1. Introduction

The convergence of digital transformation, artificial intelligence, and inclusive education represents one of the most significant developments in contemporary education. These intersecting forces are reshaping access, engagement, and outcomes for diverse learners, presenting both extraordinary potential and substantial challenges. This research investigates their dynamic interplay, examining how they collectively impact educational equity while identifying implementation barriers and strategies for overcoming them.

For clarity, this analysis employs the following operational definitions:

Digital transformation refers to the fundamental redesign of educational processes, models, and experiences through technology integration, moving beyond digitization toward systemic change (Castañeda & Selwyn, 2024).

Artificial intelligence in education encompasses computational systems that perform tasks requiring human-like intelligence, including natural language processing, machine learning, and predictive analytics, specifically applied to learning contexts (Holmes et al., 2023).

Inclusive education constitutes approaches that identify and remove barriers to participation and achievement for all learners, particularly those vulnerable to marginalization or exclusion (Ainscow, 2023).

This study addresses three central research questions:

How do digital transformation and AI technologies influence accessibility and equity in educational environments?

What implementation challenges emerge at the intersection of these domains?

What evidence-based strategies can educational leaders employ to harness these technologies for more inclusive outcomes?

These questions address critical gaps in existing literature, which has primarily examined these domains in isolation rather than their complex interaction. While previous research has documented the potential of educational technologies for expanding access (Warschauer, 2023) and the principles of inclusive design (Meyer et al., 2023), limited empirical evidence exists regarding how these domains function in real-world educational contexts across diverse institutions and populations.

The study's key findings reveal that while technology implementations can significantly enhance educational equity, these outcomes depend heavily on specific implementation patterns rather than the technologies themselves. Statistical analyses demonstrate that intentional design, comprehensive integration, continuous evaluation, stakeholder participation, and balanced innovation-support frameworks collectively explain 63% of variance in equity outcomes. Additionally, the research identifies substantial implementation barriers, with digital divides and professional development gaps affecting rural and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations most severely. These findings contribute to both theoretical understanding of educational technology integration and practical guidance for educational leaders seeking to advance equity through technological innovation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Transformation in Education

Digital transformation in education extends far beyond adding technology to classrooms, representing a fundamental reimagining of educational processes and structures. Williamson and Eynon (2022) documented how this transformation reshapes not just tools but institutional structures, pedagogical approaches, and educational purposes. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this process dramatically, with OECD research (2024) demonstrating how institutions compressed what would have been a decade of digital evolution into roughly 18 months.

Previous research has identified tensions between digital transformation's potential to expand access and its risk of reinforcing existing inequalities. Reich (2023) characterized this as the "innovation-equality dilemma," documenting how educational innovations often disproportionately benefit already-advantaged students unless explicitly designed with equity as a central principle. Similarly, Warschauer (2023) proposed a "digital equity impact assessment" framework for evaluating how technology initiatives affect different populations.

These critical perspectives highlight the need to examine digital transformation not as a technologically deterministic process but as a complex sociotechnical phenomenon shaped by institutional structures, power dynamics, and implementation approaches. However, most existing studies focus on single institutions or specific technologies rather than examining broader patterns across diverse contexts.

2.2. AI in Education

Artificial intelligence applications in education have evolved from basic automation tools to sophisticated systems enabling personalization, accessibility, and predictive intervention. A systematic review by Holmes et al. (2023) categorized educational AI applications into five domains: administrative systems, assessment tools, intelligent tutoring systems, accessibility supports, and educational robotics.

Critical perspectives have highlighted ethical concerns regarding AI implementation. Baker and Hawn (2024) documented patterns of "algorithmic inequality" where AI systems perpetuate or amplify existing biases when not designed with explicit attention to diversity. Their expanded 2024 study demonstrated how these inequalities manifest across different demographic groups and institutional contexts. Shen and Holstein (2024) identified significant gaps between ethical principles and practical implementation, with their survey finding that while 87% of educational technology decision-makers expressed concern about algorithmic bias, only 23% reported using formal evaluation frameworks.

The literature reveals a significant gap between AI's theoretical potential for personalization and its actual implementation in diverse educational settings. While laboratory studies demonstrate promising capabilities, real-world implementation research remains limited, particularly regarding equity impacts across different student populations and institutional contexts.

2.3. Inclusive Education

Inclusive education has evolved from specialized approaches for students with disabilities to comprehensive frameworks ensuring equitable opportunities for all learners. Ainscow (2023) demonstrated how inclusive approaches benefit not just marginalized students but entire learning communities through enhanced pedagogical practices, collaborative structures, and innovative problem-solving.

In digital contexts, inclusion encompasses physical access, digital access, meaningful participation, and successful outcomes. Robinson et al. (2024) proposed a multidimensional digital inclusion framework incorporating device access, connectivity, digital literacy, digital design, and community support elements. Meanwhile, Joshi et al. (2023) highlighted cultural and linguistic dimensions of digital inclusion, emphasizing the importance of approaches that value diverse knowledge systems and linguistic traditions.

While Universal Design for Learning (UDL) has emerged as a prominent framework for inclusive digital education, Edyburn (2023) has raised important critiques regarding implementation challenges, noting that UDL principles are often superficially applied without the fundamental redesign of educational experiences necessary for meaningful inclusion. This critique highlights the need for more rigorous examination of how inclusive education principles are operationalized in digital contexts.

2.4. Gaps in Current Research

While existing literature provides valuable insights into each domain individually, significant gaps remain in understanding their intersection. Previous research has largely focused on single technologies or contexts rather than examining systemic interactions. Additionally, most studies emphasize theoretical frameworks or institutional perspectives with limited attention to diverse stakeholder experiences and implementation challenges.

Three specific gaps are particularly noteworthy:

Limited empirical evidence on implementation patterns: While theoretical frameworks abound, few studies empirically examine how different implementation approaches influence equity outcomes across diverse contexts.

Insufficient attention to contextual factors: Existing research often fails to account for how institutional characteristics, governance structures, funding models, and policy environments shape technology implementation and equity outcomes.

Inadequate representation of diverse stakeholder perspectives: Most studies prioritize institutional or researcher perspectives, with limited incorporation of student, family, and community voices, particularly from marginalized populations.

This study addresses these gaps through a mixed-methods approach examining the complex interplay among these domains across multiple contexts while centering diverse stakeholder perspectives.

3. Theoretical Framework: The Education Equity Technology (EET) Model

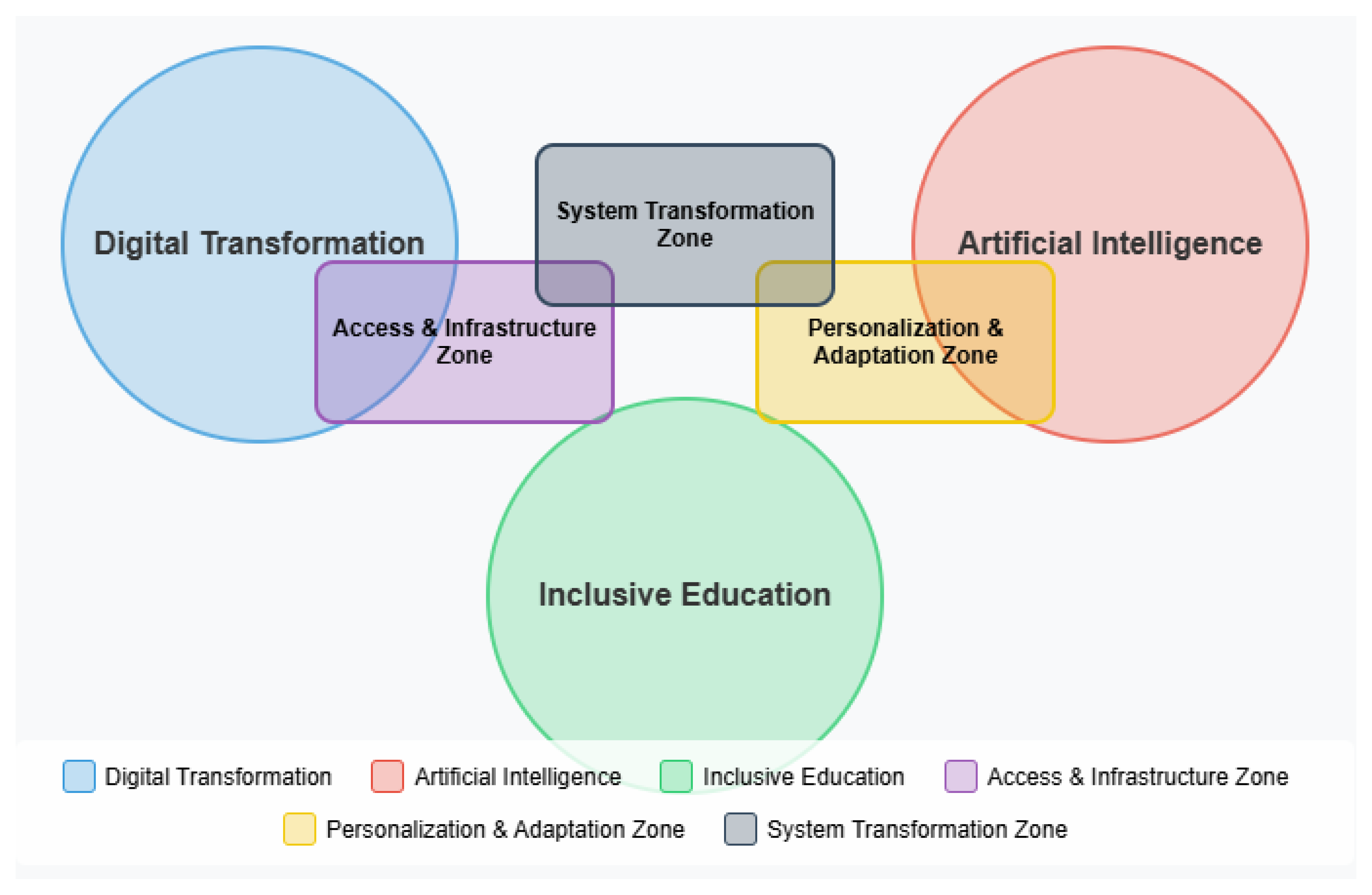

To conceptualize the interrelationships among digital transformation, AI, and inclusive education, this study proposes the Education Equity Technology (EET) model (

Figure 1).

