1. Introduction

Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is caused by the flagellated protozoan

Trypanosoma cruzi. Although it was first described more than a century ago, this illness still remains a major public health problem affecting more than 7 million people worldwide, with severe morbidity and leading to more than 10,000 deaths every year. Chagas is endemic in 21 countries in Latin America, but in the last decades it has acquired increasing global relevance due to migration patterns. Transmission occurs primarily through direct contact with feces of infected blood-sucking triatomine vector bugs or through ingestion of contaminated food. Alternative routes independent of the insect vector include congenital, transfusional and transplant-associated, which are of major concern in non-endemic regions. The clinical course of the disease is typically divided into an acute and a chronic phase. The acute phase, often asymptomatic or presenting nonspecific symptoms such as fever and lymphadenopathy, is followed by a lifelong chronic infection. Most individuals remain in an indeterminate asymptomatic form, but without early diagnosis and treatment, approximately 30% progress to clinically evident chronic Chagas disease, primarily characterized by cardiomyopathy, although gastrointestinal forms can also occur. Trypanocide treatment with the currently available drugs—Benznidazole and Nifurtimox—aims to eliminate the parasite from the body to prevent the establishment or progression of visceral damage, mainly cardiac and/or digestive. Remarkably, it helps interrupt vertical transmission when administered to women of childbearing age and, if treatment is initiated early in the acute phase, Chagas disease can be cured. In contrast, during the chronic phase, treatment may help slow disease progression and reduce the risk of transmission, but are generally unable to achieve complete cure [

1,

2].

The clinical manifestations -both in the acute and chronic phases- and the evolution of the disease are highly variable and difficult to predict, reflecting the complex interplay between parasite, host and environmental factors. There is still ongoing debate about the specific roles of parasite genotype and host immunological factors in the progression and prognosis of Chagas disease. Furthermore, the significant variability in infection outcomes among individuals remains largely unexplained [

3,

4].

A key feature of

T. cruzi is its remarkable genetic diversity and the associated phenotypic characteristics. The parasite is currently classified into seven discrete typing units (DTUs): TcI to TcVI and TcBat. These DTUs differ in geographic distribution, reservoir associations, susceptibility to drugs, tissue tropism, and virulence. Infections with different DTUs have been associated with distinct clinical manifestations and disease outcomes [

3,

4,

5]. For instance, TcI is widespread and prevalent in northern South America, Central America, and sylvatic cycles, often linked to cardiac forms of the disease. TcII, TcV, and TcVI are more common in the Southern Cone and have been associated with severe chronic cardiomyopathy and digestive syndromes. TcIII and TcIV are mostly sylvatic and less commonly implicated in human disease. TcBat, initially identified in bats, appears to be restricted to sylvatic cycles and has not been clearly associated with human infection [

4,

6]. This genetic diversity of

T. cruzi is suspected to have an impact on the susceptibility to drugs, although additional factors linked to the life history trait of each strain might also impact the response to therapeutic agents [

7].

As with other human infectious diseases, animal models play a crucial role in helping researchers to understand Chagas Disease and develop new prevention and treatment approaches. Experimental models using different

T. cruzi strains have provided valuable insights into pathogenesis. However, due to the huge genetic and phenotypic diversity of

T. cruzi and the variability in clinical manifestation and outcomes, generalizations must be cautious [

8].

In this study, we characterized a murine infection model using the T. cruzi Dm28c strain, in BALB/c mice. Dm28c strain is classified within DTU TcI and has the capacity to establish chronic infection in mice with low to moderate virulence. The BALB/c mouse, with its well-characterized immune profile, provides a complementary model to study host behavior.

Because of the low to moderate virulence, the Dm28c-infection model allows the study of the disease progression through the acute to chronic phase.

2. Materials and Methods

Mice, parasites, and infection

BALB/c male mice (6–8 weeks old) were obtained and maintained at the animal facilities of the Centro de Investigación y Producción de Reactivos Biológicos (CIPReB-FCM-UNR, Argentina). Mice were housed in ventilated racks equipped with HEPA filters, under controlled humidity (40–70%) and temperature (21–23 °C). Animals were kept in plastic cages (approximately 25 × 35 cm) with grid lids and sterile wood shavings as bedding. A 12-hour light/dark cycle was maintained. Sterile food and water were provided ad libitum.

All animal handling procedures, including cage changes and treatments, were performed in laminar flow workstations. Sample collection was conducted under anesthesia using ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), followed by euthanasia via CO₂ inhalation. Protocols for animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee (Res. Nro. 2477/2016).

Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes of Dm28c strain (DTU TcI) were obtained from an in vitro infection. Briefly, Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (ThermoFisher, USA), high glucose with L-Glutamine and pyruvate, supplemented with 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS) (Internegocios S.A., Argentina). Cell-derived trypomastigotes were obtained by infection with metacyclic trypomastigotes in Vero cell monolayers. Trypomastigotes were collected from the supernatant of the infected cells culture, harvested by centrifugation at 7000 × g for 10 min at room temperature, resuspended in resuspended DMEM medium, and counted using a Neubauer chamber. Parasite suspensions were adjusted to the desired concentration in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Experimental infection

Mice were infected intraperitoneally with 50.000 cell-derived trypomastigotes resuspended in 100 µL of sterile PBS.

