3.1. Device Structure of Van Der Waals Magnetic Tunnel Junction

Within the magnetic tunnel junction, graphene acts as both left and right metallic electrode layers, while 1T-VSe

2 serves as the ferromagnetic layer. By rotating the h-BN layer, we investigate the influence of barrier rotation on device performance. The 1T phase of VSe

2 is a magnetic transition metal dichalcogenide[

5]; the band structure for a single-layer, displayed in the

Figure 1 (b), corresponds with previous research [

26]. Its lattice parameter is a=b=3.44 Å [

2], while the h-BN barrier has a lattice constant of a=b=2.51 Å. Owing to the ability to grow monolayer 1T-VSe

2 on graphene or MoS

2 substrates via molecular beam epitaxy, we adopt single-layer graphene as the metal electrode layer adjacent to the VSe

2 layer. To avoid additional strain complications, only graphene’s lattice parameter is stretched to match that of VSe

2. The persistence of electronic states of graphene layers in the projected density of states diagrams of devices rotated 62.5° and 83.7° in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, close to the fermi level, verifies that strained graphene still retains its metallic nature. In our work, we rotationally manipulate the h-BN layer while maintaining the same stacking configuration between VSe

2 and the strained graphene layers across all devices to minimize varying parameters. No pinning layers are included in our MTJs; all devices are configured with a basic MTJ structure.

We fabricate 18 magnetic tunnel junction devices, controlling the h-BN layer’s rotation relative to the 1T-VSe

2 layer over a range of approximately 0° to 180° in increments of 10°, ensuring a lattice mismatch of less than 3% for all heterostructures. The lattice parameters for all constructed structures are displayed in

Table 1. For comparison purposes, we hold the 1T-VSe

2 and graphene layers at the same angles and positions while manipulating the orientation of the h-BN layer. Specifically, we highlight our rotation model with two examples, viz., graphene/1T-VSe

2/h-BN structures rotated at 62.5° and 83.7°.

In the top-down view of the 62.5° heterojunction depicted in

Figure 2 (a), equilateral green triangles identify a section of h-BN atoms. Equivalent h-BN atoms are framed by red equilateral triangles in the top-down view of the 83.7° stacking schematically illustrated in

Figure 2 (b). To facilitate comparison, we duplicate the same-angle green triangle from (a) onto (b) and align their centroids O, illustrating that in the 83.7° heterojunction, the h-BN layer is rotated counterclockwise by 21.2° relative to that in the 62.5° structure. Additional evidence is provided by the side views in

Figure 2 (c) and (d), revealing no relative rotation between the 1T-VSe

2 and graphene layers in either heterojunction, with the rotation confined solely to the h-BN layer.

Employing Atomistix ToolKit (ATK) software and DFT, we optimize the stable interlayer spacings within the devices, interlayer distances: 3.53 Å (graphene - graphene), 3.22 Å (graphene - VSe

2), and 3.48–3.54 Å (VSe

2 - h-BN, except 3.73 Å at 10.8°). These specific spacings can be found in

Table 1.

3.2. Electrical Properties of Rotating h-BN Layer in the Magnetic Van Der Waals Tunnel Junctions

We construct a Graphene/1T-VSe

2/h-BN/1T-VSe

2/Graphene MTJ configuration and subject it to an external magnetic field to manipulate the magnetic moments of the two ferromagnetic layers into either parallel spin alignment or antiparallel alignment. In the parallel spin configuration, the tunneling resistance significantly drops compared to the resistance when they are in the antiparallel state. The normalized difference between these two resistances defines the tunnel magnetoresistance ratio (TMR). Assuming spin conservation during tunneling, we employ the most optimal definition to describe TMR:

The conductivity can be calculated using the following formula:

GPC refers to the conductance of a MTJ with parallel spin orientation, while

GAPC represents the conductance with antiparallel alignment.

(

) and

(

) denotes the parallel (antiparallel) transmission coefficients for spin-up and spin-down electrons, respectively. Similarly, the TMR effect can also be described in terms of the device’s resistance according to equation “(3)”, which expresses the TMR ratio as:

Rpc and

Rapc represent the resistance in the spin-parallel and spin-antiparallel states, respectively. Based on the mentioned formula, to calculate the rotation effect of h-BN layers on the tunneling resistance and conductance of two-dimensional MTJs, we perform calculations of device transmission spectra at zero bias for MTJs with various h-BN layer rotational angles. A summary of parallel and antiparallel conductance values, along with their respective resistances and TMR, is compiled in

