1. Introduction

The human immune system is constantly under siege from microbes and pathogens. The respiratory tract, due to constant interaction with airborne pathogens, is especially vulnerable to bacterial exposure, and as such has developed multiple lines of defense to prevent infection. Among the different immune cells that respond to pathogens in the lungs, tissue-resident alveolar macrophages are the front-line responders to inhaled pathogens. Alveolar macrophages play a vital role in host defense and homeostasis, as they phagocytose microbes and cellular debris within the fragile alveolar compartment. This task requires a high level of energy demand and requires proper mitochondrial function for a robust yet balanced response that removes bacteria and restores order. The transcription factor Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) is the primary energetic regulator that drives mitochondrial biogenesis and turnover. PGC-1α function is influenced through the activity of other transcription factors, including mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) and transcription factor EB (TFEB), in addition to critical cofactors, paramount among them: elemental zinc (Zn).

The atypical transition metal Zn is an indispensable component of many physiological processes, including immunity and metabolism, with over 3000 different proteins and enzymes reliant upon Zn for functional or catalytic activity [

1,

2,

3]. It is well established that Zn is essential for proper immune system function, with dietary-induced deficiency resulting in elevated inflammation and impaired responses to pathogens and excess causing cytotoxicity and cell death [

4]. Accordingly, the transport of Zn in and out of cells is tightly regulated to maintain a narrow window of homeostatic concentrations [

2,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The primary regulators of intracellular zinc levels are transmembrane transporters belonging to two different families that control intracellular Zn import through Zrt-Irt protein (ZIPs

1-14), and export through ZnTs

1-10. ZIPs and ZnTs function in a coordinated manner in order to shuttle Zn into and out of cells to always maintain essential cellular function.

Due to high energy requirements that drive host defense, immune cells are highly reliant upon efficient mitochondrial function, which is directly coupled to access to available intracellular Zn. Thus, Zn transport into and out of cells is tightly regulated and a highly controlled process[

11]. Deficits in cytosolic Zn through ZIPs or excess accumulation due to defective export through ZnTs can also adversely impact mitochondrial function. Among the Zn-importing family members, our group was the first to reveal that ZIP8 is indispensable in myeloid cell function in response to bacterial infection[

12,

13,

14]. In particular, ZIP8 expression is rapidly induced upon infection and mobilizes Zn from the vasculature into the cytosol, where it then serves a number of functions, resulting in a robust yet balanced proinflammatory response [

1]. Loss of ZIP8 expression in bone marrow-derived macrophages and dendritic cells results in a significant reduction in available Zn, an overly exuberant inflammatory response, and reduced bacterial clearance [

15].

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) refer to mycobacteria other than

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb) and

M. leprae. NTM are Gram-positive, acid-fast, aerobic bacilli that are ubiquitous in the environment and can be normal inhabitants of natural and drinking water systems, pools, hot tubs, bird droppings, dust, milk, soil, and even laboratory equipment. The incidence and prevalence of NTM-related disease are rising at an alarming rate worldwide. This increase has been attributed to environmental and climate changes, genetic mutations, nosocomial infections, and improved molecular testing. Of significant concern is increasing rates of antibiotic resistance and morbidity associated with prolonged infection, especially in the elderly and non-smoking women. Chronic pulmonary bacterial infections place a heavy immunological burden on lung cells, due to the prolonged and often unrecognized course of infection.

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is a species of nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) that is present in the environment that humans frequently encounter. Patients with immunodeficiencies, including those with HIV, COPD, cystic fibrosis, or those who use immunosuppressant agents, are at an elevated risk for pathogenic infection and pulmonary complications [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Current treatment protocols involve the use of multiple antibiotics for extended intervals, which are becoming less effective due to the emergence of drug-resistant strains. Because of this, alternative treatment options are needed. A relatively new paradigm has emerged that aims to enhance the bactericidal activity of immune cells through host-directed therapies (HDT). Increasing the activity and effectiveness of an individual’s immune cells has the potential to circumvent antibiotic resistance, resulting in improved outcomes. Based on this, we have chosen to identify factors that enhance PGC-1α expression and function in phagocytic cells as a viable strategy to improve bacterial clearance in the lung [

20].

Our previous work was the first to reveal that pharmacological activation of PGC-1α has a positive impact on the ability of macrophages to eradicate MAC and other NTMs[

21,

22,

23]. Herein, we reveal that Zn has a positive impact on the expression and activity of PGC-1α and that the Zn transporter ZIP8 serves as a vital conduit for the mobilization of Zn into macrophages in response to NTM infection. First, we show the effects of Zn deficiency and Zn supplementation on antibacterial activity in macrophages. We then reveal that Zn serves as an immunomodulator by regulating mitochondrial function through PGC-1α and related cofactors. Expanding from this, we investigated the effects of Zn supplementation on macrophages to attenuate MAC-mediated deficits in mitochondrial and immune activity. To investigate the mechanism, we utilized a novel ZIP8-KO mouse model to determine the influence of this specific Zn importer on PGC-1α-mediated immune cell function during MAC infection. Our results show the interplay between Zn concentrations and levels of PGC-1α within macrophages, providing a hitherto uninvestigated link between PGC-1α-mediated mitochondria function in immune cells and cellular zinc concentrations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Chemicals

The following primers were acquired from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA) and used for PCR: ppargc1 (Mm01208835_m1, hs01016719), tfam (Mm00447485_m1, Hs00273372_s1), gapdh (Mm99999915_g1, hs02786624). The following primary and secondary antibodies were used: PGC-1α (Cell Signaling Technology (CST), Danvers, MA 2178), PGC-1α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology (SCBT), Dallas, TX sc-518025), TFAM (CST, 8076), mtTFA (SCBT, sc-166965), β-Actin (CST, 3700), β-Tubulin (CST, 2146) Anti-rabbit IgG HRP (CST, 7074), Anti-mouse IgG HRP (CST, 7076), Goat anti-Rabbit IgG AF 488 (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, A11008), Donkey anti-Mouse IgG AF 647 (Invitrogen, A31571). MitoTracker Green FM (MTG) (Invitrogen, M7514), Tetramethylrhodamine Methyl Ester (TMRM) (Invitrogen, T668), MitoSOX Red (Invitrogen, M36007) 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI) (CST, 4083), Hoechst 33342 (CST, 4082). Unless otherwise specified, reagents and chemicals were obtained through Sigma Aldrich or Thermo Scientific.

2.2. Animal Use and Care

Animals were maintained at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) Animal Facility under pathogen-free conditions, with food and water provided ad libitum. Research protocols were approved by the UNMC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), under protocols 22-007-04-FC and 16-127. Animal care and procedures were performed in accordance with NIH and Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW) Guidelines.

Wildtype (WT) mice used were 4-6-week-old female C57BL/6J (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME).

Zip8 knockout mice (

Zip8KO) were generated as previously described [

24]. Conditional-ready

Zip8flox/flox mice from

Zip8flox-neo/+ mice (C57BL/6NTac-Slc39a8tm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi/Cnrm) were obtained from the European Mouse Mutant Archive. Heterozygous

Zip8flox-neo/+ mice were bred to ROSA26:FLPe knock-in mice with ubiquitous expression of FLP1 recombinase (129S4/SvJaeSor- Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(FLP1) Dym/J; Jackson Laboratory) to delete the Neo cassette adjacent to the upstream loxP site. The resulting

Zip8flox/+ were mated to produce

Zip8flox/flox mice.

ZIP8 flox/flox mice were crossed to myeloid cell specific LysMcre (The Jackson Laboratory) to generate the conditional

Zip8KO [

15,

24].

2.3. Cell Culture

Human monocyte cell lines U-937 (CRL-1593.2 ATCC, Manassas, VA) and THP-1 (TIB-202, ATCC) were grown in RPMI media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (PS) and cultured in T75 flasks with media changes every other day. Upon reaching confluence, cells were transferred to 15 mL conical tubes and centrifuged at 1300 x g for 5 minutes. Media was aspirated and the cell pellet resuspended in 1 mL of culture media and filtered through a 70 µm nylon strainer. Cells were counted using a Cell Countess II (Invitrogen) and seeded into plates at the following densities: 6-well 8x105, 12-well 4x105, 96-well 2.5x104. Cells were differentiated into macrophages using PMA [30 ng/mL] for 2 days. Upon differentiation, PMA-containing media was aspirated, wells gently washed with warm PBS and incubated with culture media.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were harvested from 4-6-week-old adult C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and sacrificed via cervical dislocation, and hind legs were aseptically dissected, removed, and femurs were collected in basal RPMI media and placed on ice. The diaphysis of femurs were cut with scissors, and a 27-G needle and syringe with RPMI were used to flush the bone marrow into a 50 mL conical tube. The bone marrow solution was filtered through a 70 µm nylon filter and centrifuged at 1300xG for 6 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and ACK lysing buffer (Gibco) was added to the cell pellet with gentle pipetting to resuspend. An equal volume of RPMI media was added, and the cells were recentrifuged. The supernatant was removed, and cell pellet was resuspended in DMEM culture media containing mouse M-CSF [50 ng/µL]. Cells were plated in tissue culture dishes (Corning) and placed in incubator to allow cells to adhere. Media was changed every other day for 5-7 days until cells became adherent and confluent. Upon reaching confluence, media was aspirated, and dishes gently washed with PBS and incubated for 20 minutes with 0.25% Trypsin. Gentle scraping was used to detach cells, which were added to a 15 mL conical tube with an equal volume of cell culture media. Cells were centrifuged, supernatant removed, and pellet suspended in 1 mL of culture media. Cells were then counted and added to cell culture plates at the following densities: 6-well 1.2x106, 12-well 6x105, 96-well 4.5x104.

