1. Introduction

Nanotechnology is one of the fastest growing and most promising scientific fields, with applications ranging from medicine, electronics, catalysis, cosmetics to targeted drug delivery [

1]. Among engineered nanomaterials, nanoparticles offer unique physicochemical properties due to their small size and high surface-to-volume ratio, allowing them to interact closely with biological systems [

2]. However, their increasing use raises serious concerns about potential health and environmental risks throughout their entire life cycle, from production and use to disposal and release into the environment [

3].

Silicon dioxide nanoparticles are among the most used nanomaterials due to their stability, biocompatibility, and anti-agglomeration properties [

4]. These particles are widely present in consumer products such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, food additives and inks, and are increasingly used in biomedical applications including drug and gene delivery and cancer therapy [

5]. However, due to their ability to enter cells and accumulate in tissues, there is a growing need to assess their biocompatibility, biodistribution and potential toxicity [

6].

Traditional in vivo toxicity testing using rodents, although informative, faces ethical limitations, high costs and time constraints [

7]. As an alternative, the zebrafish model has gained importance in nanotoxicology due to its genetic similarity to humans, transparency during early development and suitability for high-throughput screening [

8]; in particular, transgenic zebrafish lines expressing tissue-specific fluorescent proteins allow real-time visualization of the developmental and vascular effects of nanomaterials [

9].

In this study were investigated the in vivo behavioral effects of SiO₂NPs, using the sociability test and the color preference test, along with histological and biochemical analyses. We aimed to evaluate how these nanoparticles influence the social behavior and sensory preferences of zebrafish, as well as possible structural and biochemical changes at the organ level, with a focus on biomarkers of OS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Zebrafish

Wild-type AB strain zebrafish (6–8 months old), with a balanced sex ratio (1:1, male: female), were maintained under standard laboratory conditions, following a 14:10 light/dark cycle, and constant temperature of 28 °C, pH 7.2 and a conductance range of 470–520 μS, according to established protocols [

10]. For this experiment, adult zebrafish were maintained in 5 L experimental aquaria, fed TetraMin flakes twice daily, and acclimated to experimental conditions for a week prior to the study. All experiments involving the use of zebrafish were carried out in accordance with the EU Commission Recommendation (2007), Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on guidelines for housing, care and the protection of animals used for experimental purposes [

11]. The experiments were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as the legislation of Romania and the European Union regarding the use of animals in biomedical research. Also, all experiments and procedures were conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Biology ("Alexandru Ioan Cuza" University of Iasi), Approval Code: 100/10.12.2024. All procedures were performed by limiting the number of individuals, according to the ARRIVE guidelines [

12]. At the end of the experiment, zebrafish were euthanized by rapid cooling in ice-cold water (2-4 °C) for 10 minutes. This method is commonly used for small fish and minimizes distress [

13].

2.2. Materials

Silicon dioxide nanoparticles (SiO

2NPs, CAS number 7631-86-9, particle size 50 nm) were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, Missouri, USA). The SiO

2NPs suspension was sonicated for 30 minutes before use to ensure uniform dispersion. The concentrations were chosen based on previous studies to reflect realistic environmental and pharmacological conditions for zebrafish exposure [

14,

15].

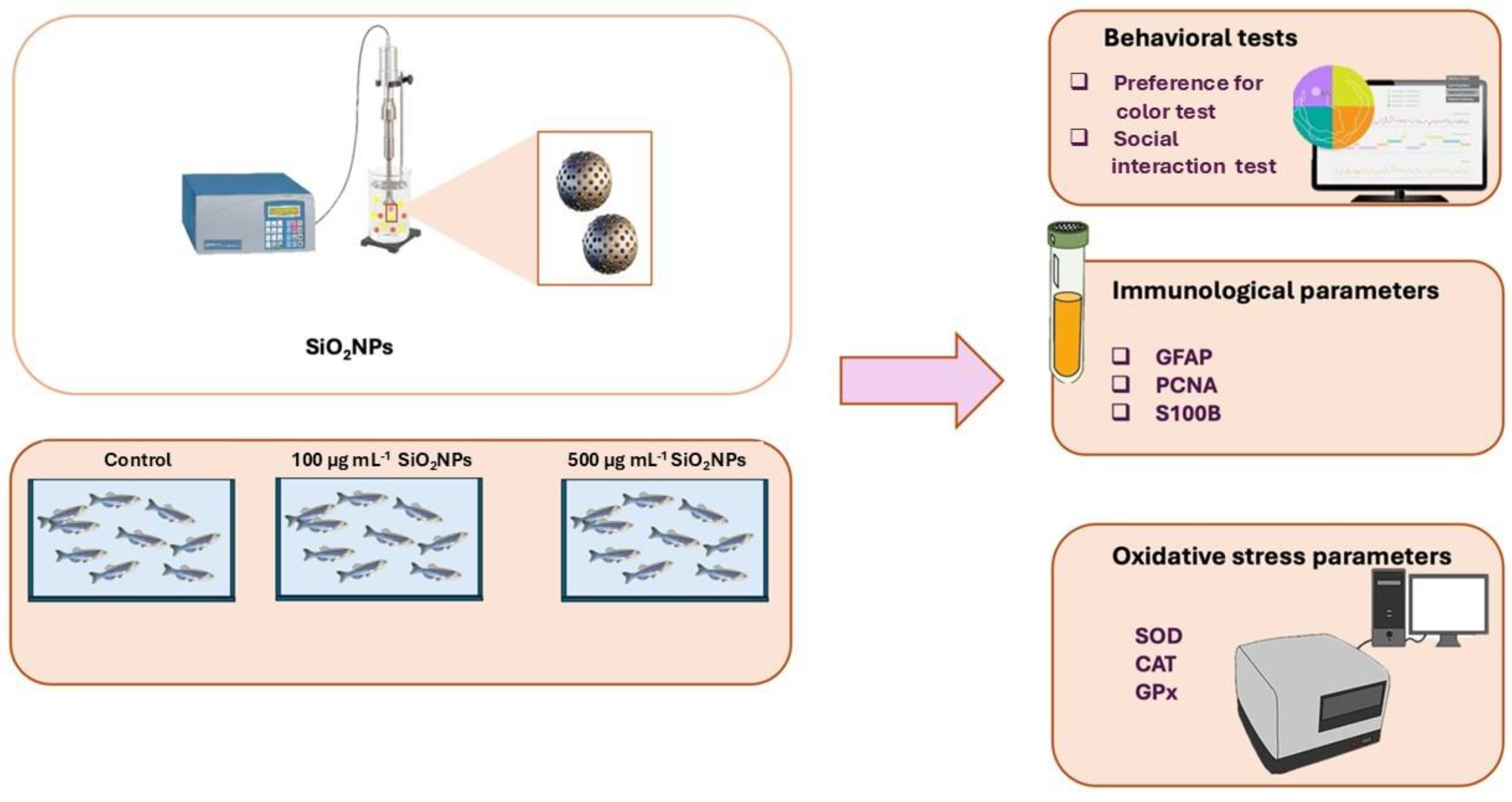

2.3. Zebrafish Exposed to SiO2NPs

Adult zebrafish were exposed to two concentrations of silica nanoparticles (100 μg mL

-1 and 500 μg mL

-1)

, under controlled laboratory conditions. Following exposure, behavioral tests (social test, preference for color test), OS markers (CAT, SOD, GPx), and immunological parameters (GFAP, PCNA, S100B) were assessed to evaluate the potential neurotoxic and physiological effects of the nanoparticles (

Figure 1).

2.4. Experimental Setup for Behavioral Testing

Social interaction and color preference of zebrafish exposed to SiO₂NPs for 7 days were observed using a T-maze. The experimental apparatus consisted of three arms: left, right, and center, with a camera positioned above to record behavior. For the color preference test, the maze was modified by coloring the right arm green and the left arm red. For the social interaction test, the left arm of the maze contained a transparent compartment where conspecifics were placed, while the other arm remained empty. This configuration allowed the measurement of social preference based on the zebrafish's arm choice.

2.4. Acclimation for Preference Test

Behavioral assessment in the color preference test was conducted using a T-maze. The procedure included an acclimation phase followed by the evaluation of specific behavioral parameters indicative of locomotor activity, anxiety-like behavior, and preference patterns. To ensure reliable behavioral data, zebrafish underwent a multi-day acclimation period to the T-maze. On the first day, the entire group of adult zebrafish was placed in the maze for 20 minutes. On subsequent days, both the number of fish and exposure time were gradually reduced: half of the group for 10 minutes, 3-4 fish for 8 minutes, 2-3 fish for 5 minutes, and finally 1-2 fish for 5 minutes. On the final day, individual fish were placed in the maze for 5 minutes. Acclimation success was evaluated based on swimming activity, fish that stopped frequently or did not swim at all were excluded from further testing [

16].

2.5. Behavioural Parameters for Color Preference

Total distance moved (cm) was used as an indicator of general locomotor activity and spatial exploration. Thus, high values of this parameter reflect increased activity and exploratory behavior, while low values may suggest responses that may be associated with anxiety or motor disorders. velocity (cm s-1) represents the overall speed at which zebrafish swim and reveals their level of locomotor activity, as well as possible effects of exposure to toxic substances or environmental stressors. A decrease in this parameter may indicate stress, anxiety, or lethargy, while an increase in velocity may suggest hyperactivity, agitation, discomfort, or flight responses associated with an acute stress response.

