1.0. Introduction

The Infinite Universe Framework (IUF) offers a comprehensive alternative to standard cosmological models by proposing that the universe is infinite in both space and time and governed by consistent physical laws rather than by initial conditions or boundary-driven dynamics. Rather than relying on metric expansion, dark energy, or inflation, the IUF explains observed redshift and background radiation through well-characterized physical processes occurring within a structured, evolving cosmos.

This framework integrates two core components:

The Physical Universe Theory (PUT), which holds that the cosmos is structured, eternal, and regulated by persistent physical laws across all scales and epochs. Under PUT, large-scale coherence and thermodynamic cycling emerge from the interaction of matter and radiation over infinite durations, without requiring singular origins, inflation, or cosmic boundaries.

The

Cumulative Photon Energy Transfer (C-PET) model, which proposes that redshift arises from small, cumulative energy losses experienced by photons as they traverse intergalactic media. These losses result from infrequent, direction-preserving interactions with plasma, dust, and filamentary structures, an interpretation supported by Voyager plasma data [

4] and consistent with known principles of quantum electrodynamics.

This model further introduces the Photon–Medium Microwave Thermal Field (PMMTF) as a testable hypothesis: a diffuse microwave background that may emerge from the cumulative re-radiation of energy lost by photons during intergalactic transit. Rather than attributing the microwave background to a primordial origin event, the PMMTF hypothesis proposes a continuous, distributed energy exchange process. Whether this mechanism can account for the observed precision, isotropy, and energy density of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) is examined in

Section 7 and

Appendix E.

The IUF thus seeks to reinterpret cosmological observables, not by rejecting the data, but by reexamining the underlying assumptions. It draws upon redshift surveys, high-resolution galaxy observations [

1,

2,

3], interstellar plasma measurements [

4], and cosmic structure mapping [

10] to propose a model grounded in known physics and falsifiable predictions. By replacing speculative early-universe constructs with physically observable, cumulative interactions, the IUF opens a path toward a cosmological theory rooted in physical law rather than untestable conditions.

While this manuscript proposes a comprehensive framework, several physical derivations, particularly the quantum mechanical foundations of the C-PET interaction, remain open areas for continued development and future collaboration.

This framework is presented not as a definitive replacement for ΛCDM, but as a physically grounded and testable hypothesis that invites collaborative scrutiny, empirical validation, and iterative refinement. All simulation parameters and computational protocols are documented to enable independent replication and critical evaluation.

2.0 Core Assumptions of The Infinite Universe Framework (IUF)

The Infinite Universe Framework (IUF) is founded upon a set of core assumptions that distinguish it from expansion-based cosmologies such as the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (ΛCDM) model, which is closely associated with the Big Bang theory. These IUF assumptions are grounded in observed phenomena, supported by known physical laws, and deliberately exclude speculative constructs not directly confirmed by empirical evidence.

The Universe is Infinite in Space and Time IUF assumes that the cosmos has no spatial boundary, origin point, or temporal beginning. This infinite, eternal structure contrasts with the finite-age assumptions of Big Bang cosmology. Structure formation, redshift, and background radiation can be explained without invoking a singular origin or inflationary episode.

Cosmological Observations Arise from Physical Interactions, Not Expansion Redshift, surface brightness dimming, and time dilation are treated as emergent effects of photon interactions with cosmic media, rather than consequences of metric expansion. The observed coherence of spectral lines across vast distances supports the hypothesis that photons are not stretched by space itself but undergo cumulative, non-scattering energy transfer through infrequent interactions with intervening media. In this view, the same underlying mechanism responsible for redshift also contributes energy to the intergalactic medium, which eventually re-emits it as a diffuse, thermalized background field, characterized within IUF as the Photon-Medium Microwave Thermal Field (PMMTF), rather than as a relic of a primordial explosion.

The Cosmic Medium Is Structurally Rich and Intermittent IUF posits that the universe is permeated by diverse, low-density structures, such as plasma [

4], filaments [

10], circumgalactic media (CGM), and interstellar matter [

21,

22,

151], which cumulatively induce photon energy transfer over cosmological distances. These structures are unevenly distributed, and

turbulent processes [

41]

in denser regions such as the interstellar medium may locally enhance photon–medium coupling, reinforcing the logic of the Segmented Medium Model (SMM), which models redshift accumulation as a function of local medium properties.

Redshift Is Accumulative and Compounding Rather than occurring instantaneously or through a global scale factor, as in the ΛCDM model [

42,

43,

44], redshift in IUF accumulates through a series of infrequent interactions with intervening media. This allows for nonlinear scaling, logarithmic or exponential, depending on the distribution and density of cosmic structures along a photon's path.

No Inflation, Dark Energy, or Dark Matter Are Required IUF does not rely on inflation [

13,

14,

15,

110], dark energy, or dark matter as explanatory mechanisms. Where ΛCDM invokes these constructs to align theory with observation, IUF contends that the phenomena attributed to them can be explained through established physical processes occurring within an infinite and structured universe.

Known or Discoverable Physical Laws Apply Universally IUF assumes that the laws of physics, both currently known and those that may be discovered, apply uniformly across all space and time. This assumption rejects the need for exceptional rules or speculative physics to explain ancient or distant phenomena, asserting instead that cosmic processes emerge from consistent, universal principles.

These six assumptions form the theoretical foundation of IUF's two primary components: the Physical Universe Theory (PUT) and the Cumulative Photon Energy Transfer (C-PET) model. They also define the framework's falsifiability criteria: if redshift, surface brightness dimming, time dilation, and background radiation (characterized here as the PMMTF) cannot be reproduced through cumulative photon–medium interactions across structured cosmic media in an infinite universe, then the framework must be revised, or rejected.

3.0. The Physical Universe Theory (PUT)

The Physical Universe Theory (PUT), as a foundational component of the Infinite Universe Framework (IUF), asserts that the universe has no beginning, no end, and no spatial boundary. Time and space extend infinitely in all directions and epochs. Rather than originating from a singularity or explosive event [

13,

14,

15], the universe exists as an eternal and unbounded continuum of matter, energy, and physical processes.

This view rejects the need for a primordial origin moment or inflationary expansion [

13,

14,

15]. Instead, cosmic structure is understood as continually evolving and reorganizing within localized environments governed by universally applicable physical laws, consistent across space and time. Structures form, interact, and transform continuously across all epochs, unbounded by the constraints of a finite cosmological timeline [

42,

43,

44]. The Physical Universe Theory is fully compatible with the C-PET mechanism described in

Section 2.0, which offers a unified explanation for both redshift and the CMB, characterized within this framework as the Photon–Medium Microwave Thermal Field (PMMTF).

PUT finds support in several observational anomalies that challenge the ΛCDM model associated with the Big Bang theory. Among them:

Furthest Observed Galaxies (FOGs): High-redshift galaxies detected by JWST [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18] exhibit unexpectedly mature characteristics, quiescence, high stellar mass, and disk-like structures [

71,

72,

73,

74], despite being positioned at redshifts (e.g.,

z ≈ 10–14) where ΛCDM would predict only nascent formation [

58,

59,

60].

Large-Scale Structures: The existence of cosmic megastructures, such as the Big Ring and Giant Arc [

20], appear to exceed the scale limits of homogeneity expected in a finite, expanding universe [

42,

43,

44].

Temporal Symmetry: PUT offers a cosmological model that is time-symmetric at large scales, avoiding the philosophical and thermodynamic tensions present in ΛCDM's portrayal of a universe that begins in a highly ordered, low-entropy state [

96,

97,

98].

These observations are explored further in

Section 5.0, which presents detailed case studies of high-redshift galaxies and redshift modeling scenarios that support the Physical Universe Theory. These include comparative analyses of structural maturity and elemental composition [

55,

56] , as well as quantitative simulations of cumulative redshift based on the segmented distribution of cosmic media [

21,

22,

23].

4.0. Cumulative Photon Energy Transfer (C-PET) Model

The Cumulative Photon Energy Transfer (C-PET) model proposes that cosmological redshift arises from cumulative photon energy loss via non-scattering interactions with the cosmic medium. These interactions occur as photons traverse intergalactic and interstellar gases, plasma, dust, filaments, and circumgalactic structures [

4,

21,

22,

31,

32], media that, though sparse, extend across cosmological distances and exhibit measurable structure [

10,

20].

In later modeling sections, the term "attenuation" is used to describe this process quantitatively. Unless otherwise specified, it refers to the directional, non-scattering reduction of photon energy per unit distance, a specific form of photon energy transfer that preserves spectral coherence and trajectory, distinct from classical absorption or scattering.

Throughout this manuscript, the term photon energy transfer (PET) refers to the overall mechanism by which photons interact with cosmic media across vast distances. The term photon energy loss (PEL) is used more specifically to describe the gradual reduction in photon energy that produces redshift. Both concepts operate through the same class of cumulative, infrequent, direction-preserving interactions described in the C-PET model.

While C-PET is used here primarily to explain redshift, the cumulative energy loss it describes may have broader implications. One such hypothesis, explored in

Section 7 and

Appendix E, is that the energy transferred into the medium over time may contribute to a diffuse microwave background field. This Photon–Medium Microwave Thermal Field (PMMTF) is presented as a testable byproduct of C-PET rather than a definitive explanation of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) [

91,

94,

104]. Whether such a field can match the spectral precision, isotropy, and energy density of the observed CMB remains an open question subject to quantitative evaluation.

4.1. Known Photon Behavior in Intergalactic Media

Rather than invoking space expansion [

42,

43,

44], C-PET asserts that redshift accumulates, potentially in nonlinear or compounding fashion, over vast distances as photons traverse a heterogeneous cosmic medium [

21,

22]. These infrequent interactions reduce photon energy while preserving directional coherence and spectral integrity, allowing distant galaxies to remain sharply imaged and spectroscopically resolved.

The energy transferred to the medium is gradually absorbed and thermalized, then re-emitted isotropically over cosmological timescales. This process gives rise to a diffuse, thermal radiation field consistent with the observed properties of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which C-PET recharacterizes as the Photon–Medium Microwave Thermal Field (PMMTF). This model requires neither a primordial origin nor a hot recombination epoch [

13,

14,

15].

C-PET accounts for several key cosmological observations:

Redshift: Accumulates due to photon–medium interactions, not metric expansion [

42,

43,

44].

Surface Brightness Dimming: Arises from cumulative energy transfer and refractive delay, not geometric dilution [

49].

Spectral Line Preservation: Maintained by non-scattering interactions [

103], explaining the clarity of high-z galaxy spectra.

The CMB / PMMTF: Emerges as a diffuse, thermalized field from long-term photon energy transfer, not a remnant of a primordial explosion [

13,

14,

15].

C-PET assumes that known or discoverable physical laws apply uniformly across time and space. The Segmented Medium Model (SMM), introduced in later sections, provides a structured framework for modeling how varying cosmic media contribute to redshift accumulation, enabling testable predictions without invoking expansion-based mechanisms [

42,

43,

44].