2.4. Bacterial Culture

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) (MAC 101 70089, ATCC) was cultured in liquid 7H9 media containing 10% OADC (oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, catalase) supplement and placed in an orbital incubator at 300 RPM at 35˚C for ~48 hours until reaching an OD

600 of ~0.7. Bacterial suspensions were collected and centrifuged at 13,000 RPM for 12 minutes, the supernatant discarded, the pellet washed in PBS, and recentrifuged. Bacterial pellets were then resuspended in PBS, aliquoted into individual tubes at a concentration of 2x10

6 cells/µL and stored at -80°C until use [

17,

18,

19].

2.5. Zinc Deficient Media and Zinc Treatment

Zn-deficient media was produced through chelation of FBS. Briefly, 500 mL of heat-inactivated FBS was added to a sterile 1 L Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 g of Chelex-100 (BIO-RAD), and the solution mixed overnight at 4°C. The solution was then filtered, and Zn-free serum aliquoted into 50 mL conical tubes at stored at -80°C. The Zn-free serum was used in place of normal FBS in cell culture media. To induce zinc-deficient conditions, cells were cultured with Zn-free media for 48 hours prior to infection or analysis. Zn treatment utilized ZinPRO® (ZP) supplement. ZP was diluted in sterile ddH2O and used at a final concentration of 50 µM for 48 hours prior to infection or analysis.

2.6. Bacterial Infection

Bacteria were cultured and stored as previously noted. Prior to infection, cell culture media was replaced with media containing no antibiotics. MAC cell pellets were thawed and added to culture media or directly to wells at an MOI of 1 for 4 or 24 hours [

17,

18,

19].

2.7. Total Rna Extraction

Cells in 12-well plates (3513, Corning) were cultured, treated, and infected as previously described in the Materials and Methods section. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (74106, Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cell culture media was aspirated, wells washed with PBS, and cells lysed and collected through gentle scraping. Lysates were added to RNeasy Mini Spin Columns and briefly centrifuged, with the flow-through discarded. After successive steps of washing and centrifugation with RW1 and RPE buffers, RNA was eluted with nuclease-free water and concentration determined using a NanoDrop One C (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madison, WI).

2.8. RT-PCR

cDNA was synthesized from isolated total RNA using the SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System (18091050, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, kit components and 1 μg of total RNA were added to an 8-tube strip and reverse transcriptase performed using a T-100 Thermal Cycler (BIO-RAD).

PCR was performed on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher). cDNA was mixed with TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (4444557, Applied Biosystems) and primers in a MicroAmp Optical 96-well Reaction Plate (4306737, Applied Biosystems) and sealed with MicroAmp Optical Adhesive Film (4311971, Applied Biosystems). Quantification of mRNA was determined using the ∆∆CT method.

2.9. SDS-PAGE Western BLOT

Cells in 6-well plates (3516, Corning) were cultured, treated, and infected as previously described in the Materials and Methods section. Cell culture plates were placed on ice, media was aspirated, and wells washed with ice-cold PBS. Cell Lysis Buffer (9803, Cell Signaling Technology (CST)) containing Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (78440, Thermo Scientific) was added to wells and allowed to gently rock on ice for 15 minutes. Cell lysates were collected with gentle scraping, transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, centrifuged at 12,000 RPM for 1 minute at 4°C, and briefly sonicated. Lysates were then centrifuged at 12,000 RPM for 12 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant collected. Protein concentration was determined through comparison with BSA standards using a Pierce Dilution-Free Rapid Gold BCA Protein Assay Kit (A55860, Thermo Scientific) with absorbance read on a BioTek3 Plate Reader.

Cell lysates were combined with Laemmli 4X buffer (S3401, Sigma Aldrich) and β-Mercaptoethanol and denatured at 75°C for 10 minutes. The reduced lysates were loaded into a 4-15% Mini-PROTEAN TGX SDS PAGE Gel (4561084, BIO-RAD) at a concentration of 30 µg of protein per lane with Precision Plus Protein Kaleidoscope Protein Standards (1610375, BIO-RAD). Gels were resolved in Tris/Glycine/SDS buffer (1610772, BIO-RAD) and run at 125 V for 45 minutes on a PowerPac HC Power Supply (BIO-RAD). Gels were transferred to PVDF membranes in Tris/Glycine buffer (1610771, BIO-RAD) at 10 V overnight at 4°C. Transfer efficiency was determined using Ponceau S Stain (P3504, Sigma Aldrich).

Blots were blocked and primary and secondary antibodies diluted in EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (12010020, BIO-RAD) with extensive washing after each step. Blots were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C with gentle rocking. Blots were incubated for 1 hour at RT with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Protein expression was visualized through the addition of SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (34094, Thermo Scientific) and imaged on a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (12003154, BIO-RAD). Blots were stripped using Restore PLUS Western Blot Stripping Buffer (46430, Thermo Scientific) and reprobed with primary and secondary antibodies. Densiometric analysis of bands was performed with ImageJ.

2.10. Immunocytochemistry

Cells were cultured in 96-well plates (Grenier Bio-One), treated and infected as previously detailed. Media was removed from 96-well plates, and wells were washed with PBS three times for 5 minutes each. Cells were fixed with PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, then washed with PBS three times for 5 minutes each. Cells were then permeabilized with PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes and washed with PBS three times for 5 minutes each. PBST containing 5% donkey serum (Gibco) was used for blocking and dilution of antibodies. Cells were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature, and solution removed and replaced with buffer containing primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Wells were washed with PBS three times for 5 minutes each, and blocking buffer containing fluorescent secondary antibodies was added to wells for 1 hour at room temperature. After removing solution and washing, cells were counterstained with DAPI [1 µg/mL] for 3 minutes, washed again with PBS three times for 5 minutes each. Cells were then imaged on a BZ-X800 confocal microscope (Keyence).

2.11. Mitochondrial Staining

Cells in 96-well plates were cultured, treated, and infected as previously described. Live cell staining utilized MitoTracker Green (MTG) (Invitrogen) and Tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester perchlorate (TMRM) (Life Technologies). Both fluorescent probes were added to HBSS at a 200 nM concentration for mitochondrial staining for 45 minutes at 37°C. The solution was removed, and wells gently washed three times with warm HBSS. Cells were counterstained with Hoechst (Cell Signaling Technology) at a concentration of 1 µg/mL in HBSS for 5 minutes, gently washed, and cell culture media without phenol red was added to wells. Cells were then imaged on a BZ-X800 confocal microscope (Keyence).

2.12. Bacterial Killing

Quantification of macrophage bactericidal activity was determined through colony counting on agar plates. BMDMs were cultured in 24-well plates and treated as previously described, and cells were infected with MAC at an MOI of 1 for 4 hours. Media was aspirated, wells were gently washed twice with HBSS, and 100 µL of PBS containing Triton X-100 (1%) and SDS (0.1%) was added to wells. Cell lysates were collected with gentle scraping and serially diluted in PBS to concentrations of 10

-4, 10

-5, 10

-7. 50 µL of diluted lysate solution was added to 7H9 agar plates and spread across the plate using an L-shaped cell spreader. Plates were placed in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO

2 atmosphere for 5-7 days, and bacterial colonies were counted and converted to CFU/mL(log) [

17,

18,

19].

