1. Introduction

Digital nomads constitute an emerging group of both the global workforce and world

tourism. Academic research trends include, particularly after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, digital nomads’ motivations for selecting a nomadic lifestyle, as well as destination dynamics, in order to meet the specific needs of this recently surged tourism segment.

Although a widely accepted definition of the digital nomads phenomenon is yet to ensue, common or complementary features include independence from a permanent place of residence and work, the use of technology for working remotely, as well as community-building often facilitated by co-working spaces in destinations (Van der Broek et al., 2023). Digital nomads differentiate themselves from other types of nomadic lifestyle travellers by working remotely, though their travel profile and motivation partly overlap with other categories of work-related mobility (Richards, 2015, Hannonen, 2020, Cook 2020). Their prevailing profile foregrounds Millennial Westerners of high educational attainment and average income, often employed in the Research and Development (R&D) sector (Krippendorff, 2018, Chevtaeva & Denizci-Guillet, 2021, Poulaki et al., 2023, Flatio, 2023). Whether digital nomadism is a passing phase in life or a long-term lifestyle choice remains an open question (Hannonen, 2020), even though some research findings indicate that many digital nomads travel with their partners or families (Flatio, 2023).

Sense of freedom is often cited as the primary motive for choosing remote work and nomadic lifestyle, where achieving financial self-sufficiency is a means to personal development, rather than an end to itself (Reichenberger, 2017). Work-life balance remains the most important narrative (Miguel et al., 2023, Cook 2023), despite occasional scepticism regarding contribution to excessive mobility without serving actual needs (Cohen & Gossling, 2015), and even at the expense of frequent job changes, due to the distant nature of remote work (Richter & Richter, 2019). Although self-employment (eg. freelancer) is the stereotype employment status, the digital nomads community also includes groups of employees, travellers temporarily unemployed and remote workers yet not travelling (Cook, 2023).

As a resonance of the gig economy flexible working practices (Thomson, 2018), which saw a spectacular rising trend of 131% between 2019 and 2022 in the U.S. alone (UNWTO, 2023), post-pandemic dynamics can be attributed to the consolidation of new work and travel-related practices and lifestyles as the new normal in an ever-evolving technological context that enables flexible and remote work (Buhalis, 2022). Negative aspects of the phenomenon were also brought to light by COVID-19, such as the administrative challenges faced by digital nomads in accessing national health systems on private health insurance (Holleran, 2022) and additional epidemiological burdens placed on local communities (Holleran & Notting, 2023).

The emergence of the digital nomads phenomenon has rendered the identification of factors making a destination appealing, relevant to destination management. Visitor satisfaction from a destination is an integrated experience, that doesn’t decouple individual services provided (Buhalis, 2000), and includes internal motivation subjective elements (Cohen, 1979), prior expectations (Reitsamer et al., 2016), as well as pre-, during and post-visit stages (Cohen et al., 2013). Still, visitor satisfaction depends on measurable criteria upon a destination’s overall material and intellectual offer (Gearing et al., 1974, Dupeyras & MacCallum, 2013, Ul & Chaudhary, 2021), often considering destination supply and visitor needs in multifactorial methods (Raimkulov et al., 2021). Taking into account digital nomads’ specific expectations and needs, there is increasing interest in determining which generic and particular destination attractiveness factors can apply to the digital nomads target group (Lee et al., 2019, United Nations Development Programme, 2020, Technitis, 2021, Flatio, 2023). However, relevant studies outline distinct destination criteria, which occasionally overlap in research findings, while at other times differentiate from one another. It is, therefore, of interest to compare findings, in an attempt to identify the factors that are applicable to the digital nomad community, when adding a place to the list of potential future destinations.

In this paper, destination selection criteria are identified through literature review and benchmarking and organized into a methodological tool that meets the needs of digital nomads. The tool is then applied to the case study of Thessaloniki, through research with stakeholders and the digital nomad community. The findings offer the basis for discussion on the assessment of the tool’s validity, as well as its refinement through further research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Points of Reference for Data Collection

Relevant available literature and online sources have been reviewed, in order to identify the criteria upon which digital nomads select their destinations. The review included the Seven Layers Model (Technitis, 2021) on digital nomads’ priorities at a destination, Lee et al. (2019) digital ethnography findings from the analysis of digital nomads’ posts in online communities, the Global Remote Work Index (Nord Layer, 2023), the Digital Nomad Index (Circleloop, n.d.), quantitative research results on digital nomadism, conducted by a leading online housing rental platform for digital nomads (Flatio, 2023), and the mixed methods used in UNDP research on digital nomads’ criteria for selecting Serbia as a destination (United Nations Development Programme, 2020).

The Seven Layers Model (Technitis, 2021) identified seven key factors of destination attraction for digital nomads, based on qualitative research in stakeholder groups. The layers, namely cost of living, digital nomads community, work spaces, connectivity, mobility and transportation, environment and things to do, reflect the hierarchy of needs in terms of perceived significance to the target group.

Lee et al. (2019), through extensive digital ethnographic observation, identified eight main criteria that influence digital nomads' choice of destination: internet availability, climate and environment, cost of living, sense of community, culture and language, accessibility, time zone and security. They also mentioned other, important elements, like co-working and co-living spaces, as well as targeted socializing events, such as camps and retreats.

The Global Remote Work Index was created by the web services security company Nord Layer (2023), and ranks destination attractiveness factors for digital nomads at country level. Cybersecurity, financial security, digital and physical infrastructures, and social security are the factors that determine scores. To evaluate each factor, a number of specifications are taken into account.

The Digital Nomad Index was developed by Circleloop (n.d.), a company specialized in digital communication hardware and software. The criteria of destination selection, at country level, include connectivity speed, cost of internet, monthly rental cost, national policy for issuing the Digital Nomad Visa, the Happiness Index, the percentage of immigrants among the population, and yearly web searches for remote work job postings.

The results of an online survey conducted by the housing rental platform Flatio (2023) among a large sample of digital nomads, indicated that the main destination selection criteria were cost of living, sunny weather, security, quality of internet connection and of health services.

The United Nations Development Programme (2020) conducted a study on the digital nomads’ criteria for choosing Serbia as their destination. The study included secondary research on websites and social media and interviews conducted in co-working spaces, as well as small-scale quantitative research. The criteria that emerged for destination selection were, living expenses, transport infrastructures, cost of transport, weather, air quality, reliability and speed of internet connection, security, low levels of bureaucracy and corruption, international community, events and nightlife, culture and architecture, as well as gastronomy.

