1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, road traffic accidents (RTAs) are the leading cause of death for children and young adults aged 5-29 years worldwide [

1]. Every 24 seconds, one person is killed in a road accident, which is 1.35 million deaths per day. Globally, more than 500 children under the age of 18 die on the road each day [

2]. More than 90% of the world’s road traffic fatalities occur in low- and middle-income countries [

1]. India continues to top road accidents fatalities globally, with a 4.2% increase in crashes, and a 2.6% increase in fatalities in 2023 when compared with the road accidents data of the previous year [

3]. Unsafe driving, including speeding, driving under the influence, non-use of motorcycle helmets and seatbelts, and distracted driving are common causes of RTA. In addition to human behaviors, unsafe road infrastructure, unsafe vehicles, inadequate law enforcement of traffic laws, etc. play a critical role in road traffic injuries [

1].

RTAs often result in dreadful consequences where members of a whole family including RTA survivors, their parents, friends, and other caregivers often suffer adverse social, physical, and psychological effects [

4,

5]. Longitudinal studies on RTA victims have revealed that psychological factors, including emotional and cognitive perceptions, are negatively associated with functional outcomes more commonly following head injury and lower extremity trauma [

6,

7]. Studies have also shown that involvement in RTA may put individuals at increased risk for long-term psychosocial disorders, including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety. Particularly, PTSD is now a significant public health concern among RTA survivors. PTSD is characterized by re-experiencing the traumatic event in the form of vivid dreams, disturbing memories, flashbacks, or nightmares, which are accompanied by strong or overwhelming emotions, particularly fear or horror, and intense physical sensations [

8,

9]. The physical and psychological effects of RTAs can impact a person’s work capacity, financial stability, and social productivity [

10]. Additionally, involvement in injury compensation claims processes is associated with poorer post-injury physical and psychological health [

11]. RTA-related hospital expenses, loss of income, and loss of work could create a major financial burden for trauma victims and the affected families [

11,

12].

This study aimed to address the magnitude of disability, PTSD, and social-, and economic complications among RTA victims within 6 months of post-discharge from a trauma care center of a tertiary care hospital in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. The overarching goal of this project was to suggest comprehensive management and preventive measures for RTAs based on the data generated from the study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This longitudinal study was conducted from July 2022 to June 2024. Phase I of the study was carried out at the Level I Trauma Care Center of the Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research (IPGME&R) and

Seth Sukhlal Karnani Memorial (

SSKM) Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal. Adults aged 18 years or older and either gender were eligible for enrollment. The hospitalized RTA-victim patients who had Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) [

13] of 9 or more after 48 hours of admission were enrolled after taking written informed consent. RTA patients with GCS ≤ 8, and those who did not give informed written consent for participating in the study were excluded.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of IPGME&R and SSKM Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal (Memo No. IPGME&R/IEC/2022/462, dated 07/11/2022). The eligible RTA victims were admitted to the Level I Trauma Care Center of the hospital. Patients (or their legal guardians/close relatives) were explained the purpose of the study. A written informed consent was taken from the patient or guardian/close relatives of a severely injured study participant before enrollment of the patient to the study.

2.3. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

The major outcome variable for the sample size estimation was PTSD after RTA. The sample size (n) was calculated using the Cochran’s formula as follows:

Here, Z = 1.96, with Type-1 error as 5% or 0.05; p (post-discharge PTSD at 6 months) = 50% q = (1- p), d = Absolute precision (15%).

The sample size obtained was 43. After considering a 20% loss to follow-up, the final sample size was calculated to be 52.

2.4. Data Collection Instruments and Methods

Data collection instruments (questionnaires) are presented in Appendix I. Data included three components:

- A.

Socio-demographic data – Data were collected at the time of enrollment. The variables included age, gender, religion, occupation, residence, education, income, etc.

- B.

Details of RTA, type of injury, and clinical data – Data were collected during the hospital stay of the victim. According to the type of accident, RTAs were divided into motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), non-MVAs, pedestrian accidents, and passenger accidents. MVAs include car accidents, motorcycle accidents, tram accidents, tractor accidents, special mechanical accidents, etc. Non-MVAs consisted of rickshaw accidents, bicycle accidents, etc. Pedestrian and/or passenger accidents refer to accidents in which pedestrians and/or passengers were primarily responsible.

- C.

Follow-up data: Four types of data instruments were vital for the outcome measurements of this study. They included 1)

Disability Assessment by using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) [

14]; 2)

PTSD Checklist for DSM 5 (PCL-5) [

15,

16]; 3)

Social Impact Data; and 4)

Economic Impact Data to assess the socioeconomic impact of RTA.

WHODAS 2.0 Scale

WHODAS 2.0 [

14] is a 36-item measure that measures disability in patients aged 18 years and older. It assesses disability across

six domains, including understanding and communicating, getting around, self-care, getting along with people, life activities (i.e., household, work, and/or school activities), and participation in society. Each item of the WHODAS 2.0 involves the individual to rate how much difficulty he/she has had in specific areas of functioning during the past 30 days. The scores assigned to each of the items were “none” (0), “mild” (1), “moderate” (2), “severe” (3), and “extreme” (4). The summary score is the combined value. The higher the score, the greater the disability.

