1. Introduction

The integration of eco-social competences into educational curricula has become a priority to face the environmental, social, and economic challenges of the 21st century, as stated in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda (UN, 2015) [

1]

Although each country establishes its own guidelines and levels of detail, there is international consensus on prioritising the well-being and all-round development of children in early childhood education (ECE) through the learning of key competences such as personal, social, civic, and learning to learn competences (Bennett, 2005 [

2]; DOGC, 2023) [

3].

This study aims to develop and validate a scale to measure eco-social competences in children aged 5-6 years. The design process and initial validation of a multidimensional measurement instrument based on a solid theoretical framework are presented. It integrates international references such as the 2030 Agenda (UN, 2015) [

1], PISA 2018 (Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2018) [

4], the CARE-KNOW-DO pedagogical model (Okada & Gray, 2023) [

5], GreenComp, the European sustainability competence framework (Bianchi et al., 2022) [

6], as well as national and curriculum references for ECE. All of them enable structuring assessment based on the cognitive, affective, and behavioural dimensions of the selected eco-social competences from an integrated view of sustainability.

The rubric proposed incorporates transversal or soft skills essential for sustainable development, closely linked to the key competences defined by UNESCO in the field of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) (Leitch, et al., 2018) [

7]. Competences such as social responsibility and ethical sense, critical thinking, entrepreneurship, and diversity/interculturality are addressed in a cross-curricular manner through indicators that can be observed in daily educational practice. The instrument does not only measure conceptual knowledge, but also children’s ability to apply eco-social values in real situations adapted to their development stage from an educational perspective.

The rubric enables obtaining objective data for the continuous improvement of educational programmes. It also contributes to the advancement of research in education for sustainability (EfS), and to strengthening transformative education (UNESCO, 2020, [

8] 2022 [

9]).

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Teachers’ Perceptions and Challenges in the Integration of Eco-Social Competences

The climate crisis, biodiversity loss, and social and economic inequalities require a transformative educational response in line with the holistic nature of ESD (UN, 2015 [

1]; UNESCO, 2018 [

10]). This implies simultaneously addressing the three pillars of sustainability: the environmental, social, and economic dimension.

The growing awareness of the importance of integral sustainability has led to an international consensus on the need to incorporate eco-social competences at different education levels (DOGC, 2022 [

11]; UN, 2015 [

1]). These competences, which integrate knowledge, skills, and attitudes are key to preparing students for global challenges, and to training critical, responsible citizens committed to the common good.

According to a UNESCO survey of over 58,000 teachers around the world, 40% report difficulties in assessing students on issues related to sustainability due to a lack of appropriate instruments (UNESCO, 2020 [

8]; 2022 [

9]). This fact highlights the urgent need for resources to facilitate meaningful assessment consistent with the values and objectives of transformative education. Scientific research on EfS tends to focus mainly on the environmental pillar (Güler et al., 2021) [

12], often ignoring the social-ethical dimension. With the aim of bridging that gap, this study presents a specific holistic tool to assess eco-social competences in ECE, considered the key stage for shaping values, attitudes, and long-lasting habits (Foschi, 2020; Piaget, 1981; UNESCO, 2023 [

13,

14,

15])

2.2. Normative and International Framework for EfS and Global Citizenship

Recent international reports and studies stress the need to strengthen the integration of what is known as “global competence” (OECD, 2018 [

16]) and eco-social competences in education (DOGC, 2023 [

3]), especially at the early stages. The UNESCO report (2022) [

9] on teachers’ perceptions of ESD and Global Citizenship Education (GCED) shows that numerous teachers feel more confident teaching cognitive skills than promoting behavioural learning and socio-emotional dimensions, especially in the field of EfS. This situation shows the need to reinforce teacher training and provide specific tools to address all dimensions of learning linked to global challenges.

Other regulatory frameworks such as the 2030 Agenda (UN, 2015 [

1]) and the latest educational legislation in Spain and Catalonia (BOE, 2022 [

17]; DOGC, 2023 [

3]) insist on the importance of assessing and improving the integration of these competences from a comprehensive, interrelated, and cross-curricular approach. This implies promoting comprehensive training that includes both EfS and education linked to global citizenship, considering all the individual’s (cognitive, affective, and behavioural) dimensions.

ESD and GCED aim to develop competences that empower individuals to reflect on their own actions, taking into account their current and future social, cultural, economic, and environmental impacts from a local and a global perspective (UNESCO, 2017 [

18]; Rieckmann, 2018 [

19]). The need for an education that enables critical reflection and responsible action in a complex interconnected world is hence emphasised.

Along the same lines, the Global Report on Early Childhood Care and Education (UNESCO and UNICEF, 2024 [

20]) highlights the importance of developing socio-emotional competences from early childhood onwards, and calls for the creation of specific tools to measure them. Therefore, defining which eco-social competences can be developed in ECE, and having instruments to assess them is essential to collect objective data, improve pedagogical practice, and make progress in educational research in this field (Okada & Gray, 2023) [

5].

The literature review, both of academic sources and international organisations, compiles various proposals for sustainability competences, global citizenship, or global competence (OECD, 2018 [

16]). It analyses their convergences in order to develop a simple inclusive instrument. The following phases were used for the literature review and summary of competences:

2.2.1. 1st Phase: Compilation of Sustainability Competences

In this phase, all publications on sustainability competences and the summary of these competences were analysed (Albareda et al, 2020 [

21]; CRUE, 2012 [

22]). Those competences were gathered from international reports on sustainability competences, International Professional Standards for Teachers (AITSL, 2022 [

23]; Sleurs, 2008 [

24]; UNECE, 2013 [

25]; UNECE, 2016 [

26]; UNESCO, 2005, 2014, 2016 [

27,

28,

29], 2017 [

18]), and publications by experts in Sustainability and EfS (Barth et al, 2017 [

30]; Wiek et al, 2011 [

31]; Rieckmann, 2012 [

32]).

GreenComp, the European sustainability competence framework (Bianchi et al., 2022) [

6], although designed for all education levels, provides a transferable and globalising view, structuring sustainability competence into four key areas: embodying sustainability values, embracing complexity in sustainability, envisioning sustainable futures, and acting for sustainability. It places emphasis on skills such as collaboration, resilience, and responsible decision-making, aspects that can be worked on from ECE onwards through conflict resolution, participation in assemblies, and carrying out collective projects.

In almost all competences, each of the dimensions of sustainability and their corresponding holistic view was considered. This first phase aimed to be as exhaustive as possible, not leaving out any transversal sustainability competences or SDGs.

2.2.2. 2nd Phase: Compilation of a Global Competence Framework

The same process was repeated with the global competence, or competence for global citizenship (Boix Mansilla & Duraising, 2007; Boix Mansilla et al, 2013; Boix Mansilla & Jackson, 2022; Deardorff, 2009; UNESCO, 2015 [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]), summarised in the OECD (2018) [

16] documents and in the report of the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (2018) [

4] showing the PISA results for Spain.

