Introduction

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have emerged as the cornerstone of modern artificial intelligence (AI) applications, including image classification, object detection, and speech recognition. Since the breakthrough success of AlexNet in the ImageNet competition [

6], CNNs have driven the development of increasingly deep and complex network architectures. However, their high computational intensity and massive memory requirements pose significant challenges for deployment on resource-constrained platforms such as edge devices and mobile systems [

7]. Traditional accelerators, particularly GPUs, offer considerable parallelism but suffer from excessive power consumption and limited flexibility in hardware reuse [

8,

9]. A major theme in the quest for efficiency is the exploitation of model-level sparsity. Techniques such as block pruning [

1] and structured sparsification significantly reduce the number of operations while preserving accuracy, thus enabling faster and more efficient inference. In particular, graph convolutional neural networks (GCNs) involve highly sparse and irregular data access patterns, requiring specialized dataflows for acceleration [

2]. Another complementary optimization is feature map compression, especially in the floating-point domain. As feature maps dominate off-chip memory traffic during CNN inference, their compression—via techniques such as Zero Run-Length Encoding (Zero-RLE) and delta encoding—can greatly alleviate memory bottlenecks without degrading model accuracy [

3].

These algorithmic improvements are further empowered by hardware innovations. FPGA-based solutions enable flexibility and energy-efficient prototyping of sparse CNN accelerators [

1], while ASIC designs can be fine-tuned for sub-block GCN processing [

2]. Beyond conventional CMOS designs, emerging devices such as carbon nanotube field-effect transistors (CNTFETs) and magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs) are enabling the realization of ultra-low-power logic-in-memory architectures for BNNs [

4,

10]. Moreover, interconnect bottlenecks in high-throughput systems have spurred interest in reconfigurable and non-blocking networks such as the dual Benes network, which allows dynamic data routing between memory and compute units while minimizing latency and resource overhead [

5]. This review paper synthesizes insights from five cutting-edge accelerator designs [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], each addressing a specific bottleneck in CNN deployment. By comparing their architectural strategies and implementation outcomes, we aim to clarify the emerging design space and guide future research toward scalable, energy-efficient deep learning systems.

Sparsity-Driven Architectures

Sparsity in convolutional neural networks (CNNs) refers to the presence of a significant number of zero-valued weights or activations that can be skipped during computation [

11,

12]. By leveraging this property, accelerators can reduce unnecessary multiply-accumulate (MAC) operations and minimize memory bandwidth usage [

