Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background and Mathematical Foundations of Neural Network Computations

2.1. Fundamentals of Neural Network Layers

- is the weight matrix for layer l,

- is the bias vector,

- is the activation function (e.g., ReLU, sigmoid, tanh),

- is the output (activation) of layer l,

- is the input vector.

2.2. Convolutional Layers

2.3. Activation Functions

- Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU):

- Sigmoid:

- Hyperbolic Tangent:

- Softmax (for classification):

2.4. Fully Connected Layers

2.5. Loss Functions and Backpropagation

2.6. Quantization and Fixed-Point Arithmetic

2.7. Sparsity and Pruning

2.8. Parallelism and Dataflow Models

- Data-level parallelism (DLP): Simultaneous computation across input batches.

- Model-level parallelism: Distribution of model layers or channels across parallel units.

- Instruction-level parallelism: Pipelined operations at the arithmetic unit level [13].

- Bit-level parallelism: Use of bit-serial or mixed-precision computation.

2.9. Summary

3. Architectural Design of FPGA-Based Neural Network Accelerators

3.1. Computation Units: Multiply-Accumulate (MAC) Engines

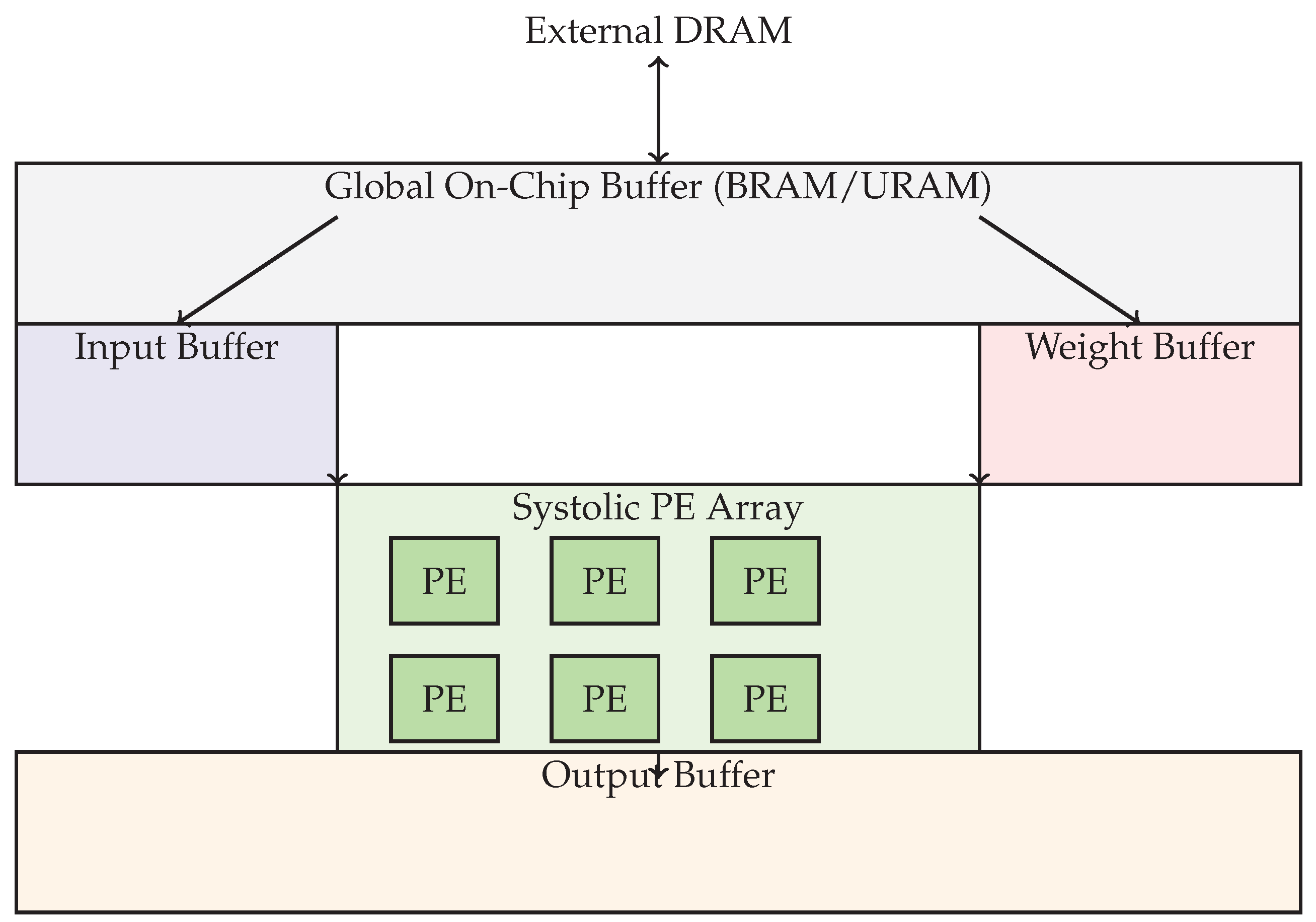

3.2. Systolic Arrays

3.3. On-Chip Memory Hierarchy

- Registers: Hold temporary data within PEs (lowest latency) [23].

- Block RAMs (BRAMs): Serve as scratchpads for activations, weights, and intermediate results.

- UltraRAM (URAM): In large FPGAs, URAM provides higher capacity than BRAM [24].

- Off-chip DRAM: Stores full network parameters and batch inputs when on-chip resources are insufficient [25].

3.4. Dataflow Models

- Weight Stationary (WS): Keep weights static in PEs while inputs and outputs move [28].

- Output Stationary (OS): Keep partial sums in registers, accumulating contributions from streamed weights and inputs.

- Row Stationary (RS): Optimizes reuse of weights, inputs, and partial sums by tiling the computation.

- No Local Reuse (NLR): Stream-based architectures that do not exploit data reuse but allow pipelining and high throughput for small models.