2.2.3. 3rd Phase: Convergence Between Sustainability Competences and Global Competence

Once the two main groups of competences were identified and organised, their convergences and overlaps were analysed. This analysis was based on the most recent frameworks regarding global competence. The documents indicate global competence should integrate different areas of action, among which sustainability occupies a prominent place (OECD, 2018) [

16].

2.2.4. 4th Phase: Summary of Competences and Adaptation to ECE

The last phase aimed to summarise the competences, trying to avoid repetition and adapting the definitions of the competences to ECE. Several international frameworks have defined and structured these competences adopting a multidimensional and cross-curricular approach, stressing their importance in ECE (UNESCO, 2018 [

10]; Bianchi et al., 2022 [

6]; Okada & Gray, 2023 [

5]).

In essence, “eco-social competence” can be defined as the ability to act using knowledge, ethics, and responsibility, both ecologically and socially, recognising the intrinsic connection between environmental and social responsibility, as well as the impact of one’s own actions on the planet and on communities.

2.3. The Role of Eco-Social Competences in Shaping Habits in ECE

ECE is a fundamental stage in the shaping of habits, values, and attitudes that will last a lifetime (UNESCO, 2018 [

10]; Department of Education, 2023 [

3]). The Catalan ECE curriculum (Decree 21/2023) [

3] explicitly links eco-social competences with environmental sustainability, coexistence, and social responsibility, integrating them in a natural manner into daily routines and activities.

According to the above references, shaping eco-social habits in ECE is specified in the early introduction of values, such as respect for the environment, empathy, and cooperation. When incorporated from a very young age, these values are internalised and become part of children’s daily lives. This process takes place through global and meaningful learning. Eco-social competences are developed through activities, projects, and stories that awaken children’s curiosity about the environment, and help them understand their role in the world. Nursery school, a safe environment, facilitates experimentation and the consolidation of habits related to coexistence, mutual respect, and care for the environment while promoting personal and social responsibility. It encourages children to take care of their immediate surroundings, and to become aware of the impact of their actions on others and on the environment. Collaboration with families is also essential to strengthen and consolidate these habits and values, ensuring coherence between school and home, and facilitating the transfer of learning to children’s daily lives.

Specialised literature stresses the importance of an eco-social education from early childhood onwards, highlighting the need for a holistic approach that combines emotional, ethical, cognitive, and practical dimensions. Herrero (2020) [

38] argues that eco-social education should start at the earliest stages of learning, aimed at shaping citizens committed to social and environmental justice. The author places emphasis on experience and critical reflection, while promoting values such as care, solidarity, and collective responsibility. This perspective requires the integration of an affective and ethical dimension into education, key for including indicators of empathy, responsibility, and active participation in the assessment rubric. Along the same lines, Agundez (2023) [

39] analysed how philosophy for children can contribute to eco-social education, promoting their critical thinking, questioning mind, conversational capacity, and collective reflection on ethical and environmental issues. This philosophical practice fosters autonomy, empathy, and the ability to deal with the complexity of the world, criteria that should also be part of the assessment of eco-social competences.

Gutiérrez Bastida (2024) [

40], for his part, considers the eco-social crisis as the driving force behind a new educational narrative focused on transformative action. The author defends the need for an eco-social ethic, and proposes criteria for identifying educational practices that promote student leadership, critical understanding of reality, and active participation in the construction of a fairer and more sustainable society. These contributions justify the need for instruments that allow for a holistic and contextualised assessment of the development of these competences in ECE.

Despite conceptual advances and the rapid increase of international frameworks, there is a lack of practical, validated instruments adapted to ECE to assess the development of eco-social competences (UNESCO, 2022) [

9]. The most recent proposals focus on the integration of soft skills and the link with the key competences for sustainability identified by UNESCO (2018) [

10], responding to the need for formative, observational, and age-appropriate assessment.

Incorporating eco-social competences in ECE promotes holistic development in children, and contributes to the construction of a more sustainable, equitable, and cohesive society. This review justifies the urgent need for specific, practical, and validated instruments that assess these competences in real ECE contexts.

2.4. CARE-KNOW-DO Pedagogical Model and Assessment Framework

Based on this theoretical review, there is an urgent need for specific, practical, and validated tools that allow for the assessment of the development of eco-social competences in ECE, using a multidimensional (cognitive, affective and pragmatic) approach.

One of the most recent and influential pedagogical models in the field of EfS is CARE–KNOW–DO (Okada & Gray, 2023 [

5]; Okada et al., 2025 [

41]). It provides a sequential and integrating framework based on three interdependent axes: CARE, KNOW, and DO. This model first proposes the development of emotional intelligence, empathy, and ethical sensitivity towards others and the planet. In ECE, those aspects are dealt with in activities of care, respect, and connection with the social and natural environment. Second, it focuses on acquiring relevant knowledge of sustainability, biodiversity, interdependence, and the sustainable development goals (SDGs), which are introduced in a contextualised and understandable manner for children. Finally, it emphasises action, promoting responsible habits, cooperation, and active participation in projects that connect learning with real actions, such as school gardens, recycling, or classroom assemblies.

Several studies have shown the effectiveness of this model in the early stages of learning, highlighting the emotional axis (CARE) acts as a key mediator between knowledge and behaviour: emotional engagement does not only enhance understanding, it is also decisive in transforming knowledge into action [

5]; Okada, 2024 [

42]). This premise is particularly important in ECE, where emotional experience constitutes the basis for the development of lasting values (UNESCO, 2022). As Okada & Gray (2023) [

5] point out, “the CARE–KNOW–DO model offers a holistic pedagogical framework for climate change and sustainability education, integrating emotional engagement (CARE), knowledge acquisition (KNOW), and transformative action (DO).” Okada (2024) [

42] emphasises “this pedagogical model fosters transversal skills such as empathy, critical thinking, and agency, and is especially suitable for early childhood and primary education contexts.” Furthermore, recent research confirms emotional engagement is an essential mediating factor between cognitive understanding and behavioural change (Okada, 2024) [

42].

In the context of this study, the original sequence of the model (CARE-KNOW-DO) was changed to KNOW–CARE–DO to align it with the assessment logic: it is first observed whether children are aware of aspects related to sustainability or not; then, if they show emotional or evaluative engagement, and finally, if they act accordingly. This adaptation responds to the idea that knowledge is transformed into action through emotion, and facilitates rigorous and progressive observation of competence development in children.

The relevance of the CARE–KNOW–DO model is reinforced by its alignment with other international frameworks, such as GreenComp (Bianchi et al., 2022) [

6], which proposes systemic thinking, anticipation, values, and action, areas that can also be worked on in ECE. Education is understood as a continuous and comprehensive process in which learning develops transversally throughout life. This learning does not only involve the acquisition of knowledge at an intellectual level, but also encompasses hands-on training, the ability to relate to others, and overall personal growth. As the Delors report argues, these aspects can be outlined in four fundamental pillars: learning to know (cognitive dimension), learning to do (instrumental dimension), learning to live together (social dimension), and learning to be (individual dimension) (Delors, 1996) [

43]. These pillars are meant to guide education systems in preparing individuals for the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, emphasising a holistic approach to learning.

