Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Mechanisms of Cellular Senescence

1.2. The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP)

1.3. Senescence in Metabolic Tissues

2. Molecular Composition and Functional Impact of the SASP

- Chemokines: Molecules like IL-8 (CXCL8) and CCL2 (MCP-1) recruit neutrophils, monocytes, and other immune cells into affected tissues [10].

- Growth Factors: Senescent cells secrete TGF-β1 and VEGF, among others, to activate fibroblasts and immune cells – promoting fibrosis, angiogenesis, and even a tumor-permissive microenvironment. These factors also reinforce senescence in an autocrine loop [11].

- Matrix-Remodeling Proteases: Enzymes such as MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-9 degrade extracellular matrix components, facilitating tissue remodeling and immune cell infiltration [10].

- Extracellular Vesicles & Non-Protein Mediators: In addition to soluble proteins, senescent cells release microRNAs and lipid-loaded vesicles that transmit “senescence signals” to neighboring or distant cells [12]. Recent studies also identify lipid mediators—such as oxylipins derived from polyunsaturated fatty acids—as part of the SASP, linking senescence directly to metabolic regulation [13].

- Lipid Mediators/Lipidomics: Senescent cells with elevated oxylipins, converted from free cytosolic polyunsaturated fatty acids [60]. Furthermore, ceramides are a critical component of the lipid-based SASP. Elevated ceramide concentration increases senescence markers while reducing markers of proliferation, displaying a shift towards senescent states [13].

2.1. Physiological SASP

2.2. Pathological SASP

- Sustained pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) that impair stem cells and redirect immune function.

- Continuous matrix remodeling (MMPs, uPA) leading to tissue architecture disruption and fibrosis.

- Paracrine senescence, where SASP factors induce neighboring healthy cells to adopt a senescent phenotype, creating a feed-forward amplification loop [15]. Chronic SASP underlies age-related organ dysfunction, particularly in metabolic tissues, by promoting fibrosis, insulin resistance, and global tissue decline.