3.5. Control Logic and Scheduling

- Load weights from DRAM to BRAM.

- Stream activations into the systolic array [30].

- Accumulate results and apply activation.

- Store output to BRAM or DRAM.

3.6. Pipeline and Parallelism Strategies

- Inter-layer pipelining: Consecutive layers process different data samples in parallel [32].

- Intra-layer pipelining: Separate pipeline stages for fetch, compute, accumulate, and write-back.

- Loop unrolling: Explicit replication of hardware for inner loops of MAC operations.

3.7. Parameterization and Design Space Exploration

- : Tiling factors for input and output.

- : Parallelism factors for weights and activations.

- : Bit widths of weights and activations.

3.8. Summary

4. Optimization Techniques for FPGA-Based Neural Network Accelerators

5. Case Studies and Benchmarking of FPGA-Based Neural Network Accelerators

6. Comparison with GPU and ASIC Accelerators

7. Challenges and Future Directions in FPGA-Based Neural Network Acceleration

8. Conclusions

References

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database. In Proceedings of the CVPR09, 2009.

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Santoro, A.; Marris, L.; Akerman, C.J.; Hinton, G. Backpropagation and the Brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2020, 21, 335–346. [CrossRef]

- Pritt, M.; Chern, G. Satellite image classification with deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE applied imagery pattern recognition workshop (AIPR). IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–7.

- Hall, C.F. Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11. Science 1975, 188, 445–446. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xing, K.; He, W.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, W. Research on On-Orbit SEU Characterization of the Signal Processing Platform. In Proceedings of the PROCEEDINGS OF THE 2016 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND ENGINEERING APPLICATIONS; Davis, H.; Fang, ZG.; Ke, JF., Eds., 29 AVENUE LAVMIERE, PARIS, 75019, FRANCE, 2016; Vol. 63, ACSR-Advances in Comptuer Science Research, pp. 335–340.