Despite the existence of these conceptual frameworks, the literature points to a lack of practical and validated instruments for assessing eco-social competences (UNESCO, 2022) [

9]. The proposal of this study hence responds to this need, providing a rigorous and suitable tool for measuring the development of eco-social competences in real classroom contexts, promoting meaningful learning, community engagement, and shaping critical citizens committed to sustainability.

All the references included in the theoretical framework provide a solid basis for the design of rubric of eco-social competences for ECE, justifying the need to assess not only knowledge, but also values, attitudes, and skills related to care, critical reflection, participation, and responsibility.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

The main objective of this study is to design and validate an assessment tool of eco-social competences for children in ECE, based on the CARE–KNOW–DO pedagogical model (Okada & Gray, 2023) [

5], aligned with international guidelines for EfS (UNESCO, 2017 [

18]; Rieckmann, 2018 [

19]).

The competences assessed (critical thinking, social responsibility/ethical sense, diversity/interculturality) were selected because of their importance in eco-social education, and because they are in line with UNESCO’s key competences (see

Table 1).

The link with the competences defined by UNESCO enables identifying fundamental transversal skills for eco-social education. The CARE–KNOW–DO model allows for a holistic assessment that integrates the cognitive (knowledge), affective (values), and pragmatic (action) dimensions, which is particularly suitable for the early childhood stage (Okada et al., 2023) [

5].

3.2. Assessment Tool Design

The tool is structured in accordance with the three dimensions of the CARE-KNOW-DO model. In this study, the order is changed to KNOW-CARE-DO to fit the logic of progressive assessment:

KNOW (cognitive dimension): measures knowledge of natural systems and sustainability challenges, and involves thinking systemically, making connections and anticipating consequences (OECD, 2018 [

16]; CRUE, 2012 [

22]) (e.g., identifying causes of climate change).

CARE (affective dimension): assesses values and attitudes such as empathy, responsibility, and respect for diversity (e.g., taking care of the plants in the classroom).

DO (pragmatic dimension): focuses on the specific skills children can use and the activities they can carry out to contribute to a fairer and more sustainable environment, such as collaboration, problem-solving, and adopting responsible habits (Bianchi et al., 2022 [

6]; Okada & Gray, 2023 [

5]). It includes specific actions such as recycling, collaborating in school gardens, or participating in assemblies (e.g., reusing materials in class).

The rubric contains nine items distributed across three competences (

Table 2) that are assessed using a three-point Likert scale including the following levels: 1: novice, 2: developing, 3: proficient. It also includes visual elements (emojis) to facilitate children’s understanding. Each item integrates the three dimensions (cognitive, affective, and behavioural), which enables analysing how knowledge influences emotion and behaviour.

This structure facilitates progressive reading of competence development, starting with knowledge (KNOW), moving on to emotional engagement (CARE), and finally arriving at action (DO).

The instrument was designed to be used in different stages of education and school contexts, with special emphasis on the 5–6 age group. It facilitates both qualitative and quantitative assessment, providing relevant data for research and educational improvement.

3.3. Initial Validation Procedure and Data Collection

The validation process of the rubric originally took place in Spanish, as it was the language the participating children and teachers used. The version used for validation was in Spanish, ensuring the participants’ understanding and linguistic and cultural adaptation of the content. This decision is in agreement with recommendations on the adaptation and validation of instruments, which emphasise the need to adapt the instrument to the language and culture of the target population before translating or adapting it to other languages (Cruchinho et al., 2024) [

44]. The translation of the rubric into English was done in accordance with criteria of conceptual and cultural correspondence. The English version was checked by bilingual experts to ensure fidelity to the original, and to make sure future international users will understand it (Katthab, 2024) [

45].

The procedure to ensure the validity and reliability of the rubric for eco-social competences in ECE was rigorous and participatory. It was organised into the following phases:

1. Expert validation

A total of ten teachers and specialists in ECE assessed the clarity and relevance of the items included in the rubric. The teachers’ contributions enabled simplifying the language, improving the wording of the items, incorporating visual elements, and reducing the Likert scale from five to three options to facilitate the children’s understanding.

2. Respondent validation

Comprehension tests were carried out with ten 5-year-old children, prioritising the use of simple language and contextualised examples. This phase ensured the items were user-friendly and meaningful to ECE learners.

3. Pilot test

The final rubric was used with a sample of 150 children aged 5–6 (73 boys (48.7%), 60 girls (40%), and 17 (11.3%) without gender information) from six schools in Barcelona, Spain. The data were collected between February and March 2025.

A response scale including three options represented by emojis (😞=1, 😐=2, 😊=3) was used. This kind of self-assessment system is commonly used with children this age. The possible answers to each item were: “No”, “I do not know,” and “Yes.” This system allowed for simple coding and accurate quantitative analysis of the responses. Internal consistency of the items was checked, and the statements were simplified to avoid ambiguities, thus ensuring the reliability and adaptation of the rubric to the real context of ECE. Once the data were collected and coded, statistical analysis of the sample was carried out, as described in the section below.

4. Results

The main results, based on the use of the rubric validated to the sample of 150 children, are presented below:

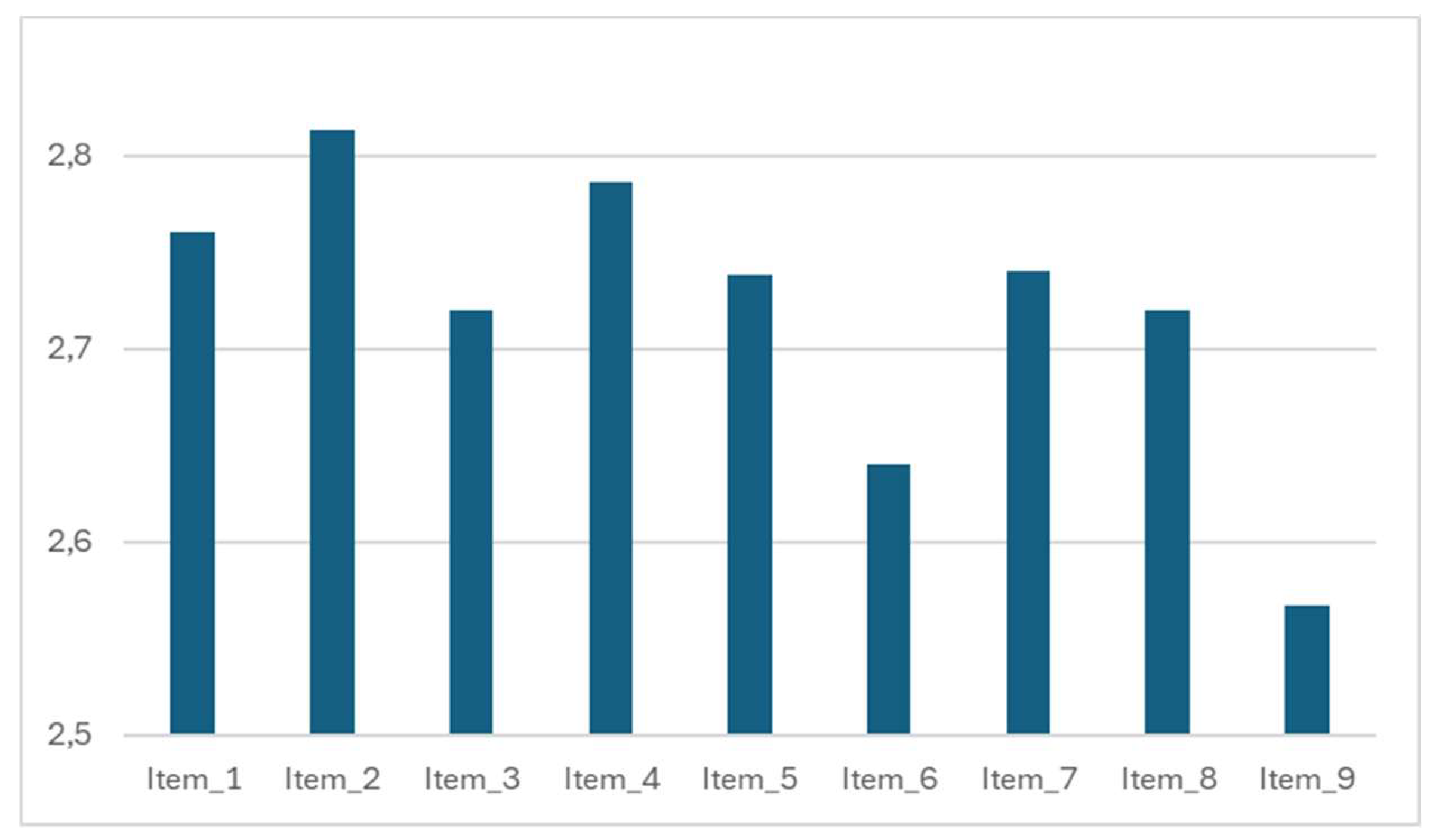

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each of the nine items to provide an overview of the responses. The mean scores for each item ranged from 2.57 to 2.81, suggesting a general trend towards positive responses, with children showing a relatively high level of eco-social competence. The standard deviations ranged from 0.37 to 0.69, indicating a moderate level of variability in the responses, which is typical in early childhood assessments where individual perceptions and understanding can vary widely.

Figure 1 shows the children’s scores in each item.

An independent sample t-test was used to examine potential differences between boys and girls in their responses. The results showed no statistically significant differences between boys and girls for any of the items. Gender did not significantly affect the level of eco-social competences.

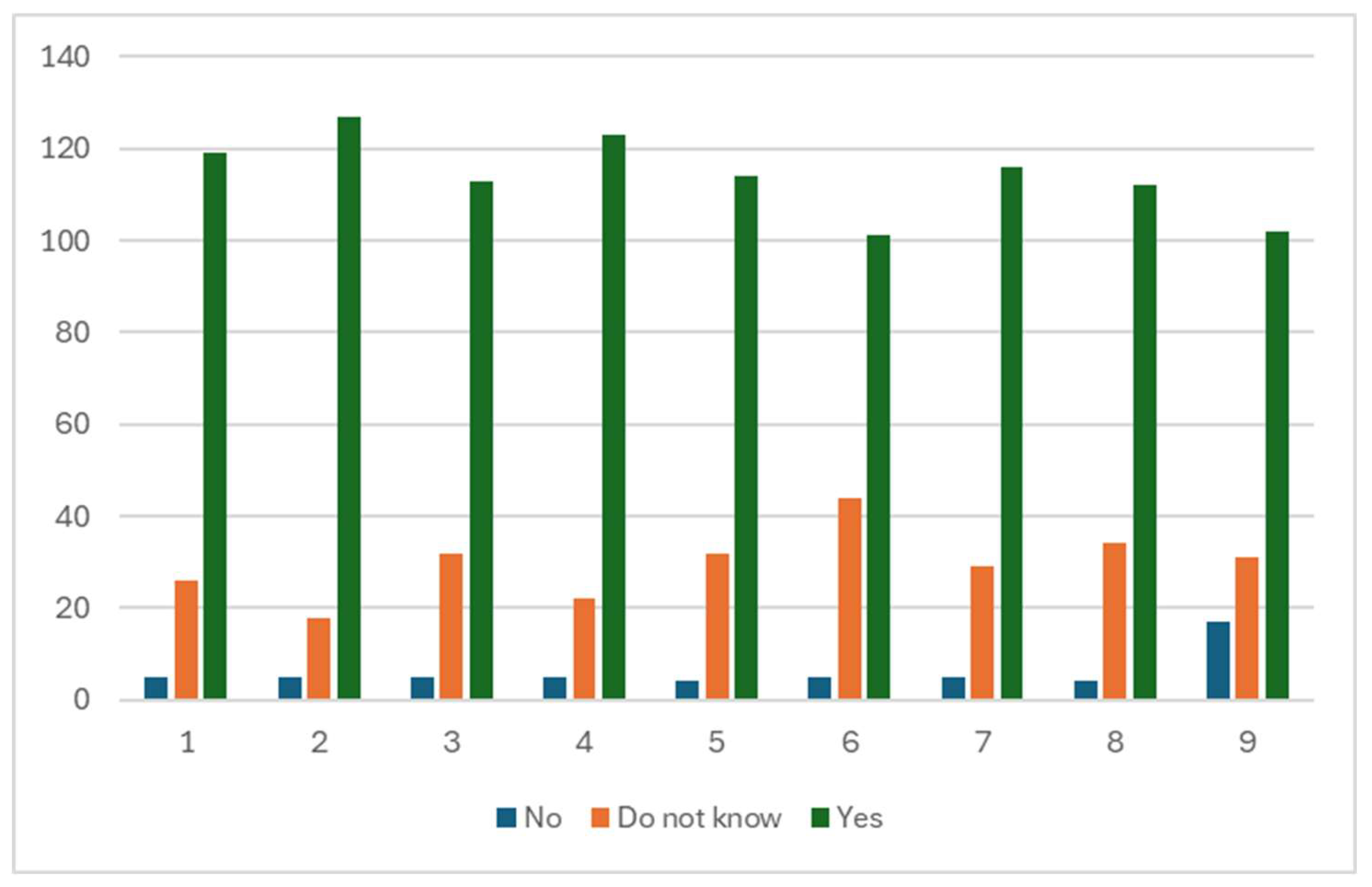

Figure 2 shows the frequency histogram for the nine items. In all of them, “yes” is overwhelmingly dominant, indicating a favourable viewpoint in all cases. The second item received the highest number of “yes” responses (127), and the last one the lowest (102). It is worthy of note that the children have a highly positive self-perception regarding eco-social competences.

