Submitted:

13 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Characteristics of Foundation Neural Networks

2.1. Model Size and Parameter Complexity

2.2. Transformer Architecture: A Computational Core

2.3. Memory Bandwidth and Data Movement

2.4. Precision and Quantization

2.5. Sparsity and Structured Pruning

2.6. Summary of Computational Features

- –

- Extremely large parameter spaces: ,

- –

- High sequence length and embedding dimension: ,

- –

- Quadratic complexity in attention layers: ,

- –

- Intensive memory bandwidth requirements: ,

- –

- Opportunities for quantization: ,

- –

- Potential for sparsity and structured compression: .

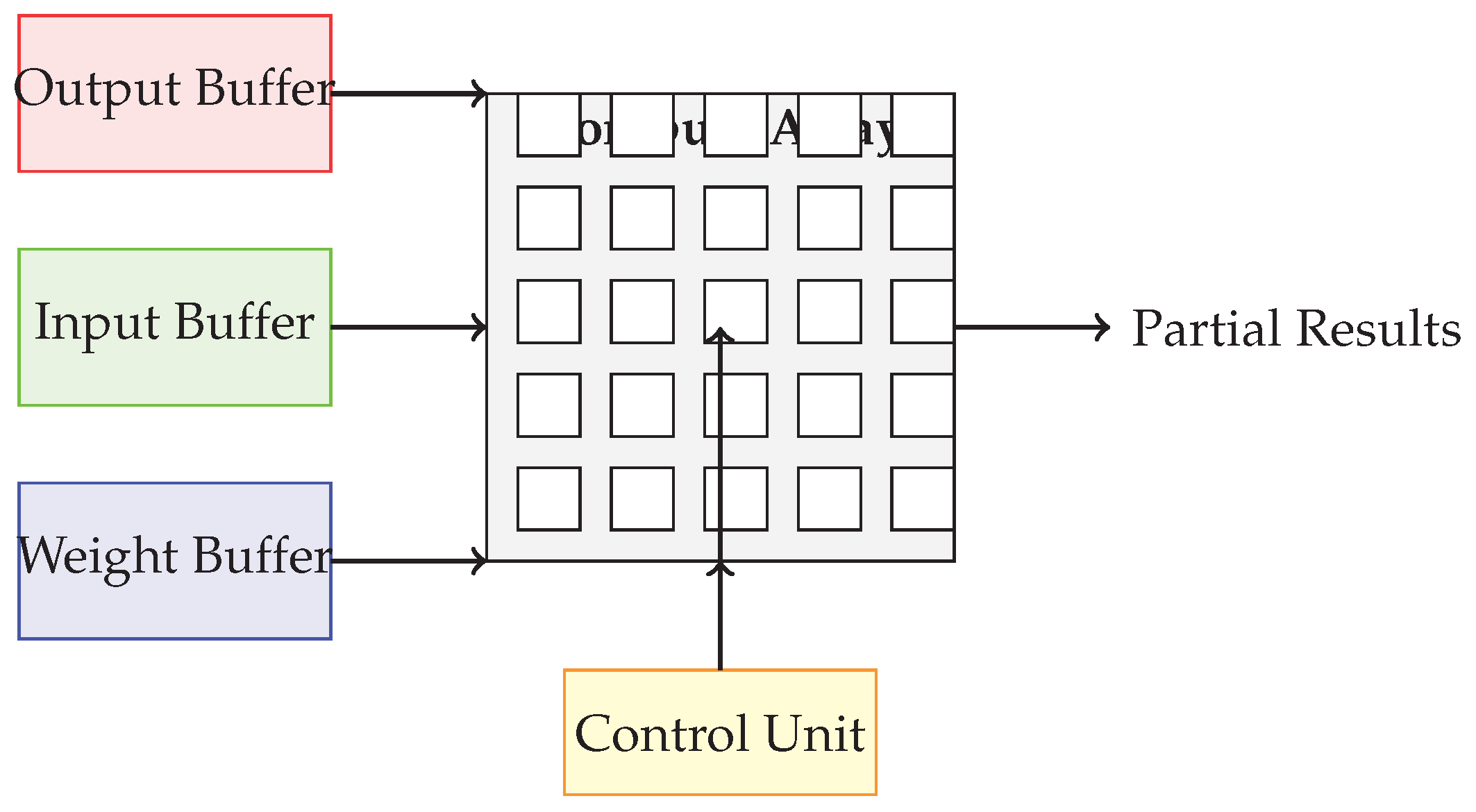

3. Taxonomy of FPGA-Based Accelerator Architectures for Foundation Models

4. Design and Optimization Techniques for FPGA-Based Foundation Model Accelerators

5. Case Studies and Benchmark Comparisons

6. Challenges and Future Directions

7. Conclusion and Outlook

References

- Sabogal, S.; George, A.; Crum, G. ReCoN: A Reconfigurable CNN Acceleration Framework for Hybrid Semantic Segmentation on Hybrid SoCs for Space Applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE SPACE COMPUTING CONFERENCE (SCC), 10662 LOS VAQUEROS CIRCLE, PO BOX 3014, LOS ALAMITOS, CA 90720-1264 USA, 2019; pp. 41–52. [CrossRef]

- Abramovici, M.; Emmert, J.; Stroud, C. Roving STARs: An Integrated Approach to on-Line Testing, Diagnosis, and Fault Tolerance for FPGAs in Adaptive Computing Systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings Third NASA/DoD Workshop on Evolvable Hardware. EH-2001, 2001, pp. 73–92. [CrossRef]

- Pitsis, G.; Tsagkatakis, G.; Kozanitis, C.; Kalomoiris, I.; Ioannou, A.; Dollas, A.; Katevenis, M.G.H.; Tsakalides, P. Efficient Convolutional Neural Network Weight Compression for Space Data Classification on Multi-fpga Platforms. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ACOUSTICS, SPEECH AND SIGNAL PROCESSING (ICASSP), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2019; International Conference on Acoustics Speech and Signal Processing ICASSP, pp. 3917–3921.

- (SNL), S.N.L. MSTAR Dataset. https://www.sdms.afrl.af.mil/index.php?collection=mstar, 1995.

- Bartolazzi, A.; Cardarilli, G.; Del Re, A.; Giancristofaro, D.; Re, M. Implementation of DVB-RCS Turbo Decoder for Satellite on-Board Processing. In Proceedings of the 1ST IEEE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CIRCUITS AND SYSTEMS FOR COMMNICATIONS, PROCEEDINGS, POLYTECHNIC ST, 29, 19525 ST PETERSBURG, RUSSIA, 2002; pp. 142–145. [CrossRef]

