1. Introduction

The pituitary gland is a bean-shaped endocrine organ located at the base of the skull, behind the nose, and between the ears, comprising three lobes: anterior, posterior, and intermediate [

1]. The anterior lobe produces hormones that regulate a wide range of bodily functions, including growth and reproduction. These hormones include adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), growth hormone (GH), melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and prolactin (PRL) [

2]. The posterior lobe produces two hormones: antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and oxytocin [

2]. Hypopituitarism is characterized by a partial or complete deficiency of pituitary hormone secretion and occurs in 1 in 4,000 to 1 in 8,000 live births [

3]. If left untreated, it can lead to severe, life-threatening complications [

4]. Congenital hypopituitarism includes severe midline developmental disorders, such as septo-optic dysplasia or anencephaly; isolated hypopituitarism; or a combination of hypopituitarism with other congenital abnormalities, including short neck, cerebellar malformations, sensorineural hearing loss, and polydactyly. It may also involve specific pituitary hormone deficiencies, such as GH, ACTH, TSH, and gonadotropin deficiencies [

5].

Pathogenic variants in genes involved in pituitary development can lead to deficiencies in one or more pituitary hormones. Sanger sequencing has identified the genetic etiology in less than 15% of congenital pituitary hormone deficiency cases [

6]. Next-generation sequencing has proven to be a valuable tool, increasing the molecular diagnostic yield in hypopituitarism to as much as 19.1% [

7,

8]. Currently, 70 genes have been reported to be associated with hypopituitarism [

7]. The most common disease-causing genes include

PROP1, POU1F1, HESX1, LHX3, LHX4, OTX2, GLI2, and

SOX3 [

9]. The

POU1F1 gene (OMIM *173110) encodes POU class 1 homeobox 1 (

POU1F1 or Pit-1), a protein of 317 amino acids [

3] expressed in the anterior pituitary [

10,

11]. Mutations in

POU1F1 are linked to combined pituitary hormone deficiency-1 (CPHD1, MIM #613038), which presents with typical clinical features such as severe short stature, facial dysmorphism, poor feeding during infancy, hypoplasia of the anterior pituitary, and multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies [

9]. The

POU1F1 transcription factor is essential for the development of pituitary cells that produce PRL, GH, and TSH [

12]. Consequently, CPHD1 cases are characterized by deficiencies in GH, TSH, and PRL. CPHD1 is a genetically heterogeneous disorder, often following an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. A systematic phenotype-genotype analysis of 114 patients from 58 studies revealed no significant differences between mutation types [

13]. However, heterozygous patients exhibited significantly higher peak GH levels and a lower prevalence of anterior pituitary hypoplasia compared to homozygous and compound heterozygous patients [

13]. To date, more than 41

POU1F1 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants have been reported in the ClinVar database (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/?term=POU1F1, accessed on March 30, 2024). The majority of these variants occur within the POU-specific domain (13 of 41 variants) and the POU-homeo domain (11 of 41 variants).

In 1985, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued the first worldwide regulation for recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) therapy [

14]. Initially approved for treating growth hormone deficiency (GHD) in children, rhGH therapy is now approved for eight pediatric indications, including GHD, Prader-Willi syndrome, small-for-gestational-age, Turner syndrome, Noonan syndrome, idiopathic short stature (ISS), chronic renal insufficiency, and

SHOX gene mutations [

15]. The starting dose of rhGH and its adjustments are mainly based on body weight or body surface area [

16,

17]. Dosing should be individualized and follow national treatment guidelines. Studies from the National Cooperative Growth Study (NCGS) and Pfizer International Growth Database (KIGS) showed that a higher weekly rhGH dose could result in better height outcomes [

18]. However, larger studies from France (n = 1524), Pharmacia/Pfizer (n = 1258), and the Netherlands (n = 552) found no significant correlation between rhGH doses and adult height (19). Hence, most treatment guidelines recommend starting rhGH therapy at the lower dose range [

19]. Additionally, treatment outcomes of the patients were affected by the age at the start of treatment, height at the initiation of therapy, gender, and the degree of GH deficiency [

20,

21]. Patients who began rhGH therapy at a younger age demonstrated significantly greater improvements in SDS final height [

22]. Patients with a lower pre-treatment height SDS typically exhibited a more pronounced growth response during the first year of therapy and sustain superior long-term growth outcomes compared to those with baseline heights closer to the normal range [

23]. A total of 23,163 adverse events were reported in 14.4% of patients, with 3,108 events (3.1%) assessed as possibly related to treatment [

24]. Discontinuation of rhGH therapy (temporary, permanent, or delayed) due to adverse events occurred in 1.6% of patients, with 0.6% attributed to potentially treatment-related adverse events. The most frequently reported adverse event was headache (0.4%), followed by scoliosis (0.2%). All potential risks should be assessed based on the etiological diagnosis and individualized before initiating rhGH treatment. Treatment guidelines recommend informing patients about potential side effects, such as increased intracranial pressure, progressive scoliosis, femoral epiphyseal slippage due to rapid growth, decreased insulin sensitivity, and reduced endogenous cortisol levels resulting from the effect of rhGH on glucocorticoid metabolism. Importantly, rhGH treatment has not been shown to increase the risk of new malignancies in children without pre-existing risk factors.

