1. Introduction

In France, the estimated prevalence of Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) (DSM-5 [2]; see also [3,4,5])—referred to clinically as dysphasie—ranges from 2% to 3% among school-aged children [1,83,84]. Within this population, expressive DLD, defined by marked impairments in phonological encoding and/or syntactic formulation, accounts for a substantial subset, with approximately 1% of children exhibiting a severe expressive profile [85]. These national estimates are broadly aligned with international prevalence data (e.g., [86,87]), although cross-country comparisons may be influenced by diagnostic heterogeneity and disparities in clinical resources and assessment protocols. As observed in other neurodevelopmental disorders, sex differences are notable, with male-to-female ratios ranging from 2:1 to 3:1 in favor of boys.

A core diagnostic feature of DLD, especially in the expressive form, is the absence of concurrent sensory, cognitive, or psychiatric impairments, which helps isolate the linguistic deficit as the primary domain of dysfunction. Gérard [6] but also Rapin and Allen [4] proposed a tripartite classification of DLD subtypes: (1) expressive DLD, (2) receptive DLD, which involves impaired verbal comprehension with relatively fluent—though often semantically inappropriate—output, and (3) mixed DLD, which combines both expressive and receptive impairments.

Given that expressive DLD is the most prevalent and well-defined subtype, the present study focuses specifically on this profile. Moreover, children with expressive DLD typically exhibit preserved semantic and pragmatic competencies, allowing them to engage meaningfully in experimental paradigms targeting morphosyntactic and phonological processing. This makes them particularly well suited for psycholinguistic investigations into the developmental dynamics of language production and perception.

1.1. Clinical Approach

From a clinical perspective, expressive expressive DLD is defined as a disorder manifesting at least at four levels of linguistic analysis: phonological, lexical, morphological, and syntactic.

At the phonological level, difficulties in producing and processing sounds are frequently documented in psycholinguistic studies ([7,8]). Léonard [9] hypothesized that these difficulties might be due to under-specified phonological representations in people with expressive expressive DLD.

At the lexical level, research converge to show that children with expressive DLD aged 3;9 to 5;8 present a restricted vocabulary in comparison to their typically developing peers ([10,11]). Furthermore, studies have reported that individuals with expressive DLD frequently experience delays and inaccuracies in word recall, in contrast to their typically developing counterparts [12]. As the smaller lexical stock in people with expressive DLD has been widely observed in different languages, it is considered a reliable marker of this language disorder [6].

In addition to the lexicon, syntax and morphology, two further linguistic analysis levels are also affected in individuals diagnosed with expressive DLD ([13,14]. Specifically, individuals with expressive DLD encounter significant challenges in utilising morphology, particularly in the formation of morphologically complex words [15]. Additionally, verbal morphology is frequently disrupted, especially about verbal agreement [16]. At the syntactic level, children with expressive DLD produce few functional words, such as articles and prepositions, which lends a "telegraphic" style to their productions (e.g. "bird in tree") and a dyssyntax, that is, a destructuring of the construction of the sentence ("*On commence plus à avoir place." instead of "On commence à ne plus avoir de place."). In contrast, semantics is preserved, as reported by Leonard [9]. We would like to note that effectively disentangling the respective contributions of phonological and syntactic impairments would likely require the use of a different methodology for measuring the dependent variable—such as electroencephalography (EEG)—which allows for finer temporal resolution of linguistic processing (see Heilbron, Armeni, Schoffelen, Hagoort, & de Lang, 2022 for an overview).

Categorical liaison represents a multifaceted linguistic phenomenon that engages phonological, lexical, morphological, and syntactic processing—domains in which children with expressive DLD commonly exhibit difficulties. For this reason, we selected categorical liaison as a focal point to investigate both the perceptual and productive language capacities of children with expressive DLD.

1.2. Linguistic Perspective

One of the linguistic manifestations of expressive DLD, specifically observed in French pronunciation, is precisely the difficulty in achieving liaison, i.e. the phonological phenomenon of pronouncing the latent consonant of a word if the following word begins with a vowel or a silent "h" ("un arbre", (œ̃n‿aʁbʁ)) [17]. The liaison is categorically obligatory in specific cases where word 1 is syntactically dependent on word 2, i.e. it would not be correct to use the second term without the first:

between a determiner and its initial vowel noun (un, les, des, mon, son, ton, mes, tes, ses) (un‿ours) (a bear);

between a determiner and an adjective (les‿autres enfants) (The other children);

between a clitic pronoun (personal pronouns, en, y) (at) and a verb or vice versa or two clitics (determiners, prepositions) (ils‿ont (they have), je les‿aime (I like/love them), elles‿en ont (they have some), ce dont‿on parle) (what we're talking about);

in the case of postposed personal pronouns (vient‿il ?) (Is he coming?);

in the case of enclitics, i.e. a grammatical morpheme that forms a single accentual unit with the term that precedes it (de quoi parle-t-il ? (What is it about?) dit-il ! (he says!));

in specific fixed expressions and compound words (de temps‿en temps (from time to time), porc‿épic (porcupine), tout‿à fait (quite), en‿avance (in advance)).

The challenge in producing categorical liaisons, as evidenced in both children and adults with expressive DLD, is a subject of particular interest when considered in relation to the fact that such liaisons are generally produced without difficulty from the age of 4 by neurotypical children ([18,19,20,21]). Another characteristic of this language impairment is that it presents an imbalance between production and perception capacities in individuals with expressive DLD. While their production of categorical liaisons in free or semi-guided production tasks is severely impaired, their capacities to detect errors of categorical liaison (i.e. non-realised mandatory liaison) in perception tasks is relatively well preserved, although not as good as neurotypical individuals ([22,23,24]). To the best of our knowledge, no psycholinguistic study has examined this imbalance using both production and perception tasks in the same experimental design with the same population of children at different ages.

As a mandatory requirement, categorical liaison precludes any language production strategy that would involve circumventing a recognised and imposed norm by not producing it. Finally, in contrast to optional liaison (maisbut ilsthey, mais‿ils), obligatory liaison neutralises diachronic, geographical, stylistic, and socio-cultural variables ([25,26,27]). It is important to note that the impossible (illegal) liaison, such as (un/hangar), has been excluded from the scope of this study due to its complexity, which can result in the modification of the underlying meaning of the utterance (e.g., [un savant aveugleadjective]# (a blind scientist); [un savant]# [aveugleverb] (a scientist wich is blind..)).

1.3. Psycholinguistic Models of Categorical Liaison Acquisition

In the psycholinguistic literature, two benchmark models have been proposed to account for the acquisition of categorical liaison in French.

Firstly, the phonological model of Wauquier-Gravelines and Braud [23], which relies on the speaker's “innate” knowledge of the phonological structure of their language. This model hypothesises that the language learner stores all possible word variations with or without a liaison, e.g., "friend, des [z]amis, un [n]ami, petit [p]etit ami".

In contrast, the constructionist model proposed by Chevrot, Dugua and Fayol [28] is predicated on the assumption that the child assimilates word sequences consisting of different elements, such as a determiner and a noun. Initially, the child gradually extracts patterns from frequently heard categorical liaisons. Taking the example of the word /ami/ in different contexts, the child associates the plural with the pronunciation of the liaison consonant [z] ([z]amis) and the singular with the liaison consonant [n] (un [n]ami). Secondly, the extraction of regularities will lead to the implementation of a generalization procedure which will enable the child to apply these rules (e.g., [DETERMINANT - z - [vowel] - NAME] in the plural or DETERMINANT - n - [vowel] - NAME] in the singular) to any liaison without necessarily having heard it beforehand.

It is important to note that individuals diagnosed with expressive DLD do not systematically link the two words involved in this juncture phenomenon to form a single phonologically perceptible word. This is even the case when the liaison is categorical (obligatory), for example between a determiner and its initial vowel noun (un, les, des, mon, son, ton, mes, tes, ses) (un‿ours) ([22,24,29]). The linguistic behaviour of people diagnosed with expressive DLD differs from that observed in typically developing individuals. The latter have automated their production based on the obligatory use of the noun with a determiner, the particularity of the categorial liaison and the very high frequency of certain syntagms.