Destination selection criteria identified in the review of the literature were then compared for benchmark purposes with the relevant metrics in Nomad List (n.d.a), currently renamed Nomads.com, a crowdsourced database which serves as a valuable information source for digital nomads in selecting their destinations. The incidence of a criterion’s reappearance in the review was also used as consistency benchmark.

2.2. Methodological Tool

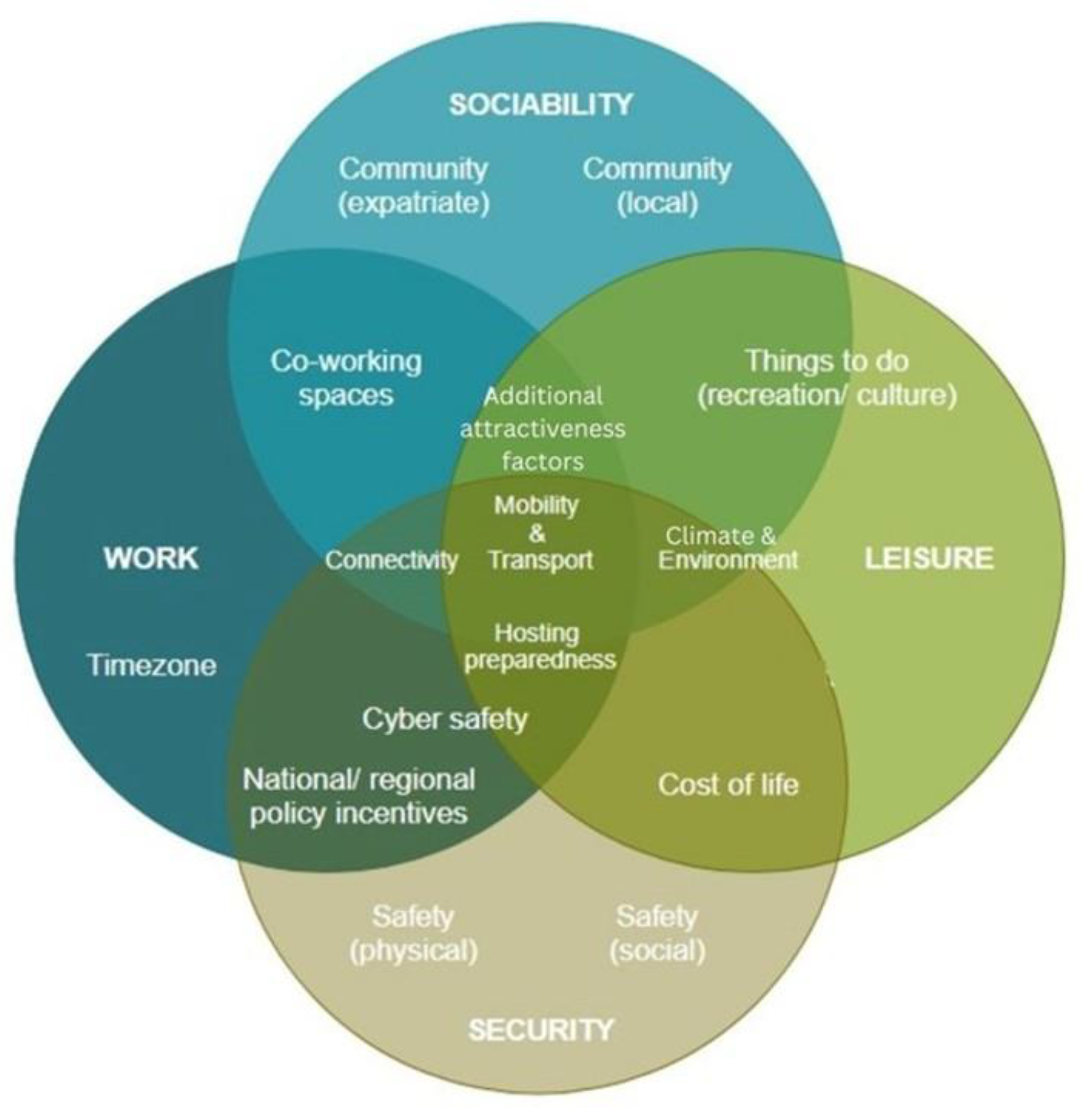

The destination selection criteria ensued were grouped in four priority areas of human needs, according to Maslow (1954) hierarchy of needs. This attempt is in line with earlier studies that endeavour to classify digital nomads’ objectives based on Maslow’s pyramid of human needs (Ahlberg, 2021), and to identify the significance of self-actualization to digital nomads, in contrast to the contentment of basic needs (Ehn et al., 2022). Four groups were identified: Security, Work, Sociability and Leisure. Security corresponds to the level of safety needs, upon the hypothesis that the lowest level of the pyramid, physiological needs, are already catered for when a person chooses the nomadic lifestyle while working remotely. Conversely, Work, Sociability and Leisure, are found to be mostly related to the pyramid’s social and self-esteem tiers. As for the highest level of human needs, self-actualization, it is argued that digital nomads seek to achieve fulfilment in personalized modes, by exploring new destinations (Yousaf et al., 2018).

The Venn diagram of overlapping circles, that illustrates the logical relation between the identified concepts (Bennett, 2015), was subsequently used to illustrate the four groups of digital nomads’ needs. Each circle included the corresponding destination selection criteria. Overlapping areas illustrate concurrences of criteria adhered to more than one group of needs.

2.3. The Case Study of Thessaloniki, Greece

A pilot study was deemed necessary in order to assess the validity and replicability potential of the methodological tool (Mershon & Shvetsova, 2019). The case study research method was selected on account of its potential to provide in-depth analysis (Fidel, 1984, Maggopoulos, 2014).

Thessaloniki, Greece’s second largest city and port, was selected as the case study destination due to its unique spatial characteristics attractive coastal environment, multicultural character developed by its historical context, strategic location at important maritime and road crossroads (Kostopoulou, 2023), transport connectivity and geographical proximity to popular 3S holidays destinations. The study area was considered at the Metropolitan level, since the administrative coherence of Thessaloniki Metropolitan Area in local development policymaking enables the implementation of development strategies and measures that address common challenges across the participating Municipalities (Metropolitan Thessaloniki, n.d.).