The progression of

T. cruzi infection was monitored at different days post-infection (dpi). Parasitemia was assessed by direct microscopic examination of peripheral blood samples according to Brener’s method as described [

9,

10].

General health condition and survival were evaluated daily up to 56 days post-infection (dpi). At days 7, 10, 14, and 21 pi, samples were collected. Hearts and spleens were cut in pieces and slices preserved either in paraffin for histological analysis or in RNAhold® solution (TransGen Biotech CO., China) for molecular studies.

Spleens were also weighed at the time of collection.

Heart histology

Cardiac tissues obtained from animals sacrificed at 7, 10, 14, 21, and 56 dpi were processed by routine histological techniques. Samples previously fixed in 4% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin, were sectioned at 5 μm thickness. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed at the Morphology Service of the Facultad de Ciencias Bioquímicas y Farmacéuticas, Universidad Nacional de Rosario (FBIOyF, UNR).

For each animal, 3–4 cardiac tissue sections were analyzed. Inflammatory infiltrates were evaluated based on their size and type, and a score was assigned to estimate the severity of myocarditis. The score was determined as follows: absence of foci was scored as no inflammation, mild foci indicated slight infiltration with damage of one or two myocardial fibers, moderate foci were infiltrates compromising three to five myocardial fibers, and severe foci were dense infiltrates with destruction of more than five myocardial fibers. Additionally, the presence of amastigote nests was evaluated. Six random fields per section were analyzed at 20× magnification.

RNA Extraction and Spleen Cytokine Expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from mouse spleens stored in RNAhold® using TriReagent® (MRC, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality and quantity were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry (Abs260nm/280nm), respectively. RNA samples were treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega Corporation, USA) to remove contaminating genomic DNA before reverse transcription.

One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using oligo(dT) primers and M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega Corporation, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR was performed using HOT FIREPol® EvaGreen® qPCR Supermix (Solis BioDyne, Estonia) in a Bio-Rad CFX Maestro System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA). Gene-specific primers for the target cytokines (

Table 1) were used for amplification. For the determination, cDNAs were diluted 1:20 using ultrapure water.

