Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Analytical Framework

2.1. Data Description

2.2. Relationship Between Parameters

2.3. Data Pre-Processing Based on Statistical Measures

2.4. Continuing to Perform Experiments

2.5. Machine Learning Models

2.6. Model Evaluation Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Semi-Empirical Approach

3.2. Machine Learning Approach

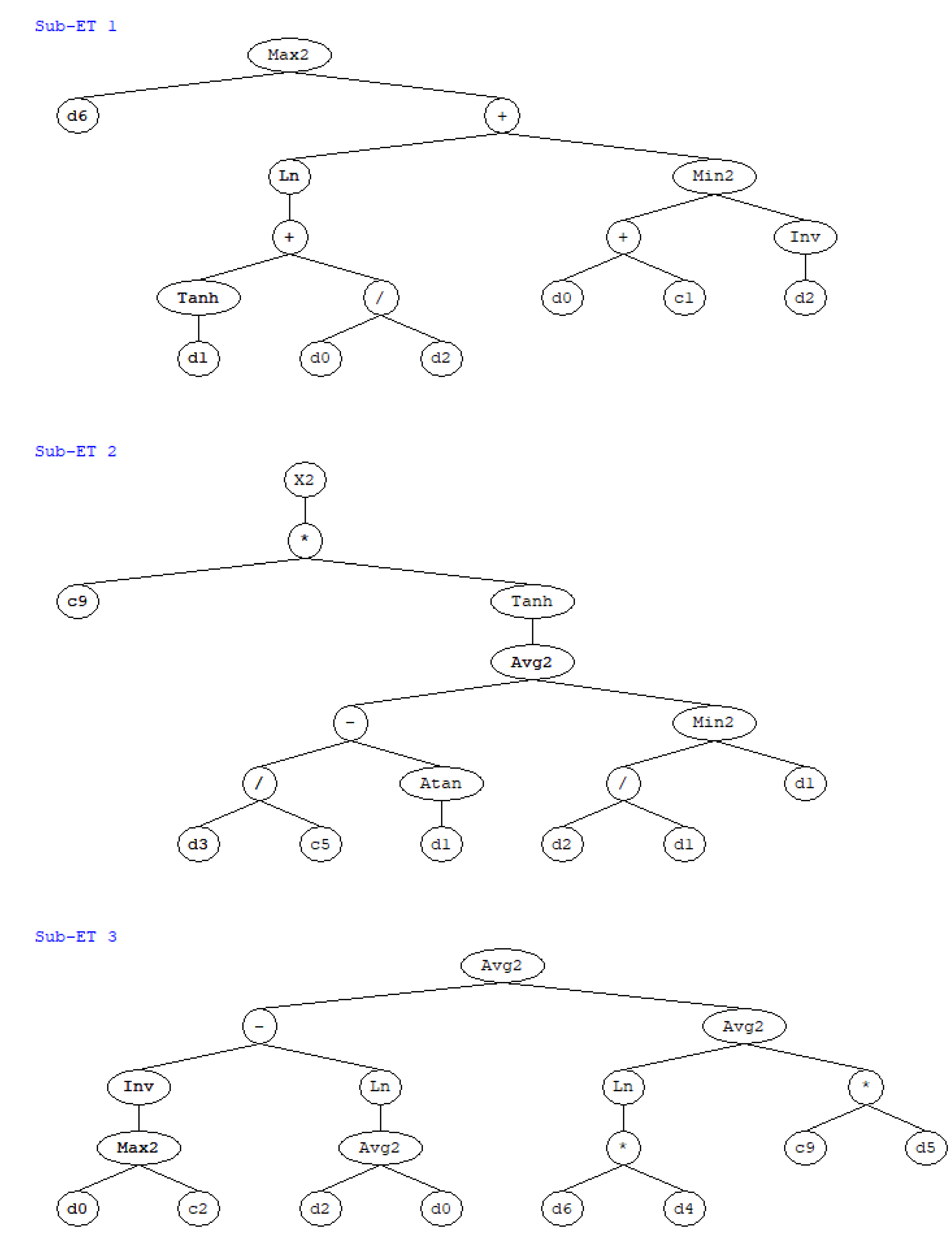

3.2.1. Gene Expression Programming

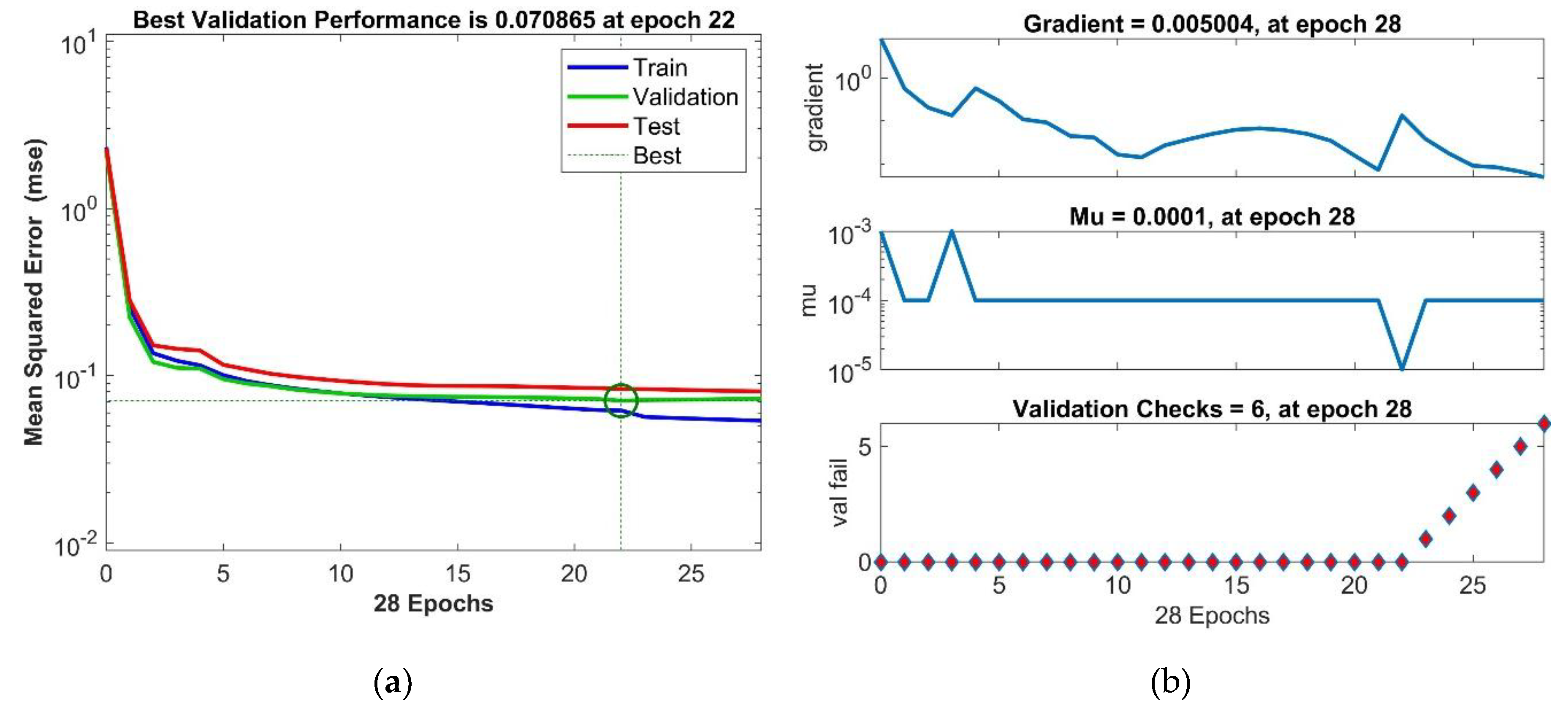

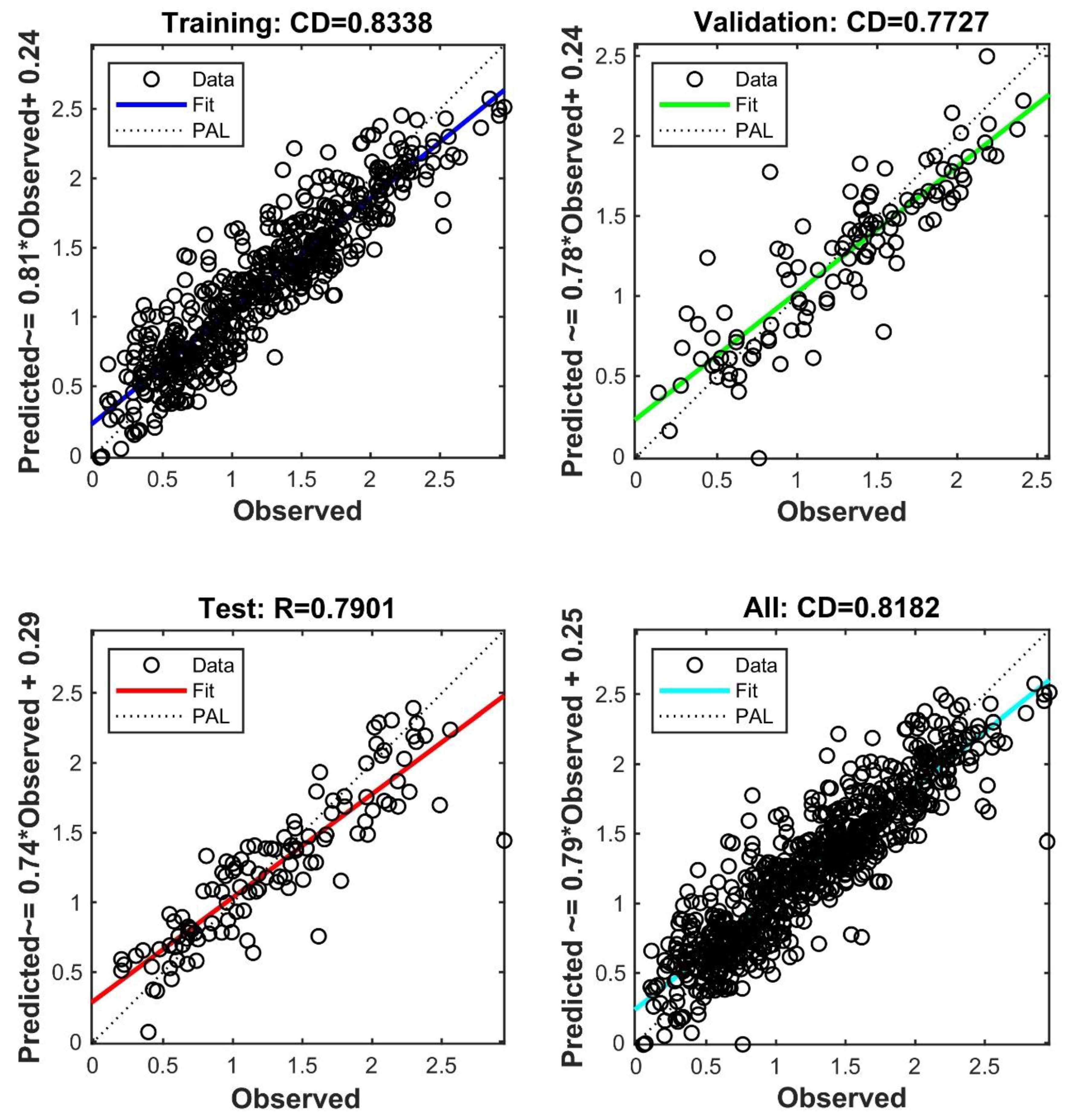

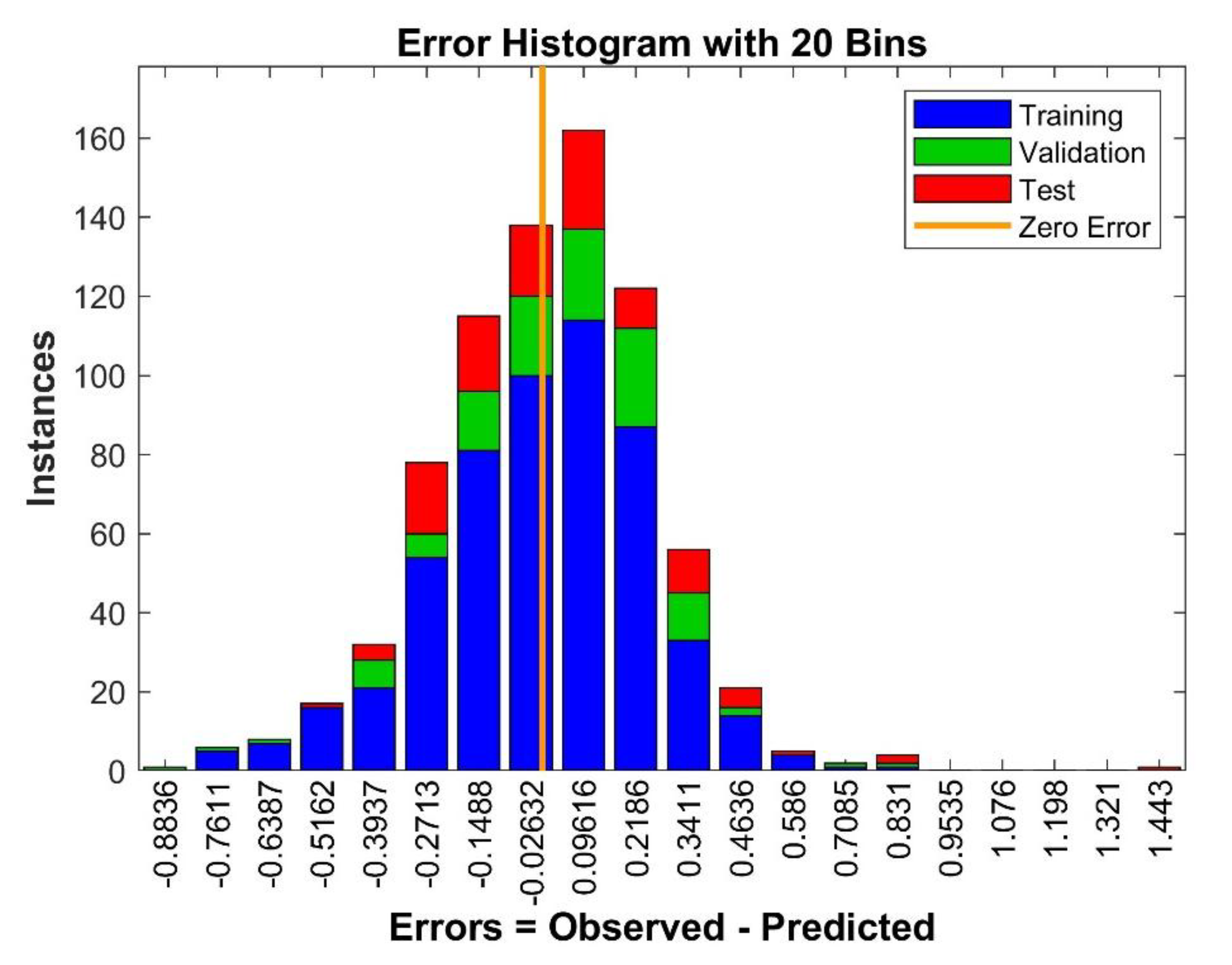

3.2.2. Feedforward Neural Network (FFNN)

