1. Introduction

Sustainable development education is increasingly a priority to face the challenges of this century: biodiversity loss, urbanization, and climate evolution. Schools can be important in preparing the future generation to have knowledge, skills and value that encourage pro-environmental practices which are in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) especially SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and SDG 15 (Life on Land). It is in this frame that education based on the environment has come to be considered less and less as a transfer mechanism of eco-factual knowledge (as prescribed by modern science itself) and more and more a process through which values, dispositions, rootedness in place are acquired - to sustain commitment over time.

Ecosystem services (ES) as a framing for environmental education One of the most promising educational perspectives relating to ES has been set into an eco-systemic approach. The concept of ecosystem services offers an approach for making ecological processes relevant to human welfare in a manner that is tangible and accessible. Providing and supporting services are easier to show in a classroom; cultural ES however, such as beauty, place attachment and recreational opportunities tend to be far more difficult to convey yet are key in motivating and creating the link for individuals’ association with ecosystems which dictates value. Education is a promising setting for integrating the idea of ES, as it could unite intellectual and emotional domains of learning and make simultaneously issues both intelligible in terms of concepts or pathways between human experience and ecosystems.

Conventional school teaching, which is based upon classroom lectures, transfers knowledge and information in a structured manner and, to some extent does not cater for experiences or provides little consideration for the affect. Outdoor experiential education, especially when integrated with gamified or narrative elements, has also been found to provoke curiosity and nurture a deeper connection to local environment in students and develop an enhanced ability to understand non-physical ecosystem service. Theories of place-based education and models of experiential learning (e.g., the learning cycle) further suggest that direct experience in local, semi-naturalised urban ecologies can promote ecological literacy, identity with place, and stewardship.

Although there is an increasing literature on environmental education, empirical evidence comparing the effectiveness of in-classroom and experiential field approaches with regard to ecosystem services continues to be scarce. Furthermore, we know comparably little about the effectiveness of these interventions on different subgroups of learners (based on demographic characteristics such as gender or academic achievement or past experience with nature). Challenging these gaps is especially relevant in urban areas where semi-natural green spaces are threatened with development, yet have the potential to act as ―living laboratories‖ for sustainability education.

This gap is what we aimed to fill, by comparing the efficiency of two types of instruction—classroom lectures and outdoor game-based workshops—in enhancing students’ perception of ES in a semi-natural urban area (Górki Czechowskie in Lublin, Poland). One of the main objectives of this study is to examine (1) if outdoor workshops are more effective than lectures in increasing environmental awareness and intangible values related to ecosystems; 2) how student characteristics, including gender, academic performance, home environment and frequency of visits to natural areas affect learning outcome; and (3) whether different student profiles can be distinguished that could potentially assist sustainability education by tailoring approaches according the students’ individual needs.

2. Literature Review

The ecosystem services (ES) concept has been adopted increasingly as a vehicle for connecting ecological relationships with human benefits [

1,

2]. Under this perspective, ecosystems offer more than material goods and regulating processes: they also provide cultural services that shape human identity, sense of place and psychological well-being [

3]. Though the concepts of provisioning and regulating services can be easily explained in formal curriculum, cultural ecosystem services, which can include recreational, aesthetic and spiritual values, are more difficult to apply operationally particularly within the confines of traditional classroom based teaching [

4]. New research also draws attention to the fact that touching on these intangible services is important for inducing pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors, having made them an underrepresented dimension in environmental education [

5].

There have been profound changes in the field of environmental education over the last few dec-ades. Earlier initiatives stressed the transfer of ecology and environmental knowledge with a concentration on conservation themes and natural sciences [

6]. Recent views, such as education for sustainable development (ESD), also stress not only auditory knowledge and understanding, but also values, attitudes and action [

7]. Under this paradigm, education is viewed as transformative and enables learners to critically reflect on human–nature relationships, and take action towards sustainability. Teaching interventions are therefore now more widely judged not only in terms of knowledge gained, but also by affective and behavioural outcomes [

8].

An approach that has been growing popular is experiential and place-based education. Kolb’s [

9] experiential learning theory posits that learning is most effective when it occurs through the stages of concrete experience, reflection, conceptualization, and application. Spot-based education, in contrast, focuses on local landscapes as settings for learning that link students to their places [

10]. Research indicates that learning in the outdoor environment contributes to ecological literacy, health and place belonging [

11,

12]. It has also been evidenced that gamified and narrative based activities in outdoor education enhance engagement and retention especially among younger audience [

13].

Inclusion of services in education remains a burgeoning field. Some studies have explored ES as a pedagogical device to convey the multiple services that ecosystems provide. For instance, López-Rodríguez et al. [

14] provided evidence that the ES participatory mapping activities helped students understand more about the multifunctionality of landscapes. Similarly, Casado-Arzuaga et al. [

15] also noted that having students evaluate cultural services has been successful as a means to encourage stewardship. Yet research in this area is still limited and largely concentrated on higher education, leaving a significant evidence gap as to whether ES centred approaches are effective in primary and secondary schools.

Second, the city is a challenging and at the same time inspiring environment. On the other hand, urban children may also have fewer chances to experience semi-natural ecosystems first-hand and thus be subject to what has been named as the “extinction of experience” [

16]. Urban green areas, on the other hand, from semi-natural areas like fallow land or secondary forests provide easily accessible laboratories for biodiversity education and learning the role of ecological processes as well as cultural values of ecosystems [

17]. Applied elements like these could be used in education programs as a trigger to reconnect urban youth with nature [

18].

However, despite mounting enthusiasm with respect to outdoor learning and ES-informed education, comparative research comparing classroom- vs outdoor experiential-based approaches has been limited. The majority of existing studies only explore the advantages of outdoor learning in general, or report individual system service assessment cases but do not investigate its holistic effect on students’ knowledge and value recognition. Moreover, the variance of learner traits (e.g., gender, sex performance or previous contact with nature) has not been taken into account thoroughly enough to examine the results. However studies indicate that such variables could strongly moderate educational effectiveness [

19,

20].

In conclusion, the literature demonstrates the following:

1. There are few empirical evidences of how ecosystem services, specially cultural, have been included in education at primary and secondary levels.

2. Little research Challenge conventional classroom presentations with outdoor experiential workshops in affecting cognitive and affective learning.

3. Lack of focus on the heterogeneity of learners and factors related to social-demographic, academic profiles that would determine the efficacy of educational interventions.

Filling these gaps necessitates research that, besides quantifying students’ gains in knowledge, considers how such awareness of immeasurable ecosystem services affects feelings of place-based attachment and use of local green spaces. This article further fills these gaps by measuring the effects of both lecture-based and outdoor experiential formats on adolescents’ awareness of ecosystem services in an urban semi-natural context.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

The study was conducted in Górki Czechowskie, a semi-natural green area located in the northern part of Lublin, Poland. The site consists of former military training grounds that have naturally regenerated, resulting in a mosaic of grasslands, shrubs, and patches of woodland. It is one of the most biodiverse urban areas in Lublin, hosting numerous plant and animal species, and is increasingly recognized for its recreational and educational potential. At the same time, the area faces ongoing development pressures, which makes it a relevant context for exploring how educational interventions can strengthen public appreciation of its ecological and cultural values.

3.2. Participants

The study involved 150 students aged 13–14 years (6th and 7th grades) from two primary schools in Lublin. The participants were divided into two groups:

Lecture group (n = 93): attended a 45-minute classroom lecture on ecosystem services.

Workshop group (n = 99): participated in the same lecture followed by a 90-minute outdoor workshop at Górki Czechowskie.

Demographic data were collected, including gender, average school grades, type of residence (apartment block vs. detached house), and frequency of visits to natural areas. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from both students and their parents/guardians. The study design was approved by the relevant educational authorities and complied with ethical standards for research involving minors.

