1. Introduction

From the very first day, babies begin to visually explore their surroundings. By accompanying their caregivers everywhere, they have the opportunity to observe their everyday environment constantly and repeatedly. This environment is not static, but often changes in front of the baby’s watchful eyes. Imagine a child observes their mother standing in the kitchen and preparing lunch, while she grabs, manipulates, and replaces different objects – just one of many complex visual scenes the child is confronted with every day. By comparing this visual spatial input with previously gathered information of the same or similar scenes (e.g., other kitchens), the child extracts important visuospatial regularities [

1]. With this implicitly acquired ‘set of rules’ children learn to efficiently understand scenes, recognize the objects embedded within them, guide goal-directed behavior and finally can predict, which objects usually appear where within a scene [

1]. This enables to navigate even completely unfamiliar surroundings. For example, our previous experience with bathrooms will generate an expectation to find the soap on the sink and not next to the toilet, in every new bathroom we will enter in life. Thus, learning about objects and their locations, i.e., the acquisition of scene knowledge is a crucial developmental challenge.

1.1. Scene Grammar Structure

According to Võ [

1], visual scenes are

governed by rules underlying the placement of objects that are part of the scenes. Given the structural similarities between scenes and language, the term “scene grammar” has been coined. In language, words serve as the basic units, each carrying specific semantic meaning. Words combine to form larger units such as phrases (groups of words) and sentences (ordered combinations of phrases following syntactic regularities). Sentences are composed of obligatory constituents – such as the predicate and its arguments (e.g., ‘Peter

subject is laughing

predicate.’) – as well as optional constituents (adjuncts), that “provide all sorts of additional information about the event/state” [2, p. 259] (e.g., ‘Peter

subject is laughing

predicate in the kitchen

adverbial phrase). In a similar way, a visuospatial scene (e.g., a kitchen) is built upon several meaningful subgroups. Võ [

1] uses the linguistic term ‘phrases’ to refer to these subgroups of objects, drawing a parallel to phrases in language. Each phrase contains an obligatory, global object – referred to as “anchor”– which is large, static, and prototypical for the scene context (e.g., the oven in a kitchen). Anchors are accompanied by one or more smaller optional elements, called local objects (e.g., a pot on the oven). In terms of space and position, anchor objects and local objects are closely related in that local objects are positioned relative to their anchors [

1]. Thus, language and scenes share their hierarchical structure, the presence of both obligatory and optional elements, and rules for combining these elements.

In experimental settings, the structure of sentences and scenes can be manipulated in terms of form and/or content. Semantic violations in linguistic stimuli occur when the meaning of a word is incongruent with the context of the sentence (e.g., ‘Peter swims in the kitchen.’), while syntactic errors arise when the word order in the sentence is violated (e.g., ‘Peter in the kitchen laughing.’). Such violations usually lead to higher cognitive costs in language processing [

3]. In a metaphorical way, visuospatial scenes can also be either semantically or syntactically inconsistent. Semantic violations occur when an object does not fit the scene, such as a bike helmet in the oven instead of a cake. Syntactic violations, on the other hand, involve typical objects positioned in atypical locations (e.g., a cake located in the dish washer and not in the oven). Identifying such inconsistencies within a scene is associated with longer gaze durations, reflecting extended processing demands, as demonstrated in several eye-tracking studies [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These findings highlight parallels between the processing of language and scenes.

Given the multimodal nature of the sensory input in our daily lives, processing of scenes and language takes place in parallel. While children observe certain visuospatial scenes, they are simultaneously exposed to linguistic input [

8]. They hear words for certain objects, that are present in a scene. Thus, linguistic input is important to acquire mental representations for different components of visuospatial scenes [

7]. Besides this obvious link, there might be a deeper connection of the development and processing of scene grammar and language, grounded in common underlying cognitive processes as suggested by a positive relationship between linguistic skills and the efficiency of scene grammar processing [

7]. Thus, children who experience difficulties in organizing and interpreting linguistic structures may also face challenges in constructing coherent scene representations. However, research into the development of scene grammar processing is still in its early stages. Building upon this, our study aimed at uncovering if and how language competence drives the visuospatial processing of indoor scenes. Assuming a link between the visual and language domain, a comparison of scene grammar processing in children showing various levels of language competence might be the ideal test case. In this study, we therefore explored scene grammar knowledge in a group of children with typical language skills and a group of children with developmental language disorder (DLD), who are characterized by difficulties in linguistic domains such as lexicon, semantics, or grammar.

1.2. Developmental Language Disorder

Childhood language disorders are deviations of children’s typical language acquisition that, without being treated, may lead to serious negative consequences for social interactions and participation, wellbeing, as well as educational and career success. With a prevalence of approx. 10%, they are one of the most common developmental disorders in childhood [

9,

10]. For the majority of children, their language disorder is of unknown origin, i.e., not associated with a known differentiating condition (e.g., a genetic syndrome), with deficits appearing mainly in the language domain. This sort of language impairment has traditionally been referred to as specific language impairment (SLI). However, the invoked specificity was questioned by empirical evidence as well as clinical experience demonstrating that affected children often show additional delays, impairments or underachievement in other developmental areas [

10,

11,

12]. This debate finally led to several multinational and multidisciplinary consensus studies, initiated in English-speaking countries by the CATALISE consortium [

10,

11], which aimed at a comprehensive revision of SES terminology and diagnostic criteria, based on consecutive expert surveys in relevant disciplines. In German-speaking countries, the D-A-CH Consortium-SES pursued this purpose [

12]. As a result of these efforts, the interdisciplinary use of the term DLD instead of SLI has been established for language disorders with no known differentiating condition.

A high degree of consensus has also been reached that children with DLD show heterogeneous profiles of individual strengths and weaknesses with persistent receptive and/or expressive deficits in at least one linguistic domain (i.e., phonology, lexicon and semantics, morphology and syntax, pragmatics and social communication [

10,

11,

12]). Phonological problems affect a child’s ability to select and combine speech sounds to form correct sound sequences and word forms. Phonological errors such as substitution or omission of speech sounds can reduce a child’s intelligibility. Lexical-semantic disorders manifest themselves in a restricted vocabulary, poor understanding of word meaning, or problems to retrieve words from the lexicon (word finding difficulties). Grammatical impairment is characterized by difficulty in understanding and using the morphological and syntactic rules of a given language. Symptoms of grammatical impairment are varied and depend on the structure of the target language; they include errors in morphological marking, omission of obligatory constituents or function words (e.g., articles, prepositions), and word order errors. Finally, social pragmatic difficulties may impede the appropriate use of verbal and non-verbal communicative means in a given situation, the processing of figurative language, or narrative and conversational skills. In the context of the present study, grammatical and lexical-semantic symptoms of DLD are particularly relevant because they are most likely to be related to the processing of scene grammar.

A key element of the new definition is the notion of co-occurring conditions, i.e., “impairments in cognitive, sensorimotor or behavioral domains that can co-occur with DLD and may affect pattern of impairment and response to intervention, but whose causal relation to language problems is unclear. These include attentional problems (ADHD), motor problems (developmental coordination disorder or DCD), reading and spelling problems (developmental dyslexia), speech problems, limitations of adaptive behavior and/or behavioral, and emotional disorders.” [

11] (p. 1072). Consequently, a low level of cognitive ability does no longer preclude a diagnosis of DLD [

10]. The existence of such co-occurring conditions supports a domain-general nature of DLD. However, it is an open question as to what kind of neurodevelopmental problems may accompany the language disorder. In particular, it is unclear, whether visual cognition is also a vulnerable domain in DLD. Initial empirical evidence points in this direction, but is inconsistent depending on the experimental tasks and the memory systems activated [

13].

1.3. Visuospatial processing in DLD

Visuospatial ability refers to a person’s capacity to identify, integrate and analyze visual information of patterns and objects and to understand their spatial relationships. It covers attentional processes that mediate the selection of relevant and the suppressing of irrelevant visual information as well as the activation of memory systems, involved in the perception, manipulation, and imagination of objects in space – in static as well as in dynamic displays and across several dimensions [

14]. Short term memory (STM) allows keeping information for a short amount of time and is usually measured via span tasks, in which participants listen to an order of words or digits, trying to recall as many as possible. Conceptually similar, but with minimal verbal mediation, corsi block tasks access visual STM by having participants recall sequences of squares on a 9x9 block layout that were highlighted in color. In contrast to STM, working memory (WM) is involved in more complex cognitive processes that require not only recall, but also the flexible manipulation of information such as learning and language processing. WM is measured via dual tasks or span tasks and corsi block tasks with backward recall. According to Baddeley’s model of working memory [

15], it consists of a central executive that controls two slave systems as well as an episodic buffer, which integrates information of both systems: The phonological loop for maintaining and processing verbal information, often impaired in children with DLD, and the visuospatial sketchpad for keeping information about spatial relationships and object properties for further processing. Some studies reported poorer performance of children with DLD in verbal span tasks, but equal performance in nonverbal visuospatial STM and WM tasks [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], and interpreted this pattern in favor of a domain-specific view on DLD. In contrast, there is growing evidence that children with DLD have deficits in both verbal and visual attention [

13,

21,

22,

23], supporting the domain-general processing limitation account [

24]. Arslan and colleagues [

13] investigated nonverbal and verbal STM and WM with span and corsi block tasks in children and adolescents with DLD (aged 7-11 years and 12-18 years) and found visual and verbal components to be modulated differently by the factor of age. While both groups with DLD showed poorer performance compared to TD controls in the verbal domain, visual SHT and WM was only impaired in the younger group with DLD. A meta-analysis [

25] on effect sizes of 21 studies comparing the performance of children with DLD and TD peers in visuospatial WM tasks (involving central executive and storage) showed that higher deficits in visuospatial processing were associated with more pervasive language impairment. In addition, Gray and colleagues [

26] investigated the performance of 300 children with DLD, dyslexia or both in 13 tasks, which assessed central executive, phonological, and visuospatial/attention components of WM. For 21% of the children with DLD they report poorer performance in all WM components compared to the TD controls.

The third memory system, the visual long-term memory, stores conceptual knowledge about object properties and their spatial relations. It is commonly divided in declarative (episodic and general semantic) knowledge and procedural memory. Nonverbal (including visual) declarative knowledge, tested by memory tasks using pictures or abstract patterns, appears to be relatively intact in DLD [

27]. In terms of procedural memory, children with DLD often respond slower not only in verbal tasks (e.g., naming), but also in nonverbal tasks, such as categorization [

28] or interference control (e.g., stroop tasks), as recently shown in a meta-analysis comprising 46 studies on children with DLD [

29].