2.13. Phagocytic Uptake

Phagocytic uptake by macrophages was performed using the Vybrant Phagocytosis Assay (Thermo Fisher) according to manufacturer’s instructions. BMDMs were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured as previously described. Culture media was aspirated, wells were washed with PBS, and 1 mL culture media was added to wells. Wells were gently scraped and collected for centrifugation (1200 g x 6 mins). Cell counts were determined as previously described, and DMEM was added to each tube to a final concentration of 106 cells/mL. One vial of fluorescent particles and HBSS concentrate was thawed, and 0.5 mL HBSS was added to particle vial and briefly sonicated to disperse particles. The suspension was added to a centrifuge tube containing 4.5 mL sterile ddH2O and homogenized the mixture. Cells were added to a 96-well plate at a density of 1x105 cells per well, allowed to adhere for one hour, and 100 µL of the fluorescent particle solution was added to each well and incubated for 2 hours. Media was removed from wells, and 100 µL of the trypan blue solution was added to quench extracellular fluorescence and allowed to incubate for one minute. Trypan solution was aspirated, and fluorescence (480 nm excitation/520 nm emission) was measured on a microplate reader.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate in at least 3 independent experiments, and presented data is the mean +/- standard error. Data were analyzed for statistical significance using Student t-test or ANOVA with Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) or PRISM (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

4. Discussion

Alveolar macrophages are the primary cell involved in the initial innate immune response against intracellular pathogens [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Due to their “first responder” status, alveolar macrophages require a high metabolic rate to dispatch encountered bacteria. High energy demand is predicated upon highly efficient mitochondrial function to power the cellular machinery involved in bactericidal activities [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Here, we investigated the role of Zn in regulating mitochondrial biogenesis, which is critical to rejuvenate mitochondria for effective ATP production and a robust host immune response. Our data show that Zn enhances the expression of PGC-1α and TFAM, critical transcriptional regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis. Mechanistically, we show that the Zn importer ZIP8 (Zrt/Irt-like protein) regulates Zn-mediated effects on PGC-1a and mitochondrial function.

PGC-1α is a key regulator of mitochondria biogenesis, an important quality control mechanism to maintain metabolic function of macrophages. Increased expression provides cellular signals required for the maintenance and generation of new mitochondria [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. It is also well established that Zn is required for proper immune function. For the first time, we provide evidence demonstrating a novel Zn-dependent requirement for PGC-1α expression in macrophages in response to MAC infection [

2,

3,

36]. This observation is consistent with other studies demonstrating the essential role of Zn in maintaining lung immune function. In particular, insufficient Zn levels due to restricted dietary intake before respiratory tract infection result in bacterial evasion of the immune system and worse outcomes [

2,

6,

15,

24,

37,

38,

39,

40].

The acquisition and progression of respiratory tract infections are known to be influenced by chronic Zn deficiency, due to the importance of Zn in a myriad of immune cell functions [

2,

3]. Populations that are most vulnerable to community-acquired pneumonia also exhibit a high incidence of Zn deficiency [

41,

42,

43] , which is estimated to impact approximately 2 billion people worldwide, including approximately 20-30% of the U.S. population [

44]. Consistent with this, others have reported that dietary Zn deficiency increases susceptibility to gastrointestinal tract infections [

45] and pneumonia [

46,

47] , whereas the incidence of pneumonia and other infections is decreased with Zn supplementation [

48,

49,

50].

Mice fed Zn-deficient diets were significantly more susceptible to

Streptococcus pneumoniae infection than their Zn-sufficient counterparts, exhibiting a higher bacterial burden, elevated inflammatory cytokine production, and a drastic decrease in survival [

40].

Acinetobacter baumannii is a Gram-negative bacterium that is frequently linked to respiratory infections during intubation, resulting in ventilator-associated pneumonia [

51]. Zinc deficiency also influenced the progression of

A. baumannii in vivo in a mouse model, with mice fed a Zn-deficient diet exhibiting a significant bacterial burden in lung tissue and BAL fluid compared to Zn-replete mice [

51]. In our previous study investigating infection with

S. pneumoniae we utilized a novel

Zip8 KO mouse to determine its effect on immune cell function against infection. Despite being maintained on a sufficient Zn diet, ZIP8 loss in myeloid cells resulted in decreased acquisition of intracellular Zn that also resulted in increased bacterial burden in the lung, bacterial dissemination into other tissues, increased inflammation and collateral tissue damage, and increased mortality, similar to findings associated with inadequate dietary intake [

15]. This has clinical relevance, as human genome-wide association (GWAS) studies revealed that a frequently occurring defective ZIP8 variant allele (rs13107325; Ala391Thr risk allele) is highly associated with inflammation-based diseases [

52,

53] and bacterial infections [

54]. In fact, a comprehensive review of human GWAS studies revealed that the SLC39A8 variant allele is in the top ten of all variant alleles associated with human disease [

53]. Collectively, these studies highlight the essential requirement for Zn and its bioredistribution in response to bacterial invasion in order to mount an effective yet balanced host innate immune response [

55]. Our studies are the first to show the importance of zinc deficiency and supplementation on macrophage function in MAC infection.

MAC is ubiquitously present and found in water sources and soil and can be pathogenic in patients with compromised immune systems and chronic lung diseases, including cystic fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and bronchiectasis [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. MAC infections typically arise from exposure to environmental niches in the water and soil, whereas person-to-person transmission is uncommon [

58]. The increasing number of cases is due in part to the emergence of drug-resistant strains, complicating treatment of an already evasive and difficult-to-treat pathogen. Currently, the standard of care is long-term treatment (12-18 months) with multiple antibiotics, which are often difficult to tolerate. Furthermore, a significant number of patients experience recurrence of infection despite prolonged treatment [

61]. Thus, there is a high demand for alternative treatment modalities, particularly host-directed therapies that can enhance MAC clearance.

Zn, in addition to other transition metal ions, is also utilized by bacteria for growth and metabolic processes, and immune cells have adapted to this shared need for cations between pathogens through a process known as nutritional immunity [

36,

62,

63]. During infection, metal ions can either be sequestered to prevent their use and uptake by pathogens or concentrated in cellular compartments in excess to induce toxicity in the invading microbes [

7,

63]. Within the body, Zn possesses secondary messenger functions involved in immune cell recruitment and differentiation. Phagocytic uptake of microbes by macrophages is influenced by the presence of Zn, with ZIP8 expression being rapidly upregulated in response to pathogens to increase intracellular Zn concentrations [

1,

55]. Zn also influences the activity of other immune cells, with neutrophils exhibiting reduced recruitment, migration, and phagocytosis under conditions of Zn deficiency. Similarly, both mast cells and NK cells utilize Zn to regulate their immune functions, with Zn starvation resulting in deficient immune activity [

11].

Our results show that insufficient intracellular Zn adversely impacts mitochondrial function via reduction in PGC-1α expression in response to MAC. We also reveal that this deficit can be attenuated through Zn supplementation. Instead of supplementing with conventional inorganic Zn salts such as ZnCl2 or ZnSO4, we used a ZinPro® (ZP) formulation that is Zn conjugated to lysine and glutamine, provided in equal amounts. Previously, it has been shown to have superior bioavailability to inorganic Zn via amino acid transporter-coupled uptake. Using FluoZin-3 AM, a cell-permeant intracellular fluorescent Zn indicator, we observed a significantly higher intracellular Zn concentration with ZP compared to ZnCl2 at equivalent molar concentrations.

We provide evidence that the availability of zinc influences PGC-1α expression and sought to determine the mechanism of cellular zinc import. The ZIP family contains 14 members, with variable presence and expression dependent upon tissue location and type. The predominant ZIP in lung tissues is ZIP8, leading us to select it as a potential target influencing PGC-1α expression and related mitochondrial function.

Our previous research investigated the influence of PGC-1α in NTM infections in macrophages, where expression was modulated through treatment with specific activators and inhibitors to determine the effect on macrophage antibacterial activity in nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) infections [

21]. PGC-1α is a transcription factor and master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, influencing the creation and turnover of mitochondria. Functioning in concert with PGC-1α, mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) is responsible for maintenance and synthesis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), influencing the activity and health of mitochondria. Within the scope of immunity, mitochondrial function drives immune cell activity and function through energy production and metabolism, in addition to important cellular signaling activities. The process of pathogen clearance that includes initial recognition, phagocytic uptake, and eventual lysosomal degradation requires a high energetic demand and metabolic input. Thus, mitochondria are indispensable for protection against bacteria and other pathogens. Revealing that PGC-1α is reliant upon Zn for proper expression and activity provides a new paradigm that involves dietary intake, or lack thereof, and proper biodistribution, via improved formulation and/or ZIP-mediated transport and immunometabolism, resulting in effective clearance of MAC by macrophages.

Our study shows that infection with MAC significantly induces mitochondrial ROS production, which perpetuates mitochondrial damage, compromising macrophage function. In accordance with this, MAC-infected cells exhibited decreased MMP and physical disruption and loss of integrity of the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), which is required for ATP production. Upon damage to the IMM, the release of ROS and mtDNA triggers mitochondrial-mediated inflammatory signaling, inducing morphological changes that, if unaddressed, lead to cell death. In this study, we reveal that the deleterious effect of MAC upon macrophages was heightened by dietary-induced and genetically-induced Zn deficiency in vitro. Importantly, Zn supplementation with a more bioavailable Zn formulation (ZP) attenuated mitochondrial damage and restored macrophage antibacterial function.