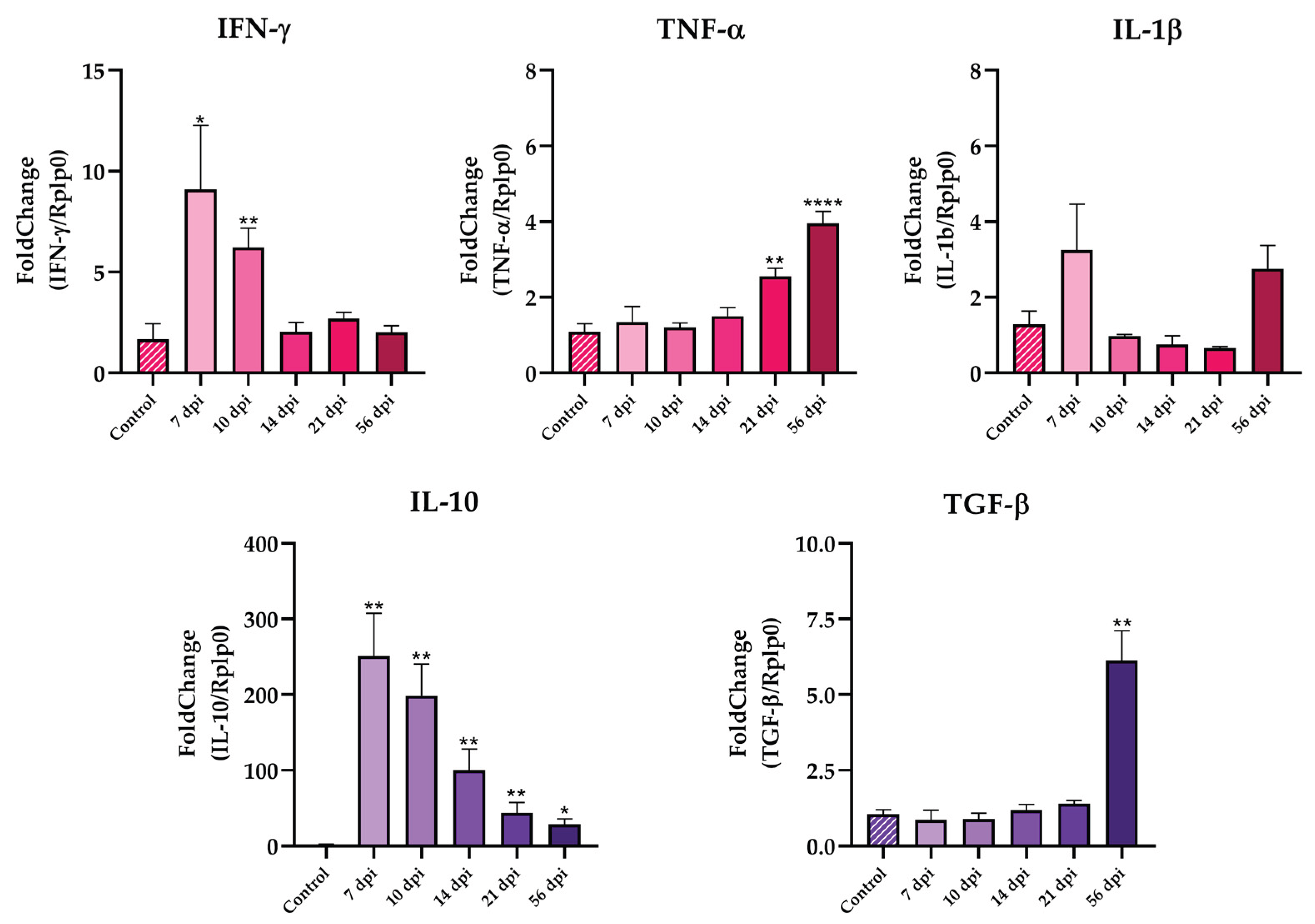

Messenger RNA (mRNA) levels for interferon γ (IFN-γ), interleukin 1-β (IL-1β), tumoral necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin 10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) at different dpi were estimated using the ∆∆Ct method relative to the RPLP0 gene expression (60S acidic ribosomal protein P0). For each gene, reaction specificity was confirmed by performing a melting curve analysis between 55°C and 95°C, with continuous fluorescence measurements.

Statistical analysis

All analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, USA). Expression data were analyzed by the ΔΔCt method, normalized to the housekeeping gene RPLP0, and expressed relative to the uninfected control group. Results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t-test. Parasitemia (trypomastigotes/50 microscopic fields) and spleen weight variations were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance was considered at p<0.05. Levels of significance were indicated as follows: p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***) and p < 0.0001 (****).

3. Results

3.1. T. cruzi Dm28c Trypomastigotes Establish a Mild, Non Lethal Infection in BALB/c Mice Allowing to Follow the Progression of a Low Virulence Chagas Disease Model