- Mancini, L.; Koutny, M. Formal Specification of N-modular Redundancy. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1986 ACM Fourteenth Annual Conference on Computer Science, New York, NY, USA, 1986; CSC ’86, pp. 199–204. [CrossRef]

- Blott, M.; Preußer, T.B.; Fraser, N.J.; Gambardella, G.; O’brien, K.; Umuroglu, Y.; Leeser, M.; Vissers, K. FINN-R: An End-to-End Deep-Learning Framework for Fast Exploration of Quantized Neural Networks. ACM Transactions on Reconfigurable Technology and Systems 2018, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Sha, J. RF Fingerprinting Identification Based on Spiking Neural Network for LEO-MIMO Systems. IEEE WIRELESS COMMUNICATIONS LETTERS 2023, 12, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandi, F.; Castellana, V.G.; Curzel, S.; Fezzardi, P.; Fiorito, M.; Lattuada, M.; Minutoli, M.; Pilato, C.; Tumeo, A. Invited: Bambu: An Open-Source Research Framework for the High-Level Synthesis of Complex Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 58th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), 2021, pp. 1327–1330. [CrossRef]

- Zulberti, L.; Monopoli, M.; Nannipieri, P.; Fanucci, L.; Moranti, S. Highly Parameterised CGRA Architecture for Design Space Exploration of Machine Learning Applications Onboard Satellites. In Proceedings of the 2023 European Data Handling & Data Processing Conference (EDHPC), 2023, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, R. Genetic Algorithms. In Neural Networks: A Systematic Introduction; Rojas, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996; pp. 427–448. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Khosla, D. Spiking Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Energy-Efficient Object Recognition. International Journal of Computer Vision 2015, 113, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantine, J.; Tawk, Y.; Barbin, S.E.; Christodoulou, C.G. Reconfigurable Antennas: Design and Applications. PROCEEDINGS OF THE IEEE 2015, 103, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotin, M.; Conquet, E.; Delange, J.; Tsiodras, T. TASTE: An Open-Source Tool-Chain for Embedded System and Software Development. In Proceedings of the Embedded Real Time Software and Systems (ERTS2012), Toulouse, France, 2012.

