1. Introduction

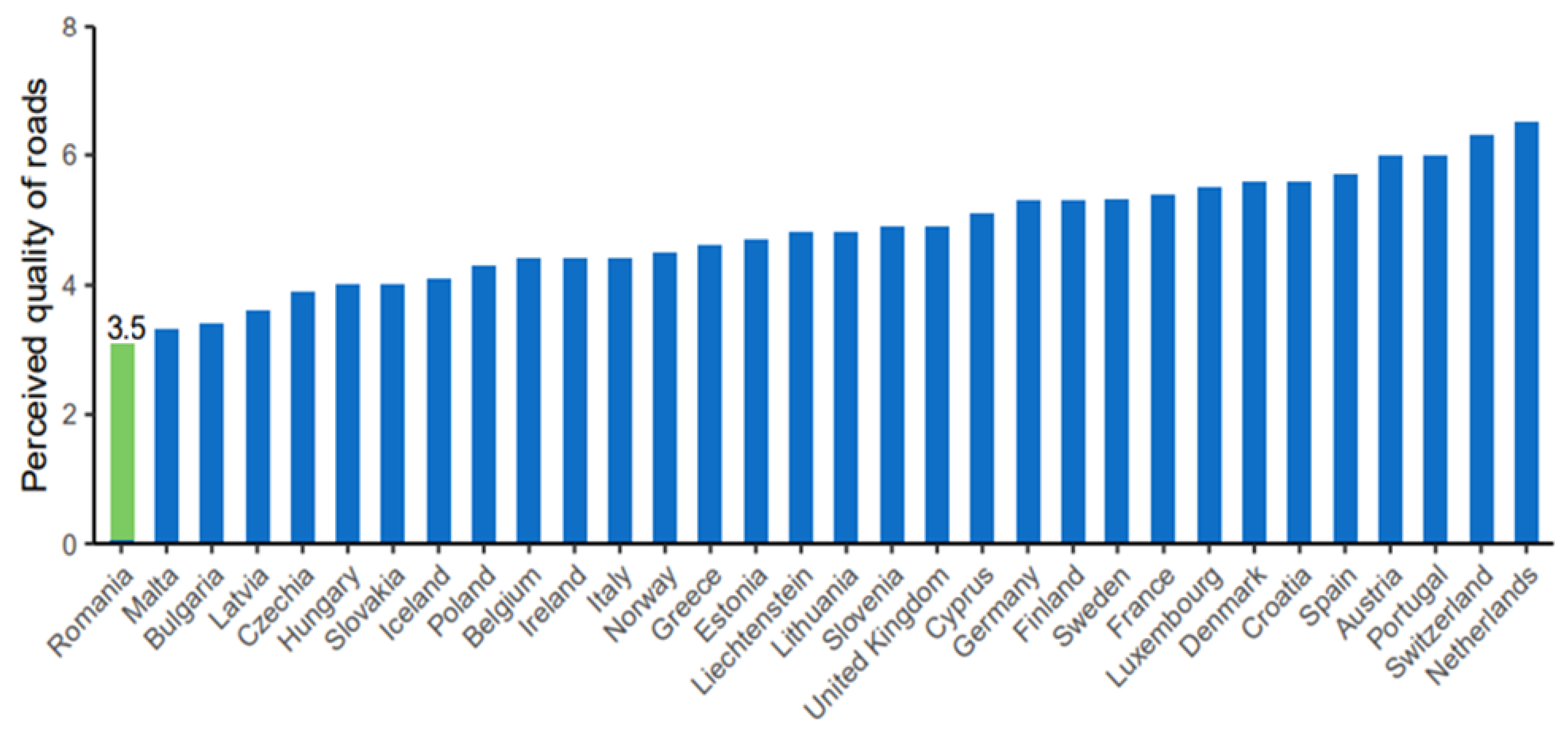

One of the leading causes, as indicated, is the average perceived quality of road infrastructure in the EU, which is above 4 on a scale of 1 to 7 (where 1 represents extremely poor and 7 represents among the best in the world). In Romania, it is around 3.5, the lowest in the entire Europe [

1] (

Figure 1).

