Submitted:

02 August 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background and Motivation

3. Precision Formats and Numerical Representations

| Format | Bits | Exp/Mant | Range | Type | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP32 | 32 | 8 / 23 | Float | Full precision training | |

| FP16 | 16 | 5 / 10 | Float | Mixed precision | |

| bfloat16 | 16 | 8 / 7 | Float | TPU training | |

| TF32 | 19 | 8 / 10 | Float | Tensor cores | |

| FP8 (E5M2) | 8 | 5 / 2 | Float | Experimental training | |

| INT8 | 8 | – / 8 | Fixed | Inference | |

| INT4 | 4 | – / 4 | Fixed | Edge inference |

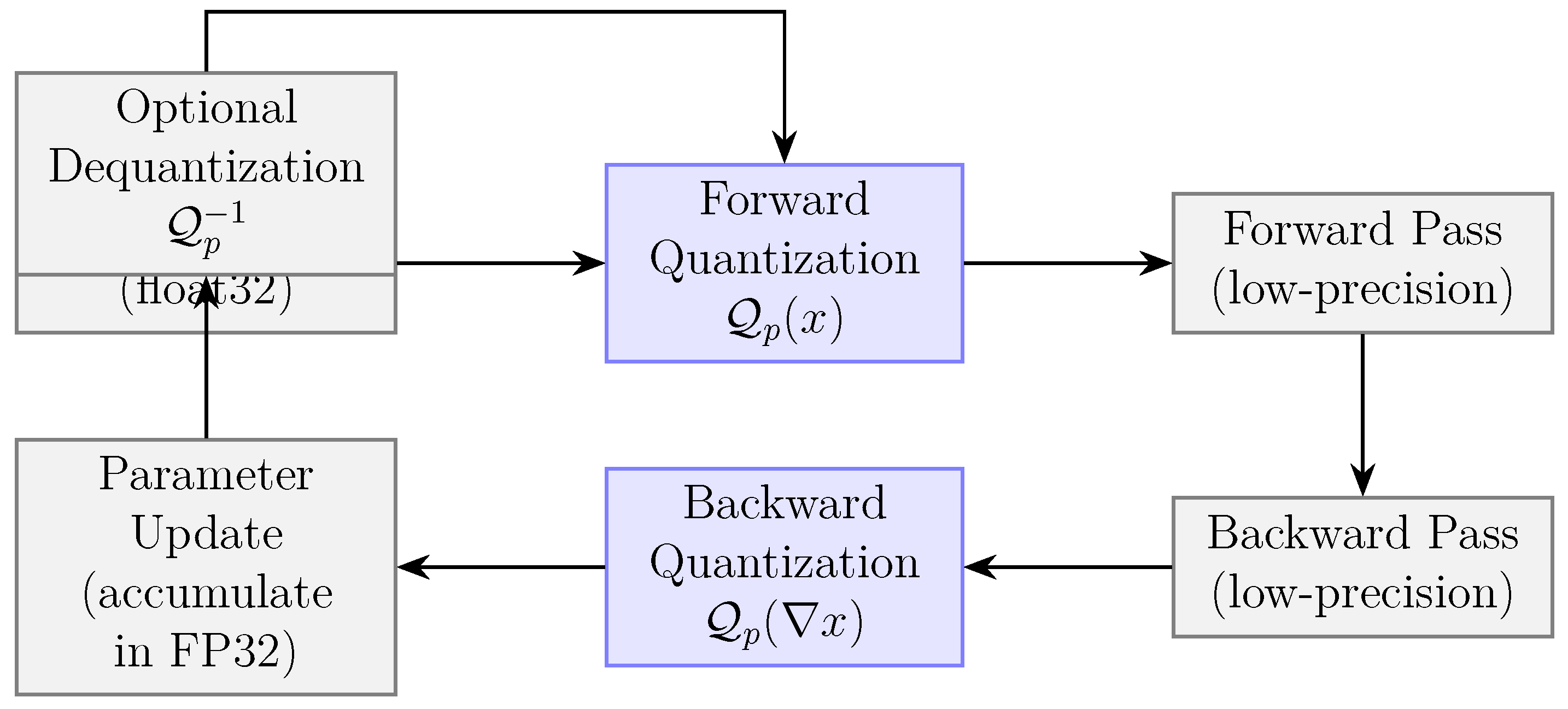

4. Quantization Techniques for Training

5. Optimizers and Gradient Handling in Low Precision

6. Hardware Support for Low-Precision Training

7. Case Studies and Benchmarks

8. Theoretical Insights into Low-Precision Training

9. Open Challenges and Future Directions

10. Conclusions

References

- Das, D.; Mellempudi, N.; Mudigere, D.; Kalamkar, D.D.; Avancha, S.; Banerjee, K.; Sridharan, S.; Vaidyanathan, K.; Kaul, B.; Georganas, E.; et al. Mixed Precision Training of Convolutional Neural Networks using Integer Operations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kalamkar, D.; Mudigere, D.; Mellempudi, N.; Das, D.; Banerjee, K.; Avancha, S.; Vooturi, D.T.; Jammalamadaka, N.; Huang, J.; Yuen, H.; et al. A study of BFLOAT16 for deep learning training. 2019; arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.12322. [Google Scholar]

- Panferov, A.; Chen, J.; Tabesh, S.; Castro, R.L.; Nikdan, M.; Alistarh, D. QuEST: Stable Training of LLMs with 1-Bit Weights and Activations. 2025; arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.05003. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Shen, L.; Huang, H.; Liu, W. Quantized Adam with Error Feedback. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2021, 12, 56:1–56:26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Tabaru, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Honda, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Tsuruoka, Y. Direct Quantized Training of Language Models with Stochastic Rounding. 2024; arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.04787. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zheng, L.; Yao, Z.; Wang, D.; Stoica, I.; Mahoney, M.W.; Gonzalez, J. ActNN: Reducing Training Memory Footprint via 2-Bit Activation Compressed Training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021; pp. 1803–1813. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Yu, D.; Wu, T.; Wang, H. PaddlePaddle: An open-source deep learning platform from industrial practice. Frontiers of Data and Domputing 2019, 1, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Sun, J.; Chen, H.; Li, D. Campo: Cost-Aware Performance Optimization for Mixed-Precision Neural Network Training. In Proceedings of the USENIX Annual Technical Conference; 2022; pp. 505–518. [Google Scholar]

- Micikevicius, P.; Stosic, D.; Burgess, N.; Cornea, M.; Dubey, P.; Grisenthwaite, R.; Ha, S.; Heinecke, A.; Judd, P.; Kamalu, J.; et al. Fp8 formats for deep learning. 2022; arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.05433. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Jaiswal, A.; Yin, L.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Z. Q-galore: Quantized galore with int4 projection and layer-adaptive low-rank gradients. 2024; arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.08296. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Lin, Z.; Toh, K.C.; Zhou, P. Loco: Low-bit communication adaptor for large-scale model training. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2015; pp. 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Faghri, F.; Tabrizian, I.; Markov, I.; Alistarh, D.; Roy, D.M.; Ramezani-Kebrya, A. Adaptive Gradient Quantization for Data-Parallel SGD. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, A.; Pavlov, M.; Goh, G.; Gray, S.; Voss, C.; Radford, A.; Chen, M.; Sutskever, I. Zero-Shot Text-to-Image Generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021; pp. 8821–8831. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; You, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Wang, Z.; Lin, Y. FracTrain: Fractionally Squeezing Bit Savings Both Temporally and Spatially for Efficient DNN Training. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Karimireddy, S.P.; Rebjock, Q.; Stich, S.U.; Jaggi, M. Error Feedback Fixes SignSGD and other Gradient Compression Schemes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019; pp. 3252–3261. [Google Scholar]

- Modoranu, I.; Safaryan, M.; Malinovsky, G.; Kurtic, E.; Robert, T.; Richtárik, P.; Alistarh, D. MicroAdam: Accurate Adaptive Optimization with Low Space Overhead and Provable Convergence. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ding, K.; Toh, K.C.; Zhou, P. Memory-Efficient 4-bit Preconditioned Stochastic Optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.10663, arXiv:2412.10663 2024.