The summary score is converted into a scale ranging from 0 to 100 (where 0 = no disability; 100 = full disability). A percentile is calculated that allows for a comparison to a large sample. Percentiles indicate the percentage of scores that fall below a particular value. A percentile of 50 (median score) in this scale indicates that a study subject is experiencing an ‘average’ level of disability when compared to other members of the sample. Based on this information, in this study, the level or severity of disability was categorized as ‘very low’ for scores ≤ 25th percentile, ‘low’ for scores between the 26-49th percentile, 50th percentile as ‘moderate’ (average disability), 50-75th as ‘high’ and ≥ 75th percentile score as ‘very high’ level of disability.

PCL-5 checklist (for PTSD)

The PCL-5 checklist is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses 20 DSM-5 symptoms of PTSD [

15,

16]. This self-reporting scale is 0-4 for each symptom. Rating scale descriptors are:

"not at all," "a little bit," moderately," "quite a bit," and "extremely”. In this study, we used total scoring criteria by adding individual item scores. The cut-off point was 33 for making a provisional diagnosis of PTSD. Thus, a total score ≥ 33 is considered as ‘PTSD

present’ and a score ≤ 32 as ‘PTSD

absent’.

Assessment of the socioeconomic impact of RTA

This questionnaire included separate assessments for social and economic impacts.

- 1)

Social Impact Data – The questions were as follows: Was the victim being neglected by family/friends/neighbors/other acquaintances following RTA?; Was the victim made fun of/insulted by others following the RTA? Did the victim receive any rehabilitative services?

- 2)

Economic Impact Data – There were 8 questions related to absence from a job, reduced workload, change of job, wage loss, and out-of-pocket expenses. Each item under the socioeconomic impact domain was given a score of ‘1’ for a ‘yes or positive’ response, and ‘0’ for a no or negative response

2.5. The Study Protocol

The study was carried out in four phases:

Phase I: Data were collected by face-to-face interviews of the eligible study participants admitted at the Level I Trauma Care Centre. Data collection was conducted on two randomly selected days in a week (Tuesday and Saturday) for 5 consecutive weeks, and for three randomly selected days on the 6th subsequent week (Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday). 4 RTA victims, who fulfilled the selection criteria, were interviewed consecutively on each day of data collection for 6 weeks to achieve the desired sample size of 52.

Phase II (1-month post-discharge): The 1st follow-up visits after 1 month of post-discharge were scheduled for each study participant at the Outpatient Departments (OPDs) of Orthopedics, General Surgery, Neuromedicine, and Neurosurgery from 9:30 A.M.- 2 P.M. If any participant did not show up on the scheduled day of follow-up visit at the OPD, he/she was contacted by telephone and advised to come the next day. If the next day happened to be a Sunday (weekend), the participant was advised to attend the respective OPDs on Monday or any day of the following week.

Phase III (3 months post-discharge): This phase (2nd follow-up) of the study was carried out after a period of 3 months of discharge of the victim from the Trauma Centre. Data collection was undertaken by telephonic interview using the WHODAS 2.0 and PCL-5 scales. In addition, the socioeconomic impact of RTA on each participant was also assessed in this phase.

Phase IV (6 months post-discharge): The final phase (3rd follow-up) of the study was carried out after a period of 6 months from the discharge of the victim from the Trauma Care Centre. Data were collected again through telephonic interviews using the WHODAS 2.0 and PCL-5 scales. The socioeconomic impact of RTA was also assessed during this visit.

2.6. Statistical Methods

Data were tabulated in Microsoft Office Excel 2021 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) and analyses were done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, IBM SPSS (Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. 2017). Descriptive statistics such as Mean (± SD), frequency, and percentage were calculated as applicable. The association between categories of disability status, PTSD, and socioeconomic impact (high or low) during each follow-up period was assessed with the sociodemographic profile using the Chi-Square Test. Spearman’s Correlation was used to find out the correlation between the disability scores during the 1st and 3rd follow-up, between the PTSD scores during the 1st and 3rd follow-up, and between the socioeconomic impact scores during the 1st and 3rd follow-up periods. Friedman ANOVA Test was employed to check any significant mean differences of scores (by assigning ‘ranks’) between the disability severity, PTSD, and socioeconomic impact scores during the 1st, 2nd,, and 3rd follow-up periods. These groups were categorized pairwise and the differences in scores between the matched pairs of follow-up periods were assessed using the Wilcoxon Matched-Pairs Signed Rank Test. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Status

Table 1 shows that the mean ± SD age of the study participants was 31.3 ± 12.9; almost half (51.9%) of the study participants belonged to the age group of 21-30 years and 76.9% of them were males. Around 23% of participants received middle school and higher secondary school education and above. 55.8% of study participants were employed. Almost 44% belonged to the lower-middle (Class IV) socioeconomic class. 27% of participants were unmarried while 4% were divorced. 5 (10%) of the study participants did not have any health insurance scheme. 90% of them had health insurance. None of the study participants were under the influence of any addictive substance at the time of sustaining an RTA

.