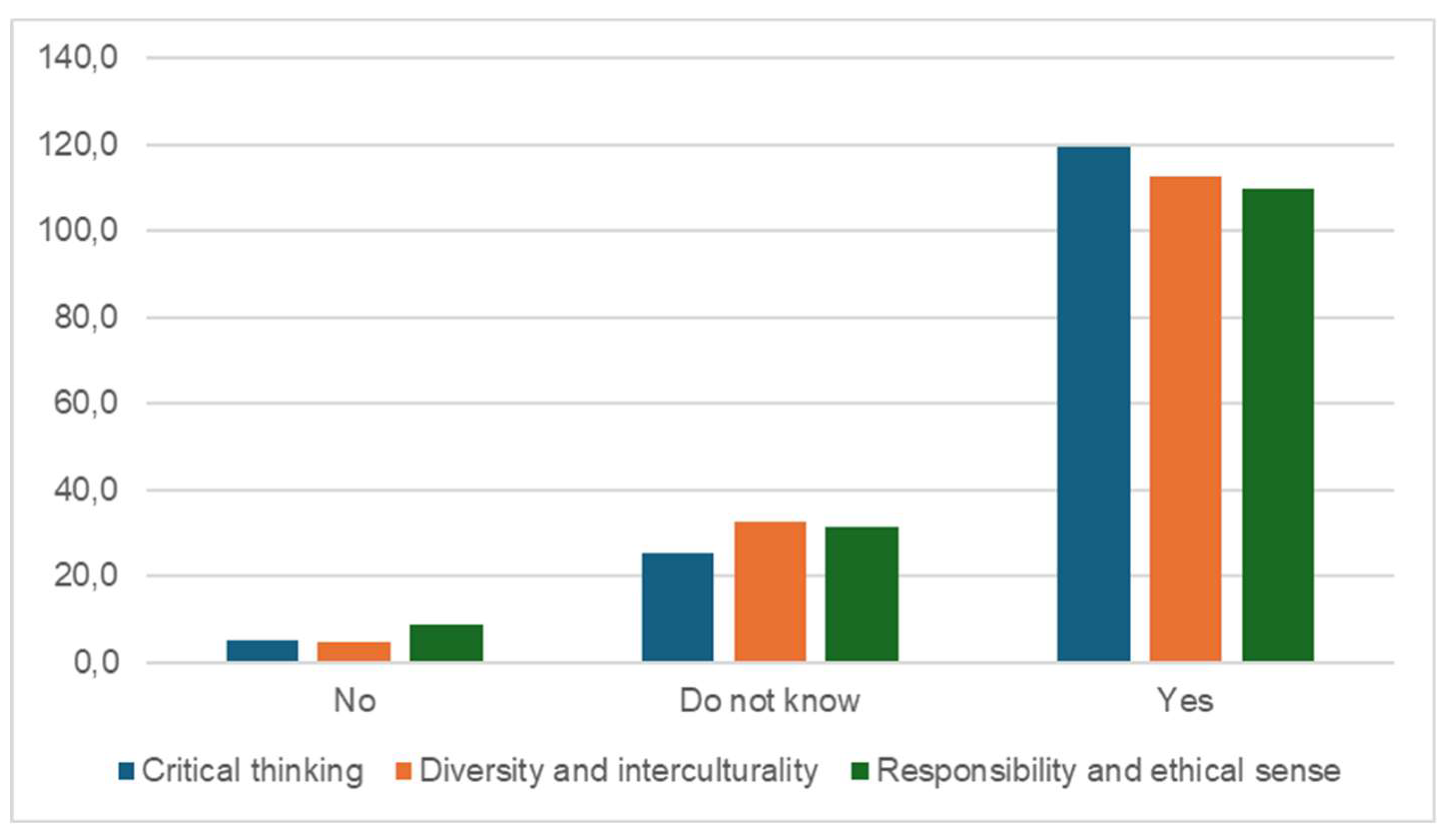

Figure 3 shows a different perspective of the data. Each of the three competences (critical thinking, diversity and interculturality, and responsibility and ethical sense) consists of three items, one for the cognitive dimension, another for the affective dimension, and yet another for the behavioural dimension.

