1. Introduction

Pseudohypoparathyroidism (PHP) is a group of genetic disorders characterized by end-organ resistance to parathyroid hormone (PTH) and often the Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy phenotype (short stature, brachydactyly, subcutaneous ossifications, obesity and developmental delays) with a prevalence of 0.3-1.1 cases per 100,000 population[

1,

2]. The classic form of the disorder is PHP1A, caused by maternally inherited loss of function variants in the gene

GNAS. Most patients with PHP1A will have multiple hormone resistance due to abnormal function of the

GNAS encoded stimulatory G-protein alpha subunit which is utilized by several G-protein coupled hormone receptors.

GNAS is an imprinted gene with preferential expression of the maternal allele in some tissues, including the thyroid, kidney, hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Due to this imprinting phenomenon, paternally inherited loss of function

GNAS variants do not result in hormone resistance and the resulting phenotype is called pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism (PPHP). Alternately, abnormal

GNAS function can be caused by methylation defects at the

GNAS differentially methylated regions (including the gene

STX16) or paternal 20q disomy. These methylation defects are called PHP1B and have a variable phenotype, from isolated PTH resistance to a PHP1A-like phenotype. There is significant clinical overlap between the various forms of PHP.

A European group has recommended a different nomenclature, inactivating PTH/PTHrP signaling disorder (iPPSD)[

3]. Loss of function variants in

GNAS are classified as iPPSD2 and methylation changes in

GNAS are classified as iPPSD3. Tissue specific imprinting of

GNAS in the hypothalamus may lead to different eating behavior phenotypes in maternally inherited (PHP1A) vs. paternally inherited (PPHP) variants, and a previous study showed that patients with PHP1A have significantly higher BMI than patients with PPHP[

4]. For the purposes of this study, we will use the PHP nomenclature (PHP1A, PPHP) as it distinguishes between maternally and paternally inherited variants rather than grouping them into one iPPSD category.

We have previously published two small studies evaluating eating behaviors in PHP1A. The first study included questionnaire data from 10 patients with PHP1A, while the second study included questionnaire and buffet meal data from 16 patients with PHP1A and 3 patients with PHP1B[

5,

6]. Patients with PHP1A had an increased interest in food at a younger age compared to controls, but only a subset of patients had significant hyperphagia. It is not clear if there are other differences between the groups with and without hyperphagia. There are no reports on eating behaviors of patients with PPHP.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate differences in eating behaviors in a large cohort of patients with PHP1A, PPHP and PHP1B. We also compared behavior over time to test the hypothesis that patients with PHP1A have early but non-progressive hyperphagia.

2. Materials and Methods

Data collection was approved by the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board. Cross-sectional data was collected through online surveys and from baseline data in patients enrolled in clinical trials (NCT04551170 and NCT03029429). The longitudinal analysis includes previously published data (PMID 25337124 and PMID 30085125). Pediatric control patient data was collected through the Vanderbilt Childhood Obesity Registry (NCT02957916) which enrolled children with onset of obesity prior to 10 years old. We also included control patient data from the previously published studies (PMID 25337124 and PMID 30085125), if the subject had a BMI >95th percentile for age and gender.

Not all patients with PHP1A/1B had genetic testing available for review. Clinical classification was based on their medical records and self-report. All patients with PPHP had a genetic diagnosis. Height and weight was obtained from medical records when available.

Surveys were administered via REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture)[

7]. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. Height and weight were obtained from the medical record or patient report if records were unavailable (adults only). Pediatric z-scores were calculated as standard deviations from the mean using gender and age specific Centers for Disease Control growth charts. All children had a Hyperphagia Questionnaire (HQ)[

8], Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ)[

9], and Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ) [

10] completed by the primary caregiver. Adults completed the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ)[

11]. Adults enrolled in the clinical trial also completed the HQ.

The HQ was originally developed to assess hyperphagia in Prader-Willi syndrome and contains 11-questions that assess symptoms of hyperphagia in one of three categories (Behavior, Drive and Severity. The 35-item CEBQ assesses Positive and Negative Eating Behaviors. The Positive Eating Behavior score is comprised of four sub-scales: Food Responsiveness, Enjoyment of Food, Emotional Overeating and Desire to Drink. The Negative Eating Behavior score is composed of four sub-scales: Satiety Responsiveness, Slowness in Eating, Emotional Undereating and Food Fussiness. The CFQ assess parental beliefs, attitudes and practices around child feeding. There are seven factors in the CFQ model, Perceived responsibility, Perceived parent weight, Perceived child weight, Concern about child weight, Restriction, Pressure to eat, and Monitoring. The TFEQ contains 51 questions to assess Restraint, Disinhibition and Hunger in adults.