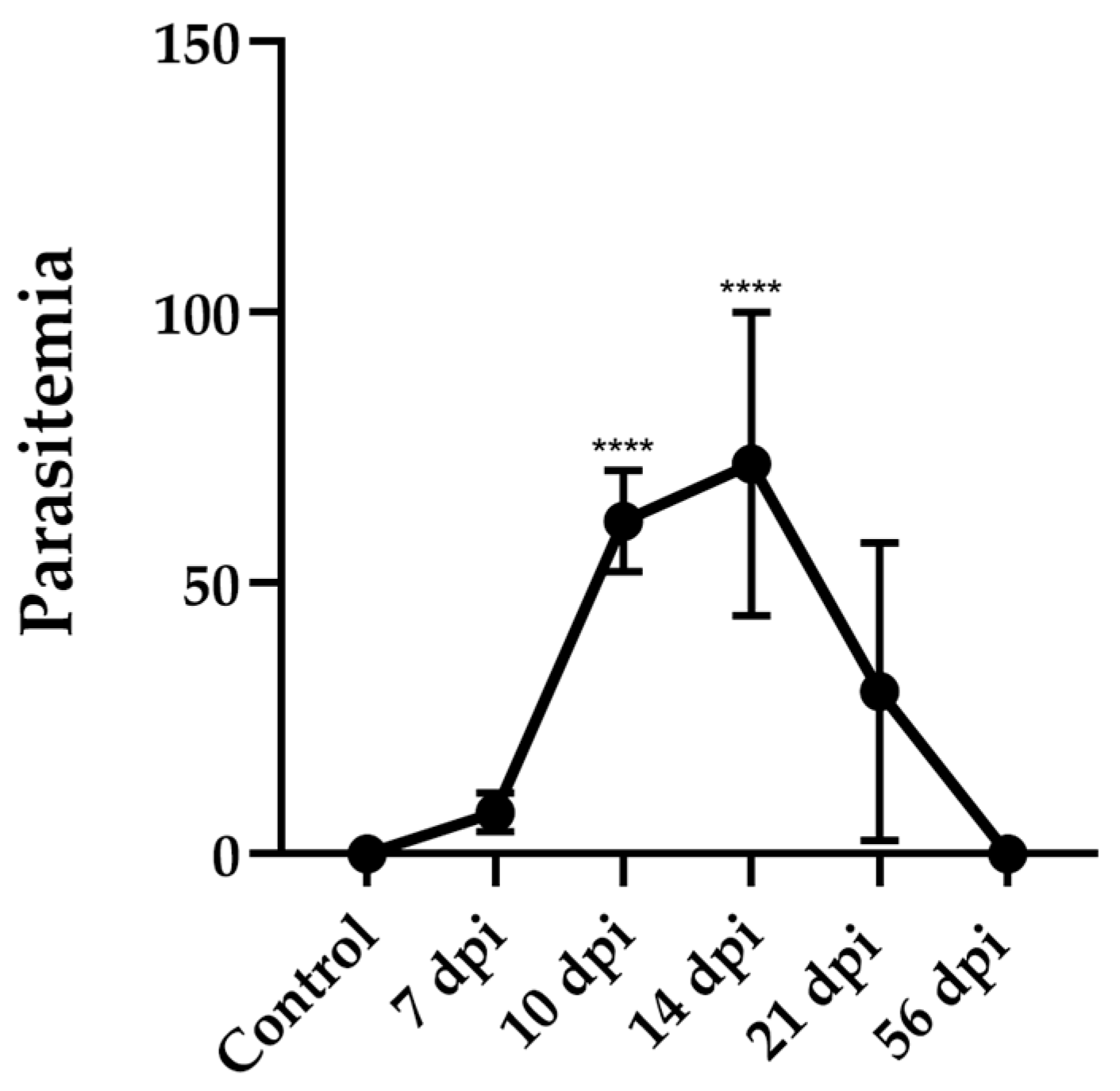

3.1.1. Parasitemia in Dm28c Infected Mice Showed a Peak at 14 Days Post-Infection and Become Undetectable by Day 56

BALB/c mice were infected intraperitoneally with 50.000 cell culture infection-derived trypomastigotes of the T. cruzi Dm28c strain. Infection was monitored at different days post-infection (dpi) and survival was evaluated daily up to 56 dpi.

All the animals survived throughout the entire period showing good general health condition, with no signs of piloerection, hunched posture, ocular alterations, altered mobility, or diarrhea. Notwithstanding the apparent “healthy” external conditions, parasitemia was detectable between 7 and 21 dpi, reaching a peak of 72 ± 28 trypomastigotes per 50 microscopic fields (mean ± SD) between 10 and 14 dpi. Thereafter, parasitemia progressively decreased, becoming undetectable by 56 dpi (

Figure 1).