- Fishman, M.; Chmiel, B.; Banner, R.; Soudry, D. Scaling FP8 training to trillion-token LLMs. 2024; arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.12517. [Google Scholar]

- Shazeer, N.; Stern, M. Adafactor: Adaptive Learning Rates with Sublinear Memory Cost. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2018; pp. 4603–4611. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Chen, J.; Zhao, K.; Wang, J.; Jing, L. 1-Bit FQT: Pushing the Limit of Fully Quantized Training to 1-bit. 2024; arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.14267. [Google Scholar]

- Dettmers, T.; Lewis, M.; Belkada, Y.; Zettlemoyer, L. Llm.int8(): 8-bit matrix multiplication for transformers at scale. 2022; arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.07339. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthi, R. Quantizing deep convolutional networks for efficient inference: A whitepaper. 2018; arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.08342. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Wu, Y.; Ni, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wen, H.; Zou, Y. Dorefa-net: Training low bitwidth convolutional neural networks with low bitwidth gradients. 2016; arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.06160. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, K.; Yang, F.; Li, L.; Chen, R.; Hu, X. EXACT: Scalable Graph Neural Networks Training via Extreme Activation Compression. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rastegari, M.; Ordonez, V.; Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. XNOR-Net: ImageNet Classification Using Binary Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; 2016; pp. 525–542. [Google Scholar]

- Chitsaz, K.; Fournier, Q.; Mordido, G.; Chandar, S. Exploring Quantization for Efficient Pre-Training of Transformer Language Models. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2024; pp. 13473–13487. [Google Scholar]

- Harma, S.B.; Chakraborty, A.; Sperry, N.; Falsafi, B.; Jaggi, M.; Oh, Y. Accuracy Booster: Enabling 4-bit Fixed-point Arithmetic for DNN Training. 2022; arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.10737. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Deng, L.; Wu, S.; Yan, T.; Xie, Y.; Li, G. Training high-performance and large-scale deep neural networks with full 8-bit integers. Neural Networks 2020, 125, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liang, C.; Huang, D.; Real, E.; Wang, K.; Pham, H.; Dong, X.; Luong, T.; Hsieh, C.; Lu, Y.; et al. Symbolic Discovery of Optimization Algorithms. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dettmers, T.; Pagnoni, A.; Holtzman, A.; Zettlemoyer, L. QLoRA: Efficient Finetuning of Quantized LLMs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, May 7-9, 2015, Conference Track Proceedings; Bengio, Y.; LeCun, Y., Eds., 2015.

- Seide, F.; Fu, H.; Droppo, J.; Li, G.; Yu, D. 1-bit stochastic gradient descent and its application to data-parallel distributed training of speech DNNs. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association; 2014; pp. 1058–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Feng, B.; Xue, B.; Wang, B.; Wu, B.; Lu, C.; Zhao, C.; Deng, C.; Zhang, C.; Ruan, C.; et al. Deepseek-v3 technical report. 2024; arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.19437. [Google Scholar]

- Dettmers, T. 8-bit approximations for parallelism in deep learning. 2015; arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.04561. [Google Scholar]

- Han, R.; Demmel, J.; You, Y. Auto-precision scaling for distributed deep learning. In Proceedings of the High Performance Computing: 36th International Conference, ISC High Performance 2021, Virtual Event, June 24–July 2, 2021, Proceedings 36. Springer, 2021; pp. 79–97.