Consequently, the categorial liaison constitutes a powerful model for investigating language production in children diagnosed with phonological-syntactic expressive DLD, due to the absence of some of the automatisms usually observed in typically developing individuals from an early age. In order to gain a more profound understanding of the cognitive processes that underpin the processing and production of obligatory liaisons, and the dysfunctions associated with them in children with phonological-syntactic expressive DLD, the present study has focused on the frequency and persistence of the omission error. That is to say, the absence of a liaison where one is compulsory.

1.4. Dysfunction of Certain Memory Systems as a Possible Cause of DLD

Several cognitive theories have been proposed to explain DLD), particularly expressive forms. One influential hypothesis attributes the disorder to deficits in working memory, specifically the phonological loop ([30,31,34]). This system supports temporary storage and rehearsal of auditory-verbal information and is thought to underlie difficulties in word learning, pseudoword repetition, and lexical access in children with DLD ([33,36,37]).

In addition, Ullman and colleagues ([45,57]) have proposed that procedural memory—responsible for implicit learning of rule-based sequences, including grammar and motor skills—is impaired in DLD, while declarative memory remains relatively intact and compensatory. Neuroimaging evidence supports this dissociation, linking procedural deficits to basal ganglia dysfunction ([53]) and highlighting preserved declarative mechanisms involving the hippocampus and related cortical regions ( [51]).

The Procedural Deficit Hypothesis (PDH) provides a unifying framework for understanding language impairments in DLD, including difficulties with morphosyntax, rule-based sequencing, and implicit learning ([45]). However, whether this framework fully accounts for the acquisition of complex linguistic phenomena such as French categorical liaison remains an open question. As suggested by Chevrot et al. [24] and Wauquier [20], mastering liaison involves both phonological and syntactic processes, and its acquisition may be particularly sensitive to memory-related deficits.

The present study aims to address this gap by examining (1) the role of working memory in the production of French categorical liaison and (2) how the developmental imbalance between processing and production of liaison evolves between ages 6 and 10 in children with expressive DLD.

To this end, 24 children with expressive DLD and 22 neurotypical children of different ages between 6 and 10 were tested using verbal and non-verbal tests adapted to the language skills of children with expressive DLD. Furthermore, and this constitutes an additional innovative facet of our study, we investigated the extent to which the working memory and inhibition skills of children with expressive DLD could modulate their performance in producing and detecting the categorical liaison. To comprehend the asymmetry of omission error curves between perception and production of categorical liaison, we draw on explanatory hypotheses: 1) Ullman and colleagues [45] asserts that lexical inhibition appeals to declarative memory, which compensates for the failure of procedural memory; 2) resistance to distractor interference is a function that protects the relevant contents of working memory from the influence of irrelevant, but interfering external stimuli that can distort or disrupt them ([69]; 3) the interaction between inhibition and morphological processing (procedural memory) is stronger than that between inhibition and receptive vocabulary (declarative memory) ([70]). This will allow us to test the hypothesis that one of the possible causes of expressive DLD is impaired working memory and inhibitory control to refrain from using the canonical form.

To the best of our knowledge, no psycholinguistic study has examined the developmental dissociation between perception and production of categorical liaison in oral language among French-speaking children diagnosed with expressive DLD, encompassing both readers and pre-readers. The present study sought to address this gap by examining both the production and perception of categorical liaisons within a unified experimental framework, in a cohort of 46 French-speaking children aged 6 to 10, including 24 diagnosed with expressive DLD. It has been undertaken to examine the categorical liaison in linguistics, given its multifaceted nature as a research object due to its varied status, encompassing lexical, phonological, and morphological aspects. The categorical liaison is also susceptible to four distinct types of error: (1) addition (i.e. insertion of a variant in a pattern that does not induce any liaison, "la nabeille"), (2) substitution (i.e. replacement of an expected liaison consonant by another, "les namis"), (3) omission (i.e. absence of a liaison in a pattern that induces a liaison, "un / ours"), and (4) regularization (i.e. erroneous assimilation of patterns, production of "le nombril, les ombrils"). These errors can be used as quantitative variables in statistical analyses. As previously stated, the categorical liaison is acquired systematically and early in neurotypical children (at approximately the age of 4; [18,19,20]). Consequently, the non-implementation of this liaison by children over 4 years of age serves as an effective linguistic marker of the risk of developing impaired language.

1.5. Rationale and Aim of This Research

The objective of this research endeavour was to enhance the comprehension of language impairment in children diagnosed with phonological-syntactic expressive DLD who encounter the categorical liaison in French. The present study focuses on the frequency and persistence of the omission error, defined as the failure to make the liaison despite its obligatory nature, contingent on the linguistic context in which the liaison is anticipated and the lexical frequency of the words to which the liaison is applied. The objective was to ascertain the extent to which these errors of omission persist during language development between the ages of 6 and 10, depending on the incremental size of the context in which the liaison is produced (i.e. word, pseudoword, nominal phrase, sentence) and the children's working memory and inhibitory control skills.

A methodological approach was adopted that covers the developmental period from 6 to 10 years of age. The cohort has been divided into two groups, designated as pre-readers (6/7-year-olds) and readers (8/10-year-olds), for the purpose of studying the impact of reading. The acquisition of literacy is accompanied by the assimilation of the liaison consonant, which is always represented graphically ("il a beaucoup osé/il a beaucoup posé ; il est trop heureux/il est trop peureux"). The age range selected for this study was constrained by the clinical profile of expressive DLD. One of the most common diagnostic markers of expressive DLD is the presence of early mutism, typically observed in affected children up to the age of 5 or 6. As noted by Dugua (2015), typically developing children demonstrate mastery of determiner–noun categorical liaisons in natural speech from the age of 3, and between 4 and 6 years in structured naming tasks. We set the upper age limit at 10 years to avoid introducing potential confounds related to the impact of reading and writing acquisition, which may vary widely in children with expressive DLD.

In the present study, the methodology employed was inspired by the tasks utilised in prior research conducted by [72]. The tasks encompassed a combination of production tasks (n = 5) and perception tasks (n = 2). The production tasks were designed to vary in terms of imposed, semi-directed and spontaneous production, frequency of use, word length and lexicality. The perception tasks were designed to vary in terms of frequency of use and word length. The objective of this approach was to propose a series of seven new linguistic tests. The use of novel tests, albeit derived from extant tests in the literature, may consequently engender methodological critiques. However, the decision was taken to employ this methodology with the specific objective of adapting existing tests for children with expressive DLD. This was achieved by inserting images to facilitate the working memory task and by using short sentences, monosyllabic and plurisyllabic words that were easy to pronounce and semantically simple. We deliberately selected tasks that were easy to administer, minimally intrusive, and low in demands on participants' time and attention. Moreover, they can be conducted by speech-language therapists without the need for specialized equipment. Despite these advantages, such an approach has not yet been operationalized due to the lack of validated tools.

Furthermore, we varied the presentation of the liaison, incorporating it in a range of activities including naming, counting and a guessing game. This approach was adopted to preserve the spontaneity of the participants and avoid any awareness of the research purpose. Furthermore, a working memory test was administered, which included the number span task as described by Miller [73], and a selective attention test, which was the Flanker test as described by [74]. To our knowledge, there is currently no standardized norm for the Flanker task specifically for French-speaking children aged 6 to 10 years diagnosed with expressive DLD. However, the Flanker task is widely used as a measure of inhibition or attentional control in school-aged children, including those with language disorders [74]. Its results must, however, be interpreted with caution—either in relation to general population norms or, as in our study, through comparison with a matched control group of typically developing children.

