Submitted:

20 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

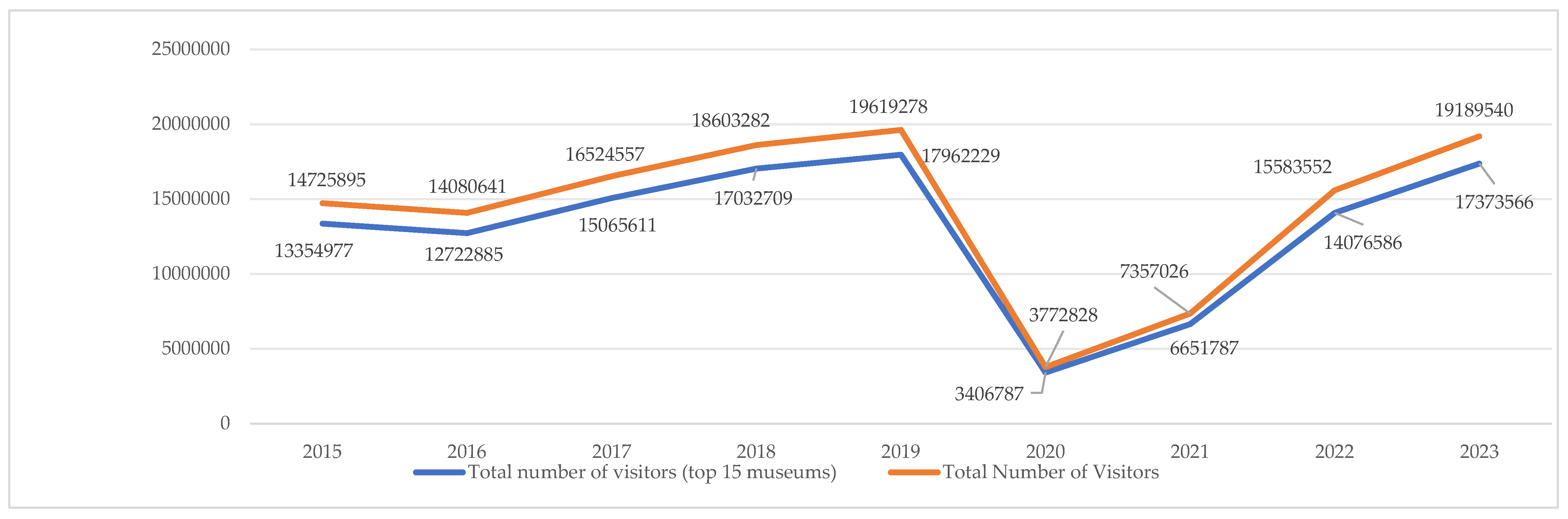

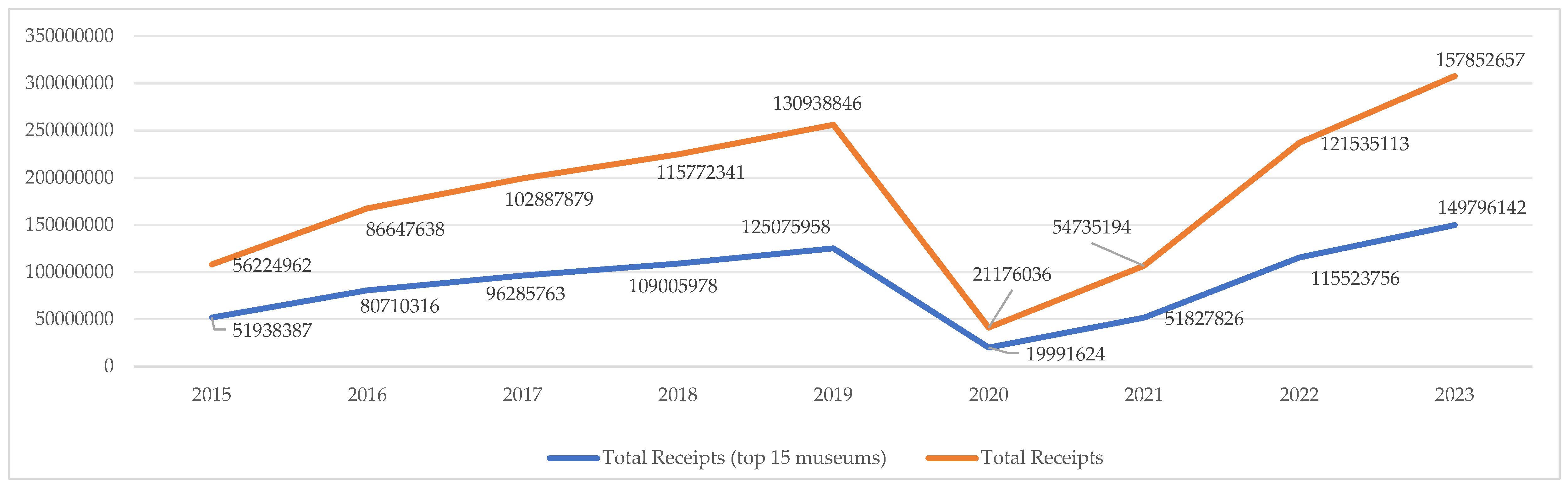

1. Introduction: Museums and Cities

‘The Museum is a non-profit organization, permanently at the service of the society in which it researches, collects, preserves, interprets, and exhibits the tangible and intangible cultural heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums support diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, providing diverse experiences for education, entertainment, reflection, and knowledge dissemination’ [9]