3.2. Type of Injuries

Most of the participants suffered an RTA during the night (38%); 46% sustained an RTA in lanes, and 17% on highways. Getting hit by another vehicle was the most reported mechanism of injury caused by an RTA. Environmental factors causing RTAs included stormy weather and heavy rainfall at the time of RTA. 81% of the participants suffered a fracture following an RTA. 96% of participants who rode a two-wheeler at the time of RTA did not use helmets, while only 1 (8.3%) reportedly used seatbelts while driving a four-wheeler. 44.2% had a GCS score of 15 at the time of admission at the Level I Trauma Care Center. Among the participants who sustained fracture(s), the most reported were comminuted fractures (45.2%). 33% had reported a history of a head injury following RTA, among which the most reported was a cerebral concussion (23.5%), followed by acute Extra Dural Hemorrhage (EDH) (17.6%) and coup-contrecoup hemorrhagic contusions in right basal, frontal and temporoparietal lobes, with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in the left parietal lobe (17.6%). Two study subjects suffered blunt trauma in the abdomen following RTA.

3.3. Disability Status

Table 2 shows that the percentile scores of the disability status in all three follow-up periods were below the 25

th percentile (Domain I, II, and III) indicating a ‘very low’ level of disability, except in Domains IV, V, and VI, where the percentile scores were between 26-50

th percentile, indicating a ‘low’ level of disability. The percentile scores (

Table 2) showed a gradual increase from 1

st to 2

nd follow-up with a decline in the 3

rd follow-up period, in Domains I, II, and V. However, Domain IV (Getting along) showed a progressive increase in the level of disability with each follow-up period.

3.4. PTSD

Table 3 demonstrates that the presence of PTSD showed an increase during the 2

nd follow-up, followed by a decline during the 3

rd follow-up. While among those who reportedly did not have PTSD, the proportion showed a decline during the 2

nd follow-up from the 1

st, however, it increased during the 3

rd follow-up.

Among the type of injuries, head injury was significantly associated with PTSD severity during the 1st (p= 0.01) and 3rd follow-up periods (p= 0.007). Sustainment of fractures had statistically significant associations with severity of disability, PTSD, and socioeconomic impact during all three follow-up periods (data not shown).

3.4. Social Impact

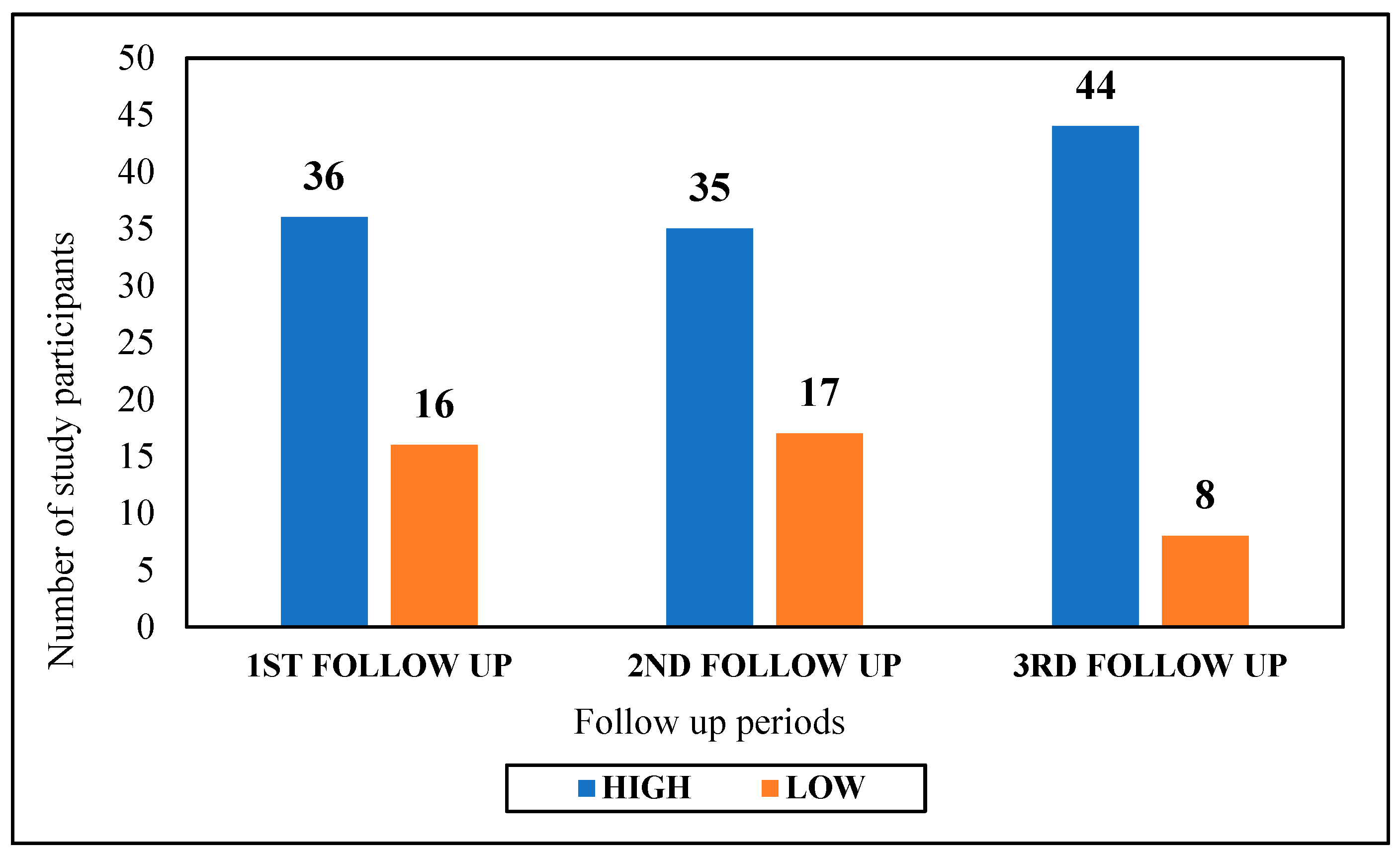

Social impact (

Figure 1) following RTA was ‘high’ among most (84.6%) of the study participants during the 3