These studies are the first to highlight the vital role of Zn in maintaining mitochondrial health in response to MAC infection in macrophages and demonstrate its beneficial impact on PGC-1α. To determine whether Zn impacts PGC-1α-mediated mitochondrial function, we modified culture conditions to emulate dietary-induced Zn deficiency and genetically induced Zn deficiency (ZIP8 loss), and with both conditions also supplemented Zn, then evaluated the impact on mitochondrial function and antibacterial activity. Our results consistently revealed an indispensable role of Zn in macrophage function and their ability to eradicate MAC. As this invasive species continues to evolve new mechanisms to evade host defense, we need to aggressively pursue novel yet tractable treatments to succeed in this pathogenic arms race. Host-directed therapies designed to enhance natural immune cell function are widely becoming an integral focus in the future of antibacterial treatments. Based on our findings, screening approaches that identify Zn insufficiency due to dietary genetic and genetic defects have the potential to foster tolerable preventive and supplemental treatment strategies that more effectively resolve pulmonary MAC infection.

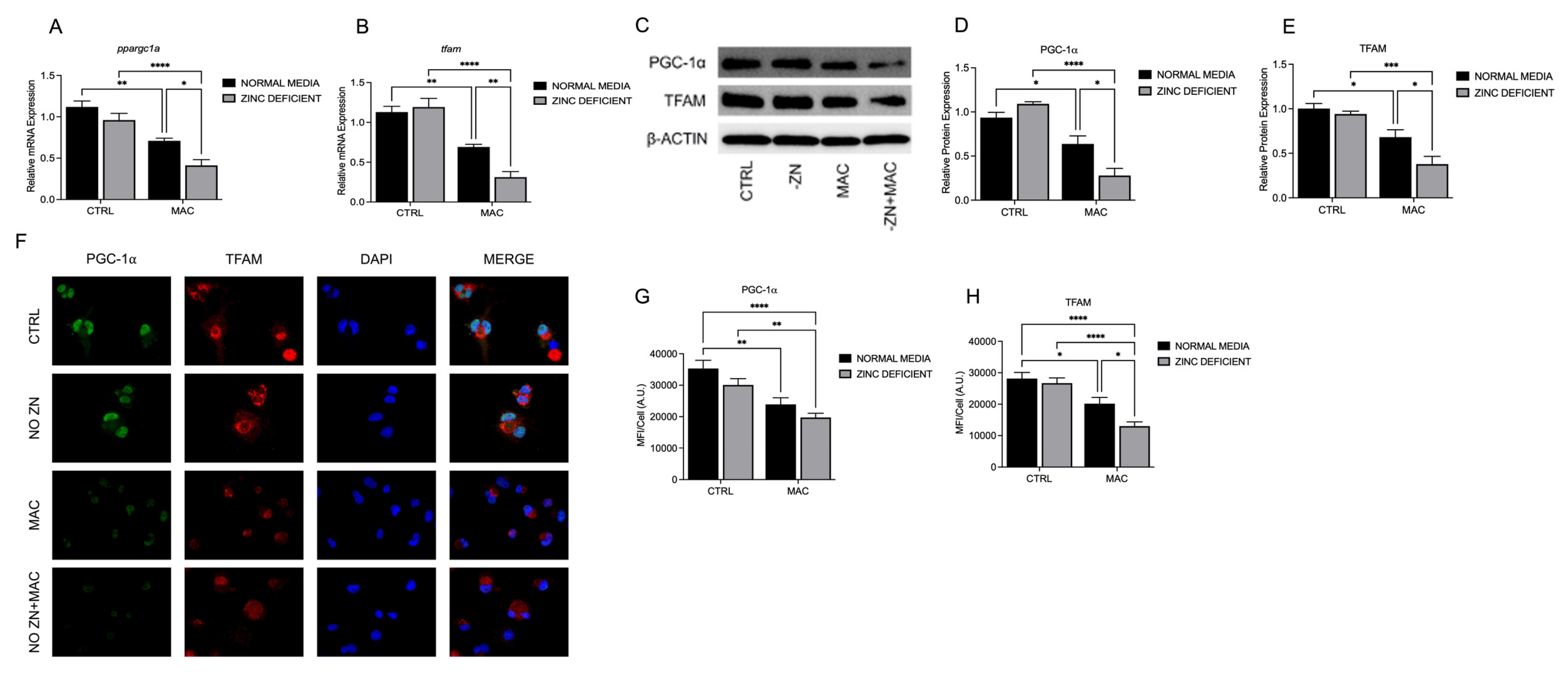

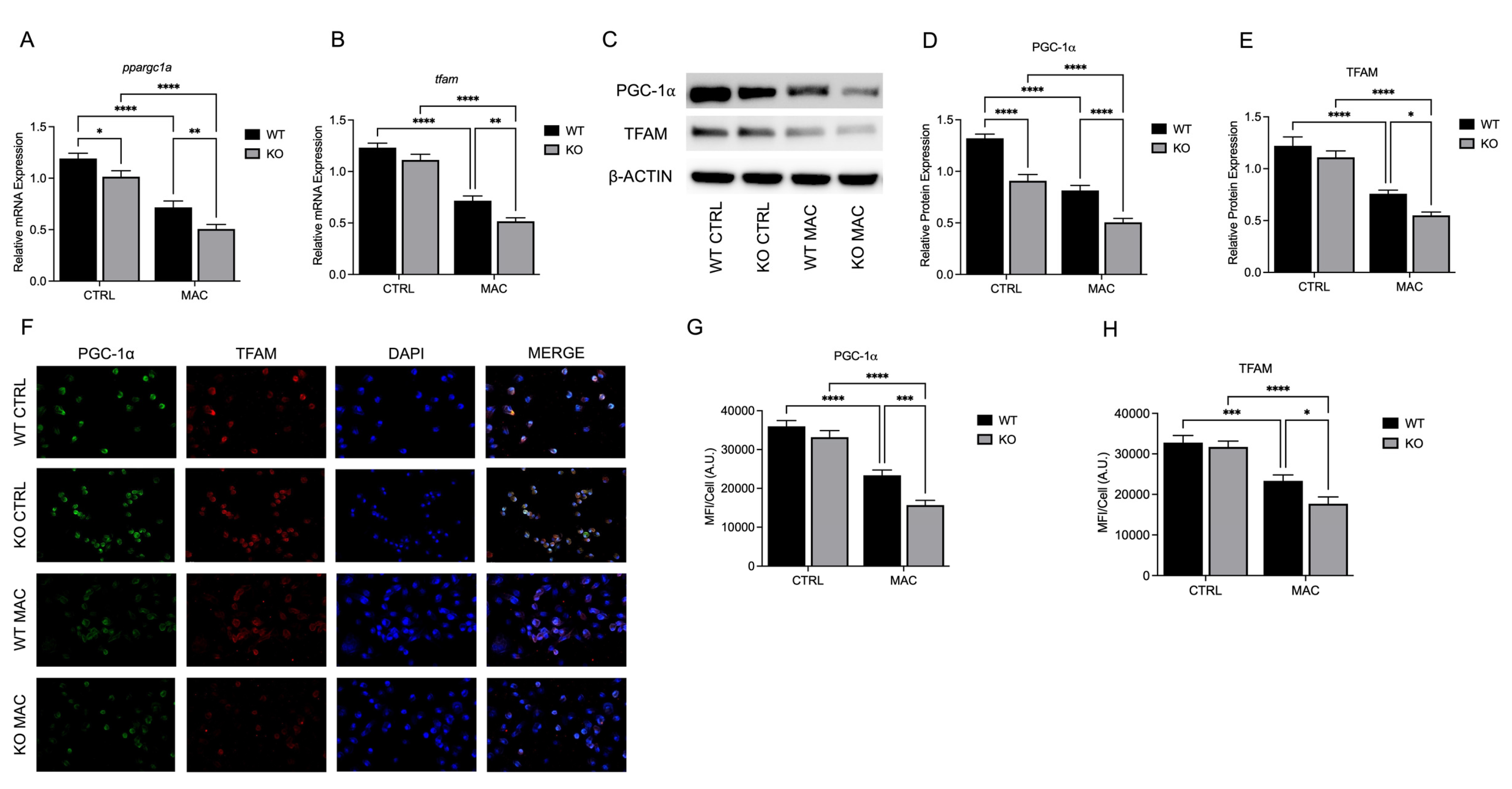

Figure 1.

Zinc deficiency during MAC infection reduces expression of key transcriptional regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis: U937 macrophages were cultured and introduced to zinc-deficient conditions for 48 hours prior to MAC infection (MOI 1) for 24 hours. PCR results for mRNA expression of ppargc1a (A) and tfam (B). Western blot results for PGC-1α (D) and TFAM (E), and representative blot images (C). ICC results for protein expression of PGC-1α (G), TFAM (H), and representative confocal images (F). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

Figure 1.