1.6. Predictions

In contrast to neurotypical children, the production of the canonical form, i.e. the unrealised categorical liaison ("un / élève" [œ̃ elɛv] instead of "un‿élève" [œ̃nelɛv]), should persist in children with expressive DLD, irrespective of progress in the mastery of categorial liaison and regardless of age and degree of expressive DLD impairment. This persistent production of the canonical form instead of the expected categorical liaison in children with expressive DLD is hypothesised to be modulated by working memory and inhibitory control capacities. The better these executive capacities are, the less the canonical form is produced

With regard to receptive skills, performance in detecting unrealised categorical liaisons should be preserved in children with expressive DLD, although this should not be to the same level as that demonstrated by neurotypical peers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 24 participants diagnosed with expressive DLD (17 male and 7 female, confirming the prevalence of this disorder in the male population) and 22 neurotypical children (14 male and 8 female), all native speakers of French, aged between 6 and 10 years, were included in the study. The distribution of participants at each age is displayed in

Table 1 for both groups of children.

2.1.1. Children with Expressive DLD

A total of twenty-four children, ranging in age from 6 to 10 years, have been diagnosed with expressive DLD. The children are registered with the Maison Départementale des Personnes Handicapées (MDPH - Departmental House for the Disabled) of the Bas Rhin (69) and Val d'Oise (95) departments in France. The 24 children who were recruited to the study had no other declared pathology. All of them were enrolled in two ULIS (Unités Localisées pour l'Inclusion Scolaire, Local Units for School Inclusion) schemes, which enable pupils with disabilities to attend mainstream schools. The level of education of the children with expressive DLD was difficult to assess accurately due to the inclusive schooling and the special needs of the children. However, on average, they are generally two to three years behind the expected school level for their age. As previously stated, the linguistic impairments experienced by children with expressive DLD encompass difficulties with sounds (e.g. discrimination, manipulation, syllable alteration), reduced lexicon, agrammatism and dyssyntaxia, which collectively impair oral expression, reading and written production. It is noteworthy that the skills of children with expressive DLD exhibit significant inter-individual variability due to the heterogeneity of their abilities.

2.1.2. Neurotypical Children

The twenty-two neurotypical children who made up the control group were also selected from state schools in the Hauts de Seine (92) and Val d’Oise (95) departments in France, with the aim of achieving a similar distribution of participants in the control group as in the dysphasic group. The selection was made in agreement with the teachers, and the children had the expected school level, with no difficulties in either French or mathematics. None of them had repeated or skipped a grade. Prior to participation in the study, the parents were informed individually of the objectives of the study, as well as of the experimental protocol and the procedure for storing and anonymising the data. They then gave their written consent. The data collected was anonymised by applying the European Data FAIR principle [75] in collaboration with the HumaNum TGIR (

https://www.huma-num.fr) for experimental data management. Data processing was carried out in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation

1 of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS). The study was approved by the local ethics committee of University Paris Nanterre and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

2.2. Experimental Materials: Verbal and Non-Verbal Tests

A series of nine verbal and one non-verbal tests were administered, encompassing a range of tasks from reading a list of words to reading a text, from guided conversation to a free interview.

Table 2 displays a summary of these tests.

The verbal tests of perception consisted of two tasks. In the first task, the child was asked to repeat the only one of three spoken variations of a nominal phrase composed of a determiner and a noun, with a change in the liaison (Test 1). Six items were presented. The same modality was used for a 12-item exercise constructed with subject-verb-determiner-noun/logatom (pseudoword) sentences (Test 2). In the perception tasks, omission errors are deliberately inserted to assess the child's ability to recognise the omission as an error or a correct formulation.

The verbal tests of production comprised two denomination tests that were adapted from previous studies ([22,28,72]). The child was presented with an image and was required to state the element and the number of representatives of that element they could see. In order to vary the measurement methods, the following modifications were made: 1) A counting exercise was supported by an illustration with the aim of attenuating the impact of anomia and word confusion, and minimising the task in working memory; 2) A series of five riddles was used to stimulate spontaneity and to reinforce the determiner/name liaison; 3) A story to be told based on six drawings required the use of nouns beginning with a vowel to be repeated several times, playing on the number.

Figure 1 presents a series of six drawings used to encourage children to produce categorical liaisons.

The utilisation of concise sentences, monosyllabic and plurisyllabic words that were straightforward to pronounce and semantically uncomplicated ensured the comprehensibility of the material. The liaison was presented in a variety of ways, ranging from naming to counting to a guessing game, in order to preserve the spontaneity of the participants and avoid any awareness of the research purpose. The context of production was semi-directed or spontaneous. The words used in the verbal tests were selected in Open Lexicon ([76]) and all had a high frequency of occurrence. The participants performed a memory span exercise to test immediate memory and a reverse span exercise to test working memory.

2.3. Procedure

The administration of the tests was conducted by teachers and speech therapists who were regularly engaged with the children, thereby ensuring that the method was neither intrusive nor disturbed by an assessment situation that could alter the spontaneous nature of the responses. Indeed, the speech and language therapy report of two of the children with expressive DLD expresses a very marked fear of assessment situations and a refusal of any assessment situation. It was determined that a playful approach alone was insufficient to instill confidence in a child with expressive DLD, who often find themselves in evaluation situations. The test was administered during a session or after class and lasted between 20 and 30 minutes. The children were not informed of the liaison, yet they were aware that their responses were being recorded. The transcribed recordings were then analysed for the purpose of data collection and analysis.

2.4. Data Analysis

Due to the heterogeneity of the age distribution, the level of impairment of the participants with expressive DLD and the size of the sample (less than 30 participants), we chose to use the non-parametric inferential Mann-Withney test (MW; [77]) using JASP software (

http://www.jasp-stats.org); [78]). A total of 78 categorical liaisons were expected, including 18 for the perceptual tests. Responses were categorised as correct or incorrect. In perception, an error of omission is when the child accepts as correct the form without a liaison, when the liaison is required. In production, an error of omission is characterised by the absence of a categorical liaison when the liaison is required. The dependent variables were the different types of scores expressed as percentages. In order to validate the score for the memory span exercises, it is necessary to complete two exercises with the same number of items. The score used is the last number of digits returned on the last correct trial.

Selective attention, as measured by the Flanker Test, was calculated as the percentage of correct arrow direction choices for twenty screen presentations. The reaction time to select the correct arrow on the keyboard after each new presentation was expressed in milliseconds.

3. Results

For statistical reporting, not significant (ns) = p > 0.10; marginal (mg) = 0.05 < p < 0.10; 0.01 < p*< 0.05; 0.001 < p** < 0.01; p*** < 0.001.

