Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

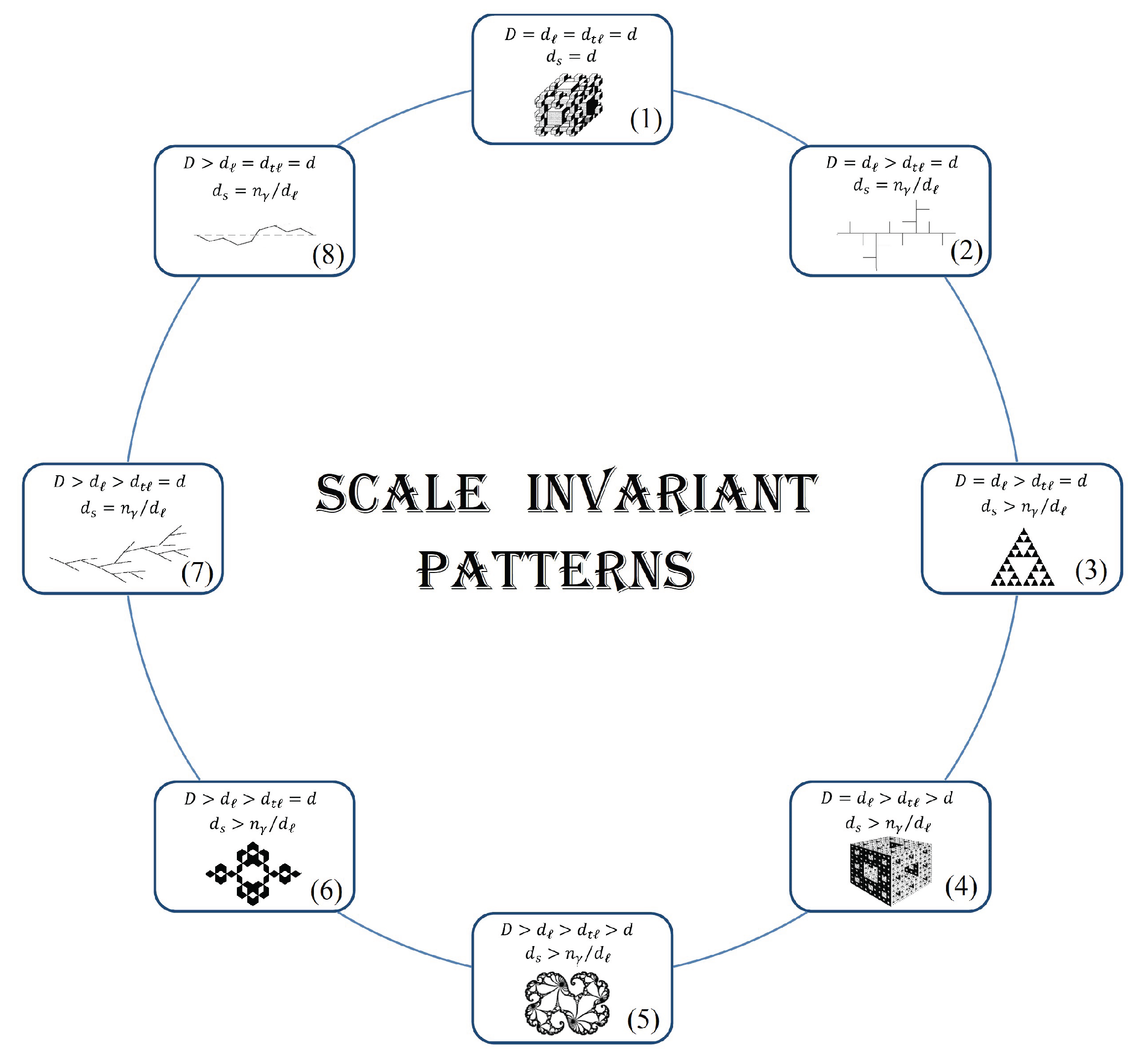

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Brief Excursion into the History of Fractal Geometry