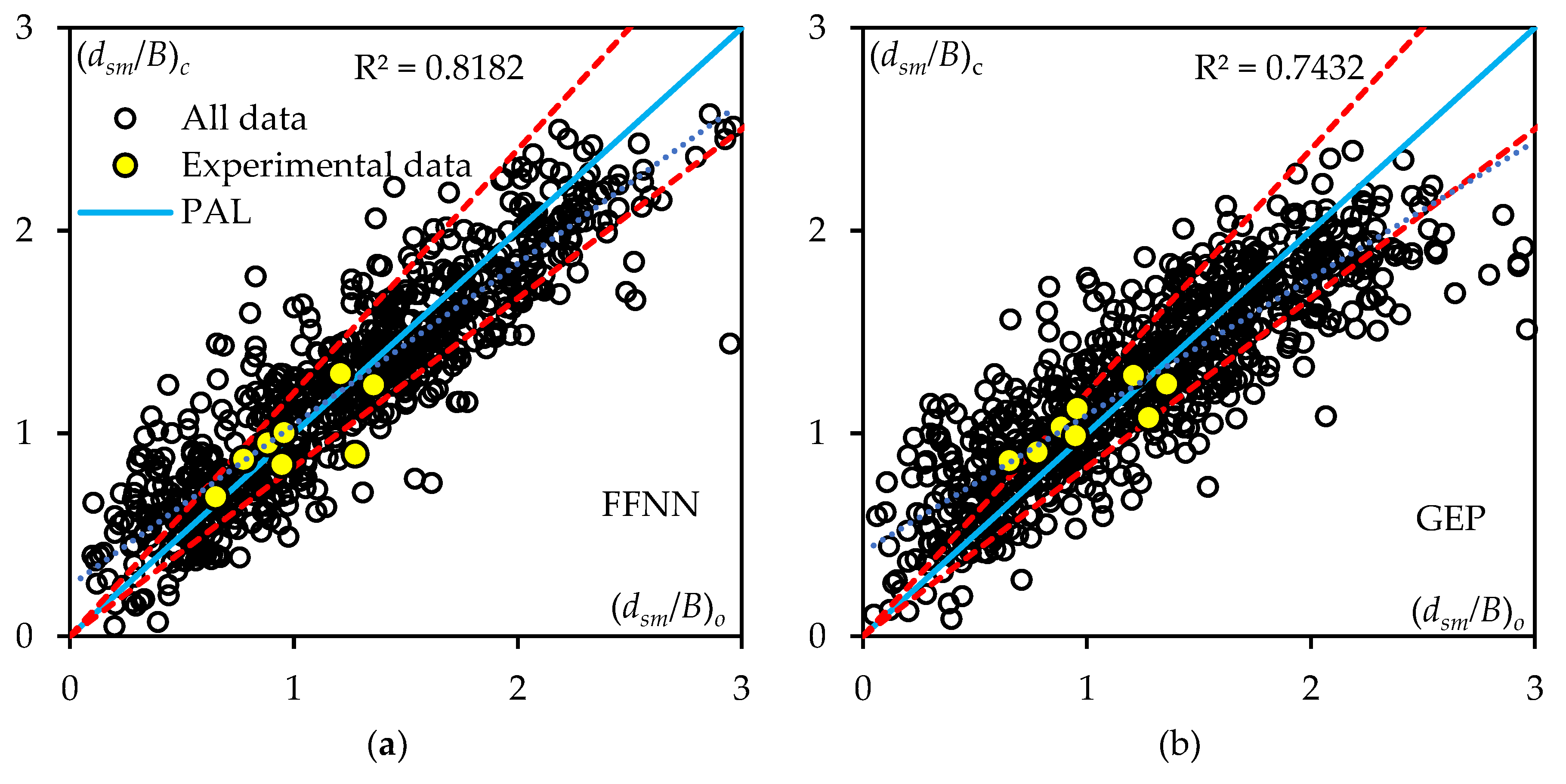

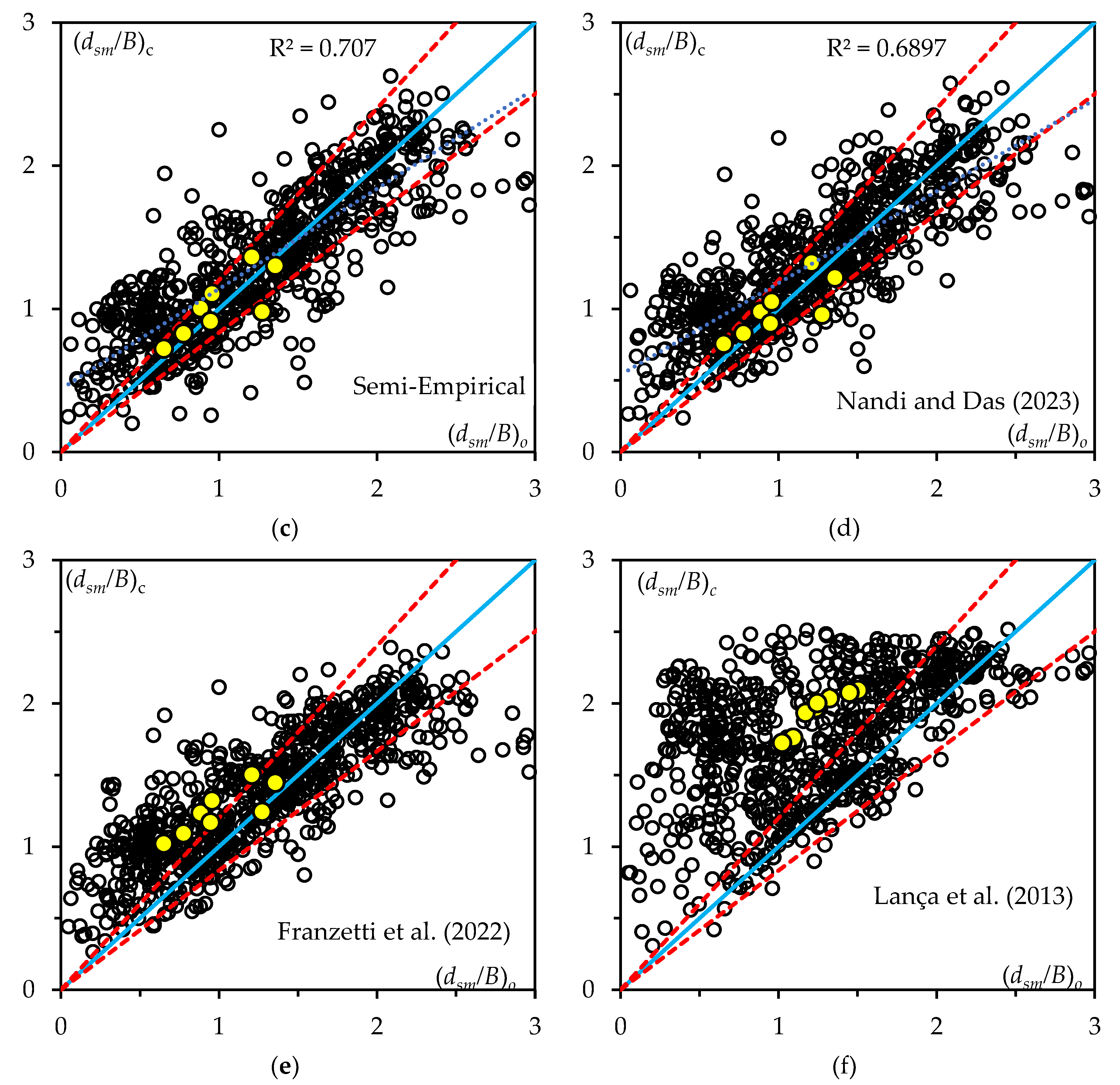

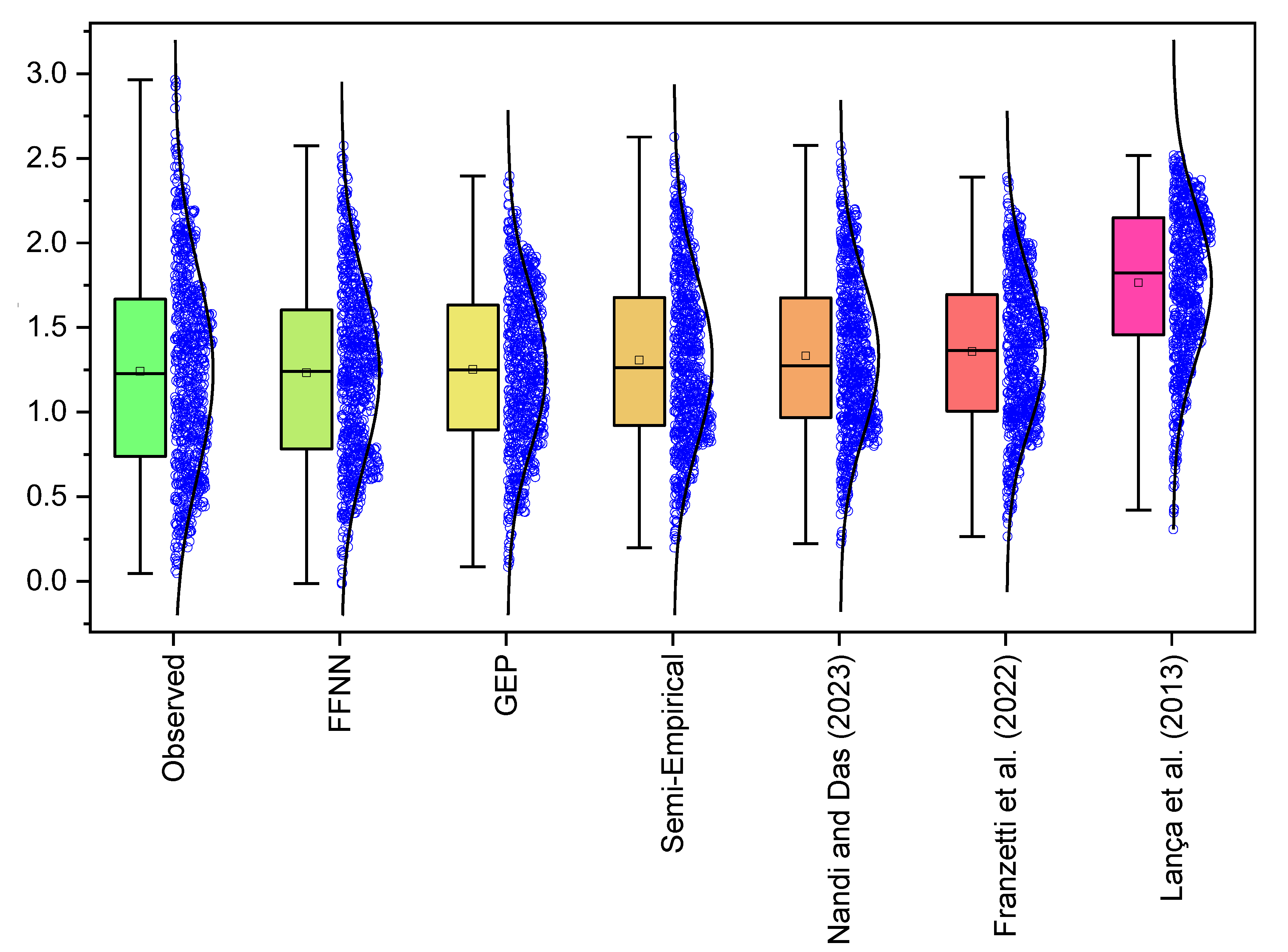

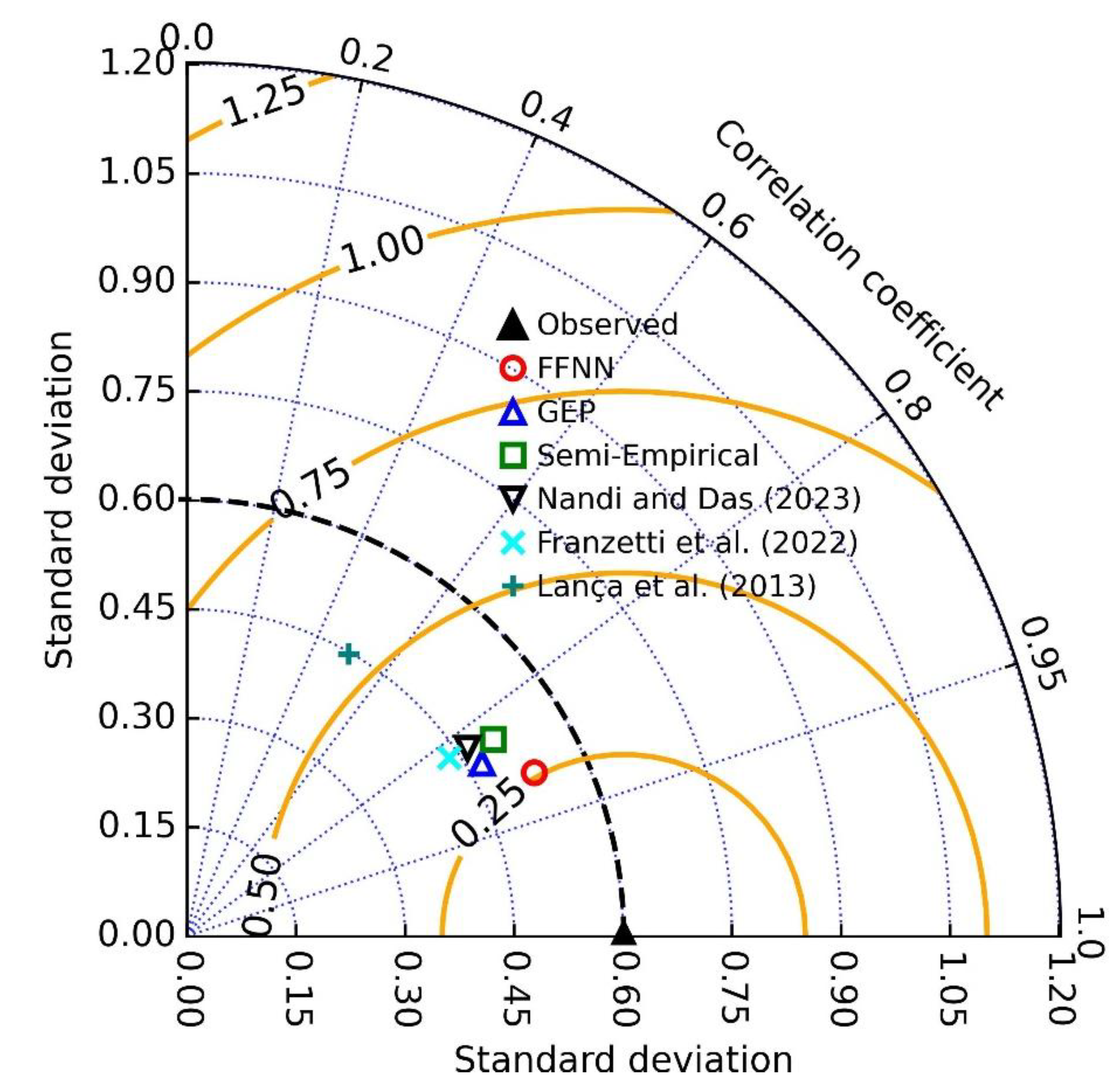

3.3. Evaluation of Models/Formulas

3.4. Overall Discussion

3.5. Uncertainty Analysis

4. Conclusions

- o Two additional parameters, B/W and F, significantly influence the dsm prediction within ranges from 0.1 to 0.5 and 0.08 to 0.28, respectively.

- o The FFNN achieved the highest performance in both testing (CD = 0.790, NSE = 0.783, MBE = -0.039, and RMSE = 0.289) and validation (CD = 0.773, NSE = 0.767, MBE = -0.040, and RMSE = 0.266. In comparison, the semi-empirical formula and the GEP model.

