1. Introduction

In contemporary academic discourse surrounding education, the concept of “democratic education” has become a fundamental area of research, highlighting its potential to foster civic participation, critical thinking, and social responsibility among students. This interest reflects broader social changes toward valuing democratic principles not only as political ideals but also as fundamental elements of educational paradigms. The integration of democratic education is increasingly recognized for its role in preparing students to navigate complex social environments, encouraging active participation in civic life, and cultivating a sense of identity in diverse contexts. Despite its recognized importance, the implementation and impact of democratic education remain underexplored, particularly in relation to the diverse experiences and perceptions of university students in different learning environments.

Democratic education, in essence, seeks to empower people through participatory learning processes that emphasise dialogue, critical reflection and interaction with diverse perspectives. This approach is based on the conviction that education should serve as a vehicle for social transformation, equipping learners with the skills necessary to contribute meaningfully to democratic societies. The state of the art in democratic education reveals a growing body of research devoted to exploring its theoretical foundations, pedagogical strategies and outcomes.

Recent studies have highlighted the effectiveness of democratic education in enhancing students’ critical thinking skills, fostering social cohesion and promoting civic participation. However, there remains a notable gap in the literature on students’ multidimensional experiences in democratic educational contexts, particularly in relation to their perceptions, attitudes and identities. According to research trends that do not yet consider how students at different school levels have embodied (cognitively, emotionally and socially speaking) information and communication technologies (ICTs), or how social experiences emphasise their subjective constitution.

This research gap identified in the existing literature is due to the lack of comprehensive studies examining the intersection of democratic education and learners’ experiences in diverse learning environments. For [

1,

2,

3] experience is “what happens to me”, and does not pretend to have a univocal meaning, nor to speak of it in objective terms”, but to think of it as existence, therefore the learners will be the subject of the experience.

While previous research has mainly focused on the outcomes of democratic education, there is a pressing need to delve deeper into the qualitative aspects of student interaction with democratic principles, this is considered because most youth studies address insurgency for example in [

4] receptions of training but lack studies on how citizenship training impacts on the identity of the subject of the experience. This gap poses a challenge for understanding how democratic education influences the conceptual, participatory, pro-social, critical and identity dimensions of learners in analogue, digital and immersive technology contexts. Addressing this gap is crucial to advancing the field of democratic education, as it provides information about learners’ lived experiences and informs the development of more effective educational practices. Addressing this gap in democratic education research is critical for several reasons.

Firstly, it allows for a deeper and more nuanced understanding of how students experience and perceive democratic processes in the educational environment. By examining students’ lived experiences, researchers and educators can identify those aspects of democratic education that are most meaningful and transformative for students, as well as those that may be less effective or even counterproductive.

In addition, this information is invaluable for the development and refinement of more effective and relevant educational practices. By drawing on students’ real-life perspectives and experiences, educators can design and implement pedagogical strategies that resonate more deeply with students’ needs, interests and realities. This not only improves the quality of democratic education, but also increases the likelihood that students will internalise and apply democratic principles in their lives beyond the classroom, thus contributing to the formation of more engaged and participatory citizens in society.

The problem lies in the limited understanding of how students perceive and interact with democratic education in diverse contexts, which hampers the ability to tailor educational interventions to fit their unique needs and experiences. The lack of detailed qualitative data on student experiences limits educators’ ability to design curricula that effectively integrate democratic principles and foster meaningful participation. Therefore, exploration of these dimensions is critical to refining democratic education models and enhancing their impact on student learning and development. The lack of detailed qualitative information about students’ experiences represents a significant obstacle to the development of educational curricula that effectively incorporate democratic principles and promote active and meaningful participation. This lack of data limits the understanding of how students perceive, interpret and engage with democratic concepts in the educational environment. Without a clear picture of these experiences, educators face challenges in adapting their teaching methods and designing activities that truly resonate with students’ needs and perspectives. How can educators encourage meaningful student participation in democratic education programmes?

What factors influence students’ interpretation of and engagement with democratic concepts in educational settings, how can teaching methods be adapted to better align with students’ perspectives and needs in democratic education, what are the key elements needed to design activities that resonate with students’ experiences in democratic education, what are the key elements needed to design activities that resonate with students’ experiences in democratic education, what are the key elements needed to design activities that resonate with students’ experiences in democratic education, what are the key elements needed to design activities that resonate with students’ experiences in democratic education, and what are the key elements needed to design activities that resonate with students’ experiences in democratic education?

It is therefore crucial to conduct in-depth research that explores in depth the dimensions of the student experience in relation to democratic education. This involves examining how students interact with democratic principles in the classroom, how they perceive their role in decision-making processes, and what factors influence their level of engagement and participation. By obtaining this qualitative information, educators will be able to refine democratic education models, adapting them to maximise their impact on student learning and development. This approach will not only improve the effectiveness of educational programmes, but will also contribute to building more engaged citizens who are prepared to participate actively in a democratic society.

The rationale for addressing the topic lies in the potential of democratic education to transform educational practices and empower students as active participants in democratic societies. By exploring students’ multifaceted experiences, this study seeks to contribute to the development of educational strategies that promote inclusion, participation and social responsibility. The overall aim of this research is to explore and understand the perceptions, experiences and attitudes of university students in relation to their participation and learning in different contexts, encompassing the five dimensions of democratic education [

5]. The research question guiding this study was: How do university students perceive and experience democratic education in immersive analogue, digital and technological contexts? The study hypothesised that students’ participation in democratic education varies significantly by context, which influences their conceptual understanding, participatory behaviour, prosocial attitudes, critical thinking and identity formation.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology employed in this study consists of a qualitative research instrument designed for group discussions with university students on democratic education. This instrument seeks to capture students’ perceptions and experiences in diverse contexts, providing a comprehensive and multidimensional view of their civic education. The main findings reveal a complex interplay between students’ participation in democratic education and their learning environments, highlighting the diverse ways in which they internalise and apply democratic principles.

