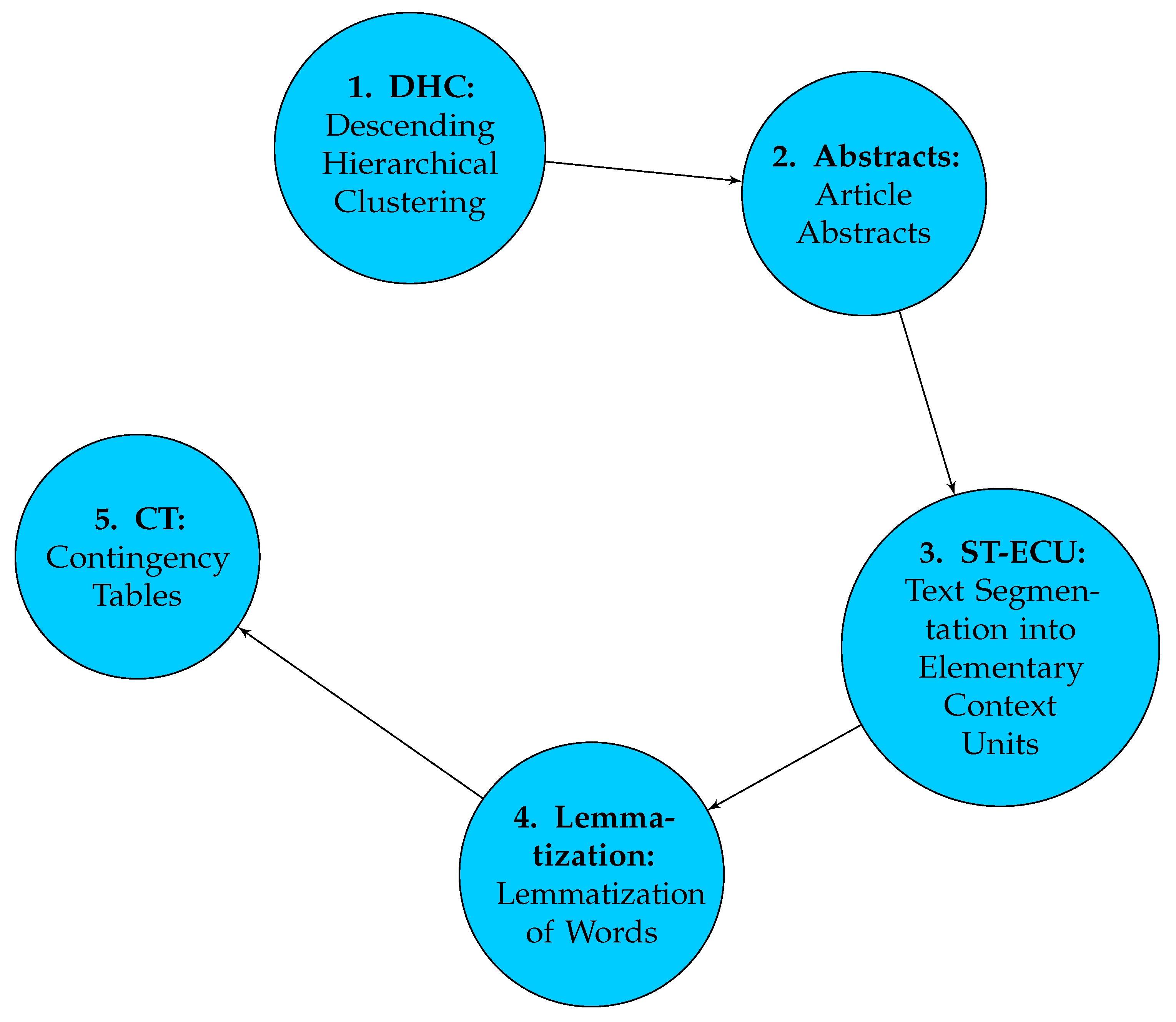

4.2. Results of Text Mining

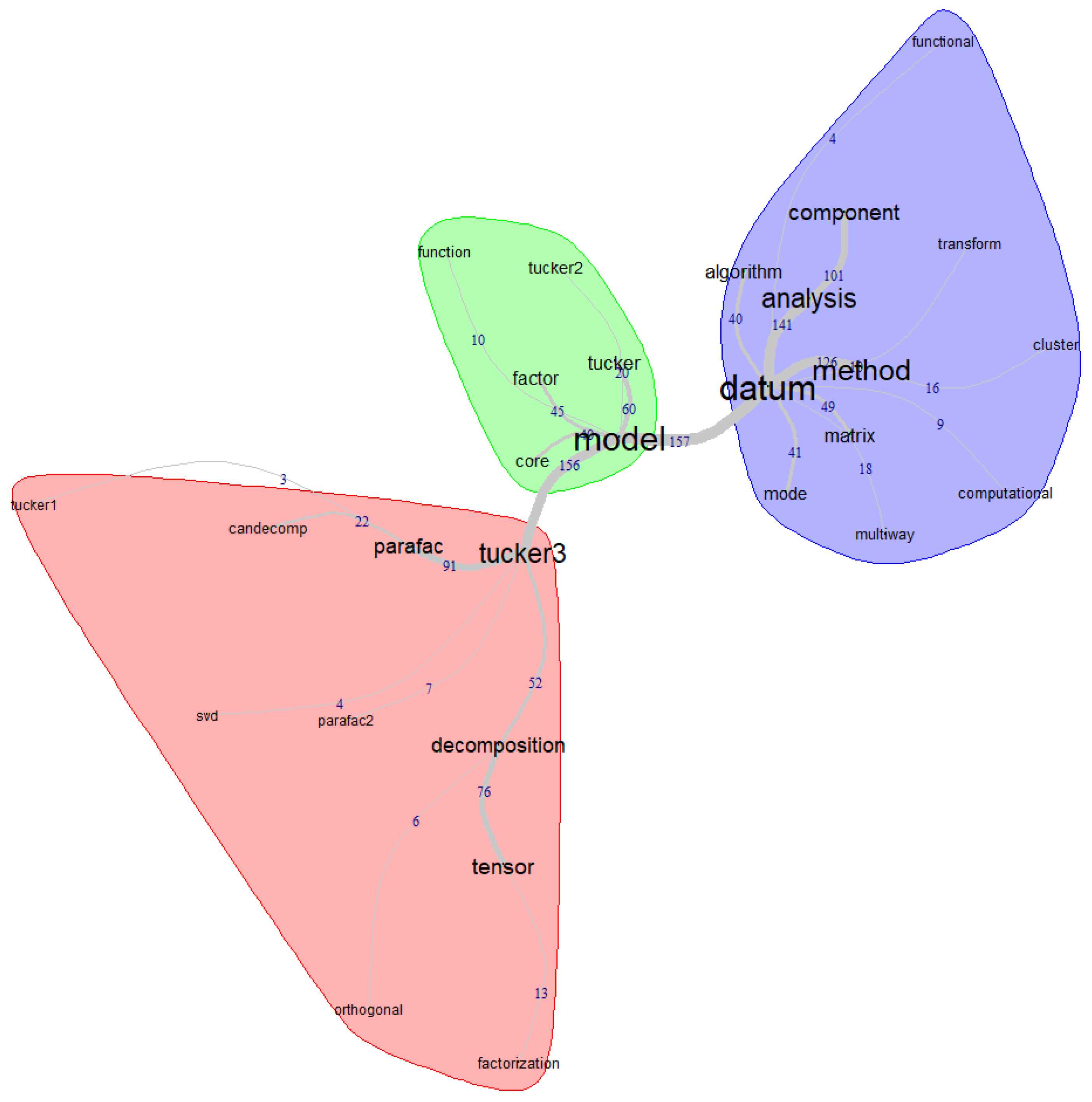

Once the textual corpus under study was loaded into the IraMuteq software, we present the results obtained, starting with the similarity analysis, based on graph theory. A graph, in this context, represents a set of vertices (which correspond to words or forms) and edges (which represent the relationships between them). The purpose of this analysis is to investigate the proximity and relationships between the elements of a set, optimizing the simplification of the number of connections until a

connected acyclic graph is obtained. This is characterized by being a closed path in which no vertex is repeated, except for the first one, which acts as both the start and end of the path, as illustrated in

Figure 5.

