Submitted:

19 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Ethical Procedures

2.3. Sample Size Estimation

2.4. Data Collection Instruments

- A.

- Socio-demographic data – Data were collected at the time of enrollment. The variables included age, gender, religion, occupation, residence, education, income, etc.

- B.

- Details of RTA, type of injury, and clinical data – Data were collected during the hospital stay of the victim. According to the type of accident, RTAs were divided into motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), non-MVAs, pedestrian accidents, and passenger accidents. MVAs include car accidents, motorcycle accidents, tram accidents, tractor accidents, special mechanical accidents, etc. Non-MVAs consisted of rickshaw accidents, bicycle accidents, etc. Pedestrian and/or passenger accidents refer to accidents in which pedestrians and/or passengers were primarily responsible.

- C.

- Follow-up data: Four types of data instruments were vital for the outcome measurements of this study. They included 1) Disability Assessment by using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) [14]; 2) PTSD Checklist for DSM 5 (PCL-5) [16]; 3) Social Impact Data; and 4) Economic Impact Data.

WHODAS 2.0 Scale

PCL-5 Checklist (for PTSD)

Assessment of the Socioeconomic Impact of RTA

- 1)

- Social Impact Data – The questions were as follows: Was the victim being neglected by family/friends/neighbors/other acquaintances following RTA?; Was the victim made fun of/insulted by others following the RTA? Did the victim receive any rehabilitative services?

- 2)

- Economic Impact Data – There were 8 questions related to absence from a job, reduced workload, change of job, wage loss, and out-of-pocket expenses. Each item under the socioeconomic impact domain was given a score of ‘1’ for a ‘yes or positive’ response, and ‘0’ for a no or negative response

2.5. The Study Protocol

The study was carried out in four phases:

