Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Origin of Pb Pollution

2.1. Natural Occurrence of Pb

2.1.1. Soil

2.1.2. Water

2.1.3. Air

2.2. Anthropogenic Pb Sources

3. Pb Toxicity on Living Organisms

3.1. Pb Accumulation and Toxicity on Bacteria

3.1.1. Resistance Mechanisms of Bacteria

3.1.2. Bacteria in Pb-Contaminated Soil

3.2. Pb Accumulation and Toxicity on Fungi

3.3. Pb Accumulation and Toxicity on Edible Mushrooms

3.4. Pb Accumulation and Toxicity on Plants

3.5. Pb Accumulation and Toxicity on Animals

3.6. Pb Accumulation and Toxicity on Human

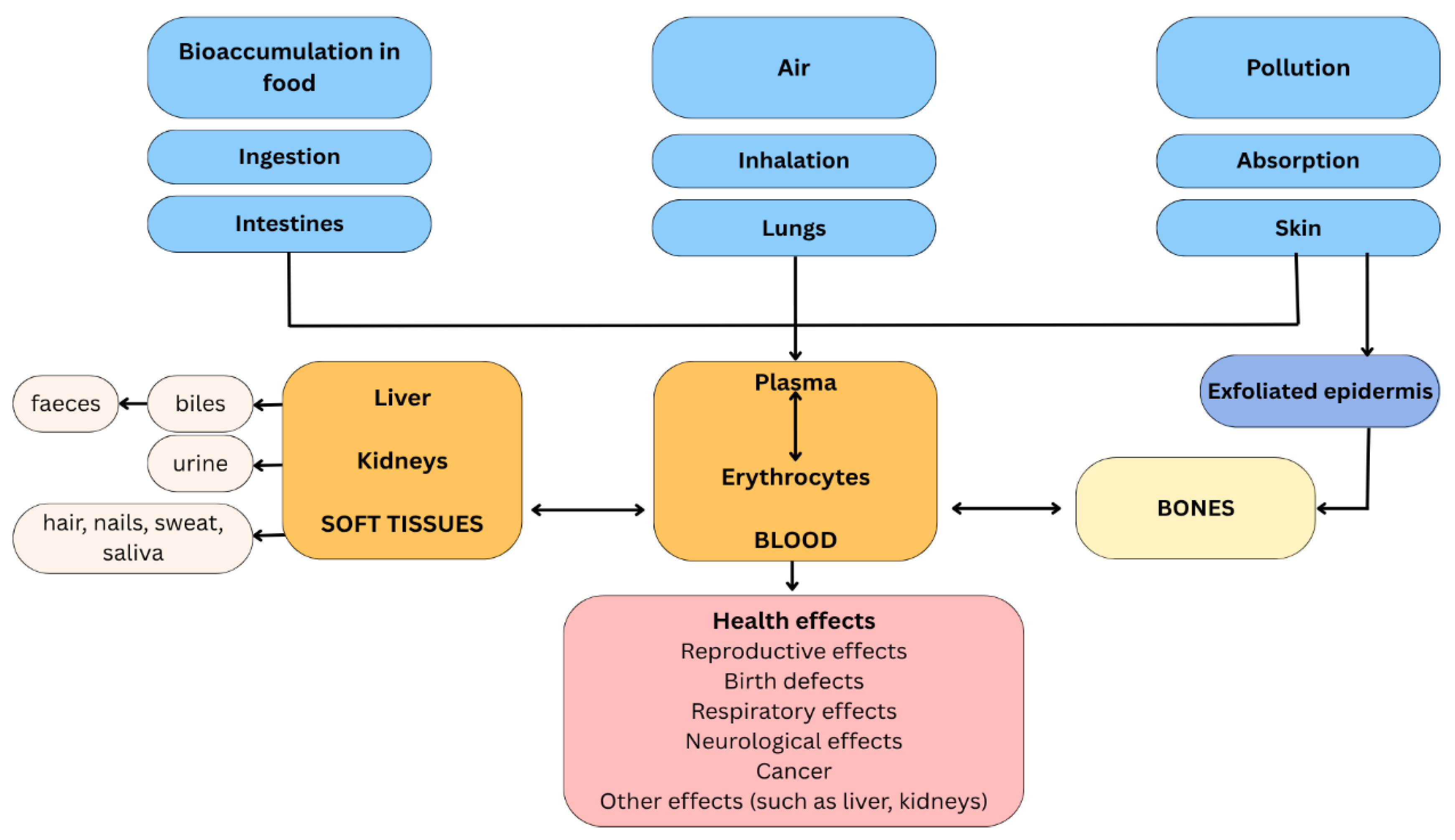

3.6.1. Pb Distribution in the Human Body

3.6.1.1. Inhalation

3.6.1.2. Ingestion

3.6.1.3. Permeation

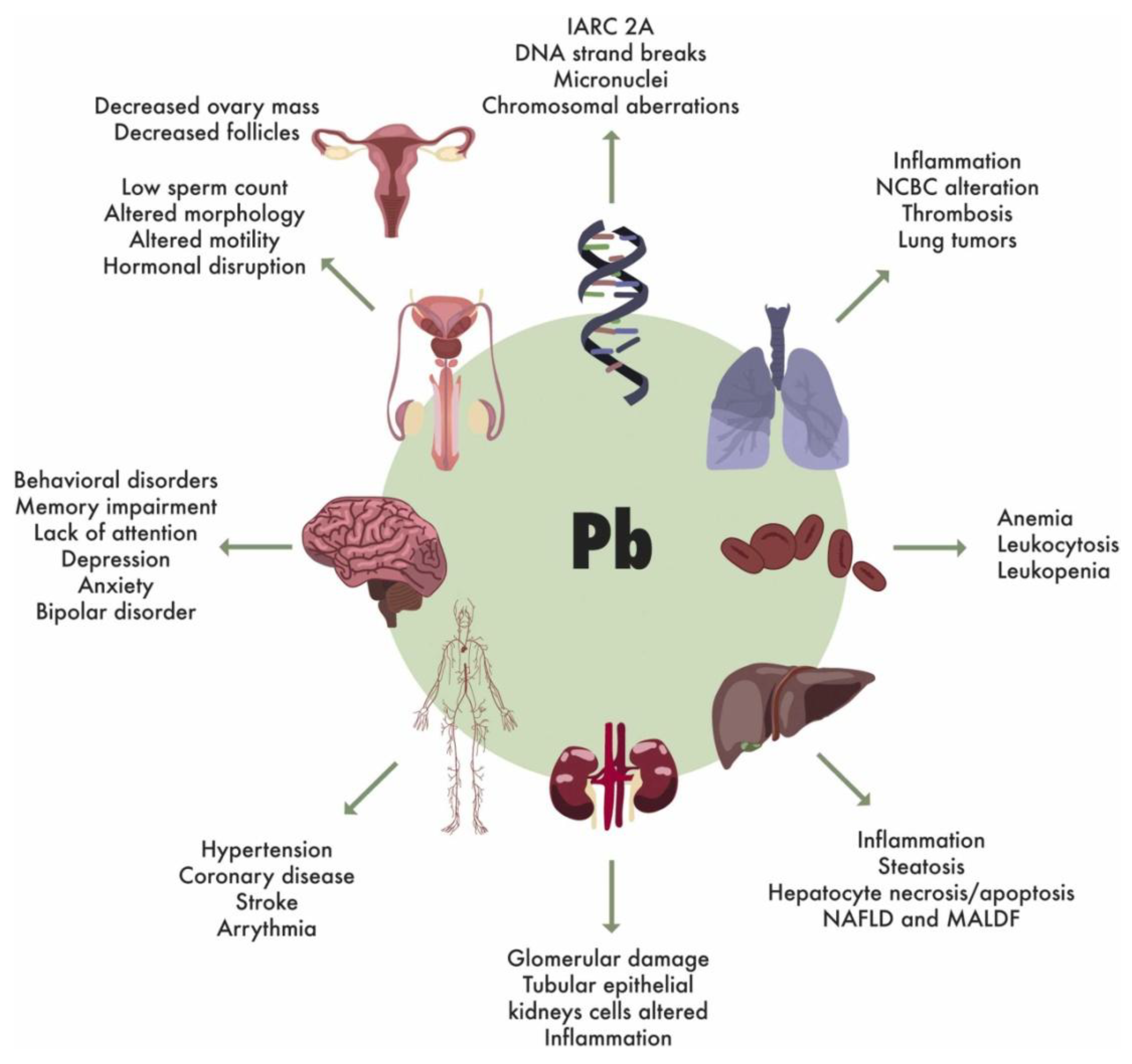

3.6.2. Harmful Effects on Human Organs and Systems

3.6.2.1. Effects on the Blood and Circulatory System

3.6.2.2. Effects on the Reproductive System

3.6.2.3. Effects on the Respiratory System

3.6.2.4. Effects on the Kidney System

3.6.2.5. Effects on the Bones

3.6.2.6. Effects on the Liver and Intestines

3.6.2.7. Effects on the Central Nervous System

3.6.2.8. Effects on the Immune System

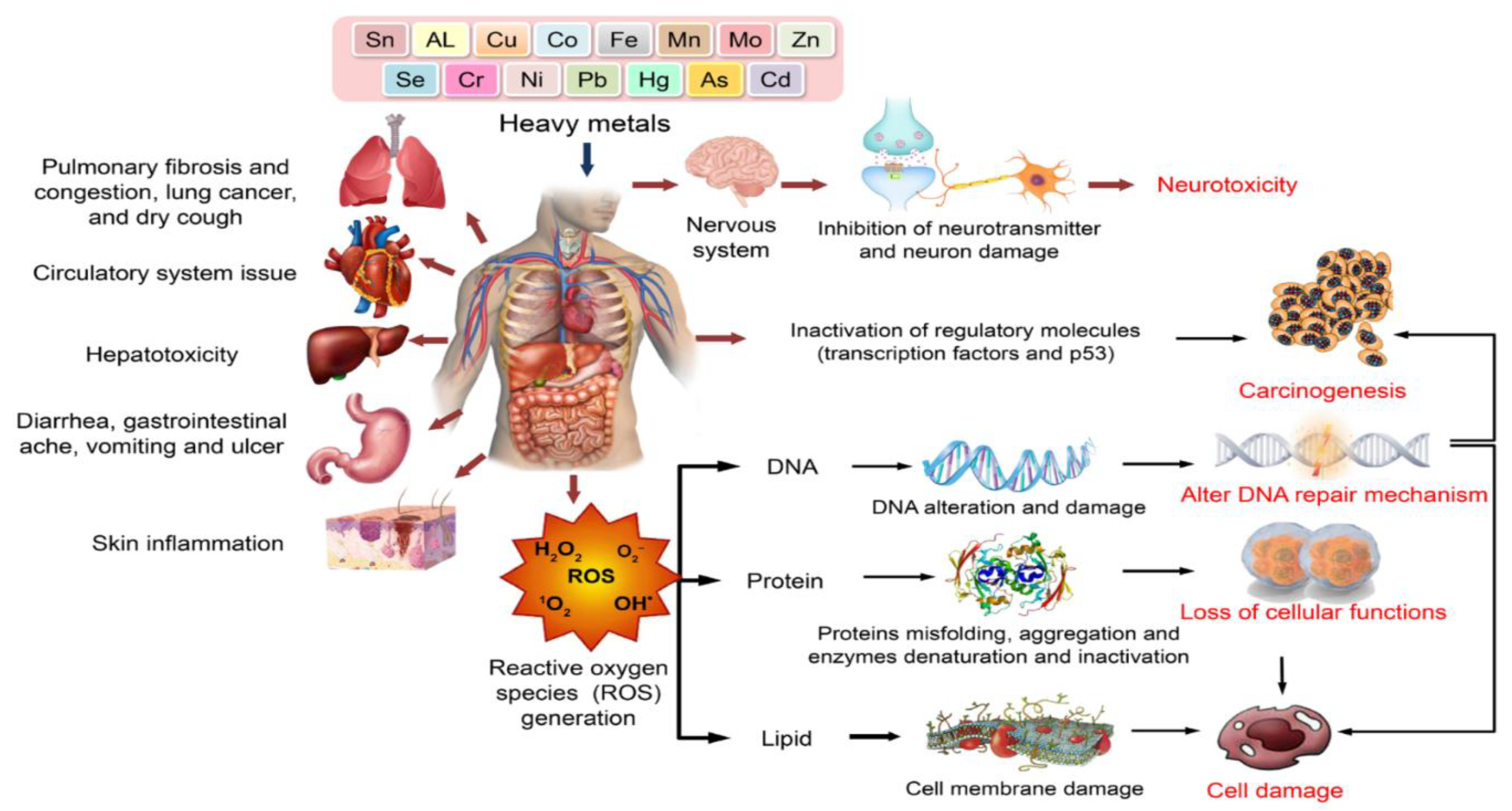

4. Molecular Mechanisms of Pb Toxicity

4.1. Ion Mimicry and Cellular Disruption

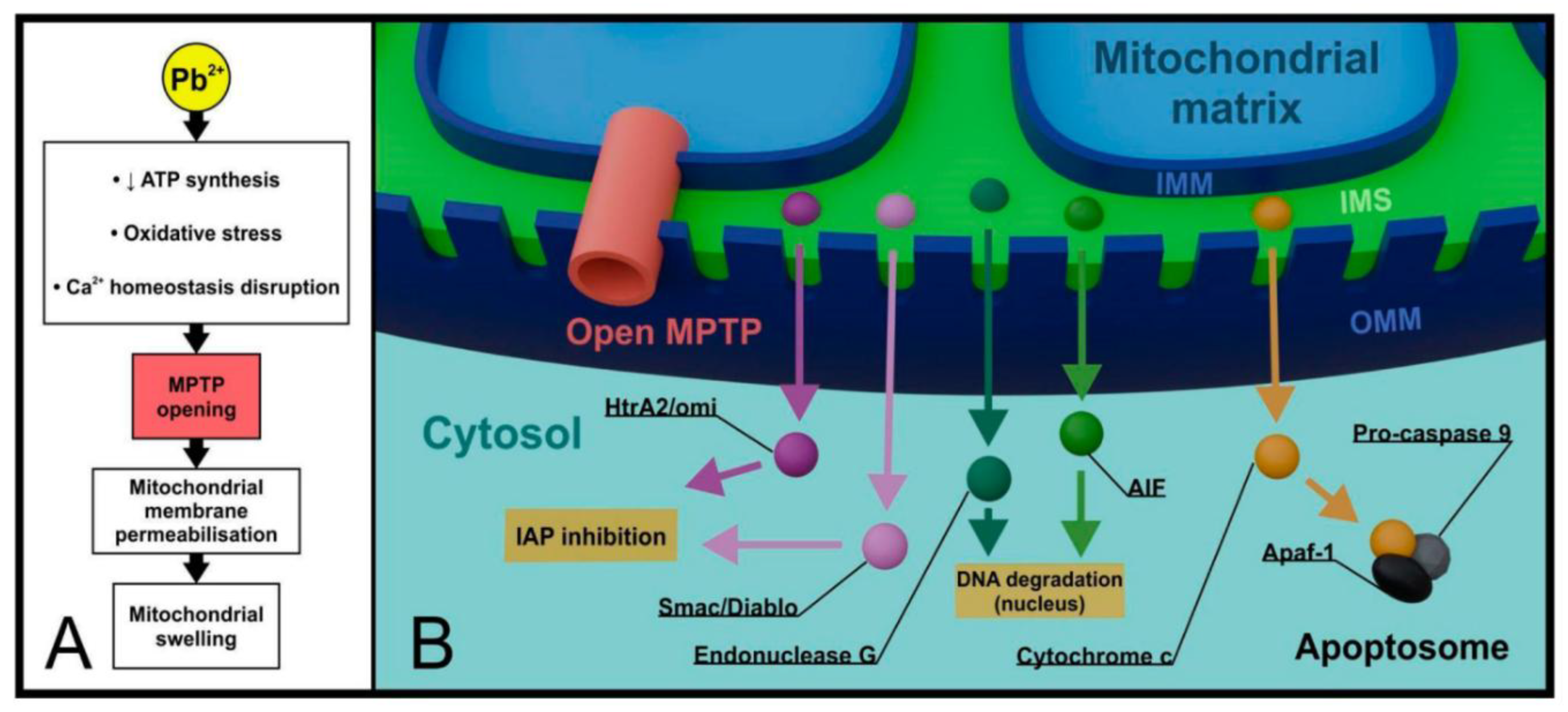

4.2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Energy Metabolism

4.3. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Depletion

4.4. Neuroinflammation and Immune Response

4.5. DNA Damage and Genotoxicity

4.6. Epigenetic Modifications

4.7. Autophagy and Cell Death Pathways

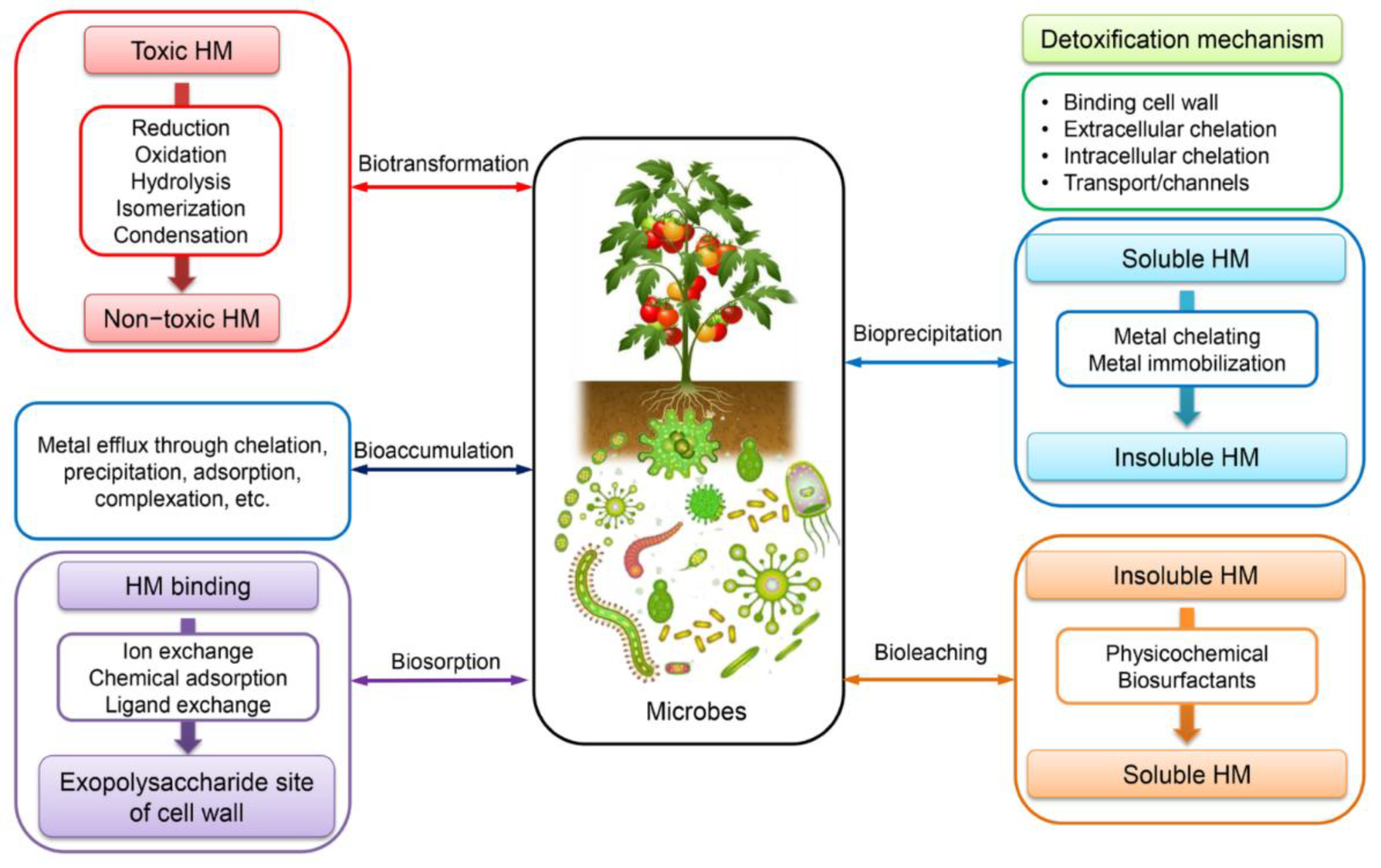

5. Pb Resistance Mechanisms: Summary

5.1. Efflux and Active Transport Systems

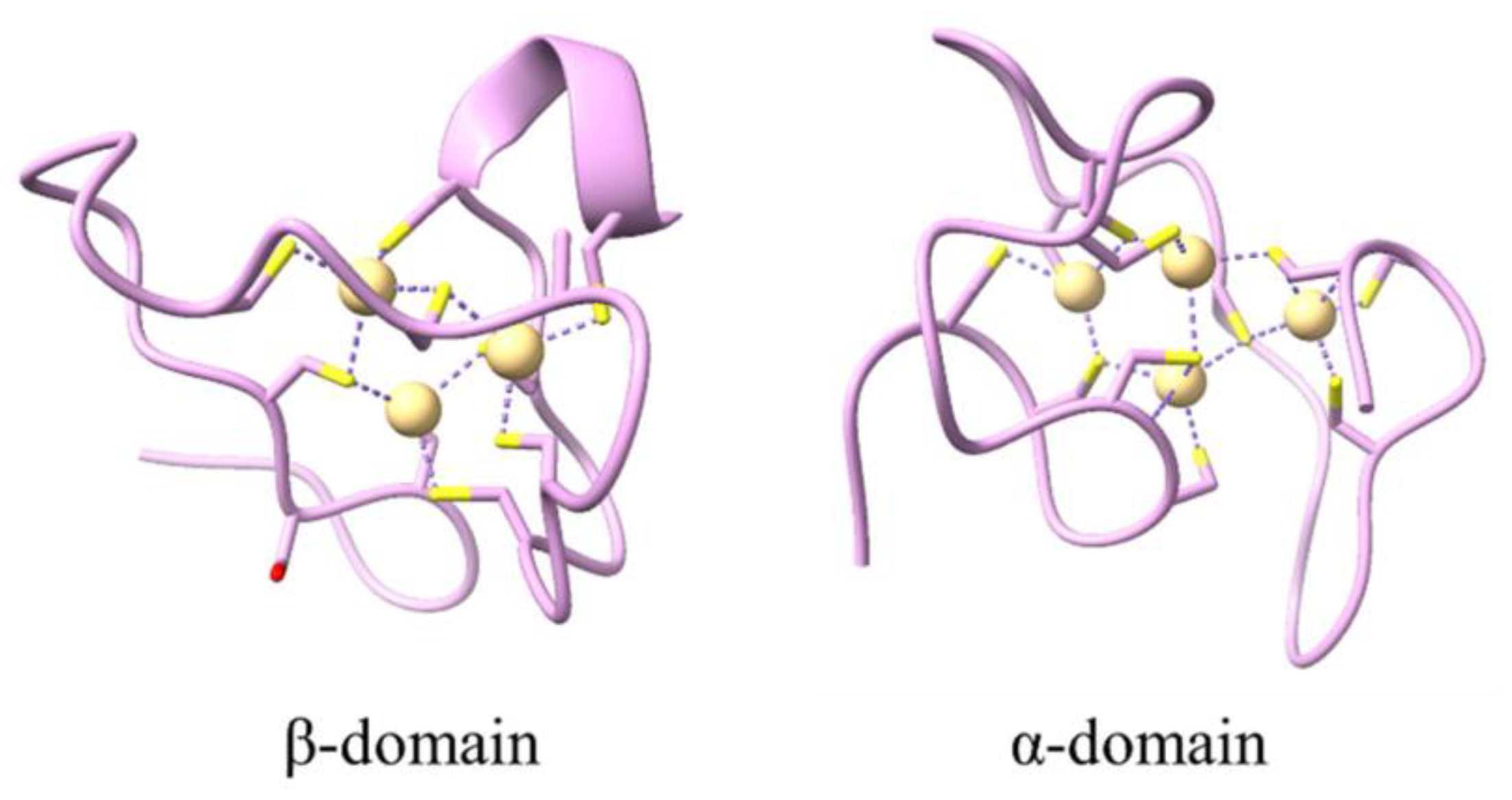

5.2. Metal Chelation and Sequestration

5.3. Biosorption and Surface Binding

5.4. Bioaccumulation and Intracellular Sequestration

5.5. Precipitation and Biotransformation

5.6. Morphological Adaptations

5.7. Genetic Regulation and Molecular Mechanisms

6. Methods for Pb Removal

6.1. From the Environment

6.1.1. Physical and Chemical Methods

6.1.1.1. Limestone-Based Adsorption

6.1.1.2. Nanotechnology Applications

6.1.2. Biological Remediation Methods

6.1.2.1. Microbial Bioremediation

6.1.2.2. Phytoremediation

6.1.3. Soil Amendment Strategies

6.1.4. Advanced Technologies

6.2. From the Human Body

7. Conclusion

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSHA | Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

| RND | Resistance-Nodulation-Division (family) |

| MICP | Microbially Induced Carbonate Precipitation |

| ZIP | ZRT-IRT-like Protein (family) |

| NRAMP | Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Protein |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization (of the United Nations) |

| GSH/MRP | Glutathione / Multidrug Resistance-associated Protein |

References