- Cheng, G.; Zhou, P.; Han, J. Learning Rotation-Invariant Convolutional Neural Networks for Object Detection in VHR Optical Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2016, 54, 7405–7415. [CrossRef]

- Férésin, F.; Kervennic, E.; Bobichon, Y.; Lemaire, E.; Abderrahmane, N.; Bahl, G.; Grenet, I.; Moretti, M.; Benguigui, M. In Space Image Processing Using AI Embedded on System on Module: Example of OPS-SAT Cloud Segmentation, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Andjelkovic, M.; Chen, J.; Simevski, A.; Stamenkovic, Z.; Krstic, M.; Kraemer, R. A Review of Particle Detectors for Space-Borne Self-Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE East-West Design & Test Symposium (EWDTS), 2020, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Dou, Q.; Tang, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhou, H.; Lu, W. ACCDSE: A Design Space Exploration Framework for Convolutional Neural Network Accelerator. In Proceedings of the COMPUTER ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY, NCCET 2017; Xu, W.; Xiao, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, Z., Eds., HEIDELBERGER PLATZ 3, D-14197 BERLIN, GERMANY, 2018; Vol. 600, Communications in Computer and Information Science, pp. 22–34. [CrossRef]

- Chitra, K.; Vennila, C. RETRACTED: A Novel Patch Selection Technique in ANN B-Spline Bayesian Hyperprior Interpolation VLSI Architecture Using Fuzzy Logic for Highspeed Satellite Image Processing (Retracted Article). JOURNAL OF AMBIENT INTELLIGENCE AND HUMANIZED COMPUTING 2021, 12, 6491–6504. [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.A.; Viel, F.; Seman, L.O.; Bezerra, E.A.; Zeferino, C.A. A Real-Time SVM-based Hardware Accelerator for Hyperspectral Images Classification in FPGA. MICROPROCESSORS AND MICROSYSTEMS 2024, 104. [CrossRef]

- Blott, M.; Preußer, T.B.; Fraser, N.J.; Gambardella, G.; O’brien, K.; Umuroglu, Y.; Leeser, M.; Vissers, K. FINN-R: An End-to-End Deep-Learning Framework for Fast Exploration of Quantized Neural Networks. ACM Transactions on Reconfigurable Technology and Systems 2018, 11, 16:1–16:23. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, Y.; Li, C. Hardware Acceleration of Satellite Remote Sensing Image Object Detection Based on Channel Pruning. APPLIED SCIENCES-BASEL 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.E.; Samuelsson, A.; Gingsjö, H.; Barendt, J.; Dunne, A.; Buckley, L.; Reisis, D.; Kyriakos, A.; Papatheofanous, E.A.; Bezaitis, C.; et al. High-Performance Compute Board - A Fault-Tolerant Module for On-Boards Vision Processing, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Heiner, J.; Sellers, B.; Wirthlin, M.; Kalb, J. FPGA Partial Reconfiguration via Configuration Scrubbing. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Field Programmable Logic and Applications, 2009, pp. 99–104. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.; Cho, D.H.; Kim, S.M. On-Orbit AI: Cloud Detection Technique for Resource-Limited Nanosatellite. International Journal of Aeronautical and Space Sciences 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lentaris, G.; Stamoulias, I.; Soudris, D.; Lourakis, M. HW/SW Codesign and FPGA Acceleration of Visual Odometry Algorithms for Rover Navigation on Mars. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2016, 26, 1563–1577. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, C.; Luo, J. Large-Scale Deep Learning Framework on FPGA for Fingerprint-Based Indoor Localization. IEEE ACCESS 2020, 8, 65609–65617. [CrossRef]

- Gomperts, A.; Ukil, A.; Zurfluh, F. Development and Implementation of Parameterized FPGA-Based General Purpose Neural Networks for Online Applications. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON INDUSTRIAL INFORMATICS 2011, 7, 78–89. [CrossRef]