- o Newly developed FFNN models provide 18.6% more accuracy in terms of CD and 15% in terms of Pin (%) predictions compared to the most accurate literature formula.

- o The present study (GEP) formula provides 7.7% better CD compared to the existing best empirical formula. It gave steady and reliable results, with very little difference in performance measures across calibration, validation. This consistency shows its reliability across various datasets.

- o The present study (Semi-empirical) formula outperformed all the existing literature formulas.

- o Furthermore, the uncertainty analysis performed shows that FFNN gives the best results with the least margin of error (0.018) and the narrowest computation uncertainty band (0.037).

Supplementary Materials

| B | Pier diameter (m) |

| B/D50 | Sediment coarseness (–) |

| B/W | Constriction ratio (–) |

| D50 | Median diameter of sand (m) |

| ds | Scour depths (m) |

| dse | Equilibrium scour depth (m) |

| dsm | Maximal scour depth (m) |

| F | Flow Froude number (–) |

| g | Gravitational acceleration (m/s2) |

| H | Flow depth (m) |

| H/B | Flow shallowness (–) |

| R | Flow Reynolds number (–) |

| Rh | Hydraulic radius (m) |

| Ss | Bed slope (°) |

| t | Time (s) |

| tV/BΔ0.5 | Dimensionless time (–) |

| V | Flow velocity (m/s) |

| V⁎c | Critical shear velocity (m/s) |

| V/Vc | Flow intensity (–) |

| Vc | Critical flow velocity (m/s) |

| Δ | Relative density parameter of sand (–) |

| µ | Dynamic viscosity (Ns/m2) |

| Θc | Critical shields parameters (–) |

| ρf: | Water density (kg/m3) |

| ρs | Sediment density (kg/m3) |

| σ | Sediment gradation (–) |

| τo | Bed shear stress (N/m2) |

| τoc | Critical bed shear stress (N/m2) |

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richardson, E.V.; Davis, S.R. Evaluating scour at bridges. National Highway Institute (US): A Review on Estimation Methods of Scour Depth Around Bridge Pier 201. 2001.