As mentioned earlier, visual and verbal processing often run in parallel and sometimes conclusions about procedural efficiency in one modality can be drawn from observing behavioral responses in the other. Lara-Diaz and colleagues [

30] measured phonological processing via visual attention in an auditory visual world identification task combined with eye-tracking in children diagnosed with DLD. The children heard a word and were asked to look at the target picture, which was displayed next to pictures with phonologically related distractors (rhyme and the same onset) and one unrelated distractor. Compared to their TD peers, the children with DLD showed a reduced sensitivity towards the identification of rhyme words, expressed in a missing interference effect (longer looking times to phonological distractors compared to unrelated objects while searching for the target). Visual scenes, however, are more complex than single objects (comparable to the word-sentence distinction in language). Therefore, methods using the visual-world paradigm and eye-tracking seem to be a more worthwhile and ecologically valid way to investigate children’s knowledge of the structure of everyday visual scenes. Such investigations may also shed light on the role of language competence in efficient scene grammar processing. To date, only a few studies used this combination of methods in children with typical language development and with DLD to investigate the acquisition of scene grammar regularities.

1.4. Accessing Scene Grammar in Children with and without DLD using Eye-Tracking

Previous studies with TD children at preschool age investigated how scene grammar knowledge guides children’s visual attention during free observation of pictures displaying everyday indoor scenes, e.g., bathrooms or bedrooms [

7,

31,

32]. These scenes were either consistent (scene-related objects appear at expected locations), semantically inconsistent (objects do not fit the scene context), syntactically inconsistent (objects appear at unexpected locations) or both, semantically and syntactically inconsistent. Results provided first evidence that already by the age of 2, children are able to perceive semantic and syntactic violations as indicated by inconsistency effects (longer observation of inconsistent, compared to consistent objects) [

7,

31]. Thereby, inconsistency effects for combined semantic and syntactic violations and for pure semantic violations appear earlier in the course of development than those for pure syntactic violations. With increasing age, inconsistency effects become stronger with gaze durations on consistent objects decreasing in relation to inconsistent objects [

7]. In contrast to adults, inconsistency effects in children are driven by saliency, with stronger effects for violations with high saliency [

31]. The existence of inconsistency effects in early childhood has been further supported by an ERP-study, which found that children at the age of two already showed adult-like N400 effects when observing semantic scene inconsistencies, supporting the assumption that they are able to detect them implicitly [

32]. In addition to the free viewing paradigm combined with eye-tracking, Öhlschläger and Võ [

7] directly accessed scene grammar knowledge of preschool children (2-4 years), using a behavioral task, in which children were asked to furnish a wooden dollhouse. The house included four rooms, a bedroom, kitchen, living room, and bathroom that were predefined by the anchor objects bed, oven, sofa, and shower. The authors found an age-related increase of correctly placed objects and closer inter-object-relations, indicating knowledge about spatial distances of anchors and local objects in indoor scenes. They also found correlations between implicit and explicit measures of scene knowledge: A reduction in first-pass dwell times on consistent objects (strength of inconsistency effect) was predicted by the object placement performance in the dollhouse task.

Furthermore, the aforementioned studies report positive correlations between congruency effects and expressive vocabulary, indicating that a high level of language skills is associated with a higher sensitivity towards scene violations (i.e., stronger inconsistency effects) [

7,

31] and a higher object placement performance in the dollhouse task [

7].

As mentioned above, children with DLD often have problems with the acquisition of grammatical structures, as evidenced by a reduced ability to detect syntactic errors [

33]. The acquisition and correct use of grammatical rules requires procedural memory capacity. The domain-general processing limitation account [

24] and the Procedural Deficit Hypothesis (PDH) [

34,

35,

36] view DLD as a complex neuropsychological condition and suggest that the language processing deficits seen in DLD may be due to impaired statistical learning, i.e., an underperformance of domain-general mechanisms involving the central executive, STM and WM. According to the PDH, this underperformance results from abnormalities in brain structures that mainly affect the basal ganglia - a structure responsible for higher cognitive functions such as perception, attention and executive functions, and thus for the constitution of procedural memory. Deficiencies in procedural memory may therefore affect language and visuo-cognitive processing in the same way. For example, possible delays in the acquisition of visual scene knowledge may affect the acquisition of words for spatial relationships, such as prepositions. In view of this, children with DLD may also have difficulty recognizing semantic and syntactic inconsistencies in scene grammar. Investigating visuo-cognitive performance, including the processing of everyday visual scenes, in children with DLD may provide further evidence for the domain-general explanation of DLD.

To our knowledge, scene grammar processing in children with DLD has only been tested in one study. Applying the same experimental procedure as with TD children [

31], Helo et al. [

37] investigated whether 5;4-to 6;6-year-old children with DLD differ from TD peers in their gaze behavior when observing pictures, showing consistent or semantically and syntactically inconsistent indoor scenes. The authors found group differences regarding the emergence of consistency effects. Children with DLD showed inconsistency effects only for the very obvious semantic and syntactic violations, but not for the syntactic only and semantic only condition. Thus, children with DLD were less attracted by scene inconsistencies compared to TD peers, which speaks for an existing link between language and scene grammar processing.

However, no direct group comparisons of the mentioned eye tracking measures were reported in this study, and the results were based on only one age group of preschool-children and one task. It remains unclear, whether a reduced sensitivity to syntactic scene violations might depend on age. Older children at primary school age may still show different gaze behavior towards scene inconsistencies, or they may have caught up with their TD peers. Furthermore, the use of more than one experimental task and the inclusion of multiple measures of lexical and grammatical ability will shed light on the extent to which scene grammar processing is less efficient in children with DLD, and how strongly it is related to language ability.

1.5. Objective

Against this background, the aim of the present study was to assess scene grammar processing of TD children and children with DLD at primary school age in two different ways: (1) implicitly, by analyzing children’s looking behavior at congruent and inconsistent indoor scenes in a free-viewing eye-tracking paradigm and (2), explicitly, by using a dollhouse task. We chose two non-verbal tasks that did not require any language processing other than understanding the instructions as this minimized the likelihood that poorer performance in scene grammar processing by the DLD group was due solely to their language deficits. Furthermore, we comprehensively tested the participants’ linguistic, nonverbal cognitive, and visual skills to uncover potential relationships to scene grammar processing. Lower performance in scene grammar processing, i.e., a reduced sensitivity towards semantic and syntactic scene violations as well as a reduced ability to arrange objects in appropriate spatial relations and locations, would support the notion that visual and verbal processing may be grounded in the same underlying cognitive processes and, at the same time, contribute to a more comprehensive clinical picture of this multifactorial disorder.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of two groups of children aged from 5 years and 7 months up to 10 years and 10 months of life. The first group included 20 participants (4 female) with typical language development (TD) and the second group 20 children (4 female) with a diagnosis of DLD showing receptive and/or productive deficits in lexical/semantic and/or grammatical abilities. Thus, children with speech sound disorders only were not included in the sample. Children of both groups underwent subtests of two standardized developmental language tests to confirm the diagnosis of DLD and typical language development, respectively (see

Section 2.2and

Section 3.1, including

Table 1). Participants of both groups were matched in pairs according to gender and months of life (

MDLD: 95.8 months,

SDDLD: 22 months;

MTD: 96.2 months,

SDTD: 21 months). To examine potential age effects, we split both groups at the age of 7.88 years. This resulted in two age groups: one consisting of participants aged 5.58 to 7.92 years (

NTD = 9;

NDLD = 11) and the other aged 8.92 to 10.83 years (

NTD = 11;

NDLD = 9).

TD children were recruited via schools, local day care services and public announcements. Parents of children with DLD were informed about the study by their children’s speech and language pathologists. All children had been receiving speech and language therapy for several months (at least once a week) through local services. With the exception of one child, all children were also attending an intensive in-patient therapy at speech and language intervention centers at the time of testing. The parents were financially compensated and the children received a small gift after each session.

2.2. Procedure

Prior to the experimental procedure, children and parents were fully informed about the purpose and content of the study. Parents agreed on their children’s participation and on the recording of audio and video clips of their children’s responses by signing informed consents. Children verbally agreed to participate.

The study comprised three sessions, which took approximately 40 minutes each. They were conducted in a quiet room either in laboratories at Universities of Frankfurt am Main, Giessen, and Marburg (Hesse, Germany), at intervention centers for speech and language therapy or at the participants’ home. The first session included the implicit and explicit measure of scene grammar processing, i.e., the free-viewing task (Eye-Tracking, see

Section 2.3) and the dollhouse task (see

Section 2.4).

In the second session, we accessed children’s nonverbal cognitive skills and visuospatial perception with three different tests to rule out that potential problems in scene grammar processing in children with DLD might be due to attention deficits or reduced intellectual abilities (see

Section 3.2 and

Table 1 for results). (1) In the

attention test – star search (subtest 3 of the ‘Sprachstandserhebungstest für Kinder im Alter zwischen 5 und 10 Jahren – SET 5-10’ [

38]), children were asked to identify as many stars as possible within lines of mixed symbols in one minute. (2) We conducted the nonverbal intelligence test ‘Coloured Progressive Matrices – CPM’ [

39]. (3) Children completed three subtests of the German adaption of the ‘Developmental Test of Visual Perception’ – DTVP-3 [

40], i.e., ‘Frostigs Entwicklungstest der visuellen Wahrnehmung – FEW-3’ [

41]. The subtests were

figure-ground (recognition of hidden forms against noisy backgrounds)

, visual closure (finishing forms mentally) and

form constancy (recognizing identical shapes regardless of their size, color or orientation).

Language testing took place in the third session (see

Section 3.1 and

Table 1 for results). We applied five subtests of the ‘SET 5-10’ [

38]:

expressive vocabulary (words and categories),

sentence comprehension, text comprehension,

error identification or sentence correction (based on the participants’ age). As the inclusion criterion for the experimental group, children with DLD should either perform 1.5 SD below age-specific norms (percentile rank < 7) in at least one subtest of the SET 5-10 or between 1 to 1.5 SD below the norm (percentile rank 7-16) in at least three subtests. TD children were allowed to perform 1 to 1.5 SD below the norm in only one of the subtests (percentile rank 7-16). Besides the group assignment of participants, language skills were also obtained to investigate their impact on experimental performance in implicit and explicit scene grammar processing. We therefore conducted the subtest

picture description of the ‘Patholinguistische Diagnostik bei Sprachentwicklungsstörungen – PDSS’ [

42]. This instrument utilizes elicited production in order to generate four test scores: mean length of utterances, completeness of utterances, and two grammar scores comprising relevant target structures. The construction of the grammar scores was inspired by the Index of Productive Syntax (IPSyn), and modified for German [

43].