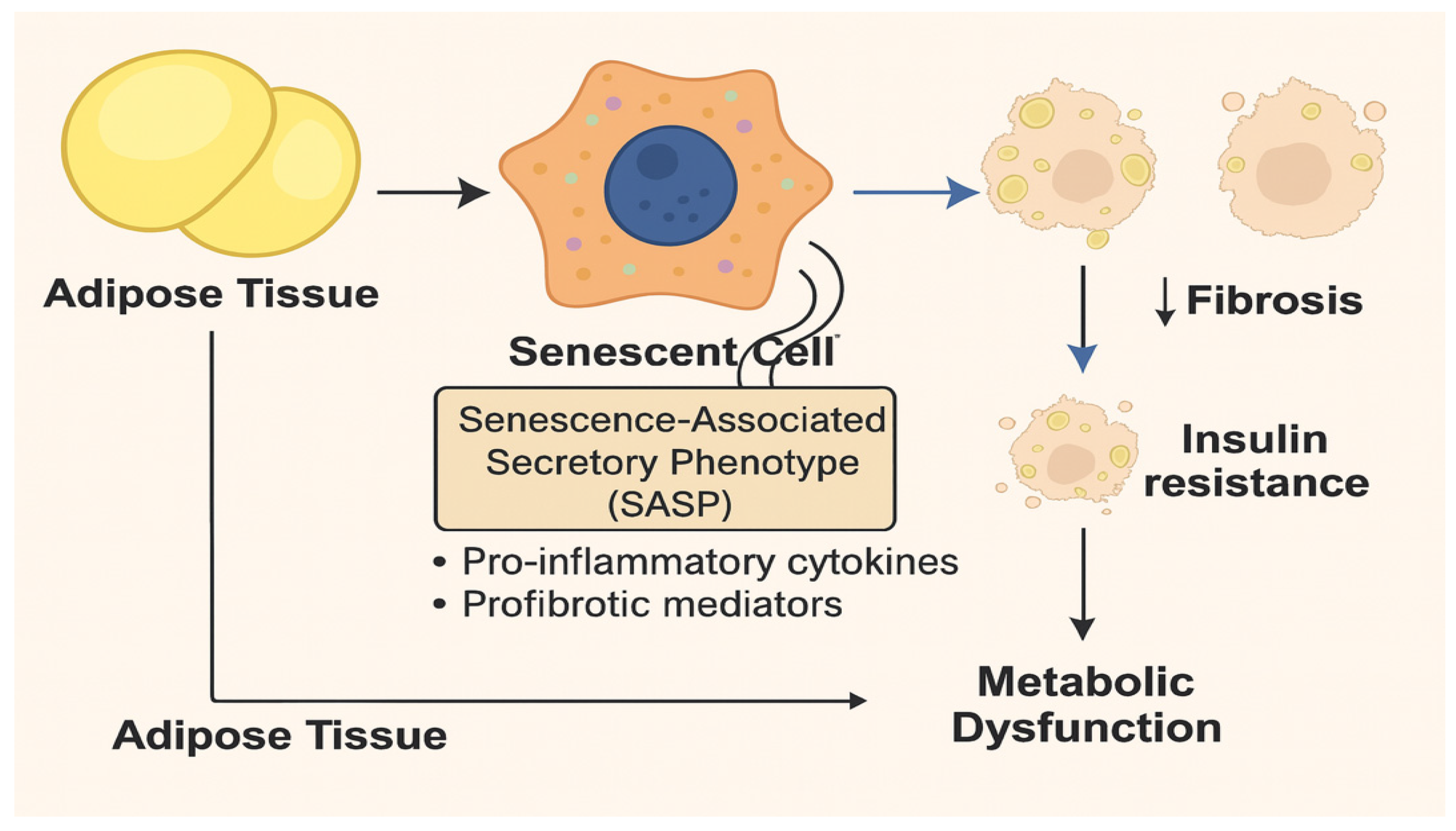

3. Senescence and Metabolic Dysfunction in Adipose Tissue

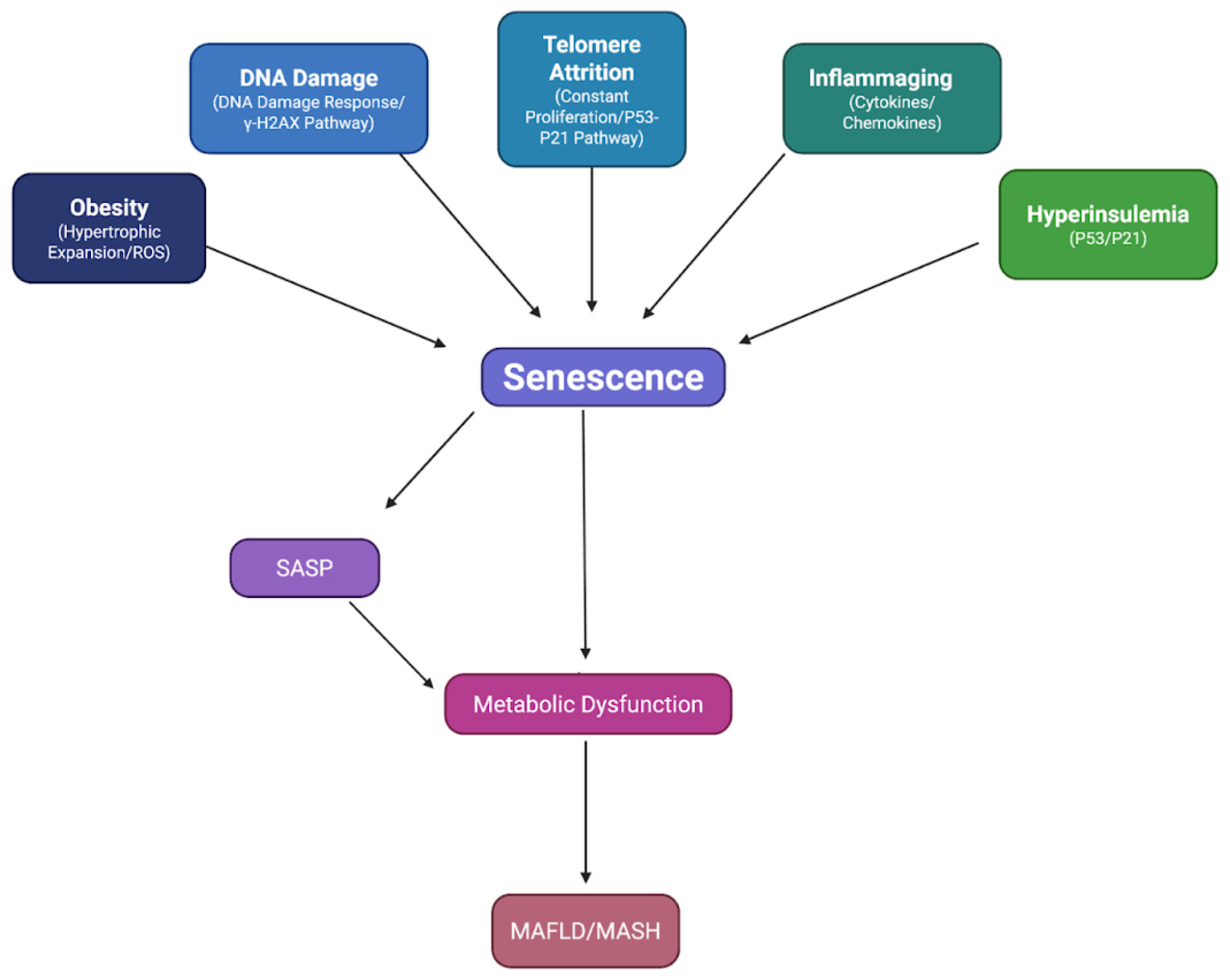

3.1. Mechanisms Driving Senescence in Adipose Tissue

- Replication-Driven Telomere Shortening (Replicative Senescence). With advancing age or repeated cell divisions, adipose progenitor cells undergo telomere attrition. Critically shortened telomeres trigger a DNA damage response (DDR) that enforces cell-cycle arrest (p53/p21Cip1 and p16INK4a pathways) and commits these cells to a senescent fate [16,17,18]. In cardio-metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes, chronic oxidative stress accelerates telomere loss, causing premature replicative senescence in both preadipocytes and mature adipocytes [19]. Once replicative senescence is established, affected cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6), further promoting local tissue dysfunction.