- Chen, Y.; Xi, H.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J. Oscillation-Reduced MXFP4 Training for Vision Transformers. 2025; arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.20853. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.; Cai, T. Stabilizing Quantization-Aware Training by Implicit-Regularization on Hessian Matrix. 2025; arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.11159. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, C.; Orr, D.; Luschi, C. Unit scaling: Out-of-the-box low-precision training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2023; pp. 2548–2576. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; Bengio, Y.; LeCun, Y., Eds. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Bae, J.; Kim, B.; Kwon, S.J.; Lee, D. To fp8 and back again: Quantifying the effects of reducing precision on llm training stability. 2024; arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.18710. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Wu, J.; Huang, L. Double Quantization for Communication-Efficient Distributed Optimization. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2019; pp. 4440–4451. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Fei, W.; Huang, Y.; Ding, S.; Dai, W.; Li, C.; Zou, J.; Xiong, H. AMPA: Adaptive Mixed Precision Allocation for Low-Bit Integer Training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J.; Schneider-Kamp, P.; Galke, L. Continual Quantization-Aware Pre-Training: When to transition from 16-bit to 1.58-bit pre-training for BitNet language models? 2025; arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.11895. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Wei, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J. Accurate INT8 Training Through Dynamic Block-Level Fallback. 2025; arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.08040. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.E.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. 2015; arXiv preprint arXiv: 1503.02531. [Google Scholar]

- Banner, R.; Hubara, I.; Hoffer, E.; Soudry, D. Scalable methods for 8-bit training of neural networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2018; pp. 5151–5159. [Google Scholar]

- Dettmers, T.; Lewis, M.; Shleifer, S.; Zettlemoyer, L. 8-bit Optimizers via Block-wise Quantization. 2021; arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.02861. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Choi, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, N.; Venkataramani, S.; Srinivasan, V.; Cui, X.; Zhang, W.; Gopalakrishnan, K. Hybrid 8-bit Floating Point (HFP8) Training and Inference for Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2019; pp. 4901–4910. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, R.; Liu, C.; Huang, D.; Zhou, S.; Guo, J.; Guo, Q.; Du, Z.; Zhi, T.; et al. Fixed-Point Back-Propagation Training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020; pp. 2327–2335. [Google Scholar]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024, 36, 4358–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Zhu, K.; Ye, Z.; Chen, L.; Zheng, S.; Ceze, L.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Chen, T.; Kasikci, B. Atom: Low-bit quantization for efficient and accurate llm serving. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems.

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Systems, 2015. Software available from tensorflow.org.

- Li, Z.; Sa, C.D. Dimension-Free Bounds for Low-Precision Training. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2019; pp. 11728–11738. [Google Scholar]

- Alistarh, D.; Grubic, D.; Li, J.; Tomioka, R.; Vojnovic, M. QSGD: Communication-Efficient SGD via Gradient Quantization and Encoding. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017; pp. 1709–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester, J.J. LX. Thoughts on inverse orthogonal matrices, simultaneous signsuccessions, and tessellated pavements in two or more colours, with applications to Newton’s rule, ornamental tile-work, and the theory of numbers. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 1867, 34, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliassen, S.; Selvan, R. Activation Compression of Graph Neural Networks Using Block-Wise Quantization with Improved Variance Minimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing; 2024; pp. 7430–7434. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Tang, J.; Tang, H.; Yang, S.; Chen, W.M.; Wang, W.C.; Xiao, G.; Dang, X.; Gan, C.; Han, S. Awq: Activation-aware weight quantization for on-device llm compression and acceleration. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems, 2024; 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F.; Gong, R.; Yu, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Yan, J. Towards Unified INT8 Training for Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020; pp. 1966–1976. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Yu, C.; Lian, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, J. DoubleSqueeze: Parallel Stochastic Gradient Descent with Double-pass Error-Compensated Compression. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019; pp. 6155–6165. [Google Scholar]

- Balança, P.; Hosegood, S.; Luschi, C.; Fitzgibbon, A. Scalify: scale propagation for efficient low-precision LLM training. 2024; arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.17353. [Google Scholar]