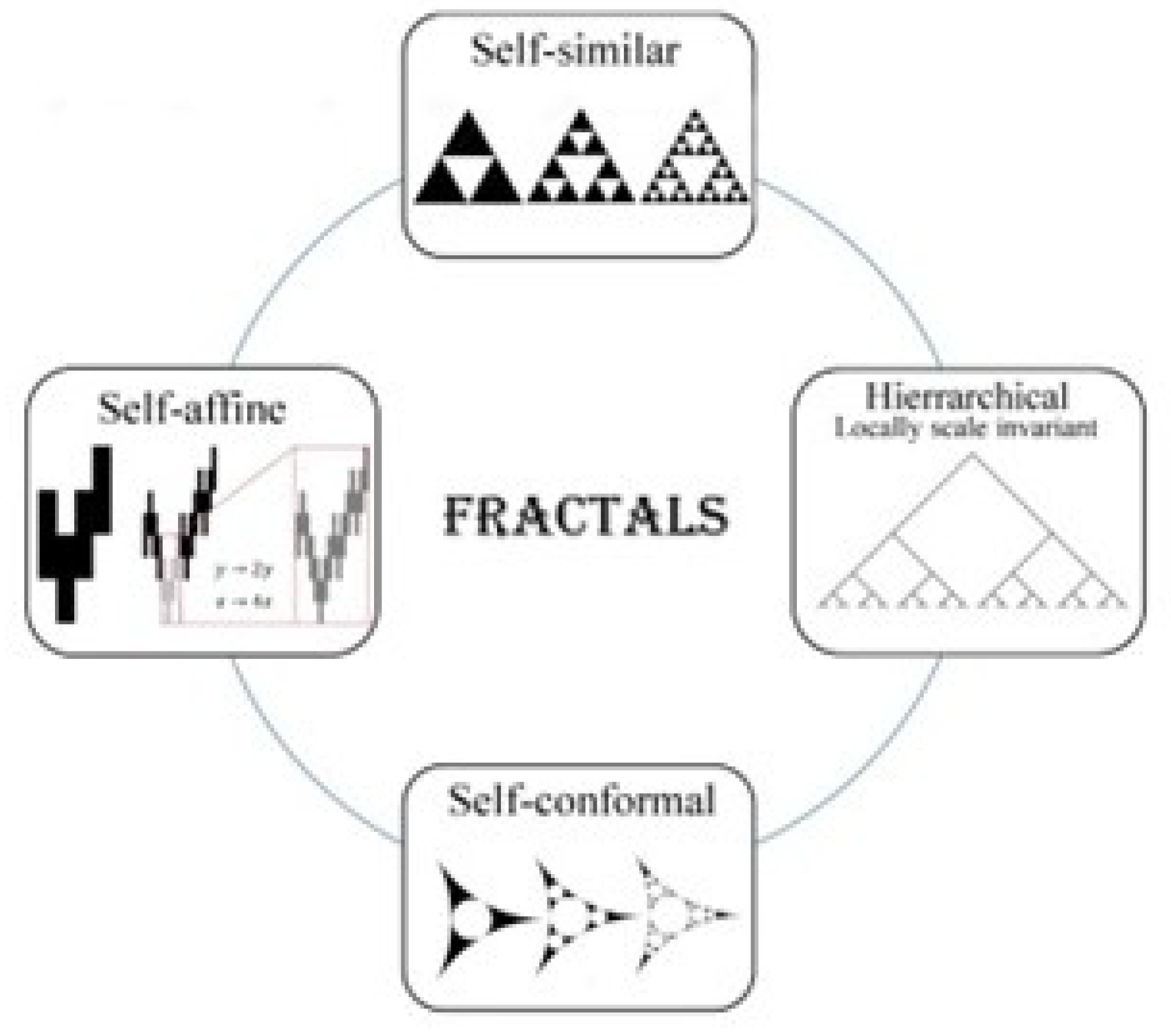

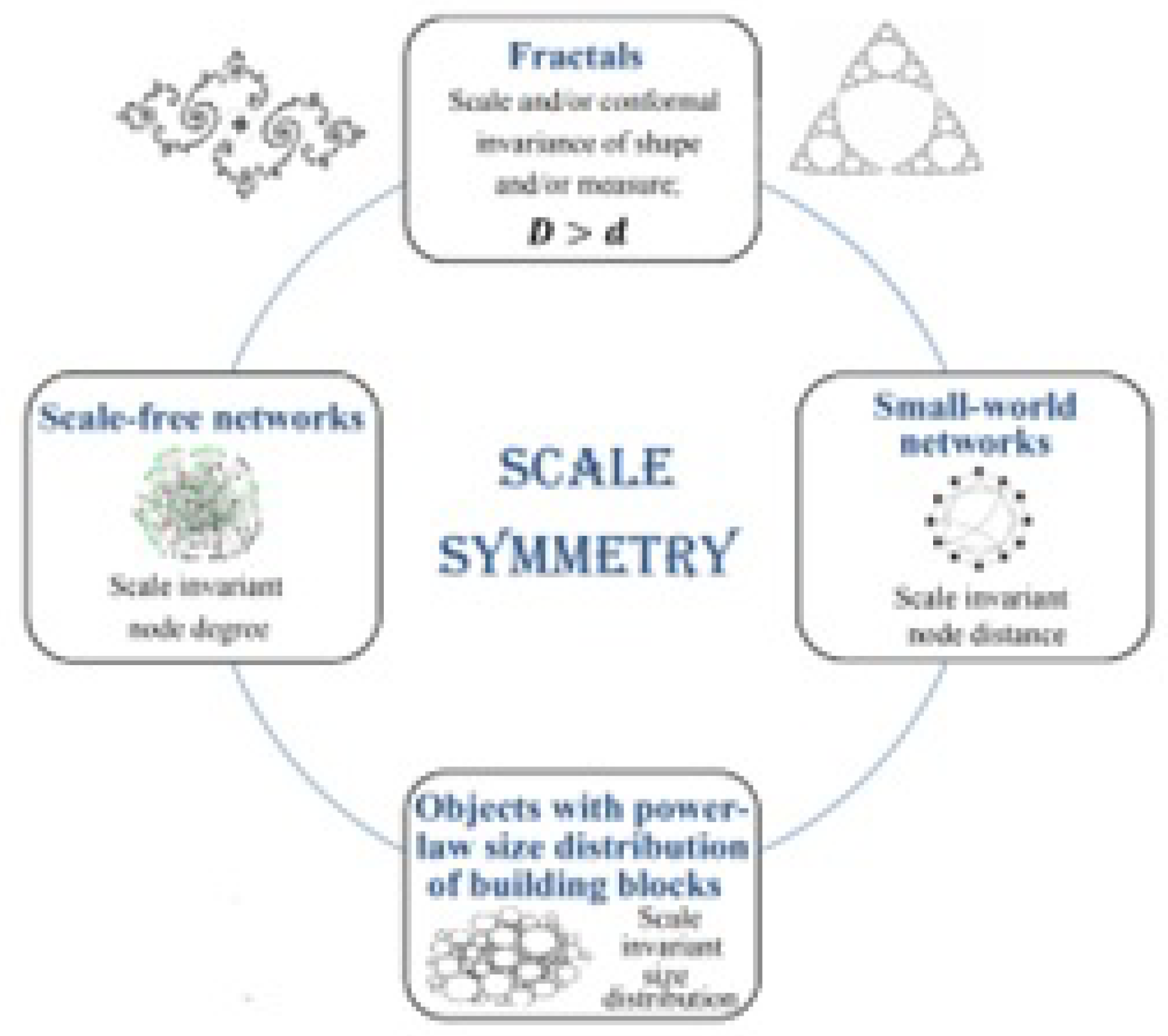

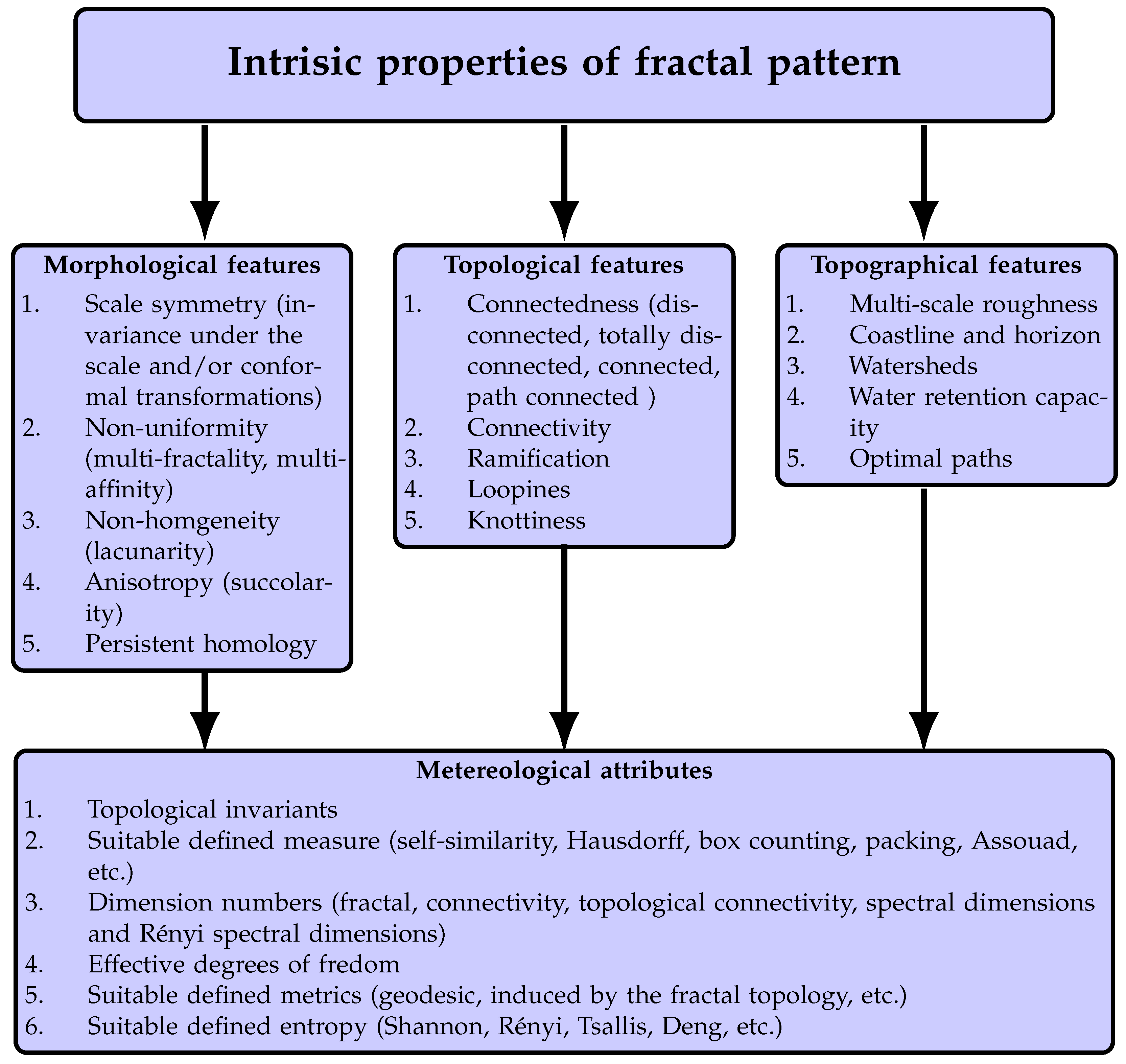

3. Conceptual Foundations of Fractal Geometry

- 1)

- handles the scale invariance of the Euclidean object ;

- 2)

- characterizes the object connectivity;

- 3)

- establishes the object ramification;

- 4)

- sets the maximum number of mutually orthogonal vectors in the object;

- 5)

- governs the Lebesgue measure and other Borel measures on Euclidean space;

- 6)

- determines the numbers of spatial and dynamic degrees of freedom of a point walker in the object

- 7)

- rules the statistics of thomogeneous Poisson point processes;

- 8)

- controls the vibrational dynamics of the object;

- 9)

- manages the information flow;

- 10)

- settles the values of universal exponents associated with critical phenomena.

4. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mandelbrot, B.B. Fractals: Form, Chance, and Dimension. Freeman: New York, 1977.

- Balankin, A.S., Patiño, J., Patiño, M. Inherent features of fractal sets and key attributes of fractal models. Fractals 2022, 30, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. Freeman: New York, 1982.