The study aimed to explore university students’ perceptions, experiences and attitudes towards democratic education in analogue, digital and immersive technology contexts. Participants were recruited from a diverse range of academic disciplines at a major public university in Latin America, ensuring a representative sample of the student body. Selection criteria included enrolment in undergraduate or graduate programmes, age between 18 and 30 years, and voluntary participation in the study. Participants were stratified by gender, academic year and field of study to capture a wide range of perspectives. A total of 60 students were selected, comprising 22 males and 38 females, equally distributed across the disciplines of social sciences, humanities, social sciences and humanities.

Data acquisition and description of the data The study employed the “Research Instrument for a Focus Group Discussion with University Students on Democratic Education”, a qualitative tool designed to obtain detailed information about students’ experiences of civic education. The procedure began with an introduction and a welcome segment, where the moderators introduced themselves, explained the objectives of the study, and established the rules of participation. An icebreaker question, “Have you ever run for office before?” was posed to facilitate participants’ participation. Data were collected through group discussions. Discussions were conducted in a controlled environment within the university premises ensuring minimal external disturbances. Sessions were scheduled to last 75 minutes, with a 5-minute introduction, a 60-minute main discussion and a 10-minute closing reflection.

Data were captured through audio recordings and supplemented by moderator’s notes to ensure comprehensive data collection.

Regarding the collection of information, the following dimensions were addressed Dimension 1: Analogical Conceptual Context: Participants discussed the importance of understanding democratic history and institutional power structures, they were invited to reflect on their sources of knowledge and learning environments.

The starting point for the conceptual problematization of citizenship lies in the gap between the directions of academic research and formal educational practices [

6]. The concept of citizenship is intrinsically complex and uniquely shaped by the political and historical context of each country [

6], at a time in history when literacy alone is not enough to achieve the knowledge, skills, and attitudes expected of an active and integrated citizenry in modern societies [

7] This complexity is intensified especially in heterogeneous societies where young people are socialized in segregated schools [

8] or in environments with high political polarization and structural discrimination (Jung and Gopalan 2023). Furthermore, the phenomena of globalization [

9] and the digitalization of society [

10] add new layers of complexity to the concept of citizenship. However, what might seem like an obstacle to addressing the concept of citizenship actually represents an opportunity to bring forward a debate that is more difficult to foster and understand in more homogeneous societies or contexts [

11] In these increasingly connected and diverse societies, there is a lack of a clear model for the type of citizenship being pursued [

12], which leads to offering different levels of opportunity, security, and rights to citizens [

8]. The traditional knowledge in civic education, focused on the understanding of democratic institutions, their structures, and their history, has resulted in a disconnect between civic education and the relevance of democratic participation [

13], as it remains detached from the commitments inherent to global citizenship [

7]. This type of citizenship is personally responsible [

12], able to access necessary information effectively [

10,

13], and is equipped to defend its rights and exercise its duties [

14]; [

6] through the traditional knowledge of civic education [

15] but lacks the skills needed to be socially responsible. In some cases, such education was limited to basic general literacy, grounded in evidence suggesting a positive correlation between literacy and civic engagement [

7]

Digital context: Questions focused on criteria for discerning reliable political information and reliable digital sources. They were guided through the different moments of the discussion to explore participants’ media literacy skills. Immersive technological context: Participants shared experiences with political simulation games such as Age of Empires and Civilization, and discussed learning outcomes related to governance systems.

Dimension 2: Participatory and Analogical Context: Participants recounted interactions with elected officials and their involvement in civic organisations. Discussions explored the motivations and outcomes of such engagements.

Democratic participation is a key factor for social well-being among young people [

16] who, at early stages, show a predisposition toward adopting prosocial behaviors [

9] This requires the implementation of active methodologies, such as cooperative games, that promote a dialogic-democratic relationship [

17] Likewise, it is essential to foster school environments that encourage debate [

8] although this can pose a challenge for teachers in contexts where there are significant ideological differences among students [

15] In summary, a school climate that allows for explanation of the concept of democracy in spaces where students can express themselves freely [

11] and debate issues relevant to their context or to global citizenship [

18] is essential.

Digital context: The focus was on social media campaigns, particularly the use of hashtags to raise awareness. Participants described the experiences and effectiveness of digital activism.

Immersive and technological context: Participants discussed the frequency and purposes of engaging in public affairs discussions on social media platforms.

Dimension 3: Prosocial Analogue context: Participants detailed community service activities and explored motivations and impacts.

The main component of this dimension is based on support for democratic values [

6]. Citizenship Education is linked to democratic values such as the culture of peace [

19], respect for human rights [

20] responsibility towards the environment [

21] the adoption of a culture of peace [

19], as well as freedom, equity, social justice, and the common good [

22] The ultimate goal of acquiring these values is to have citizens willing to promote and defend democracy [

14]. The promotion of prosocial behavior begins by recognizing the value of life in society. Acquiring such behavior, in addition to being beneficial for society, allows the individual to develop a sense of belonging that fosters an understandingof the dynamics of their environment and reinforces the idea that societies progress toward achieving common goals [

16] In this context, immersive methodologies such as role-playing games or political simulations [

9] facilitate a dialectical understanding of social dynamics.

Digital context: Discussions focused on civility in social media interactions, and participants provided examples of prosocial behaviours.

Immersive and technological context: Participants described instances of online assistance or collaboration, highlighting the nature and outcomes of such interactions.

Dimension 4: Analogue critical context: Participants identified controversial issues and discussed social avoidance of critical issues.

From the perspective of active student engagement in class, it is important to identify problems within the school or community [

23] in order to find solutions together [

24] This requires looking beyond the surface to understand the causes of violence, inequality, and poverty [

19] and adopting a positive attitude toward politics [

8]. It is a form of citizenship focused on social justice (Arroyo Mora et al. 2020). Critique demands ongoing responses to social issues [

8] where perseverance transforms political motivations into real social participation [

13]. It is also important to foster critical thinking [

9] that evaluates information within both physical and digital environments [

10] In this way, the development of students’ independent thinking [

6] is seen as key to democratic citizenship [

9]. Working with controversial topics from adult life [

9] allows students to analyze public policies and their impact on daily life. Understanding these issues helps comprehend how decisions influence the structure of societies [

20] (and guide actions toward social change [

19] This dimension prepares students to adopt a political mindset [

6], develop the ability for political participation [

22] and understand the importance of collective action [

9] for social change [

19] and other issues of interest [

15] The digital context has moved much of political activism online [

20] and requires specific training to channel young people’s political will through digital media [

10]

Digital context: Attention focused on the perceived impact of international events on local communities and the veracity of global information.

