Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

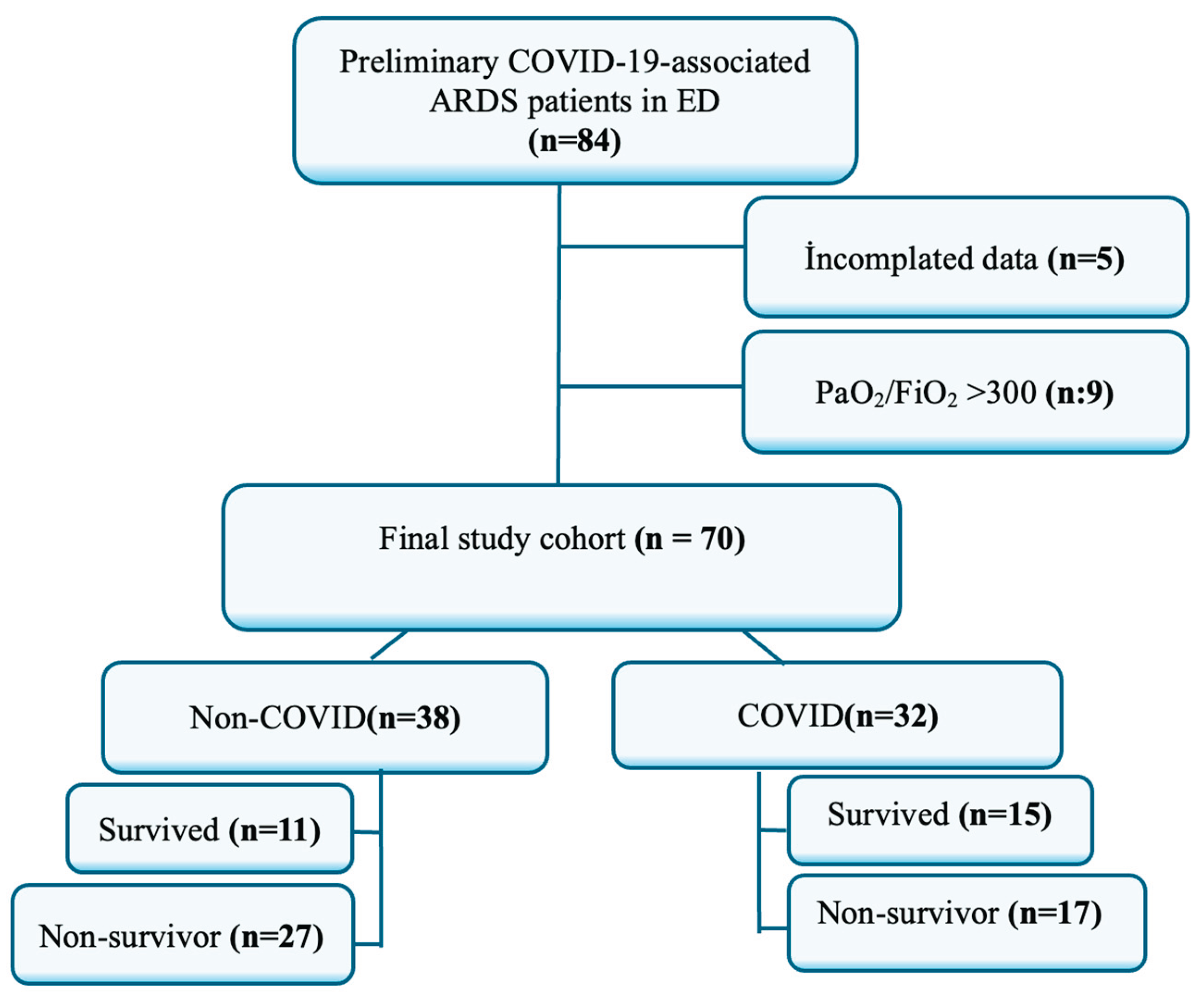

2.2. Patient Selection

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Comorbidities

3.2. Laboratory Parameters

3.3. Mechanical Ventilator Parameters and Mortality

3.4. Clinical Scoring Systems

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hickey, S.M.; Sankari, A.; Giwa, A.O. Mechanical Ventilation. StatPearls 2025.