The Thessaloniki Metropolitan Area forms an integral part of NUTS 3 (EU Nomenclature of territorial units for statistics), comprising all but three out of the fourteen Municipalities that make up Thessaloniki Regional Unit (Official Journal of Greece, 2010). Thessaloniki also serves as the capital of the NUTS 2 Region of Central Macedonia (Eurostat, n.d.), home to slightly more than a million city dwellers, or 60% of the Region's population (Hellenic Statistical Authority, 2023). The per capita Gross Domestic Product of the Region of Central Macedonia is lower than the national average (Hellenic Statistical Authority, 2024).

The Thessaloniki Metropolitan Area surrounding landscape includes mountainous, coastal and riparian territories that are highly significant due to their touristic potential (INSETE, 2022). In particular, the nearby Regional Units of Chalkidiki and Pieria are popular 3S destinations, while significant UNESCO World Heritage sites are located in the Regional Units of Thessaloniki, Chalkidiki, Pieria and Imathia (INSETE, 2023). In addition, the neighbouring Axios National Parc wetland ecosystem (Thermaikos Gulf Protected Areas Management Authority, n.d.), member of the protected areas network Natura 2000 (European Environmental Agency, n.d.), serves as both an ecotourism destination (INSETE, 2022) and a filming location for screen productions (Newsroom, 2023).

International flight arrivals reveal the city’s tourism seasonality (Thessaloniki Hotel Association, 2023, INSETE, 2024), whereas hospitality statistics indicate short visits, a rising tendency in MICE tourism and 50–72% occupancy rates (INSETE, 2022, Thessaloniki Hotel Association, 2023). Besides, it is noted that low per capita tourism expenditure presents a challenge for the Region as a whole (INSETE, 2022).

Digital nomads’ self-enumeration in Nomad List (n.d.b) shows a rising trend adding Thessaloniki to their destination agenda between 2016 and 2023, with 550 arrivals and an average stay of 6 days in the latter year. Thessaloniki has been ranked 16th best destination for digital nomads in top 20 world cities (Hamilton, 2021), based on qualities such as gastronomy, friendliness, low cost of living, safety, connectivity reliability and a multitude of remote working - friendly spaces and spots.

2.4. Data Collection

Both qualitative and quantitative methods were used to collect primary data.

Semi-structured interviews were deemed as the appropriate methodological tool to obtain information from local digital nomadism private and public stakeholders. In particular, the managers of the co-working spaces identified in the Metropolitan Area in March 2024, as well as representatives of Thessaloniki Destination Management Organization (DMO), Thessaloniki Tourism Promotion and Marketing Organization were contacted. The interviews were based on two distinct questionnaires, one addressed to the managers of co-working spaces, and the other to the Organizations’ representatives (Tables A.1, A.2). A letter of consent was requested from the interviewees for the publication of collected data. The interviewees were also inquired upon the authorization of disclosure, or not, of their name and affiliation (Nikolaidou, 2025). The interview discussion was allowed to evolve also towards other topics, on an ad hoc basis. The interviews were conducted during the period from 4 to 14 March 2024.

A survey was conducted to collect data regarding the validity test of the criteria included in the proposed methodological tool, as well as on its application to the study area. The sample among digital nomads, regardless of whether they had already visited the case study area or not, was drawn at random, to reduce selection bias (Leuffen, 2007). The questionnaire included both closed and open-ended questions (Table A.3) and was created through Google forms software. It was distributed to twenty digital nomadism communities in social media between 10 and 23 June 2024. Information consent was requested for the processing and publication of anonymous data.

Extensive secondary research was also undertaken, in the context of assessing attractiveness of the pilot study area based on the proposed methodological tool criteria. It included bibliographic research, statistical data collection, and online observation of digital nomads’ feedback in crowdsourced websites. The secondary research methods were applied in an ad hoc manner, in accordance with the specific research needs of each criterion.

2.5. Data Analysis

Mixed techniques were used to analyze the pilot case study, that included both qualitative and quantitative data, as well as information from secondary sources. The small-scale dataset of qualitative data allowed for manual data processing to templates, for categorizing purposes. Using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2021), key insights were extracted regarding potential common and individual themes among the participating stakeholders. Data analysis included the assessment of the methodological tool’s validity, as well as of the importance of each proposed criterion to destination selection. Moreover, quantitative data analysis used numerical tendencies to identify potential destination selection trends.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Destination Selection Criteria

Literature review indicated fifteen criteria of destination selection namely, Cost of living, Connectivity, Mobility/Transport/Infrastructure, Climate & Environment, Digital Nomads Community, Recreation & Culture/English language proficiency, Physical safety, Social safety, Legal DNV context/ low bureaucracy levels, Co-working spaces, Timezone, Accommodation/ hosting preparedness, Happiness Index, Immigrants’ percentage to population, Remote work placements (

Table 1). Ten of these criteria, namely Cost of living, Connectivity, Mobility, Transport and Infrastructure, Climate and Environment, Digital Nomads Community, Recreation, Culture and English Language Proficiency, as well as Physical Safety, appeared in three or more of the publications included in the literature review research (

Table 1). Thirteen of them, namely Cost of living, Connectivity, Mobility/ Transport/ Infrastructure, Climate and Environment, Digital Nomads Community, Recreation and Culture/ English Language Proficiency, Physical Safety, Social Safety, Co-working spaces, Timezone, and Accommodation/ hosting preparedness, were identified in criteria tags for searching destinations in Nomad List and were benchmarked as such for inclusion to the methodological tool.

- (1)

Technitis, 2021, Lee et al., 2019, NordLayer, 2023, Flatio, 2023, UNDP, 2020, Circleloop, n.d.

- (2)

Technitis, 2021, Lee et al., 2019, NordLayer, 2023, UNDP, 2020.

- (3)

Technitis, 2021, Lee et al., 2019, Flatio, 2023, UNDP, 2020.

- (4)

Technitis, 2021, Lee et al., 2019, UNDP, 2020.

- (5)

NordLayer, 2023, Flatio, 2023, UNDP, 2020.

- (6)

UNDP, 2020, Circleloop, n.d.

