1. Introduction

Mechanical ventilation (MV) is one of the essential interventions commonly used on patients with Acute Respiratory Failure (RF) to keep them alive [

1]. However, MV may cause the development of ventilator-associated pneumonia, muscle mass depletion, and increased mortality[

2]. Consequently, timely and successful separation from MV support reduces the side effects and increases the chances of patients’ survival. Weaning is the process when the patient is switched from MV to spontaneous breathing. This complex procedure needs close monitoring and accurate judgments of the patient’s condition to ensure effective extubation [

3].

Weaning from the MV uses several indices that predict the patient’s chances of passing through the process. Among these output indices, the most widely used index is the Rapid Shallow Breathing Index (RSBI) [

4]. Respiratory rate to Tidal Volume (TV) in patients is measured during spontaneous breathing trials and is termed as RSBI [

5]. However, other than RSBI, there is a new valuable index known as VD/VT, utilized in evaluating the efficiency of the lungs in terms of gas exchange in RF patients. This ratio is regarded as the less frequent indicator of V/P inequality and is particularly important for hypercapnic RF. It may be used to determine the extent of the patient’s capacity for adequate oxygenation or CO2 removal without invasive MV [

6].

Although these indices are common, they can fail to predict a weaning success accurately. It has to be noted that traditional identifiers such as RSBI might not capture alterations in respiratory mechanics or pathophysiologic variation among various RF kinds [

7]. RF is classified into two categories: Type 1, Hypoxemic RF, and Type 2, Hypercapnic RF. Type 1 RF, which is associated with an impaired oxygen exchange, can occur in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), Pneumonia, and Pulmonary Embolism (PE) [

8]. Type 2 RF results from alveolar hypoventilation and may develop in conditions such as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Neuromuscular Disorders, and Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome (OHS). The severity of these two types of respiratory failure differs in their pathophysiology and responsiveness to ventilatory support, which may affect the weaning success [

9].

The past literature reviews on MV weaning strategies have highlighted some areas where there is limited understanding of differentiating the type of RF based on weaning indices. There is insufficient literature on the sensitivity and specificity of RSBI and VD/VT alone or in identifying patients with different RF subtypes, typically in patients successfully weaned from MV [

10,

11]. Research in this area has mainly focused on general patient sampling without differentiating the pathophysiology of Type 1 and Type 2 RF. This has confused the best weaning indicators for each type of RF and how to correctly use these markers to aid in clinical decision-making, especially in the Emergency Department (ED). In addition, the interactions between RSBI, VD/VT, other weaning parameters, and extubation success have not been well clarified in ED-based populations.

The present study aimed to fill these gaps by comparing the ability of RSBI and VD/VT ratios to predict successful weaning in patients with Type 1 and Type 2 RF who were successfully intubated in ED settings. This study seeks to determine the relationship between these indices, patient characteristics, and weaning success for both RF types. Identifying differences and trends relating to weaning parameters across the severity spectrum of respiratory failure will enhance best practices in the management of extubation, thus improving the quality of patient outcomes and diminishing post-extubation complications. The main innovation of this study was the detailed assessment of two common weaning measures, RSBI and VD/VT, about various categories of RF. Unlike previous studies that have targeted unspecified patient groups, this study differentiates between Type 1 and Type 2 RF, with different requirements and predictive factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was executed in the ED of a Tertiary Care Center from the year 2022 to year 2024. The study’s objective was to assess the correlation between types of RF and weaning predictors in patients who had achieved a successful process of MV weaning.

2.2. Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from the University Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Decision No: © 2021/08-11, Date: 28.04.2021). All participants or their legal attendents signed the written informed consent before enrollment. Patient data was kept confidential, anonymity was ensured, and all identifying information was omitted from the analysis section. No additional interventions were made throughout the study apart from direct clinical treatment, and no sources of bias influenced the research.