Road traffic accidents (RTAs) are regarded as integral components of “development diseases” often stemming from the rise in motor vehicle numbers, population densities, and environmental alterations [

2]. Despite their significance, RTAs constitute a major yet frequently overlooked public health issue, entailing elevated rates of both mortality and morbidity on a global scale [

3]. They constitute a pervasive global challenge, impacting health, social well-being, and economic spheres, resulting in an annual toll of up to 50 million injuries [

4]. By 2025, road traffic injuries are expected to take third place in the rank order of disease burden [

5].

The term ‘accident,’ as defined in 1956, implies an unavoidable and unpredictable situation, a happening that cannot be averted. In contrast, the 2004 WHO report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention favors the use of the term “crash” [

6].

In the United States, the overall pediatric trauma survival rate varies between 80% and 95% [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], and statistics from the Netherlands indicate that for every child killed in a road traffic accident (RTA), another 42 are seriously injured [

12]. Based on the information from the Romanian Police National Statistics Center, there has been an average of 342 traffic accidents involving pediatric patients over the past 10 years. [

13]

Nonfatal injuries, even those considered minor, can result in significant short and long-term physical and psychological outcomes that are linked to substantial losses for individuals in all aspects of life, including their quality of life. Such injuries constitute a major cause of temporary or permanent disability and exert a notable negative impact on families and community networks [

7,

8,

9,

10,

14,

15].

Children, especially, are a vulnerable group in the context of road traffic. Younger children, in particular, face an increased risk of being run over by a vehicle. Despite having the necessary motor skills to walk on streets, they lack cognitive, sensory, and behavioral perception skills to comprehend traffic and associated risks [

16,

17]. Being run over by a vehicle is the leading cause of death and disability for children in numerous countries [

18], and the resulting injuries often tend to be more severe than those suffered when inside motor vehicles [

19].

Furthermore, children experience different types of injuries compared to adults. This is attributed to their lower mass, resulting in reduced kinetic force and lower-intensity accidents. Additionally, children often sit in the rear seats of vehicles, providing them with more protection. As a result, injury patterns differ between children and adults. Children tend to have fewer thoracic, intra-abdominal, pelvic, and long bone injuries, and they typically exhibit a lower Injury Severity Score (ISS) despite a higher Glasgow Coma Scale score [

17,

20]. These results may be explained by a better adaptive process and greater physiological plasticity, leading to a more effective response to trauma in children. This adaptability allows children to recover more successfully without permanent sequelae [

21]. However, in cases where sequelae do occur, conducting a Personal Injury Assessment (PIA) for children becomes challenging. It involves clarifying concerns related to permanent disabilities and future needs, which are difficult to predict for the child’s lifetime.

To our knowledge, there are no published medico-legal recommendations for PIA in children’s cases. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop medico-legal research on these cases to provide medical experts with scientific evidence.

The primary aim of this study was to examine the epidemiology of RTAs in children [

22]. More specifically, the study sought to analyze the mechanisms of injury (pedestrian, bicycle, and vehicle passenger) in relation to age, accompanying injuries, multiple fractures, injury patterns, and the interplay between these factors. Secondary objectives included identifying and characterizing specific aspects of children’s post-traumatic damage, with a focus on a) associated injuries and b) complications

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, we took a close look back at the years from 2015 to 2022, gathering information from the Emergency Department (ED) at “St. Mary’s” Emergency Clinical Hospital for Children and the Pediatric Orthopedics Department. Approval for the study protocol was obtained from the administration of the “St. Mary’s” Clinical Emergency Hospital for Children under the designated approval number 23177 dated July 10, 2020.

“St. Mary’s” ED is the go-to hospital for children dealing with injuries in Iaşi County and its surroundings, covering both city and country areas. Information from the hospital’s computerized medical records was extracted to identify patients admitted to the ED for TAs. Our emphasis was primarily on patients with cause codes V00–V99. We even did a digital scan using keywords like “road traffic accidents” and “traffic accidents”. This verification was carried out by meticulously scrutinizing their medical data.

The hospital’s ED functions as the main public facility for referring pediatric injuries, offering highly specialized medical treatment for the city and territory of Iaşi, as well as its surroundings, encompassing both rural and urban regions. Information from the hospital’s computerized medical records was extracted to identify patients admitted to the ED for TAs. Our emphasis was primarily on patients with cause codes V00–V99. Furthermore, an electronic search by the keywords “road traffic accidents” and “traffic accidents” was conducted to uncover any potential occurrences of traffic accidents that may have been missed during the classification procedure, which relied on provided cause codes. This verification was carried out by meticulously scrutinizing their medical data.