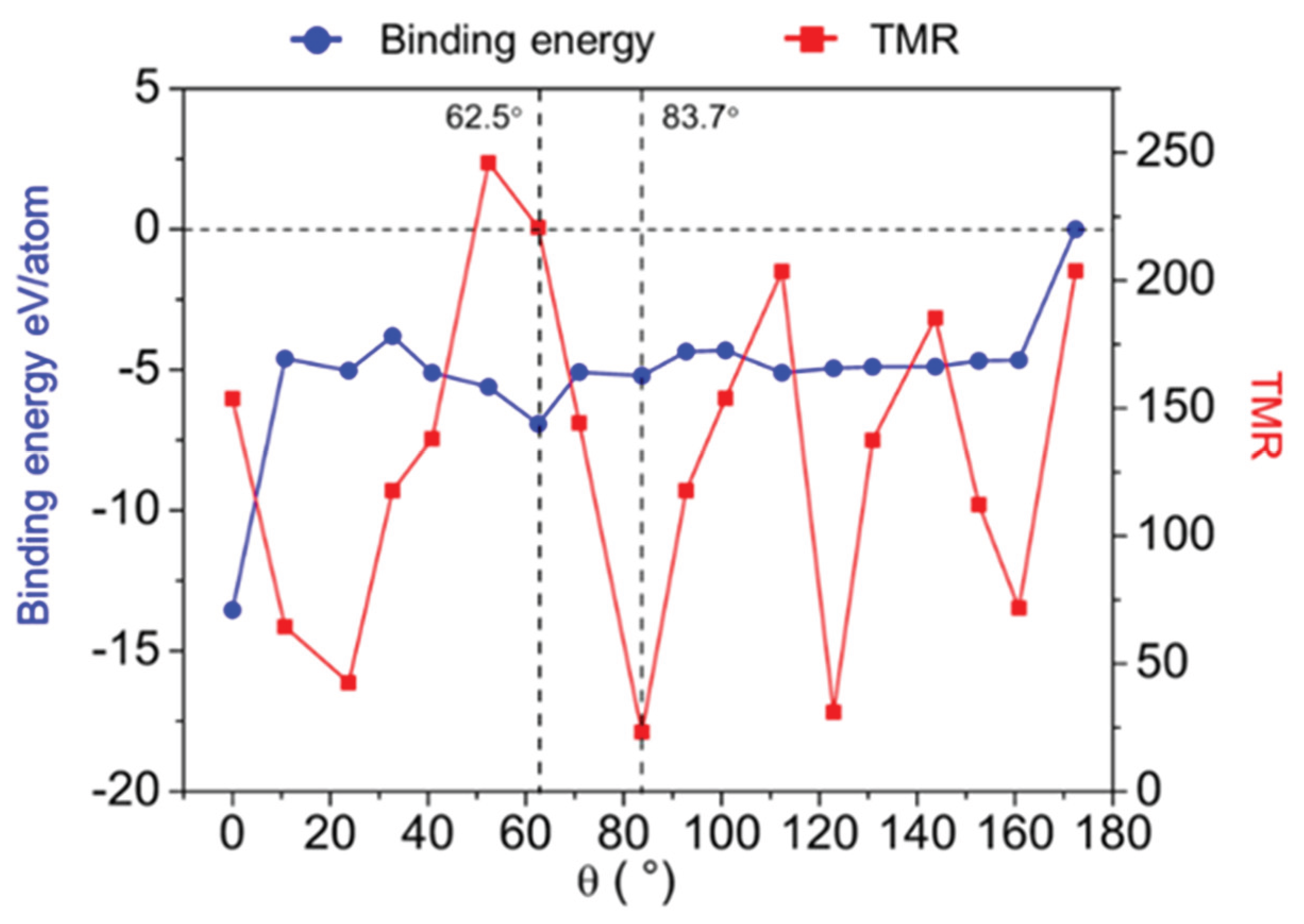

Table 1 for devices with different rotation angles. The red curve in

Figure 3 illustrates the variation of TMR with h-BN layer rotation, demonstrating a wide range from 2328% to 24680%. There is no evident pattern between the h-BN angular rotation within the devices and the distribution of TMR values. The device with the highest TMR performance corresponds to the one with a 52.4° rotation angle. Illustrated by the blue curve in

Figure 3, it presents the binding energy of each atom within the 1T-VSe

2/h-BN heterostructure for differently rotated devices. The formation energy

Eform within the interface of the heterojunction can be expressed as:

E (VSe

2/h-BN) represents the total energy after stacking of the 1T-VSe

2/h-BN structure, while

E (VSe

2) and

E (h-BN) denote the energies of a single-layer 1T-VSe

2 and h-BN, respectively, in a vacuum environment. Higher binding energy signifies increased instability of the rotational configuration. We set the 1T-VSe

2/h-BN binding energy of the most stable structure, at 172.4°, to 0 meV/atom, against which we gauge the binding energies of other h-BN rotation structures.

Our calculated interface binding energies for the various rotation angles of the 1T-VSe

2/h-BN heterostructures showed in

Figure 3, mainly cluster between -3.8 meV/atom and -6.9 meV/atom, suggesting that appreciable bonding interaction exists between 1T-VSe

2 and h-BN layers across these angles. Specifically, the 0° structure has the lowest interface binding energy of -13.5 meV/atom. While overcoming an interface binding energy difference of 8.9 meV/atom is required for h-BN to rotate from 0° to 10.8°, and a shift from 160.8° to 172.4° involves overcoming 4.7 meV/atom, the clockwise rotation of h-BN from 10.8° to 160.8° is relatively facile. Considering the experimentally observed 52.4° structure with the highest TMR is prone to slide to the 62.5° structure with lower local interface binding energy, indicated by a black dashed line in

Figure 3, we highlight the interface binding energy and TMR characteristics of these two devices (62.5° with the second-highest TMR and 83.7° with the lowest TMR) for more profound investigations into the interplay between electric and magnetic properties due to h-BN layer rotations.