2. Marketing Museums and the Role of Promotional Policies

3. Some Previous Studies in Brief

4. The Studied Marketing (Promotional) Policies

5. Methodology

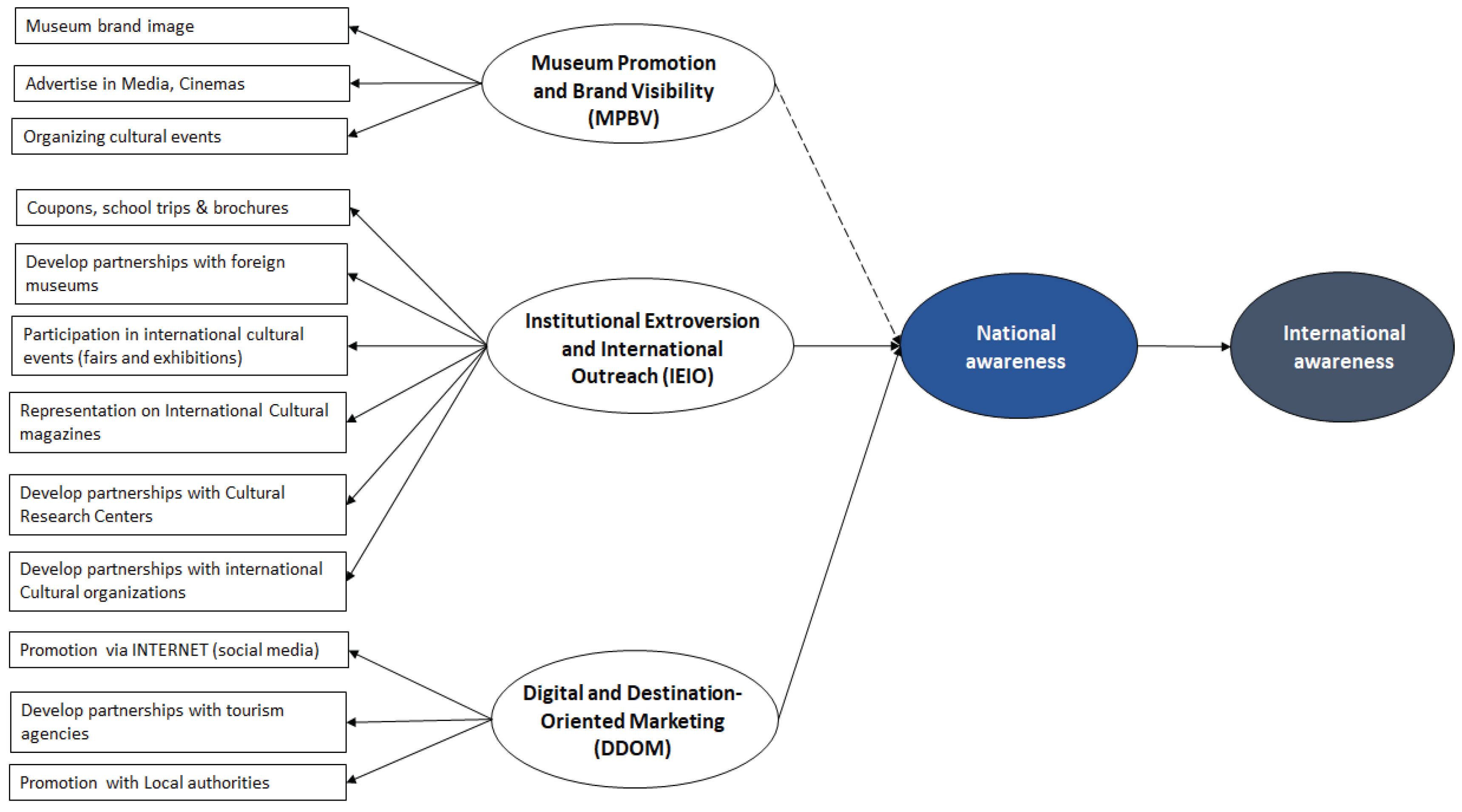

5.1. Research Questions and Hypotheses

| Research Questions | Hypotheses |

| To what extent do different types of marketing strategies adopted by public museums in Greece influence their national visibility? (RQ1) |

H2: Digital and Destination-Oriented Marketing (DDOM) has a positive effect on National Awareness. H3: Institutional Extroversion and International Outreach (IEIO) has a positive effect on National Awareness. H4: Museum Promotion and Brand Visibility (MBV) has a positive effect on National Awareness. |

| How does national visibility influence the international awareness of public museums? (RQ2) | H1: National Awareness has a positive effect on International Awareness. |

5.2. Research Process

5.3. Methods of Analysis

6. Analysis

6.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

6.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

6.3. Structural Model

6.4. Independent T-Tests

7. Discussion

8. Limitations and Future Research

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ginsburgh, V. , and Mairesse F. Defining a Museum: Suggestions for an Alternative Approach, Museum Management and Curatorship 1997, 16, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, S.E. , (1990). Rethinking the museum and other Meditations, S: DC.

- Taylor, P. M. Collecting Icons of Power and Identity: Transformation of Indonesian Material Culture in the Museum Context. Cultural Dynamics 1995, 7, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, H. Into the Heart of Irony: Ethnographic Exhibitions and the Politics of Difference. The Sociological Review 1995, 43 (Suppl. S1), 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, S. State Authority and the Public Sphere: Ideas on the Changing Role of the Museum as a Canadian Social Institution. Museum & Society 2015, 3, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P. A. Am I the public I think I am? Understanding the public curriculum of museums as “complicated conversation.” Journal of Museum Education 2006, 31, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetman, R. , Hadfield, A., & O’Connor, A. Material Culture, Museums, and Memory: Experiments in Visitor Recall and Memory. Visitor