This framework identifies three critical interaction zones where these domains converge:

Access and Infrastructure Zone: Where digital transformation initiatives intersect with inclusive education principles to address physical, digital, and cognitive access barriers.

Personalization and Adaptation Zone: Where AI capabilities intersect with inclusive education approaches to create responsive learning experiences tailored to diverse needs.

System Transformation Zone: Where digital transformation converges with AI capabilities to enable fundamental redesign of educational structures and processes with equity implications.

Each zone presents distinct opportunities and challenges for advancing educational equity. This framework guided data collection and analysis throughout the research process.

The EET model builds upon and extends existing theoretical perspectives in several ways. First, it integrates sociotechnical systems theory (Orlikowski, 2022) by conceptualizing educational technology implementations as complex interactions between technological capabilities, human actors, organizational structures, and social contexts. Second, it incorporates critical perspectives on technology from science and technology studies (Selwyn & Facer, 2023) by examining how power dynamics and institutional structures shape technology adoption and configuration. Finally, it draws from implementation science (Damschroder et al., 2024) by focusing on the processes and conditions that influence how technologies are integrated into educational practices.

The model's three interaction zones provide analytical categories for examining how these theoretical dimensions manifest in practice, allowing for systematic analysis of both opportunities and challenges in each zone. This framework guided both data collection and analysis throughout the research process.

[Note:

Figure 1 would be included here in the published article, showing a visual representation of the EET model with overlapping circles representing each domain and the interaction zones where they intersect.]

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

This study employed a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design (Creswell & Creswell, 2023) involving three phases: (1) systematic literature review, (2) quantitative survey, and (3) qualitative interviews. This approach allowed for comprehensive examination of the research questions through methodological triangulation, with quantitative data providing breadth of understanding across diverse contexts and qualitative data offering depth of insight into implementation processes and stakeholder experiences.

4.2. Phase 1: Systematic Literature Review

The systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2023) to identify and synthesize existing research on the intersection of digital transformation, AI, and inclusive education. The researcher searched five major databases (ERIC, Web of Science, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and ACM Digital Library) using combinations of key terms related to the three domains. Initial searches yielded 1,834 potential sources, which were narrowed to 142 studies meeting inclusion criteria following title/abstract screening and full-text review.

Inclusion criteria required that studies: (1) addressed at least two of the three domains under investigation; (2) were published between 2018-2024; (3) were peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, or high-quality institutional reports; and (4) included empirical data or systematic theoretical analysis. Included studies were analyzed using qualitative content analysis with NVivo 14 software, with coding focused on implementation approaches, contextual factors, reported outcomes, and identified challenges.

4.3. Phase 2: Quantitative Survey

4.3.1. Instrument Development and Validation

Building on insights from the literature review, a 52-item survey instrument was developed measuring experiences, attitudes, and practices related to technology implementation and inclusion. The instrument development process involved multiple stages:

Item generation based on literature review findings

Expert panel review by seven specialists in educational technology, inclusive education, and survey methodology

Cognitive interviews with five educational practitioners to assess item clarity and interpretation

Pilot testing with 25 educational professionals

Refinement based on pilot feedback and preliminary reliability analysis

The final instrument demonstrated strong reliability with Cronbach's alpha values ranging from 0.78 to 0.92 across subscales. Construct validity was established through confirmatory factor analysis, with all items loading on intended factors at >0.60.

For measuring equity outcomes specifically, the instrument included a composite measure comprising six dimensions: (1) academic achievement gaps, (2) participation rates, (3) student engagement, (4) self-efficacy development, (5) accessibility ratings, and (6) student satisfaction. These dimensions were measured through 5-point Likert scale items and combined into an overall equity outcomes index with strong internal consistency (α=0.88).

4.3.2. Sampling and Administration

The survey was distributed to educational practitioners across K-12 and higher education settings using stratified random sampling. Institutional sampling frames were developed using national education databases, with stratification by institution type, size, and region. Within selected institutions, participants were randomly selected from staff directories, with oversampling of technology specialists and inclusion coordinators to ensure adequate representation of these perspectives.

The survey was administered online using Qualtrics XM platform between September and November 2024. Multiple follow-up reminders were sent to maximize response rates. A total of 412 complete responses were received (61% response rate), representing diverse roles, institution types, and geographical regions. Respondent demographics are summarized in

Table 1.

4.3.3. Statistical Analysis

Survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and multiple regression using SPSS 28.0 software. Prior to analysis, data were screened for missing values, outliers, and assumption violations. Missing values (<3% of data points) were addressed using multiple imputation. All regression analyses were tested for assumptions of normality (Shapiro-Wilk tests), homoscedasticity (Breusch-Pagan tests), and multicollinearity (Variance Inflation Factors). All assumptions were met, with VIF values ranging from 1.14 to 2.37, well below the problematic threshold of 5.0.

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for continuous variables after confirming normal distributions. For non-normally distributed variables, Spearman's rank correlation coefficients were used. Statistical significance was set at p<.05, with Bonferroni corrections applied for multiple comparisons.

4.4. Phase 3: Qualitative Interviews

4.4.1. Participant Selection

To deepen understanding of survey findings, 37 semi-structured interviews were conducted with diverse stakeholders including:

Educational practitioners (n=14)

Students with diverse learning needs (n=8)

Parents/caregivers (n=5)

Technology developers (n=6)

Policy experts (n=4)

Participants were selected using maximum variation sampling to ensure diverse perspectives across roles, contexts, and experiences. Selection criteria included representation across institution types, geographical regions, technology implementation levels, and demographic characteristics. For student participants, purposive sampling ensured inclusion of individuals with disabilities, language differences, varied socioeconomic backgrounds, and diverse cultural contexts.

4.4.2. Interview Procedures

Interviews were conducted using semi-structured protocols tailored to each stakeholder group (see

Appendix B). Protocols were developed based on survey findings and refined through pilot interviews. All protocols addressed the core research questions while adapting language and specific topics to each stakeholder group's perspective and experience.

Interviews lasted 45-60 minutes and were conducted via video conference or in person based on participant preference and location. All interviews were audio-recorded with participant consent. For participants with disabilities, accessibility accommodations were provided as needed, including sign language interpretation, real-time captioning, and alternative question formats.

4.4.3. Qualitative Analysis

Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2022) with NVivo 14 software. The analysis process involved:

Familiarization with data through repeated reading of transcripts

Initial open coding of meaningful segments

Development of a coding framework based on emerging patterns

Systematic coding of all transcripts using the framework

Identification of themes and subthemes through pattern analysis

Review and refinement of themes

Integration with quantitative findings

Initial coding was conducted independently by two researchers with an inter-rater reliability of 0.87 (Cohen's kappa). Coding discrepancies were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. Thematic saturation was confirmed when no new significant codes emerged from the final five interviews.

4.5. Integration and Analysis

Findings from all three phases were integrated using joint displays (Guetterman et al., 2023) to identify convergent and divergent patterns. This approach involved creating matrices that juxtaposed quantitative results with qualitative themes, allowing for systematic comparison and integration.

Integration occurred at multiple levels:

Design level: Qualitative protocols were informed by preliminary survey findings

Analysis level: Qualitative themes were compared with statistical patterns

Interpretation level: Conclusions drew on both data sources to develop comprehensive understanding

This integrated analysis formed the basis for developing the Education Equity Technology (EET) model and identifying key implementation patterns influencing equity outcomes.

4.6. Ethical Considerations

The study received approval from the institutional review board at [University name] (Protocol #IRB-2024-0157). All participants provided informed consent, with specialized consent procedures for vulnerable populations. Student participants under 18 received parental consent and provided assent. Special attention was given to inclusive research practices, including providing accessible formats for all materials and ensuring diverse representation across participant groups.

Data were stored on encrypted servers with personally identifiable information separated from responses. All reporting uses pseudonyms and removes potentially identifying details to protect participant confidentiality.

4.7. Limitations and Validity Considerations

Several methodological limitations should be acknowledged. First, while the sample includes diverse contexts, representation from Global South regions (combined 15% from Africa and South America) is lower than desired, potentially limiting applicability of findings to these contexts. Second, the voluntary nature of participation may have attracted respondents with stronger interest in educational technology, potentially introducing selection bias. Third, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference and understanding of how implementations evolve over time.