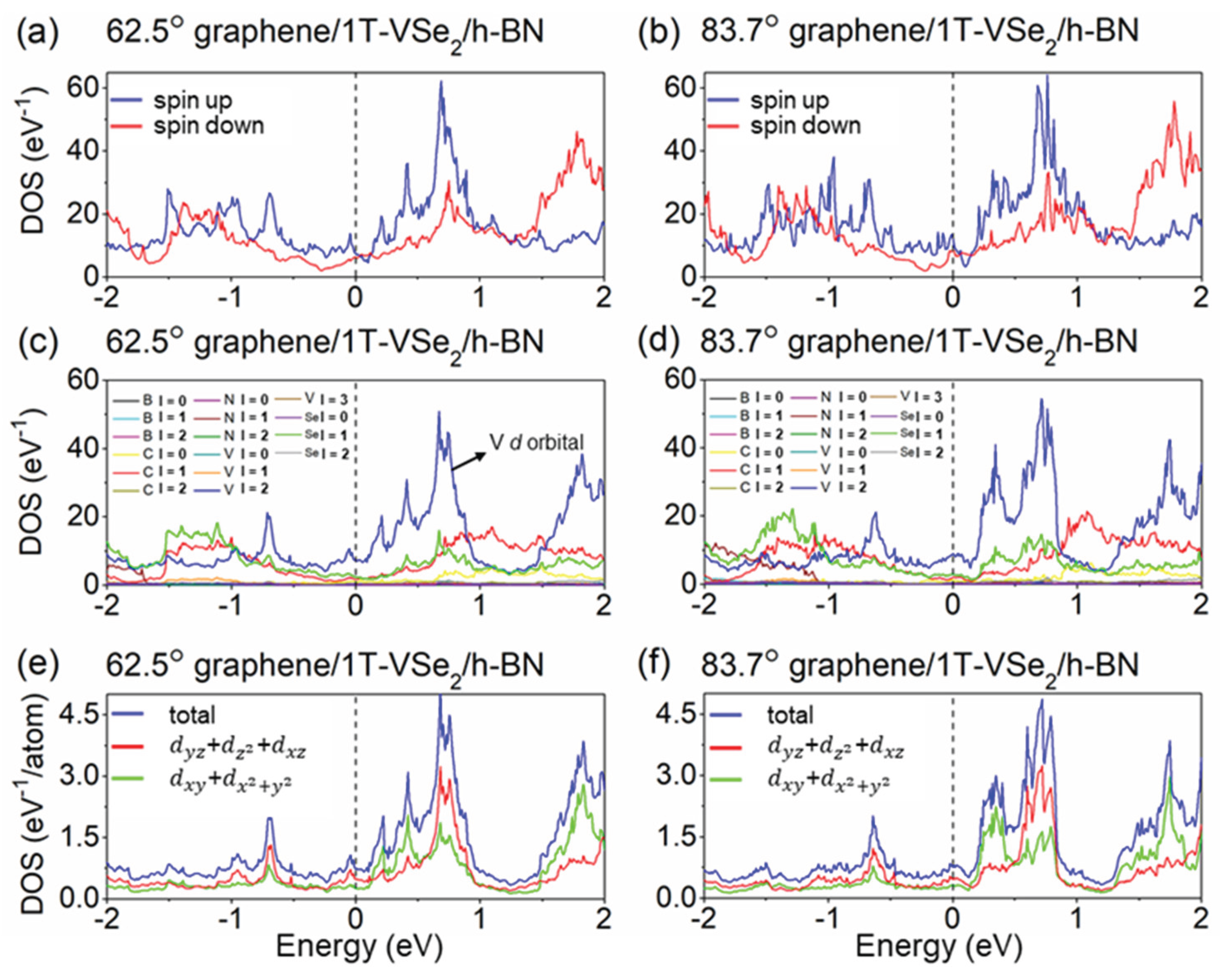

We proceed in

Figure 4 (a) and (b) to investigate the PDOS for the spin-up and spin-down channels of graphene/1T-VSe

2/h-BN heterostructures at 62.5° and 83.7° after the rotation of h-BN. A distinct contrast in the electronic states near the fermi level and other peaks in PDOS profiles for both heterostructures’ spin-up and spin-down channels is observed. It is well-known that magnetic properties in the heterostructure are predominantly due to the presence of unpaired electrons in V atoms’

d orbitals. The differences in PDOS peak distributions between the spin-up and spin-down channels suggest that rotation of the h-BN layer influences the magnetization direction within the 1T-VSe

2 layer, thereby affecting electron states for the two spins. Moreover, the imbalance of spin-up and spin-down channel DOS in each heterostructure further indicates a spin polarization phenomenon within the 1T-VSe

2 layer that depends on the overall system.