- Lead | Pb (Element) – PubChem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/element/Lead (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Gonzalez-Villalva, A.; Marcela, R.-L.; Nelly, L.-V.; Patricia, B.-N.; Guadalupe, M.-R.; Brenda, C.-T.; Maria Eugenia, C.-V.; Martha, U.-C.; Isabel, G.-P.; Fortoul, T.I. Lead Systemic Toxicity: A Persistent Problem for Health. Toxicology 2025, 515, 154163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, R.; Zilli Vieira, C.L.; Rosenbaum, M.H.; Bischoff, K.; Mordarski, D.C.; Brown, M.J. The Urban Lead (Pb) Burden in Humans, Animals and the Natural Environment. Environmental Research 2021, 193, 110377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satchanska, G. Toxicity of heavy metals and pesticides on the living world 2025, A Monograph, 103 pages.

- Soil contamination by heavy metals. Europa.eu. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/maps-and-charts/soil-contamination-by-heavy-metals (accessed 2025-07-08).

- Collin, M.S.; Venkatraman, S.K.; Vijayakumar, N.; Kanimozhi, V.; Arbaaz, S.M.; Stacey, R.G.S.; Anusha, J.; Choudhary, R.; Lvov, V.; Tovar, G.I.; et al. Bioaccumulation of Lead (Pb) and Its Effects on Human: A Review. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2022, 7, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkiewicz, A.E.; Backstrand, J.R. Lead Toxicity and Pollution in Poland. IJERPH 2020, 17, 4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericson, B.; Hu, H.; Nash, E.; Ferraro, G.; Sinitsky, J.; Taylor, M.P. Blood Lead Levels in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. The Lancet Planetary Health 2021, 5, e145–e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouida, L.; Rafatullah, M.; Kerrouche, A.; Qutob, M.; Alosaimi, A.M.; Alorfi, H.S.; Hussein, M.A. A Review on Cadmium and Lead Contamination: Sources, Fate, Mechanism, Health Effects and Remediation Methods. Water 2022, 14, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, M.J.; Toupal, J.; Caballero-Gómez, H.; McKeon, T.P.; Howarth, M.V.; Pepino, R.; Gieré, R. Lead Pollution, Demographics, and Environmental Health Risks: The Case of Philadelphia, USA. IJERPH 2021, 18, 9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgulat, J.; Łukasik, W.; Borgulat, A.; Nadgórska-Socha, A.; Kandziora-Ciupa, M. Influence of Lead on the Activity of Soil Microorganisms in Two Beskidy Landscape Parks. Environ Monit Assess 2021, 193, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukaiti, W.S.A.; Al Shuhoumi, M.A.; Balushi, H.I.A.; Faifi, M.A.; Kazzi, Z. Lead Poisoning Epidemiology, Challenges and Opportunities: First Systematic Review and Expert Consensuses of the MENA Region. Environmental Advances 2023, 12, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Ye, X. Detection Techniques for Lead Ions in Water: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, K.; Das, A.P. Lead Pollution: Impact on Environment and Human Health and Approach for a Sustainable Solution. Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology 2023, 5, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; M.M.S., C.-P.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Shabnam, A.A.; Subrahmanyam, G.; Mondal, R.; Gupta, D.K.; Malyan, S.K.; Kumar, S.S.; et al. Lead Toxicity: Health Hazards, Influence on Food Chain, and Sustainable Remediation Approaches. IJERPH 2020, 17, 2179. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Guan, H.; Tian, Z.-Q.; Chen, M.-M.; Tian, K.-K.; Zhao, F.-J.; Wang, P. Exposure Sources, Intake Pathways and Accumulation of Lead in Human Blood. Soil Security 2024, 15, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardila, P.A.R.; Alonso, R.Á.; Valsero, J.J.D.; García, R.M.; Cabrera, F.Á.; Cosío, E.L.; Laforet, S.D. Assessment of Heavy Metal Pollution in Marine Sediments from Southwest of Mallorca Island, Spain. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 16852–16866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mutairi, K.A.; Yap, C.K. A Review of Heavy Metals in Coastal Surface Sediments from the Red Sea: Health-Ecological Risk Assessments. IJERPH 2021, 18, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javid, A.; Nasiri, A.; Mahdizadeh, H.; Momtaz, S.M.; Azizian, M.; Javid, N. Determination and Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Air Dust Fall Particles. Environ Health Eng Manag 2021, 8, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Xu, C.; Kang, S.; Huo, A.; Lyu, J.; Zhou, M.; Nover, D. Heavy Metals in Water and Surface Sediments of the Fenghe River Basin, China: Assessment and Source Analysis. Water Science and Technology 2021, 84, 3072–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpara, E.C.; Fayemi, O.E.; Wojuola, O.B.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Ebenso, E.E. Electrochemical Detection of Selected Heavy Metals in Water: A Case Study of African Experiences. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 26319–26361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yang, M.; Lan, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, S.; Yang, Y.; Ru, J. Water Quality Degradation Due to Heavy Metal Contamination: Health Impacts and Eco-Friendly Approaches for Heavy Metal Remediation. Toxics 2023, 11, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalwick, J.A.; Ratelle, M.; Gurney, K.E.B.; Drysdale, M.; Lazarescu, C.; Comte, J.; Laird, B.; Skinner, K. Sources of Exposure to Lead in Arctic and Subarctic Regions: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 2023, 82, 2208810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyebi, O.D.; Lebbie, T.; Carpenter, D.O. Standards for Levels of Lead in Soil and Dust around the World. Reviews on Environmental Health 2025, 40, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briffa, J.; Sinagra, E.; Blundell, R. Heavy Metal Pollution in the Environment and Their Toxicological Effects on Humans. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadheesh, S.; Malathi, R.; Arundhathi; Rino, M.A.; Swetha, R. Monitoring and Analyzing the Effect of Heavy Metals in Air Based on Ecological and Health Risks in Coimbatore. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1125, 012002. [CrossRef]

- EUR-Lex - 32023R0915 - EN - EUR-Lex. Europa.eu. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32023R0915. (accessed on 07 July 2025).