13,

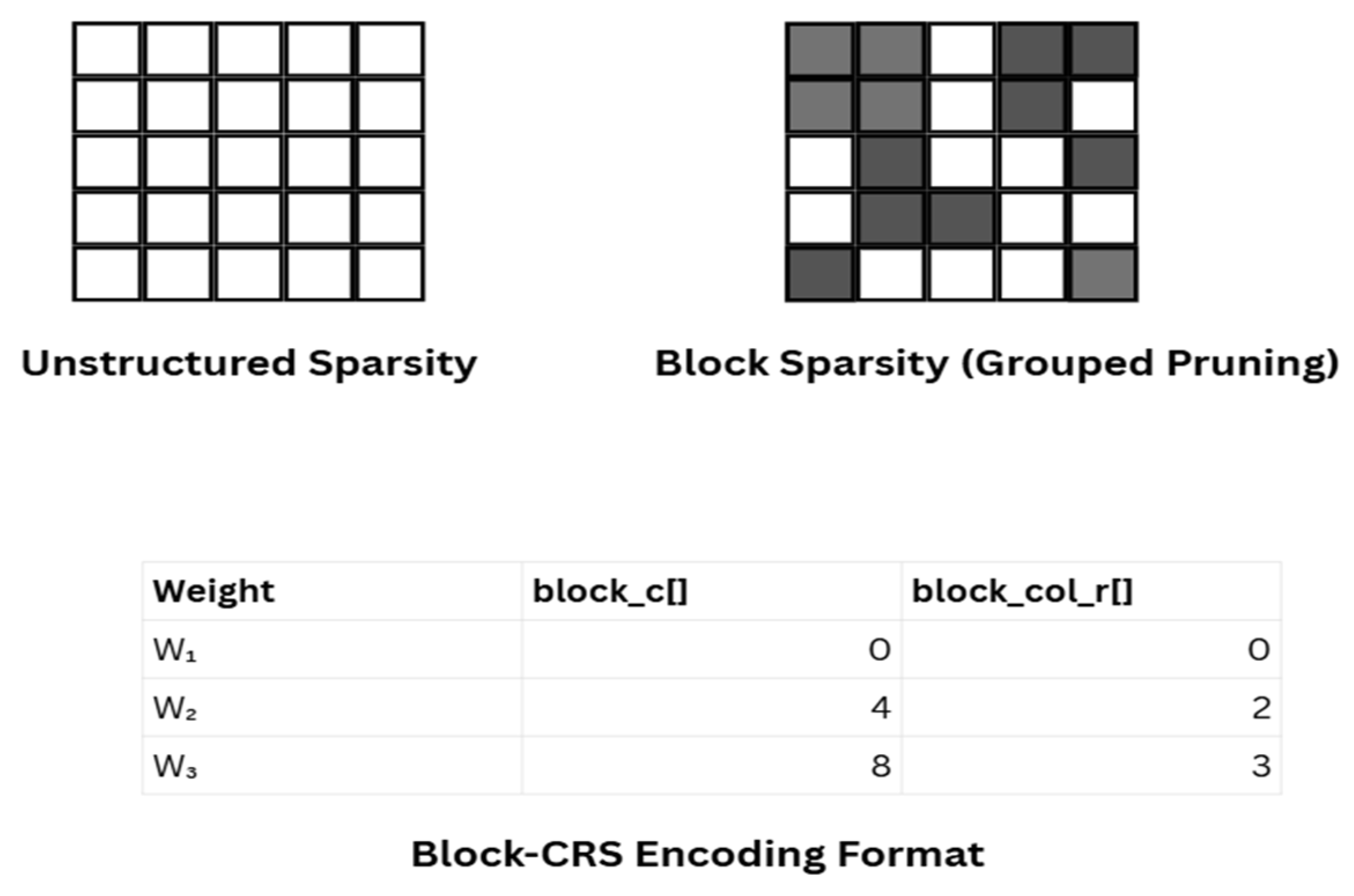

14], which is particularly critical for real-time and edge inference. Several types of sparsity exist in CNNs: unstructured sparsity, where individual weights are pruned independently, and structured sparsity, such as filter, channel, or block pruning, which removes entire groups of weights. While unstructured pruning typically yields higher compression rates, it is more difficult to exploit efficiently on hardware due to irregular data access patterns [

15].

Block Sparsity on FPGA

Yin et al. [

1] propose an FPGA-friendly accelerator tailored for block-pruned CNNs, where groups of four filters are pruned together based on a common input channel [

16]. This approach strikes a balance between regularity and compression ratio. Their hardware design includes:

A custom block-CRS (Compressed Row Storage) format for sparse weights

Sparse matrix decoding logic implemented with minimal overhead

A planarized dataflow optimized for pointwise convolution (1×1)

The authors achieve low latency (16.37 ms) and power-efficient inference (13.32 W) on MobileNet-V2, outperforming conventional dense models deployed on similar FPGAs.

Figure 1 above illustrates the contrast between unstructured sparsity and block-based structured sparsity in convolutional neural networks (CNNs), along with a representation of the block-CRS (Compressed Row Storage) format used to encode sparse weights efficiently. In unstructured sparsity, individual weights are pruned independently, resulting in irregular and random zero-value distributions across the matrix. While this method often achieves a higher pruning ratio, its irregular memory access patterns present challenges for hardware acceleration. In contrast, block sparsity applies pruning at the granularity of grouped filters or submatrices (e.g., 2×2 or 4×4 blocks), which enables more regular memory accesses and hardware-friendly implementation. The corresponding block-CRS encoding captures non-zero weight values along with two index arrays: block_c[], which stores input channel indices, and block_col_r[], which records block row starting positions. This structured format reduces decoding complexity and supports parallel processing on FPGA platforms, as demonstrated in [

1]. Block sparsity thus offers a trade-off between compression efficiency and hardware practicality, making it a compelling design choice for real-time CNN inference.

