Submitted:

20 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Subject and Methods

3. Results

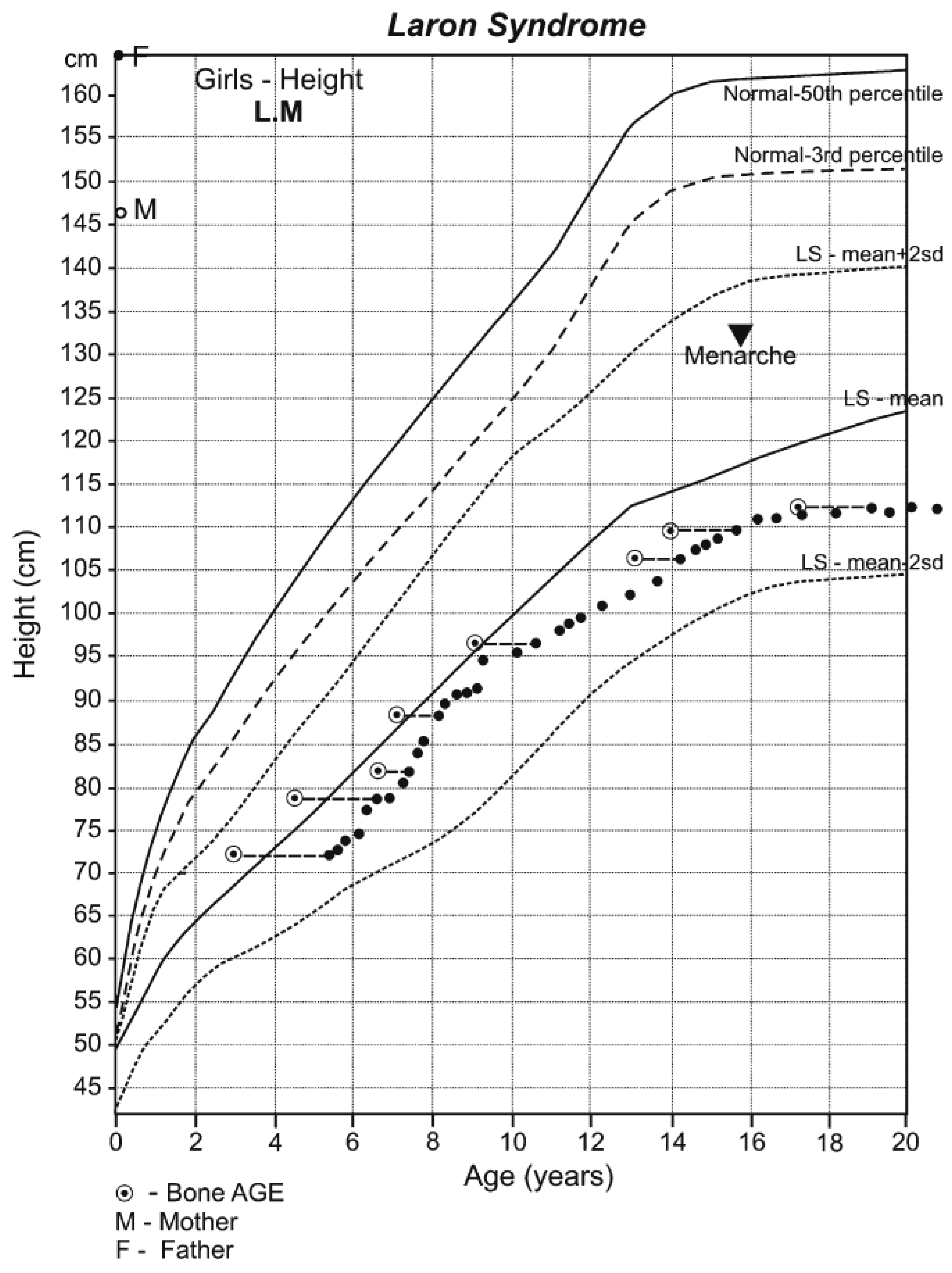

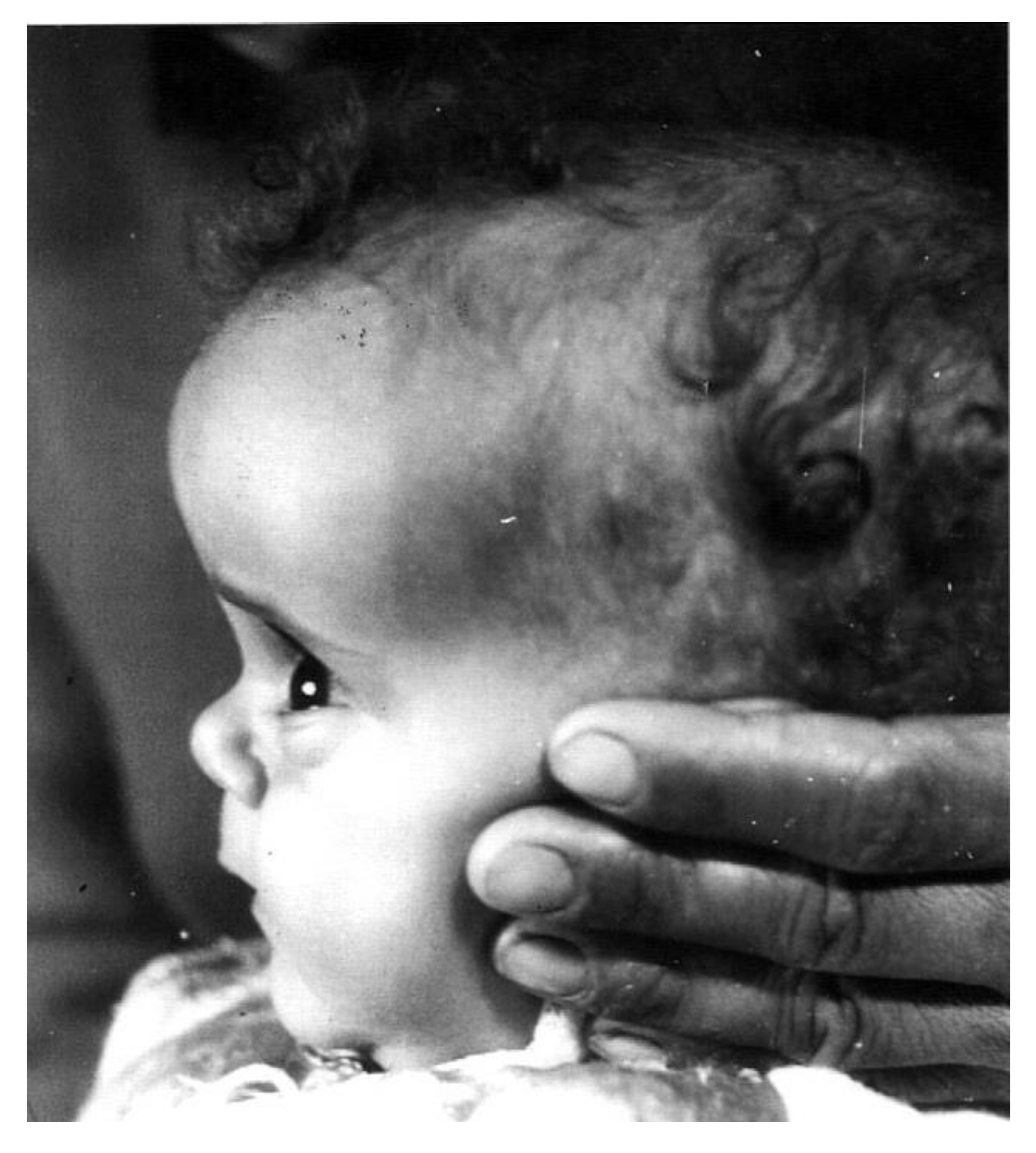

3.1. Growth and Development

3.2. School Age

3.3. Sexual Development and Puberty

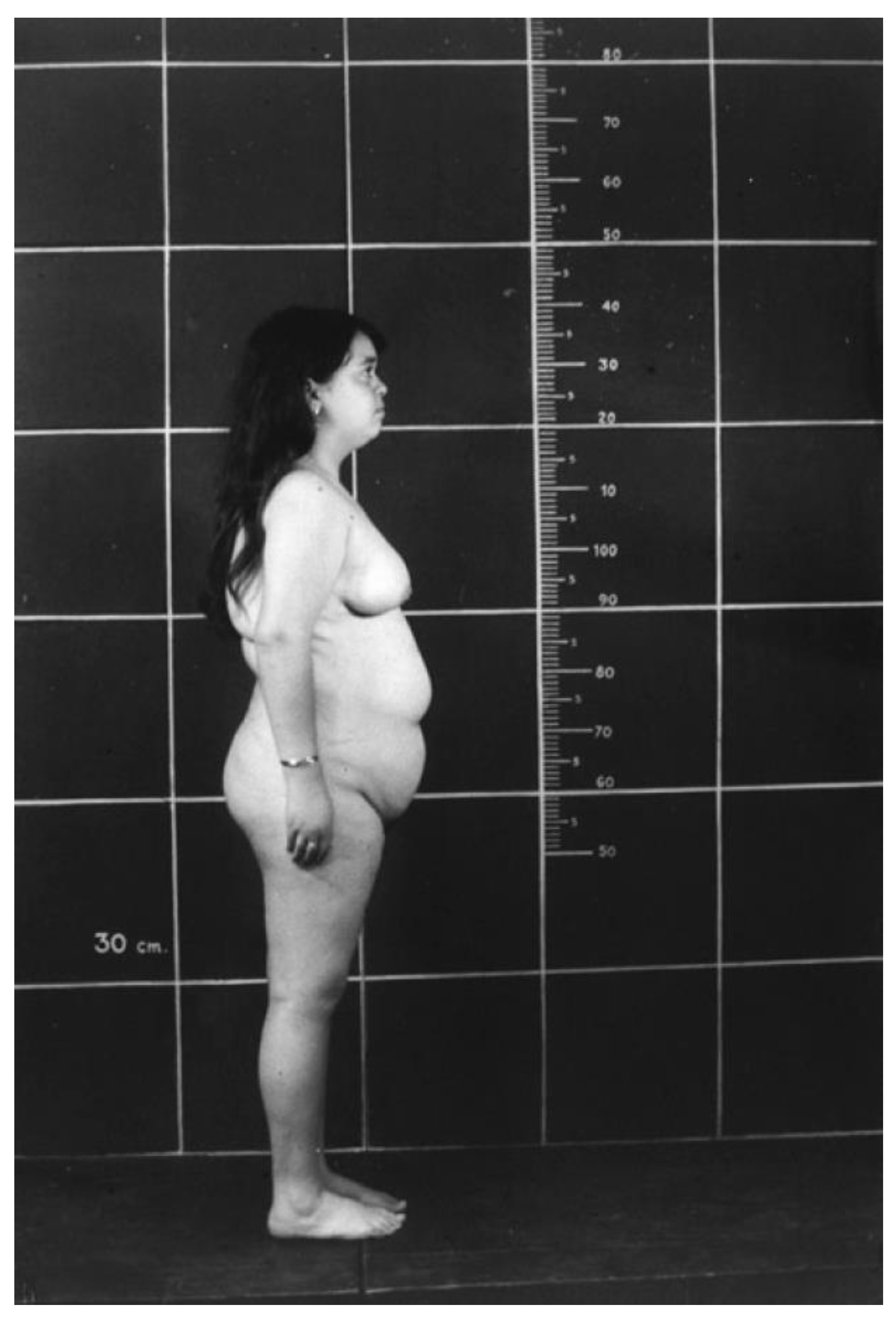

3.4. Adult Life

3.5. Limitation in Mobility

3.6. Neurological Abnormalities

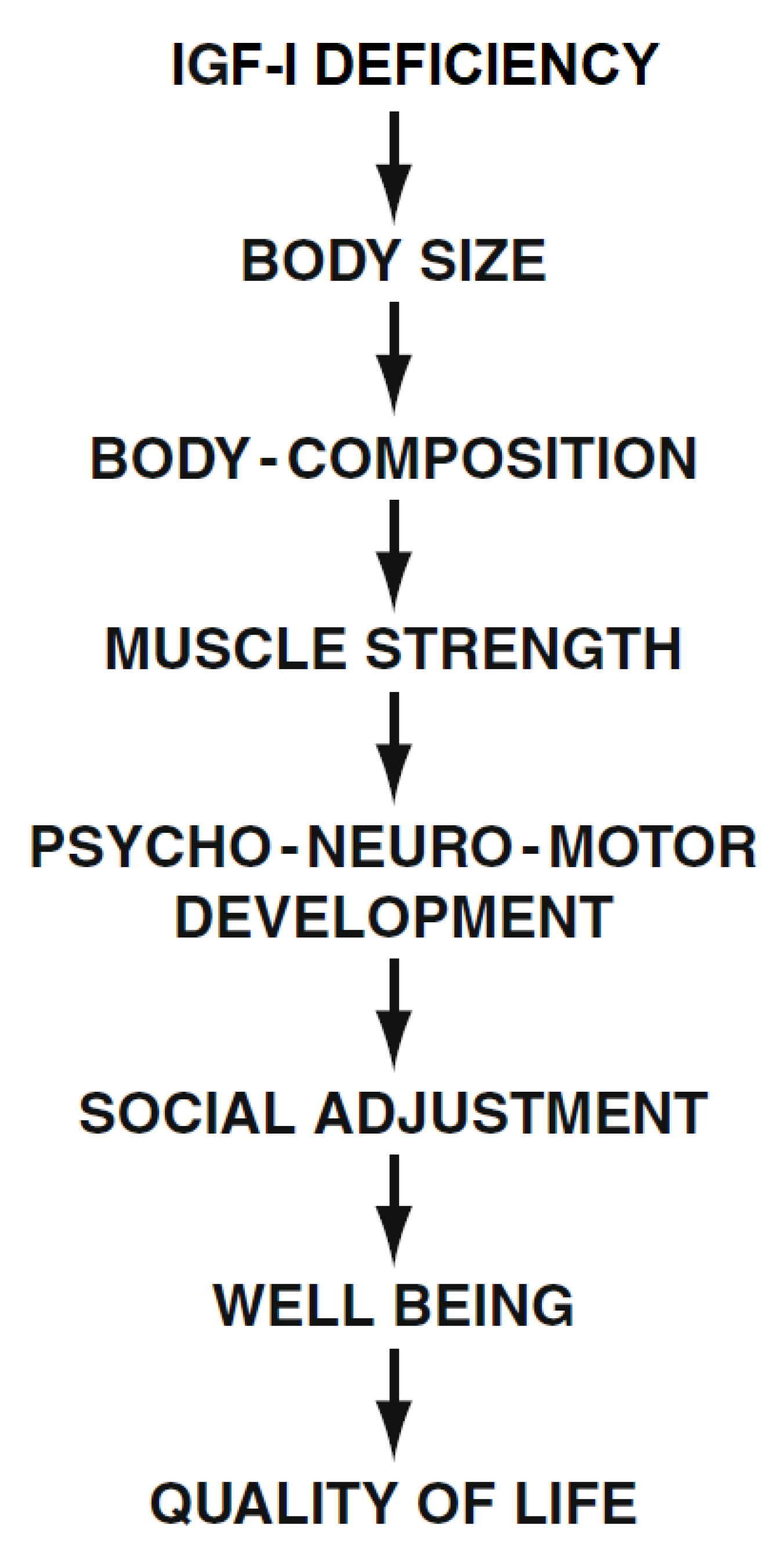

3.7. Psycho-Social Aspects

3.8. Treatment

4. Discussion

Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

References

- Laron, Z.; Werner, H. Laron syndrome - A historical perspective. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2021, 22, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Mannheimer, S. Measurement of human growth hormone. Description of the method and its clinical applications. Isr J Med Sci. 1966, 2, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Pertzelan, A.; Karp, M. Pituitary dwarfism with high serum levels of growth hormone. Isr J Med Sci. 1968, 4, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosenbloom, A.L.; Guevara-Aguirre, J.; Rosenfeld, R.G.; Fielder, P.J. The little women of Loja: growth hormone receptor-deficiency in an inbred population of southern Ecuador. N Engl J Med. 1990, 323, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, R.G.; Rosenbloom, A.L.; Guevara-Aguirre, J. Growth hormone (GH) insensitivity due to primary GH receptor deficiency. Endocr Rev. 1994, 15, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z. Deficiencies of growth hormone and somatomedins in man. Spec Top Endocrinol Metab. 