- (7)

Technitis, 2021, Lee et al., 2019

- (8)

Lee et al., 2019

- (9)

Circleloop, n.d.

Adjunct analysis revealed whether it would be relevant to assign certain criteria, in case different measurement sets were used to quantify their constituting elements. Thus, cybersecurity was recognized as a distinct criterion from connectivity, considering that different indexes are used to measure each attribute. Similarly, English language proficiency among local residents was assessed independently of Culture and Recreation, since it relates to the communication ability and social accessibility of the local community, rather than to entertainment and the cultural offer.

The Happiness Index was further considered as a criterion of destination attractiveness to digital nomads, although it had fallen short of the Nomad List benchmarking. In fact, secondary research results indicate signs of difference. Specifically, highly popular destinations for digital nomads, like Thailand and Sri Lanka (Nomads, 2024, Flatio, 2023), or trending ones, like Albania (Exit Staff, 2021), have low national rankings in the World Happiness Index (Helliwell et al., 2024). Conversely, the top-ranking country in the World Happiness Index, Finland, is not included among the popular destinations for digital nomads. Still, the review of the literature did not support the claim that the hubs of digital nomads are bubbles disconnected from local well-being. It was therefore suggested that further research was required to explore the relationship between destination desirability of digital nomads and life satisfaction levels of local residents.

This led to the introduction of a new criterion, in the generic terms of “additional attractiveness factors”, which might include the Happiness Index, along with other potentially particular local features that could endow each destination with a unique allure.

Accordingly, 15 criteria emerged, namely: Physical Safety, Social Safety, Cost of life, Climate and Environment, Recreation and Culture, Local Community, Expatriate Community, Co-working spaces, Connectivity, Cyber safety, Timezone, National/ regional policy incentives, Hosting Preparedness, Mobility and Transport, and Additional attractiveness factors.

3.2. Methodological Tool

The resulting criteria, which included the overlapping groups of Security, Work, Sociability and Leisure, were set into a Venn diagram. Their diagrammatic placement was related to the human needs that each criterion meets.

Figure 1.

Digital nomads’ criteria for destination selection: Proposed methodological tool. Source: Nikolaidou, 2025.

Figure 1.

Digital nomads’ criteria for destination selection: Proposed methodological tool. Source: Nikolaidou, 2025.

3.3. Pilot Study Outcomes

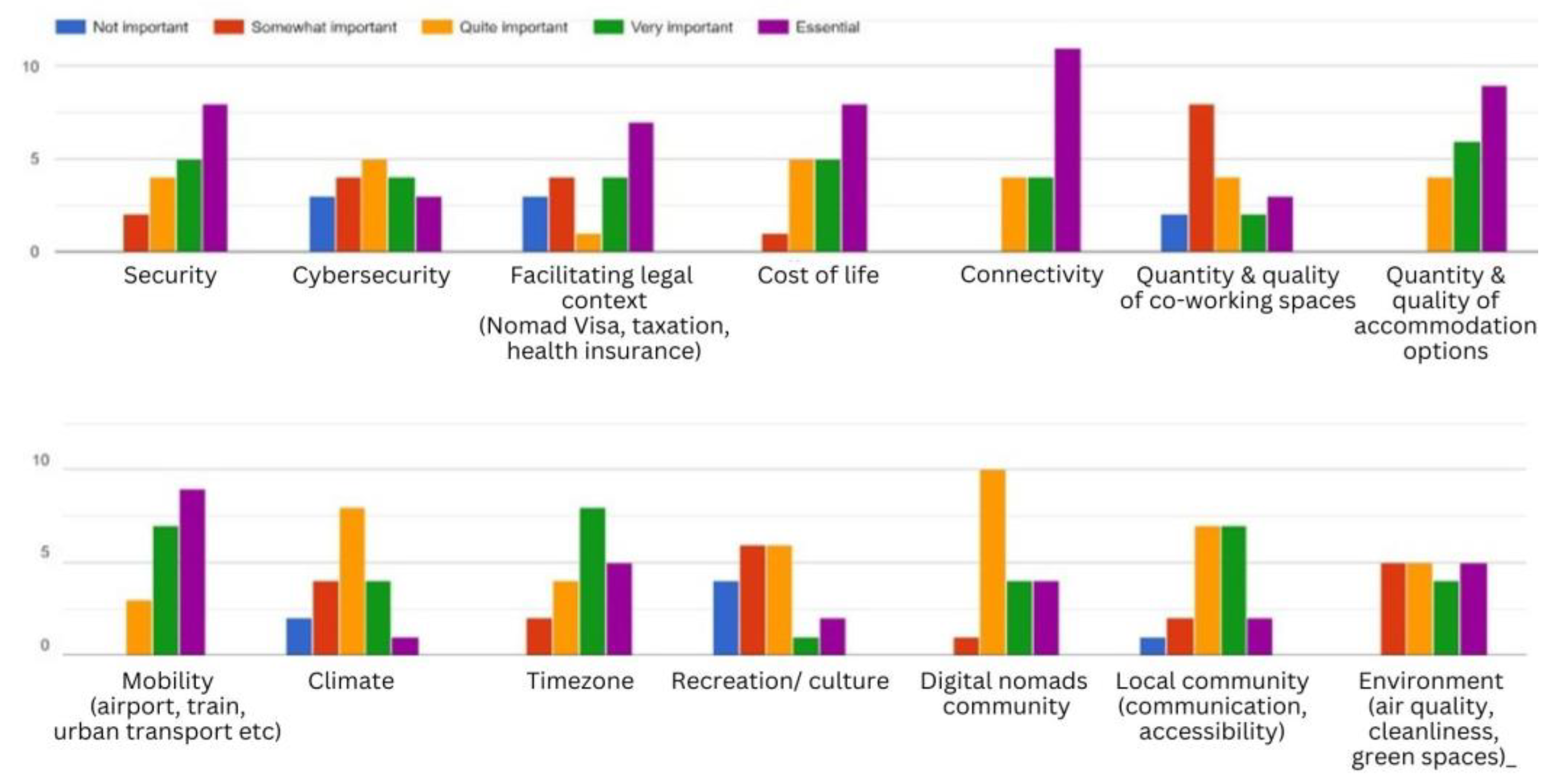

Of the nineteen digital nomads who participated to the survey, 47,4% were from EU/Schengen area member states, while the gender distribution was nearly evenly spread between males and females. Respondents were about equally distributed among Generation X, Millennials and Gen Z, with Millennials having a slight prevalence (38%). The majority of respondents rated as "critical" or “very important” the destinations’ selection criteria of: Security, Facilitating legal context, Cost of life, Connectivity, Accommodation options, Mobility and Timezone. Little importance was attributed to Co-working spaces, whereas Climate, Recreation and Culture, as well as Digital nomads’ community were viewed as of moderate importance. No significant trends were recorded as regards Cybersecurity and Environment (

Figure 2).