Analysis: Analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 29. Significance was set at a two-sided p-value <0.5. Groups were compared using Kruskal-Wallis test. If this test was significant, each group was compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, adjusted by the Bonferroni correction. For categorical variables, a Chi-square test was used for comparison.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 58 patients with PHP1A, 13 patients with PPHP and 10 patients with PHP1B contributed data (

Table 1), along with 124 obese pediatric controls. Baseline data for the pediatric and adult cohorts are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3. As expected, patients with PHP1A and PPHP have below average height. The degree of obesity was more severe in the control group than the PHP patients. The adult PPHP group was older and female as most were diagnosed later in life after having a child with PHP1A. Two out of four (50%) children with PHP1B were obese, versus 33 out of 35 (94%) children with PHP1A.

3.2. Hyperphagia Questionnaires

3.2.1. Pediatric Hyperphagia

Results from the parent-completed HQ, CEBQ, and CFQ are presented in

Table 4. Parents reported significantly earlier onset of interest in food in children with PHP1A (2.0 ± 2.3 years) and PHP1B (1.1± 1.3 years) compared with controls (5.2 ± 3.2 years, p<0.001). On the CFQ, parents of children with PHP1A also reported greater concern about their child’s weight (4.2 ± 0.8 vs. 3.3 ± 0.4. p< 0.001, score range 1-5). Measures of hyperphagia, satiety and other feeding behaviors were all similar between PHP1A and controls.

There was no difference in HQ Total score, CEBQ Positive Eating Behaviors or CEBQ Negative Eating Behaviors between PHP1A and obese controls after adjusting for age, gender and BMI in a linear regression model. Higher BMI, however, was associated with higher HQ Total score (β 0.24, p= 0.003) and CEBQ Positive Eating Behaviors (β 0.24, p= 0.007) and lower Negative Eating Behaviors (β -0.18, p= 0.05).

