1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as one of the most influential technologies of the 21st century, transforming various productive and social sectors, including the educational field (Halpin, 2005). Its evolution from the mathematical and philosophical foundations of the nineteenth century to its consolidation as a formal field at the 1956 Dartmouth Congress (Prasad & Choudhary, 2021), has all development of systems capable of emulating human cognitive processes, such as autonomous learning, decision-making and logical reasoning (Alieksieiev & Kurenkov, 2023).

In the context of higher education, AI has not only redefined access to information and modes of assessment but has introduced new pedagogical possibilities (Lin et al., 2023). Intelligent tutoring platforms, learning personalization algorithms, virtual assistants and automated feedback systems allow a continuous adaptation of content to the needs of each student ( Chiu et al., 2023; Ouyang & Jiao, 2021). These technologies, properly integrated into education ecosystems, can facilitate equity, inclusion, and improved learning outcomes (Lameras & Arnab, 2022). This transformation has led to the emergence of new pedagogical paradigms, often referred to as emerging pedagogies, which emphasize personalized, learner-centered, and data-informed instruction facilitated by AI (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). These pedagogies advocate for adaptive feedback, intelligent assessment, and dynamic learning environments that are responsive to student needs and contexts.

However, the integration of these tools poses critical challenges. One of the most relevant is the risk of a functional dependence on AI systems, especially in routine academic tasks such as writing, problem-solving or organizing ideas. This phenomenon, observed in contexts where tools such as ChatGPT are widely used, can limit the development of higher cognitive competencies, such as reflection, critical analysis, and intellectual autonomy (Viselli, 2021; Wang & Wang, 2022)

Moreover, the incorporation of AI in education does not occur in a cultural vacuum. Students' attitudes towards these technologies, both positive and negative, condition their appropriation and meaningful use (Slimi et al., 2025). Some studies report optimism about AI's potential for personalized and efficient learning, while others emphasize concerns over plagiarism, reduced creativity, or diminished self-reliance (Farinosi & Melchior, 2025). These concerns have a direct impact on the planning of instructional strategies and assessment models, as the potential misuse of AI tools may compromise academic integrity (Michel-Villarreal et al., 2023). Educators are thus urged to adopt proactive pedagogical frameworks that promote transparency, originality, and ethical reasoning, integrating formative assessments and reflective practices that reduce the likelihood of academic dishonesty (Perkins, 2023).

Given these complexities, AI must be framed within ethical and equity-based approaches, particularly in regions marked by digital divides. Access to AI tools should be complemented by policies that uphold fairness and inclusivity (UNESCO, 2022). Educational institutions are urged to establish governance models and training programs that support digital literacy and ensure that all students, regardless of geographic, economic, or cultural background, benefit from AI equitably (Holmes et al., 2019).

In alignment with global educational policy frameworks, the responsible integration of AI in teaching and learning must be situated within the broader paradigm of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). ESD promotes competencies such as critical thinking, responsible decision-making, and digital ethics—all essential in AI-mediated environments. Moreover, this research contributes to the advancement of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), by analyzing how AI shapes educational experiences in diverse socio-technological contexts. Emphasizing responsible and inclusive digital transformation, the study underscores the need to reimagine higher education in ways that are pedagogically sound, ethically robust, and socially just.