In the open-end question about additional factors that may impact their choice of destination, sparce responses mention social safety for women and socially vulnerable groups, emphasizing that social security was not distinguished from physical security in the questionnaire, gastronomy, shipping efficiency and the absence of duty taxes for the delivery of online orders, as well as the existence of co-living spaces at the destination.

Blogs and Social Media, as well as Word of mouth and Reviews accounting for 42,1% respectively, prevailed as the major sources of information and influence on destination selection. The typical duration of stay at a destination was one to three months for 47,4% of respondents, whereas 26,3% responded that they stay for up to a month. However, 78,9% confirmed that duration of stay is flexible, depending upon the level of satisfaction from the destination.

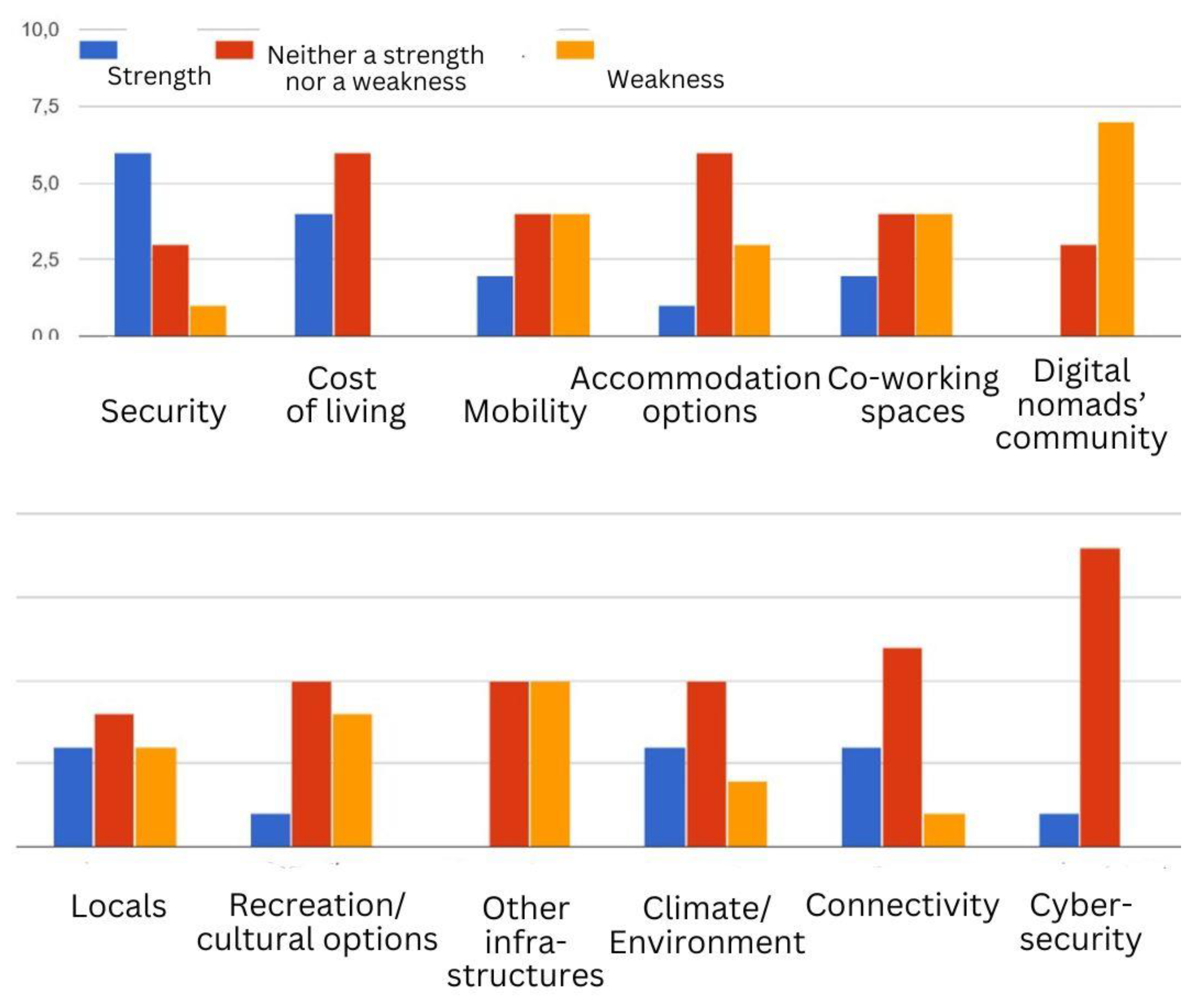

As regards the case of Thessaloniki, responses indicated that security is the city’s strongest point. The destination did not offer strong competitive advantages for participants in the areas of Cost of living, Accommodation options, Climate/ Environment, Connectivity and Cybersecurity. In addition, responses presented stronger negative trends in the areas of Mobility, Co-working spaces, Digital nomads’ community, as well as Recreational/Cultural options. Interaction with the locals revealed opinions that were widely spread among positive, neutral and negative responses (

Figure 3). Open-end responses by 40% of participants who had already visited the destination, indicated bureaucratic complexities, non-user-friendly transportation services for accessing nearby 3S holidays destinations, the weak presence of a digital nomad community and expats networking. Nonetheless, 84% of participants who had not yet visited Thessaloniki, were positive with adding the destination to their list of places for future travel. The stated motivations were the desire to discover the destination, its environment, climate, gastronomy, culture, waterfront and leisure ambiance. On the other hand, the main deterrents to visit the city included the lack of direct flights to international destinations, lack of an expats community and the cost of living. Overall, 40% of participants who had visited the city, rated Thessaloniki with 4 out of 5, 30% of visiting participants with 2 out of 5, 20% with 3 out of 5 and 10% with 1 out of 5, whereas no participant rated the destination with 5 out of 5.