- Devi, S.; Barbhuiya, A.K. Bridge pier scour in cohesive soil: a review. Sādhanā. 2017, 42, 1803–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, X.; Liang, F. A review of bridge scour: mechanism, estimation, monitoring and countermeasures. Nat. Hazards. 2017, 87, 1881–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouallali, A.; Taleb, A. Scour depth prediction around bridge piers of various geometries using advanced machine learning and data augmentation techniques. Transportation Geotechnics. 2025, 51, 101537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, B.W.; Sutherland, A.J. Design Method for Local Scour at Bridge Piers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1988, 114, 1210–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.M.; Miller, J.W. Live-Bed Local Pier Scour Experiments. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2006, 132, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneson, L.A.; Zevenbergen, L.W.; Lagasse, P.F.; Clopper, P. E. Evaluating scour at bridges. Hydraulic Engineering Circular no 18. Washington D.C., US. 2012.

- Das, S.; Mazumdar, A. Comparison of kinematics of horseshoe vortex at a flat plate and different shaped piers. Int. J. Fluid Mech. Res. 2015, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Mazumdar, A. Evaluation of hydrodynamic consequences for horseshoe vortex system developing around two eccentrically arranged identical piers of diverse shapes. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 2300–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Das, S.; Jaman, H.; Mazumdar, A. Impact of upstream bridge pier on the scouring around adjacent downstream bridge pier. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2019, 44, 4359–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, B.W.; Chiew, Y.M. Time scale for local scour at bridge piers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1999, 125, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveto, G.; Hager, W.H. Temporal evolution of clear-water pier and abutment scour. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2002, 128, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lança, R.M.; Fael, C.S.; Maia, R.J.; Pêgo, J.P.; Cardoso, A.H. Clear-water scour at comparatively large cylindrical piers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2013, 139, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzetti, S.; Radice, A.; Rebai, D.; Ballio, F. Clear-water scour at circular piers: A new formula fitting laboratory data with less than 25% deviation. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2022, 148, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, B.; Das, S. Identify most promising temporal scour depth formula for circular piers proposed over last six decades. Ocean Eng. 2023, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, F.; Nago, H. Design method of time-dependent local scour at circular bridge pier. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2003, 129, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, B.; Das, S. Equation for time-dependent local scour at pier-like structures with eccentric in-line arrangements. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Water Manag. 2024, 177, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, J.; Guan, D.; Yuan, S.; Tang, L.; Zhang, H. Process-based design method for pier local scour depth under clear-water condition. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2023, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikar, R.V.; Dey, S. Clear-water scour at bridge piers in fine and medium gravel beds. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2005, 32, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Das, R.; Mazumdar, A. Circulation characteristics of horseshoe vortex in scour region around circular piers. Water Sci. Eng. 2013, 6, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Sharma, P.K.; Ahmad, Z.; Karna, N. Maximum scour depth around bridge pier in gravel bed streams. Nat. Hazards 2018, 91, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, K.; Khozani, Z.S.; Mao, L. A comparison between advanced hybrid machine learning algorithms and empirical equations applied to abutment scour depth prediction. J. Hydrol. 2021, 596, 126100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, G.; Kumar, M. Experimental study of the local scour around the two piers in the tandem arrangement using ultrasonic ranging transducers. Ocean Eng. 2022a, 266, 112838. [CrossRef]

- Devi, G.; Kumar, M. Characteristics assessment of local scour encircling twin bridge piers positioned side by side (SbS). Sādhanā 2022b, 47, 109. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Goyal, M.K.; Deshpande, V.; Agarwal, M. Estimation of time-dependent scour depth around circular bridge piers: application of ensemble machine learning methods. Ocean Eng. 2023, 270, 113611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, B.; Patel, G.; Das, S. Prediction of maximum scour depth at clear water conditions: Multivariate and robust comparative analysis between empirical equations and machine learning approaches using extensive reference metadata. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 354, 120349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, B.; Das, S. Predict max scour depths near two-pier groups using ensemble machine learning models and visualize feature importance with partial dependence plots and SHAP. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2024, 39(2), 04025007. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, B.; Das, S. Developing new equations for maximum scour depth near tandem, side-by-side, and eccentric piers. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2025, e–First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRC-78. Standard Specifications & Code of Practice for Road Bridges, Section VII—Foundation & Substructure (Revised Edition). 2014.

- Yang, Y.; Melville, B.W.; Sheppard, D.M.; Shamseldin, A.Y. Live-bed scour at wide and long-skewed bridge piers in comparatively shallow water. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2019, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, A.R.; Gabr, M.A.; Montoya, B.M.; Ortiz, A.C. Local scour around bridge abutments: Assessment of accuracy and conservatism. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, G. Stable channels in alluvium. Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers 1930, 229, 259–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, S.C. Maximum depth of scour at heads of guide banks and groynes, pier noses, and downstream of bridges—the behavior and control of rivers and canals. Poona, India, Indian Waterways Experimental Station 1949, pp. 327–348.

- Kothyari, U.C.; Hager, W.H.; Oliveto, G. Generalized approach for clear-water scour at bridge foundation elements. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2007, 133, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayasree, B.A.; Eldho, T.I. A modification to the Indian practice of scour depth prediction around bridge piers. Curr. Sci. 2021, 120, 1875–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Posada, G.L.; Nordin, C.F. Pier scour equations used in the People’s Republic of China. Report FHWA-SA-93-076, 1993, U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Washington, D.C., U.S.

- Ansari, S.A.; Qadar, A. Ultimate depth of scour around bridge piers. In: Proc. ASCE Nat. Hydraul. Conf., 1994, Buffalo, New York, pp. 51–55.

- Larras, J. Profondeurs maximales d’érosion des fonds mobiles autour des piles en rivière. Ann. Ponts Chaussees 1963, 133, 411–424. [Google Scholar]

- Breusers, H.N.C. Scour around drilling platforms. Bull. Hydraul. Res. 1965, 19, 276. [Google Scholar]

- Neil, C.R. Guide to Bridge Hydraulics. 1973, Roads and Transportation Assoc. of Canada, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Canada, p. 191.

- Melville, B. W. Pier and abutment scour: Integrated approach. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1997, 123, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudio, R.; Tafarojnoruz, A. ; Bartolo De S, Sensitivity analysis of bridge pier scour depth predictive formulae. J. Hydroinform. 2013, 15, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabert, J.; Engeldinger, P. Étude des affouillements autour des piles de ponts. Technical Reports, [In French.] Laboratoire National d’Hydraulique, Chatou, France, 1956.

- Benedict, S. T.; Caldwell, A. W. A pier-scour database: 2,427 field and laboratory measurements of pier scour. US Geological Survey Data Series, 2014, 845, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D. M.; Melville, B.; Demir, H. Evaluation of existing equations for local scour at bridge piers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2014, 140, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes, C.; Brocchini, M. Local scour around structures and the phenomenology of turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 2015, 779, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonkeman, J. K.; Basson, G. R. Evaluation of empirical equations to predict bridge pier scour in a non-cohesive bed under clear-water conditions. J. South Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. 2019, 61, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscarella, F.; Gaudio, R.; Manes, C. Near-bed eddy scales and clear-water local scouring around vertical cylinders. J. Hydraul. Res. 2020, 58, 968–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCHRP. Scour at Wide Piers and Long Skewed Piers. Authored by Sheppard, D. M., Demir, H., Melville, B. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP), Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Ettema, R.; Constantinescu, G.; Melville, B. W. Flow-field complexity and design estimation of pier-scour depth: Sixty years since Laursen and Toch. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2017, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Li, J.; Chen, Q. Applicability analysis of pier-scour equations in the field: Error analysis by rationalizing measurement data. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2018, 144(8), 04018050. [CrossRef]

- Lança, R.; Fael, C.; Cardoso, A. H. Assessing equilibrium clear water scour around single cylindrical piers. River Flow, 2010, pp. 1207–1214.