Herein, we report six patients with hypopituitarism caused by pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in the POU1F1 gene. Three missense variants, c.428G>A (p.Arg143Gln), c.557T>G p.(Leu186Arg), and c.811C>T p.(Arg271Trp), were identified, with c.557T>G p.(Leu186Arg) being a novel variant. Marked clinical improvement occurred with rhGH and levothyroxine (LT4) therapy.

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Findings

All patients had a normal obstetric history, as well as normal birth weight and height (

Table 1). The youngest diagnosis occurred in patient P3 at 20 days old, while the oldest was in patient P4 at 9 years old. Three out of six patients (P1, P4, and P5) presented with intellectual disability. In contrast, patient P6, diagnosed at eight months old, did not exhibit intellectual disability or motor retardation. All patients showed severe pituitary dwarfism and distinct midfacial hypoplasia, characterized by a prominent forehead, depressed nasal bridge, deep-set eyes, and anteverted nostrils. Bone age was delayed in all patients, with discrepancies between bone age and actual age ranging from six months to eight years.

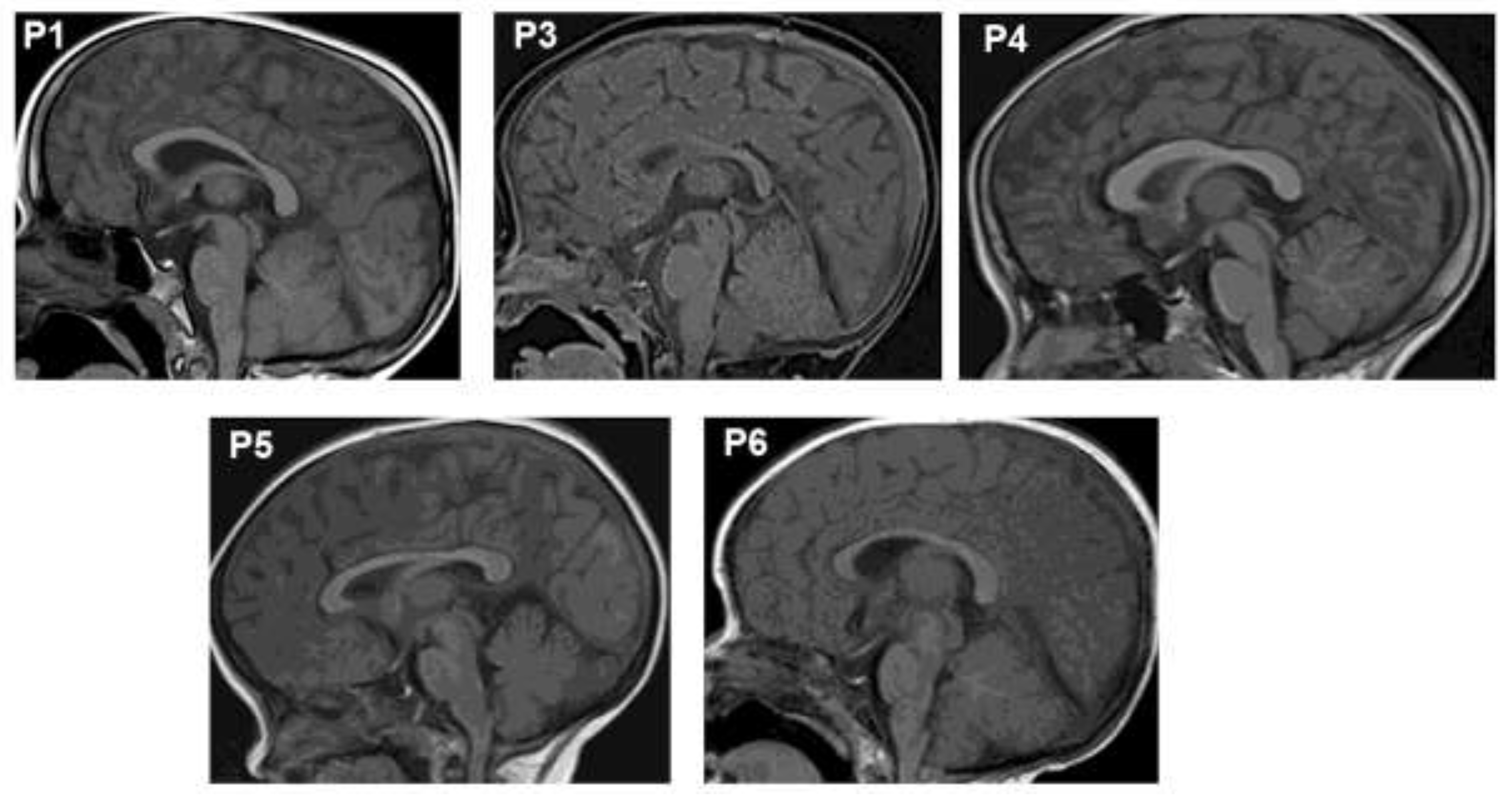

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed anterior pituitary hypoplasia in all six patients (

Figure 1). Patient P1 exhibited the most severely hypoplastic anterior pituitary, measuring 1.4 mm, compared to 1.6–1.7 mm in the other patients. The pituitary stalk and posterior pituitary gland were normal in all cases. All patients presented with thyroid hormone and growth hormone deficiencies (