Zinc deficiency during MAC infection reduces expression of key transcriptional regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis: U937 macrophages were cultured and introduced to zinc-deficient conditions for 48 hours prior to MAC infection (MOI 1) for 24 hours. PCR results for mRNA expression of ppargc1a (A) and tfam (B). Western blot results for PGC-1α (D) and TFAM (E), and representative blot images (C). ICC results for protein expression of PGC-1α (G), TFAM (H), and representative confocal images (F). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

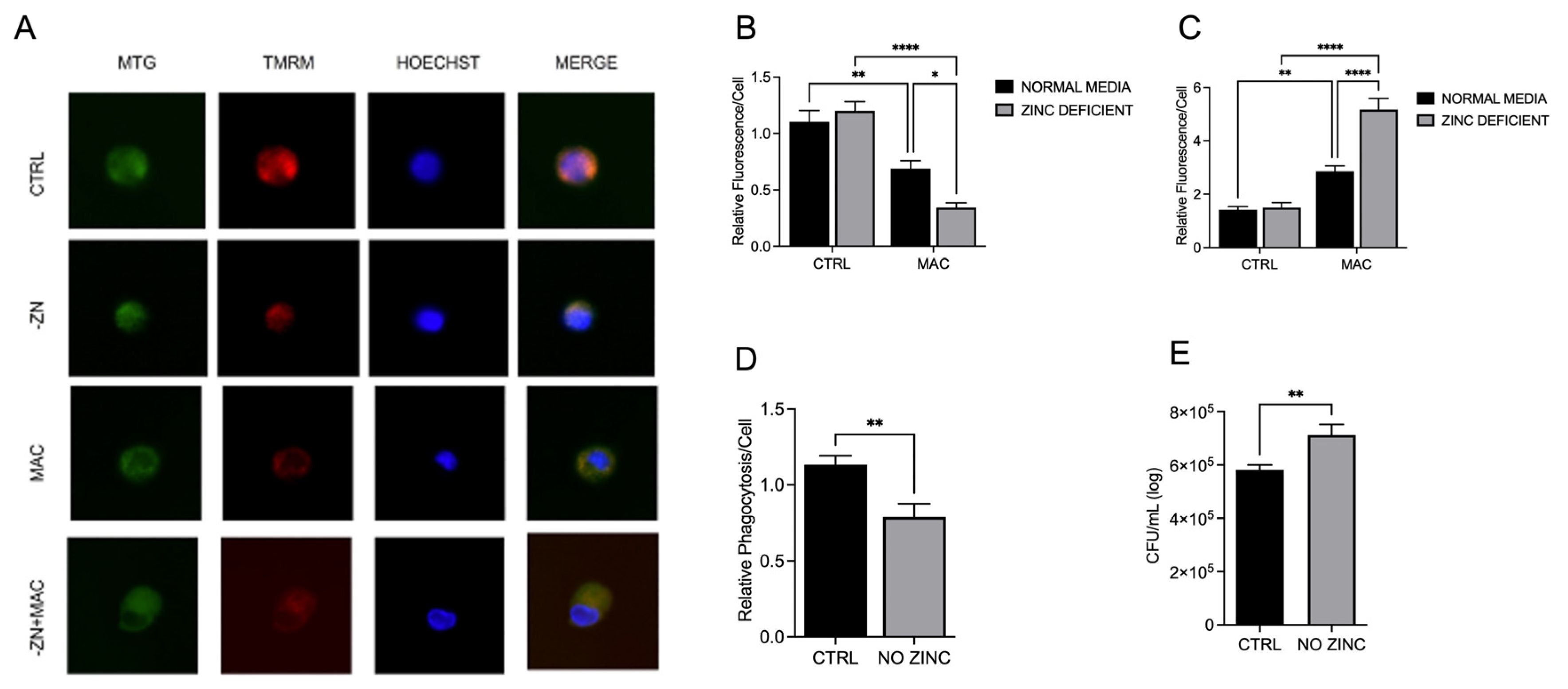

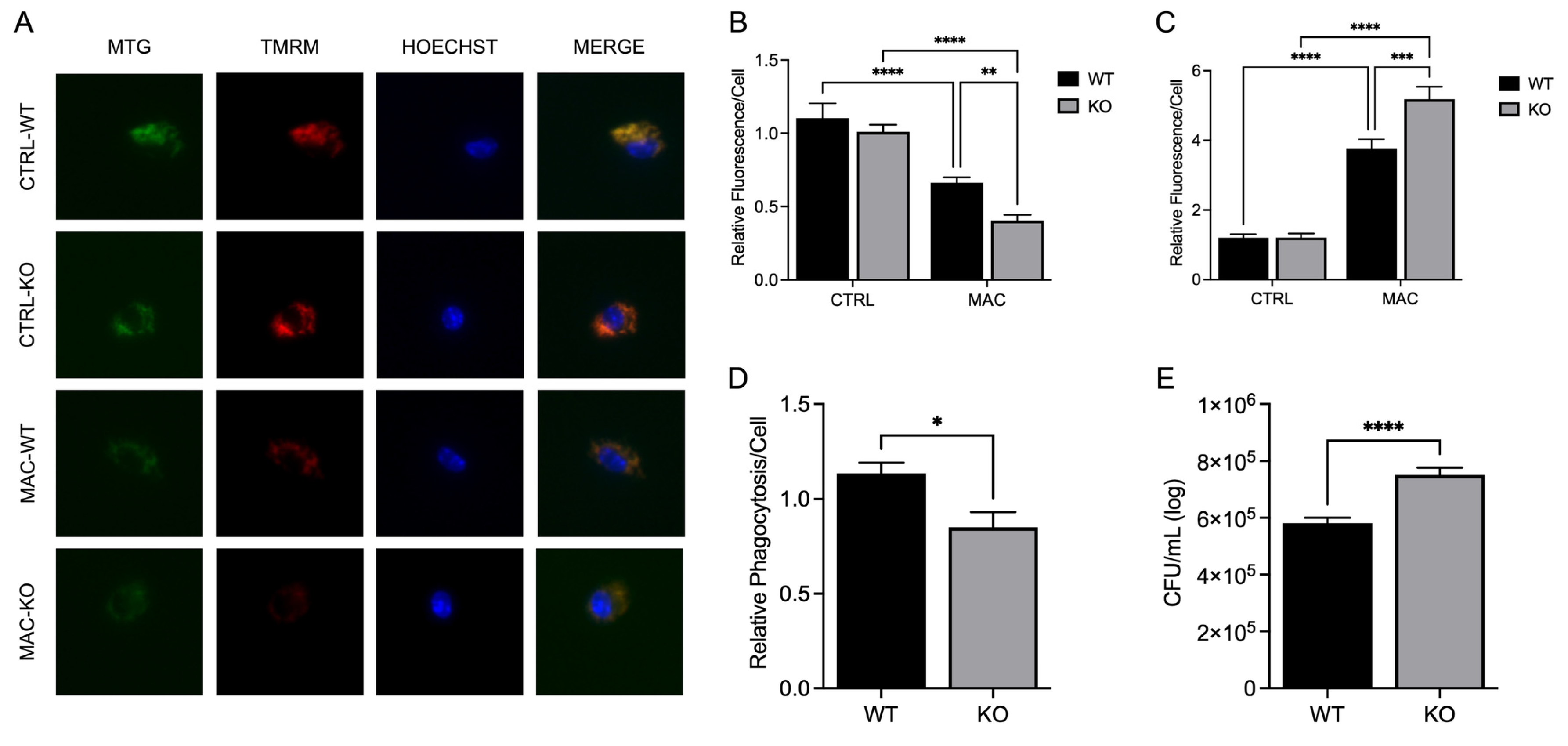

Figure 2.