- EUR-Lex - 32020L2184 - EN - EUR-Lex. Europa.eu. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32020L2184. (accessed on 07 July 2025).

- Vieira, D.C.S.; Yunta, F.; Baragaño, D.; Evrard, O.; Reiff, T.; Silva, V.; de la Torre, A.; Zhang, C.; Panagos, P.; Jones, A.; Wojda, P. Soil Pollution in the European Union – an Outlook. Environmental Science & Policy 2024, 161, 103876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU air quality standards. environment.ec.europa.eu. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/air/air-quality/eu-air-quality-standards_en. (accessed on 07 July 2025).

- Angon, P.B.; Islam, Md.S.; Kc, S.; Das, A.; Anjum, N.; Poudel, A.; Suchi, S.A. Sources, Effects and Present Perspectives of Heavy Metals Contamination: Soil, Plants and Human Food Chain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, H. Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils: Sources, Influencing Factors, and Remediation Strategies. Toxics 2024, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellows, K.M.; Samy, S.; Whittaker, S.G. Evaluating Metal Cookware as a Source of Lead Exposure. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2025, 35, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkan, M.F. Lead: Natural Occurrence, Toxicity to Organisms and Bioremediation by Lead-Degrading Bacteria: A Comprehensive Review. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 17, 1298–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta, I.; Lemon, J.; Gadaj, A.; Cretescu, I.; Stef, D.; Pet, I.; Stef, L.; McCleery, D.; Douglas, A.; Corcionivoschi, N. The Interplay between Antimicrobial Resistance, Heavy Metal Pollution, and the Role of Microplastics. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1550587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elnabi, M.K.; Elkaliny, N.E.; Elyazied, M.M.; Azab, S.H.; Elkhalifa, S.A.; Elmasry, S.; Mouhamed, M.S.; Shalamesh, E.M.; Alhorieny, N.A.; Abd Elaty, A.E.; et al. Toxicity of Heavy Metals and Recent Advances in Their Removal: A Review. Toxics 2023, 11, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Mao, H.; Yang, X.; Zhao, W.; Sheng, L.; Sun, S.; Du, X. Resilience Mechanisms of Rhizosphere Microorganisms in Lead-Zinc Tailings: Metagenomic Insights into Heavy Metal Resistance. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2025, 292, 117956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnaji, N.D.; Anyanwu, C.U.; Miri, T.; Onyeaka, H. Mechanisms of Heavy Metal Tolerance in Bacteria: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidova, S.; Milushev, V.; Satchanska, G. The Mechanisms of Cadmium Toxicity in Living Organisms. Toxics 2024, 12, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizabeth George, S.; Wan, Y. Microbial Functionalities and Immobilization of Environmental Lead: Biogeochemical and Molecular Mechanisms and Implications for Bioremediation. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 457, 131738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, L.; Liu, C.; Bai, X.; Xu, C.; An, F.; Sun, F. Isolating and Identifying One Strain with Lead-Tolerant Fungus and Preliminary Study on Its Capability of Biosorption to Pb2+. Biology 2024, 13, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titilawo, M.A.; Ajani, T.F.; Adedapo, S.A.; Akinleye, G.O.; Ogunlana, O.E.; Aderibigbe, D. Evaluation of Lead Tolerance and Biosorption Characteristics of Fungi from Dumpsite Soils. Discov Environ 2023, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, R. Role of White Rot Fungi in Sustainable Remediation of Heavy Metals from the Contaminated Environment.