The time spent in the left and right arms of the apparatus during the 5-min test was recorded separately. A longer duration in one of the arms may indicate a preference for that side or a color-based attraction, while a reduced time may suggest avoidance behavior possibly related to anxiety. Additionally, research has shown that zebrafish prefer the color red over green, a preference that is associated with easier detection of longer wavelength colors in the aquatic environment, as well as the possible association of red with food sources such as zooplankton or microcrustaceans containing carotenoids [

17].

Cumulative duration of mobility (s) refers to the total time the fish were actively moving, reflecting overall activity levels. In contrast, cumulative duration of immobility (s) corresponds to periods of inactivity, which can be interpreted as freezing behavior, commonly associated with anxiety-like states in zebrafish.

In addition, rotational behavior was measured in both clockwise and counterclockwise directions. Repetitive circles or asymmetrical rotational patterns may suggest changes in motor coordination or increased levels of anxiety.

2.6. Behavioural Parameters for Social Interaction Test

For the social interaction test, a set of behavioral parameters was analyzed to assess the social responsiveness of zebrafish. Total distance moved (cm) was used as an indicator of general locomotor activity and exploratory behavior, particularly in proximity to conspecifics. Increased distance may reflect heightened exploratory drive and social motivation, while reduced distance may indicate anxiety or social avoidance.

Swimming velocity (cm s⁻¹) was also measured as a complementary parameter reflecting general motor activity. Lower velocity values may be associated with hypoactivity or anxiety-like responses, whereas elevated values suggest active engagement with the environment.

Additionally, time spent in the left and right arms of the testing apparatus was quantified. One arm contained a transparent compartment housing conspecifics (stimulus arm), while the other remained empty (neutral arm). A longer duration in the stimulus arm was interpreted as an indicator of social preference or affiliative behavior, whereas increased time in the neutral arm may be indicative of social avoidance or heightened stress levels.

2.7. Preparation of Homogenates and Biochemical Parameter Analysis

After completion of behavioral testing, zebrafish were individually placed in a glass dish containing ice-cold water (2–4 °C) for 10 minutes, followed by rapid euthanasia, as previously described by Jorge et al. [

18]. The following day, fish from the same group were individually weighed (~3–9 mg) and homogenized in a potassium phosphate extraction buffer (0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 1.15% KCl) at a ratio of 1:10 (weight/volume). The homogenates were then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 15 minutes, and the resulting supernatant was used for subsequent biochemical parameter analyses.

2.7.1. Superoxide Dismutase Activity Determination

In this study, SOD activity was assessed according to the protocol established by Winterbourn et al. [

19]. Briefly, the assay monitored the enzyme’s capacity to inhibit the reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) by superoxide radicals generated through riboflavin photoreduction. The reaction mixture contained 0.067 M potassium phosphate buffer, enzyme extract, 0.1 M EDTA, 0.12 mM riboflavin, and 1.5 mM NBT solution. Absorbance was measured at 560 nm. The specific activity of SOD was expressed in enzymatic units per mg of protein, with protein concentration determined by the Bradford method [

20].

2.7.2. Catalase Activity Determination

Catalase activity was assessed using a simple colorimetric method described by Sinha [

21]. For each sample, 125 µL of enzyme homogenate was combined with 125 µL of 0.16 M hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) solution. After a 3-minute incubation, the reaction was terminated by adding 500 µL of potassium dichromate–glacial acetic acid solution, followed by incubation at 95 °C for 10 minutes. Subsequently, samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes, and the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 570 nm. Catalase activity was expressed as micromoles of H₂O₂ decomposed per minute per milligram of protein.

2.7.3. Glutathione Peroxidase Activity Determination

Glutathione peroxidase activity was assessed following the protocol outlined by Fukuzawa and Tokumura [

22]. This method relies on the enzyme’s capacity to catalyze the decomposition of H₂O₂ using reduced glutathione (GSH) as a substrate, resulting in the formation of oxidized glutathione (G-S-S-G) and water. To each sample, 78 µL of enzyme extract, 475 µL of 0.25 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 36 µL of 25 mM EDTA, and 36 µL of 0.4 M sodium azide (NaN₃) solution were added. Following incubation at 37 °C for 10 minutes, 50 µL of 50 mM GSH solution and 36 µL of 50 mM H₂O₂ solution were introduced. The reaction was terminated by adding 730 µL of 7% metaphosphoric acid, and samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Subsequently, 100 µL of the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, mixed with 1270 µL of 0.3 M disodium phosphate solution and 136 µL of 0.04% DTNB solution. After a 10-minute incubation, absorbance was recorded at 412 nm. Specific GPx activity was then calculated in enzymatic units per mg protein, with protein concentration determined by the Bradford method [

20].

2.8. Histological and Immunohistological Analysis

Organ samples were fixed in Bouin’s solution for 24 hours. Approximately 0.5 cm thick slices were dehydrated using an ethanol gradient with decreasing concentrations, followed by clarification in xylene and embedding in paraffin. After sectioning with a microtome, 10 slides from each paraffin block were selected, specifically stained, and examined under an Olympus CX41 microscope. The sections were initially stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), followed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) using three primary antibodies: Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), S100 calcium-binding protein B (S100B), and Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). The sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in ethanol, and subjected to antigen retrieval by microwaving for 10 minutes at 95 °C in a 10 mmol citrate acid buffer, pH 6. After cooling for 20 minutes, the slides were washed twice in PBS for 5 minutes each. The sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase activity, then rinsed with PBS. Primary antibodies were applied and incubated overnight at 4 °C in a humidified chamber. The following antibody dilutions were used: and S100B at 1:1000, and PCNA at 1:250. On the following day, the slides were washed three times in PBS for 5 minutes each and then incubated with secondary antibodies. Goat anti-rabbit IgG was used as the secondary antibody for all three markers. The slides were developed using 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB), and finally counterstained with hematoxylin.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test in GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Potential outliers were identified through Grubbs’ test and excluded where appropriate. Depending on the outcome of the normality assessment, data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Social Interaction Test

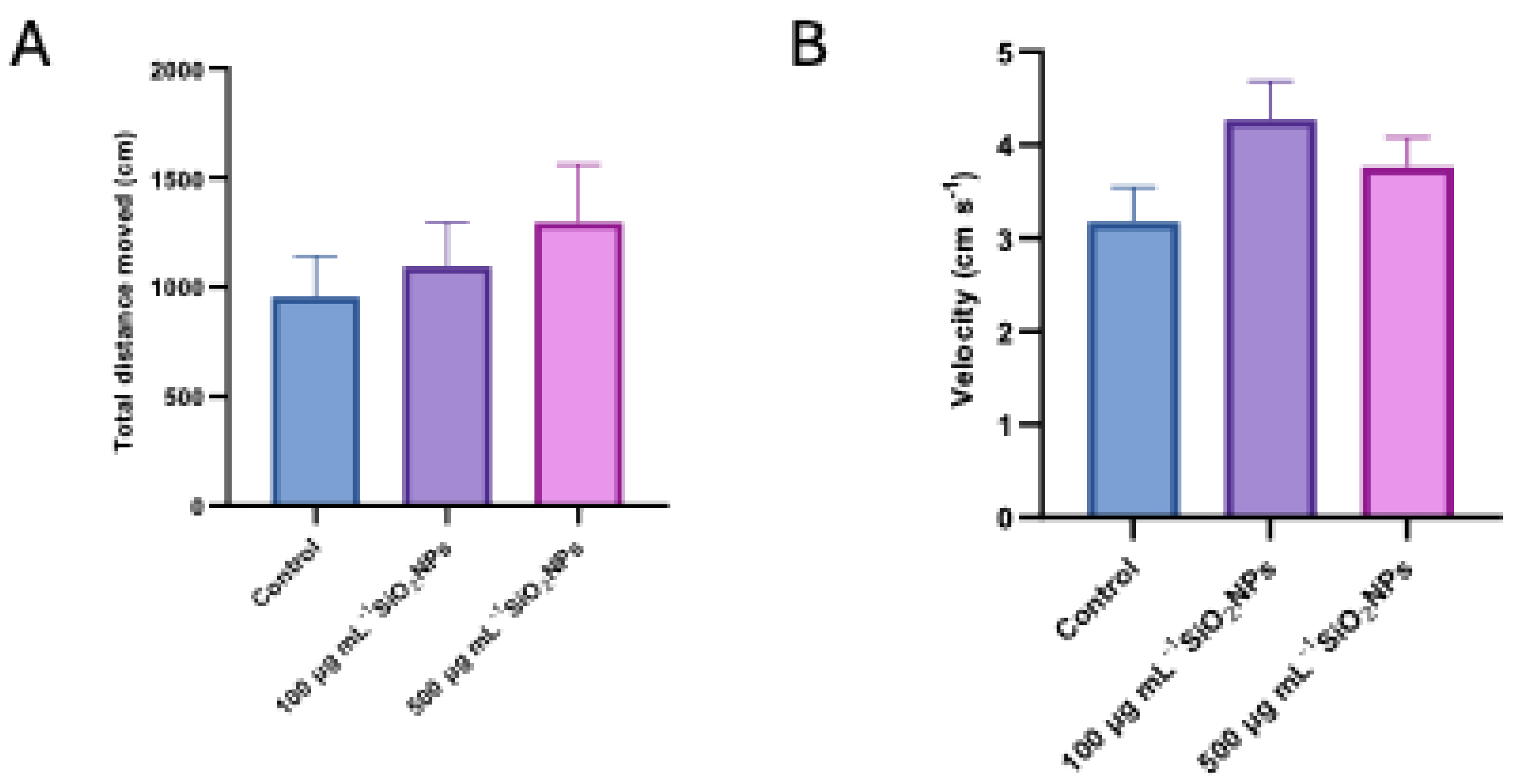

The results of the social interaction test show a locomotor activity tendency to increase with increasing concentration of silicon oxide nanoparticles (

Figure 2). The groups that were administered nanoparticles had increased values compared to the control group, but there were no significant differences, the furthest distance traveled was presented by the group exposed to the dose of 500 μg mL

-1.