Table 1). At the time of diagnosis, P1, P2, and P3 had low levels of thyroid hormones (TSH and T4/FT4). Adrenal function was normal at diagnosis and remained so throughout follow-up. At diagnosis, IGF-1 levels were <15 ng/ml, and GH peaks were ≤0.3 ng/ml. Currently, patient P5 has completed puberty with normal levels of sexual hormones (LH: 4.02 IU/l). All patients exhibited prolactin (PRL) deficiency

2.2. Molecular findings

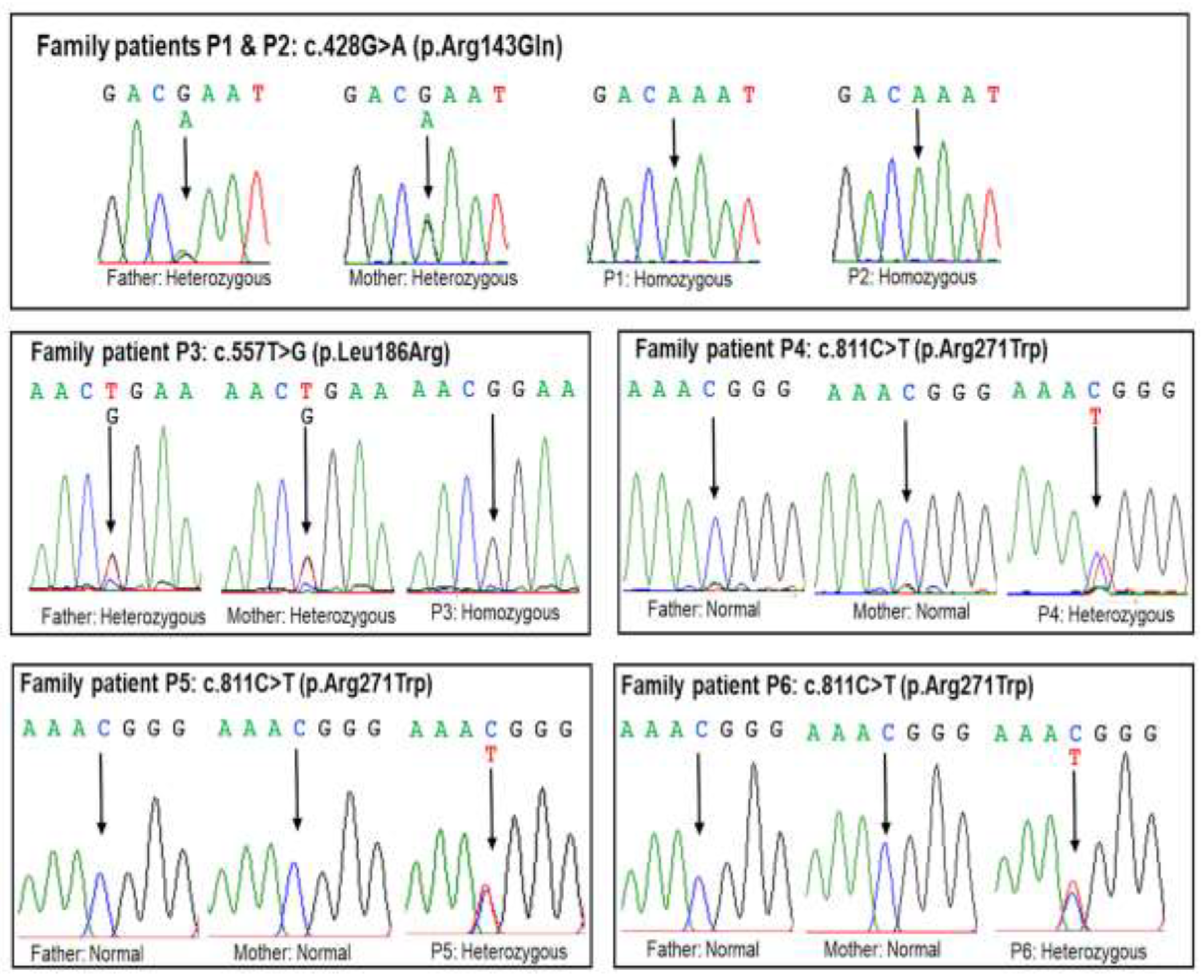

Exome sequencing identified the c.428G>A (p.Arg143Gln) variant in patients P1 and P2 and the c.557T>G p.(Leu186Arg) variant in patient P3, both in the homozygous state within the

POU1F1 gene (

Table 2). The c.811C>T p.(Arg271Trp) variant was detected in patients P4, P5, and P6 in the heterozygous state (

Table 2). Sanger sequencing was performed to confirm the presence of these variants in the patients and to analyze segregation. The results revealed that patients P1, P2, and P3 inherited the mutant alleles from their parents (

Figure 2). However, the parents of patients P4, P5, and P6 carried normal alleles, indicating that the variant in these patients was de novo. The c.557T>G p.(Leu186Arg) variant is a novel variant not reported in the dbSNP154, gnomAD v2.2.1, LOVD v3.0, or ClinVar databases (

Table 2). This variant results in the substitution of leucine with arginine at amino acid position 186 and is predicted to have damaging or deleterious effects by multiple

in silico tools (

Table 2).