rd follow-up, while social impact was ‘low’ among most of the participants (32.7%) during the 2

nd follow-up.

3.5. Economic Impact

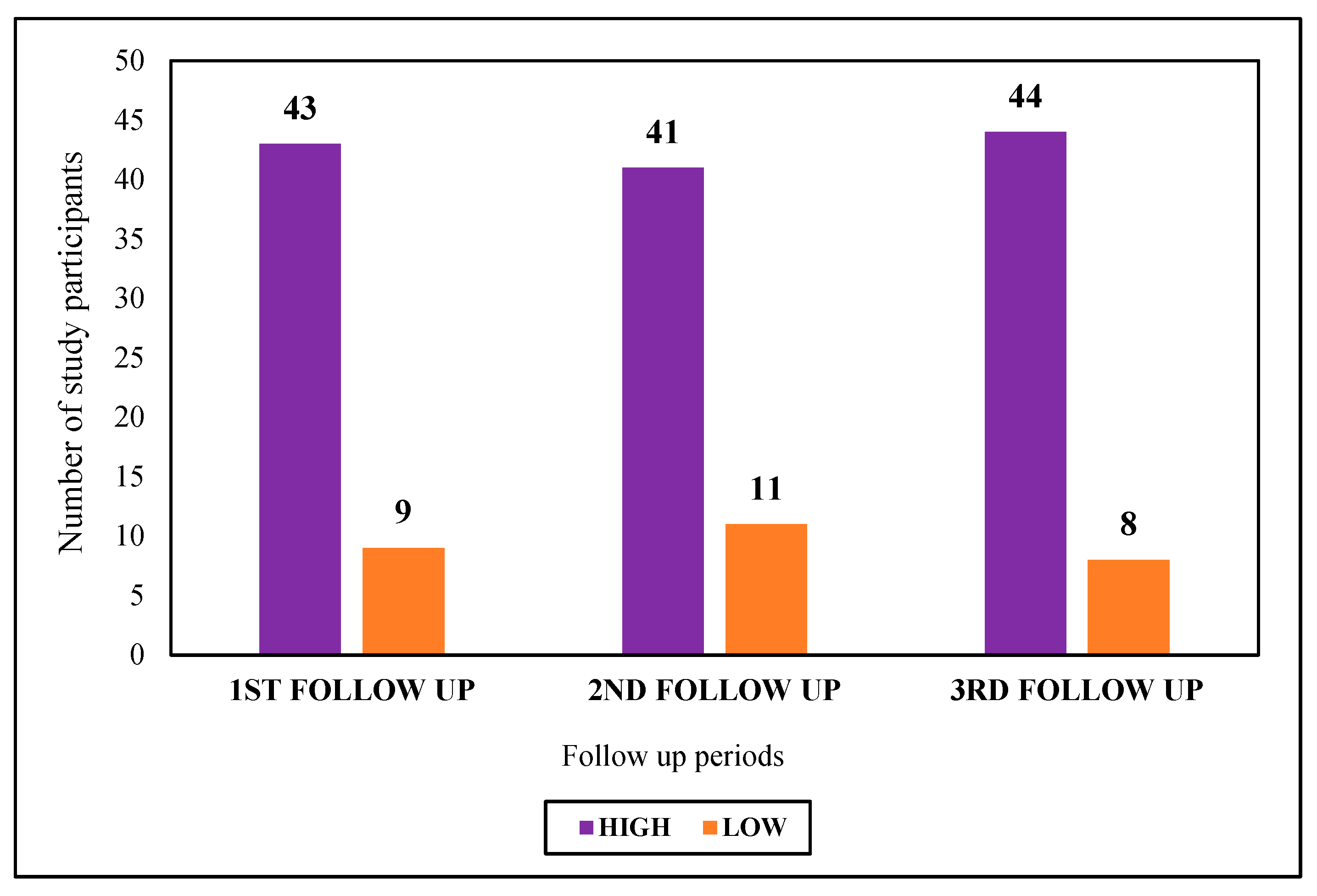

Economic impact (

Figure 2) was ‘high’ among most (84.6%) of the study participants during the 3

rd follow-up, while it was ‘low’ among most of the participants (21.1%) during the 2

nd follow-up.

4. Discussion

This study showed that the level of disability among the RTA victims was from very low to low with a progressive improvement in each of the three follow-up periods in 6 months post-discharge. Whereas the percentage of victims suffering from PTSD was very high – with 87% during the 1st follow-up visit, 94% during the 2nd follow-up visit, and 60% during the 3rd visit. Both the social impact and economic impact due to RTA were high, around 85% during the 3rd visit.

