicon distribution could inform pest management strategies that disrupt such mechanisms, reducing the success of these specialized herbivores.

Future research should explore the molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction between silicon and HR, particularly how silicon may prime or amplify HRs. Studies investigating the genetic and physiological pathways involved in silicon redistribution in galled tissues could shed light on the ability of gall-inducing insects to manipulate host defenses. Comparative analyses across other Bauhinia species and silicon-accumulating plants would help clarify whether these patterns are species-specific or represent a broader ecological strategy. Finally, the inclusion of soil and environmental variables in experimental designs would provide valuable context for understanding the conditions that modulate silicon-mediated defenses.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area

Our study occurred at the Panga Ecological Station (EEP) (19°10’55”S-48°23’35”W), located in Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. The EEP is a private natural reserve owned by the Federal University of Uberlândia, and encompasses various Cerrado vegetation formations, including grassland, savanna, and forested areas [

43]. The soil is hydromorphic latosol with a sandy texture and acidic properties [

44]. The altitude ranges from 750 to 830 meters [

44], and the climate is Aw type, according to Köppen’s classification, characterized by rainy summers (October to March) and dry winters (April to September). The average annual temperature and total precipitation are 22°C and 1,500 mm, respectively.

4.2. Field sampling

We sampled

B. brevipes individuals from December 2014 to February 2015, during the rainy season. The rainy period coincides with both the sprouting of new leaves and the peak of gall-maker attacks, including

S. macrocapillata [

45]. To avoid heterogeneity in anti-herbivory responses [

46], we sampled plants under similar environmental conditions (i.e., sunny areas and located at the same soil type). Additionally, we selected only individuals that showed signs of herbivory by chewer insects, gall-inducers, and/or with hypersensitivity reaction (HR) marks. Damage of other herbivore guilds (ex., sap suckers and scrapers) were rare in the evaluated

B. brevipes population. Overall, we included 58

B. brevipes individuals in this study.

4.3. Foliar herbivory

To evaluate the variables of herbivory and defense in B. brevipes, we randomly collected 30 fully expanded leaves from each of the 58 individuals (n = 1,200 leaves). These leaves were identified and transported fresh in a thermal bag to the laboratory, where they were scanned at 300 dpi in a flatbed scanner (HP

® LaserJet Pro MFP M127fn). Subsequently, we used the digital images to estimate the percentage of leaf area consumed by chewing insects for each plant [

22], calculated as the mean proportion of area removed by chewers (cm²) and total leaf area (cm²). We also analyzed the incidence of

S. macrocapillata on all sampled leaves. For this, each gall was opened, and the number of gall inducers was counted based on the number of larval chambers. This method ensured the data sampling accuracy, as the galls of this species are unilocular but occur in clusters on leaves [

47]. The identification of the gall-inducing species was confirmed using the color, shape, and hairiness of the galls, as described in [

48]. Additionally, we counted the number of HR marks, considering their color, shape, and position: brown circular marks on the adaxial surface of the leaves [

49].

4.4. Quantification of foliar silicon content

To evaluate whether foliar Si concentration is related to leaf damage caused by chewing and gall-inducing insects, we analyzed the silicon content in four sets of leaves: (1) 15 full healthy (i.e., without leaf damage caused by herbivores or pathogens) expanded leaves of 40 random plants (n = 600 leaves); (2) the same set of leaves to analyze herbivory by chewing insects (n = 600); (3) in a total of 50 leaves with S. macrocapilata galls, where we separated the galls from the leaf lamina and conducted the silicon analysis in both the gall tissue and the adjacent foliar tissue; and (4) in a total of 50 leaves with HR marks and no evidence of damage from herbivores or pathogens. We sampled only 50 leaves to evaluate the Si from galls and HR due to the low number of sampled plants of B. brevipes attacked by S. macrocapilata (10 plants).

We conducted the foliar silicon analyses at the Laboratório de Análise de Fertilizantes (LAFER) of the Institute of Agricultural Sciences at the Federal University of Uberlândia (UFU). All leaves were placed in an oven at an average temperature of 50°C for 72 hours to completely extract the water content, and then the leaves were ground using a Willey mill. Finally, we analyzed the foliar Si concentration following the methods proposed by [

50].