3.3. Educational Intervention

Both groups received a standardized classroom lecture introducing the concept of ecosystem services, with examples of provisioning, regulating, and cultural services relevant to the local context.

The workshop group additionally took part in an outdoor educational game conducted at Górki Czechowskie. The workshop combined experiential learning and gamification elements:

Students worked in small teams to identify different types of ecosystem services in situ.

Tasks involved observation, problem-solving, and group discussion.

Narrative and role-play components were included to strengthen engagement and facilitate reflection on intangible values such as cultural identity, sense of place, and recreational opportunities.

This design aimed to compare purely cognitive knowledge transfer (lecture) with a mixed approach integrating cognitive, affective, and experiential dimensions (lecture + workshop).

3.4. Data Collection

A structured questionnaire survey was used as the main data collection tool. It included both closed-ended and open-ended questions (Q3–Q9), covering:

Q3 – Nature Walks: frequency of forest/water visits (0–3 scale),

Q4 – Home Environment: living context (1–3 scale),

Q5 – Site Awareness: familiarity with the local site (0/2),

Q6 – Urban Nature Familiarity: self-reported knowledge of urban green areas (0–3),

Q7 – Ecosystem Knowledge: factual understanding of ecological functions (0–2–4),

Q8 – Tangible Ecosystem Goods: number of material items listed (e.g., flowers, chestnuts),

Q9 – Intangible Ecosystem Values: number of symbolic or emotional items listed (e.g., wild animals, beauty).

The questionnaire was administered before and after the intervention to assess changes in students’ knowledge and awareness. In some cases, follow-up surveys were also conducted after several weeks to assess retention.

3.5. Data Analysis

Gain scores were computed as: Gain = Scoreafter − Scorebefore

Data were analyzed using a combination of descriptive and inferential statistics.

Paired-sample t-tests were applied to measure changes within groups before and after the intervention.

Independent-sample t-tests and one-way ANOVA were used to compare differences between the lecture and workshop groups.

Correlation analysis examined associations between variables such as frequency of nature visits, academic achievement, and learning outcomes.

Multiple regression analysis identified predictors of knowledge gains, including baseline knowledge, gender, school grades, and home environment.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis were applied to identify distinct learner profiles, which were categorized as Absorbers, Narrators, Eco-Masters, and Nature Lovers.

All statistical tests were conducted with a significance level of α = 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Overall Learning Outcomes

Both instructional formats led to improvements in students’ knowledge and awareness of ecosystem services. Paired-sample t-tests indicated significant gains across most questionnaire items (Q3–Q9) for both the lecture and workshop groups. However, the magnitude of improvement varied between groups, with outdoor workshops generally yielding higher increases in awareness.

Full descriptive statistics for pre- and post-test scores in both the lecture and workshop groups are provided in

Table A1 and

Table A2.