1983, 5, 149–199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daughaday, W.H.; Laron, Z.; Pertzelan, A.; Heins, J.N. Defective sulfation factor generation: a possible etiological link in dwarfism. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1969, 82, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Pertzelan, A.; Karp, M.; Kowadlo-Silbergeld, A.; Daughaday, W.H. Administration of growth hormone to patients with familial dwarfism with high plasma immunoreactive growth hormone. Measurement of sulfation factor, metabolic, and linear growth responses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1971, 33, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Kowadlo-Silbergeld, A.; Eshet, R.; Pertzelan, A. Growth hormone resistance. Ann Clin Res. 1980, 12, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z. Laron syndrome (primary growth hormone resistance or insensitivity): the personal experience 1958-2003. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 89, 1031–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshet, R.; Laron, Z.; Pertzelan, A.; Dintzman, M. Defect of human growth hormone in the liver of two patients with Laron type dwarfism. Isr J Med Sci. 1984, 20, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Godowski, P.J.; Leung, D.W.; Meacham, L.R.; Galgani, J.P.; Hellmiss, R.; Keret, R.; Rotwein, P.S.; Parks, J.S.; Laron, Z.; Wood, W.I. Characterization of the human growth hormone receptor gene and demonstration of a partial gene deletion in two patients with Laron type dwarfism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989, 86, 8083–8087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amselem S, Duquesnoy P, Attree O, Novelli G, Bousnina S, Postel-Vinay MC, Goosens M. Laron dwarfism and mutations of the growth hormonereceptor gene. N Engl J Med. 1989, 321, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevah, O.; Laron, Z. Genetic Aspects. In Laron Syndrome - From Man to Mouse; Laron, Z., Kopchick , J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, A.; Josefsberg, Z.; Pertzelan, A.; Zadik, Z.; Chemke, J.M.; Laron, Z. Occurrence of four types of growth hormone related dwarfism in Israeli communities. Eur J Pediatr. 1981, 137, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershkovitz, I.; Kornreich, L.; Laron, Z. Comparative skeletal features between Homo floresiensis and patients with primary growth hormone insensitivity (Laron Syndrome). Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007, 134, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Kauli, R. Fifty seven years of follow-up of the Israeli cohort of Laron Syndrome patients-From discovery to treatment. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2016, 28, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Kauli, R. Linear growth pattern of untreated Laron syndrome patients. In Laron Syndrome - From Man to Mouse; Laron, Z., Kopchick , J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Laron, Z.; Iluz, M.; Kauli, R. Head circumference in untreated and IGF-I treated patients with Laron syndrome: comparison with untreated and hGH-treated children with isolated growth hormone deficiency. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2012, 22, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharf, A.; Laron, Z. Skull changes in pituitary dwarfism and the syndrome of familial dwarfism with high plasma immunoreactive growth hormone--a Roentgenologic study. Horm Metab Res. 1972, 4, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konfino, R.; Pertzelan, A.; Laron, Z. Cephalometric measurements of familial dwarfism and high plasma immunoreactive growth hormone. Am J Orthod. 1975, 68, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konen, O.; Silbergeld, A.; Lilos, P.; et al. Hand size and growth in untreated and IGF-I treated patients with Laron syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2009, 22, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silbergeld, A.; Lilos, P.; Laron, Z. Foot length before and during insulin-like growth factor-I treatment of children with Laron syndrome compared to human growth hormone treatment of children with isolated growth hormone deficiency. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 20, 1325–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shurka, E.; Laron, Z. Adjustment and rehabilitation problems of children and adolescents with growth retardation. I. Familial dwarfism with high plasma immunoreactive human growth hormone. Isr J Med Sci. 1975, 11, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bourla, D.H.; Laron, Z.; Snir, M.; Lilos, P.; Weinberger, D.; Axer-Siegel, R. Insulinlike growth factor I affects ocular development: a study of untreated and treated patients with Laron syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2006, 113, 1197.e1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornreich, L.; Konen, O.; Lilos, P.; Laron, Z. The globe and orbit in Laron syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011, 32, 1560–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellström, A.; Carlsson, B.; Niklasson, A.; Segnestam, K.; Boguszewski, M.; de Lacerda, L.; Savage, M.; Svensson, E.; Smith, L.; Weinberger, D.; Albertsson Wikland, K.; Laron, Z. IGF-I is critical for normal vascularization of the human retina. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 87, 3413–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attias, J.; Zarchi, O.; Nageris, B.I.; Laron, Z. Cochlear hearing loss in patients with Laron syndrome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 269, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z. The Teeth in Patients with Laron Syndrome. In Laron Syndrome - From Man to Mouse; Laron, Z., Kopchick , J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Laron, Z. Laron-type dwarfism (hereditary somatomedin deficiency): a review. Adv Int Med. 1984, 51, 117–150. [Google Scholar]