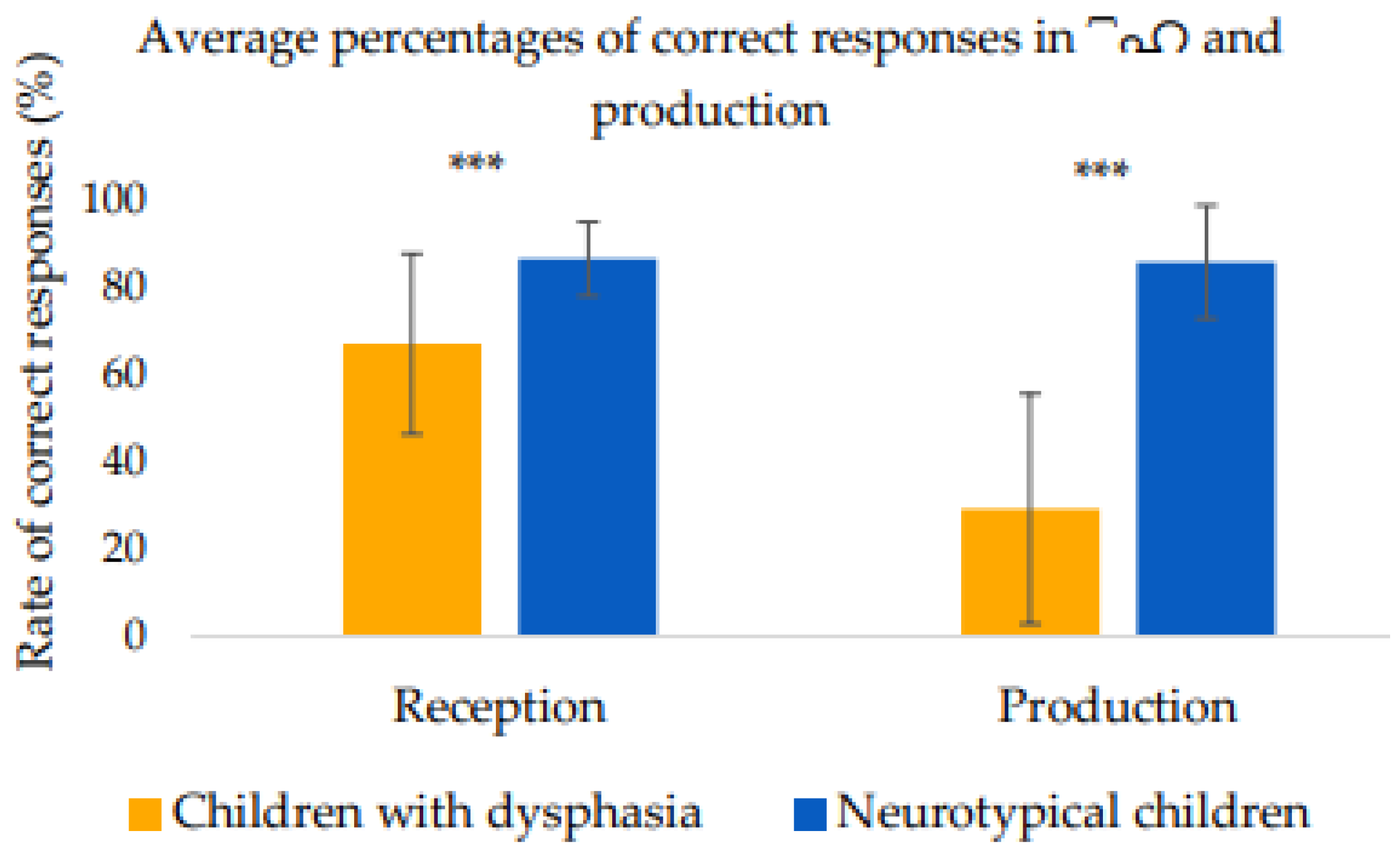

3.1. Average Percentages of Correct Responses in Perception and Production

On average, the children with expressive DLD produced fewer categorical liaisons (M = 29.3%; SD = 26.4) than those of the control group (M = 85.9%; SD = 13). A Mann-Whitney U-Test showed that this difference was statistically significant (U=504.00, p < 0.001, r = 0.9). The effect size (56.6%) is large (r = 0.9 > 0.5). The Mann-Whitney U-Test also indicated a significant difference in the percentage of correct perception of the categorical liaison between children with expressive DLD and neurotypical children (U = 446.00, p < 0.001; r = 0.7).

This effect indicates that the average perception rate was significantly smaller in the dysphasic group (M = 67.1%; SD = 20.7) than in the control one (M = 86.6%; SD = 8.5). The effect is large (19.5%; r=0.7 > 0.5).

Figure 2 displays the average percentages of correct responses in perception and production.

3.2. Comparison Between Children with Expressive DLD and Neurotypical Children’s Pre-Readers and Readers

The groups were divided up according to age, which corresponds to the age at which children acquire reading skills.

Table 3 presents the means and the standard deviations of correct perception and production of categorical liaisons for both pre-readers and readers with expressive DLD and neurotypical children.

The children with expressive DLD produced significantly fewer correct categorical liaisons (M = 17.6%, SD = 13.1%) than neurotypical children in the control group (M = 80.5%, SD = 14.0%). The size of the effect is 62.9% (MW = 72.000; p < 0.001). Contrastively, in perception, the main effect of Group was only marginally significant (MW = 54,000; p = 0.082), indicating that the children with expressive DLD performed as well as the neurotypical children.

While the perception performances did not significantly differ between the two groups (MW = 183.000; p < .001), the average percentage of correct production was significantly lower in the dysphasic group (M = 36.4%, SD = 30.0%) than in the control one (M = 89.0%, SD = 11.8%). The size effect is 52.6% (MW = 198.500; p < 0.001).

Finally, the readers with expressive DLD did not produce a significantly higher number of correct categorical liaisons (M= 36.4%; SD= 30.0%) than the pre-readers with expressive DLD (M= 17.6%; SD= 13.1%) (p > 0.10).

3.4. Correlation Between Perception and Production Tests

The correlation between the rate of categorical liaison’s perception and the rate of categorical liaison’s production was significant (r = 0.7; p <0.001). This correlation was stronger in neurotypical children (r = 0.6; p = 0.008) than in children with expressive DLD (r = 0.5; p = 0.018).

3.5. Omission Error Rate Variations

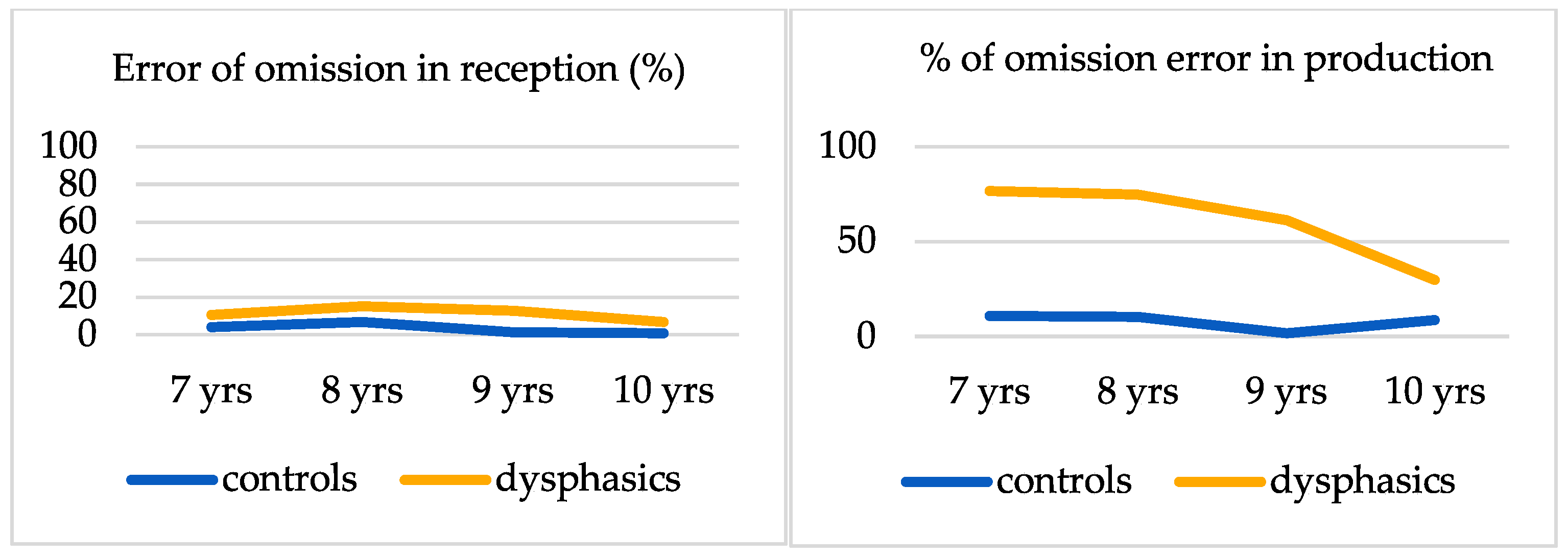

As a reminder, in perception an error of omission is the acceptance of the form as correct without a liaison when the liaison is required. In production, an error of omission is the absence of a categorical liaison when the liaison is required.