This tendency may indicate a possible stimulation of locomotor behavior under the influence of SiO₂ nanoparticles, possibly as a result of changes at the neurochemical level, such as increased levels of dopamine or serotonin, which are associated with increased exploratory activity. At the same time, the increase in movement could also be interpreted as a possibility of stress or agitation response, caused by exposure to nanomaterials. Also, in the case of swimming speed, visible differences are observed, but there are no significant differences, with higher values observed in the groups where nanoparticles were administered compared to the control. In conclusion, although statistical significance is not demonstrated, the data suggest that exposure to SiO₂ nanoparticles could influence the locomotor behavior of zebrafish, with a possible dose-dependent effect.

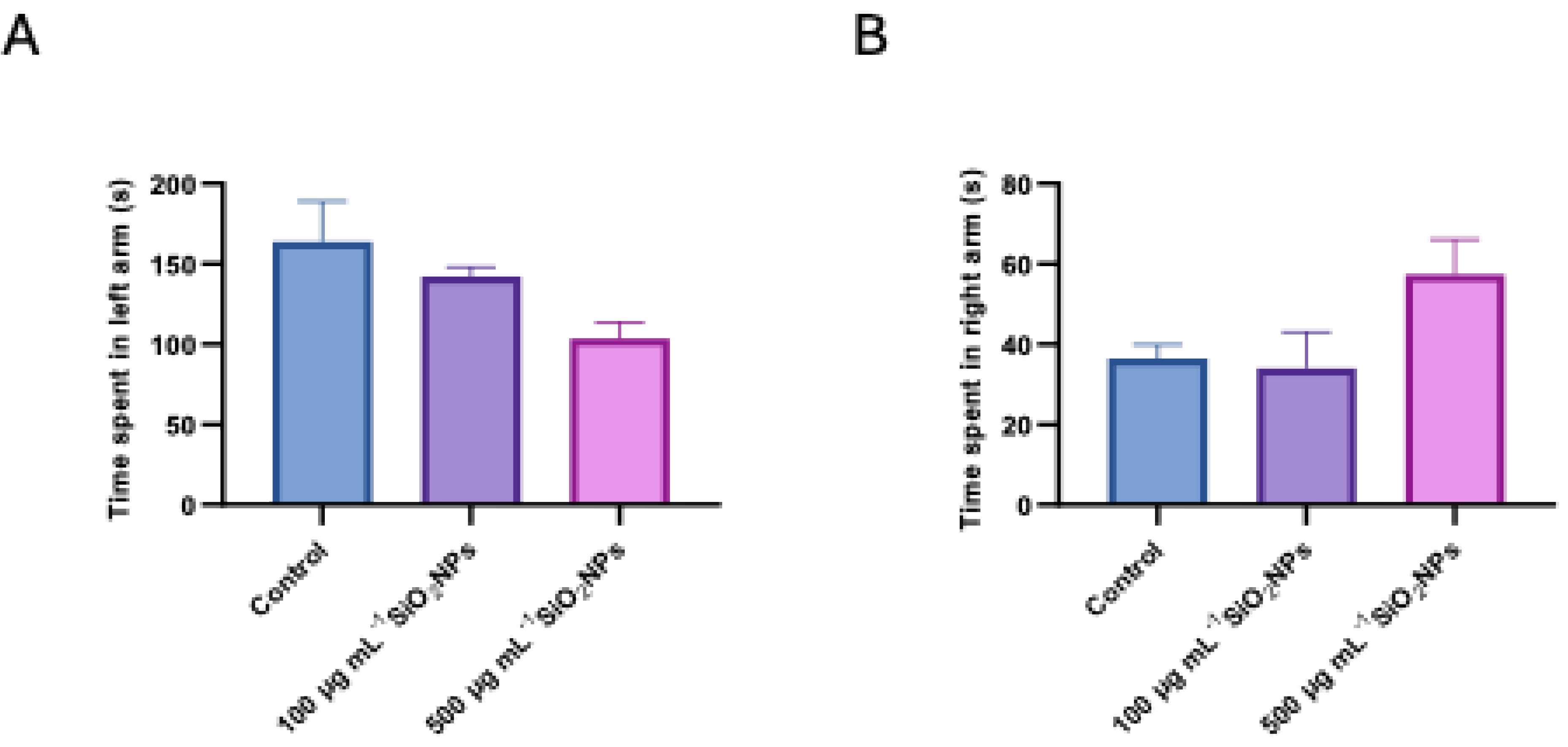

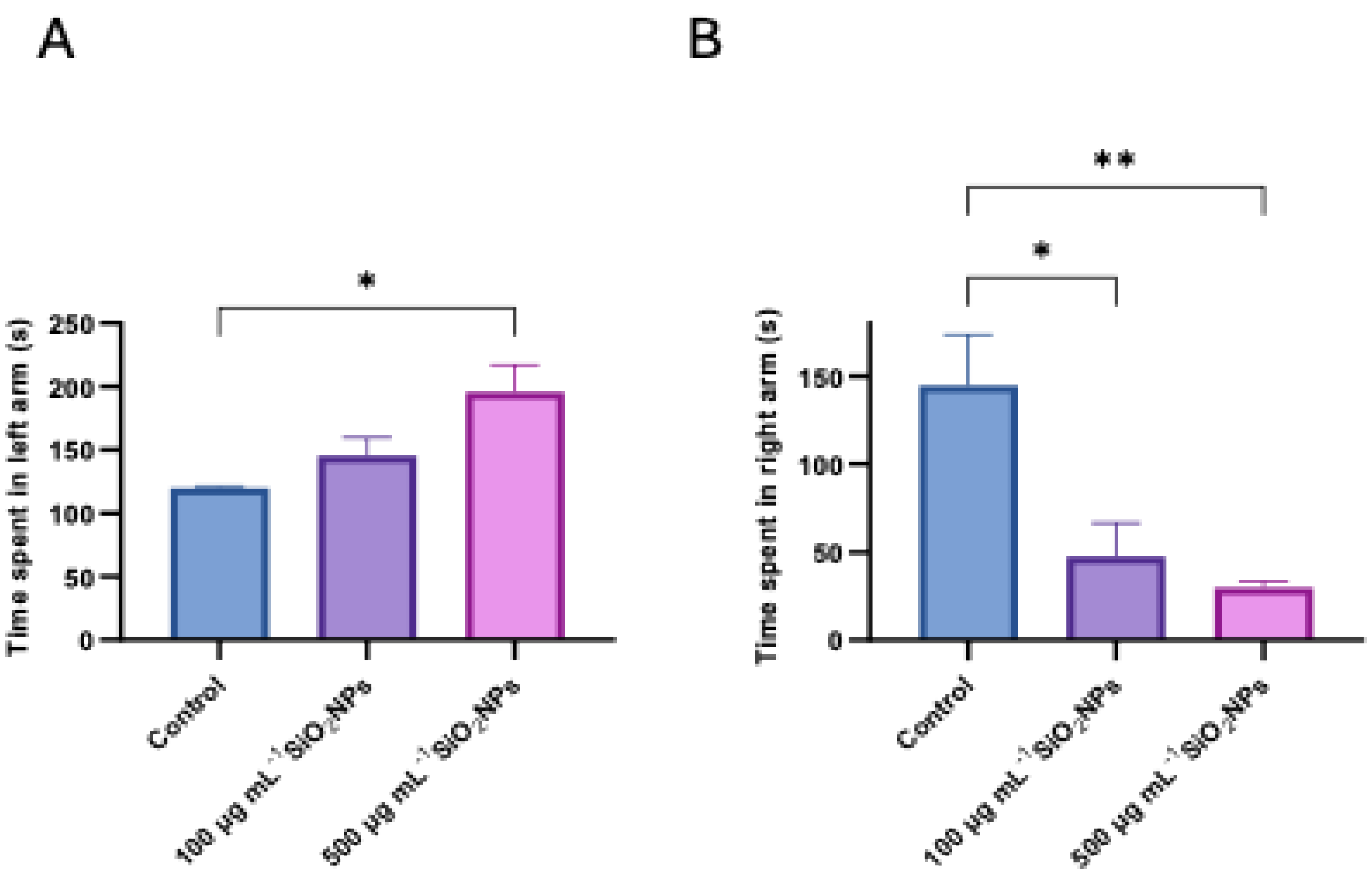

In addition to velocity and total distance moved, two other specific parameters were analyzed, namely the time spent in the stimulus arm (left arm) and the time spent in the non-stimulus arm (right arm) (

Figure 3).