As can be seen, to obtain the graph shown, some adjustments were made in the IraMuteq software, considering words that, in addition to having high frequencies, are connected to the topic in question, the Tucker models. In the similarity graph, three clusters are observed, represented by different colors. Within these clusters, there are larger words (called the maximum tree of each cluster that interconnects them: "model", "datum," and "tucker3"). At the same time, within each cluster, these higher-frequency words are connected to other words that had strong connections in the textual corpus.

In the central cluster, we have the term "model," which acts as the central or most prominent node. Within this cluster, some terms are strongly connected, such as: "factor," "tucker," "tucker2," "function," and "core"; this suggests the presence of factorial analysis and mathematical functions for Tucker models, particularly Tucker-2, where the core tensor, also known as the core matrix, is involved.

In the left cluster, we identified the term "tucker3," which acts as the maximum tree and is strongly associated with other words such as: "parafac," "parafac2," "decomposition," "sdv," "tensor," "tucker1," "candecomp," "orthogonal," and "factorization." For example, "parafac" and "parafac2" refer to variants or extensions of the PARAFAC model, while "decomposition" indicates tensor decomposition. On the other hand, "Candecomp" refers to CANDECOMP/PARAFAC decomposition and also indicates the orthogonality property associated with certain decomposition methods.

The third cluster, located on the right, has "datum" as the maximum tree, which is connected to a series of keywords such as: "method," "analysis," "component," "transform," "functional," "cluster," "multiway," "computational," "matrix," "mode," and "algorithm." This structure suggests a variety of related concepts and terms. For example, it indicates different approaches or methods for data analysis, which are related to decomposing data into simpler components and data transformation for various analysis purposes, including cluster analysis.

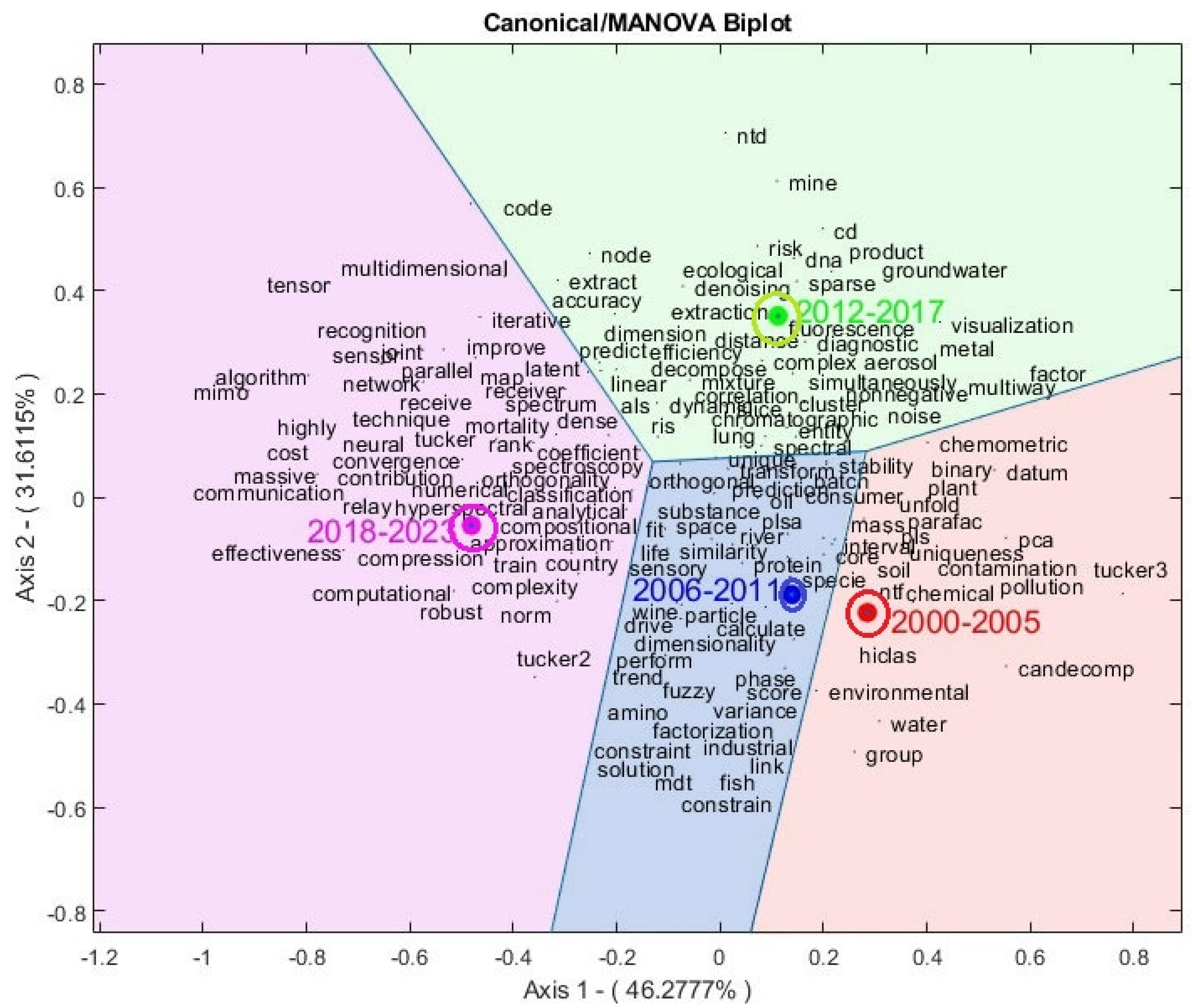

4.4. Results of the MANOVA-Biplot

Once the groups corresponding to the publication periods of the articles were defined, in our case, we have 4 groups, each spanning 6 years according to

Table 3, chosen to maintain homogeneity concerning the number of years analyzed. We then proceeded to load the database called

data into the

MultBiplot software [

82] version

18.0312, a tool developed in the Department of Statistics at the University of Salamanca, widely used in multivariate data analysis. In this context, the software allows for the import of data from Excel and the definition of the group variable as nominal, along with the specification of the 4 categories corresponding to that variable. Subsequently, we performed the one-way MANOVA-Biplot analysis.

After running the analysis in the software, we made various modifications to adjust and improve data visualization, thus obtaining a more accurate representation, as shown in

Figure 6. In this regard, advanced visualization techniques were implemented, including Voronoi regions and confidence circles. These regions, named after the Russian mathematician Georgy Voronoi, are used to delimit areas on a plane based on proximity to a given set of points, allowing for better interpretation and understanding of the groups identified in the analysis [

83]. On the other hand, the confidence circles shown highlight the significant differences between the means since they do not intersect.

Table 4 details how the main dimensions capture variability in the data. The

first dimension or

first canonical variable has an eigenvalue of

20.49 and an explained variance of

46.28%, meaning it explains

46.28% of the variability between groups. This dominant factor captures nearly half of the variability between groups, while the

second component explains

31.61%; in other words, the first two canonical variables explain

77.89% of the total variability, suggesting a deep understanding of the data structure. Additionally, the

p-values associated with the canonical variables are nearly zero, indicating high statistical significance and confirming the robustness of the model. This detailed evaluation provides a comprehensive view of the underlying relationships between the two sets of variables, thus supporting the validity and reliability of the analysis.

The results in

Table 5,

Quality of representation of group means, show how the different year groups are represented on the axes of the canonical biplot analysis. Each group corresponds to a specific period (e.g., "2000-2005", "2006-2011", etc.), and the values in the "Axis 1" and "Axis 2" columns represent the coordinates of that group on the two main axes of the Biplot; additionally, we multiplied their original values by 1000 and added an accumulated quality column to facilitate interpretation.