A total of 358 cases of RTAs were identified for the study. Data collection involved obtaining information on demographics, detailed data on the types of injuries sustained, and the treatment interventions provided. The anatomical region affected was correlated with the different accident types, and the characteristics of the harm inflicted determined the classification of injury types.

To conduct the statistical analyses, participants were categorized into specific age groups, including early childhood, spanned from 0 to 6 years, pre-adolescence ranged from 7 to 14 years, and adolescence extended from 15 to 18 years.

A database was established for the research, ensuring that no information was included to enable the identification of individuals involved. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were employed to characterize the entire study population, both overall and when stratified by age and gender. The chi-square test was utilized to examine the relationship between frequency variables. Assuming normal distribution, continuous variables were subjected to Student’s t-test for assessing differences between them. Throughout all analyses, a P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

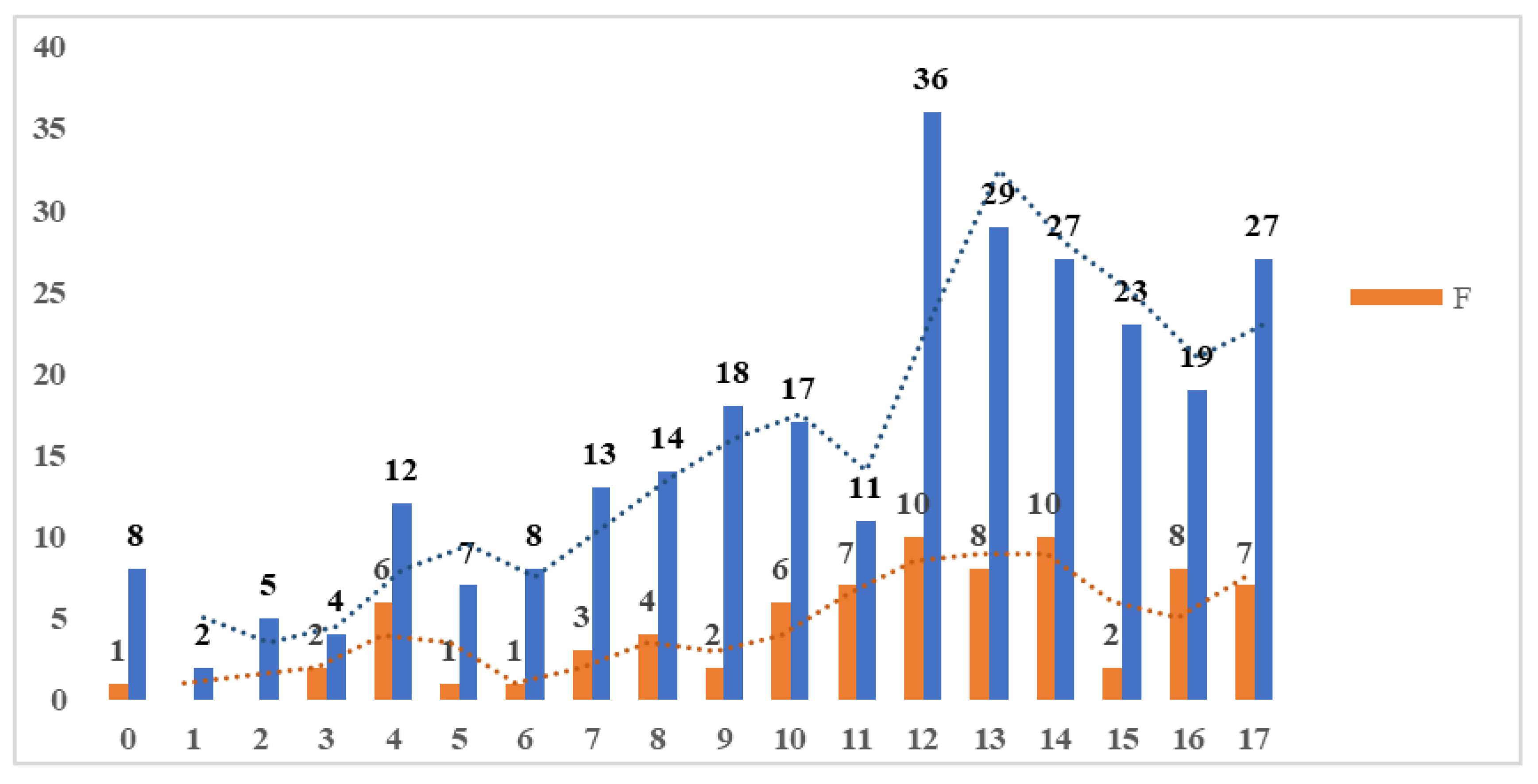

The gathered data indicates a total of 358 RTAs occurring across a range of ages, with the youngest case being 1 month old and the oldest 17 years old. The average age of the patients in the sample was 11.4 years, and these values deviate from the average by plus or minus 4 years.

Analyzing the data on patients age and gender, we note a distinct upward trend in the histogram for male patients, peaking around the age of 12 and then gradually declining until the age of 17. Conversely, in the case of female patients, there is a plateau between 0 and 10 years, succeeded by a rising trend with a spike at the age of 11, followed by a slight decline until the age of 17 (

Figure 2).

In the dataset, 271 patients were identified (constituting 76.1%) predominantly from rural areas, whereas only 23.9% originated from urban environments.