- Chronic Oxidative and Inflammatory Stress (Stress-Induced Premature Senescence). Excess caloric intake and nutrient overload heighten mitochondrial ROS production in adipocytes, triggering the DDR independent of telomere length [20,21,22]. In obese adipose depots, elevated levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and other inflammatory mediators create a hostile microenvironment. Preadipocytes and adipocytes exposed to hyperinsulinemia, common in insulin-resistant states, can also enter senescence: prolonged insulin stimulation by itself has been shown to drive human adipocytes into a senescent phenotype [23]. Thus, inflammatory cytokines and ROS work in concert to induce premature cellular aging in fat tissue.

- Obesity-Related Mechanical and Paracrine Signals. As adipocytes hypertrophy, they outgrow their vascular supply and become hypoxic. Hypoxia induces HIF-1α signaling and further ROS generation, reinforcing the senescence program. Additionally, enlarged adipocytes and resident macrophages secrete SASP factors (e.g., CCL2/MCP-1) that recruit more immune cells, amplifying local inflammation – an environment often called “metaflammation” [20]. This paracrine loop accelerates senescence in neighboring adipocytes and stromal cells.

- Chronic SASP Promotes Immune Cell Infiltration. Senescent adipocytes secrete chemokines like MCP-1 and IL-8, attracting macrophages and T cells into fat depots. Those infiltrating immune cells, in turn, produce additional pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β), maintaining a persistent low-grade inflammatory state.

- Disruption of Adipocyte Function. SASP factors (IL-6, TGF-β) downregulate adipogenic transcription factors (e.g., PPARγ) and insulin-signaling proteins (AKT phosphorylation), impairing glucose uptake and lipid storage. Consequently, fewer new adipocytes form, and concomitantly, senescent preadipocytes lose the ability to differentiate, resulting in a fat tissue filled with fewer, larger adipocytes that are insulin-resistant and prone to lipolysis. Elevated free fatty acids spill into circulation, leading to ectopic lipid accumulation in the liver and muscle, and aggravating systemic insulin resistance [4].

- Feed-Forward ROS–SASP Cycle. Heightened ROS in adipose cells drives stress-induced premature senescence. Those senescent cells, via their SASP, secrete additional cytokines and chemokines that recruit inflammatory cells, which produce yet more ROS. This vicious cycle creates a “metabolic-senescence” loop in which metabolic dysfunction both causes and results from increased senescence and SASP activity [24,25].

3.2. Consequences of Adipose Senescence on Insulin Resistance

3.3. Senolytic Interventions in Obesity Models

4. Senescence and Metabolic Dysfunction in the Liver

4.1. Senescent Hepatocytes and SASP

4.2. Senescence in Non-Parenchymal Liver Cells

- Cholangiocytes: Bile duct epithelial cells exhibit p16 upregulation in cholangiopathies (e.g., primary biliary cholangitis), contributing to ductal inflammation [33].

- Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells (LSECs): Aged LSECs display a senescent phenotype (p16INK4a, inflammatory markers), which compromises the sinusoidal barrier and promotes fibrosis [34,35]. However, wholesale clearance of senescent LSECs may impair filtration, highlighting a need for cell-specific targeting.

- Hepatic Stellate Cells (HSCs): In early fibrosis, acute HSC senescence can limit scarring by secreting MMPs that degrade collagen [36]. In chronic disease, however, persistently activated HSCs adopt a senescence-associated, profibrotic SASP, exacerbating matrix deposition and cirrhosis.

4.3. Vicious Cycle: Insulin Resistance ↔ Hepatocyte Senescence

5. SASP and Chronic Inflammation Across Metabolic Tissues

- Components of Chronic SASP. The SASP encompasses pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α), chemokines (MCP-1, IL-8), growth factors (TGF-β, VEGF), matrix-remodeling proteases (MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-9), and non-protein mediators such as microRNAs and lipid-derived oxylipins [13,39,40]. While these factors initially recruit immune cells to clear damaged or senescent cells, their unchecked accumulation drives “inflammaging” – a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation that underlies many age-related and metabolic disorders [41].

- Paracrine Induction of Neighboring Cells. Persistent SASP does more than attract macrophages or T cells; it actively induces senescence in nearby healthy cells (“paracrine senescence”), creating a self-propagating wave of cellular aging and inflammation [15]. This feed-forward cycle magnifies tissue dysfunction far beyond the original senescent population.