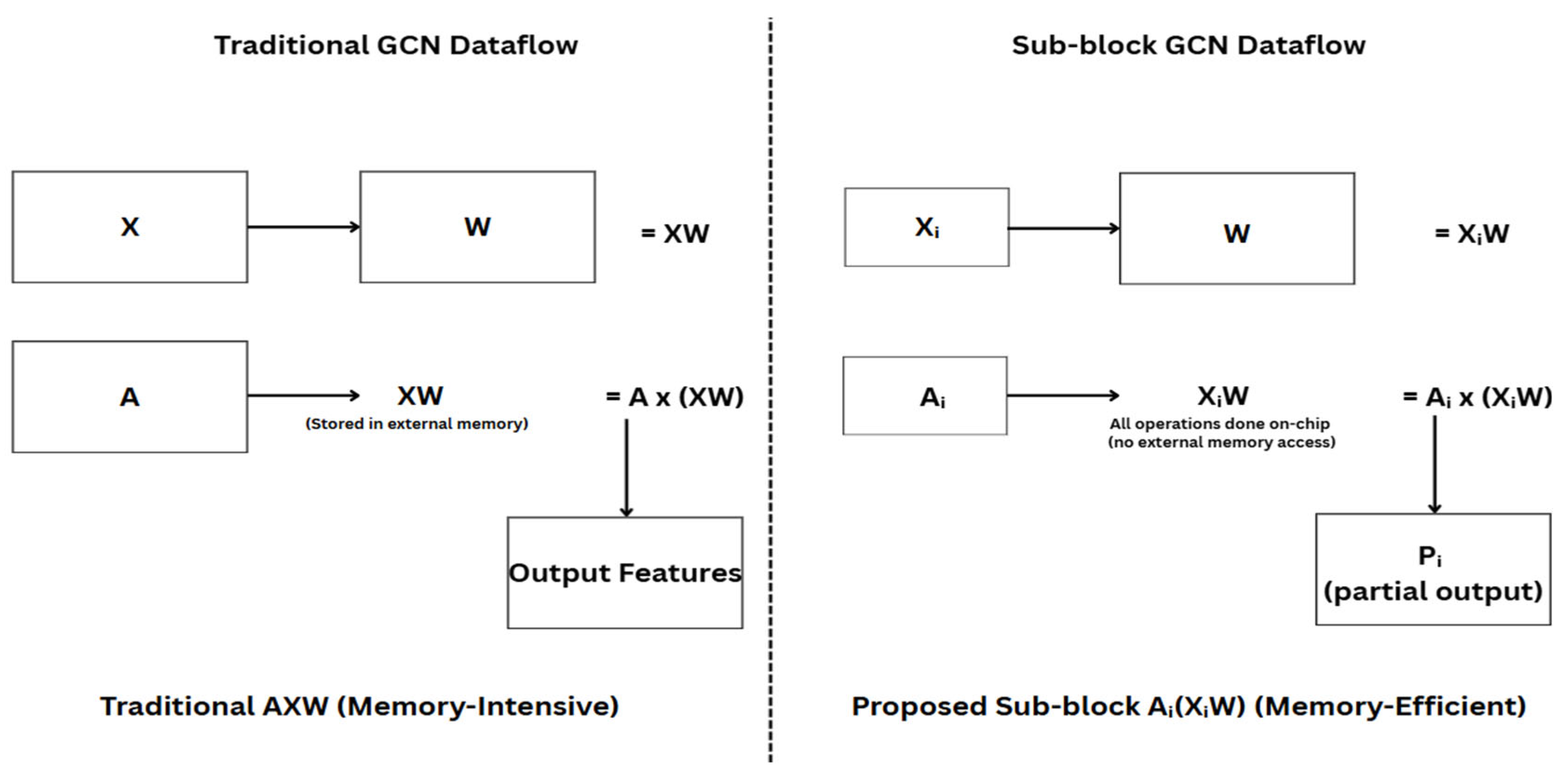

GCN-Specific Sparsity Acceleration on ASIC

Unlike CNNs, graph convolutional networks (GCNs) rely on irregular data access through adjacency matrices. Lee et al. [

2] address this by developing a sparsity-aware ASIC accelerator that:

Processes the GCN equation A.X.W directly without intermediate storage

Partitions matrices into sub-blocks (e.g. Ai, Xi) to fit on-chip memory

Eliminates off-chip memory accesses for the intermediate product (XW)

Their architecture efficiently exploits the extremely sparse nature of adjacency matrices (as low as 0.2% non-zeros) and achieves up to 384G non-zeros/Joule, a significant improvement over FPGA baselines.

Figure 2 above illustrates a comparison between the conventional and proposed GCN dataflows for graph convolution acceleration. In the traditional approach (left), the feature matrix X is first multiplied with the weight matrix W to produce XW, which is then stored in external memory before being multiplied with the adjacency matrix A. This two-step computation introduces significant memory overhead, particularly due to off-chip memory access. In contrast, the proposed method by Lee et al. [

2] (right) performs the computation on partitioned sub-blocks

Xi,

Ai, and reuses the same W across blocks. The computation

Ai(

XiW) is fully executed on-chip, eliminating the need for intermediate memory storage and significantly improving energy efficiency. This localized dataflow not only reduces memory bandwidth but also supports scalable parallelism, making it highly suitable for sparse graph data.

Feature Map Compression Techniques

As convolutional neural networks (CNNs) scale in depth and width, the size of intermediate feature maps often exceeds that of model weights, especially in early layers. These feature maps are frequently transferred between on-chip compute units and off-chip memory (e.g., DRAM), leading to severe energy and latency bottlenecks [

17,

18,

19]. Thus, compressing feature maps—especially floating-point activations—has become a key strategy in energy-efficient CNN hardware design.