- Barazani, C.; Werner, H.; Laron, Z. Changes in plasma amino acids metabolites, caused by long-term IGF-I deficiency, are reversed by IGF-I treatment - A pilot study. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2020, 52, 101312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klinger, B.; Jensen, L.T.; Silbergeld, A.; Laron, Z. Insulin-like growth factor-I raises serum procollagen levels in children and adults with Laron syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1996, 45, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brat, O.; Ziv, I.; Klinger, B.; Avraham, M.; Laron, Z. Muscle force and endurance in untreated and human growth hormone or insulin-like growth factor-I-treated patients with growth hormone deficiency or Laron syndrome. Horm Res. 1997, 47, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, Y.; Hadid, A.; Laron, Z.; Moran, D.S.; Vaisman, N. Muscle–Bone Relationship in Patients with Laron Syndrome. In Laron Syndrome - From Man to Mouse; Laron, Z., Kopchick , J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Laron, Z.; Klinger, B. Effect of insulin-like growth factor-I treatment on serum androgens and testicular and penile size in males with Laron syndrome (primary growth hormone resistance). Eur J Endocrinol. 1998, 138, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z. Development and biological function of the female gonads and genitalia in IGF-I deficiency -- Laron syndrome as a model. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2006, 3 Suppl 1, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Kauli, R. Sexual Development in Patients with Laron Syndrome. In Laron Syndrome - From Man to Mouse; Laron, Z., Kopchick , J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Laron, Z.; Sarel, R.; Pertzelan, A. Puberty in Laron type dwarfism. Eur J Pediatr. 1980, 134, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Klinger, B. Body fat in Laron syndrome patients: effect of insulin-like growth factor I treatment. Horm Res. 1993, 40, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg, S.; Laron, Z.; Bed, M.A.; Vaisman, N. The obesity of patients with Laron Syndrome is not associated with excessive nutritional intake. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2009, 3, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Kauli, R.; Silbergeld, A. Adult patients with Laron syndrome tend to develop the metabolic syndrome. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2024, 78, 101605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Kauli, R. Orthopedic Problems in Laron Syndrome. In Laron Syndrome - From Man to Mouse; Laron, Z., Kopchick , J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 323–324. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dov, I.; Gaides, M.; Scheinowitz, M.; Wagner, R.; Laron, Z. Reduced exercise capacity in untreated adults with primary growth hormone resistance (Laron syndrome). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2003, 59, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornreich, L.; Horev, G.; Schwarz, M.; Karmazyn, B.; Laron, Z. Craniofacial and brain abnormalities in Laron syndrome (primary growth hormone insensitivity). Eur J Endocrinol. 2002, 146, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornreich, L.; Horev, G.; Schwarz, M.; Karmazyn, B.; Laron, Z. Laron syndrome abnormalities: spinal stenosis, os odontoideum, degenerative changes of the atlanto-odontoid joint, and small oropharynx. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002, 23, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kornreich, L.; Laron, Z. An unusual brain lesion in a patient with Laron Syndrome. Endocrine. 2024, 84, 1266–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castilla-Cortazar, I.; Femat-Roldán, G.; Rodríguez-Rivera, J.; Aguirre, G.A.; García-Magariño, M.; Martín-Estal, I.; Espinosa, L.; Díaz-Olachea, C. Mexican case report of a never-treated Laron syndrome patient evolving to metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and stroke. Clin Case Rep. 2017, 5, 1852–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, L.; Laron, Z.; Kornreich, L.; Scheuerman, O.; Goldberg-Stern, H.; Kraus, D. Focal Epilepsy in Individuals with Laron Syndrome. Horm Res Paediatr. 2022, 95, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagan, Y.; Abadi, J.; Lifschitz, A.; Laron, Z. Severe obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome in an adult patient with Laron syndrome. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2001, 11, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Kauli, R.; Rosenzweig, E. Sleep and Sleep Disorders in Patients with Laron Syndrome. In Laron Syndrome - From Man to Mouse; Laron, Z., Kopchick , J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, J.J.; Laron, Z. Psychological aspects of pituitary insufficiency in children and adolescents with special reference to growth hormone. Isr J Med Sci. 1968, 4, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z. Psychological Aspects in Patients with Laron Syndrome. In Laron Syndrome - From Man to Mouse; Laron, Z., Kopchick , J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Laron, Z. Adjustment and Rehabilitation Problems of Children, Adolescents, and Adults with Laron Syndrome. In Laron Syndrome - From Man to Mouse; Laron, Z., Kopchick , J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Shevah, O.; Laron, Z. Patients with congenital deficiency of IGF-I seem protected from the development of malignancies: a preliminary report. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2007, 17, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steuerman, R.; Shevah, O.; Laron, Z. Congenital IGF1 deficiency tends to confer protection against post-natal development of malignancies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011, 164, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z.; Anin, S.; Klipper-Aurbach, Y.; et al. Effects of insulin-like growth factor on linear growth, head circumference, and body fat in patients with Laron-type dwarfism. Lancet. 1992, 339, 1259–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z. Emerging treatment options for patients with Laron syndrome. Expert Opinion on Orphan Drugs. 2014, 2, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laron, Z. Insulin-like growth factor-I treatment of children with Laron syndrome (primary growth hormone insensitivity). Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2008, 5, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klinger, B.; Laron, Z. Three year IGF-I treatment of children with Laron syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1995, 8, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laron, Z. IGF-I Treatment of Patients with Laron Syndrome. In Laron Syndrome - From Man to Mouse; Laron, Z., Kopchick, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 343–380. [Google Scholar]