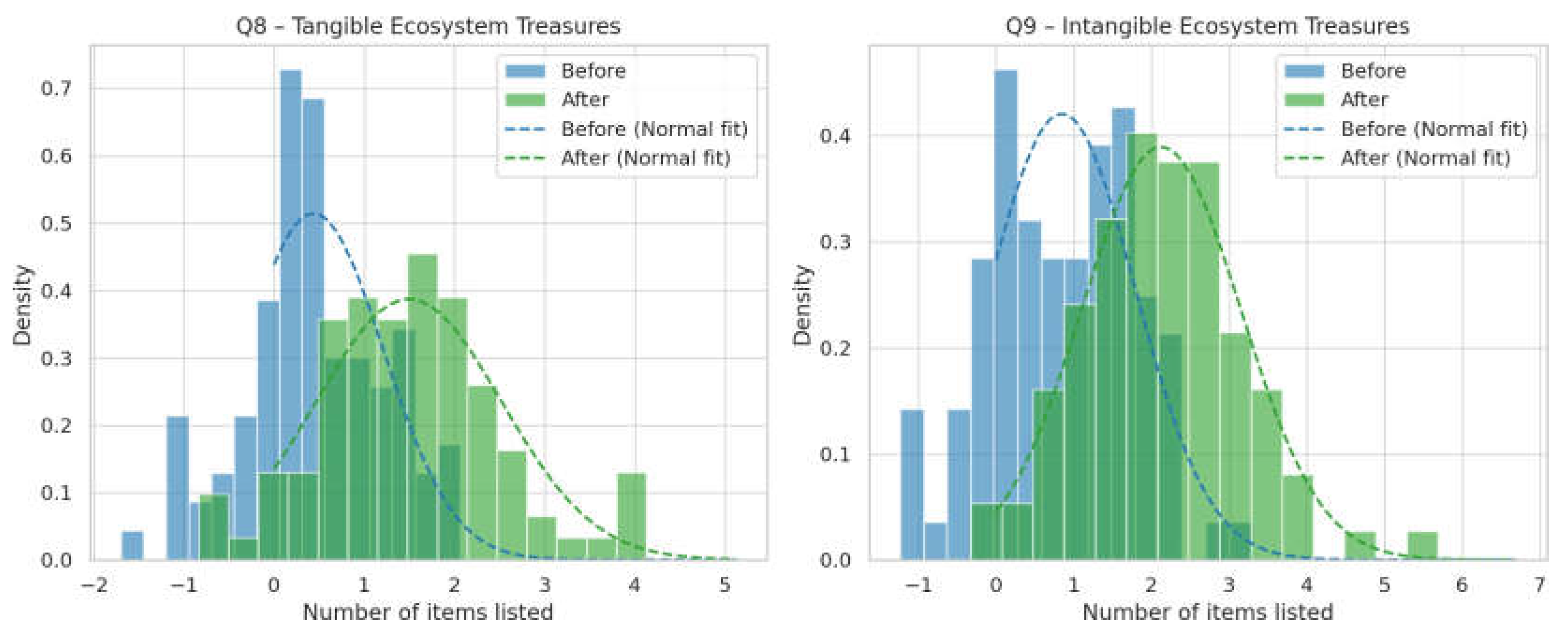

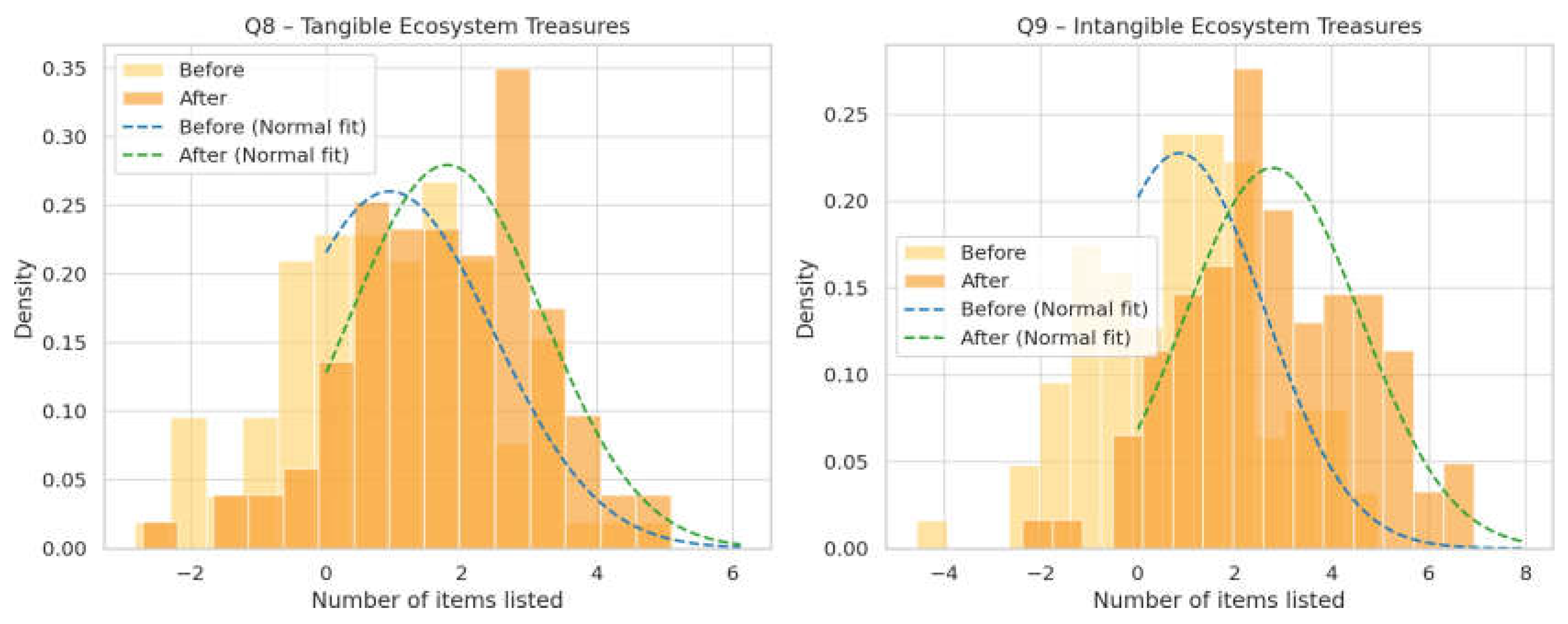

4.2. Comparison between Lecture and Workshop Groups

Independent-sample t-tests revealed significant differences in post-intervention outcomes (

Table 1,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2):

Local site awareness (Q5): Students in the workshop group showed significantly greater improvement compared to the lecture group (p = 0.017).

Intangible ecosystem values (Q9): A near-significant trend was observed in favor of the workshop group (p = 0.063).

Tangible goods (Q8): Both groups improved similarly, with no significant differences between them.

Awareness of other city green areas (Q6): No notable changes were detected in either group, suggesting that the intervention primarily influenced awareness of the specific study site rather than general urban greenery.

While both formats improved learning, the workshop had a stronger impact on students’ connection with place (Q5) and showed a near-significant trend in enhancing awareness of non-material ecosystem values (Q9). In the next section, we explore how these effects varied by participant profile.