Studies 2020, 23, 18–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aalst, I.; Boogaarts, I. From Museum to Mass Entertainment: The Evolution of the Role of Museums in Cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2002, 9, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOM. Final Report of the Extraordinary General Assembly, ICOM Approves a New Museum Definition. Prague, Czech Republic, 24 August 2022. Available online: https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/EN_EGA2022_MuseumDefinition_WDoc_Final-2.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Johnson, P. , & Thomas, B. The Economics of Museums: A Research Perspective. Journal of Cultural Economics 1998, 22, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Camarero, C. , & Garrido, M.-J. Improving Museums’ Performance Through Custodial, Sales, and Customer Orientations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 2008, 38, 846–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A. and Rentschler, R. Changes in Museum Management: A Custodial or Marketing Emphasis? Journal of Management Development 2002, 21, 745–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, J. , Munday M., Bevins R. Developing a framework for assessing the socioeconomic impacts of museums: The regional value of the ‘flexible museum’. Urban Studies 2012, 49, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. Cultural-products industries and urban economic development Prospects for Growth and Market Contestation in Global Context. Urban Aff. Rev. 2004, 39, 461–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffner, A. and Metaxas, T. In The Interrelationship of Urban Economic and Cultural Development: The Case of Greek Museums. In Proceedings of the 43rd European Congress of the Regional Science Association (ERSA) University of Jyvaskyla, Jyväskylä, Finland, 27–30 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Currid, E. How Art and Culture Happen in New York. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2007, 73, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufts, S. and Milne, S. Museums: A supply side perspective, Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, A.B. , 92001). ‘Cultural Industry as a development chance for Poland’ paper presented at the Conference organized by the Gdansk Institute for Market Economics, Warsaw, Poland, June 13.