To enhance validity despite these limitations, several strategies were employed:

Methodological triangulation across multiple data sources

Member checking of qualitative themes with selected participants

Peer debriefing with researchers not involved in data collection

Thick description of contexts to support transferability judgments

Systematic search for disconfirming evidence and alternative explanations

These approaches strengthen confidence in findings while acknowledging the inherent limitations of the research design.

5. Results

5.1. Current State of Implementation

Survey results revealed considerable variation in the implementation of digital transformation and AI technologies across educational contexts (

Table 2). Overall, respondents reported moderate levels of digital transformation (M=3.42, SD=0.87 on a 5-point scale) and lower levels of AI implementation (M=2.86, SD=1.12). Notably, only 37% of respondents reported having formal inclusion guidelines for technology implementation.

Multiple regression analysis identified significant predictors of inclusive technology implementation (R²=0.63, F(6,405)=114.8, p<.001). The strongest predictors included institutional commitment to inclusion (β=0.42, p<.001), professional development resources (β=0.38, p<.001), and stakeholder involvement in decision-making (β=0.35, p<.001). Institutional size and funding levels, while significant, had smaller effects (β=0.15 and β=0.18 respectively, both p<.05), suggesting that organizational practices may be more influential than resource levels alone.

When analyzing implementation by institutional context variables, several patterns emerged. Public institutions reported greater challenges with resource constraints and digital divides, while private institutions more often cited governance and policy barriers. Urban institutions reported higher AI implementation levels than rural institutions (M=3.12 vs. M=2.31, t(284)=7.43, p<.001), reflecting both resource differences and connectivity challenges. These patterns highlight the importance of contextual factors in shaping implementation approaches and challenges.

Historical implementation timelines also influenced current patterns. Institutions with longer technology implementation histories (>5 years) reported more comprehensive integration approaches (r=0.37, p<.001) and were more likely to have formal inclusion guidelines (χ²=12.48, p<.001). This suggests that implementation maturity contributes to more developed equity practices, emphasizing the importance of longitudinal perspectives when evaluating implementation quality.

5.2. Key Implementation Patterns

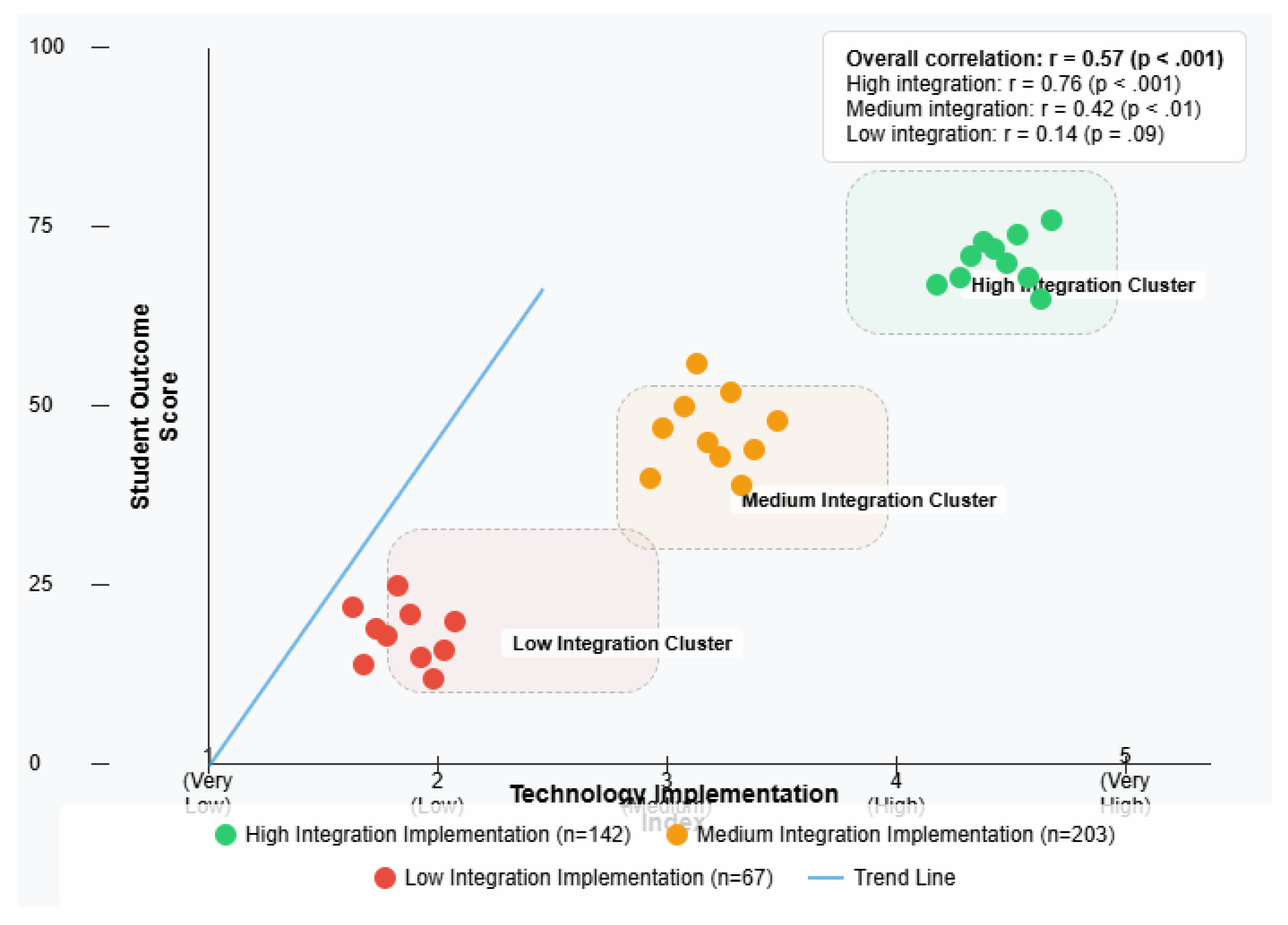

Integrated analysis of survey and interview data identified five key implementation patterns that significantly influenced equity outcomes, as visualized in

Figure 2. These patterns collectively explained a substantial portion of variance in reported equity outcomes across institutional contexts.

5.2.1. Intentional Design Approaches

Organizations demonstrating the most equitable outcomes reported explicit design processes centered on inclusion. Survey respondents who reported using formal accessibility guidelines were significantly more likely to report positive equity outcomes (r=0.52, p<.001). Interview data revealed specific practices within this pattern:

"We completely redesigned our procurement process to require vendors to demonstrate how their products serve diverse learners—not just checking compliance boxes but showing actual evidence of accessibility testing with diverse users." (Technology specialist, higher education)

This intentional design pattern manifested differently across institutional contexts. Higher education institutions more frequently employed formal accessibility standards and testing protocols, while K-12 settings more often utilized collaborative design approaches involving teachers and specialists. Both approaches were associated with better equity outcomes compared to institutions without intentional design processes (F(2,409)=28.56, p<.001).

The temporal dimension of intentional design emerged as important in qualitative data. Institutions that incorporated inclusion considerations from the initial planning stages reported fewer implementation challenges than those attempting to address accessibility after selecting technologies:

"When we tried to retrofit accessibility into our first LMS, it was expensive and never worked well. With our current system, we made accessibility a non-negotiable requirement from the very beginning of the procurement process." (Administrator, community college)

"Our district's first digital curriculum adoption didn't consider English learners until after implementation. We had to create workarounds and supplemental materials. For our most recent adoption, we had bilingual teachers and ELL specialists involved in setting requirements from day one, and the difference in implementation quality was dramatic." (District curriculum coordinator)

5.2.2. Comprehensive Integration Strategies

Successful implementations addressed technical, pedagogical, cultural, and structural dimensions simultaneously. Survey analysis revealed that organizations implementing changes across multiple dimensions reported significantly higher equity outcomes than those focusing only on technical aspects (t(410)=8.43, p<.001).

A district administrator explained:

"We learned the hard way that providing devices wasn't enough. Our second initiative included teacher professional development, culturally responsive digital content, family technology training, and extended support hours—that comprehensive approach finally moved our equity metrics." (K-12 administrator)

The comprehensiveness of integration varied by institutional resources and governance structures. Analysis of variance showed that decentralized governance models required more extensive coordination mechanisms to achieve comprehensive integration compared to centralized models (F(2,409)=17.82, p<.001). This finding highlights how institutional structures influence the strategies needed for effective implementation.

Longitudinal implementation data from institutions with multi-year projects revealed that comprehensive integration typically developed in phases rather than emerging fully formed. Initial implementation often focused on technical aspects, with pedagogical, cultural, and structural dimensions incorporated in subsequent iterations as implementation matured.

"The first year was focused on infrastructure and access. In year two, we addressed instructional integration and teacher support. By year three, we were finally working on the cultural and community dimensions. Looking back, we should have planned for all dimensions from the beginning, but our understanding evolved over time." (Technology director, K-12 district)

5.2.3. Continuous Evaluation Practices

Organizations demonstrating positive equity outcomes employed regular assessment using disaggregated data. Survey respondents who reported continuous evaluation practices were significantly more likely to identify and address implementation gaps (r=0.48, p<.001).

Interview data highlighted specific evaluation approaches:

"We break down all our digital engagement and outcome data by demographic categories—not just the obvious ones like race and income, but also language status, disability category, and digital access levels. That granular view helps us spot where our systems are failing specific groups." (Data analyst, K-12 district)

Evaluation approaches varied significantly by institutional size and capacity. Larger institutions more often employed formal assessment frameworks and dedicated evaluation staff, while smaller institutions relied more heavily on qualitative feedback mechanisms and teacher observations. Both approaches showed positive associations with equity outcomes when implemented systematically (r=0.41 and r=0.39 respectively, both p<.001).

