1. Introduction

Rickets was first described in the 17th century by Whistler (1645) and Glisson (1650) [

1]. Later, McCune (1935) differentiated vitamin D-resistant rickets from late-onset vitamin D deficiency rickets, and Albright et al. (1937) provided a detailed definition of vitamin D-resistant rickets [

1]. In 1961, Prader first reported vitamin D-dependent rickets (VDDR) [

2]. VDDR is classified into five types or subtypes: VDDR type 1A (VDDR1A, MIM # 26470), VDDR type 1B (VDDR1B, MIM # 600081), VDDR type 2A (VDDR2A; MIM # 277440), VDDR type 2B (VDDR2B, MIM # 600785), and VDDR type 3 (VDDR3, MIM # 619073) [

3].

Vitamin D-dependent Rickets Type 1A (VDDR1A) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by biallelic mutations in the

CYP27B1 gene (MIM * 609506), which encodes the enzyme 1-alpha hydroxylase [

4]. The

CYP27B1 gene is located on chromosome 12p13.3 and consists of nine exons. This enzyme is critical for converting 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) into its active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol), in the kidneys. Calcitriol regulates calcium and phosphate homeostasis, promoting normal bone mineralization and skeletal development. A deficiency or dysfunction of the CYP27B1 enzyme leads to severe hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, and impaired bone mineralization [

1]. The global prevalence of VDDR1A is not accurately known. In Denmark, the prevalence of hereditary rickets is estimated at 4.8 per 100,000 children [

5]. In the Charlevoix-Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region of Québec, De Braekeleer and Larochelle estimated the prevalence of VDDR1A to be one in 2,916 live births, with a carrier rate of one in 27 individuals [

6].

Vitamin D-dependent Rickets Type 1A (VDDR1A) is characterized by skeletal deformities such as bowed legs (genu varum), knock-knees (genu valgum), thickened wrists and ankles, frontal bossing, hypotonia, failure to thrive, seizures, and delayed motor milestones [

7]. In severe cases, hypocalcemia-induced seizures may occur [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Growth retardation is a prominent feature of VDDR1A, as impaired bone mineralization delays bone formation and growth plate closure, leading to shorter stature and slower skeletal development, significantly impacting final height [

3].

In VDDR1A, calcium levels are typically low due to impaired intestinal absorption of calcium caused by a deficiency of active vitamin D [

11]. Phosphate levels may initially be within the normal or low-normal range but generally decline over time due to prolonged parathyroid hormone (PTH)-induced renal phosphate wasting [

12]. Elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels are a hallmark of VDDR1A, reflecting increased osteoblastic activity as the body attempts to compensate for impaired bone mineralization [

13]. Persistent elevation of PTH levels indicates secondary hyperparathyroidism, a compensatory response to hypocalcemia. Vitamin D metabolism is significantly disrupted in VDDR1A, with 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels often appearing normal or mildly elevated, further complicating the biochemical profile of the disease [

7].

Radiographic imaging is crucial in diagnosing VDDR1A [

3,

7,

14]. Early radiographic signs include increased growth plate height, widening of the epiphyseal plate, and the disappearance of the zone of provisional calcification at the interface between the epiphysis and metaphysis, reflecting delayed and disrupted mineralization [

3]. Distinctive features, such as cupping, fraying, and splaying of the metaphyses, are typically observed, particularly in the wrists, knees, and ankles [

14]. Additionally, pseudofractures on the compression side of the bone, known as Looser’s zones, have been noted [

7].

The

CYP27B1 pathogenic variants causing VDDR1A are diverse, including missense, nonsense, frameshift, and splice site mutations [

15]. According to the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) (

https://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/gene.php?gene=CYP27B1; accessed on February 07, 2025), a total of 116 pathogenic mutations in the

CYP27B1 gene have been identified as associated with VDDR1A. The most commonly reported mutations across different populations with VDDR1A were p.F443Pfs*24, c.195+2T>G, and p.V88Wfs*71 [

15]. These mutations occurred in either homozygous or compound heterozygous states, con-tributing to the genetic diversity observed in VDDR1A cases.

In Vietnam, studies on hereditary rickets, including VDDR1A, is limited. Although rickets is a well-documented health concern among Vietnamese children, most cases are attributed to nutritional deficiencies due to inadequate vitamin D intake and limited sunlight exposure. This study aimed to describe the clinical, radiological, biochemical, and molecular characteristics of 19 Vietnamese children from 15 unrelated families diagnosed with VDDR1A at the Vietnam National Children’s Hospital between January 2023 and December 2024.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

This retrospective descriptive study focused on children with a confirmed diag-nosis of VDDR1A. Data were collected from medical records, including clinical, bio-chemical, radiological, and genetic information. A total of 19 children from 17 families were included in the study.