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Status

3.2. Type of Injuries

3.3. Disability Status

3.4. PTSD

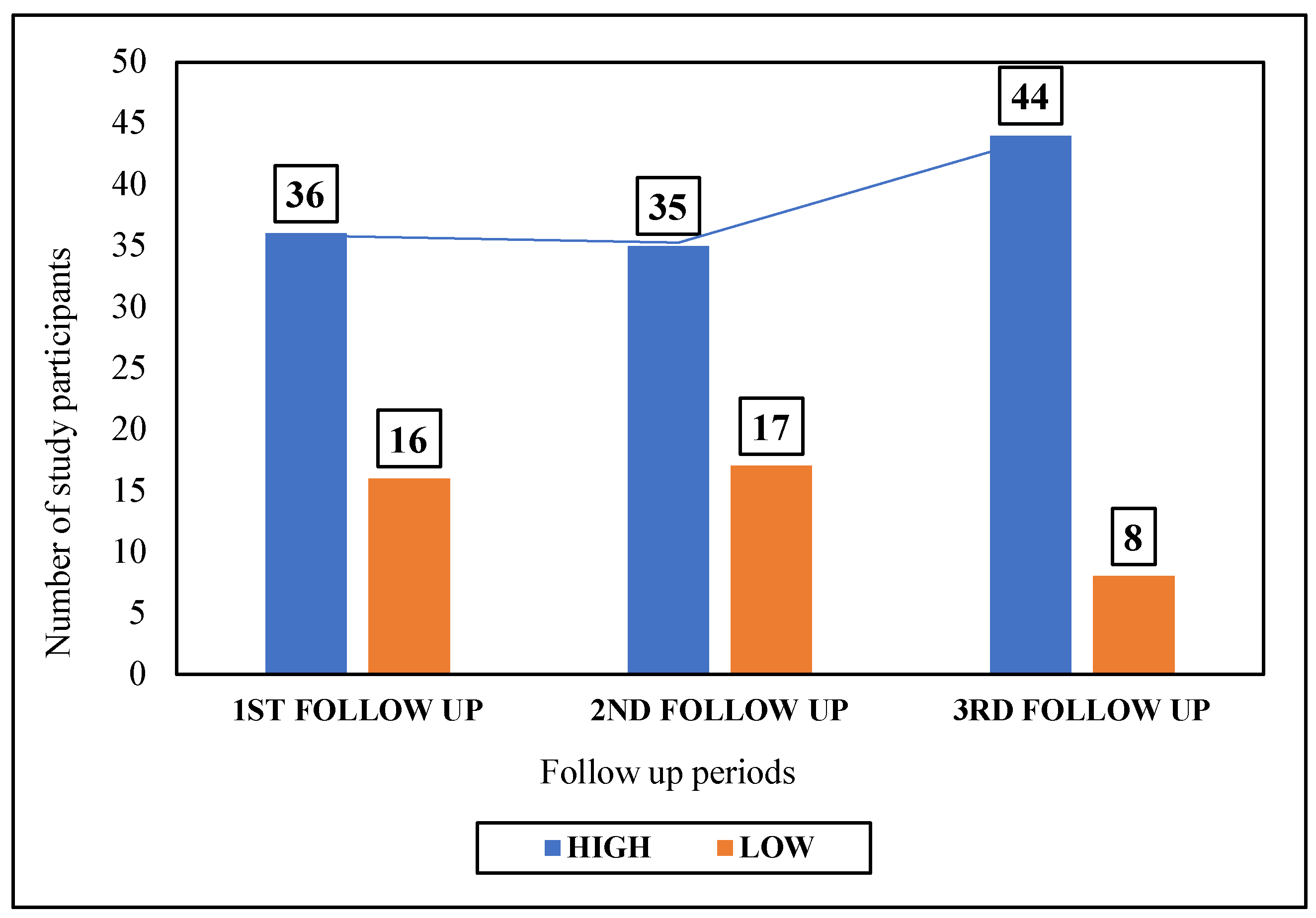

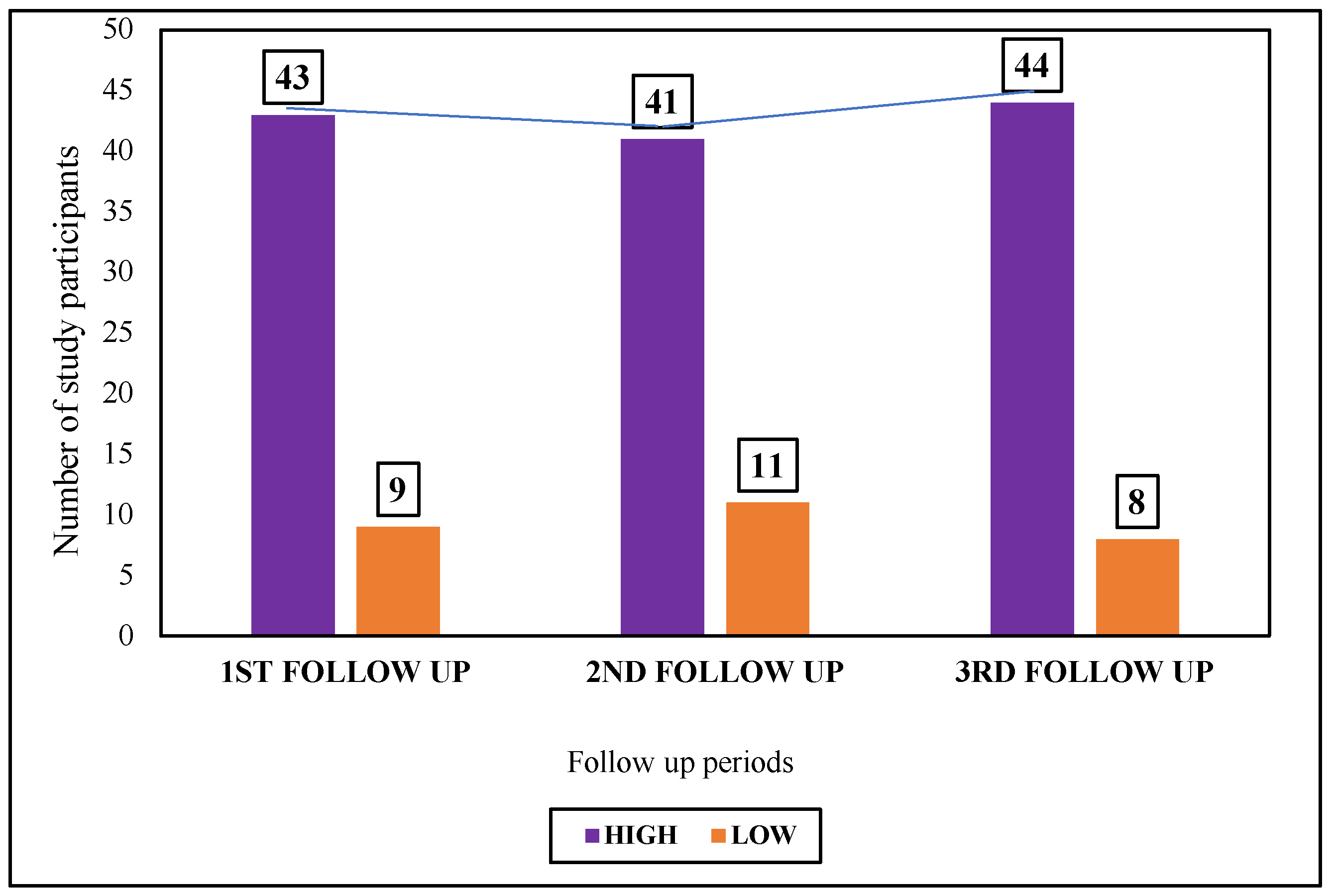

3.5. Social Impact

3.6. Economic Impact

4. Discussion

4.1. Disability

4.2. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

4.3. Economic Impact of RTA

4.4. Social Impact of RTA

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

PART I: Socio-Demographic Profile of the Study Participants

- a)

- Age (in completed years)-

- b)

- Gender: Male/ Female/ others (specify)-

- c)

- Residence- Urban/Rural

- d)

- Living with- Alone/ Family

- e)

- Religion- Hindu/Muslim/Christian/Others (specify)

- f)

- Marital status- Married/ unmarried/ others (specify)

- g)

- Highest level of education- Illiterate/ non-formal education/ primary/ middle school/ secondary/ higher secondary and above

- h)

- Occupation- Unemployed/ Employed (specify)-

- i)

- Total family income per month (in Rs.)-

- j)

- Number of family members-

- k)

- Socio-economic status (as per Modified B.G. Prasad Scale, 2022)-

- l)

- Health insurance- Present/Absent

- m)

- Addiction history- Present/Absent

- n)

- Whether under the influence of any abusive substance at the time of accident? – Yes/No

- o)

- Socio-cultural problems in family- Present/Absent

PART II: Details of RTA and the Clinical Profile of Admitted Patients

- a)

- Date of accident-

- b)

- Place of accident- Street/ Highway/ Lane

- c)

- Time of accident-

- d)

- Date and Time of admission at the Level I Trauma Centre of IPGME&R-

- e)

- Any environmental factors leading to the RTA? – Yes/ No

- Bad road conditions- Yes/No

- Poor weather conditions – Yes/ No

- Defective vehicle conditions – Yes/ No

- f)

- Mechanism of injury following accident (multiple responses):