Based on ACMG classification, c.428G>A (p.Arg143Gln) and c.557T>G p.(Leu186Arg) variants were classified as a likely pathogenic variants with evidence codes PM2, PM3, PP3, and PP4 (

Table 2). The c.811C>T p.(Arg271Trp) variant was classified as a pathogenic variant in ACMG guidelines supported by evidence codes PS1, PM1, PM2, PM3, PP3, and PP4 (

Table 2).

3.3. Outcomes

Five out of six patients were diagnosed with TSH deficiency and treated with levothyroxine before initiating rhGH therapy. Patient P6 was managed with levothyroxine and rhGH therapy concurrently. The earliest initiation of rhGH therapy was in patient P3 at eight months old, while the latest was in patient P4 at nine years and five months old (

Table 3). Patient P5 exhibited severe short stature at the start of rhGH treatment (-9.2 SDS). All patients showed considerable growth improvements with rhGH therapy. In the first year, patients P1 and P2 both grew 11 cm, patients P4, P5, and P6 grew 17–20 cm, and patient P3 achieved a remarkable 24 cm increase (

Table 3). After three years of treatment, patients P2 and P3 reached normal height. However, patients P1 and P2 discontinued treatment due to economic constraints. Patient P5 reached a height of 143 cm (-2.55 SDS WHO) after five years of treatment and transitioned to GH therapy during the transition phase. Other patients continue daily treatment. Patient P3 experienced scoliosis after one year of rhGH therapy, but the condition resolved after nearly one year of discontinuing treatment. Upon resuming therapy, patient P3 did not experience a recurrence of scoliosis.

3. Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the phenotype, genotype, treatment, and outcomes of six Vietnamese patients with hypopituitarism. All six patients carried likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants in the

POU1F1 gene. Brain MRI revealed anterior pituitary hypoplasia in all patients, a common feature in

CPHD patients with

POU1F1 variants [

25]. No correlation was observed between pituitary size and patient age or variant type. The patients also exhibited physical characteristics such as midline hypoplasia, upturned nose, and protruding forehead [

9,

26].

Although all six patients were eventually diagnosed with combined pituitary hormone deficiency (GH, TSH, and PRL deficiencies), achieving an accurate diagnosis in primary care remains challenging. Delayed diagnosis in patients P1, P4, and P5 led to intellectual disability and poor academic performance. In Vietnam, many regions have implemented newborn screening programs, but these primarily involve TSH screening for congenital hypothyroidism. The onset and severity of TSH deficiency varied among patients. For example, patient P4 underwent regular hospital check-ups for elevated liver enzymes starting at 5 months old, but it took over 19 months to diagnose TSH deficiency. Notably, only 13.5% of patients with

POU1F1 variants initially present with isolated GH deficiency, developing additional TSH deficiency after 1–16 years [

25]. This shows the importance of long-term monitoring in patients with isolated GH deficiency to detect the progression of additional pituitary hormone deficiencies, particularly in those with

POU1F1 variants. Although PRL deficiency is relatively common, it is rarely tested in Vietnam due to its limited clinical significance in pediatrics. Therefore, we recommend including prolactin testing in the diagnostic workup for patients with GH and TSH deficiencies.

Recurrent hypoglycemia is a common symptom in neonatal patients with severe isolated GH deficiency or combined GH deficiency involving other hormones, especially ACTH [

27]. Patients with multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies have a higher incidence of hypoglycemia compared to those with isolated GH deficiency [

28]. In our study, none of the patients experienced hypoglycemia, including patient P3, who was diagnosed in the neonatal period. Patients P2 and P3 presented with prolonged neonatal jaundice, a condition observed in 35% of infants with congenital hypopituitarism [

29].This may be explained by GH deficiency affecting liver function through reduced bile acid synthesis and structural abnormalities of the bile duct [

29].Among the patients in this study, only patient P5 began menstruating at 14 years old. The other patients have not yet reached puberty, a condition that is extremely rare in CPHD patients [

30].