The most effective evaluation practices identified through qualitative analysis shared three characteristics: (1) regular collection cycles rather than one-time assessments, (2) multiple data sources including both quantitative metrics and stakeholder experiences, and (3) clear mechanisms for translating findings into implementation adjustments.

"What makes our evaluation process work is the tight feedback loop. When we identify a gap affecting a specific student group, we have a dedicated response team that develops interventions, tests them quickly, and evaluates the impact. It's not evaluation for reporting—it's evaluation for improvement." (University assessment director)

5.2.4. Stakeholder Participation Models

Meaningful involvement of diverse stakeholders throughout planning, implementation, and evaluation processes correlated significantly with equity outcomes (r=0.61, p<.001). Interview data revealed how this participation influenced implementation:

"As a blind student, I was invited to test new learning platforms before university-wide adoption. My feedback directly influenced which system was selected and how it was configured. That's rare—usually we're just expected to adapt to whatever system is chosen." (University student)

Further analysis revealed that the quality of participation mattered more than quantity. Tokenistic participation showed no significant relationship with outcomes, while substantive participation with decision-making influence showed strong positive correlation (r=0.58, p<.001). This distinction emerged clearly in qualitative data:

"Being asked for feedback after decisions are made feels performative. When we were actually involved in setting requirements and evaluating options, the resulting system worked much better for our diverse students." (Teacher, international school)

"My son uses AAC [augmentative and alternative communication] and often struggles with digital tools. When the district included me on the technology committee, I could explain barriers he faces that weren't obvious to others. The committee's recommendations included specific adaptations based on our family's experiences." (Parent of student with complex communication needs)

Institutional context influenced participation approaches. Public institutions reported more formal stakeholder committees and governance structures, while private institutions more often utilized informal feedback channels and personalized accommodation processes. Public institutions with formal participation structures reported more equitable outcomes for historically marginalized populations, while private institutions showed stronger results for individualized accommodations.

5.2.5. Balanced Innovation-Support Frameworks

Organizations balancing technological innovation with robust human support systems reported more equitable outcomes. Survey analysis revealed that technical sophistication alone did not predict equity outcomes (r=0.14, p=.09), but the combination of technology and support resources was a strong predictor (r=0.57, p<.001).

A teacher described this balance:

"The adaptive learning system helps identify struggles, but it's our intervention team that makes the difference. The technology flags issues, but addressing them requires human relationships and understanding contexts the algorithm can't see." (K-12 teacher)

This pattern manifested differently across institutional resource levels. Well-resourced institutions more often established dedicated support teams, while resource-constrained settings developed peer support networks and teacher capacity. Both approaches showed positive associations with equity outcomes when aligned with technology complexity (r=0.44 and r=0.39 respectively, both p<.001).

Historical implementation data revealed that support systems often lagged behind technology adoption, creating temporary equity gaps until support structures caught up. Institutions with the most equitable outcomes planned support systems alongside technology selection rather than as an afterthought:

"We budget for three supports for every new technology: technical support, pedagogical support, and student success support. If we can't fund all three, we scale back the technology rather than proceeding without adequate support." (University technology director)

"Our rural district doesn't have resources for dedicated support staff, so we created a peer mentor network where teachers with digital expertise support colleagues. It's cost-effective and builds internal capacity while addressing the human side of implementation." (Rural school principal)

Figure 2 illustrates the relatfionship between these implementation patterns and equity outcomes based on survey data, showing how high implementation of these patterns correlates with stronger equity outcomes across institution types.

5.3. Barriers to Equitable Implementation

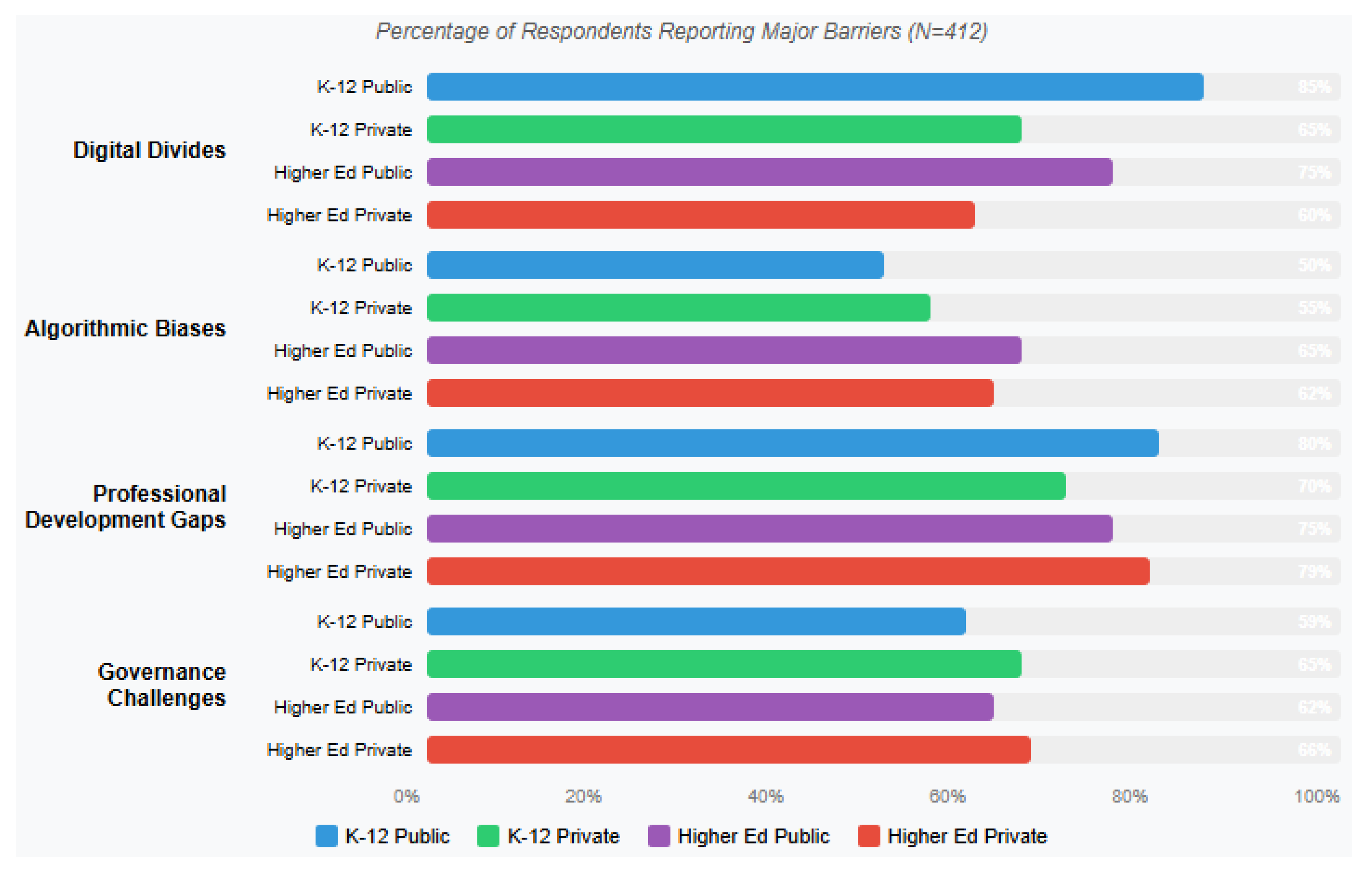

Analysis identified four primary barriers to equitable technology implementation reported consistently across data sources, as illustrated in

Figure 3 showing their prevalence across different institution types.

5.3.1. Persistent Digital Divides

Survey respondents identified home internet access (73%), device availability (68%), and digital literacy (64%) as major barriers to equitable implementation. These findings were reinforced by interview data highlighting how implementation often assumes digital resources that many students lack:

"Our district introduced a great adaptive math program, but about 30% of our students have limited or no internet at home. The program technically works offline, but syncs rarely—those students consistently fall behind in the system's progression." (Teacher, rural district)

Digital divide impacts varied significantly by institutional context. Rural institutions reported more severe connectivity challenges, with 85% citing home internet access as a major barrier compared to 62% of urban institutions (χ²=19.74, p<.001). Socioeconomic factors interacted with geography, with high-poverty rural areas reporting the most significant barriers.

Analysis of implementation histories revealed that digital divide mitigation strategies evolved over time. Early approaches focused primarily on school-based access, while more recent strategies included community partnerships, mobile hotspot programs, and offline-capable applications. Institutions implementing comprehensive digital equity plans reported significantly smaller equity gaps in technology access and use (t(204)=6.28, p<.001).

"The pandemic forced us to develop more comprehensive approaches to digital equity. We now have hotspot lending programs, community tech hubs in partner organizations, and expanded school hours for technology access. These complementary strategies reach different segments of our community who face different access barriers." (District technology coordinator)

5.3.2. Algorithmic Biases and Technical Limitations

Both survey and interview data highlighted concerns about algorithmic bias in AI-powered educational tools. Among respondents using AI tools, 58% reported concerns about bias, but only 26% reported having formal processes to evaluate algorithms for bias.

