1. Introduction

While essential for respiratory support in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) patients, mechanical ventilation paradoxically risks worsening lung injury through Ventilator Induced Lung Injury (VILI) pathogenesis. The dual mechanisms of alveolar volutrauma and barotrauma induce damage that may cause systemic inflammation and impair recovery, particularly in already injured lungs [

1]. Lung and Diaphragm Protective Ventilation (LDPV) has been shown to significantly improve survival [

2].

However, beyond conventional parameters like tidal volume and plateau pressure, newer physiologic metrics have emerged to quantify the mechanical “stress” imposed by ventilation [3]. Among these, driving pressure (ΔP) has gained recognition as a critical determinant of outcome [

4,

5]. Amato et al. found ΔP to be the ventilatory variable most strongly associated with survival in ARDS, with each reduction in ΔP translating to a substantial mortality benefit [

6].

More recently, the concept of mechanical power (MP)—the rate of energy transfer from the ventilator to the lung—has been proposed as a comprehensive index of VILI risk [

3]. Elevated MP reflects the combined injurious effects of high tidal volumes, airway pressures, and respiratory rates. MP is associated with increased mortality among mechanically ventilated ICU patients [

7].

These findings suggest that decreasing ΔP and MP may be key to improving outcomes in critically ill patients. To examine these relationships, we analyzed all adult mechanically ventilated patients in our ICU over a 12-year period (2012-2024) retrospectively. Our primary objective was to assess whether ICU mortality declined following the implementation of a standardized LDPV protocol focused on ΔP and MP optimization. Secondary aims included evaluating temporal trends in key ventilatory parameters. Secondary objectives included: (1) analyzing longitudinal trends in key respiratory mechanics, and (2) assessing the real-world clinical translation of physiological benefits into measurable survival outcomes. This work bridges an important knowledge gap between trial evidence and bedside implementation by testing whether mechanistic improvements yield actual survival advantages in heterogeneous ICU populations.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the University of Health Sciences, Bakırköy Dr. Sadi Konuk Training and Research Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Committee with protocol number 2025/24 and decision number 2025-02-17.

Study Design and Population

This retrospective, cohort study was conducted in Bakirkoy Dr Sadi Konuk Training and Research Hospital, 30 beds general ICU between January 2012 and December 2024. We retrieved this dataset by utilizing structured query language queries from the IMD Soft-Metavision/QlinICU Clinical Decision Support (Israel) system. All patients aged ≥18 years who received invasive mechanical ventilation for at least 24 hours were included in the study. We excluded: 1. Patients with missing respiratory mechanics or ICU mortality data, 2. Those who received invasive mechanical ventilation for less than 24 hours, 3. Patients who received non-invasive mechanical ventilation, 4. Patients with Extracorporeal support (ECMO or ECCO2R) treatments, 5. Patients with terminal illness (life expectancy <48 hours), 6. Pediatric patients. All patients were ventilated with Maquet Servo-i (Getinge, Sweden) in pressure control ventilation (PCV) and volume control ventilation (VCV) modes.

Study Periods

Following the publication of several studies in 2015–2016 demonstrating the association between reduced ΔP and MP and improved survival, LDPV protocol was established in our clinic. As of November–December 2018, this protocol has been implemented in all intubated patients.

To evaluate the impact of LDPV, we divided patients into two groups based on the implementation period of the LDPV strategy: The pre-LDPV group, from January 2012 to December 2018, and the Post-LDPV group, from January 2019 to December 2024. The LDPV protocol, introduced at the end of 2018 for all intubated patients consisted of low tidal volume ventilation (6–8 mL/kg), individualized Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) titration, maintaining ΔP below 15 cmH₂O, and reducing MP.