- i)

- Fall from vehicle- Yes/No

- ii)

- Skidding while driving- Yes/No

- iii)

- Getting hit by another vehicle- Yes/No

- g)

- Type of injury following accident (multiple responses):

- i)

- Fracture- Yes/No

- name of fractured bone (including skull fracture if any)-

- type of fracture- displaced/not displaced

- ii)

- Dislocation- Yes/No

- Name of affected bone-

- iii)

- Head injury- Yes/No

- hemorrhage/ cerebral contusion/ cerebral concussion/ others (specify)-

- iv)

- Blunt trauma: Yes/No

- Site on the body –

- Any rupture of viscera- Yes/ No

- Whether there was any internal bleeding? – Yes/No

- v)

- Amputation: Yes/No

- Which part of the body (specify)

- h)

- Consciousness level following accident- Conscious/ Unconscious

- i)

- GCS at the time of admission at the Level I Trauma Centre-

- j)

- Whether the victim was-

- A pedestrian- Yes/ No

- Inside a vehicle- Yes/No

- type of vehicle in which the victim was travelling:

- Two-wheeler- Yes/ No

- Three-wheeler - Yes/ No

- Four-wheeler – Yes/No

- Was the victim driving the vehicle? – Yes/ No

- Before admission in the Level I Trauma Centre, whether taken to any other health facility- Yes/No

- Name of the facility-

- Distance of the facility from the site of accident-

- Whether went alone or accompanied by someone to the facility- Alone/ Accompanied by someone (specify)-

- Time of attendance at the facility-

- Received treatment at the facility- Yes/No

- Whether referred to the Level I Trauma Centre of IPGME&R? – Yes/No

- Whether undergone any major surgery following the accident? Yes/No

- Was the victim admitted to the Critical Care unit (ICU/HDU) at any point following admission? – Yes/ No

PART III: Follow-Up Data Collection (1ST, 2ND AND 3RD)

- a)

- Concentrating in doing something for 10 mins?