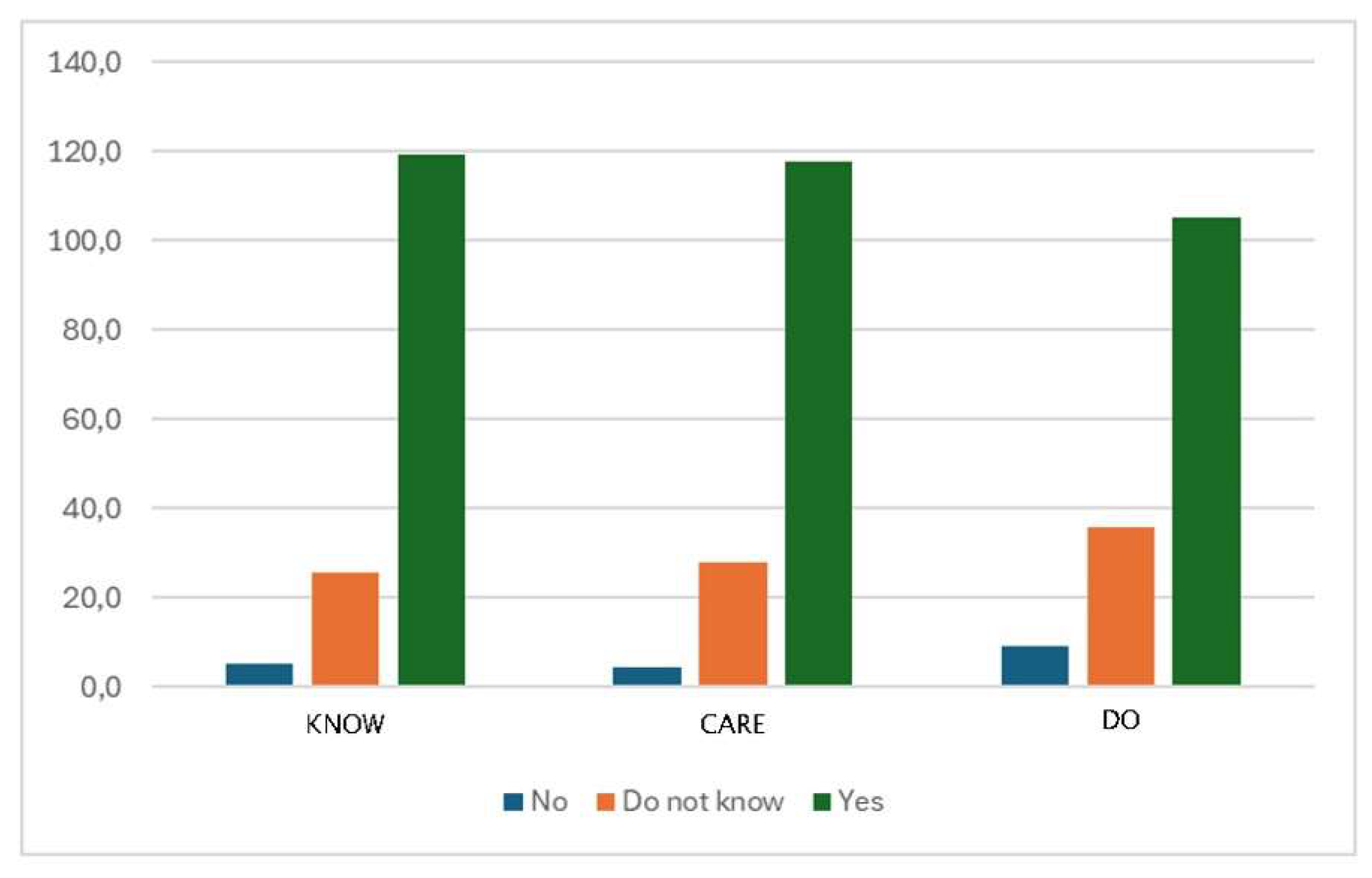

Figure 4 shows the scores obtained in the different items grouped per dimension. The cognitive dimension, which represents the level of knowledge (KNOW) contains items 1, 4, and 7. The affective dimension, which symbolises the emotional level (CARE) includes items 2, 5, and 8. The behavioural dimension, which measures the behaviour (DO) of the participating children, comprises items 3, 6, and 9.

The level measuring knowledge (KNOW) is the highest, while the level measuring behaviour (DO) is the lowest. This result is consistent with the theoretical framework used, which postulates that once a certain level of knowledge is acquired, emotional engagement follows, and this, in turn, leads to a commitment shown in behaviour.

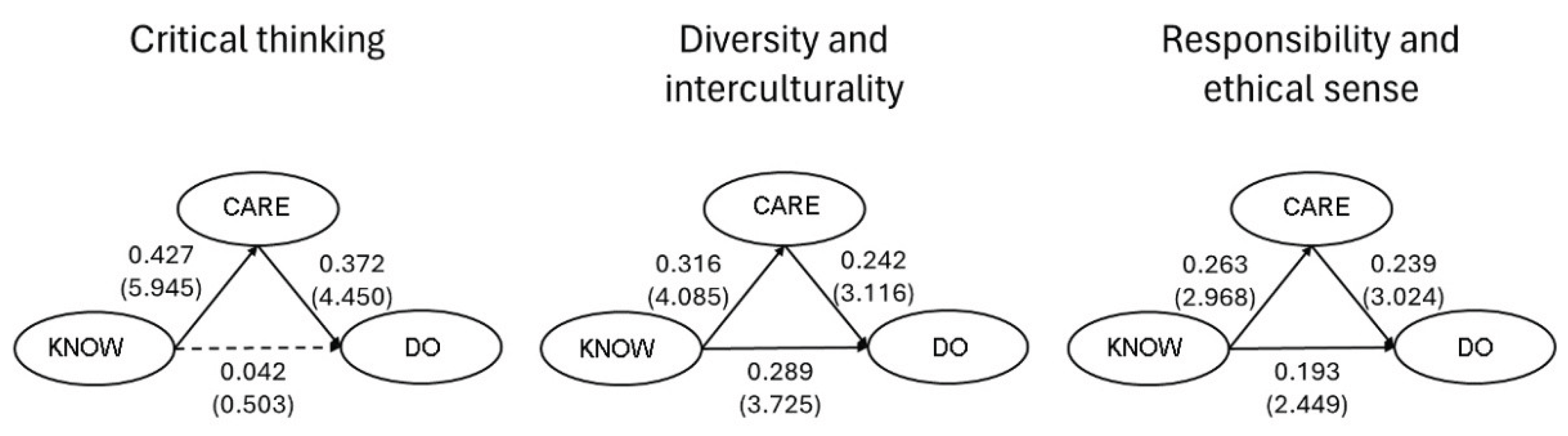

To conclude this study, three “path analyses”, one for each competence, were used to examine how the progressive conceptual flow, starting with the knowledge acquisition level, impacts the emotional engagement level, and finally leads to effective ethical behaviour.

The analyses were carried out using SmartPLS, a software that offers covariance-based structural equation modelling.

Figure 5 shows the three path analyses performed. The standardised coefficients are displayed on the arrows, and the associated t-values in parentheses. It is observed that all of them are significant at the 0.05 significance level (all t-values are greater than 1.96), except for the coefficient in “critical thinking” between KNOW and CARE.

It is worth highlighting that in the first competence, “critical thinking”, transforming knowledge into behaviour is only possible through what children feel when they understand how certain actions impact the planet and people. It is important for children to empathise with people and the planet for their knowledge to be transformed into action. In other words, the mediating effect of item 2 (I get sad…) in the rubric is essential to know the impact of the first item (I know…) on the third one (I take care of…). When analysing the second competence, “diversity and interculturality,” it is observed that the cognitive dimension directly impacts the behavioural dimension. The mediation effect of item 5 (I feel sad…), is low. Here, empathy is not that important. The same occurs in the third competence, “responsibility and ethical sense.”

5. Discussion

The results obtained from using the rubric for eco-social competences with children in ECE provide relevant empirical evidence of the development of these competences in early childhood. They enable reflecting on the validity and usefulness of the instrument designed.

It is worthy of note that the participating children had a positive self-perception of their eco-social competences, and obtained high average scores in all the items. There is a clear predominance of affirmative answers (“yes”) in all three dimensions. This pattern may reflect the children properly internalised the values worked on at school and the tendency to give socially desirable responses, which is typical of this age group (Okada & Gray, 2023) [

5]. However, the variability observed shows the instrument is sensitive to individual differences, and captures nuances in competence development, which is fundamental for formative assessment (UNESCO, 2017) [

18].

The absence of significant differences between boys and girls is worth mentioning. It suggests that, at least in this sample and context, the development of eco-social competences is not conditioned by gender. This finding reinforces the idea that promoting these competences can be transversal and inclusive, regardless of the personal characteristics of the students. This is in line with the principles of equity and inclusion set out by UNESCO (2018) [

10].

The analysis by dimensions shows a clear hierarchy in the results: the level of knowledge (KNOW) obtains the highest scores, followed by the emotional level (CARE), while the behaviour level (DO) gets the lowest scores. This trend confirms what the CARE-KNOW-DO model (Okada & Gray, 2023 [

5]; Okada et al., 2025 [

41]) emphasises. It also corroborates what the literature on education for sustainability stresses: knowledge is a necessary but insufficient condition for the transformation of values and habits. In this context, emotional engagement acts as a key mediator in turning knowledge into action (Okada, 2024 [

42]; UNESCO, 2022 [

9]).

The holistic development of individuals, including emotional and social aspects, is key for quality education. This has already been pointed out by Delors (1996) [

43], who stresses the importance of the “learning to be” and “learning to live together” pillars for integral education. The emotional dimension is hence crucial to cognitive development, and its integration into educational processes is essential to promote sustainable values and behaviour, and an active commitment to society.