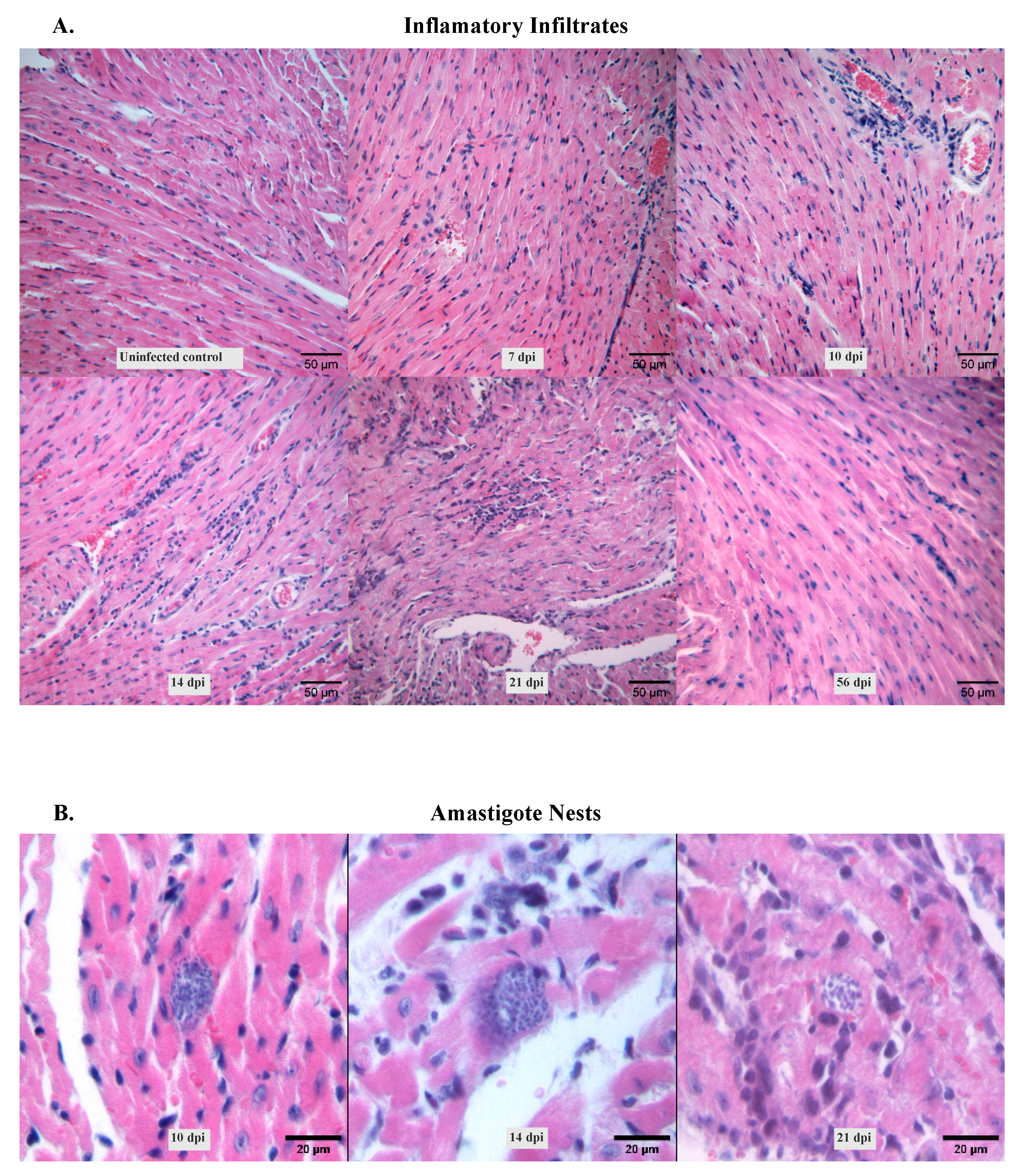

3.1.2. Amastigote Nests and Myocarditis Signs Were Visible During the Acute Infection

Heart condition was also evaluated during the study period. Histological analysis of hematoxylin and eosin-stained heart tissues revealed that infection with Dm28c strain induced acute cardiomyopathy characterized by diffuse inflammatory infiltrates (

Figure 2.A). These infiltrates became visible from 7 dpi, when mononuclear cells progressively accumulated in the interstitial spaces. Intense inflammation was observed at 14 and 21 dpi, followed by a gradual decline (

Table 2). By 56 dpi, the infiltration was mild and comparable to that observed at the non-infected control. Notably, the infiltrates appeared uniformly distributed across the cardiac tissue, with no apparent focal accumulation.

Amastigote nests were also detected in the cardiac tissue and followed a similar temporal pattern with the peak of inflammation (

Figure 2.B).