4.5. Data analysis

We used the

‘describe’ function from the “psych” [

51] package to obtain descriptive statistics for our data. To test the effect of leaf silicon content on the occurrence of gall-inducing arthropods in

B. brevipes, we constructed a generalized linear model (GLM) with a Poisson distribution, where the number of galls was set as the response variable and the mean silicon content in leaves was included as the predictor variable.

To evaluate whether silicon content mediates defense mechanisms against chewing herbivores and gall-inducing insects in B. brevipes, we built GLMs with a Gaussian distribution. In these models, the defense rate, the number of HR, and the individual herbivory rate were used as response variables, while the average silicon content in leaves was the predictor variable.

To test for variation in silicon content across different tissue types, we used a GLM with a Gaussian distribution, where silicon content in the tissue was the response variable and tissue type (gall-bearing leaf, healthy leaf, hypersensitivity reaction-bearing leaf, or gall tissue) was the predictor variable.

To assess the effect of silicon on the relationship between the number of galls and herbivory by chewing herbivores in B. brevipes individuals, we constructed a GLM with a Poisson distribution. In this model, the number of galls was the response variable, and the herbivory rate on leaves was the predictor variable.

Models were simplified to their most parsimonious forms based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Diagnostic checks were conducted using residual plots to assess model fit, and dispersion parameters were examined to verify appropriateness of the chosen distributions. For significant models, we calculated the R

2 using the

‘rsquared’ function from the

piecewiseSEM [

52] package. All analyses were performed in the R environment (version 4.3.1) [

53], and all graphs were generated using the ‘ggplot’ function from the

ggplot2 package [

54].

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the complex role of silicon (Si) in plant defense, particularly in its differential impact on external versus internal herbivores. While Si effectively reduces herbivory by chewing insects through its biomechanical effects, it appears less effective against gall-inducing insects. This paradox suggests that endophytic herbivores, such as gall-inducing insects, may circumvent or manipulate the plant’s silicon defenses, potentially by redistributing silicon within the plant tissues. Furthermore, our findings underscore the role of silicon in enhancing hypersensitivity reactions to gall-inducing insects, providing additional evidence for its multifaceted function in plant defense.

Our results contribute to the growing body of literature on silicon’s role in plant-herbivore interactions and suggest that its protective effects may be more nuanced than previously understood. While silicon may reinforce mechanical defenses, its impact on biochemical defenses and endophytic herbivores requires further exploration. Understanding how gall-inducing insects interact with silicon-rich plants could provide new and important insights into the adaptive strategies of both plants and insect herbivores. Future studies should focus on the molecular mechanisms underlying these interactions, including how silicon affects the redistribution of resources within plants and influences defense signaling pathways. Additionally, examining the role of silicon in other plant species and ecosystems could help to generalize our findings and refine its potential applications in integrated pest management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.S.; methodology, G.R.D., H.V., J.B.C., and J.C.S.; formal analysis, G.R.D.; investigation, G.R.D., H.V., J.B.C., and J.C.S.; resources, J.C.S.; data curation, G.R.D., H.V., and J.C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.R.D; writing—review and editing, G.R.D, H.V., and J.C.S.; supervision, J.C.S.; funding acquisition, J.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research was supported by grants from Brazilian federal funding agency Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), grant numbers No. 486742/2012-1; 316489/2021-2 awarded to J.C.S., and 153399/2024-4 to H.V. This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil (CAPES), Finance Code 001.

Data Availability Statement

All data will be available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank staff (J. F. Andrade) of the Laboratory of Ecology and Biodiversity (LEBIO) for field and laboratorial support. Federal University of Uberlandia for providing adequate infrastructure for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors consent to the publication of the article and its data in this journal.