The results of the pilot test show that, although children have considerable knowledge of sustainable actions, this knowledge does not always turn into specific behaviour if there is no emotional component acting as a bridge. It is thus empirically confirmed that empathy towards people and the planet is key to transforming knowledge into action (DOGC, 2023 [

3]; Okada, 2024 [

42]). This is particularly relevant in early childhood, when learning is built on emotional and life experiences (UNESCO, 2023) [

15]. The data highlight the importance of the affective dimension, and the results confirm that affection and emotional engagement are decisive in transforming knowledge of sustainability into real behaviour and habits, as predicted by the CARE–KNOW–DO model (Okada, 2024 [

42]; UNESCO, 2022 [

9]). This finding reinforces the need to incorporate activities and methodologies that promote emotional experience and reflection into early childhood classrooms.

The results of the path analyses reinforce this idea, especially in the critical thinking competence, in which it is observed that knowledge only turns into responsible behaviour through emotional experience (CARE). This finding is in line with Rieckmann’s (2018) [

19]. argument that critical and systemic thinking, when combined with empathy and social responsibility, facilitate the development of active global citizenship committed to sustainability. In contrast, in the competences of diversity and interculturality, and responsibility and ethical sense, knowledge has a more direct impact on action, and emotional mediation is less decisive, which may be related to the more normative and socially consensual nature of these competences (Bianchi et al., 2022) [

6].

These results have important pedagogical implications. On the one hand, they highlight the need to design educational proposals that not only convey knowledge, but also encourage socio-emotional reflection and empathy, especially with regard to the impact of one’s own actions on people and the planet (UNESCO, 2017 [

18]; Okada, 2024 [

42]). On the other hand, they underline the usefulness of multidimensional assessment, like the assessment in the rubric developed, to identify at which point each child is in the process, and to be able to personalise educational interventions, as recommended by UNESCO (2022) [

9] for transformative education.

The rubric designed has proven to be a reliable, understandable, and age-appropriate tool for the formative and observational assessment of eco-social competences. Its structure facilitates cross-curricular assessment, and can be used by both teachers and researchers. It responds to the lack of practical tools observed in the literature (UNESCO, 2020 [

8]; 2022 [

9]).

Finally, the methodological robustness of the instrument, validated by experts and children, and its applicability in real classroom contexts are worthy of note. However, some limitations, such as the possible influence of social desirability in the responses, concentrating the sample in a specific geographical area, and the need for future validations in other contexts and education levels must be acknowledged. Nevertheless, the study provides a rigorous transferable tool for assessing and promoting eco-social competences in ECE, thus contributing to the objectives of the 2030 Agenda and to transformative EfS (UNESCO, 2018 [

10]; Okada et al., 2025 [

41]).

Another limitation of the study is that the rubric was originally validated in Spanish. Although the translation into English was checked by bilingual experts, in accordance with Cruchinho et al. (2024) [

44], to ensure its conceptual and cultural equivalence, future research should validate the English version in English-speaking contexts to make sure it can be used and understood in different linguistic environments. In the future, it would be relevant to expand the sample to other territories and education levels, and to use the rubric in international contexts. As part of the pedagogical documentation, the rubric could investigate the impact of family and community involvement in the development of eco-social competences. A longitudinal follow-up is also recommended to analyse the development of these competences throughout different education levels.

6. Conclusions

The design and initial validation of a multidimensional instrument for assessing eco-social competences in ECE contribute substantially to EfS. The study shows that children aged 5–6 already possess a considerable level of knowledge about sustainable actions and social responsibility. However, the results show that emotional engagement is key to transforming this knowledge into specific behaviours, thus confirming the premises of the CARE–KNOW–DO model [

5], and the importance of integrating cognitive, affective, and behavioural dimensions into educational assessment.

The rubric developed, based on international frameworks such as the 2030 Agenda [

1], GreenComp and PISA 2018 [

6,

16], offers a reliable and age-appropriate method for teachers to assess eco-social competences in real early childhood classroom contexts. Its structure, including cognitive, affective, and behavioural dimensions, facilitates formative and observational assessment, and contributes to the development of transformative learning practices from the earliest stages of education onwards.

Despite the limitations described earlier, the validated instrument is a rigorous and transferable tool for assessing eco-social competences in ECE. Future studies should consider larger samples and validation in other linguistic contexts to increase the generalisability of the results.

The results show the need for the design of educational proposals that not only convey knowledge, but also encourage emotional reflection and empathy, especially with regard to the impact of one’s own actions on people and the planet. The rubric developed in this study responds to the urgent need for practical and valid assessment tools in education, as identified in international reports. It contributes to the implementation of the SDGs through critical, participatory, and values-based education.

This study provides a valuable tool for assessing and promoting eco-social competences in ECE, contributing to the goals outlined in the 2030 Agenda, and fostering transformative learning practices that empower children to become critical, responsible, and committed citizens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MTFC, FM. and SAT.; methodology, MTFC, FM. and SAT software, FM.; validation, MTFC and SAT.; formal analysis, FM.; investigation, MTFC, FM. and SAT; resources, MTFC and SAT.; data curation, FM.; writing—original draft preparation, MTFC and SAT; writing—review and editing, MTFC, FM. and SAT.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, MTFC and SAT.; project administration, SAT and MTFC.; funding acquisition, SAT.

Funding

This research was funded by Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR), Duration: from January 29, 2024 to January 29, 2026; PI: Sílvia Albareda Tiana (UIC); Financial support: 117,246.06 €; Reference: 00081 CLIMA 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ann Swinnen for her comments and suggestions, and we also appreciate the support of the Integral Research Group on Sustainability and Education (SEI) of the International University of Catalonia (2017 SGR 119), and especially the teachers of the schools that have collaborated in the project: Collserola School (Sant Cugat del Vallès), Garbí-Pere Vergés School (Esplugues de Llobregat); La Farga Infantil School (Valldoreix) and Pau Casals School (Vacarisses), and the people of the centers that have coordinated it: Ariadna Bonet, Sergi Sans, Marga Marcas and Ariadna Chornet.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Bennett, J. La democràcia i l’autonomia comencen d’hora. Panoràmica del currículum i l’avaluació per als infants per sota de l’edat d’escolarització obligatòria. Infància a Europa 2005, 4-6. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/ejemplar/257834.

- Decret 21/2023 [Generalitat de Catalunya]. Pel qual s’ordenen els ensenyaments de l’educació infantil. 7 de febrer de 2023. https://dogc.gencat.cat/ca/document-del-dogc/?documentId=951431.

- Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional (2018). PISA 2018: Competencia Global. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/inee/evaluaciones-internacionales/pisa/pisa-2018.html.

- Okada, A., & Gray, P. A climate change and sustainability education movement: Networks, open schooling, and the ‘CARE-KNOW-DO’ framework. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, G., Pisiotis, U., & Cabrera Giraldez, M. (2022). GreenComp: The European sustainability competence framework. Bacigalupo, M., Punie, Y. (Eds.). Publications Office of the European Union. [CrossRef]

- Leitch, A., Heiss, J. & Byun, W.J. (Eds) Issues and trends in education for sustainable development (vol.5). UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261445.