Figure 3 displays the average errors of omission in the perception and production of the categorical liaison for both children with expressive DLD and neurotypical children. In perception, the Mann-Withney U-test showed that the average percentage of forms judged correct when the mandatory liaison is omitted was significantly higher in children with expressive DLD (M = 23.51%; SD = 12%) than in neurotypical children (M = 7.57%; SD = 13%) (MW = 85.00, p < 0.001).

In production, the average error of omission’s percentage was significantly higher in children with expressive DLD (M = 63.11%; SD = 25.96%) than in children without expressive DLD (M = 9,75%; SD = 12.3%) (MW = 18.50, p < 0.001, r=0.93 > 0.5).

3.5. Correlation Between Memory Span, Reverse Span and Production of the Categorical Liaison

The relationship between memory span and the rate of correct production of the categorical liaison calculated on all children with and without expressive DLD was significant (r = 0.6; p < 0.001). This correlation means that the higher the memory span score, the higher the rate of correct production of the categorical liaison. Similarly, the relationship between the reverse span and the rate of correct production of the categorical liaison was also significant (r = 0.4; p = 0.003). The more children were able to repeat long sequences of numbers backwards, the better their production of categorical liaisons.

3.6. Correlations Between Flanker Task Scores and Perception and Production Scores

Table 4 summarizes the correlations between the Flanker task scores perception and production scores for all children and for children with expressive DLD respectively.

4. Discussion

The present findings are consistent with extant literature ([28,29,79], as they demonstrate that by the age of six, typically developing children have mastered the production and processing of categorical liaison in French across a range of linguistic contexts. However, it is important to note that the success rate in production never reaches the expected 100%. On the other hand, children with expressive DLD showed relatively good sensitivity to categorical liaison at perception, albeit with lower scores (67.1%) compared to neurotypical children (86.6%). This finding suggests that phonological information regarding categorical liaison is represented in the lexicon of children with expressive DLD, thereby effectively ruling out the hypothesis of a perceptual deficit as the underlying cause of expressive DLD. We will return later to the reasons why children with expressive DLD do not achieve the same processing performance as neurotypical children, at least between the ages of 6 and 10.

In the production tests, significant differences between the groups were observed, with neurotypical children demonstrating significant superior performance in comparison to their counterparts with expressive DLD. This finding aligns with the conclusions drawn in earlier studies [22,23,24]. A salient finding of the present study is that the perception and production performance of categorical liaison in children with expressive DLD does not vary significantly with age.

Furthermore, an analysis of error rates in children with expressive DLD reveals a variation of the rate between the four possible errors, with a predominance of errors of omission in production (that is to say, they do not systematically make the categorical liaison). These results, which have previously been observed in other studies ([22,23,24,72]), raise the question of why children with expressive DLD, in contrast to control groups, experience significant difficulty in producing categorical liaisons, despite their ability to perceive them in a manner comparable to neurotypical children.

The data presented here gives rise to further questions concerning the persistence of error of omission during the development of children with expressive DLD, despite an increase in their linguistic experience. It is also noteworthy that, by virtue of the nature of the omission error, children with expressive DLD do not exhibit difficulties in word segmentation. The study's findings indicate that the rate of omission error does not demonstrate variation as a function of learning to read, nor because of the oralisation of the graphic isolation of the word by white spaces.

In 2005, Wauquier [29] proposed that the correlation between omission error and word length could be linked to working memory limitations. This suggests that while short and frequent words could be correctly produced in a context of categorical liaison (« les ours [lezuʁs] »), longer and infrequent words (even pseudowords) could suffer more from omission of categorical liaison (« les ingénieurs [lezɛ̃ʒenjœʁ] »). A strong significant correlation was observed between span test scores and production performances of categorical liaison, thereby establishing a link between production and short-term memory. However, our results did not confirm Wauquier's hypothesis on item length. In fact, children with expressive DLD do not produce the categorical liaison more correctly with short words than with long words whether in a noun phrase or a sentence.

Dugua and Chevrot [79] propose an alternative interpretation to that of Wauquier in terms of working memory capacity in relation to word length. According to these authors, the omission error in production could be due to the absence of an available schema, and that when producing categorical liaison, the child fails to activate these constructional schemas. The present study confirms that the transition from lexical chunks to the abstract structure of a schema does not occur in children with expressive DLD as it does in neurotypical children. This finding aligns with Ullman and Pierpont's observations of a procedural memory deficit [57]. The results of our study demonstrate that the frequency effect is insufficient to trigger an automated, reduced but accurate and stable language. In fact, the frequency of occurrence does not appear to result in any automatic formulation with systematic use of the correct form. Similarly, the frequency of type does not give rise to any constructional pattern, even if erroneous, that could transform the type from an error of omission to an error of addition or substitution.

The hypothesis that declarative memory compensates for the dysfunction of procedural memory during the production of the categorical liaison has been postulated. Children with expressive DLD exhibit an absence of a stable lexical and grammatical base. The random use of the error of omission and its entrenchment also pointed us in the direction of executive functions, particularly inhibitory control, and we identified the impact of this control in several tasks and production modalities. We tested whether the liaison phenomenon, which leads to resyllabification, was resistant to the automation of the recitation of the numerical chain and administered the Flanker task. However, the involvement of immediate memory in the explanatory model of phonological-syntactic expressive DLD prompted further investigation into the analysis of omission errors.

The children's use of an illegal lexical form, devoid of the categorical liaison, is particularly intriguing when considering that the correct form, which involves linking the article and the noun in the case of the categorical liaison, is typically acquired by children without language disorders from the age of 4 years. This study puts forward the hypothesis that a failure to construct, utilise or modify a schema that initially excludes the categorical liaison in the lexical register during the early stages of language acquisition may underlie this dysfunction. The hypothesis is that the persistence of this failure to account for the categorical liaison in children with expressive DLD may be attributable to procedural memory difficulties. However, the present hypothesis does not yet take into account the difficulty of eliminating or at least reducing the use of the canonical form, in addition to other manifestations such as anomia, automatic-voluntary dissociation, semantic paraphasia and semantic competition. The persistence of this failure to take account of the categorical liaison in children with expressive DLD is the reason for the focus of our research on the inhibition of canonical form embedding and on short-term memory, the gateway to long-term memory, in order to understand the origin of the dysfunction.

Statistically, our results show a disturbance in immediate memory, which raises the question of whether children with expressive DLD process the information they receive in the same way as neurotypical children. We thus agree with Wauquier's hypothesis about children with expressive DLD based on a weakness in working memory [29]. However, we hypothesize that the perceived information may already be retained in canonical form, following the dysfunction of immediate memory and the failure of inhibitory control, and not in the form of distorted or suppressed items. Deletion would take place on the first syllables, i.e. the determiner, and thus the link, preserving the semantics. This partial retention could hinder the construction of a correct schema in procedural memory, due to the lack of elements to compete with and the acceptance of an incorrect form by inhibitory control. On the other hand, performance in perception is higher than in production, which could be explained on the one hand by the attention enforced by the question and the declarative memory support, and on the other hand by the fact that encoded elements can be inhibited so that they cannot be retrieved but can be recognised ([80]).

However, our research into the causes of expressive DLD goes beyond working memory and tends to be based on the constructionist model in neurotypical children. In fact, the dysfunctions observed in children with expressive DLD are as many locks as possible at each stage of the model, highlighting the process of acquiring the categorical liaison expected in neurotypical children. Short-term memory is less able to select examples, and perception is slightly worse in children with expressive DLD than in controls. The input, which is essential for the perception of the association between determiner and noun, is not properly filtered to provide a sufficiently large sample for generalisation. The frequency effect of type and occurrence does not allow elements to be reorganised into a pattern of construction, and inhibitory control distorts the competition between two constructions in favour of the canonical form. It can thus be concluded that the frequency-based model of schema construction is virtually impossible to apply to children with expressive DLD. The typical errors made by children with expressive DLD in categorical liaison, and their development, all reflect the failure of cognitive gearing.