Moving forward, in

Figure 4 (c) and (d), we analyze the distribution of angular momentum quantum number l for distinct elements’ orbital in the two rotated heterostructures. The third atomic d-orbitals of the V atom in the 1T-VSe

2 layer contribute significantly to the PDOS compared to other elements or other V orbitals at the fermi level. Hence, we depict the projected DOS for individual V atom d-orbitals of the 62.5° and 83.7° heterostructures, as schematically illustrated in

Figure 4 (e) and (f). Notably, both V atoms exhibit similar d-orbital DOS distributions, with two groups: the out-of-plane

+

+

orbitals and in-plane

+

orbitals [

3]. Analyzing the fermi-level changes in V atom d-orbital states for the two angles, the DOS values for out-of-plane and in-plane d orbitals for the 62.5° structure are 0.47 eV

-1/atom and 0.25 eV

-1/atom, whereas for the 83.7° structure, they are 0.46 eV

-1/atom and 0.29 eV

-1/atom. Despite modest differences in these plane states at the fermi level, there is a noticeable peak difference (62.5°: 0.72 eV

-1/atom vs. 83.7°: 0.38 eV

-1/atom at E = -0.04 eV) in out-of-plane DOS just above the fermi level with much less variation in the in-plane orientation (within 0.09 eV

-1/atom). These contrasting features may account for the influence on TMR for the two devices with distinct rotations.

Further, we utilize spin-resolved local density of states (LDOS) maps for the 62.5° (

Figure 5) and 83.7° (

Figure 6) devices to scrutinize the change in energy bands within the devices. Focusing on the central region’s LDOS images (neglecting those from the graphene electrodes) and highlighting the location of different material layers in

Figure 5(a), it is confirmed that graphene’s gap at the fermi level remains at 0 eV, preserving its metallic nature, while the h-BN layers retain insulating characteristics. Rotation of the h-BN layer alters the fermi-level spin-up and spin-down channels of 1T-VSe

2 and influences interface state distribution between the two, leading to dissimilar behavior between the devices.

Figure 5.

The local density of states (LDOS) maps are illustrated for van der Waals magnetic tunnel junction devices under hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) rotation. (a) shows the spin-up channel configuration for an h-BN rotation of 62.5°in a parallel spin geometry. (b) depicts the spin-down channel configuration under the same 62.5°h-BN rotation, also in a parallel spin geometry. (c) presents the spin-up channel configuration but in an antiparallel spin geometry with the 62.5°h-BN rotation. (d) represents the spin-down channel configuration within the antiparallel spin geometry at 62.5°h-BN rotation.

Figure 5.

The local density of states (LDOS) maps are illustrated for van der Waals magnetic tunnel junction devices under hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) rotation. (a) shows the spin-up channel configuration for an h-BN rotation of 62.5°in a parallel spin geometry. (b) depicts the spin-down channel configuration under the same 62.5°h-BN rotation, also in a parallel spin geometry. (c) presents the spin-up channel configuration but in an antiparallel spin geometry with the 62.5°h-BN rotation. (d) represents the spin-down channel configuration within the antiparallel spin geometry at 62.5°h-BN rotation.

Figure 6.

The local density of states (LDOS) maps for van der Waals magnetic tunnel junction devices under hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) rotation are presented. (a) displays the spin-up channel configuration for an h-BN rotation of 83.7°in a parallel spin geometry. (b) illustrates the spin-down channel configuration under the same 83.7°h-BN rotation, also in a parallel spin geometry. (c) showcases the spin-up channel configuration but in an antiparallel spin geometry with the 83.7°h-BN rotation. (d) represents the spin-down channel configuration within the antiparallel spin geometry at 83.7°h-BN rotation.

Figure 6.

The local density of states (LDOS) maps for van der Waals magnetic tunnel junction devices under hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) rotation are presented. (a) displays the spin-up channel configuration for an h-BN rotation of 83.7°in a parallel spin geometry. (b) illustrates the spin-down channel configuration under the same 83.7°h-BN rotation, also in a parallel spin geometry. (c) showcases the spin-up channel configuration but in an antiparallel spin geometry with the 83.7°h-BN rotation. (d) represents the spin-down channel configuration within the antiparallel spin geometry at 83.7°h-BN rotation.