Immersive technology context: Participants shared experiences of online debate on socially relevant issues.

Dimension 5: Analogue identity context: Discussions explored the effectiveness of democracy in solving social problems and participants’ sense of belonging to diverse geographical entities.

This dimension seeks to create a sense of belonging that drives civic participation [

8,

16] This helps with socialization [

9] and integration into the culture (Arroyo Mora et al. 2020). Participation makes people feel useful to society [

16] enables them to influence political decisions [

22] and makes them feel that their role has a purpose [

11] When people see themselves as part of a group [

20] they are more motivated to contribute to the common good and get involved in the issues facing their community. To promote global citizenship, it is essential to identify with a group that includes all of humanity from a historical perspective [

18] Educational experiences that foster democratic values such as freedom, diversity, equity, or the common good [

22] make people feel part of a community to which they belong, which they respect, and for which they take responsibility.

Digital context: Participants reflected on their interactions with people from different geographical locations on social networks.

Immersive-technological context: Participants described virtual communities with which they felt connected, discussing shared interests and regular interactions.

Data preparation involved verbatim transcription of the audio recordings, ensuring accuracy and completeness. Transcripts were cross-checked with focus group notes to resolve ambiguities and enrich understanding of the context. Data were anonymised to protect participant confidentiality, and identifiers were replaced with coded labels.

3. Resulted

Data analysis was carried out using thematic analysis, facilitated by NVivo software (version 12). The analytic process included coding transcripts to identify recurring themes and patterns across the five dimensions and three contexts. NVivo was used to determine thematic prevalence. Findings were synthesised in order to elucidate comprehensive insights into democratic education experiences, contributing to the broader discourse on civic education and civic participation.

This methodology provides a detailed description of the research process, ensuring replicability and facilitating future studies in the field of democratic education. The research on democratic education among university students revealed several significant findings in all five dimensions (conceptual, participatory, prosocial, critical and identity) within analogue, digital and immersive technological contexts.

Results by Dimension: The conceptual dimension of digital citizenship education shows a strong historical knowledge base and a growing adaptation of students to digital environments. The high percentage of recognition of the importance of traditional historical knowledge (82%) indicates that conventional educational methods remain essential for civic education. However, the integration of digital tools is gaining ground, as evidenced by the use of specific criteria for assessing the credibility of online information (75%) and trust in reputable academic and news sources (68%).

The adoption of immersive technologies, such as historical simulation games (60% participation), indicates a trend towards more interactive and experiential learning methods. This suggests that students are developing skills to understand complex political systems through virtual experiences, thus complementing theoretical knowledge acquired through traditional means. This combination of traditional and digital educational approaches appears to be fostering a deeper and more multifaceted understanding of democracy and its institutions among students.

Knowing the history and structure of democratic institutions: Group 1 results indicate that students consider it important to know democratic history, although they do not delve into historical details. This suggests a lack of connection between historical knowledge and its practical application today. The implication of these findings is that while students recognise the importance of understanding democratic history, there appears to be a gap in their ability to connect historical knowledge with contemporary democratic practices. This disconnect may hinder students’ ability to fully engage with and critically analyse current democratic institutions and processes. To fill this gap, educational strategies could be developed that explicitly link the historical evolution of democracy with current governance structures and challenges

Selecting reliable digital information: In Group 2, the existence of fake news is recognised, and the ability to distinguish truthful information depends on political interest. This highlights the need for more robust education in source verification. Use of virtual simulators or games that recreate historical situations or political systems: The lack of interest in games that simulate democratic processes, mentioned in Group 3, suggests that there is an opportunity to integrate more engaging learning tools that foster knowledge of democracy.

Participatory dimension: In analogue terms, 70 % of students reported direct interaction with elected officials, describing these experiences as enriching and motivating. Participation in civic organisations was frequent, with 65 % participating in community groups, trade unions or political parties. In the digital realm, 80 % of students participated in awareness-raising campaigns through social media, using hashtags to amplify messages. In immersive technological contexts, 55% frequently interacted in online forums to discuss public issues, mainly to exchange information and promote advocacy. Students’ civic participation was significantly manifested in both analogue and digital environments.

In the traditional setting, a substantial majority of students (70%) established direct contact with elected representatives, valuing these interactions as enriching experiences that fostered their civic motivation. In addition, a considerable percentage (65%) were actively involved in various civic organisations, including community groups, trade unions and political parties, demonstrating a tangible engagement with existing participatory structures.

In the digital sphere, student participation was even more pronounced, with 80% of students engaging in awareness campaigns through social media platforms. The strategic use of hashtags to amplify messages suggests a sophisticated understanding of digital communication tools for activism. In addition, more than half of the students (55%) regularly participated in online forums dedicated to debates on public issues, using these virtual spaces not only to exchange information, but also as platforms to promote advocacy. This combination of analogue and digital participation illustrates a comprehensive approach to civic engagement by students, taking advantage of multiple channels to exercise their active citizenship.

Contact with people at the head of a democratic institution: Group 1 participants express that their contact with authorities is limited, which may affect their perception of democracy and their desire to engage in participatory processes. Participating in social associations, NGOs or political parties: The low participation in social organisations, as observed in Group 1, indicates a disconnection with civic activism that could be addressed through initiatives that encourage participation. Informing themselves on social networks about public affairs:

Group 2 mentions that many use social networks for information, but not to actively participate in political debates. This suggests that digital platforms could be used more effectively to foster civic participation.

Engaging in awareness-raising campaigns through social media: While some have participated in campaigns, most do not engage in policy debates, indicating an opportunity to raise awareness and mobilise through these platforms. Interact on social media about public issues:

Interaction on social media is limited, suggesting that a more dynamic environment for debate and discussion on relevant issues could be promoted. Participate in democratically functioning virtual communities: The lack of participation in virtual communities reflects a disconnect with the potential of technology to facilitate democratic participation.