- Mellempudi, N.; Kundu, A.; Mudigere, D.; Das, D.; Kaul, B.; Dubey, P. Ternary Neural Networks with Fine-Grained Quantization, 2017, [arXiv:cs/1705.01462]. [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Xuan, C.; Zhai, Y.; Sun, B.; Li, J.; Deng, W.; Mai, C.; Wang, F.; Labati, R.D.; Piuri, V.; et al. TAI-SARNET: Deep Transferred Atrous-Inception CNN for Small Samples SAR ATR. Sensors 2020, 20, 1724. [CrossRef]

- Apicella, A.; Donnarumma, F.; Isgrò, F.; Prevete, R. A Survey on Modern Trainable Activation Functions. Neural Networks 2021, 138, 14–32. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Yang, W.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Zhao, C.; Du, S.; Liu, Y. FPGA-Based Low-Bit and Lightweight Fast Light Field Depth Estimation. IEEE Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems 2025, pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Coca, M.; Datcu, M. FPGA Accelerator for Meta-Recognition Anomaly Detection: Case of Burned Area Detection. IEEE JOURNAL OF SELECTED TOPICS IN APPLIED EARTH OBSERVATIONS AND REMOTE SENSING 2023, 16, 5247–5259. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J. Multi-Scale Deep Neural Network Based on Dilated Convolution for Spacecraft Image Segmentation. Sensors 2022, 22, 4222. [CrossRef]

- Davoli, F.; Kourogiorgas, C.; Marchese, M.; Panagopoulos, A.; Patrone, F. Small Satellites and CubeSats: Survey of Structures, Architectures, and Protocols. International Journal of Satellite Communications and Networking 2019, 37, 343–359. [CrossRef]

- Mazouz, A.; Bridges, C.P. Automated CNN Back-Propagation Pipeline Generation for FPGA Online Training. Journal of Real-Time Image Processing 2021, 18, 2583–2599. [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Ge, F.; Li, Z.; Yue, X.; Zhou, F.; Wu, N. Design and Implementation of OpenCL-Based FPGA Accelerator for YOLOv2. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 21st International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT), 2021, pp. 1004–1007. [CrossRef]

- Abramovici, M.; Emmert, J.; Stroud, C. Roving STARs: An Integrated Approach to on-Line Testing, Diagnosis, and Fault Tolerance for FPGAs in Adaptive Computing Systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings Third NASA/DoD Workshop on Evolvable Hardware. EH-2001, 2001, pp. 73–92. [CrossRef]

- Assim, A.; Reaz, M.B.I.; Ibrahimy, M.I.; Ismail, A.F.; Choong, F.; Mohd-Yasin, F. An AI Based Self-Moderated Smart-Home. INFORMACIJE MIDEM-JOURNAL OF MICROELECTRONICS ELECTRONIC COMPONENTS AND MATERIALS 2006, 36, 91–94.

- Xiang-Zhi, Z.; Ai-Bing, Z.; Yi-Bing, G.; Chao, L.; Wen-Jing, W.; Zheng, T.; Ling-Gao, K.; Yue-Qiang, S. Research on retarding potential analyzer aboard China seismo-electromagnetic satellite. ACTA PHYSICA SINICA 2017, 66. [CrossRef]

- Isik, M.; Paul, A.; Varshika, M.L.; Das, A. A Design Methodology for Fault-Tolerant Computing Using Astrocyte Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th ACM International Conference on Computing Frontiers, New York, NY, USA, 2022; CF ’22, pp. 169–172. [CrossRef]

- Furano, G.; Meoni, G.; Dunne, A.; Moloney, D.; Ferlet-Cavrois, V.; Tavoularis, A.; Byrne, J.; Buckley, L.; Psarakis, M.; Voss, K.O.; et al. Towards the Use of Artificial Intelligence on the Edge in Space Systems: Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine 2020, 35, 44–56. [CrossRef]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024, 36, 4358–4370.