2.3. Implicit Measure of Scene Knowledge: Free Viewing Task

2.3.1. Stimuli

45 images were selected from the SCEGRAM database [

4] encompassing both semantically inconsistent and syntactically inconsistent scenes, as well as consistent scenes (see

Figure 1 for an example). We created areas of interests (AOIs) retaining their size and location consistency across both, the semantically inconsistent and consistent conditions. Similarly, in the syntactically inconsistent and consistent conditions, the AOIs maintained identical sizes. To ensure accurate tracking, especially considering the less stringent eye-tracking thresholds for children, we included an online buffer of 75 pixels on each side of the AOI. Images were counterbalanced across participants, ensuring that each participant encounters an object only in one condition. To rule out the potential influence of saliency on differences between conditions, we computed the mean saliency rank using DeepGaze IIE [

44]. Analysis revealed no difference between our conditions (consistent: semantically inconsistent — ratio = 0.822, SE= 0.139, z ratio = -1.16,

p= 0.48; consistent: syntactically inconsistent — ratio = 0.795, SE= 0.134, z ratio = -1.364,

p= 0.36; semantically inconsistent: syntactically inconsistent — ratio = 0.966, SE= 0.162, z ratio = -.204,

p= 0.98).

2.3.2. Apparatus

We tracked children’s eye movements from the left eye employing the EyeLink 1000 Portable Duo system (SR Research, Kanata, Ontario, Canada) with a sampling rate of 500 Hz, operated in remote mode. Stimuli were presented either on a 17-inch laptop screen or 24-inch monitor with a resolution of 1920 x 1080 pixels and a refresh rate of 144 Hz. Children were seated approximately 70 cm away from the screen. Before starting the experiment, a 5-point calibration was performed using an audio-visual target and a drift check was performed every 10 trials. After 2 practice trials, children proceeded to the main experiment of 45 trials. Each trial started with an audio-visual fixation spiral appearing to the left or right side of the screen. The fixation spiral was gaze-contingent, requiring children to maintain fixation for at least 500 milliseconds to trigger the stimulus presentation. The scene images appeared on the screen for 7 seconds, with a reward video randomly shown approximately every 2 images, lasting about 10 seconds each time. Children were instructed to freely observe the scenes (see [

7] (p. 7) for an image of the trial sequence of this gaze-contingent eye-tracking paradigm).

2.3.3. Analysis of Eye-Movements

To investigate children’s interest in scene violations, we focused on total dwell time (DT) as eye movement measure. Dwell time is the sum of all fixations and saccades from the first to the last visit to a specific area of interest, reflecting the interest shown for that area. We excluded trials with a dwell time of less than 100 ms (8.4%) from our analysis, as such brief durations are typically considered insufficient for processing information [

45].

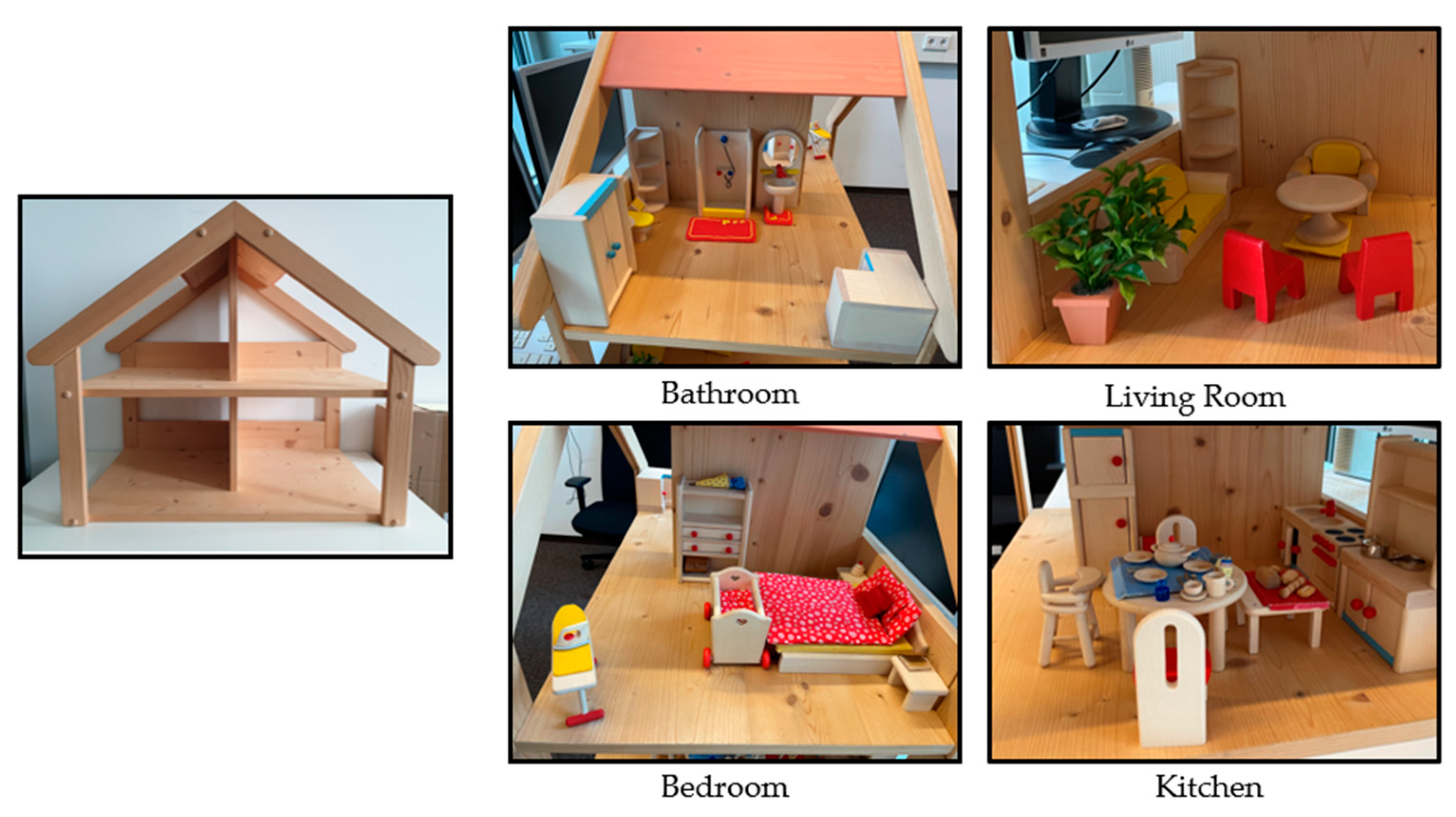

2.4. Explicit Measure of Scene Knowledge: Dollhouse Task

Children were instructed to furnish a wooden dollhouse (Nic Spiel + Art GmbH, Laupheim, Germany, see

Figure 2) with 61 local objects. The dollhouse featured two floors and four rooms, each sized at 31 cm by 40 cm. The standardized initial setup of the dollhouse comprised the following rooms and their characteristic anchor objects: a bedroom with a bed, a kitchen with a stove, a bathroom with a shower, and a living room with a sofa. Each participant was asked to arrange all objects at the place in the house that is most fitting. There was no time limit. Children’s hands were video-recorded while furnishing.

2.4.1. Stimuli

Out of 61 dollhouse objects, we chose objects that were characterized as informative based on both common-sense as applied in a previous study [

46] as well as on statistics of objects in a real-world image data-set [

47], following the approach used by Öhlschläger and Võ with younger children and adults [

7]. Essentially, our inclusion of objects in the final analysis depended on their likelihood of strongly associating a scene with a specific category (e.g., a scene that has toilet paper in it strongly associates that scene with a bathroom scene). The expectation was that the information provided by the objects and the scene would complement and reinforce each other. Based on these considerations, in the final analysis the following 41 objects were included: armchair, baby bed, baby chair, backpack, bath rug, bed, blanket, bread, book, butter, chair, cheese, closet, coffee table, cup, desk, dinner set, dining table, fridge, iron, iron board, jam jar, jug, ketchup, nightstand, pillow, plant, pot, shelf, shower, sink, soap, sofa, stove, trashcan, toilet, toilet paper holder, toilet rug, towel, toothbrush, vacuum.

2.4.2. Analysis

Semantic knowledge in the dollhouse task was measured as the accuracy of placing objects in their respective rooms, i.e., the number of correctly placed objects in %. Some objects were informative for more than one room (e.g., pillow) and counted as correct in any of the respective rooms (e.g., bedroom and living room). Also, some of the objects were not easily recognized by children (e.g., nightstand) and represented as other similar objects by children (e.g., stool). We counted these placements as correct, based on the room in which the object they resembled should be located (e.g., living room).

The measure of syntactic knowledge in the dollhouse task was determined by the distance between predefined anchor and local objects given in meter (m) in a 3d environment. To obtain this information, we conducted a 3D scan of each child’s completed dollhouse. These scans were imported into Unity (Unity Technologies, 2023, Version 2021.3.18f1) where we had pre-scanned dollhouse objects. We placed the virtual objects into the scanned dollhouse environment just as the participant placed them in, ensuring precision in our measurements. After positioning all the objects, a script we wrote in Unity generated a matrix showing the distance between the center of every object. Our focus was solely on objects placed in the correct room category and specifically on the predefined anchor and local objects.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To perform statistical analysis, we utilized linear mixed models (LMMs) [

48] and generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs). LMMs allowed us to incorporate the saliency ranks of scenes and participants as random factors. GLMMs, which extend LMMs, were employed to handle data with non-normal distributions or binomial responses, enabling us to use raw data without aggregation [

48]. Specifically, GLMMs were used for models with binomial responses, such as object placement performance in the dollhouse task, and when scaling methods could not normalize the response variable distribution. The models were implemented in R environment (version 2023.09.1; R Core Team, 2021) using the `lmer` function from the lme4 package [

49]. The corresponding

p-values were calculated using the lmerTest package [

50], applying Satterthwaite approximations for the degrees of freedom.

In the models for the free viewing task, dwell time was the fixed factor, while language groups (DLD - TD), violation type (consistent, semantically inconsistent and syntactically inconsistent) and age groups (“5.58 years - 7.92 years” - “8.92 years - 10.83 years”) served as predictors. Subjects were always included as a random factor to account for subject variability. We also set a random intercept and random slope for saliency rank in each scene. This approach allows both the baseline response and the saliency rank effect to vary by scene, providing a more flexible model that can capture scene-specific variations in both baseline levels and predictor effects. Tests from which we derived visual intelligence and attention scores, such as CPM, FEW-3, and star search (SET5-10), were included as covariates based on their contribution to the model and their impact on the response variable.