- Blench, T.; Bardley, J. N.; Joglekar, D. V. Discussion of scour at bridge crossings. Trans. ASCE 1962, 127, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. Discussion of scour at bridge crossings, by E. M. Laursen. Trans. ASCE 1962, 127, 198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H. W.; Schneider, V. R.; Karaki, S. S. Mechanics of local scour. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards, Institute for Applied Technology, Fort Collins, Colorado, 1966.

- Lee, S. O.; Sturm, T. W. Effect of sediment size scaling on physical modeling of bridge pier scour. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2009, 135, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, R.; Melville, B. W.; Constantinescu, G. Evaluation of bridge scour research: Pier scour processes and predictions. Washington, DC, USA: Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, 2011.

- Hassan, W.H.; Jalal, H.K. Prediction of the depth of local scouring at a bridge pier using a gene expression programming method. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, P.; Manekar, V. L. Comprehensive approach for scour modelling using artificial intelligence. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2023, 41, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eini, N.; Bateni, S. M.; Jun, C.; Heggy, E.; Band, S. S. Estimation and interpretation of equilibrium scour depth around circular bridge piers by using optimized XGBoost and SHAP. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2023, 17, 2244558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini, S.; Roshni, T. Application of GEP, M5-TREE, ANFIS, and MARS for predicting scour depth in live bed conditions around bridge piers. J. Soft Comput. Civ. Eng. 2023, 7, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadianfar, I.; Jamei, M.; Karbasi, M.; Sharafati, A.; Gharabaghi, B. A novel boosting ensemble committee-based model for local scour depth around non-uniformly spaced pile groups. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 3439–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Karbasi, M.; Jamei, M.; Malik, A.; Pu, J. H. A comprehensive experimental and computational investigation on estimation of scour depth at bridge abutment: Emerging ensemble intelligent systems. J. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 37, 3745–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Das, B.S.; Devi, K.; Khuntia, J.R. ANFIS- and GEP-based model for prediction of scour depth around bridge pier in clear-water scouring and live-bed scouring conditions. J. Hydroinform. 2023, 25, 1004–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranwal, A.; Das, B. S. Live-bed scour depth modelling around the bridge pier using ANN-PSO, ANFIS, MARS, and M5Tree. Water Resour. Manage. 2024, 38, 4555–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Oliveto, G.; Deshpande, V.; Agarwal, M.; Rathnayake, U. Forecasting of time-dependent scour depth based on bagging and boosting machine learning approaches. J. Hydroinform. 2024, 26, 1906–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknam, A.; Heidarnejad, M.; Masjedi, A.; Bordbar, A. Data-based models to investigate protective piles effects on the scour depth about oblong-shaped bridge pier. Results in Eng. 2024, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, R. Scour at bridge piers. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Auckland, 1980.

- Mignosa, P. Fenomeni di erosione locale alla base delle pile dei ponti. [In Italian.] M.Sc. thesis, Politecnico di Milano, 1980.

- Chiew, Y. M. Local scour at bridge piers. Rep. No. 355, Auckland, New Zealand: School of Engineering, University of Auckland, 1984.

- Franzetti, S.; Larcan, E.; Mignosa, P. Erosione alla base di pile circolari di ponte: Verifica sperimentale di esistenza di una situazione di equilibrio. [In Italian.] Idrotecnica 1989, 3, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hancu, S.; Predescu, L. Experimental results on local scour around bridge piers in free surface water currents and pressurized air currents. In: Proceedings 23rd Congress of the International Association for Hydraulic Research (IAHR), Madrid, Spain, 1989.

- Dargahi, B. Controlling mechanism of local scouring. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1990, 116, 1197–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanmaz, A. M.; Altinbilek, H. D. Study of time-dependent local scour around bridge piers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1991, 117, 1247–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, W. H. Load scour around piers. Annual Rep., 1995.

- Chiew, Y. M. Mechanics of riprap failure at bridge piers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1995, 121, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Bose, S. K.; Sastry, G. L. Clear water scour at circular piers: A model. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1995, 121, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W. Y.; Lai, J. S.; Yen, C. L. Evolution of scour depth at circular bridge piers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2004, 130, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D. M.; Odeh, M.; Glasser, T. Large scale clear-water local pier scour experiments. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2004, 130, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, J. A. Experimental study on local scour around bridge piers in rivers. WIT Trans. Ecol. 2005, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, P. D. Time development of local scour at a bridge pier fitted with a collar. M.Sc. thesis, Dept. of Civil and Geol. Environ. Eng., Univ. of Saskatchewan. Ames, IA: Iowa Highway Research Board, 2006.

- Ettema, R.; Kirkil, G.; Muste, M. Similitude of large-scale turbulence in experiments on local scour at cylinders. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2006, 132, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, O.; Pfleger, F.; Zanke, U. Characteristics of developing scour-holes at a sand embedded cylinder. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2008, 23, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosronejad, A.; Kang, S.; Sotiropoulos, F. Experimental and computational investigation of local scour around bridge piers. Adv. Water Resour. 2012, 37, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, M. Predictive competence of existing bridge pier scour depth predictors. Eur. Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2013, 2, 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ettmer, B.; Orth, F.; Link, O. Live-bed scour at bridge piers in a lightweight polystyrene bed. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2015, 141, 04015017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalmani, Y. A.; Hakimzadeh, H. Experimental investigation of scour around semi-conical piers under steady current action. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2015, 19, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lança, R.; Simarro, G.; Fael, C. M. S.; Cardoso, A. H. Effect of viscosity on the equilibrium scour depth at single cylindrical piers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2016, 142, 06015022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, A. O.; Bombar, G.; Arkis, T.; Guney, M. S. Study of the time-dependent clear water scour around circular bridge piers. J. Hydrol. Hydromech. 2017, 65, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, O.; Henríquez, S.; Ettmer, B. Physical scale modelling of scour around bridge piers. J. Hydraul. Res. 2019, 57, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Zakwan, M.; Sharma, P. K.; Ahmad, Z. Multiple linear regression and genetic algorithm approaches to predict temporal scour depth near circular pier in non-cohesive sediment. ISH J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 26, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omara, H.; Abdeelaal, G. M.; Nadaoka, K.; Tawfik, A. Developing empirical formulas for assessing the scour of vertical and inclined piers. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2020, 38, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Pu, J. H.; Pourshahbaz, H.; Khan, M. A. Reduction of scour around circular piers using collars. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2022, 15, e12812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C. Gene Expression Programming: a New Adaptive Algorithm for Solving Problems. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C. Gene expression programming: Mathematical modeling by an artificial intelligence. Vol. 21, Springer (Springer Berlin, Heidelberg), 2006.