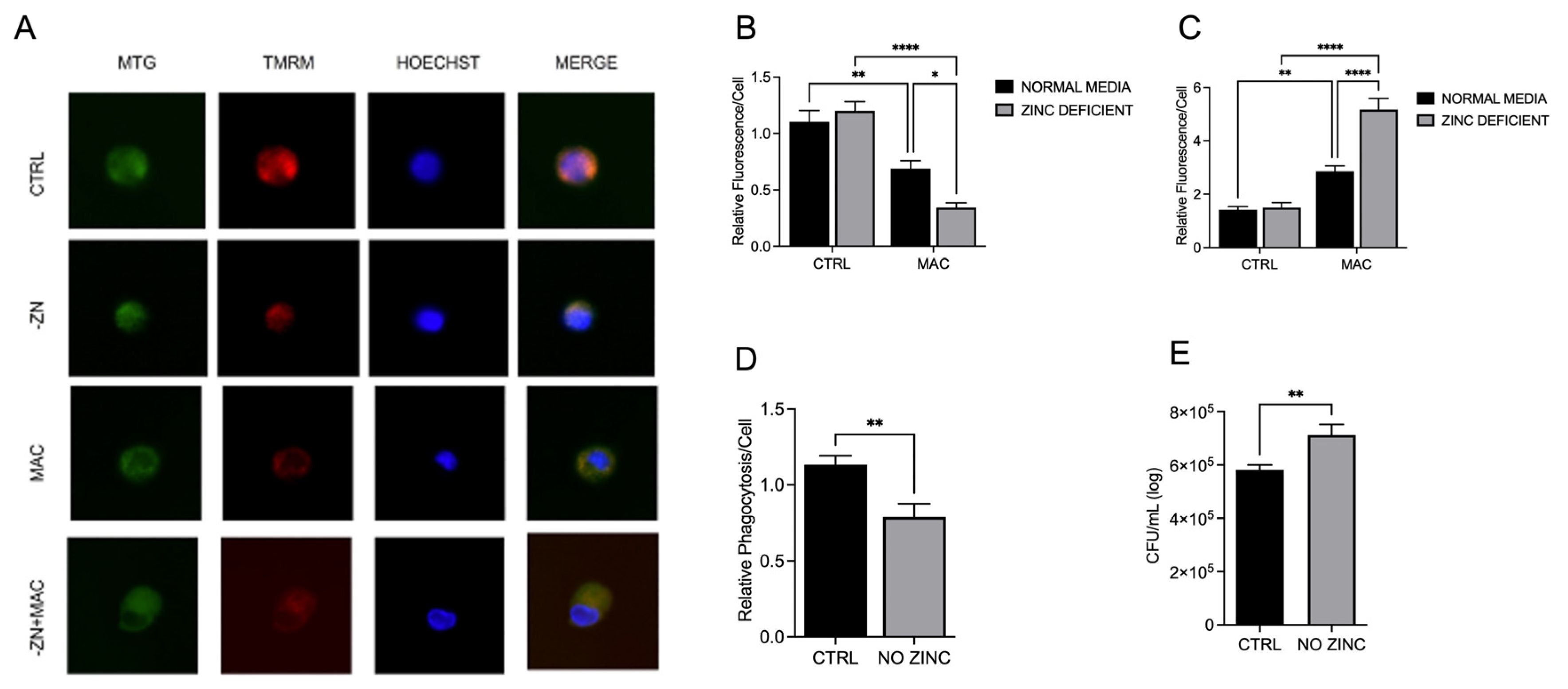

Zinc deficiency during MAC infection damages mitochondria through reduction of ΔΨm and increased mitochondrial ROS production and reduces macrophage phagocytosis and bacterial killing: U937 macrophages were cultured and introduced to zinc-deficient conditions for 48 hours prior to MAC infection (MOI 1) for 24 hours prior to all analyses. Cells were stained with MitoTracker Green, TMRM, and Hoechst to evaluate mitochondrial membrane integrity, and presented as relative fluorescence of TMRM/MTG per Hoechst-positive cell (A, B). Mitochondria superoxide production was evaluated through staining with MitoSOX and measuring fluorescence expression within cells (C). Phagocytic uptake was determined through incubating cells with fluorescent BioParticles for 2 hours and evaluating fluorescence expression to determine cellular uptake (D). Bacterial killing was evaluated through CFU counting on 7H9 agar plates (E). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

Figure 2.

Zinc deficiency during MAC infection damages mitochondria through reduction of ΔΨm and increased mitochondrial ROS production and reduces macrophage phagocytosis and bacterial killing: U937 macrophages were cultured and introduced to zinc-deficient conditions for 48 hours prior to MAC infection (MOI 1) for 24 hours prior to all analyses. Cells were stained with MitoTracker Green, TMRM, and Hoechst to evaluate mitochondrial membrane integrity, and presented as relative fluorescence of TMRM/MTG per Hoechst-positive cell (A, B). Mitochondria superoxide production was evaluated through staining with MitoSOX and measuring fluorescence expression within cells (C). Phagocytic uptake was determined through incubating cells with fluorescent BioParticles for 2 hours and evaluating fluorescence expression to determine cellular uptake (D). Bacterial killing was evaluated through CFU counting on 7H9 agar plates (E). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