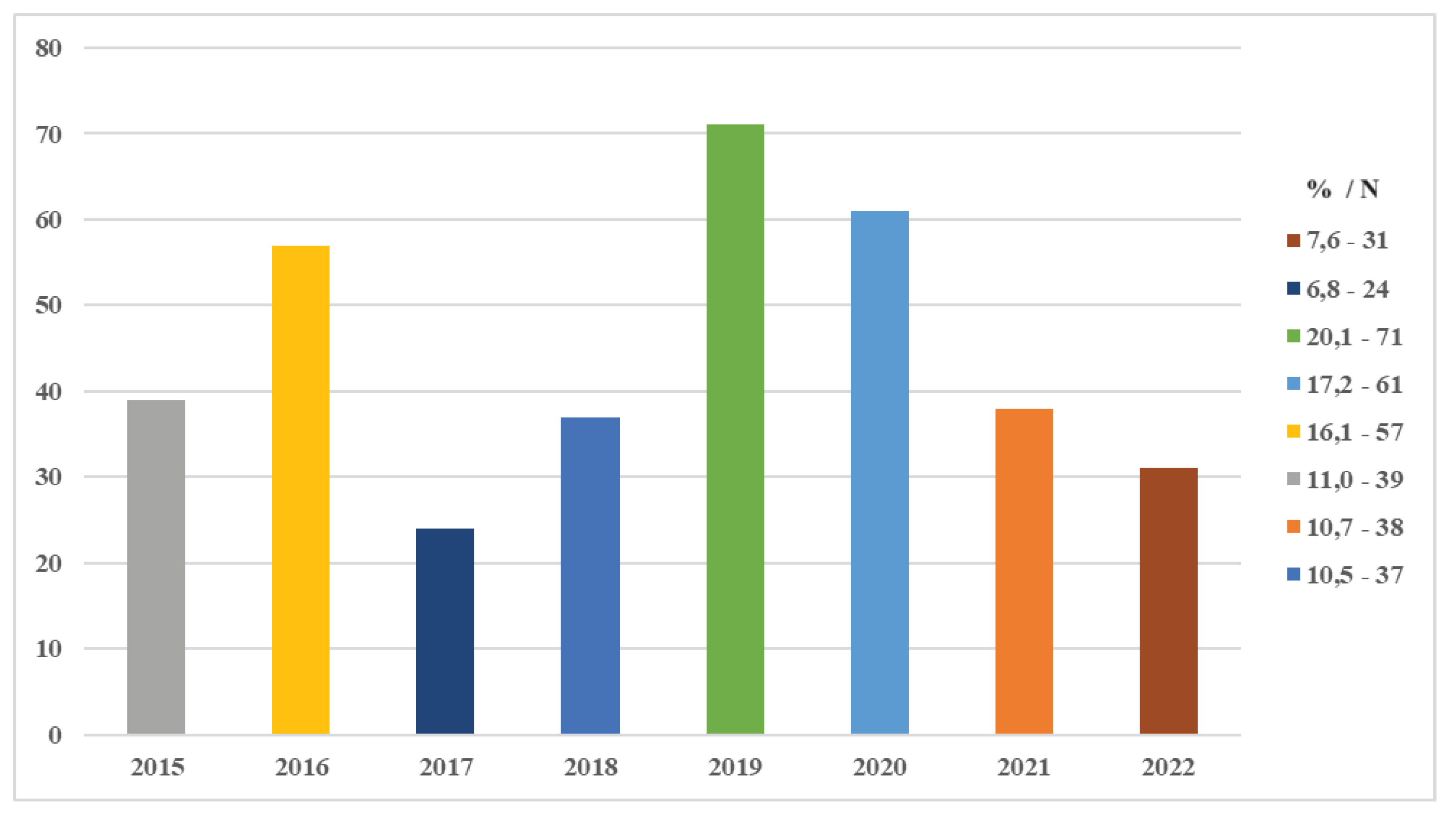

With a focus on the period from 2015 to 2022, we observed an oscillating trend between 2015 and 2020, reaching its lowest value in 2017 at around 6.8% (24 out of 358 cases) and its maximum value in 2019, reaching 20.1% (71 out of 358 cases). It is also noted that post-pandemic (Covid-19), the cases experienced a significant drop to approximately 50% of the previous years and maintained a downward trend until 2022 (

Figure 3).

Throughout the study period, seasonal variation marked a peak frequency of cases in June, accounting for 15.3% (55 out of 358 cases), corresponding to the beginning of summer vacation. Following this, September showed a rate of 10% (26 out of 358 cases), coinciding with the start of the school year. In contrast, the lowest number of cases was recorded during the winter month of January, with a rate of 1.7% (6 out of 358 cases).

Regarding pathological personal histories, it was found that 85.4% of patients (equivalent to 306 out of 358) had no prior pathologies before their presentation. The remaining 14.6% (equivalent to 52 out of 358) exhibited diverse antecedents, including allergies and conditions related to the heart, gastrointestinal, nutrition, neurology, as well as orthopedic issues (

Table 1).

Further analyzing the data, it was evident that the age group of 7–14 years exhibits dominance across various aspects. When correlated with gender, approximately 60% of the total patients fall within the preadolescent category, with males constituting a dominant 46% and females representing a predominant 14%. In examining the nature of road accidents among the overall patient population, it was observed that 26.81% belonged to the pedestrian category in the 7–14 age group, followed by cyclist patients at 15.64%, both falling into the preadolescent range. Additionally, there was a notable percentage of 8.37% for passengers in cars within the preadolescent age group. In contrast to the aforementioned categories concerning other injuries resulting from road accidents, it was noticed that they were predominantly in the adolescent category, accounting for 11.2% (