- b)

- Remembering to do important things?

- c)

- Analysing and finding solutions to problems in day-to-day life?

- d)

- Learning a new task, for example, learning how to get to a new place?

- e)

- Generally understanding what people say?

- f)

- Starting and maintaining a conversation?

- a)

- Standing for long periods such as 30 minutes?

- b)

- Standing up from sitting down?

- c)

- Moving around inside your home?

- d)

- Getting out of your home?

- e)

- Walking a long distance such as a kilometre [or equivalent]?

- a)

- Washing your whole body?

- b)

- Getting dressed?

- c)

- Eating?

- d)

- Staying by yourself for few days?

- a)

- Dealing with people you do not know?

- b)

- Maintaining a friendship?

- c)

- Getting along with people who are close to you?

- d)

- Making new friends?

- e)

- Sexual activities?

- a)

- Taking care of your household responsibilities?

- b)

- Doing most important household tasks well?

- c)

- Getting all the household work done that you needed to do?

- d)

- Getting your household work done as quickly as needed?

- e)

- Your day-to-day work/school?

- f)

- Doing your most important work/school tasks well?

- g)

- Getting all the work done that you need to do?

- h)

- Getting your work done as quickly as needed?

- a)

- How much of a problem did you have joining in community activities (for example, festivities, religious or other activities) in the same way anyone else can?

- b)

- How much of a problem did you have because of barriers or hindrances in the world around you?

- c)

- How much of a problem did you have living with dignity because of the attitudes and actions of others?

- d)

- How much time did you spend on your health condition, or its consequences?

- e)

- How much have you been emotionally affected by your health condition?

- f)

- How much has your health been a drain on the financial resources of you or your family?

- g)

- How much of a problem did your family have because of your health problems?

- h)

- How much of a problem did you have in doing things by yourself for relaxation or pleasure?

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Extreme/Cannot do |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Questions |

Not at all 0 |

Little bit 1 |

Moderately 2 |

Quite a bit 3 |

Extremely 4 |

| 1. Repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of the stressful experience? | |||||

| 2. Repeated, disturbing dreams of the stressful experience? | |||||

| 3. Suddenly feeling or acting as if the stressful experience were actually happening again (as if you were actually back there reliving it)? | |||||

| 4. Feeling very upset when something reminded you of the stressful experience? | |||||

| 5. Having strong physical reactions when something reminded you of the stressful experience (for example, heart pounding, trouble breathing, sweating)? | |||||

| 6. Avoiding memories, thoughts, or feelings related to the stressful experience? | |||||

| 7. Avoiding external reminders of the stressful experience (for example, people, places, conversations, activities, objects, or situations)? | |||||

| 8. Trouble remembering important parts of the stressful experience? | |||||

| 9. Having strong negative beliefs about yourself, other people, or the world (for example, having thoughts such as: I am bad, there is something seriously wrong with me, no one can be trusted, the world is completely dangerous)? | |||||

| 10. Blaming yourself or someone else for the stressful experience or what happened after it? | |||||

| 11. Having strong negative feelings such as fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame? | |||||

| 12. Loss of interest in activities that you used to enjoy? | |||||

| 13. Feeling distant or cut off from other people? | |||||

| 14. Trouble experiencing positive feelings (for example, being unable to feel happiness or have loving feelings for people close to you)? | |||||

| 15. Irritable behavior, angry outbursts, or acting aggressively? | |||||

| 16. Taking too many risks or doing things that could cause you harm? | |||||

| 17. Being “super alert” or watchful or on guard? | |||||

| 18. Feeling jumpy or easily startled? | |||||

| 19. Having difficulty concentrating? | |||||

| 20. Trouble falling or staying asleep? |

- A.

- Social Impact:

- Was the victim being neglected by family/friends/neighbors/other acquaintances following RTA? – Yes/No

- Was the victim made fun of/ being insulted by others following the RTA- Yes/No

- Did the victim receive any rehabilitative services? – Yes/No. If yes, specify-

- B.

- Economic Impact:

- For how many days was the victim absent from his job following the accident?