Motivation for Feature Map Compression

A single forward pass through a CNN like ResNet-50 can generate hundreds of megabytes of feature data. Studies estimate that

up to 80% of memory traffic in CNN accelerators comes from intermediate activations, not weights [

20]. Reducing the size of these activations directly translates to reduced:

However, compression must preserve numerical precision, especially when operating on 32-bit or 16-bit floating-point formats.

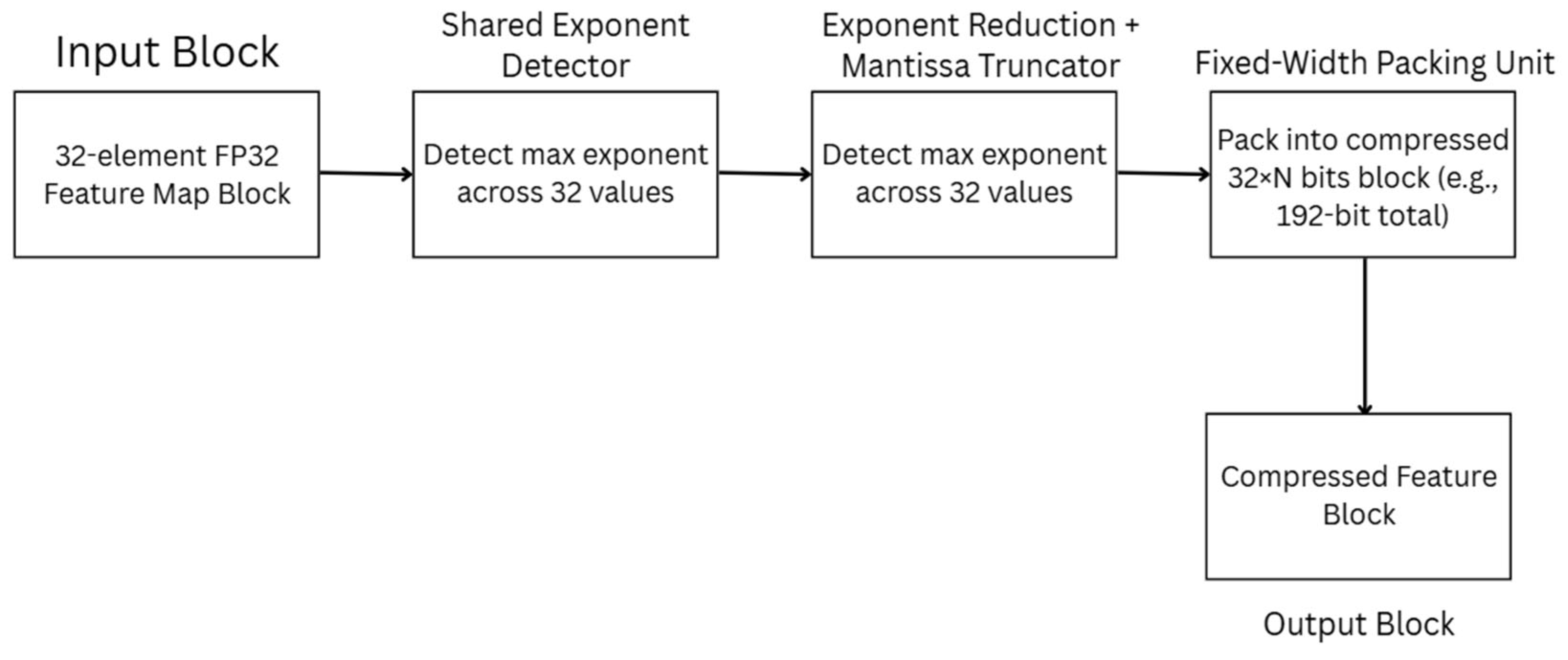

Proposed Work: MSFP-Based Compression

The work by Yin et al. [

3] proposes a novel Multi-Stage Floating Point (MSFP) compression pipeline for feature maps. Their strategy:

Splits feature maps into blocks of 32 elements

Applies a two-level exponent reduction and block-level mantissa truncation

Uses adaptive thresholds to preserve high dynamic range where necessary

The compressed output is then packed in a fixed-width format and written back to memory using low-overhead control logic. Key hardware highlights:

2X reduction in memory traffic

Only 2.1% silicon overhead on FPGA

Retains >99% accuracy across tested networks

Figure 3 above shows the MSFP-based compression pipeline for floating-point feature maps as proposed by Yin et al. [

3]. The input consists of a 32-element block of FP32 feature values, such as those produced by intermediate convolutional layers. A shared exponent detector first scans all values to determine the maximum exponent, which is then reused across the block to enable efficient exponent alignment [

21]. The exponent reduction and mantissa truncator stage subsequently trims the mantissas to a lower bit precision (e.g., 8 or 10 bits), significantly reducing bit width while maintaining numerical range. The fixed-width packing unit encodes the resulting data into a compact format (e.g., 192 bits), which is then stored in memory as a compressed feature block. This method achieves up to 2.5× memory traffic reduction with negligible accuracy loss (<1%) and minimal hardware overhead, making it well-suited for resource-constrained FPGA deployments [

22].