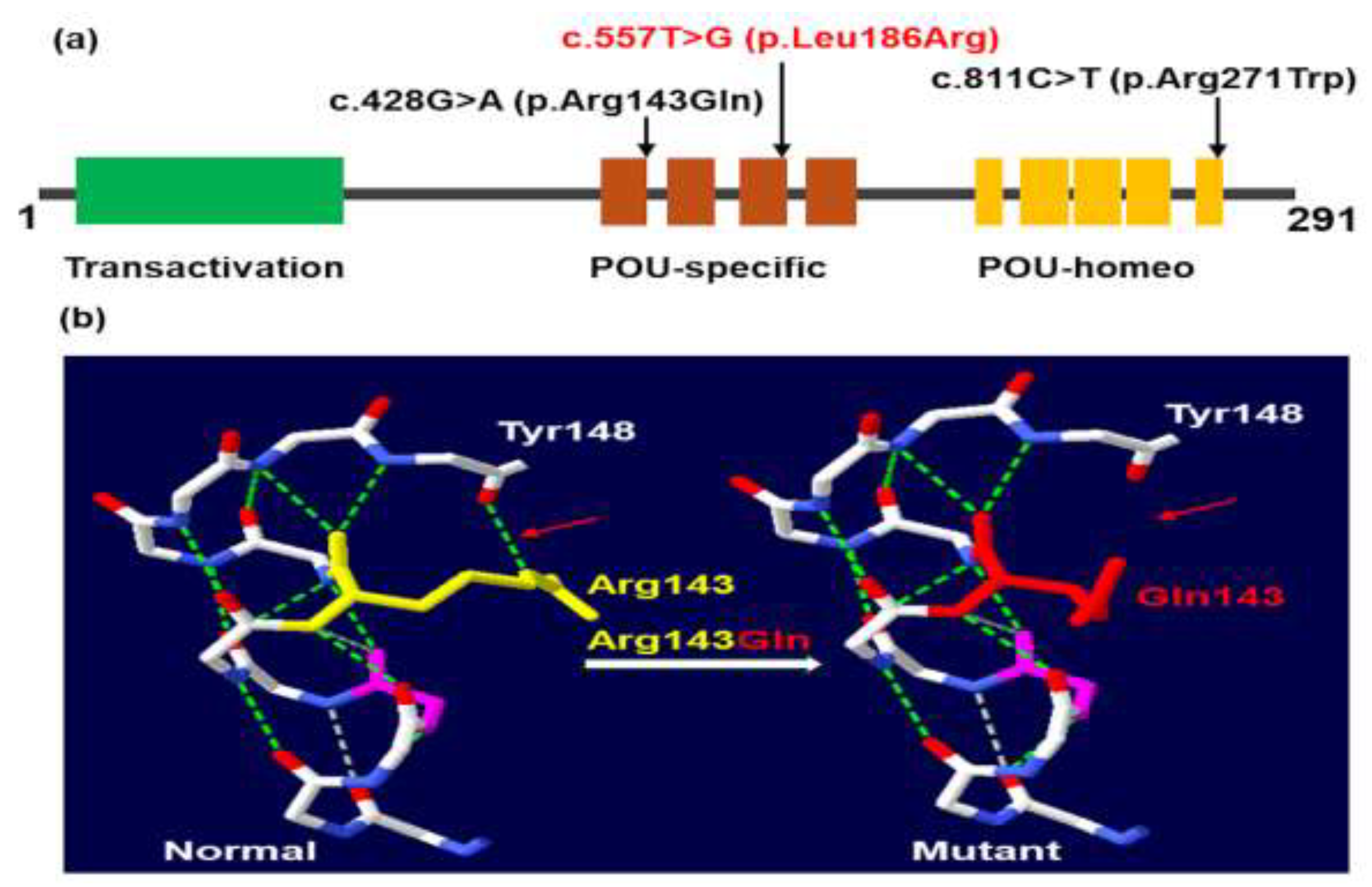

In this study, we identified two missense variants in the POU-specific domain and one missense variant in the POU-homeo domain of the

POU1F1 gene (

Figure 3a). The c.428G>A variant results in an arginine-to-glutamic acid substitution at amino acid position 143, disrupting a hydrogen bond between arginine at position 143 and tyrosine at position 148 (

Figure 3B). The c.428G>A (p.Arg143Gln) variant was first reported in a female CPHD patient with severe short stature, normal intellectual ability, and low levels of GH, TSH, and PRL [

31]. Our patients, P1 and P2, represent the second and third cases with this variant. The phenotype of P1 and P2 closely resembles the case reported by Ohta et al. [

31], except for developmental delays in P2, likely due to delayed GH treatment. The c.557T>G p.(Leu186Arg) variant identified in this study is novel. Patient P3, carrying the novel c.557T>G p.(Leu186Arg) variant, was diagnosed in the neonatal period with symptoms including constipation, prolonged neonatal jaundice, pituitary dwarfism, anterior pituitary hypoplasia, and low levels of IGF1, TSH, ACTH, FT4, GH, LH, and PRL. The third variant, c.811C>T p.(Arg271Trp), was first described by Radovick et al. [

32] and has been reported in approximately 30% of patients with

POU1F1 variants [

9]. In our study, this variant was identified in 3 out of 6 patients, making it the most common variant in CPHD Vietnamese patients. In this study, TSH levels were higher in patients with heterozygous variants compared to those with homozygous variants. However, we did not observe a correlation between peak GH concentrations, the incidence of anterior pituitary hypoplasia, and the state of the variants, as previously reported (13).

All patients responded well to rhGH replacement therapy, which is consistent with findings from previous studies demonstrating the efficacy of rhGH treatment in CPHD patients. According to the Kabi/Pfizer International Growth Study Database (KIGS), patients with CPHD had a height of –3.8 SDS (–5.8 to –2.3) before treatment, –2.8 SDS (–4.6 to –1.3) after one year, and –1.1 SDS (–3.0 to 0.5) at the subadult stage [

33]. Jadhav et al. also reported the clinical efficacy of rhGH in a cohort of CPHD patients with

POU1F1 variants, where 10 out of 15 patients treated with rhGH showed considerable improvement. One patient, treated before one year of age, achieved a final height of –0.9 SDS, highlighting the benefits of early rhGH treatment in achieving nearly normal height [