- Any loss of wages of the victim following the RTA? – Yes/No

- Has the performance of the victim reduced at the workplace following the accident? – Yes/ No

- Did the victim opt for a different job following the accident? – Yes/No

- 5.

- How much money was spent for treatment following the accident (hospital admission+ follow-up visits) in Rs. -

- 6.

- Did the victim get any accident policy/ claim for treatment? – Yes/No

- 7.

- Did the victim take any loan for treatment following the accident? – Yes/ No

- 8.

- Was there any out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure of the victim due to RTA? – Yes/ No. If yes:

- OOP during hospital admission (in Rs.) –

- OOP during follow-up (in Rs.) –

Appendix B

| Item No | Recommendations | Page No. | Relevant text | |

| Title and abstract | 1 | (a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract: Mentioned as ‘follow up study’ | 1 | The title includes the following: “A 6-month follow-up study” |

| (b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found: The same mentioned as recommended | 1 | A longitudinal study was conducted for 24 months among 52 hospitalized RTA victims, aged ≥ 18 years, followed up at 1-, 3- and 6 months post-discharge from the hospital. | ||

| Introduction | ||||

| Background/rationale | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported: Mentioned | 2-3 | Lines 41-78. |

| Objectives | 3 | State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses: Objectives mentioned, no prespecified hypotheses given | 3 | This study aimed to address the magnitude of disability, PTSD, and social-, and economic complications among RTA victims within 6 months of post-discharge from a trauma care center of a tertiary care hospital in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. |

| Methods | ||||

| Study design | 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper | 3-4 | Cross-sectional study with 6 months’ follow-up. |

| Setting | 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection |

Setting: Level-I Trauma Care Centre, IPGME&R and SSKM Hospital, Kolkata (India) Period of recruitment Mentioned Follow up periods 6 months Data collection: Details of the instruments are mentioned. |

|

| Participants | 6 | Cross-sectional study—Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants | 3 | Page 3, line 83-87 |

| Variables | 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable. |

4-7 | Outcome variables: disability, PTSD and socioeconomic complications. Predictors: the outcome variables; potential confounders: socioeconomic variables |

| Data sources/ measurement | 8* | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group. |

7-8 | Sources of data for each variable of interest: RTA victims followed up through 6 months post-discharge from the Trauma Care Centre) Comparability of assessment methods: No controls |

| Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias | Not mentioned | |

| Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size was arrived at | 4 | Used the prevalence sample size formula and published data for the baseline (5] Line 96-107 |

| Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why | 5-6 | WHODAS 2.0 scale for disability was grouped into 5 categories. PTSD was grouped into: present or absent. Followed the standard published methods. |

| Statistical methods | 12 | Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control confounding: |

(a) | (b) |

| Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions: | 8 | Not done in the study | ||

| Explain how missing data were addressed | There were no missing data. | |||

| Cross-sectional study—If applicable, describe analytical methods taking account of sampling strategy | 5-8 | Details of the method are described. | ||

| (e) Describe any sensitivity analyses | Not applicable | |||

References

- World Health Organization. Road traffic injuries. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact- sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries, accessed on 24 December 2024.Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196.

- United Nations. Fact Sheet Road Safety. Sustainable Transport Conference, 14-16 October 2021, Beijing. Available online: chrome- extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/media_gstc/FACT_SHEET_Road_safety.pdf, accessed on 24 December 2024. Author 1, A.B.; Author 2, C. Title of Unpublished Work. Abbreviated Journal Name year, phrase indicating stage of publication (submitted; accepted; in press).

- Observer Research Foundation. Why are road accidents in India are on the rise? Available online: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/why-are-road-accidents-in-india-on-the-rise, accessed on 24 December 2024.

- Nanjunda, D.C. Impact of socio-economic profiles on public health crisis of road traffic accidents: A qualitative study from South India. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2021, 9, 7-11.

- Bicholkar, A.; Cacodcar, J.A. A study of road traffic injury victims at a tertiary care hospital in Goa, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022, 11(9):5490-5494. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_693_21. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Sarkar, D.; Mallick, N. A study on the socio-demographic profiles of road traffic accident cases attending a peripheral tertiary care medical College hospital of West Bengal. J Evidence Based Med. 2021, 8(15), 945-949, DOI: 10.18410/jebmh/2021/183. [CrossRef]

- Alghnam, S.; Alkelya, M.; Aldahnim, M.; Aljerian, N.; Albabtain, I.; Alsayari, A.; et al. Healthcare costs of road injuries in Saudi Arabia: A quantile regression analysis. Accid Anal Prev. 2021, 159, 106266.