Alternative Methods in Literature

Other recent works have explored:

Quantization-based compression: converting activations to INT4/INT8 [

23]

Zero-value run-length encoding (RLE) [

24]

Entropy coding (e.g., Huffman) on sparse feature maps [

25,

26]

Tile-based JPEG-like compression for image-related CNNs [

27]

Each technique trades off complexity, latency, and compression ratio.

| Method |

Compression Type |

Complexity |

Accuracy Impact |

Suitability |

|

MSFP (Yin et al. [3])

|

Floating-point block |

Low |

<1% |

FPGA-friendly |

|

RLE [24] |

Zero-run encoding |

Very low |

None |

Sparse maps |

|

INT8 quantization [23] |

Bit-width reduction |

Low |

Moderate |

Edge devices |

|

JPEG-style [27] |

Spatial + frequency |

Medium |

Image only |

Vision CNNs |

Emerging Low-Power CNN Architectures

As neural network deployment shifts toward edge devices and energy-constrained platforms, emerging low-power architectures play a critical role in achieving high throughput with reduced energy budgets [

28,

29]. These designs explore non-traditional hardware substrates, ultra-low-bit computation, and energy-aware topologies to push the boundary of CNN efficiency [

30].

Binarized Neural Networks (BNNs)

BNNs constrain both weights and activations to binary values (±1), replacing multiply-accumulate (MAC) operations with XNOR + bitcount logic. This drastically reduces:

Arithmetic power consumption [

31]

Memory bandwidth

Circuit complexity

In [

4], an energy-efficient BNN accelerator is implemented using spintronic CNTFET technology, exploiting non-volatility and fast switching. The resulting architecture achieves:

BNNs are ideal for applications like keyword spotting, visual wake words, and sensor-driven analytics [

32].

Near-Sensor Processing and Analog Techniques

Near-sensor inference integrates CNN accelerators directly with imaging sensors, reducing I/O power [

7,

33]. For example:

proposes an in-pixel convolution processor [

34]

uses analog crossbar arrays for ultra-efficient MACs [

35,

36]

Though analog designs face challenges like noise, they offer unparalleled efficiency:

Up to 100 TOPS/W in emerging neuromorphic chips [

37]

Reconfigurable Energy-Scalable Cores

New FPGA and ASIC designs support voltage-frequency scaling, dynamic precision adjustment, and clock gating, adapting power consumption in real time based on workload complexity [

38].

For instance:

Envision [

27] supports subword-parallelism and dynamic voltage scaling

introduces a

multi-gear CNN engine that dynamically switches between INT8, INT4, and binary precision [

39]

Such adaptivity ensures high peak efficiency during low-load scenarios without compromising accuracy during critical layers.