- Jian, T.; Gong, Y.; Zhan, Z.; Shi, R.; Soltani, N.; Wang, Z.; Dy, J.; Chowdhury, K.; Wang, Y.; Ioannidis, S. Radio Frequency Fingerprinting on the Edge. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2022, 21, 4078–4093. [CrossRef]

- Misra, D. Mish: A Self Regularized Non-Monotonic Activation Function, 2020, [arXiv:cs.LG/1908.08681].

- Rojas, R. Fuzzy Logic. In Neural Networks: A Systematic Introduction; Rojas, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996; pp. 287–308. [CrossRef]

- Munshi, A. The OpenCL Specification. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Hot Chips 21 Symposium (HCS), 2009, pp. 1–314. [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.; Yang, X.; Zhou, F.; Dong, Z.; Jia, L.; Yan, H. A Correlation-Based Joint CFAR Detector Using Adaptively-Truncated Statistics in SAR Imagery. Sensors 2017, 17, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Li, Y.; Wu, N. Hardware Accelerated Design of a Dual-Mode Refocusing Algorithm for SAR Imaging Systems. SENSORS 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Miller, K.D.; Abbott, L.F. Competitive Hebbian Learning through Spike-Timing-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity. Nature Neuroscience 2000, 3, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding, 2019, [arXiv:cs/1810.04805]. [CrossRef]

- Sabogal, S.; George, A.; Crum, G. Reconfigurable Framework for Resilient Semantic Segmentation for Space Applications. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lyke, J. Reconfigurable Systems: A Generalization of Reconfigurable Computational Strategies for Space Systems. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE AEROSPACE CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS, VOLS 1-7, 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2002; IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings, pp. 1935–1950.

- Lho, YH.; Jang, DJ.; Seo, KK.; Jung, JH.; Kim, KY. The Board Implementation of AVR Microcontroller Checking for Single Event Upsets - Art. No. 60401l. In Proceedings of the ICMIT 2005: Mechatronics, MEMS, and Smart Materials; Wei, YL.; Chong, KT.; Takahashi, T.; Liu, SP.; Li, Z.; Jiang, ZW.; Choi, JY., Eds., 1000 20TH ST, PO BOX 10, BELLINGHAM, WA 98227-0010 USA, 2005; Vol. 6040, PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY OF PHOTO-OPTICAL INSTRUMENTATION ENGINEERS (SPIE), p. L401. [CrossRef]

- Ancuti, C.O.; Ancuti, C.; Timofte, R. NH-HAZE: An Image Dehazing Benchmark with Non-Homogeneous Hazy and Haze-Free Images. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), 2020, pp. 1798–1805. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhang, Y. A Noise-Based Novel Strategy for Faster SNN Training. Neural Computation 2023, 35, 1593–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Dou, Q.; Tang, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhou, H.; Lu, W. ACCDSE: A Design Space Exploration Framework for Convolutional Neural Network Accelerator. In Proceedings of the COMPUTER ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY, NCCET 2017; Xu, W.; Xiao, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, Z., Eds., HEIDELBERGER PLATZ 3, D-14197 BERLIN, GERMANY, 2018; Vol. 600, Communications in Computer and Information Science, pp. 22–34. [CrossRef]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024, 36, 4358–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. A Survey on Evaluation of Large Language Models. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2024, 39, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, I.C.; Kastensmidt, F.L.; Susin, A.A. SEU Susceptibility Analysis of a Feedforward Neural Network Implemented in a SRAM-based FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2017 18th IEEE Latin American Test Symposium (LATS), 2017, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Harsanyi, J.; Chang, C.I. Hyperspectral Image Classification and Dimensionality Reduction: An Orthogonal Subspace Projection Approach. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 1994, 32, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.; Glaser, J. Yosys - A Free Verilog Synthesis Suite. In Proceedings of the The 21st Austrian Workshop on Microelectronics, 2013, Vol. 97.

- Dodge, R.; Congalton, R. Meeting Environmental Challenges with Remote Sensing Imagery. Faculty Publications 2013.