- Rissanen, R.; Berg, H.Y.8; Hasselberg, M. Quality of life following road traffic injury: A systematic literature review. Accid Anal Prev. 2017, 108, 308-320.

- Papic, C.; Kifley, A.; Craig, A.; Grant, G.; Collie, A.; Pozzato, I.; et al. Factors associated with long term work incapacity following a non-catastrophic road traffic injury: Analysis of a two-year prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2022, 22(1), 1498.

- Jain, M.; Radhakrishnan, R.V.; Mohanty, C.R.; Behera, S.; Singh, A.K.; Sahoo, S.S.; et al. Clinicoepidemiological profile of trauma patients admitting to the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in eastern India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020, 9(9), 4974-79. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_621_20. [CrossRef]

- Ng QX, Soh AYS, Loke W, Venkatanarayanan N, Lim DY, Yeo WS. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The association between post-traumatic stress disorder and irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jan;34(1):68-73. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14446. Epub 2018 Sep 10. PMID: 30144372. [CrossRef]

- Undavalli, C.; Das, P.; Dutt, T.; Bhoi, S.; Kashyap, R. PTSD in post-road traffic accident patients requiring hospitalization in Indian subcontinent: A review on magnitude of the problem and management guidelines. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2014, 7(4), 327-331, doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.142775. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mahima; Srivastava, D.K.; Kharya, P.; Sachan, N.; Kiran, K. Analysis of risk factors contributing to road traffic accidents in a tertiary care hospital. A hospital based cross-sectional study. Chin J Traumatol. 2020, 23(3), 159-62. DOI: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2020.04.005. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Iverson, L.M. Glasgow Coma Scale. [Updated 2023 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513298/ (accessed 10 January 2025).

- Daniel, W.W.; Cross, C.L. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences. 10th edition, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2013.

- World Health Organization. Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. WHODAS 2.0. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/whodas-20-instrument.pdf, accessed on 10 January 2025.

- Abdin E, Seet V, Jeyagurunathan A, Tan SC, Mok YM, Verma S, Lee ES, Subramaniam M. Validation of the 12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 in individuals with schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, and diabetes in Singapore. PLoS One. 2023, 18(11), e0294908. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0294908. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Available online: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp, accessed on 10 January 2025.

- Hall BJ, Yip PSY, Garabiles MR, Lao CK, Chan EWW, Marx BP. Psychometric validation of the PTSD Checklist-5 among female Filipino migrant workers. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10(1), 1571378. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1571378. [CrossRef]

- PCL-5: Scoring and interpretation [Internet]. Comorbidity Guidelines. Available online: https://comorbidityguidelines.org.au/appendix-s-ptsd-checklist-for-dsm5-pcl5/pcl5-scoring-and-interpretation, accessed on 20 November 2024.

- Esiyok, B., Korkusuz, I., Canturk, G., Alkan, H. A., Karaman, A. G., & Hamit Hanci, I. (2005). Road traffic accidents and disability: A cross-section study from Turkey. Disability and Rehabilitation, 27(21), 1333–1338. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280500164867. [CrossRef]

- Bull J.P. Disabilities caused by road traffic accidents and their relation to severity scores. Accid Anal Prev. 1985, 17(5), 387-397, https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-4575(85)90093-4. [CrossRef]

- Palmera-Suárez, R.; López-Cuadrado, T.; Almazán-Isla, J.; Fernández-Cuenca, R.; Alcalde-Cabero, E.; Galán, I. Disability related to road traffic crashes among adults in Spain. Gaceta Sanitaria 2025, 29(1), 43-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2015.01.009. [CrossRef]

- Fekadu, W,; Mekonen, T.; Belete, H.; Belete, A.; Yohannes, K. Incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder after road traffic accident. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00519. [CrossRef]

- Frommberger, U.H.; Stieglitz, R-D.; Nyberg, E.; Schlickewei, W.; Kuner, E. Berger, M. Prediction of posttraumatic stress disorder by immediate reactions to trauma: a prospective study in road traffic accident victims. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998, 228, 316-321.