- Feng, C.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Li, K.; Luo, K.; Liao, X.; Liu, T. Characterization and Mechanism of Lead and Zinc Biosorption by Growing Verticillium Insectorum J3. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.-M.; Gu, S.-Y.; Kim, D.-J.; Shin, H.-C.; Hong, K.-S.; Kim, Y.-K. Arsenic, Cadmium, Lead, and Mercury Contents of Mushroom Species in Korea and Associated Health Risk. International Journal of Food Properties 2020, 23, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muszyńska, B.; Rojowski, J.; Łazarz, M.; Kała, K.; Dobosz, K.; Opoka, W. The Accumulation and Release of Cd and Pb from Edible Mushrooms and Their Biomass. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 27, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałgowska, M.; Pietrzak-Fiećko, R. Cadmium and Lead Content in Selected Fungi from Poland and Their Edible Safety Assessment. Molecules 2021, 26, 7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucurica, I.A.; Dulama, I.D.; Radulescu, C.; Banica, A.L.; Stanescu, S.G. Heavy Metals and Associated Risks of Wild Edible Mushrooms Consumption: Transfer Factor, Carcinogenic Risk, and Health Risk Index. JoF 2024, 10, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orywal, K.; Socha, K.; Nowakowski, P.; Zoń, W.; Kaczyński, P.; Mroczko, B.; Łozowicka, B.; Perkowski, M. Health Risk Assessment of Exposure to Toxic Elements Resulting from Consumption of Dried Wild-Grown Mushrooms Available for Sale. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Dwivedi, V.; Kumar, S.; Patel, A.; Niazi, P.; Yadav, V.K. Lead Toxicity in Plants: Mechanistic Insights into Toxicity, Physiological Responses of Plants and Mitigation Strategies. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2024, 19, 2365576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ur Rahman, S.; Qin, A.; Zain, M.; Mushtaq, Z.; Mehmood, F.; Riaz, L.; Naveed, S.; Ansari, M.J.; Saeed, M.; Ahmad, I.; et al. Pb Uptake, Accumulation, and Translocation in Plants: Plant Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Response: A Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, S.; Baskar, A.; Geevarghese, D.M.; Ali, M.N.V.S.; Bahubali, P.; Choudhary, R.; Lvov, V.; Tovar, G.I.; Senatov, F.; Koppala, S.; et al. Bioaccumulation of Lead (Pb) and Its Effects in Plants: A Review. Journal of Hazardous Materials Letters 2022, 3, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Niu, Y.; Xing, L.; Liang, Z.; Song, X.; Ding, M.; Huang, W. Research Progress of the Detection and Analysis Methods of Heavy Metals in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1310328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Bejarano, P.I.; Puente-Rivera, J.; Cruz-Ortega, R. Metal and Metalloid Toxicity in Plants: An Overview on Molecular Aspects. Plants 2021, 10, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alengebawy, A.; Abdelkhalek, S.T.; Qureshi, S.R.; Wang, M.-Q. Heavy Metals and Pesticides Toxicity in Agricultural Soil and Plants: Ecological Risks and Human Health Implications. Toxics 2021, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskelu, T.; Senbeta, A.F.; Keneni, Y.G.; Sime, G. Heavy Metal Accumulation and Food Safety of Lettuce ( Lactuca Sativa L.) Amended by Bioslurry and Chemical Fertilizer Application. Food Science & Nutrition 2024, 12, 7449–7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleophas, F.N.; Zahari, N.Z.; Murugayah, P.; Rahim, S.A.; Mohd Yatim, A.N. Phytoremediation: A Novel Approach of Bast Fiber Plants (Hemp, Kenaf, Jute and Flax) for Heavy Metals Decontamination in Soil—Review. Toxics 2022, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elik, Ü.; Gül, Z. Accumulation Potential of Lead and Cadmium Metals in Maize (Zea Mays L.) and Effects on Physiological-Morphological Characteristics. Life 2025, 15, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Yuan, M.; Huang, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Duan, C. Effects of Heavy Metals on Stomata in Plants: A Review. IJMS 2023, 24, 9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, U.; Khan, S.M.; Khalid, N.; Ahmad, Z.; Jehangir, S.; Fatima Rizvi, Z.; Lho, L.H.; Han, H.; Raposo, A. Detoxifying the Heavy Metals: A Multipronged Study of Tolerance Strategies against Heavy Metals Toxicity in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1154571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sappah, A.H.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Chen, B.; Soaud, S.A.; Abd Elhamid, M.A.; Yan, K.; Li, J.; El-Tarabily, K.A. Plants’ Molecular Behavior to Heavy Metals: From Criticality to Toxicity. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1423625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.U.; Nawaz, M.F.; Gul, S.; Yasin, G.; Hussain, B.; Li, Y.; Cheng, H. State-of-the-Art OMICS Strategies against Toxic Effects of Heavy Metals in Plants: A Review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2022, 242, 113952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasani, E.; Giannelli, G.; Varotto, S.; Visioli, G.; Bellin, D.; Furini, A.; DalCorso, G. Epigenetic Control of Plant Response to Heavy Metals. Plants 2023, 12, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monchanin, C.; Devaud, J.-M.; Barron, A.B.; Lihoreau, M. Current Permissible Levels of Metal Pollutants Harm Terrestrial Invertebrates. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 779, 146398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oros, A. Bioaccumulation and Trophic Transfer of Heavy Metals in Marine Fish: Ecological and Ecosystem-Level Impacts. JoX 2025, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monclús, L.; Shore, R.F.; Krone, O. Lead Contamination in Raptors in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 748, 141437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarova, I.; Balieva, G. Effects of Lead Exposure in Wild Birds as Causes for Incidents and Fatal Injuries. Diversity 2025, 17, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajargah, M.F.; Azar, H. Investigating the Effects of Accumulation of Lead and Cadmium Metals in Fish and Its Impact on Human Health. JAMB 2023, 12, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, I.; Alkheraije, K.A. A Review of Important Heavy Metals Toxicity with Special Emphasis on Nephrotoxicity and Its Management in Cattle. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1149720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartorius, A.; Johnson, M.F.; Young, S.; Bennett, M.; Baiker, K.; Edwards, P.; Yon, L. Trace Metal Accumulation through the Environment and Wildlife at Two Derelict Lead Mines in Wales. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirinos-Peinado, D.; Castro-Bedriñana, J.; Ríos-Ríos, E.; Mamani-Gamarra, G.; Quijada-Caro, E.; Huacho-Jurado, A.; Nuñez-Rojas, W. Lead and Cadmium Bioaccumulation in Fresh Cow’s Milk in an Intermediate Area of the Central Andes of Peru and Risk to Human Health. Toxics 2022, 10, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.I.; Khan, Z.I.; Ahmad, K.; Naeem, M.; Ali, M.A.; Elshikh, M.S.; Zaman, Q.U.; Iqbal, K.; Muscolo, A.; Yang, H.-H. Toxicity and Bioassimilation of Lead and Nickel in Farm Ruminants Fed on Diversified Forage Crops Grown on Contaminated Soil. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 283, 116812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, A.S.M. Heavy Metal Toxicity in Poultry: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1161354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan Emami, M.; Saberi, F.; Mohammadzadeh, S.; Fahim, A.; Abdolvand, M.; Ali Ehsan Dehkordi, S.; Mohammadzadeh, S.; Maghool, F. A Review of Heavy Metals Accumulation in Red Meat and Meat Products in the Middle East. Journal of Food Protection 2023, 86, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Heavy Metals: Toxicity and Human Health Effects. Arch Toxicol 2025, 99, 153–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali-Mood, M.; Naseri, K.; Tahergorabi, Z.; Khazdair, M.R.; Sadeghi, M. Toxic Mechanisms of Five Heavy Metals: Mercury, Lead, Chromium, Cadmium, and Arsenic. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 643972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mititelu, M.; Neacșu, S.M.; Busnatu, Ștefan, S.; Scafa-Udriște, A.; Andronic, O.; Lăcraru, A.-E.; Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Lupuliasa, D.; Negrei, C.; Olteanu, G. Assessing Heavy Metal Contamination in Food: Implications for Human Health and Environmental Safety. Toxics 2025, 13, 333. [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, D.; Słowik, J.; Chilicka, K. Heavy Metals and Human Health: Possible Exposure Pathways and the Competition for Protein Binding Sites. Molecules 2021, 26, 6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewski, G.; Klik, B.K.; Rogula-Kozłowska, W.; Rogula-Kopiec, P.; Rybak, J.; Radziemska, M.; Liniauskienė, E. Assessment of Heavy Metal Inhalation Risks in Urban Environments in Poland: A Case Study. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshakhlagh, A.H.; Ghobakhloo, S.; Gruszecka-Kosowska, A. Inhalational Exposure to Heavy Metals: Carcinogenic and Non-Carcinogenic Risk Assessment. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2024, 16, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scutarașu, E.C.; Trincă, L.C. Heavy Metals in Foods and Beverages: Global Situation, Health Risks and Reduction Methods. Foods 2023, 12, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bair, E.C. A Narrative Review of Toxic Heavy Metal Content of Infant and Toddler Foods and Evaluation of United States Policy. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 919913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeier, R.T.; Maier, A.; Reichard, J.F. Rapid Review of Dermal Penetration and Absorption of Inorganic Lead Compounds for Occupational Risk Assessment. Annals of Work Exposures and Health 2022, 66, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, H.; Mehmood, M.Z.; Shah, M.H.; Abbasi, A.M. Evaluation of Heavy Metals in Cosmetic Products and Their Health Risk Assessment. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2020, 28, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oginawati, K.; Suharyanto; Susetyo, S.H.; Sulung, G.; Muhayatun; Chazanah, N.; Dewi Kusumah, S.W.; Fahimah, N. Investigation of Dermal Exposure to Heavy Metals (Cu, Zn, Ni, Al, Fe and Pb) in Traditional Batik Industry Workers. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08914. [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, E.; Barregard, L.; Sallsten, G.; Fagerberg, B.; Engström, G.; Fagman, E.; Forsgard, N.; Lundh, T.; Bergström, G.; Harari, F. Exposure to Lead and Coronary Artery Atherosclerosis: A Swedish Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study. JAHA 2025, 14, e037633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucera, S.; Serra, M.; Caminiti, R.; Ruga, S.; Passacatini, L.C.; Macrì, R.; Scarano, F.; Maiuolo, J.; Bulotta, R.; Mollace, R.; et al. Non-Essential Heavy Metal Effects in Cardiovascular Diseases: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1332339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, P.; Tang, M.; Fan, H.; Hao, J. Chronic Lead Exposure and Burden of Cardiovascular Disease during 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1367681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman-Cribbin, W.; Li, Z.; Lewin, M.; Ruiz, P.; Jarrett, J.M.; Cole, S.A.; Kupsco, A.; O’Leary, M.; Pichler, G.; Shimbo, D.; et al. The Contribution of Declines in Blood Lead Levels to Reductions in Blood Pressure Levels: Longitudinal Evidence in the Strong Heart Family Study. JAHA 2024, 13, e031256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, D.; Wen, X.; Guan, X.; Fang, H.; Liu, Y.; Qin, M.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Lv, J.; Zhao, J.; et al. Pubertal Lead Exposure Affects Ovary Development, Folliculogenesis and Steroidogenesis by Activation of IRE1α-JNK Signaling Pathway in Rat. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2023, 257, 114919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osowski, A.; Fedoniuk, L.; Bilyk, Y.; Fedchyshyn, O.; Sas, M.; Kramar, S.; Lomakina, Y.; Fik, V.; Chorniy, S.; Wojtkiewicz, J. Lead Exposure Assessment and Its Impact on the Structural Organization and Morphological Peculiarities of Rat Ovaries. Toxics 2023, 11, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliche, K.A.; Umeoguaju, F.U.; Ikewuchi, C.; Diorgu, F.C.; Ajao, O.; Frazzoli, C.; Orisakwe, O.E. Paternal Lead Exposure and Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environmental Health Insights 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giulioni, C.; Maurizi, V.; De Stefano, V.; Polisini, G.; Teoh, J.Y.-C.; Milanese, G.; Galosi, A.B.; Castellani, D. The Influence of Lead Exposure on Male Semen Parameters: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reproductive Toxicology 2023, 118, 108387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-L.; Yang, W.-Y.; Hara, A.; Asayama, K.; Roels, H.A.; Nawrot, T.S.; Staessen, J.A. Public and Occupational Health Risks Related to Lead Exposure Updated According to Present-Day Blood Lead Levels. Hypertens Res 2023, 46, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcala, C.S.; Lane, J.M.; Midya, V.; Eggers, S.; Wright, R.O.; Rosa, M.J. Exploring the Link between the Pediatric Exposome, Respiratory Health, and Executive Function in Children: A Narrative Review. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1383851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskabady, M.; Marefati, N.; Farkhondeh, T.; Shakeri, F.; Farshbaf, A.; Boskabady, M.H. The Effect of Environmental Lead Exposure on Human Health and the Contribution of Inflammatory Mechanisms, a Review. Environment International 2018, 120, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Liu, C.; Yang, M. The Association between Urinary Lead Concentration and the Likelihood of Kidney Stones in US Adults: A Population-Based Study. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, K.; Viramgami, A.; Bagepally, B.S.; Balachandar, R. Association between Chronic Lead Exposure and Markers of Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Toxicology Reports 2024, 13, 101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, J. Association of Urinary and Blood Lead Concentrations with All-Cause Mortality in US Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 23230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.-F.; Huang, Y.-T.; Chuang, M.-H.; Jiang, M.-Y. Association of Low-Level Heavy Metal Exposure with Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease and Long-Term Mortality. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, S.; Geetha, P.; Kyriazis, P.; Specht, A.; Hu, H.; Danziger, J. Association of Environmental Lead Toxicity and Hematologic Outcomes in Patients with Advanced Kidney Disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2023, 38, 1337–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Li, M.; Wen, X.; Deng, F.; Hou, X.; Zou, Q.; Liu, H.; Fan, X.; Han, J. Epidemiological Trends in the Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease Due to Lead Exposure in China from 1990 to 2021 Compared to Global, and Projections until 2050. International Journal of Environmental Health Research 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battistini, B.; Greggi, C.; Visconti, V.V.; Albanese, M.; Messina, A.; De Filippis, P.; Gasperini, B.; Falvino, A.; Piscitelli, P.; Palombi, L.; et al. Metals Accumulation Affects Bone and Muscle in Osteoporotic Patients: A Pilot Study. Environmental Research 2024, 250, 118514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, R.; Jin, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, X.; Lu, X. The Influence of Adult Urine Lead Exposure on Bone Mineral Densit: NHANES 2015-2018. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1412872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Xiao, P.; Hu, B.; Ma, Y.; Fan, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhou, F.; Zhuang, Y. Blood Lead Level Is Negatively Associated With Bone Mineral Density in U.S. Children and Adolescents Aged 8-19 Years. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 928752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabihi, A.; Mehrpour, O.; Nakhaee, S.; Atabati, E. Lead Poisoning and Its Effects on Bone Density. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 15619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozichahak, A.; Rahimnejad, S.; Rahmani, A.; Parvizimehr, A.; Aghaei, A.; Rahimpoor, R. Effect of Occupational Exposure to Lead on Serum Levels of Lipid Profile and Liver Enzymes: An Occupational Cohort Study. Toxicology Reports 2022, 9, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Lin, H.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, J.; Li, D. Lead Exposure Was Associated with Liver Fibrosis in Subjects without Known Chronic Liver Disease: An Analysis of NHANES 2017–2020. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 995795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerasarntipan, T.; Chaiteerakij, R.; Prueksapanich, P.; Werawatganon, D. Changes in Inflammatory Cytokines, Antioxidants and Liver Stiffness after Chelation Therapy in Individuals with Chronic Lead Poisoning. BMC Gastroenterol 2020, 20, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renu, K.; Chakraborty, R.; Myakala, H.; Koti, R.; Famurewa, A.C.; Madhyastha, H.; Vellingiri, B.; George, A.; Valsala Gopalakrishnan, A. Molecular Mechanism of Heavy Metals (Lead, Chromium, Arsenic, Mercury, Nickel and Cadmium) - Induced Hepatotoxicity – A Review. Chemosphere 2021, 271, 129735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Tian, F.; Narbad, A.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W. Lead-Induced Gut Injuries and the Dietary Protective Strategies: A Review. Journal of Functional Foods 2021, 83, 104528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Ortega, D.; González Esquivel, D.F.; Blanco Ayala, T.; Pineda, B.; Gómez Manzo, S.; Marcial Quino, J.; Carrillo Mora, P.; Pérez De La Cruz, V. Cognitive Impairment Induced by Lead Exposure during Lifespan: Mechanisms of Lead Neurotoxicity. Toxics 2021, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alva, S.; Parithathvi, A.; Harshitha, P.; Dsouza, H.S. Influence of Lead on cAMP-Response Element Binding Protein (CREB) and Its Implications in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Toxicology Letters 2024, 400, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundacker, C.; Forsthuber, M.; Szigeti, T.; Kakucs, R.; Mustieles, V.; Fernandez, M.F.; Bengtsen, E.; Vogel, U.; Hougaard, K.S.; Saber, A.T. Lead (Pb) and Neurodevelopment: A Review on Exposure and Biomarkers of Effect (BDNF, HDL) and Susceptibility. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 2021, 238, 113855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, T.; Liu, Y.; Buchner, V.; Tchounwou, P.B. Neurotoxic Effects and Biomarkers of Lead Exposure: A Review. Reviews on Environmental Health 2009, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Park, M.Y.; Kang, M.-Y.; Shin, I.-S.; An, S.; Kim, H.-R. Occupational Lead Exposure and Brain Tumors: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. IJERPH 2020, 17, 3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, L.; Dapar, M.L.G.; Zhang, Q. Novel Plasma Cytokines Identified and Validated in Children during Lead Exposure According to the New Updated BLRV. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 30323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukanha, K.; Yimthiang, S.; Kwanhian, W. The Immunotoxicity of Chronic Exposure to High Levels of Lead: An Ex Vivo Investigation. Toxics 2020, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Ye, T.; Jiang, H.; Wang, A.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Xie, H.; Meng, H.; Shen, C.; Ding, X. Panoramic Lead-Immune System Interactome Reveals Diversified Mechanisms of Immunotoxicity upon Chronic Lead Exposure. Cell Biol Toxicol 2025, 41, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harshitha, P.; Bose, K.; Dsouza, H.S. Influence of Lead-Induced Toxicity on the Inflammatory Cytokines. Toxicology 2024, 503, 153771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgolini, M.B.; Aschner, M. Molecular Mechanisms of Lead Neurotoxicity. In Advances in Neurotoxicology; Elsevier, 2021; Vol. 5, pp. 159–213 ISBN 978-0-12-823775-5.