Data Collection

Demographic variables (age, sex, Body Mass Index (BMI), diagnosis on admission, comorbidities), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score (24 hour after admission), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores at first and last day of admission at ICU, mechanical ventilation duration and respiratory mechanics (Expiratory Tidal Volume (TVe), Respiratory rate (RR), PEEP, Peak pressure (Ppeak), Compliance (C), ΔP, and MP) were extracted from the electronic medical records. The Metavision automatically records data from all upstream devices minute by minute, including MV parameters. Monthly ICU mortality data were collected for the both group ventilated longer than 24 hours. Minute time slots were transferred from the data pool to Microsoft Excel as hourly time slots through the functions of SQL queries. The hourly mechanical ventilation parameters in the Excel dataset were calculated at 24-hour intervals (days) using the LEFT function of the Excel program as follows:

It was calculated by taking the difference of the first 10 characters of the signal date (Time 1) of the parameters transferred to the software from the mechanical ventilator and the first 10 characters of the patient’s admission to the ICU (Time 2) (=LEFT (Time 1;10)-(LEFT(Time 2;10)).

Calculation of Total Mechanical Power (MPtot)

For VCV mode, the volume control simplified equation (MPvcv−simpl) developed by Gattinoni et al and for PCV, the pressure control simplified equation (MPpcv−simpl) developed by Becher et al was used in this study.[

8,

9]

MPtotvcv-simpl=(0.098×RR×TVe×(Ppeak–DP/2))

MPtotpcv-simpl=(0.098×RR×TVe×(PEEP+ΔPinsp)).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the NCSS (Number Cruncher Statistical System) 2007 software (Kaysville, Utah, USA). In the evaluation of the study data, descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation, median, frequency, percentage, minimum, maximum) were employed, and the distribution of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For the comparison of quantitative variables between two groups, the Student’s t-test was used. The Chi-square test was applied to determine the relationship between categorical variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors influencing the dependent variable. Statistical significance was evaluated at the p<0.01 and p<0.05 levels.

3. Results

The study cohort comprised 4,530 critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Overall ICU mortality was 41.2%, with a survival rate of 58.8%. Sex-stratified analysis revealed:

Among female patients (n=1,753), the survival rate was 53.9% (n=944)

Among male patients (n=2,777), the survival rate was 57.8% (n=1,605)

Although the proportion of non-survivors was slightly higher among females, the difference between sexes was not statistically significant (p = 0.055). The comparison between the non-survived group and the surviving patients revealed several statistically significant differences (p=0.001). The non-survived group had a significantly lower RR, TVe, C, and hospital stay duration. In contrast, they had significantly higher values in PEEP, Ppeak, ΔP, MP, initial and final SOFA scores, APACHE II score, mechanical ventilation duration, age and BMI. The 2012-2018 group had significantly higher values in RR, PEEP, TVe, SOFA (initial and final), Ppeak, DP, MP, BMI, length of ICU stay, and ventilation time compared to the 2019-2024 group (p=0.001; p<0.05). Conversely, C, APACHE II, age, were significantly lower in the 2012-2018 group (p=0.001; p<0.05). The admission of patients with pulmonary diagnoses increased from 26.2% to 39.5% in 2019-2024 group (p<0.001), while gastrointestinal and cardiac admissions decreased (25.4% to 17.9% and 15.5% to 8.1%, respectively (p<0.001)). Except of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), the prevalence of all the comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, malignancy, cerebrovascular diseases, coronary artery diseases, heart and liver failure) increased significantly in 2019-2024 group (p< 0.001). Despite the increased prevalence of comorbidities, the mortality is lower in 2019-2024 suggesting that LDPV may mitigate risk in more complex patient groups. These findings suggest that patients in the non-survived group were generally older, had higher severity scores and ventilatory demands, and experienced more compromised respiratory mechanics compared to survivors (

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4).