It has been established that inhibitory performance undergoes an enhancement with age ([81,82]). Nevertheless, due to the limited size of the samples utilised, it has not been possible to analyse this development by age group and compare the degree of development of dysphasic children with that of neurotypical children. Nevertheless, the findings from this modest sample suggest that, despite their slower reaction time, children with expressive DLD demonstrate poorer performance on the flanker task. This observation lends support to our hypothesis concerning the role of inhibitory control and aligns with the conclusions reported by Larson et al. [70]. However, due to the limited size of our sample, we are unable to make any definitive conclusions regarding a potential discrepancy in processing speed between children with expressive DLD and their age-matched neurotypical counterparts. Nevertheless, we can ascertain that inhibition in children with expressive DLD is not impaired, nor impulsive, nor too weak to interact.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

In order to ascertain the robustness of the hypotheses under investigation, it would be necessary to extend the cohort under study to include older children and adults. A larger cohort of participants would allow for more robust statistical analyses, such as MANOVA, linear mixed-effects models, or hierarchical regression approaches. Furthermore, in order to precise our results, it would be necessary to integrate additional tests of inhibitory control and procedural memory at both the language and motor levels. Research into language disorders tends to focus on verbal morphology; however, other linguistic features in which errors persist also require exploration.

5. Conclusions

Phonological-syntactic expressive DLD is a recognised language disorder. Although there is no consensus as to its origin, a failure of working memory is widely accepted as an explanation. However, working memory alone does not cause the motor dysfunction and the arbitrary nature of the pathology's manifestations. In view of these factors, the declarative-procedural model presented by Ullman [54] seemed to us to be a more relevant approach. Indeed, Ullman describes a phenomenon of compensation of the procedural memory deficit by the declarative system in individuals with a language disorder. However, omission, anomia and persistence of errors provided the framework for our topic. Anomia offered too broad a field of investigation, as lexical development depends on too many factors. The study of the omission of grammatical and gender agreements at the level of flexional morphology, with random conjugations, required a population already at an advanced stage of language development. We chose to analyse the processing of the categorical liaison in people with phonological-syntactic expressive DLD because the phenomenon of omission is present from the very first language constructions. A stabilisation of the Sandhi phenomenon is never achieved, and its correct use remains uncertain, even if improvements are noted.

This research on categorical liaison supports Ullman's model by implementing it in the context of a "purely" cognitive phenomenon, but it also extends this approach to include the role of other executive functions and memory systems. The resulting model thus tends to revise the phonological-syntactic origin of expressive DLD proposed in current research. We have focused on the distribution of hypothetical weak points in brain mapping, which are no longer restricted to area 44, Broca's area. However, localisation does not explain the functioning of one part of the system, nor the interaction between all the parts. The failure of working memory seems to play a role in the emergence of expressive DLD, but short-term memory and inhibition could also play a crucial role in this dysfunction, with certain consequences identified for procedural memory. The involvement and interplay of multiple factors weakens the entire cognitive system and could explain the severity and inter-individual variation of the pathology better than two competing cognitive components, namely procedural and declarative memory. It would also ensure that brain plasticity is constantly evolving with age and environment. Following the work of Marton ([69,70]) with 30 children with expressive DLD, using standardised language measures and the Flanker Test, found a predictive correlation between inhibition and morphological comprehension in children with expressive DLD. We hope to go further and intervene earlier. We have highlighted the joint role of short-term memory and inhibition in the dysfunction of categorical linking. The predictive correlation between short-term memory and inhibition may make it possible to intervene at the very beginning of language development, without waiting for the development of morphological comprehension to limit the effects of the pathology.

We were fully aware of the methodological limitations associated with the measurement instruments employed in this study. Our primary objective was to assess both the perception and production abilities related to categorical liaison in French across a range of linguistic contexts—including words, pseudowords, noun phrases, and sentences. However, we faced a significant challenge: the current lack of standardized experimental or clinical paradigms in French specifically designed to evaluate this linguistic phenomenon. To the best of our knowledge, no validated tools currently exist that assess the performance of obligatory liaisons at the word, phrase, sentence, or text level in children.

In France, several standardized tools are available to speech-language pathologists for the diagnosis of DLD, including the EVALEO 6–15 [89], Exalang 5–8 [91], Exalang 8–11 [92], and the French adaptation of the CELF-5 [93]. While these comprehensive batteries assess a range of oral language abilities, they are not specifically designed to evaluate categorical liaison. As such, they tend to capture broader neurodevelopmental profiles and may overlook more fine-grained deficits in morphophonological processing, such as those involved in the obligatory production of liaison in French."

Our intent with this study is to provide an initial impetus for future clinical research aimed at developing a standardized, targeted tool for assessing both the perception and production of categorical liaison in French. Such a tool—adaptable to various linguistic contexts (e.g., words, pseudowords, noun phrases, and semantically meaningful or neutral sentences)–would offer considerable clinical utility. In particular, it could support early detection of categorical liaison difficulties, which may serve as a potential early marker of expressive DLD, especially in children considered at risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Elisabeth Cesari, Bernard Laks and Frédéric Isel; Data curation, Elisabeth Cesari and Frédéric Isel; Formal analysis, Elisabeth Cesari and Frédéric Isel; Investigation, Elisabeth Cesari; Methodology, Elisabeth Cesari and Frédéric Isel; Project administration, Bernard Laks and Frédéric Isel; Resources, Elisabeth Cesari, Bernard Laks and Frédéric Isel; Software, Elisabeth Cesari and Frédéric Isel; Supervision, Bernard Laks and Frédéric Isel; Validation, Elisabeth Cesari, Bernard Laks and Frédéric Isel; Visualization, Frédéric Isel; Writing – original draft, Elisabeth Cesari and Frédéric Isel; Writing – review & editing, Frédéric Isel.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Université Paris Nanterre (Nanterre, France) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all parents of children involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating children and their families. They are also very grateful to the Maison Départementale des Personnes Handicapées (MDPH - Departmental House for the Disabled) of the Bas-Rhin (69) and Val d'Oise (95) departments in France, the management team and teachers of the two ULIS (Unités Localisées pour l'Inclusion Scolaire, Local Units for School Inclusion) schemes where the 24 children with expressive DLD were recruited, and the state schools in the departments of Hauts de Seine (92) and Val d’Oise (95) departments in France where the 22 neurotypical children who formed the control group (14 boys) were also selected.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DLD |

developmental language disorder |

| LTM |

long-term memory |

| PDH |

procedural deficit hypothesis |

| ULIS |

unités localisées pour l'inclusion scolaire |

References

- Repères et références statistiques – Enseignement, Formation, Recherche (2020). DEPP, France.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5 (R)) (5th ed.). [CrossRef]

- Aram, D. M., & Nation, J. E. (1975). Patterns of Language Behavior in Children with Developmental Language Disorders. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 18(2), 229-241. [CrossRef]

- Rapin, I., & Allen, D. A. (1983). Developmental language disorders: Nosologic considerations. In U. Kirk (Éd.), Neuropsychology of language, reading, and spelling (p. 155-184). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Bishop DVM, Snowling MJ, Thompson PA, Greenhalgh T, CATALISE consortium (2016) CATALISE: A Multinational and Multidisciplinary Delphi Consensus Study. Identifying Language Impairments in Children. PLoS ONE 11(7): e0158753. [CrossRef]

- Gérard, C.-L. (1993). L’enfant dysphasique (1ère édition). De Boeck Supérieur.