- Balankin, A.S. Fractional space approach to studies of physical phenomena on fractals and in confined low-dimensional systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 32, 109572. [CrossRef]

- Patino-Ortiz, J.; Martínez-Cruz, M.Á.; Esquivel-Patino, F.R.; Balankin, A.S. Morphological Features of Mathematical and Real-World Fractals: A Survey. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 440. [CrossRef]

- Patino-Ortiz, J.; Patino-Ortiz, M.; Martínez-Cruz, M.-Á.; Balankin, A.S. A Brief Survey of Paradigmatic Fractals from a Topological Perspective. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 597. [CrossRef]

- Nutu, C.S.; Axinte, T. Fractals. Origins and History. J. Marine Tech. Envir. 2022, 2, 48-51. [CrossRef]

- Chabert, J.L. Un demi-siecle de fractales: 1870-l920. Historia Mathematica 1990, 17(4), 339-365. [CrossRef]

- Debnath, L. A brief historical introduction to fractals and fractal geometry. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Tech. 2006, 37(1), 29-50. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, V.A. Historical aspects of fractal theory appearance. Physics of Wave Processes and Radio Systems 2021, 24(2), 113-126. [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.; Nanda, M.N.; Chowdary, M.S.; Sajid, M. Fractals: An Eclectic Survey, Part-I. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 89. [CrossRef]

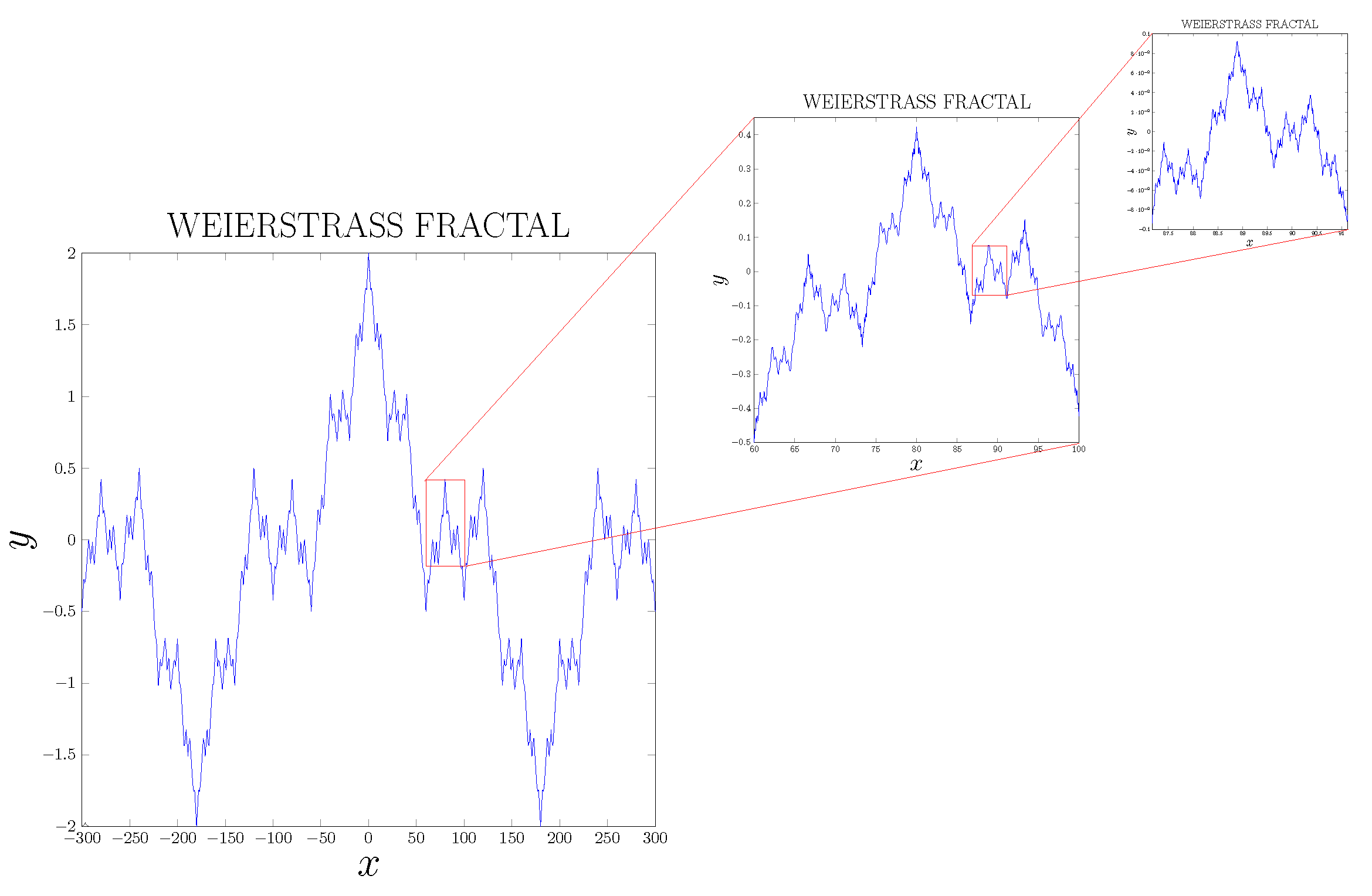

- Weierstrass, K. Über Continuirliche Functionen Eines Reellen Arguments, die für Keinen Werth des Letzteren Einen Bestimmten Differentialquotienten Besitzen. In: Siegmund-Schultze, R. (eds) Ausgewählte Kapitel aus der Funktionenlehre. Teubner-Archiv zur Mathematik, vol 9; Springer: Vienna, 1988. [CrossRef]

- Pinkus, A. Weierstrass and Approximation Theory. J. Approx. Theory 2000, 107, 1-66. [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M.; Ouchi, S. On the self-affinity of various curves. Physica D 1989, 38(1-3), 246-251. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A. S. Physics of fracture and mechanics of self-affine cracks. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1997, 57(2-3), 135-203. [CrossRef]

- Barański, K.; Bárány, B.; Romanowska, J. On the dimension of the graph of the classical Weierstrass function. Adv. Math. 2014, 265, 32-59. [CrossRef]

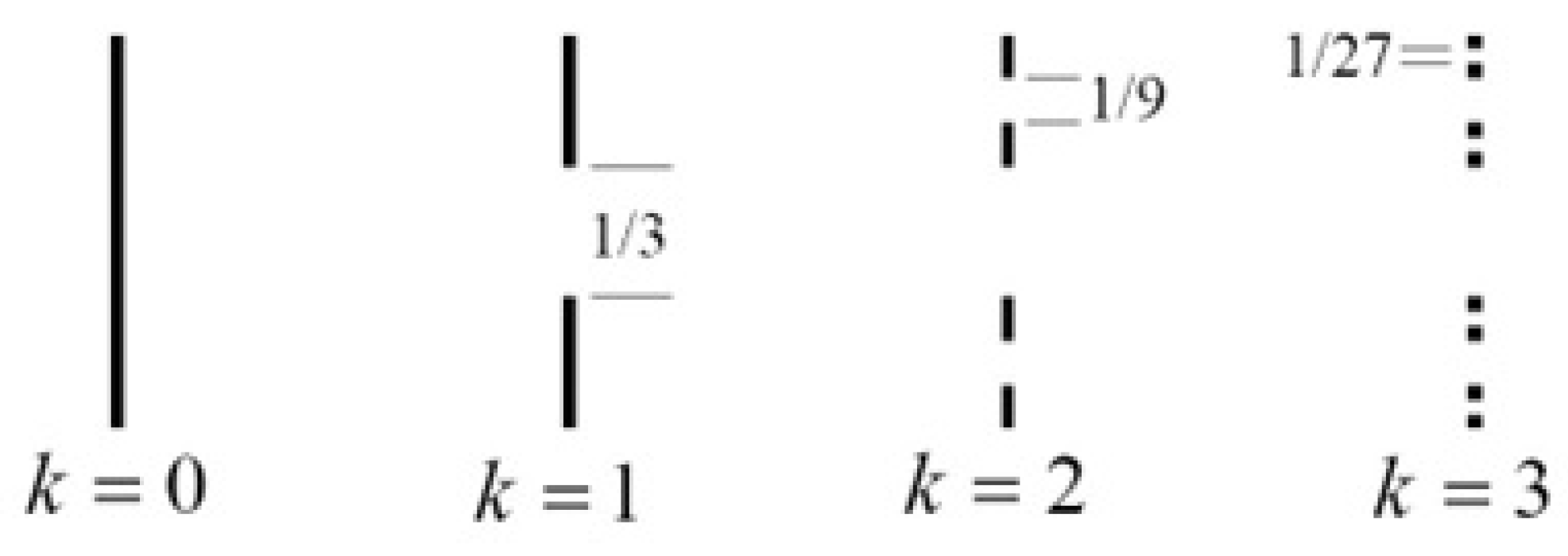

- Cantor, G. Uber unendliche, lineare Punktmannigfaltigkeiten V. Math. Ann. 1883, 21, 545–591, Reprinted in Cantor, G. Gesammelte Abhandlungen Mathematischen und Philosophischen Inhalts; Zermelo, E., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 165–209. [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.S. On the integration of discontinuous functions, Proc. London Math. Soc. 1875, 1, 140-153. [CrossRef]