Groups 3 and 4, i.e., the years 2012-2017 and 2018-2023, present the highest qualities of representation on the first two factorial axes (1000 and 988, respectively), followed by group 1 (549) and finally group 2 (435) with relatively low quality compared to the other groups. This suggests considering that this group will be better represented on axes 2 and 3. However, in general terms, we have a very good quality representation of the canonical groups on the first two axes.

Next, the graph of the Canonical Biplot analysis is presented, visualizing the relationships between groups corresponding to different year periods. Each group is represented in the Biplot by a set of coordinates on the main axes. This analysis allows us to observe the trends and patterns in the evolution of keywords over time concerning Tucker models.

Focusing on the result of the MANOVA-Biplot analysis obtained in

Figure 6, four regions representing the publication periods of the articles are identified: "2000-2005", "2006-2011", "2012-2017", and "2018-2023". A notable feature is the significant increase in the number of keywords as we move forward in time. This suggests an expansion in the scope and focus of research, with diversification in the thematic areas addressed concerning Tucker models.

It is also observed that there are many similarities between the groups of articles from the periods 2000-2005 and 2006-2011 (groups 1 and 2) since they are very close on the graph; on the other hand, groups 3 and 4 are far from the others, suggesting that the topics covered in those periods are significantly different but within the scope of Tucker models.

In the period "2000-2005," the inclusion of the terms "hiclas" and "binary" suggests a focus on data organization and hierarchy, which corresponds to hierarchical classes of binary data through Tucker models. This indicates the exploration of complex structures and relationships between variables. The appearance of "Candecomp" refers to CANDECOMP (CANonical DECOMPosition); in addition, terms such as "Tucker3," "PCA," and "PARAFAC," which are fundamental techniques in Tucker models, are included. Their inclusion in this period indicates continued interest in researching and developing these techniques in the early years of this millennium, although they are models developed in the last century.

The inclusion of terms such as "pollution," "chemical," "chemometric," "water," and "contamination" suggests a focus on applying Tucker models in contexts related to the assessment and modeling of pollution and water quality. This indicates an interest in analyzing environmental and health-related data during that period.

In group 2, period "2006-2011," the repeated presence of terms such as "dimensionality" and "transform" indicates a concentration on generating and transforming data using Tucker models during this period. These terms suggest a focus on the manipulation and conversion of data into useful and analyzable formats.

The presence of the term "fuzzy" indicates a focus on studying Tucker models with imprecise or fuzzy data. Taken together, these findings suggest an emphasis on innovation and advancement in tensor analysis during this specific period, highlighting the importance of exploring and understanding the complexities of Tucker models to address challenges in various application areas.

During the period 2012-2017, the published articles present a varied focus covering different aspects of the research. There is an interest in updating methods and techniques, such as "sparse." Additionally, the term "cd" suggests an interest in studying Tucker models for compositional data.

There is also an evident focus on data visualization ("visualization") and dimension estimation ("dimension"), which suggests an emphasis on understanding and visually representing information; these terms also suggest the study of the number of components or dimensions to retain for each mode in Tucker models. The presence of terms like "dna," "efficiency," "diagnostic," "fluorescence," "mine," "ecological," and "denoising" indicates a diversity of application areas, ranging from environmental research to molecular biology. These terms reveal multidisciplinary and multifaceted research during this period, covering everything from the refinement of analytical techniques to the application of tensor analysis in various fields of study.

Finally, in the group corresponding to the period "2018-2023," there is a concentration of keywords such as "robust," "highly," "algorithm," "multidimensional," "massive," "network," "numerical," "mimo," and "communication." These keywords reflect a technically and conceptually advanced landscape concerning Tucker models in the most recent period. There is a focus on areas such as advanced algorithms, image processing, computational efficiency, pattern recognition, and neural network applications in communication, among others.

The knowledge development line in Tucker models has evolved from their fundamental development to their application in complex and dynamic problems across various fields. Over the years, a deeper understanding of Tucker models and their integration with other analytical methods has been achieved, leading to significant advances in multidimensional data analysis and understanding patterns and trends over time. Up to this point in the study, we have conducted a traditional, subjective, and superficial interpretation of the scientific contributions of the new millennium within the context of Tucker models. In this sense, it is essential to add an additional layer of information using artificial intelligence.

4.6. ChatGPT 3.5 Results for Textual Analysis of Articles Related to Tucker Models in the Period 2000-2023.

The following results correspond to the year-by-year outputs generated by ChatGPT 3.5 throughout the study period.

Here are the main findings of the articles grouped by year:

Here are the main findings of the articles grouped by year:

2000: Louwerse and Smilde extended the theory of batch process MSPC control charts and developed improved control charts based on Unfold-PCA, PARAFAC, and Tucker3 models. They compared the performance of these charts for different types of faults in batch processes. Timmerman and Kiers proposed the DIFFIT method to indicate the optimal number of components in trilinear principal component analysis (3MPCA). This method outperformed others in simulations by correctly indicating the number of components.

2001: Gurden et al. presented a "grey" model that combines known and unknown information about a chemical system using a Tucker3 model. This was illustrated with data from a batch chemical reaction. Bro et al. highlighted the fundamental differences between PARAFAC and Tucker3 models and proposed a modification of the multilinear partial least squares regression model. Simeonov et al. applied multivariate statistical methods to drinking water data, highlighting water quality in different systems. De Juan and Tauler compared three-dimensional resolution methods of chemical data and suggested that Tucker3 and MCR-ALS are suitable for non-trilinear data. Estienne et al. used the Tucker3 model to extract useful information from a complex EEG dataset, identifying irrelevant sources of variation.

2002: Gemperline et al. used Tucker3 models to analyze multidimensional data from fish caught during spawning, identifying migratory patterns. Amaya and Pacheco described the Tucker3 method for three-way data analysis and its practical application. Lopes and Menezes compared the PARAFAC and Tucker3 models for industrial process control. Smoliński and Walczak developed a strategy to explore contaminated datasets with missing elements using robust PLS and the expectation-maximization algorithm. Pravdova et al. showed how N-way PCA can improve the interpretation of complex data, using Parafac and Tucker3 models.

2003: Huang et al. provided an overview of multi-way methods in image analysis, highlighting the application of PARAFAC and Tucker3 models in image analysis. De Belie et al. investigated sound emission patterns when chewing different types of dry and crunchy snacks, using multivariate analysis to distinguish between snack groups. Bro and Kiers proposed a new diagnostic called CORCONDIA to determine the appropriate number of components in multiway models. Kiers and Der Kinderen presented an alternative procedure for choosing the number of components in Tucker3 analysis, which was faster than existing methods. Ceulemans and Van Mechelen presented uniqueness theorems for hierarchical class models, comparing them to N-way principal component models.

2004: Muti and Bourennane developed an optimal method for lower-rank tensor approximation applied to multidimensional signal processing. Ceulemans, Van Mechelen, and Leenen introduced the Tucker3-HICLAS model for three-way trinary data, with application to hostility data. Flåten et al. proposed a method to assess environmental stress on the seabed using Tucker3 analysis on data collected in industrial pollution studies. Stanimirova et al. compared the STATIS method with Tucker3 and PARAFAC2 for exploring three-way environmental data.

2005: Kiers presented methods for calculating confidence intervals for CP and Tucker3 analysis results. Dyrby et al. applied the Tucker3 model to nuclear magnetic resonance time data, showing its usefulness in analyzing metabolic response to toxins. Wickremasinghe W.N. reviewed exploratory and confirmatory approaches for analyzing three-way data, focusing on Tucker3 analysis. García-Díaz J.C.; Prats-Montalbán J.M. characterized different soil types corresponding to citrus and rice using a Tucker3 model. Alves M.R.; Oliveira M.B. analyzed potato chips using a common load Tucker-1 model and predictive biplots. Acar E.; Çamtepe S.A.; Krishnamoorthy M.S.; Yener B. extended N-way data analysis techniques to multidimensional flow data, such as Internet chat room communication data. Kroonenberg P.M. provided an overview of model selection procedures in three-way models, particularly the Tucker2 model, the Tucker3 model, and the Parafac model. Ceulemans E.; Van Mechelen I. discussed hierarchical models for three-way binary data and proposed model selection strategies. Stanimirova I.; Simeonov V. modeled a four-way environmental dataset using PARAFAC and Tucker models to analyze air quality in industrial regions. Pasamontes A.; Garcia-Vallve S. used a multiway method called Tucker3 to analyze the amino acid composition in proteins of 62 archaea and bacteria.