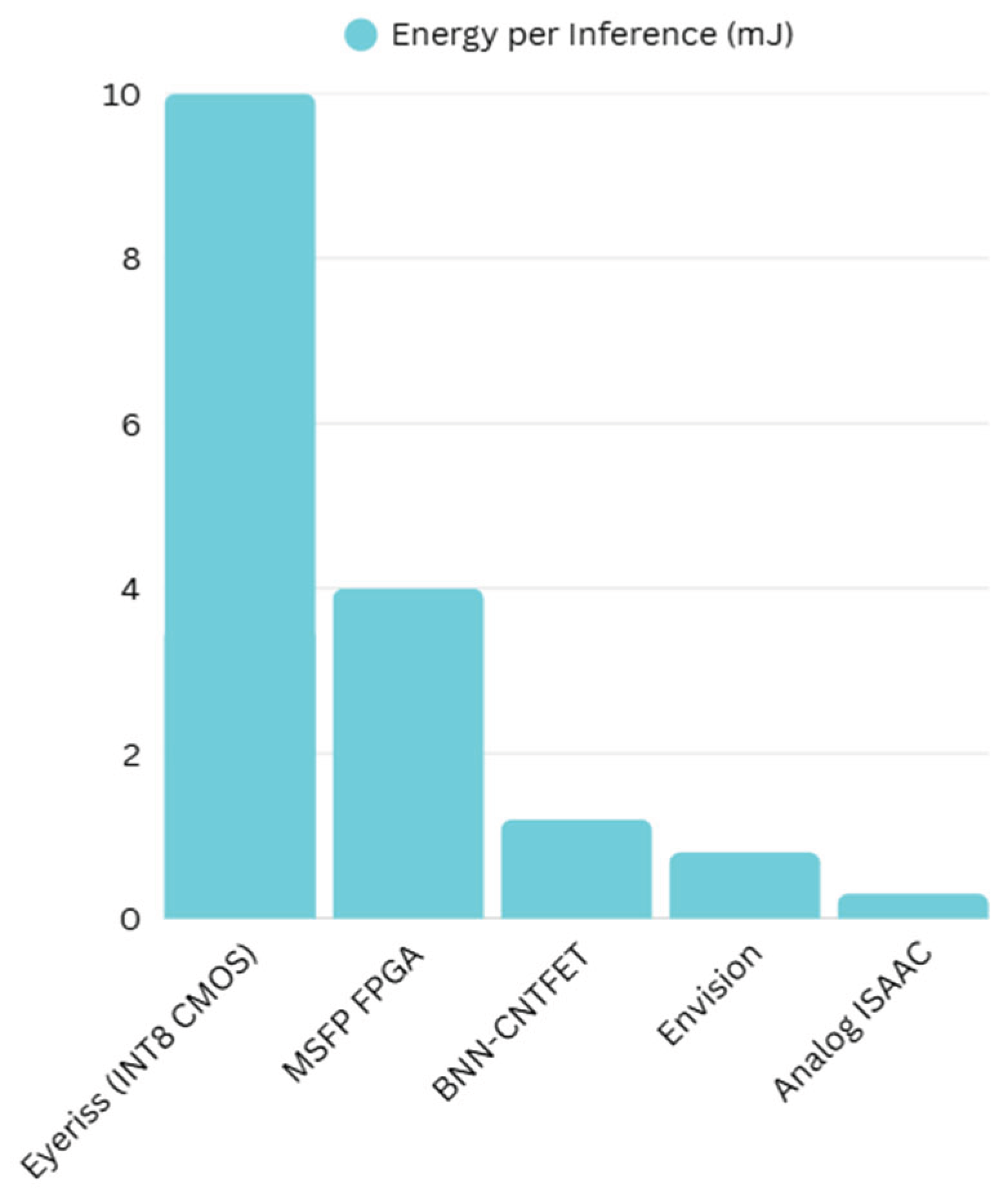

Figure 4 above presents a comparative analysis of energy consumption per inference across various CNN accelerator architectures. Eyeriss, a baseline INT8 CMOS-based design, consumes approximately 10 mJ per image, reflecting the energy cost of traditional spatial accelerators. In contrast, MSFP-based FPGA compression [

3] reduces inference energy by over 2×, thanks to mantissa truncation and shared exponent encoding. Binarized Neural Networks (BNNs), implemented using spintronic CNTFETs [

4], further push efficiency boundaries, achieving sub-1.5 mJ inference cost through ultra-low-bit computation. The Envision architecture [

27], based on dynamic voltage and precision scaling, balances energy savings with flexible bitwidth support, while analog-domain accelerators such as ISAAC [

40] reach near-theoretical energy efficiency at just ~0.3 mJ/image [

41,

42]. These trends underscore a growing shift toward specialized, energy-adaptive, and mixed-technology solutions for edge AI acceleration.

Conclusion and Future Outlook

In this review, we have surveyed a broad range of recent strategies aimed at improving the energy and memory efficiency of convolutional neural network (CNN) accelerators. From structured and unstructured pruning techniques to compression schemes like Multi-Stage Floating Point (MSFP) encoding [

43,

44], these methods offer significant reductions in storage and computation overhead without sacrificing model accuracy. We also examined the growing role of Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) and sub-block dataflows in tackling irregular data structures, as well as the shift toward ultra-efficient architectures like Binarized Neural Networks (BNNs), spintronic hardware, and analog in-memory computing.

Looking forward, several promising directions emerge [

45]. First, hardware-software co-design will become increasingly essential [

24], especially for deploying compressed or pruned models in edge applications. Second, there is a growing need for adaptive precision frameworks, where bitwidths are dynamically adjusted layer-by-layer based on accuracy–energy tradeoffs [

46]. Third, emerging technologies such as neuromorphic computing and photonic accelerators may revolutionize inference speed and efficiency if integration challenges can be overcome. Lastly, the field would benefit from standardized benchmarks and open-source toolchains [

47] to fairly evaluate pruning and compression under realistic deployment scenarios [

48,

49,

50]. As edge AI continues to scale, these efficient design strategies will remain critical for real-time, power-aware intelligent systems, ranging from smart cameras to autonomous robots.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