4.1. Disability

In a cross-sectional study of 563 victims of RTA in Turkey, the rate of disability was determined in 295 cases [

17]. Most disabilities were recorded in teenagers and adults between 15 to 50 years of age. Injuries of the pelvis and lower extremities resulted in the majority of disabilities (n = 217, 73.6%), followed by head injuries (n = 35, 11.9%), whereas our study showed most disabilities among head injury patients. In another study, Bull (1985) [

18] reviewed disabilities incurred by 2502 road accidents in the United Kingdom. There was an equal number of disabled among pedestrians, motorcyclists, and vehicle occupants, while motorcyclists had the highest number of RTAs and disabilities in our study subjects. In the UK study, like the Turkish study, the most serious disabilities were caused by head injuries and lower limb injuries. In a population-based study of 91,846 households with 20,425 disabled persons older than 15 years [

19], 443 had a disability due to RTA, yielding the prevalence rate of RTA-associated disability of 2.1 per 1000 inhabitants (95% CI: 1.8 to 2.3). The risk of disability was highest among persons aged 31 to 64 years. This rate of low prevalence of disability is similar to the low rates observed in our study subjects.

4.2. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

PTSD results from the traumatic experiences in many RTA victims [

20]. In a longitudinal study in Ethiopia, Fekadu et al (2019) [

20] showed that nearly half of RTA survivors develop PTSD, like our study where 87% of the RTA victims developed PTSD after one month of follow-up following hospital discharges, which peaked at the second follow-up at 3 months and then about 10% improved after 6 months post-discharge. In the Ethiopian study, 51.9% reported extreme problems in social functioning. Alcohol dependence, hazardous alcohol consumption, and harmful use of alcohol were reported by 7.9%, 15.1%, and 4.7% of the participants, respectively. In an earlier study in Germany [

21], Frommberger et al. reported that 18.4% of 179 RTA victims developed PTSD at 6-month follow-up. In a study in France [

22], among 592 subjects with RTA, the risk of PTSD was predicted by initial injury severity, post-traumatic amnesia, the feeling of not being responsible for the accident, and persistent pain.

4.3. Economic Impact of RTA

RTAs have profound economic impact as well in terms of loss of life and productivity, serious injuries and substantial mental trauma experienced by the victims and their families. A national report the estimated mean direct total cost of RTA burden in India in 2019 was 1,534 million Rupees (equivalent to US

$ 18 million) with a median (IQR) of 1,155 million (2,588 million) Rupees (US

$ 13 million (

$ 31 million) [

23].

However, the calculation of financial losses is often a complex process. Various quality-of-life scales are often used to measure the economic impact of RTA [

24]. In a study conducted by the European Transport Safety Council, persons with low socioeconomic status were found to suffer from more traffic injuries [

25]. In the current study, almost 30% of the RTA victims belonged to a low or lower middle socio-economic scale in India. A difference in the measurement scale of the economic loss also accounts for the societal differences in the observed economic impact. In our study, the economic impact of RTA was measured in terms of absenteeism from job following the accident, loss of wages, reduction in workplace performance, change of job, expenditure on treatment, and out-of-pocket expenditure. Whereas, the European study delineated medical cost, property damage and administrative cost as the cost of restitution and used the value of lost productive capacity as a human capital approach for the calculation of the economic loss [

25].

The economic burden due to RTA in developing countries is enormous when the overall economic status is taken into consideration. In our study, about half of the participants faced a financial crisis during the 3

rd follow-up. Among those who faced a financial crisis, most had to sell off valuable items like motorbikes, jewelry, shops, and agricultural lands to compensate the financial loss, which led to increased poverty. In another study in India [

26], about two-third of the RTA victims had to spend about 10 times of their monthly income whereas only 3.5% of victims had health insurance coverage in the country. Moreover, 64.0% of RTA victims had lost of their wages while staying in the hospital [

26]. Prinja et al. (2029) [

27] reported a high prevalence of catastrophic expenditure among 22.2% following RTA in India, of which about 12% fell below the poverty line after major incidents.

4.4. Social Impact of RTA

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration [

28], an estimated monetary value of the societal harm from motor vehicle crashes is nearly

$836 billion, which is roughly three and a half times the value measured by economic impacts of RTA alone. Of this total, 71 percent represented lost quality of life. In our study, the social impact was estimated based on parameters like social neglect, mockery, or availability of rehabilitation services, which can be considered as proxy indicators of social quality of life. Social impact, thus measured, was substantial (as high as 84.6%) among victims during the final follow-up visit following the accident.

Thus, not only economic losses but also the more intangible social factors are to be considered during the formulation of post-accident rehabilitative services.

4.5. Limitations

Although this is a longitudinal study, two follow-up visits were conducted by telephone interview, which could result in information bias. In addition to the quantitative analyses, a mixed method of study design using focus group discussion could potentially minimize recall biases over time. Moreover, a control group could have been used for a better understanding of sociodemographic factors related to health as compared to the RTA victims.