References

- Poelman, E.H.; Kessler, A. Keystone herbivores and the evolution of plant defenses. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21(6), 477-485. [CrossRef]

- Zangerl, A.R. Evolution of induced plant responses to herbivores. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2003, 4(1), 91-103. [CrossRef]

- Dirzo, R.; Boege, K. Patterns of herbivory and defense in tropical dry and rain forests. In Tropical Forest Community Ecology; Carson, W.P., Schnitzer, S.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: West-Sussex, United Kingdom, 2008, pp. 63-78. Available online: https://propedeuticoecologiatropical10.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/tropical-forest-community-ecology.pdf (accessed on 14-11-2024).

- Gong, B.; Zhang, G. Interactions between plants and herbivores: A review of plant defense. Acta Ecol Sinica. 2014, 34(6), 325-336. [CrossRef]

- Salgado-Luarte, C.; González-Teuber, M.; Madriaza, K.; Gianoli, E. Trade-off between plant resistance and tolerance to herbivory: mechanical defenses outweigh chemical defenses. Ecology. 2023, 104(1), e3860. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.W. Hypersensitivity: a neglected plant resistance mechanism against insect herbivores. Environ. Entomol. 1990, 19(5), 1173-1182. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.W.; Negreiros, D. The occurrence and effectiveness of hypersensitive reaction against galling herbivores across host taxa. Ecol. Entomol. 2001, 26(1), 46-55. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.F., Calixto, E.S., Demetrio, G.R., Venâncio, H., Meiado, M.V., de Santana, D.G., Cuevas-Reyes, P.; Almeida, W.R.; Santos, J.C. Tolerance mitigates gall effects when susceptible plants fail to elicit induced defense. Plants. 2024, 13(11), 1472. [CrossRef]

- Debona, D.; Rodrigues, F.A.; Datnoff, L.E. Silicon’s role in abiotic and biotic plant stresses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2017. 55(1), 85-107. [CrossRef]

- Coskun, D.; Deshmukh, R.; Sonah, H.; Menzies, J.G.; Reynolds, O.; Ma, J.F.; Kronzucker, H.J.; Bélanger, R.R. The controversies of silicon’s role in plant biology. New Phytol., 2019, 221, 67-85. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, N.; de Tombeur, F.; Walgraffe, Y.; Cornélis, J.T.; Verheggen, F.J. Silicon and plant natural defenses against insect pests: impact on plant volatile organic compounds and cascade effects on multitrophic interactions. Plants. 2019, 8, 444. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, O.L.; Padula, M.P.; Zeng, R.; Gurr, G.M. Silicon: potential to promote direct and indirect effects on plant defense against arthropod pests in agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 744. [CrossRef]

- Keeping, M.G.; Kvedaras, O.L. Silicon as a plant defence against insect herbivory: response to Massey, Ennos and Hartley. J Anim. Ecol. 2008, 77(3), 631-633. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, A.; Hartley, S.; Singh, I.K. Silicon: its ameliorative effect on plant defense against herbivory. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71(21), 6730-6743. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.N.; Rowe, R.C.; Hall, C.R. Silicon is an inducible and effective herbivore defence against Helicoverpa punctigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in soybean. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2020, 110(3), 417-422. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Waterman, J.; Hartley, S.; Cooke, J.; Ryalls, J.; Lagisz, M.; Nakagawa, S. Plant silicon defences suppress herbivore performance, but mode of feeding is key. Ecol. Lett. 2024, 27, e14519. [CrossRef]

- Klotz, M.; Schaller, J.; Engelbrecht, B.M. Silicon-based anti-herbivore defense in tropical tree seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1250868. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Han, Y.; Li, P.; Li, F.; Ali, S.; Hou, M. Silicon amendment is involved in the induction of plant defense responses to a phloem feeder. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4232. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, T.G. Fernandes, G.W. Patterns of attack by herbivores on the tropical shrub Bauhinia brevipes (Leguminosae): Vigour or chance?. Eur. J. Entomol. 2001, 98 (1), 37-40. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, T.; Fernandes, G.W.; Coelho, M.S. Induced responses in the neotropical shrub Bauhinia brevipes Vogel: does early season herbivory function as cue to plant resistance?. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2011, 5, 245-253. [CrossRef]