In the dollhouse task models, where the fixed factor is object placement performance or mean distance between related objects, subjects were always included as random factors. Predictor were language groups and age groups. Additionally, CPM, FEW, and SET-3 scores were again incorporated as covariates based on their contribution to the model and their effect on the response variable. Only when examining the relationship between dollhouse task measures and language measures, aggregated data were used and age was added as a covariate factor.

3. Results

3.1. Tests of Language Development

T-Tests for unpaired samples confirmed a significantly lower performance of children in the DLD group compared to TD children in all subtests of the SET 5-10 as well as in all four scores of the PDSS subtest picture description (see

Table 1).

3.2. Nonverbal Cognitive Tests

Descriptive statistics and group comparisions of all three nonverbal cognitive tests are displayed in

Table 1. In the attention test star search (subtest 3 of SET 5-10), both groups performed equally well and within the age-appropriate norms (percentile rank ≥ 16). In the CPM performance of both groups was within the age norm (percentile rank ≥ 16). However, children with DLD reached significantly lower scores than TD children. In the test of visual perception (FEW-3), both groups showed age appropriate performance (percentile rank ≥ 16), but children with DLD again scored lower than TD children.

3.3. Implicit Measure of Scene Knowledge: Free Viewing Task

Descriptive statistics of dwell time on consistent as well as semantically and syntactically inconsistent objects by group and age are displayed in

Table 2.

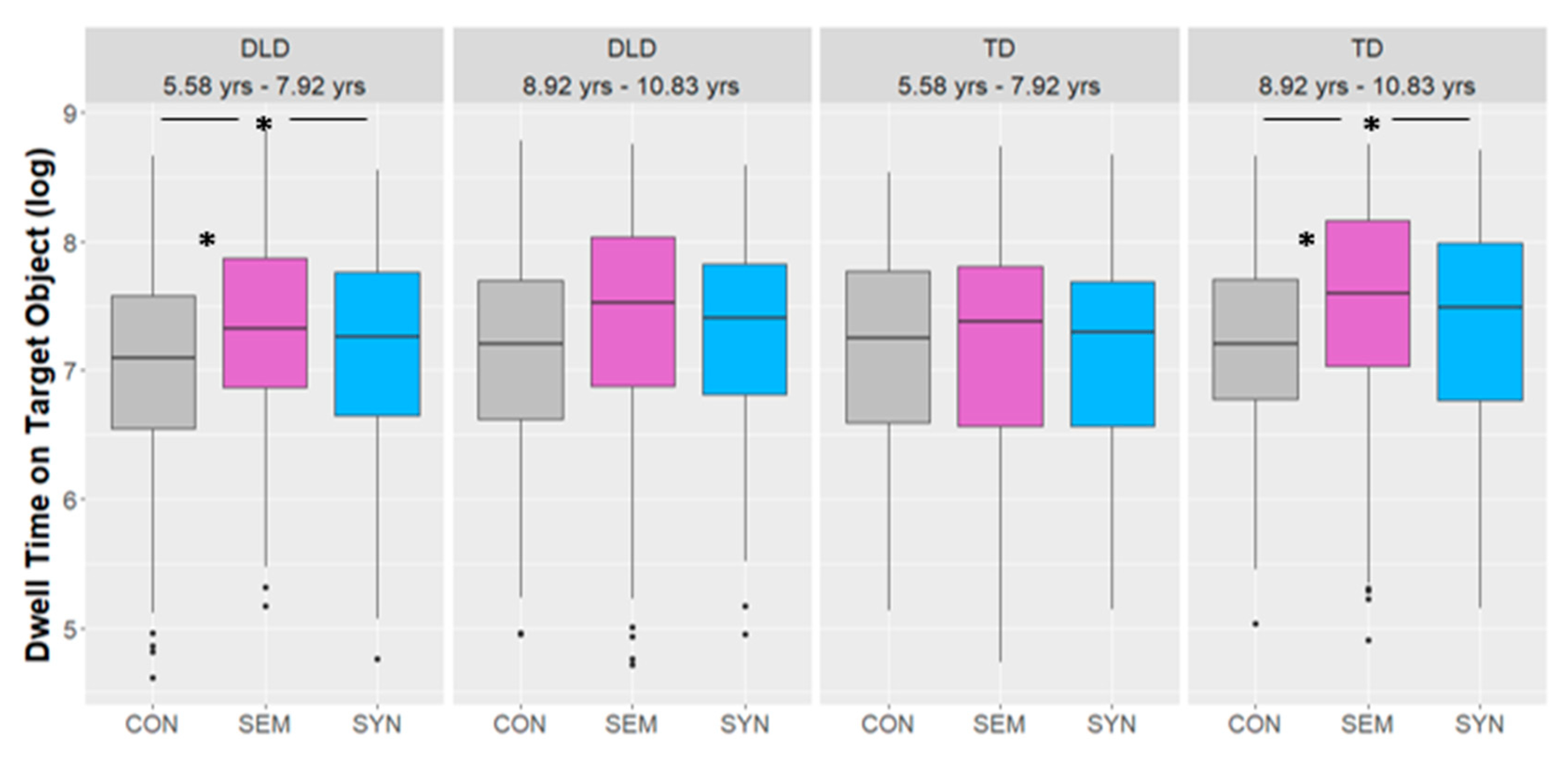

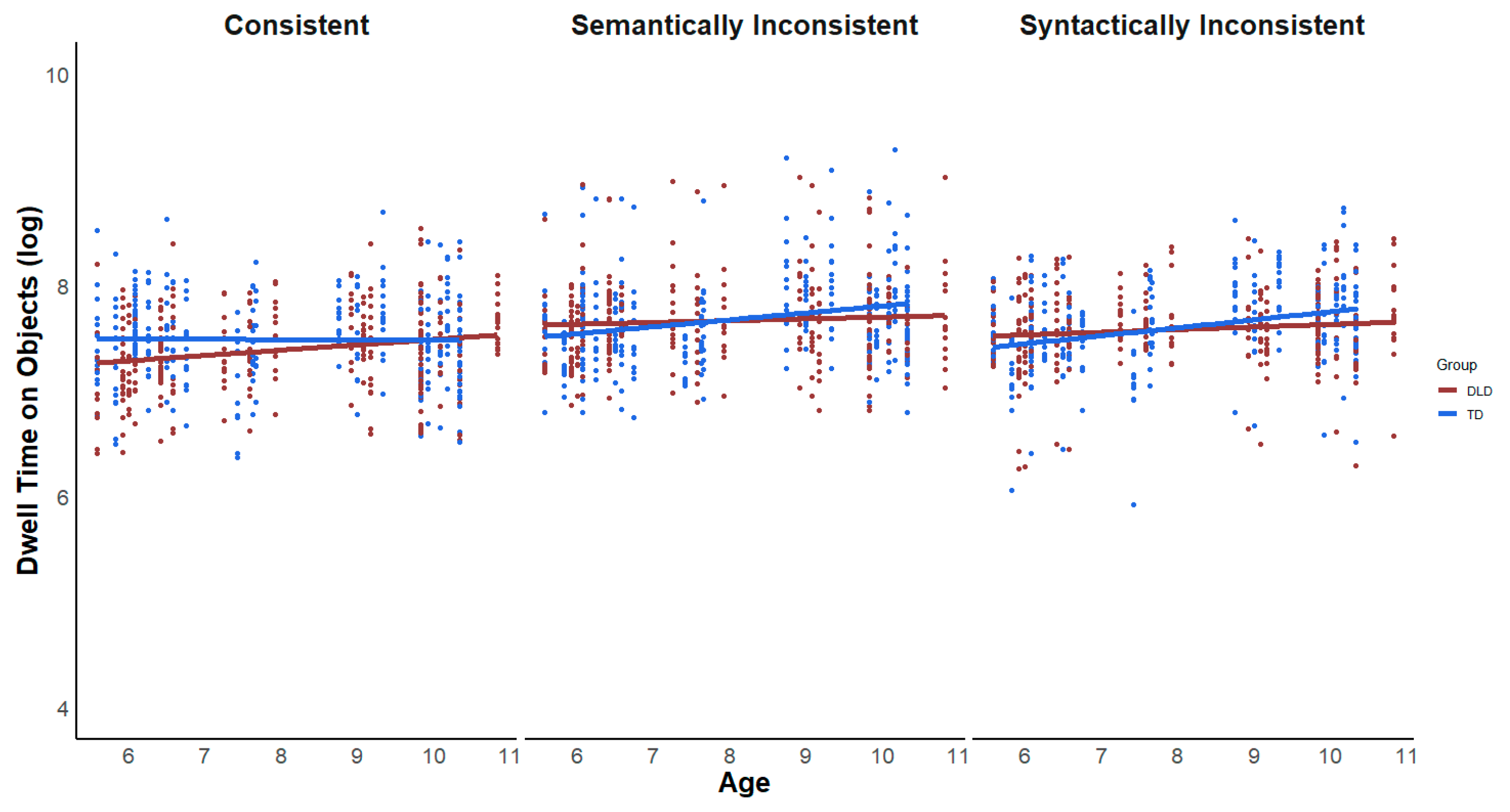

Results from the LMER models showed a main effect of violation type on children’s dwell time (β = -0.1104, SE = 0.02733,

t = -4.039,

p < 0.001) with significantly shorter looking times at consistent objects compared to the semantic and syntactic condition (consistency effect). There was no main effect of group on the dwell time of children (β = 0.0129, SE = 0.0704,

t = 0.183,

p = 0.856) and also no main effect of age (β = 0.110, SE = 0.077,

t = 1.426,

p = 0.163). In more detail, both groups showed a semantic inconsistency effect, i.e., they spent less time dwelling on consistent objects compared to semantically inconsistent objects (DLD: β = -0.2764, SE = 0.0663,

t = -4.166,

p < 0.0001; TD: β = -0.1683, SE = 0.0671,

t = -2.508,

p < 0.0328). Children with DLD dwelled longer on the syntactically inconsistent objects compared to consistent objects (β = -0.174, SE = 0.066,

t = -2.629,

p = 0.023). Furthermore, this consistency effect was modulated by the factors of age and group (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4): While TD children of the younger age group showed no differences in their dwell time with respect to the three different scene conditions, older children with TD demonstrated a robust consistency effect, i.e., shorter looking times to consistent objects compared to both semantically inconsistent objects (β = -0.284, SE = 0.097,

t = -2.930,

p = 0.0096) and syntactically inconsistent objects (β = -0.268, SE = 0.094,

t = -2.844,

p = 0.0125). Children in the DLD group showed the opposite pattern with younger children displaying a semantic and syntactic inconsistency effect ((β = -0.3056, SE = 0.096,

t = -3.179,

p = 0.0043; β = -0.2182, SE = 0.091,

t = -2.386,

p = 0.0452, respectively), while older children with DLD dwelled equally long on consistent and inconsistent objects.