- Fleron, J.F. A Note on the History of the Cantor Set and Cantor Function, Math. Mag. 1994, 67(2), 136-140. [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.B. A Course in Point Set Topology; Springer: New York, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A. S.; Bory-Reyes, J.; Luna-Elizarrarás, M. E.; Shapiro, M. Cantor-type sets in hyperbolic numbers. Fractals 2016, 24(04), 1650051. [CrossRef]

- Björn, A.; Björn, J.; Gill, J.T., Shanmugalingam, N. Geometric analysis on Cantor sets and trees. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 2017, 725, 63-114. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Mishra, J.; Nayak, S.R. Generation of Cantor sets from fractal squares: A mathematical prospective. J. Interdisciplinary Math. 2022, 25(3), 863-880. [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. Self-inverse fractals, Apollonian nets, and soap. In: Fractals and Chaos. Springer, New York, NY, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Yong-ping, Z.; He-ping, X. Fractal geometry derived from geometric inversion. Appl. Math. Mech. 1990, 11, 1075-1079. [CrossRef]

- Borodich, F.M. Parametric homogeneity and non-classical self-similarity. I. Mathematical background. Acta mechanica 1998, 131(1), 27-45. [CrossRef]

- Frame, M.; Cogevina, T. An infinite circle inversion limit set fractal. Comp. Graph. 2000, 24(5), 797-804. [CrossRef]

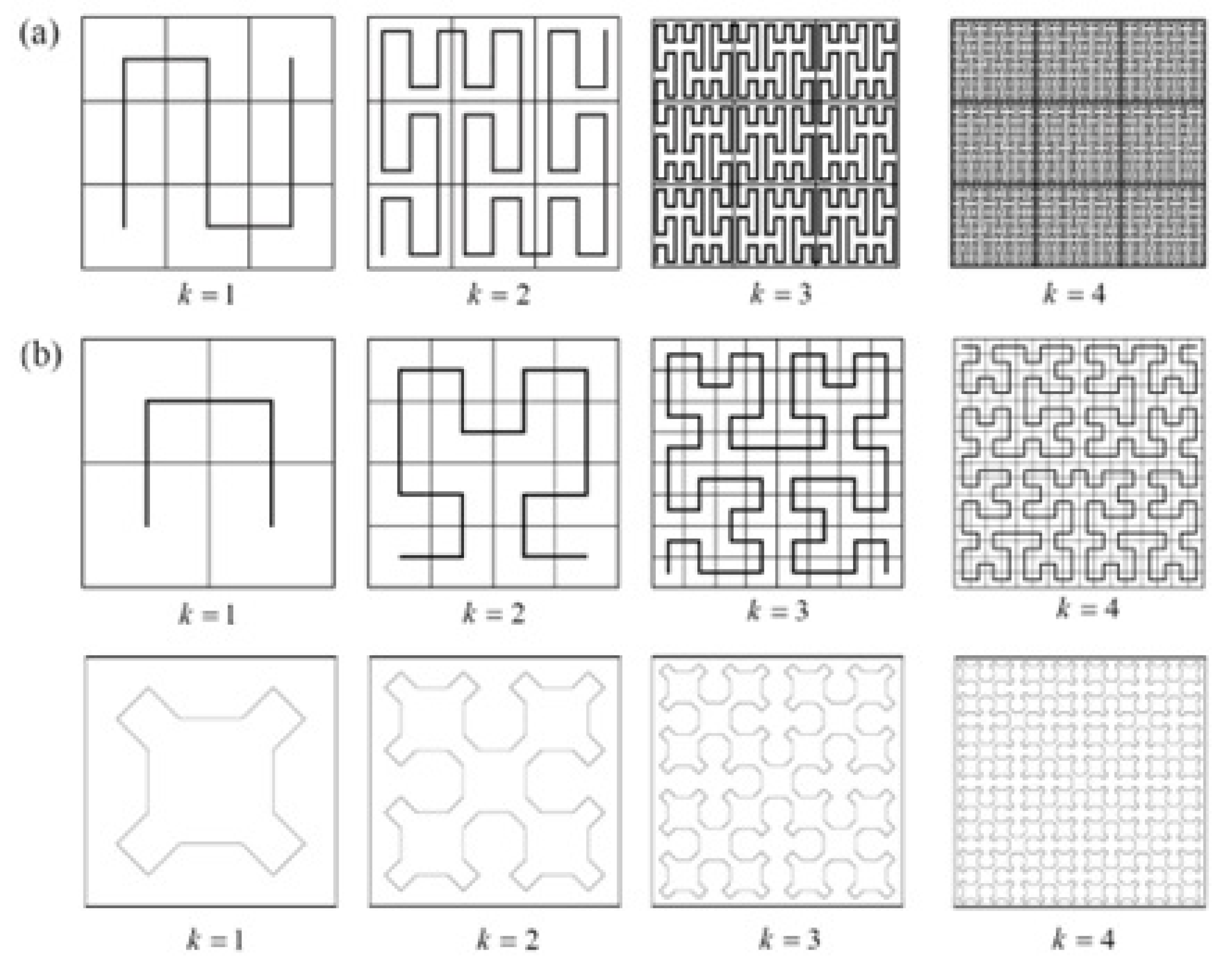

- Peano, G. Sur une courbe, qui remplit toute une aire plane, Mathematische Annalen 1890, 36, 157-160. Reprinted in Arbeiten zur Analysis und zur mathematischen Logik. Teubner-Archiv zur Mathematik, vol 13. Springer: Vienna, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, D. Uber die stetige Abbildung einer Linie auf ein Flăchenstuck. Mathematischc Annalen 1891, 38, 459-460. Reprinted in Dritter Band: Analysis · Grundlagen der Mathematik · Physik Verschiedenes. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1935. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bin, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z. Fractal scanning path generation and control system for selective laser sintering (SLS). Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2003, 43(3), 293-300. [CrossRef]

- Sagan, H. On the geometrization of the Peano curve and the arithmetization of the Hilbert curve. Int. J. Math. Education Sci. Tech. 1992, 23, 403-411. [CrossRef]

- Humke, P.D.; Huynh, K.V. Finding keys to the Peano curve. Acta Math. Hungar. 2022, 167, 255–277. [CrossRef]