Analysis of regression coefficients showed that RR (β=1.195, p<0.01), TVe (β=1.007, p<0.01), final SOFA score (β=0.85, p<0.01), Ppeak (β=1.117, p<0.01), DP (β=0.843, p<0.01), APACHE II score (β=0.979, p<0.01), MP (β=0.863, p<0.01), age (β=0.991, p<0.01), length of ICU stay (β=1.007, p<0.01), and ventilation time (β=0.993, p<0.01) had a statistically significant and positive impact on mortality. In other words, patients who died had higher values of RR, TVe, final SOFA, Ppeak, DP, APACHE II, MP, age, length of ICU stay and ventilation duration compared to survivors (

Table 5).

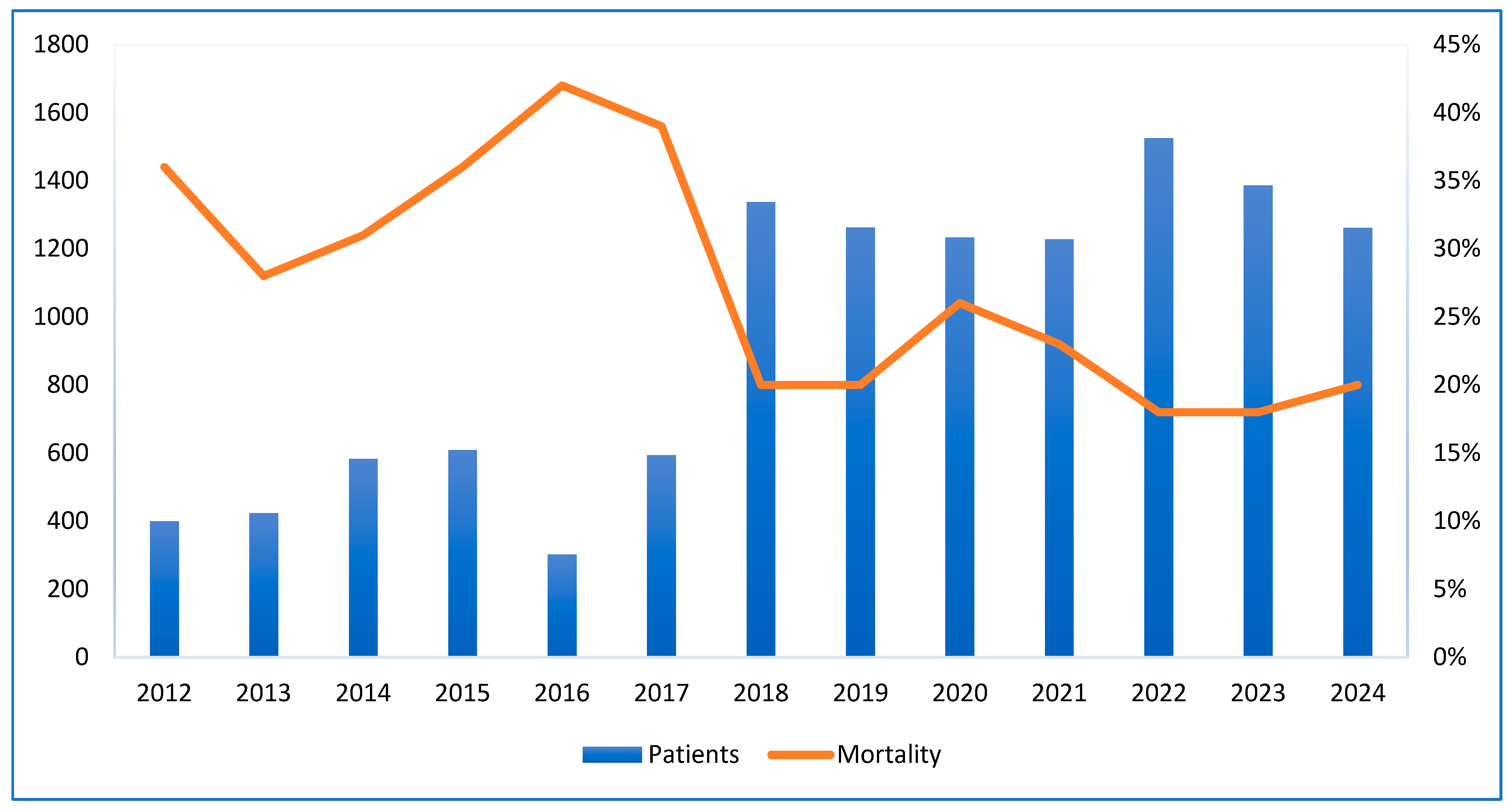

The graph shows that ICU admissions rose from around 400 in 2012 to over 1500 in 2022. A sharp increase occurred in 2018, jumping from 600 to approximately 1350. Meanwhile, the ICU mortality rate decreased from 37% in 2012 to about 20% in 2018 and stayed stable through 2024. The highest mortality rate was over 40% in 2016, when admissions were around 600. This inverse trend after 2018 suggests improved healthcare outcomes despite rising admissions and COVID-19 pandemic (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

Following implementation of a standardized LDPV protocol in last month of 2018, we observed a significant mortality reduction: from about 40% in the pre-implementation period (2012-2018) to 20% post-implementation (2019-2024), suggesting LDPV may substantially improve outcomes in ICU patients. Non-survivors demonstrated greater age, illness severity scores, worse respiratory mechanics (higher PEEP, Ppeak, ΔP, MP and lower C), more severe physiological derangements across multiple organ systems. Multivariable regression identified age, APACHE II, RR, TVe, Ppeak, ΔP and MP as independent risk factors for ICU mortality. Despite increased age and APACHE II score in the 2019-2024 period, ventilator settings and respiratory mechanics became more protective, highlighting the clinical impact of LDPV.