4.2. Physical Mechanism of Non-Scattering Photon–Medium Energy Transfer

The C-PET model proposes that cosmological redshift results from cumulative, non-scattering interactions between photons and the intergalactic medium (IGM). Unlike classical scattering (e.g., Thomson or Compton) [

103], which alters photon direction and broadens spectra, the C-PET mechanism involves forward-directed, coherence-preserving energy loss.

This process may resemble stimulated Raman scattering or inverse bremsstrahlung in low-density plasmas, where free electrons absorb minute amounts of photon energy without disrupting phase or direction. Although each interaction transfers only a tiny fraction of energy

1

their cumulative effect over billions of light-years yields significant redshift.Quantum electrodynamics allows for such interactions in weakly ionized media [

7,

26,

30,

39,

103], especially under fluctuating electromagnetic fields. Laboratory analogs, though rare and subtle, support the plausibility of this mechanism under extended path lengths. Importantly, it preserves spectral sharpness and coherence [

103], consistent with high-resolution JWST observations of

z > 10 galaxies [

1,

2,

3,

82,

83,

84].

This physical basis underpins the broader C-PET model, enabling it to reproduce redshift accumulation without scattering, spectral distortion, or invoking cosmic expansion.

Several known or hypothesized mechanisms may contribute to non-scattering photon energy transfer in low-density intergalactic media:

Inverse bremsstrahlung [

29]:gradual photon energy absorption by free electrons in the presence of ions.

Stimulated Raman-like processes [

24,

25]: inelastic forward energy coupling to medium fluctuations.

Forward coherent plasma coupling [

27,

28]: low-loss transfer to collective plasma wave modes, preserving directional coherence.

Cumulative Compton-like drift [

103]:marginal directional energy loss from low-angle interactions sustained over cosmological distances.

Dielectric coupling in weak plasmas [

103]: gradual energy exchange via interaction with the medium’s complex dielectric function, especially in regimes where permittivity varies with frequency and density.

These interactions are rare and subtle at local scales but become cosmologically significant when integrated across billions of light-years of structured cosmic media.

Importantly, all of the candidate mechanisms above are grounded in established quantum electrodynamics and plasma physics. C-PET does not posit any new physics; instead, it applies well-known energy transfer processes, such as inverse bremsstrahlung [

29,

30,

103], dielectric coupling [

30,

103], and coherent forward plasma interactions [

27,

28,

39], in a novel regime: large-scale photon propagation through filamentary and inhomogeneous cosmic media [

10,

21,

22,

156,

157]. Under such conditions, even extremely low-probability interactions can accumulate into measurable redshift while preserving the photon’s coherence, directionality, and spectral identity [

103]. This reinterpretation remains physically conservative while offering an observationally grounded alternative to metric expansion [

42,

43].

4.3. Cumulative Energy Transfer in Sparse Media

The rate and character of photon energy transfer depend on the specific properties of the medium traversed. Each class of intergalactic or interstellar structure, plasma [

4], dust [

90], ionized gas [

21,

22], circumgalactic material [

31,

32], and filamentary networks [

10], exhibits distinct densities, compositions, and interaction cross-sections [

52]. Although individually weak, these effects accumulate over cosmological distances to produce measurable redshift.

Recent observations of fast radio bursts (FRBs) [

31,

32,

89,

148,

149] provide empirical support for the C-PET mechanism. As FRBs traverse the intergalactic medium, they exhibit measurable dispersion caused by cumulative interactions with free electrons [

148], demonstrating that even extremely low-density plasma, including that found in cosmic voids, can significantly affect photon propagation [

149]. These results help resolve the "missing baryon" problem [

21,

22,

23,

146] and support the view that voids contribute meaningfully to cumulative redshift through non-scattering energy transfer.

The

Segmented Medium Model (SMM) formalizes this accumulation process by simulating photon traversal through alternating regions of varying medium properties. Each segment is characterized by a specific energy transfer coefficient (α-value), reflecting the medium's density and composition. When combined across a light path, these segments yield total redshift curves that can be directly compared to observational datasets such as JADES [

1,

2,

3], Pantheon+ [

9,

38,

126,

127], and deep quasar surveys [

5,

6].

SMM enables flexible modeling of realistic cosmic conditions, such as clustered filaments [

10], voids [

133], and halo regions [

85,

86], and highlights the importance of segment order and density contrast in shaping cumulative redshift. This structure-specific approach allows C-PET to remain consistent with known physics while offering an alternative explanation for cosmological redshift.

4.4. Empirical Support: Voyager, Pantheon+, and Redshift Modeling

Support for the C-PET mechanism emerges from both theoretical consistency and empirical observations. Data from Voyager 1 and 2 [

4,

34,

35,

36] confirmed the presence of low-density plasma beyond the heliopause, affirming that even deep space contains material capable of mediating photon energy transfer across vast distances. Similarly, the Pantheon+ dataset of Type Ia supernovae [

9,

38,

126,

127] exhibits redshift–luminosity patterns that can be reproduced through cumulative energy loss models without invoking metric expansion.

Simulations using the Segmented Medium Model (SMM) demonstrate that small per-light-year energy transfer coefficients (e.g., α ≈ 10⁻⁸ ly⁻¹) can generate redshift values consistent with those observed in high-z galaxy surveys [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18], including JADES and deep-field quasar catalogs [

5,

6]. These models apply realistic medium segmentations based on known cosmic structures [

10,

21,

22], such as filaments, ionized gas regions, and circumgalactic halos [

31,

32], to reproduce redshift-distance trends without assuming an expanding universe.

By aligning with both spacecraft data [

4,

34,

35,

36] and large-scale astronomical surveys [

1,

2,

3,

5,

6,

38], C-PET offers a physically grounded, falsifiable explanation for redshift that avoids speculative constructs and remains consistent with known photon–medium interaction principles [

7,

103].

4.5. Conservation of Energy and Physical Law

Unlike expansion-based models [

42,

43,

44], such as ΛCDM [

91], where the energy lost by redshifted photons has no identifiable recipient and global energy conservation is undefined within general relativity [

45,

46,

47,

93], C-PET proposes a physically grounded mechanism for redshift that preserves conservation principles [

7,

48]. In the C-PET model, photon energy is not lost into nothingness but is instead cumulatively transferred to the surrounding cosmic medium [

21,

22,

24,

25]. This medium, composed of plasma [

4], gas [

21,

22], filaments [

10], dust [

90], and circumgalactic structures [

31,

32], absorbs the transferred energy and can re-radiate it in the form of thermal emissions over time [

96,

97,

98].

This interpretation aligns with known physical laws [

7,

8], including quantum electrodynamics [

7,

24], thermodynamics [

48,

96,

97,

98], and the principle of local energy conservation. While general relativity allows for energy non-conservation in a dynamically expanding spacetime [

45,

46,

47,

77], C-PET eliminates the need for this concession by grounding redshift in a localized, cumulative energy exchange process. The result is a cosmological model that remains consistent with energy conservation across all scales [

48], without invoking speculative constructs such as dark energy [

78,

79] or inflation [

13,

14,

15,

110]. Instead, C-PET relies on known or discoverable physical processes [

7,

8,

11] that can be modeled, tested, and observed within both laboratory and astrophysical contexts [

1,

2,

3,

4].

4.6. Surface Brightness Dimming Without Expansion

The Tolman surface brightness test [

49] predicts that in an expanding universe, surface brightness should diminish with redshift according to a (1+z) [

4] relation. Observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) [

1,

2,

3,

50] appear to confirm this dimming pattern, which is often cited as evidence for space expansion [

42,

43,

44]. However, the C-PET model offers an alternative explanation grounded in photon–medium interactions.

According to C-PET, light undergoes cumulative energy transfer as it traverses vast distances through intergalactic media, leading to apparent dimming without requiring spatial expansion. Additionally, minor refractive delays caused by passage through denser media regions may extend light travel time, subtly influencing inferred distances and observed flux.

Together, these mechanisms, cumulative energy loss [

103,

135] and refractive delay [

103], can reproduce a dimming profile similar to that expected under expansion-based models [

42,

43,

44], including the (1+z) [

4] trend [

49]. Unlike traditional tired light theories [

116], C-PET preserves image clarity and spectral coherence [

103], avoiding the blurring and line broadening that previously discredited non-expansion models. In doing so, it provides a falsifiable and physically plausible mechanism for surface brightness dimming that does not depend on metric expansion [

42,

43,

44].

4.7. Laboratory and Observational Support for Photon Energy Transfer

A central premise of the C-PET model is that cosmological redshift arises not from the expansion of space [

42,

43,

44] but from cumulative photon energy transfer to cosmic media over vast distances. This concept, while divergent from the standard ΛCDM interpretation [

91], is grounded in known physical processes [

7,

24,

25] and supported by both laboratory phenomena and astrophysical observations.

4.7.1. Laboratory-Scale Phenomena

Several established physical processes demonstrate that photons can transfer energy to matter [

103], even in the absence of scattering or absorption:

Compton Scattering: High-energy photons interacting with free electrons experience energy loss in proportion to their wavelength [

103]. While typically observed with X-rays and gamma rays, the underlying principle of photon–electron energy exchange is universal [

7,

51]. Laboratory studies of plasma confinement in tokamaks [

40] and other controlled environments confirm that photons can transfer energy to matter [

103] even in low-density regimes. C-PET extrapolates this effect to lower-energy photons undergoing infrequent interactions over cosmological distances.

Rayleigh and Raman Scattering: In condensed media, photons experience elastic and inelastic scattering [

103], shifting their energy and wavelength. Though such interactions are less prominent in low-density media, they establish that photon–matter interactions inherently modify photon energy.

Optical Attenuation in Gases: The Beer-Lambert law describes photon attenuation in various media including gases [

135]. Laboratory studies confirm that photons passing through rarefied gases may experience minor energy loss [

103,

135], often without broad scattering effects. While negligible over short paths, these effects can accumulate across billions of light-years. These examples show that photon–medium energy transfer is a real and measurable phenomenon in controlled settings, providing a plausible basis for its cosmological-scale application in C-PET.

4.7.2. Observational Evidence from Space

Empirical data from space-based missions and high-resolution spectroscopy support the presence of pervasive media capable of mediating photon energy transfer:

Voyager Plasma Detections: Measurements from Voyager 1 and 2 [

4,

34,

35,

36] beyond the heliopause revealed low-density plasma (~0.003 cm⁻³), confirming that even deep interstellar space contains material suitable for photon interaction.

X-ray and Ultraviolet Absorption Features: Observations of distant quasars and gamma-ray bursts [

102,

103] show consistent soft X-ray and UV absorption, indicating interactions with diffuse intergalactic media [

21,

22], particularly hydrogen and trace metals [

52].