- Chossegros, L.; Hours, M.; Charnay, P.; Bernard, M.; Fort, E.; Boisson, D.; et al. Predictive factors of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder 6 months after a road traffic accident. Accid Anal Prev. 2011, 43(1), 471-477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2010.10.004. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bagepally, B.S.; Shankara, B.; Sasidharan, A.; Jagadeesh, K.V.; Ponniah, M. State-wise economic burden of road traffic accidents in India. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.21.23300419 Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.12.21.23300419v1.full.pdf, accessed on 12 December 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gorea, R. Financial impact of road traffic accidents on the society. Int J Ethics Trauma Victimology 2016, 2(1):6-9. doi.10.18099/ijetv.v2i1.11129.

- European Transport Safety Council (ETSC). Social and economic consequences of road traffic injury in Europe. Brussels: 2007 p. 23.

- Verma, P.; Gupta, S.; Misra, S.; Agrawal, R.; Agrawal, V.; Singh, G. Road traffic accidents: A lifetime financial blow the victim cripples under. Indian J Community Health. 2015, 27(2):257–262.

- Prinja, S.; Jagnoor, J.; Sharma, D.; Aggarwal, S.; Katoch, S.; Lakshmi, P.V.; et al. Out-of-pocket expenditure and catastrophic health expenditure for hospitalization due to injuries in public sector hospitals in North India. PloS One. 2019, 14(11), e0224721.

- Blincoe, L. J.; Miller, T. R.; Zaloshnja, E.; Lawrence, B. A. The economic and societal impact of motor vehicle crashes, 2010. (Revised) (Report No. DOT HS 812 013). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, May 2025. http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/812013.pdf.

| Socio-demographic Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |

| ≤ 20 | 8 (15.4) |

| 21-30 | 27 (51.9) |

| 31-40 | 6 (11.5) |

| 41-50 | 6 (11.5) |

| ≥ 51 | 5 (9.7) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 12 (23.1) |

| Male | 40 (76.9) |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism | 30 (57.7) |

| Islam | 20 (38.5) |

| Christianity | 2 (3.8) |

| Place of current residence | |

| Rural | 33 (63.5) |

| Urban | 19 (36.5) |

| The highest level of education attained | |

| Illiterate | 9 (17.3) |

| Primary | 8 (15.4) |

| Middle school | 12 (23.1) |

| Secondary | 11 (21.2) |

| Higher Secondary and above | 12 (23.1) |

| Occupation | |

| Employed | 29 (55.8) |

| Unemployed | 7 (13.5) |

| Homemakers | 10 (19.2) |

| Students | 3 (5.7) |

| Retirees | 3 (5.7) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Class I (Upper) | 1 (1.9) |

| Class II (Upper middle) | 6 (11.5) |

| Class III (Middle) | 16 (30.8) |

| Class IV (Lower middle) | 23 (44.2) |

| Class V (Lower) | 6 (11.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 36 (69.2) |

| Unmarried | 14 (26.9) |

| Widowed | 2 (3.8) |

| Addiction history | |

| Yes | 33 (64.0) |

| No | 19 (36.0) |

| Status of health insurance | |

| Absent | 5 (10.0) |

| Present | 47 (90.0) |

| Follow-up periods (following discharge from Level-I Trauma Care Centre) | Percentile scores of each domain under WHODAS 2.0 | |||||

| Domain I (Cognition) |

Domain II (Mobility) | Domain III (Self-care) | Domain IV (Getting along) | Domain V (Life activities) | Domain VI (Participation) | |

|

1st follow-up (1 month after discharge) |

19.5 | 22.8 | 15.8 | 21.3 | 29.3 | 25.3 |

|

2nd follow-up (3 months after discharge) |

22.5 | 24.5 | 15.8 | 25.3 | 30.4 | 27.3 |

|

3rd follow-up (6 months after discharge) |

21.3 | 23.8 | 15.8 | 26.3 | 29.3 | 27.3 |

| PTSD |

1st Follow-up (1 month after discharge) |

2nd follow-up (3 months after discharge) |

3rd follow-up (6 months after discharge) |

| Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | |

| Present | 45 (86.5) | 49 (94.2) | 31 (59.6) |

| Absent | 7 (13.5) | 3 (5.8) | 21 (40.4) |

| Total | 52 (100.0) | 52 (100.0) | 52 (100.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).