A technology developer described specific challenges:

"Speech recognition is central to many of our accessibility tools, but we've documented significantly lower accuracy rates for non-native English speakers and certain regional accents. We're working to improve this, but these biases are currently baked into many educational AI systems." (Educational technology developer)

Awareness of algorithmic bias varied significantly by respondent role, with technology specialists (78%) and inclusion specialists (72%) reporting higher concern levels than administrators (52%) and general educators (48%) (F(3,408)=14.37, p<.001). This suggests that specialized knowledge influences recognition of these issues, highlighting the importance of diverse expertise in technology decision-making.

Qualitative analysis revealed that algorithmic bias manifested in multiple forms across different technologies and contexts:

Language biases in natural language processing systems

Cultural biases in content recommendation algorithms

Socioeconomic biases in predictive analytics systems

Ability biases in adaptive learning platforms

"Our early warning system for student success flagged 'irregular login patterns' as a risk factor, but we discovered this disproportionately identified students who share devices with family members or have intermittent internet. What the algorithm saw as 'irregular' was actually a reflection of resource constraints, not academic disengagement." (College student success coordinator)

Institutions addressing these biases most effectively employed three key strategies: diverse testing groups, transparent algorithm documentation requirements, and regular bias audits of implemented systems.

5.3.3. Professional Development Gaps

Survey results revealed significant gaps in educator preparation for inclusive technology implementation, with 76% of respondents indicating inadequate training in this area. Regression analysis identified professional development as a significant predictor of implementation quality (β=0.38, p<.001).

Interview data contextualized these findings:

"We're expected to use these sophisticated adaptive systems with special education students, but most of us received at most a one-hour overview. I need much deeper training on how to interpret the data, customize the settings, and integrate the system with other accommodations." (Special education teacher)

Professional development approaches varied by institutional context and resources. Higher education institutions more frequently employed specialist-led models with dedicated instructional technology staff, while K-12 settings more often utilized teacher-leader and community of practice approaches. Both models showed positive associations with equity outcomes when implemented comprehensively (r=0.43 and r=0.39 respectively, both p<.001).

Historical implementation data revealed that professional development effectiveness improved when technology training explicitly integrated inclusive pedagogical approaches rather than treating them as separate domains:

"Our first rounds of training focused on technical features, with separate training on accommodations. When we integrated inclusive design principles directly into the technology training, teachers implemented more effectively for all students." (Professional development coordinator)

"The training model that worked best for us combined just-in-time resources, coaching relationships, and structured learning communities. The worst approach was the single pre-implementation workshop with no follow-up. Professional learning has to be ongoing and embedded in practice to actually change implementation." (District professional development specialist)

5.3.4. Governance and Policy Challenges

Both survey and interview data highlighted governance challenges, with 63% of respondents reporting unclear policies regarding data usage, privacy, and algorithmic decision-making in educational contexts.

A policy expert explained:

"Educational institutions are adopting powerful AI systems without adequate governance frameworks. Questions about who owns student data, how algorithms can be used in educational decisions, and what transparency requirements exist are being addressed ad hoc rather than through comprehensive policies." (Education policy researcher)

Governance challenges varied by regional and national policy contexts. Institutions in regions with comprehensive data protection regulations (e.g., European GDPR jurisdictions) reported clearer governance frameworks than those in regions with limited regulation (F(5,406)=18.74, p<.001). This finding highlights the importance of policy environments in shaping implementation approaches.

Qualitative analysis identified four distinct governance models across institutions:

Centralized technology governance through dedicated committees

Distributed governance through departmental autonomy

Compliance-driven governance focused on minimum requirements

Participatory governance involving diverse stakeholders

Participatory governance models showed the strongest association with equity outcomes (F(3,408)=21.36, p<.001), particularly when they included representation from marginalized stakeholder groups.

"Our technology governance shifted from IT-dominated to cross-functional with strong representation from accessibility services, equity offices, and student advocates. This broader representation helped us anticipate and address equity issues earlier in the implementation process." (University administrator)

5.4. Interaction Zones Analysis

Analysis of data through the lens of the EET model revealed distinct patterns within each interaction zone:

5.4.1. Access and Infrastructure Zone

Survey data showed significant correlation between digital transformation maturity and accessibility implementation (r=0.47, p<.001). However, qualitative analysis revealed that even mature digital environments often contained accessibility barriers:

"Our university is considered a digital transformation leader, but as a student with ADHD, I struggle with our learning management system. It's overwhelmingly complex, inconsistent between courses, and has no built-in organizational supports." (University student)

Statistical analysis of survey data revealed that formal accessibility requirements in procurement processes significantly predicted better outcomes for disabled students (β=0.43, p<.001). This relationship was moderated by institutional size, with larger institutions showing stronger effects, likely due to greater procurement leverage and specialist resources.

Analysis of implementation histories revealed that access considerations evolved over time in most institutions. Early accessibility efforts typically focused on technical compliance for specific disabilities, while more mature implementations addressed broader usability and cognitive accessibility concerns. This evolution reflected growing understanding of inclusive design principles and expanding conceptions of accessibility.

"Five years ago, our accessibility work focused almost exclusively on screen reader compatibility. Now we're addressing cognitive load, executive function supports, and linguistic accessibility. Our understanding of what constitutes 'accessibility' has broadened significantly as we've worked with more diverse learners." (Accessibility specialist)

5.4.2. Personalization and Adaptation Zone

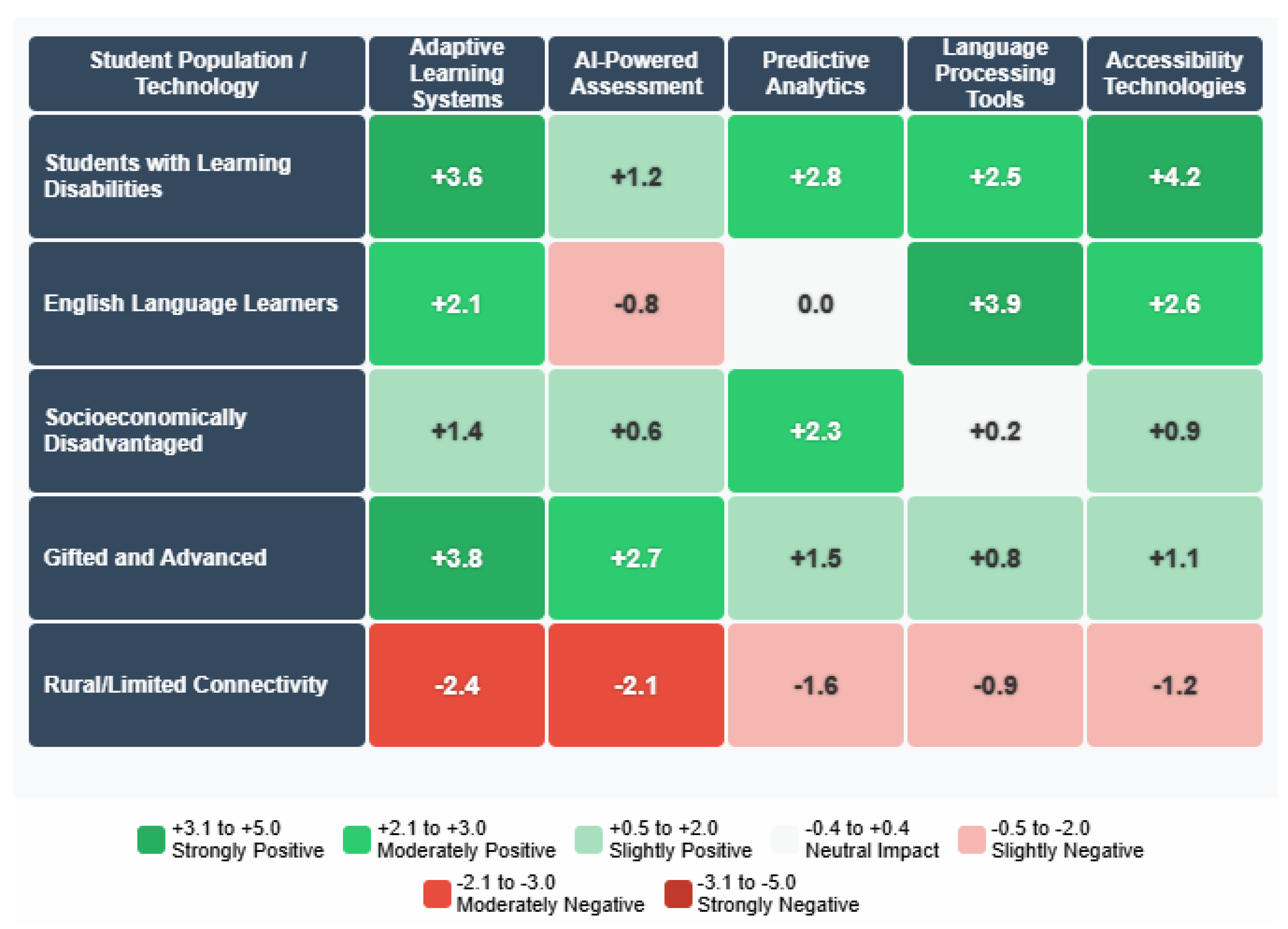

Analysis revealed complex patterns in the personalization zone. AI-powered personalization showed positive correlation with reported learning outcomes overall (r=0.38, p<.001), but this relationship varied significantly by student population. Interview data highlighted both benefits and concerns:

"The adaptive system has transformed reading instruction for many of my struggling readers—it's patient, gives immediate feedback, and adjusts in ways I can't do for 30 students simultaneously." (Elementary teacher)

"Personalization sounds good in theory, but I've observed how it can lower expectations for certain student groups. The algorithms sometimes recommend less challenging content for English learners based on language rather than cognitive ability." (Curriculum specialist)

Factor analysis of survey data identified key components of effective personalization using principal component analysis with varimax rotation. Three factors emerged explaining 72% of variance: transparency of adaptation logic (factor loading=0.78), human oversight capability (0.76), and learner agency in adaptation decisions (0.74). These factors were consistent across institution types, suggesting core principles for effective personalization regardless of context.