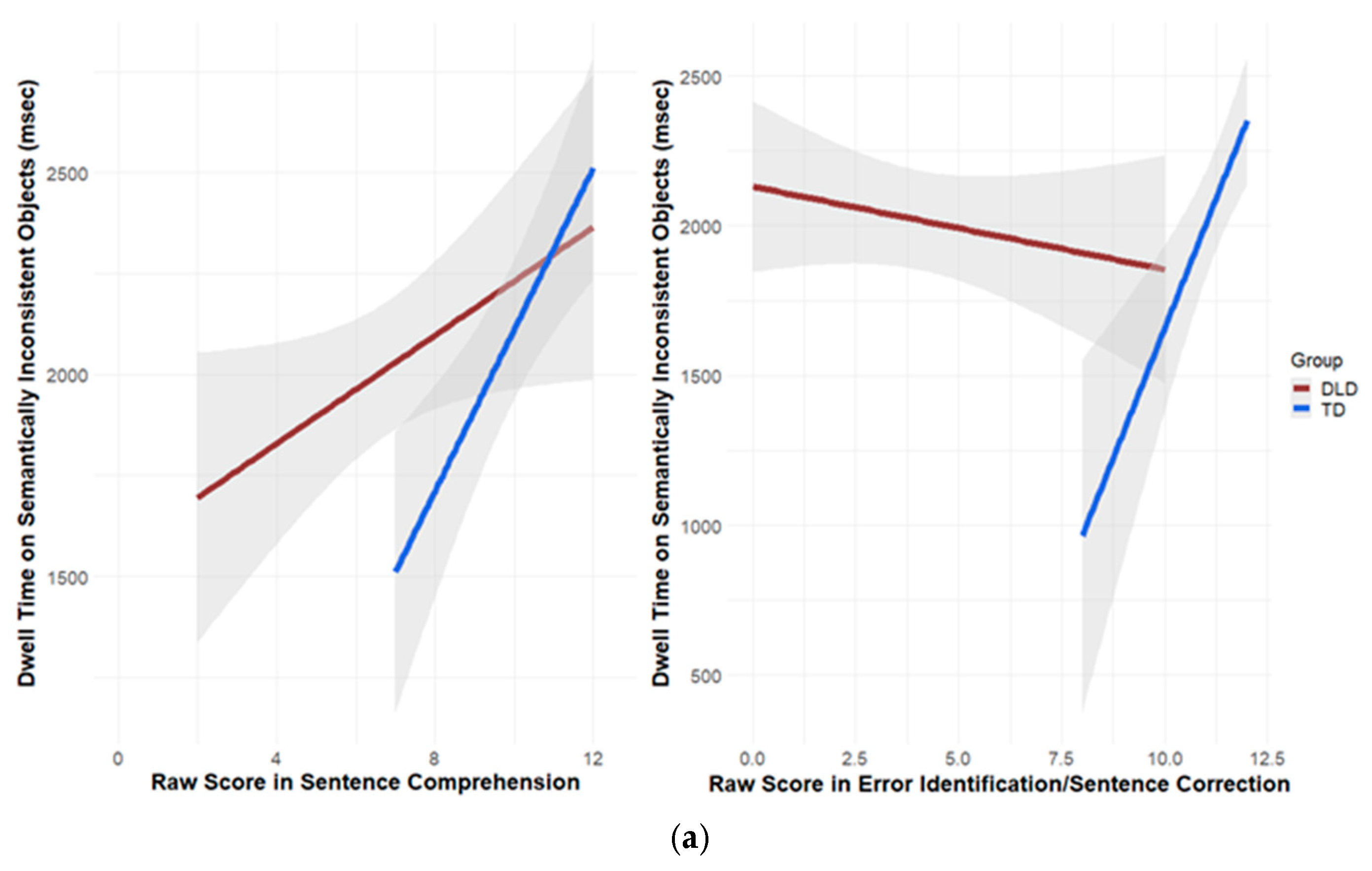

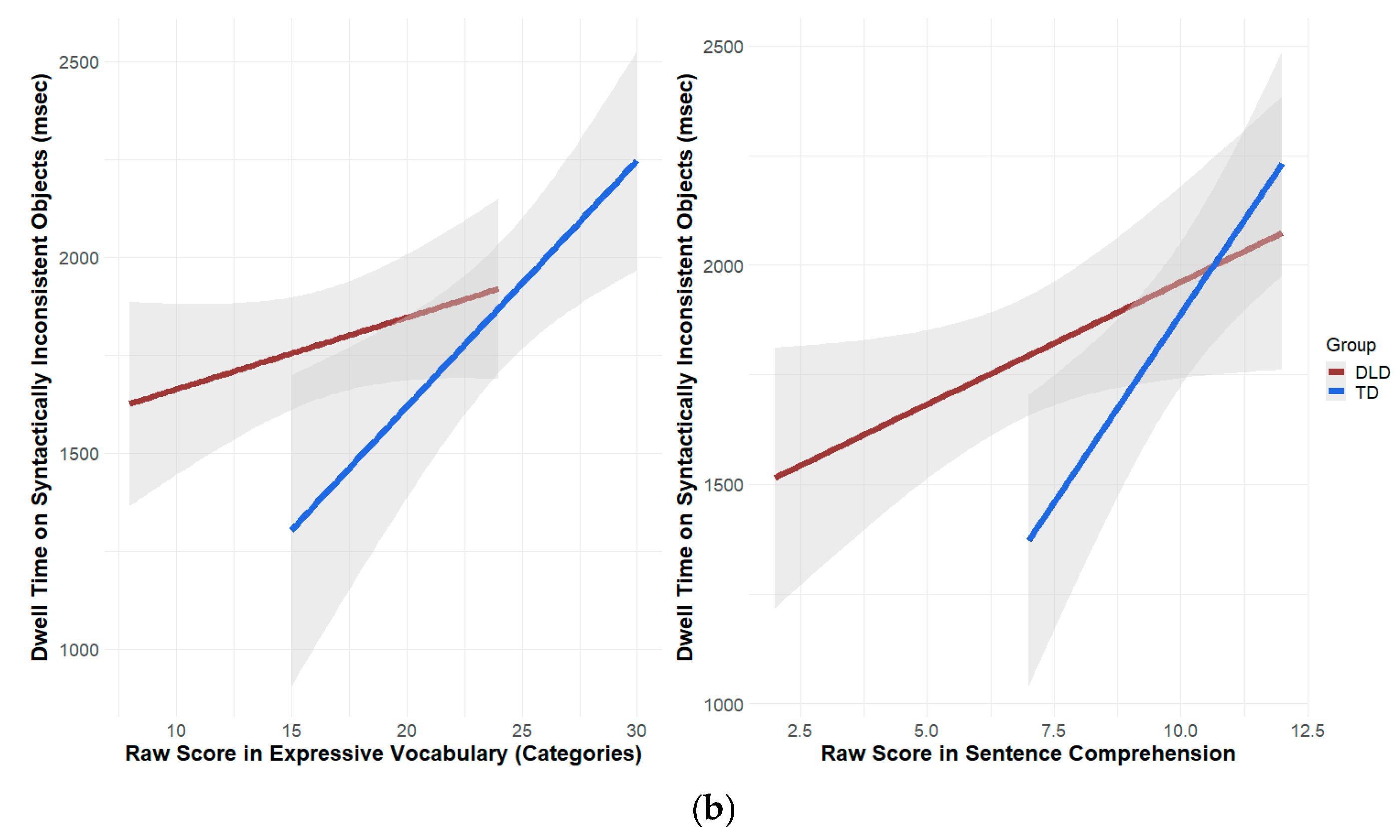

3.3.1. Language Skills and Implicit Measure of Scene Knowledge

Results from the models revealed significant relationships between language skills and the sensitivity towards semantic and syntactic scene violations (see

Figure 5). Children with TD looked longer to the semantically inconsistent objects when their raw scores on the subtests of sentence comprehension (β = 0.107, SE = 0.042,

t = 2.548,

p = 0.022) and error identification/sentence correction (β = 0.191, SE = 0.0788,

t = 2.425,

p = 0.028) increased. Children with DLD only showed this relationship for the subtest on sentence comprehension (β = 0.040, SE = 0.0173,

t = 2.339,

p = 0.019). Both groups looked longer to the syntactically inconsistent objects when their raw scores on expressive vocabulary for categories (TD = β = 0.054, SE = 0.021,

t = 2.603,

p = 0.019; DLD = β = 0.026, SE = 0.008,

t = 3.366,

p < 0.001) and their scores on sentence comprehension (TD = β = 0.131, SE = 0.039,

t = 3.359,

p = 0.004; DLD = β = 0.049, SE = 0.016,

t = 2.980,

p = 0.003) increased.