- Jallad, A.H.M.; Mohammed, L.B. Hardware Support Vector Machine (SVM) for Satellite On-Board Applications. In Proceedings of the 2014 NASA/ESA CONFERENCE ON ADAPTIVE HARDWARE AND SYSTEMS (AHS), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2014; NASA/ESA Conference on Adaptive Hardware and Systems, pp. 256–261.

- Racca, G.D.; Laureijs, R.; Stagnaro, L.; Salvignol, J.C.; Alvarez, J.L.; Criado, G.S.; Venancio, L.G.; Short, A.; Strada, P.; Boenke, T.; et al. The Euclid Mission Design. 2016, p. 99040O, [arXiv:astro-ph/1610.05508]. [CrossRef]

- Kerns, S.; Shafer, B.; Rockett, L.; Pridmore, J.; Berndt, D.; van Vonno, N.; Barber, F. The Design of Radiation-Hardened ICs for Space: A Compendium of Approaches. Proceedings of the IEEE 1988, 76, 1470–1509. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.; Harris, M. A Reliable Infrastructure Based on COTS Technology for Affordable Space Application. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings (Cat. No.01TH8542), 2001, Vol. 5, pp. 2435–2441 vol.5. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Han, J. A Survey on Object Detection in Optical Remote Sensing Images. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2016, 117, 11–28. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Prakash, C.; Satashia, S.N.; Kumar, V.; Parikh, K.S. Efficient Implementation of Low Density Parity Check Codes for Satellite Ground Terminals. In Proceedings of the 2014 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ADVANCES IN COMPUTING, COMMUNICATIONS AND INFORMATICS (ICACCI), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2014; pp. 689–695.

- Murphy, J.; Ward, J.E.; Namee, B.M. Machine Learning in Space: A Review of Machine Learning Algorithms and Hardware for Space Applications★ 2021.

- Iandola, F.N.; Han, S.; Moskewicz, M.W.; Ashraf, K.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level Accuracy with 50x Fewer Parameters and ¡0.5MB Model Size, 2016, [arXiv:cs.CV/1602.07360].

- Spiller, D.; Carbone, A.; Latorre, F.; Curti, F. Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulations of Remote Sensing Disaster Monitoring Systems with Real-Time on-Board Computation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON METROLOGY FOR EXTENDED REALITY, ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND NEURAL ENGINEERING (METROXRAINE), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2022; pp. 731–736. [CrossRef]

- Franconi, N.; Cook, T.; Wilson, C.; George, A.D. Comparison of Multi-Phase Power Converters and Power Delivery Networks for Next-Generation Space Architectures. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE AEROSPACE CONFERENCE, 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2023; IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Przewlocka, D.; Wasala, M.; Szolc, H.; Blachut, K.; Kryjak, T. Optimisation of a Siamese Neural Network for Real-Time Energy Efficient Object Tracking; 2020; Vol. 12334, pp. 151–163, [arXiv:cs, eess/2007.00491]. [CrossRef]

- Yanguas-Gil, A.; Mane, A.; Elam, J.W.; Wang, F.; Severa, W.; Daram, A.R.; Kudithipudi, D. The Insect Brain as a Model System for Low Power Electronics and Edge Processing Applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE SPACE COMPUTING CONFERENCE (SCC), 10662 LOS VAQUEROS CIRCLE, PO BOX 3014, LOS ALAMITOS, CA 90720-1264 USA, 2019; pp. 60–66. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, R. The Backpropagation Algorithm. In Neural Networks: A Systematic Introduction; Rojas, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996; pp. 149–182. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Deng, L.; Li, G.; Zhu, J.; Shi, L. Spatio-Temporal Backpropagation for Training High-Performance Spiking Neural Networks. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2018, 12. [CrossRef]

- Mazouz, A.E.; Nguyen, V.T. Online Continual Streaming Learning for Embedded Space Applications. JOURNAL OF REAL-TIME IMAGE PROCESSING 2024, 21. [CrossRef]

- Potsdam, ISPRS. 2d Semantic Labeling Dataset. Accessed: Apr 2018.