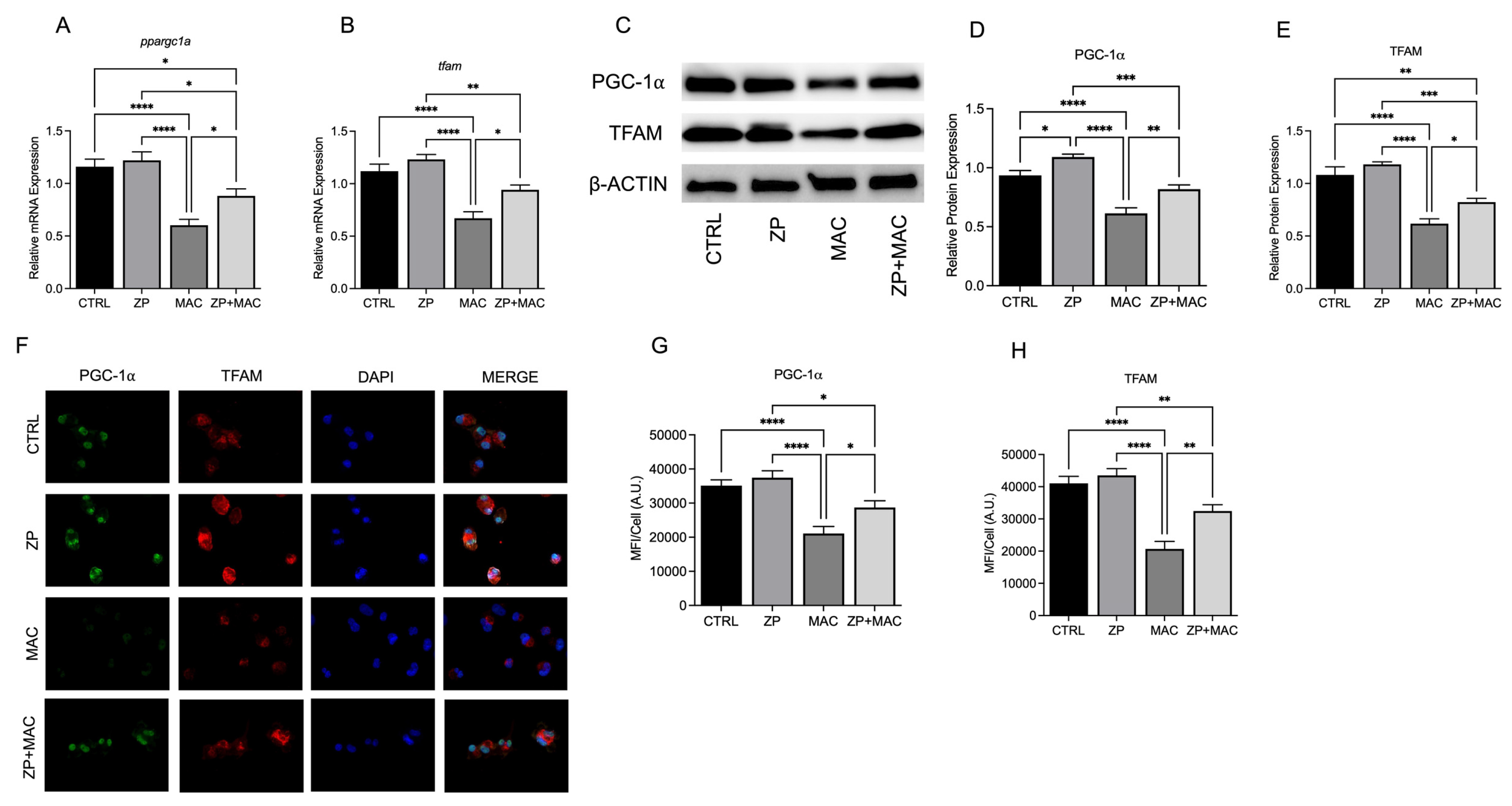

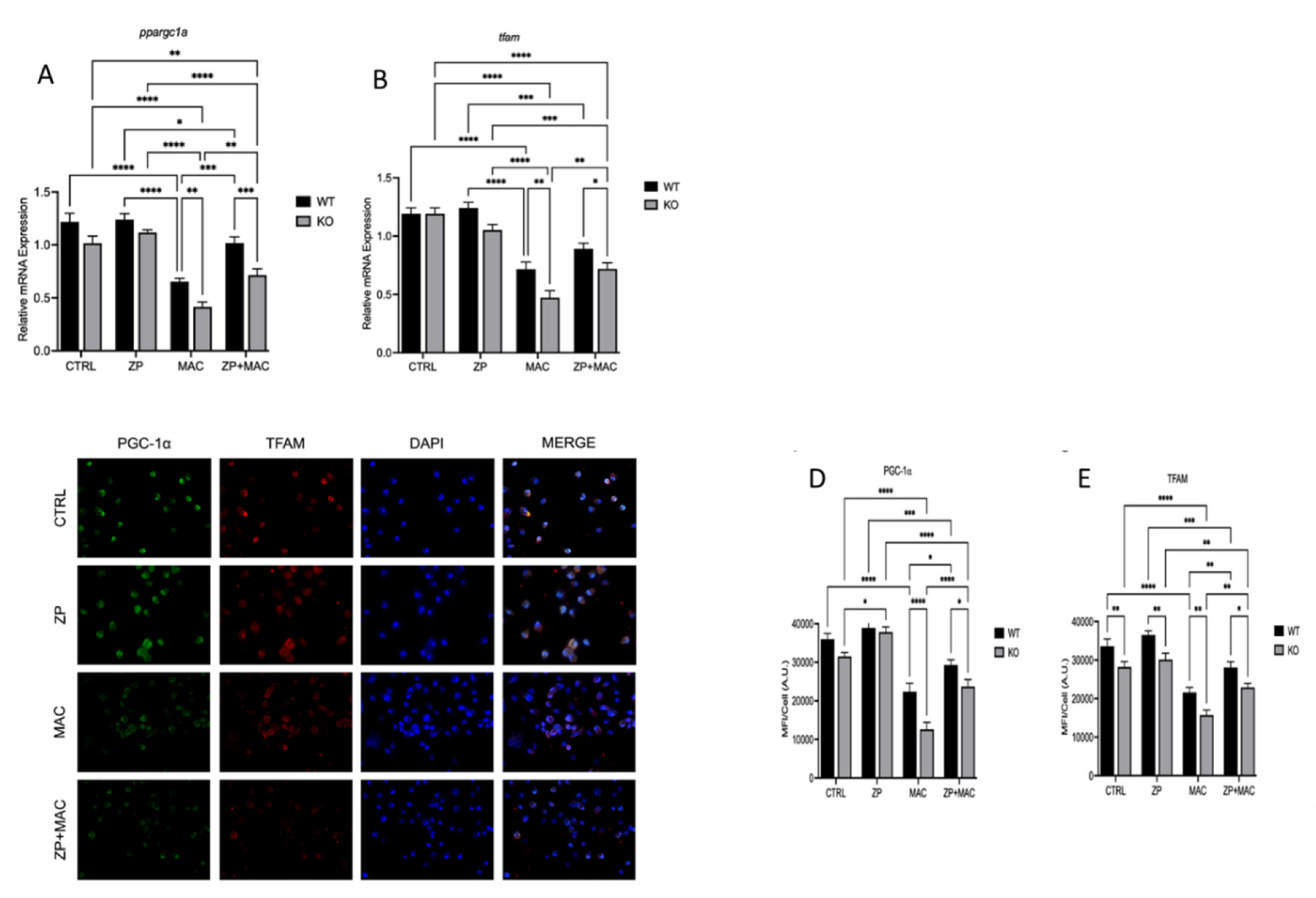

Figure 3.

ZP treatment rescues expression of mitochondrial PGC-1α and related cofactors during MAC infection: U937 macrophages were cultured and treated with ZP [50 µM] for 48 hours prior to infection with MAC (MOI 1) for 4 hours prior to all analyses. PCR results for mRNA expression of ppargc1a (A) and tfam (B). Western blot results for PGC-1α (D) and TFAM (E), and representative blot images (C). ICC results for protein expression of PGC-1α (G), TFAM (H), and representative confocal images (F). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

Figure 3.

ZP treatment rescues expression of mitochondrial PGC-1α and related cofactors during MAC infection: U937 macrophages were cultured and treated with ZP [50 µM] for 48 hours prior to infection with MAC (MOI 1) for 4 hours prior to all analyses. PCR results for mRNA expression of ppargc1a (A) and tfam (B). Western blot results for PGC-1α (D) and TFAM (E), and representative blot images (C). ICC results for protein expression of PGC-1α (G), TFAM (H), and representative confocal images (F). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

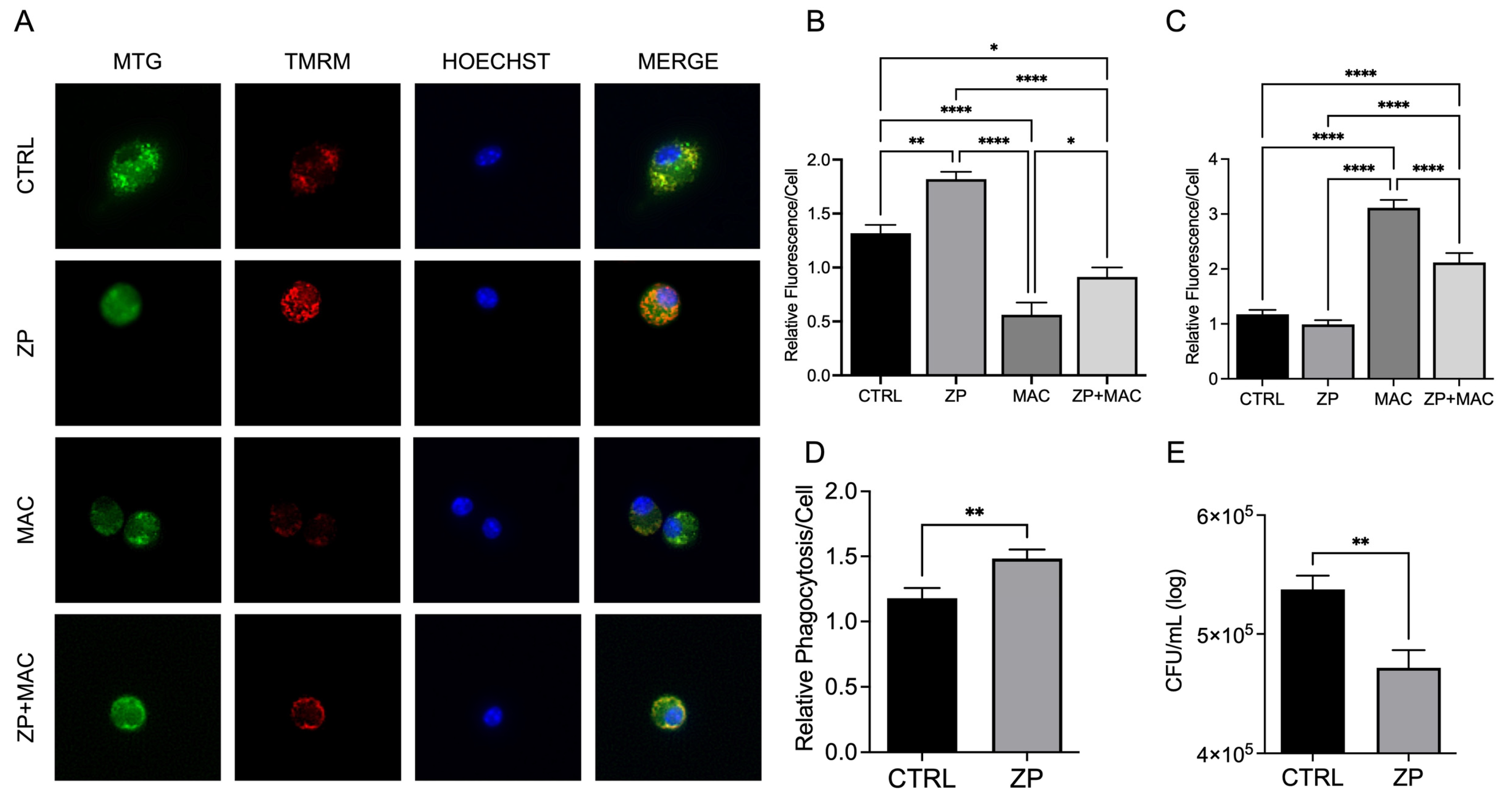

Figure 4.

Treatment with ZP aids in maintaining ΔΨm during MAC infection, reduces mitochondrial ROS production, and elevates macrophage antibacterial activity: U937 macrophages were cultured and treated with ZP [50 µM] for 48 hours prior to infection with MAC (MOI 1) for 24 hours prior to all analyses. Cells were stained with MitoTracker Green, TMRM, and Hoechst to evaluate mitochondrial membrane integrity, and presented as relative fluorescence of TMRM/MTG per Hoechst-positive cell (A, B). Mitochondria superoxide production was evaluated through staining with MitoSOX and measuring fluorescence expression within cells (C). Phagocytic uptake was determined through incubating cells with fluorescent BioParticles for 2 hours and evaluating fluorescence expression to determine cellular uptake (D). Bacterial killing was evaluated through CFU counting on 7H9 agar plates (E). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

Figure 4.

Treatment with ZP aids in maintaining ΔΨm during MAC infection, reduces mitochondrial ROS production, and elevates macrophage antibacterial activity: U937 macrophages were cultured and treated with ZP [50 µM] for 48 hours prior to infection with MAC (MOI 1) for 24 hours prior to all analyses. Cells were stained with MitoTracker Green, TMRM, and Hoechst to evaluate mitochondrial membrane integrity, and presented as relative fluorescence of TMRM/MTG per Hoechst-positive cell (A, B). Mitochondria superoxide production was evaluated through staining with MitoSOX and measuring fluorescence expression within cells (C). Phagocytic uptake was determined through incubating cells with fluorescent BioParticles for 2 hours and evaluating fluorescence expression to determine cellular uptake (D). Bacterial killing was evaluated through CFU counting on 7H9 agar plates (E). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

Figure 5.

ZIP8-KO reduces expression of key transcriptional regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis in BMDMs: BMDMs from both WT and Zip8-KO mice were cultured in normal media and infected with MAC (MOI 1) for 24 hours prior to all analyses. PCR results for mRNA expression of ppargc1a (A) and tfam (B). Western blot results for PGC-1α (D) and TFAM (E), and representative blot images (C). ICC results for protein expression of PGC-1α (G), TFAM (H), and representative confocal images (F). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

Figure 5.