Children were diagnosed with VDDR1A based on clinical signs, biochemical findings, radiological features, and genetic testing. Clinical signs included skeletal deformities such as genu varum, genu valgum, rachitic rosary, and frontal bossing. Biochemical studies revealed hypocalcemia, normal or low serum phosphate, and elevated serum levels of alkaline phosphatase and parathyroid hormone, with normal or increased plasma concentrations of 25(OH)D. Radiological findings showed cupping, splaying, fraying, rachitic rosary, or pseudofractures on X-rays. Genetic testing confirmed the diagnosis by identifying biallelic pathogenic variants in the CYP27B1 gene.

The study was conducted at the Center for Endocrinology, Metabolism, Genetics, and Molecular Therapy at the Vietnam National Children’s Hospital from January 2023 to December 2024.

2.2. Clinical Characteristics

Data were extracted from medical records and laboratory databases. Height and weight were evaluated using the WHO growth chart. Biochemical parameters, including serum calcium, serum phosphate, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and parathyroid hormone (PTH), were measured using standardized methods on the Beckman Coulter AU5800 (Beckman Coulter, Tokyo, Japan) at the biochemistry department. Bone X-rays were performed using the Carestream DRX1-System (Carestream, WA, USA) at the diagnostic imaging department. Radiographs of the wrists and knees were examined for signs of rickets. To quantify the severity of radiographic changes, the Rickets Severity Score (RSS) was applied [

14]. This scoring system evaluates abnormalities at key skeletal sites, including the wrists and knees, based on growth plate widening, metaphyseal fraying, and cupping (

Table 1). Each parameter is scored on a scale from 0 (normal) to 10 (severe), with higher scores indicating more severe rickets. RSS provides an objective measure for monitoring disease progression, evaluating treatment effectiveness, and comparing clinical outcomes among patients [

14].

2.3. Genetic Testing

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole-blood samples using the QIAamp DNA Blood Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genetic testing was conducted at GC Genome (GC Genome Corporation, Yongin, South Korea) and Invitae (Invitae Corporation, San Francisco, CA, USA). At GC Genome, all exons of 5,870 genes were captured using the Celemics G-Mendeliome DES Panel. Sequencing was performed on the MGI DNBSEQ-G400 platform, generating 2 × 100 bp paired-end reads. The DNA sequence reads were aligned to the reference sequence based on public human genome build GRCh37/UCSC hg19. At Invitae, a hypophosphatemia panel Genomic DNA was extracted from whole- blood samples using the QIAamp DNA Blood Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genetic testing was performedconducted at GC Genome (GC Genome Corporation, Yongin, South Korea) and Invitae (Invitae Corpo-ration, San Francisco, CA, USA). At the GC Genome (GC Genome Corporation, Yongin, South Korea),, all the exons of 5,870 genes were captured using the Celemics G-Mendeliome DES Panel. Sequencing was performed on the MGI DNBSEQ-G400 platform, generating 2 × 100 bp paired-end reads. The DNA sequence reads were aligned to the reference sequence based on the public human genome build GRCh37/UCSC hg19. A theAt Invitae, a hypophosphatemia panel was used, including 13 genes, was used. Genomic DNA samples were enriched for targeted regions employingusing a hybridization-based protocol and sequenced utilizingusing Illumina technology, as previously described including 13 genes (

ALPL (NM_000478.5),

CLCN5 (NM_000084.4),

CYP27B1 (NM_000785.3),

CYP2R1 (NM_024514.4),

DMP1 (NM_004407.3),

ENPP1 (NM_006208.2),

FAH (NM_000137.2),

FAM20C (NM_020223.3),

FGF23 (NM_020638.2),

FGFR1 (NM_023110.2),

PHEX (NM_000444.5),

SLC34A3 (NM_080877.2), and

VDR (NM_001017535.1)) were used. Genomic DNA samples were enriched for targeted regions using a hybridization-based protocol and sequenced using Illumina technology as previously described [

16].

Data were filtered and analyzed to identify sequence variants using an in-house bioinformatics pipeline. The identified variants were interpreted according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) classification system [

17] and cross-referenced with the ClinVar database to confirm pathogenicity.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics 20 to calculate means and standard deviations. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Presentation

The study included 19 children from 17 unrelated families, with a relatively balanced gender distribution: 52.6% were male, and 47.4% were female (