Specific AI technologies demonstrated different equity implications across implementation contexts. For example, intelligent tutoring systems showed particularly strong positive outcomes for students with learning disabilities when implemented with appropriate support (d=0.67, p<.001), while automated writing feedback tools showed mixed results for English language learners, with benefits for mechanical aspects but potential limitations for higher-order writing development.

"Our predictive analytics system significantly improved outcomes for first-generation students when paired with proactive advising, but had no measurable impact when implemented without the human support component. The technology alone wasn't enough—it required integration with student support systems to translate insights into effective interventions." (University institutional research director)

Institutional context influenced personalization implementation approaches. K-12 settings more frequently employed structured adaptive systems with predetermined pathways, while higher education institutions more often utilized recommendation systems preserving greater learner autonomy. The relationship between personalization and equity outcomes was moderated by the degree of learner control, with systems balancing algorithmic recommendations with learner choice showing the strongest positive effects (F(2,254)=16.89, p<.001).

5.4.3. System Transformation Zone

In the system transformation zone, survey data revealed that organizations implementing AI within broader digital transformation initiatives reported significantly higher equity outcomes than those implementing AI as standalone tools (t(254)=7.26, p<.001).

Interview data provided insight into this pattern:

"When we integrated predictive analytics within our whole-institution student success framework—connecting it with advising, mental health services, and academic supports—we saw graduation gaps close. When departments used similar tools in isolation, the impact was minimal." (University administrator)

Regression analysis identified institutional factors predicting successful system transformation, including leadership commitment to equity (β=0.46, p<.001), cross-functional implementation teams (β=0.39, p<.001), and aligned incentive structures (β=0.37, p<.001). These factors were consistent across institution types and sizes, suggesting fundamental principles for system transformation regardless of context.

Governance structures significantly influenced transformation approaches. Institutions with collaborative governance models involving both technical and pedagogical leadership reported more comprehensive transformation than those with technology-dominated governance (F(2,409)=19.36, p<.001). This finding highlights the importance of cross-functional leadership in successful system transformation.

Implementation history analysis revealed that successful system transformations typically progressed through distinct phases over time:

Initial technology adoption focused on efficiency

Recognition of equity implications and challenges

Intentional redesign with explicit equity goals

Continuous improvement based on equity metrics

Institutions demonstrating the most equitable outcomes had progressed to the later phases, emphasizing the developmental nature of system transformation efforts.

"Our first AI implementation was a classic case of technology-driven change—we saw interesting capabilities and deployed them without much thought to equity. The equity considerations emerged from observation and feedback, leading us to completely redesign the initiative. Looking back, I wish we'd centered equity from the beginning rather than treating it as an afterthought." (College president)

5.5. Contextual Factors Analysis

Additional analysis examined how institutional context variables influenced implementation patterns and outcomes, as illustrated in

Figure 4 showing the relationship between technology implementation and student outcomes across different contexts. Multiple regression models including contextual variables explained significantly more variance in equity outcomes (R²=0.71) than models considering only implementation patterns (R²=0.63) (F-change=15.37, p<.001), highlighting the importance of contextual understanding.

5.5.1. Funding Models and Resource Levels

Funding mechanisms significantly influenced implementation approaches. Institutions with stable multi-year funding reported more comprehensive and strategic implementations than those relying on annual or grant-based funding (F(2,409)=14.28, p<.001). However, resource level effects were moderated by implementation quality—well-resourced institutions with poor implementation patterns showed worse equity outcomes than resource-constrained institutions with strong implementation practices (interaction term β=0.31, p<.001).

Qualitative data revealed how funding structures shaped implementation decisions:

"With grant funding, we felt pressure to implement quickly to show results within the funding period. That rushed timeline meant less stakeholder input and testing. Our operational budget-funded initiatives allowed more thorough planning and testing, which ultimately yielded better results." (District technology director)

Figure 5 further illustrates how different AI technologies impact various student populations, showing particularly strong positive effects for adaptive learning systems among students with learning disabilities, while revealing challenges for rural students with limited connectivity across most technology types.

"We found that sustainable funding models allowed us to implement with a long-term perspective rather than chasing quick wins. When we had to demonstrate immediate outcomes to secure the next funding cycle, we tended to focus on easier-to-move metrics rather than addressing more complex equity challenges." (University technology leader)

5.5.2. Governance Structures

Institutional governance structures significantly influenced implementation patterns. Centralized governance models showed stronger policy consistency but less responsiveness to diverse needs, while distributed models showed greater adaptation but more inconsistency (F(2,409)=11.42, p<.001). Hybrid models combining centralized standards with local implementation flexibility showed the strongest association with positive equity outcomes (β=0.38, p<.001).

This relationship was moderated by institutional size, with larger institutions benefiting more from hybrid approaches than smaller institutions where simpler governance structures were sometimes more effective (interaction term β=0.24, p<.01).

"Our large university initially tried to standardize everything through central governance, but this created friction with departments serving specialized student populations. We evolved toward a model with centralized standards and distributed implementation authority. This balanced model maintained core equity principles while allowing context-specific adaptations." (University technology governance director)

5.5.3. Regulatory and Policy Environments

National and regional policy environments significantly influenced implementation approaches, particularly regarding data governance and privacy practices. Institutions in regions with comprehensive data protection regulations implemented more robust consent processes and data minimization practices than those in less regulated environments (t(410)=9.37, p<.001).

These regulatory differences had equity implications, with stronger data protection associated with higher trust and participation among marginalized populations:

"Parents in our immigrant communities were hesitant about the adaptive learning system until we implemented the comprehensive privacy controls required by our state regulations. The transparent data practices increased trust and participation significantly." (Family engagement coordinator)

"Operating in multiple countries means navigating different regulatory environments. In regions with stringent data protection laws, we developed more transparent data governance models that we've now implemented globally. The regulations initially seemed constraining but ultimately pushed us toward more ethical and inclusive practices." (EdTech company executive)

5.5.4. Institutional Culture

Institutional culture emerged as a significant predictor of implementation quality beyond structural factors. Survey analysis identified three cultural factors significantly associated with positive equity outcomes: collaborative problem-solving norms (β=0.35, p<.001), learning orientation toward challenges (β=0.32, p<.001), and explicit equity values (β=0.41, p<.001).

These cultural factors moderated the relationship between resource levels and outcomes, with strong equity cultures achieving better outcomes with limited resources than resource-rich institutions lacking equity-centered cultures (interaction term β=0.36, p<.001).

"The institutions implementing most successfully share a culture where equity isn't a separate initiative but woven into their identity. They don't ask 'should we consider equity?' but rather 'how do we ensure equity?' It's a fundamental shift in organizational mindset that influences every implementation decision." (Policy researcher)

6. Discussion

6.1. The Equity Paradox in Educational Technology

This study's findings highlight what can be termed the "equity paradox" in educational technology: the same innovations that show promise for addressing educational disparities often risk exacerbating them when implemented without explicit equity frameworks. This paradox manifested consistently across all three interaction zones of the EET model.

In the access zone, digital transformation initiatives expanded learning opportunities while simultaneously creating new barriers for students lacking technological resources or digital literacy. In the personalization zone, AI-powered adaptive systems provided valuable customization for some learners while potentially reinforcing biases or limiting opportunities for others. In the system transformation zone, institutions redesigned educational processes in ways that either challenged or reinforced existing power structures and inequities.

This paradox aligns with Reich's (2023) "innovation-equality dilemma" but extends it by identifying specific mechanisms through which this tension operates across different implementation contexts. The findings suggest that resolving this paradox requires intentional design approaches specifically targeting equity outcomes rather than assuming technology benefits will naturally extend to all learners.

The equity paradox manifested differently across institutional contexts. Well-resourced institutions often faced "implementation complexity" challenges where sophisticated technologies created new forms of exclusion, while resource-constrained institutions more frequently encountered "fundamental access" barriers. This distinction suggests that equity strategies must be contextually tailored rather than universally applied.

From a theoretical perspective, the equity paradox demonstrates how educational technologies function as sociotechnical systems rather than neutral tools. Drawing on perspectives from science and technology studies (Selwyn & Facer, 2023), the findings show how technologies embody values, assumptions, and power relationships that influence their equity impacts. This theoretical framing helps explain why technical solutions alone prove insufficient for addressing educational inequities.

6.2. From Implementation to Integration

The analysis revealed a critical distinction between technology implementation (installing and using new tools) and technology integration (embedding tools within comprehensive educational ecosystems). Survey and interview data consistently showed that integration predicted equity outcomes more strongly than implementation alone.