- Carter, C.; Osborn, M.; Agagah, G.; Aedy, H.; Notter, J. COVID-19 disease: invasive ventilation. Clin. Integr. Care. 2020, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, S.; Singh, V.; Singh, J.; et al. COVID-19 ARDS: A Multispecialty Assessment of Challenges in Care, Review of Research, and Recommendations. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 37, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, D.L.; Bongiovanni, F.; Chen, L.; Menga, L.S.; Cutuli, S.L.; Pintaudi, G.; et al. Respiratory physiology of COVID-19-induced respiratory failure compared to ARDS of other etiologies. Crit. Care. 2020, 24, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, W.; Yang, H.; Shah, F.A.; Suber, T.; Drohan, C.; Al-Yousif, N.; et al. COVID-19 versus Non-COVID-19 Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Comparison of Demographics, Physiologic Parameters, Inflammatory Biomarkers, and Clinical Outcomes. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, 1202–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brault, C.; Zerbib, Y.; Kontar, L.; Fouquet, U.; Carpentier, M.; Metzelard, M.; et al. COVID-19- versus non-COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome: Differences and similarities. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 1301–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbunder, B.; Ehrmann, S.; Piagnerelli, M.; Sauneuf, B.; Serck, N.; Soumagne, T.; et al. Static compliance of the respiratory system in COVID-19 related ARDS: an international multicenter study. Crit. Care. 2021, 25, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, B.A.; Munoz-Acuna, R.; Suleiman, A.; Ahrens, E.; Redaelli, S.; Tartler, T.M.; et al. Mechanical power and 30-day mortality in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients with and without Coronavirus Disease-2019: a hospital registry study. J. Intensive Care 2023, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscolo, A.; Sella, N.; Lorenzoni, G.; Pettenuzzo, T.; Pasin, L.; Pretto, C.; et al. Static compliance and driving pressure are associated with ICU mortality in intubated COVID-19 ARDS. Crit. Care. 2021, 25(1), 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, L.; Silva, P.L.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Bassetti, M.; Zubieta-Calleja, G.R.; Rocco, P.R.M.; et al. Understanding the pathophysiology of typical acute respiratory distress syndrome and severe COVID-19. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2022, 16(4), 437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Li Bassi, G.; Suen, J.Y.; Dalton, H.J.; White, N.; Shrapnel, S.; Fanning, J.P.; et al. An appraisal of respiratory system compliance in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients. Crit. Care. 2021, 25, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.; Chen, L.; Lu, C.; Zhang, W.; Xia, J.A.; Sklar, M.C.; et al. Lung Recruitability in COVID-19-associated Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Single-Center Observational Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 1294–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovas, A.; Sackarnd, J.; Rossaint, J.; Kampmeier, S.; Pavenstädt, H.; Vink, H.; et al. Identification of novel sublingual parameters to analyze and diagnose microvascular dysfunction in sepsis: the NOSTRADAMUS study. Crit. Care. 2021, 25, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L.F.; León Vázquez, M.L.; Villa Fuerte, M.V.E.; Herrera, M.O.G.; Venegas Sosa, A.M.D.C. Initial Static Compliance as a 28-day Mortality Parameter in Patients with COVID-19. J. Community Med. Public Health. 2023, 7, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamar, A.; Guillot, P.; Joussellin, V.; Delamaire, F.; Painvin, B.; Bichon, A.; et al. Moderate-to-severe ARDS: COVID-19 patients compared to influenza patients for ventilator parameters and mortality. ERJ Open Res. 2023, 9, 00554-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, L.; Araya, K.; Becerra, M.; Pérez, C.; Valenzuela, J.; Lera, L.; et al. Predictive value of invasive mechanical ventilation parameters for mortality in COVID-19 related ARDS: a retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, R.; Madotto, F.; Laffey, J.G.; van Haren, F.M.P. Compliance Phenotypes in Early Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome before the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Bassi, G.; Suen, J.Y.; White, N.; Dalton, H.J.; Fanning, J.; Corley, A.; et al. Assessment of 28-Day In-Hospital Mortality in Mechanically Ventilated Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019: An International Cohort Study. Crit. Care Explor. 2021, 3, e0567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puah, S.H.; Cove, M.E.; Phua, J.; Kansal, A.; Venkatachalam, J.; Ho, V.K.; et al. Association between lung compliance phenotypes and mortality in COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2021, 50, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.K.; Satapathy, A.; Naidu, M.M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Sharma, S.; Barton, L.M.; et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) – anatomic pathology perspective on current knowledge. Diagn. Pathol. 2020, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citu, C.; Citu, I.M.; Motoc, A.; Forga, M.; Gorun, O.M.; Gorun, F. Predictive Value of SOFA and qSOFA for In-Hospital Mortality in COVID-19 Patients: A Single-Center Study in Romania. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, B.; Du, H.; Lin, H.; Chen, C.; Rao, S.; et al. Performance of CURB-65, PSI, and APACHE-II for predicting COVID-19 pneumonia severity and mortality. Eur. J. Inflamm. 2021, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehryar, H.R.; Yarahmadi, P.; Anzali, B.C. Mortality predictive value of APACHE II Scores in COVID-19 patients in the intensive care unit: a cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 2464–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuk, S.; Sipahioğlu, H.; Karahan, S.; Yeşiltepe, A.; Kuzugüden, S.; Karabulut, A.; et al. Cytokine Levels and Severity of Illness Scoring Systems to Predict Mortality in COVID-19 Infection. Healthcare 2023, 11, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigmohammadi, M.T.; Amoozadeh, L.; Rezaei Motlagh, F.; Rahimi, M.; Maghsoudloo, M.; Jafarnejad, B.; et al. Mortality Predictive Value of APACHE II and SOFA Scores in COVID-19 Patients in the Intensive Care Unit. Can. Respir. J. 2022, 2022, 5129314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hu, Q.; Huang, F.; Xiong, S.; Sun, Y. The prognostic value of the SOFA score in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective, observational study. Medicine. 2021, 100, e26900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics and Comorbidities | Non-COVID (n=38) |