Supernova Color Shifts and Dimming: Certain Type Ia supernovae9, [

38,

87,

88] appear dimmer or redder than predicted by dust extinction models alone. These anomalies may reflect cumulative photon energy loss [

24,

25] or wavelength shift via interactions with plasma or dust [

90].

Cosmic Infrared Background (CIB): The diffuse infrared glow [

54] often attributed to redshifted starlight and dust emission supports the idea that photon energy is absorbed and re-emitted over time. This fundamental thermodynamic process [

96,

97,

98] is consistent with C-PET's cumulative thermalization mechanism.

Collectively, these observations offer indirect yet compelling support for the hypothesis that photons interact with the intergalactic medium [

21,

22,

31,

32] across cosmological distances, resulting in measurable energy loss and spectral redshifting.

4.7.3. Summary: Compatibility with Known Physics

The C-PET model remains grounded in well-established physics, extending familiar photon–matter interactions to the cosmological regime:

By aligning with known physical processes , C-PET offers a falsifiable and empirically anchored alternative to redshift mechanisms based on spatial expansion [

42,

43,

44].

To build on this foundation,

Appendix E proposes a structured framework for quantitatively evaluating whether the cumulative energy transferred through C-PET can account for the observed spectral shape, isotropy, and energy density of the microwave background field [

94,

104,

105]. Rather than offering conclusive proof, the appendix defines a roadmap for future interdisciplinary modeling and invites collaboration to rigorously test whether the Photon–Medium Microwave Thermal Field (PMMTF) can emerge from known physical processes.

4.7.4. Historical Context and Modern Extensions

The concept of photon energy loss during cosmic transit has historical precedent in early tired light theories [

144,

145]. While classical tired light models [

136,

142,

143] were largely abandoned due to their inability to preserve spectral coherence and explain time dilation, the C-PET mechanism addresses these limitations through its non-scattering formulation. Modern investigations into photon decay in curved spacetime [

145] and alternative redshift mechanisms [

143] provide theoretical foundations that inform the development of energy transfer models like C-PET.

5.0. Observational Evidence Supporting the Physical Universe Theory (PUT)

The Physical Universe Theory (PUT) asserts that the universe is infinite in both space and time, governed by persistent physical laws that apply uniformly across all epochs and locations. Rather than emerging from a singular origin or evolving through speculative mechanisms like inflation [

13,

14,

15,

110], PUT maintains that structure, order, and coherence arise naturally within an eternal cosmos governed by the laws of physics.

While this view contrasts sharply with the ΛCDM model [

42,

43,

44,

91], which links high redshift to cosmic youth and explains large-scale structure through rapid early expansion [

13,

14,

15], empirical observations increasingly support the foundations of PUT. This section outlines three major categories of supporting evidence:

Mature High-Redshift Galaxies: Observations from JWST [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18,

50] and other instruments have revealed galaxies at extreme redshifts (e.g.,

z > 10) with high stellar masses, enriched chemical signatures, and disk-like morphologies [

73,

74]. These features defy ΛCDM expectations of early-universe immaturity [

58,

59,

60], but align naturally with PUT's assertion that redshift reflects photon journey and interaction history, not galaxy age.

Cosmic Megastructures: Massive, coherent structures such as the Big Ring and Giant Arc [

20] span billions of light-years, well beyond the statistical limits imposed by standard cosmological assumptions [

42,

43,

44]. Under PUT, such formations are expected outcomes of an unbounded, eternal cosmos [

12,

123].

Uniformity of Physical Laws: Across vast distances and lookback times, the same atomic transitions [

52], gravitational behaviors [

45,

46,

47], and thermodynamic principles [

48,

96,

97,

98] appear to govern the behavior of matter and energy. This supports PUT's central claim that physical law is a universal constant, not a function of cosmic age or expansion phase.

Together, these lines of evidence reinforce a cosmology rooted not in expansion or origin, but in continuity, structure, and universal law. The reinterpretation of background radiation, as explored in detail in later sections, further supports the Physical Universe Theory's foundational claim that cosmic phenomena emerge from physical processes, not singular events. Each line of evidence gains further explanatory power when interpreted through the C-PET mechanism, which underpins the PUT framework.

5.1. Reinterpreting Furthest Observed Galaxies (FOGs)

The formation and evolution of galaxies must be reconsidered outside the paradigm of a singular origin event [

13,

14,

15] or a young, expanding universe [

42,

43,

44]. PUT asserts that the cosmos has had infinite time and space to produce diverse galactic structures. Rather than interpreting early galaxy formation as rapid or anomalous [

58,

59,

60,

150], PUT reframes these observations as the natural outcome of ancient, evolved systems located at vast distances. This perspective aligns with observed morphological maturity in the most distant galaxies [

73,

74], such as quiescent ellipticals, ordered spirals, and enriched star populations [

61,

62]. By grounding galaxy evolution in observable physical properties and infinite temporal scales, PUT offers a consistent framework to explain the structural richness of the cosmos without invoking compressed timelines or accelerated formation scenarios [

58,

59,

60].

Under ΛCDM, galaxies like MoM-z14 and JADES-GS-z14-0 [

16,

17,

18], detected at redshifts above 14, are assumed to be only a few hundred million years old, having formed shortly after the Big Bang [

13,

14,

15]. This view demands rapid and extraordinary mechanisms for mass assembly, dust formation, and chemical enrichment [

58,

59,

63,

64,

75,

76]. In contrast, PUT interprets redshift not as a marker of cosmic youth, but as the outcome of cumulative energy transfer as photons traverse interacting media across immense distances. Therefore, these galaxies need not be young, they may be ancient, comparable in age to galaxies near the Milky Way [

61,

62], but located vastly farther away than ΛCDM would predict [

42,

43,

44].

By analyzing galaxy characteristics, such as stellar mass [

73,

74], morphology [

67,

68], metallicity [

55,

56,

65,

66], and quiescence [

62,

69], we find strong similarities between high-z galaxies and mature local analogs. These similarities suggest that many furthest observed galaxies (FOGs) are ancient, not primordial [

58,

59,

60].

The following table compares the structural and chemical properties of several high-redshift galaxies with local analogs, illustrating how the observed maturity of FOGs aligns more naturally with the Infinite Universe Framework than with ΛCDM's early-universe expectations [

42,

43,

44].

Table 5.1.1.

Structural Comparison of Furthest Observed Galaxies and Local Analogs [65,66]

Table 5.1.1.

Structural Comparison of Furthest Observed Galaxies and Local Analogs [65,66]

| Galaxy Name |

Redshift (z) |

ΛCDM Age Estimate |

Structural Features |

Local Analog |

Analog Age Estimate |

| MoM-z14 |

14.44 |

~280 Myr |

High mass, dusty, compact, evolved |

NGC 5253 (starburst) |

~10–12 Gyr |

| JADES-GS-z14-0 |

14.32 |

~290 Myr |

High SFR, disk-like structure |

Haro 11 |

~6–10 Gyr |

| GN-z11 |

10.6 |

~430 Myr |

Starburst, UV bright |

I Zw 18 |

~6–10 Gyr |

| CEERS-93316 |

11.0 |

~400 Myr |

Metal-rich, massive |

M82 |

~10–13 Gyr |

| HD1 |

13.3 |

~320 Myr |

High luminosity, possible AGN |

NGC 7674 |

~8–12 Gyr |

These correlations reinforce the central claim of PUT: that observed redshift is not a reliable proxy for galactic age, and that a galaxy's physical characteristics [

73,

74] offer a more accurate foundation for estimating its age and evolutionary history. By prioritizing structure and composition over inferred youth, PUT enables a more coherent interpretation of deep-field observations [

1,

2,

3] and the cosmological timeline.

5.2. Cosmic Megastructures and the Infinite Cosmos

Cosmic megastructures, including the Big Ring, Giant Arc, Hercules-Corona Borealis Great Wall, and Sloan Great Wall [

20,

130,

131,

134], represent spatial formations that extend over billions of light-years. These structures challenge the fundamental assumptions of ΛCDM [

42,

43,

44,

91], particularly the Cosmological Principle's claim of homogeneity and isotropy at large scales. According to ΛCDM [

42,

43,

44], structure formation is bounded by the age of the universe and the speed at which causal interactions can occur. As such, the presence of coherent structures larger than ~1.2 billion light-years should be statistically implausible.

In contrast, the Physical Universe Theory (PUT) naturally accommodates the existence of such megastructures. Within an infinite, eternal universe, there is no upper limit on the size or duration of cosmic evolution. These formations are interpreted not as anomalies but as expected outcomes of gravitational interaction [

45,

46,

47], matter clustering [

100,

101], and structural evolution over limitless time and space. Rather than violating a uniform cosmological model [

42,

43,

44], they reinforce a universe shaped by persistent physical laws across arbitrarily large scales.

Recent discoveries, such as the Big Ring (spanning ~1.3 billion light-years and composed of gamma-ray bursts) and the Giant Arc (stretching over 3.3 billion light-years) [

20], are not isolated. They join a growing list of immense formations that share alignment patterns and coherent morphologies inconsistent with early-randomized expansion models [

42,

43,

44].

In addition to these somewhat rare anomalies, more commonplace cosmic filaments [

10] further support PUT's interpretation. Spanning tens to hundreds of millions of light-years [

10,

132,

133], these dense, thread-like structures form the backbone of the cosmic web and connect galaxies and clusters across the universe. Their ubiquity, persistence across redshifts, and gravitational influence reflect long-standing structural organization, not emergent patterns from a young or rapidly expanding universe [

42,

43,

44]. Under PUT, such filaments are expected outcomes of an infinite, structure-filled cosmos that evolves through local interactions over limitless time.

The presence of such megastructures adds weight to the Infinite Universe Framework's foundational premise: that large-scale cosmic organization is not a statistical fluke but a natural consequence of unbounded spatial and temporal evolution. These observations bolster PUT's contention that structure arises not from early inflation [

13,

14,

15] or rapid expansion [

42,

43,

44], but from gravitational shaping [

45,

46,

47] within a continuous and eternal cosmos.

5.2.1. Case Study: RUBIES-UDS-QG-z7 – Quiescence Without Paradox

The galaxy RUBIES-UDS-QG-z7 [

73], with a spectroscopically confirmed redshift of z ≈ 7.3, has been classified as quiescent [

62,

69], meaning it has already ceased active star formation. Within the ΛCDM framework [

42,

43,

44,

91], this presents a significant anomaly: at z ≈ 7, the universe is believed to be only ~750 million years old, insufficient time for a galaxy to form, accumulate stellar mass, exhaust its gas supply, and transition into a quiescent state [

58,

59,

62].

Under the PUT+C-PET model, however, this observation becomes entirely expected. Redshift is not interpreted as a measure of cosmic age, but rather as the cumulative result of photon energy transfer during light's long journey through sparse intergalactic media. In this context, RUBIES-UDS-QG-z7 can be both ancient and extremely distant, consistent with its observed characteristics [

73].