- Tallal, P. (1980). Auditory temporal perception, phonics, and reading disabilities in children. Brain and Language, 9(2), 182-198. [CrossRef]

- Maillart, C., Schelstraete, M.-A., & Hupet, M. (2004). Phonological Representations in Children With SLI. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 47(1), 187-198. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L. B. (2014). Specific Language Impairment Across Languages. Child development perspectives, 8(1), 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Conti-Ramsden, G., & Jones, M. (1997). Verb Use in Specific Language Impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40(6), 1298-1313. [CrossRef]

- Van der Lely, H. K. J. (2005). Domain-specific cognitive systems: Insight from Grammatical-SLI. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 53-59. [CrossRef]

- Kail, R. (1994). A Method for Studying the Generalized Slowing Hypothesis in Children With Specific Language Impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 37(2), 418-421. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, S., Parisse, C., & Maillart, C. (2009). Les difficultés morphosyntaxiques des enfants présentant des troubles spécifiques du langage oral : Une approche constructiviste. Rééducation Orthophonique, 238, 21-45.

- Leroy, S. (2013). Troubles de la généralisation dans les grammaires de construction chez des enfants présentant des troubles spécifiques du langage [These de doctorat, Paris 10]. https://www.theses.fr/2013PA100219.

- Gopnik, M. (1990). Feature Blindness: A Case Study. Language Acquisition, 1(2), 139-164. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. V. M. (1979). Comprehension in Developmental Language Disorders. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 21(2), 225-238. [CrossRef]

- Delattre, P. (1947). La Liaison en Français, Tendances et Classification. The French Review, 21(2), 148-157. JSTOR.

- Basset, B. (2000). La liaison à 3, 7 et 11 ans : Description et acquisition. Mémoire de maîtrise, Université de Grenoble, 3(ms).

- Dugua, C. (2005). De la liaison à la formation du lexique chez les jeunes enfants francophones. Le Langage et l’homme, 40(2), 163-182. Francis.

- Wauquier, S. (2009). Acquisition de la liaison en L1 et L2 : Stratégies phonologiques ou lexicales ? Acquisition et interaction en langue étrangère, 93-130. [CrossRef]

- Dugua, C. (2015). L’oreille ou l’oeil ? Ou comment expliquer la réalisation des liaisons dans une tâche de lecture chez des enfants âgés entre 8 et 11 ans. Séminaire « La liaison », Laboratoire MoDyCo, Université de Nanterre Paris. https://www.modyco.fr/fr/1018-modyco/1786-s%C3%A9minaire-la-liaison-2.html.

- Chevrot, J.-P., Dugua, C., & Fayol, M. (2005). Liaison et formation des mots en français : Un scénario développemental. Langages, 158(2), 38-52. Cairn.info. [CrossRef]

- Wauquier-Gravelines, S., & Braud, V. (2005). Proto-déterminant et acquisition de la liaison obligatoire en français. Langages, 158(2), 53-65. Cairn.info. [CrossRef]

- Chevrot, J.-P., Nardy, A., Barbu, S., & Fayol, M. (2007). Production et jugement des liaisons obligatoires chez des enfants tout-venant et des enfants atteints de troubles du langage : Décalages développementaux et différences interindividuelles. Rééducation orthophonique, 229, 199-220.

- Laks, B. (2005). Phonologie et construction syntaxique : La liaison, un test de cohésion et de figement syntaxique. Linx. Revue des linguistes de l’université Paris X Nanterre, 53, 155-171. [CrossRef]

- Laks, B., Calderone, B. & Celata, C. (2014). French liaison and the lexical repository. In C. Celata & S. Calamai (Ed.), Advances in Sociophonetics (pp. 31-56). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [CrossRef]

- Celata, C., & Isel, F. (2023). Relation between production and processing of the French liaison during lexical access. Langue Française, éditions Armand Colin. [CrossRef]

- Chevrot, J.-P., Dugua, C., & Fayol, M. (2009). Liaison acquisition, word segmentation and construction in French: A usage-based account. Journal of Child Language, 36(3), 557-596. Cambridge Core. [CrossRef]

- Wauquier, S. (2005). Statut des représentations phonologiques en acquisition, traitement de la parole continue et dysphasie développementale [Habilitation à diriger des recherches, EHESS]. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03252302.

- Gathercole, S. E., & Baddeley, A. D. (1995). Short-Term Memory May Yet Be Deficient in Children With Language Impairments: A Comment on van der Lely & Howard (1993). Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 38(2), 463-466. [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A. (1992). Working Memory. Science, 255(5044), 556-559. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. V. M. (1992). The Underlying Nature of Specific Language Impairment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 33(1), 3-66. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J. W. (1995). Examination of phonological working memory in specifically language-impaired children. Applied Psycholinguistics, 16(4), 355-378. Cambridge Core. [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory: Looking back and looking forward. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4(10), 829-839. [CrossRef]

- Majerus, S., Vrancken, G., & Van der Linden, M. (2003). Perception and short-term memory for verbal information in children with specific language impairment: Further evidence for impaired short-term memory capacities. Brain and Language, 87(1), 160-161. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J. W. (2003). Working memory and comprehension in children with specific language impairment: What we know so far. Journal of Communication Disorders, 36(3), 221-231. [CrossRef]

- Archibald, L. M. D., & Gathercole, S. E. (2006). Short-term and working memory in specific language impairment. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 41(6), 675-693. [CrossRef]

- Parisse, C., & Mollier, R. (2008). Le déficit de mémoire de travail chez les enfants dysphasiques est-il ou non spécifique du langage ? Congrès mondial de linguistique française, 1819-1830. [CrossRef]

- Majerus, S., Van der Linden, M., Poncelet, M., & Metz-Lutz, M. -N. (2004). Can phonological and semantic short-term memory be dissociated? Further evidence from landau-kleffner syndrome. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 21(5), 491-512. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L. B., Weismer, S. E., Miller, C. A., Francis, D. J., Tomblin, J. B., & Kail, R. V. (2007). Speed of Processing, Working Memory, and Language Impairment in Children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50(2), 408-428. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In Psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 2, pp. 89-195). Academic press.

- Davachi, L. (2006). Item, context and relational episodic encoding in humans. Motor systems / Neurobiology of behaviour, 16(6), 693-700. [CrossRef]

- Tagarelli, K. M., Shattuck, K. F., Turkeltaub, P. E., & Ullman, M. T. (2019). Language learning in the adult brain: A neuroanatomical meta-analysis of lexical and grammatical learning. NeuroImage, 193, 178-200. [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J.H. and Wellman, H.M. (1977) Metamemory. In: Kail, R.V. and Hagen, J.W., Eds., Perspectives on the Development of Memory and Cognition, Erlbaum. Hillsdale, 62-63.

- Ullman, M. T., Earle, S. F., Walenski, M., & Janacsek, K. (2020). The neurocognition of developmental disorders of language. Annual Review of Psychology, 71, 389-417. https://doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011555. Epub 2019 Jul 23. PMID: 31337273.

- Cohen, N. J., & Squire, L. R. (1980). Preserved Learning and Retention of Pattern-Analyzing Skill in Amnesia: Dissociation of Knowing How and Knowing That. Science, 210, 207-210. DOI: 10.1126/science.7414331.

- Eichenbaum, H. (2004). Hippocampus: Cognitive Processes and Neural Representations that Underlie Declarative Memory. Neuron, 44(1), 109-120. [CrossRef]

- Squire, L. R., & Knowlton, B. J. (2000). The medial temporal lobe, the hippocampus, and the memory systems of the brain. The new cognitive neurosciences, 2, 756-776. DOI: 10.1126/science.1896849.

- Eichenbaum, H., Otto, T., Cohen, N. J. (1994). Two Functional Components of the Hippocampal Memory System. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 17, 449-472. DOI:. [CrossRef]

- Squire Larry R. & Zola-Morgan Stuart. (1991). The Medial Temporal Lobe Memory System. Science, 253(5026), 1380-1386. [CrossRef]

- Squire, L. R. (2004). Memory systems of the brain: A brief history and current perspective. Multiple Memory Systems, 82(3), 171-177. [CrossRef]

- Wise, S. P., Murray, E. A., & Gerfen, C. R. (1996). The frontal cortex-basal ganglia system in primates. Critical Reviews™ in Neurobiology, 10(3-4).