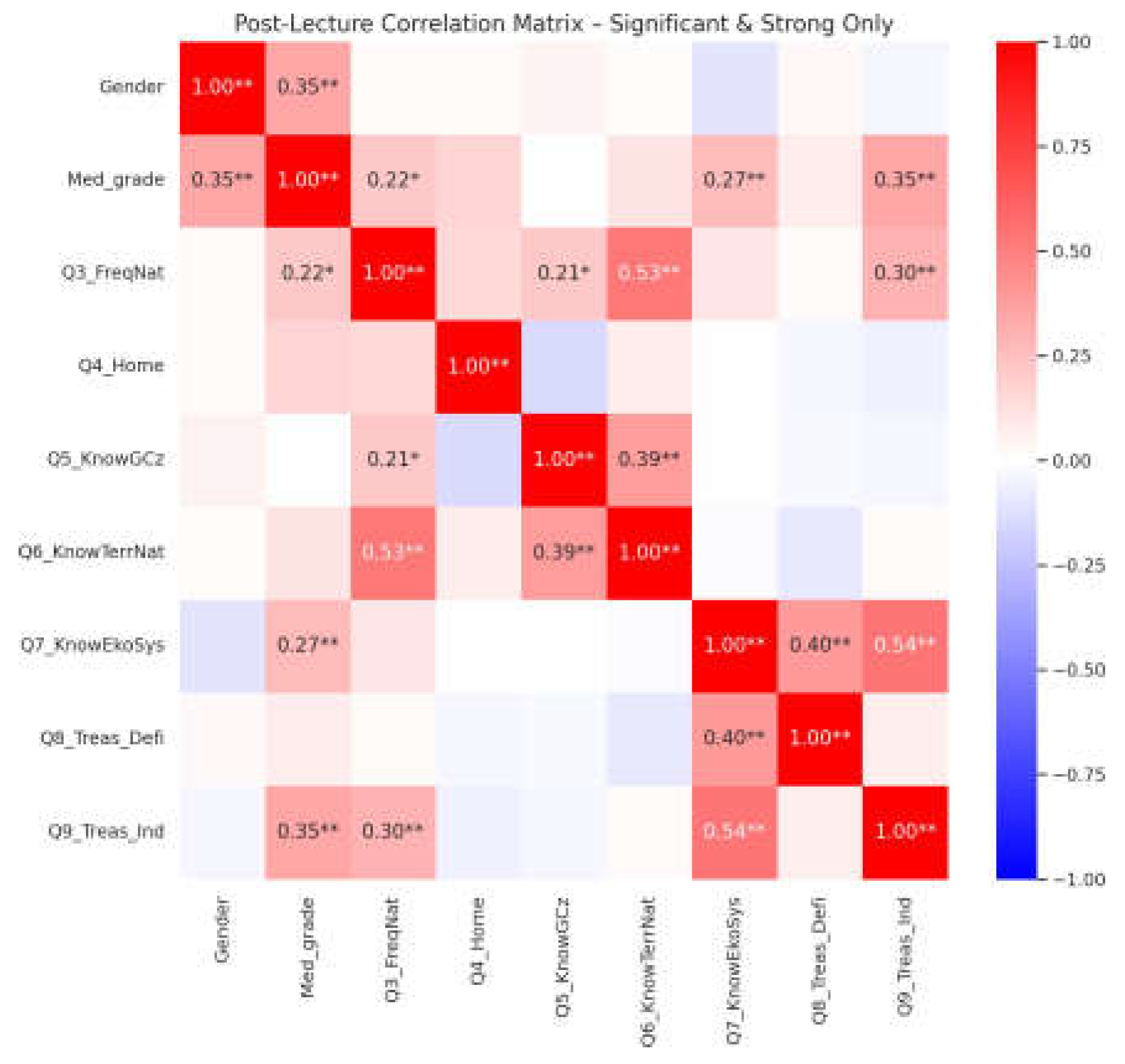

4.3. Correlational Patterns

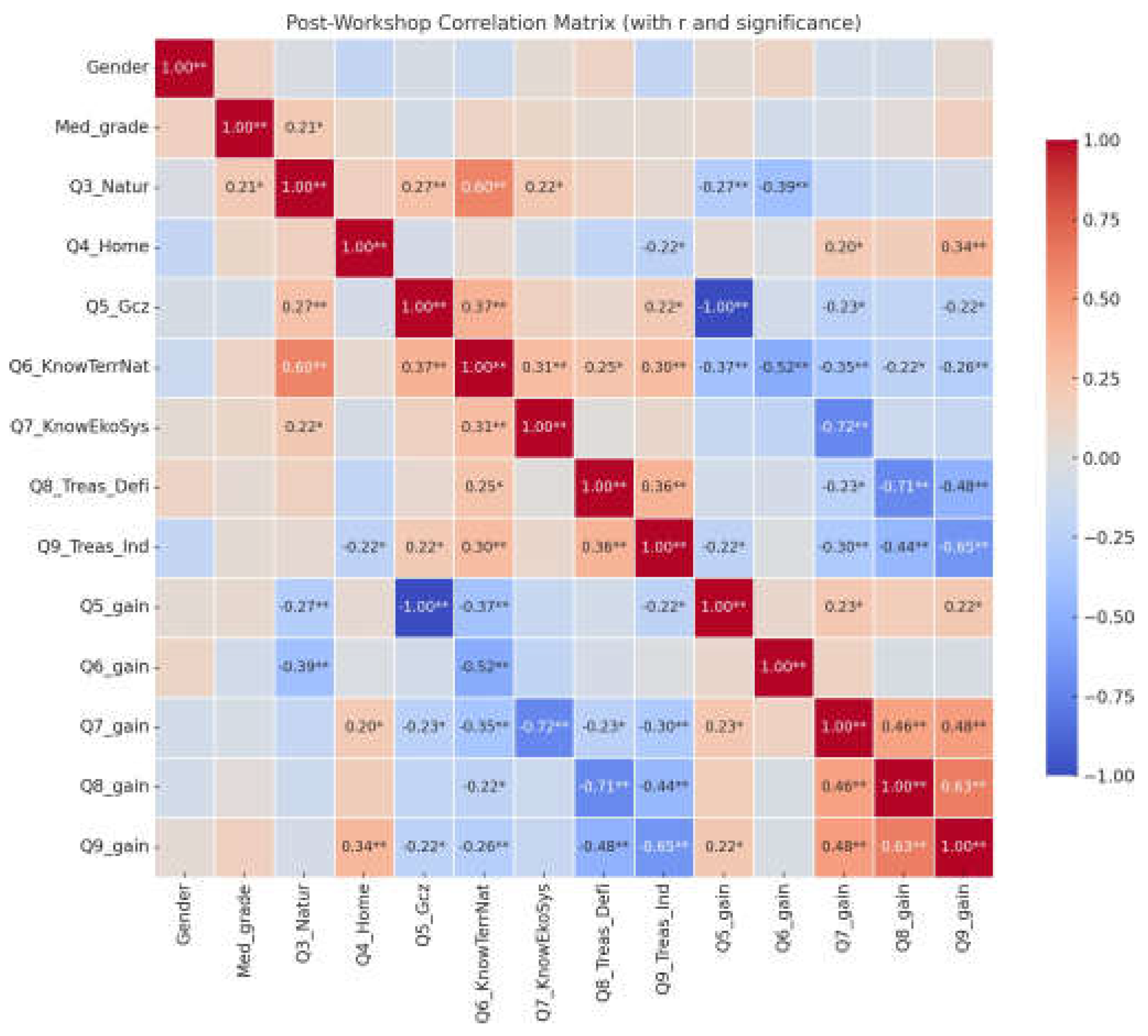

To better understand the patterns among students’ environmental attitudes and learning outcomes, we conducted Pearson correlation analyses separately for the Lecture and Workshop groups. Variables included Q3–Q9 (knowledge and valuation), nature visit frequency, living environment, academic grade, and—in the Workshop group—learning gains.

4.3.1. Lecture Group

Figure 3 reveals a coherent cluster of positive correlations between Q3 (nature visits), Q5 (local awareness), and Q6 (territorial knowledge), indicating a consistent nature-oriented lifestyle. Q7 (ecosystem knowledge) also correlates with both Q8 and Q9, suggesting that conceptual understanding supports recognition of ecosystem services. Notably, school grade correlates with gender (female), Q7, and Q9—implying that high-performing girls show stronger ecological awareness and value perception.

4.3.2. Workshop Group

In the Workshop group (

Figure 4), a strong inverse relationship appears between baseline scores and subsequent gains on Q5–Q9. This pattern suggests that students with lower initial knowledge benefitted most—highlighted by the blue squares in the lower-right section. Conversely, gains in Q7–Q9 are positively correlated, indicating that learning in one domain reinforced gains in others, especially regarding ecosystem functions and intangible values. Similar to the lecture group, Q3, Q5, and Q6 form a positively correlated cluster.

Interestingly, students living in detached homes showed the highest gains in Q9, suggesting a possible link between home setting and capacity to develop non-material environmental valuation.

4.3.3. Q6 as a Predictor of Environmental Awareness and Learning Outcomes

Item Q6 (“I can easily identify wild green areas in the city and I often go there”) strongly correlates with Q3 (nature visits; r = 0.60∗∗) and Q5 (local knowledge; r = 0.37∗∗), and moderately with Q7–Q8. This suggests that familiarity with urban nature reflects broader environmental engagement.

Notably, Q6 was negatively correlated with learning gains in Q5–Q9 (r from –0.22 to –0.52), implying that more experienced students gained less—likely due to ceiling effects.

To explore further, we analyzed correlation matrices for three subgroups based on Q6 level (High, Medium, Low).

In the Low Q6 group, strong negative correlations between baseline scores and gains indicate that students with least prior exposure learned the most. Gains across Q7–Q9 were also positively interrelated, suggesting a reinforcing learning dynamic once engagement was triggered.

The Medium Q6 group showed inconsistent patterns, likely due to mixed profiles -some students transitioning into nature-connectedness, others more passive. Further segmentation may clarify this group.

In the High Q6 group, learning gains were limited overall, but targeted effects emerged. Girls with high Q6 gained notably on Q5 (local site knowledge), showing that even informed students benefit from locally relevant content. This group may represent future peer educators or eco-leaders.

Similar patterns indicated the ceiling effect among students with high earlier knowledge of green areas, which was then confirmed in the regression analysis (section 4.4)

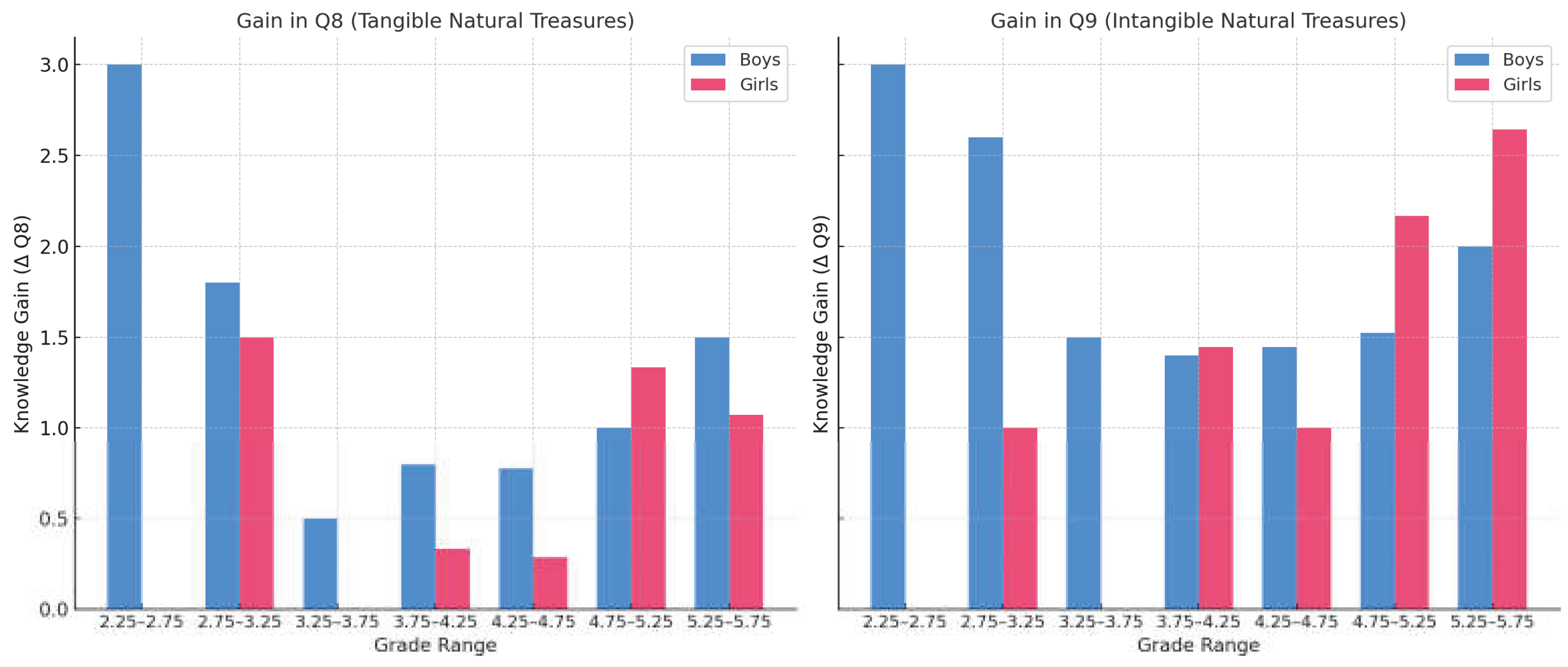

4.4. Subgroups: Gender and Academic Performance Effects

While overall correlation patterns did not highlight strong effects of gender or academic grade, further subgroup analysis revealed two distinct profiles of learners who benefited most from the workshop: low-performing boys and high-performing girls.