- Bonet, L. 92003). “Cultural tourism,” Chapters, in: Ruth Towse (ed.), A Handbook of Cultural Economics, chapter 23, Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Scott, C. Museums: Impact and value. Cultural Trends 2006, 15, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwwod, S. Great Expectations: Museums and Regional Economic Development in England. Curator The Museum Journal 2010, 49, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. Museums and Local Development: An Introduction to Museums, Sustainability and Well-being. Museum International 2019, 71, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsey, B. ‘The economic impact of museums and cultural attractions: Another benefit for community’. In Proceedings of the paper presented to the Annual Meeting of the American Association of Museums, Dallas, Texas, 14 May 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, F. Services Marketing: The Case of Museums. Serv. Ind. Journal 1994, 14, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Asplund, C.; Rein, I.; Haider, H.D. Marketing Places Europe: Attracting Investments, Industries and Visitors to European Cities, Communities, Regions, and Nations; Financial Times/Prentice Hall: Harlow, ND, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, P.F. The changing nature of information work in museums. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 2007, 58, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodach, C. Museums as Urban Catalysts: The Role of Urban Design in Flagship Cultural Development. Journal of Urban Design 2008, 13, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramposch, J.W. ‘Te Papa: Reinventing the Museum’. Museum Management and Curatorship 1998, 17, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. and van Rekom, J. ‘Scanning museum visitors’. Annals of Tourism Research 1996, 23, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, D. ‘McGuggenisation? National identity and globalization in the Basque county’ Political Geography 2000, 19, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, B. 2000; 27. [CrossRef]

- Plaza, B. The Return on Investment of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 2006, 30, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, M. , & Plaza, B. Renewal through culture? The role of museums in the renewal of industrial regions in Europe. European Planning Studies 2015, 23, 1441–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, B. , González-Casimiro, P., Moral-Zuazo, P., & Waldron, C. Culture-led city brands as economic engines: theory and empirics. The Annals of Regional Science 2015, 54, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, A.C. and Klemm, S. M. ‘Tourism in difficult areas revisited: the case of Bradford’, Tourism Management 2001, 22, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, A. and Jonas, A. ‘Reimagining Berlin: World city, national capital or ordinary place?, European Urban and Regional Studies 1999, 6, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C. , Miles, S. and Stark, P. Culture-led urban regeneration and the revitalisation of identities in Newcastle, Gateshead and the North East of England, International Journal of Cultural Policy 2004, 10, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustí i P., D. Differences in the location of urban museums and their impact on urban areas. International Journal of Cultural Policy 2013, 20, 471–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuqin, D. The Role of Natural History Museums in the Promotion of Sustainable Development. Museum International 2008, 60, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou-Lambert, T. Gazing from home: Cultural tourism and art museums. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst D, Esche C. and Erbslöh U. The art museum as lab to re-calibrate values towards sustainable development, Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 135, 1446–1460. [CrossRef]

- Azmat, F. & Ferdous, A., Rentschler, R. & Winston, E. Arts-based initiatives in museums: Creating value for sustainable development. Journal of Business Research 2018, 85, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, I. L. , Borza, A., Buiga, A., Ighian, D., & Toader, R. Achieving Cultural Sustainability in Museums: A Step Toward Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. , Duan Y. , Yang X., Cao C. and Pan S. ‘Smart Museum’ in China: From technology labs to sustainable knowledgescapes, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 2023, 38, 1340–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konsola, D. Cultural Politics and Development; Papazisis: Athens, Greece, 2006. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Lazarinis, F.; Kanellopoulos, D.; Lalos, P. Heuristically Evaluating Greek e-Tourism and e-Museum Websites. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Eval. 2008, 11, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Katsaridou, I. and Biliouri, K. In 2007. ‘Representing Byzantium: the narratives of the Byzantine past in Greek national museums’, in P. Aronsson and M. Hillström (eds) NaMu. In Proceedings of the Making National Museums, Setting the Frames, Norrköping, Sweden 26-27 February.

- Buhalis, D. , & Deimezi, O. E-Tourism Developments in Greece: Information Communication Technologies Adoption for the Strategic Management of the Greek Tourism Industry. Tourism and Hospitality Research 2004, 5, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, K. 2008. 2008, Digital Heritage in the new knowledge environment.: Shared spaces & open paths to cultural content. Hellenic Ministry of Culture, p.