Prosocial dimension: Community service was a common activity, with 78% participating in an analogue way, motivated by the desire to contribute positively to society. In the digital realm, 85% emphasised the importance of civility in social media interactions, providing examples such as respectful discourse and fact-checking.In the area of immersive technologies, albeit with a smaller but still significant percentage, a trend towards collaboration and mutual support was evident. Sixty percent of participants reported assisting their peers in online environments, suggesting the emergence of cohesive and supportive virtual communities. This willingness to help in advanced digital spaces indicates an extension of traditional prosocial values into new technological contexts. Collaborative problem solving and the formation of supportive networks in these immersive environments demonstrate how prosociality adapts and evolves in line with technological advances, while maintaining its essence of contributing to collective well-being.

In the traditional context, community service emerged as a widely adopted practice, with more than three-quarters of participants engaging in face-to-face activities. This high participation rate reflects a strong commitment to collective well-being and a genuine desire to positively impact society. In parallel, in the digital space, there was an even greater emphasis on prosocial behaviours, with 85% of individuals recognising the crucial importance of civility in online interactions. This underlines a collective awareness of the need to maintain a healthy and respectful digital environment.

Engaging in community service activities: The results from Group 3 show that, although there is participation in community activities, it is occasional and motivated by personal interests. This suggests that a more consistent commitment to community service needs to be encouraged.

Civic behaviour in social networks: Participation in social networks is limited to information and does not translate into civic action, indicating that work should be done to promote active civic behaviour in the digital environment. Service-Learning Projects on inverse platforms: The lack of use of immersive platforms for learning projects suggests an opportunity to integrate learning experiences that connect students to their community.

Students demonstrated a keen awareness of controversial and topical issues, with a significant majority (72%) noting the importance of addressing issues such as climate change and social justice. These issues, despite their relevance, are often avoided in public and educational discussions, suggesting a gap between students’ concerns and the content addressed in their academic environments. The perception of international events as impactful by 65% of students reflects a growing global awareness, but also raises questions about the reliability of the information received and its interpretation in local contexts.

The active participation of more than half of the students (58%) in debates on relevant social issues through social networks indicates a significant engagement with immersive technology as a platform for critical discourse. This phenomenon underlines the importance of digital media in shaping opinions and fostering critical thinking among young people. The convergence of controversial issues, international events and digital participation suggests an evolving educational landscape, where students are not just passive recipients of information, but active participants in the discussion and analysis of complex issues affecting global society.

Knowledge of controversial issues: Group 1 participants mention that their knowledge of political issues is limited, suggesting the need to encourage critical analysis of controversial issues. Critical analysis of traditional texts and media: the lack of critical analysis in information consumption.The text discusses findings from a study involving a group of participants (Group 1). These participants reported limited knowledge of political topics. This suggests the need to encourage more critical analyses of controversial issues.

The text also mentions the importance of critically analyzing the texts and traditional media. It points out that there is a lack of critical thinking when people consume information.In simpler terms, the study found that:

1. People in the group don’t know much about politics

2. This shows we need to help people think more deeply about complex topics

3. It’s important to carefully examine what we read and see in the media4. Currently, people often don’t question or analyze the information they receive

Group 2, highlights the importance of developing critical skills in media analysis.Critical digital news and content analysis: The need for deeper analysis of digital information is evident, suggesting that educational strategies that foster critical thinking should be implemented. Linking global issues to the community: The disconnect between global issues and their local impact, mentioned in Group 2, indicates that work needs to be done on raising awareness of how global issues affect the local community.

Participate in digital environments for debate on socially relevant issues: The lack of participation in digital debates suggests that a more inclusive and accessible environment for dialogue on relevant issues should be encouraged.

Identity dimension: A sense of belonging was evident, with 70% expressing stronger ties to their local community than to national or continental identities. Digital interactions were mainly local, with 68% connecting with people from their city or country. In immersive technology environments, 62% maintained regular contact with virtual communities that shared common interests or goals.The identity dimension reveals a strong local connection among participants, with a significant majority expressing stronger ties to their immediate community than to broader identities. This phenomenon extends to the digital realm, where interactions are mainly focused on local and national connections. The preference for local suggests that, despite globalisation and digital connectivity, people continue to value and prioritise close community relationships and identity.

In the context of immersive technology, there is an interesting trend towards the formation of virtual communities based on shared interests. More than half of the participants maintain regular contact with these groups, indicating an evolution in the way identities are constructed and maintained in the digital space. This suggests that immersive technologies are creating new spaces for identity and community formation, co-existing with traditional local connections, thus broadening the spectrum of personal and collective identity in the digital age.

Sharing democratic values: The results from Group 1 indicate that there is a lack of identification with democratic values, suggesting that work should be done to promote a stronger democratic culture. Sense of belonging to the local community: The perception of a superficial link to the community, as observed in Group 3, suggests that a stronger sense of belonging should be fostered among students. Sense of belonging to the global community: The lack of connection to the global community, mentioned in Cluster 2, indicates that work needs to be done on raising awareness of global interconnectedness and its local impact. Sense of belonging to the virtual community:

Disconnection with the online community suggests that online spaces should be created that encourage participation and a sense of belonging. Specific Findings: In summary, our findings demonstrate that democratic education significantly influences students’ civic engagement and critical thinking in multiple contexts, suggesting that the integration of diverse educational modalities could enhance civic competence and identity formation.

The process of triangulating the results of the focus groups with the proposed dimensions and taxonomies, providing a comprehensive view of students’ perceptions and experiences of democracy, technology and community. Triangulation allows for deeper analysis and a richer understanding of the data, which can guide future interventions and educational strategies.