Interviews with managers of co-working spaces in Thessaloniki (

Table 2) denote a low but increasing number of digital nomads yearly, mostly Millennials, with a nationality that is more common among Eastern European countries. As already mentioned, the typical length of stay, is significantly shorter than the average length indicated in the survey, as well as in previous relevant large-scale research (Flatio, 2023). There are only a few expats networking activities. Mobility is also pointed out as a weakness, as seen by digital nomads themselves. However, the responses from local co-working spaces highlight as strengths certain aspects of the city that digital nomads themselves in the survey find rather normal and conventional, or even negative, namely, connectivity, the sociability of residents, accommodation and cost of living. Moreover, the managers’ responses regarding the lack of flexibility in stay duration among digital nomads, are not compatible with the survey’s findings, which indicated that contentment with the destination was a key determinant of the length of stay.

The interview with the Thessaloniki DMO representative (

Table 3) revealed that their destination marketing strategy has already addressed digital nomads in relevant ways, such as fam trips encouraging influencer marketing. This is in light of the fact that blogs and social media are major information sources for the target group, as indicated in the survey. On the other hand, according to the literature review, digital nomads are viewed as a type of traveler that stays longer at the destination, without taking into account the city’s unique characteristics, which emphasize brief visits. However, the short stay of digital nomads is consistent with the DMO’s overall destination marketing strategy, which promotes Thessaloniki rather as a short stay destination (city break, MICE, layover for 3S destinations, cruise homeporting).

4. Discussion

Research findings indicate that the hypothesis regarding the working criteria of destination attractiveness may be pertinent to the needs of digital nomads. However, all criteria do not bear the same weight when choosing destinations. This may occasionally be related to specific situations. For example, national policies regarding Digital Nomad Visa apply only to non-EU nationals, and in destinations located in EU member states. In the case of Greece, these policies impose a minimum monthly income of 3,500 euros, thereby excluding a significant segment of the digital nomad community (Flatio, 2023). Nonetheless, the survey findings regarding the relative importance of each criterion importance do not align with the frequency that the criteria appear in the literature review. Additionally, considering the rather small survey size, that constitutes a research limitation, it would be beneficial to further investigate the relative importance of each criterion in order to adjust the methodological tool accordingly.

Moreover, the pilot application in the case study of Thessaloniki demonstrated that not all criteria can be assessed at the local level in a vacuum, because some of them may be related to national policies, regional geographic conditions or local socioeconomic factors. In particular, the laws governing Digital Nomad Visa, health insurance and taxation policies are implemented uniformly throughout Greece, while Time zone is also uniform at country level. Additionally, it is typically easier to retrieve data at the national or regional level than at the local level when it comes to criteria that are measured by complex indexes, such as Connectivity and Cybersecurity. Furthermore, cost of living is affected by national and regional factors, such as nationally uniform telecommunication and electricity prices, whereas Climate is directly related to the region’s geographic location. Therefore, national and regional factors substantially impact the local capacity to attract digital nomads.

It is also worth noting that, as indicated by the survey findings, in the case of Thessaloniki the flexibility of stay duration in relation to satisfaction from the destination, was not considered by local stakeholders, probably due to limited information, or pre-conceived perceptions. Nevertheless, it is a crucial consideration when developing marketing strategies that address digital nomads, especially when it comes to destinations which are not consolidated yet, like the case of Thessaloniki.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.N. and S.K.; methodology, C.A.N. and S.K.; validation, C.A.N.; formal analysis, C.A.N.; investigation, C.A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.N; writing—review and editing, S.K.; supervision, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3S |

Sun, Sea and Sand |

| DMO |

Destination Management Organization |

| EU |

European Union |

| INSETE |

Institute of the Greek Tourism Confederation |

| MICE |

Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Exhibitions |

| UNDP |

United Nations Development Programme |

| U.S. |

United States |

| UNWTO |

United Nations World Tourism Organization |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire addressed to co-working spaces’ managers.

Table A1.

Questionnaire addressed to co-working spaces’ managers.

| On an annual basis, how many of your clients are digital nomads? (= permanent residents to other countries, temporarily residing in Thessaloniki and working remotely as independent contractors or employees for foreign-registered clients. Short stay tourists visiting the city are excepted). |

| Which is the average duration of stay for digital nomads to rent a hot/ dedicated desk in your co-working space? |

| Do they have any common demographic characteristics? (eg. gender, nationality, age). |

| Do you organize activities which encourage them to interact with one another? |

| Do you offer recommendations for recreational/cultural events in the city? If yes, does this happen upon their request or on your own initiative? |

| Do you consider that their flexible duration of stay depends on their overall satisfaction level from the destination (Thessaloniki), or is it fixed? |

| Which are, in your opinion, the strong and weak points of Thessaloniki as a digital nomad destination?(Indicative discussion topics: urban public infrastructure, social context, tourism infrastructure, touristic product). |

Table A2.

Questionnaire addressed to Thessaloniki’s DMO.

Table A2.

Questionnaire addressed to Thessaloniki’s DMO.

| Please state (a) the unique features of Thessaloniki that form the basis of the city’s tourism promotion strategy, and (b) the main target groups that the Organization and/ or in collaboration with other stakeholders are working to reach. |

| Have you recorded the current situation of digital nomads visiting Thessaloniki, as a tourism market segment? |

| Is there a strategy applied to attract this segment, or are there relevant plans? |

Table A3.

Questionnaire addressed to digital nomads.

Table A3.