2.3. Participants and Recruitment

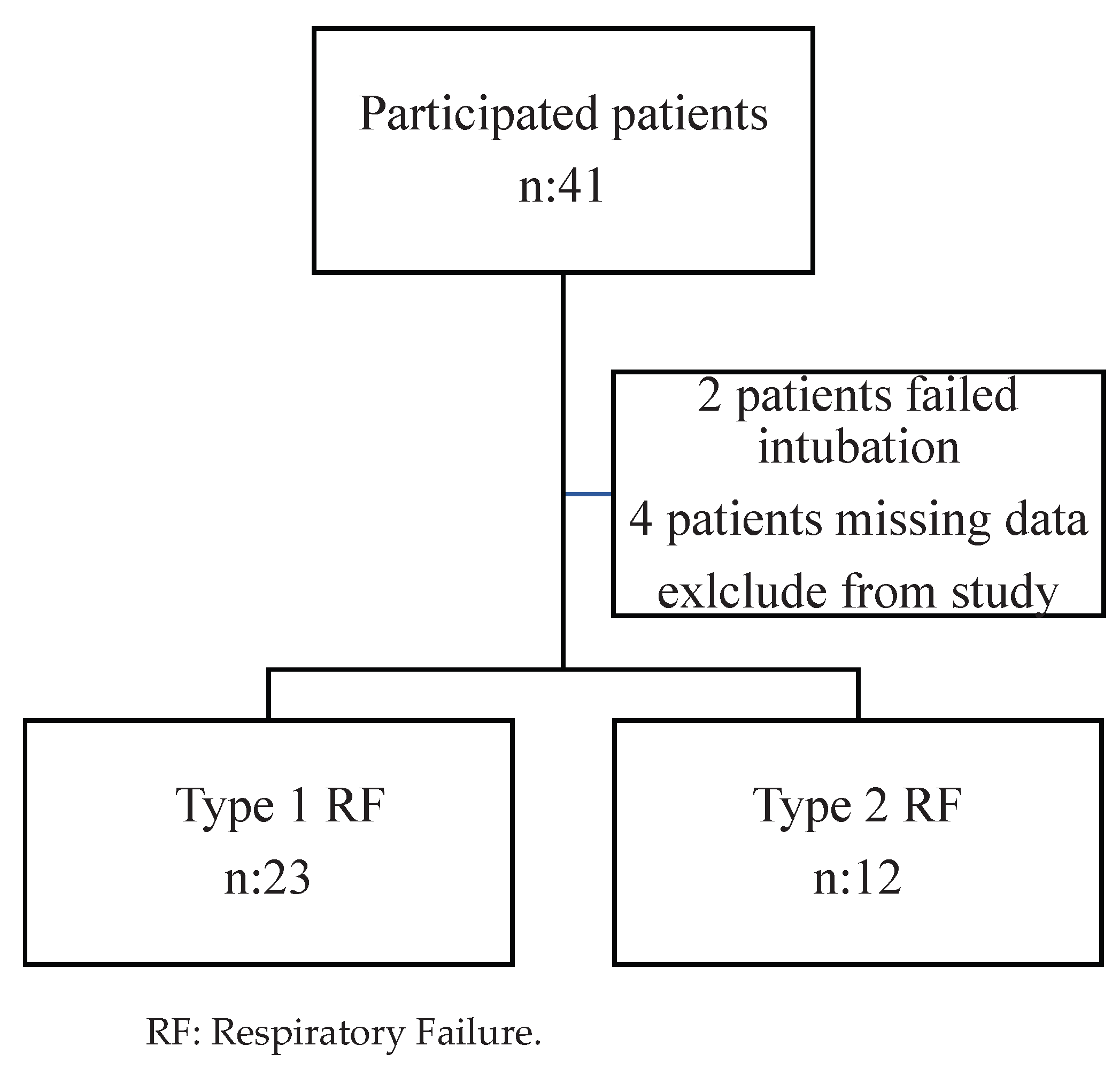

The participants in the study were adult patients who were ≥18 years old and had undergone successful MV weaning. The primary outcome was patients’ spontaneous breathing without the help of either reintubation or non-invasive ventilation for at least 48 hours after the endotracheal tube removal. A total 35 patients were initially enrolled in the study and classified into two groups: Type 1 RF, containing 23 hypoxemic patients, and Type 2 RF, containing 12 hypercapnic patients. Patients with missing data and those requiring supplemental post-extubation mechanical ventilation for 48 hours were excluded. An eligibility criteria flowchart was used to facilitate participant enrolment according to the eligibility criteria (

Figure 1).