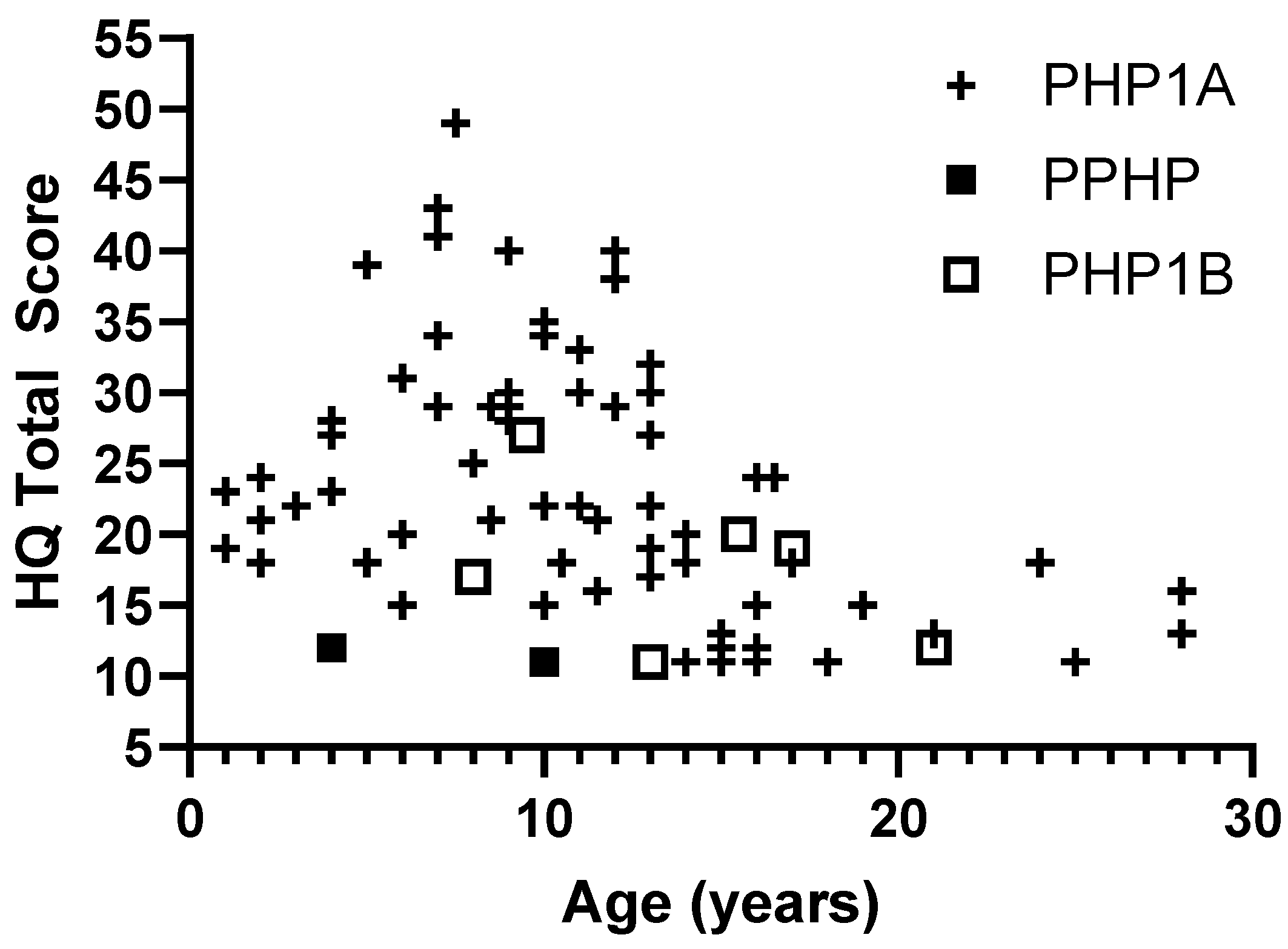

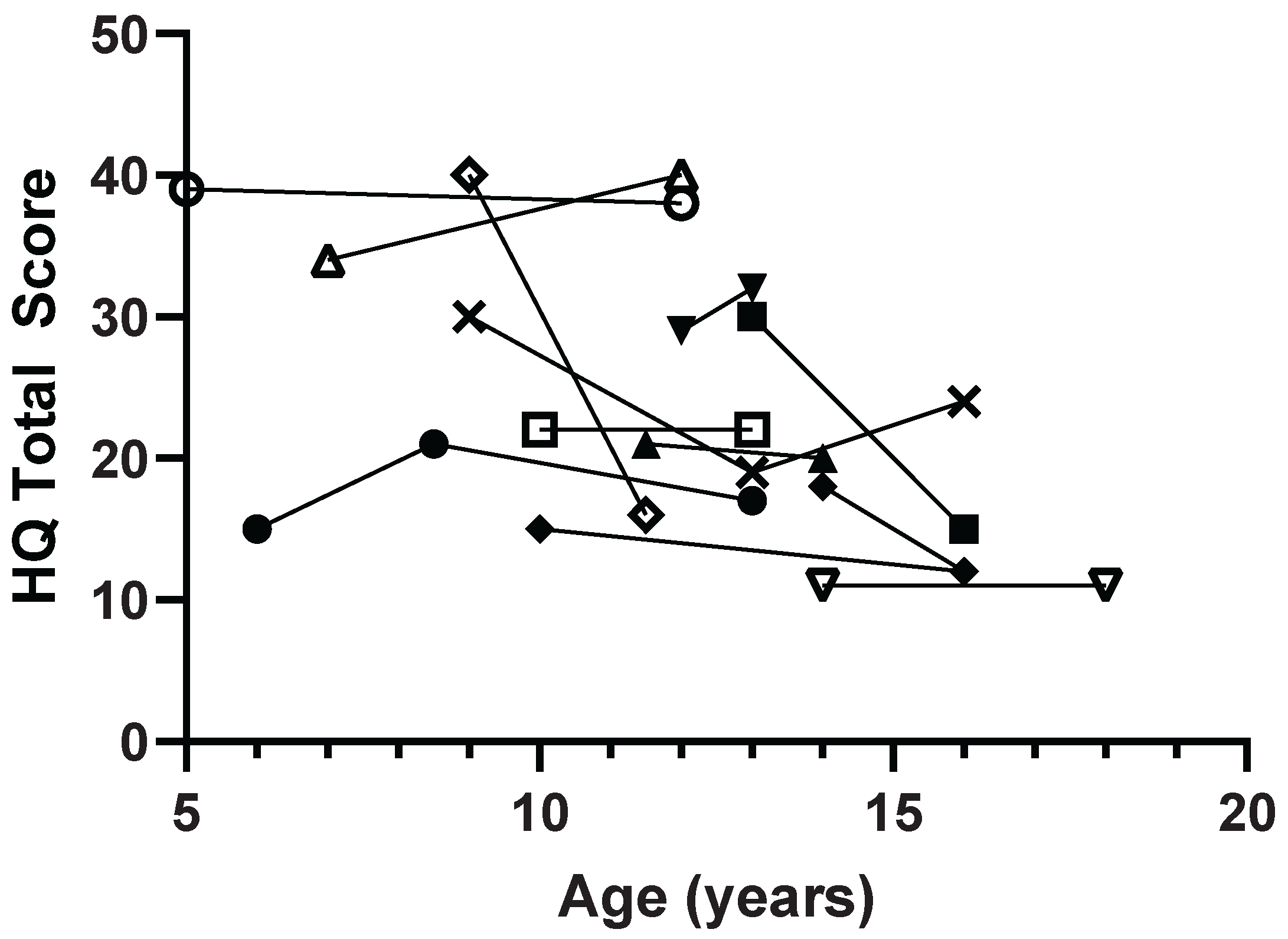

While some patients with PHP1A have high levels of hyperphagia, there was significant variability and no evidence of worsening hyperphagia with age. The highest HQ scores were seen prior to adolescence (

Figure 1). In 12 pediatric patients with multiple measurements over time, most patients had stable HQ scores and 3 patients (25%) showed improvement in symptoms with more than a 10-point decrease in total score (

Figure 2).

3.2.2. Adult Hyperphagia

Adults completed the TFEQ and results are presented in

Table 5. There were no significant differences between groups. Results were similar baseline measurements from other groups with obesity [

12].

4. Discussion

In a large cohort of patients with PHP1A, we found early onset of increased interest in food at an average of 2 years old. Patients with PHP1B showed a similar early onset of increased interest in food, though there were only 4 participants with available data. This correlates with findings early onset obesity, typically beginning in the first 1-2 years of life, in both PHP1A and PHP1B[

13,

14,

15]. While the PHP1B group did include adult and pediatric patients with obesity, the prevalence was lower and the PHP1B group also had non-significantly lower scores on measures of hyperphagia. Phenotypic overlap between PHP1A and PHP1B is increasingly recognized, including the presence of early-onset obesity, but a higher percentage of patients with PHP1A have the classic Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy physical features[

16].

Early-onset obesity in PHP1A is attributed to abnormal function of the melanocortin-4 receptor in the hypothalamus, an area affected by tissue specific imprinting[