ZIP8-KO reduces expression of key transcriptional regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis in BMDMs: BMDMs from both WT and Zip8-KO mice were cultured in normal media and infected with MAC (MOI 1) for 24 hours prior to all analyses. PCR results for mRNA expression of ppargc1a (A) and tfam (B). Western blot results for PGC-1α (D) and TFAM (E), and representative blot images (C). ICC results for protein expression of PGC-1α (G), TFAM (H), and representative confocal images (F). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

Figure 6.

ZIP8 KO BMDMs exhibit reduced ΔΨm, increased mitochondrial ROS production, and reduced macrophage antibacterial activity under zinc deficiency during MAC infection: BMDMs from both WT and Zip8-KO mice were cultured in normal media and infected with MAC (MOI 1) for 4 hours prior to all analyses. Cells were stained with MitoTracker Green, TMRM, and Hoechst to evaluate mitochondrial membrane integrity, and presented as relative fluorescence of TMRM/MTG per Hoechst-positive cell (A, B). Mitochondria superoxide production was evaluated through staining with MitoSOX and measuring fluorescence expression within cells (C). Phagocytic uptake was determined through incubating cells with fluorescent BioParticles for 2 hours and evaluating fluorescence expression to determine cellular uptake (D). Bacterial killing was evaluated through CFU counting on 7H9 agar plates (E). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

Figure 6.

ZIP8 KO BMDMs exhibit reduced ΔΨm, increased mitochondrial ROS production, and reduced macrophage antibacterial activity under zinc deficiency during MAC infection: BMDMs from both WT and Zip8-KO mice were cultured in normal media and infected with MAC (MOI 1) for 4 hours prior to all analyses. Cells were stained with MitoTracker Green, TMRM, and Hoechst to evaluate mitochondrial membrane integrity, and presented as relative fluorescence of TMRM/MTG per Hoechst-positive cell (A, B). Mitochondria superoxide production was evaluated through staining with MitoSOX and measuring fluorescence expression within cells (C). Phagocytic uptake was determined through incubating cells with fluorescent BioParticles for 2 hours and evaluating fluorescence expression to determine cellular uptake (D). Bacterial killing was evaluated through CFU counting on 7H9 agar plates (E). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

Figure 7.

ZP treatment rescues ZIP8 KO BMDM expression of mitochondrial PGC-1α and related cofactors during MAC infection: BMDM from both WT and Zip8-KO mice were cultured in normal media and treated with ZP [50 µM] for 48 hours prior to infection with MAC (MOI 1) for 4 hours prior to all analyses. PCR results for mRNA expression of ppargc1a (A) and tfam (B). ICC results for protein expression of PGC-1α (D), TFAM (E), and representative confocal images (C). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

Figure 7.

ZP treatment rescues ZIP8 KO BMDM expression of mitochondrial PGC-1α and related cofactors during MAC infection: BMDM from both WT and Zip8-KO mice were cultured in normal media and treated with ZP [50 µM] for 48 hours prior to infection with MAC (MOI 1) for 4 hours prior to all analyses. PCR results for mRNA expression of ppargc1a (A) and tfam (B). ICC results for protein expression of PGC-1α (D), TFAM (E), and representative confocal images (C). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

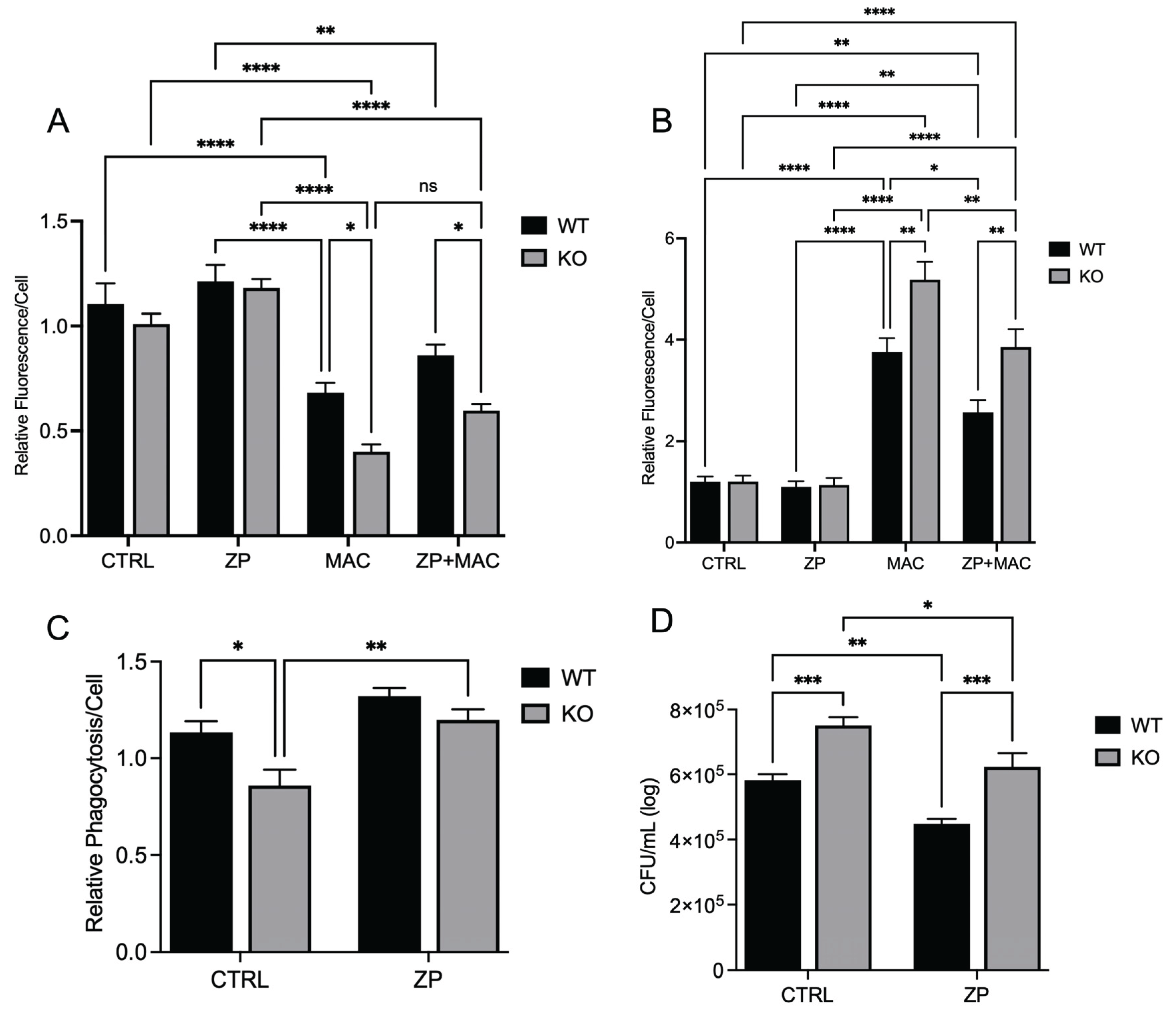

Figure 8.

ZP attenuates ZIP8 KO BMDM mitochondrial damage and deficits in macrophage activity during MAC infection: BMDM from both WT and Zip8-KO mice were cultured in normal media and treated with ZP [50 µM] for 48 hours prior to infection with MAC (MOI 1) for 4 hours prior to all analyses. Cells were stained with MitoTracker Green, TMRM, and Hoechst to evaluate mitochondrial membrane integrity, and presented as relative fluorescence of TMRM/MTG per Hoechst-positive cell (A). Mitochondria superoxide production was evaluated through staining with MitoSOX and measuring fluorescence expression within cells (B). Phagocytic uptake was determined through incubating cells with fluorescent BioParticles for 2 hours and evaluating fluorescence expression to determine cellular uptake (C). Bacterial killing was evaluated through CFU counting on 7H9 agar plates (D). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.

Figure 8.

ZP attenuates ZIP8 KO BMDM mitochondrial damage and deficits in macrophage activity during MAC infection: BMDM from both WT and Zip8-KO mice were cultured in normal media and treated with ZP [50 µM] for 48 hours prior to infection with MAC (MOI 1) for 4 hours prior to all analyses. Cells were stained with MitoTracker Green, TMRM, and Hoechst to evaluate mitochondrial membrane integrity, and presented as relative fluorescence of TMRM/MTG per Hoechst-positive cell (A). Mitochondria superoxide production was evaluated through staining with MitoSOX and measuring fluorescence expression within cells (B). Phagocytic uptake was determined through incubating cells with fluorescent BioParticles for 2 hours and evaluating fluorescence expression to determine cellular uptake (C). Bacterial killing was evaluated through CFU counting on 7H9 agar plates (D). Results are averages of experiments performed in triplicate with SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001.