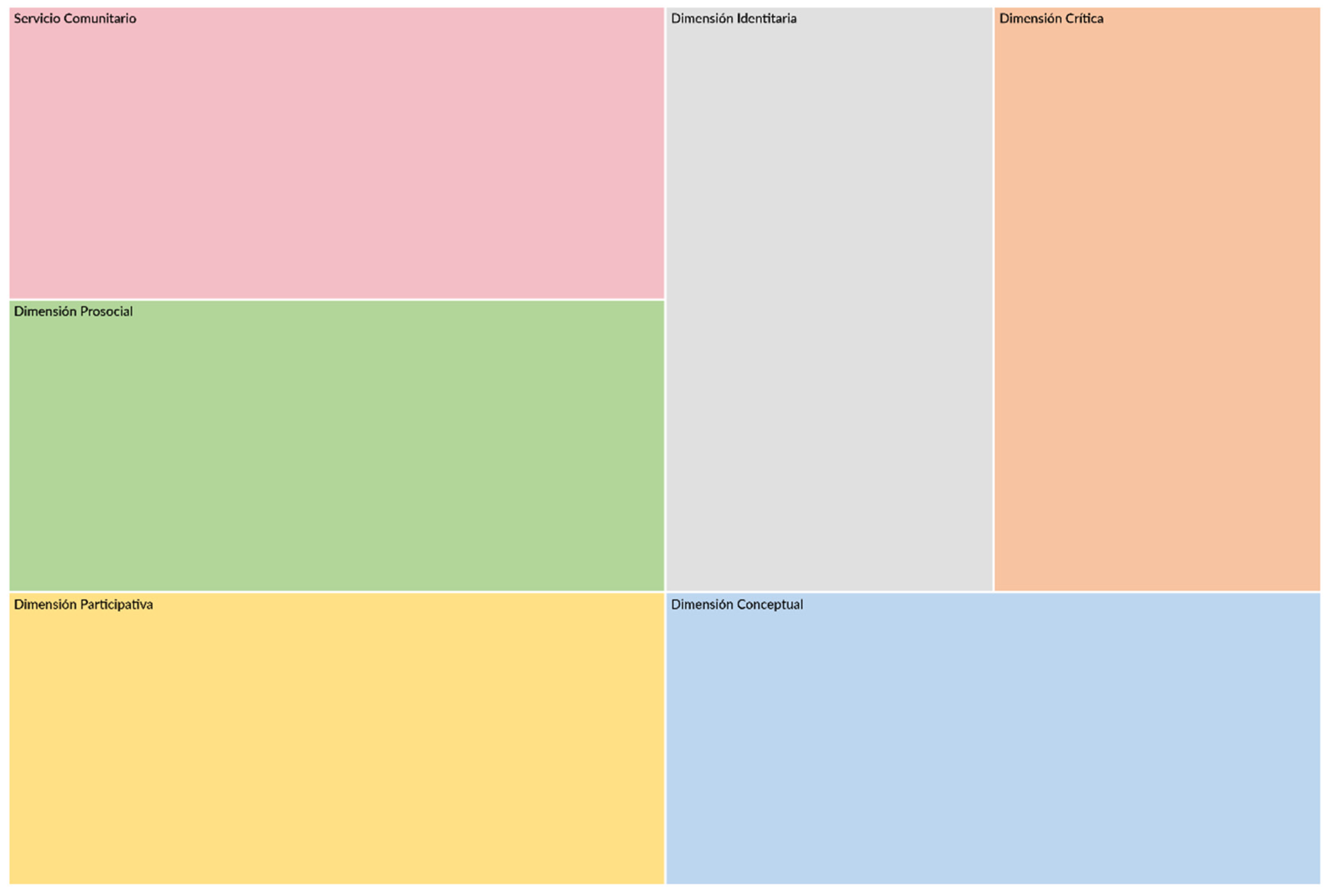

Figure 1.

Own construction. Frequency load in categories.

Figure 1.

Own construction. Frequency load in categories.