- Pancreatic β-Cells and Islet Dysfunction. In the context of metabolic stress (hyperglycemia, lipotoxicity), β-cells become prone to senescence. SASP factors like IL-6 and IL-1β impair insulin secretion and recruit inflammatory cells into the islets of Langerhans. Moreover, paracrine SASP signaling induces senescence in neighboring β-cells and resident macrophages, causing a progressive loss of functional β-cell mass. As a result, hyperglycemia worsens and the transition from insulin resistance to overt type 2 diabetes accelerates [42].

- Adipose Tissue and Insulin Resistance. Hypertrophic expansion of adipocytes under obesity leads to local hypoxia, oxidative stress, and inflammation—key triggers for adipocyte senescence. Senescent adipocytes release elevated levels of SASP factors (IL-6, MCP-1), which further recruit macrophages and perpetuate inflammation. This chronic SASP environment disrupts insulin signaling in both senescent and nearby non-senescent adipocytes, driving systemic insulin resistance (see Section 5) [43].

- Liver and Fibrosis. In NAFLD and NASH, lipid overload and ROS induce hepatocyte and stellate cell senescence. Senescent hepatocytes secrete inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6) and profibrotic factors (TGF-β) that activate hepatic stellate cells, promoting extracellular matrix deposition and fibrosis. Meanwhile, senescent stellate cells produce MMPs that remodel the matrix – yet their chronic SASP skews the balance toward scar formation. This sustained inflammatory and fibrotic SASP milieu exacerbates hepatic dysfunction and accelerates progression from steatosis to cirrhosis (see Section 6) [44].

6. Therapeutic Interventions

6.1. Senolytics: Targeted Elimination of Senescent Cells

- Dasatinib + Quercetin (D + Q): Dasatinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) plus quercetin (a flavonoid) downregulates anti-apoptotic molecules in senescent cells [28,45]. In obese mice, four weeks of D + Q decreased SA-β-gal+ adipose cells by ~60 %, reduced inflammation (TNF-α, IL-6) by ~40 %, and improved glucose tolerance by 30 % [29]. In a Phase 1 trial (NCT02848131) of diabetic kidney disease patients, a single course of D + Q reduced kidney and adipose senescent markers (p16INK4a, p21CIP1) by 50 % post-treatment [30].

- BCL-2 Family Inhibitors (ABT-263, ABT-199): Senescent cells often upregulate BCL-2/BCL-XL to evade apoptosis [46]. ABT-263 (Navitoclax) effectively cleared senescent β-cells in MIN6 cell lines and restored glucose tolerance in high-fat diet mice (HOMA-IR ↓ 25 %) [47]. ABT-199 (Venetoclax) eliminated senescent β-cells in NOD mice and prevented the onset of type 1 diabetes in 100 % of treated animals vs 20 % in controls [48].

- SA-β-gal Prodrugs (SSK1, Nav-Gal): These prodrugs exploit SA-β-gal activity, enriched in senescent cells, to release cytotoxins selectively. SSK1 showed 10-fold higher potency than ABT-263 in eliminating cultured senescent fibroblasts and reduced inflammatory cytokines by 60 % in aged mice [49]. Nav-Gal (Navitoclax-galactose conjugate) cleared senescent lung and liver cells with minimal platelet toxicity, reducing fibrosis scores by 45 % in murine models when combined with cisplatin [50]. Their role in metabolic tissues remains to be validated.

6.2. Senomorphics: Modulating the SASP

- JAK Inhibitors (Ruxolitinib, Tofacitinib): By blocking JAK/STAT signaling, these agents reduce IL-6 and CCL2 secretion. In obese rodents, ruxolitinib decreased circulating IL-6 by 50 % and improved insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR ↓ 35 %) [51].

- Rapamycin (mTOR Inhibition): Rapamycin suppresses NF-κB-mediated SASP transcription. In aged mice, rapamycin reduced SASP factors (IL-1β, IL-6) by 45%, extended healthspan, and improved metabolic profiles [18].

- Metformin (AMPK Activation): Though not a classical senomorphic, metformin indirectly reduces SASP by improving mitochondrial function and lowering hyperglycemia. In human adipose stromal cells, metformin decreased p16INK4a expression by 30 % and reduced SASP secretion (IL-6, IL-1β) by 40 % [52]. Combined with rapamycin, metformin prevented diet-induced adipose senescence in mice (SA-β-gal+ cells ↓ 60 %) [53].

6.3. Immune-Mediated Clearance of Senescent Cells

- Senolytic CAR T Cells: CAR T cells engineered to recognize urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) on senescent cells eliminated > 80 % of targeted cells in fibrotic lung and liver models, reducing tissue fibrosis by 50 % and restoring metabolic function [54]. Identification of additional senescence-specific surface markers (e.g., DPP4, CD44) remains critical to minimize off-target toxicity.