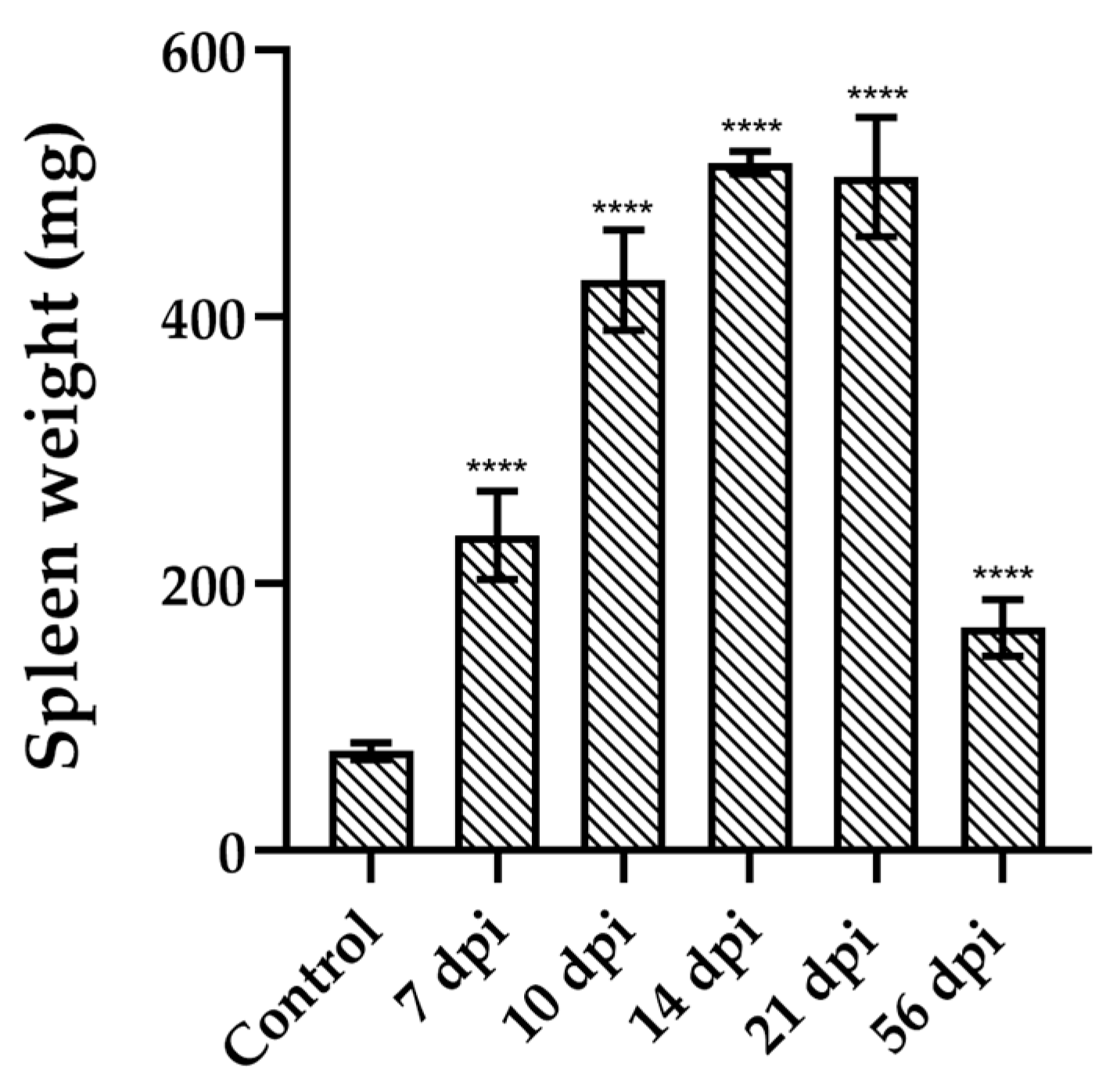

3.1.3. Splenomegaly Induced by Dm28c Infection Paired the Parasitemia Profile

Given the spleen’s pivotal role in immune surveillance and parasite control, we evaluated its size throughout the infection with the Dm28c strain. Splenomegaly was evident in infected animals as early as 7 dpi. Spleen weight progressively increased during infection, peaking at 14 dpi with a mean weight of 516.1 ± 8,505 mg (mean ± SD), representing nearly a 7-fold increase compared to uninfected controls (

Figure 3). Thereafter, spleen size gradually decreased, reaching, at 56 dpi, values comparable to those observed at 7 dpi.

3.2. Splenic Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokine Gene Expression Patterns May Influence Infection Progression

Both cardiac and splenic tissues showed increasing inflammation during the acute infection. To better characterize this inflammatory response, we evaluated the mRNA levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the spleen by RT-qPCR. Animals showed an increased expression of IFN-γ from 7 to 10 dpi and then dropped during the rest of the infection as shown in

Figure 4. A similar pattern was observed for IL-1β, which reached its maximum expression at 7 dpi and gradually decreased over time, although these changes were not statistically significant. TNF-α expression remained low until 21 dpi, where its levels significantly increased (**p < 0.01,

Figure 4). On the other hand, IL-10 expression increased at 7 dpi and gradually declined, but IL-10 mRNA levels remained significantly elevated compared to uninfected animals (

Figure 4). No changes where found in TGF-β levels during the acuate phase.

4. Discussion

Animal models have been instrumental in unraveling the intricate host-parasite interactions that shape disease progression. Among the various factors influencing infection outcomes, the genetic diversity of

T. cruzi and the host immune response are central. Experimental evidence from both clinical and laboratory studies supports the notion that disease manifestations result from the interplay between the parasite strain and the host genetic background. In this context, the immune system, particularly the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory responses, plays a pivotal role.

T. cruzi genetic diversity significantly influences pathogenicity, virulence, immune response, diagnosis, and treatment outcomes. From a clinical and epidemiological perspective, DTUs have been associated with varying symptomatology and disease progression. The infecting strain may influence the course of the disease, including the development of cardiac or digestive manifestations, or may result in an asymptomatic state [

3,

11].

In this study, we stablished a murine experimental model using

T. cruzi Dm28c strain from DTU TcI to infect BALB/c mice, representing a low-virulence non-lethal Chagas' disease model. The infection was characterized by an acute phase, where parasitemia can be detected by direct blood examination from 7 dpi, peaking at 14 dpi, and then decreasing to become undetectable by 56 dpi (

Figure 1). Notably, despite the circulating trypomastigotes, animals maintained a healthy general state throughout the infection, showing no weight loss nor clinical manifestations such as piloerection, hunchback posture, or reduced mobility.

These findings clearly contrast with experimental models using other

T. cruzi and/or mice strains. Roggero et al. infected C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice with the higher virulence Tulahuen strain from DTU TcVI [

12]. In both animal strains, they observed a peak of parasitemia at 21 dpi and loss of body weight, an indicator of overall health status, in accordance with a more severe acute phase. Moreover, the Tulahuen-infected mice exhibited 96% mortality between 21 and 25 dpi in C57BL/6, and 40% in BALB/c strain. In contrast, in our model of Dm28c-infected BALB/c mice, a 100% survival was observed.