The results indicate that exposure to nanoparticles influences the social behavior of zebrafish, this effect being manifested by a decrease in the time spent in the stimulus arm (left arm), correlated with the increase in the concentration of nanoparticles, as well as a concomitant increase in the time spent in the non-stimulus arm (right arm).

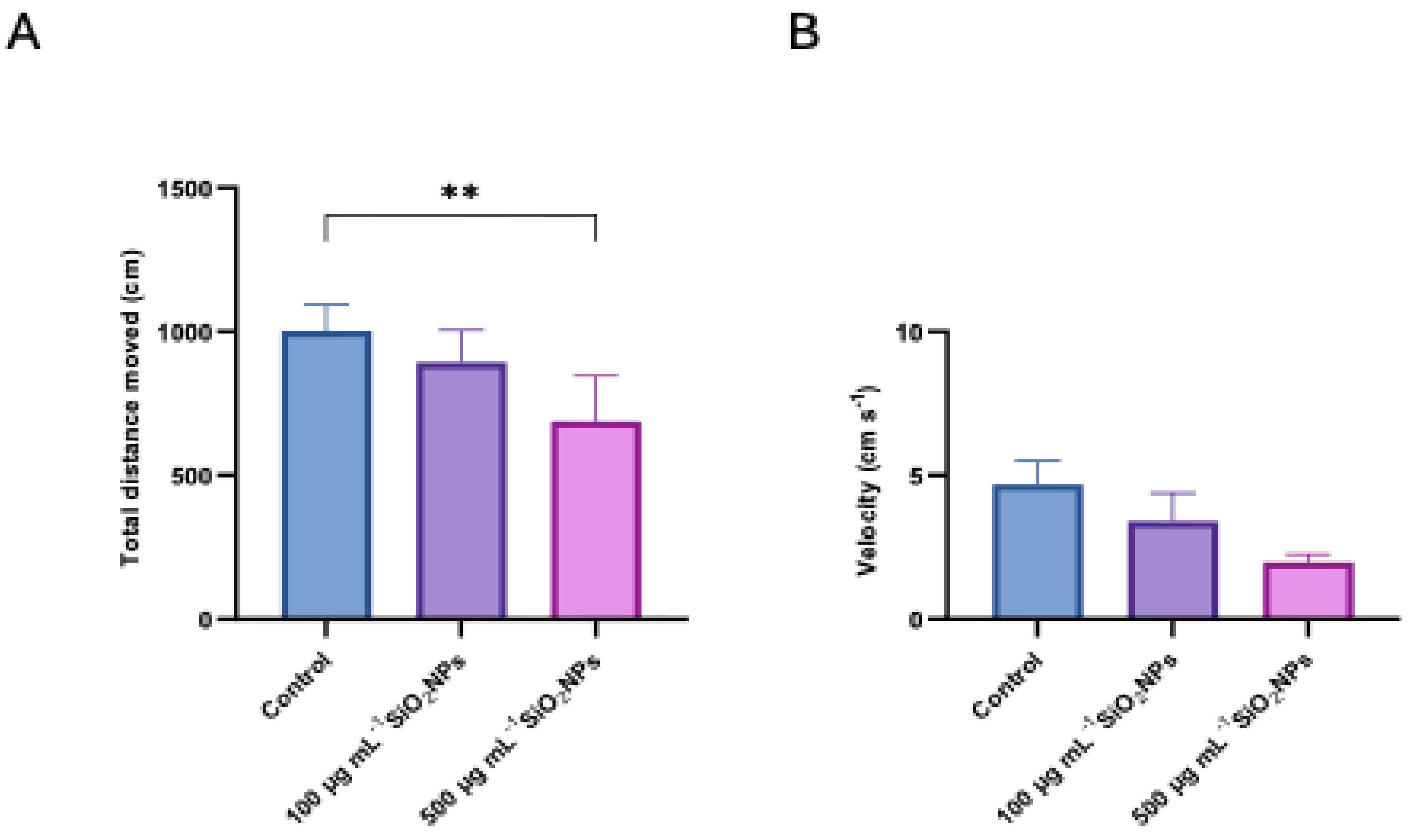

3.2. Color Preference Test

To assess color preference, the specific test was used, in which several relevant behavioral parameters were analyzed, including swimming speed and total distance moved (

Figure 4).

Regarding the total distance moved, a progressive decrease of this parameter was observed with increasing silica nanoparticle concentration, the difference becoming statistically significant between the control group and the one exposed to the highest concentration (500 μg mL-1, p = 0.004).

In contrast, velocity showed a tendency to increase with increasing nanoparticle concentration, which could suggest a change in the locomotor pattern, possibly related to a stress or agitation response induced by exposure to nanoparticles.

The time spent in the left arm (red) and the time spent in the right arm (green) in the color preference test were also analyzed (

Figure 5). The results indicated a significant increase in the time spent in the left arm with increasing nanoparticle concentration, the difference becoming significant between the control group and the one treated with 500 μg mL

-1 of nanoparticles (p = 0.027). In parallel, the time spent in the right arm (green) recorded a significant decrease in both treated groups, compared to the control: 100 μg mL

-1 (p = 0.019) and 500 μg mL

-1 (p = 0.008). These changes suggest an influence of nanoparticles on exploratory behavior and chromatic preference.

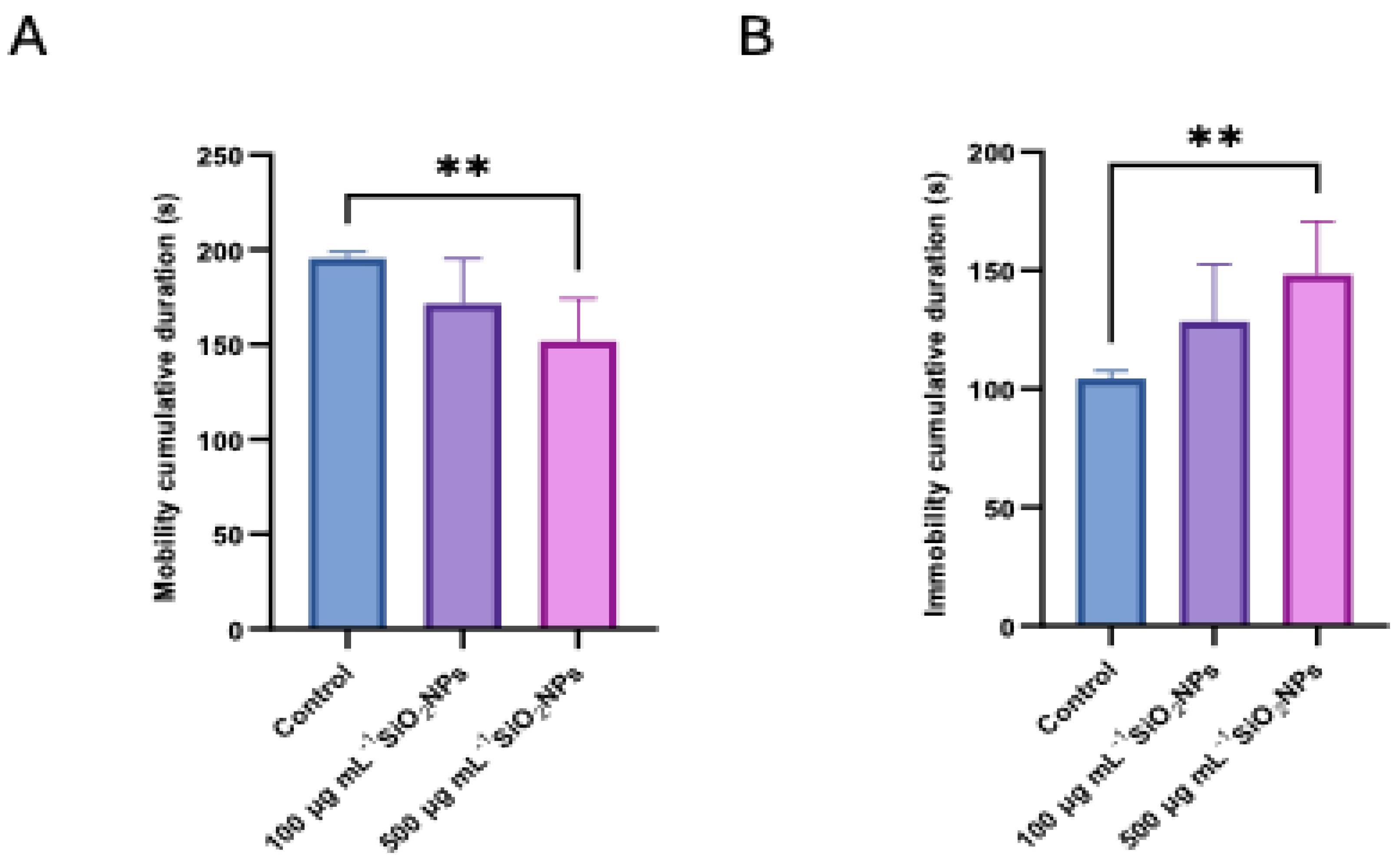

The cumulative duration of mobility and the duration of immobility were two other behavioral parameters analyzed in the experiment (

Figure 6). The results revealed a progressive decrease in mobility and an increase in immobility depending on the concentration of silica nanoparticles administered. Thus, for the duration of mobility there was a significant decrease in the group treated with 500 μg mL

-1 nanoparticles compared to the control group (p = 0.0088). Correspondingly, the duration of immobility showed a significant increase at the same concentration, compared to the control group (p = 0.0088), suggesting a possible inhibitory effect on spontaneous motor activity, associated with exposure to high doses of nanoparticles.