2006: Jørgensen R.N.; Hansen P.M.; Bro R. investigated the use of repeated multispectral measurements and three-way component analysis to interpret measurements in winter wheat. Giordani P. addressed the problem of data reduction for fuzzy data using component models based on PCA and generalizations of three-way PCA. Ceulemans E.; Kiers H.A.L. proposed a numerical model selection heuristic for three-way principal component models. Singh K.P.; Malik A.; Singh V.K.; Sinha S. analyzed a dataset of soils irrigated with wastewater using two-way and three-way PCA models to assess soil contamination. Pasamontes A.; Garcia-Vallve S. used a multiway method called Tucker3 to analyze the amino acid composition in proteins of 62 archaea and bacteria. Acar E.; Bingöl C.A.; Bingöl H.; Yener B. compared linear, nonlinear, and multilinear data analysis techniques to locate the epileptic focus in EEG. Singh K.P.; Malik A.; Singh V.K.; Basant N.; Sinha S. analyzed the water quality of an alluvial river using four-way data models to extract hidden information. Dahl T.; Næs T. presented tools to analyze relationships between and within multiple data matrices, combining existing methods such as GCA and Tucker-1. Kiers H.A.L. discussed procedures to estimate compensating terms in three-way models before component analysis. Chiang L.H.; Leardi R.; Pell R.J.; Seasholtz M.B. compared the effectiveness of different methods for analyzing batch process data. Mitzscherling M.; Becker T. presented a new measurement system using Tucker3 decomposition to evaluate the quality of malt used. Cocchi M.; Durante C.; Grandi M.; Lambertini P.; Manzini D.; Marchetti A. used a three-way data analysis method (Tucker3) to investigate the evolution of components in Modena balsamic vinegar.

2007: Vichi M.; Rocci R.; Kiers H.A.L. discussed techniques for clustering units and reducing factorial dimensionality of variables and occasions in a three-way dataset. Singh and collaborators conducted a three-dimensional analysis of data obtained from riverbed sediments using multivariate component analysis. The Tucker3 model allowed for a joint interpretation of heavy metal distribution, element fractions, and particle sizes. Peré-Trepat and collaborators compared different multivariate data analysis methods on a three-dimensional dataset comprising 11 metal ions in fish, sediment, and water samples. Singh and collaborators analyzed the hydrochemistry of groundwater in the Indo-Gangetic alluvial plains using three-dimensional component analysis. The Tucker3 model revealed spatial and temporal variation in groundwater composition.

2008: Yener and collaborators described a trilinear analysis method for large datasets using a modification of the PARAFAC-ALS algorithm. Bandara and Wickremasinghe presented an approach for trilinear interaction analysis in trilinear experiments using Tucker3 analysis. Cocchi and collaborators monitored the evolution of volatile organic compounds from aged vinegar samples using trilinear data analysis. Hedegaard and Hassing proposed a new application of Raman scattering spectroscopy for multivariate classification problems, using trilinear data obtained from Raman spectra. Acar and Bro developed a clustering method in trilinear arrays for exploratory data visualization and identifying reasons for particular groups. Pardo and collaborators applied principal component analysis methods to two three-dimensional datasets to evaluate soil chemical fractionation patterns around a coal-fired power plant. Singh and collaborators used a trilinear model to analyze soil contamination in an industrial area and assess contaminant accumulation and mobility routes in soil profiles. Joyeux and collaborators adapted a PARAFAC-based method to denoise multidimensional images.

2009: Ceulemans and Kiers proposed model selection heuristics for choosing between Parafac and Tucker3 solutions of different complexities for three-dimensional datasets. Kopriva and Cichocki applied non-negative tensor factorization based on -divergence to the blind decomposition of multispectral images. Guebel and collaborators presented a procedure to discriminate between different operational response mechanisms in Escherichia coli using multivariate analysis. Tendeiro and Ten Berge investigated three-dimensional analysis methods such as three-dimensional PCA and Candecomp/Parafac. He Z. and Cichocki A. proposed a model selection approach for Tucker3 analysis based on PCA. Peng W. established a connection between NMF and PLSA in multi-dimensional data. Stegeman A. and De Almeida A.L.F. derived uniqueness conditions for a constrained version of parallel factor decomposition (Parafac). Oros G. and Cserháti T. demonstrated the antimicrobial effect of benzimidazolium salts using the Tucker model combined with cluster analysis. Dahl T. and Naes T. proposed a method to detect atypical assessors in descriptive sensory analysis. Bourennane S. et al. adapted multilinear algebra tools for aerial image simulation. Kopriva I. formulated a blind image deconvolution via 3D tensor factorization. Tsakovski S. et al. applied Tucker3 modeling to sediment monitoring data to assess contamination in a coastal lagoon. de Almeida A.L.F. et al. presented a restricted Tucker-3 model for blind beamforming.

2010: Giordani P. developed strategies to summarize imprecise data in a Tucker3 and CANDECOMP/PARAFAC model. Komsta L. et al. investigated retention in thin-layer chromatography and its analysis using PARAFAC. Kopriva I. used Higher-Order Orthogonal Iteration (HOOI) for spatially variant deconvolution of blurred images. Dong J.-D. et al. analyzed water quality in Sanya Bay using three-way principal component analysis. Astel A. et al. modeled three-way environmental data using the Tucker3 algorithm. Rocci R. and Giordani P. investigated the degeneration of the CANDECOMP/PARAFAC model and proposed solutions using the Tucker3 model. Kopriva I. and Cichocki A. applied non-negative tensor factorization to the decomposition of MRI images. Latchoumane C.-F.V. et al. used multidimensional tensor decomposition to extract discriminative features from EEGs in Alzheimer’s disease. Kopriva I. and Peršin A. proposed blind decomposition of multispectral images for tumor demarcation. Marticorena M. et al. characterized native maize populations using three-way principal component analysis. Favier G. and Bouilloc T. proposed a deterministic tensor approach for joint channel and symbol estimation in CDMA MIMO communication systems. de Araújo L.B. et al. proposed a systematic approach for studying and interpreting phenotypic stability and adaptability. Reis M.M. et al. applied a Tucker-3 model to environmental data, identifying evaporation and biodegradation processes. Kompany-Zareh M. and Van Den Berg F. presented a standardization algorithm based on Tucker-3 models for calibration transfer between Raman spectrometers.

2011: Oliveira M. and Gama J. proposed a strategy to visualize the evolution of dynamic social networks using Tucker decomposition. Durante C. et al. extended the SIMCA method to three-way arrays and applied it to food authentication. Kroonenberg P.M. and ten Berge J.M.F. investigated the similarities and differences between Tucker-3 and Parafac models. Wang H. et al. proposed a new Tucker-3 based factorization for feature extraction from large-scale tensors. Cordella C.B.Y. et al. used the Tucker-3 algorithm to analyze the relationship between chemical composition and sensory attributes of wheat noodles. Peng W. and Li T. studied the relationships between NMF and PLSA in multidimensional data, developing a hybrid method. Liu X. et al. presented a hybrid clustering method based on the Tucker-2 model for analyzing scientific publications. Kopriva I. et al. introduced a tensor decomposition approach for feature extraction from one-dimensional data. Unkel S. et al. proposed an ICA approach for three-dimensional data, applying it to atmospheric data. Russolillo M. et al. developed a multidimensional data analysis approach for the Lee-Carter model of mortality trends. Adachi K. presented a method for designing multivariate stimulus-response using an extended Tucker-2 component model. Cid F.D. et al. investigated temporal and spatial patterns of water quality in a reservoir using chemometric techniques. Phan A.H. and Cichocki A. proposed an algorithm for non-negative Tucker decomposition and applied it to high-dimensional data. Daszykowski M. and Walczak B. presented approaches for exploratory analysis of two-dimensional chromatographic signals. Lillhonga T. and Geladi P. used three-way methods to monitor composting batches over time, comparing them to traditional methods.