5. Conclusions

This longitudinal follow-up study was able to establish the impact of RTA on the physical health (disability), mental health (PTSD), and socioeconomic conditions of the victims over time. This was evident by the increase in the proportion of PTSD cases from the first visit to the subsequent follow-up visits, and a high impact on social and economic factors. Therefore, while managing the RTA victims, a more holistic long-term approach is needed in addition to immediate medical care. Social scientists and psychotherapists can effectively treat a wide range of mental health conditions of the victims to overcome their financial crisis, for social adjustment, and for rehabilitation.

In this study, most of the RTA victims were motorcyclists and the majority of them were not using helmets during the time of the event. Among the car accident victims, almost none used seatbelts. A stricter enforcement of laws, including large financial penalties for the violation, and an increased surveillance system ensuring road safety practices should be in place.

RTAs occurred more commonly on city roads and not on highways. The city planners should prioritize proper road design and construction for road safety, particularly on narrow roads, improve traffic control, and sufficiently display warning signs and safety messages in strategic locations. Also, extensive campaigns and media coverage on road safety measures are needed for public awareness. Peer group education, particularly with survivors, can be an inspiring method for creating awareness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SP, SD, SN, SS; Methodology, SP, SD; Software, SP; Formal Analysis, SP, AKM; Investigation, SP, SD; Resources, SD, MB; writing—original draft preparation, SP; writing—review & editing, AKM, SD; visualization, SP, A.K.M.; supervision, SD; project administration, SD. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of IPGME&R/SSKM Hospital (Memo number IPGME&R/IEC/2022/462, dated 07/11/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data collection questionnaires are provided in

Appendix A. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

PART I: Socio-demographic profile of the study participants

-

a)

Age (in completed years)-

-

b)

Gender: Male/ Female/ others (specify)-

-

c)

Residence- Urban/Rural

-

d)

Living with- Alone/ Family

-

e)

Religion- Hindu/Muslim/Christian/Others (specify)

-

f)

Marital status- Married/ unmarried/ others (specify)

-

g)

Highest level of education- Illiterate/ non-formal education/ primary/ middle school/ secondary/ higher secondary and above

-

h)

Occupation- Unemployed/ Employed (specify)-

-

i)

Total family income per month (in Rs.)-

-

j)

Number of family members-

-

k)

Socio-economic status (as per Modified B.G. Prasad Scale, 2022)-

-

l)

Health insurance- Present/Absent

If present, specify-

-

m)

Addiction history- Present/Absent

If present: alcohol/ smoking/ smokeless tobacco/ others (specify)-

-

n)

Whether under the influence of any abusive substance at the time of accident? – Yes/No

If yes, specify-

-

o)

Socio-cultural problems in family- Present/Absent

If present, specify-

PART II: Details of RTA and the clinical profile of admitted patients

-

a)

Date of accident-

-

b)

Place of accident- Street/ Highway/ Lane

-

c)

Time of accident-

-

d)

Date and Time of admission at the Level I Trauma Centre of IPGME&R-

-

e)

Any environmental factors leading to the RTA? – Yes/ No

If yes (multiple responses):

If yes- heavy rainfall/ storm/ foggy weather

If yes – engine failure/ brake failure/ tire puncture/ others (specify)

- f)

Mechanism of injury following accident (multiple responses):

- i)

Fall from vehicle- Yes/No

- ii)

Skidding while driving- Yes/No

- iii)

Getting hit by another vehicle- Yes/No

- g)

Type of injury following accident (multiple responses):

- i)

Fracture- Yes/No

If yes:

If yes:

If yes:

If yes:

If yes, specify-

- v)

Amputation: Yes/No

If yes:

- h)

Consciousness level following accident- Conscious/ Unconscious

- i)

GCS at the time of admission at the Level I Trauma Centre-

- j)

Whether the victim was-

A pedestrian- Yes/ No

Inside a vehicle- Yes/No

If yes,

If yes, whether the victim wore a helmet? – Yes/ No

Three-wheeler - Yes/ No

Four-wheeler – Yes/No

If yes, whether the victim had seat-belt on? – Yes/ No

Was the victim driving the vehicle? – Yes/ No

Before admission in the Level I Trauma Centre, whether taken to any other health facility- Yes/No

If yes:

Name of the facility-

Distance of the facility from the site of accident-

Whether went alone or accompanied by someone to the facility- Alone/ Accompanied by someone (specify)-

Time of attendance at the facility-

Received treatment at the facility- Yes/No

Whether referred to the Level I Trauma Centre of IPGME&R? – Yes/No

Whether undergone any major surgery following the accident? Yes/No

If yes, specify-

If yes, duration of stay -

PART III: FOLLOW-UP DATA COLLECTION (1ST, 2ND AND 3RD)

Only for 1st follow-up:

Duration of hospital stay (in days):

For 1st, 2nd and 3rd follow-up data collection:

Part 1. WHODAS 2.0 Scale (for disability assessment):

Domain I: Cognition

In the past 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in-

- a)

Concentrating in doing something for 10 mins?

- b)

Remembering to do important things?

- c)

Analysing and finding solutions to problems in day-to-day life?

- d)

Learning a new task, for example, learning how to get to a new place?

- e)

Generally understanding what people say?

- f)

Starting and maintaining a conversation?

Domain II: Mobility

In the past 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in-

- a)

Standing for long periods such as 30 minutes?