Its high stellar mass, evolved stellar population, and lack of ongoing star formation [

62,

69,

71,

72,

73] are all indicative of a mature galaxy [

61,

62]. Rather than requiring implausibly rapid formation and quenching [

58,

59,

60], PUT+C-PET allows for formation epochs that precede any time constraints imposed by a Big Bang cosmology [

13,

14,

15], because the universe itself is not temporally bounded.

This case highlights a core strength of the PUT+C-PET model: it allows astronomers to accept observed galaxy properties at face value, without invoking speculative physics or compressed evolutionary scenarios [

58,

59,

60]. By decoupling redshift from youth, PUT+C-PET offers a coherent, physically grounded explanation for the existence of evolved, quiescent galaxies at high redshift within an infinite, mature cosmos.

5.2.2. Spectroscopic Detection of Heavy Elements at High Redshift

One of the most unexpected findings from JWST [

1,

2,

3,

55,

56] has been the spectroscopic detection of heavy elements, particularly oxygen, in galaxies with redshifts as high as

z > 10. These observations are made possible through infrared spectroscopy of emission lines such as [O III] 500.7 nm [

55,

56], redshifted into JWST's detection range [

50].

Under ΛCDM [

42,

43,

44,

91], such detections are difficult to reconcile. They imply that galaxies must have experienced rapid metal enrichment [

63,

64] within just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang [

13,

14,

15], a timeline that strains conventional models of early star formation and chemical evolution [

58,

59,

63,

64].

In the PUT+C-PET model, however, this phenomenon poses no contradiction. Here, redshift is interpreted not as a measure of cosmic youth, but as a signal of cumulative photon energy transfer over vast distances. A galaxy at

z = 10 or even z = 14 need not be young; it may be ancient and chemically mature [

55,

56], with the light we now observe having been emitted long after its formation.

This reframing eliminates the need for exotic or accelerated enrichment scenarios [

63,

64]. Instead, the presence of oxygen and other metals [

55,

56] is fully consistent with standard nucleosynthesis processes [

92] occurring over long evolutionary timelines in an infinite, unbounded cosmos. Rather than anomalies, such chemically enriched high-redshift galaxies become strong evidence in support of the PUT+C-PET interpretation.

5.3. Physical Law Continuity Across Space and Time

A foundational premise of the Infinite Universe Framework (IUF) is that the laws of physics apply uniformly across all space and time. This is not a philosophical assumption but one grounded in observation [

1,

2,

3,

4]. From nearby galaxies to those beyond

z > 10, we see consistent physical behavior: atomic transitions [

52], stellar evolution [

61,

62], radiative processes [

103], and gravitational dynamics [

45,

46,

47] all function identically.

This remarkable consistency supports the conclusion that physical laws are stable and universal, even across distances of hundreds of billions of light-years. It challenges the idea that exotic, time-limited events, like inflation [

13,

14,

15], dark energy [

78,

79], or a singular beginning [

13,

14,

15], are required to explain cosmological observations.

The Physical Universe Theory (PUT), coupled with the Cumulative Photon Energy Transfer (C-PET) model, is built explicitly on this continuity. Unlike ΛCDM, which relies on speculative constructs to address observational puzzles, PUT+C-PET uses well-tested physics and cumulative interactions across known media [

21,

22] to explain redshift, structure formation, and the cosmic background [

94,

104].

The table below compares how the Physical Universe Theory and C-PET model (PUT+C-PET) align with fundamental physical laws, in contrast to areas where the ΛCDM model departs from or circumvents those principles.

Table 5.3.1.

Alignment of PUT+C-PET with Fundamental Physical Laws.

Table 5.3.1.

Alignment of PUT+C-PET with Fundamental Physical Laws.

| Law or Principle |

PUT+C-PET Adherence |

ΛCDM Conflict |

| Conservation of Energy |

Preserved: redshift arises from cumulative photon energy transfer via medium interactions |

Violated during inflation [13,14,15,110]

and via dark energy [78,79] |

| Thermodynamics |

No beginning; entropy evolves naturally in an infinite cosmos |

Entropy paradox at Big Bang [13,14,15]; inflation lowers entropy |

| Relativity (Special and General) |

No metric expansion; c is never exceeded; causality preserved |

Allows superluminal recession [42,43,44], non-local inflation [13,14,15,110] |

| Causality |

Infinite extent removes horizon problem; causality maintained |

Inflation introduces acausal effects [13,14,15] |

| Empirical Observability |

All mechanisms are observable or falsifiable |

Inflation, singularities, and dark energy are untestable |

| Photon Behavior |

Redshift explained via known photon–medium interactions (non-scattering) |

Redshift tied to space expansion [42,43,44] |

Rather than propose untestable mechanisms, PUT+C-PET explains cosmic phenomena using consistent and observable physics:

No inflation is needed; isotropy emerges statistically in an infinite, structured cosmos. This eliminates the need for inflation by resolving the horizon problem through the universe's infinite size and age, removing ΛCDM's need to postulate a brief, acausal burst of faster-than-light expansion to explain large-scale uniformity.

No dark energy is invoked; apparent acceleration results from distance overestimation due to redshift accumulation and refractive delays.

No Big Bang is assumed; without a singular origin, the model avoids thermodynamic and causal paradoxes.

Cosmological effects in PUT+C-PET arise from:

Known photon behavior [

103], including cumulative energy transfer in plasma and dust [

90] without scattering;

Observed intergalactic media [

21,

22,

31,

32], such as filaments [

10], WHIM [

21,

22], CGM [

31,

32], and the Lyman-alpha forest [

137];

Scalable, cumulative interactions that remain consistent with conservation laws, relativity, and thermodynamics.

In sum, the continuity of physical law is not merely a working assumption of IUF, it is a direct outcome of what we observe across the universe. PUT+C-PET honors these laws throughout, offering a coherent, testable alternative to ΛCDM that remains fully grounded in established physics.

6.0. Modeling Redshift Through Cumulative Photon Energy Transfer (C-PET)

The Cumulative Photon Energy Transfer (C-PET) model reinterprets cosmological redshift not as evidence of space expanding, but as the physical outcome of incremental energy transfer from photons to the intergalactic medium (IGM) over vast distances. This mechanism offers a testable, non-expanding alternative to the standard cosmological framework, grounded in known physical interactions rather than spacetime metric dynamics.

In C-PET, photons lose energy through infrequent, non-scattering interactions that occur repeatedly as they traverse cosmic structures such as plasma, dust, filaments, sheets, voids, and circumgalactic media. These interactions do not alter the photon's direction or coherence, preserving the integrity of high-resolution images and sharp spectral lines observed by JWST and other deep-field surveys [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18]. Redshift thus accumulates cumulatively along the light’s journey, shaped by the type, order, and density of media encountered, rather than being determined by distance alone.

Crucially, the energy transferred from photons is not lost but conserved and redistributed into the surrounding medium, where it can contribute to intergalactic heating and diffuse thermal phenomena.

Section 7 explores this redistribution process in detail, including a reinterpretation of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) as a Photon–Medium Microwave Thermal Field (PMMTF): a pervasive, low-temperature microwave emission arising naturally from the same cumulative energy transfer mechanism.

The remainder of this section builds the quantitative foundation for the C-PET model, beginning with two distinct formulations:

• The Continuous Medium Model (CMM): a baseline model that assumes a uniform energy transfer rate per unit distance;

• The Segmented Medium Model (SMM): a more physically realistic framework simulating photon travel through a heterogeneous cosmic web, using empirically grounded, medium-specific energy transfer coefficients (α-values).

Through this modeling framework, C-PET demonstrates that observed redshift values, including those approaching z ≈ 14, can emerge from cumulative physical interactions alone, without requiring space expansion, inflation, or dark energy.

6.1. Foundational Assumptions of the C-PET Redshift Mechanism

To accurately evaluate the predictive behavior of the C-PET model, redshift must be modeled within the full physical context of photon–medium interactions. The following assumptions form the foundation of C-PET’s redshift mechanism:

Segmented Medium Structure (SMM Required)

Space is not homogeneous but composed of alternating regions, cosmic voids, filaments, sheets, circumgalactic media (CGM), and halos, characterized by distinct densities, temperatures, and interaction properties [

10,

20,

85,

86].

Medium-Specific Energy Transfer Coefficients (α₁, α₂, … αₙ)

Each segment type has a characteristic energy transfer coefficient, α, that quantifies the rate at which it attenuates photon energy per unit length. These coefficients are empirically grounded, derived from observational data on baryon density [

21,

22], thermal properties, and structure formation [

85,

86].

Compound Redshift Accumulation

Redshift is not linear but accumulates exponentially across the sequence of segments

2:

- 7.

Non-Scattering, Forward-Only Transfer

- 8.

Photons interact with the medium in a way that reduces energy without deflecting trajectory. This preserves both spectral sharpness and image resolution [

103], even at high redshift, consistent with observations from JWST and HST [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18].

- 9.

Redshift Reflects Path Length, Not Comoving Distance

- 10.

A high redshift (e.g.,

z = 14) may correspond to a true path length of hundreds of billions of light-years, far exceeding ΛCDM estimates [

42,

43,

44]. Redshift thus reflects the cumulative physical interaction history of the photon, not the metric evolution of space.

- 11.

Brightness Dimming Scales as (1+z)², not (1+z)⁴

- 12.

Because C-PET does not assume expanding space, it omits the angular-area stretching component of Tolman dimming [

49]. Observed surface brightness dimming arises solely from photon energy reduction and relativistic time dilation, leading to a dimming relation proportional to (1+

z)².

6.2. Modeling Approaches: Continuous vs. Segmented Media

To simulate redshift via Cumulative Photon Energy Transfer (C-PET), we must account for the structured nature of the intergalactic medium. Space is not homogeneous; it consists of large-scale features,

Cosmic Voids, Walls / Sheets, Filaments, WHIM (Diffuse Overlapping Phase), and

Dense Media (including CGM, ISM, and Halos) [

10,

20,

21,

22,

85,

86]. C-PET incorporates this structure through two complementary modeling approaches: the

Continuous Medium Model (CMM) and the

Segmented Medium Model (SMM).

6.2.1. Continuous Medium Model (CMM)

The Continuous Medium Model treats space as uniformly filled with a low-density medium. This simplification is useful for illustrating the general redshift mechanism or estimating redshift accumulation in average conditions.

Redshift in the CMM accumulates exponentially with distance

3:

z is the total redshift,

α is the average energy transfer coefficient (per light-year),

D is the photon path length in light-years.

CMM illustrates how even an extremely sparse medium with α on the order of 10

− [

12] to 10

− [

13] ly

− [

1], can cumulatively produce significant redshift over cosmological distances, without requiring space expansion.