- Marinho, C.R.; Oliveira, R.B.; Teixeira, S. P. The uncommon cavitated secretory trichomes in Bauhinia ss (Fabaceae): the same roles in different organs. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 180(1), 104-122. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.F.; Batista, J.C.; Pereira, H.S.; Fernandes, G.W.; Santos, J.C. Fire mediated herbivory and plant defense of a neotropical shrub. Arthropod-Plant Inte. 2019, 13, 489-498. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.; Silveira, F.A.O.; Fernandes, G.W. Long term oviposition preference and larval performance of Schizomyia macrocapillata (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) on larger shoots of its host plant Bauhinia brevipes (Fabaceae). Evol. Ecol. 2008, 22, 123–137. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.; Alves-Silva, E.; Cornelissen, T.G.; Fernandes, G.W. Differences in leaf nutrients and developmental instability in relation to induced resistance to a gall midge. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2017, 11, 163–170. [CrossRef]

- Vandegeer, R.K.; Cibils-Stewart, X.; Wuhrer, R.; Hartley, S.E.; Tissue, D.T.; Johnson, S.N. Leaf silicification provides herbivore defence regardless of the extensive impacts of water stress. Funct. Ecol. 2021, 35(6), 1200-1211. [CrossRef]

- Waterman, J.M.; Cibils-Stewart, X.; Cazzonelli, C.I.; Hartley, S.E.; Johnson, S.N. Short-term exposure to silicon rapidly enhances plant resistance to herbivory. Ecology 2021, 102(9), e03438. [CrossRef]

- Bhavanam, S.; Stout, M.J. Assessment of Silicon- and mycorrhizae- mediated constitutive and induced systemic resistance in rice, Oryza sativa L., against the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda Smith. Plants 2021, 10, 2126. [CrossRef]

- Alhousari, F.; Greger, M. Silicon and mechanisms of plant resistance to insect pests. Plants 2018, 7, 33. [CrossRef]

- Frew, A.; Weston, L.A.; Reynolds, O.L.; Gurr, G.M. The role of silicon in plant biology: a paradigm shift in research approach. Ann. Bot. 2018, 121(7), 1265-1273. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, F.E.; Peiffer, M.; Ray, S.; Tan, C.W.; Felton, G.W. Silicon-Mediated Enhancement of Herbivore Resistance in Agricultural Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 631824. [CrossRef]

- Espírito-Santo, M.M.; Fernandes, G. W. How many species of gall-inducing insects are there on earth, and where are they?. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2007, 100(2), 95-99. [CrossRef]

- Cintra, F.C.F.; Araújo, W.S.D.; Maia, V.C.; Guimarães, M.V.U.; Venâncio, H.; Andrade, J.F.; Carneiro, M.A.A.; Almeida, W.R.; Santos, J.C. Plant-galling insect interactions: a data set of host plants and their gall-inducing insects for the Cerrado. Ecology 2020, 101(11), e03149. [CrossRef]

- Massad, T.J. Plant defences as functional traits: A comparison across savannas differing in herbivore specialization. J. Ecol. 2023, 111(12), 2552-2567. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.; Maldonado-López, Y.; Venâncio, H.; Almeida, W.R.; Felício, D.T.; Cintra, F.C.F.; Barros, L.O.; Reis, R.A.; Moreira, T.R.; Costa-Silva, V.M.; Cuevas-Reyes, P. Interspecific competition drives gall-inducing insect species distribution on leaves of Matayba guianensis Aubl. (Sapindaceae). Ecol. Entomol. 2021, 46, 1059-1071. [CrossRef]

- Nyman, T.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R. Manipulation of the phenolic chemistry of willows by gall-inducing sawflies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000, 97(24), 13184-13187. [CrossRef]

- Kuster, V.C.; Rezende, U.C.; Cardoso, J.C.F.; Isaias, R.M.S., Oliveira, D.C. How Galling Organisms Manipulate the Secondary Metabolites in the Host Plant Tissues? A histochemical overview in Neotropical gall systems. In Co-Evolution of Secondary Metabolites, Reference Series in Phytochemistry; Mérillon, J.M., Ramawat, K., Eds., Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 823-842. [CrossRef]