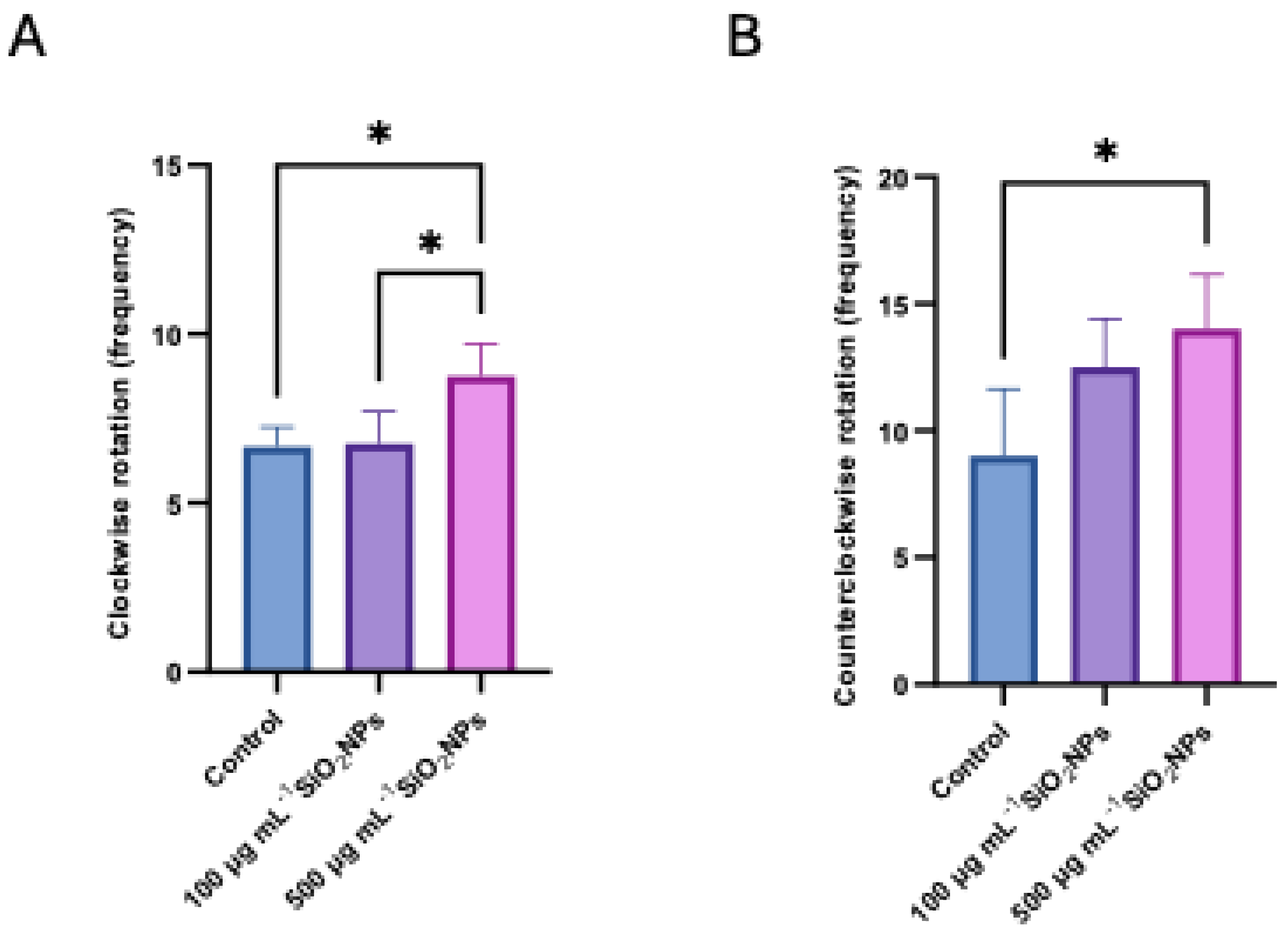

In the color preference test, a significant increase in the frequency of clockwise rotations was observed in individuals exposed to the higher concentration of nanoparticles (

Figure 7), compared to both the control group (p = 0.034) and the group exposed to the lower concentration (p = 0.0294). Also, in the case of counterclockwise rotations, a significant increase was recorded in the group treated with the higher dose compared to the control group (p = 0.0427), which may indicate a disruption of exploratory behavior or sensory response, possibly associated with nanoparticle-induced neurotoxicity.

3.3. Oxidative Stress

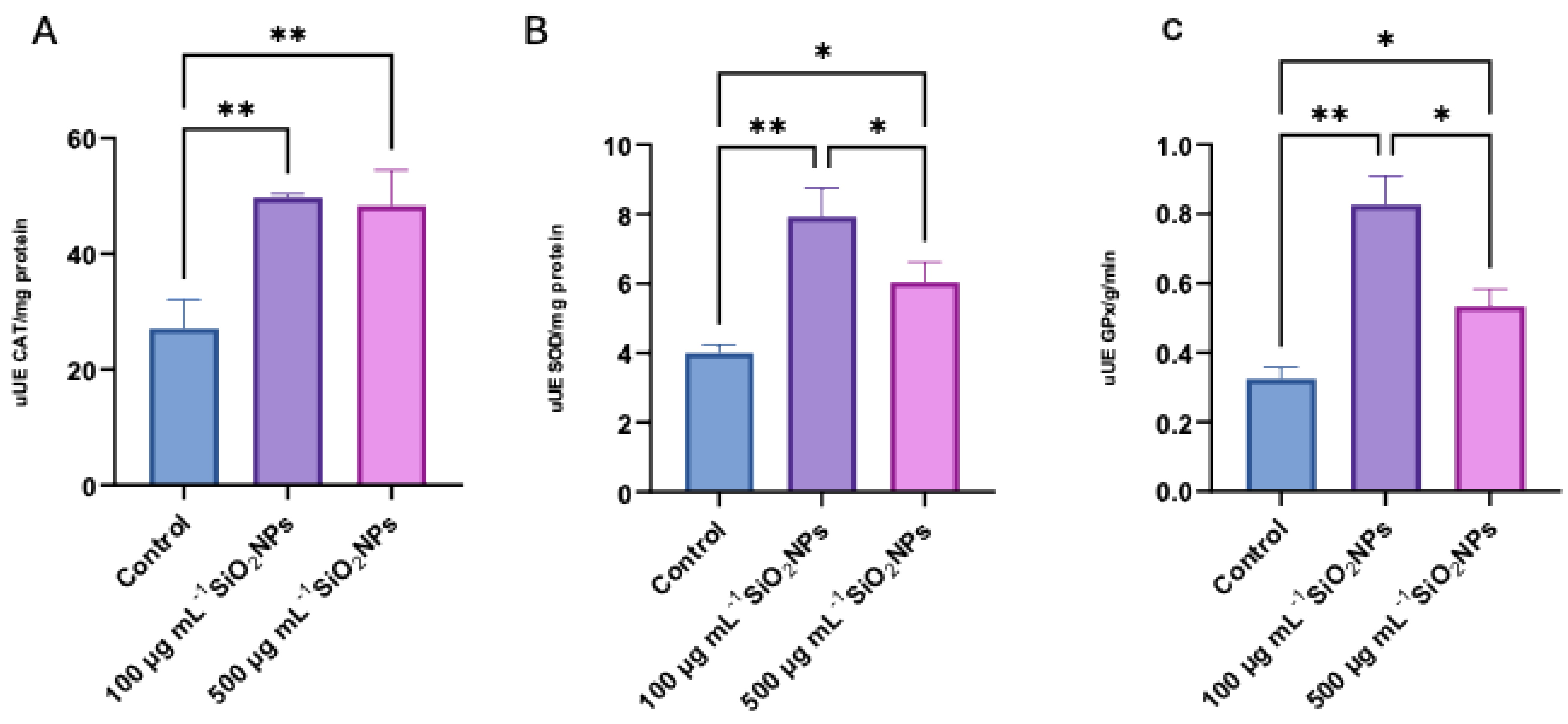

Regarding biomarkers of OS, three essential antioxidant enzymes in cellular defense against reactive oxygen species (ROS) were analyzed: SOD, GPx, and CAT (

Figure 8). These enzymes play a central role in maintaining redox balance, contributing to the neutralization of free radicals and the prevention of lipid peroxidation. Their activity was evaluated to highlight the changes induced by the administration of nanoparticles and to characterize the adaptive antioxidant response of the organism depending on the applied concentration.

Regarding catalase activity, a statistically significant increase was observed between the control group and the group treated with a concentration of 100 μg mL-1 of nanoparticles (p = 0.0098), but also between the control group and the one treated with a concentration of 500 μg mL-1 of nanoparticles in the antioxidant action, in active substances. presence of exposure.

Superoxide dismutase activity also recorded increased values compared to the control group in both treated groups, with a more pronounced increase in the case of the lower concentration (100 μg mL-1) compared to the control (p = 0.0027). At the same time, a significant decrease in SOD activity was observed in the group treated with 500 μg mL-1 compared to the one treated with 100 μg mL-1 (p = 0.0494), which may indicate a possible effect of inhibition or depletion of the antioxidant response at higher doses.