6.2.2. Segmented Medium Model (SMM)

The Segmented Medium Model offers a more physically realistic alternative. Instead of assuming a uniform medium, it divides space into discrete segments, each representing one of the five canonical medium types: Cosmic Voids, Walls / Sheets, Filaments, WHIM (Diffuse Overlapping Phase), and Dense Media (CGM, ISM, Halos)

Each segment is assigned a distinct energy transfer coefficient α

i , based on its density, temperature, and composition. As a photon traverses these segments, redshift accumulates as a compounded exponential

4:

The SMM allows redshift to reflect not just how far a photon has traveled, but what it has passed through and in what order. SMM is especially powerful for:

Modeling redshift anisotropies due to large-scale structure,

Simulating visibility limits of high-redshift galaxies,

Analyzing the cumulative formation of the cosmic microwave background as a distributed energy transfer process,

Aligning C-PET simulations with known cosmic web structures [

10,

20,

21,

22,

85,

86,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134].

6.2.3. Summary of Modeling Approaches

The following table summarizes the distinct roles of the Continuous Medium Model (CMM) and the Segmented Medium Model (SMM) within the C-PET model.

Table 6.2.3.1.

Summary of Redshift Modeling Approaches in C-PET

Table 6.2.3.1.

Summary of Redshift Modeling Approaches in C-PET

| Model |

Description |

Best For |

| CMM |

Uniform medium, constant α |

Illustrative modeling; concept validation |

| SMM |

Structured medium with segment-specific αi

|

Realistic redshift modeling; structure alignment; simulation of anisotropies |

6.2.4. Empirical Foundations of Energy Transfer Coefficients (α)

A key strength of the Segmented Medium Model (SMM) within the C-PET model is its reliance on physically plausible and empirically grounded energy transfer coefficients. Rather than treating the coefficient α as a free parameter, C-PET constrains its values based on known properties of cosmic media and theoretical interaction rates.

Each α-value represents the rate of photon energy attenuation per unit distance within a specific medium type. These coefficients are not arbitrary; they are estimated from observed densities, reasonable interaction cross-sections, and known energy exchange mechanisms between photons and the medium.

A general bounding formulation for α is

5:

ne : number density of free electrons in the medium [cm

− [

3]]

σ: effective photon–medium interaction cross-section [cm [

2]]

ΔE/E: fractional energy loss per interaction (typically on the order of 10

− [

12]

This formulation is consistent with weak, cumulative energy transfer mechanisms such as inverse bremsstrahlung, dielectric coupling, and other non-scattering plasma interactions described in

Section 4.2. The assumed cross-section (σ∼10

− [

24] cm [

2]) is a conservative, order-of-magnitude estimate, comparable to the Thomson cross-section and suitable for modeling low-frequency photon interactions in sparse plasmas.

Even with such low coupling strength, cumulative energy transfer over large distances can produce measurable redshifts. For example, intergalactic voids with

ne∼10

− [

8] cm

− [

3] yield α∼5×10

− [

13] ly

− [

1], consistent with the lowest empirically used values in C-PET. Conversely, dense circumgalactic environments with

ne∼10

− [

4] −10

− [

2] cm

− [

3] yield α∼10

− [

10]−10

− [

9] ly

− [

1], aligned with redshift segment modeling near galaxies and halos.

These α-values are thus physically bounded by real-world conditions and supported by both theoretical and observational estimates of electron density and photon interaction strength. They enable a realistic simulation of redshift accumulation without invoking expansion, inflation, or exotic forces.

These physically constrained coefficients form the basis of the segment parameters used in stochastic simulations (

Section 6.3) and are summarized in Appendix C.2.

6.3. Building a Segment-Based Simulation of Redshift Accumulation

To evaluate whether cumulative photon energy transfer can account for observed redshift values (e.g., z ≈ 14.4) [

16,

17,

18] without invoking metric expansion, the C-PET model simulates photon paths across a randomized cosmic landscape composed of distinct media segments. This section outlines the input parameters and logic used in that stochastic modeling.

6.3.1. Rationale for Segmentation

Unlike models that treat space as smooth or homogeneous, the Segmented Medium Model (SMM) acknowledges that the universe is composed of interwoven cosmic media that vary in density, temperature, and interaction potential [

10,

20,

85,

86].

The segmentation approach allows the model to:

This segmental approach forms the basis for realistic stochastic simulations of redshift accumulation, implemented in

Section 6.4.

6.3.2. Segment Allocation and Parameter Summary

To simulate redshift under C-PET, photons are modeled as traveling through a randomized sequence of segment types. Each segment represents a physically distinct region of the intergalactic medium [

21,

22], with a volume-weighted probability of occurrence and a corresponding energy transfer coefficient (α). These coefficients determine how much redshift is accumulated over a given segment length.

The table below summarizes the five segment types used in the stochastic implementation, along with their approximate volume fractions [

152,

155], α-values, and typical path lengths:

Table 6.3.2.1.

Segment types, volume fractions, α-values, and typical lengths used in C-PET stochastic simulations

Table 6.3.2.1.

Segment types, volume fractions, α-values, and typical lengths used in C-PET stochastic simulations

| Segment Type |

Volume Fraction |

α (ly⁻¹) |

Typical Length (MLY) |

Cosmic Voids

[10,132,133,152,153,155] |

~76% |

5 × 10⁻¹³ |

30 – 100 |

Walls / Sheets

[10,152,155] |

~18% |

8 × 10⁻¹¹ |

5 – 30 |

| Filaments [10,41,152,155] |

~6% |

4 × 10⁻¹⁰ |

10 – 50 |

WHIM [1,22,31,89,147,155]

(Diffuse Overlapping Phase) |

~3%* |

2 × 10⁻¹⁰ |

5 – 20 |

| Dense Media (CGM, ISM, Halos) [21,22,90,102,103,156,157] |

<1% |

2 × 10⁻⁹ |

0.1 – 5.0 |

The α-values used in the stochastic simulations are empirically derived from observed intergalactic and circumgalactic conditions. Table C.2 summarizes these coefficients alongside representative densities, temperatures, and volume fractions for each segment type. These values are not adjustable parameters but physically grounded inputs, ensuring that C-PET redshift modeling remains constrained by measurable cosmic environments.

6.3.3. Segment Order and the Nonlinear Nature of Redshift Accumulation

While the Segmented Medium Model (SMM) defines redshift as a cumulative process shaped by the types of media encountered, it is equally important to consider the

order in which those segments appear. Because redshift compounds exponentially, denser regions encountered

later in the photon's journey contribute

more redshift than if they had occurred earlier. This gives the C-PET model a distinctive

path-dependence absent in models that treat redshift as a linear function of distance [

42,

43,

44].

To illustrate: consider two photon paths of equal total length. One traverses mostly through voids before ending in denser structures; the other alternates between voids and high-density regions. Though the path lengths are the same, the second scenario will produce a greater redshift, because the high-α segments apply their energy transfer effect to already redshifted photons, magnifying the cumulative result.

This nonlinear sensitivity to segment composition and sequence is a defining feature of SMM, and it allows C-PET to model subtle anisotropies, unexpected visibility thresholds, and variations in redshift–distance profiles with greater fidelity.

6.3.4. Empirical Support for Segment Composition and α-Values

The α-values used in the stochastic SMM implementation are not free parameters, they are constrained by observed baryon densities [

21,

22], thermal structures, and interaction cross-sections grounded in known physics [

103]:

Cosmic filaments: Observations from the

Lyman-alpha forest [

137] and

Sunyaev–Zel'dovich effect [

138] suggest electron densities in the range of 10

− [

6] to 10

− [

5] cm⁻³. When paired with conservative interaction cross-sections (~10

− [

24] cm²), these densities yield α-values in the range of 10

− [

10] to 10

− [

13] ly⁻¹, directly matching those used for filaments, WHIM, and voids in Appendix C.2.

Voyager plasma data: In the denser environment of the local interstellar medium, Voyager detected plasma densities [

4,

34,

35,

36] consistent with α ≈ 10

− [

8] ly⁻¹. This provides a natural

upper bound on plausible values for dense galactic media in C-PET and further constrains the parameter space.

The Lyman-Alpha Forest as an Observational Blueprint

The

Lyman-alpha forest [

137]

, a dense series of absorption lines in quasar spectra, offers a unique observational testbed for the SMM. Each absorption feature corresponds to a redshifted cloud of intergalactic hydrogen, effectively mapping discrete segments of varying density along the photon's path. These features:

Confirm the presence of a patchwork cosmic medium,

Show clear evidence of localized energy attenuation, and

Retain spectral sharpness, consistent with C-PET’s assumption of non-scattering, direction-preserving photon–medium interactions.

6.3.5. Revising Void Assumptions: Voyager Data and the Persistence of Plasma

The C-PET model depends on whether even the sparsest regions of space can cumulatively redshift photons over vast distances. Voyager 1 and 2 [

4,

34,

35,

36] provide rare in situ evidence that space beyond the heliopause is not empty. Instead, both probes detected unexpectedly persistent plasma densities, typically ~0.001–0.005 particles/cm³, with spikes up to 0.05–0.2 particles/cm³ during CME events, and Voyager 2 recording ~0.039 particles/cm³ in 2019 [

34,

35,

36].

These findings [

4,

34,

35,

36] revise prior assumptions about the interstellar and intergalactic medium, showing that even “empty” regions contain sufficient particles to induce photon energy transfer. If densities comparable to Voyager's findings extended uniformly across intergalactic distances, Voyager-level plasma could produce z ≈ 14 in just ~14 BLY. Scaled-down densities (1/10th to 1/1000th Voyager values) yield z ≈ 14 over distances of 100–350 BLY. This range is consistent with the redshift accumulation explored in the stochastic C-PET simulations described in

Section 6.4.

Importantly, C-PET treats voids not as redshift-neutral expanses, but as low-density contributors to photon energy transfer. Supported by Voyager [

4,

34,

35,

36], quasar absorption data [

137], FRB dispersion measures [

31,

32,

148,

149], and IGM simulations [

85,

86], this view restores redshift continuity across space, even in the absence of luminous structure.

These observations affirm that:

Redshift in C-PET is path-integrated and medium-sensitive.

Even the sparsest regions contribute incrementally to z accumulation.

The redshift–distance relationship scales physically, without invoking cosmic expansion.