Table 2).

Data from the observation sheets, it was observed that the most impacted segment was the forearm, accounting for 99 out of 358 cases (28%). Conversely, the face and hand were the least affected, collectively making up less than 1% of the cases. The remaining segments ranged from 1.4% to 24.9% as seen in

Table 3.

Roughly 45.5% of the cases were reported as surgical cases, with 59.8% of these procedures performed as emergency operations, 38.5% conducted within a two-day timeframe, and a minimal percentage (1.7%) occurring after a two-week period. For those who did not undergo surgery, there remained a need for orthopedic reduction and immobilization, accounting for a substantial proportion, precisely 61.6%. At least 78.7% of those who did not undergo orthopedic reduction required surgery, whereas among those who underwent orthopedic reduction, only 23.4% needed surgery. With p < 0.05, it is acknowledged that there is a significant association between orthopedic reduction and the necessity for surgery (χ2=103.54; df=1; p < 0.001) (

Table 4).

No associated traumatic injuries were identified in 20.7% of the examined cases. The most prevalent such injuries were fractures (injuries categorized as fractures distinct from the primary fracture diagnosis) and abrasions, constituting 15% of the total cases in the study. This was followed by minor head injuries and contusion injuries to the thoraco-abdominal region, accounting for 10% and 7.26% of cases, respectively (

Table 5).

From the examined cases, 49.5% fell within the preadolescent age group. The most prevalent injuries in this category were fractures (distinct from the primary diagnosis of fracture) and abrasions, representing 15% of the total cases under study. Following these, minor head injuries and contusion injuries to the thoraco-abdominal region accounted for 10% and 7.26% of cases, respectively.