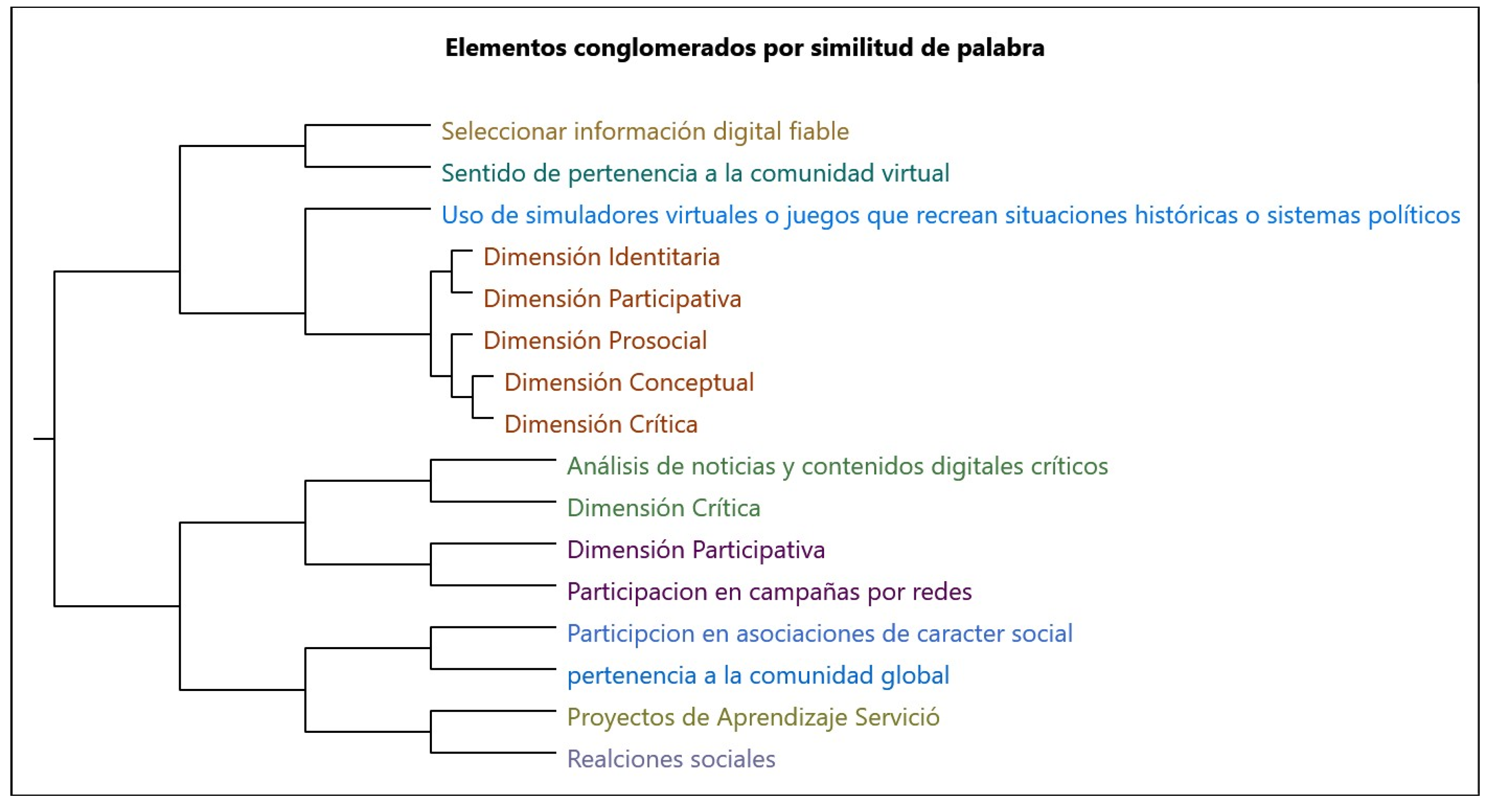

Figure 2.

Own construction, cluster analysis according to categories of analysis.

Figure 2.

Own construction, cluster analysis according to categories of analysis.

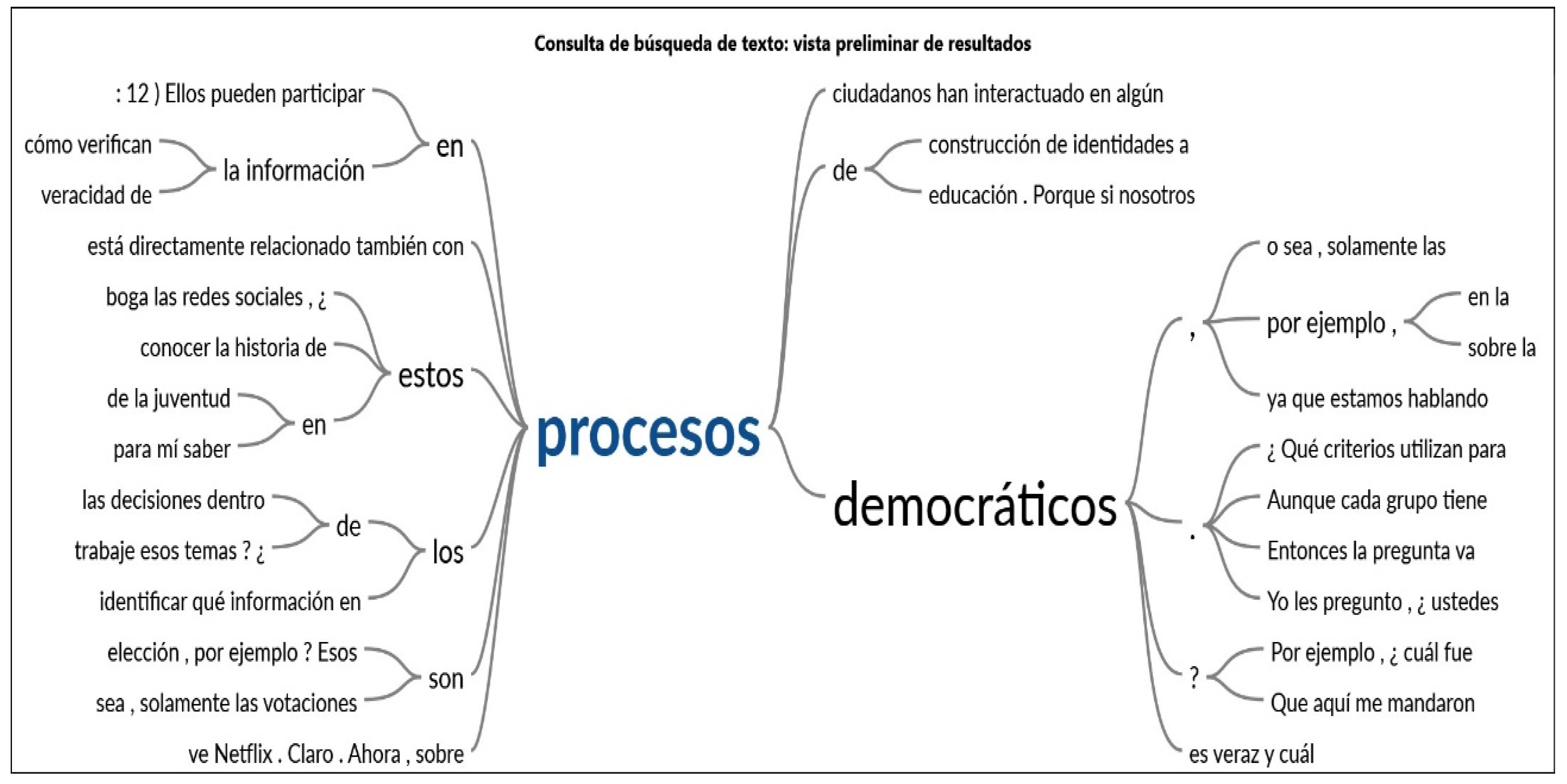

Figure 3.

Own construction, significance results of Democratic Processes.

Figure 3.

Own construction, significance results of Democratic Processes.

4. Discusión

The concept of democratic education is deeply rooted in the principles of civic engagement, critical thinking and participatory democracy, which are essential for developing informed and active citizens. This study investigated university students’ perceptions and experiences of democratic education in analogue, digital and immersive technology contexts. By exploring these dimensions, the study contributes to a comprehensive understanding of how educational environments influence civic learning and participation. The findings offer insights into the multidimensional nature of democratic education, highlighting its relevance for fostering a holistic civic identity in students (Hindess, 1991).