Figure A1 illustrates how learning gains in Q8 (tangible goods) and Q9 (intangible values) varied by gender and academic achievement. Boys with very low grades (

≤ 3.2) achieved the strongest gains, while girls with high grades (

≥ 5.0) also showed exceptional conceptual improvement.

To test whether these patterns were statistically significant, we performed Chi-square tests comparing the frequency of high vs. low gains in selected subgroups. Thresholds for "high gain" were set as follows: Q8/Q9

> 2.7 (boys), Q8

> 1.8 and Q9

> 2.5 (girls) – see

Table A4.

Interpretation with Counts

Boys with low academic grades (≤ 3.2) were significantly more likely to achieve high learning gains in both tangible (Q8) and intangible (Q9) ecosystem goods. Among this group, 4 out of 5 boys achieved high Q8 gains, and all 5 achieved high Q9 gains. In contrast, among higher-achieving boys (n=49), only 5 showed high Q8 gains and 17 showed high Q9 gains (χ2 = 12.65, p < 0.001 and χ2 = 5.54, p = 0.019, respectively).

Girls with very high academic grades (≥ 5.0) also showed a tendency toward stronger learning gains. Of 22 high-performing girls, 13 achieved high Q9 gains, compared to only 5 out of 23 girls with lower grades (χ2 = 5.07, p = 0.024). For Q8, the trend was similar (13 vs. 6 high-gain cases), but the result was only marginally significant (χ2 = 3.76, p = 0.0525).

These results suggest that both underperforming boys and high-achieving girls benefited most from the workshop, albeit in different cognitive dimensions.

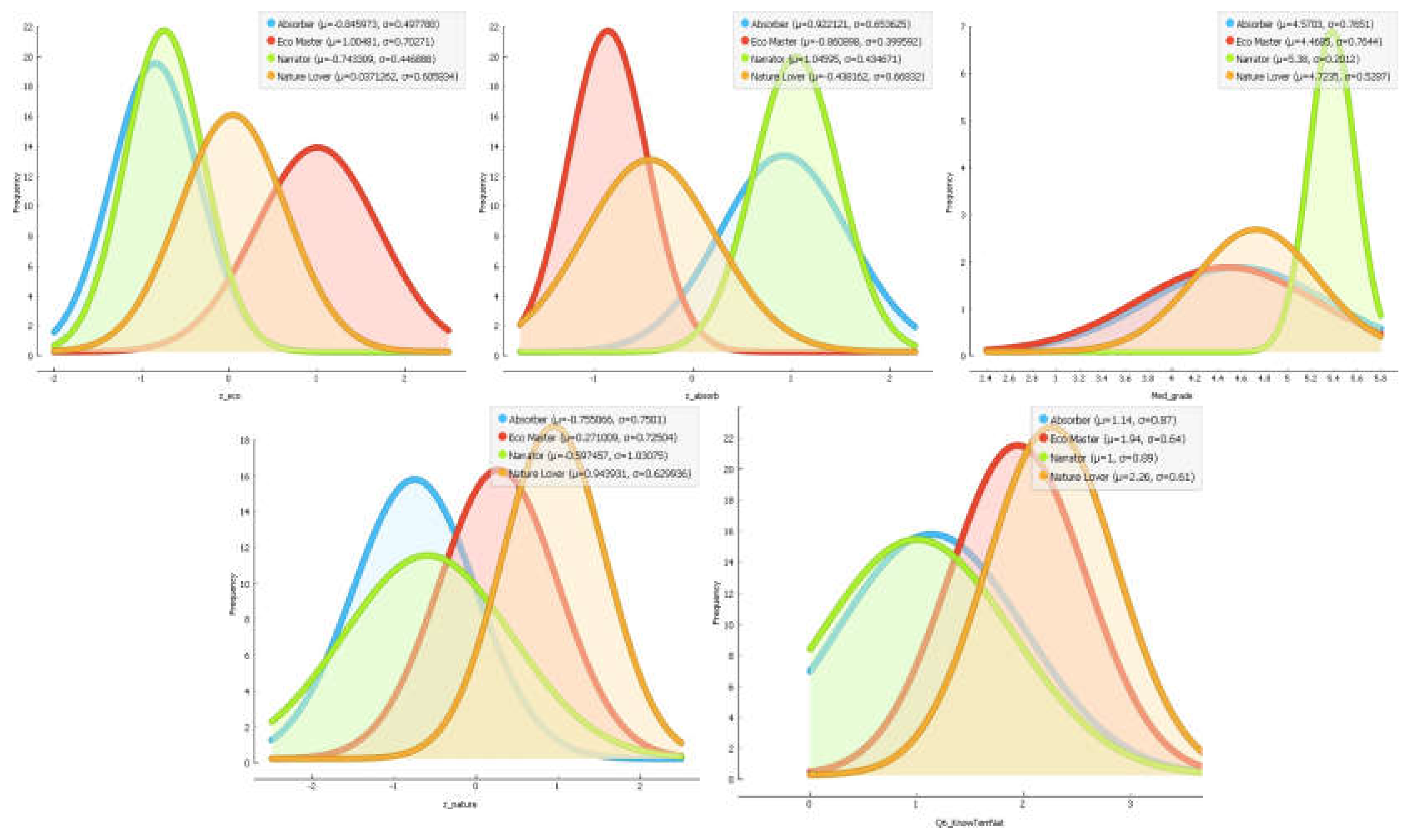

4.5. Composite Variables and Participant Typology

To explore variation among participants and identify emergent learning profiles, we constructed three composite scores from key survey items:

Nature Lover Score = Q3_Natur + Q6_KnowTerrNat + Q7_KnowEkoSys

Absorb Score = Q5_gain + Q6_gain + Q7_gain + Q8_gain + Q9_gain

Eco Master Score = Q5_Gcz + Q7_KnowEkoSys + Q8_Goods_Defi + Q9_Values_Ind

Participants were then assigned to one of four types using the following rules:

Narrators: female participants in the top 25% of Q8_gain or Q9_gain, and in the top 25% of Med_grade (academic performance).

Nature Lovers, Absorbers, Eco Masters: all remaining participants were assigned to the type for which they had the highest standardized composite score.

Each participant was assigned to only one type. To understand how these types differ in measurable terms, we calculated key descriptive statistics for each group, including learning gains (Q5–Q9), baseline contact with nature (Q3, Q6), and academic performance (Med_grade) - see

Table A5.

One-way ANOVA confirmed that these differences were statistically significant (p < 10−11 for all learning gains), validating the typology’s relevance in explaining divergent outcomes.

Based on these differences, we summarized each profile’s main characteristics, strengths, and limitations (

Table 2). We also illustrate differences between the types in

Figure 5.

This typology supports the idea that educational interventions should be diversified. Absorbers clearly benefited most from the workshop, while Eco Masters and Nature Lovers may require more advanced or tailored content. Interestingly, Narrators — despite their limited environmental exposure — achieved strong conceptual and reflective gains, suggesting that well-designed ecological education can activate verbal and analytical learning styles.