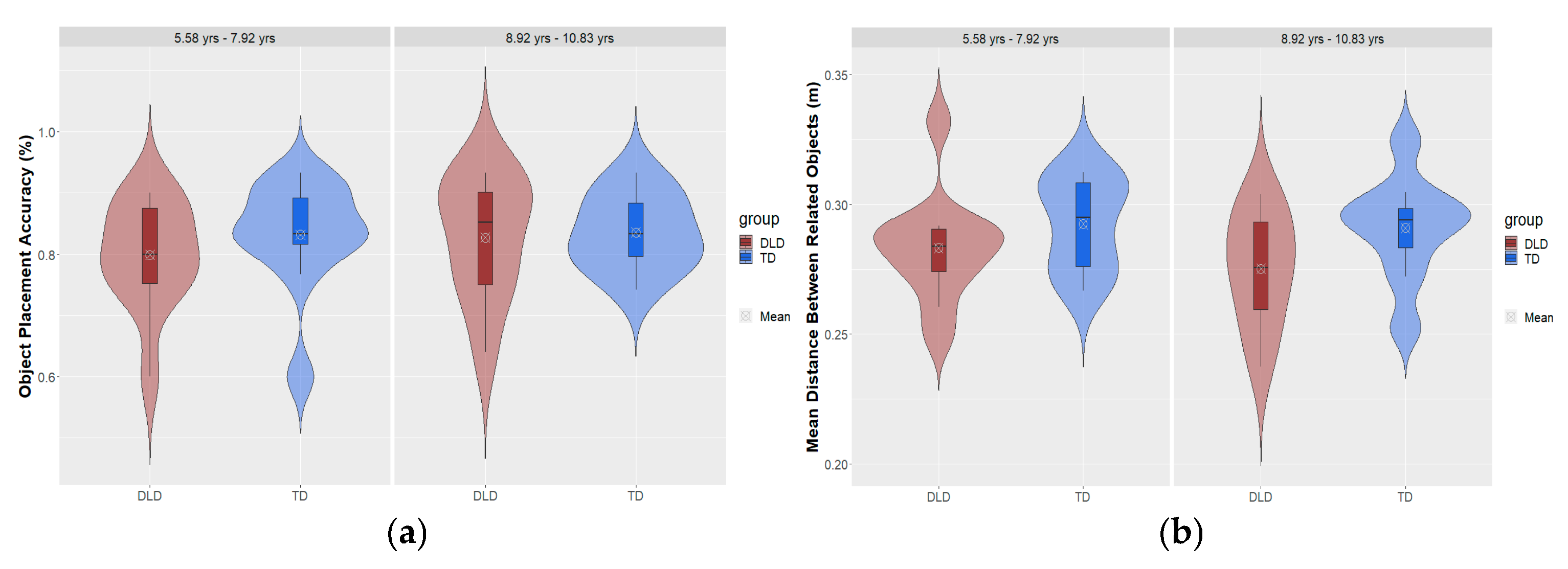

3.4. Explicit measure of Scene Knowledge: Dollhouse Task

Descriptive statistics of object placement accuracy (% of correctly placed objects) and of distance between related objects in m by group and age are displayed in

Table 3 and

Figure 6. Results from the GLMM showed no main effect of group (β = -0.169, SE = 0.151, z = -1.124,

p = 0.261) and age on the dollhouse semantics, i.e., object placement performance (β = -0.294, SE = 0.162, z = -0.187,

p = 0.069) and no interaction effect between group and age (β = -0.086, SE = 0.255, z = -0.338,

p = 0.735): There was no difference on the odd ratios between children with and without DLD in both, the younger age group (Odds Ratio = 1.13, SE = 0.225, z- ratio = 0.638,

p = 0.523) and older age group (Odds Ratio = 1.24, SE = 0.245, z- ratio = 1.078,

p = 0.281). Furthermore, no difference emerged between age groups within children with DLD (Odds Ratio = 1.29, SE = 0.272, z- ratio = 1.185,

p = 0.236). Within the group of TD children, younger children showed a numeric trend towards a better performance (Odds Ratio = 1.40, SE = 0.282, z- ratio = 1.679,

p = 0.093).

With respect to dollhouse syntax, i.e., the distance between related objects with smaller distances indicating higher knowledge about spatial arrangements, the LMM showed no main effect of group (β = 0.011, SE = 0.007, t = 1.498, p = 0.143) and age (β = -0.007, SE = 0.008, t = -0.922, p = 0.363) as well as no interaction effect between group and age (β = 0.007, SE = 0.013, t = 0.570, p = 0.572). Children with and without DLD did not show any difference on dollhouse syntax performance within the younger (β = -0.007, SE = 0.009, t = -0.733, p = 0.468) and older age group (β = -0.014, SE = 0.009, t = -1.4703, p = 0.151) and, age groups did not show any difference within the group of children with DLD (β = 0.109, SE = 0.010, t = 1.033, p = 0.308) and TD (β = 0.003, SE = 0.009, t = 0.353, p = 0.726).

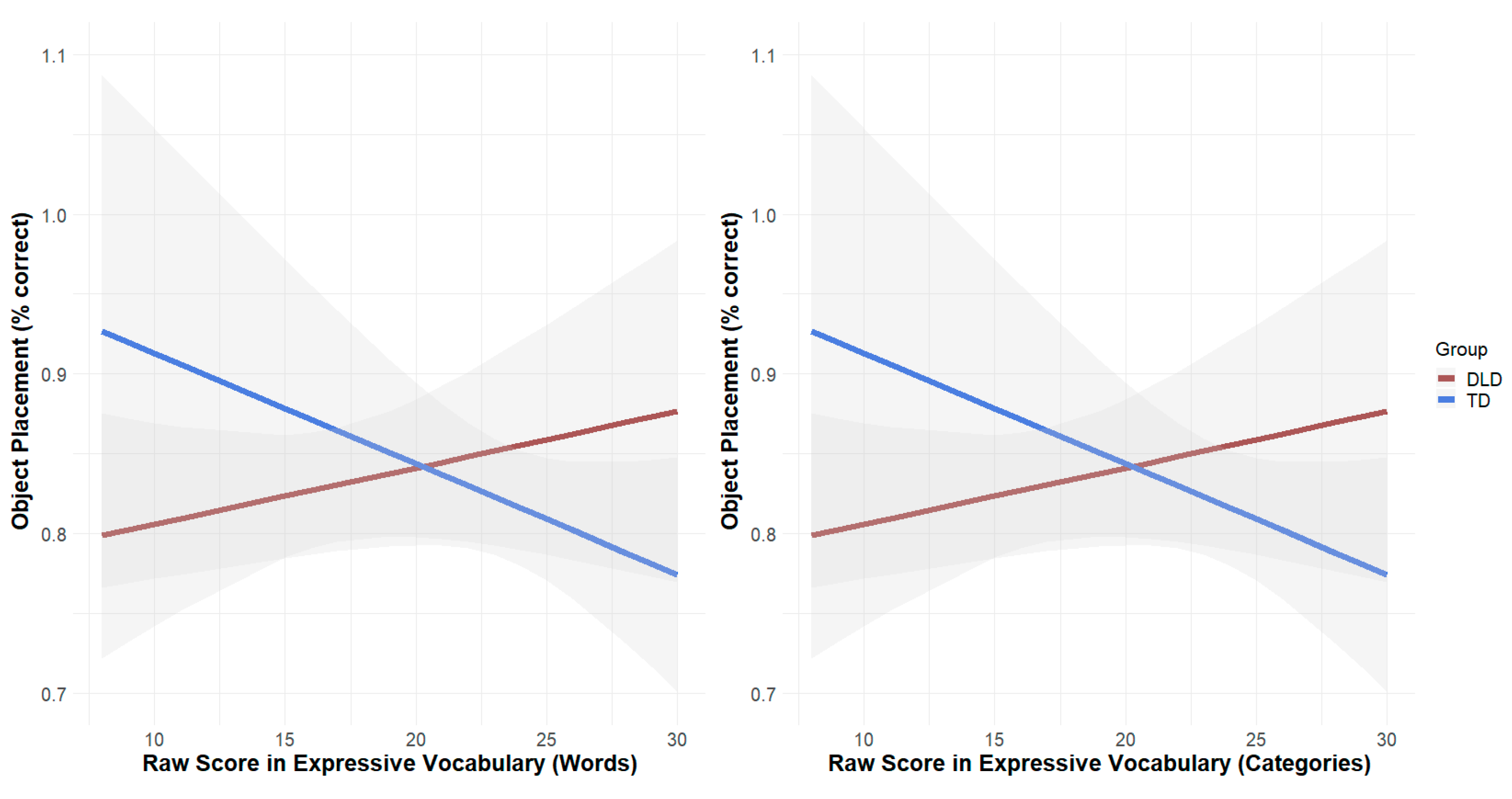

3.4.1. Language Skills and Explicit Measure of Scene Knowledge

The model results showed that language skills of children with DLD predicted their performance in dollhouse semantics with % of correct object placement increasing with their raw scores on expressive vocabulary (for categories: β = 0.009, SE=0.004,

t = 2.193,

p = 0.042 and a numeric trend for words: β = 0.006, SE = 0.003,

t = 1.802,

p = 0.089). Performance in the nonverbal intelligence (CPM-Score) also predicted object placement (β = 0.013, SE = 0.004,

t = 3.252,

p = 0.005). When including CPM scores as a covariate in our model (

Figure 7), the effects of expressive vocabulary for categories (β = 0.005, SE=0.004,

t = 1.234,

p = 0.234) and words on children’s object placement performance were no longer significant (β = 0.002, SE = 0.003,

t = 0.656,

p = 0.52). For TD children, including CPM as a covariate in the model revealed an unexpected pattern: object placement performance decreased significantly with expressive vocabulary for categories (β = -0.014483, SE = 0.005,

t = -2.643,

p = 0.018).