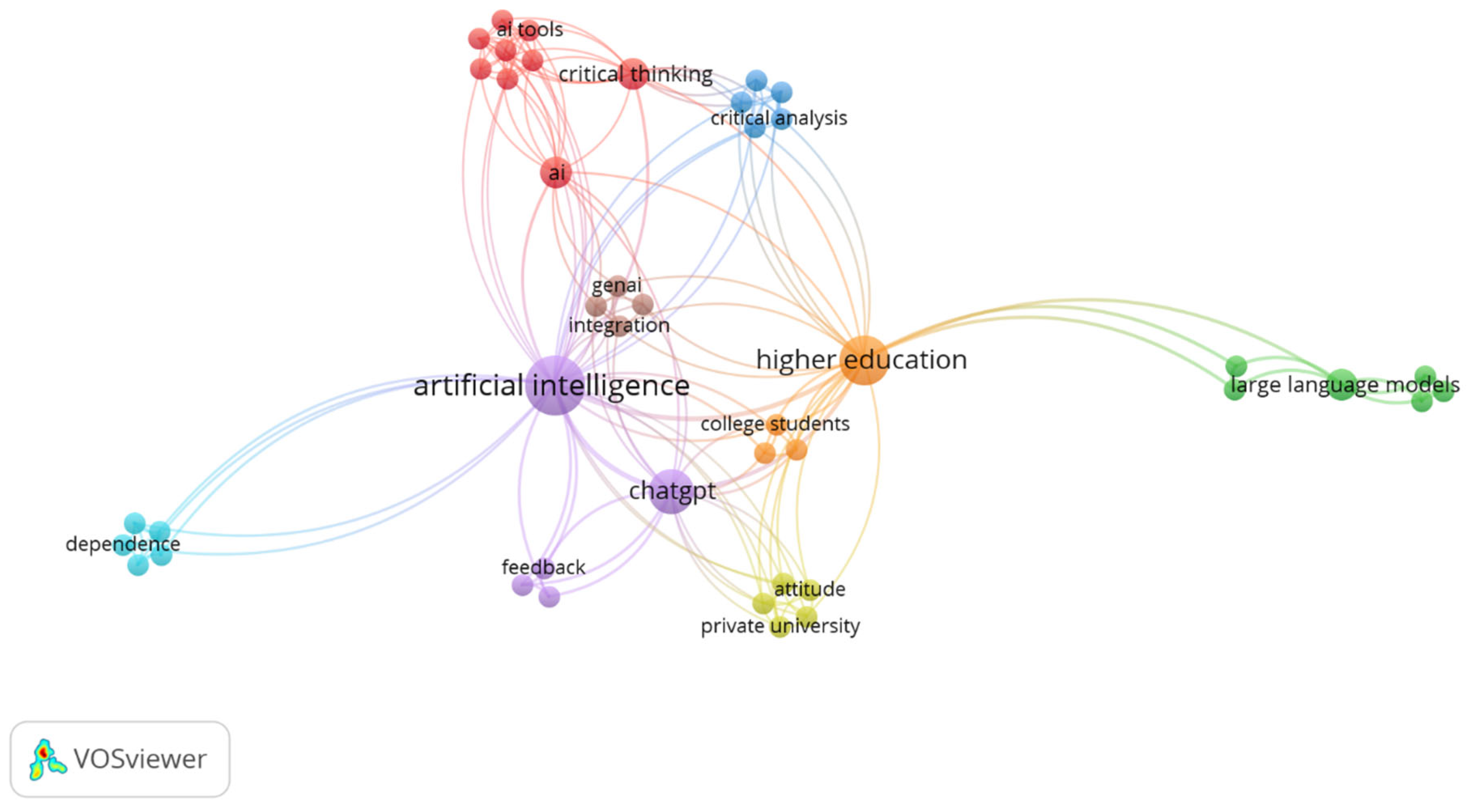

To highlight these interconnections,

Figure 1 presents a semantic network of key terms, such as "AI tools," "critical thinking," and "attitudes”that exemplify the centrality of reflective, inclusive, and critical approaches to technology adoption in educational settings.

The growing adoption of generative AI tools like ChatGPT has improved student productivity in tasks such as writing and organizing ideas (Anani et al., 2025; Sáez-Velasco et al., 2025). Nevertheless, concerns persist about how this reliance may affect creativity and critical thought, suggesting that overuse could hinder the development of autonomous learning skills (Zakarneh et al., 2025).

Teachers recognize the pedagogical advantages of AI, especially in terms of personalization of learning, but agree that adequate training is essential to ensure ethical use and avoid problems such as plagiarism and academic integrity (Aljabr & Al-Ahdal, 2024). Despite the concerns, many studies claim that integrating AI into classrooms can improve academic outcomes, especially when combined with well-structured pedagogical approaches (Gonzalez-Garcia et al., 2025; Slimi et al., 2025).

Although students use AI tools primarily to define concepts, generate ideas, and help with grammar correction and translation, they also mention concerns about the reliability of the information generated and the risk of plagiarism (Almassaad et al., 2024; Farinosi & Melchior, 2025). Despite the fact that AI tools are seen as effective, some students warn that excessive use could affect their ability to generate knowledge independently (M. Li & Rohayati, 2024; Uppal et al., 2023). This tension between perceived benefits and risks of technological dependency underscores the need to establish clear guidelines and an ethical framework for the adoption of these tools in academia (Falebita & Kok, 2025; Merzifonluoglu & Gunes, 2025).

Although AI may improve learning, unbalanced use could suppress independent reasoning. Studies show that students may trust AI-generated content uncritically, compromising reflective engagement (Albayati et al., 2022; Jomaa et al., 2024; Šedlbauer et al., 2024). This over-reliance fosters superficial learning and weakens autonomous cognitive development. Research further suggests that AI, when used improperly, can hinder students' capacity to analyze and solve complex problems (Özmat & Akkoyunlu, 2024; Wood & Moss, 2024). Also, Le et al. (2025) note a growing dependence on ChatGPT among students who forgo critical evaluation of content.

Although AI can enrich learning increasing familiarity can lead to dependency, potentially undermining autonomous learning (Djokic et al., 2024; Vázquez-Parra et al., 2024). This reinforces the need for ethical guidelines and pedagogical frameworks that support critical engagement. Similar concerns have emerged in professional training. Studies in fields like translation and accounting indicate that reliance on AI for technical tasks may affect independent decision-making and professional development (Grájeda et al., 2024; Karkoulian et al., 2024; Musyaffi et al., 2024; Özmat & Akkoyunlu, 2024).

Despite growing global interest in AI’s educational impact, few studies address its implications in socioculturally specific contexts like Ecuador, where technological adoption is still emerging. This study addresses that gap by examining how AI dependence may affect the development of autonomous skills in Ecuadorian university students. It also provides evidence to guide institutional policies and pedagogical strategies that encourage ethical, balanced, and context-sensitive use of AI.

The Present Study

The general purpose of this study is to evaluate the dependence of university students on AI tools, as measured by the Artificial Intelligence Dependence Scale (DAI), as well as the general attitudes they have towards AI, as measured by the General Attitudes Towards Artificial Intelligence Scale (GAAIS) in the context of higher education in Ecuador. Therefore, the following objectives are proposed: a) To evaluate the degree of dependence of students on AI tools in their academic activities; b) To identify the general attitudes of students towards the integration of AI in the educational process; c) Compare differences in dependence and attitudes towards AI based on demographic variables such as gender, age, and academic career; d) To predict the degree of dependence on AI based on students' attitudes and sociodemographic variables, using a robust regression model.