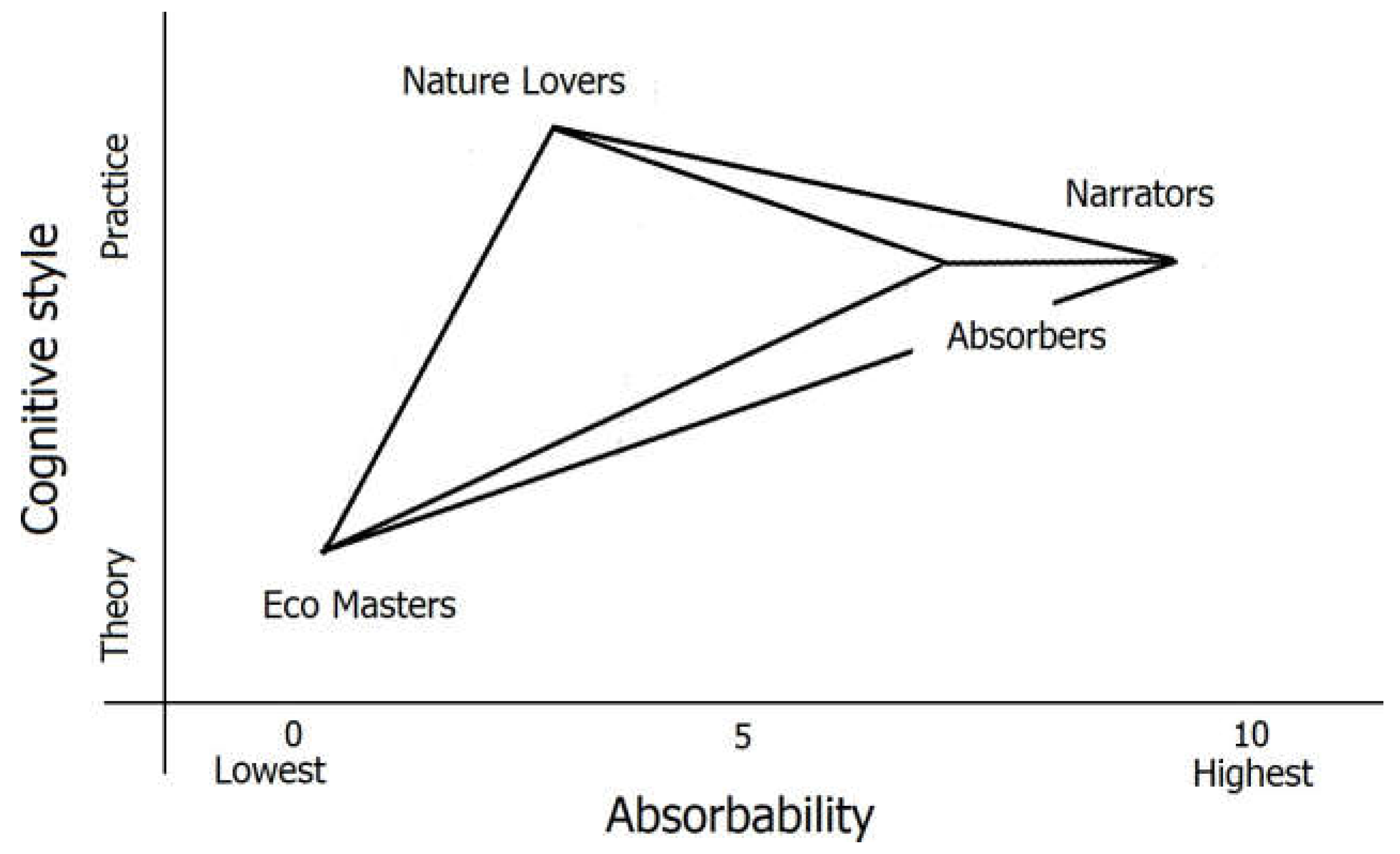

4.6. Cognitive Positioning of Participant Types

For each participant type, we calculated mean values of the selected indicators (baseline knowledge, frequency of nature contact, and learning gains). These group means served as centroids in a multidimensional space. Euclidean distances between these centroids were then computed to visualize the relative positioning of the four learner types.

Types were then plotted in a two-dimensional conceptual space, where:

The x-axis reflects absorbability – the potential for conceptual gain,

The y-axis shows a gradient from practice-oriented (Nature Lovers) to theory-oriented (Eco Masters).

As shown in

Figure 6, the types form a triangular structure, with

Narrators positioned close to

Absorbers, indicating shared cognitive responsiveness despite different initial profiles.

4.7. Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering

We applied PCA to the three composite indicators introduced in

Section 4.6. The first two components explained 83% of the variance (PC1: 66%, PC2: 17%). PC1 separated students with low baseline knowledge but high learning gains (Absorbers, Narrators) from those with higher prior knowledge or nature experience but limited gains (Eco Masters, Nature Lovers). PC2 reflected a weaker gradient combining academic performance with pro-nature orientation. K-means clustering yielded profiles consistent with the typology, confirming its robustness (

Table 3,

Figure 7).

5. Discussion

Our findings at least support that in-class lectures and outdoor workshops contribute to students’ knowledge gain on ES, the hands-on part of outdoor workshops is complementary to other didactic formats. Workshops increased LSA levels dramatically and showed promise in enhancing the recognition of intangible ecosystem values, an aspect of learning that is often hard to effect through conventional learning experiences.

5.1. Outdoor Workshops: Catalytic Resources for Place-Based Awareness

The outdoor workshops have a greater impact on locally-sited awareness (Q5), which is supported by place-based education and experiential learning theories [

9,

10]. Staying once in the Górki Czechowskie enabled students to experience abstract ecological notions in real life and connect them with the surrounding reality also through strengthening attachment to place. This supports previous research indicating the gains to students of developing deeper emotional and cognitive links with local ecosystems through outdoor learning [

11,

18].

5.2. Difficulties in Communicating Non-Use Ecosystem Value

Appreciation for intangible values (Q9), e.g. recreation, identity or aesthetics had only non-significant increase but still a trend towards outdoor calls to action. This corresponds to the widely-documented difficulty in communicating cultural ecosystem services [

3,

5]. These are subjective numbers, and they often do not make full sense until written in reflective or narrative forms. The results of our study indicate, that the implemented gamification and storytelling elements in the workshops helped to overcome this challenge partly; however additional pedagogical innovations might be necessary for transforming this values to a sustainable awareness.

5.3. Influence of Learner Characteristics

The study also demonstrates the significance of learner variation for educational results. Absorbers, those students with low initial knowledge, gained the most from experiential learning and had relatively higher gains across all aspects. This potential may be particularly pronounced for students who are averse to standard, theory-based instruction.

Meanwhile high-achieving girls (Narrators) showed very high increases on abstract values – a finding that coincided with previous studies of reflective and narrative work being most transformative for students who already have strong cognitive skills in this area [

7]. On the other hand, low-attaining boys made significant gains on concrete and abstract recognition in the workshops, which may have been facilitated by some of the more participatory and hands-on focus of these activities (i.e. providing alternative fora for involvement than school-work).

Eco-Masters and Nature Lovers, who started out with relatively high or frequent knowledge respectively had less room to grow (ceiling effect). This indicates that the "one size fits all" approach, typical of how workshops are designed, could be insufficiently challenging for advanced learners and that differentiated instruction activities like research-based projects, mentoring or citizen science may be more suitable for this subpopulation.

5.4. Educational and Policy Implications

The results of this study have important implications for education and highlight the limitations of a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Strategies need to be diversified to meet different learner profiles. For novices, the practical activities can function as an easy point of entry; for advanced pupils, harder challenges are required to avoid any sense of disrelation.

From a policy point of view, the research emphasizes the need to conserve and manage semi-natural green spaces within cities. In the case of places like Górki Czechowskie, their ecological and recreational functions are supplemented by opportunities for environmental education. Where urban development pressures build, the conservation of these areas may be warranted not only for biodiversity reasons but also their value as ‘‘living laboratories’’.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, it was a small sample from only two schools in one city, so the generalizability of the results is limited. Second, the interventions were of short duration and although some follow-up was provided, long-term retention of learning outcomes is not known. Third, the evaluation was mainly based on questionnaires self-reported by patients and we could not explore behavioral changes thoroughly.