- Zafeiri, K. and Gavalas D. Museums Shops:Experiences gained from developing electronic and mobile commerce solutions. International Scientific Electronic Journal of Museology 2009, 5, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zyglidopoulos, S. , Symeou, P. C., Bantimaroudis, P., & Kampanellou, E. Cultural Agenda Setting: Media Attributes and Public Attention of Greek Museums. Communication Research 2012, 39, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliadis, C. and, Belenioti Z-C. Museums and cultural heritage via social media: An integrated literature review. Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism 2017, 12, 97–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanatidis, D. , Mylona, I., Mamalis, S. & Kamenidou, I. Social media for cultural communication: A critical investigation of museums’ Instagram practices. Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing 2020, 6, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, N. Knowing the Public. A Review of Museum Marketing Literature and Research. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 1998, 17, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentschler, R. Museum and Performing Arts Marketing: The Age of Discovery. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 2002, 32, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. Museum marketing as a tool for survival and creativity: the mining museum perspective. Museum Management and Curatorship 2008, 23, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, A. , Eagle L., Confetto M. G., Siglioccolo M. Destination competitiveness and museum marketing strategies: an emerging issue in the Italian context, Museum management and Curatorship 2010, 25, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero, C. , Garrido M-J. & Vicente E. Does it pay off for museums to foster creativity? The complementary effect of innovative visitor experiences, Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2019, 36, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. , Andersen A. R. (1996). Strategic Marketing for Non-Profit Organizations.

- Rentschler, R. , and Hede A. Museum marketing: Competing in the globalmarketplace; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Héroux, L. and Csipak J. Marketing Strategies of Museums in Quebec and Northeastern United States, Téoros 2008, 27, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tobelem, J. The Marketing Approach in Museums. Museum Management and Curatorship 1997, 16, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. , & Levy, S. J. Broadening the Concept of Marketing. Journal of Marketing 1969, 33, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffner, A. and Metaxas T. In Shaping the vision, the identity and cultural image of European places. In Proceedings of the 45th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: “Land Use and Water Management in a Sustainable Network Society”, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 23-27 August 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, N. and Kotler, P. (2007). Can museums be all things to all people?: Missions, goals, and marketing’s role. In Museum management and marketing (pp. 313-330). Routledge.

- Stephen, A. The Contemporary Museum and Leisure: Recreation As a Museum Function. Museum Management and Curatorship 2001, 19, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusa, S. and Uusitalo, L. Creating brand identity in art museums: A case study. International Journal of Arts Management 2014, 17, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, T. 1984; 94. [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, A. Professional Artists in Vietnam: Intellectual Property Rights, Economic and Cultural Sustainability. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 2009, 39, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.L. Cu Chi tunnels: Vietnamese transmigrant’s perspective. Annals of Tourism Research 2014, 46, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusa, S. (2009). Creating Brand Identity in Art Museums – A Case Study on Three Art Museums, Master Thesis, Department of Marketing, Aalto University.

- Munk, J. i: Terezín Memorial, 1998; 17. [CrossRef]