6.4. Lifestyle and Preventive Measures

- Exercise: Aerobic and resistance training in obese humans reduced muscle SA-β-gal+ cells by 30 % and improved insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR ↓ 20 %) [55].

- Caloric Restriction & Intermittent Fasting: These regimens activate autophagy and mitophagy pathways that clear damaged organelles and may prevent cells from entering senescence. In aged rodents, 30 % caloric restriction lowered p16INK4a+ cells in liver and adipose by 40 % and improved glucose tolerance by 35 % [56].

7. Future Directions

7.1. Define Tissue-Specific SASP Signatures

- Single-cell Omics: Utilize single-cell RNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics to catalogue senescent subpopulations across adipose, liver, islets, and muscle—identifying unique SASP profiles (protein, lipid, miRNA) and surface markers for targeted interventions.

- Biomarker Validation: Systematically validate novel senescence markers (e.g., DPP4, CD44, uPAR) in human biopsies to distinguish pathologic SASP from physiologic (transient) SASP.

7.2. Develop High-Specificity Senotherapeutics

- Prodrug Optimization: Advance SA-β-gal prodrugs (SSK1, Nav-Gal) to phase I trials in patients with early-stage NAFLD/NASH, focusing on pharmacokinetics, dose escalation, and metabolic endpoints (HOMA-IR, ALT/AST).

7.3. Evaluate Long-Term Safety & Efficacy

- Longitudinal Preclinical Studies: Examine repeated dosing of senolytics/senomorphics in aged and obesity models over 12 months to assess chronic toxicity, organ function (renal, hepatic), and systemic immunity.

- Human Trials: Conduct randomized, placebo-controlled trials of D + Q (or next-gen senolytics) in patient cohorts with diabetic nephropathy, early NASH, or prediabetes—monitoring clinical endpoints (HbA1c, fibrosis scores, insulin sensitivity) and senescence biomarkers (circulating SASP factors, p16INK4a+ cell counts).

7.4. Integrate Lifestyle & Pharmacology

- Combine caloric restriction mimetics (e.g., rapalogs) with senolytics in animal models to test for synergistic effects on tissue rejuvenation and metabolic health—informing future clinical protocols.

7.5. Uncover Mechanisms of Senescence Reversal

- Investigate whether “senescence reversion” is possible (e.g., transient blockade of p53/p21 pathways plus autophagy induction) to restore cell function instead of clearance.

- Test whether partial SASP inhibition (e.g., JAK inhibitors) can tip the balance from a pathogenic to a regenerative secretome, promoting tissue repair without immunosuppression.

8. Summary of Key Findings

8.1. Mechanistic Insights

- Senescent Cells Accumulate in Metabolic Tissues: Aging, obesity, and hyperinsulinemia induce DNA damage, telomere attrition, and ROS production in adipose, liver, pancreatic β-cells, and muscle.

- SASP Drives Chronic Inflammation (“Inflammaging”): Senescent cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α), chemokines (MCP-1), matrix remodelers (MMPs), and lipid mediators (oxylipins), disrupting tissue homeostasis.

- Feedback Loops Fuel Disease: In adipose, hypertrophy and SASP impair insulin signaling. In liver, SASP from hepatocytes and stellate cells promotes fibrosis and worsens NAFLD/NASH. Pancreatic SASP accelerates β-cell loss and hyperglycemia.

- Mitochondrial Dysfunction as a Shared Node: Across tissues, senescent cells accumulate dysfunctional mitochondria, generate excess ROS, and fail to meet energetic demands, leading to cell-cycle arrest and metabolic rewiring.

8.2. Therapeutic Outlook

- Senolytics Show Preclinical Efficacy: Drugs like D + Q, ABT-263/199, and SA-β-gal prodrugs (SSK1, Nav-Gal) selectively clear senescent cells, reduce SASP burden (IL-6, IL-1β), and improve glucose tolerance (↑ 30 %) in mouse models.

- Senomorphics Attenuate SASP: Agents such as ruxolitinib, rapamycin, and metformin blunt SASP production, lower inflammation (SASP factors ↓ 45 – 60 %), and enhance insulin sensitivity.

- Immune Strategies and Lifestyle Measures Complement Pharmacology: Vaccines against senescence antigens and senolytic CAR T cells show proof-of-concept in murine fibrosis models; exercise and caloric restriction reduce senescent-cell markers (p16INK4a+, SA-β-gal+) by 30 – 40 %.