- Milukow, H. A.; Binns, A. D.; Adamowski, J.; Bonakdari, H.; Gharabaghi, B. Estimation of the Darcy–Weisbach friction factor for ungauged streams using Gene Expression Programming and Extreme Learning Machines. J. Hydrol. 2019, 568, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Das, B. S.; Devi, K.; Khuntia, J. R. ANFIS-and GEP-based model for prediction of scour depth around bridge pier in clear-water scouring and live-bed scouring conditions. J. Hydroinform. 2023, 25, 1004–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanmohammadi, S.; Cruz, M. G.; Golafshani, E. M.; Bai, Y.; Arashpour, M. Application of artificial intelligence methods to model the effect of grass curing level on spread rate of fires. Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 173, 105930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, N. M.; Tran, A. D.; Dang, T. D. ANN optimized by PSO and Firefly algorithms for predicting scour depths around bridge piers. Eng. Comput. 2021, 37, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Jamei, M.; Ahmadianfar, I.; Karbasi, M.; Lodhi, A. S.; Chu, X. Assessment of scouring around spur dike in cohesive sediment mixtures: A comparative study on three rigorous machine learning models. J. Hydrol. 2022, 606, 127330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Kim, C.; Kim, D. H. Flood prediction using nonlinear instantaneous unit hydrograph and deep learning: A MATLAB program. Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 175, 105974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M. A.; Alam, J.; Muzzammil, M. Application of ANN to model scour at downstream of bed sills. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancu, S. On the estimation of local scour in the bridge piers zone. In Proceedings 14th Congress of the International Association for Hydraulic Research (IAHR), Vol. 3, pp. 299–313. Madrid, Spain, 1971.

- Breusers, H. N. C.; Nicollet, G.; Shen, H. W. Local scour around cylindrical piers. J. Hydraul. Res. 1977, 15, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, D. C. Analysis of onsite measurements of scour at piers. Proc. ASCE National Conference on Hydraulic Engineering, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. U.; Choi, B. Prediction of time-dependent local scour around bridge piers. Water Environ. J. 2016, 30(1–2), 14–21. [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Fard, M. Y.; Chattopadhyay, A. Investigation of a bridge pier scour prediction model for safe design and inspection. J. Bridge Eng. 2015, 20, 04014088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. C. Maximum clear-water scour around circular piers. J. Hydraul. Div. 1981, 107, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, B. W.; Coleman, S. E. Bridge scour, Water Resources Publications, Colo, 2000.

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

| Chromosomes | 40 | Tail Size | 11 |

| Genes | 3 | Dc Size | 11 |

| Head Size | 10 | Gene Size | 32 |

| Linking Function | Multiplication (×) | ||

| Function used | Symbol | Weight | Arity |

| Addition | + | 4 | 2 |

| Subtraction | - | 4 | 2 |

| Multiplication | * | 4 | 2 |

| Division | / | 1 | 2 |

| Exponential | Exp | 1 | 1 |

| Natural logarithm | Ln | 1 | 1 |

| x to the power of 2 | X2 | 1 | 1 |

| Cube root | 3Rt | 1 | 1 |

| Arctangent | Atan | 1 | 1 |

| Minimum of 2 inputs | Min2 | 1 | 2 |

| Maximum of 2 inputs | Max2 | 1 | 2 |

| Average of 2 inputs | Avg2 | 4 | 2 |

| Hyperbolic tangent | Tanh | 1 | 1 |

| Complement | NOT | 1 | 1 |

| Inverse | Inv | 1 | 1 |

| Genetic Operator | Value | Genetic Operator | Value |

| Custom Mutation | 0.0012 | Gene Recombination | 0.00755 |

| Function Insertion | 0.00206 | One-Point Recombination | 0.00277 |

| Leaf Mutation | 0.00546 | Two-Point Recombination | 0.00277 |

| Biased Leaf Mutation | 0.00546 | Gene Recombination | 0.00277 |

| Conservative Mutation | 0.00364 | Gene Transposition | 0.00277 |

| Conservative Function Mutation | 0.00546 | Random Chromosomes | 0.0026 |

| Permutation | 0.00546 | Random Cloning | 0.00102 |

| Conservative Permutation | 0.00546 | Best Cloning | 0.0026 |

| Biased Mutation | 0.00546 | RNC Mutation | 0.00206 |

| Inversion | 0.00546 | Constant Fine-Tuning | 0.00206 |

| Tail Mutation | 0.00546 | Constant Range Finding | 0.000085 |

| Tail Inversion | 0.00546 | Constant Insertion | 0.00123 |

| IS Transposition | 0.00546 | Dc Mutation | 0.00206 |

| RIS Transposition | 0.00546 | Dc Inversion | 0.00546 |

| Stumbling Mutation | 0.00141 | Dc IS Transposition | 0.00546 |

| Recombination | 0.00755 | Dc Permutation | 0.00546 |

| Combination | Gene Number | Constant | Value |

| G1C1 | G1 | C1 | -0.0379 |

| G2C9 | G2 | C9 | 0.6467 |

| G2C5 | G2 | C5 | -5.9929 |

| G3C9 | G3 | C9 | -18.7964 |

| G3C2 | G3 | C2 | 0.8306 |

| Model | Reference datasets | Performance indicators | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | NSE | MBE | RMSE | Pin (%) | ||

| Empirical | Training/calibration data (80%) | 0.694 | 0.684 | 0.061 | 0.271 | 60.848 |

| Validation data (20%) | 0.756 | 0.750 | 0.089 | 0.301 | 61.935 | |

| Present Exp. data | 0.651 | 0.637 | 0.020 | 0.140 | 87.500 | |

| GEP | Training/calibration data (80%) | 0.743 | 0.738 | 0.018 | 0.246 | 61.301 |

| Validation data (20%) | 0.742 | 0.727 | -0.020 | 0.342 | 50.323 | |

| Present Exp. data | 0.737 | 0.603 | 0.060 | 0.147 | 77.778 | |

| FFNN | Training/calibration data (70%) | 0.834 | 0.833 | 0.005 | 0.249 | 65.677 |

| Validation data (15%) | 0.773 | 0.767 | -0.040 | 0.266 | 75.000 | |

| Test data (15%) | 0.790 | 0.783 | -0.039 | 0.289 | 64.655 | |

| Present Exp. data | 0.583 | 0.562 | -0.031 | 0.154 | 87.500 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).