Other low-virulence animal models of Chagas disease have been performed using Sylvio X10/4 strain, which also belongs to DTU TcI [

13]. Interestingly, although both Dm28c and Sylvio X10/4 belong to TcI, their behave differently in experimental models. Indeed, DTU TcI has its own intrinsic variability, presents the broadest geographical distribution in the American continent and has been associated to severe forms of cardiomyopathies. Cruz et al. (2014) observed significant differences between TcI domestic cycle-associated strains and sylvatic cycle-associated strains. While domestic strains presented higher parasitemias and low levels of histopathological damage, sylvatic strains showed lower parasitemias and significant levels of histopathological damage [

14]. Despite their shared sylvatic origin, Dm28c and Sylvio X10/4 display divergent behaviors during infection. In contrast to Sylvio X10/4, whose bloodstream trypomastigotes are rarely detectable by microscopy and lead to chronic myocarditis in C3H/He mice [

13], Dm28c parasites were clearly observed in peripheral blood from BALB/c infected mice from 7 to 21 dpi and showed no signs of heart inflammation by 56 dpi. Additionally, it was observed that the severe chronic myocarditis seen in Sylvio-infected C3H/He mice was absent in C57BL/6, A/J, BALB/c and DBA mice strains, suggesting that both parasite’s genetic background and host’s genetics play critical roles in shaping the outcome of infection [

13,

15]. Regarding Dm28c, infection of Swiss mice also exhibited a non-lethal infection, with a parasitemia peak at 23 dpi and no significant changes in body weight or evidence of inflammatory infiltrates during a 77-day follow-up [

16]. Histological analyses of cardiac tissues from BALB/c mice infected with Dm28c revealed diffuse lymphocytic infiltrates from 7 dpi and the presence of amastigotes nests at the peak of parasitemia at 21 dpi. These manifestations were less severe than those observed in BALB/c- and C57BL-Tulahuen infections, which present well-defined inflammatory foci by 14 dpi and the presence of amastigote nests [

12]. By 56 dpi, heart pathology in Dm28c-infected BALB/c mice had largely resolved, and neither amastigote nests nor marked infiltrates were visible. Thus, our findings suggest that, in addition to different tissue tropisms, different

T. cruzi strains, can also elicit distinct tissue responses in the heart [

17].

At splenic level, BALB/c mice infected with Dm28c presented marked splenomegaly, with spleen weight peaking at 14 dpi approximately 6.8 times greater than uninfected mice. Interestingly, this pattern mirrored parasitemia behavior, suggesting a direct relationship between parasite burden and splenic response. This expansion coincided with increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly IFN-γ and IL-1β, early during the acute phase (

Figure 4), reflecting a predominant activation of the innate and Th1 immune axes. Simultaneously, elevated levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 were observed, likely as a compensatory regulatory mechanism aimed at mitigating tissue damage caused by excessive inflammation. A late increase in TNF-α and TGF-β was observed at 56 dpi, suggesting an ongoing modulation of the immune response, even as splenic size decreased. Indeed, although spleen weight was reduced at this point, it remained higher than uninfected mice.

Our study demonstrates that the T. cruzi Dm28c strain induces a mild, non-lethal infection in BALB/c mice, which could be a good model to study the evolution from the acute phase to an indeterminate or non-symptomatic chronic infection, enabling the analysis of disease progression. In contrast to more virulent strains like Tulahuen, Dm28c triggered a balanced immune response and caused limited tissue damage, with partial resolution of pathology following the peak of parasitemia. This approach remains suitable for long-term follow-up and evaluation of chronic stages, and it remains a promising strategy to further explore immunological and pathological features of the chronic phase in future studies.

Our findings highlight the relevance of strain-dependent variability in experimental models of Chagas disease. The Dm28c-infected BALB/c model offers a valuable platform for investigating host–parasite interactions across disease stages. Moreover, it provides a suitable framework for evaluating diagnostic, therapeutic and preventive strategies under low-virulence conditions and simulating diverse epidemiological scenarios.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, P.C and S.V.; methodology, A. de H. and S.V.; investigation, A. de H., S.V. and P.C..; resources, S.V. and P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A. de H., S.V. and P.C.; writing—review and editing, A. de H. and P.C.; funding acquisition, P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by the Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación (Agencia I+D+i), Argentina, grant numbers: PICT 2016-0439 and PICT 2019-4212, and by the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina, grant number: PIP 2021-0848.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee of FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS MEDICAS, UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE ROSARIO (Res. Nro. 2477/2016 date of approval October 18th, 2016).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in the Universidad Nacional de Rosario Dataverse Repository (RDA-UNR) at the following DOI:

https://doi.org/10.57715/UNR/TLENTW.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tec. María Dolores Campos and Romina Manarín for the valuable assistance with cell and parasite culture techniques, and Facundo Rojas for his technical support at the IBR. We are also grateful to the members of the Histotechnology Service at FBIOyF, UNR, Histotechnicians Alejandra Quintana and Diego Parenti, for their essential contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| dpi |

days post-infection |

| DTU |

Discrete Typing Unit |

| FCS |

Fetal calf serum |

| IFN-γ |

Interferon gamma |

| IL-10 |

Interleukin-10/ human cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor |

| IL-1β |

Interleukin-1 beta |

| mRNA |

Message RNA |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| TGF-β |

Transforming growth factor β |

| TNF-α |

Tumoral necrosis factor alfa |

References

- Nunes, M.C.P.; Dones, W.; Morillo, C.A.; Encina, J.J.; Ribeiro, A.L. Chagas Disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2013, 62, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Word Health Organization (WHO) Chagas Disease (Also Known as American Trypanosomiasis).