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Du, B. Deep Learning for Remote Sensing Data: A Technical Tutorial on the State of the Art. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2016, 4, 22–40. [CrossRef]

- Alom, M.Z.; Taha, T.M.; Yakopcic, C.; Westberg, S.; Sidike, P.; Nasrin, M.S.; Van Esesn, B.C.; Awwal, A.A.S.; Asari, V.K. The History Began from AlexNet: A Comprehensive Survey on Deep Learning Approaches, 2018, [arXiv:cs/1803.01164].

- Koren.; Su. Reliability Analysis of N-Modular Redundancy Systems with Intermittent and Permanent Faults. IEEE Transactions on Computers 1979, C-28, 514–520. [CrossRef]

- Reed, I.; Yu, X. Adaptive Multiple-Band CFAR Detection of an Optical Pattern with Unknown Spectral Distribution. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing 1990, 38, 1760–1770. [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, L.; Barnes, C.; Scheick, L.; Aeronautics, U.S.N.; Administration, S.; Laboratory (U.S.), J.P. An Introduction to Space Radiation Effects on Microelectronics; JPL Publication, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2000.

- Li, Y.; Yao, B.; Peng, Y. FPGA-based Large-scale Remote Sensing Image ROI Extraction for On-orbit Ship Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE INTERNATIONAL INSTRUMENTATION AND MEASUREMENT TECHNOLOGY CONFERENCE (I2MTC 2022), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2022; IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference. [CrossRef]

- Mellier, Y.; Racca, G.; Laureijs, R. Unveiling the Dark Universe with the Euclid Space Mission. In Proceedings of the 42nd COSPAR Scientific Assembly, 2018, Vol. 42, pp. E1.16–2–18.

- Li, B.; Peng, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Feng, D. AOD-Net: All-in-One Dehazing Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2017, pp. 4780–4788. [CrossRef]

- JannisWolf. JannisWolf/Fpga_bnn_accelerator, 2021.

- Martins, L.A.; Sborz, G.A.M.; Viel, F.; Zeferino, C.A. An SVM-based Hardware Accelerator for Onboard Classification of Hyperspectral Images. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd Symposium on Integrated Circuits and Systems Design, New York, NY, USA, 2019; SBCCI ’19, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.J.; Youn, C.H. Cooperative Scheduling Schemes for Explainable DNN Acceleration in Satellite Image Analysis and Retraining. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PARALLEL AND DISTRIBUTED SYSTEMS 2022, 33, 1605–1618. [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio, S.; Menicucci, A.; Gill, E.; Monteleone, C. Extending the NOEL-V Platform with a RISC-V Vector Processor for Space Applications. JOURNAL OF AEROSPACE INFORMATION SYSTEMS 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ekblad, A.; Mahendrakar, T.; White, R.; Wilde, M.; Silver, I.; Wheeler, B. Resource-Constrained FPGA Design for Satellite Component Feature Extraction. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE AEROSPACE CONFERENCE, 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2023; IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Daram, A.R.; Kudithipudi, D.; Yanguas-Gil, A. Task-Based Neuromodulation Architecture for Lifelong Learning. In Proceedings of the 20th International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED), 2019, pp. 191–197. [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015; Navab, N.; Hornegger, J.; Wells, W.M.; Frangi, A.F., Eds., Cham, 2015; pp. 234–241. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Han, J.; Lu, X. Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification: Benchmark and State of the Art. Proceedings of the IEEE 2017, 105, 1865–1883. [CrossRef]

- El-Darymli, K.; McGuire, P.; Power, D.; Moloney, C.R. Target Detection in Synthetic Aperture Radar Imagery: A State-of-the-Art Survey. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing 2013, 7, 071598. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, C.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, B.; Cheung, R.C.C. An FPGA-based MobileNet Accelerator Considering Network Structure Characteristics. In Proceedings of the 2021 31ST INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON FIELD-PROGRAMMABLE LOGIC AND APPLICATIONS (FPL 2021), 10662 LOS VAQUEROS CIRCLE, PO BOX 3014, LOS ALAMITOS, CA 90720-1264 USA, 2021; International Conference on Field Programmable Logic and Applications, pp. 17–23.