- X. Yin, Z. Wu, D. Li, C. Shen, and Y. Liu, “An Efficient Hardware Accelerator for Block Sparse Convolutional Neural Networks on FPGA,” IEEE Embedded Syst. Lett., vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 158–161, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K.-J. Lee, S. Moon, and J.-Y. Sim, “A 384G Output NonZeros/J Graph Convolutional Neural Network Accelerator,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II: Express Briefs, vol. 69, no. 10, pp. 4158–4161, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B.-K. Yan and S.-J. Ruan, “Area Efficient Compression for Floating-Point Feature Maps in Convolutional Neural Network Accelerators,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II: Express Briefs, vol. 70, no. 2, pp. 746–749, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Nasab, A. Amirany, M. H. Moaiyeri, and K. Jafari, “High-Performance and Robust Spintronic/CNTFET-Based Binarized Neural Network Hardware Accelerator,” IEEE Trans. Emerging Topics Comput., vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 527–535, Apr.–Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Y. Lo, C.-W. Sham, and C. Fu, “Novel CNN Accelerator Design With Dual Benes Network Architecture,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 59524–59530, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and G. E. Hinton, “ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks,” in Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS), 2012, pp. 1097–1105.

- H. Y. Jiang, Z. Qin, and Y. Zhang, “Ultra-Low-Power CNN Accelerators for Edge AI: A Comprehensive Survey,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 1293–1310, Apr. 2024.

- Y.-H. Chen, T. Krishna, J. Emer, and V. Sze, “Eyeriss: An energy-efficient reconfigurable accelerator for deep convolutional neural networks,” IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 127–138, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Aung, K.H.H.; Kok, C.L.; Koh, Y.Y.; Teo, T.H. An Embedded Machine Learning Fault Detection System for Electric Fan Drive. Electronics, 2024, 13, 493. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, Y. Du, W. Wen, Y. Chen, and X. Hu, “Energy-Efficient Spiking Neural Network Processing Using Magnetic Tunnel Junction-Based Stochastic Computing,” IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst., vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 1451–1464, Jun. 2020.

- Y. Zhou, H. Li, and Z. Chen, “Runtime-Aware Dynamic Sparsity Control in CNNs for Efficient Inference,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., early access, May 2024.

- R. Patel, K. Mehta, and B. Roy, “FPGA-Friendly Weight Sharing for CNN Compression,” IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst., vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 399–412, Feb. 2024.

- C. Liu, S. Wang, and H. Yu, “Benchmarking Resistive Crossbar Arrays for Scalable CNN Inference,” IEEE Trans. VLSI Syst., vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 395–407, Mar. 2024.

- Y. Xu, H. Zhou, and C. Lin, “Sparse CNN Execution with Zero-Skipping Techniques for Hardware Acceleration,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 1234–1245, Apr. 2024.

- Y. He, J. Lin, Z. Liu, H. Wang, L.-J. Li, and S. Han, “AMC: AutoML for model compression and acceleration on mobile devices,” in Proc. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. (ECCV), 2018, pp. 815–832.

- K. S. Lee, J. Park, and C. Lim, “ECO-CNN: Energy-Constrained Compilation of CNNs for FPGAs,” IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst., vol. 43, no. 5, pp. 1553–1565, May 2024.

- Y. Chen et al., “Eyeriss: An energy-efficient reconfigurable accelerator for deep CNNs,” IEEE JSSC, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 127–138, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, L. Xie, and C. Zhang, “Energy-Aware Burst Scheduling for CNN Accelerator DRAM Accesses,” IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst., vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 234–246, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Wang, X. Guo, and H. Zhang, “Quantized CNN Implementation Using Systolic Arrays for Edge Applications,” IEEE Trans. Comput., vol. 73, no. 3, pp. 811–823, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang et al., “Cambricon-X: An accelerator for sparse neural networks,” Proc. MICRO, pp. 1–12, 2016.

- L. Zhang, H. Shi, and M. Liu, “Pipeline-Optimized CNN Accelerator for Energy-Constrained Edge Devices,” IEEE Trans. Comput., early access, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Luo, Y. Wang, and B. Gao, “Hybrid Entropy-Masked Compression for Feature Maps in CNNs,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, vol. 70, no. 7, pp. 2823–2835, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Courbariaux et al., “BinaryNet: Training deep neural networks with weights and activations constrained to +1 or -1,” arXiv:1602.02830, 2016.