- UNESCO. Educación para el desarrollo sostenible. Hoja de ruta; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 1-67. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374896.

- UNESCO. El profesorado opina: motivación, habilidades y oportunidades para enseñar la educación para el desarrollo sostenible y la ciudadanía mundial. UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022; pp. 1-60. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381225.

- UNESCO.Education for Sustainable Development Goals. Learning Objectives. UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Decret 175/2022 [Generalitat de Catalunya]. Pel qual s’ordenen els ensenyaments de l’educació bàsica. 27 de setembre de 2022. https://portaljuridic.gencat.cat/ca/document-del-pjur/?documentId=938401.

- Güler Yıldız, T., Öztürk, N., İlhan İyi, T., Aşkar, N., Banko Bal, Ç., Karabekmez, S., & Höl, Ş. Education for sustainability in early childhood education: A systematic review. Environmental Education Research 2021, 27, pp. 796-820. [CrossRef]

- Foschi, R. (2020). Maria Montessori. Ediciones Octaedro.

- Piaget, J. La teoría de Piaget. Infancia y aprendizaje, 1981, 4 (sup2), pp. 13-54. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Early childhood care and education. UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023. https://www.unesco.org/en/early-childhood-education.

- OECD (2018). Preparing our youth for an inclusive and sustainable world: The OECD PISA global competence framework. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/topics/policy-sub-issues/global-competence/Handbook-PISA-2018-Global-Competence.pdf.

- Real Decreto 95/2022, de 1 de febrero [Ministerio de Educación y formación Profesional]. Por el que se establece la ordenación y las enseñanzas mínimas de la Educación Infantil 2 de febrero de 2022. https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2022-1654.

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals. Learning Objectives. UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 1-62. [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Key themes in education for sustainable development. In Issues and trends in education for sustainable development; Leicht, A., Heiss, J., Byun, W.J., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018, pp. 61-84. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261445.

- UNESCO; UNICEF. The right to a strong foundation. Global Report on Early Chilhood Care and Education. UNESCO: Paris, France, 2024; pp. 1-159. [CrossRef]

- Albareda-Tiana, S., Ruíz-Morales, J., Azcárate, P.; Valderrama-Hernández, R., Múñoz, J-M. The EDINSOST Project: Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals at University level. In Universities as Living Labs for Sustainable Development: Supporting the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W.; Salvia, A. L.; Pretorius, R.; Brandli, L.; Manolas, E.; Alves, M. F. P.; Azeiteiro, U.; Rogers, J.; Shiel, C.; do Paco, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 93-210.

- Executive Committee of the Working Group for Environmental Quality and Sustainable Development of the CRUE; CADEP (2012). Guidelines for the inclusion of Sustainability in the Curriculum. https://www.crue.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Directrices_Ingles_Sostenibilidad_Crue2012.pdf.

- AITSL. Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. AITSL, 2022.

- Sleurs, W. (Ed). (2008). Competencies for ESD (Education for Sustainable Development) teachers. A framework to integrate ESD in the curriculum of teacher training institutes. University Educators for Sustainable Development. https://ue4sd.glos.ac.uk/downloads/CSCT_Handbook_11_01_08.pdf.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (2013). Empowering educators for a sustainable future. Tools for policy and practice workshops on competences in education for sustainable development. https://unece.org/environment-policy/publications/empowering-educators.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Creech, H. (2016). Ten years of the UNECE Strategy for Education for Sustainable Development. United Nations. https://unece.org/environment-policy/publications/10-years-unece-strategy-education-sustainable-development.

- UNESCO (2005). Draft International implementation scheme for the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005-2014). http://earthcharter.org/virtual-library2/draft-international-implementation-scheme-for-the-united-nations-decade-of-education-for-sustainable-development-2005-2014/.

- UNESCO (2014). Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/ 002305/230514e.pdf.

- UNESCO (2016). Planet: Education for Environmental Sustainability and Green Growth. Global Education Monitoring Report. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002464/246429e.pdf.

- Barth, M., Godemann, J., Rieckmann, M. and Stoltenberg, U. Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 2007, 8, pp. 416-430.

- Wiek, A., Withycombe, L. & Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: a reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science, 2011, 6, pp. 203-218. [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Future-oriented higher education: Which key competencies should be fostered through university teaching and learning?. Futures, 2012, 44, pp. 127-135. [CrossRef]

- Boix Mansilla V., & Duraising, E. D. Targeted assessment of students’ interdisciplinary work: An empirically grounded framework proposed. The Journal of Higher Education, 2007, 78, pp. 215-237. [CrossRef]

- Boix Mansilla, V., Jackson, A. Educating for global competence: Learning redefined for an interconnected world. In Mastering Global Literacy (Contemporary Perspectives on Literacy), Jacobs, H., Ed.; Solution Tree Press: Indiana, USA. 2013.

- Boix Mansilla V., & Jackson, A. W. (2022). Educating for global competence: Preparing our students to engage the world. Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development: Virginia, USA, 2022.

- Deardoff, D.K. The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence.; SAGE: California, USA; 2009.

- UNESCO. Global Citizenship Education. Topic and Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015; pp. 1-74. [CrossRef]

- Herrero, Y. La educación del compromiso ecosocial en la infancia, la adolescencia y la juventud. A Ciudadanía Global. Una visión plural y transformadora de la sociedad y de la escuela; Díaz-Salazar, R., Coord.; Fundación SM: Madrid, España, 2020; Volumen 1, pp. 145-153.

- Agundez, A. Aportes de la filosofía para niños y niñas a la educación ecosocial. Childhood & philosophy, 2023, 19, pp. 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Bastida, J.M. De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de educación ecosocial. Revista de Educación Ambiental y Sostenibilidad, 2024, 6, pp. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Okada, A., Sherborne, T., Panselinas, G., & Kolionis, G. Fostering transversal skills through open schooling supported by the CARE-KNOW-DO pedagogical model and the UNESCO AI competencies framework. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 2025, pp. 1-46. [CrossRef]

- Okada, A. A self-reported instrument to measure and foster students’ science connection to life with the CARE-KNOW-DO model and open schooling for sustainability. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2024, 61, pp. 2362-2404. [CrossRef]

- Delors, J. (1996). La Educación encierra un tesoro, informe a la UNESCO de la Comisión Internacional sobre la Educación para el Siglo XXI. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000109590_spa.

- Crucinho, P., López-Franco, M. D., Capelas, M. L., Almeida, S., Bennett, P. M., Miranda da Silva, M., Teixeira, G., Nunes, E., Lucas, P., Gaspar, F. & Handovers4SafeCare. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of measurement instruments: a practical guideline for novice researchers. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 2024, 31, pp. 2701-2728. [CrossRef]

- Writeliff. The Difference Between Linguistic Validation and Cognitive Debriefing Avaliable online: https://writeliff.com/blog/the-difference-between-linguistic-validation-and-cognitive-debriefing/ (accessed on 12 October, 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

, affective

, affective  , and behavioural

, and behavioural  dimension

dimension