2012: Kroonenberg P.M. and van Ginkel J.R. proposed a Tucker-2 analysis procedure for three-way data with missing observations. Cordella et al. studied the degradation process of edible oils using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. They used both a classical kinetic approach and a multivariate approach to characterize the thermal stability of the oils. Györey et al. established a flavor language for table margarines and compared two sample presentation protocols for expert panels, finding better performance with the side-by-side protocol. Gomes et al. presented a systematization of complex data structures for process and product analysis, proposing a flexible framework to handle such challenging information sources. Favier et al. proposed a deterministic tensor approach for joint channel and symbol estimation in CDMA communication systems. Akhlaghi et al. investigated DNA hybridization using gold nanoparticles and chemometric analysis techniques to study interactions of oligonucleotides from the HIV genome. Khayamian et al. proposed a second-order calibration method, Tucker 3, for ion mobility spectrometry data. Gredilla et al. compared various multivariate methods for pattern recognition in environmental datasets, concluding that PCA is suitable for general interpretation. Liu et al. proposed a new method to reduce noise in hyperspectral images using multidimensional Wiener filtering based on Tucker 3 decomposition. Soares et al. used statistical designs to extract substances from Erythrina speciosa leaves and analyzed the extracts using multivariate analysis methods. Prieto et al. applied the Tucker 3 method to evaluate the performance of an electronic nose in monitoring the aging of red wines. Ulbrich et al. analyzed data on organic aerosol composition in Mexico using 3D factorization models, identifying several types of aerosols and their size distributions. Gao et al. conducted a risk assessment of heavy metals in soils of mining areas, using the Tucker 3 model to assess contamination and ecological risk. Calsbeek presented a method to compare non-parametric fitness surfaces over time or space using Tucker 3 tensor decomposition. De Araújo et al. proposed a method to study and interpret a variable response in relation to three factors using the Tucker 3 model. Stegeman addressed problems with CP decomposition by fitting constrained Tucker 3 models for chemical equilibrium data. Liu et al. proposed a denoising method for hyperspectral images based on PARAFAC decomposition. Kompany-Zareh et al. extended the core consistency diagnostic to constrained Tucker 3 models to validate the dimensionality and core pattern. Gallo provided convenient symbols to define the sample space for different composition vectors that can be organized into a three-dimensional matrix. Baum et al. used chemometric methods to quantify the enzymatic activity of pectolytic enzymes, highlighting the effectiveness of the Tucker 3 model compared to other methods. Liu et al. presented a sparse component analysis method based on non-negative Tucker 3 decomposition to improve the dispersion of original diagnostic signals.

2013: Wang and Xu proposed a sparse component analysis method based on non-negative Tucker 3 decomposition to improve the dispersion of original diagnostic signals. Gallo M., Buccianti A. used a particular version of the Tucker model to analyze water samples collected from the Arno River in Italy, evaluating the method’s effectiveness. De Roover K. et al. demonstrated that component methods for three-way data can capture interesting structural information in the data without strictly imposing certain assumptions. Amigo J.M., Marini F. provided an overview of the main multiway methods used for data decomposition, calibration, and pattern recognition. Wang H., Xu F. et al. investigated non-negative Tucker3 decomposition methods for feature extraction from images. Attila G. et al. evaluated the reliability of sensory panels assessing beer samples using multivariate techniques. Gallo M., Simonacci V. presented the theory behind the Tucker3 model in compositional data and described the TUCKALS3 algorithm. Pardo R. et al. determined the chemical fractionation patterns of metals in waste generated during the optimization of a reactor for the removal of metals from wastewater. Bro R., Leardi R., Johnsen L.G. developed a method to correct sign indeterminacy in bilinear and multilinear models. Erdos D., Miettinen P. proposed using Boolean Tucker tensor decomposition for extracting subject-predicate-object triples from open information extraction data. Oliveira M., Gama J. proposed a methodology to track the evolution of dynamic social networks using Tucker3 decomposition. Tortora C. et al. extended probabilistic distance clustering to the context of factorial clustering methods using Tucker3 decomposition. Liu K. et al. proposed a method for determining the number of components in PARAFAC or Tucker3 models. Wang H., Xu F. et al. investigated non-negative Tucker3 decomposition methods for diagnosing mechanical faults. Qiao M. et al. analyzed the content and spatial distribution of heavy metals in river sediments in Beijing using the Tucker3 model for ecological risk assessment. Lin, Tao, Bourennane, Salah presented a review on denoising methods for hyperspectral images based on tensor decompositions, including Tucker3 decomposition.

2014: Barranquero R.S. et al. evaluated the hydrochemical behavior of groundwater in a basin in Argentina using multivariate techniques, including Tucker3 decomposition. Kompany-Zareh M., Gholami S. investigated the interaction of DNA conjugated with quantum dots with 7-aminoactinomycin D using constrained Tucker3 decomposition. Tortora C., Marino M. applied factorial clustering to behavioral and social datasets using Tucker3 decomposition. Cavalcante I.V. et al. proposed a method to jointly estimate channel matrices in a MIMO communication system assisted by repeaters using PARAFAC and Tucker2 decompositions. Giordani P., Kiers H.A.L., Del Ferraro M.A. presented the R package ThreeWay for handling three-dimensional matrices, including the T3 and CP functions for Tucker3 and Candecomp/Parafac decompositions. Yokota T.; Cichocki A. proposed a new algorithm for flexible multiway data analysis called linked Tucker2 decomposition (LT2D), useful for estimating common components and individual features of tensor data. Tang X.; Xu Y.; Geva S. proposed a user profiling approach using a tensor reduction algorithm based on a Tucker2 model, improving neighborhood formation quality in collaborative neighborhood-based recommendation systems. Kroonenberg P.M. evaluated the factorial invariance of bidirectional classification designs using Tucker and Parafac models, demonstrating the usefulness of these models in attachment theory. Gere A. et al. established internal and external preference maps using parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC) and Tucker-3 methods to evaluate sweet corn varieties. Engle M.A. et al. applied a Tucker3 model to water quality monitoring data to simplify the processing and interpretation of composition data. Dhulekar N. et al. presented a novel model for modeling brain neural activity by synchronizing EEG signals using unsupervised learning techniques and Tucker3 tensor decomposition to detect epileptic seizures. Wang, Hai-jun et al. proposed a method for non-negative Tucker3 decomposition using the conjugate Lanczos method to improve efficiency and accuracy.

2015: Dell’Anno R.; Amendola A. proposed a general index of social exclusion and analyzed its relationship with economic growth in European countries using a Tucker3 model. Rato T. et al. described batch process monitoring methods based on Tucker3 and PARAFAC decompositions, demonstrating their usefulness in optimizing and monitoring industrial processes. Gallo M. explored three-way exploratory data analysis using the Tucker3 model applied to compositional data. Ortiz M.C. et al. described the PARAFAC model and presented alternatives such as PARAFAC2 and Tucker3 for three-way data, illustrating their usefulness in various analytical scenarios. Khokher M.R. et al. proposed a method for detecting violent scenes using tensor decomposition of superdescriptors, improving violence detection accuracy in videos.