COVID-19 (n=32) |

p-value |

| Age (Median, IQR 25-75) | 74.5 (66.5–82.5) | 77.5 (61.3–86.0) | 0.65 |

| Male Gender n, (%) | 22 (57.9%) | 19 (59.4%) | 0.90 |

| CHF n, (%) | 24 (63.2%) | 13 (40.6%) | 0.06 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 81.7(69.3-93.2) | 73.3(63.3-97.5) | 0.77 |

| CKD/AKI n, (%) | 11 (28.9%) | 8 (25.0%) | 0.71 |

| CVD n, (%) | 7 (18.4%) | 3 (9.7%) | 0.61 |

| DM n, (%) | 19 (50.0%) | 15 (46.9%) | 0.79 |

| CAD n, (%) | 14 (36.8%) | 9 (28.1%) | 0.43 |

| COPD n, (%) | 13 (34.2%) | 17 (53.1%) | 0.11 |

| Neuropsychiatric Disorders n, (%) | 5 (13.2%) | 5 (15.7%) | 1.00 |

| Malignancy n, (%) | 6 (15.8%) | 3 (9.4%) | 0.49 |

| Parameter | Non-COVID (Median, IQR 25–75) |

COVID-19

(Median, IQR 25–75) |

p-value |

| WBC (x10³/uL) | 11.2 (8.15–17.8) | 12.0 (8.22–18.5) | 0.39 |

| Hemoglobin (Hgb, g/dL) | 12.7 (11.0–14.1) | 13.3 (10.0–14.1) | 0.86 |

| Hematocrit (Hct, %) | 39.2 (34.4–43.9) | 38.2 (31.9–44.1) | 0.49 |

| Platelet Count (Plt, x10³/uL) | 186 (155–265) | 219 (193–321) | 0.06 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 82.0 (42.3–114) | 62.0 (44.3–102) | 0.63 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 38.5 (18.8–52.8) | 38.0 (18.8–57.0) | 0.86 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.33 (0.95–1.53) | 1.25 (0.98–1.71) | 0.68 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139 (137–142) | 139 (136–143) | 0.99 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.55 (3.92–5.07) | 4.30 (3.88–4.90) | 0.55 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 161 (123–221) | 150 (119–232) | 0.80 |

| AST (IU/L) | 27.5 (18.0–67.3) | 35.0 (20.0–81.3) | 0.42 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 21.5 (15.3–38.3) | 23.0 (17.8–44.5) | 0.36 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 70.5 (17.3–148) | 106 (39.8–176) | 0.36 |

| Parameter | Non-COVID (Median, IQR 25–75) |

COVID-19 (Median, IQR 25–75) |

p-value |

| Compliance (Crs, mL/cm H₂O) | 34.0 (26.75–46.50) | 26.0 (17.8–39.0) | 0.16 |

| Elastance (cm H₂O/mL/kg) | 28.5 (19.2–33.5) | 37.0 (24.0–48.0) | 0.18 |

| Resistance (cm H₂O/L/s) | 14.0 (11.5–16.5) | 19.5 (12.7–29.5) | 0.10 |

| Tidal Volume (mL) | 422.5 (401.5–435.0) | 400 (400–450) | 0.50 |

| PEEP (cm H₂O) | 5 (5–7) | 6 (5–10) | 0.10 |

| Pmax (cm H₂O) | 35 (30–35) | 35 (30.5–37.0) | 0.13 |

| Pplat (cm H₂O) | 21 (17–26.5) | 30 (23.25–36.50) | 0.01* |

| ΔPrs (cm H₂O) | 13.50 (8.25–19.75) | 18 (11.5–23.75) | 0.30 |

| Parameter | Survivors (Median, IQR 25–75) |

Non-Survivors (Median, IQR 25–75) |

p-value |

| Compliance (Crs, mL/cm H₂O) | 29.0 (22.25–37.50) | 24.5 (22.0–38.25) | 0.56 |

| Elastance (cm H₂O/mL/kg) | 29.5 (22.75–39.5) | 28.0 (24.0–31.5) | 0.61 |

| Resistance (cm H₂O/L/s) | 15.0 (13.25–20.0) | 16.0 (13.25–19.75) | 0.80 |

| Tidal Volume (mL) | 410 (400–432.0) | 422.50 (400–450) | 0.58 |

| PEEP (cm H₂O) | 7.5 (5–8.5) | 5 (5–7) | 0.09 |

| Pmax (cm H₂O) | 35 (30–35.5) | 35 (30–35) | 0.60 |

| Pplat (cm H₂O) | 24 (19.75–31.25) | 27 (19.25–30.75) | 0.75 |

| ΔPrs (cm H₂O) | 20.50 (8.75–24.25) | 18 (13.25–25.50) | 0.97 |

| Parameter | Non-COVID |

COVID-19 | p-value | |

| APACHE-2 (± SD) | 25.3±7.20 | 27.4±8.75 | 0.27 | |

| PSI (IQR 25-75) | 116 (96–144) | 137.5 (93–147.2) | 0.34 | |

| SOFA (IQR 25-75) | 3 (3–3) | 3.5 (3.0–4.0) | 0.02 | |

| P/F ratio | 136(105-166) | 98.4(63.8-168) | 0.02 | |

| Mortality | Survivors | 11 (28.9%) | 15 (46.9%) | 0.12 |

| Non-Survivors | 27 (71.1%) | 17 (53.1%) | ||

| Parameter |

Survivors (n:15)

|

Non-Survivors (n:17) | p-value |

| APACHE-2 (± SD) | 23.67 ± 8.60 | 30.71 ± 7.66 | 0.02 |

| PSI (IQR 25-75) | 119 (79.5-143 | 142 (125-151) | 0.11 |

| SOFA (IQR 25-75) | 3 (3-4) | 4 (3-4) | 0.88 |

| P/F ratio IQR 25-75 | 102 (85.5-177) | 81.4(57.4-165) | 0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).