13,

17]. Due to the presence of paternal imprinting of

GNAS, patients with PPHP (paternal inheritance) are not expected to have hypothalamic disruption of energy balance. Accordingly, we found lower rates of obesity in adults and children with PPHP, consistent with the previously published study by Long et al [

4]. Despite the lower BMI of the PPHP cohort, the adult PPHP group did not report lower levels of hunger on the TFEQ. The two pediatric PPHP patients did have lower hyperphagia and hunger scores, but a larger cohort is needed. It is also possible that the difference in weight gain in PHP1A vs. PPHP is driven more by differences in basal metabolic rate rather than food intake, but further research is needed on patients with PPHP[

6,

18].

The parent-reported degree of hyperphagia in PHP1A (mean total HQ score 24.2 ± 8.4) was less severe than seen in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome (30.47 ± 4.52), but closer to other causes of syndromic obesity such as Bardet-Biedl syndrome (27.6 ± 9.0) and BDNF haploinsufficiency (26.37 ± 7.32) [

8,

19,

20]. Differences between the PHP groups and controls in our study may have been blunted due to the severity of obesity in our control group, as hyperphagia increased with increasing BMI. Previous obese control groups in studies from our group and others have had HQ total scores ~19 vs. 23.2 in this study. [

6,

19,

20] Of note, the HQ version used in this study has more questions (13 vs. 9) and a different scoring range than the Hyperphagia Questionnaire for Clinical Trials that is currently being used in industry trials so those data cannot be compared[

21].