Regarding the identification of glutathione peroxidase, the levels of this enzyme were significantly higher in the 100 μg mL-1 group compared to the control group (p = 0.0011), but also compared to the group treated with 500 μg mL-1 (p = 0.0122). In contrast, in the case of the group exposed to the concentration higher than 500 μg mL-1, a significant decrease in GPx activity was recorded compared to the control group (p = 0.0277), suggesting a possibility of redox imbalance or impairment of antioxidant capacity at increased doses of nanoparticles.

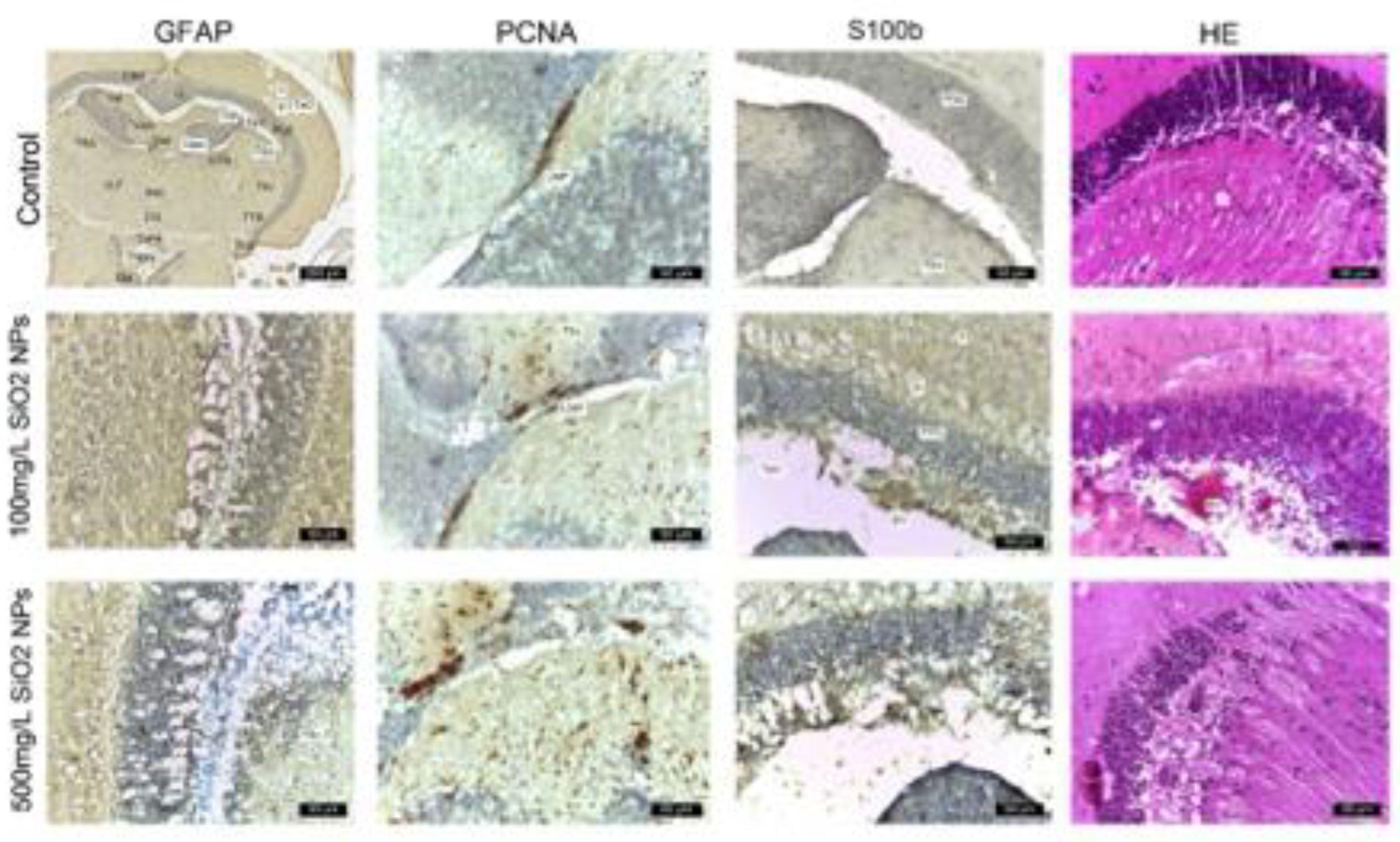

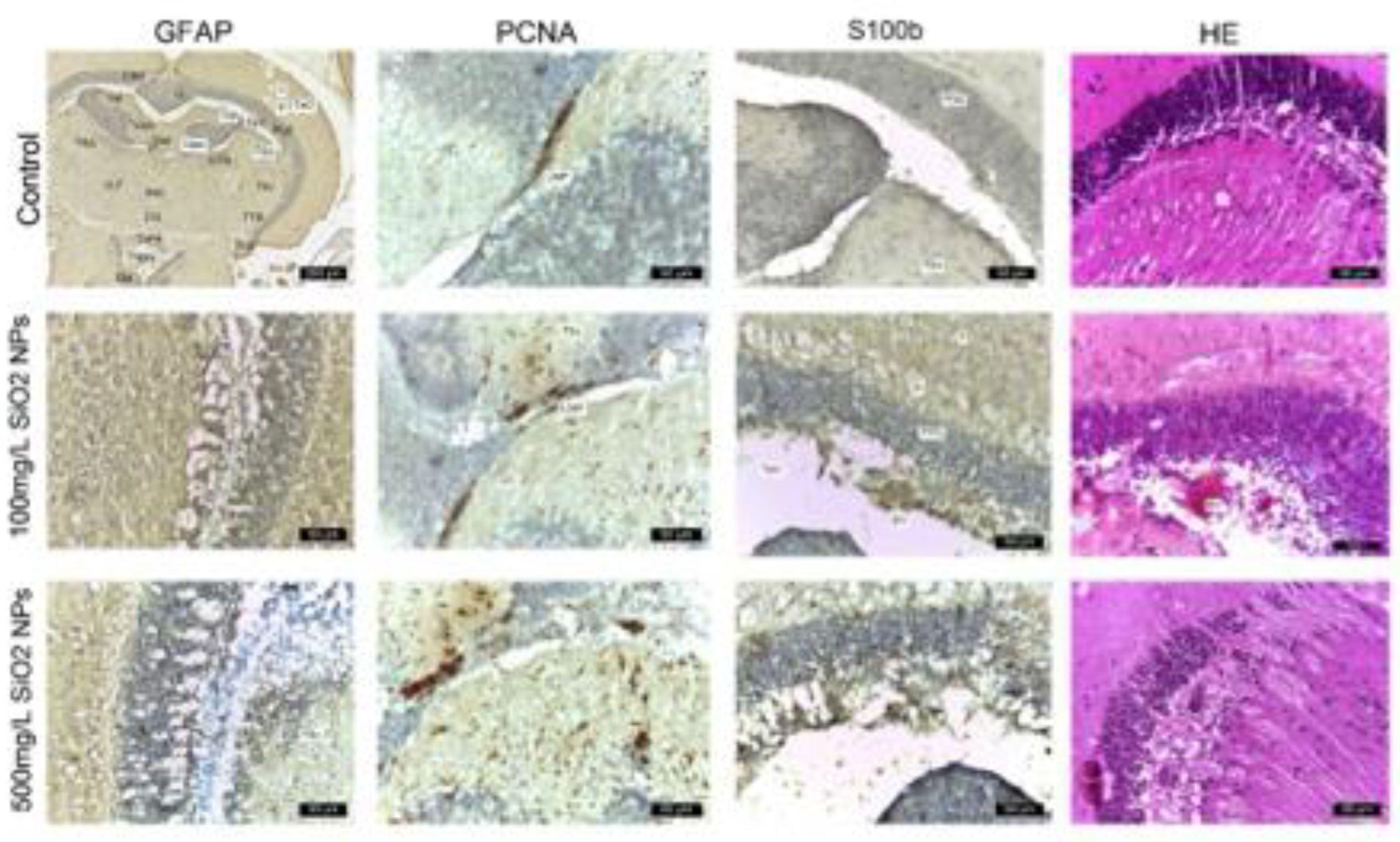

3.4. Histological and Immunohistological Analysis

In this study, we investigated the effects of SiO₂NPs on adult zebrafish brains. Histological analysis was performed on brain sections of the control and experimental groups, which were exposed to various treatments. ImmunohIHC was employed to assess the expression of glial and proliferative markers, including GFAP, S100B, and PCNA (

Figure 9). Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining was also used to assess general tissue morphology. The following sections present the histological findings in detail.

In the control group, immunolabeling with anti-GFAP and anti-S100 antibodies revealed a low number of glial cells, located both in the white matter of the caudal tectal commissure (Ctec) and in the grey matter of the optic tectum (TeO), torus semicircularis (TSc), and torus lateralis (TLa). Immunostaining with anti-PCNA antibody identified a small number of positive cells, predominantly in the ventromedial region known as the posterior mesencephalic lamina (LMP). Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining revealed a compact layer of granular neurons with normal morphology within the periventricular grey zone (PGZ).