9. Conclusion

| Tissue | Senescent Cell Types | Common Senescence Markers | SASP Components | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose Tissue | Adipocytes, Preadipocytes, APCs | p16INK4a, p21CIP1, SA-β-gal, γ-H2AX, LMNB1↓ | IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, MCP-1, MMPs, PAI-1 | Impaired adipogenesis, insulin resistance, inflammation, fibrosis. [57,58] |

| Liver | Hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, LSECs | p16INK4a, p21CIP1, SA-β-gal, γ-H2AX, TAFs, LMNB1↓ | TGF-β1, IL-6, IL-1β, MCP-1, MMP-2/9, VEGF | Steatosis, insulin resistance, fibrosis, inflammation [31,59] |

| Pancreatic Islets | β-cells | p16INK4a, p21CIP1, SA-β-gal, p53 | IL-6, IL-8, CXCL1, IGFBPs, SASP miRNAs | β-cell dysfunction, reduced proliferation, impaired insulin secretion [60,61] |

| Skeletal Muscle | Fibroadipogenic progenitors (FAPs), Satellite cells | p16INK4a, p21CIP1, γ-H2AX, SA-β-gal, SASP miRs | IL-6, TNF-α, MMP-3/9, PAI-1, TGF-β | Muscle regeneration failure, sarcopenia, inflammation [62,63] |

References

- Kumari R, Jat P. Mechanisms of Cellular Senescence: Cell Cycle Arrest and Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021; 9:645593. [CrossRef]

- Matjusaitis M, Chin G, Sarnoski EA, Stolzing A. Biomarkers to identify and isolate senescent cells. Ageing Research Reviews 2016; 29:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Martin N, Popgeorgiev N, Ichim G, Bernard D. BCL-2 proteins in senescence: beyond a simple target for senolysis? Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2023; 24:517-8. [CrossRef]

- Spinelli R, Baboota RK, Gogg S, Beguinot F, Blüher M, Nerstedt A, et al. Increased cell senescence in human metabolic disorders. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2023; 133:e169922. [CrossRef]

- Meijnikman AS, Herrema H, Scheithauer TPM, Kroon J, Nieuwdorp M, Groen AK. Evaluating causality of cellular senescence in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. JHEP Reports 2021; 3:100301. [CrossRef]

- Baboota RK, Rawshani A, Bonnet L, Li X, Yang H, Mardinoglu A, et al. BMP4 and Gremlin 1 regulate hepatic cell senescence during clinical progression of NAFLD/NASH. Nature Metabolism 2022; 4:1007-21. [CrossRef]

- Childs BG, Durik M, Baker DJ, van Deursen JM. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: from mechanisms to therapy. Nature medicine 2015; 21:1424-35. [CrossRef]

- Kudlova N, De Sanctis JB, Hajduch M. Cellular Senescence: Molecular Targets, Biomarkers, and Senolytic Drugs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022; 23:4168. [CrossRef]

- Kandhaya-Pillai R, Miro-Mur F, Alijotas-Reig J, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL, Schwartz S. TNFα-senescence initiates a STAT-dependent positive feedback loop, leading to a sustained interferon signature, DNA damage, and cytokine secretion. Aging 2017; 9:2411-35. [CrossRef]

- Coppé J-P, Desprez P-Y, Krtolica A, Campisi J. The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype: The Dark Side of Tumor Suppression. Annual review of pathology 2010; 5:99-118. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda S, Revandkar A, Dubash TD, Ravi A, Wittner BS, Lin M, et al. TGF-β in the microenvironment induces a physiologically occurring immune-suppressive senescent state. Cell reports 2023; 42:112129. [CrossRef]

- Marcozzi S, Bigossi G, Giuliani ME, Lai G, Giacconi R, Piacenza F, et al. Spreading Senescent Cells’ Burden and Emerging Therapeutic Targets for Frailty. Cells 2023; 12:2287. [CrossRef]

- Wiley CD, Campisi J. The metabolic roots of senescence: mechanisms and opportunities for intervention. Nature metabolism 2021; 3:1290-301. [CrossRef]

- Ohtani N. The roles and mechanisms of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP): can it be controlled by senolysis? Inflammation and Regeneration 2022; 42:11. [CrossRef]

- Salminen A. Feed-forward regulation between cellular senescence and immunosuppression promotes the aging process and age-related diseases. Ageing Research Reviews 2021; 67:101280. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Wang L, Wang Z, Liu J-P. Roles of Telomere Biology in Cell Senescence, Replicative and Chronological Ageing. Cells 2019; 8:54. [CrossRef]

- Martin H, Doumic M, Teixeira MT, Xu Z. Telomere shortening causes distinct cell division regimes during replicative senescence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell & Bioscience 2021; 11:180. [CrossRef]

- Lagoumtzi SM, Chondrogianni N. Senolytics and senomorphics: Natural and synthetic therapeutics in the treatment of aging and chronic diseases. Free Radic Biol Med 2021; 171:169-90. [CrossRef]

- Koliada AK, Krasnenkov DS, Vaiserman AM. Telomeric aging: mitotic clock or stress indicator? Frontiers in Genetics 2015; 6:82. [CrossRef]

- Minamino T, Orimo M, Shimizu I, Kunieda T, Yokoyama M, Ito T, et al. A crucial role for adipose tissue p53 in the regulation of insulin resistance. Nature Medicine 2009; 15:1082-7. [CrossRef]