- Perrotin, M.; Conquet, E.; Delange, J.; Tsiodras, T. TASTE: An Open-Source Tool-Chain for Embedded System and Software Development. In Proceedings of the Embedded Real Time Software and Systems (ERTS2012), Toulouse, France, 2012.

- Sharma, A.; Unnikrishnan, E.; Ravichandran, V.; Valarmathi, N. Development of CCSDS Proximity-1 Protocol for ISRO’s Extraterrestrial Missions. In Proceedings of the 2014 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ADVANCES IN COMPUTING, COMMUNICATIONS AND INFORMATICS (ICACCI), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2014; pp. 2813–2819.

- Pappalardo, A. Xilinx/Brevitas. Zenodo, 2023.

- Carmeli, G.; Ben-Moshe, B. AI-Based Real-Time Star Tracker. ELECTRONICS 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection, 2020, [arXiv:cs.CV/2004.10934].

- Luo, Q.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, Z. FPGA Design and Implementation of Carrier Synchronization for DVB-S2 Demodulators. In Proceedings of the ASICON 2007: 2007 7TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ASIC, VOLS 1 AND 2, PROCEEDINGS; Tang, TA.; Li, W., Eds., 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2007; pp. 846–849. [CrossRef]

- Gough, MP.; Buckley, AM.; Carozzi, T.; Beloff, N. Experimental Studies of Wave-Particle Interactions in Space Using Particle Correlators: Results and Future Developments. In Proceedings of the FUTURE TRENDS AND NEEDS IN SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING FOR PLASMA PHYSICS IN SPACE; Lui, ATY.; Treumann, RA., Eds., THE BOULEVARD, LANGFORD LANE,, KIDLINGTON OX5 1GB, OXFORD, ENGLAND, 2003; Vol. 32, ADVANCES IN SPACE RESEARCH-SERIES, pp. 407–416. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, F.; Lagunas, E.; Martins, W.; Dinh, T.; Skatchkovsky, N.; Simeone, O.; Rajendran, B.; Navarro, T.; Chatzinotas, S. Towards the Application of Neuromorphic Computing to Satellite Communications. In Proceedings of the 39th International Communications Satellite Systems Conference (ICSSC 2022), 2022, Vol. 2022, pp. 91–97. [CrossRef]

- Stivaktakis, R.; Tsagkatakis, G.; Moraes, B.; Abdalla, F.; Starck, J.L.; Tsakalides, P. Convolutional Neural Networks for Spectroscopic Redshift Estimation on Euclid Data. IEEE Transactions on Big Data 2020, 6, 460–476. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, R. Fast Learning Algorithms. In Neural Networks: A Systematic Introduction; Rojas, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996; pp. 183–225. [CrossRef]

- Karakizi, C.; Karantzalos, K.; Vakalopoulou, M.; Antoniou, G. Detailed Land Cover Mapping from Multitemporal Landsat-8 Data of Different Cloud Cover. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1214. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B. Crowdsourced Mapping, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Gankidi, P.R.; Thangavelautham, J. FPGA Architecture for Deep Learning and Its Application to Planetary Robotics. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE AEROSPACE CONFERENCE, 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2017; IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings.