Exposure to 100 μg mL-1 SiO₂NPs resulted in evident changes, characterized by glial cell proliferation, with cells positive for GFAP and S100 predominantly located in the PGZ and TeV, displaying elongated cytoplasmic processes. Small areas of neuronal necrosis were also observed within the same layer. PCNA immunostaining revealed cells undergoing DNA synthesis, distributed along the periphery of the diencephalic ventricle (Div) and the ventromedial optic tract. Small foci of neuropil degeneration were observed in the white matter adjacent to the PGZ. HE staining additionally revealed vascular ectasia in the TeV.

In the group exposed to 500 μg mL-1 SiO₂NPs, optic tectum lesions were more pronounced compared to the group exposed to 100 μg mL-1. The alterations included extensive glial cell proliferation, with GFAP- and S100-positive cells found in the PGZ and TeV, the presence of multiple foci of neuronal necrosis, and a reduction in the thickness of the granular layer. The inner surface of the tectal ventricle was lined with S100-positive cells, displaying morphological features of ependymal and subependymal cells. PCNA expression was increased in the torus semicircularis (TSc), the periventricular area of the diencephalon (Div), and the posterior mesencephalic lamina (LMP). Frequent small areas of neuropil degeneration were identified within the white matter of the third layer of the optic tectum. HE staining also revealed vascular ectasia and congestion, along with a reduced thickness of the PGZ granular layer.

Although areas of necrosis persisted in the PGZ and in the neuropil of the white matter, the increased number of PCNA-positive cells indicated an ongoing regenerative process. The appearance of the granular layer varied from compact regions to areas containing small foci of necrosis.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the behavioral, biochemical, and histological effects of SiO₂ nanoparticles on adult zebrafish, focusing on social interaction, color preference, locomotor activity, OS biomarkers, and histopathology. The results indicate a complex, concentration-dependent impact of nanoparticle exposure on both behavioral phenotypes and antioxidant defense mechanisms.

In the social behavior test, although differences in total distance moved and swimming speed were not statistically significant, the increasing trend observed in the treated groups, especially at the 500 μg mL⁻¹ concentration, suggests a potential stimulatory effect on locomotion. This could reflect increased exploratory drive, potentially mediated by neurochemical changes such as upregulation of dopaminergic or serotonergic activity, as has been previously reported in zebrafish exposed to environmental stressors or neuroactive substances [

24]. However, such increased activity could also be indicative of heightened arousal or stress, rather than positive stimulation.

The reduction in time spent in the stimulus arm, concomitant with increased presence in the non-stimulus arm, implies a decline in social preference with rising nanoparticle concentration [

25]. This aligns with previous findings that report nanoparticle exposure may interfere with social recognition and affiliative behavior, possibly through disruption of sensory input or central nervous system processing [

26].

In the color preference test, a significant decrease in total distance moved was observed at the highest concentration, coupled with an increase in swimming velocity [

27]. This divergence suggests a change in locomotor strategy, shorter distances covered at higher speeds, which may reflect anxious or erratic movement, commonly associated with environmental stress [

28]. Moreover, the increased preference for the left (red) arm and reduced time in the right (green) arm may indicate that nanoparticle exposure affects not only exploration but also chromatic perception or preference. This is relevant, as visual system alterations have been linked to metal and nanoparticle exposure in aquatic species [

29].

Further behavioral alterations, such as increased immobility and decreased mobility at high doses, reinforce the hypothesis of a suppressive effect on spontaneous motor activity [

30]. These effects may represent fatigue, neurotoxicity, or generalized stress response. Additionally, the significant increase in both clockwise and counterclockwise rotations at higher concentrations could be indicative of disorientation, sensory-motor dysfunction, or stereotypic behavior, phenomena that have also been documented in other neurobehavioral toxicity studies.

From a biochemical perspective, the activities of CAT, SOD, and GPx enzymes reveal a dose-dependent modulation of OS response [

31]. The significant upregulation of all three enzymes at 100 μg mL⁻¹ suggests an adaptive antioxidant response to moderate oxidative challenge. This upregulation is consistent with literature describing increased enzymatic activity as a compensatory mechanism to counteract elevated ROS production in early stages of nanoparticle exposure [

32].

However, at the higher dose (500 μg mL⁻¹), a biphasic response is evident: while CAT remains elevated, SOD and GPx activities decrease significantly. This may indicate a threshold of oxidative defense capacity, beyond which the antioxidant system becomes overwhelmed or inhibited [

33]. The decline in GPx and SOD could signal either enzyme depletion or direct interference by nanoparticles with their synthesis or activity. Similar inhibitory effects at high doses have been reported for other nanomaterials and are associated with oxidative damage, apoptosis, and altered mitochondrial function [

34].

Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that SiO₂ nanoparticles exert dose-dependent effects on both neurobehavioral functions and oxidative homeostasis in zebrafish. Moderate exposure (100 μg mL⁻¹) appears to trigger adaptive mechanisms, both behaviorally and biochemically, while higher exposure (500 μg mL⁻¹) leads to behavioral disturbances and antioxidant system suppression.

The observed behavioral alterations, especially in social preference, mobility, and rotational behavior, are likely interconnected with OS, suggesting that neurotoxicity may be a key mode of action for SiO₂ nanoparticles [

35]. Given the wide usage of silica-based nanomaterials in industrial and biomedical applications, these findings underline the importance of further investigating their potential sublethal effects in aquatic organisms and developing clear concentration thresholds for environmental safety.

5. Conclusions

The present study provides evidence that exposure to silica nanoparticles induces dose-dependent effects on both behavioral and oxidative stress responses in adult zebrafish. Behavioral assessments revealed subtle but consistent alterations, including increased locomotor activity, reduced social preference, disrupted color preference, and heightened rotational behavior, especially at the highest tested concentration (500 μg mL⁻¹). These changes may be indicative of neurobehavioral disturbances potentially linked to nanoparticle-induced stress or neurotoxicity.

Biochemically, moderate exposure (100 μg mL⁻¹) triggered an upregulation of key antioxidant enzymes (CAT, SOD, GPx), suggesting the activation of compensatory defense mechanisms against oxidative stress. However, at higher exposure levels, a significant decline in SOD and GPx activities was observed, alongside sustained catalase activity, indicating a potential impairment or exhaustion of the antioxidant system.

Overall, these findings highlight the dual nature of the biological response to SiO₂ nanoparticles: adaptive at lower concentrations but potentially negative at higher doses. The observed behavioral alterations, in conjunction with oxidative stress modulation, underline the need for further investigation into the mechanisms underlying nanoparticle toxicity and the establishment of environmentally relevant safety thresholds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.R., I.L.G., E.T.-C., and B.G.; methodology, A.C., and M.N.N.; software, V.R.; validation, A.C., M.N.N., and B.G.; formal analysis, C.S.; data curation, R.V., M.N.N. and B.G.; writing - original draft preparation, R.V., and E.T.-C.; writing - review and editing, V.R., I.L.G., M.N.N., and B.G.; visualization, V.R., I.L.G., B.G., C.S., and D.U.; supervision, A.C., M.N.N., and D.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experiments involving the use of zebrafish were carried out in accordance with the EU Commission Recommendation (2007), Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on guidelines for housing, care and the protection of animals used for experimental purposes. The experiments were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as the legislation of Romania and the European Union regarding the use of animals in biomedical research. Also, all experiments and procedures were conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Biology ("Alexandru Ioan Cuza" University of Iasi) Approval Code: 100/10.12.2024. All procedures were performed by limiting the number of individuals, according to the ARRIVE guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sim, S.; Wong, N.K. Nanotechnology and its use in imaging and drug delivery (Review). Biomed Rep. 2021, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altammar, K.A. A review on nanoparticles: characteristics, synthesis, applications, and challenges. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1155622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, S.S.; Yusuf, A.A.; Akiyode, O.O.; Hallie, E.F.; Odoma, S.; Yambasu, R.A.; et al. A comprehensive review on exposure to toxins and health risks from plastic waste: Challenges, mitigation measures, and policy interventions. Waste Management Bulletin 2025, 3, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Manuel, I.; Pérez-Alvarez, M.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; Cabello-Alvarado, C.J.; Tellez-Barrios, G.; Ávila-Orta, C.A.; et al. Sonochemical Functionalization of SiO2 Nanoparticles with Citric Acid and Monoethanolamine and Its Remarkable Effect on Antibacterial Activity. Materials 2025, 18, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.; Almotairy, A.R.Z.; Henidi, H.; Alshehri, O.Y.; Aldughaim, M.S. Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery Systems: A Review of the Implication of Nanoparticles’ Physicochemical Properties on Responses in Biological Systems. Polymers 2023, 15, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, T.R.; Raj, A.; Tseng, T.H.; Xiao, H.; Nguyen, R.; Mohammed, F.S.; et al. Biocompatibility of nanomaterials and their immunological properties. Biomed Mater. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, A.M.B.; Piochi, L.F.; Gaspar, A.T.; Preto, A.J.; Rosário-Ferreira, N.; Moreira, I.S. Advancing Drug Safety in Drug Development: Bridging Computational Predictions for Enhanced Toxicity Prediction. Chem Res Toxicol. 2024, 37, 827–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, Y.; Hu, N.; Long, D.; Cao, Y. The uses of zebrafish (Danio rerio) as an in vivo model for toxicological studies: A review based on bibliometrics. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024, 272, 116023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choe, C.P.; Choi, S.Y.; Kee, Y.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, Y.; et al. Transgenic fluorescent zebrafish lines that have revolutionized biomedical research. Lab Anim Res. 2021, 37, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerfield, M. The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio), 5th Edition. Zebrafish International Resource Center, University of Oregon Press, Eugene, USA, 2007.

- Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Official Journal of the European Union, L276, 33-79. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd, 2010, 152.

- Kilkenny, C.; Browne, W.J.; Cuthill, I.C.; Emerson, M.; Altman, D.G. Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J.K. AVMA Guidelines for the euthanasia of animals. Animal Welfare. 2013, 22, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, B.; Li, X.-L. , Li, Y.-X.; Sun, M.-Z.; Chen, D.-Y.; et al. SiO2 nanoparticles change colour preference and cause Parkinson’s-like behaviour in zebrafish. Sci Rep. 2014, 4, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashidian, G.; Mohammadi-Aloucheh, R.; Hosseinzadeh-Otaghvari, F.; Chupani, L.; Stejskal, V.; Samadikhah, H.; et al. Long-term exposure to small-sized silica nanoparticles (SiO2-NPs) induces oxidative stress and impairs reproductive performance in adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part - C: Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2023, 273, 109715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bault, Z.A.; Peterson, S.M.; Freeman, J.L. Directional and color preference in adult zebrafish: Implications in behavioral and learning assays in neurotoxicology studies. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2015, 35, 1502–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, T.; Suriyampola, P.S.; Flores, J.; López, M.; Hickey, C.; Bhat, A.; et al. Color preferences affect learning in zebrafish, Danio rerio. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 14531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, S.; Félix, L.; Costas, B.; Valentim, A.M. Housing Conditions Affect Adult Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Behavior but Not Their Physiological Status. Animals. 2023, 13, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C.C.; Hawkins, R.E.; Brian, M.; Carrell, RW. The estimation of red cell superoxide dismutase activity. J Lab Clin Med. 1975, 85, 337–341. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.K. Colorimetric assay of catalase. Anal Biochem. 1972, 47, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuzawa, K.; Tokumura, A. Glutathione peroxidase activity in tissues of vitamin e-deficient mice. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol 1976, 22, 405–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979, 95, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anichtchik, O.V.; Kaslin, J.; Peitsaro, N.; Scheinin, M.; Panula, P. Neurochemical and behavioural changes in zebrafish Danio rerio after systemic administration of 6-hydroxydopamine and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. J Neurochem. 2004, 88, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbgoo, F.; Nejabat, M.; Abnous, K.; et al. Gold nanoparticle should understand protein corona for being a clinical nanomaterial. J Control Release. 2018, 272, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia, S.; Islam, Aqib A, Muneer, A. et al. Insights into nanoparticles-induced neurotoxicity and cope up strategies. Front Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1127460. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Z.; Zhuo, D.; Huang, Z.; et al. Deficiency of Acetyltransferase nat10 in Zebrafish Causes Developmental Defects in the Visual Function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024, 65, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, D.; Domingues, I.; Faria, M.; Oliveira, M. Effects of fluoxetine on fish: What do we know and where should we focus our efforts in the future? Science of The Total Environment 2023, 857, 159486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar-Lopez, F.J. Recent Progress in Micro- and Nanotechnology-Enabled Sensors for Biomedical and Environmental Challenges. Sensors. 2023, 23, 5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak, M.; Nicola, S.M. The Arousal-motor Hypothesis of Dopamine Function: Evidence that Dopamine Facilitates Reward Seeking in Part by Maintaining Arousal. Neuroscience. 2022, 499, 64–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang Daud, D.M.; Ahmedy, F.; Baharuddin, D.M.P.; Zakaria, Z.A. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Enzymes Activity after Cycling at Different Intensity and Duration. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 9161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatansever, F.; de Melo, W.C.; Avci, P.; et al. Antimicrobial strategies centered around reactive oxygen species-bactericidal antibiotics, photodynamic therapy, and beyond. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013, 37, 955–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birben, E.; Sahiner, U.M.; Sackesen, C.; Erzurum, S.; Kalayci, O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ J. 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several lines of antioxidant defense against oxidative stress: antioxidant enzymes, nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, J.; Lin, X.; et al. Evaluation of neurotoxicity and the role of oxidative stress of cobalt nanoparticles, titanium dioxide nanoparticles, and multiwall carbon nanotubes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxicol Sci. 2023, 196, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Experimental design illustrating zebrafish exposure to SiO₂NPs, followed by behavioral, immunological, and oxidative stress assessments.

Figure 1.

Experimental design illustrating zebrafish exposure to SiO₂NPs, followed by behavioral, immunological, and oxidative stress assessments.

Figure 2.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on social behavior in zebrafish (A) Total distance moved (cm), (B) Velocity (cm s-1).

Figure 2.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on social behavior in zebrafish (A) Total distance moved (cm), (B) Velocity (cm s-1).

Figure 3.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on social behavior in zebrafish (A) time spent in left arm (s), (B) Time spent in right arm (s).

Figure 3.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on social behavior in zebrafish (A) time spent in left arm (s), (B) Time spent in right arm (s).

Figure 4.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on social behavior in zebrafish (A) Total distance moved (cm), (B) Velocity (cm s-1). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: ** p < 0.01.

Figure 4.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on social behavior in zebrafish (A) Total distance moved (cm), (B) Velocity (cm s-1). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: ** p < 0.01.

Figure 5.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on behavior in zebrafish (A) Total spent in left arm (s), (B) Total spent in right arm (s). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Figure 5.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on behavior in zebrafish (A) Total spent in left arm (s), (B) Total spent in right arm (s). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Figure 6.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on social behavior in zebrafish (A) Mobility cumulative duration (s), (B) Immobility cumulative duration (s). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: ** p < 0.01.

Figure 6.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on social behavior in zebrafish (A) Mobility cumulative duration (s), (B) Immobility cumulative duration (s). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: ** p < 0.01.

Figure 7.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on social behavior in zebrafish (A) Clockwise rotation (frequency), (B) Counterclockwise rotation (frequency). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: * p < 0.05.

Figure 7.

Effects of exposure to different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on social behavior in zebrafish (A) Clockwise rotation (frequency), (B) Counterclockwise rotation (frequency). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: * p < 0.05.

Figure 8.

Effects of different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on oxidative stress biomarkers in zebrafish: (A) Catalase (CAT), (B) Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), (C) Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Figure 8.

Effects of different concentrations of silica nanoparticles on oxidative stress biomarkers in zebrafish: (A) Catalase (CAT), (B) Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), (C) Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Figure 9.

Histology of adult zebrafish brain of control group. The untreated adult zebrafish brain shows intact structural morphology and cellular morphology. The optic tectum displays its 4 layers: (I) superficial gray-white zone, (II) central zone, (III) deep white zone, and (IV) periventricular grey zone (PGZ). The lateral torus (TLa) is homogenous, diffusively arranged, without apparent divisions or inflammation. The brain section has undamaged cellular morphology which represents non-existent inflammation. Other visible regions include: ansulate commissure (Cans), mammillary body (CM), diffuse nucleus of the inferior lobe (DIL), habenulo-interpeduncular tract (FR), lateral longitudinal fascicle (LLF), lateral recess of diencephalic ventricle (LR), nucleus of the lateral lemniscus (NLL), oculomotor nucleus (NIII), periventricular gray zone (PGZ), optic tectum (TeO), longitudinal torus (TL), lateral torus (TLa) and lamina connects the tectum to the cerebellum, central nucleus of torus semicircularis (TSc), tectobulbular tract (TTB), lateral division of valvulacerebelli (Val), medial division of valvulacerebelli (Vam), vascular lacuna of area postrema (Vas), caudal tectal commissure (Ctec), valvula cerebelli (VC), and lamina of the posterior mesencephalon (LMP). Blood vessels (BV) are also visible. The columns show IHC staining for anti-GFAP, anti-PCNA, and anti-S100. The last column shows hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. Scale bar is 50 μm.

Figure 9.

Histology of adult zebrafish brain of control group. The untreated adult zebrafish brain shows intact structural morphology and cellular morphology. The optic tectum displays its 4 layers: (I) superficial gray-white zone, (II) central zone, (III) deep white zone, and (IV) periventricular grey zone (PGZ). The lateral torus (TLa) is homogenous, diffusively arranged, without apparent divisions or inflammation. The brain section has undamaged cellular morphology which represents non-existent inflammation. Other visible regions include: ansulate commissure (Cans), mammillary body (CM), diffuse nucleus of the inferior lobe (DIL), habenulo-interpeduncular tract (FR), lateral longitudinal fascicle (LLF), lateral recess of diencephalic ventricle (LR), nucleus of the lateral lemniscus (NLL), oculomotor nucleus (NIII), periventricular gray zone (PGZ), optic tectum (TeO), longitudinal torus (TL), lateral torus (TLa) and lamina connects the tectum to the cerebellum, central nucleus of torus semicircularis (TSc), tectobulbular tract (TTB), lateral division of valvulacerebelli (Val), medial division of valvulacerebelli (Vam), vascular lacuna of area postrema (Vas), caudal tectal commissure (Ctec), valvula cerebelli (VC), and lamina of the posterior mesencephalon (LMP). Blood vessels (BV) are also visible. The columns show IHC staining for anti-GFAP, anti-PCNA, and anti-S100. The last column shows hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. Scale bar is 50 μm.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).