- Mejón, J. C. , Fransi, E. C., & Johansson, A. T. Marketing Management in Cultural Organizations: A Case Study of Catalan Museums. International Journal of Arts Management 2004, 6, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, K. , & Roach, G. The strategic role of electronic marketing in the Australian museum sector. Museum Management and Curatorship 2011, 26, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, E. , Camarero, C., & Garrido, M. J. Insights into Innovation in European Museums: The impact of cultural policy and museum characteristics. Public Management Review 2012, 14, 649–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luscombe, A. , Walby, K., & Piché, J. Making Punishment Memorialization Pay? Marketing, Networks, and Souvenirs at Small Penal History Museums in Canada. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2015, 42, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, A. , & Jaffry, S. A Choice Modeling Application for Greek Heritage Attractions. Journal of Travel Research 2005, 43, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavragani, E. Greek Museums and Tourists’ Perceptions: an Empirical Research. J Knowl Econ 2021, 12, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, S. , Arabatzis G. and Tsiantikoudis S. The attractiveness of archaeological sites in Greece: a spatial analysis, International Journal of Tourism Policy 2007, 1, 246–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffner, A. , Metaxas T. and Syrakoulis K. Museums, Marketing and Tourism Development: The case of Tobacco Museum of Kavala, Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism 2009, 4, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulaptsi, I. , and Tsourvakas G. Visitor-oriented strategic museum management for small regional museums. The Greek case of the Ethnological Museum of Thrace. Journal of Regional & Socio-Economic Issues. [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, G. , & Fouseki, K. Introduction: Managing Archaeological Sites in Greece. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 2013, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoura, A. and Bitsani, E., Managing the World heritage site of the acropolis, Greece. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 2013, 7, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garezou, M. , & Keramidas, S. Greek Museums at a Crossroads: Continuity and Change. Museum International 2017, 69, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R. B. Personal Relationships and Social Change: The `Realpolitik’ of Cross-Cultural Research in Transient Cultures. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 1998, 15, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, C. Exploring Museum Marketing Performance: A Case Study from Italy. International Journal of Marketing Studies 2010, 2, 1, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L. and Boyle, E. The role of partnerships in the delivery of local government museum services: A case study from Northern Ireland”, International Journal of Public Sector Management 2004, 17, 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, K.; (2005). ‘Strategic partnerships’, Best Practices module, British Columbia Museums Association. Available online: http://museumsassn.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/BP-8-Strategic-Partnerships.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- Zhang, Y. , & Liu, H. Understanding visitors’ leisure benefits and heritage meaning-making: a case study of Liangzhu Culture Museum. Leisure Studies 2021, 40, 872–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, R. The promotion of cultural tourism on the level of Belgrade as a tourist destination. UTMS Journal of Economics 2010, 1, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, N.G. The emergence of museum brands. International Journal of Arts Management 2000, 2, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarth, C. Brand orientation of museums: Model and empirical results. International Journal of Arts Management 2009, 11, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pančíková, K. , Veselovský, J., Gergelyová, V. and Dávid, L.D. The importance of exhibitions and organised events of museums and galleries in tourism. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development 2024, 8, 9626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaremen, D.E. and Rapacz, A. Cultural events as a method for creating a new future for museums. Cultural events as a method for creating a new future for museums. Turyzm 2018, 28, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienkowski, P. A: systems in museums, 1994; 13. [CrossRef]

- Johanson, L. B. , & Olsen, K. Alta Museum as a tourist attraction: the importance of location. Journal of Heritage Tourism 2010, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, H. and Allen, D. Cultural tourism in Central and Eastern Europe: the views of ‘induced image formation agents’. Tourism Management. [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.F. Developing industrial heritage tourism: A case study of the proposed jeep museum in Toledo, Ohio. Tourism management 2006, 27, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffner, A. and Metaxas, T. The city marketing pilot plan of Nea Ionia, Magnesia, Greece: an exercise in branding. Journal of Town & City Management.

- Rouwendal, J. and Boter, J. (2005). Assessing the Value of Museums with a Combined Discrete Choice/Count Data Model. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper No. 2005; /3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, F. Improving visitor care in heritage attractions. Tourism Management 1995, 16, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S. Superstar museums: An economic analysis. Journal of cultural economics, /: 113-125. http, 4181. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, P. , & Leask, A. Visitor engagement at museums: Generation Y and ‘Lates’ events at the National Museum of Scotland. Museum Management and Curatorship 2017, 32, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.W. , J.M., Lin, Q.P. and Chang, M. E-learning: The Strategies of learning culture and arts. In International Conference on Technologies for E-Learning and Digital Entertainment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, B. State Of The State Of Teaching Public History. Teaching History: A Journal of Methods 1993, 18, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsall, D.A. , Railway heritage and the tourist gaze: Stoomtram Hoorn–Medemblik. Journal of Transport Geography 2001, 9, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung T-L. , Marcketti S. & Fiore A.M. Use of social networking services for marketing art museums, Museum Management and Curatorship 2014, 29, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, J.M. , Arilla R. & Gómez A. Facebook as a Promotional Tool for Spanish Museums 2016–2020 and COVID Influence, Journal of Promotion Management 2021, 27, 812–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. Towards Cultural Democracy: Museums and their Communities. Museum International 2019, 71, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigerl, M. , Sanahuja-Gavaldà J.M., Petrinska-Labudovikj R., Moron-Velasco M., Rojas-Pernia S. and Tragatschnig U. Collaboration between schools and museums for inclusive cultural education: Findings from the INARTdis-project. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 979260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberberg, T. 1995; 16. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M. Museum Branding: How to Create and Maintain Image, Loyalty, and Support, 2nd eds.; Rowman and Littlefield (eds): London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice, R. Experiential Cultural Tourism: Museums & the Marketing of the New Romanticism of Evoked Authenticity. Museum Management and Curatorship 2001, 19, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababneh, A. Tour guides and heritage interpretation: guides’ interpretation of the past at the archaeological site of Jarash, Jordan. Journal of Heritage Tourism 2018, 13, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, M. e: role of tourism guides in heritage management at archaeological sites, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, N. 2008; 63. [CrossRef]