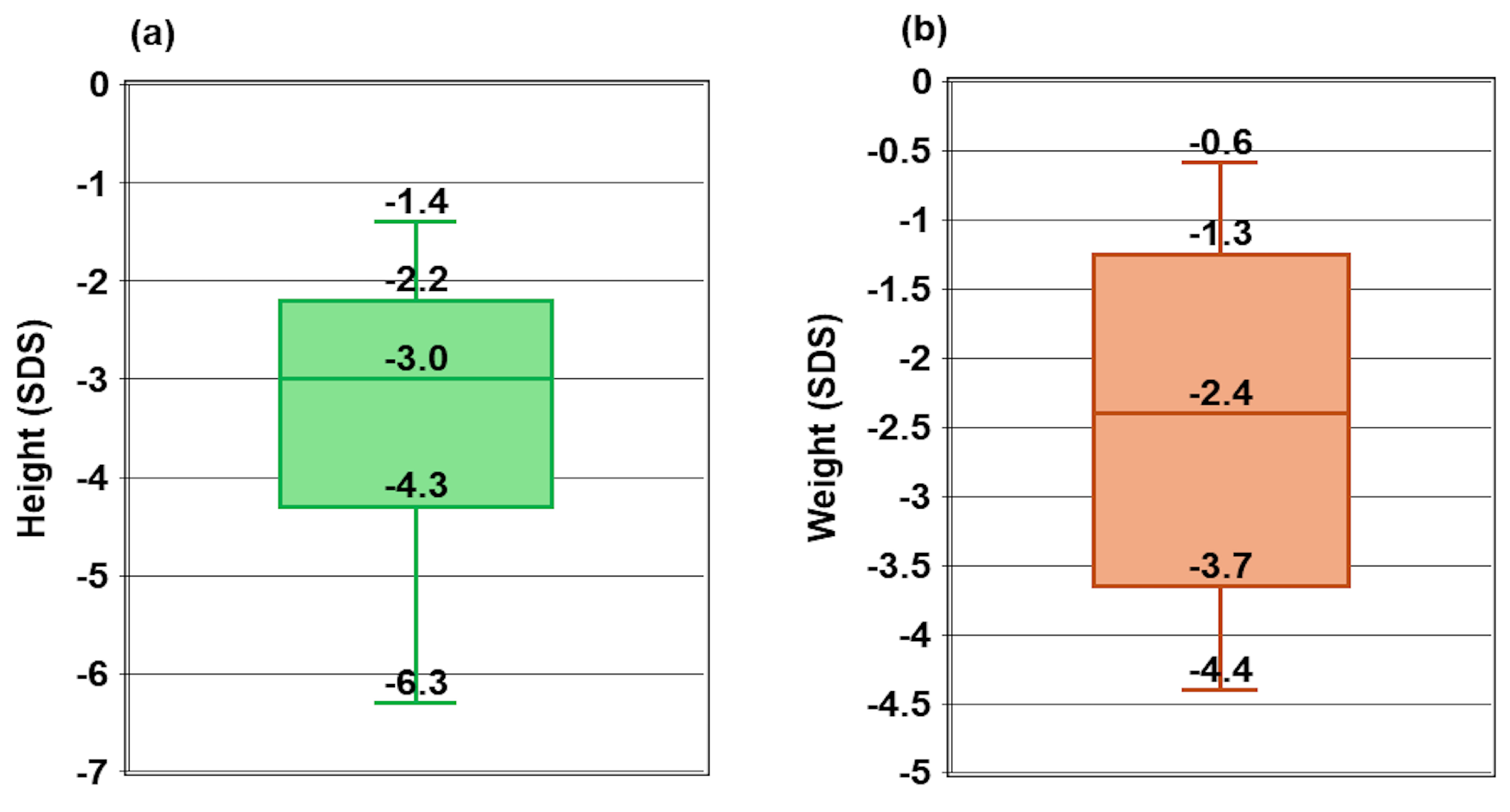

Table 2). The median age of diagnosis for rickets was 19.2 months, ranging from 8.3 to 34.4 months. The median time to diagnosis of Vitamin D-dependent Rickets Type 1A (VDDR1A) was 7.5 months, with a wide range from 1.1 to 148.0 months. The median height was -3.0 SDS, ranging from -6.3 SDS to -1.4 SDS (

Figure 1a), while the median weight was -2.4 SDS, ranging from -4.4 SDS to -0.6 SDS (

Figure 1b).

All children (100%) exhibited thickened wrists and ankles (

Table 2). Genu varum or genu valgum was present in 94.7% of the children. Delayed walking was observed in 57.9% of the cases. Frontal bossing and chest deformities were noted in 52.6% of the children. Seizures occurred in 31.6% of the children, while bone fractures were reported in only two cases (10.5%).