This finding extends previous work by Tondeur et al. (2023) on technology integration by identifying specific factors that facilitate equity-centered integration: institutional alignment around equity goals, cross-functional collaboration, professional development ecosystems, and inclusive governance structures. While Tondeur's research emphasized teacher-level integration practices, this study highlights the institutional conditions necessary for equitable integration at scale. These factors operated across all five implementation patterns identified in the analysis.

The distinction between implementation and integration helps explain why similar technologies often produce dramatically different equity outcomes across contexts. It also suggests that educational leaders should focus less on adopting specific technologies and more on building the institutional capacities that enable equitable integration.

From an implementation science perspective (Damschroder et al., 2024), these findings highlight how contextual adaptation, implementation climate, and organizational readiness significantly influence technology outcomes. The data reveal that implementation approaches must be tailored to specific institutional contexts rather than following standardized models, while still adhering to core principles of inclusive design and equitable access.

Temporal analysis of implementation histories further revealed that integration quality typically developed over time through multiple iterations rather than emerging fully formed. This developmental perspective suggests that equity-centered integration requires sustained commitment rather than one-time initiatives, with continuous refinement based on emerging outcomes and stakeholder feedback.

6.3. Power Dynamics and Participatory Approaches

The findings highlight how power dynamics influence technology adoption and configuration decisions, often marginalizing the perspectives of those most affected by these technologies. Survey data showed that only 28% of respondents reported meaningful participation of diverse stakeholders in technology decision-making, despite this factor's strong correlation with equity outcomes (r=0.61, p<.001).

This finding aligns with Costanza-Chock's (2024) concept of "design justice," which emphasizes centering marginalized perspectives in technology design processes. This research extends this framework by documenting specific institutional practices that enable more participatory approaches, including representative advisory boards, compensated feedback mechanisms, and modified procurement processes requiring evidence of diverse user testing.

The participatory patterns identified in this analysis challenge traditional top-down models of educational technology adoption, suggesting that equity goals require fundamental reconsideration of who participates in technology decisions and how their participation is structured.

Power dynamics manifested differently across institutional contexts. Elite institutions often demonstrated "participation paradoxes" where extensive stakeholder mechanisms existed formally but exerted limited influence on decisions, while some community-based institutions demonstrated more authentic participation with simpler structures. This finding suggests that participation quality matters more than formal mechanisms alone.

From a critical theory perspective, these findings illustrate how educational technologies can either reinforce or challenge existing power relationships depending on their implementation processes. Technologies implemented through inclusive, participatory approaches more often served as tools for educational democratization, while those implemented through top-down processes more frequently reinforced existing hierarchies and exclusions.

6.4. The Education Equity Technology Model: Theoretical Implications

The Education Equity Technology (EET) model developed through this research offers several theoretical contributions to understanding the relationship between technology and educational equity. First, it provides an integrated framework connecting previously siloed research traditions in digital transformation, AI ethics, and inclusive education. Second, it identifies specific interaction zones where these domains create both opportunities and challenges for educational equity. Third, it emphasizes the dynamic nature of these relationships across different contexts and implementation approaches.

The model extends sociotechnical systems theory (Orlikowski, 2022) by specifically addressing how technical and social elements interact in educational contexts. It demonstrates that technology effects are neither predetermined nor neutral, but rather shaped by implementation processes, institutional contexts, and power relationships. This theoretical framing helps explain the wide variation in equity outcomes observed across similar technologies in different settings.

The EET model also contributes to implementation science by identifying zone-specific factors that influence implementation effectiveness. In the access zone, procurement practices and infrastructure planning emerged as critical factors. In the personalization zone, algorithm transparency and human oversight capabilities proved essential. In the system transformation zone, cross-functional leadership and aligned incentive structures were determinative. These zone-specific factors provide a more nuanced understanding of implementation dynamics than generic implementation frameworks.

From a practical theoretical perspective, the model provides an analytical framework for examining how specific technologies and implementation approaches influence educational equity across diverse contexts. This framework can guide both future research and practical implementation efforts by highlighting critical interaction points and implementation considerations in each zone.

6.5. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, while the sample included diverse educational contexts, representation from Global South regions (combined 15% from Africa and South America) is lower than desired, potentially limiting applicability of findings to these contexts. Future research should specifically examine how these relationships manifest in diverse global settings, particularly in resource-constrained environments with different technological infrastructures and educational traditions.

Second, the voluntary nature of participation may have attracted respondents with stronger interest in educational technology, potentially introducing selection bias that overrepresents technology-positive perspectives. Future studies should employ targeted sampling strategies to ensure adequate representation of technology-skeptical viewpoints and institutions at earlier stages of digital transformation.

Third, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference and understanding of how implementations evolve over time. While the study incorporated retrospective data on implementation histories, longitudinal research tracking implementations over multiple years would provide stronger evidence regarding developmental trajectories and causal relationships between implementation approaches and equity outcomes.

Several specific directions for future research emerge from these limitations and the study's findings:

Longitudinal Implementation Studies: Future research should track technology implementations longitudinally across multiple years to better understand how equity impacts evolve over time and what factors influence developmental trajectories.

Contextual Variation Analysis: More systematic examination of how implementation patterns and outcomes vary across diverse institutional contexts would strengthen understanding of contextual influences and appropriate adaptation strategies.

Student-Centered Experience Research: Additional research employing participatory methods to center marginalized student experiences with educational technologies would provide valuable insights for more inclusive design and implementation.

Policy Ecosystem Analysis: Comparative research examining how different policy environments influence technology implementation and equity outcomes would help identify supportive policy frameworks for equitable implementation.

Assessment Tool Development: Further development and validation of practical assessment tools for measuring the equity impact of educational technologies would strengthen both research and practice in this area.

Additionally, the growing capabilities of generative AI systems suggest an important new area for research at the intersection of these domains. These systems introduce both new possibilities for personalization and new concerns regarding bias, privacy, and educational authenticity that were only beginning to emerge during this study's data collection. Future research should specifically address these rapidly evolving technologies and their equity implications.

7. Conclusion: Toward Equitable Digital Learning Ecosystems

This study examined the complex interplay among digital transformation, AI adoption, and inclusive education through mixed-methods research integrating literature review, survey data, and stakeholder interviews. The findings document both the transformative potential and significant challenges of harnessing these forces for greater educational equity.

The research makes several key contributions to both theory and practice. Theoretically, it introduces the Education Equity Technology (EET) model as a framework for understanding the interaction zones where digital transformation, AI, and inclusive education converge. This model extends sociotechnical systems theory by specifically addressing educational equity dimensions and identifying zone-specific dynamics that influence implementation outcomes. The identification of the "equity paradox" further contributes to theoretical understanding of how technologies simultaneously create opportunities and challenges for educational equity.

Practically, the identification of five key implementation patterns—intentional design, comprehensive integration, continuous evaluation, stakeholder participation, and balanced innovation-support frameworks—offers evidence-based guidance for practitioners seeking to create more equitable learning environments. These patterns, validated across diverse institutional contexts, provide a foundation for more effective implementation approaches centered on equity goals.

The persistent barriers identified in this research—digital divides, algorithmic biases, professional development gaps, and governance challenges—highlight the ongoing work needed to ensure technological innovations advance rather than undermine educational equity. Addressing these barriers requires coordinated effort across policy, institutional, and classroom levels, with particular attention to how these challenges manifest differently across diverse contexts.