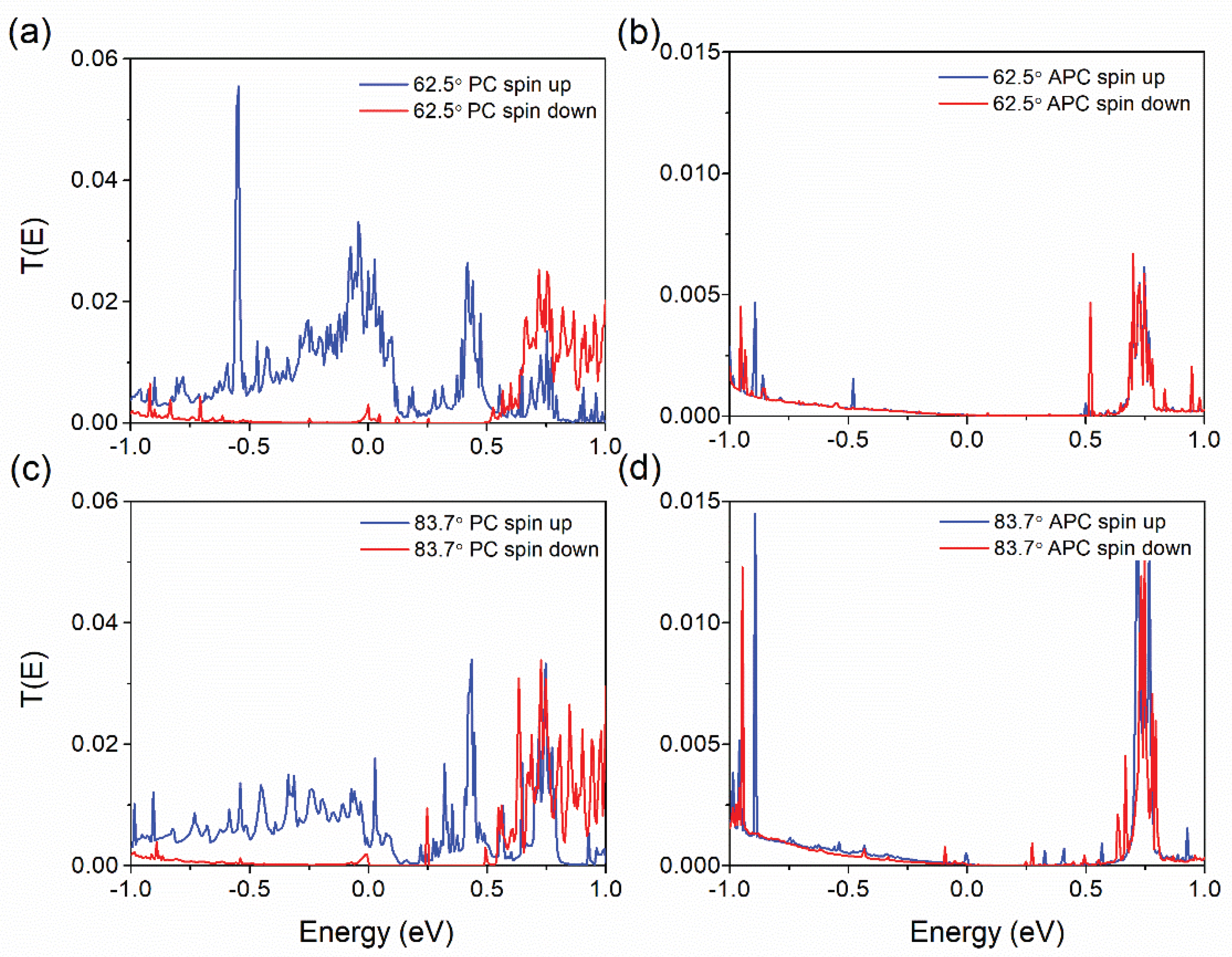

Figure 7 (a) and (b) present spin-resolved transmission spectra for MTJ with spin parallel and antiparallel configurations in h-BN devices with a rotation angle of 62.5°. Similarly

Figure 7 (c) and (d) illustrate the spin-resolved transmission spectra for those with a rotation angle of 83.7° in both parallel and antiparallel arrangements. In the parallel configuration, a pronounced contrast in transmission coefficients near the fermi level is observed between the upward spin channel for 62.5° devices (0.025) and 83.7° devices (approximately 0.0033). Downward spin channel transmissions for these angles exhibit comparably low values, specifically 0.003 for 62.5° devices and 4.21E-04 for the 83.7° devices. Under antiparallel configurations, both angle-rotated devices exhibit negligible transmission coefficients for both upward and downward spins, ranging from 3.87×1E-05 to 4.21×1E-04. Calculating spin polarization using the formula η = (

T↑(E

f) -

T↓(E

f)) / (

T↑(E

f) +

T↓(E

f)), where

T↑(E

f) and

T↓(E

f) represent the transmission coefficients for the spin-up and spin-down channels at the fermi energy level, yields a spin polarization rate of 78.18% for the 62.5° device’s parallel configuration and 77.66% for the 83.7° device’s counterpart. These results indicate that the 62.5° rotated device facilitates effective spin injection in its parallel configuration, while spin injection of the Bloch states in the 83.7° device is relatively more challenging than in the 62.5° device. Conclusively, it can be inferred that the rotation of h-BN layers influences the device’s transmission characteristics, with variations also evident through the change in TMR values.