Regarding the frequency of complications, 28 out of the total 358 cases (7.9%) experienced complications. Among these, 32.1% had dehiscence of the postoperative wound. Occurrences of nerve contusion/paralysis, keloid scarring, and behavioral disorders were relatively rare, ranging from 3.5% to 14.2%. In relation to osteo-articular injuries, post-traumatic shortening and ankle valgus represented a combined total of 14.2% (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

In alignment with the demographic assessment conducted at the national level in Romania, during the year 2020, over half of the total newborns, specifically 51.6%, were male, indicating a sex ratio of 107 boys per 100 girls [

23]. While a national-level gender difference may not be pronounced, a substantial shift is observed in the context of traffic accidents. Analysis of the correlated sample data reveals that males account for 78%, whereas females represent 22% of the cohort, underscoring a significant gender disparity in this particular domain [

24,

25].

The increased frequency of pediatric traffic accidents may be linked to the comprehensive healthcare services provided by “St. Mary’s” Emergency Hospital for Children in Iasi. Serving as the regional hospital, it caters to a substantial patient population from both rural and urban areas across the seven counties of the Moldova region in Romania, unlike other studies that often restricted their scope to children aged 14 and under or from 12 to 24 years old, this study adopted more comprehensive inclusion criteria to encompass the higher incidence of reported incidents.

Our study benefits from an extensive data collection period spanning eight years (from 2015 to 2022) and a substantial sample size (examining 358 cases of childhood traffic accidents). Approximately 45.5% of these cases were reported as requiring surgical intervention, with 59.8% of these procedures performed as emergency operations. Within this subgroup, a significant proportion of individuals (at least 78.7% of those who did not undergo orthopedic reduction) required surgery, whereas among those who underwent orthopedic reduction, only 23.4% needed surgery. With a significance level of p < 0.05, our analysis acknowledges a significant association between orthopedic reduction and the necessity for surgery (χ2=103.54; df=1; p < 0.001).

It’s noteworthy that a notable portion of accidents, approximately 31%, transpired in children under the age of 14. However, a clear shift in the frequency and nature of accidents was observed after the age of 15. Seasonal variation was evident, with a peak frequency of cases occurring in June, representing 15.3% (55 out of 358 cases). This increase may be linked to the favorable weather conditions typical of Eastern Europe, characterized by a temperate-continental climate, which fosters pedestrian and cycling activities [

28,

29].

It is essential to emphasize that previous academic investigations have primarily focused on the fatal aspects of traffic accidents or solely on automobile collisions, thus distinguishing our study’s design in terms of its coverage and methodology.

Significant differences exist in long bone fractures, which account for 10%–25% of all pediatric traumatic injuries and primarily affect the upper limbs [

30,

31]; in our study, the predominant finding is that fractures of the long bones of the upper limb constitute 54% of the cases. Pediatric fractures differ from those in adults due to skeletal immaturity and bone physiology [

32]. Fortunately, children have advantages such as remodeling capacity and the ability to avoid long-term deformities [

31]. However, it’s essential to consider several prognostic factors, including the child’s age (with younger children more likely to experience significant deformity and dysmetria), the energy of the trauma, the type and severity of fractures (especially those affecting growth plates, which may impact future growth and development), skin integrity, and the degree of bone exposure, the presence of vascular or nerve branch lesions, the quality of fracture reduction (if applicable), and the type of treatment (conservative or surgical).

Growth disorders are frequently observed as a consequence of premature growth plate closure or rapid partial growth, resulting in shortening or deformity of the affected bone segment. In our study, a significant finding regarding the frequency of complications was noted. Out of the total 358 cases examined, 28 (7.9%) exhibited complications. Among these, osteo-articular injuries, such as post-traumatic shortening and ankle valgus, accounted for a combined total of 14.2% of patients with complications.

It has been observed that younger children tend to recover better after injury compared to older children [

33,

34,

35]. However, any disability acquired during childhood is always critical due to the potential losses, which depend on the developmental phase when the trauma occurs and have long-term implications throughout the remaining lifespan [

32].

Trauma during adolescence, the most prevalent age group in this study (59.6%), can hinder the acquisition of expected capabilities. It may lead to feelings of inferiority and inappropriate social behavior. Additionally, trauma can have extensive repercussions on different facets of life, such as school, social activities, and the personal and professional lives of parents. These consequences may include absenteeism, alterations in educational settings, reduced participation in extracurricular activities, and disruptions to parents’ schedules and careers [

36,

37,

38].