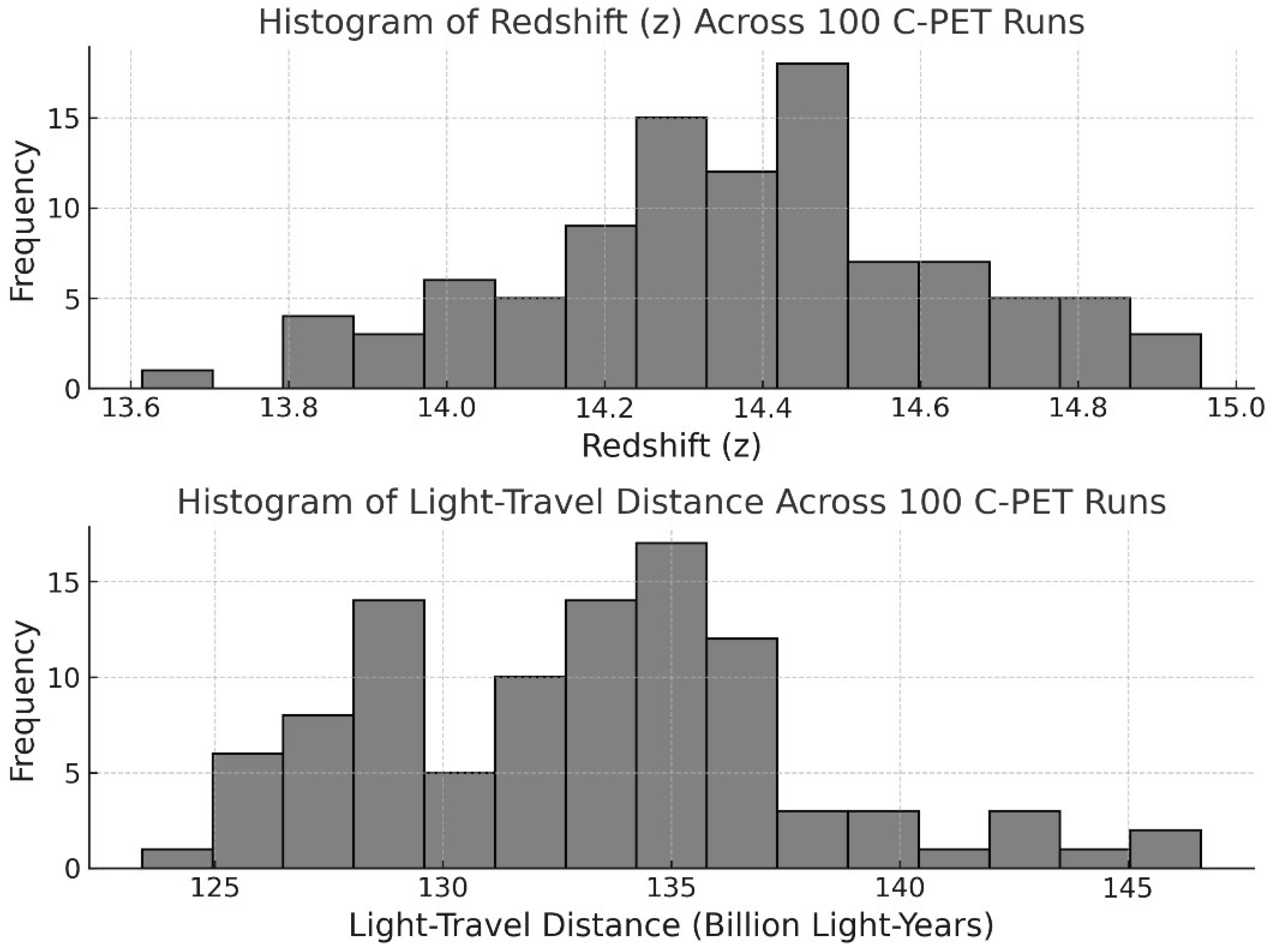

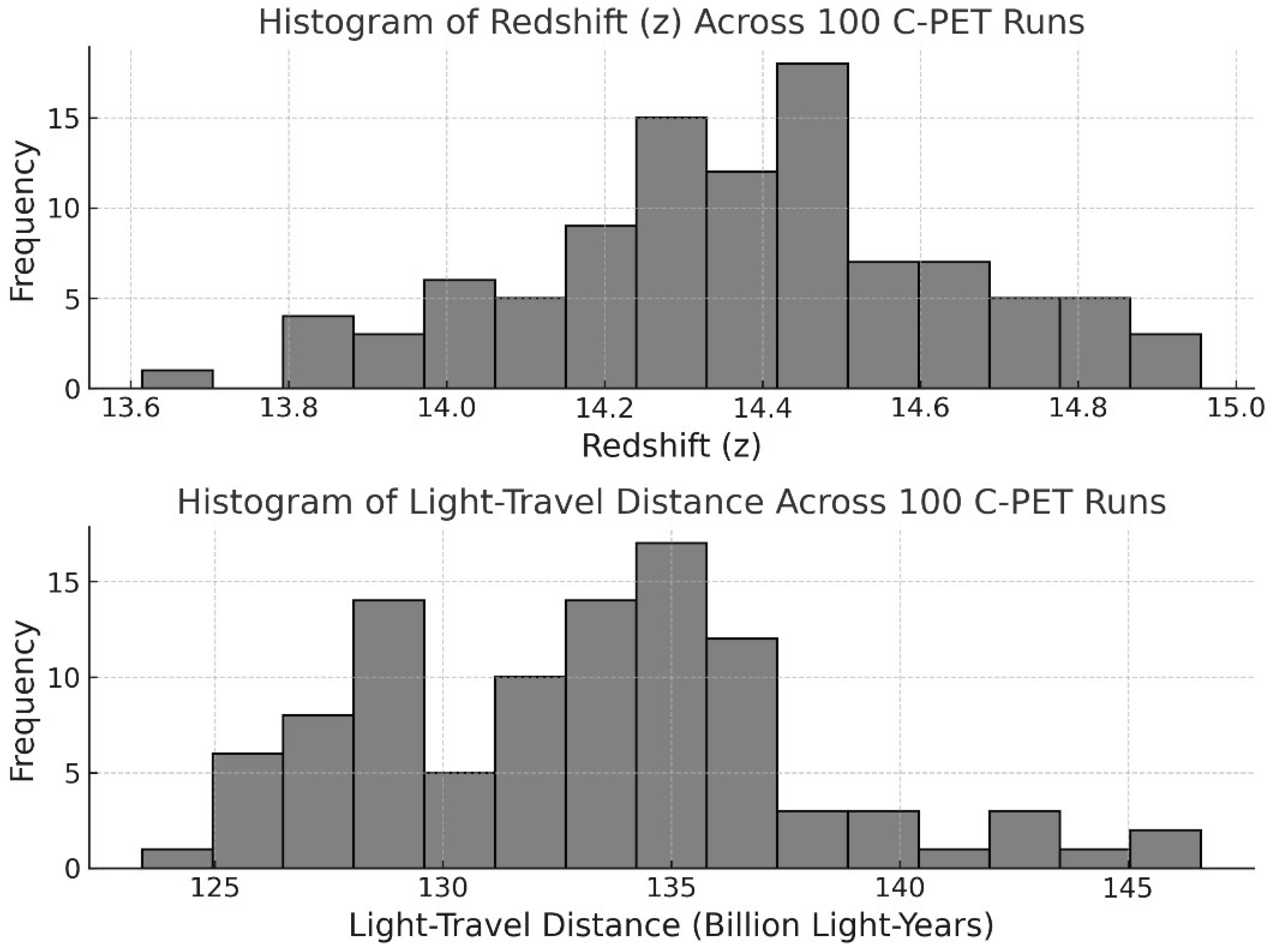

6.4. Stochastic Model Results

To test whether cumulative photon energy transfer through a structured cosmic medium can reproduce the full range of observed redshift values, including those approaching

z ≈ 14.4 [

16,

17,

18], we implemented a stochastic simulation based on the segment framework detailed in

Section 6.3. Each run traces a randomized photon path through a physically heterogeneous universe, where segments represent distinct intergalactic environments such as voids, filaments, walls, and circumgalactic media.

The energy transfer coefficient (α) assigned to each segment is not a free parameter, but derived from observationally constrained properties: electron densities inferred from Lyman-alpha absorption features [

137] and Voyager plasma measurements [

4,

34,

35,

36]; interaction cross-sections consistent with known mechanisms like inverse bremsstrahlung [

29,

30] and dielectric coupling [

103]; and volumetric prevalence estimates drawn from cosmological simulations [

85,

86] and baryon surveys [

21,

22]. This framework enables a realistic simulation of redshift accumulation as photons traverse complex cosmic terrain, losing energy incrementally but without scattering, preserving spectral coherence [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18].

Across 100 randomized simulations, the average light-travel distance required to reach z = 14.4 was approximately: D ≈ 133 billion light-years.

This result closely matches the trajectory predicted by a Voyager/500 exponential attenuation model and underscores the physical plausibility of the C-PET Segmented Medium Model.

C-PET is designed not to yield a single fixed result, but to serve as a dynamic, testable framework, one that can be refined iteratively as new observational constraints emerge. It models redshift accumulation across diverse cosmic conditions in a manner designed for observational testing and continuous improvement.

The next subsection presents this comparison visually and quantitatively, contrasting the C-PET curve with ΛCDM and four Voyager-based benchmarks.

6.4.1. Redshift–Distance Comparison Across Models

A central test of any cosmological model is how it relates observed redshift (

z) to the light-travel distance (

D) of celestial objects. This subsection compares six distinct redshift–distance trajectories: the ΛCDM expansion curve [

42,

43,

44], four Voyager-based exponential attenuation models (α/50 through α/1000) [

4,

34,

35,

36], and the finalized C-PET Segmented Medium Model (SMM) derived from 100 stochastic simulations.