- Joyce, K.E.; Belliss, S.E.; Samsonov, S.V.; McNeill, S.J.; Glassey, P.J. A Review of the Status of Satellite Remote Sensing and Image Processing Techniques for Mapping Natural Hazards and Disasters. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 2009, 33, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, R. Stochastic Networks. In Neural Networks: A Systematic Introduction; Rojas, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996; pp. 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K.; Schorr, A.; Smith, D. NASA’s Space Launch System: Opportunities for Small Satellites to Deep Space Destinations.

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going Deeper with Convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2015, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Li, B.; Lv, S.; Zhou, Q. FPGA-Based Vehicle Detection and Tracking Accelerator. Sensors 2023, 23, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, D.; Harris, M. A Reliable Infrastructure Based on COTS Technology for Affordable Space Application. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings (Cat. No.01TH8542), 2001, Vol. 5, pp. 2435–2441 vol.5. [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, S.; Krammer, T.A.; Saeedi, P. Cloud Detection Algorithm for Remote Sensing Images Using Fully Convolutional Neural Networks, 2018, [arXiv:cs/1810.05782]. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.L.; Ying, R.; Leskovec, J. Inductive Representation Learning on Large Graphs. https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.02216v4, 2017.

- Islam, M.M.; Hasan, M.; Bhuiyan, Z.A. An Analytical Approach to Error Detection and Correction for Onboard Nanosatellites. EURASIP JOURNAL ON WIRELESS COMMUNICATIONS AND NETWORKING 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. The Use of Multiple Measurements in Taxonomic Problems. Annals of Eugenics 1936, 7, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, F.; Lagunas, E.; Martins, W.; Dinh, T.; Skatchkovsky, N.; Simeone, O.; Rajendran, B.; Navarro, T.; Chatzinotas, S. Towards the Application of Neuromorphic Computing to Satellite Communications. In Proceedings of the 39th International Communications Satellite Systems Conference (ICSSC 2022), 2022, Vol. 2022, pp. 91–97. [CrossRef]

- Podobas, A.; Sano, K.; Matsuoka, S. A Survey on Coarse-Grained Reconfigurable Architectures From a Performance Perspective. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 146719–146743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Spain, A.; Parker, J.; Hevert, M.; Roach, J.; Cotten, D. Towards an Integrated GPU Accelerated SoC as a Flight Computer for Small Satellites. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE AEROSPACE CONFERENCE, 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2019; IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings.

- Gholami, A.; Kim, S.; Dong, Z.; Yao, Z.; Mahoney, M.W.; Keutzer, K. A Survey of Quantization Methods for Efficient Neural Network Inference. In Low-Power Computer Vision; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2022.

- Sabne, A. XLA : Compiling Machine Learning for Peak Performance. Google Res 2020.

- Huang, L.; Jiang, B.; Lv, S.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Y. Deep-Learning-Based Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images: A Survey. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2024, 17, 8370–8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.; Ai, Y.; Ma, Z. Design and Implementation of an Adaptive Interference Mitigation Algorithm Based on FPGA. In Proceedings of the PROCEEDINGS OF THE 22ND INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL MEETING OF THE SATELLITE DIVISION OF THE INSTITUTE OF NAVIGATION (ION GNSS 2009), 815 15TH ST NW, STE 832, WASHINGTON, DC 20005 USA, 2009; Institute of Navigation Satellite Division Proceedings of the International Technical Meeting, pp. 360–371.

- Sumbul, G.; de Wall, A.; Kreuziger, T.; Marcelino, F.; Costa, H.; Benevides, P.; Caetano, M.; Demir, B.; Markl, V. BigEarthNet-MM: A Large-Scale, Multimodal, Multilabel Benchmark Archive for Remote Sensing Image Classification and Retrieval [Software and Data Sets]. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2021, 9, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, T. Essentials of the Self-Organizing Map. Neural Networks 2013, 37, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, R. Associative Networks. In Neural Networks: A Systematic Introduction; Rojas, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996; pp. 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, K. Neocognitron: A Self-Organizing Neural Network Model for a Mechanism of Pattern Recognition Unaffected by Shift in Position. Biological Cybernetics 1980, 36, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, R. Neural Networks; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Kannan, R.; Prasanna, V.; Busart, C. Accurate, Low-latency, Efficient SAR Automatic Target Recognition on FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2022 32ND INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON FIELD-PROGRAMMABLE LOGIC AND APPLICATIONS, FPL, 10662 LOS VAQUEROS CIRCLE, PO BOX 3014, LOS ALAMITOS, CA 90720-1264 USA, 2022; International Conference on Field Programmable Logic and Applications, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Low, K.S.; Yau, W.Y. A Multiplier-Less GA Optimized Pulsed Neural Network for Satellite Image Analysis Using a FPGA. In Proceedings of the ICIEA 2008: 3RD IEEE CONFERENCE ON INDUSTRIAL ELECTRONICS AND APPLICATIONS, PROCEEDINGS, VOLS 1-3, 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2008; IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications, pp. 302+. [CrossRef]