Questionnaire addressed to digital nomads.

| Please state your age group: 18-31. 32-43, 44-61, over 61 |

| Please state the continent you come from: EU member state, Europe-non EU, Americas, Asia, Africa, Oceania |

| Please state your gender: male, female, non-binary, rather not answer |

| What is your monthly income? Below 3,500 euros/over 3,500 euros |

| Which information source has the biggest impact on your destinations choice? Nomad List, Press, Blogs and Social Media, Word of mouth/reviews, Other.If you choose “Other”, please provide further information |

| How long do you usually stay at a destination? A few days to a month, one to three months, three to eighteen months, over eighteen months. |

| Is the length of your stay fixed or you may stay longer at a destination, depending on your satisfaction level? Fixed / Flexible |

| Please rate, depending on their significance (1= not significant at all to 5 = very significant), the following factors of destination attractiveness: Physical safety, Cybersecurity, Facilitating legal context (Digital Nomads Visa, taxation legislation, health security), Cost of living, Connectivity, Number and quality of co-working spaces, Number and quality of accommodation options, Mobility (airport, train, road network, public transport etc), Climate, Time zone, Recreation and cultural offer, Digital nomads community, Communication with locals (language), Friendliness and social accessibility, Environment (pollution levels, green spaces, cleanliness etc).Please add any other significant factors, or comment on the aforementioned? |

| Have you already visited Thessaloniki? Yes/ No |

| If yes, what was your overall satisfaction level from the destination? Rating from 1 (totally dissatisfied) to 5 (entirely satisfied). |

| If yes, which are the destination’s strongest and weakest points?Strength/Neither a strength nor a weakness/ WeaknessPhysical safety, Cost of living, Co-working spaces, Digital nomads community, Local community, Recreation and cultural offer, Infrastructure, Environment, Connectivity, Cybersecurity.Would you like to provide any additional feedback? |

| If you haven’t visited Thessaloniki yet, do you plan to include the destination in your to-visit agenda?Yes/ No |

| For which reasons? |

References

- Ahlberg, E. (2021). The Development of the Digital Nomad During the Course of the Pandemic. [Master Thesis in Media and Communication, Malmö University]. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1596331/FULLTEXT02.

- Bennett, D. (2015). Origins of the Venn Diagram. In M. Zack & E. Landry (eds) Research in History and Philosophy of Mathematics. The CSHPM 2014 Annual Meeting in St. Catharines, Ontario. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis. A practical guide. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97–116. [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. (2022). Tourism Management and Marketing in Transformation. In D. Buhalis, (ed), Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing. Elgar Publishing.

- Chevtaeva, E. , & Guillet, B. D. (2021). Digital nomads’ lifestyles and coworkation. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 21,. [CrossRef]

- Circleloop. (n.d.). The digital nomad index. Available online: https://www.circleloop.com/nomadindex/?utm_source=blog&utm_medium=blog&utm_campaign=digitalnomad (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Cohen, S. A. , & Gössling, S. (2015). A darker side of hypermobility. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 47. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. A. , Prayag, G., & Moital, M. (2013). Consumer behaviour in tourism: Concepts, influences and opportunities. Current Issues in Tourism, 17. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. (1979). A phenomenology of tourist experiences. Sociology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Cook, D. (2020). The freedom trap: digital nomads and the use of disciplining practices to manage work/leisure boundaries. Information Technology & Tourism, 22. [CrossRef]

- Cook, D. (2023). What is a digital nomad? Definition and taxonomy in the era of mainstream remote work. World Leisure Journal, 65. [CrossRef]

- Dupeyras, A. , & MacCallum, N. (2013). Indicators for measuring Competitiveness in Tourism. A guidance document. [Policy paper]. OECD Tourism Papers. [CrossRef]

- Ehn, K. , Jorge, A., & Marques-Pita, M. (2022). Digital Nomads and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Narratives about relocation in a time of lockdowns and reduced mobility. Social Media + Society, 8. [CrossRef]

- European Environmental Agency (n.d.). Natura 2000 viewer. European Commission. Available online: https://natura2000.eea.europa.eu/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Eurostat (n.d.). Statistical Atlas NUTS and territorial typologies. European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/statistical-atlas/viewer/?config=typologies.json& (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Exit Staff (2021, March 6). World Happiness Report: Albanians Are Least Happiest in the Western Balkans. Exit News. Available online: https://exit.al/en/world-happiness-report-albanians-are-least-happiest-in-the-western-balkans/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Fidel, R. (1984). The case study method: A case study. Library and Information Science Research, 6(3), 273-288.

- Flatio. (2023). Digital Nomad Report 2023. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1EKD_yXe2oQM-jwm3KGaQ03DZmEPZa-hL/view (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Gearing, C. E., Swart, W. W., & Var, T. (1974). Establishing a measure of touristic attractiveness. Journal of Travel Research, 12(4), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Hannonen, O. (2020). In search of a digital nomad: defining the phenomenon. Information Technology & Tourism, 22. [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority (2023). ELSTAT 2021 Population and Housing Census Results. Hellenic Statistical Authority. Hellenic Republic. (in Greek). Available online: https://elstat-outsourcers.statistics.gr/Census2022_GR.pdf.

- Hellenic Statistical Authority (2024, 31 January). Regional Accounts: Gross Added Value for year 2021 and revised data for years 2019-2020. [Press release], (in Greek). [Hellenic Statistical Authority. Hellenic Republic. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/documents/20181/45150b28-634a-e7f5-374b-ba3dbc67d402.

- Helliwell, J.F., Layard, R., Sachs, J.D., De Neve, J.E., Aknin, L.B., Wang, S., Paculor, S. (2023). World Happiness Report 2023. Available online: https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2023/executive-summary/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Holleran, M. , & Notting, M. (2023). Mobility guilt: digital nomads and COVID-19. Tourism Geographies, 25. [CrossRef]

- Holleran, M. (2022). Pandemics and geoarbitrage: digital nomadism before and after COVID-19. City, 26. [CrossRef]

- INSETE (2022). Annual Report on Competitiveness and structural adjustment in Tourism sector for year 2021 – Central Macedonia Region. SETE Intelligence. Institute of the Greek Tourism Confederation (in Greek). Accessed on 23 December. 2023.

- INSETE (2023). Annual Report on Competitiveness and structural adjustment in Tourism sector for year 2022 – Central Macedonia Region. SETE Intelligence. Institute of the Greek Tourism Confederation (in Greek). Available online: https://insete.gr/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/23-12_Central_Macedonia.pdf.

- INSETE (2024, June). Statistical data Bulletin Nr 93. SETE Intelligence. Institute of the Greek Tourism Confederation (in Greek). Available online: https://insete.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Bulletin_2406-1.pdf.

- Kostopoulou, S. , Lefaki, S., Kyriakou, D. Sofianou, E., Papadopoulou, P. (2023) Thessaloniki on the Silk Road. Exhibition Tourism at Thessaloniki International Fair. In Stella Kostopoulou, Gricelda Herrera-Franco, Jacob Wood, Kheir Al-Kodmany (editors) “Cities’ Vocabularies and the Sustainable development of the Silk Roads”, ASTI- Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation Book Series By Springer, ISBN 978-3-031-31026-3, pp. 283-312. [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis. An introduction to its methodology. University of Pennsylvania. Sage Publications.