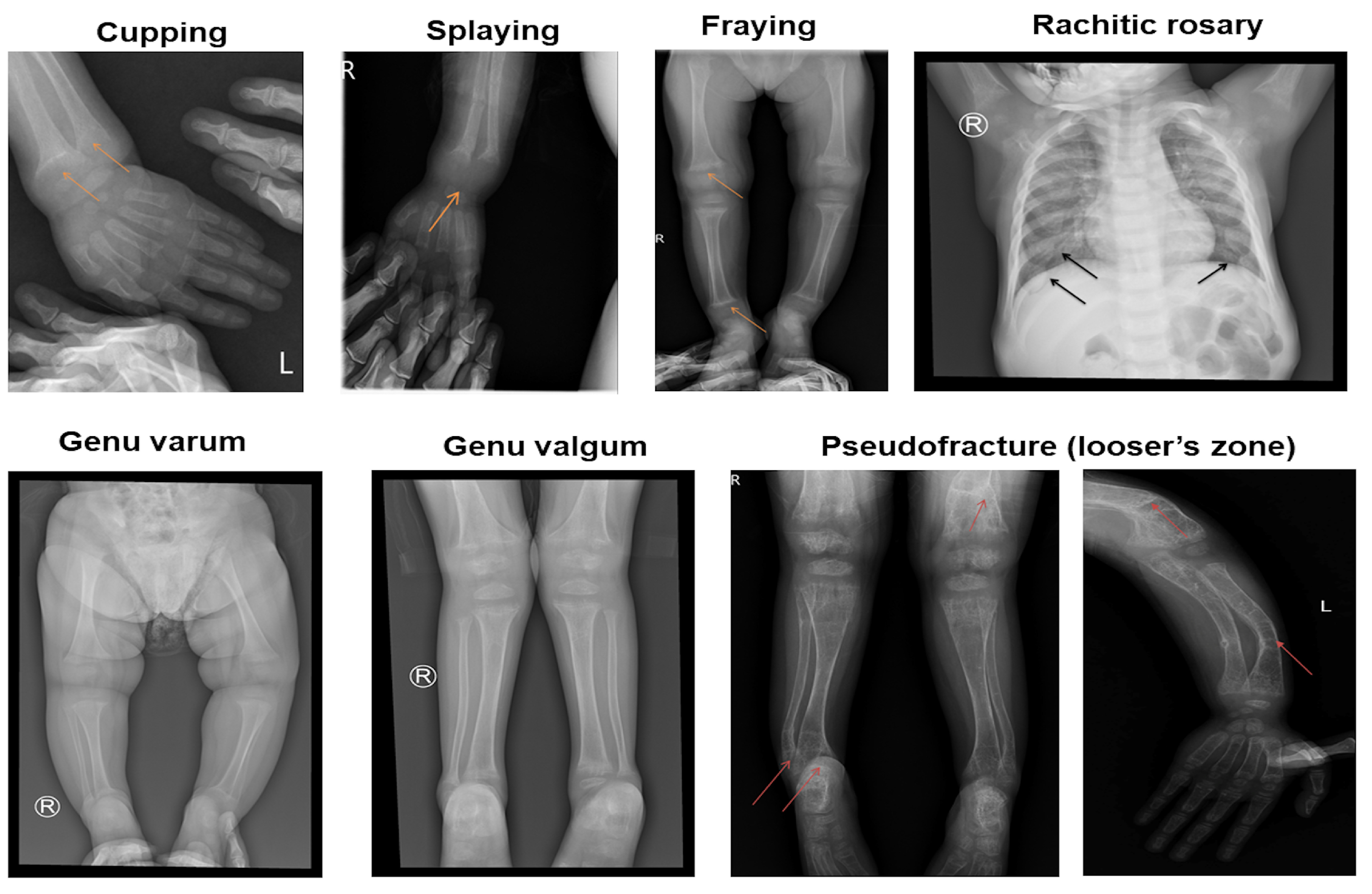

Cupping, splaying, and fraying were observed in all children in this study (

Table 2 and

Figure 2). Rachitic rosary was present in 12 out of 19 children (63.2%). Pseudofractures on the compression side of the bone, known as Looser’s zones, were observed in six out of 19 children (31.6%). All children had a Rickets Severity Score (RSS) of 10, indicating severe rickets.

Serum total calcium levels were significantly lower than the normal reference range (2.2–2.6 mmol/L), with a mean value 0.5 ± 0.3 mmol/L, indicating hypocalcemia. Serum phosphate levels were also reduced (0.8 ± 0.4 mmol/L; normal: 1.05–1.9 mmol/L), with 11 out of 19 children identified as having hypophosphatemia. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels were markedly elevated (1644.2 ± 917.1 UI/L; normal: 156–369 UI/L), reflecting increased bone turnover. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels were significantly elevated (457.7 ± 260.7 ng/mL; normal: 11–69 ng/mL), indicating secondary hyperparathyroidism. Despite the metabolic abnormalities, 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were within a broad range (140.5 ± 109.0 nmol/L; normal: 50–250 nmol/L).

Table 3.

Biochemical findings of children with VDDR1A.

Table 3.

Biochemical findings of children with VDDR1A.