The key findings of the study indicate a nuanced understanding of democratic education among university students. Participants demonstrated a deep awareness of the importance of historical knowledge and institutional power structures, acquired primarily through traditional analogue contexts. Digital environments were recognised for their role in discerning reliable political information and facilitating civic participation through social media campaigns.

Immersive technology experiences, such as political simulation games, were found to enhance students’ understanding of governance systems, suggesting a potential for integrating these tools into educational curricula. These findings underline the novelty of the study, as they highlight the diverse ways in which students interact with democratic education in different contexts. The results of this study have significant implications for the design of educational programmes in democracy and citizenship. The combination of traditional and digital methods in teaching could enhance comprehensive understanding of democratic systems among university students. In addition, the incorporation of immersive technologies, such as political simulation games, into educational curricula could enhance experiential learning and active civic participation. These findings suggest the need for a multifaceted pedagogical approach that integrates analogue and digital resources to effectively prepare future citizens for an increasingly complex and technologically advanced world.

The results of the study can be explained by a number of theoretical and contextual factors. The emphasis on historical knowledge and institutional structures reflects the traditional focus of democratic education on civic literacy and understanding democratic processes. In conclusion, this study reveals the persistence of traditional approaches to democratic education, with a strong emphasis on historical knowledge and institutional structures. These findings underline the continuing importance of civic literacy and understanding of democratic processes in current educational programmes. However, they also raise questions about the need to evolve towards more holistic methods that address the complexities of contemporary democracy. Future studies could explore innovative strategies for balancing theoretical knowledge with practical skills of civic participation, thus adapting democratic education to the challenges of the 21st century.

The role of digital environments in information literacy and civic engagement aligns with contemporary theories of digital literacy and participatory democracy, which emphasise the importance of critical thinking and active participation in digital spaces. Immersive technological experiences offer a unique perspective on experiential learning, suggesting that interactive and engaging tools can enhance students’ understanding of complex governance systems. These explanations provide a theoretical framework for interpreting the study’s findings and highlight the potential for innovative educational practices in democratic education.

Comparison of the study’s findings with previous research reveals several similarities that reinforce its validity. Studies on democratic education have consistently emphasised the importance of civic literacy and participation, in line with participants’ focus on historical knowledge and institutional structures. Research on digital literacy and participatory democracy supports the role of digital environments in fostering critical thinking and civic engagement, highlighting the importance of social media campaigns and information discernment. The use of immersive technology tools for experiential learning is supported by studies on interactive and engaging educational practices, which emphasise their potential to enhance students’ understanding of complex systems. These comparisons demonstrate the consistency of the study’s findings with existing literature, which reinforces its validity and relevance.

However, the study also presents discrepancies with previous research that provide new insights. While traditional democracy education has focused primarily on analogue contexts, the study highlights the growing importance of immersive digital and technological environments in shaping students’ learning and civic engagement. This shift reflects broader trends in education and society, and emphasises the need for innovative and multidimensional approaches to democratic education, that encompasses various aspects of the educational process. This approach involves integrating multiple teaching methods, resources, and learning experiences to foster democratic values and practices in students. It may include the use of digital technologies, project-based learning, classroom debates, simulations of democratic processes, and participation in community activities.

Moreover, a multimodal approach in democratic education seeks to develop critical skills such as analytical thinking, effective communication, conflict resolution, and collaborative decision-making. This method recognizes that democracy is not limited to electoral processes, but covers a wide range of social and civic interactions. Therefore, multimodal democratic education strives to create an inclusive and participatory learning environment that reflects democratic principles in daily practice, preparing students to be active and engaged citizens in a democratic society by combining traditional and innovative pedagogical strategies to address the complexities of civic engagement in digitalized societies.

The study’s findings challenge conventional notions of democratic education, suggesting that the integration of immersive digital and technological tools into educational curricula can improve students’ civic literacy and participation. These discrepancies underline the novelty of the study and highlight its contribution to the advancement of knowledge in this field.

The study acknowledges limitations in experimental design and data collection, which may restrict the generalisability of the findings. The qualitative nature of the study and the focus on university students may limit the applicability of the results to other educational contexts or demographic groups. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into the multidimensional nature of democratic education and its relevance for fostering civic participation and identity among students. By addressing these limitations, future research can build on the study’s findings and explore the long-term impact of innovative educational practices on civic learning and participation.

5. Conclusions

The findings demonstrate that digital environments facilitate the development of skills to discern reliable political information and participate in civic initiatives, while immersive technologies, such as governance simulators, enhance the structural understanding of democratic systems. These results underline the relevance of adapting educational approaches to current technological dynamics, integrating digital and immersive tools to strengthen citizenship education. In conclusion, the evidence presented highlights the fundamental role of digital and immersive technologies in strengthening civic education and citizen participation. The integration of these tools into educational processes not only improves individuals’ ability to critically evaluate political information, but also provides a deeper understanding of democratic systems. It is imperative that education systems evolve to incorporate these technological innovations, thus ensuring more effective citizenship education adapted to the realities of the 21st century.

The five dimensions analysed (conceptual, participatory, prosocial, critical and identity) showed contextual variations in the internalisation of democratic principles. For example, the critical dimension was notably strengthened in digital spaces through the analysis of disinformation, while the identity dimension was consolidated in analogue experiences through face-to-face interaction. This suggests that democratic education requires a multimodal approach, combining traditional and innovative pedagogical strategies to address the complexities of civic engagement in digitised societies.

While the study provides valuable insights, its qualitative design and regional sample limit the generalisability of results. Future research could broaden the geographical diversity, incorporate mixed methods (quantitative-qualitative) and explore the long-term impact of these practices on post-university civic behaviour. In conclusion, this work reinforces the transformative role of democratic education by demonstrating its capacity to adapt to emerging environments, fostering critical, participatory and socially responsible citizens in a world in constant technological and social evolution

References

- J. Larrosa, «La experiencia y sus lenguajes.,» de Conferencia impartida en la Universidad, Barcelona, 2003.

- J. Larrosa, «Experiencia y alteridad en educación,» de Experiencia y alteridad en educación, Rosario, Homo Sapiens, 2011, pp. 13-44.