- Castelino, C.; Khandelwal, S.; Shreejith, S.; Bogaraju, S.V. An Energy-Efficient Artefact Detection Accelerator on FPGAs for Hyper-Spectral Satellite Imagery, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2407.17647]. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ren, W.; Fu, D.; Tao, D.; Feng, D.; Zeng, W.; Wang, Z. Benchmarking Single-Image Dehazing and Beyond. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2019, 28, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.X.; Yang, J.; Qu, Z.; Wang, Y.X. A Mission Oriented Reconfiguration Technology for Spaceborne FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2018 11TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPUTER AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING, DIRAC HOUSE, TEMPLE BACK, BRISTOL BS1 6BE, ENGLAND, 2019; Vol. 1195, Journal of Physics Conference Series. [CrossRef]

- Shih, F.Y.; Cheng, S. Automatic Seeded Region Growing for Color Image Segmentation. Image and Vision Computing 2005, 23, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, A.L.; Hannun, A.Y.; Ng, A.Y.; et al. Rectifier Nonlinearities Improve Neural Network Acoustic Models. In Proceedings of the Proc. Icml. Atlanta, GA, 2013, Vol. 30, p. 3.

- Morales, G.; Huamán, S.G.; Telles, J. Cloud Detection in High-Resolution Multispectral Satellite Imagery Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning – ICANN 2018; Kůrková, V.; Manolopoulos, Y.; Hammer, B.; Iliadis, L.; Maglogiannis, I., Eds., Cham, 2018; pp. 280–288. [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xilinx. RT Kintex Ultrascale FPGAS for Ultra High Throughput and High Bandwidth Applications, 2020.

- AMD, X. Vitis AI User Guide (UG1414). https://docs.amd.com/r/en-US/ug1414-vitis-ai, 2025.

- Lent, R. A Neuromorphic Architecture for Disruption Tolerant Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), 2019, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Ravi, S.; Joseph, M. Open Source HLS Tools: A Stepping Stone for Modern Electronic CAD. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Research (ICCIC), 2016, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Guo, Y.; Yang, X.; Xiao, S.; Yu, Z. Balancing the Cost and Performance Trade-Offs in SNN Processors. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2021, 68, 3172–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition, 2015, [arXiv:cs.CV/1409.1556].

- Ratnakumar, R.; Nanda, S.J. A High Speed Roller Dung Beetles Clustering Algorithm and Its Architecture for Real-Time Image Segmentation. APPLIED INTELLIGENCE 2021, 51, 4682–4713. [CrossRef]

- Sanic, M.T.; Guo, C.; Leng, J.; Guo, M.; Ma, W. Towards Reliable AI Applications via Algorithm-Based Fault Tolerance on NVDLA. In Proceedings of the 2022 18th International Conference on Mobility, Sensing and Networking (MSN), 2022, pp. 736–743. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Low, K.S. Real Time Runway Detection in Satellite Images Using Multi-Channel PCNN. In Proceedings of the PROCEEDINGS OF THE 2014 9TH IEEE CONFERENCE ON INDUSTRIAL ELECTRONICS AND APPLICATIONS (ICIEA), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2014; IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications, pp. 253+.