Consequently, further work on a bigger scale including the other cultures would be recommended to obtain broader data regarding the potential long-term effects of environmental education and to gain integration across methods (e.g., behavioral observations, participatory mappings) in order to capture more extensively their multidimensional outcomes. It would also be useful to undertake comparative work across different cultural and urban settings, in order to test the generalizability of the learner profiles described here.

6. Conclusions

This study confirms that both the lecture and the field-based workshop were effective in enhancing students’ environmental understanding. However, the workshop—especially when delivered as a game-based outdoor experience—was uniquely successful in the whole group in promoting awareness of intangible ecosystem values (Q9), which are often overlooked in conventional curricula.

Based on observed differences in learning outcomes, we identified four recurring participant profiles—Absorbers, Narrators, Eco Masters, and Nature Lovers—and constructed three composite variables to support this typology. Subsequent PCA and clustering analyses and ANOVA tests validated this structure, revealing consistent patterns of engagement, learning, and prior ecological familiarity.

The workshop proved particularly beneficial for two distinct learner profiles:

Absorbers: students with limited baseline knowledge and nature experience but strong learning responsiveness;

Narrators: high-performing girls with small nature experience who achieved deep conceptual and reflective gains.

These groups gained the most from the intervention, confirming the value of hands-on and narrative-sensitive formats for both underprepared learners and high-achieving students with limited prior contact with nature.

Interestingly, the workshop was most effective for a third, less expected group: boys with low academic performance. Despite limited classroom engagement, they achieved the highest gains in both tangible (Q8) and intangible (Q9) ecosystem service understanding. This challenges conventional assumptions about who benefits from environmental education and highlights the unique potential of hands-on, place-based formats to engage students who are often overlooked in academic settings.

In contrast, participants with higher baseline knowledge—“Eco Masters”—and those with high direct experience in nature—“Nature Lovers”—showed little measurable gain. This was not due to disengagement, but rather to a ceiling effect: possibly the workshop’s content was too basic to activate their learning potential.

However, these students should not be viewed as a “lost” audience. Instead, they may be ready to contribute at a higher level of engagement—designing biodiversity surveys, mapping ecosystem services, mentoring peers, or facilitating value-based discussions about ecological trade-offs. Future programs could integrate such learners as junior collaborators or co-learners in interdisciplinary settings, offering a challenge even for undergraduate biology students.

Key insights:

Environmental learning gains vary significantly across student profiles — a one-size-fits-all model is suboptimal.

Narrative-driven, game-based formats activate not only factual learning but also reflective and value- based growth.

Prior nature experience and ecological knowledge, while important, may reduce the novelty effect of field interventions.

High-performing and underprepared students benefit most from engaging, well-designed outdoor education.

Future interventions should diversify formats to retain challenge and relevance for both novices and advanced learners.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.T and A.K.; methodology, M.N.K.; software, M.N.K.; validation, E.T., M.M.S. and A.K.; formal analysis, M.N.K.; investigation, M.M.S.; resources, M.M.S.; data curation, M.N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.K. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K.; visualization M.N.K.; supervision, E.T.; project administration, E.T.; funding acquisition, M.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Table A1.

Mean scores before and after the lecture (independent samples t-test).

Table A1.

Mean scores before and after the lecture (independent samples t-test).

| Question |

Before |

After |

Gain |

t

|

p

|

| Q5 Local awareness |

0.99 |

1.36 |

+0.37 |

–2.06 |

0.042 |

| Q6 KnowTerrNat |

1.67 |

1.69 |

+0.02 |

–0.12 |

0.902 |

| Q7 Ecosystem knowledge |

1.18 |

2.54 |

+1.36 |

–5.60 |

<0.001 |

| Q8 Tangible goods |

0.45 |

1.43 |

+0.98 |

–6.53 |

<0.001 |

| Q9 Intangible values |

0.68 |

2.09 |

+1.41 |

–7.68 |

<0.001 |

Table A2.

Mean scores before and after the workshop (paired samples t-test).

Table A2.

Mean scores before and after the workshop (paired samples t-test).

| Question |

Before |

After |

Gain |

t

|

p

|

| Q5 Local awareness |

1.29 |

2.00 |

+0.71 |

6.01 |

<0.001 |

| Q6 KnowTerrNat |

1.67 |

1.55 |

–0.11 |

–0.79 |

0.432 |

| Q7 Ecosystem knowledge |

1.62 |

2.71 |

+1.09 |

5.49 |

<0.001 |

| Q8 Tangible goods |

0.81 |

1.79 |

+0.98 |

5.63 |

<0.001 |

| Q9 Intangible values |

0.88 |

2.65 |

+1.77 |

8.94 |

<0.001 |

Table A3.

Significant predictors of learning gains (reference = Medium Q6)

Table A3.

Significant predictors of learning gains (reference = Medium Q6)

| Gain |

Predictor |

Coef. |

p |

CI 2.5% |

CI 97.5% |

| Q5 |

Q5 (pre) |

–1.00 |

<.001 |

–1.00 |

–1.00 |

| Q6 |

Q6 group: Low |

–2.06 |

<.001 |

–3.20 |

–0.91 |

| |

Q6 group: High |

+1.74 |

<.001 |

+0.83 |

+2.65 |

| |

Q5 (pre) |

+0.27 |

.018 |

+0.05 |

+0.49 |

| Q6 (pre) |

–2.01 |

<.001 |

–2.75 |

–1.27 |

| Q7 |

Q7 (pre) |

–0.96 |

<.001 |

–1.16 |

–0.76 |

| Q8 |

Q8 (pre) |

–0.80 |

<.001 |

–1.00 |

–0.60 |

| Q9 (pre) |

–0.25 |

.014 |

–0.45 |

–0.05 |

| Q9 |

School grade |

+0.46 |

.008 |

+0.12 |

+0.79 |

| |

Home setting |

+0.28 |

.041 |

+0.01 |

+0.54 |

| |

Q8 (pre) |

–0.39 |

.001 |

–0.61 |

–0.16 |

| |

Q9 (pre) |

–0.67 |

<.001 |

–0.90 |

–0.44 |

Figure A1.

Distribution of Q8 and Q9 gains by gender and academic grade. Boys with low grades and girls with high grades achieved the highest learning gains.

Figure A1.

Distribution of Q8 and Q9 gains by gender and academic grade. Boys with low grades and girls with high grades achieved the highest learning gains.

Table A4.

Chi-square tests: High vs. low gains in selected subgroups

Table A4.

Chi-square tests: High vs. low gains in selected subgroups

| Subgroup |

Variable |

High Gain |

Low Gain |

p-value |

| Boys, grade ≤ 3.2 |

Q8 |

4 |

1 |

0.0008 |

| Boys, grade ≤ 3.2 |

Q9 |

5 |

0 |

0.0190 |

| Girls, grade ≥ 5.0 |

Q8 |

13 |

9 |

0.0525 |

| Girls, grade ≥ 5.0 |

Q9 |

13 |

9 |

0.0240 |

Table A5.

Comparison of participant types: awareness, learning gains, and academic performance. Statistical differences between types are highly significant (ANOVA p < 10−11 for all learning gains)

Table A5.