- b)

Standing up from sitting down?

- c)

Moving around inside your home?

- d)

Getting out of your home?

- e)

Walking a long distance such as a kilometre [or equivalent]?

Domain III: Self-care

In the past 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in-

- a)

Washing your whole body?

- b)

Getting dressed?

- c)

Eating?

- d)

Staying by yourself for few days?

Domain IV: Getting along

In the past 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in-

- a)

Dealing with people you do not know?

- b)

Maintaining a friendship?

- c)

Getting along with people who are close to you?

- d)

Making new friends?

- e)

Sexual activities?

Domain V: Life activities

In the past 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in-

- a)

Taking care of your household responsibilities?

- b)

Doing most important household tasks well?

- c)

Getting all the household work done that you needed to do?

- d)

Getting your household work done as quickly as needed?

- e)

Your day-to-day work/school?

- f)

Doing your most important work/school tasks well?

- g)

Getting all the work done that you need to do?

- h)

Getting your work done as quickly as needed?

Domain VI: Participation

In the past 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in-

- a)

How much of a problem did you have joining in community activities (for example, festivities, religious or other activities) in the same way anyone else can?

- b)

How much of a problem did you have because of barriers or hindrances in the world around you?

- c)

How much of a problem did you have living with dignity because of the attitudes and actions of others?

- d)

How much time did you spend on your health condition, or its consequences?

- e)

How much have you been emotionally affected by your health condition?

- f)

How much has your health been a drain on the financial resources of you or your family?

- g)

How much of a problem did your family have because of your health problems?

- h)

How much of a problem did you have in doing things by yourself for relaxation or pleasure?

| None |

Mild |

Moderate |

Severe |

Extreme/Cannot do |

| 0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Part II. PTSD Checklist for DSM 5 (PCL-5)

| Questions |

Not at all

0

|

Little bit

1

|

Moderately

2

|

Quite a bit

3

|

Extremely

4

|

| 1. Repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of the stressful experience? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Repeated, disturbing dreams of the stressful experience? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Suddenly feeling or acting as if the stressful experience were actually happening again (as if you were actually back there reliving it)? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. Feeling very upset when something reminded you of the stressful experience? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. Having strong physical reactions when something reminded you of the stressful experience (for example, heart pounding, trouble breathing, sweating)? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. Avoiding memories, thoughts, or feelings related to the stressful experience? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 7. Avoiding external reminders of the stressful experience (for example, people, places, conversations, activities, objects, or situations)? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 8. Trouble remembering important parts of the stressful experience? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 9. Having strong negative beliefs about yourself, other people, or the world (for example, having thoughts such as: I am bad, there is something seriously wrong with me, no one can be trusted, the world is completely dangerous)? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 10. Blaming yourself or someone else for the stressful experience or what happened after it? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 11. Having strong negative feelings such as fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 12. Loss of interest in activities that you used to enjoy? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 13. Feeling distant or cut off from other people? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 14. Trouble experiencing positive feelings (for example, being unable to feel happiness or have loving feelings for people close to you)? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 15. Irritable behaviour, angry outbursts, or acting aggressively? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 16. Taking too many risks or doing things that could cause you harm? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 17. Being “super alert” or watchful or on guard? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 18. Feeling jumpy or easily startled? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 19. Having difficulty concentrating? |

|

|

|

|

|

| 20. Trouble falling or staying asleep? |

|

|

|

|

|

PART III: Socio-Economic Impact of RTA

-

A.

Social Impact:

- 1.

Was the victim being neglected by family/friends/neighbors/other acquaintances following RTA? – Yes/No

- 2.

Was the victim made fun of/ being insulted by others following the RTA- Yes/No

- 3.

Did the victim receive any rehabilitative services? – Yes/No. If yes, specify-

If no, give reason (s) -

-

B.

Economic Impact:

- 1.

For how many days was the victim absent from his job following the accident?

- 2.

Any loss of wages of the victim following the RTA? – Yes/No

- 3.

Has the performance of the victim reduced at the workplace following the accident? – Yes/ No

- 4.

Did the victim opt for a different job following the accident? – Yes/No

If yes:

Reason(s) – Specify

How many days after the previous job?

Was there any change in salary? – Yes/ No

If yes, whether the current salary is more/less than previous salary? – More / Less

- 5.

How much money was spent for treatment following the accident (hospital admission+ follow-up visits) in Rs. -

- 6.

Did the victim get any accident policy/ claim for treatment? – Yes/No

If yes, how much (in Rs.) -

- 7.

Did the victim take any loan for treatment following the accident? – Yes/ No

If yes, how much (in Rs.)-

Mode of repaying the loan (specify)-

- 8.

Was there any out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure of the victim due to RTA? – Yes/ No. If yes:

Reason(s) – Specify

Reason(s) - Specify

References

- World Health Organization. Road traffic injuries. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact- sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries, accessed on 24 December 2024.Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196.

- United Nations. Fact Sheet Road Safety. Sustainable Transport Conference, 14-16 October 2021, Beijing. Available online: Chrome- extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/media_gstc/FACT_SHEET_Road_safety.pdf, accessed on 24 December 2024. Author 1, A.B.; Author 2, C. Title of Unpublished Work. Abbreviated Journal Name year, phrase indicating stage of publication (submitted; accepted; in press).