- Mottner, S. Retailing and the museum: applying the seven ‘P’s of services marketing to museum stores, in Ruth Rentschler and Anne-Marie Hede. In Museums Marketing, 1st eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Metaxas, T. (2013). 4: From city marketing to museum marketing and opposed, MPRA paper, 4696. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreiro-Rosende, É. , Fuentes-Moraleda, L., & Morere-Molinero, N. Artists brands and museums: understanding brand identity. Museum Management and Curatorship 2021, 38, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, M.F. and Kasim, A. Motivations for visiting and not visiting museums among young adults: A case study on UUM students. Journal of global management.

- Silverstone, R. A: and the media, 1988; 7. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; et al. , “Cross-Reality Interaction and Collaboration in Museums, Education, and Rehabilitation,” 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), Sydney, Australia, 2023, pp. [CrossRef]

- Rentschler, R. Hede, A-M. and Ramsey, T. (2004). Pricing in the museum sector : the need to balance social responsibility and organisational viability. Deakin University. Conference contribution. https://hdl.handle. 1053. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, R. , Manna, R. and Cavallone, M. The managerialization of museums and art institutions: perspectives from an empirical analysis. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 2022, 30, 1397–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N. and Birks, D. Marketing Research: An Applied Approach, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N. and Birks, D. Marketing Research: An Applied Approach, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lance, C.E. and Vandenberg, R.J. Confirmatory factor analysis. In Measuring and Analyzing Behavior in Organizations: Advances in Measurement and Data Analysis; Drasgow, F., Schmitt, N., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 221–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Krey, N. Covariance-based structural equation modeling in the Journal of Advertising: Review and recommendations. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. (2008). Evaluating model fit: A synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, London, UK. pp. 195–200.

- Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J. , & Powell, W. W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American sociological review 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J. , & Powell, W. W. (2000). The iron cage revisited institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. In Economics meets sociology in strategic management (pp. 143-166). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Petrakos, G. , & Saratsis, Y. Regional inequalities in Greece. Papers in Regional Science 2000, 79, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Petrakos, G. , Rontos, K., Vavoura, C., & Vavouras, I. The impact of recent economic crises on income inequality and the risk of poverty in Greece. Economies 2023, 11, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A. , Walia, S. K., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. Gen Z and the flight shame movement: examining the intersection of emotions, biospheric values, and environmental travel behaviour in an Eastern society. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2024, 32, 1621–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSETE https://insete.

| Marketing (Promotional) Policies (MP) | Codes | Some Related studies |

|---|---|---|

| Develop partnerships with tourism agencies | b1 | Deffner et al., [80]; Johanson and Olsen [96] |

| Develop partnerships with foreign museums | b2 | Hughes and Allen [97]; Xie [98]; Deffner and Metaxas [99] |

| Develop partnerships with international Cultural organisations | b3 | Rouwendal and Boter [100]; Schouten [101] |

| Develop partnerships with Local Authorities | b4 | Deffner et al., [80]; Frey [102] |

| Planning and organising cultural events | b5 | Bienkowski [95]; Baron and Leask [103] |

| Participation in international cultural events (fairs and exchbitions) | b6 | Kuo et. al., [104] |

| Promotion via INTERNET (social media) and virtual / digital apps | b7 | Howe [105]; Halsall [106]; Chung et al. [107]; Mas et al., [108] |

| Develop partnerships with Cultural Research Centres | b8 | Anderson [109]; Gigerl et al., [110] |

| Representation on International Cultural magazines | b9 | Silberberg [111]; Wallace [112] |

| Promotion via Cultural and Tourism Guides | b10 | Prentice, [113]; Ababneh [114]; Khater [115] |

| Production of a Cultural-Museum Journal | b11 | Cole [56]; Robbins [116] |

| Existence of Museum’s Marketing Plan | b12 | Mottner [117]; Deffner et al., [80]; Metaxas [118] |

| Develop of Museum Brand Image | b13 | Pusa and Uusitalo [67]; Ferreiro-Rosente et al., [119] |

| Participation in European Cultural Programmes | b14 | Frey [102]; Plaza [31] |

| Promotion via Coupons, school trips, brochures | b15 | Prentice [113]; Mokhtar and Kasim [120] |

| Promotion via MEDIA (TV, cinema et al.) | b16 | Silverstone [121]; Xia et al., [122] |