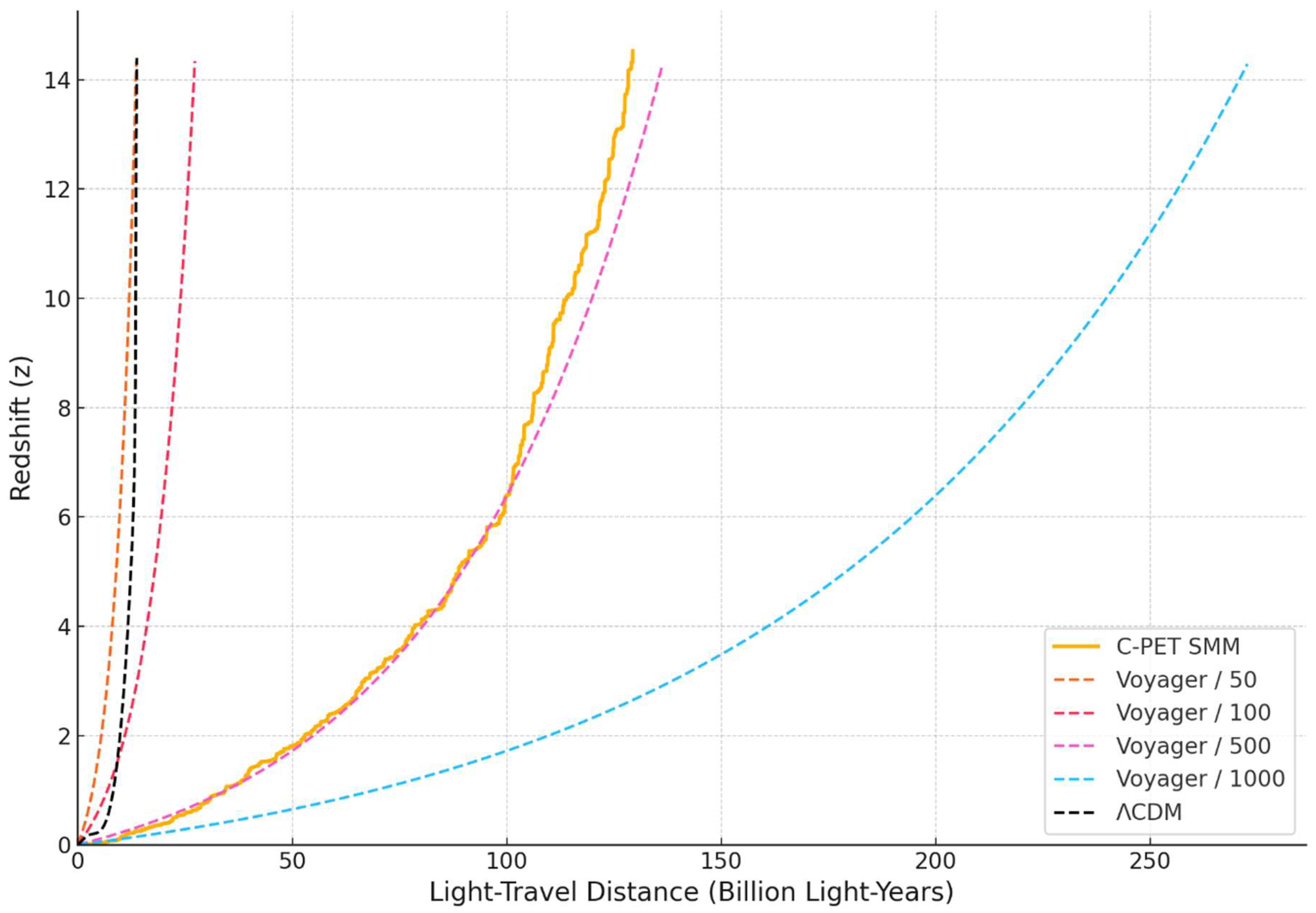

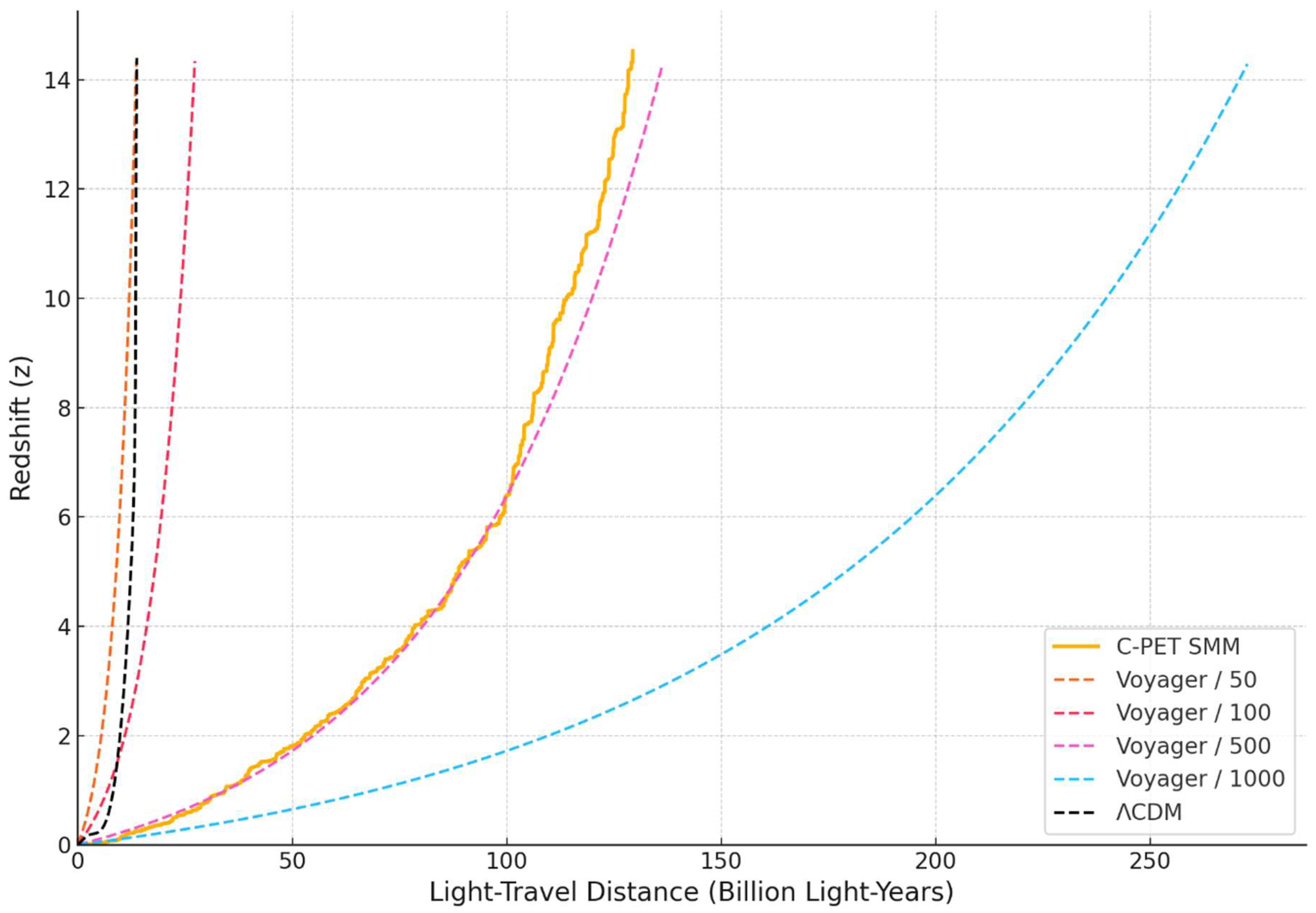

Figure 6.4.1.1 visualizes these relationships, illustrating how C-PET, grounded in physically plausible photon–medium interactions, can reproduce redshift across cosmic scales without invoking expansion. The close alignment between the C-PET SMM curve and the Voyager/500 benchmark [

4,

34,

35,

36] lends empirical weight to the simulation results.

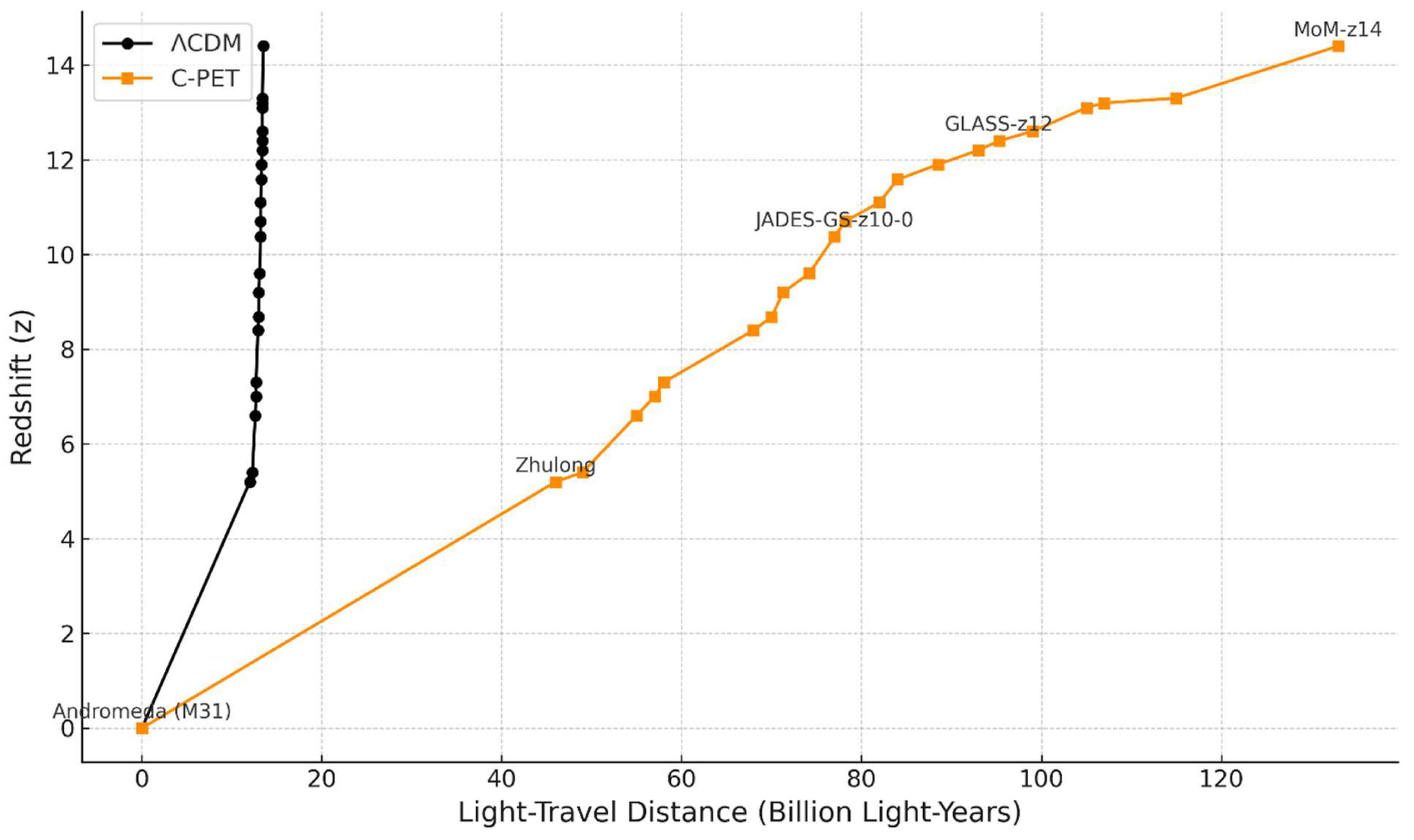

Figure 6.4.1.1: Redshift vs. Distance Comparison

Note: This figure presents the redshift–distance relationships across six models: ΛCDM (black dashed) [

42,

43,

44], four Voyager-scaled exponential attenuation scenarios (α/50, α/100, α/500, α/1000) [

4,

34,

35,

36], and the finalized stochastic C-PET SMM curve (orange). The C-PET SMM curve is derived from 100 randomized intergalactic segment chains using empirical densities and structure [

10,

20,

21,

22,

85,

86]. The Voyager/500 curve closely parallels the C-PET SMM trajectory. ΛCDM saturates below z ≈ 14 at ~13.8 BLY, while C-PET SMM reaches the same redshift at ~133 BLY.

Interpretation:

The Voyager/50 line's proximity to ΛCDM suggests that even moderate-density photon energy loss models can replicate expansion-based redshifts [

4,

34,

35,

36].

The new C-PET SMM model, with heterogeneous structure and realistic attenuation coefficients, demonstrates that redshift need not imply expansion.