From these objectives, it is hypothesized that students who frequently use AI tools for their academic activities will have a greater degree of dependence on these technologies (H1); attitudes towards AI will be more positive in students in technological areas compared to those in more traditional careers (H2); there are significant differences in dependence and attitudes towards AI according to students' gender, age, and academic career (H3); attitudes towards AI, both positive and negative, are significant predictors of the degree of students' dependence on AI tools, and sociodemographic variables, such as housing area and academic level, have a moderating effect on this relationship (H4).

2. Materials and Methods

Research Design

This study adopted a quantitative, non-experimental, cross-sectional, and correlational-predictive design, aimed at examining the relationships between university students’ attitudes toward AI and their level of perceived dependence on AI tools within academic contexts (Ato et al., 2013). The research seeks to identify attitudinal patterns and predictive variables to inform pedagogical practices and institutional policies that promote a balanced, ethical, and inclusive integration of AI in higher education. Moreover, this design contributes to the broader framework of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) by analyzing how digital technologies affect learner autonomy and critical thinking in ways aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

Participants

The present study included a sample of 540 Ecuadorian university students, composed of 38.57% men and 61.42% women, whose ages ranged from 17 to 35 years (M = 20.68; SD = 3.02). The ethnic composition revealed that 93.88% identified as mestizo, while the remaining 6.12% were distributed between Indigenous, Afro-Ecuadorian, and white identities. A significant proportion of the participants resided in urban areas (67.40%). Regarding the predominant marital status, it was single, representing 92.77% of the sample. Regarding their mode of study, 99.81% stated that they were enrolled in face-to-face mode.

Participants were selected through non-probabilistic convenience sampling, due to limitations in access to probabilistic registries across institutions. While this method restricts the generalizability of the findings, it was considered appropriate for exploratory research in underrepresented educational contexts. This inclusion criteria were considered: a) voluntary participation; b) Educational level according to age to guarantee understanding of the instruments. Exclusion criteria included: (a) presence of intellectual disability; b) effects of substances or drugs that affect consciousness; c) lack of command of the Spanish language.

This demographic structure reflects key variables—such as geographic location and ethnicity—that are crucial for developing equitable strategies for AI integration in education.

Instruments

Two validated scales were used for data collection:

General Attitudes Towards Artificial Intelligence Scale (GAAIS): Developed by Schepman & Rodway (2023), this scale aims to assess general attitudes towards AI in various contexts, including education. The GAAIS consists of 20 items, grouped into two dimensions: positive and negative attitudes towards AI. The measurement is conducted using a 5-point Likert scale, where 0 represents "Strongly disagree" and 4 "Strongly agree". Regarding its psychometric properties, the GAAIS has shown a high internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.85 for the dimension of positive attitudes and 0.82 for the dimension of negative attitudes (Gálvez Marquina et al., 2024).

Artificial Intelligence Dependency Scale (AID): Developed by Morales-García et al. (2024) whose purpose is to measure the degree of dependence of students on AI tools in the educational context. It consists of 5 items, measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree). With respect to their psychometric properties, they are particularly good with a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.87, which constitutes an exceptionally good robustness of the instrument.

Both instruments are considered suitable for assessing psychological constructs essential to understanding AI use within sustainable and ethically aware learning environments.

Procedure

Data collection was conducted through an online form hosted on the Google Forms platform. Previously, an informed consent was incorporated, detailing the objectives of the study, the voluntary nature of participation and the guarantees of anonymity and confidentiality. The link was distributed through university institutional channels, including academic emails and internal networks. Once the form was completed, the responses were automatically stored in a Google Sheets spreadsheet, making it easier to prepare the database for statistical analysis. The procedure was approved by the corresponding ethics committee, in accordance with the ethical principles established by the Declaration of Helsinki for research with human beings. This process aligns with ethical research practices and supports inclusive, culturally sensitive research in line with SDG-related education policies.

Data Analysis

The statistical analysis was structured in four interrelated methodological blocks, with the aim of robustly examining the relationships between dependence on AI and student attitudes in the context of higher education. In a first stage, a preliminary descriptive analysis of the variables was conducted, calculating measures of central tendency such as the arithmetic mean (M), dispersion through the standard deviation (SD) and distribution through the coefficients of asymmetry (g₁) and kurtosis (g₂). Univariate normality was assessed by accepting values of g₁ and g₂ within the range ±1.5 (Tabachnick et al., 2018). And multivariate normality through the test of Mardia (1970), considering that when there is no significance (p > .05) in multivariate g1 and g2 indicates the fulfillment of this assumption.

Subsequently, the general fit model was examined by means of an analysis of the internal consistency of the instruments using McDonald's omega coefficient (ω), a more appropriate indicator than Cronbach's alpha on scales with multidimensional structures (Campo-Arias & Oviedo, 2008; Gerbing & Anderson, 1988). Additionally, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was conducted to evaluate the relationships between the latent variables—positive attitudes, negative attitudes, and AI dependence. The SEM was estimated using the Diagonal Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) method, appropriate for ordinal data that do not meet the assumption of multivariate normality, and the variables are ordinal (L. Li et al., 2022; Moreta-Herrera et al., 2025). For the fit of the model, the indices Chi square (χ²), Chi square normed (χ²/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Standardized Mean Square Residual (SRMR) and Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the factor loads (λ) of the items were considered. The fit model is considered appropriate when the value of χ² is p > .05 or χ²/df is less than 4; CFI and TLI is greater than .95; and SRMR and RMSEA are less than .06 (although tolerances of .08 are acceptable) (Browne & Cudeck, 1992; Byrne, 2008; Wolf et al., 2013; Yang-Wallentin et al., 2010). Finally, the factor loads (λ) of the items were considered adequate if they exceed the value of λ > .40 (Dominguez-Lara, 2018).