2016: van Hooren M.R.A. et al. used Tucker3 tensor decomposition to differentiate between head and neck carcinoma and lung carcinoma by analyzing volatile organic compounds in breath. Ikemoto H.; Adachi K. proposed a Tucker2 model with a sparse core (ScTucker2) for three-way data analysis, demonstrating its utility in dimensionality reduction and feature selection. Silva A.C.D. et al. investigated the use of two-dimensional linear discriminant analysis (2D-LDA) on three-way spectral data, demonstrating its effectiveness in classifying foods and chemicals. Azcarate S.M. et al. modeled data on Argentine white wines using Tucker3 tensor decomposition, allowing discrimination between samples of wines produced from different grape varieties. Tortora C. et al. developed a factor clustering method based on Tucker3 decompositions, improving the performance of probabilistic clustering algorithms on large datasets. Keimel C. explored three-way data analysis methods without prior clustering, highlighting the application of multi-way component models such as Tucker3 and PARAFAC. Barranquero R.S. et al. compared the chemical composition and spatial and temporal variability of groundwater in two basins using multi-way component analysis models such as PARAFAC and Tucker3. Ebrahimi S.; Kompany-Zareh M. investigated the kinetics and thermodynamics of reversible hybridization reactions using constrained tensor decompositions, demonstrating their utility in three-way data analysis. Wang H., Deng G., Li Q., Kang Q. proposed a new method for diagnosing faults in the exhaust system of a car using non-negative Tucker3 decomposition (NTD) to extract useful features from vehicle exterior noise. Du J.-H., Tian P., Lin H.-Y. presented a scheme based on the Tucker-2 model for joint signal detection and channel estimation in multiple input and multiple output (MIMO) systems. Liu R., Men C., Liu Y., Yu W., Xu F., Shen Z. analyzed the spatial distribution patterns and ecological risks of heavy metals in the Yangtze River Estuary. Bayat M., Kompany-Zareh M. reported a simple and efficient approach to estimate the sparsest Tucker3 model for a linearly dependent multiway data array using PARAFAC profiles.

2017: Wang C., Du J., Hu Q., Wu Y. present a scheme based on the Tucker-2 model for channel estimation in multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) relay systems. Tanji K., Imiya A., Itoh H., Kuze H., Manago N. analyze hyperspectral images using tensor principal component analysis on multiway datasets. Dinç E., Ertekin Z.C., Büker E. process excitation-emission matrix datasets using various chemometric calibration algorithms for the simultaneous quantitative estimation of valsartan and amlodipine besylate in tablets. You R., Yao Y., Shi J. adopt a third-order tensor decomposition method, Tucker3, for defect detection based on ultrasonic testing in fiber-reinforced polymer structures.

2018: Kim T., Choe Y. present a real-time background subtraction method using tensor decomposition to overcome the limitations of iteration-based methods. Bergeron-Boucher M.-P., Simonacci V., Oeppen J., Gallo M. propose the use of multilinear component techniques to coherently forecast the mortality of subpopulations, such as countries in a region or provinces within a country. Chachlakis and Markopoulos presented an approximate algorithm for rank-1 decomposition based on the L1-TUCKER2 norm of three-dimensional tensors, highlighting its robustness against corruption compared to methods such as GLRAM, HOSVD, and HOOI. Giordani and Kiers reviewed 3D tensor analysis methods and applied these methods to healthcare data, discovering peculiar aspects of healthcare service usage over time. Rambhatla, Sidiropoulos, and Haupt proposed a technique to develop topological maps from Lidar data using the orthogonal Tucker3 tensor decomposition, highlighting its accuracy in detecting the position of autonomous vehicles. Markopoulos, Chachlakis, and Papalexakis studied the L1-TUCKER2 decomposition and presented the first exact algorithms for its solution, demonstrating their effectiveness in handling outlier data. Rahmanian, Salehi, and Abiri proposed a colorization technique based on tensor properties, using Tucker3 tensor decomposition to extract color information and apply it to grayscale images.

2019: Du, Ye, Wang, and Chen proposed a low-complexity algorithm for joint channel estimation in MIMO relay systems, demonstrating its effectiveness even in highly correlated channels. Weisser, Buchholz, and Keidser developed a framework to study the complexity of acoustic environments and evaluated their impact on human perception, using tensor models to analyze complex acoustic scenes. Hu and Wang presented a multi-channel signal filtering technique and bearing fault diagnosis using tensor factorization, demonstrating its effectiveness in detecting bearing faults through vibration signals. Khokher, Bouzerdoum, and Phung proposed an approach for dynamic scene recognition based on the decomposition of tensor super-descriptors, outperforming existing methods in terms of recognition accuracy. Lestari, Pasaribu, and Indratno compared two methods for obtaining a graphical representation of the association between three categorical variables, highlighting the advantages of three-dimensional correspondence analysis (CA3) based on Tucker3 decomposition. Lee G. proposes an efficient algorithm for higher-order singular value decomposition in hyperspectral images, enabling compression of large amounts of data while maintaining accuracy. Gomes P.R.B. et al. propose a tensor-based modeling approach for channel estimation and receiver design in V2X communication systems, improving accuracy in highly mobile scenarios.

2020: Du J. et al. present a tensor-based method for joint signal and channel estimation in massive MIMO relay systems, without the need for pilot sequences, achieving better performance than existing methods. Liu J. et al. propose a generalized tensor PCA method for batch process monitoring, which avoids destroying the essential structure of raw data and improves monitoring quality. Lin R. et al. propose a convolutional neural network compression scheme using low-rank tensor decomposition, achieving highly compressed CNN models with little sacrifice in accuracy.

2021: Zilli G.M.; Zhu W.-P. propose a hybrid precoder-combiner design for massive MIMO OFDM systems in millimeter waves, maximizing the average achievable sum rate. Han X.; Zhao Y.; Ying J. present semi-blind receivers for dual and triple-hop MIMO sensor systems, with better performance than tensor-based training methods. Ramos M. et al. highlight basic multivariate statistical process control (MSPC) techniques under dimensionality criteria, such as multivariate PCA, Joint Independent Component Analysis, among others. Gherekhloo S. et al. consider the design of two-way MIMO-OFDM relay systems with hybrid analog-digital architecture, proposing a suboptimal solution for the HAD amplification matrix. Martin-Barreiro C. et al. proposed a heuristic algorithm to compute disjoint orthogonal components in the three-dimensional Tucker model, facilitating the interpretation of three-dimensional data.

2022: Bilius L.-B. & Pentiuc S.G. used Tucker1 decomposition for tensor compression and dimensionality reduction in hyperspectral images, followed by PCA to classify extracted features. Lin Q.-H. et al. proposed a Tucker-2 model with spatial sparsity constraints to analyze multi-subject fMRI data, improving the extraction of common spatial and temporal components across subjects. dos Santos R.F. et al. employed fluorescence matrices combined with machine learning to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease, achieving high sensitivity and specificity with PARAFAC-QDA and Tucker3-QDA models. Frutos-Bernal E. et al. modeled incoming traffic in the Barcelona metro as a three-dimensional tensor, using Tucker3 decomposition to uncover spatial and temporal patterns. Zhang J. et al. developed an algorithm to locate myocardial infarction (MI) from 12-lead electrocardiogram signals with an accuracy of 99.67% and an F1 score of 0.9997. Pan Y. and Wang M. presented a toolkit called TedNet that implements 5 types of tensor decomposition for deep neural layers. Du J. et al. proposed an efficient channel estimation scheme based on the Tucker-2 tensor model for massive MIMO relay systems.

2023: An J. et al. demonstrated that only four key chemical parameters are necessary to accurately predict 35 sensory attributes of a wine, significantly reducing analytical and labor costs. Bilius L.-B. et al. introduced TIGER, a gesture recognition method based on multilinear tensors, using Tucker2 decomposition to reduce the dimensionality of the training set. Zhang Q. et al. proposed a method for hyperspectral image restoration using Tucker tensor factorization and deep learning, outperforming methods driven by models or data alone. Gabor M. and Zdunek R. presented a convolutional neural network compression technique based on hierarchical Tucker-2 tensor decomposition. Dinç E. et al. conducted a comparative study applying two-dimensional and three-dimensional data analysis methods to excitation-emission fluorescence matrices to estimate the concentration of two active pharmaceutical ingredients. Cong J. et al. designed a radar parameter estimation method for FMCW MIMO radars based on compressed PARAFAC factorization. Phougat M. et al. applied multivariate analysis techniques to study the dynamic structure of the first solvation layer of peptides perturbed with increasing concentrations of acetonitrile. Koleini F. et al. demonstrated the complementary nature of Simultaneous Component Analysis of Variance (ASCA+) and Tucker3 tensor decompositions in multivariable data. Cohen J. et al. described low-dimensional tensor decomposition methods for source separation in fields such as fluorescence spectroscopy and chromatography. Lombardo R. et al. presented an R package for three-dimensional correspondence analysis, enabling visualization and modeling of three-dimensional categorical data. Reitsema, A. M. et al. investigated emotional dynamics profiles in adolescents, identifying components of positive affect, negative affect, and irritability using three-dimensional decomposition.