Our observation of higher ΔP in non-survivors (14.9 vs. 12.9 cmH₂O, p<0.001) aligns with current evidence. A 2022 retrospective ARDS cohort study reported ΔP >14.5 cmH₂O in non-obese patients as an independent mortality predictor (OR 1.04; p < 0.05)(10) . Similarly, a large multicenter study Checkly et al. demonstrated that ΔP was independently associated with hospital mortality in both ARDS and non ARDS adults [

11]. These findings confirm that high ΔP remains a potent and universal risk factor across ICU settings.

Our observed association between elevated MP (>17 J/min) and mortality aligns with findings from the multinational CHEST registry study, which reported an adjusted odds ratio of 1.58 for ICU mortality at this threshold [

12]. A Dutch study of 1,962 non-ARDS ventilated patients found MP independently predicted 28-day mortality [

13]. These datas cofirm that elevated MP independently predicts mortality through mechanisms extending beyond its constituent parameters. Parhar et al. showed that MP >22 J/min in ARDS patients was associated with lower ventilator-free days and worse 3-year survival [

14]. Despite our study spanning mixed ICU populations, the overlap in MP thresholds supports the generalizability of this risk metric. ARDS-specific findings reveal that MP provides critical prognostic value beyond traditional targets like ΔP or airway pressures.

Furthermore, a Korean study evaluated MP using a simplified PCV equation in 125 patients, finding higher MPPCV (17.6 vs. 26.3 J/min) correlated with ICU mortality (OR 1.09; p = 0.003) [

15]. This reaffirms that MP is relevant across ventilation modes and that simplified calculations may be effectively used in routine practice. It is noteworthy that MP predicted ICU mortality in neurocritical patients (cutoff 12.16 J/min; OR 1.11 per J/min; p < 0.001), outperforming Glascow coma scores [

16]. Additionally, in pediatric ARDS patients, higher MP (per 0.1 J/min/kg) was associated with increased ICU mortality (OR 1.22; p = 0.036) [

17]. These results highlight MP’s cross-population applicability and the need to apply PLDV across diverse age and clinical groups.