- Hartley, S. The chemical composition of plant galls: are levels of nutrients and secondary compounds controlled by the gall-former?. Oecologia, 1998, 113, 492–501. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.N.; Hartley, S.E.; Ryalls, J.M.W.; Frew, A.; Hall, C.R. Targeted plant defense: Silicon conserves hormonal defense signaling impacting chewing but not fluid-feeding herbivores. Ecology 2021, 102(3), e03250.

- Giron, D.; Huguet, E.; Stone, G.N.; Body, M. Insect-induced effects on plants and possible effectors used by galling and leaf-mining insects to manipulate their host-plant. J. Insect Physiol. 2016, 84, 70-89. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hua, H.; Zhu, Y.G.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, C.; Römheld, V. Importance of plant species and external silicon concentration to active silicon uptake and transport. New Phytol. 2006, 172(1), 63-72. [CrossRef]

- Pontigo, S.; Ribera, A.; Gianfreda, L.; Mora, M.L.; Nikolic, M.; Cartes, P. Silicon in vascular plants: uptake, transport and its influence on mineral stress under acidic conditions. Planta 2015, 242, 23–37. [CrossRef]

- Murali-Baskaran, R.K.; Senthil-Nathan, S.; Hunter, W.B. Anti-herbivore activity of soluble silicon for crop protection in agriculture: a review. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 2021, 28(3), 2626-2637. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.V.S.; Raupp, P.P.; Cardoso, J.C.F.; Oliveira, D.C. Dinâmica de vegetação e caracterização das fitofisionomias da Reserva Ecológica do Panga, In Aspectos da história natural da Reserva Ecológica do Panga, 1 ed.; Jacobucci, G.B.; Oliveira, P.E.; Costa, A.N. Orgs. 2023; UFU: Uberlândia, MG, pp. 190-199. Available online: https://ufubr-my.sharepoint.com/personal/ecologia_umuarama_ufu_br/_layouts/15/onedrive.aspx?id=%2Fpersonal%2Fecologia%5Fumuarama%5Fufu%5Fbr%2FDocuments%2FPPGECB%2FSECRETARIA%2FCURSO%20DE%20CAMPO%2F2023%20ASPECTOS%20DA%20HIST%C3%93RIA%20NATURAL%20DA%20RESERVA%20ECOL%C3%93GICA%20DO%20PANGA%202023%2Epdf&parent=%2Fpersonal%2Fecologia%5Fumuarama%5Fufu%5Fbr%2FDocuments%2FPPGECB%2FSECRETARIA%2FCURSO%20DE%20CAMPO&ga=1 (accessed on 22-11-2024).

- Moreno, M.I.C.; Schiavini, I. Relação entre vegetação e solo em um gradiente florestal na Estação Ecológica do Panga, Uberlândia (MG). Braz. J. Bot. 2001, 24, 537-544. [CrossRef]

- Silveira, F.A.O; Santos, J.C; Franceschinelli, E.V; Morellato, L.P.C; Fernandes, G.W. Costs and benefits of reproducing under unfavorable conditions: an integrated view of ecological and physiological constraints in a cerrado shrub. Plant Ecol. 2015, 216, 963-974. [CrossRef]

- Hanley, M.E.; Lamont, B.B.; Fairbanks, M.M.; Rafferty, C. M. Plant structural traits and their role in anti-herbivore defense. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2007, 8(4), 157-178. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Silva, J.; Araujo, T. J. Are Fabaceae the principal super-hosts of galls in Brazil?. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2020, 92, 436 e20181115. [CrossRef]

- Maia, V.C.; Fernandes, G.W. Two new species of Asphondyliini (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) associated with Bauhinia brevipes (Fabaceae) in Brazil. Zootaxa. 2005, 1091(1), 27–40. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes G.W.; Cornelissen T.G.; Lara T.A.F.; Isaias R.M.S. Plants fight gall formation: hypersensitivity. Ciênc. Cult. 2000, 52, 49-54.