- Coleman PR, Hahn CN, Grimshaw M, Lu Y, Li X, Brautigan PJ, et al. Stress-induced premature senescence mediated by a novel gene, SENEX, results in an anti-inflammatory phenotype in endothelial cells. Blood 2010; 116:4016-24. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Wei D, Xiao H. Methods of cellular senescence induction using oxidative stress. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, NJ) 2013; 1048:135-44. [CrossRef]

- Baboota RK, Spinelli R, Erlandsson MC, Brandao BB, Lino M, Yang H, et al. Chronic hyperinsulinemia promotes human hepatocyte senescence. Molecular Metabolism 2022; 64:101558. [CrossRef]

- Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, et al. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2004; 114:1752-61. [CrossRef]

- Lindsay RT, Rhodes CJ. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Metabolic Disease-Don't Shoot the Metabolic Messenger. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025; 26:2622. [CrossRef]

- Voynova E, Kulebyakin K, Grigorieva O, Novoseletskaya E, Basalova N, Alexandrushkina N, et al. Declined adipogenic potential of senescent MSCs due to shift in insulin signaling and altered exosome cargo. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2022; 10:1050489. [CrossRef]

- Wan YCE, Dufau J, Spalding KL. Local and systemic impact of adipocyte senescence-associated secretory profile. Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research 2024; 37:100547. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, Gower AC, Ding H, Giorgadze N, et al. The Achilles' heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015; 14:644-58. [CrossRef]

- Murakami T, Inagaki N, Kondoh H. Cellular Senescence in Diabetes Mellitus: Distinct Senotherapeutic Strategies for Adipose Tissue and Pancreatic β Cells. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022; 13:869414. [CrossRef]

- Hickson LJ, Langhi Prata LGP, Bobart SA, Evans TK, Giorgadze N, Hashmi SK, et al. Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: Preliminary report from a clinical trial of Dasatinib plus Quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. EBioMedicine 2019; 47:446-56. [CrossRef]

- Udomsinprasert W, Sobhonslidsuk A, Jittikoon J, Honsawek S, Chaikledkaew U. Cellular senescence in liver fibrosis: Implications for age-related chronic liver diseases. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 2021; 25:799-813. [CrossRef]

- Anastasopoulos N-A, Charchanti AV, Barbouti A, Mastoridou EM, Goussia AC, Karampa AD, et al. The Role of Oxidative Stress and Cellular Senescence in the Pathogenesis of Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease and Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Antioxidants 2023; 12:1269. [CrossRef]

- Park J-W, Kim J-H, Kim S-E, Jung JH, Jang M-K, Park S-H, et al. Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: Current Knowledge of Pathogenesis and Therapeutics. Biomedicines 2022; 10:1288. [CrossRef]

- Grosse L, Bulavin DV. LSEC model of aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2020; 12:11152-60. [CrossRef]

- Gao J, Zuo B, He Y. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells as potential drivers of liver fibrosis (Review). Molecular Medicine Reports 2024; 29:40. [CrossRef]

- Krizhanovsky V, Yon M, Dickins RA, Hearn S, Simon J, Miething C, et al. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell 2008; 134:657-67. [CrossRef]

- Guo J, Huang X, Dou L, Yan M, Shen T, Tang W, et al. Aging and aging-related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022; 7:1-40. [CrossRef]

- Guo X, Wen S, Wang J, Zeng X, Yu H, Chen Y, et al. Senolytic combination of dasatinib and quercetin attenuates renal damage in diabetic kidney disease. Phytomedicine: International Journal of Phytotherapy and Phytopharmacology 2024; 130:155705. [CrossRef]

- Basisty N, Kale A, Jeon OH, Kuehnemann C, Payne T, Rao C, et al. A proteomic atlas of senescence-associated secretomes for aging biomarker development. PLoS biology 2020; 18:e3000599. [CrossRef]

- Han X, Lei Q, Xie J, Liu H, Li J, Zhang X, et al. Potential Regulators of the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype During Senescence and Aging. The Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 2022; 77:2207-18. [CrossRef]

- Baechle JJ, Chen N, Makhijani P, Winer S, Furman D, Winer DA. Chronic inflammation and the hallmarks of aging. Molecular Metabolism 2023; 74:101755. [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan A, Flores RR, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ. Role of Cellular Senescence in Type II Diabetes. Endocrinology 2021; 162:bqab136. [CrossRef]

- Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, van Deursen J, Campisi J, Kirkland JL. Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory phenotype: therapeutic opportunities. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2013; 123:966-72. [CrossRef]

- Pedroza-Diaz J, Arroyave-Ospina JC, Serna Salas S, Moshage H. Modulation of Oxidative Stress-Induced Senescence during Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2022; 11:975. [CrossRef]

- Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T. Senolytic drugs: from discovery to translation. Journal of Internal Medicine 2020; 288:518-36. [CrossRef]

- Yosef R, Pilpel N, Tokarsky-Amiel R, Biran A, Ovadya Y, Cohen S, et al. Directed elimination of senescent cells by inhibition of BCL-W and BCL-XL. Nature Communications 2016; 7:11190. [CrossRef]