| Subclinical Testings |

Normal Range |

n |

Results |

Note |

| Serum total calcium (mmol/L) |

2.2–2.6 |

19 |

1.5±0.3 |

18 hypocalcemia |

| Serum phosphate (mmol/L) |

1.05–1.95 |

19 |

0.8 ± 0.4 |

11 hypophosphatemia |

| Alkaline phosphatase (UI/L) |

156-369 |

18 |

1644.2 ± 917.1 |

18 elevated |

| Parathyroid hormone (ng/mL) |

11-69 |

16 |

457.7 ± 260.7 |

16 elevated |

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D (nmol/L) |

50-250 |

17 |

140.5±109.0 |

|

3.2. Genetic Findings

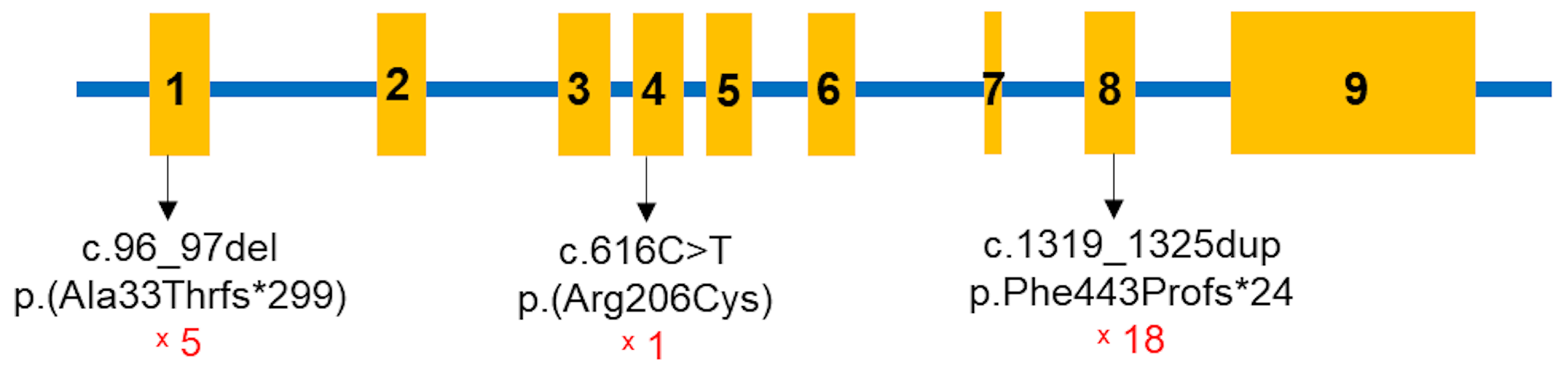

All children in the study were found to have pathogenic variants in both alleles of the

CYP27B1 gene (Table 4,

Figure 2). A total of three

CYP27B1 variants were identified among the 19 children: c.96_97del p.(Ala33Thrfs*299), c.616C>T p.(Arg206Cys), and c.1319_1325dup p.(Phe443Profs*24). The most common variant was c.1319_1325dup p.(Phe443Profs*24) in exon 8. Except for patient 2, 18 children carried this mutation, with 14 in the homozygous state and four in the compound heterozygous state. The c.96_97del p.(Ala33Thrfs*299) variant was present in five children, while c.616C>T p.(Arg206Cys) was identified in one patient (

Figure 3). Sanger sequencing was performed for the parents of 13 families, revealing that all were carriers of pathogenic variants in the heterozygous state (Table 4).

Table 4.

CYP27B1 variants identified in the Vietnamese children with VDDR1A.

Table 4.

CYP27B1 variants identified in the Vietnamese children with VDDR1A.

| Patient |

Sex |

Age of Onset

(Months) |

Exon |

State in the Children |

c.DNA Change |

Protein Change |

Inheritance |

| 1 |

M |

12.1 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 2a |

M |

24.9 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 2b |

F |

28.5 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 3 |

M |

22.9 |

1/4 |

Compound heterozygous |

c.96_97del/

c.616C>T |

p.Ala33Thrfs*299/

p.Arg206Cys |

n/a |

| 4a |

F |

11.1 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 4b |

M |

17.5 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Paternal /Maternal |

| 5 |

F |

19.3 |

8/1 |

Compound heterozygous |

c.1319_1325dup/

c.96_97del |

p.Phe443Profs*24/ p.Ala33Thrfs*299 |

Paternal /Maternal |

| 6 |

F |

31.4 |

8/1 |

Compound heterozygous |

c.1319_1325dup/

c.96_97del |

p.Phe443Profs*24/ p.Ala33Thrfs*299 |

n/a |

| 7 |

F |

17.1 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 8 |

F |

25.0 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 9 |

F |

20.4 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 10 |

M |

14.4 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 11 |

M |

34.4 |

8/1 |

Compound heterozygous |

c.1319_1325dup/

c.96_97del |

p.Phe443Profs*24/ p.Ala33Thrfs*299 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 12 |

F |

15.1 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

n/a |

| 13 |

M |

25.2 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Paternal /Maternal |

| 14 |

M |

13.5 |

8 |

Compound heterozygous |

c.1319_1325dup/

c.96_97del |

p.Phe443Profs*24/ p.Ala33Thrfs*299 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 15 |

M |

20.2 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 16 |

M |

12.3 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Maternal/Paternal |

| 17 |

F |

8.3 |

8 |

Homozygous |

c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

n/a |

The c.1319_1325dup p.(Phe443Profs*24) variant was reported in dbSNP155 as well as in the ClinVar database as a pathogenic variant. It has also been documented in VDDR1A patients in previous literature (Table 5). The c.96_97del p.(Ala33Thrfs*299) variant was reported as pathogenic in the ClinVar database but has not been described in the literature (Table 5). The c.616C>T p.(Arg206Cys) variant was not previously reported in ClinVar, dbSNP155, or the literature (Table 5). According to ACMG guidelines, it was classified as a likely pathogenic variant (Table 5). No genotype-phenotype correlation was observed in this study.

Table 5.

Classification of three CYP27B1 variants identified in this study.