- Bisker-Kassif, O.; Kauli, R.; Lilos, P.; Laron, Z. Biphasic response of subscapular skinfold thickness to hGH or IGF-1 administration to patients with congenital IGHD, congenital MPHD and Laron syndrome. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2014, 8, e55–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klinger, B.; Anin, Z.; Flexer, Z.; Laron, Z. IGF-1 treatment of adult patients with Laron Syndrome. In: Laron Z, Parks J S (eds.) Lessons from Laron syndrome (LS) 1966-1992. 1993, 24, 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Laron, Z.; Werner, H. Administration of insulin like growth factor I (IGFI) lowers serum lipoprotein(a)-impact on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2023, 71, 101548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheinowitz, M.; Feinberg, M.S.; Laron, Z. IGF-I replacement therapy in children with congenital IGF-I deficiency (Laron syndrome) maintains heart dimension and function. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2009, 19, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbloom, A.L. A half-century of studies of growth hormone insensitivity/Laron syndrome: A historical perspective. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2016, 28, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbloom, A.L.; Guevara-Aguirre, J.; Rosenfeld, R.G.; Francke, U. Growth hormone receptor deficiency in Ecuador. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999, 84, 4436–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guevara-Aguirre, J.; Balasubramanian, P.; Guevara-Aguirre, M.; Wei, M.; Madia, F.; Cheng, C.W.; Hwang, D.; Martin-Montalvo, A.; Saavedra, J.; Ingles, S.; de Cabo, R.; Cohen, P.; Longo, V.D. Growth hormone receptor deficiency is associated with a major reduction in pro-aging signaling, cancer, and diabetes in humans. Sci Transl Med. 2011, 3, 70ra13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guevara-Aguirre, J.; Teran, E.; Lescano, D.; Guevara, A.; Guevara, C.; Longo, V.; Gavilanes, A.W.D. Growth hormone receptor deficiency in humans associates to obesity, increased body fat percentage, a healthy brain and a coordinated insulin sensitivity. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2020, 51, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nashiro, K.; Guevara-Aguirre, J.; Braskie, M.N.; Hafzalla, G.W.; Velasco, R.; Balasubramanian, P.; Wei, M.; Thompson, P.M.; Mather, M.; Nelson, M.D.; Guevara, A.; Teran, E.; Longo, V.D. Brain Structure and Function Associated with Younger Adults in Growth Hormone Receptor-Deficient Humans. J Neurosci. 2017, 37, 1696–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, H. Toward gene therapy of Laron syndrome. Gene Ther. 2022, 29, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).