Voyager/500 closely tracks the canonical C-PET SMM line, providing an important point of convergence and empirical plausibility.

Voyager/1000 represents the most conservative energy loss model and still reaches z>14 by D=270 BLY, providing a lower-bound constraint.

In the ΛCDM framework [

42,

43,

44], redshift results from the metric expansion of space, producing a curve that rises steeply at low redshift but then plateaus near D ≈ 13.8 billion light-years. This asymptotic behavior reflects ΛCDM's commitment to a finite-age universe and an initial singularity, limiting the interpretive range of deep-field observations.

C-PET, by contrast, introduces a physically grounded, structurally consistent alternative. Redshift is modeled not as a stretching of space but as the cumulative result of energy transfer from photons to intergalactic media, plasma, dust, filaments [

10,

20], voids, via well-established physical mechanisms [

7,

8]. The Segmented Medium Model (SMM) version of C-PET implements this concept by simulating stochastic light paths through empirically validated cosmic structures [

85,

86,

130,

131,

132], each assigned realistic attenuation values and volumetric prevalence.

The result is not just a theoretical possibility but a demonstrably plausible model. This section shows that the C-PET SMM produces a smooth, extended redshift–distance curve that reaches z = 14.4 at

D ≈ 133 billion light-years, fully consistent with known intergalactic densities [

21,

22,

151] and Voyager-derived attenuation benchmarks [

4,

34,

35,

36]. Indeed, the Voyager/500 model tracks closely with the SMM output, providing an empirical anchor for the simulated scenario.

In contrast, ΛCDM's redshift curve flattens not due to observed optical limits or physical obstructions, but as a consequence of its assumed temporal boundary [

42,

43,

44], a feature that becomes increasingly strained in the face of mature high-z galaxies [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18] and large-scale structures [

85,

86]. The C-PET model avoids such constraints, offering a linear and open-ended mapping between

z and

D, as one would expect in a universe governed by continuous physical processes rather than imposed age limits.

This comparative modeling underscores the physical plausibility of C-PET and its potential to reframe our understanding of cosmic redshift as a traversed-distance effect, not a vestige of expansion.

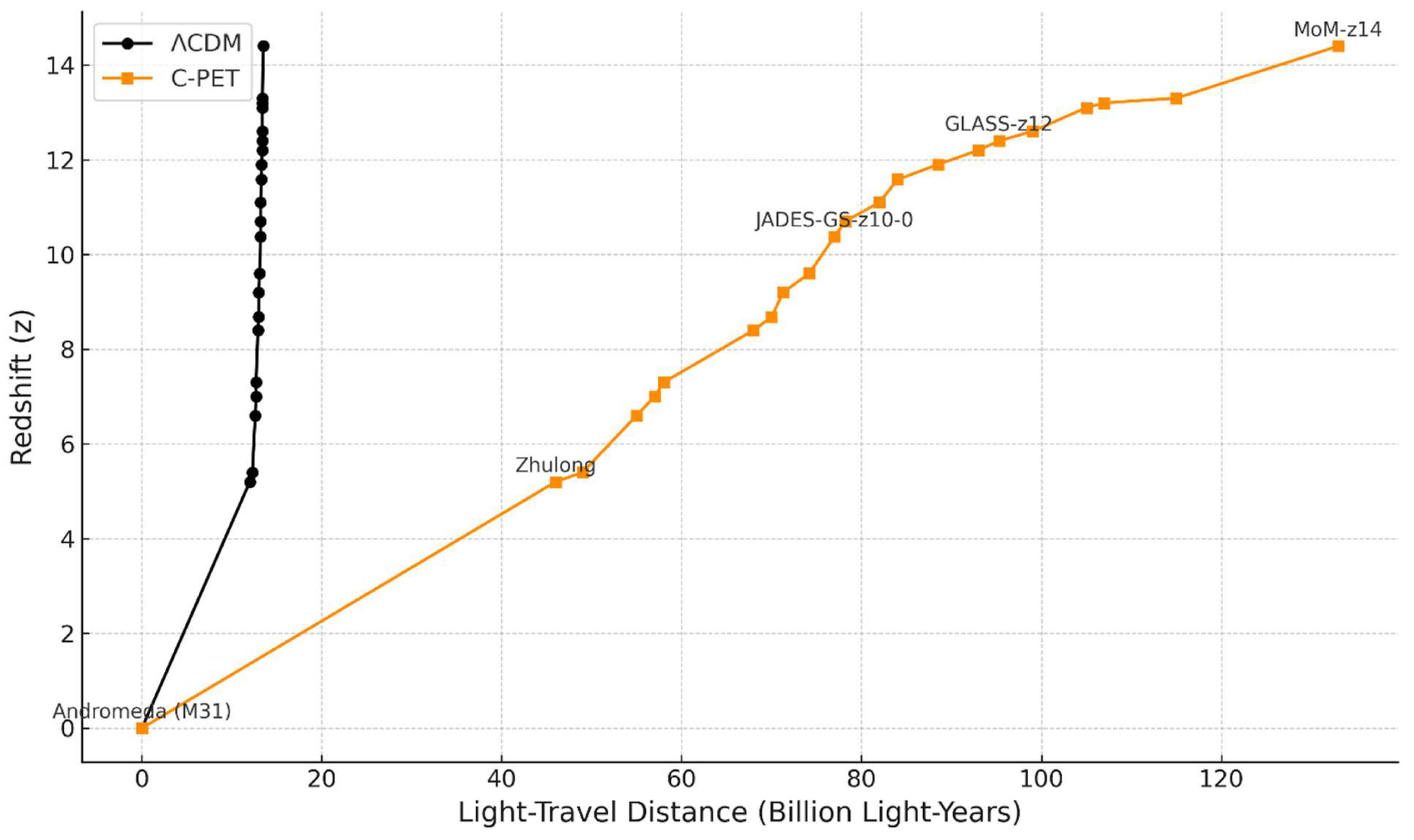

6.4.2. Galaxy Distance Comparison: ΛCDM vs. C-PET SMM

To complement the redshift–distance curves introduced in

Section 6.4.1, this section compares the inferred distances of 20 observed galaxies [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18] under two competing cosmological models: the ΛCDM expansion framework [

42,

43,

44] and the stochastic C-PET Segmented Medium Model (SMM).

In ΛCDM [

42,

43,

44], redshift is interpreted as a signal of metric expansion. As redshift increases, the light-travel distance grows rapidly at first, then asymptotically flattens, converging near ~13.8 billion light-years. This plateau reflects the model's finite-age constraint and fixed origin point. As a result, galaxies beyond z ≈ 10 are all compressed into a narrow range of light-travel distances, regardless of their increasing redshift values.

C-PET offers a fundamentally different interpretation. In this model, redshift accumulates through cumulative photon energy transfer as light traverses structured intergalactic media, voids, filaments, plasma halos, and more. Because the model imposes no temporal or spatial ceiling, the redshift–distance relationship remains open-ended. Higher redshift corresponds to longer, more interaction-rich paths, not to temporal proximity to a universal beginning.

Galaxy Distance Comparison

The table below compares inferred distances for a representative set of 20 well-known galaxies and deep-field sources [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18] under two cosmological frameworks: ΛCDM [

42,

43,

44] and the C-PET Segmented Medium Model (SMM). ΛCDM interprets redshift as a signal of expansion and places most high-z galaxies near the temporal boundary of the observable universe. In contrast, C-PET SMM, calibrated such that

z = 14.4 corresponds to ~133 BLY (see

Section 6.4), interprets redshift as a function of cumulative photon traversal through structured media, resulting in significantly greater inferred distances.

The ΛCDM values are based on standard light-travel distance calculations [

42,

43,

44], while C-PET SMM distances derive from a calibrated stochastic model of cumulative photon–medium interaction. The C-PET distances should not be interpreted as fixed or asserted measurements, but rather as plausible outcomes generated by the C-PET stochastic modeling framework under representative segment configurations. This comparison is intended to illustrate the implications of each model’s assumptions for large-scale cosmic structure, not to assert definitive galactic positions.

Table 6.4.2.1.

Inferred Distances for 20 Galaxies Under ΛCDM and C-PET SMM Models [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18,

73,

150].

Table 6.4.2.1.

Inferred Distances for 20 Galaxies Under ΛCDM and C-PET SMM Models [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18,

73,

150].

| Galaxy Name |

Redshift (z) |

ΛCDM Distance (BLY) |

C-PET Distance (BLY) |

| Andromeda (M31) |

0.001 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| Zhulong |

5.2 |

12.0 |

46.0 |

| JADES-GS-z5-0 |

5.4 |

12.3 |

49.0 |

| JADES-GS-z6-0 |

6.6 |

12.6 |

55.0 |

| RUBIES-UDS-QG-z7 |

7.0 |

12.7 |

57.0 |

| JADES-GS-z7-01 |

7.3 |

12.7 |

58.0 |

| JADES-GS-z8-0 |

8.4 |

12.9 |

68.0 |

| EGSY8p7 |

8.68 |

13.0 |

70.0 |

| JADES-GS-z9-0 |

9.2 |

13.0 |

71.3 |

| MACS1149-JD |

9.6 |

13.1 |

74.2 |

| JADES-GS-z10-0 |

10.4 |

13.2 |

77.0 |

| MACS0647-JD |

10.7 |

13.2 |

78.2 |

| GN-z11 |

10.6 |

13.2 |

82.0 |

| JADES-GS-z11-0 |

11.58 |

13.3 |

84.0 |

| UDFj-39546284 |

11.9 |

13.3 |

88.5 |

| GLASS-z12 |

12.3 |

13.4 |

95.3 |

| GLASS-z13 |

13.1 |

13.4 |

105.0 |

| JADES-GS-z13-0 |

13.2 |

13.4 |

107.0 |

| HD1 |

13.3 |

13.4 |

115.0 |

| MoM-z14 |

14.4 |

13.5 |

133.0 |

While ΛCDM constrains all of these galaxies to a narrow temporal horizon, C-PET allows them to occupy vastly greater distances, consistent with longer and more varied traversal paths.

The following chart visualizes the divergence in inferred galaxy distances under ΛCDM and the C-PET Segmented Medium Model, extending the comparison across this set of observational data.

Figure 6.4.2.1: Galaxy Distances Under ΛCDM vs. C-PET SMM

Note: This figure compares light-travel distances for a set of 20 observed galaxies [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,

18,

73,

150] across redshifts 0–14.4 under both ΛCDM and the canonical C-PET SMM model. Redshift is plotted on the x-axis, and light-travel distance on the y-axis. Blue markers and line represent ΛCDM values, which asymptote near ~13.8 BLY due to the model's finite temporal horizon. Orange markers and path represent C-PET SMM predictions, which continue to rise with redshift as a result of cumulative photon–medium interactions, reaching 133 BLY at z = 14.4.

Interpretation and Implications

Under ΛCDM, these high-z galaxies [

1,

2,

3,

16,

17,