According to ChatGPT 3.5, during the period from 2000 to 2023, significant research has been conducted in the field of tensor decomposition and multidimensional data analysis. These studies have focused on various approaches and applications, primarily on Tucker3 and PARAFAC models, as well as the development of advanced techniques for pattern identification, information extraction, and enhanced interpretation of complex data.

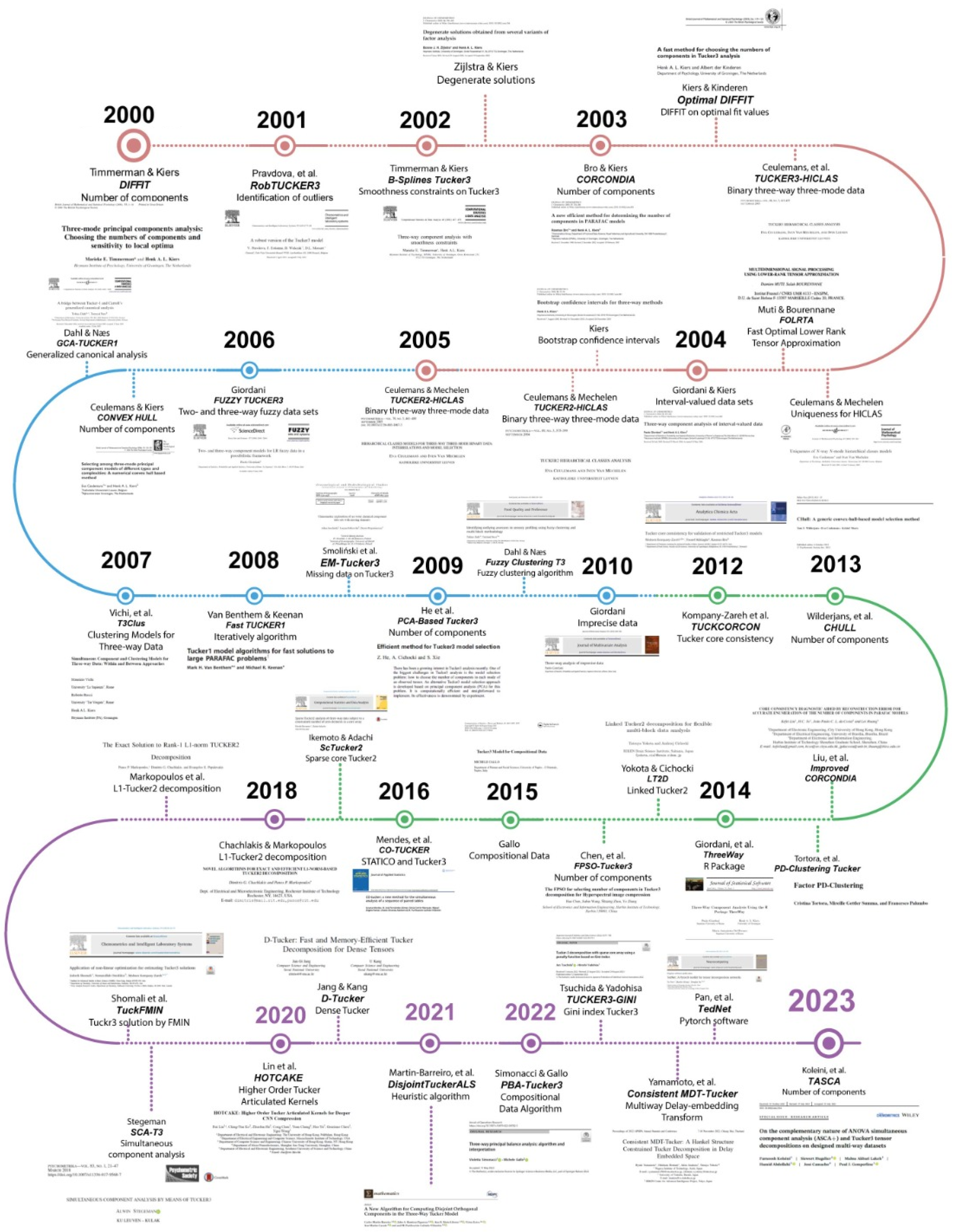

4.7. Timeline of the Development of Tucker Models in the New Millennium

Overall, the period from 2000 to 2023 has witnessed significant progress in the field of tensor decomposition and multidimensional data analysis. Researchers have achieved advances in theory, algorithms, and practical applications, leading to a greater understanding and use of Tucker models across various disciplines.

Figure 8 presents the main findings related to Tucker models in the new millennium, resulting from Text Mining based on Biplot and ChatGPT 3.5.

At the beginning of this new millennium, Timmerman and Kiers in 2000 [

12] introduced a new method, called

DIFFIT, that determines the optimal number of components to use in the Tucker-3 model, a challenge that persists to this day. The effectiveness of

DIFFIT is compared with two methods based on two-way PCAs through a simulation study, concluding that

DIFFIT significantly outperforms the other methods in indicating the correct number of components. Furthermore, the sensitivity of the TUCKALS3 algorithm in estimating the 3MPCA is examined, finding that, when the number of components is correctly specified, it avoids local optima. However, the occurrence of local optima increases with the discrepancy between the underlying components and those estimated by TUCKALS3, with fewer local optima occurring in runs initiated rationally compared to random starts. The following year, Pravdova, et al. [

84] presented a robust method, called

RobTUCKER3, for identifying outliers in the Tucker-3 model, highlighting its effectiveness in both simulated and real data.

In 2002, there were two important contributions. On one hand, Timmerman and Kiers [

85] proposed a three-dimensional component analysis with smoothness constraints, which improved the estimation of model parameters in functional data. In this research, smoothness conditions were posed using the family of

B-Splines functions. On the other hand, [

86] investigated degenerate solutions, highlighting the importance of unique components in generating stable and interpretable solutions.

Methodological development was also highlighted by Bro and Kiers in 2003 [

87], who introduced a new efficient method, the core consistency diagnostic called

CORCONDIA, to determine the appropriate number of components in multi-dimensional models such as PARAFAC. This tool proved effective in selecting appropriate models, although it was noted that the theoretical understanding was not yet complete. This diagnostic is based on evaluating the "appropriation" of the structural model concerning the data and the estimated parameters of gradually increased models, and it has proven to be an effective tool in determining the number of components. Continuing with the challenge of the number of components, Kiers and Kinderen, 2003 [

88] proposed a quick method for choosing the number of components in Tucker-3 analysis, the

improved DIFFIT. Their alternative procedure is based on a single, fast analysis of the three-dimensional dataset, providing comparable effectiveness results to the original method proposed by Timmerman and Kiers in 2000.

Regarding binary data, Ceulemans, et al., 2003 [

89] proposed a new model for 3-way 3-mode, called

Tucker3-HICLAS. Along the same lines, Ceulemans and Mechelen, 2003 [

90] investigated and demonstrated two uniqueness theorems for hierarchical class models in

N-way N-mode data, that is, for multi-way binary data. Additionally, Muti and Bourennane, 2003 [

91] presented a new method for the approximation of low-rank tensors, known as

FOLRTA, highlighting its efficiency in noise reduction in applications such as color image processing and seismic signals. These studies underline the diversity of approaches to addressing problems related to multi-way models and the importance of efficient methods for determining the number of components in multidimensional data analysis.

Regarding variants of three-dimensional component analysis, Giordani and Kiers, 2004 [

92] extended principal component analysis to three-dimensional data with interval values, applying methods such as Tucker-3 and CANDECOMP/PARAFAC. Simultaneously, Kiers, 2004 [

93] introduced a bootstrap procedure to provide confidence intervals for all output parameters in three-dimensional analysis, enabling the evaluation of the stability of the obtained solutions.