13]. This trend was mirrored in our study, with patient P3, who began treatment at eight months old, achieving normal height within a year. In contrast, patient P5, who started rhGH therapy at nine years and five months, reached a height of 143 cm (–2.55 SDS WHO) at puberty. Additionally, the substantial economic burden of treatment considerably affected compliance, contributing to suboptimal final height outcomes in some patients. CPHD is classified as an intermediate-risk condition in the two largest multicenter longitudinal studies to date: the NordiNet International Outcome Study (2006–2016, Europe) and the ANSWER Program (2002–2016, USA) [

34]. The most common adverse event in this risk group is edema, which was not observed in our study population. According to the KIGS database, scoliosis is one of the most frequently reported adverse events (0.2%) during rhGH treatment in patients with GH deficiency or other conditions not associated with CPHD [

23]. In our study, scoliosis was observed in only one patient, and this adverse event resolved after treatment resumption

4. Materials and Methods

Six patients from five unrelated families were diagnosed with hypopituitarism based on physical characteristics, biochemical tests, bone age and brain MRI. The reasons for admission varied among the patients. Patients P1 and P2 were siblings. Patient P1 was admitted at 19 months of age due to intellectual disability. Since two months of age, P1 had experienced slow weight gain, excessive sleep, and severe constipation. Following a diagnosis of central hypothyroidism, the family brought P1’s younger brother (P2) for examination, leading to an early diagnosis at two months of age. Patient 3 was admitted to our department at 20 days old with persistent jaundice. Patient P4 sought medical attention at five months old for slow weight gain and persistently elevated liver enzymes of unknown cause. After more than a year of investigation and hepatitis treatment, P4 was diagnosed with central hypothyroidism and GH deficiency. Patient P5 and P6 were admitted to our hospital due to severe short stature and delayed growth.

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood according to the manufacturer's instructions. Exome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis were performed on five probands at the Institute of Genome Research, as previously described [

35]. Pathogenic variants were filtered in genes associated with hypopituitarism [

8]. The pathogenicity of missense variants was assessed using Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT) [

36], Polymorphism Phenotyping v2 (PolyPhen-2) [

37], Mutation Taster [

38], and Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD v1.6) [

39]. To confirm the identified variants, exons 3, 4, and 6 of the

POU1F1 gene were amplified using specifically designed oligonucleotide primers, which are available upon request. The PCR products were sequenced using the 3500 Genetic Analyzer capillary electrophoresis system (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA). The reference sequence for

POU1F1 is NM_000306.4. The effect of variants on the three-dimensional structure of human pituitary-specific positive transcription factor 1 (PIT-1; protein data bank code: 5WC9) was modeled using Swiss-PdbViewer v4.1.0 [

40].

All patients received levothyroxine and rhGH replacement therapy. Levothyroxine treatment began with an initial dose of 5–10 µg/kg/day, and normal thyroid status was typically achieved within 2–4 weeks. Patients were re-evaluated every 6 months, with dose adjustments based on free thyroxine (FT4) levels. GH therapy was initiated with a dose of 25 µg/kg/day, and the rhGH dose was adjusted every 6–12 months based on serum IGF-1 levels and height velocity.

5. Conclusions

Our study identified three pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in the POU1F1 gene associated with combined pituitary hormone deficiency in Vietnamese patients. These findings highlight the critical importance of early hormone testing and genetic analysis to improve the diagnosis, management, and outcomes for patients with combined pituitary hormone deficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H.N. and C.D.V.; methodology, H.T.N., T.M.D., C.D.V.; software, H.T.N., N.V.T. , N.T.X. and N.T.T.; validation, K.N.N., T.M.D. and T.B.N.C.; formal analysis, H.T.N., N.T.K.L., N.V.T., N.T.X., N.T.T., V.K.T. and T.T.C.M.; investigation, H.T.N., K.N.N., T.B.N.C., T.T.N.N., N.T.K.L., N.L.N. and V.A.T.; data curation, K.N.N., T.M.D., T.B.N.C., N.L.N., T.T.C.M., H.H.N. and C.D.V.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.N., T.T.N.N. and N.L.N.; writing—review and editing, H.T.N., N.L.N., V.K.T., T.T.C.M., V.A.T., H.H.N. and C.D.V.; visualization, H.T.N., K.N.N., T.M.D., T.B.N.C., T.T.N.N., N.T.K.L., N.V.T., N.T.X., N.T.T., V.K.T., V.A.T.; supervision, H.H.N. and C.D.V.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology for a Grant number KHCBSS.01/22-24 and for The Excellent research team of Institute of Genome Research Grant number NCXS.01.03/23-25.

Institutional Review Board Statement

: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Vietnam National Children’s Hospital with approval number 1184/BVNTW-HĐĐĐ on 16 May 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patients involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the parents of the patients to involve in the study to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Bosch I Ara, L.; Katugampola, H.; Dattani, M.T. Congenital Hypopituitarism during the Neonatal Period: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Therapeutic Options, and Outcome. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 600962. [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, N.M.; Tadi, P. Physiology, Pituitary Hormones. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing, 2023.