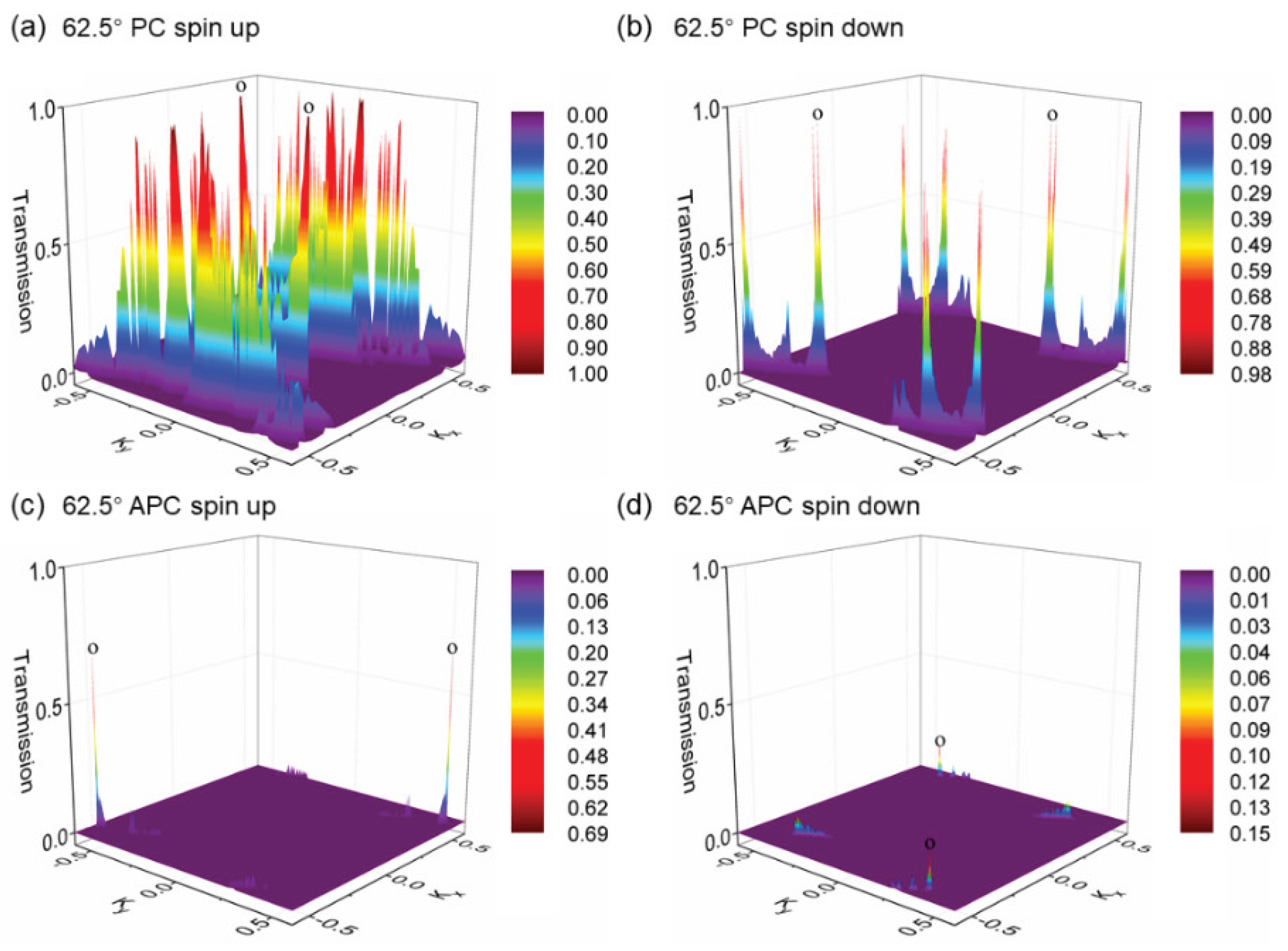

Next, for a more meticulous understanding of the magnetic tunnel junction’s fermi-level transmission spectrum, we present