- Han, Q.; Zhang, W.; Guo, J.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, H.; Xia, Y.; Zhu, G. Mitochondrion: A Sensitive Target for Pb Exposure. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2021, 46, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, H.; Kamogashira, T.; Yamasoba, T. Heavy Metal Exposure: Molecular Pathways, Clinical Implications, and Protective Strategies. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlubek, M.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I. Selected Functions and Disorders of Mitochondrial Metabolism under Lead Exposure. Cells 2024, 13, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmaphan, S.; Bordeerat, N.K. Genotoxic Effects of Lead and Their Impact on the Expression of DNA Repair Genes. IJERPH 2022, 19, 4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Liu, G.; Zhao, B.; He, Z.; Gu, S. Emerging Roles of Epigenetics in Lead-Induced Neurotoxicity. Environment International 2023, 181, 108253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, P.; Misra, S.; Sharma, P. Epigenetics in Lead Toxicity: New Avenues for Future Research. Ind J Clin Biochem 2021, 36, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Roshani, D.; Gao, B.; Li, P.; Shang, N. Metallothionein: A Comprehensive Review of Its Classification, Structure, Biological Functions, and Applications. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, U.; Farooq, M.; Hussain, S.; Maqsood, M.; Hussain, M.; Ishfaq, M.; Ahmad, M.; Anjum, M.Z. Lead Toxicity in Plants: Impacts and Remediation. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 250, 109557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, C.; Alam, N.; Tamang, A.; Chattopadhyay, B. Removal of Lead Contamination through the Formation of Lead-Nanoplates by a Hot Spring Microbial Protein. AiM 2021, 11, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, A.T.; Moneim, M.A.; Ahmed, E.A.; El-Ayaat, A.M.; Dardir, F.M. Effective Removal of Heavy Metal Ions (Pb, Cu, and Cd) from Contaminated Water by Limestone Mine Wastes. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Xie, J.; Mirshahghassemi, S.; Lead, J. Metal (Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb) Removal from Environmentally Relevant Waters Using Polyvinylpyrrolidone-Coated Magnetite Nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 3266–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Atomic number Atomic weight Atomic radius Electronic configuration Melting point Boiling point Density at 20 °C Reduction potential Pb²⁺ + 2e⁻ → Pb(s) Heat of fusion Heat of vaporization Electronegativity (Pauling scale) First ionization energy Second ionization energy |