- Majdoub, H.; Amselem, S.; Legendre, M.; Rath, S.; Bercovich, D.; Tenenbaum-Rakover, Y. Extreme Short Stature and Severe Neurological Impairment in a 17-Year-Old Male with Untreated Combined Pituitary Hormone Deficiency Due to POU1F1 Mutation. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Parkin, K.; Kapoor, R.; Bhat, R.; Greenough, A. Genetic Causes of Hypopituitarism. Arch. Med. Sci. 2019, 16, 27–33. [CrossRef]

- Gregory, L.C.; Dattani, M.T. The Molecular Basis of Congenital Hypopituitarism and Related Disorders. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e2103–e2120. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; George, A.S.; Brinkmeier, M.L.; Mortensen, A.H.; Gergics, P.; Cheung, L.Y.M.; Daly, A.Z.; Ajmal, A.; Pérez Millán, M.I.; Ozel, A.B.; et al. Genetics of Combined Pituitary Hormone Deficiency: Roadmap into the Genome Era. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37, 636–675. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Mayer, J.; Vishnopolska, S.; Perticarari, C.; Garcia, L.I.; Hackbartt, M.; Martinez, M.; Zaiat, J.; Jacome-Alvarado, A.; Braslavsky, D.; Keselman, A.; et al. Exome Sequencing Has a High Diagnostic Rate in Sporadic Congenital Hypopituitarism and Reveals Novel Candidate Genes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, dgae320. [CrossRef]

- Bando, H.; Urai, S.; Kanie, K.; Sasaki, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Fukuoka, H.; Iguchi, G.; Camper, S.A. Novel Genes and Variants Associated with Congenital Pituitary Hormone Deficiency in the Era of Next-Generation Sequencing. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1008306. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M. Genetic Causes of Isolated and Combined Pituitary Hormone Deficiency. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 30, 679–691. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.; Pearse, R.V.; Jenne, K.; Sornson, M.; Lin, S.C.; Bartke, A.; Rosenfeld, M.G. The Ames Dwarf Gene Is Required for Pit-1 Gene Activation. Dev. Biol. 1995, 172, 495–503. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, E.M.; Li, P.; Leon-del-Rio, A.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; Aggarwal, A.K. Structure of Pit-1 POU Domain Bound to DNA as a Dimer: Unexpected Arrangement and Flexibility. Genes. Dev. 1997, 11, 198–212. [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.W.; Jue, S.F.; Maurer, R.A. Expression of the Synaptotagmin I Gene Is Enhanced by Binding of the Pituitary-Specific Transcription Factor, POU1F1. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009, 23, 1563–1571. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.; Diwaker, C.; Lila, A.R.; Gada, J.V.; Kale, S.; Sarathi, V.; Thadani, P.M.; Arya, S.; Patil, V.A.; Shah, N.S.; et al. POU1F1 Mutations in Combined Pituitary Hormone Deficiency: Differing Spectrum of Mutations in a Western-Indian Cohort and Systematic Analysis of World Literature. Pituitary. 2021, 24, 657–669. [CrossRef]

- Ayyar, V.S. History of Growth Hormone Therapy. Indian. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 15, S162–S165. [CrossRef]

- Danowitz, M.; Grimberg, A. Clinical Indications for Growth Hormone Therapy. Adv. Pediatr. 2022, 69, 203–217. [CrossRef]

- Besci, Ö.; Deveci Sevim, R.; Yüksek Acinikli, K.; Akın Kağızmanlı, G.; Ersoy, S.; Demir, K.; Ünüvar, T.; Böber, E.; Anık, A.; Abacı, A. Growth Hormone Dosing Estimations Based on Body Weight versus Body Surface Area. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2023, 15, 268–275. [CrossRef]

- Drake, W.M.; Howell, S.J.; Monson, J.P.; Shalet, S.M. Optimizing GH Therapy in Adults and Children. Endocrine. Reviews. 2001, 22, 425–450. [CrossRef]

- Rachmiel, M.; Rota, V.; Atenafu, E.; Daneman, D.; Hamilton, J. Final Height in Children with Idiopathic Growth Hormone Deficiency Treated with a Fixed Dose of Recombinant Growth Hormone. Horm. Res. 2007, 68, 236–243. [CrossRef]

- Grimberg, A.; DiVall, S.A.; Polychronakos, C.; Allen, D.B.; Cohen, L.E.; Quintos, J.B.; Rossi, W.C.; Feudtner, C.; Murad, M.H.; on behalf of the Drug and Therapeutics Committee and Ethics Committee of the Pediatric Endocrine Society Guidelines for Growth Hormone and Insulin-like Growth Factor-I Treatment in Children and Adolescents: Growth Hormone Deficiency, Idiopathic Short Stature, and Primary Insulin-like Growth Factor-I Deficiency. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2016, 86, 361–397. [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.; Fridman, M.; Kelepouris, N.; Murray, K.; Krone, N.; Polak, M.; Rohrer, T.R.; Pietropoli, A.; Lawrence, N.; Backeljauw, P. Factors Associated With Response to Growth Hormone in Pediatric Growth Disorders: Results of a 5-Year Registry Analysis. J Endocr Soc 2023, 7, bvad026. [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.; Lee, P.A.; Gut, R.; Germak, J. Factors Influencing the One- and Two-Year Growth Response in Children Treated with Growth Hormone: Analysis from an Observational Study. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2010, 2010, 494656. [CrossRef]

- Polak, M.; Blair, J.; Kotnik, P.; Pournara, E.; Pedersen, B.T.; Rohrer, T.R. Early Growth Hormone Treatment Start in Childhood Growth Hormone Deficiency Improves near Adult Height: Analysis from NordiNet® International Outcome Study. Eur J Endocrinol 2017, 177, 421–429. [CrossRef]