- Munshi, A. The OpenCL Specification. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Hot Chips 21 Symposium (HCS), 2009, pp. 1–314. [CrossRef]

- Kraft, M.; Walas, K.; Ptak, B.; Bidzinski, M.; Stezala, K.; Pieczynski, D. INTEGRATION OF HETEROGENEOUS COMPUTATIONAL PLATFORM-BASED, AI-CAPABLE PLANETARY ROVER USING ROS 2. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023 - 2023 IEEE INTERNATIONAL GEOSCIENCE AND REMOTE SENSING SYMPOSIUM, 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2023; IEEE International Symposium on Geoscience and Remote Sensing IGARSS, pp. 2014–2017. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Sun, Z.w.; Xing, L. Task Scheduling Algorithm of FPGA for On-Board Reconfigurable Coprocessor. In Proceedings of the 2013 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (ICCSAI 2013), 439 DUKE STREET, LANCASTER, PA 17602-4967 USA, 2013; pp. 207–214.

- Pitsis, G.; Tsagkatakis, G.; Kozanitis, C.; Kalomoiris, I.; Ioannou, A.; Dollas, A.; Katevenis, M.G.H.; Tsakalides, P. Efficient Convolutional Neural Network Weight Compression for Space Data Classification on Multi-fpga Platforms. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ACOUSTICS, SPEECH AND SIGNAL PROCESSING (ICASSP), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2019; International Conference on Acoustics Speech and Signal Processing ICASSP, pp. 3917–3921.

- Yang, C.; Ming, L. Far Field Demonstration Experiment of Fine Tracking System for Satellite-to-Ground Optical Communication. CHINA COMMUNICATIONS 2010, 7, 139–145.

- Estlin, T.A.; Bornstein, B.J.; Gaines, D.M.; Anderson, R.C.; Thompson, D.R.; Burl, M.; Castaño, R.; Judd, M. AEGIS Automated Science Targeting for the MER Opportunity Rover. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2012, 3, 50:1–50:19. [CrossRef]

| Attribute | FPGA | GPU | ASIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance (Throughput) | Medium to high (100–1000+ GOPS), depending on optimization; tailored parallelism | Very high (1–10 TOPS), especially for training and large batch inference | Extremely high (10–100+ TOPS), with optimal architectural tuning |

| Energy Efficiency (GOPS/W) | High, especially with quantized inference and sparse networks | Moderate; high dynamic power due to general-purpose execution | Very high; optimized for minimal switching and maximal reuse |

| Flexibility/Reconfigurability | Fully reprogrammable post-deployment; supports custom dataflows and precision | Fixed architecture but programmable kernels; supports general DL frameworks | Fixed hardware; no post-fabrication flexibility |

| Latency (Single Inference) | Very low, especially for pipelined or low-batch designs | Moderate to high; optimized for batch throughput rather than single-instance latency | Very low; fixed pipelines enable constant and deterministic latency |

| Precision Support | Arbitrary precision (e.g., INT4, INT8, binary); designer-controlled | Typically FP16, FP32, INT8; limited custom precision | Fixed or limited configurable precision (e.g., INT8, binary) |

| Development Complexity | High; requires RTL/HLS expertise or domain-specific compilers | Low to moderate; supported by mature CUDA/OpenCL toolchains | Very high; requires full silicon design, validation, and tape-out |

| Toolchain Maturity | Improving; vendor tools (Vitis, Vivado HLS) and open frameworks (FINN, hls4ml) | Highly mature; full ecosystem support (TensorFlow, PyTorch, cuDNN) | Proprietary; limited reuse and vendor-dependent |

| Deployment Cost | Moderate; lower than ASICs, higher than commodity GPUs | Low to moderate; depends on GPU tier and volume | Very high; amortized only at scale (high NRE) |

| Time to Market | Short to moderate; faster than ASICs due to post-fabrication programmability | Very short; off-the-shelf availability | Very long; includes full VLSI flow and fabrication delays |

| Use Case Fit | Ideal for edge, embedded, and latency-sensitive inference; adaptable workloads | Best for data center training and high-throughput inference | Optimal for high-volume, power-constrained, and dedicated-use cases |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).