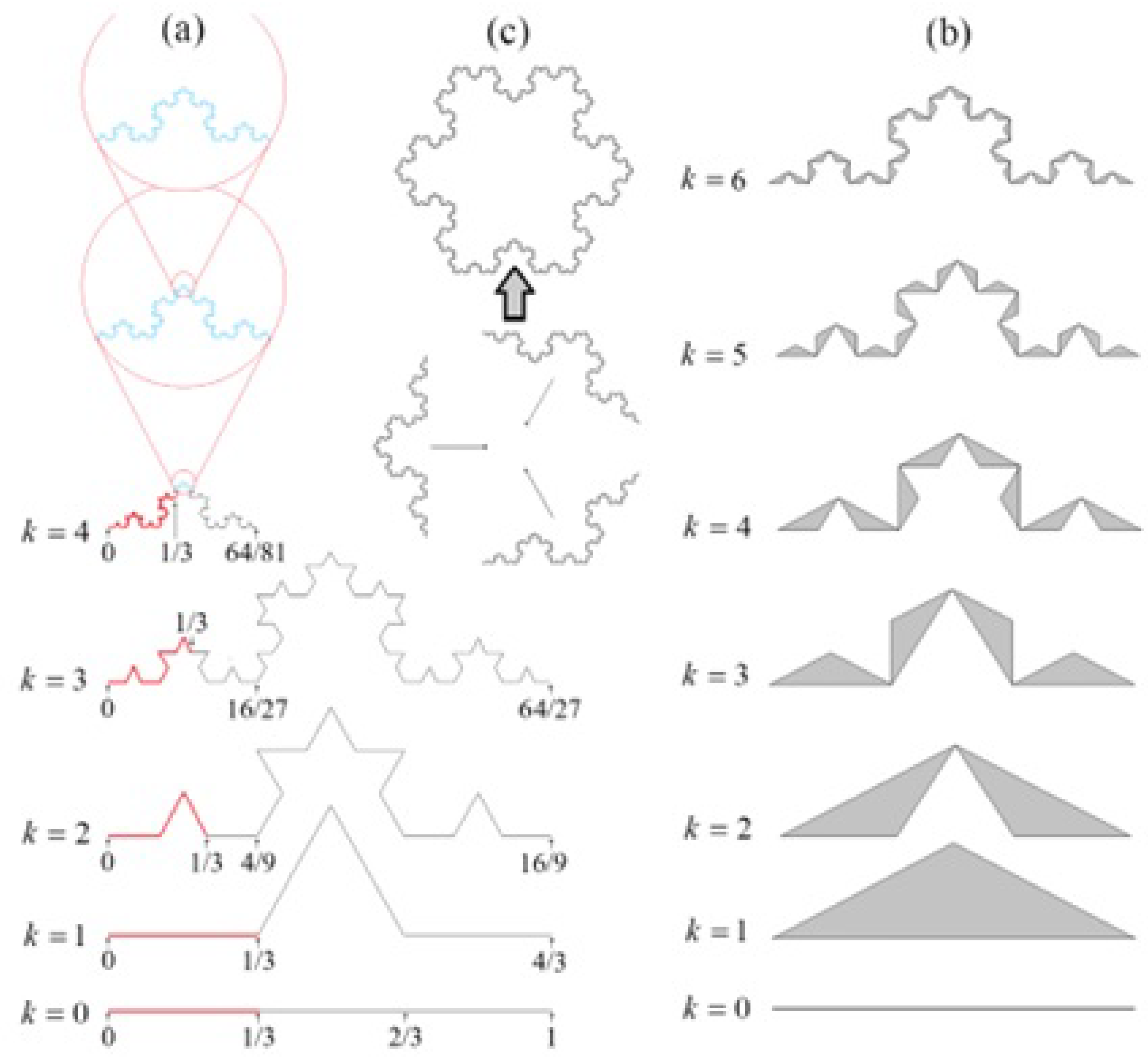

- von Koch, H. Sur un e courbe continue sans tangente, obtenue par une construction geometrique elementaire. Arkiv for Matematik, Astronomi och Fysik 1904, 1, 681 - 704.

- McCartney, M. Four variations on a fractal theme. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Tech. 2024, 55(9), 2374-2388. [CrossRef]

- Ri, S.I.; Drakopoulos, V.; Nam, S.M. Fractal interpolation using harmonic functions on the Koch curve. Fractal Fract. 2021, 5(2), 28. [CrossRef]

- Lyakhov, L.N.; Sanina, E.L. Differential and integral operations in hidden spherical symmetry and the dimension of the Koch curve. Math. Notes 2023, 113(3), 502-511. [CrossRef]

- Sierpifiski, W. Sur une nouvelle courbe continue qui remplit toute une aire plane. Bull Int. Acad. Sci. Cracovie A 1912, 462-478-.

- Nisha, P.S.A.; Hemalatha, S.; Sriram, S.; Subramanian, K.G. P Systems for Patterns of Sierpinski Square Snowflake Curve. Punjab Univ. J. Math. 2020, 52, 11–18. Available online: http://journals.pu.edu.pk/journals/index.php/pujm/article/viewArticle/3679.

- Alexander, D.S. Fatou and Julia. In: A History of Complex Dynamics. Aspects of Mathematics, vol. 24. Vieweg+Teubner Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, S. Consensus of Julia Sets. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 43. [CrossRef]

- Danca, MF.; Fečkan, M. Mandelbrot set and Julia sets of fractional order. Nonlinear Dyn. 2023, 111, 9555–9570. [CrossRef]

- Akhmet, M.; Fen, M.O.; Alejaily, E.M. Dynamics with chaos and fractals. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2020.

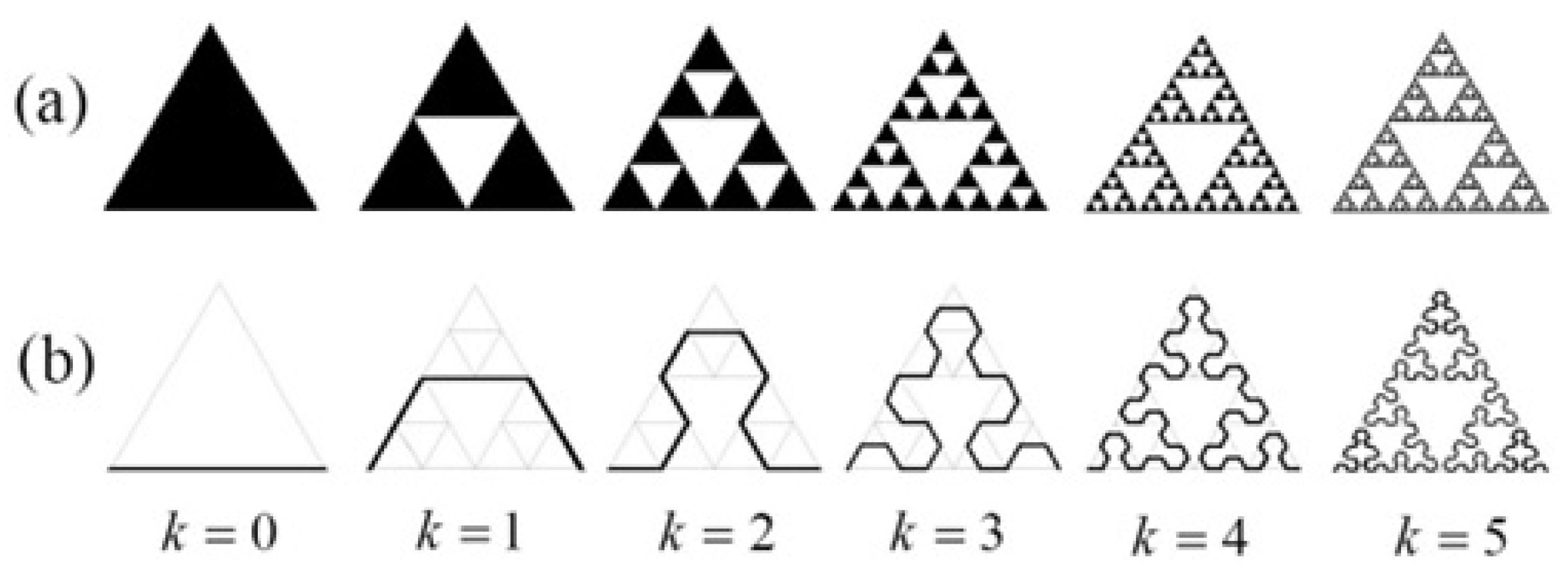

- Sierpinski, W. Sur une courbe dont tout point est un point de ramification. C. R. Acad. Paris 1915, 160, 302–305.

- Sierpifiski, W. On a curve every point of which is a point of ramification, Prace Mat. Fiz. 1916, 27, 77-86.

- W. Sierpifiski, Oeuvres Choisies, Warsaw: Pafiswowe Wydwnicto Naukowe, 1975.

- Martńez-Cruz, M.-Á.; Patiño-Ortiz, J.; Patiño-Ortiz, M.; Balankin, A.S. Some Insights into the Sierpinski Triangle Paradox. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 655. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I. Four Encounters with Sierpinski’s Gasket. Math. Intell. 1995, 17, 52–64. [CrossRef]

- Reiter, C.; With, J. 101 ways to build a Sierpinski triangle. ACM SIGAPL APL Quote Quad. 1997, 27, 8–16. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10385/1842.

- Luna-Elizarrarás, M.E.; Shapiro, M.; Balankin, A.S. Fractal-type sets in the four-dimensional space using bicomplex and hyperbolic numbers. Anal. Math. Phys. 2020, 10, 13. [CrossRef]

- Sierpinski, W. Sur une courbe cantorienne qui contient une image biunivoque et continue de toute courbe donnee. C. R. Acad. Paris1916, 162, 629–632.

- Menger, K.; Brouwer, L.E.J. “Allgemeine Räume und Cartesische Räume”. Zweite Mitteilung: “Ueber umfassendste n-dimensionale Mengen”. In Selecta Mathematica. Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2002; pp. 89–92. [CrossRef]

- Hausdorff, F. Dimension und auBeres Maß. Math. Ann. 1918, 79, 157–179. [CrossRef]

- Besicovitch, A.S. Sets of Fractional Dimensions (IV): On Rational Approximation to Real Numbers. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 1934, s1–s9, 126–131. [CrossRef]

- Besicovitch, A.S.; Ursell, H.D. Sets of Fractional Dimensions (V): On Dimensional Numbers of Some Continuous Curves. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 1937, s1–s12, 18–25. [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, A. Mathematical models for cellular interaction in development I. Filaments with one-sided inputs. J. Theor. Biol. 1968, 18, 280-315. [CrossRef]

- Oberguggenberger, M.; Ostermann, A. Fractals and L-Systems. In: Analysis for Computer Scientists. Undergraduate Topics in Computer Science. Springer: London, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B. Fractal Geometry in Nature: Applications in Physics and Mathematical Theory. Frontiers in Applied Physics and Mathematics 2024, 1(2), 129-145.