- Korndörfer, G.G.; Pereira, H.S.; Nola, A. Análise de silício: solo, planta e fertilizante; ICIAG-UFU: Uberlândia, Brazil, 2004, 34p.

- Revelle, W. psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Northwestern University: Evanston, Illinois. R package version 2.4.3, 2024. Available on: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych.

- Lefcheck, J.S. piecewiseSEM: Piecewise structural equation modeling in R for ecology, evolution, and systematics. Met. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7(5), 573-579. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. 2023. Available on: https://www.R-project.org/.

- H. Wickham. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: Verlag, New York, 2016.

Figure 1.

Bauhinia brevipes system: (A) mature and (B) young galls of Schizomyia macrocapillata Maia, 2005 (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae), (C) a cross-sectional view detailing the inducer (orange larvae) in the gall center, (D) leaf exhibiting hypersensitivity reactions (HRs), (E) HR in detail, and (F) leaf displaying herbivory by chewing insects juxtaposed with an undamaged leaf.

Figure 1.

Bauhinia brevipes system: (A) mature and (B) young galls of Schizomyia macrocapillata Maia, 2005 (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae), (C) a cross-sectional view detailing the inducer (orange larvae) in the gall center, (D) leaf exhibiting hypersensitivity reactions (HRs), (E) HR in detail, and (F) leaf displaying herbivory by chewing insects juxtaposed with an undamaged leaf.

Figure 2.

Scatter plots showing the positive relationship between silicon content and the number of hypersensitivity reactions (HRs) (A), and the negative relationship between silicon content and the herbivory rate (B) in Bauhinia brevipes leaves. Data suggest that higher silicon content enhances the HR response, while increasing silicon content correlates with reduced damage by chewing herbivores. The shaded areas represent the confidence intervals. The GLM fit for both models is shown with statistical significance indicated (p<0.05 for HR, p<0.01 for herbivory rate).

Figure 2.

Scatter plots showing the positive relationship between silicon content and the number of hypersensitivity reactions (HRs) (A), and the negative relationship between silicon content and the herbivory rate (B) in Bauhinia brevipes leaves. Data suggest that higher silicon content enhances the HR response, while increasing silicon content correlates with reduced damage by chewing herbivores. The shaded areas represent the confidence intervals. The GLM fit for both models is shown with statistical significance indicated (p<0.05 for HR, p<0.01 for herbivory rate).

Figure 3.

Box plots illustrating the distribution of silicon content in different leaf tissue types: healthy, galled, with hypersensitivity reactions, and gall tissue. The analysis indicates that galled and hypersensitivity reaction-bearing tissues exhibit significantly higher silicon content than healthy leaves and gall tissues. The statistical differences between tissue types were assessed using GLMs with a Gaussian distribution and are marked accordingly.

Figure 3.

Box plots illustrating the distribution of silicon content in different leaf tissue types: healthy, galled, with hypersensitivity reactions, and gall tissue. The analysis indicates that galled and hypersensitivity reaction-bearing tissues exhibit significantly higher silicon content than healthy leaves and gall tissues. The statistical differences between tissue types were assessed using GLMs with a Gaussian distribution and are marked accordingly.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot showing the negative correlation between herbivory rate and the number of galls per leaf in Bauhinia brevipes. Higher herbivory rates were associated with fewer galls, suggesting that herbivore damage may inhibit gall formation. The model fit is based on a Poisson-distributed GLM, with statistical significance indicated (p<0.01). The shaded area represents the confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot showing the negative correlation between herbivory rate and the number of galls per leaf in Bauhinia brevipes. Higher herbivory rates were associated with fewer galls, suggesting that herbivore damage may inhibit gall formation. The model fit is based on a Poisson-distributed GLM, with statistical significance indicated (p<0.01). The shaded area represents the confidence interval.

Table 1.