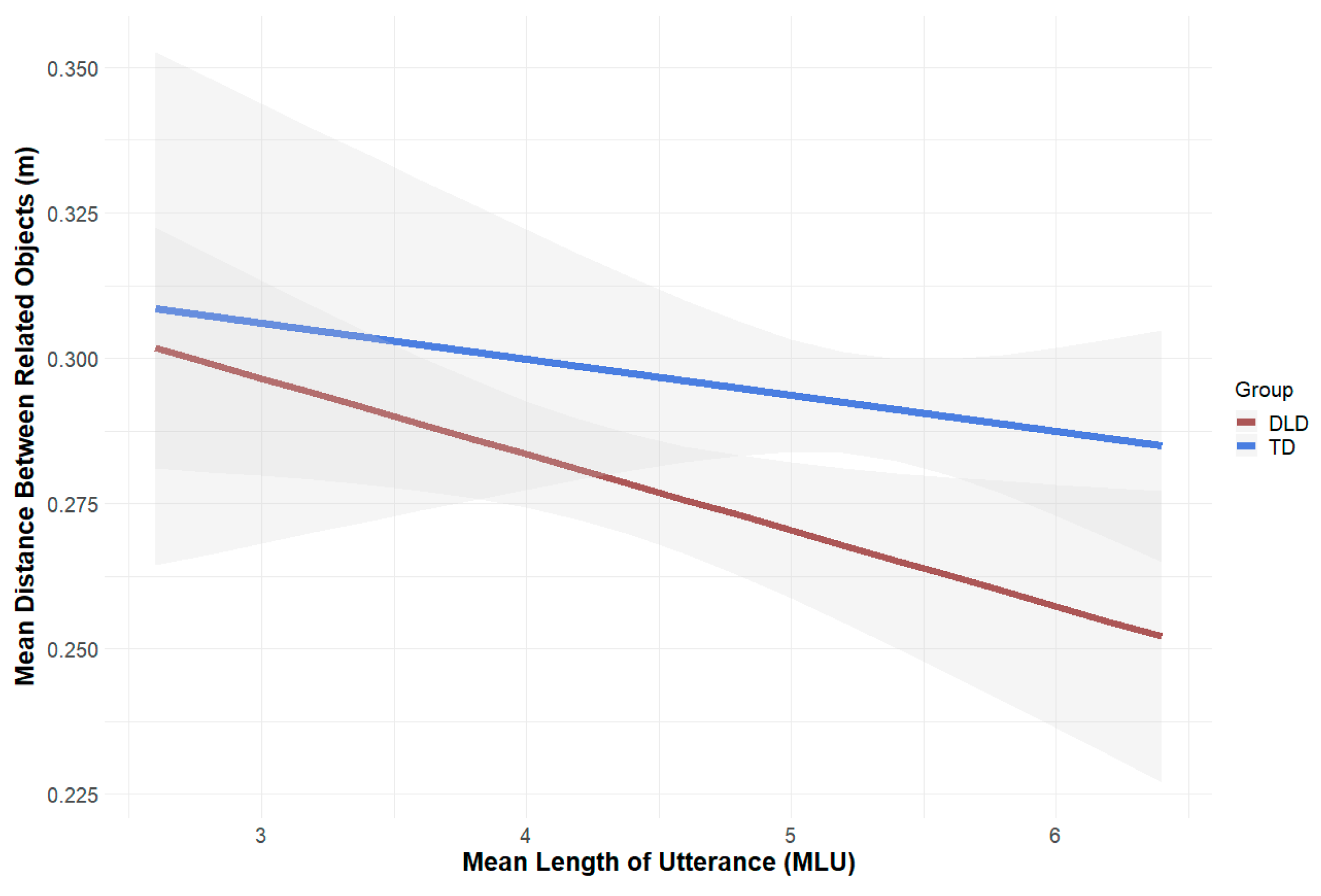

Children with DLD showed a trend towards a positive influence of MLU (mean number of words per utterance) on their syntactic performance, i.e., the distance between related objects (β = -0.012, SE = 0.006,

t = -1.910,

p = 0.073): Children with high MLU scores placed related objects more closely in the dollhouse (see

Figure 8). We ran our models for dollhouse syntax and language scores without adding CPM as a covariate, as CPM score did not affect the performance of children in both groups (DLD = β = 0.00008, SE = 0.001,

t = 0.065,

p = 0.949; TD = β = 0.0009, SE = 0.0006,

t = 1.432,

p = 0.170) and ANOVA on models did not suggest a difference.

4. Discussion

The aim of the study was to uncover potential differences between primary school-aged children with and without DLD in their efficiency of scene grammar processing. To this end, we (1) used an implicit task to investigate the processing of semantic and syntactic violations of scene grammar in everyday visual-spatial scenes by analyzing gaze behavior, and (2) asked children to furnish a dollhouse to assess their explicit scene grammar knowledge, i.e., the assignment and spatial relationship of objects in different rooms. The results can be summarized as follows: Overall, children with and without DLD did not differ in their absolute dwell time on consistent targets as well as on semantically and syntactically inconsistent targets in the free viewing task. However, inconsistency effects were modulated by the factors of age and group. Older children with TD showed semantic and syntactic inconsistency effects, whereas younger participants did not. In children with DLD, the younger age group showed both inconsistency effects, whereas the older children did not. In the dollhouse task, no group differences were found regarding the accuracy of object placement (semantic scene knowledge) or the distance between related objects (syntactic scene knowledge). In both tasks, high language scores (expressive vocabulary and grammar scores) of children with and without DLD were associated with high performance in scene grammar processing. In addition, children with DLD showed age-appropriate but significantly poorer performance on the non-verbal cognitive test (CPM) and the visual perception test (FEW-3) compared to the control group.

4.1. Group Differences and Communalities in Gaze Behaviour towards Scene Inconsistencies

The results of the implicit measure of scene grammar processing partially met our expectations. Against the hypothesis, no group differences in absolute dwell times on targets in the three different conditions appeared, meaning that children with and without DLD looked equally long at consistent and at semantically and syntactically inconsistent targets. Dwell times on consistent targets were lowest in all subgroups (younger and older children with DLD and TD), indicating that all children, regardless of age and language ability, implicitly recognized these violations. Some of the children in both groups also verbalized their recognition during or after the task by saying that some objects do not belong at the locations, where they were shown. In line with previous research [

7,

37], semantic inconsistency effects were more pronounced than syntactic inconsistency effects in children with and without DLD, suggesting a developmental trajectory of being able to recognize the more obvious semantic violations at earlier ages, whereas sensitivity to syntactic scene violations develops later. These results indicate a high degree of comparability in gaze behavior towards everyday scenes in children with and without DLD.

However, when age is considered, a different picture is revealed with regard to the emergence of inconsistency effects. As mentioned before, inconsistency effects become stronger with increasing age. The children with TD showed this developmental trajectory with inconsistency effects for semantic and syntactic violations being absent in the earlier age group and present in the older one. In the DLD group, only the younger children showed inconsistency effects at all. This finding contrasts with previously reported developmental trajectories [

7] and may be due to the following reason: The difference in dwell time was largest between the two young age groups with and without DLD for the consistent condition. While, in accordance with the developmental trajectory, the dwell time for consistent objects remain constant or decreases and dwell times of the semantic and syntactic condition increase as TD children get older, dwell times of children with DLD increased in all three conditions. Thereby, the greatest increase was observed for the consistent condition. In line with the PDH, this pattern may reflect compensatory strategies, indicating a greater need for prolonged exploration of typical (consistent) scenes in order to extract scene regularities before violations within scenes can become the focus of attention. Thus, children with DLD seemed to show a different or delayed developmental trajectory than the control group, characterized by a prolonged preference for looking at consistent rather than inconsistent scenes. The difference in dwell times between conditions decreases in older children, because dwell times for consistent objects still increase, and to a greater extent than dwell times for semantically and syntactically inconsistent objects. As a result, the apparent inconsistency effect disappears. Thus, children with DLD seem to focus persistently on consistent objects, rather than showing a growing interest in scene violations. The absence of stable inconsistency effects in children with DLD confirms the results of Helo and colleagues [

37], who found inconsistency effects in this group only for the mixed condition (semantic plus syntactic violation), but no effects for either semantic-only or syntactic-only violations. Our inclusion of older children of primary school age revealed a delay in the development of scene grammar in relation to DLD, which (1) persists beyond preschool age and (2) is more pronounced for the perception of syntactic scene inconsistencies.

As expected, we found stable relationships between language skills and the efficiency of scene grammar processing, confirming previous research [

7,

37]. Both groups showed a higher sensitivity to semantic and syntactic scene violations (expressed in longer dwell times) the higher their scores were in expressive vocabulary and grammar skills (sentence comprehension, error identification and MLU). Thus, language and visuospatial processing appear to be linked more closely than often assumed. Such a link could also explain the lower performance of the children with DLD in the visual perception test, again supporting a domain-general view on DLD. According to this account, processing deficits in superordinate higher cognitive functions, such as the central executive as part of WM, which integrates visual and linguistic information, contribute to the manifestation of DLD. Taken together, the development of sensitivity towards scene violations in children with DLD appears to lag behind due to the influence of language skills on scene grammar processing.

4.2. Group Differences and Communalities in Object Placement Accuracy and Object Distance in the Dollhouse Task

Against our hypothesis, the two groups did not differ in their accuracy of object placement and in the distance between the arranged local objects and their anchors. Children with and without DLD placed objects in the appropriate rooms with a very high mean accuracy of 82%. In addition, there was no difference between the younger and older children. Combined with a similar study by Öhlschläger and Võ [

7], who applied the dollhouse task with TD children aged two to four years, our results suggest an age-related progression of explicit scene knowledge from 25% correctly placed objects in 2-year olds to 82% in 6-11-year olds. The lack of group effects may be due to the relatively low demands of this task for primary school-aged children and the fact that most of the objects were highly frequent and familiar. In future studies, it would be interesting to investigate whether there are group differences when the task is performed with low-frequency objects and more rooms, such as a home office, children’s room or garage.

As expected, the participants’ language skills predicted their performance in object placement and distance of objects. However, this relationship was also influenced by the factors of group and nonverbal cognitive ability (CPM score): Only children with DLD showed higher performance in object placement as their vocabulary score were higher. Since this correlation was only present in children with DLD and disappeared when controlling for the CPM score, this result must be interpreted with caution.

One explanation for the influence of language ability on performance in the dollhouse task could be that the children solved this seemingly non-verbal task verbally, using inner speech and self-talk, e.g., about object names, properties or appropriate rooms as they placed the objects. Children with poorer language skills placed objects more often incorrectly and at greater distances from their anchors. Poorer language skills when attempting to solve this task verbally may have had a negative effect on task performance, or at least, self-talk was not as supportive as for children with TD. Language ability may also have played a role in the lower performance of the DLD group in the visual perception test, as the children often solved the task by thinking aloud.

4.3. Limitations and future research

The findings of the present study are based on rather small sample sizes, especially for the age-relative group comparison. This should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results, as they may be less generalizable. In addition, heterogeneity of group may have served as influencing factor, as children diagnosed with DLD tend to showed very different linguistic profiles (e.g., focus on lexical semantic or grammatical problems). Another factor may be the different degrees of severity of DLD. The sample in this study consisted of children with a rather high severity. Conversely, this means that the results cannot be extrapolated to less severely affected individuals with DLD. To substantiate the findings regarding the efficacy of scene grammar processing in the context of DLD, it is thus imperative to confirm the results with a larger sample size, with subgroups of children showing lexical-semantic or grammatical deficits only and a second control group of younger TD children with similar language levels compared to the clinical group.

Furthermore, the exact influence of non-verbal cognitive abilities on scene processing, as tested by the CPM, remains an open question. The relationship was significant only in children with DLD, who also showed reduced performance on the visual perception test FEW-3. The CPM can be considered as a visual form related task comparable to the FEW-3. Therefore, it cannot be completely ruled out that the apparent correlation between non-verbal cognitive performance and visuospatial scene processing is an artefact of the similarity between the two tasks. Future studies should therefore apply a wider range of tests for nonverbal intelligence with different cognitive demands.

In addition to the dollhouse task, which could be modified in terms of complexity, explicit knowledge of scene grammar could also be evaluated using other behavioral tasks. For instance, participants could be tasked with correcting scene violations that have been presented to them, describing prototypes of scenes, or with identifying and adding missing local and anchor objects.