- Desrentes, O.; de Dinechin, B.D.; Le Maire, J. Exact dot product accumulate operators for 8-bit floating-point deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 26th Euromicro Conference on Digital System Design (DSD). IEEE; 2023; pp. 642–649. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.B.; Filip, S.; Sentieys, O. A Stochastic Rounding-Enabled Low-Precision Floating-Point MAC for DNN Training. In Proceedings of the Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition; 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Liu, D.; Xie, W.; Li, Y.; Ning, X.; Meng, Z.; Zeng, S.; Lei, J.; Fang, Z.; Wang, Y. Towards Accurate and Efficient Sub-8-Bit Integer Training. 2024; arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.10948. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Agrawal, A.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Narayanan, P. Deep Learning with Limited Numerical Precision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; Bach, F.R.; Blei, D.M., Eds. 2015; pp. 1737–1746. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, W.; Dai, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Zou, J.; Xiong, H. Latent Weight Quantization for Integerized Training of Deep Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2025, 47, 2816–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Deng, L.; Yang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, G. Training and inference for integer-based semantic segmentation network. Neurocomputing 2021, 454, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Z.; Cai, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, Z. Trainable Fixed-Point Quantization for Deep Learning Acceleration on FPGAs. 2024; arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.17544. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L.; Anthonissen, M.; Hochstenbach, M.; Koren, B. A simple and efficient stochastic rounding method for training neural networks in low precision. 2021; arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.13445. [Google Scholar]

- Courbariaux, M.; Bengio, Y.; David, J. BinaryConnect: Training Deep Neural Networks with binary weights during propagations. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2015; pp. 3123–3131. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Wang, N.; Chen, C.; Ni, J.; Agrawal, A.; Cui, X.; Venkataramani, S.; Maghraoui, K.E.; Srinivasan, V.; Gopalakrishnan, K. Ultra-Low Precision 4-bit Training of Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Park, E. HLQ: Fast and Efficient Backpropagation via Hadamard Low-rank Quantization. 2024; arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.15102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Huang, S.; Pan, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Xu, Y. Distribution Adaptive INT8 Quantization for Training CNNs. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2021; pp. 3483–3491. [Google Scholar]

- Novikov, G.S.; Bershatsky, D.; Gusak, J.; Shonenkov, A.; Dimitrov, D.V.; Oseledets, I.V. Few-bit Backward: Quantized Gradients of Activation Functions for Memory Footprint Reduction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2023; pp. 26363–26381. [Google Scholar]

- Köster, U.; Webb, T.; Wang, X.; Nassar, M.; Bansal, A.K.; Constable, W.; Elibol, O.; Hall, S.; Hornof, L.; Khosrowshahi, A.; et al. Flexpoint: An Adaptive Numerical Format for Efficient Training of Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017; pp. 1742–1752. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Lee, J.H.; Oh, Y.; Ha, S.; Lee, S. Training deep neural network in limited precision. 2018; arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.05486. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, J.; Hu, W. RaanA: A Fast, Flexible, and Data-Efficient Post-Training Quantization Algorithm. 2025; arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.03717. [Google Scholar]

- Courbariaux, M.; Bengio, Y.; David, J.P. Training deep neural networks with low precision multiplications. 2014; arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.7024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Hu, X.; Zhou, H.; Xu, N. FxpNet: Training a deep convolutional neural network in fixed-point representation. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks; 2017; pp. 2494–2501. [Google Scholar]

- Du, D.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, S.; Guo, J.; Cao, T.; Chu, X.; Xu, N. BitDistiller: Unleashing the Potential of Sub-4-Bit LLMs via Self-Distillation. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024; pp. 102–116. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.E.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Qin, H.; Jacobs, S.A.; Holmes, C.; Rajbhandari, S.; Ruwase, O.; Yan, F.; Yang, L.; He, Y. Zero++: Extremely efficient collective communication for giant model training. 2023; arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.10209. [Google Scholar]

- Drumond, M.; Lin, T.; Jaggi, M.; Falsafi, B. Training DNNs with Hybrid Block Floating Point. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2018; pp. 451–461. [Google Scholar]

- De Dinechin, F.; Forget, L.; Muller, J.M.; Uguen, Y. Posits: the good, the bad and the ugly. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Conference for Next Generation Arithmetic 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Liu, H.; Bian, Z.; Fang, J.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; You, Y. Colossal-ai: A unified deep learning system for large-scale parallel training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 52nd International Conference on Parallel Processing, 2023, pp. 766–775.