Comparison of participant types: awareness, learning gains, and academic performance. Statistical differences between types are highly significant (ANOVA p < 10−11 for all learning gains)

| Type |

Total Gain |

Q6

(pre) |

Q3

(pre) |

Q8

Gain |

Q7

Gain |

Q9

Gain |

Med |

N |

| Absorber |

6.97 |

1.14 |

1.41 |

1.92 |

2.27 |

2.78 |

4.57 |

37 |

| Narrator |

9.00 |

1.00 |

1.60 |

2.80 |

2.80 |

3.40 |

5.38 |

5 |

| Eco Master |

0.44 |

1.94 |

1.74 |

–0.15 |

0.18 |

0.41 |

4.47 |

34 |

| Nature Lover |

2.70 |

2.26 |

2.61 |

0.74 |

0.17 |

1.78 |

4.72 |

23 |

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. Available online: https://www.millenniumassessment.org/en/Synthesis.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Díaz, S.; Pascual, U.; Stenseke, M.; Martín-López, B.; Watson, R.T.; Molnár, Z.; Hill, R.; Chan, K.M.A.; Baste, I.A.; Brauman, K.A.; et al. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science 2018, 359, 270–272. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Guerry, A.D.; Balvanera, P.; Klain, S.; Satterfield, T.; Basurto, X.; Bostrom, A.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Gould, R.; Halpern, B.S.; et al. Where are cultural and social in ecosystem services? A framework for constructive engagement. BioScience 2012, 62, 744–756. [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Bryan, B.A.; MacDonald, D.H.; Cast, A.; Strathearn, S.; Grandgirard, A.; Kalivas, T. Mapping community values for natural capital and ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 1301–1315. [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Dijks, S.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Bieling, C. Assessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community level. Land Use Policy 2015, 33, 118–129. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.A. Environmental Education in the 21st Century: Theory, Practice, Progress and Promise; Routledge: London, UK, 1998.

- Tilbury, D. Education for Sustainable Development: An Expert Review of Processes and Learning. UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000191442 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Stevenson, R.B.; Brody, M.; Dillon, J.; Wals, A.E.J. (Eds.) International Handbook of Research on Environmental Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013.

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984.

- Smith, G.A.; Sobel, D. Place- and Community-Based Education in Schools; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010.

- Rickinson, M.; Dillon, J.; Teamey, K.; Morris, M.; Choi, M.Y.; Sanders, D.; Benefield, P. A Review of Research on Outdoor Learning; National Foundation for Educational Research: Slough, UK, 2004.

- Beames, S.; Higgins, P.; Nicol, R. Learning Outside the Classroom: Theory and Guidelines for Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2012.

- Dichev, C.; Dicheva, D. Gamifying education: What is known, what is believed and what remains uncertain. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2017, 14, 9. [CrossRef]

- López-Rodríguez, M.D.; Castro, A.J.; Castro, H.; Montes, C. Exploring the role of common land for enhancing social–ecological resilience: A case study from Doñana, SW Spain. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 25. [CrossRef]

- Casado-Arzuaga, I.; Madariaga, I.; Onaindia, M. Perception, demand and user contribution to ecosystem services in the Bilbao Metropolitan Greenbelt. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 129, 33–43. [CrossRef]

- Pyle, R.M. Nature matrix: Reconnecting people and nature. Oryx 2003, 37, 206–214. [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pauleit, S.; Naumann, S.; Davis, M.; Artmann, M.; Haase, D.; Knapp, S.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; et al. Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas. Ecology and Society 2017, 22, 39. [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Extinction of experience: The loss of human–nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008.

- Larson, L.R.; Green, G.T.; Cordell, H.K. Children’s time outdoors: Results and implications of the National Kids Survey. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2019, 37, 34–51. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Pre/post distributions of tangible (Q8) and intangible (Q9) goods in Lecture group.

Figure 1.

Pre/post distributions of tangible (Q8) and intangible (Q9) goods in Lecture group.

Figure 2.

Pre/post distributions of tangible (Q8) and intangible (Q97) goods in Workshop group

Figure 2.

Pre/post distributions of tangible (Q8) and intangible (Q97) goods in Workshop group

Figure 3.

Correlation matrix in the Lecture group (only strong and significant associations shown; |r| ≥ 0.2; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Figure 3.

Correlation matrix in the Lecture group (only strong and significant associations shown; |r| ≥ 0.2; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Correlation matrix in the Workshop group including learning gains (only strong and significant associations shown; |r| ≥ 0.2; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Correlation matrix in the Workshop group including learning gains (only strong and significant associations shown; |r| ≥ 0.2; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

The four types: Absorbers (blue), Narrators (green), Eco Masters (red), Nature Lovers (orange) in the five comparison plots showing, consecutively: Eco Master Score, Absorb Score, Med_grade, Nature Lover Score, Q6 Knowing Local Terrains.

Figure 5.

The four types: Absorbers (blue), Narrators (green), Eco Masters (red), Nature Lovers (orange) in the five comparison plots showing, consecutively: Eco Master Score, Absorb Score, Med_grade, Nature Lover Score, Q6 Knowing Local Terrains.

Figure 6.

Cognitive positioning of participant profiles based on two conceptual dimensions: (i) Absorbability – horizontal axis (mean learning gains Q5–Q9), and (ii) Learning Style – vertical axis, from practice-oriented (Nature Lovers) to theory-oriented (Eco Masters). Narrators cluster with Absorbers in terms of responsiveness, despite different backgrounds.

Figure 6.

Cognitive positioning of participant profiles based on two conceptual dimensions: (i) Absorbability – horizontal axis (mean learning gains Q5–Q9), and (ii) Learning Style – vertical axis, from practice-oriented (Nature Lovers) to theory-oriented (Eco Masters). Narrators cluster with Absorbers in terms of responsiveness, despite different backgrounds.

Figure 7.

PCA of the three composite indicators (Nature Lover, Absorb, Eco Master). The first two components (83% variance explained) distinguish responsive learners (Absorbers, Narrators, right side) from knowledge-saturated profiles (Eco Masters, Nature Lovers, left side). Dot size reflects average school grade.

Figure 7.

PCA of the three composite indicators (Nature Lover, Absorb, Eco Master). The first two components (83% variance explained) distinguish responsive learners (Absorbers, Narrators, right side) from knowledge-saturated profiles (Eco Masters, Nature Lovers, left side). Dot size reflects average school grade.

Table 1.

Comparison of gains (Lecture vs Workshop).

Table 1.

Comparison of gains (Lecture vs Workshop).

| Question |

Lecture |

Workshop |

Diff (W–L) |

t |

p |

| Q5 Local awareness |

0.37 |

0.71 |

+0.34 |

–2.40 |

0.017 |

| Q6 KnowTerrNat |

0.02 |

–0.11 |

–0.13 |

0.86 |

0.389 |

| Q7 Ecosystem knowledge |

1.35 |

1.09 |

–0.26 |

1.25 |

0.214 |

| Q8 Tangible goods |

0.98 |

0.98 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.000 |

| Q9 Intangible values |

1.41 |

1.77 |

+0.36 |

–1.87 |

0.063 |

Table 2.

Participant profiles emerging from the combination of new indicators.

Table 2.

Participant profiles emerging from the combination of new indicators.

| Weaknesses |

Strengths |

Characteristics |

Type 1 |

| Low baseline compe- tence |

Open to learning, re- sponsive to workshop |

Low entry knowledge, low Q6, high gains |

Absorber |

| Little field experience prior to workshop |

Verbal reasoning, re- flective growth |

High gains in Q8/Q9, high grades, mostly female; low baseline exposure but ex- panded their environmental perspective |

Narrator |

| Gained little from in- tervention |

Conceptual clarity, prior knowledg |

High baseline knowledge (Q5 |

Eco Master |

| Low knowledge gains |

Real-world nature ex- perience |

High contact with nature |

Nature Lover |

Table 3.

Loadings of PCA components.

Table 3.

Loadings of PCA components.

| PC2 |

PC1 |

Variable |

| 0.357 |

0.597 |

z_absorb |

| 0.534 |

–0.527 |

z_nature_lover |

| –0.170 |

–0.606 |

z_eco_master |

| 0.748 |

–0.044 |

Med_grade |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).