- Observer Research Foundation. Why are road accidents in India are on the rise? Available online: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/why-are-road-accidents-in-india-on-the-rise, accessed on 24 December 2024.

- Nanjunda, D.C. Impact of socio-economic profiles on public health crisis of road traffic accidents: A qualitative study from South India. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2021, 9, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicholkar, A.; Cacodcar, J.A. A study of road traffic injury victims at a tertiary care hospital in Goa, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022, 11, 5490–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Sarkar, D.; Mallick, N. A study on the socio-demographic profiles of road traffic accident cases attending a peripheral tertiary care medical College hospital of West Bengal. J Evidence Based Med. 2021, 8, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghnam, S.; Alkelya, M.; Aldahnim, M.; Aljerian, N.; Albabtain, I.; Alsayari, A.; et al. Healthcare costs of road injuries in Saudi Arabia: A quantile regression analysis. Accid Anal Prev. 2021, 159, 106266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rissanen, R.; Berg, H.Y.8; Hasselberg, M. Quality of life following road traffic injury: A systematic literature review. Accid Anal Prev. 2017, 108, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papic, C.; Kifley, A.; Craig, A.; Grant, G.; Collie, A.; Pozzato, I.; et al. Factors associated with long term work incapacity following a non-catastrophic road traffic injury: Analysis of a two-year prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2022, 22, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, M.; Radhakrishnan, R.V.; Mohanty, C.R.; Behera, S.; Singh, A.K.; Sahoo, S.S.; et al. Clinicoepidemiological profile of trauma patients admitting to the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in eastern India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020, 9, 4974–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Undavalli, C.; Das, P.; Dutt, T.; Bhoi, S.; Kashyap, R. PTSD in post-road traffic accident patients requiring hospitalization in Indian subcontinent: A review on magnitude of the problem and management guidelines. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2014, 7, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Mahima; Srivastava, D.K.; Kharya, P.; Sachan, N.; Kiran, K. Analysis of risk factors contributing to road traffic accidents in a tertiary care hospital. A hospital based cross-sectional study. Chin J Traumatol. 2020, 23, 159–162. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Iverson, L.M. Glasgow Coma Scale. [Updated 2023 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513298/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- World Health Organization. Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. WHODAS 2.0. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/whodas-20-instrument.pdf, accessed on 10 January 2025.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Available online: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- PCL-5: Scoring and interpretation [Internet]. Comorbidity Guidelines. Available online: https://comorbidityguidelines.org.au/appendix-s-ptsd-checklist-for-dsm5-pcl5/pcl5-scoring-and-interpretation (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Esiyok, B.; Korkusuz, I.; Canturk, G.; Alkan, H.A.; Karaman, A.G.; Hamit Hanci, I. Road traffic accidents and disability: A cross-section study from Turkey. Disability and Rehabilitation 2005, 27, 1333–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, J.P. Disabilities caused by road traffic accidents and their relation to severity scores. Accid Anal Prev. 1985, 17, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmera-Suárez, R.; López-Cuadrado, T.; Almazán-Isla, J.; Fernández-Cuenca, R.; Alcalde-Cabero, E.; Galán, I. Disability related to road traffic crashes among adults in Spain. Gaceta Sanitaria 2025, 29, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekadu, W.; Mekonen, T.; Belete, H.; Belete, A.; Yohannes, K. Incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder after road traffic accident. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frommberger, U.H.; Stieglitz, R.-D.; Nyberg, E.; Schlickewei, W.; Kuner, E.; Berger, M. Prediction of posttraumatic stress disorder by immediate reactions to trauma: A prospective study in road traffic accident victims. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998, 228, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chossegros, L.; Hours, M.; Charnay, P.; Bernard, M.; Fort, E.; Boisson, D.; et al. Predictive factors of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder 6 months after a road traffic accident. Accid Anal Prev. 2011, 43, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Bagepally, B.S.; Shankara, B.; Sasidharan, A.; Jagadeesh, K.V.; Ponniah, M. State-wise economic burden of road traffic accidents in India. medRxiv preprint. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.12.21.23300419v1.full.pdf, accessed on 12 December 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gorea, R. Financial impact of road traffic accidents on the society. Int J Ethics Trauma Victimology 2016, 2, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Transport Safety Council (ETSC). Social and economic consequences of road traffic injury in Europe. Brussels: 2007 p. 23.

- Verma, P.; Gupta, S.; Misra, S.; Agrawal, R.; Agrawal, V.; Singh, G. Road traffic accidents: A lifetime financial blow the victim cripples under. Indian J Community Health. 2015, 27, 257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Prinja, S.; Jagnoor, J.; Sharma, D.; Aggarwal, S.; Katoch, S.; Lakshmi, P.V.; et al. Out-of-pocket expenditure and catastrophic health expenditure for hospitalization due to injuries in public sector hospitals in North India. PLoS ONE. 2019, 14, e0224721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blincoe, L.J.; Miller, T.R.; Zaloshnja, E.; Lawrence, B.A. The economic and societal impact of motor vehicle crashes, 2010. (Revised) (Report No. DOT HS 812 013). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, May 2025. http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/812013.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).