- Zingales, B. Trypanosoma Cruzi Genetic Diversity: Something New for Something Known about Chagas Disease Manifestations, Serodiagnosis and Drug Sensitivity. Acta Tropica 2018, 184, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingales, B.; Bartholomeu, D.C. Trypanosoma Cruzi Genetic Diversity: Impact on Transmission Cycles and Chagas Disease. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2022, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingales, B.; Macedo, A.M. Zingales, B.; Macedo, A.M. Fifteen Years after the Definition of Trypanosoma Cruzi DTUs: What Have We Learned? 2023. [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Ortiz, N.; Herrera, G.; Hernández, C.; Muñoz, M.; Ramírez, J.D. Discrete Typing Units of Trypanosoma Cruzi: Geographical and Biological Distribution in the Americas. Scientific Data 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revollo, S.; Oury, B.; Vela, A.; Tibayrenc, M.; Sereno, D. In Vitro Benznidazole and Nifurtimox Susceptibility Profile of Trypanosoma Cruzi Strains Belonging to Discrete Typing Units TcI, TcII, and TcV. Pathogens 2019, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talvani, A.; Teixeira, M.M. Experimental Trypanosoma Cruzi Infection and Chagas Disease—A Word of Caution. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BRENER, Z. Therapeutic Activity and Criterion of Cure on Mice Experimentally Infected with Trypanosoma Cruzi. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo 1962, 4, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pérez, A.R.; Lambertucci, F.; González, F.B.; Roggero, E.A.; Bottasso, O.A.; Meis, J. de; Ronco, M.T.; Villar, S.R. Death of Adrenocortical Cells during Murine Acute T. Cruzi Infection Is Not Associated with TNF-R1 Signaling but Mostly with the Type II Pathway of Fas-Mediated Apoptosis. Brain, behavior, and immunity 2017, 65, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestrini, M.M.A.; Alessio, G.D.; Frias, B.E.D.; Sales Júnior, P.A.; Araújo, M.S.S.; Silvestrini, C.M.A.; Brito Alvim De Melo, G.E.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Teixeira-Carvalho, A.; Martins, H.R. New Insights into Trypanosoma Cruzi Genetic Diversity, and Its Influence on Parasite Biology and Clinical Outcomes. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1342431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roggero, E.; Perez, A.; Tamae-Kakazu, M.; Piazzon, I.; Nepomnaschy, I.; Wietzerbin, J.; Serra, E.; Revelli, S.; Bottasso, O. Differential Susceptibility to Acute Trypanosoma Cruzi Infection in BALB/c and C57BL/6 Mice Is Not Associated with a Distinct Parasite Load but Cytokine Abnormalities. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2002, 128, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho, C.R.F.; Nuñez-Apaza, L.N.; Bortoluci, K.R.; Bombeiro, A.L.; Bucci, D.Z.; Grisotto, M.G.; Sardinha, L.R.; Jorquera, C.E.; Lira, S.; D’Império Lima, M.R.; et al. Infection by the Sylvio X10/4 Clone of Trypanosoma Cruzi: Relevance of a Low-Virulence Model of Chagas’ Disease. Microbes and Infection 2009, 11, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, L.; Vivas, A.; Montilla, M.; Hernández, C.; Flórez, C.; Parra, E.; Ramírez, J.D. Comparative Study of the Biological Properties of Trypanosoma Cruzi I Genotypes in a Murine Experimental Model. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2015, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho, C.R.F.; Bucci, D.Z.; Dagli, M.L.Z.; Bastos, K.R.B.; Grisotto, M.G.; Sardinha, L.R.; Baptista, C.R.G.M.; Penha Gonçalves, C.; Lima, M.R.D.; Álvarez, J.M. Pathology Affects Different Organs in Two Mouse Strains Chronically Infected by a Trypanosoma Cruzi Clone: A Model for Genetic Studies of Chagas’ Disease. Infect Immun 2004, 72, 2350–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvet, C.M.; Meuser, M.; Almeida, D.; Meirelles, M.N.L.; Pereira, M.C.S. Trypanosoma Cruzi–Cardiomyocyte Interaction: Role of Fibronectin in the Recognition Process and Extracellular Matrix Expression in Vitro and in Vivo. Experimental Parasitology 2004, 107, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriques, C.; Henriques-Pons, A.; Meuser-Batista, M.; Ribeiro, A.S.; De Souza, W. In Vivo Imaging of Mice Infected with Bioluminescent Trypanosoma Cruzi Unveils Novel Sites of Infection. Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).