- Lee, A., Toombs, A. L., Erickson, I., Nemer, D., Ho, Y., Jo, E., & Guo, Z. (2019). The social infrastructure of co-spaces: Home, Work and Sociable Places for Digital Nomads. [Paper]. ACM on Human-computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 1–23. November 2019. [CrossRef]

- Leuffen, D. (2007). Case Selection and Selection Bias in Small-n Research. In T. Gschwend & F. Schim-melfennig (eds), Research Design in Political Science. Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Maggopoulos, G. (2014). Case study as research strategy in programme evaluation: theoretical reflections. Social Studies Platform, 16 (64) (in Greek). Available online: https://journals.lib.uth.gr/index.php/tovima/article/view/397/377.

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harpers.

- Mershon, C., & Shvetsova, O. (2019). Formal modeling in social science. University of Michigan Press. [CrossRef]

- Metropolitan Thessaloniki (n.d.). Intervention Area. Metropolitan Thessaloniki – Central Macedonia Region (in Greek). Available online: https://thma.gov.gr/perioxi-paremvasis/ (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Miguel, C. , Lutz, C., Majetić, F., & Perez-Vega, R. (2023). Working from paradise? An analysis of the representation of digital nomads’ values and lifestyle on Instagram. New Media & Society, 0. [CrossRef]

- Newsroom (2023, 23 November). Thessaloniki: 2024, a milestone year for cruise]. The Power Game (in Greek). Available online: https://www.powergame.gr/navtilia/552937/thessaloniki-xronia-orosimo-gia-tin-krouaziera-to-2024/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Nikolaidou, C.A. (2025). Digital Nomads and Touristic Development: destination attractiveness of Thessaloniki. [Master Thesis in Tourism and Local Development, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki] (in Greek). [CrossRef]

- Nomad List (n.d.a). Go nomad. Available online: https://nomadlist.com/ (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Nomad List, (n.d.b). Thessaloniki, Greece. Available online: https://nomadlist.com/thessaloniki (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Nomads (2024). The 2024 state of Digital Nomads. Available online: https://nomads.com/digital-nomad-statistics?ref=isabelleroughol.com (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Nord Layer (2023). Global Remote Work Index 2023. Available online: https://nordlayer.com/global-remote-work-index/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Official Journal of Greece (2010, 7 June). New Structure of Local Government and Decentralized Government – Programme Kallikratis. Hellenic Republic (in Greek). Available online: https://www.ypes.gr/UserFiles/f0ff9297-f516-40ff-a70e-eca84e2ec9b9/nomos_kallikrati_9_6_2010.pdf.

- Poulaki, I. , Mavragani, E., Kaziani, A., & Chatzimichali, E. (2023). Digital Nomads: Advances in hospitality and destination attractiveness. Tourism and Hospitality, 4. [CrossRef]

- Raimkulov, M. , Juraturgunov, H., & Ahn, Y. (2021). Destination attractiveness and memorable travel experiences in silk road tourism in Uzbekistan. Sustainability, 13(4), 2252. [CrossRef]

- Reichenberger, I. (2017). Digital nomads – a quest for holistic freedom in work and leisure. Annals of Leisure Research, 21. [CrossRef]

- Reitsamer, B. F. , Brunner-Sperdin, A., & Stokburger-Sauer, N. (2016). Destination attractiveness and destination attachment: The mediating role of tourists’ attitude. Tourism Management Perspectives, 19,. [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. (2015). The new global nomads: Youth travel in a globalizing world. Tourism Recreation Research, 40. [CrossRef]

- Richter, S. , & Richter, A. (2019). Digital nomads. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 62. [CrossRef]

- Technitis, E.; (2021, June 24). 7 Layers' Methodology for Digital Nomads' Destinations: Part 1. Digital Nomads Observatory. Available online: https://digitalnomadsobs.org/2021/03/28/7-layers-methodology-for-digital-nomads-destinations-part-1/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Thermaikos Gulf Protected Areas Management Authority (n.d). National Park. Protected area. Thermaikos Gulf Protected Areas Management Authority (in Greek). Available online: https://axiosdelta.gr/%ce%b5%ce%b8%ce%bd%ce%b9%ce%ba%cf%8c-%cf%80%ce%ac%cf%81%ce%ba%ce%bf/%cf%80%cf%81%ce%bf%cf%83%cf%84%ce%b1%cf%84%ce%b5%cf%85%cf%8c%ce%bc%ce%b5%ce%bd%ce%b7-%cf%80%ce%b5%cf%81%ce%b9%ce%bf%cf%87%ce%ae/ (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Thessaloniki Hotels Association (2023). Tourists Profile and Satisfaction. Thessaloniki Hotels Renderance. GBR Consulting. Thessaloniki Hoteliers Union (in Greek). Available online: https://thessalonikihotels.travel/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/erevna-ikanopoiisis-touriston-maios2023.pdf.

- Thompson, B. Y. (2018). Digital Nomads Employment in the online gig economy. Glocalism: Journal of Culture, Politics and Innovation, (1). [CrossRef]

- Ul, I. , & Chaudhary, M. (2021). Index of destination attractiveness: A quantitative approach for measuring tourism attractiveness. Turizam, 25. [CrossRef]

- UNWTO (2023). Digital Nomad Visas. [Brief]. World Tourism Organization. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (2020). Digital Nomad Scanner. Who are the location-independent professionals that choose Belgrade?, United Nations Development Programme Serbia. Digital Serbia Initiative. Available online: https://www.undp.org/serbia/publications/digital-nomads-scanner (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Van den Broek, T., Feiten Haubrich, G., Murero, M., Marx, J., Lind, Y., Brakel-Ahmed, F., Cook, L., Boer, P., Razmerita, L. (2024). Digital Nomads. Opportunities and Challenges for the Future of Work in the Post-Covid Society. Aurora. Network Institute. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380531487_Digital_Nomads (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Yousaf, A. , Amin, I., & Santos, J. a. C. (2018). Tourists’ Motivations to Travel: a Theoretical Perspective on the Existing Literature. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 24. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).