In subsequent research, it would be worthwhile to concentrate on cross-linguistic comparisons of scene grammar development and to consider cultural differences. This is because children are raised in different environments that are shaped by their culture. This also affects how indoor scenes of the same rooms in different cultures look like. It would therefore be interesting to investigate how the perception of scene grammar develops across children growing up in various cultures.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the study suggests subtle problems in visuospatial processing in children with DLD, involving not only the perception and processing of abstract visual forms and patterns, but also of real-world visual scenes that constitute the external environment and thus provide a framework for language acquisition. Supporting the domain-general view of DLD, this finding also has clinical relevance. For instance, the existence of unperceived problems in components of non-verbal WM (central executive or visuospatial sketchpad), which manifest themselves in altered visual-spatial processing, has the potential to result in delays in the progress of therapy, particularly if visual materials are utilized extensively during treatment. Furthermore, the acquisition of mental concepts pertaining to spatial-positional relationships, including linguistic knowledge such as word meanings, word forms and grammar rules, may be influenced by visual-spatial perception that differs from that of typically developing children. Thus, it may be worthwhile to consider children’s non-verbal WM capacities in the diagnostic process in order to more accurately determine the specific intervention needs of each individual child with DLD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, DB, DT, NK, GS, CK, and MV; methodology, DB, DT, CK, and MV; software, DB, DT, CK, and MV; validation, DB, DT, NT, GS, CK, and MV; formal analysis, DB and DT; investigation, DB and DT.; resources, CK, GS, and MV; data curation, DB and DT; writing—original draft preparation, DB and DT.; writing—review and editing, DB, DT, NT, GS, CK, and MV; visualization, DB, DT, CK, and MV; supervision, CK and MV; project administration, CK, GS, and MV; funding acquisition, CK, GS, and MV. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), 222641018-SFB/TRR 135 (Projects C3 and C7).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Psychology Department at the University of Gießen (protocol code: 2021-0037, date of approval: 09.10.2021).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank all children and parents, who participated in the study, as well as all local speech and language pathologists, the Sprachheilzentrum Meisenheim, and the Edelsteinklinik Bruchweiler (intervention centres for speech and language therapy in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany) for the opportunity to recruit and test participants. We also thank Theresa Henke, Judth Hollnagel, Ronja Schnellen, and Jonathan Mader for their help in data acquisition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Võ, M. L.-H. The Meaning and Structure of Scenes. Vision Research 2021, 181, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackema, P. Arguments and Adjuncts. In Syntax – Theory and Analysis: An International Handbook. Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science (HSK); Kiss, T., Alexiadou, A., Eds.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, 2015; pp. 246–273. Available online: http://www.degruyter.com/view/product/433702.

- Hagoort, P. Interplay between syntax and semantics during sentence comprehension: ERP effects of combining syntactic and semantic violations. Journal of cognitive neuroscience 2003, 15, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öhlschläger, S.; Võ, M. L.-H. SCEGRAM: An image database for semantic and syntactic inconsistencies in scenes. Behav Res 2017, 49, 1780–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayner, K.; Castelhano, M. S.; Yang, J. Eye movements when looking at unusual/weird scenes: Are there cultural differences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 2009, 35, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spotorno, S.; Malcolm, G. L.; Tatler, B. W. Disentangling the effects of spatial inconsistency of targets and distractors when searching in realistic scenes. Journal of Vision 2015, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öhlschläger, S.; Võ, M. L.-H. Development of scene knowledge: Evidence from explicit and implicit scene knowledge measures. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 2020, 194, 104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streri, A.; de Hevia, M.D. “How do human newborns come to understand the multimodal environment? .” Psychonomic bulletin & review 2023, 30, 1171–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbury, C.F.; Gooch, D.; Wray, C.; Baird, G.; Charman, T.; Simonoff, E.; Pickles, A. The impact of nonverbal ability on prevalence and clinical presentation of language disorder: Evidence from a population study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2016, 57, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop DVM; Snowling MJ; Thompson PA; Greenhalgh T. CATALISE consortium: A Multinational and Multidisciplinary Delphi Consensus Study. Identifying Language Impairments in Children. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. V. M.; Snowling, M. J.; Thompson, P. A.; Greenhalgh, T.; CATALISE-2 consortium. Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines 2017, 58, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüke, C.; Kauschke, C.; Dohmen, A.; Haid, A.; Leitinger, C.; Männel, C.; Penz, T.; Sachse, S.; Scharff Rethfeldt, W.; Spranger, J.; Vogt, S.; Niederberger, M.; Neumann, K. Definition and terminology of developmental language disorders - Interdisciplinary consensus across German speaking countries. PLoS ONE 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S.; Broc. , L.; Olive,T.; Mathy, F. Reduced deficits observed in children and adolescents with developmental language disorder using proper nonverbalizable span tasks. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2020, 96, pp.103522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Alonso, J. C.; Atit, K. Different abilities controlled by visuospatial processing. In Visuospatial processing for education in health and natural sciences; Castro-Alonso, J.C., Ed.; Springer, 2019; pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A. The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory? Trends in cognitive sciences 2000, 4, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gathercole, S. E.; Baddeley, A. D. Phonological Memory Deficits in Language Disordered Children: Is There a Causal Connection? Journal of Memory and Language 1990, 29, 336–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Lely, H. Domain-specific cognitive systems: Insight from Grammatical-SLI. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2005, 9, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, L. M.; Gathercole, S. E. Short-term and working memory in specific language impairment. International. Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 2006, 41, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archibald, L. M.; Gathercole, S. E. Visuospatial immediate memory in specific language impairment. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 2006, 49, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, E.; Boerma, T. Do children with developmental language disorder (DLD) have difficulties with interference control, visuospatial working memory, and selective attention? Developmental patterns and the role of severity and persistence of DLD. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 2020, 63, 3036–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, J. A.; Conti-Ramsden, G.; Page, D.; Ullman, M. T. Working, declarative and procedural memory in specific language impairment. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior 2012, 48, 1138–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, K. D.; Kohnert, K. Sustained attention in children with primary language impairment: a meta-analysis. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 2011, 54, 1372–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolak, E.; McGregor, K. K.; Arbisi-Kelm, T.; Eden, N. Sustained attention in developmental language disorder and its relation to working memory and language. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 2020, 63, 4096–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botting, N.; Marshall, C. Domain-specific and Domain-general Approaches to Developmental Disorders. In The Wiley Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology; Centifanti, L.C., Williams, D.M., Eds.; Wiley: London, United Kingdom, 2017; pp. 1399–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vugs, B.; Cuperus, J.; Hendriks, M.; Verhoeven, L. Visuospatial working memory in specific language impairment: A meta-analysis. Drug Development Research 2013, 34, 2586–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, S.; Fox, A. B.; Green, S.; Alt, M.; Hogan, T. P.; Petscher, Y.; Cowan, N. Working Memory Profiles of Children With Dyslexia, Developmental Language Disorder, or Both. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research 2019, 62, 1839–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, J. A.; Conti-Ramsden, G. Long-term memory: A review and meta-analysis of studies of declarative and procedural memory in specific language impairment. Topics in language disorders 2013, 33, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, D.; Vesker, M.; Schwarzer, G.; Kauschke, C. A Multimodal Comparison of Emotion Categorization Abilities in Children With Developmental Language Disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 2021, 64, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapparrata, N. M.; Brooks, P. J.; Ober, T. Developmental Language Disorder Is Associated With Slower Processing Across Domains: A Meta-Analysis of Time-Based Tasks. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research 2023, 66, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara-Díaz, M.F.; Beltrán Rojas, J.C.; Aponte Rippe, Y. Visual attention and phonological processing in children with developmental language disorder. Frontiers in Communication 2024, 9, 1386279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helo, A.; Ommen, S.; Pannasch, S.; Danteny-Dordoigne, L.; Rämä, P. Influence of semantic consistency and perceptual features on visual attention during scene viewing in toddlers. Infant behavior and development 2017, 49, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffongelli, L.; Öhlschläger, S.; Võ, M. L.-H. The development of scene semantics: First ERP indications for the processing of semantic object-scene inconsistencies in 24-month-olds. Collabra: Psychology 2020, 6, 17707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, R.; Brooks, P. J.; Powers, K. L.; Gillespie-Lynch, K.; Lum, J. A. Statistical learning in specific language impairment and autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 2016, 7, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, M.; Pierpont, E. Specific Language Impairment is not Specific to Language: the Procedural Deficit Hypothesis. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior 2015, 41, 399–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, E.; Vissers, C. Behind the Scenes of Developmental Language Disorder: Time to Call Neuropsychology Back on Stage. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2019, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, M.; Clark, G.; Pullman, M.; Lovelett, J.; Pierpont, E.; Jiang, X.; Turkeltaub, P. The neuroanatomy of developmental language disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nature Human Behaviour 2024, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helo, A.; Guerra, E.; Coloma, C.J.; Aravena-Bravo, P.; Rämä, P. Do Children With Developmental Language Disorder Activate Scene Knowledge to Guide Visual Attention? Effect of Object-Scene Inconsistencies on Gaze Allocation. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 12, 796459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann, F. Sprachstandserhebungstest für Kinder im Alter zwischen 5 und 10 Jahren, 3rrd ed. Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bulheller, S.; Hacker, H. CPM - Colored Progressive Matrices, 3rd ed.; Pearson: London, United Kingdom, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hammill, D.D.; Pearson, N.A.; Voress, J.K. Developmental Test of Visual Perception – DTVP-3, 2nd ed.; ProEd: Austin, Texas, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Büttner, G.; Dacheneder, W.; Schneider, W.; Hasselhorn, M. Frostigs Entwicklungstest der visuellen Wahrnehmung-3, 1st ed.; Pearson: London, United Kingdom, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kauschke, C.; Dörfler, T.; Sachse, S.; Siegmüller, J. Patholinguistische Diagnostik bei Sprachentwicklungsstörungen, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: München, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kauschke, C.; Lawatsch, K.; Tenhagen, A.; Dörfler, T. Exploring grammatical development in children aged 2; 6 to 7: a novel approach using elicited production. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 2024; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardos, A.; Kümmerer, M.; Press, O.; Bethge, M. DeepGaze IIE: Calibrated prediction in and out-of-domain for state-of-the-art saliency modeling. Proceedings of IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, 12899-12908., Canada (10.17.10.2021). [Google Scholar]

- Tullis, T.; Albert, B. Measuring the User Experience. Collecting, Analyzing, and Presenting Usability Metrics, 2nd ed.; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Turini, J. , Võ, M. L.-H. Hierarchical organization of objects in scenes is reflected in mental representations of objects. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 20068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, M. R. Statistics of high-level scene context. Frontiers in Psychology 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baayen, R. H.; Davidson, D. J.; Bates, D. M. Mixed-effects modelling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language 2008, 59, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B. M.; Walker, S. C. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P. B.; Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software 2017, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).