In a third stage, the scores obtained in the scales were compared according to sociodemographic variables (sex, area of residence) and academic variables (general average), for dichotomous variables the Wilcoxon rank sum test (also known as the Mann–Whitney U) test was applied (Frey, 2023), and for comparisons between more than two groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used (Ostertagová et al., 2014). The level of statistical significance was established at p < .05 (Divine et al., 2018).

Finally, a robust regression model with standard errors corrected for heteroskedasticity was estimated, in order to identify the significant predictors of dependence on AI (García & Servy, 2007). In the first model, the global score of the attitude scale (GAAIS) was introduced; the second model incorporated the subdimensions of positive and negative attitudes; and the third model additionally included sociodemographic variables such as area of residence and academic level. In all cases, standardized coefficients (β), standard errors (SE) and t-values were reported, considering those with p < .05 significant (Sperandei, 2014). All predictors were treated as continuous variables, using total or subscale scores as independent variables.

The statistical analyses used in the studies were performed using the programming language R, version 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2024) and the packages used were lavaan, semTools, MBESS, and dplyr.

Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI)

Generative AI (GenAI) tools were not used in the design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of this study. However, AI-assisted tools were employed in a limited capacity to support linguistic editing, specifically for grammar correction and improving textual cohesion. These tools did not contribute to content generation, scientific argumentation, or any substantive aspect of the manuscript.

3. Results

Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 shows a preliminary analysis of the instruments used, including GAAIS and DAI, along with their respective dimensions. The means (M) and standard deviations (SD) of the total and partial scores are observed, where the GAAIS presents an overall mean of 67.72 (SD = 13.93), with its subdimensions of positive and negative attitudes showing means of 33.56 (SD = 7.32) and 34.15 (SD = 7.70), respectively. In contrast, the DAI presents a total mean of 12.04 (SD = 5.42). The coefficients of asymmetry (g1) and kurtosis (g2) reflect negatively skewed distributions for all factors, with values ranging from -0.824 to -0.222 for asymmetry, and from -0.128 to 1.87 for kurtosis. Mardia's statistics show a significant deviation from multivariate normality in both scales, with highly significant values for bias (p < 0.01) and kurtosis (p < 0.05). These preliminary results suggest that the scores of the instruments do not follow a multivariate normal distribution, a relevant aspect for the selection of appropriate statistical methods in subsequent analyses.

General Fit Model

Table 2 shows the analysis of the internal consistency of the instruments used, expressed through McDonald's omega coefficient (ω) and their respective 95% confidence intervals. GAAIS is highly dependable, with a total omega coefficient of 0.93 [0.92–0.94]. Its subdimensions also show robust internal consistency, with ω values of 0.87 [0.84–0.89] for positive attitudes and 0.92 [0.90–0.93] for negative attitudes. On the other hand, the DAI shows adequate reliability with an omega coefficient of 0.85 [0.83–0.87]. These results indicate that both instruments have a high internal coherence in the sample analyzed, which supports their use for the measurement of attitudes and dependence towards AI.