- J. Larrosa, «Sobre la experiencia,» Aloma. Revista de Psicología, Ciències de la Educación, vol. 19, pp. 87-112, 2006.

- B. Arditi, «Las insurgencias no tienen un plan: ellas son el plan. Performativos políticos y mediadores evanescentes en 2011,» Media and Cultural Studies, vol. 1, nº 1, pp. 147-169, 2012.

- J. M. Gustavo Rojas Ayala¸Linda Nathan, «El estudio de las escuelas democráticas y su contribución a la revitalización de la democracia,» Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, vol. LIV, nº 1, pp. 93-112, 2024.

- M. J. Rodrigues, «Educação em ciências no contexto da cidadania global La educación científica en el contexto de la ciudadanía global,» RELAdEI, vol. 11, nº 1, pp. 12-23, 2022.

- L. W. Anderson, « Civic Education, Citizenship, and Democracy,» Education Policy Analysis Archives, vol. 31, nº 103, pp. 1-16, 2023.

- Robinson-Pant, «Literacy: A Lever for Citizenship?,» International Review of Education, vol. 69, pp. 15-30, 2023.

- O. Akirav, «Active Civic Education Using Project-Based Learning and Attitudes towards Civic Engagement,» Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, vol. 17, nº 1, 2023.

- E. L. J. C. y. L. C. Body, «Mapping Active Civic Learning in Primary Schools across England—A Call to Action,» British Educational Research Journal, vol. 50, nº 3, pp. 1308-1326, 2024.

- M. J. y. A. V. S. d. I. E. Contreras Pardo, «Educación ciudadana y el uso de estrategias didácticas basadas en TIC para favorecer el desarrollo de competencias en ciudadanía digital en estudiantes,» Cuadernos de Investigación Educativa, vol. 13, nº 2, 2022.

- Y. Nonoyama-Tarumi, «Challenges in Fostering Democratic Participation in Japanese Education,» Education Policy Analysis Archives, vol. 31, nº 106, pp. 1-19, 2023.

- E. B. C. T. J. C. M. C. y. D. S. Arroyo Mora, «Prácticas innovadoras en educación ciudadana. ¿Qué dicen las revistas académicas españolas?.,» Revista Fuentes, vol. 2, nº 22, pp. 212-223, 2020.

- Jung, Jilli, y Maithreyi Gopalan, «The Stubborn Unresponsiveness of Youth Voter Turnout to Civic Education: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from State-Mandated Civics Tests,» 2023. [En línea]. [Último acceso: 16 de enero de 2023 ENERO 2023]. Available online: https://osf.io/fzjhu.

- P. G. B. L. M. L. y. J. D. S. Fitchett, «How and Why Teachers Taught About the 2020 U.S. Election: An Analysis of Survey Responses From Twelve States,» AERA Open, vol. 10, nº 1, pp. 1-17, 2024.

- M. Á. y. A. F. M. R. Albalá Genol, «The Social Well-being of Teachers during their Training: the Role of Citizenship and Participation,» International Journal of Sociology of Education, vol. 11, nº 2, pp. 128-150, 2022.

- J. P. R. Garrido, «Currículum, Educación Física y Formación Ciudadana en Chile: oportunidades curriculares que promueven una ciudadanía activa y democrática,» Educación Física y Ciencia, vol. 25, nº 4, 2023.

- J. K. Viola, «Belonging and Global Citizenship in a STEM University,» Education Sciences, vol. 11, nº 12, 2021.

- V. y. M. L. Silva, «Educating for Global Citizenship and Peace through Awakening to Languages: A Study with Institutionalised Children,» Porta Linguarum Revista Interuniversitaria de Didáctica de Las Lenguas Extranjeras,, nº 40, pp. 181-197, 2023.

- T. R. y. M. H. Byerly, «Expansive Other-Regarding Virtues and Civic Excellence,» Journal of Moral Education, vol. 52, nº 1, pp. 95-107, 2023.

- Gil Salom, «Forward to USR in scientific-technical contexts: German as a foreign language via service-learning,» REDU. Revista de Docencia Universitaria, vol. 20, nº 1, pp. 187-204, 2022.

- y. C. G. Cox, «Chile’s Citizenship Education Curriculum:,» Encounters in Theory and History of Education, vol. 22, pp. 206-226, 2021.

- J. J. y. M. O. F. Salinas Valdés, «Educate citizens through take action on community problems,» Praxis Educativa, vol. 24, nº 1, pp. 1-14, 2020.

- Y. y. A. P. Romero, «Fostering Citizenship and English Language Competences in Teenagers Through Task-Based Instruction,» Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, vol. 23, nº 2, pp. 103-120, 2021.

- A. Á. A. N. &. O. R. M. d. R. Torres Bugdud, «La educación para una ciudadanía democrática en las instituciones educativas: Su abordaje sociopedagógico.,» Revista Electrónica Educare, vol. 17, nº 3, pp. 151-172., 2013.

- F. (. García Gutiérrez, «Teoría y política de la educación: Reflexiones para el proceso formativo. Polis (Santiago),,» vol. 11, nº 33, pp. 475-479., 2012.

- C. &. S. R. C. L. Guzmán Gómez, « Experiencias, vivencias y sentidos en torno a la escuela y a los estudios: Abordajes desde las perspectivas de alumnos y estudiantes.,» Revista mexicana de investigación educativa, vol. 20, nº 67, pp. 1019-1054., 2015.

- R. A. Guerra Molina, «2017). ¿Formación para la investigación o investigación formativa? La investigación y la formación como pilar común de desarrollo.,» Boletín virtual Redipe, vol. 6, nº 1, pp. 84-89, 2017.

- M. N. B. R. L.-E. O. y. A. C. Vergara, «Prácticas para la formación democrática en la escuela: ¿Utopía o realidad?.,» Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud,, vol. 9, nº 1, pp. 227-253., 2011.

- L. &. B.-G. R. Bustos-Lira, «Brecha entre las prácticas integradoras e inclusivas desarrolladas por los docentes para la adaptación académica de los estudiantes migrantes en región de Frontera. Estudios pedagógicos,» Estudios Pedagógicos, vol. 1, nº 50, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).