The findings of this study underscore the importance of implementing safety measures to protect children in their capacities as pedestrians, cyclists, or passengers in vehicles. Nonetheless, additional research is needed to identify the most effective preventive measures.

5. Conclusions

The present study revealed significant differences between preschool age, pre-adolescence, and adolescence, as follows:

a) Children exhibited a 51.6% higher likelihood of being involved in road traffic accidents.

b) In relation to associated injuries, about 49.5% were found in the preadolescent age group. Fractures were the most common type of injury, accounting for 15% of all cases in the study.

c) The average time between the road traffic accident and surgical intervention was two days, with only 27.3% of the cases undergoing emergency procedures.

d) Regarding the frequency of complications, similarities were observed between the pre-adolescent and adolescent groups.

This study highlights the necessity for further research in this area and the formulation of guidelines for pediatric injury assessment based on scientific evidence. For future initiatives, priority should be given to enhancing safety and enforcing traffic laws, implementing traffic control measures, improving road infrastructure, and encouraging children to participate in school education programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ș.P., D. B.-I., A. O.S., I.-L.C., and I.S.; methodology, Ș.P., D. B.-I., A. O.S., I.-L.C., and I.S.; validation, C.I.C., and I.P.P.; formal analysis, Ș.P., D. B.-I., A. O.S., I.-L.C., and I.S.; investigation, Ș.P., D. B.-I., A. O.S., I.-L.C., and I.S.; data curation, writing—original draft preparation.; writing—review and editing Ș.P., D. B.-I., A. O.S., I.-L.C., and I.S.; visualization, C.I.C., and I.P.P.; supervision, C.I.C., and I.P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of “St. Mary’s” Clinical Emergency Hospital for Children, Iasi (nr. 23177/10 June 2020), for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- https://road-safety.transport.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-02/erso-country-overview 2023-sweden_0.pdf.

- Söderlund N, Zwi AB. Traffic-related mortality in industrialized and less developed countries. Bull World Health Organ. 1995, 73, 175–182.

- Bakhtiyari M, Delpisheh A, Monfared AB et al. The road traffic crashes as a neglected public health concern; an observational study from Iranian population. Traffic Inj Prev 2014, 16, 36–41.

- World Health Organization, W. Global status report on road safety 2018. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. “The Global Burden of Disease”. Projected change in the ranking of the 15 leading causes of death and disease (DALYs) worldwide, 1990-2020. WHO.2020.

- Kumar, N.; Kumar, M. Medic olegal study of fatal road traffic accidents in Varanasi region. IJSR 2015, 4, 1492–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Doud AN, Schoell SL, Weaver AA, et al. Disability risk in pediatric motor vehicle crash occupants. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017; 82:933–938.

- Gaffley M, Weaver AA, Talton JW, et al. Age-based differences in the disability of extremity injuries in pediatric and adult occupants. Traffic Inj Prev. 2019;20:S63–S68.

- Schoell SL, Weaver AA, Talton JW, et al. Functional outcomes of motor vehicle crash head injuries in pediatric and adult occupants. Traffic Inj Prev. 2016;17:27–33.

- Zonfrillo MR, Durbin DR, Winston FK, et al. Physical disability after injury-related inpatient rehabilitation in children. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e206–e213.

- Janssens L, Gorter JW, Ketelaar M, et al. Long-term health condition in major pediatric trauma: a pilot study. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1591–1600. 1600.

- Twisk DAM, Bos NM, Weijermars WAM. Road injuries, health burden, but not fatalities make 12-to-17-year-olds a high-risk group in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2017; 27:981–984.

- Romanian Police National Statistics Center 2019. https://www.politiaromana.ro/ro/ structura-politiei-romane/unitati-centrale/directia-rutiera/statistici. 2019.

- Batailler P, Hours M, Maza M, et al. Health status recovery at one year in children injured in a road accident: a cohort study. Accid Anal Prev. 2014;71:267–272.

- Lystad RP, Bierbaum M, Curtis K, et al. Unwarranted clinical variation in the care of children and young people hospitalised for injury: a population-based cohort study. Injury. 2018;49:1781–1786. 1786.