7.1. The Education Equity Technology Implementation Framework

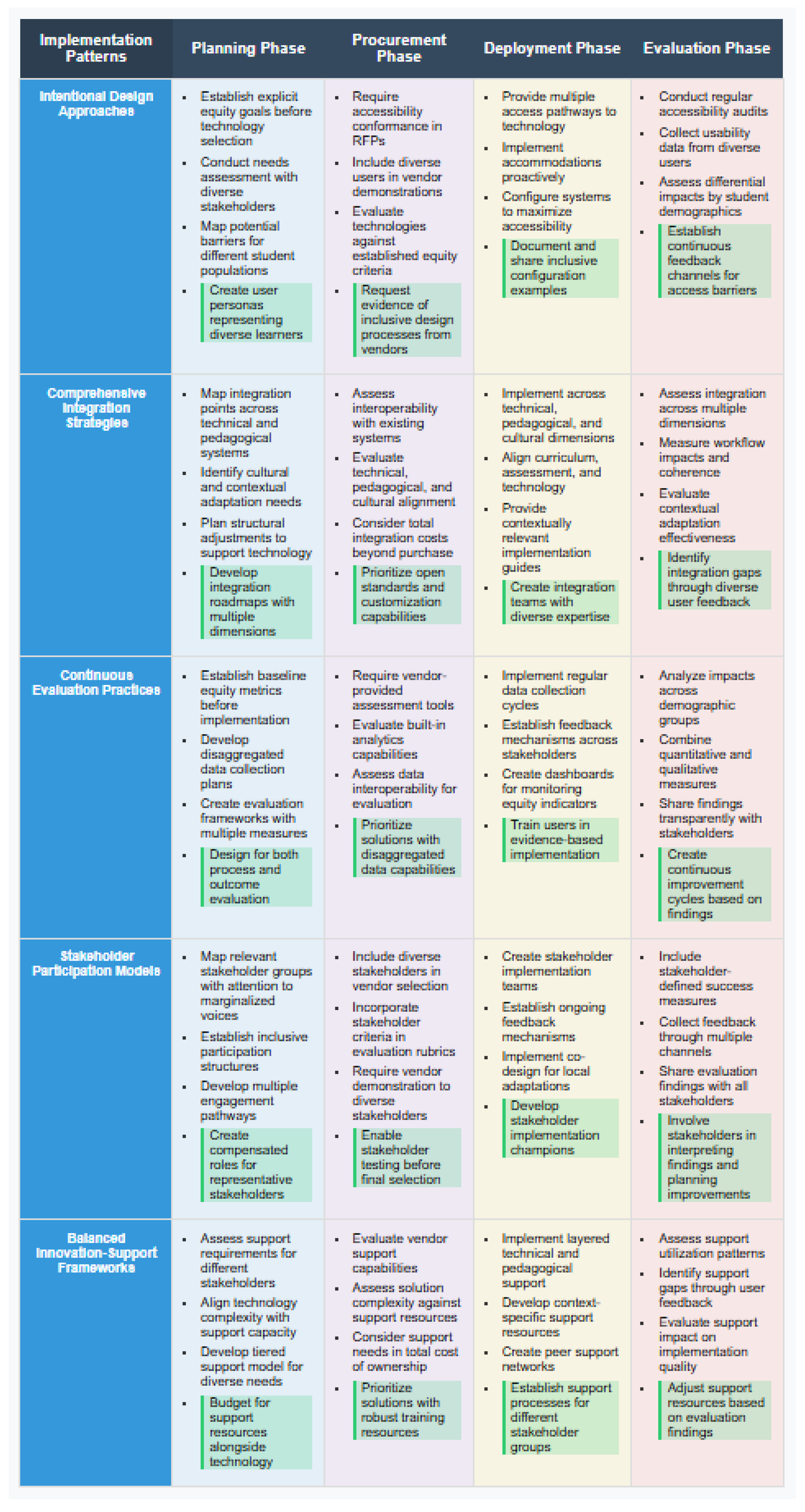

Building on these findings,

Figure 6 presents the Education Equity Technology Implementation Framework—a structured approach for guiding equitable technology implementation across diverse educational contexts. This framework organizes the five key implementation patterns across four implementation phases: planning, procurement, deployment, and evaluation. Highlighted practices (green) represent high-impact approaches identified through empirical analysis. The framework should be adapted to specific institutional contexts, with implementation phasing and emphasis adjusted according to local needs, resources, and priorities.

This framework provides practical guidance for educational leaders while acknowledging the need for contextual adaptation. Rather than prescribing universal approaches, it identifies core principles that should be adapted to specific institutional contexts, resource levels, and student populations. The framework emphasizes process over specific technologies, recognizing that implementation approaches influence equity outcomes more strongly than the technologies themselves.

The findings have significant implications for educational policy at institutional, regional, and national levels. At the institutional level, results suggest that equity-centered technology policies should address not just technology selection but implementation processes, professional development, support structures, and governance mechanisms. Institutional policies requiring accessibility standards in procurement, diverse stakeholder participation in decision-making, and regular equity impact assessment would support more inclusive implementations.

At regional and national levels, findings suggest several policy directions. First, addressing digital divide issues through infrastructure investment, connectivity initiatives, and device access programs remains essential for equitable digital education. Second, data governance frameworks balancing innovation with privacy protection can create the trust necessary for effective implementation, particularly among marginalized communities. Third, teacher preparation and professional development policies should explicitly address inclusive technology implementation rather than treating technical and inclusive education competencies as separate domains.

The significant influence of institutional context on implementation outcomes suggests that policies should focus on building institutional capacity for equitable implementation rather than mandating specific technologies or approaches. This capacity-building approach would enable contextually appropriate implementations while ensuring adherence to core equity principles.

7.3. Future Directions and Final Reflections

The findings suggest that technology alone cannot resolve educational inequities—but thoughtfully implemented technologies embedded within comprehensive equity strategies can help create learning ecosystems that better serve all learners. By attending to the implementation patterns and addressing the barriers identified in this research, educational leaders can work toward digital learning ecosystems that fulfill the promise of more inclusive, responsive, and effective education for all students regardless of background, ability, or circumstance.

Future developments at this intersection will require continued vigilance and adaptation. As AI capabilities advance, new opportunities and challenges will emerge that require thoughtful consideration of equity implications. As digital transformation reshapes educational structures, careful attention to inclusion and accessibility will remain essential. And as inclusive education evolves to encompass increasingly diverse learner populations, technological approaches must adapt accordingly.

The path forward requires sustained collaboration among educators, technologists, policymakers, researchers, and diverse learner communities. By working together across these boundaries, we can harness the transformative potential of educational technologies while ensuring they advance rather than undermine our commitment to educational equity for all learners.

Conflicts of Interest and Informed Consent Declarations

I declare that I have no conflicts of interest. All participants provided written informed consent.

Appendix A: Survey Instrument

Survey Instrument: Digital Transformation, AI, and Inclusive Education Study

Introduction and Consent Information

Thank you for your interest in participating in this research study examining the intersection of digital transformation, artificial intelligence, and inclusive education. This survey will take approximately 20-25 minutes to complete.

Your participation is voluntary, and all responses will remain confidential. Data will be reported in aggregate form only, with no identifying information linked to individual responses. This study has been approved by the [University Name] Institutional Review Board (#IRB-2024-0157).

By proceeding with this survey, you confirm that:

You are 18 years or older

You currently work in an educational setting

-

You voluntarily agree to participate in this research

□ I consent to participate in this study

Section 1: Demographic Information

-

What is your primary role in education? (Select one)

□ Teacher/Instructor

□ Administrator

□ Educational Technology Specialist

□ Student Support Staff

□ Other (please specify): _________________

-

In which type of institution do you primarily work? (Select one)

□ K-12 Public School

□ K-12 Private School

□ Public Higher Education Institution

□ Private Higher Education Institution

□ Other (please specify): _________________

-

In which region is your institution located?

□ North America

□ Europe

□ Asia

□ Africa

□ South America

□ Oceania

□ Other (please specify): _________________

-

How many years of experience do you have in education?

□ 0-5 years

□ 6-10 years

□ 11-15 years

□ 16+ years

-

Which of the following best describes your institution's setting?

□ Urban

□ Suburban

□ Rural

□ Online/Virtual

-

Approximately how many students does your institution serve?

□ Less than 500

□ 501-1,000

□ 1,001-5,000

□ 5,001-15,000

□ More than 15,000

Section 2: Digital Transformation Implementation

For the following questions, please rate the level of implementation at your institution using the scale provided.

- 7.

-

How would you rate the overall level of digital transformation at your institution?

□ 1 (Very Low) □ 2 (Low) □ 3 (Medium) □ 4 (High) □ 5 (Very High)

- 8.

-

To what extent has your institution implemented the following digital transformation elements?

-

Learning management systems

□ 1 (Not at all) □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 (Comprehensive implementation)

-

Digital curriculum resources

□ 1 (Not at all) □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 (Comprehensive implementation)

-

Cloud-based collaboration tools

□ 1 (Not at all) □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 (Comprehensive implementation)

-

Digital assessment systems

□ 1 (Not at all) □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 (Comprehensive implementation)

-

Digital infrastructure (Wi-Fi, devices, etc.)

□ 1 (Not at all) □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 (Comprehensive implementation)

- 9.

-

Which of the following statements best describes your institution's approach to digital transformation? (Select one)

□ Digital tools added to traditional educational models

□ Some processes redesigned around digital capabilities

□ Significant redesign of educational approaches leveraging digital tools

□ Comprehensive transformation of educational model through digital technologies

□ Not sure

- 10.

-

Does your institution have a formal digital transformation strategy or plan?

□ Yes

□ No

□ In development

□ Not sure

- 11.

-

How would you rate your institution's investment in the following areas? (1=Very Low, 5=Very High)

-

Technology infrastructure

□ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5

-

Digital content and resources

□ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5

-

Professional development for digital skills

□ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5

-

Technical support staff

□ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5

Section 3: AI Implementation

- 12.

-

How would you rate the overall level of AI implementation at your institution?

□ 1 (Very Low) □ 2 (Low) □ 3 (Medium) □ 4 (High) □ 5 (Very High)

- 13.

-

Which of the following AI technologies are currently implemented at your institution? (Select all that apply)

□ Adaptive learning systems

□ AI-powered assessment tools

□ Predictive analytics for student success

□ Natural language processing tools

□ AI-enhanced accessibility features

□ Automated administrative systems

□ Intelligent tutoring systems

□ None of the above

□ Other (please specify): _________________

- 14.

-

For the AI technologies implemented at your institution, to what extent are they used for the following purposes? (1=Not at all, 5=Extensively)

-

Personalizing learning experiences

□ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ N/A

-

Identifying at-risk students

□ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ N/A

-

Automating administrative tasks

□ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ N/A

-

Supporting students with disabilities

□ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ N/A

-

Providing feedback to students

□ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 □ N/A

- 15.

-

Does your institution have formal policies or guidelines regarding the following aspects of AI use? (Select all that apply)

□ Data privacy and security

□ Algorithmic bias assessment

□ Transparency in AI decision-making

□ Human oversight of AI systems

□ Ethical use of student data

□ None of the above

□ Not sure

- 16.

-

How concerned are you about algorithmic bias in the AI systems used at your institution?

□ 1 (Not at all concerned) □ 2 □ 3 □ 4 □ 5 (Extremely concerned) □ N/A

- 17.

-

Does your institution have formal processes to evaluate AI systems for potential bias?

□ Yes

□ No

□ In development

□ Not sure

Section 4: Inclusive Education Practices

- 18.

-