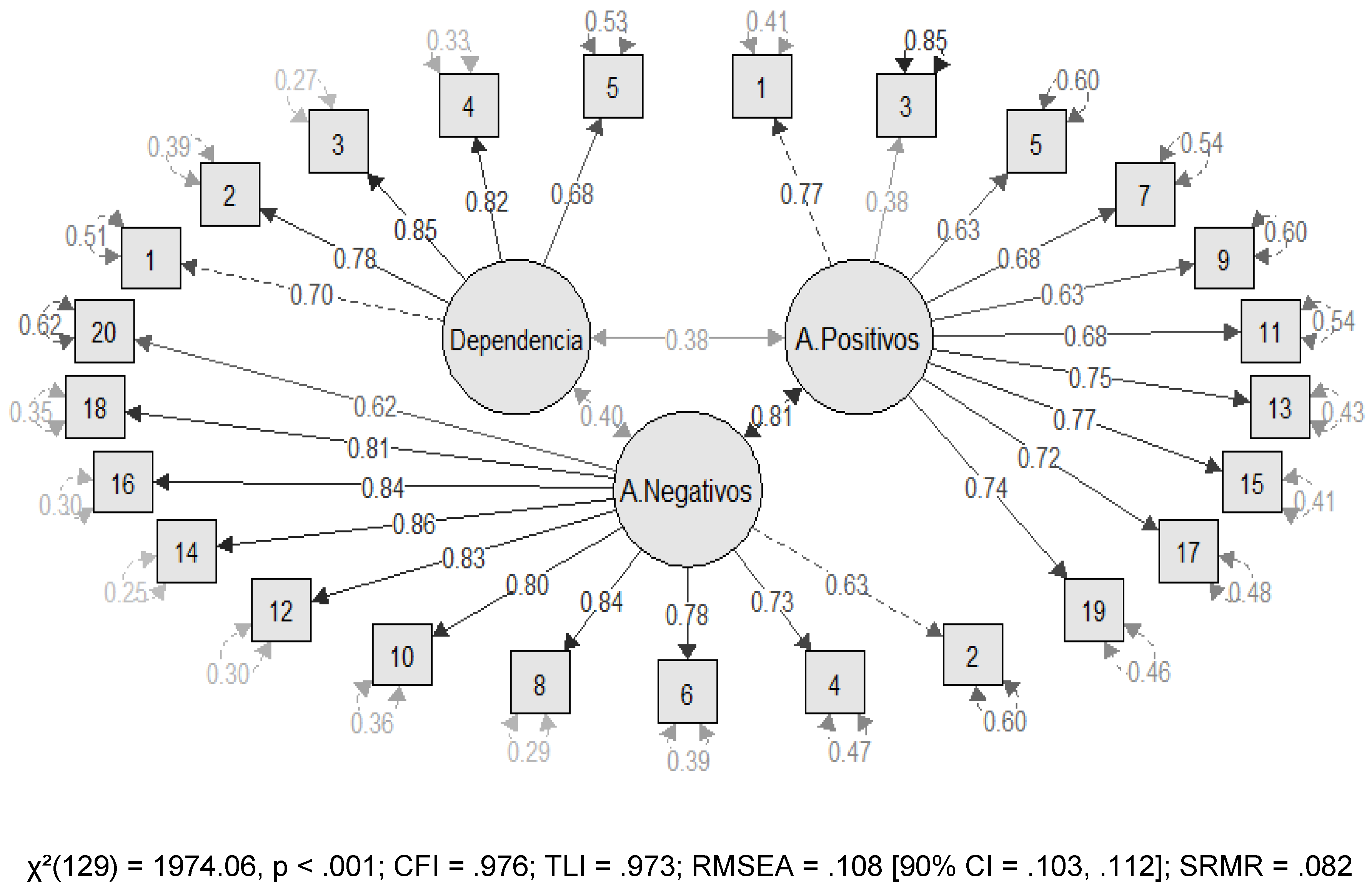

Figure 2 shows the structural equation model designed to analyze the relationship between attitudes toward AI and perceived dependence. The model includes three latent factors (dependence, positive and negative attitudes), with significant standardized factor loads above .60 in most cases, which shows adequate structural validity. The burdens were especially high in the dimension of negative attitudes (λ = .80–.86), followed by the dimensions of dependence and positive attitudes.

Regarding the global fit, the model showed a significant chi-square (χ² (129) = 1974.06, p < .001), which was expected from the sample size. However, the CFI (.976) and TLI (.973) indices indicate an excellent comparative fit. RMSEA (.108; 90% CI [.103, .112]) and SRMR (.082) are above the optimal values, suggesting a partial adjustment in the residuals. Despite this, the general structure of the model is considered acceptable and coherent with the theoretical constructs evaluated.

Comparison of Scales According to Sociodemographic and Academic Variables

Table 3 presents the results of the differences in the DAIS and GAAIS scales (including their positive and negative dimensions) according to sociodemographic variables (sex, housing area) and academic variables (academic average). For comparisons by sex and area of residence, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used, while the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied for the academic average. The results indicate that there were no statistically significant differences between men and women on any of the scales (p > .05). However, significant differences were observed in the DAI scale (p = .026) and in negative attitudes (p = .0023) according to the living area, suggesting a possible contextual effect. On the other hand, comparisons according to academic average did not show significant differences (p > .05), which reinforces the limited influence of this variable on attitudes and dependence towards AI.

Robust Regression for AI Dependency

Table 4 presents the results of three robust regression models designed to predict AI dependence. In Model 1, the independent variable is the GAAIS index, which shows a significant positive coefficient (β = 0.151, t = 9.549), indicating that the higher the score on this scale, the greater the perceived dependence on AI. In Model 2, positive and negative attitudes towards AI are included as predictors, both with significant positive coefficients (β = 0.155, t = 3.573 and β = 0.148, t = 3.584 respectively), suggesting that both a higher favorable and unfavorable rating positively influence dependence, possibly reflecting a complex attitudinal relationship. Finally, Model 3 also incorporates sociodemographic variables, such as housing area (urban) and academic level (with categories "Notable" and "Sufficient"), where attitudes maintain their significant effect, especially negative ones (β = 0.176, t = 4.236), while sociodemographic variables present positive coefficients but do not reach clear statistical significance. Taken together, these results show that attitudes towards AI are robust predictors of perceived dependence, while demographic characteristics play a secondary role.

4. Discussion

This study provides empirical evidence on the relationship between Ecuadorian university students and AI-based technologies in academic contexts. The findings indicate a moderate level of dependence, suggesting a phase of progressive but incomplete consolidation. This aligns with prior research highlighting a gradual incorporation of AI in higher education, where ethical concerns and perceived utility interactively shape acceptance (Chiu et al., 2023; Ouyang & Jiao, 2021).

Attitudes toward AI show marked duality, with comparable levels of positive and negative perceptions. This ambivalence is consistent with theoretical models from technology adoption and social psychology, which posit that users can simultaneously value benefits such as personalization and efficiency, while expressing concerns related to privacy, autonomy, and academic integrity (Hermansyah et al., 2023; Viselli, 2021). These findings reinforce the notion that AI integration must go beyond technological deployment to include pedagogical frameworks that promote metacognitive reflection and student agency (Holmes et al., 2019; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019).

A key insight is that both positive and negative attitudes significantly predict AI dependence. This paradox reflects the functionalization of AI: it is viewed as indispensable regardless of critical views, given the academic pressures to adapt to digital environments (Ahmed et al., 2023; Paranjape et al., 2019). Therefore, instructional designs must include scaffolding and formative assessments that foster ethical reasoning and reduce superficial learning risks.

At the sociodemographic level, no significant differences were found by gender, contrary to studies noting digital gaps (Zhang & Aslan, 2021)This may indicate progress in digital equity at the university level in Ecuador. However, significant differences by residence area were observed: urban students reported greater dependence and more negative attitudes. This may stem from increased exposure and digital saturation, generating both intensive use and heightened ethical concerns (Hermansyah et al., 2023). These patterns point to the need for targeted institutional strategies that address digital divides through infrastructure investment and localized digital training programs.