A 2020 post hoc analysis of 839 invasively ventilated adults showed that a 1 cmH₂O increase in ΔP was associated with a 5% increase in 90 day mortality, while a 100 mJ/min/kg PBW rise in MP carried a 20% higher risk. Both ΔP and MP had AUROCs around 0.70 for predicting 90 day mortality, performing comparably to APACHE IV and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II scores [

18]. These studies corroborate our findings that both MP and ΔP are accurate predictors comparable to established severity scores reinforcing their clinical utility.

A 2025 Frontiers study involving PCV patients found that non-survivors had higher ΔP, MP, and dynamic lung-threshold indices (e.g., LTC_ MPdyn) [

19]. Adjusted models confirmed MP (aOR 1.03 per J/min) and respiratory mechanics as significant mortality predictors. These results provide strong mechanistic alignment with our multivariable observations.

After 2019, our ICU saw a notable reduction in ΔP (14.7 → 13.1 cmH₂O) and mechanical power (18 → 14 J/min), concurrent with improved mortality. These data showing decreasing ventilator-associated mortality in settings adopting MP- and ΔP-guided LDPV. Our findings provide real-world evidence that structured LDPV protocols can yield dramatic survival benefits, even in broader ICU settings.Taken together, these studies advocate for bedside monitoring of ΔP and MP. Targets such as ΔP <15 cmH₂O and MP <17 J/min appear achievable and associated with optimal outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, including a large sample size spanning 12 years, enabling a robust analysis of minute-level DP, MP calculation across both ARDS and non-ARDS patients. The pre- and post-implementation comparison of lung-protective ventilation (LPV) strategies adds further value by capturing practice evolution over time. However, the study also has a notable limitation. Its retrospective, single-center design may restrict the generalizability of findings. The observational nature of our study and baseline imbalances between groups preclude causal inferences. However, the consistent association between reduced DP, MP and improved survival aligns with prior evidence supporting LDPV, warranting further prospective validation.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights that optimizing ΔP and MP through LDPV is strongly associated with a significant reduction in ICU mortality, even among older patients and those with higher illness severity. This finding is consistent with emerging evidence across ARDS, non-ARDS, and neurocritical care populations, reinforcing the role of ΔP and MP as critical metrics for VILI. The observed survival benefit supports the adoption of real-time, physiology-driven ventilation strategies guided by ΔP and MP to enable early detection of harmful ventilatory patterns and timely intervention. As intensive care moves toward individualized approaches, integrating these parameters into routine practice—potentially through automated systems—could enhance safety, improve outcomes, and redefine standards for mechanical ventilation management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Zafer Cukurova and Payam Rahimi; formal analysis: Emral Canan, data curation: Zafer Cukurova; writing—original draft preparation, Payam Rahimi and Tugba Yucel Yenice; writing—review and editing: Nuri Burkay Soylu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Bakirkoy Dr Sadi Konuk Training and Research Hospital Ethics Committee, protocol number 2025/24 and decision number 2025-02-17 (date of approval: 22/01/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Research data is available and can be shared upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.Abbreviations.

References

- Silva PL, Ball L, Rocco PRM, Pelosi P. Physiological and Pathophysiological Consequences of Mechanical Ventilation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 Jun;43(3):321-334. [CrossRef]

- Rali AS, Tran L, Balakrishna A, Senussi M, Kapur NK, Mektus T, et al. Guide to Lung-Protective Ventilation in Cardiac Patients. J Card Fail. 2024 Jun;30(6):829-837. [CrossRef]

- Paudel R, Trinkle CA, Waters CM, Robinson LE, Cassity E, Sturgill JL, et al. Mechanical Power: A New Concept in Mechanical Ventilation. Am J Med Sci. 2021 Dec;362(6):537-545. [CrossRef]

- Roca O, Goligher EC, Amato MBP. Driving pressure: applying the concept at the bedside. Intensive Care Med. 2023 Aug;49(8):991-995. [CrossRef]