2.4. Data Collection

The following variables were involved in the study: Age, gender, heart rate, respiratory rate, Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP), Hemoglobin (Hb), Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN), and serum creatinine at the time of admission. During the ventilation period, physiological variables measured include Positive End-Expiratory Pressure (PEEP), Peak Inspiratory Pressure (Pmax), Plateau Pressure (Pplato), TV, and static and dynamic compliance.

Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) analysis provided data on pH, arterial oxygen, and carbon dioxide tensions, Partial Arterial Oxygen Pressure (PaO₂), and Partial Arterial Carbon dioxide Pressure (PaCO₂), respectively. Weaning indices were obtained just before extubation included:

1. RSBI: Derived from respiratory rate and tidal volume and presented as a fractional value of f/VT.

2. Dead Space to Tidal Volume Ratio (VD/VT): Measured as (PaCO₂ − End TidalCO₂) / PaCO₂.

3. Integrative Weaning Index (IWI): Static compliance × Oxygen saturation SaO2/RSBI.

2.5. Outcome Measures

The objective was to compare the RSBI and the VD/VT ratios in Type 1 and Type 2 RF patients. Secondary outcome measures were the differences in other ventilatory and oxy-hemoglobin dissociation parameters, including PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio and IWI.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses described in this manuscript were conducted using the SPSS statistical tools, version 27 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Data for continuous variables were presented as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) or median Interquartile Range (IQR) based on the distribution. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between groups were made using the Student’s t-test for independent samples for continuous variables with a normal distribution and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-continuous variables with a skewed distribution. Categorical data were analyzed using the Chi-square or Fischer exact test, whichever was applied. In this study, statistical significance was determined at p-value <0.05.

3. Results

A total of 35 patients successfully weaned from mechanical ventilation were included in the study. Of these, 23 patients were classified as having Type 1 RF, and 12 had Type 2 RF T. The demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the two groups are summarized in

Table 1.

The mean age of patients in both groups was similar, for Type 1 RF =72.57±18:2 years for Type 2 RF=71.75±8.7 years, respectively, P = 0.88. Males had higher representation in both groups, 69.6% for type 1 RF and 83.3% for type 2 RF, with p = 0.37. Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) did not differ significantly between the two kinds of RF. Type 1 RF had a higher heart rate of 97.52 ± 14.19 bpm than Type 2 RF, with a heart rate of 88.25 ± 14.34 bpm, even though the difference was not statistically significant, with p = 0.07. SBP was increased in Type 2 RF patients, 130.17 ± 21.95mmHg, compared to Type 1 RF patients, 122.96 ± 14.59mmHg, but that was not statistically significant (p = 0.25).

The respiration rate, blood hemoglobin, Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine did not demonstrate any intergroup differences. These Median BUN values were 28.00 mg/dL for Type 1 RF and 37.00 mg/dL for Type 2 RF with p=0.70. The values of median creatinine were 1.16 mg/dL and 0.97 mg/dL, respectively, with p=0.56, as shown in

Table 1.

The results of MV parameters and ABG analysis are illustrated in

Table 2. The FiO₂ requirement was significantly higher in the Type 2 RF group with median= 37.50% and IQR=25.5–40 compared to the Type 1 RF group with median=30.0% and IQR= 25.5–35 (p = 0.03). Other ventilatory parameters, including PEEP, Pmax, Pplato, VT, and compliance (static and dynamic), were similar between the groups. ABG analysis revealed a significantly higher PaCO₂ level in the Type 2 RF group (mean: 49.1 ± 9.65 mmHg) compared to the Type 1 RF group (mean: 40.3 ± 4.49 mmHg) (p < 0.001), consistent with the hypercapnic nature of Type 2 RF.

Weaning indices, including RSBI, VD/VT, and PaO₂/FiO₂, are presented in

Table 3. The RSBI values were identical in both groups, with median= 40.0 and IQR: 35–40 (p = 1.00). However, the VD/VT ratio was significantly higher in the Type 2 RF group (mean 0.37 ± 0.04) compared to the Type 1 RF group with mean 0.29 ± 0.13 (p = 0.046). The PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio was significantly lower in the Type 2 RF group with a mean of 169 ± 49.6 mmHg compared to the Type 1 RF group with a mean of 244 ± 95.6 mmHg (p = 0.017). Other indices, including the IWI and PaO₂/PAO₂ ratio, showed no statistically significant differences between the groups.

4. Discussion

MV is mandatory for patients with acute RF, and prolonged use has been shown to increase the risk of complications in the patients [

12]. Weaning off the ventilator, also known as weaning, is vital in the recovery process. Subsequently, identifying the patients through the indices RSBI and VD/VT is crucial for determining weaning success [

13]. In this study, the VD/VT ratio was significantly higher in patients with Type 2 RF. This finding suggests increased physiological dead space may be related to impaired gas exchange efficiency in hypercapnic patients [

14,

15]. The increase in the dead space fraction is primarily due to reduced alveolar ventilation, which becomes clinically significant in conditions such as chronic COPD that lead to hypercapnia [

16].

However, no differences were observed in RSBI values between the Type 1 and Type 2 RF groups, suggesting that RSBI is less useful in patients with hypercapnia. RSBI scored as the respiratory rate divided by the TV reflects the patient’s respiratory workload, although its prognostic value is limited due to ventilation-perfusion mismatch in the presence of elevated CO₂ [

17,

18]. As Santos et al. (2021) observed that the predictive indices, including the IWI, poorly predicts the extubation outcomes. This is consistent with the current results regarding the limitations of conventional indices such as RSBI, particularly in patients with Type 2 RF and poor gas exchange [

19]. These results demonstrate that traditional measures, including RSBI, may be less effective in some patient populations, and measures reflecting gas exchange efficiency, such as VD/VT, may play a significant role in the weaning process [

20].

In the present study, the VD/VT ratio was higher in the patients with Type 2 RF than in the patients with Type 1 RF (0.37 ± 0.04 and 0.29 ± 0.13; p = 0.046). This finding corresponds to the observation made by Lazzari et al. (2022), who noted that enhanced physiological dead space volume is related to reduced ventilation effectiveness [

21]. Hypercapnic individuals demonstrate reduced alveolar ventilation, producing a high VD/VT ratio due to ventilation-perfusion inequality. Likewise, Jiang et al. (2025) showed that using VD/VT ratios of greater than 0.6 tends to provoke higher mortality, indicating clinical relevance. The elevated VD/VT ratio in the Type 2 RF group aligns with this observation and highlights their impaired gas exchange efficiency [

22]. The PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio showed a significant difference between the two groups, with PaO₂/FiO₂ of Type 1 RF 244±95.6 and that of Type 2 RF being 169±49.6(p=0.017). This result affirms the study conducted by Abbott et al., 2024 where findings indicated enhanced gas exchange discrepancies in hypoxemic RF [

23]. Chiumello et al. (2024) stated that a ratio lower than 200 provides poor clinical outcomes. The decreased PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio observed in the Type 2 RF group highlights the severity of gas exchange impairment in hypercapnic patients [

24].

The mean of the RSBI was 40.0 and did not differ significantly between the groups p=1.00. The above result indicates that RSBI has poor prognostic value in hypercapnic patients. Specifically, Ghianiet al.(2024) discussed that RSBI may be less accurate in the patients, introducing newer indices, including IWI, which reflects compliance, oxygenation, and breathing indices [

25]. Sterr et al. (2024) noted that measures like RSBI, PaO₂/FiO₂, and diaphragm ultrasonography have been extensively tested concerning weaning failure [

26]. As the study reported, impaired gas exchange and respiratory mechanics were indicated to be significant contributors to Type 2 RF patients. In the present study, IWI values did not show significant differences between the groups (79.3 ± 32.5 in Type 1 RF vs. 70.8 ± 30.7 in Type 2 RF; p=0.45). Moreover, PaO₂/FiO₂ and RSBI values were consistent with Kamal et al. (2023), who demonstrated that combining these parameters into an integrative weaning index improves predictive accuracy [

27].

The significantly higher VD/VT ratio observed in Type 2 respiratory failure patients reflects impaired gas exchange efficiency, primarily due to increased physiological dead space. This finding is consistent with the observations of Akella et al. (2022), who emphasized the roles of increased airway resistance, intrinsic PEEP, and diaphragmatic dysfunction in weaning failure [

28]. Depta et al. (2024) also highlighted the clinical relevance of VD/VT in assessing ventilation-perfusion mismatch and overall ventilatory efficiency [

29]. VD/VT is particularly useful in conditions such as COPD and other hypercapnic states, where dead space ventilation is elevated. In support of this, Depta et al. (2024) demonstrated that reductions in VD/VT during PEEP titration reflect improved gas exchange. These insights underscore that factors like alveolar hypoventilation, ventilation-perfusion inequality, and impaired CO₂ clearance contribute to hypercapnia, making VD/VT a valuable indicator in evaluating weaning readiness.

VD/VT thereby serves as a direct marker of ventilatory efficiency in patients with hypercapnia and plays a critical role in ensuring adequate oxygenation during the weaning process. In contrast to traditional indices like RSBI, which primarily assess respiratory workload but fail to capture gas exchange abnormalities [

30], VD/VT reflects the efficiency of alveolar ventilation. This makes it a superior predictor of weaning success in hypercapnic patients. These findings align with studies suggesting that combining gas exchange parameters with respiratory mechanics improves the predictive accuracy of weaning indices [

31,

32].

Although RSBI has historically been considered a key predictor of weaning success [

33], our findings and previous literature suggest it may not be sufficient alone in hypercapnic patients due to its inability to reflect gas exchange abnormalities [

34]. Recent developments such as the Integrative Weaning Index (IWI), which combines static compliance, oxygenation, and RSBI, have shown promise in enhancing weaning prediction [

8]. Although no significant difference in IWI was observed between groups in our study, combining it with VD/VT may improve accuracy, especially in hypercapnic patients. This is further supported by Chuang et al. (2020), who demonstrated that an elevated VD/VT ratio is associated with ventilatory inefficiency and impaired gas exchange in patients with COPD, a common cause of hypercapnic respiratory failure [

35].

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

The study has several strengths and gives individual assessments of the RSBI, IWI and VD/VT ratios. It provides valuable information regarding the usefulness of these indices for predicting successful weaning in patients with different types of RF. The prospective design also effectively minimizes potential biases within the data collection process. The inclusion of full ventilatory parameters and indices of gas exchange, also increases the strength of the analysis. The novelty lies in the fact that this study is the first to provide specific insight into the issues encountered in hypercapnic patients and aims to give useful suggestions to ensure improved strategies for the weaning process.

There are a few limitations that must be addressed. Small sample sizes, particularly in the Type 2 RF group, may reduce the generability of the findings. The study does not assess long-term outcomes such as post-extubation supportive care.

5. Conclusion

This study confirmed that despite getting similar RSBI and IWI at the two RF types, patients with type 2 RF most likely have worse VD/VT ratios and lower PaO₂/FiO₂ implying poor gas exchange and reduced alveolar ventilatory efficiency. These results underscore the importance of integrating VD/VT into clinical practice in addition to the conventional markers of weaning early, especially in the presence of hypercapnia. Based on these findings, future studies using a larger sample size must confirm these findings and fine-tune the weaning process to increase the patients’ positive prognosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., H.Y., and A.H.; Methodology, M.K., H.Y., and S.E.; Data Curation, M.K. and H.Y.; Formal Analysis, M.K., H.Y., and S.E.; Investigation, M.K., H.Y., A.H., and A.C.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.K., H.Y., and A.H.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.K., H.Y., A.H., A.C., and M.U.; Supervision, S.E. and M.U.; Project Administration, M.K. and M.T. All authors have reviewed, revised, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All authors declared that the research was conducted according to the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki “Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects.” This study was approved by the Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Kütahya Health Sciences University (Approval No: 2021/08-11, Date: 28.04.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to this study was based on medical record review and all individuals’ information did not appear in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ABG |

Arterial Blood Gas |

| ARDS |

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| BUN |

Blood Urea Nitrogen |

| CDyn |

Dynamic Compliance |

| CStat |

Static Compliance |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| ED |

Emergency Department |

| EtCO₂ |

End-Tidal Carbon Dioxide |

| VD/VT |

Dead Space to Tidal Volume Ratio |

| FiO₂ |

Fraction of Inspired Oxygen |

| Hb |

Hemoglobin |

| IWI |

Integrative Weaning Index |

| MV |

Mechanical Ventilation |

| OHS |

Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome |

| PaCO₂ |

Partial Arterial Carbon Dioxide Pressure |

| PaO₂ |

Partial Arterial Oxygen Pressure |

| PAO₂ |

Partial Alveolar Oxygen Pressure |

| PEEP |

Positive End-Expiratory Pressure |

| Pmax |

Peak Inspiratory Pressure |

| Pplato |

Plateau Pressure |

| RF |

Respiratory Failure |

| RR |

Respiratory Rate |

| RSBI |

Rapid Shallow Breathing Index |

References

- Battaglini, D.; Sottano, M.; Ball, L.; Robba, C.; Rocco, P.R.M.; Pelosi, P.; et al. Ten golden rules for individualized mechanical ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Intensive Med. 2021, 1, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.; Kim, Y.; Cho, J.; Park, J.; Lee, H.; Ryu, J.; et al. Impact of the timing of invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with sepsis: A multicenter cohort study. Crit. Care, 2024; 28, 297. [Google Scholar]

- Parada-Gereda, H.M.; Higuera-Lucero, D.A.; González-Calatayud, D.M.; Soriano-Ardila, M.L.; Domínguez, J.D.; Durán-Cárdenas, L.E.; et al. Effectiveness of diaphragmatic ultrasound as a predictor of successful weaning from mechanical ventilation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care. 2023, 27, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamil, P.; Jamil, K.; Roshni, P.; Mohammed, A.; Thomas, R.; Krishna, B.; et al. Prediction of weaning outcome from mechanical ventilation using diaphragmatic rapid shallow breathing index. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 26, 1000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swamy, A.H.M.; Kumar, P.S.; Reddy, K.N.; Nair, S.; Joseph, A.; Thomas, M.; et al. Rapid Shallow Breathing Index and ultrasonographic diaphragmatic parameters as predictors of weaning outcome in critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation. Ann. Afr. Med. 2025, 24, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartos, S.; Svoboda, M.; Brat, K.; Lukes, M.; Predac, A.; Homolka, P.; et al. Causes of ventilatory inefficiency in lung resection candidates. ERJ Open Res. 2024, 10, 00792–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakti, P.P.; Anjarwani, S. Weaning failure in mechanical ventilation: A literature review. Heart Sci. J. 2023, 4, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nanayakkara, B.; McNamara, S. Pathophysiology of chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure. Sleep Med. Clin. 2024, 19, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, A.R.; Alrashidi, Y.; Mahmoud, A.; Taqi, M.; Farhan, H.; Saleh, R.; et al. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (Pickwickian syndrome): A literature review. Respir. Sci. 2024, 5, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eser, P.; Käesermann, D.; Calamai, P.; Rossi, S.; Muriel, A.; Berton, E.; et al. Excess ventilation and chemosensitivity in patients with inefficient ventilation and chronic coronary syndrome or heart failure: A case-control study. Front. Physiol. 2025, 15, 1509421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, J.C.d.S.; Oliveira, K.A.R.d.; Santos, A.S.S.; Ferreira, A.M.R.; Lima, R.C.; Silva, M.G.; et al. Extubation in the pediatric intensive care unit: Predictive methods—An integrative literature review. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensiva. 2021, 33, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racca, F.; Longhitano, Y.; Viarengo, A.; Scotto, R.; Ball, L.; Pelosi, P.; et al. Invasive mechanical ventilation in traumatic brain injured patients with acute respiratory failure. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials. 2023, 18, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.-Q.; Si, Q.; Feng, Y.-P.; Guo, J.; Jiang, L.-P. Research progress in pulmonary rehabilitation in patients who have been weaned off mechanical ventilation: A review article. Technol. Health Care. 2024, 32, 2859–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonifazi, M.; Romitti, F.; Busana, M.; Palumbo, M.M.; Steinberg, I.; Gattarello, S.; et al. End-tidal to arterial PCO₂ ratio: A bedside meter of the overall gas exchanger performance. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2021, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj, R.; Comellini, V.; Bertelli, M.; Tonetti, T.; Vasques, F.; Romitti, F.; et al. Ventilatory ratio, dead space, and venous admixture in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Br. J. Anaesth. 2023, 130, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P.D.; Malhotra, A.; Prisk, G.K. Using pulmonary gas exchange to estimate shunt and dead space in lung disease: Theoretical approach and practical basis. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 132, 1104–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, Y.M.; Fernández, A. Weaning strategy of mechanical ventilation in prolonged mechanical ventilation in children. In Prolonged and Long-Term Mechanical Ventilation in Children; Springer, 2024, pp. 131–162.

- Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Moosavi, S.M.; Rahimibashar, F.; Shojaei, S.; Banach, M.; Miller, A.C.; et al. New integrated weaning indices from mechanical ventilation: A derivation-validation observational multicenter study. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 830974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.A.d.; Silva, M.A.; Oliveira, A.L.; Lima, L.N.; Fernandes, A.C.; Souza, J.P.; et al. Postextubation fluid balance is associated with extubation failure: A cohort study. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensiva. 2021, 33, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, V.; Iyer, V.N.; Leung, G.; DeMerle, K.M.; Patel, B.K.; Gajic, O.; et al. The usefulness of the rapid shallow breathing index in predicting successful extubation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2022, 161, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzari, S.; Bonifazi, M.; Romitti, F.; Palumbo, M.M.; Busana, M.; Steinberg, I.; et al. End-tidal to arterial PCO₂ ratio as guide to weaning from venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Duan, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Time-varying intensity of ventilatory inefficiency and mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann. Intensive Care. 2025, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, M.; Pereira, S.M.; Sanders, N.; Girard, M.; Sankar, A.; Sklar, M.C. Weaning from mechanical ventilation in the operating room: A systematic review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2024, 133, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiumello, D.; Fioccola, A. Recent advances in cardiorespiratory monitoring in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. J. Intensive Care. 2024, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiani, A.; Muttini, S.; Longhini, F.; Della Corte, F.; Garofalo, E.; Navalesi, P.; et al. Mechanical power density, spontaneous breathing indexes, and weaning readiness following prolonged mechanical ventilation. Respir. Med. 2025, 107943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 26 Sterr, F.; Reintke, M.; Bauernfeind, L.; Senyol, V.; Rester, C.; Metzing, S.; et al. Predictors of weaning failure in ventilated intensive care patients: A systematic evidence map. Crit. Care. 2024, 28, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.; Sengupta, S. Diaphragmatic ultrasound: A new frontier in weaning from mechanical ventilation. Indian J. Anaesth. 2023, S205–S207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akella, P.; Voigt, L.P.; Chawla, S. To wean or not to wean: A practical patient-focused guide to ventilator weaning. J. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 37, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depta, F.; Gentile, M.A.; Kallet, R.H.; Donic, V.; Zdravkovic, M. Evaluation of time constant, dead space and compliance to determine PEEP in COVID-19 ARDS: A prospective observational study. Signa Vitae. 2024, 20, 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnaik, A.P.; Venkataraman, S.T.; Kuch, B.A. Mechanical Ventilation in Neonates and Children: A Pathophysiology-Based Management Approach; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, C.E.; Thomas, A.M.; West, D.A.; Gomez, R.; Smith, J.A.; Carroll, R.G.; et al. Increased intrapulmonary shunt and alveolar dead space post-COVID-19. J. Appl. Physiol. 2023, 135, 1012–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.A. Ventilation/carbon dioxide output relationships during exercise in health. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2021, 30, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.L.; Tobin, M.J. A prospective study of indexes predicting the outcome of trials of weaning from mechanical ventilation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 1445–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Choi, Y.H.; Kwon, H.Y.; Cho, J.H.; et al. Biosignal-based digital biomarkers for prediction of ventilator weaning success. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 9229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, M.-L.; Lin, I.-F.; Cheng, Y.-M.; Huang, S.-F.; Wang, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-H. Use of Ventilatory Equivalent for CO₂ and Physiologic Dead Space Ratio to Assess Impaired Ventilatory Efficiency and Dynamic Hyperinflation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).