- Aguayo-Mazzucato C, Andle J, Lee TB, Midha A, Talemal L, Chipashvili V, et al. Acceleration of β Cell Aging Determines Diabetes and Senolysis Improves Disease Outcomes. Cell Metabolism 2019; 30:129-42.e4. [CrossRef]

- Thompson PJ, Shah A, Ntranos V, Van Gool F, Atkinson M, Bhushan A. Targeted Elimination of Senescent Beta Cells Prevents Type 1 Diabetes. Cell Metabolism 2019; 29:1045-60.e10. [CrossRef]

- Cai Y, Zhou H, Zhu Y, Sun Q, Ji Y, Xue A, et al. Elimination of senescent cells by β-galactosidase-targeted prodrug attenuates inflammation and restores physical function in aged mice. Cell Research 2020; 30:574-89. [CrossRef]

- González-Gualda E, Pàez-Ribes M, Lozano-Torres B, Macias D, Wilson JR, González-López C, et al. Galacto-conjugation of Navitoclax as an efficient strategy to increase senolytic specificity and reduce platelet toxicity. Aging Cell 2020; 19:e13142. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Pitcher LE, Prahalad V, Niedernhofer LJ, Robbins PD. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: senolytics and senomorphics. The FEBS journal 2023; 290:1362-83. [CrossRef]

- Le Pelletier L, Mantecon M, Gorwood J, Auclair M, Foresti R, Motterlini R, et al. Metformin alleviates stress-induced cellular senescence of aging human adipose stromal cells and the ensuing adipocyte dysfunction. eLife 2021; 10:e62635. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni AS, Gubbi S, Barzilai N. Benefits of Metformin in Attenuating the Hallmarks of Aging. Cell metabolism 2020; 32:15-30. [CrossRef]

- Amor C, Feucht J, Leibold J, Ho Y-J, Zhu C, Alonso-Curbelo D, et al. Senolytic CAR T cells reverse senescence-associated pathologies. Nature 2020; 583:127-32. [CrossRef]

- Podraza-Farhanieh A, Spinelli R, Zatterale F, Nerstedt A, Gogg S, Blüher M, et al. Physical training reduces cell senescence and associated insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Molecular Metabolism 2025; 95:102130. [CrossRef]

- Cassidy LD, Narita M. Autophagy at the intersection of aging, senescence, and cancer. Molecular Oncology 2022; 16:3259-75. [CrossRef]

- DeBari MK, Abbott RD. Adipose Tissue Fibrosis: Mechanisms, Models, and Importance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020; 21:6030.

- Nerstedt A, Smith U. The impact of cellular senescence in human adipose tissue. Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling 2023; 17:563-73. [CrossRef]

- Ogrodnik M, Miwa S, Tchkonia T, Tiniakos D, Wilson CL, Lahat A, et al. Cellular senescence drives age-dependent hepatic steatosis. Nature Communications 2017; 8:15691. [CrossRef]

- Aguayo-Mazzucato, C. Functional changes in beta cells during ageing and senescence. Diabetologia 2020; 63:2022-9. [CrossRef]

- Li K, Bian J, Xiao Y, Wang D, Han L, He C, et al. Changes in Pancreatic Senescence Mediate Pancreatic Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023; 24:3513. [CrossRef]

- Wan M, Gray-Gaillard EF, Elisseeff JH. Cellular senescence in musculoskeletal homeostasis, diseases, and regeneration. Bone Research 2021; 9:41. [CrossRef]

- Saito Y, Chikenji TS. Diverse Roles of Cellular Senescence in Skeletal Muscle Inflammation, Regeneration, and Therapeutics. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021; 12:739510. [CrossRef]

| SASP Component | Examples | Key Effects on Tissue Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory cytokines | IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α | Promote chronic inflammation; interfere with insulin signaling (e.g., IL-6 can induce insulin resistance); can reinforce senescence in an autocrine manner. [8,9] and cytokine secretion |

| Chemokines | IL-8 (CXCL8), CCL2 (MCP-1), CXCL1 | Recruit immune cells (neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages) to senescent cell sites, leading to immune infiltration and potentially clearing senescent cells or causing bystander damage. [10] |

| Growth factors | TGF-β1, VEGF, IGF-binding proteins | Induce fibrosis and tissue remodeling (TGF-β drives myofibroblast activation and matrix deposition); stimulate angiogenesis; reinforce senescent growth arrest and alter differentiation of neighboring cells. [14] |

| Proteases & ECM Modifiers | MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-9, uPA | Degrade extracellular matrix components, leading to tissue structure changes and facilitating inflammatory cell migration, can cause loss of tissue integrity and function. [10] |

|

Other factors |

MicroRNAs (in exosomes), Ceramides, Oxylipins | Modify gene expression and metabolism in recipient cells (e.g., senescence-associated miRNAs can suppress target genes in neighbors); lipid mediators can act as local hormones, amplifying inflammatory or senescence signaling. [13] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).