- Olofsson E, Bunketorp O, Andersson AL. Children at risk of residual physical problems after public road traffic injuries—a 1-year follow-up study. Injury. 2012;43:84–90.

- Doong JL, Lai CH. Risk factors for child and adolescent occupants, bicyclists, and pedestrians in motorized vehicle collisions. Traffic Inj Prev. 2012;13:249–257.

- Eilert-Petersson E, Schelp L. An epidemiological study of non-fatal pedestrian injuries. Safety Science. 1998;29:125–141.

- Mitchell RJ, Bambach MR, Foster K, et al. Risk factors associated with the severity of injury outcome for pediatric road trauma. Injury. 2015;46:874–882.

- Cunha-Diniz F, Taveira-Gomes T, Teixeira JM, et al. Trauma outcomes in nonfatal road traffic accidents: a Portuguese medico-legal approach. Forensic Sci Res. 2022;7:528–539.

- Borobia C, Alías P, Pascual G. Avaliação do dano corporal em crianças e idosos [The assessment of bodily harm in children and elderly]. In: Vieira DN, Quintero JMA, editors. Aspectos práticos da avaliação do dano corporal em Direito Civil. [Practical aspects of personal injury assessment in Civil Law]. Coimbra, Portugal: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 2008, 131–146. Available from: https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-0400-8. Portuguese.

- Brockamp T, Schmucker U, Lefering R, et al. Comparison of transportation-related injury mechanisms and outcome of young road users and adult road users, a retrospective analysis on 24,373 patients derived from the Trauma Register DGU®. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2017;25:57.

- https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/evenimente_demografice_in_anul_2020.pdf.

- Kevill, K.; Wong, A.M.; Goldman, H.S.; Gershel, J.C. Is a complete trauma series indicated for all pediatric trauma victims? Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2002, 18, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, S.; Ciongradi, C.I.; Sârbu, I.; Bîca, O.; Popa, I.P.; Bulgaru-Iliescu, D. Traffic Accidents in Children and Adolescents: A Complex Orthopedic and Medico-Legal Approach. Children 2023, 10, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Road Safety Observatory: Facts and Figures—Children, 2022. Available online:https://roadsafety.transport.ec.europa.eu/system/files/202208/ff_children_20220706.pdf.

- Pearson, J.; Stone, D.H. Pattern of injury mortality by age-group in children aged 0–14 years in Scotland, 20 02–20 06, and its implications for prevention. BMC Pediatr. 2009, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paffrath T, Lefering R, Flohe S, et al.How to define severely injured patients?—An Injury Severity Score (ISS) based approach alone is not sufficient. Injury. 2014;45:S64–S69.

- Palmer CS, Gabbe BJ, Cameron PA. Defining major trauma using the 2008 Abbreviated Injury Scale. Injury. 2016;47:109–115.

- Christoffersen T, Emaus N, Dennison E, et al. The association between childhood fractures and adolescence bone outcomes: a population-based study, the Tromsø Study, Fit Futures. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29:441–450.

- Holton CS, Kelley SP. The response of children to trauma. Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:337–349.

- Gaffley M, Weaver AA, Talton JW, et al. Age-based differences in the disability of extremity injuries in pediatric and adult occupants. Traffic Inj Prev. 2019;20:S63–S68.

- Batailler P, Hours M,Maza M, et al. Health status recovery at one year in children injured in a road accident: a cohort study. Accid Anal Prev. 2014;71:267–272.

- Olofsson E, Bunketorp O, Andersson AL. Children at risk of residual physical problems after public road traffic injuries—a 1-year follow-up study. Injury. 2012;43:84–90.

- Bohman K, Stigson H, Krafft M. Long-term medical consequences for child occupants 0 to 12 years injured in car crashes. Traffic Inj Prev. 2014;15:370–378.

- Figueiredo C, Coelho J, Pedrosa D, et al. Dental evaluation specificity in orofacial damage assessment: a serial case study. J Forensic Leg Med. 2019;68:101861.

- Wright, T. Too scared to learn: teaching young children who have experienced trauma. Young Child 2014, 69, 88. [Google Scholar]

- de Haan A, Tutus D, Goldbeck L, et al. Do dysfunctional posttraumatic cognitions play a mediating role in trauma adjustment? Findings from interpersonal and accidental trauma samples of children and adolescents. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019;10:1596508.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).