- Rezaiguia-Delclaux S, Ren L, Gruner A, Roman C, Genty T, Stéphan F. Oxygenation versus driving pressure for determining the best positive end-expiratory pressure in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2022 Jul 13;26(1):214. [CrossRef]

- Amato MB, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, Brochard L, Costa EL, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 19;372(8):747-55. [CrossRef]

- Serpa Neto A, Deliberato RO, Johnson AEW, Bos LD, Amorim P, Pereira SM, et al; PROVE Network Investigators. Mechanical power of ventilation is associated with mortality in critically ill patients: an analysis of patients in two observational cohorts. Intensive Care Med. 2018 Nov;44(11):1914-1922. [CrossRef]

- Tremblay LN, Slutsky AS. Ventilator-induced lung injury: from the bench to the bedside. Applied Physiology in Intensive Care Medicine 1: Physiological Notes-Technical Notes-Seminal Studies in Intensive Care. 2012:343-52.

- Becher T, van der Staay M, Schädler D, Frerichs I, Weiler N. Calculation of mechanical power for pressure-controlled ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2019 Sep;45(9):1321-1323. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Chen B, Tong C. Influence of the Driving Pressure on Mortality in ARDS Patients with or without Abdominal Obesity: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2022 Jul 15;2022:1219666. [CrossRef]

- Sahetya SK, Mallow C, Sevransky JE, Martin GS, Girard TD, Brower RG, et al; Society of Critical Care Medicine Discovery Network Critical Illness Outcomes Study Investigators. Association between hospital mortality and inspiratory airway pressures in mechanically ventilated patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2019 Nov 21;23(1):367. [CrossRef]

- von Düring S, Liu K, Munshi L, Kim SJ, Urner M, Adhikari NKJ, et al. The Association Between Mechanical Power Within the First 24 Hours and ICU Mortality in Mechanically Ventilated Adult Patients With Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure: A Registry-Based Cohort Study. Chest. 2025 Mar 28:S0012-3692(25)00403-9. [CrossRef]

- van Meenen DMP, Algera AG, Schuijt MTU, Simonis FD, van der Hoeven SM, Neto AS, et al; for the NEBULAE; PReVENT; RELAx investigators. Effect of mechanical power on mortality in invasively ventilated ICU patients without the acute respiratory distress syndrome: An analysis of three randomised clinical trials. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2023 Jan 1;40(1):21-28. [CrossRef]

- Parhar KKS, Zjadewicz K, Soo A, Sutton A, Zjadewicz M, Doig L, et al. Epidemiology, Mechanical Power, and 3-Year Outcomes in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Patients Using Standardized Screening. An Observational Cohort Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019 Oct;16(10):1263-1272. [CrossRef]

- Sim JK, Lee SM, Kang HK, Kim KC, Kim YS, Kim YS, et al. Association between mechanical power and intensive care unit mortality in Korean patients under pressure-controlled ventilation. Acute Crit Care. 2024 Feb;39(1):91-99. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Zhu Y, Zhen S, Wang L. Mechanical power of ventilation is associated with mortality in neurocritical patients: a cohort study. J Clin Monit Comput. 2022 Dec;36(6):1621-1628. [CrossRef]

- Bhalla AK, Klein MJ, Modesto I Alapont V, Emeriaud G, Kneyber MCJ, Medina A, et al; Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. Mechanical power in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: a PARDIE study. Crit Care. 2022 Jan 3;26(1):2. [CrossRef]

- van Meenen DMP, Serpa Neto A, Paulus F, Merkies C, Schouten LR, Bos LD, et al; MARS Consortium. The predictive validity for mortality of the driving pressure and the mechanical power of ventilation. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2020 Dec 18;8(Suppl 1):60. [CrossRef]

- Kim TW, Chung CR, Nam M, Ko RE, Suh GY. Associations of mechanical power, ventilatory ratio, and other respiratory indices with mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome undergoing pressure-controlled mechanical ventilation. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025 Apr 4;12:1553672. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).