This is the first study to look at longitudinal data on hyperphagia in PHP. Patients with PHP1A may have hyperphagia symptoms from a young age but they do not worsen over time. This is different from Prader-Willi syndrome where hyperphagia develops over time with increasing severity throughout childhood. Some patients even showed a resolution of symptoms as they aged. Based on this study and our clinical experience with patients, we suspect that people with PHP1A and possibly PHP1B may overeat when allowed access to food, but they do not usually have disruptive food seeking behaviors (HQ behavior subscale). Early diagnosis gives clinicians the opportunity to provide anticipatory diagnosis on the increased risk of obesity and need for scheduled meals and controlled portions. These strategies are helpful in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome, despite much more severe hyperphagic behaviors. The challenge with PHP is to make the diagnosis before the obesity becomes severe. Unfortunately, obesity is still one of the main presenting features of this genetic disorder.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease grant R01DK118407 (Shoemaker), the Doris Duke Foundation (Shoemaker), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Science UL1-TR002243.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University Medical Center (IRB: 170219, approved 3/13/2017) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all adult subjects involved in the study. For subjects less than 18 years of age, informed consent was obtained from their legal guardian and assent was obtained from the subject.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to subject privacy concerns due to rare disease and small sample size.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this paper would like to thank the participants and their families.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PHP |

Pseudohypoparathyroidism |

| PHP1A |

Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1A |

| PHP1B |

Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1B |

| PTH |

Parathyroid hormone |

| PPHP |

pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism |

| iPPSD |

Inactivating PTH/PTHrP signaling disorder |

| HQ |

Hyperphagia questionnaire |

| CEBQ |

Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire |

| CFQ |

Child Feeding Questionnaire |

| TFEQ |

Three Factor Eating Questionnaire |

| LOF |

Loss of function |

| AHO |

Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy Phenotype |

References

- Nakamura, Y. , et al., Prevalence of idiopathic hypoparathyroidism and pseudohypoparathyroidism in Japan. J Epidemiol 2000, 10, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underbjerg, L. , et al., Pseudohypoparathyroidism - epidemiology, mortality and risk of complications. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2015. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, S. , et al., From Pseudohypoparathyroidism to inactivating PTH/PTHrP Signalling Disorder (iPPSD), a novel classification proposed by the European EuroPHP network. Eur J Endocrinol 2016. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, D.N. , et al., Body mass index differences in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a versus pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism may implicate paternal imprinting of Galpha(s) in the development of human obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 92, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L. and A.H. Shoemaker, Eating behaviors in obese children with pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a: a cross-sectional study. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2014, 2014, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perez, K.M. , et al., Glucose Homeostasis and Energy Balance in Children With Pseudohypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018, 103, 4265–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harris, P.A. , et al., Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dykens, E.M. , et al., Assessment of hyperphagia in Prader-Willi syndrome. Obesity 2007, 15, 1816–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, J. , et al., Development of the Children's Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2001, 42, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, L.L. , et al., Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: a measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite 2001, 36, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stunkard, A.J. and S. Messick, The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 1985, 29, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papini, N.M. , et al., Examination of three-factor eating questionnaire subscale scores on weight loss and weight loss maintenance in a clinical intervention. BMC Psychol 2022, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mendes de Oliveira, E. , et al., Obesity-Associated GNAS Mutations and the Melanocortin Pathway. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, P. , et al., Genetic and Epigenetic Defects at the GNAS Locus Lead to Distinct Patterns of Skeletal Growth but Similar Early-Onset Obesity. J Bone Miner Res 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abawi, O. , et al., Genetic Obesity Disorders: Body Mass Index Trajectories and Age of Onset of Obesity Compared with Children with Obesity from the General Population. J Pediatr 2023, 262, 113619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elli, F.M. , et al., Quantitative analysis of methylation defects and correlation with clinical characteristics in patients with Pseudohypoparathyroidism type I and GNAS epigenetic alterations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M. , et al., Central nervous system imprinting of the G protein G(s)alpha and its role in metabolic regulation. Cell Metab 2009, 9, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shoemaker, A.H. , et al., Energy expenditure in obese children with pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a. Int J Obes 2013, 37, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sherafat-Kazemzadeh, R. , et al., Hyperphagia among patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Pediatr Obes 2013, 8, e64–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.C. , et al., Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and obesity in the WAGR syndrome. N Engl J Med 2008, 359, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matesevac, L. , et al., Analysis of Hyperphagia Questionnaire for Clinical Trials (HQ-CT) scores in typically developing individuals and those with Prader-Willi syndrome. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 20573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).