- Mandelbrot, B.B. How long is the coast of Britain? Statistical self-similarity and fractional dimension. Science 1967, 156, 636–638. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.E. Fractals and self-similarity. Indiana Univ. Math. J. 1981, 30, 713–747. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24893080.

- Barnsley, M.F. Fractals everywhere. Academic Press: Orlando, 1988.

- Alexander, S.; Orbach, R. Density of states on fractals: «fractons». J. Physique Lett. 1982, 43(17), 625-631. [CrossRef]

- Orbach, R. Dynamics of fractal networks. Science 1986, 231 814–819. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, H.E. Application of fractal concepts to polymer statistics and to anomalous transport in randomly porous media. J. Stat. Phys. 1984, 36, 843–860. [CrossRef]

- Falconer, K.S. Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications. Wiley: New York, 1990.

- Edgar, G. Classics on Fractals. Addison Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1993.

- Nakayama, T., Yakubo, K. Dynamical properties of fractal networks: Scaling, numerical simulations, and physical realizations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1994, 66, 381–443. [CrossRef]

- Cherepanov, G.P.; Balankin, A.S.; Ivanova, V.S. Fractal fracture mechanics—a review. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1995, 51(6), 997-1033. [CrossRef]

- Gouyet, J.F. Physics and Fractal Structures. Springer: New York, 1996.

- Mosco, U. Invariant field metrics and dynamical scalings on fractals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 79, 4067–4070. [CrossRef]

- Barlow, M.T.; Bass, R.F. Brownian Motion and Harmonic Analysis on Sierpinski Carpets. Canad. J. Math. 1999, 51, 673–744. [CrossRef]

- Duplantier, B. Conformally invariant fractals and potential theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84(7), 1363. [CrossRef]

- Havlin, S.; Ben-Avraham, D. Diffusion in disordered media, Adv. Phys. 2002, 51, 187–292. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S.; Samayoa, D.; Miguel, I.A.; Ortiz, J.P.; Cruz, M.Á.M. Fractal topology of hand-crumpled paper. Phys. Rev. E 2010, 81(6), 061126. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S.; Horta, R.A.; Garcia-Perez, G.; Gayosso-Martinez, F.; Sanchez-Chavez, H.; Martinez-Gonzalez, C.L. Fractal features of a crumpling network in randomly folded thin matter and mechanics of sheet crushing. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 87(5), 052806. [CrossRef]

- Barnsley, M., Vince, A. Developments in fractal geometry. Bull. Math. Sci. 2013, 3, 299–348. [CrossRef]

- Zmeskal, O.; Dzik, P.; Vesely, M. Entropy of fractal systems. Comp. Math. Appl. 2013, 66(2), 135-146. [CrossRef]

- McGreggor, K., Kunda, M., Goel, A. Fractals and Ravens. Artificial Intelligence 2014, 215, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S. A continuum framework for mechanics of fractal materials I: From fractional space to continuum with fractal metric. Eur. Phys. J. B 2015, 88, 90. [CrossRef]

- Lacan F.; Tresser, Ch. Fractals as objects with nontrivial structures at all scales. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2015, 75, 218–242. [CrossRef]

- Nicolás-Carlock, J.R.; Carrillo-Estrada, J.L.; Dossetti, V. Fractality à la carte: a general particle aggregation model. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19505. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S., Mena, B., Martinez-Cruz, M.A. Topological Hausdorff dimension and geodesic metric of critical percolation cluster in two dimensions. Phys. Lett. A 2017, 381, 2665–2672. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martínez, M. A survey on fractal dimension for fractal structures. Appl. Math. Nonlin. Sci. 2016, 1(2), 437-472. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S.; Martínez-Cruz, M.A.; Susarrey-Huerta, O.; Damian-Adame, L. Percolation on infinitely ramified fractal networks. Phys. Lett. A 2018, 382, 12–19. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S.; Martínez-Cruz, M.A.; Álvarez-Jasso, M.D.; Patiño-Ortiz, M.; Patiño-Ortiz, J. Effects of ramification and connectivity degree on site percolation threshold on regular lattices and fractal networks. Phys. Lett. A 2019, 383, 957-966. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Arellano, A.; Bermúdez-Gómez, S.; Hernández-Simón, L. M.; Bory-Reyes, J. D-summable fractal dimensions of complex networks. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2019, 119, 210-214. [CrossRef]

- Anguera, J.; Andújar, A.; Jayasinghe, J.; Chakravarthy, V.S.; Chowdary, P.S.R.; Pijoan, J.L.; Ali, T.; Cattani, C. Fractal antennas: An historical perspective. Fractal Fract. 2020, 4(1), 3. 3. [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Cheong, K.H. The fractal dimension of complex networks: A review. Information Fusion 2021, 73, 87-102. [CrossRef]

- Soltanifar, M. A generalization of the Hausdorff dimension theorem for deterministic fractals. Mathematics 2021, 9(13), 1546. [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.; Nanda, M.N.; Chowdary, M.S.; Sajid, M. Fractals: An Eclectic Survey, Part-II. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 379. [CrossRef]

- Buczolich, Z.; Maga, B.; Vértesy, G. Generic Hölder level sets and fractal conductivity. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 164, 112696. [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, P.M.; de Pablo, J.J. Random Knotting in Fractal Ring Polymers. Macromolecules 2022, 55(18), 8409-8417. [CrossRef]

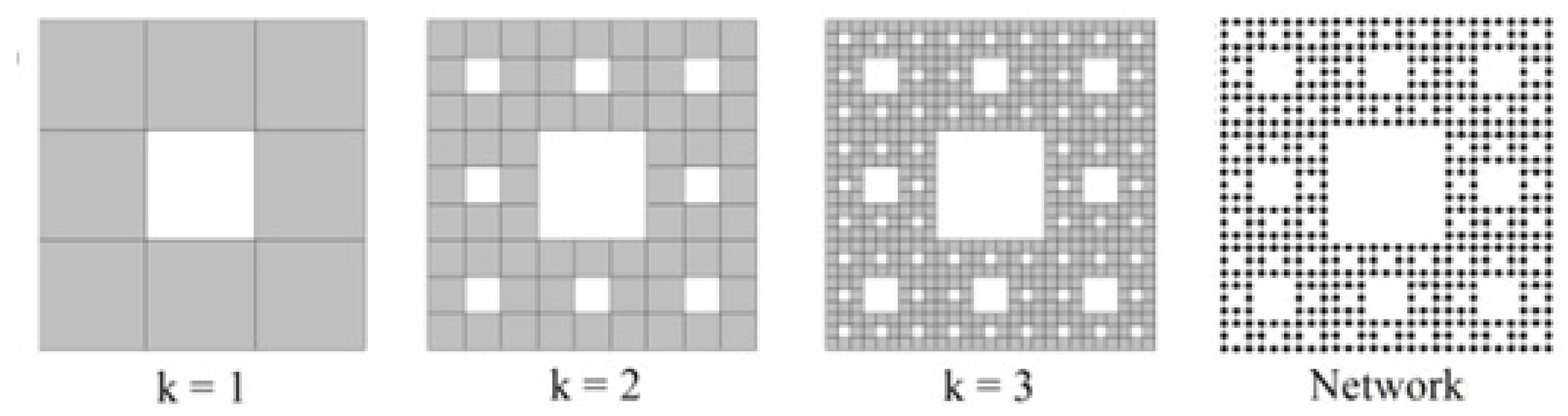

- Balankin, A.S.; Ramírez-Joachin, J.; González-López, G.; Gutíerrez-Hernández, S. Formation factors for a class of deterministic models of pre-fractal pore-fracture networks. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 162, 112452. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.-Á.M.; Ortiz, J.P.; Ortiz, M.P.; Balankin, A.S. Percolation on Fractal Networks: A Survey. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 231. [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, W. A Peano-based space-filling surface of fractal dimension three. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 168, 113130. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S.; Mena, B. Vector differential operators in a fractional dimensional space, on fractals, and in fractal continua. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 168, 113203. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B. Fractal Geometry in Nature: Applications in Physics and Mathematical Theory. Frontiers Appl. Phys. Math. 2024, 1(2), 129-145. https://sprcopen.org/FAPM/article/view/14.