- Janacsek, K., Shattuck, K. F., Tagarelli, K. M., Lum, J. A. G., Turkeltaub, P. E., & Ullman, M. T. (2020). Sequence learning in the human brain: A functional neuroanatomical meta-analysis of serial reaction time studies. NeuroImage, 207, 116387. [CrossRef]

- Ullman, M. T. (2001). A neurocognitive perspective on language: The declarative/procedural model. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2(10), 717-726. [CrossRef]

- Barbeau, E. J. (2010). Un ou des syndromes amnésiques ? La mémoire, 64-71. https://institut-servier.com/fr/publications/la-mémoire.

- Jakubowicz, C. (2003). Computational complexity and the acquisition of functional categories by French-speaking children with SLI. Linguistics, 41(2), 175-211. [CrossRef]

- Ullman, M. T., & Pierpont, E. I. (2005). Specific Language Impairment is not Specific to Language: The Procedural Deficit Hypothesis. Cortex, 41(3), 399-433. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, S., Parisse, C., & Maillart, C. (2014). Le manque de généralisation chez les enfants dysphasiques : Une étude longitudinale. ANAE : Approche Neuropsychologique des Apprentissages chez l’Enfant, 26(131), 357-365.

- Evans, T. M., & Ullman, M. T. (2016). An Extension of the Procedural Deficit Hypothesis from Developmental Language Disorders to Mathematical Disability. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. [CrossRef]

- Desmottes, L., Meulemans, T., & Maillart, C. (2015). Les difficultés d’apprentissage procédural chez les enfants dysphasiques. ANAE : Approche Neuropsychologique des Apprentissages chez l’Enfant. https://hdl.handle.net/2268/177755.

- Hill, E. L. (2001). Non-specific nature of specific language impairment: A review of the literature with regard to concomitant motor impairments. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 36(2), 149-171. [CrossRef]

- Mayes, A. K., Reilly, S., & Morgan, A. T. (2015). Neural correlates of childhood language disorder: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 57(8), 706-717. [CrossRef]

- Lechevalier, B., & Habas, C. (2021). Mémoire procédurale et mémoire déclarative. Bulletin de l’Académie Nationale de Médecine, 205(2), 149-153. [CrossRef]

- Mayor-Dubois, C. (2010). Apprentissage procédural chez l’enfant : Études développementales et cliniques [University of Geneva]. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L. B., & Kueser, J. B. (2019). Five overarching factors central to grammatical learning and treatment in children with developmental language disorder. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 54(3), 347-361. [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, R., & Moulignier, A. (2005). La mémoire et ses troubles. EMC - Neurologie, 2(4), 505-525. [CrossRef]

- Lum, J. A. G., Conti-Ramsden, G., Page, D., & Ullman, M. T. (2012). Working, declarative and procedural memory in specific language impairment. Cortex, 48(9), 1138-1154. [CrossRef]

- Ullman, M. T., & Pullman, M. Y. (2015). A compensatory role for declarative memory in neurodevelopmental disorders. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 51, 205-222. [CrossRef]

- Marton, K., Kelmenson, L., & Pinkhasova, M. (2007). Inhibition control and working memory capacity in children with SLI. Psikhologyah: Ketav ’Et Mada’i Yisre’eli Le-’Iyun Ule-Mehkar, 50(2), 110-121. [CrossRef]

- Larson, C., Kaplan, D., Kaushanskaya, M., & Weismer, S. E. (2020). Language and Inhibition: Predictive Relationships in Children With Language Impairment Relative to Typically Developing Peers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(4), 1115-1127. [CrossRef]

- Ullman, M. T., Corkin, S., Coppola, M., Hickok, G., Growdon, J. H., Koroshetz, W. J., & Pinker, S. (1997). A neural dissociation within language: Evidence that the mental dictionary is part of declarative memory, and that grammatical rules are processed by the procedural system. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 9(2), 266–276. [CrossRef]

- Chevrot, J.-P., Dugua, C., Harnois-Delpiano, M., Siccardi, A., & Spinelli, E. (2013). Liaison acquisition: Debates, critical issues, future research. Universalism and Variation in Phonology: Papers in Honour of Jacques Durand, 39, 83-94. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81–97. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, C. W. (1995). The flankers task and response competition: A useful tool for investigating a variety of cognitive problems. Visual Cognition, 2(2–3), 101–118. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M. D. et al. (2016). The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Nature – Scientific Data, 3:160018. [CrossRef]

- New, B., Pallier, C., Brysbaert, M., & Ferrand, L. (2004). Lexique 2 : A new French lexical database. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(3), 516-524. [CrossRef]

- Mann, H. B., & Whitney, D. R. (1947). On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 18, 50–60.

- JASP Team (2024). JASP (Version 0.19.3)[Computer software].

- Dugua, C., & Chevrot, J.-P. (2015). Acquisition des liaisons prénominales : Complémentarité des approches transversale et longitudinale. Lidil. Revue de linguistique et de didactique des langues, 51, 35-63. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. P., & Kipp, K. (1998). The Development of Efficient Inhibition: Evidence from Directed-Forgetting Tasks. Developmental Review, 18(1), 86-123. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A., & Lee, K. (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science, 333, 959–964.

- Heidlmayr, K., Moutier, S., Hemforth, B., Courtin, C., Tanzmeister, R., & Isel, F. (2014). Successive bilingualism and executive functions: The effect of second language use on inhibitory control in a behavioural Stroop Colour Word task. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 17, 630-645.

- Tous à l’école. (2022). La dysphasie. https://www.tousalecole.fr/content/dysphasie.

- CERENE (2021). La dysphasie, un trouble du langage oral. https://cerene-education.fr/dysphasie/.

- France Assos Santé. (2018). La dysphasie, ce “dys” qui trouble le langage oral. https://www.france-assos-sante.org/2018/02/22/la-dysphasie-ce-dys-qui-trouble-le-langage-oral/.

- Norbury, C. F., Gooch, D., Wray, C., Baird, G., Charman, T., Simonoff, E., & Pickles, A. (2016). The impact of nonverbal ability on prevalence and clinical presentation of language disorder: Evidence from a population study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(11), 1247–1257. [CrossRef]

- Tomblin, J. B., Records, N. L., Buckwalter, P., Zhang, X., Smith, E., & O’Brien, M. (1997). Prevalence of specific language impairment in kindergarten children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40(6), 1245–1260. [CrossRef]

- Heilbron, M., Armeni, K., Schoffelen, J.-M., Hagoort, P., & de Lange, F. P. (2022). A hierarchy of linguistic predictions during natural language comprehension. Neuroscience Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, 119(32), 1-12,. [CrossRef]

- Launay, L., Maeder, C., Roustit, J., & Touzin, M. (2018). EVALEO 6-15 : Batterie d’évaluation du langage oral et du langage écrit chez des enfants de 6 à 15 ans [manuel, cahiers de passation, matériel]. Ortho-édition.

- Ralli, A.M.; Chrysochoou, E.; Roussos, P.; Diakogiorgi, K.; Dimitropoulou, P.; Filippatou, D. Executive Function, Working Memory, and Verbal Fluency in Relation to Non-Verbal Intelligence in Greek-Speaking School-Age Children with Developmental Language Disorder. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 604. [CrossRef]

- Thibault, M.-P., Helloin, M.-C., & Lenfant, M. (2009). Exalang 11-15 : batterie informatisée pour l’EXAmen du LANGage oral, du langage écrit et des compétences transversales chez le collégien. Orthomotus.

- Thibault, M.-P., Lenfant, M., & Helloin, M.-C. (2012). Exalang 8-11 : batterie informatisée pour l’EXAmen du LANGage et des compétences transversales chez l’enfant de 8 à 11 ans. Orthomotus.

- Wiig, E. H., Semel, E., & Secord, W. A. (2019). CELF 5 : évaluation des fonctions langagières et de communication. (ECPA, traducteur). ECPA par Pearson.

| 1. |

Règlement général de protection des données (RGPD) in French. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).