Table 5.

Classification of three CYP27B1 variants identified in this study.

| c.DNA Change |

Aa Change |

Effect |

Mutation Taster |

dbSNP155 |

ClinVar |

ACMG Classification |

Literature |

| c.96_97delAG |

p.Ala33Thrfs*299 |

Frameshift |

Disease causing |

rs1955367513 |

Pathogenic |

Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PM3, PP1, PP3, PP4, and PP5) |

Novel |

| c.616C>T |

p.Arg206Cys |

Missense |

Disease causing |

|

|

Likely pathogenic (PM2, PM3, PP3, and PP4) |

Novel |

| c.1319_1325dup |

p.Phe443Profs*24 |

Frameshift |

Disease causing |

rs780950819 |

Pathogenic |

Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PM3, PP3, PP4, and PP5) |

[10,15,19,20,21,22] |

4. Discussion

The median age of rickets diagnosis in this study was 19.2 months, with the youngest being 8.3 months and the oldest 34.4 months, consistent with findings from other studies [

10,

15,23]. Lin et al. reported a mean age of 2.1±0.8 years in twelve children from southern China with VDDR1A [23]. In Turkish patients, Dursun et al. observed a mean age at diagnosis of 13.1±7.4 months among 11 children [

10]. Similarly, Kaygusuz et al. found a median age of 16.0 months at diagnosis among 24 children with a homozygous p.Phe443Profs*24 genotype [

15]. The delay in diagnosis reflects the rarity of the disorder and its nonspecific early symptoms. According to Haffner et al., symptoms of rickets are most pronounced during infancy and puberty, stages characterized by increased calcium demands for growth [

7]. In this study, the median time to a definitive VDDR1A diagnosis was 7.5 months. The earliest diagnosis was made concurrently with rickets detection, facilitated by an affected older sibling, whereas the latest diagnosis was made after twelve years. The primary reason for delayed diagnosis was the limited access to genetic analysis, which is essential for confirming VDDR1A.

Growth impairment was evident among the children in this study. The median weight standard deviation score (WtSDS) was -2.4, reflecting significant stunting and failure to thrive. At diagnosis, 18 out of 19 children had a height standard deviation score (HtSDS) below -2 SDS (WHO) compared to the normal reference range. The median HtSDS was -3.0 SDS, ranging from -6.3 to -1.4, consistent with the findings of Lin et al. [23], who reported a mean HtSDS of -3.8 ± 2.1 (range -6.5 to -0.4). In contrast, Kaygusuz et al. [

15] observed a slightly higher height at diagnosis, with a mean of -2.22 SD (range: -5.7 to -0.25). The growth impairment in this study is likely due to defective bone mineralization, particularly affecting the growth plates of long bones [24].

All children in this study exhibited skeletal abnormalities, including enlargement of the wrists and ankles and lower limb deformities, indicating severe disruptions in bone mineralization and alignment. Other rickets-related symptoms, such as rachitic rosary and chest deformities, were less common. These findings are consistent with Lin et al., who reported a high prevalence of thickened wrists and ankles (91.7%), rachitic rosary (50.0%), and pectus carinatum (50.0%) [23]. Similarly, Ozden et al. reported that among nine children diagnosed with VDDR1A, four out of five had wrist and ankle enlargement, six out of nine exhibited rachitic rosary, and chest deformities were present in two out of nine cases [25].

Motor development was significantly delayed in 57.9% of the children, with delayed walking being the most common reason for seeking medical attention. This delay was mainly due to osteomalacia, which compromises bone structural integrity, hindering the ability to support weight and physical activity [

7]. Additionally, seizures resulting from hypocalcemia were reported in six out of 19 children (31.5%). Notably, seizures were relatively uncommon in children under six months of age, reflecting age-dependent variability in clinical presentation. These findings are consistent with Edouard et al., who reported hypocalcemic seizures in four out of 21 children with VDDR1A [

9]. Similarly, in the study by Dursun et al., only one out of 11 children exhibited seizure symptoms [

10].

In this study, only two children presented with bone fractures, which is lower than the incidence reported by Lin et al., who documented fractures in four out of 12 children [23]. It is also comparable to the findings of Tahir et al., who observed fractures in three out of 22 children [26]. This relatively low incidence of fractures contrasts with findings from other studies, suggesting variability in fracture occurrence among children with VDDR1A.

Laboratory evaluations revealed severe disruptions in calcium-phosphate homeo-stasis and bone metabolism among the children. The mean total serum calcium was 1.5 ± 0.3 mmol/L, consistent with hypocalcemia. Serum phosphate levels were moderately low, with 11 children showing hypophosphatemia. These findings align with the typical biochemical profile of VDDR1A. In VDDR1A, serum phosphate levels are generally reduced due to secondary hyperparathyroidism induced by hypocalcemia. Hypocalcemia triggers increased secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which enhances renal phosphate excretion, leading to further declines in serum phosphate levels [27]. This pattern of hypophosphatemia was also reported in other studies of vitamin D-dependent rickets, as observed by Dursun et al. [

10], Lin et al. [23], and Tahir et al. [26].