- Balankin, A.S. A survey of fractal features of Bernoulli percolation. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 184, 115044. [CrossRef]

- McDonough, J.; Herczyński, A. Fractal contours: Order, chaos, and art. Chaos 2024, 34(6). [CrossRef]

- Zelinka, I.; Szczypka, M.; Plucar, J.; Kuznetsov, N. From malware samples to fractal images: A new paradigm for classification. Math. Comp. Sim. 2024, 218, 174-203.

- Song, J.;Wang, B.; Jiang, Q.; Hao, X. Exploring the Role of Fractal Geometry in Engineering Image Processing Based on Similarity and Symmetry: A Review. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1658. [CrossRef]

- Danca, M.-F.; Jonnalagadda, J.M. Fractional Order Curves. Symmetry 2025, 17, 455. [CrossRef]

- Buriboev, A.S.; Sultanov, D.; Ibrohimova, Z.; Jeon, H.S. Mathematical Modeling and Recursive Algorithms for Constructing Complex Fractal Patterns. Mathematics 2025, 13, 646. [CrossRef]

- Hudnall, K.; D’Souza, R.M. What does the tree of life look like as it grows? Evolution and the multifractality of time. J. Theor. Biol. 2025, 607, 112121.

- Balka, R.; Buczolich, Z.: Elekes, M. A new fractal dimension: the topological Hausdorff dimension. Adv. Math. 2015, 274, 881–927. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki M. Phase transition and fractals. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1983, 69, 65–76. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S. Effective degrees of freedom of a random walk on a fractal. Phys. Rev. E 2015, 92, 062146. [CrossRef]

- Haynes, C.P.; Roberts, A.P. Generalization of the fractal Einstein law relating conduction and diffusion on networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 020601. [CrossRef]

- Gefen, Y.;. Mandelbrot, B.B.; Aharony, A. Critical phenomena on fractal lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 855–858. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S. The topological Hausdorff dimension and transport properties of Sierpinski carpets. Phys, Lett. A 2017, 381, 2801–2808. [CrossRef]

- Golmankhaneh, A.K.; Balankin, A.S. Sub-and super-diffusion on Cantor sets: Beyond the paradox. Phys. Lett. A 2018, 382(14), 960-967. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S.; Golmankhaneh, A.K.; Patiño-Ortiz, J.; Patiño-Ortiz, M. Noteworthy fractal features and transport properties of Cantor tartans, Phys. Lett. A 2018, 382, 1534–1539. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cruz, M.-Á.; Patiño-Ortiz, J.; Patiño-Ortiz, M.; Balankin, A.S. Some Insights into the Sierpinski Triangle Paradox. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 655. [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.W.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, P.P.; Qiu, W.Y. The architecture of Sierpinski knots. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem., 2012, 68, 595-610. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=d71da465eddc5fc4f78af04eb626857cf148068f.

- Alexander, K.; Taylor, A.J.; Dennis, M.R. Proteins analysed as virtual knots. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7(1), 42300. [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, P.M.; de Pablo, J.J. (2022). Random Knotting in Fractal Ring Polymers. Macromolecules 2022, 55(18), 8409-8417. [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Definition | Measure/Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Hausdorff-Besicovitch dimension | where U is any non-empty subset of n-dimensional Euclidean space, . Hausdorff meausre is , where , and diameter of U is | |

| Minkowski -Bouligand dimension | Let denotes the least number of balls in a covering of F by balls of radius . It is follows from the definition of that | |

| Minkowski dimension | is the parallel body to F: , for some , where n is the topological dimension | |

| Kolmogorov-Schirelman-Potjrajin | is the smallest number of balls of diameter less or equal to which are needed to cover fractal | |

| Mandelbrot-Schirelman-Kolmogorov | is the least number of balls of radius less than which are needed to cover fractal | |

| Upper box-counting dimension |

F is non-empty subset of . is any of the following:

|

|

| Lower box-counting dimension | ||

| box-counting dimension | ||

| upper modified box-counting dimension | If F can be decomposed into a countable number of pieces in such a way that the largest piece has a small a dimension as possible. | |

| Lower modified box-counting dimension | ||

| Packing dimension |

|

is a collection a disjoint balls of radius at most with center in F. Packing measures is: , where . |

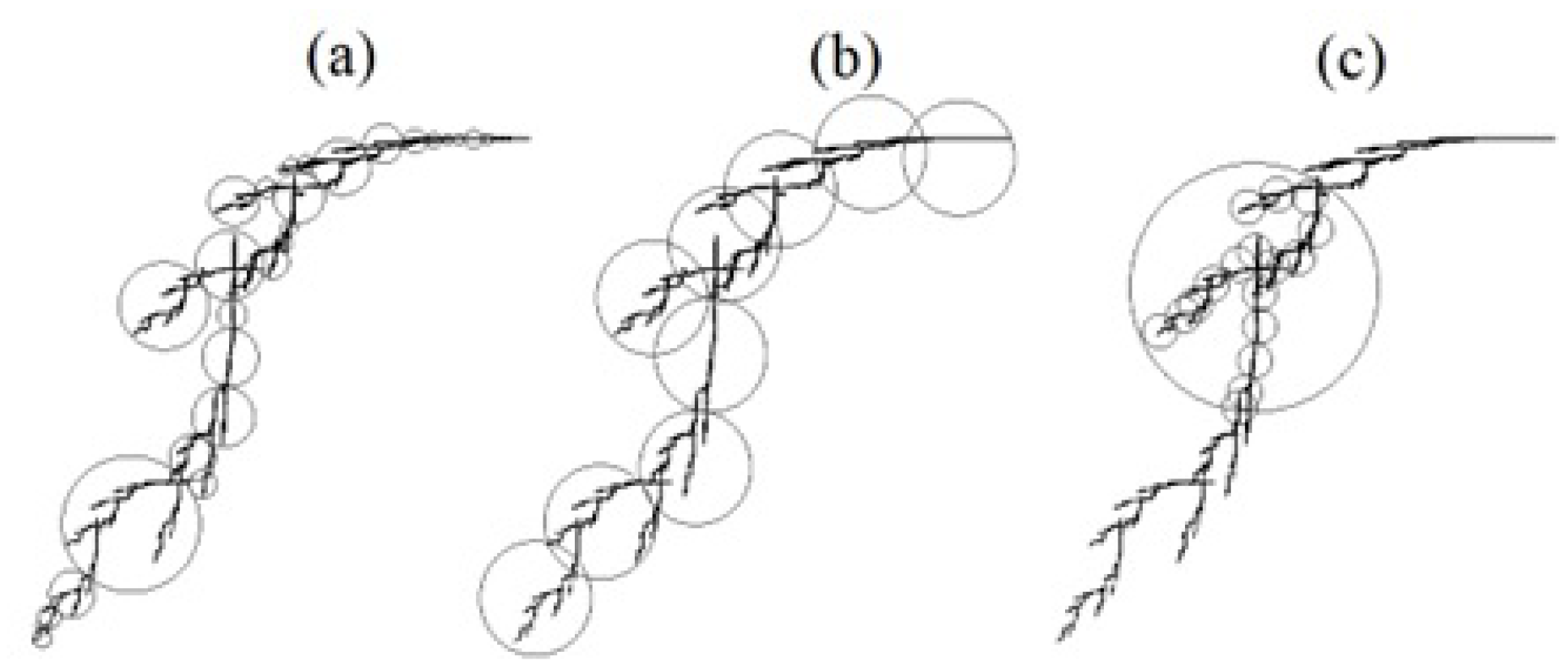

| Assouad dimension | such that for all and | denote the covering balls (see for illustration Figure 10c). |