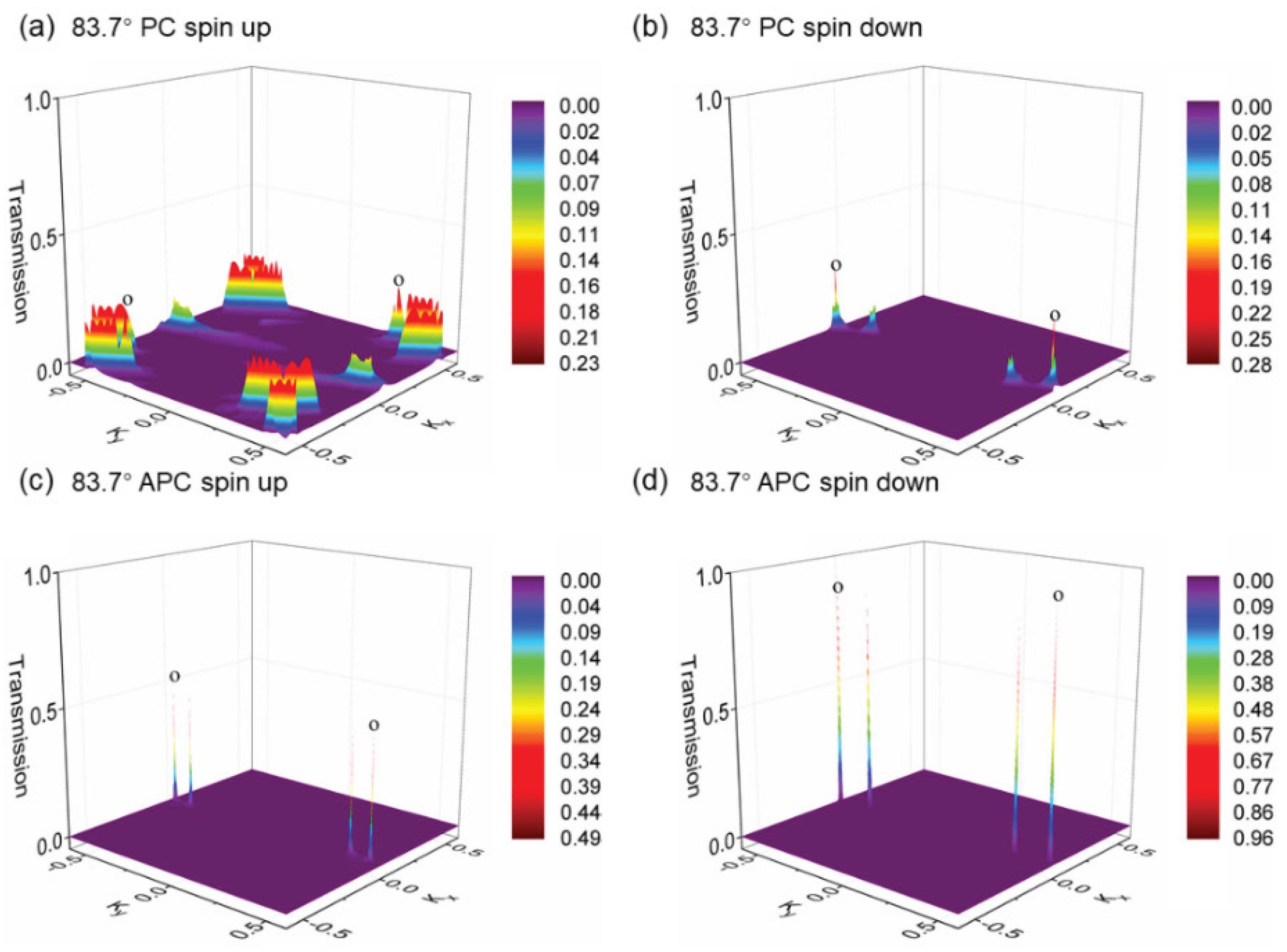

Figure 8 showing the k-resolved and spin-resolved transmission eigenvalue distribution in the vicinity of the fermi surface for the 62.5° device. In the parallel spin configuration for the 62.5° rotation device, the spin-up channel exhibits high transmission eigenvalues in regions distant from the center of the two-dimensional brillouin zone (BZ), indicating prominent interface states. Due to the larger distance from the Γ point, there is a higher decay coefficient, suggesting that increasing the number of h-BN layers would be disadvantageous to transmission. Conversely, for the spin-down channel, the interface state eigenvalues are significantly lower. In the anti-parallel spin configuration, the eigenvalue distributions for the spin-up and spin-down channels are comparable, predominantly located around and at the Γ point; however, their eigenvalues are substantially weaker compared to the hotspots of the spin-up channel in the parallel configuration at point o.

In

Figure 9, we demonstrate the spin-resolved and k-resolved transmission eigenvalue distributions of the fermi level near the two-dimensional BZ for the 83.7° rotated h-BN device for both parallel and antiparallel alignments. The

Figure 9 (a) reveals that the spin-up channel of the parallel spin configuration displays interface states significantly lower than those in the parallel spin-up channel of the 62.5° device, at an even greater distance from the Γ point, implying a higher attenuation factor. Furthermore, the interface states for the 83.7° device in both parallel spin-up and anti-parallel configurations appear particularly sparse.