Ceulemans focused several of his studies on binary data; thus, in 2004 [

94] introduced a new hierarchical class model called

Tucker2-HICLAS, and the following year [

95] they presented

Tucker1-HICLAS, thereby addressing binary data for the various modes. These models include a hierarchical classification of the elements of each mode, highlighting a distinctive feature that retains the differences between the association patterns of the elements in each of the modes.

Giordani, 2006 [

96] addressed the problem of data reduction for fuzzy data, introducing several component models to handle two-way and three-way fuzzy datasets. For Tucker models, this includes the

Fuzzy Tucker3 model. The two-way models are based on classical principal component analysis (PCA), while the three-way models are based on three-dimensional generalizations of PCA, such as Tucker-3 and CANDECOMP/PARAFAC. These models leverage possibilistic regression, treating component models for fuzzy data as regression analyses between a set of observed fuzzy variables (response variables) and a set of unobserved crisp variables (explanatory variables). On the other hand, Ceulemans and Kiers, 2006 [

97] addressed the selection of three-mode principal component models of different types and complexities. They proposed a numerical method based on a convex hull, known as

CONVEX HULL, to select the appropriate model and complexity for a specific dataset, showing that this method works almost perfectly in most cases, except for Tucker3 data arrays with at least one small mode and a relatively large amount of error.

Regarding canonical analysis techniques, Dahl and Næs, 2006 [

98] presented the

GCA-Tucker1 model, which analyzes relationships between and within multiple data matrices, unifying Carroll’s Generalized Canonical Analysis (GCA) methods with the Tucker1 method for principal component analysis of multiple matrices. Meanwhile, Vichi et al., 2007 [

99] implemented clustering techniques for three-way data, presenting the

T3Clus model.

In the development of algorithms that accelerate computational performance for large volumes of three-way data, Van Benthem and Keenan, 2008 [

100] described the

FastTUCKER1 method for performing trilinear analysis on large datasets using a modification of the PARAFAC-ALS algorithm based on the Tucker1 model, allowing for a solution 60 times faster for massive PARAFAC data problems that do not fit in the computer’s main memory, resulting in a significant improvement in performance. Meanwhile, Smoliński et al., 2008 [

101] proposed using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm on the Tucker-3 model, called

EM-Tucker3, to handle missing data in chemometric analyses. Additionally, He et al., 2009 [

102] presented an efficient approach for model selection in Tucker-3 analysis based on principal component analysis (PCA),

PCA-Based Tucker3, demonstrating computational efficiency and effectiveness in selecting the number of components for each mode. Meanwhile, Dahl and Næs, 2009 [

103] introduced a method,

Fuzzy Clustering T3, for identifying atypical evaluators in descriptive sensory analysis based on fuzzy clustering and multiple block methodology.

Giordani, 2010 [

104] proposed an approach for the analysis of three-way imprecise data, focusing on transforming these data into fuzzy sets for further analysis. This method involves using generalized Tucker-3 and CANDECOMP/PARAFAC models to examine the underlying structure of the resulting fuzzy sets. Additionally, the statistical validity of the identified structure is evaluated using bootstrapping techniques, providing a robust tool for summarizing samples of uncertain data. On the other hand, Kompany-Zareh et al., 2012 [

105] extended the core consistency diagnostic to validate restricted Tucker3 models, now with the

TUCKCORCON model, offering a tool to assess the adequacy of the constraints applied to Tucker-3 analysis.

In 2013, methods continued to be developed for determining the number of components for each mode. Wilderjans et al., 2013 [

106] proposed the model called

CHULL, which addresses the model selection problem researchers face when analyzing data. This problem includes determining the optimal number of components or factors in principal component analysis (PCA) or factor analysis, as well as identifying the most important predictors in regression analysis. Meanwhile, Liu et al., 2013 [

107] proposed a method to improve accuracy in determining the number of components in PARAFAC models, using a core consistency diagnostic approach with error reconstruction called

Improved CORCONDIA. Tortora et al., 2013 [

108] extended probabilistic distance clustering to the context of factorial methods,

PD-Clustering Tucker, combining Tucker-3 decomposition with PD clustering for greater stability in clustering complex data.

Giordani et al., 2014 [

109] presented the R package, named

ThreeWay, highlighting its main features and functions, such as T3 and CP, which implement the Tucker-3 and Candecomp/Parafac methods, respectively, for analyzing three-dimensional arrays. Yokota and Cichocki, 2014 [

110] proposed the linked Tucker-2 decomposition model (

Linked Tucker2 - LT2D) for flexible analysis of multi-block data, demonstrating its efficacy and convergence properties. On the other hand, Chen et al., 2014 [

111] proposed the

FPSO-Tucker3 method to select the number of components in Tucker-3 decomposition for hyperspectral image compression, using a particle swarm optimization-based approach (FPSO).

Gallo, 2015 [

112] described the compositional data Tucker-3 analysis, highlighting the importance of considering the specific characteristics of this type of data. Mendes et al., 2017 [

113] proposed the CO-TUCKER method for the simultaneous analysis of a sequence of paired tables, offering a new perspective for understanding structure-function relationships in ecological communities. Additionally, Ikemoto and Adachi [

114] developed a procedure to find an intermediate model between Tucker-2 and Parafac for analyzing three-dimensional data. In the proposed model, called "Sparse Core Tucker2" (

ScTucker2), the Tucker-2 loss function is minimized subject to a specified number of zero core elements, whose locations are unknown; the optimal locations of the zero elements and the values of the non-zero parameters are simultaneously estimated. An alternating least squares algorithm is presented for

ScTucker2 along with a procedure to select an appropriate number of zero elements. Additionally, Tortora et al., 2016 [

115] proposed the

FPDC-Tucker3 model, which consists of clustering factors using probabilistic distances.

Chachlakis and Markopoulos, in 2018, proposed an approximate algorithm for the

L1-TUCKER2 decomposition of three-dimensional tensors, highlighting its resistance to data corruption compared to conventional methods [

116]. Additionally, they developed exact and efficient algorithms for this decomposition, demonstrating their robustness against outliers and outperforming counterparts based on L2 and L1 norms [

117]. On the other hand, Shomali et al. applied nonlinear optimization techniques to estimate Tucker-3 solutions by minimizing the objective function (

TuckFMIN), while Stegeman introduced a model for the simultaneous analysis of components using Tucker-3, demonstrating its effectiveness across various datasets [

118,

119]. Additionally, Lin and collaborators proposed

HOTCAKE for compressing convolutional neural networks, while Jang and Kang presented

D-Tucker, a fast and efficient method for the decomposition of dense tensors, noted for its speed and memory efficiency [

120,

121].

Martin-Barreiro and collaborators, in 2021, proposed a heuristic algorithm for computing disjoint orthogonal components in the three-way Tucker model, known as

DisjointTuckerALS, thereby facilitating the analysis of three-dimensional data and the interpretation of results [

122]. Meanwhile, Simonacci and Gallo, in 2022, presented

PBA-Tucker3 as a three-way principal component analysis using Tucker-3 decomposition, with applications in the composition of academic recruitment fields by macro-region and gender/role in Italy [

123]. Tsuchida and Yadohisa proposed a Tucker-3 decomposition with a sparse core using a penalty function based on the Gini index, known as

TUCKER3-GINI, allowing for a simpler interpretation of the results [

124]. Additionally, Yamamoto and collaborators presented

Consistent MDT-Tucker, a low-dimensional tensor decomposition method that preserves the Hankel structure in data transformed by Multiway Delay-embedding Transform [

125]. Pan and collaborators developed

TedNet, a PyTorch tool for tensor decomposition networks, implementing five types of tensor decomposition in traditional deep neural network layers, facilitating the construction of various neural network models [

126]. Finally, Koleini and collaborators, in 2023, demonstrated the complementary nature of simultaneous analysis of variance components (ASCA+) and Tucker-3 tensor decompositions in designed datasets, showing how ASCA+ can identify statistically sufficient and significant Tucker-3 models. This model is called

TASCA, thereby simplifying the visualization and interpretation of the data [

127].

Here are the main findings of the articles grouped by year:

Here are the main findings of the articles grouped by year: