Explanation of Galactic Habitability Distribution Parameters

The parameters defined in

Table 6 specify the spatial model of habitability within the Milky Way, with each quantity representing either a spatial constraint or a normalization relevant to estimating the total number of habitable planets. The radial peak

denotes the galactocentric distance where the probability density of habitability is maximal, reflecting optimal conditions for stable star systems and efficient planet formation. The standard deviation

governs the width of this distribution, determining how sharply habitability falls off with distance from the galactic center. The metallicity gradient

captures the exponential decline in heavy element abundance with galactocentric radius, which directly impacts the formation likelihood of terrestrial planets. Vertically, the scale height

describes the thickness of the galactic disk within which most habitable systems are expected to reside, consistent with the distribution of stellar populations. Finally, the total number of habitable planets is estimated as

, derived from integrating the spatial habitability model over the galactic volume and combining it with observational data on planet occurrence rates. These parameters collectively inform spatial probability distributions used in galactic-scale models of biosphere likelihood, and they feed directly into integrals over stellar density and metallicity that underpin the habitability estimates.

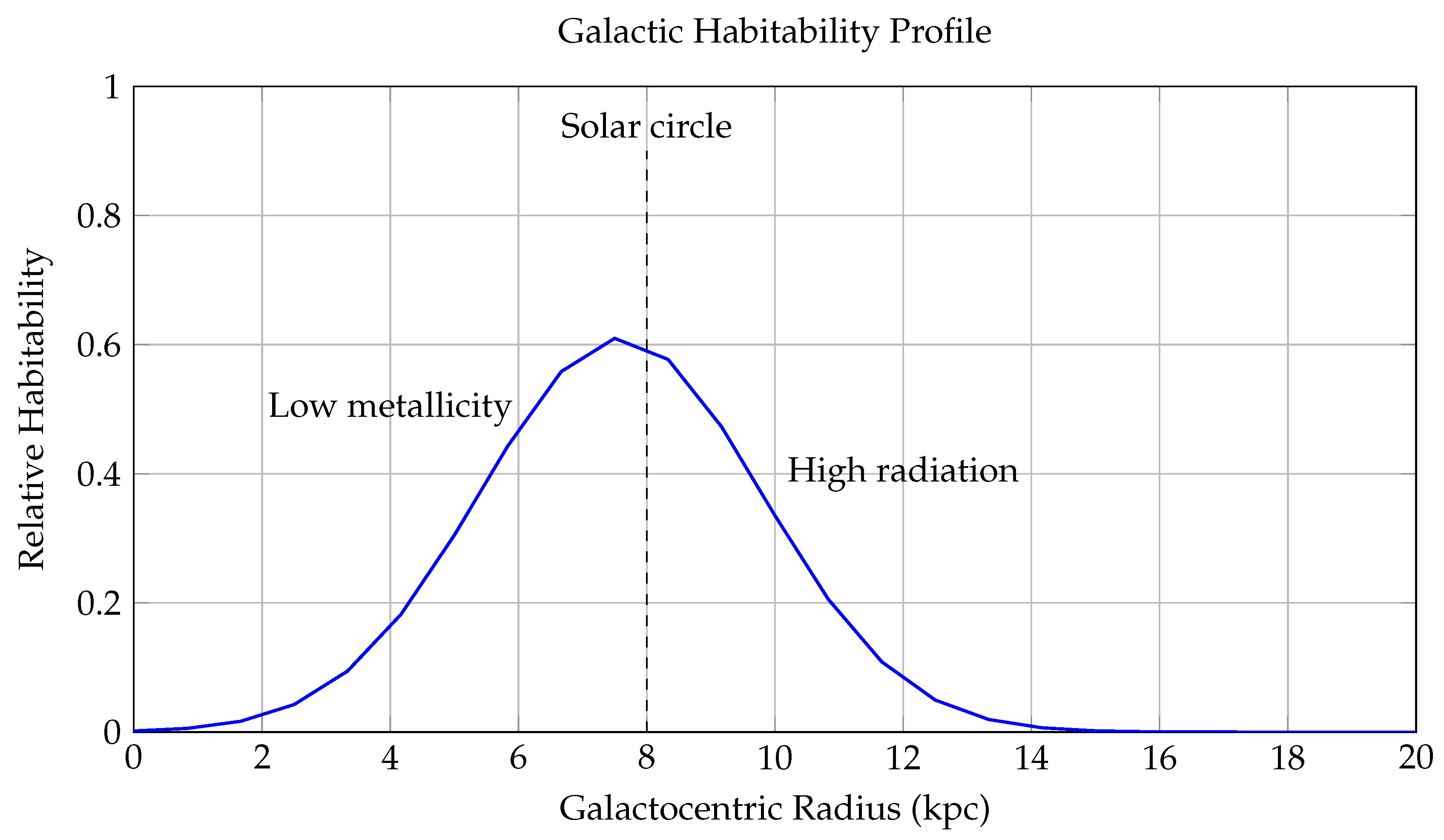

Figure 9.

Galactic Habitability Profile as a Function of Galactocentric Radius.

Figure 9.

Galactic Habitability Profile as a Function of Galactocentric Radius.

This figure models the relative probability of planetary habitability across different galactocentric radii (in kiloparsecs, kpc), capturing the combined effects of metallicity, stellar density, and supernova rate on the viability of life-supporting environments within a Milky Way–like galaxy.

The blue curve represents the habitability function:

where: -

R is the distance from the galactic center in kpc, -

is the peak of habitability, corresponding to the **solar circle**, -

controls the width of the Gaussian, -

captures the decline in habitability with decreasing metallicity in the outer disk.

The model reflects two dominant opposing factors: 1. **Inner Galaxy Suppression** (): High stellar density leads to increased radiation exposure, close-passing stars, and frequent supernova events, all of which can destabilize planetary atmospheres and biospheres. 2. **Outer Galaxy Suppression** (): Lower metallicity results in fewer rocky planets and weak retention of atmospheres, reducing the likelihood of forming Earth-like planets and biochemically rich environments.

Annotations include: - A **dashed line** at , identifying the Sun’s location in the Milky Way—very near the habitability peak. - A **Gaussian envelope** centered at the solar radius, representing the reduced supernova threat away from the galactic center. - A **linear metallicity decay**, reducing in the outer regions.

This framework gives rise to the concept of the **Galactic Habitable Zone (GHZ)**—an annular region between approximately 6–10 kpc where the balance of heavy elements, stellar stability, and long-term climate regulation is optimal for life. The model aligns with observed exoplanet distributions, which show a clustering of rocky planets and biosignature candidates in this region.

Integrating over the galactic disk yields total habitable planets:

in the Milky Way.

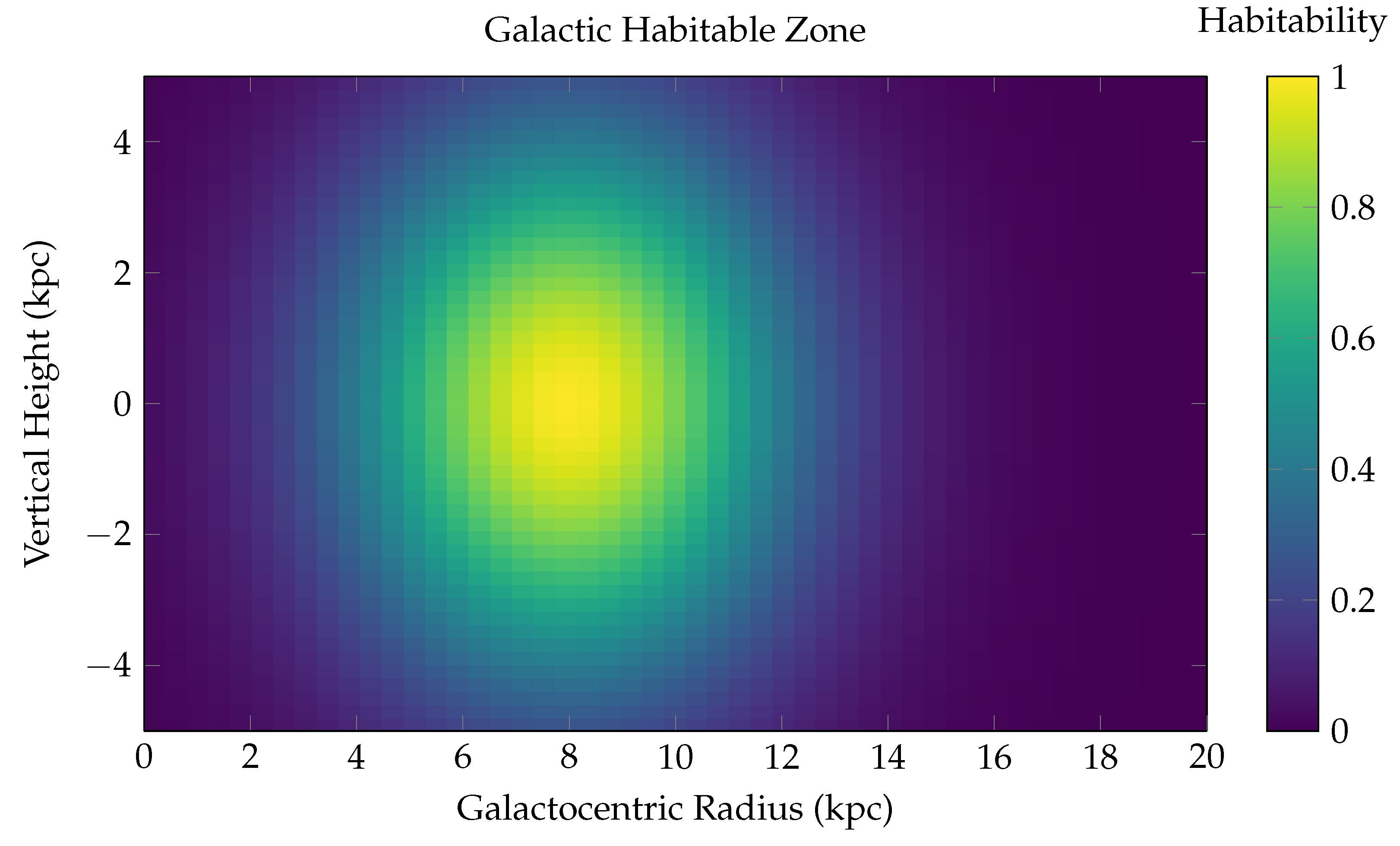

Figure 10.

Two-Dimensional Spatial Distribution of Habitability in the Milky Way Disk.

Figure 10.

Two-Dimensional Spatial Distribution of Habitability in the Milky Way Disk.

This surface plot represents the **Galactic Habitable Zone (GHZ)** as a function of both **radial distance** from the galactic center (x-axis, in kiloparsecs) and **vertical height** from the galactic midplane (y-axis). The habitability score is visualized via a color-coded heatmap using the viridis colormap, with peak values shown in yellow-green and low values in dark blue. The z-axis (represented via color) denotes the relative habitability probability, normalized between 0 and 1.

The model used is:

where: -

R is the galactocentric radius, -

z is the vertical height above or below the galactic midplane, -

is the radius of peak habitability (the solar circle), -

encodes the radial and vertical scale over which habitability declines.

Physical Interpretation: - **Radial dependence**: The highest habitability is concentrated in an annular region around 6–10 kpc from the galactic center, consistent with prior GHZ models. Interior to this zone, radiation hazards (supernovae, gamma-ray bursts) suppress biospheric development. Exterior to it, metallicity becomes insufficient for rocky planet formation. - **Vertical dependence**: The habitability sharply decreases with distance from the galactic plane (), due to decreasing stellar density, less shielding from cosmic rays, and instability of planetary orbits caused by disk heating and halo perturbations.

This 2D map effectively captures the **thermo-chemodynamic sweet spot** where life is most likely to evolve and persist in a Milky Way–like galaxy. The highest habitability regions appear as a **torus-like annulus** centered at 8 kpc in radius and confined tightly around the galactic midplane ( kpc).

Such spatial models are crucial for: - Prioritizing exoplanet searches (e.g., via Gaia, PLATO, JWST), - Modeling panspermia mechanisms, - Quantifying the spatial resolution of SETI detection strategies.