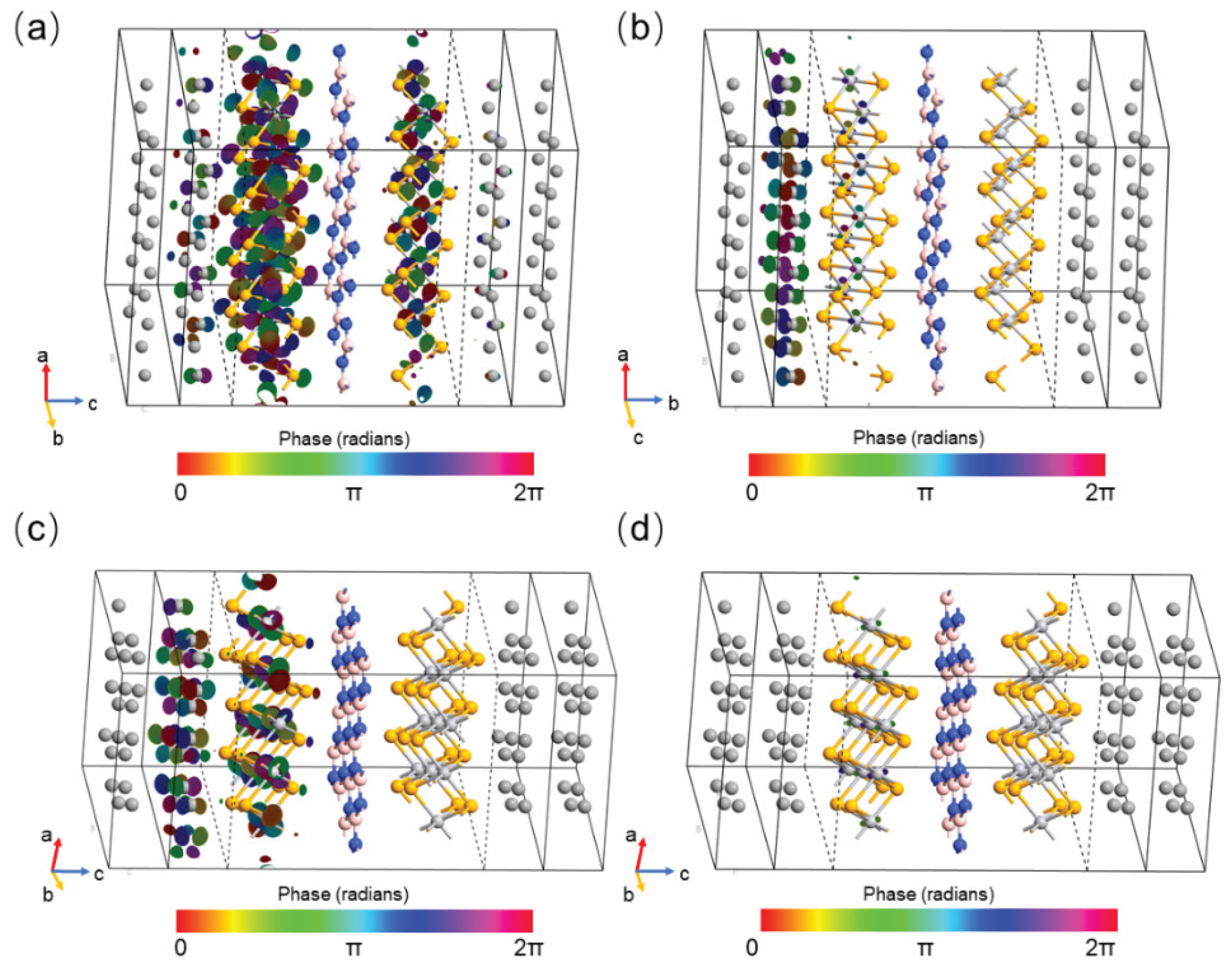

We proceed by plotting the transmission spectrum eigenfunctions distribution at the hotspots o in the two-dimensional BZ for the 62.5° device with the parallel spin-up channel (a) and the spin-down channel (b), and for the 83.7° device with the parallel spin-up channel (c) and the spin-down channel (d), as depicted in

Figure 10. Clearly, from

Figure 10 (a), the Bloch states of the parallel spin-up channel in the 62.5° rotation device can penetrate the h-BN barrier to reach the 1T-VSe

2 layer on the right. On the other hand, it is evident in

Figure 10 (b) that the bloch states of the parallel spin-up channel in the 83.7° device have great difficulty in traversing the h-BN barrier. As schematically illustrated in

Figure 10 (c) and (d), for the parallel spin-down channels in both configurations, the eigenfunctions barely extend to the 1T-VSe

2 layer situated on the opposite side of the h-BN blocking layer. Regarding the antiparallel configurations with their lower eigenvalues, the Bloch states in the devices experience even greater difficulty in crossing the h-BN barrier, leading to comparably low fermi surface transmission rates. The contrasting distribution of the transmission eigenstates in the parallel spin-up channels between these two devices implies that the 62.5° device has a smaller attenuation coefficient and hence permits easier passage of the Bloch states through the h-BN layer, which results in the significant difference in TMR values owing to the distinct magnetic resistances in each device.

Considering the outcome of our computational process, it becomes apparent that the rotation of the h-BN layer leads to dramatic changes in TMR. We selected the 62.5° and 83.7° devices, with comparable stable h-BN/1T-VSe2 binding energies and significant TMR disparities, for detailed analysis. First, we observe that the electronic state density of the valence d orbitals of V atoms in all the elements’ orbitals within the graphene/1T-VSe2/h-BN heterostructure carries the highest weight. This is because the presence of unpaired electrons in the d orbital layer endows the 1T-VSe2 monolayer with its magnetic property. As the h-BN layer rotates, a distinct peak emerges in the planar-state density of the ++ orbitals at an energy of -0.04 eV for the 62.5° heterojunction compared to that of the 83.7° junction, potentially impacting transmission at the fermi level for the two devices. Furthermore, the local density of states (LDOS) for the spin-up and spin-down channels at the two different rotation angles of 1T-VSe2 show distinct characteristics at the fermi energy.