The Rickets Severity Score (RSS) of 10 observed in this study shows advanced rickets with significant skeletal deformities. This high score reflects severe clinical manifestations, including pronounced bowing of long bones, widened growth plates, and metaphyseal fraying. These findings highlight the chronic and inadequately treated progression of the disease [

14].

Radiographic abnormalities are crucial in the diagnostic assessment of rickets [

7]. Cupping, splaying, and fraying, characteristic radiographic features of rickets, were observed in all children in this study. Pseudofractures, known as Looser’s zones, were also identified [28]. These pseudofractures occur due to mechanical stress exerted by major blood vessels on the uncalcified cortex of osteomalacic bones, leading to symmetrical locations of transverse zones of rarefaction. These pseudofractures typically range from 1 mm to 1 cm in width, are often multiple, symmetrically distributed, and can appear in otherwise structurally normal bone [29]. In this study, six children showed radiographic evidence of pseudofractures.

The c.1319_1325dup p.(Phe443Profs*24) variant, a common mutation found worldwide in VDDR1A patients [

15], was also the most frequently identified variant in this study. The second most common variant was c.96_97del p.(Ala33Thrfs*299), which causes a frameshift at codon 33, leading to a premature stop codon after an additional 299 amino acids. This study is the first to report this pathogenic variant in a VDDR1A patient. A novel missense mutation, c.616C>T p.(Arg206Cys), was also identified. This mutation results in the substitution of arginine with cysteine at codon 206 of the

CYP27B1 protein. These nucleotide changes cause structural alterations in the

CYP27B1 protein, leading to abnormal protein function.

No genotype-phenotype correlation was observed in this study. There were no significant differences in total blood calcium, ionized calcium, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), or parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels among children with different genotypes. These findings differ from those reported by Kaygusuz et al., who identified an association between the c.195+2T>G genotype and severe clinical phenotypes, as well as the p.K192E genotype with milder clinical manifestations [

15]. In contrast, neither of these genotypes was present in the children in this study.