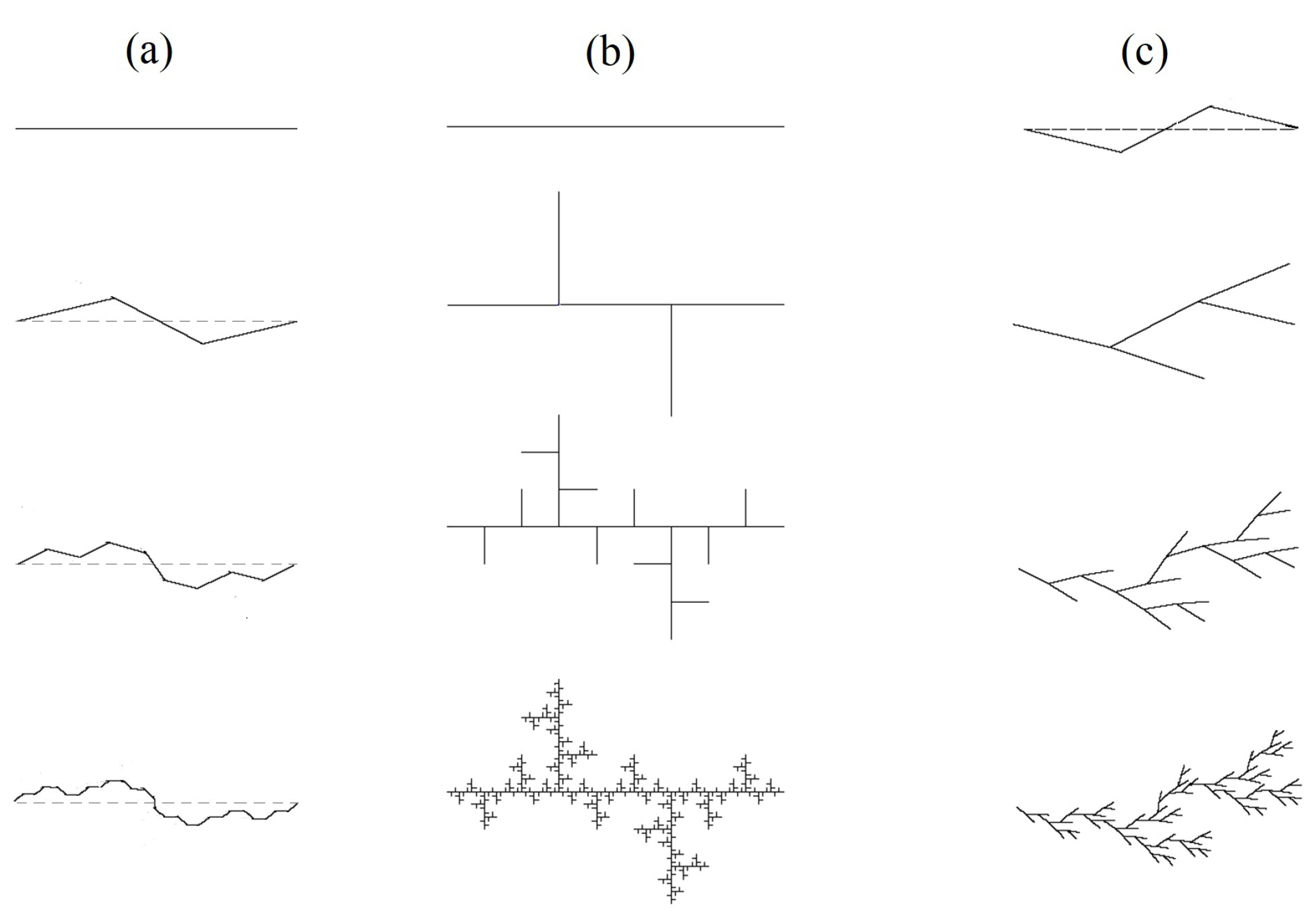

| Divider dimension (of Jordan curves) | -maximum number of points , on the curve C, in that order, such that , . |

| Figure | D | d | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cantor set C | 4 | 0 | 0 | See discussion in Ref. [110] | See discussion in Ref. [110] | See discussion in Ref. [110] | See discussion in Ref. [110] | |

| Cartesian product | See Ref. [4] | 1 | See discussion in Ref. [110] | See discussion in Ref. [110] | See discussion in Ref. [110] | See discussion in Ref. [110] | ||

| Cartesian tartan | See Ref. [111] | 1 | 0.387 | |||||

| Koch curve | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Sierpiński arrowhead curve | 7b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Koch curve | 12a | 1.99 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

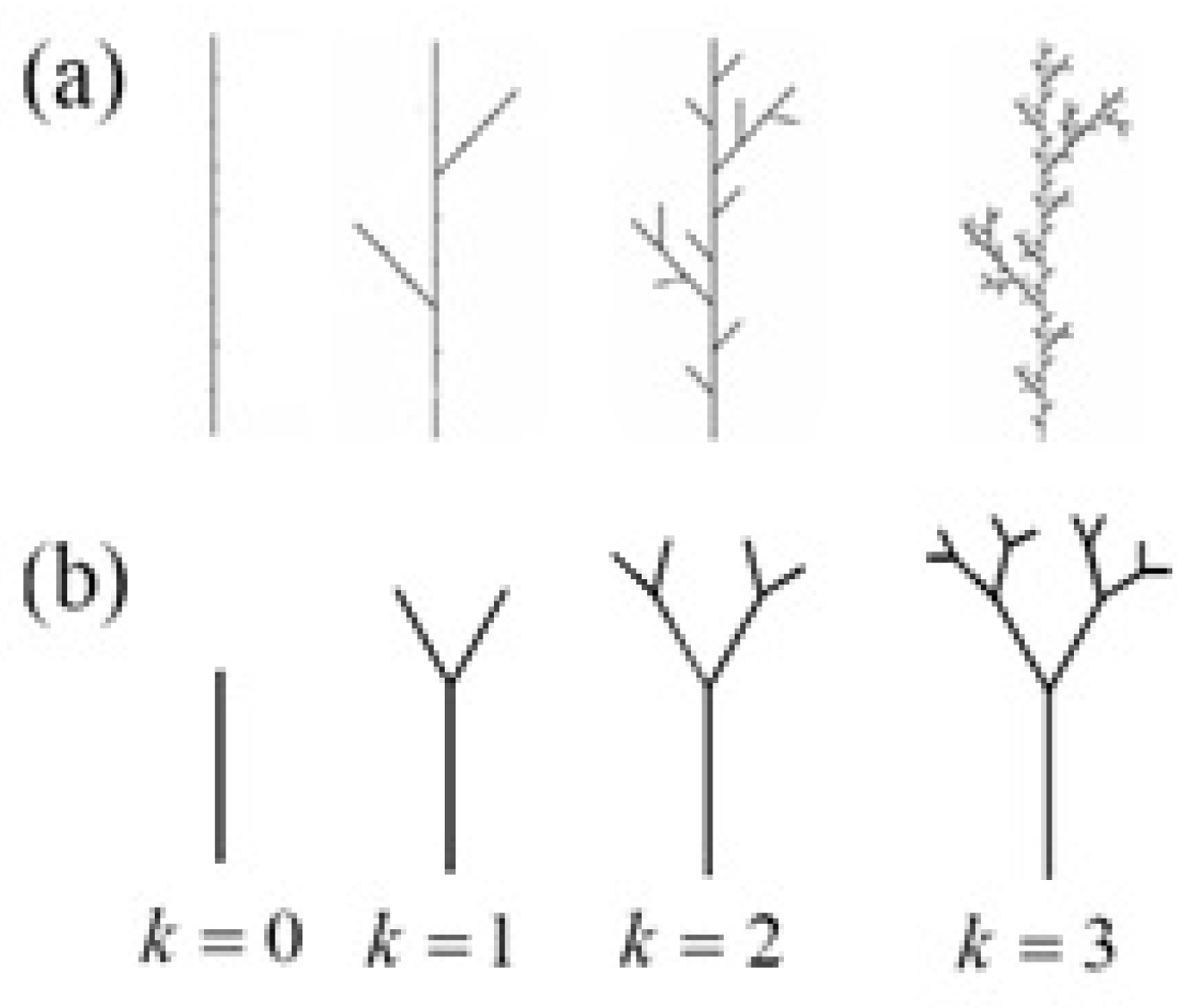

| Tree | 12b | 1 | 1 | 1.188... | 1.741 | 0 | ||

| Leaf | 12c | 1 | 1 | 1.188... | 1.741 | 0 | ||

| Tree | 2a | 1 | 1 | 1.188... | 1.741 | 0 | ||

| Diamond fractal | 13(6) | 1 | 1 | 1.137 | 1.448 | 0.012 | ||

| Sierpiński gasket | 7a | 1 | 1 | 1.805 | 0.635 | |||

| Sierpiśki carpet | 8 | 1.806 | 1.979 | 0.384 | 0.635 | |||

| Sierpiśki cube | See Ref. [92] | 2 | 2.933 | 2.998 | 0.41 | |||

| Sierpiśki waveguide | See Ref. [2] | 2 | 2.806 | 2.98 | 0.596 | |||

| Menger sponge | 13(4) | 2 | 2.52 | 2.94 | 0.49 | |||

| Complement of Menger sponge | 13(1) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2/3 |

| Percolation cluste in | See Ref. [81] | 91/94 | 1 | 1.6574 | 1.6617 | 1.317 | 2 | 0.053 |

| Percolation cluste in | See Ref. [97] | 2.52293 | 1 | 1.828 | 1.834 | 1.327 | 2.341 | 0.022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).