82 207.2 u 180 pm (Empirical) [Xe]6s²4f¹⁴5d¹⁰6p² 327.46 °C 1749 °C 11.342 g/cm³ −0.126 V 4.77 kJ/mol 179.5 kJ/mol 2.33 7.417 eV 15.03 eV |

| Sample | Lead Concentration Range |

|---|---|

| Urban soil, Klang district, Selangor | 52.7 |

| Soil from the mango plantation area, Perlis | 0.4 |

| Surface soils from iron ore mining sites, Kuala Lipis, Pahang | 63.5–72.5 |

| Grassland, arable land, forest, wasteland, Malopolska, Poland | 3-586 |

| Average concentration of heavy metals in the Earth's crust | 12.5 |

| Dust fall particles, Zarand, Iran | 1.01 |

| Road dust, Delhi city, India | 128.7 |

| Red Sea (North), Gulf of Aqaba | 96.67 |

| Red Sea (North), Hurghada City | 53 |

| Metric | Pb | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Food | 0.01-3 mg/kg | [27] |

| Drinking water | 5 µg/L | [28] |

| Soil | 50–300 mg/kg | [29] |

| Air | 0.5 µg/m3 | [30] |

| Food Type | Country | Concentration (μg/kg or μg/L) | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRUITS | Grape white varieties | Croatia | 0.001–0.021 | 2008 |

| Grape red varieties | Croatia | 0.002–0.039 | 2008 | |

| Banana | Bangladesh | 3 | 2016 | |

| Mango | Bangladesh | 642 | 2016 | |

| Apples | Kosovo | 1490–2170 | 2019 | |

| Apples | Ukraine | 1347–3886 | 2021 | |

| VEGETABLES | Lettuce | Romania | 820–2220 | 2021 |

| Tomato | Romania | 0.7–0.8 | 2023 | |

| Potato | China | 67 | 2009 | |

| Potato | Bangladesh | 7 | 2016 | |

| White potato | Romania | 300–400 | 2021 | |

| Red potato | Romania | 370–1030 | 2021 | |

| Onion | Romania | 160–180 | 2021 | |

| Carrot | Romania | 540–940 | 2021 | |

| Beans | Romania | 80–520 | 2021 | |

| Soybean | Monte Carlo | 33–70 | 2022 | |

| Grain, maize | China | 20–13 | 2015 | |

| MEATS | Pork meat products | Italy | 220–380 | 2020 |

| Pork | Italy | 0.024 | 2020 | |

| Bacon | Romania | 580 | 2014 | |

| Ham | Romania | 650 | 2014 | |

| Salami | Romania | 210 | 2014 | |

| Sausages | Romania | 820 | 2014 | |

| Red meat | Asia | 605–1435 | 2023 | |

| Red meat | Africa | 840–1094 | 2023 | |

| Beef | Italy | 0.019 | 2020 | |

| Mutton meat | China (Beijing) | 128 | 2019 | |

| DAIRY | Milk | Monte Carlo | 550 | 2023 |

| Milk | Turkey | 0.85 | 2023 | |

| Milk | Tanzania | 263 | 2023 | |

| Raw cow milk | Turkey | 16.7 | 2012 | |

| Raw cow milk | Egypt | 101.6 | 2023 | |

| Sheep and goat milk | Italy | 0.002 | 2020 | |

| Milk and dairy products | Egypt | 0.044–0.751 | 2014 | |

| Full-fat UHT milk | Cyprus | 2.66 | 2021 | |

| Full-fat yogurt | Cyprus | 3 | 2021 | |

| Halloumi cheese | Cyprus | 35.3 | 2021 | |

| OILS | Corn oil | Iran | 99 | 2020 |

| Olive oil | London | 143 | 2022 | |

| Olive oil | Pakistan | 4285 | 2022 | |

| Rapeseed oil | China | 1960 | 2016 | |

| Rapeseed oil | Poland | 56 | 2017 | |

| Coconut oil | London | 158 | 2022 | |

| Sesame oil | Pakistan | 4005 | 2022 | |

| Sesame oil | Korea | 36 | 2019 | |

| Sunflower oil | London | 274 | 2022 | |

| Sunflower oil | Iran | 99 | 2020 | |

| Flaxseed oil | Korea | 25.7 | 2019 | |

| DRINKS | Beer | Ethiopia | 6 | 2022 |

| Beer | Brazil | 13–33 | 2005 | |

| Muscat Ottonel | Romania | 2.5–632 | 2017 | |

| low-alcoholic Muscat Ottonel | Romania | 67–575 | 2017 | |

| White wine | Croatia | 30 | 2008 |

| Effect | Concentration | Exposure time | Biological models | Mode of action | The outcome of treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative stress | Lead acetate (Pb 0.2%) | 5 weeks | Rat | Upregulating the transcription process of the cyclooxygenase-2 gene | Oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation |

| Ultrastructural changes | 0.13% lead acetate | 4–8 weeks | Adult albino rats | Megalocytosis complex III of the respiratory chain affected | Nuclear pyknosis, juxtanuclear inclusion bodies |

| Cholesterol functions of the liver | Lead acetate (500 mg Pb/L) | 10-11 weeks | Male Wistar rats | Inhibition of the activity of HMGR and decrease in the expression of cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) genes | reduction of metabolism of cholesterol, increase in plasma cholesterol levels |

| Metabolic functions | Lead acetate or lead nitrate (20 mg/kg) | 4 weeks | Swiss albino male mice | Reduced enzymatic activity of glucose-6-phosphatase (G6PASE) | pyruvic acid content was increased, disruption in glycogen related mechanisms |

| Hepatic hyperplasia | Lead acetate trihydrate | 4-52 weeks | Wistar Albino Rats | Increase in the activity of DNA polymerase-β, Protein kinase C alpha (PKC-α) overexpression, suppression of the mRNA of the CYP1A2 gene, increased production of TNF-α | hyperplasia of Kupffer cells, oxidative stress of the hepatocytes |

| Cell death | Lead acetate, 1 mg/ml | 1 week | Female mice | Overexpression of apoptotic markers like Bax, Caspase 8, Caspase 3 | Apoptosis, Oxidative stress |

| Microbial Biosorbent | pH | Temperature (°C) | Time (h) | Initial Metal Ion Concentration (mg/L) | Sorption Capacity (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterobacter cloacae | 8 | 40 | 72 | 400 | 172 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 7.5 | 40 | 24 | 50 | 40 |

| Micrococcus luteus | - | 27 | 48 | 272 | 1965 |

| Aspergillus niger | 4.5 | 30 | 72 | 100 | 34.4 |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 4 | 30 | 48 | 100 | 35 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 8 | 60 | 6 | 98.25 | 80 |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | 6 | 20 | 1 | 100 | 88.16 |

| Botrytis cinerea | 4 | 25 | 1.5 | 350 | 107.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).