5. Conclusions

Vitamin D-dependent rickets type 1A is a rare disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the CYP27B1 gene, leading to a loss or reduction of 1α-hydroxylase activity, which impairs skeletal mineralization and causes bone deformities. The most common genotype identified in this study was the homozygous pathogenic variant c.1319_1325dup in exon 8. However, no clear association between genotype and phenotype was observed. Two novel CYP27B1 variants were identified, expanding the known mutation spectrum of Vitamin D-dependent rickets type 1A.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.T.T. and C.D.V.; methodology, T.A.T.T., T.M.D., K.N.N. and C.D.V.; software, T.A.T.T., N.L.N. and T.H.T.; validation, T.M.D., T.B.N.C, B.P.T. and V.K.T.; formal analysis, T.A.T.T., N.L.N., N.X.K., N.T.K.L. and N.T.T.; investigation, T.A.T.T., N.L.N., K.N.N., T.B.N.C., B.P.T., N.T.T.H. and N.T.K.L.; data curation, T.M.D., H.H.N. and C.D.V.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.T.T. and N.L.N.; writing—review and editing, T.A.T.T., T.M.D., N.L.N., K.N.N., T.B.N.C., N.T.T.H., V.K.T., T.H.T., N.X.K., N.T.K.L., N.T.T., H.H.N. and C.D.V.; visualization, T.M.D., B.P.T., N.T.T.H., V.K.T., T.H.T., N.X.K., N.T.K.L., N.T.T. and H.H.N.; supervision, H.H.N. and C.D.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology for The Excellent research team of Institute of Genome Research Grant number NCXS.01.03/23-25.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Children’s Hospital (protocol code 2471/BVNTW-HĐĐĐ on September 15 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Miller, W.L.; Imel, E.A. Rickets, Vitamin D, and Ca/P Metabolism. Horm Res Paediatr 2022, 95, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, B.J.; Snoddy, A.M.E.; Munns, C.; Simm, P.; Siafarikas, A.; Jefferies, C. A Brief History of Nutritional Rickets. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, M.A. Diagnosis and Management of Vitamin D Dependent Rickets. Front Pediatr 2020, 8, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acar, S.; Demir, K.; Shi, Y. Genetic Causes of Rickets. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2017, 9, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck-Nielsen, S.S.; Brock-Jacobsen, B.; Gram, J.; Brixen, K.; Jensen, T.K. Incidence and Prevalence of Nutritional and Hereditary Rickets in Southern Denmark. Eur J Endocrinol 2009, 160, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Braekeleer, M.; Larochelle, J. Population Genetics of Vitamin D-Dependent Rickets in Northeastern Quebec. Ann Hum Genet 1991, 55, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffner, D.; Leifheit-Nestler, M.; Grund, A.; Schnabel, D. Rickets Guidance: Part I-Diagnostic Workup. Pediatr Nephrol 2022, 37, 2013–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodamani, M.H.; Sehemby, M.; Memon, S.S.; Sarathi, V.; Lila, A.R.; Chapla, A.; Bhandare, V.V.; Patil, V.A.; Shah, N.S.; Thomas, N.; et al. Genotype and Phenotypic Spectrum of Vitamin D Dependent Rickets Type 1A: Our Experience and Systematic Review. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2021, 34, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edouard, T.; Alos, N.; Chabot, G.; Roughley, P.; Glorieux, F.H.; Rauch, F. Short- and Long-Term Outcome of Patients with Pseudo-Vitamin D Deficiency Rickets Treated with Calcitriol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, F.; Özgürhan, G.; Kırmızıbekmez, H.; Keskin, E.; Hacıhamdioğlu, B. Genetic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Vitamin D Dependent Rickets Type 1A. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2019, 11, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, F.; Chen, N.; Xue, S. Calcium Intake, Calcium Homeostasis and Health. Food Sci Hum Wellness 2016, 5, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergwitz, C.; Jüppner, H. Regulation of Phosphate Homeostasis by PTH, Vitamin D, and FGF23. Annu Rev Med 2010, 61, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannalire, G.; Pilloni, S.; Esposito, S.; Biasucci, G.; Di Franco, A.; Street, M.E. Alkaline Phosphatase in Clinical Practice in Childhood: Focus on Rickets. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1111445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thacher, T.D.; Fischer, P.R.; Pettifor, J.M.; Lawson, J.O.; Manaster, B.J.; Reading, J.C. Radiographic Scoring Method for the Assessment of the Severity of Nutritional Rickets. J Trop Pediatr 2000, 46, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaygusuz, S.B.; Alavanda, C.; Kirkgoz, T.; Eltan, M.; Yavas Abali, Z.; Helvacioglu, D.; Guran, T.; Ata, P.; Bereket, A.; Turan, S. Does Genotype-Phenotype Correlation Exist in Vitamin D-Dependent Rickets Type IA: Report of 13 New Cases and Review of the Literature. Calcif Tissue Int 2021, 108, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.T.M.; Vu, C.D.; Dien, T.M.; Can, T.B.N.; Nguyen, T.T.N.; Nguyen, H.H.; Tran, V.K.; Nguyen, N.L.; Tran, H.T.; Mai, T.T.C.; et al. Phenotypes, Genotypes, Treatment, and Outcomes of 14 Children with Sitosterolemia at Vietnam National Children’s Hospital. J Clin Med 2025, 14, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.J.; Kaplan, L.E.; Perwad, F.; Huang, N.; Sharma, A.; Choi, Y.; Miller, W.L.; Portale, A.A. Vitamin D 1alpha-Hydroxylase Gene Mutations in Patients with 1alpha-Hydroxylase Deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 92, 3177–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.T.; Lin, C.J.; Burridge, S.M.; Fu, G.K.; Labuda, M.; Portale, A.A.; Miller, W.L. Genetics of Vitamin D 1alpha-Hydroxylase Deficiency in 17 Families. Am J Hum Genet 1998, 63, 1694–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, X.; Chen, R.; Lin, X.; Shangguan, H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y. Clinical and Genetic Analysis of Two Chinese Families with Vitamin D-Dependent Rickets Type IA and Follow-Up. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2020, 15, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.; Peña, A.S.; Perano, S.; Atkins, G.J.; Findlay, D.M.; Couper, J.J. First Australian Report of Vitamin D-Dependent Rickets Type I. Med J Aust 2014, 201, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmaz, E.; Zou, M.; Al-Rijjal, R.A.; Bircan, I.; Akçurin, S.; Meyer, B.; Shi, Y. Clinical and Genetic Analysis of Patients with Vitamin D-Dependent Rickets Type 1A. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012, 77, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Guan, Z.; Mei, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Z.; Su, L.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, R.; Liang, C.; Cai, Y.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Long-Term Outcomes of 12 Children with Vitamin D-Dependent Rickets Type 1A: A Retrospective Study. Front Pediatr 2022, 10, 1007219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanchlani, R.; Nemer, P.; Sinha, R.; Nemer, L.; Krishnappa, V.; Sochett, E.; Safadi, F.; Raina, R. An Overview of Rickets in Children. Kidney Int Rep 2020, 5, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozden, A.; Doneray, H. The Genetics and Clinical Manifestations of Patients with Vitamin D Dependent Rickets Type 1A. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2021, 34, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, S.; Demirbilek, H.; Ozbek, M.N.; Baran, R.T.; Tanriverdi, S.; Hussain, K. Genotype and Phenotype Characteristics in 22 Patients with Vitamin D-Dependent Rickets Type I. Horm Res Paediatr 2016, 85, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiosano, D.; Hochberg, Z. Hypophosphatemia: The Common Denominator of All Rickets. J Bone Miner Metab 2009, 27, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, A.D. Radiology of Osteogenesis Imperfecta, Rickets and Other Bony Fragility States. Endocr Dev 2015, 28, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Shah, B.; Nabi, G.; Sofi, F. Looser’s Zone. Oman Med J 2010, 25, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).