- Li, Y.; Yao, B.; Peng, Y. FPGA-based Large-scale Remote Sensing Image ROI Extraction for On-orbit Ship Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE INTERNATIONAL INSTRUMENTATION AND MEASUREMENT TECHNOLOGY CONFERENCE (I2MTC 2022), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2022; IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, G.; Yang, M.; Yang, Z.; Cai, C.; Ming, M.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Tu, L.; Duan, H.; et al. Study on Picometer-Level Laser Interferometer Readout System in TianQin Project. OPTICS AND LASER TECHNOLOGY 2023, 161. [CrossRef]

- Kraft, M.; Walas, K.; Ptak, B.; Bidzinski, M.; Stezala, K.; Pieczynski, D. INTEGRATION OF HETEROGENEOUS COMPUTATIONAL PLATFORM-BASED, AI-CAPABLE PLANETARY ROVER USING ROS 2. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023 - 2023 IEEE INTERNATIONAL GEOSCIENCE AND REMOTE SENSING SYMPOSIUM, 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2023; IEEE International Symposium on Geoscience and Remote Sensing IGARSS, pp. 2014–2017. [CrossRef]

- Del Rosso, M.P.; Sebastianelli, A.; Spiller, D.; Mathieu, P.P.; Ullo, S.L. On-Board Volcanic Eruption Detection through Cnns and Satellite Multispectral Imagery. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren.; Su. Reliability Analysis of N-Modular Redundancy Systems with Intermittent and Permanent Faults. IEEE Transactions on Computers 1979, C-28, 514–520. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Newsam, S. Bag-of-Visual-Words and Spatial Extensions for Land-Use Classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, New York, NY, USA, 2010; Gis ’10, pp. 270–279. [CrossRef]

- Ciardi, R.; Giuffrida, G.; Benelli, G.; Cardenio, C.; Maderna, R. GPU@SAT: A General-Purpose Programmable Accelerator for on Board Data Processing and Satellite Autonomy. In Proceedings of the The Use of Artificial Intelligence for Space Applications; Ieracitano, C.; Mammone, N.; Di Clemente, M.; Mahmud, M.; Furfaro, R.; Morabito, F.C., Eds., Cham, 2023; pp. 35–47. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Peng, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Feng, D. AOD-Net: All-in-One Dehazing Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2017, pp. 4780–4788. [CrossRef]

- Lentaris, G.; Stamoulias, I.; Soudris, D.; Lourakis, M. HW/SW Codesign and FPGA Acceleration of Visual Odometry Algorithms for Rover Navigation on Mars. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2016, 26, 1563–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movidius, I. Intel® Movidius™ Myriad™ 2 Vision Processing Unit 4GB - Product Specifications. https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/products/sku/122461/intel-movidius-myriad-2-vision-processing-unit-4gb/specifications.html, 2020.

- Park, S.S.; Lee, S.; Jun, Y.K. Development and Analysis of Low Cost Telecommand Processing System for Domestic Development Satellites. JOURNAL OF THE KOREAN SOCIETY FOR AERONAUTICAL AND SPACE SCIENCES 2021, 49, 481–488. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, S.; Sugimoto, Y.; Hamamoto, K.; Ishihama, N. Ship Classification from SAR Images Based on Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND APPLICATIONS, VOL 1; Arai, K.; Kapoor, S.; Bhatia, R., Eds., GEWERBESTRASSE 11, CHAM, CH-6330, SWITZERLAND, 2018; Vol. 868, Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, pp. 18–34. [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.; Bergmann, N. Evolving FPGA Based Cellular Automata. In Proceedings of the SIMULATED EVOLUTION AND LEARNING; McKay, B.; Yao, X.; Newton, CS.; Kim, JH.; Furuhashi, T., Eds., HEIDELBERGER PLATZ 3, D-14197 BERLIN, GERMANY, 1999; Vol. 1585, LECTURE NOTES IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, pp. 114–121.

- Liu, C.; Wang, C.; Luo, J. Large-Scale Deep Learning Framework on FPGA for Fingerprint-Based Indoor Localization. IEEE ACCESS 2020, 8, 65609–65617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Design | FPGA Platform | Model Supported | Precision | Throughput (TOPS) | Power (W) | Efficiency (TOPS/W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer-Accel | Xilinx Alveo U280 | BERT-base | INT8 | 1.2 | 45 | 0.0267 |

| DeepStreamX | Intel Stratix 10 GX | GPT-2 (small) | Mixed (FP16/INT8) | 2.3 | 68 | 0.0338 |

| CLIP-FPGA | Xilinx VU9P | CLIP-ViT-B/32 | INT4 | 0.95 | 30 | 0.0317 |

| LLaMA-Light | Xilinx Versal AI Core | LLaMA-7B (decoder only) | INT8 + Pruning | 1.5 | 50 | 0.0300 |

| FlexTranX | Intel Agilex M-Series | T5-small | Runtime Configurable | 1.1 | 42 | 0.0262 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).