- Wortsman, M.; Dettmers, T.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Morcos, A.; Farhadi, A.; Schmidt, L. Stable and low-precision training for large-scale vision-language models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, H.; Cai, H.; Zhu, L.; Lu, Y.; Keutzer, K.; Chen, J.; Han, S. Coat: Compressing optimizer states and activation for memory-efficient fp8 training. 2024; arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.19313. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, D. Dynamically scaled fixed point arithmetic. In Proceedings of the IEEE Pacific Rim Conference on Communications, Computers and Signal Processing Conference Proceedings; 1991; pp. 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal, A.; Vink, D.A.; Venieris, S.I.; Bouganis, C. Multi-Precision Policy Enforced Training (MuPPET) : A Precision-Switching Strategy for Quantised Fixed-Point Training of CNNs. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2020; pp. 7943–7952. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, K.; Ning, X.; Dai, G.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, T.; Zeng, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H. Exploring the Potential of Low-Bit Training of Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2022, 41, 5421–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Fang, C.; Xu, M.; Lin, J.; Wang, Z. Evaluations on Deep Neural Networks Training Using Posit Number System. IEEE Transactions Computers 2021, 70, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Rasoulinezhad, S.; Leong, P.H.W.; So, H.K. NITI: Training Integer Neural Networks Using Integer-Only Arithmetic. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2022, 33, 3249–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Guo, H.; Li, M.; Yang, X.; Ding, Y.; Chandra, V.; Lin, Y. CPT: Efficient Deep Neural Network Training via Cyclic Precision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J.; Xie, C.; Lu, H.; Wang, D.; Feng, H.; Zhang, C.; Sun, B.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; et al. SDP4Bit: Toward 4-bit Communication Quantization in Sharded Data Parallelism for LLM Training. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Gai, Y.; Yao, Z.; Mahoney, M.W.; Gonzalez, J.E. A Statistical Framework for Low-bitwidth Training of Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chmiel, B.; Ben-Uri, L.; Shkolnik, M.; Hoffer, E.; Banner, R.; Soudry, D. Neural gradients are near-lognormal: improved quantized and sparse training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Gong, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, G.; Yang, Z.; Guo, B.; Zha, Z.; Cheng, P. Optimizing Large Language Model Training Using FP4 Quantization. 2025; arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.17116. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.; Vogel, B.; Ahmed, T.; Luk, W. Reducing Underflow in Mixed Precision Training by Gradient Scaling. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2020; pp. 2922–2928. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Wang, H.; Ma, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Huang, S.; Dong, L.; Wang, R.; Xue, J.; Wei, F. The era of 1-bit llms: All large language models are in 1.58 bits. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.17764 2024, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, T.; Yen, I.E.H.; Xu, D. FP8-BERT: Post-Training Quantization for Transformer. 2023; arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.05725. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, A.; Yu, T.; Park, Y. Training LLMs with MXFP4. 2025; arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.20586. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, A.; Lai, Z.; Sun, T.; Li, S.; Ge, K.; Liu, W.; Li, D. Efficient deep neural network training via decreasing precision with layer capacity. Frontiers of Computer Science 2025, 19, 1910355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiemer, M.; Schaefer, C.J.; Vap, J.P.; Horeni, M.J.; Wang, Y.E.; Ye, J.; Joshi, S. Hadamard Domain Training with Integers for Class Incremental Quantized Learning. 2023; arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.03675. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, H.; Li, C.; Chen, J.; Zhu, J. Training Transformers with 4-bit Integers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; Sun, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ding, L.; Tian, X.; Tao, D. On Efficient Training of Large-Scale Deep Learning Models. ACM Computing Surveys 2024, 57, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Optimizer | LP Ready | FP32 Accum. | Dyn. Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| SGD (vanilla) | Partial | Optional | No |

| Momentum SGD | Yes | Yes | No |

| Adam | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8-bit Adam (QAdam) | Yes | No | Yes |

| Adafactor | Yes | Yes | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).