| Promote attractive pricing policies generally | b17 | Rentschler et al., [123]; Palumpo et al., [124] |

| MUSEUMS | REGION |

|---|---|

| Acropolis of Athens*- Acropolis Museum - National Archaeological museum | Attica |

| Mykines* - Mystras - Ancient Olympia - Ancient Korinthos - Epidavros* | Peloponnese |

| Delfi | Central Greece |

| Dilos*- Palace of Great Magistros | South Aegean |

| Iraklio -Knossos | Crete |

| Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum - White Tower Museum | Central Macedonia |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loadings | Cronbach A |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1: Museum Promotion and Brand Visibility | Museum brand image | 0.905 | 0.777 |

| Advertise in Media, Cinemas | 0.737 | ||

| Organizing cultural events | 0.519 | ||

| F2: Institutional Extroversion and International Outreach | Coupons, school trips & brochures | 0.597 | 0.880 |

| Develop partnerships with foreign museums | 0.680 | ||

| Participation in international cultural events (fairs and exhibitions) | 0.659 | ||

| Representation on International Cultural magazines | 0.525 | ||

| Develop partnerships with Cultural Research Centres | 0.571 | ||

| Participation in European Cultural Programmes | 0.416 | ||

| Develop partnerships with international Cultural organisations | 0.453 | ||

| F3: Digital and Destination-Oriented Marketing | Promotion via INTERNET (social media) | 0.851 | 0.893 |

| Develop partnerships with tourism agencies | 0.844 | ||

| Promotion with Local authorities | 0.601 | ||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin | 0.876 | ||

| Sig. | 0.000 |

| Factor | Indicator | Loadings | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Museum Promotion and Brand Visibility | Museum brand image (b13) | 0.882 | 0.572 | 0.796 |

| (MPBV) | Advertise in Media, Cinemas (b16) | 0.769 | ||

| Organizing cultural events (b5) | 0.588 | |||

| Institutional Extroversion and International Outreach (IEIO) | Coupons, school trips & brochures (b15) | 0.575 | 0.561 | 0.879 |

| Develop partnerships with foreign museums (b2) | 0.829 | |||

| Participation in international cultural events (fairs and exhibitions) (b6) | 0.917 | |||

| Representation on International Cultural magazines (b9) | 0.779 | |||

| Develop partnerships with Cultural Research Centres (b8) | 0.841 | |||

| Develop partnerships with international Cultural organisations (b3) | 0.438 | |||

| Digital and Destination-Oriented Marketing (DDOM) | Promotion via INTERNET (social media) (b7) | 0.962 | 0.765 | #break##break# 0.904#break##break# |

| Develop partnerships with tourism agencies (b1) | 0.996 | |||

| Promotion with Local authorities (b4) | 0.616 |

| Construct | AVE | CR | MPBV | IEIO | DDOM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPBV | 0.572 | 0.796 | 0.756 | ||

| IEIO | 0.561 | 0.879 | 0.599 | 0.748 | |

| DDOM | 0.765 | 0.7904 | 0.492 | 0.681 | 0.874 |

| Hypotheses | Structural Coefficient | p Value | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| H4: Impact of MBV on National awareness | -0.076 | 0.0691 | No Association |

| H3: Impact of IEIO on National awareness | 0.900 | <0.001 | Signified association |

| H2: Impact of DDOM on National awareness | 0.455 | <0.034 | Signified association |

| H1: Impact of National awareness on growth International awareness | 0.924 | <0.001 | Signified association |

| Dimension | Type of Museum | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness on national scale | City | 25 | 6.44 | .91 | .000 |

| Regional | 75 | 3.98 | 1.41 | ||

| Awareness on European scale | City | 25 | 5.64 | 1.38 | .000 |

| Regional | 75 | 2.45 | 1.38 | ||

| Awareness on international scale | City | 25 | 5.00 | 1.65 | .000 |

| Regional | 75 | 1.92 | 1.03 | ||

| Museum Promotion and Brand Visibility | City | 25 | 5.88 | .57 | .000 |

| Regional | 75 | 5.12 | .86 | ||

| Digital and Destination-Oriented Marketing | City | 25 | 6.30 | .49 | .000 |

| Regional | 75 | 5.40 | .83 | ||

| Institutional Extroversion and International Outreach | City | 25 | 6,1000 | .32 | .000 |

| Regional | 75 | 4,2733 | .87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).