- A. Shafiee et al., “ISAAC: A convolutional neural network accelerator with in-situ analog arithmetic in crossbars,” Proc. ISCA, pp. 14–26, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Han et al., “EIE: Efficient inference engine on compressed deep neural network,” Proc. ISCA, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Cho, D. Lee, and J. Kim, “Entropy Coding for CNN Compression in Hardware-Constrained Devices,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, vol. 71, no. 2, pp. 458–470, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Moons et al., “Envision: A 0.26-to-10 TOPS/W subword-parallel dynamic-voltage-accuracy-frequency-scalable CNN processor,” IEEE JSSC, vol. 52, no. 1, 2017.

- M. Tang, J. Zhao, and L. Liu, “Bit-Serial CNN Accelerators for Ultra-Low-Power Edge AI,” IEEE Trans. Comput., vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 1071–1083, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, W. Zhang, and J. Liang, “Feature Map Compression Using Delta Encoding for CNN Accelerators,” IEEE Trans. VLSI Syst., vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 410–422, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, Y. Wang, and T. Chen, “Error-Resilient Quantized CNN Inference via Fault-Tolerant Hardware Design,” IEEE Trans. VLSI Syst., vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 702–712, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, F. Song, and X. He, “HAQ-V2: Hardware-Aware CNN Quantization with Mixed Precision Training,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., early access, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Zhou et al., “Adaptive noise shaping for efficient keyword spotting,” IEEE TCSVT, vol. 32, no. 11, pp. 7803–7814, Nov. 2022.

- M. T. Ali, K. Roy, and A. R. Chowdhury, “3D-Stacked Vision Processors for Ultra-Low-Power CNN Acceleration,” IEEE Trans. VLSI Syst., vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 672–684, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Park et al., “An in-pixel processor for convolutional neural networks,” IEEE JSSC, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 842–853, Mar. 2021.

- A. Shafiee et al., “ISAAC: A CNN accelerator with in-situ analog arithmetic in crossbars,” Proc. ISCA, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Sun, Y. Zhang, and J. Gao, “Sparse CNN Acceleration Using Optimized Systolic Arrays,” IEEE Trans. Comput., vol. 73, no. 2, pp. 456–467, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Querlioz et al., “Bio-inspired programming for ultra-low-power neuromorphic hardware,” IEEE TED, vol. 69, no. 2, pp. 360–371, 2022.

- Kok, C.L.; Siek, L. Designing a Twin Frequency Control DC-DC Buck Converter Using Accurate Load Current Sensing Technique. Electronics 2024, 13, 45. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang et al., “Dynamic reconfigurable CNN engine with precision-aware acceleration,” IEEE TCAS-I, vol. 70, no. 6, pp. 2161–2173, Jun. 2023.

- A. Shafiee et al., “ISAAC: A CNN accelerator with in-situ analog arithmetic in crossbars,” Proc. ISCA, 2016.

- K. Lin, Y. Liu, and Z. Wang, “Analog CNN Acceleration Using Low-Leakage Memristor Crossbars,” IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, vol. 71, no. 2, Feb. 2024.

- A. Ghasemzadeh, M. Khorasani, and M. Pedram, “ISAAC+: Towards Scalable Analog CNNs with In-Memory Computing,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, vol. 71, no. 2, pp. 682–693, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Luo, K. Zhang, and J. Huang, “Fine-Grained Structured Pruning of CNNs for FPGA-Based Acceleration,” IEEE Trans. VLSI Syst., vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 1122–1134, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kok, C.L.; Ho, C.K.; Aung, T.H.; Koh, Y.Y.; Teo, T.H. Transfer Learning and Deep Neural Networks for Robust Intersubject Hand Movement Detection from EEG Signals. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8091. [CrossRef]

- Kok, C.L.; Ho, C.K.; Chen, L.; Koh, Y.Y.; Tian, B. A Novel Predictive Modeling for Student Attrition Utilizing Machine Learning and Sustainable Big Data Analytics. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9633. [CrossRef]

- J. Ren, Y. Bai, and Y. Zhao, “Reinforcement-Learned Precision Scaling for CNN Accelerators,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 99–103, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Das, M. Tan, and J. Ren, “COMET: A Benchmark for Compression-Efficient Transformers and CNNs on Edge Devices,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 104382–104395, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Tan, C. Wang, and J. Lee, “Benchmarking Analog and Digital Neural Accelerators for TinyML,” IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst., vol. 32, no. 4, Apr. 2024.

- W. Liu, H. Shen, and Y. Feng, “TinyEdgeBench: A Benchmark Suite for Edge CNN Accelerators,” IEEE Trans. VLSI Syst., vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 621–634, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Kok, T. H. Teo, Y. Y. Koh, Y. Dai, B. K. Ang and J. P. Chai, Development and Evaluation of an IoT-Driven Auto-Infusion System with Advanced Monitoring and Alarm Functionalities, IEEE ISCAS 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).