- Maghnie, M.; Ranke, M.B.; Geffner, M.E.; Vlachopapadopoulou, E.; Ibáñez, L.; Carlsson, M.; Cutfield, W.; Rooman, R.; Gomez, R.; Wajnrajch, M.P.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Pediatric Growth Hormone Therapy: Results from the Full KIGS Cohort. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, 3287–3301. [CrossRef]

- Ranke, M.B.; Lindberg, A.; Tanaka, T.; Camacho-Hübner, C.; Dunger, D.B.; Geffner, M.E. Baseline Characteristics and Gender Differences in Prepubertal Children Treated with Growth Hormone in Europe, USA, and Japan: 25 Years’ KIGS® Experience (1987-2012) and Review. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2017, 87, 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Turton, J.P.G.; Reynaud, R.; Mehta, A.; Torpiano, J.; Saveanu, A.; Woods, K.S.; Tiulpakov, A.; Zdravkovic, V.; Hamilton, J.; Attard-Montalto, S.; et al. Novel Mutations within the POU1F1 Gene Associated with Variable Combined Pituitary Hormone Deficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 4762–4770. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-Y.; Niu, D.-M.; Chen, L.-Z.; Yang, C.-F. Congenital Hypopituitarism Due to Novel Compound Heterozygous POU1F1 Gene Mutation: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2021, 29, 100819. [CrossRef]

- Binder, G.; Weber, K.; Rieflin, N.; Steinruck, L.; Blumenstock, G.; Janzen, N.; Franz, A.R. Diagnosis of Severe Growth Hormone Deficiency in the Newborn. Clin. Endocrinol. 2020, 93, 305–311. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, H.G.; Grumbach, M.M.; Kaplan, S.L. Growth and Growth Hormone. N. Engl. J. Med. 1968, 278, 57–68. [CrossRef]

- Cherella, C.E.; Cohen, L.E. Congenital Hypopituitarism in Neonates. NeoReviews. 2018, 19, e742–e752. [CrossRef]

- Baş, F.; Abalı, Z.Y.; Toksoy, G.; Poyrazoğlu, Ş.; Bundak, R.; Güleç, Ç.; Uyguner, Z.O.; Darendeliler, F. Precocious or Early Puberty in Patients with Combined Pituitary Hormone Deficiency Due to POU1F1 Gene Mutation: Case Report and Review of Possible Mechanisms. Hormones. 2018, 17, 581–588. [CrossRef]

- Ohta, K.; Nobukuni, Y.; Mitsubuchi, H.; Fujimoto, S.; Matsuo, N.; Inagaki, H.; Endo, F.; Matsuda, I. Mutations in the Pit-1 Gene in Children with Combined Pituitary Hormone Deficiency. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992, 189, 851–855. [CrossRef]

- Radovick, S.; Nations, M.; Du, Y.; Berg, L.A.; Weintraub, B.D.; Wondisford, F.E. A Mutation in the POU-Homeodomain of Pit-1 Responsible for Combined Pituitary Hormone Deficiency. Science. 1992, 257, 1115–1118. [CrossRef]

- Darendeliler, F.; Lindberg, A.; Wilton, P. Response to Growth Hormone Treatment in Isolated Growth Hormone Deficiency versus Multiple Pituitary Hormone Deficiency. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2011, 76 Suppl 1, 42–46. [CrossRef]

- Sävendahl, L.; Polak, M.; Backeljauw, P.; Blair, J.C.; Miller, B.S.; Rohrer, T.R.; Hokken-Koelega, A.; Pietropoli, A.; Kelepouris, N.; Ross, J. Long-Term Safety of Growth Hormone Treatment in Childhood: Two Large Observational Studies: NordiNet IOS and ANSWER. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 1728–1741. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.-L.; Thi Bich Ngoc, C.; Dung Vu, C.; Van Tung, N.; Hoang Nguyen, H. A Novel Frameshift PHKA2 Mutation in a Family with Glycogen Storage Disease Type IXa: A First Report in Vietnam and Review of Literature. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2020, 508, 9–15. [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.C.; Henikoff, S. SIFT: Predicting Amino Acid Changes That Affect Protein Function. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2003, 31, 3812–3814. [CrossRef]

- Adzhubei, I.A.; Schmidt, S.; Peshkin, L.; Ramensky, V.E.; Gerasimova, A.; Bork, P.; Kondrashov, A.S.; Sunyaev, S.R. A Method and Server for Predicting Damaging Missense Mutations. Nat. Methods. 2010, 7, 248–249. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, J.M.; Cooper, D.N.; Schuelke, M.; Seelow, D. MutationTaster2: Mutation Prediction for the Deep-Sequencing Age. Nat. Methods. 2014, 11, 361–362. [CrossRef]

- Rentzsch, P.; Schubach, M.; Shendure, J.; Kircher, M. CADD-Splice-Improving Genome-Wide Variant Effect Prediction Using Deep Learning-Derived Splice Scores. Genome. Med. 2021, 13, 31. [CrossRef]

- Guex, N.; Peitsch, M.C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: An Environment for Comparative Protein Modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997, 18, 2714–2723. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).