Results from generalized linear models (GLM) showing the relationship between mean silicon content in leaves and plant defense mechanisms in Bauhinia brevipes. The defense mechanisms measured include the defense rate (percentage of defensive tissue response), the number of hypersensitivity reactions (HR), and the herbivory rate (% damage). Silicon content was found to positively influence HR and negatively affect herbivory by chewing herbivores. No significant correlation was found between silicon and the overall defense rate. p values were derived using GLMs with Gaussian distribution, and significant values (α=0.05) are presented in bold.

Table 1.

Results from generalized linear models (GLM) showing the relationship between mean silicon content in leaves and plant defense mechanisms in Bauhinia brevipes. The defense mechanisms measured include the defense rate (percentage of defensive tissue response), the number of hypersensitivity reactions (HR), and the herbivory rate (% damage). Silicon content was found to positively influence HR and negatively affect herbivory by chewing herbivores. No significant correlation was found between silicon and the overall defense rate. p values were derived using GLMs with Gaussian distribution, and significant values (α=0.05) are presented in bold.

| Response Variable |

Source of Variation |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

t Value |

P Value |

R² |

Number of HR

reactions |

Intercept |

1.579 |

1.017 |

1.553 |

0.1261 |

- |

Mean silicon

content |

15.587 |

7.568 |

2.060 |

0.0441 |

0.97 |

Herbivory

rate (%) |

Intercept |

9.220 |

2.772 |

3.326 |

0.0015 |

- |

Mean silicon

content |

-52.621 |

21.649 |

-2.431 |

0.0183 |

0.09 |

Table 2.

Variation in silicon content among different leaf tissue types (healthy leaf, galled leaf, leaf with hypersensitivity reactions, and gall tissue). Galled and hypersensitivity reaction-bearing leaves showed significantly higher silicon content than gall tissues and healthy leaves. Significant differences in silicon content were assessed using GLMs with a Gaussian distribution, with a focus on tissue types as predictor variables. Significant p values (α=0.05) are presented in bold.

Table 2.

Variation in silicon content among different leaf tissue types (healthy leaf, galled leaf, leaf with hypersensitivity reactions, and gall tissue). Galled and hypersensitivity reaction-bearing leaves showed significantly higher silicon content than gall tissues and healthy leaves. Significant differences in silicon content were assessed using GLMs with a Gaussian distribution, with a focus on tissue types as predictor variables. Significant p values (α=0.05) are presented in bold.

| Comparison |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

z Value |

P Value |

| Gall versus healthy leaves |

0.014 |

0.008 |

1.75 |

0.297 |

| Gall-bearing leaves versus Healthy leaves |

0.04 |

0.008 |

5.00 |

< 0.001 |

| Leaves with HR versus Healthy leaves |

0.036 |

0.008 |

4.50 |

<0.001 |

| Gall-bearing leaves versus Gall |

0.026 |

0.008 |

3.25 |

<0.01 |

| Leaves with HR versus Gall |

0.022 |

0.008 |

2.75 |

<0.05 |

Table 3.

Results from generalized linear models (GLM) showing the relationship between herbivory rate and the number of galls per leaf in Bauhinia brevipes. The data reveal that as herbivory increases, the number of galls decreases, suggesting a potential trade-off between herbivory and gall formation. The analysis was conducted using a Poisson distribution, where the herbivory rate was the predictor variable. Statistically significant p-values (α = 0.05) are presented in bold. .

Table 3.

Results from generalized linear models (GLM) showing the relationship between herbivory rate and the number of galls per leaf in Bauhinia brevipes. The data reveal that as herbivory increases, the number of galls decreases, suggesting a potential trade-off between herbivory and gall formation. The analysis was conducted using a Poisson distribution, where the herbivory rate was the predictor variable. Statistically significant p-values (α = 0.05) are presented in bold. .

| Source of Variation |

Estimate |

Std. Error |

z Value |

P Value |

R² |

| Intercept |

1.741 |

0.072 |

24.185 |

< 0.001 |

- |

| Herbivory rate (%) |

-0.063 |

0.021 |

-3.012 |

0.002 |

0.16 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).