In contrast, academic performance showed no significant relationship with attitudes or dependence, highlighting the influence of contextual and cultural factors. This suggests that curricula should embed digital ethics, critical thinking, and self-regulation skills as transversal competencies (Brüns & Meißner, 2024; Kharisma et al., 2023). Moreover, student concerns about plagiarism and loss of creativity emphasize a pressing pedagogical challenge: ensuring academic integrity in AI-rich environments. Authentic assessment models that privilege process over product are essential in this regard (Karkoulian et al., 2024; Perkins, 2023).

Taken together, these results support the view that AI integration in education must be pedagogically intentional, ethically grounded, and culturally responsive. This is especially critical in Latin America, where digital transformation intersects with structural inequalities. In this context, the study aligns with the goals of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), which emphasizes responsible innovation, social justice, and the development of digital and cognitive competencies for sustainability. Moreover, the findings contribute to the advancement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), by highlighting the sociotechnical dynamics that condition educational access and equity (UNESCO, 2022).

From an applied perspective, the study identifies priority actions for higher education institutions. First, it is essential to implement data protection and algorithmic transparency policies, particularly regarding AI systems that process student data (Hermansyah et al., 2023). Second, sustained teacher training on AI integration is required to ensure meaningful, ethical use in diverse instructional contexts (Paranjape et al., 2019). Third, equity-focused policies must be adopted to guarantee fair access to technological resources, especially in underserved areas.

Finally, future research should expand on these findings through longitudinal and mixed methods approaches, which would allow deeper analysis of attitudinal shifts over time. It is also necessary to explore the perspectives of educators and institutional leadership, as these are key actors in scaling sustainable AI use across educational systems. The broader educational challenge is not simply to integrate AI, but to do so in ways that support inclusion, justice, and intellectual autonomy—pillars of a truly sustainable digital education paradigm.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed a complex relationship between Ecuadorian university students and AI technologies in academic settings, characterized by moderate dependence and ambivalent attitudes. Both positive and negative perceptions significantly predicted AI dependence, indicating a functional use of these tools beyond personal preference.

No significant differences were found by gender or academic performance, but students from urban areas reported greater dependence and ethical concerns, reflecting underlying geographic disparities. These findings highlight the importance of promoting digital equity and inclusive access to AI-supported learning.

Responsible AI integration in higher education requires pedagogical models that foster critical thinking, autonomy, and ethical awareness, supported by continuous teacher training and institutional data governance. The study contributes to the principles of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and aligns with SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by identifying key social and technological factors shaping AI use in learning. Future research should explore long-term impacts and institutional readiness to ensure AI adoption advances pedagogical relevance, inclusion, and sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.A. and J.C.G.; methodology, C.M.A.; software, E.M.A.; validation, C.M.A., J.C.G., and E.M.H.; formal analysis, C.M.A.; investigation, C.M.A., J.C.G., and D.B.J.; resources, E.M.A. and D.B.J.; data curation, C.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.A.; writing—review and editing, J.C.G., E.M.H., and D.B.J.; visualization, E.M.A.; supervision, J.C.G.; project administration, C.M.A.; funding acquisition, D.B.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was not externally funded.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the national guidelines for the protection of human rights in research established by Ecuadorian regulatory bodies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. A digital informed consent form was included on the first page of the questionnaire administered via Google Forms.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to their home institution for the academic and administrative support provided throughout the development of this study. Special thanks are extended to our families, whose encouragement, patience, and unwavering support made this work possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| DAI |

Artificial Intelligence Dependence Scale |

| GAAIS |

General Attitudes Toward Artificial Intelligence Scale |

| HE |

Higher Education |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| SEM |

Structural Equation Modeling |

| RMSEA |

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR |

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| CFI |

Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI |

Tucker–Lewis Index |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

References

- Ahmed, Z., Zeeshan, S., & Lee, D. (2023). Editorial: Artificial intelligence for personalized and predictive genomics data analysis. In Frontiers in Genetics (Vol. 14). [CrossRef]

- Albayati, M. G., De Oliveira, J., Patil, P., Gorthala, R., & Thompson, A. E. (2022). A market study of early adopters of fault detection and diagnosis tools for rooftop HVAC systems. Energy Reports, 8, 14915–14933. [CrossRef]

- Alieksieiev, M., & Kurenkov, V. (2023). ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE: ORIGINS AND PROBLEMS. [CrossRef]

- Aljabr, F. S., & Al-Ahdal, A. A. M. H. (2024). Ethical and pedagogical implications of AI in language education: An empirical study at Ha’il University. Acta Psychologica, 251, 104605. [CrossRef]

- Almassaad, A., Alajlan, H., & Alebaikan, R. (2024). Student Perceptions of Generative Artificial Intelligence: Investigating Utilization, Benefits, and Challenges in Higher Education. Systems, 12(10), 385. [CrossRef]

- Anani, G. E., Nyamekye, E., & Bafour-Koduah, D. (2025). Using artificial intelligence for academic writing in higher education: the perspectives of university students in Ghana. Discover Education, 4(1), 46. [CrossRef]

- Ato, M., López, J. J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicologia, 29(3), 1038–1059. [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2). [CrossRef]

- Brüns, J. D., & Meißner, M. (2024). Do you create your content yourself? Using generative artificial intelligence for social media content creation diminishes perceived brand authenticity. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 79. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2008). Testing for multigroup equivalence of a measuring instrument: A walk through the process. Psicothema, 20(4).

- Campo-Arias, A., & Oviedo, H. C. (2008). Propiedades psicométricas de una escala: La consistencia interna. In Revista de Salud Publica (Vol. 10, Issue 5, pp. 831–839). Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T. K. F., Xia, Q., Zhou, X., Chai, C. S., & Cheng, M. (2023). Systematic literature review on opportunities, challenges, and future research recommendations of artificial intelligence in education. In Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 4). [CrossRef]

- Divine, G. W., Norton, H. J., Barón, A. E., & Juarez-Colunga, E. (2018). The Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney Procedure Fails as a Test of Medians. American Statistician, 72(3). [CrossRef]

- Djokic, I., Milicevic, N., Djokic, N., Malcic, B., & Kalas, B. (2024). Students’ Perceptions of the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Educational Service. Amfiteatru Economic, 26(65), 294. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Lara, S. (2018). Propuesta de puntos de corte para cargas factoriales: una perspectiva de fiabilidad de constructo. Enfermería Clínica, 28(6). [CrossRef]

- Falebita, O. S., & Kok, P. J. (2025). Artificial Intelligence Tools Usage: A Structural Equation Modeling of Undergraduates’ Technological Readiness, Self-Efficacy and Attitudes. Journal for STEM Education Research, 8(2), 257–282. [CrossRef]

- Farinosi, M., & Melchior, C. (2025). ‘I Use <scp>ChatGPT</scp>, but Should I?’ A Multi-Method Analysis of Students’ Practices and Attitudes Towards <scp>AI</scp> in Higher Education. European Journal of Education, 60(2). [CrossRef]

- Frey, B. B. (2023). Mann-Whitney Test. In There’s a Stat for That!: What to Do & When to Do It. [CrossRef]

- Gálvez Marquina, M. C., Pinto-Villar, Y. M., Mendoza Aranzamendi, J. A., & Anyosa Gutiérrez., B. J. (2024). Adaptación y validación de un instrumento para medir las actitudes de los universitarios hacia la inteligencia artificial. Revista de Comunicación, 23(2), 125–142. [CrossRef]

- García, M. del C., & Servy, E. (2007). Regresión robusta: Una aplicación. Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Estadística. Universidad Nacional de Rosario.

- Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1988). An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2), 186–192. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Garcia, A., Bermejo-Martinez, D., Lopez-Alonso, A. I., Trevisson-Redondo, B., Martín-Vázquez, C., & Perez-Gonzalez, S. (2025). Impact of ChatGPT usage on nursing students education: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon, 11(1), e41559. [CrossRef]

- Grájeda, A., Córdova, P., Córdova, J. P., Laguna-Tapia, A., Burgos, J., Rodríguez, L., Arandia, M., & Sanjinés, A. (2024). Embracing artificial intelligence in the arts classroom: understanding student perceptions and emotional reactions to AI tools. Cogent Education, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Halpin, H. (2005). The Semantic Web: The Origins of Artificial Intelligence Redux. Third International Workshop on the History and Philosophy of Logic, Mathematics and Computation (HPLMC-04 2005), 44(0).

- Hermansyah, M., Najib, A., Farida, A., Sacipto, R., & Rintyarna, B. S. (2023). Artificial Intelligence and Ethics: Building an Artificial Intelligence System that Ensures Privacy and Social Justice. International Journal of Science and Society, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W., Maya, B., & Fadel, C. (2019). Artificial Intelligence in Education Promises and Implications for Teaching. In Journal of Computer Assisted Learning (Vol. 14, Issue 4).

- Jomaa, N., Attamimi, R., & Al Mahri, M. (2024). The Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Teaching English Vocabulary in Oman: Perspectives, Teaching Practices, and Challenges. World Journal of English Language, 15(3), 1. [CrossRef]

- Karkoulian, S., Sayegh, N., & Sayegh, N. (2024). ChatGPT Unveiled: Understanding Perceptions of Academic Integrity in Higher Education - A Qualitative Approach. Journal of Academic Ethics. [CrossRef]

- Kharisma, D. B., Sudirman, S., Edi, F., & S, R. R. P. M. (2023). Current Trend of Artificial Intelligence-Augmented Reality in Science Learning: Systematic Literature Review. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA, 9(8). [CrossRef]

- Lameras, P., & Arnab, S. (2022). Power to the Teachers: An Exploratory Review on Artificial Intelligence in Education. Information (Switzerland), 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Le, T. T. H., Dang, V. U., Dang, H. K., & Nguyen, T. T. (2025). Applying AI Tools to Develop a Curriculum Based on Expected Learning Outcomes and Personalize Learning Program for Students at the University of Languages and International Studies. European Journal of Educational Research, 14(2), 415–427. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Niu, Z., Mei, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). A network analysis approach to the relationship between fear of missing out (FoMO), smartphone addiction, and social networking site use among a sample of Chinese university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 128. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., & Rohayati, M. I. (2024). A Bibliometric Analysis of Artificial Intelligence Applications in Global Higher Education. International Journal of Information System Modeling and Design, 16(1), 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. C., Huang, A. Y. Q., & Lu, O. H. T. (2023). Artificial intelligence in intelligent tutoring systems toward sustainable education: a systematic review. In Smart Learning Environments (Vol. 10, Issue 1). [CrossRef]

- Mardia, K. V. (1970). Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika, 57(3). [CrossRef]

- Merzifonluoglu, A., & Gunes, H. (2025). Shifting Dynamics: Who Holds the Reins in Decision-Making with Artificial Intelligence Tools? Perspectives of Gen Z Pre-Service Teachers. European Journal of Education, 60(1). [CrossRef]

- Michel-Villarreal, R., Vilalta-Perdomo, E., Salinas-Navarro, D. E., Thierry-Aguilera, R., & Gerardou, F. S. (2023). Challenges and Opportunities of Generative AI for Higher Education as Explained by ChatGPT. Education Sciences, 13(9). [CrossRef]

- Morales-García, W. C., Sairitupa-Sanchez, L. Z., Morales-García, S. B., & Morales-García, M. (2024). Development and validation of a scale for dependence on artificial intelligence in university students. Frontiers in Education, 9. [CrossRef]

- Moreta-Herrera, R., Caycho-Rodríguez, T., Salinas, A., Jiménez-Borja, M., Gavilanes-Gómez, D., & Jiménez-Mosquera, C. J. (2025). Factorial Validity, Reliability, Measurement Invariance and the Graded Response Model for the COVID-19 Anxiety Scale in a Sample of Ecuadorians. Omega (United States), 90(3), 1078–1093. [CrossRef]

- Musyaffi, A. M., Baxtishodovich, B. S., Afriadi, B., Hafeez, M., Adha, M. A., & Wibowo, S. N. (2024). New Challenges of Learning Accounting with Artificial Intelligence: The Role of Innovation and Trust in Technology. European Journal of Educational Research, volume-13-2024(volume-13-issue-1-january-2024), 183–195. [CrossRef]

- Ostertagová, E., Ostertag, O., & Kováč, J. (2014). Methodology and application of the Kruskal-Wallis test. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 611, 115–120. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F., & Jiao, P. (2021). Artificial intelligence in education: The three paradigms. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2. [CrossRef]

- Özmat, D., & Akkoyunlu, B. (2024). Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Translation in Education: Academic Perspectives and Student Approaches. Participatory Educational Research, 11(H. Ferhan Odabaşı Gift Issue), 151–167. [CrossRef]

- Paranjape, K., Schinkel, M., Panday, R. N., Car, J., & Nanayakkara, P. (2019). Introducing artificial intelligence training in medical education. In JMIR Medical Education (Vol. 5, Issue 2). [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M. (2023). Academic Integrity considerations of AI Large Language Models in the post-pandemic era: ChatGPT and beyond. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 20(2). [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R., & Choudhary, P. (2021). State-of-the-art of artificial intelligence. Journal of Mobile Multimedia, 17(1–3). [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. In R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/.

- Sáez-Velasco, S., Alaguero-Rodríguez, M., Rodríguez-Cano, S., & Delgado-Benito, V. (2025). Students’ Attitudes Towards AI and How They Perceive the Effectiveness of AI in Designing Video Games. Sustainability, 17(7), 3096. [CrossRef]

- Schepman, A., & Rodway, P. (2023). The General Attitudes towards Artificial Intelligence Scale (GAAIS): Confirmatory Validation and Associations with Personality, Corporate Distrust, and General Trust. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(13), 2724–2741. [CrossRef]

- Šedlbauer, J., Činčera, J., Slavík, M., & Hartlová, A. (2024). Students’ reflections on their experience with <scp>ChatGPT</scp>. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 40(4), 1526–1534. [CrossRef]

- Slimi, Z., Benayoune, A., & Alemu, A. E. (2025). Students’ Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Integration in Higher Education. European Journal of Educational Research, 14(2), 471–484. [CrossRef]

- Sperandei, S. (2014). Understanding logistic regression analysis. Biochemia Medica, 24(1). [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., & Ullman, J. B. (2018). Using Multivariate Statistics (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson, 7th editio, 52–98.

- UNESCO. (2022). Global Education Monitoring Report. https://www.unesco.org/gem-report/en.

- Uppal, M., Gupta, D., Mahmoud, A., Elmagzoub, M. A., Sulaiman, A., Reshan, M. S. Al, Shaikh, A., & Juneja, S. (2023). Fault Prediction Recommender Model for IoT Enabled Sensors Based Workplace. Sustainability, 15(2), 1060. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Parra, J. C., Henao-Rodríguez, C., Lis-Gutiérrez, J. P., & Palomino-Gámez, S. (2024). Importance of University Students’ Perception of Adoption and Training in Artificial Intelligence Tools. Societies, 14(8), 141. [CrossRef]

- Viselli, L. (2021). Artificial Intelligence and Access to Justice: A New Frontier for Law Librarians. Canadian Law Library Review, 46(2).

- Wang, Y. Y., & Wang, Y. S. (2022). Development and validation of an artificial intelligence anxiety scale: an initial application in predicting motivated learning behavior. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(4), 619–634. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample Size Requirements for Structural Equation Models: An Evaluation of Power, Bias, and Solution Propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(6). [CrossRef]

- Wood, D., & Moss, S. H. (2024). Evaluating the impact of students’ generative AI use in educational contexts. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 17(2), 152–167. [CrossRef]

- Yang-Wallentin, F., Jöreskog, K. G., & Luo, H. (2010). Confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables with misspecified models. Structural Equation Modeling, 17(3). [CrossRef]

- Zakarneh, B. I., Aljabr, F., Al Said, N., & Jlassi, M. (2025). Assessing Pedagogical Strategies Integrating ChatGPT in English Language Teaching: A Structural Equation Modelling-Based Study. World Journal of English Language, 15(3), 364. [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., & Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education – where are the educators? In International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education (Vol. 16, Issue 1). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K., & Aslan, A. B. (2021). AI technologies for education: Recent research & future directions. In Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 2). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).