1. Introduction

The zebrafish (

Danio rerio) is a small, omnivorous, freshwater teleost that tolerates wide ranges in temperature, salinity, and pH [

1,

2,

3]. Zebrafish are a popular model organism and are easy to maintain in the laboratory, as shown by the many different successful husbandry regimens, reviewed in Wilson [

4] and Licitra et al. [

5]. Husbandry regimens vary in their details, but a general practice for maintaining adult zebrafish is to supply a formulated feed at least once per day along with a daily supplement of live

Artemia (brine shrimp). Typically,

Artemia are cultured from cysts and collected after a day or two of culture. Although zebrafish do not eat

Artemia in the wild,

Artemia are a popular dietary supplement because they are highly nutritious and simple to culture [

6].

During the larval stage, zebrafish are quite vulnerable and raising them successfully requires more effort than maintaining juveniles or adults. Zebrafish are typically considered to enter the larval stage when the embryo hatches from its chorion and becomes free-swimming, at 3 days post fertilization (3 dpf). At this stage, larvae are 3.5 mm in total length [

7]. The time to reach the metamorphic stage is variable, but most larvae will have begun metamorphosis between 15 – 21 dpf [

8]. To support maturation, husbandry recommendations for larvae typically call for at least two daily feedings using a formulated commercial feed, as well as a supplement of either live

Paramecium or

Brachionus (rotifers) during the first weeks of life [

6,

9,

10]. The rationale for this feeding regimen is that paramecia (150-250 µm) and rotifers (~150-250 µm) are small and thus easily captured and ingested by larval zebrafish [

10]. By contrast,

Artemia nauplii are approximately two to four times larger in length than paramecia or rotifers [

10,

11], and it is generally thought that the relatively large size of

Artemia nauplii makes them unsuitable for newly-feeding larval zebrafish. Therefore, zebrafish laboratories often use rotifers or paramecia as the first live food, then transition to

Artemia when larvae are around two to four weeks old [

4,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Despite these recommendations for waiting to introduce

Artemia into the feeding regime, our lab has routinely achieved good results raising larval zebrafish without using paramecia or rotifers as a live food source. Instead, we supplement the larval zebrafish diet with live

Artemia franciscana nauplii, with the first feeding beginning at 5 dpf [

8]. Our success with this approach suggests that larval zebrafish are adept at capturing

Artemia from shortly after hatching. However, the feeding behavior of larval zebrafish capturing and ingesting live brine shrimp has not been previously investigated.

Here, we test the ability of larval zebrafish to capture newly-hatched, live Artemia nauplii. Our results show that larval zebrafish initially have a low success rate but rapidly become more adept at capturing Artemia as they grow. We raise cohorts of zebrafish on two different A. franciscana strains, San Francisco Bay (SFB) and Great Salt Lake (GSL), and find that feeding with either strain of Artemia leads to similar maturation rates for larval zebrafish. However, zebrafish larvae are more successful at capturing the SFB strain, with at least 50% of larvae eating a shrimp by 9 dpf, as measured by the presence of Artemia in the intestine. By contrast, we find that larvae fed the GSL strain reach 13 dpf before eating shrimp with a similar success rate. To better understand these unexpected differences in feeding behavior, we investigate whether there are size differences between the shrimp strains. Morphometric analyses show no size difference in length or width between the strains for newly-hatched nauplii collected 24 hours after culturing. However, significant differences in length are apparent after 48 hours of culture. We conclude that, when choosing which of these strains to include in a larval husbandry regimen, size of Artemia is not a significant factor if newly-hatched nauplii are used. Thus, either strain of newly-hatched A. franciscana can support zebrafish maturation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Zebrafish Husbandry

Wild-type zebrafish of the AB line and from a local pet store were maintained following standard methods [

6]. Adults were maintained on a commercial recirculating system with a daily light cycle of 14 hours light, 10 hours dark. Fertilized eggs were collected from overnight mating crosses and bleached [

6]. After bleaching, embryos were transferred to fish bowls at a density of 50 embryos per bowl. The bowls contained 0.5x E3 medium (2.5 mM NaCl, 0.085 mM KCl, 16.5 mM CaCl

2, 16.5 mM MgSO

4) supplemented with 0.01% methylene blue. The bowls were incubated at 28-29

oC until 5 dpf, when the larvae were transferred to a custom tabletop nursery as previously described [

8]. Briefly, at 5 dpf, larvae were transferred to 0.8 L tanks (Aquaneering) at a starting density of 50 larvae per tank in approximately 250 mL of 0.5x E3 medium. Tanks were maintained at 28-29

oC in the custom tabletop nursery on a natural light cycle. Larval zebrafish were fed daily with a formulated food mix at 9 am and 3 pm and live, newly-hatched

Artemia at noon. For 5-10 dpf larvae, the food mix consisted of equal parts Golden Pearl (GP) reef and larval fish diet 5-50 micron size and GP 50-100 micron size (Brine Shrimp Direct). For 11-15 dpf larvae, the food mix consisted of equal parts GP 50-100 and GP 100-200. Food mix (1 g/L) was suspended in 0.5x E3 medium for delivery to the tanks. Larvae were fed 1 mL per 10 fish.

2.2. Institutional Review Board Statement

All vertebrate animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Appalachian State University.

2.3. Brine Shrimp Husbandry

Encapsulated cysts of Artemia franciscana San Francisco Bay strain and Great Salt Lake strain were purchased from Brine Shrimp Direct and stored at 4oC with desiccant. Cysts were cultured in approximately 725 mL of 30% sea water (Instant Ocean) in a tabletop culture dish (Hobby, Dohse Aquaristik) at room temperature or in a water bath at 26-27oC. To make 30% sea water, Instant Ocean sea salts were dissolved in RO/DI water and aerated for at least 1 hour prior to use. For feeding zebrafish and for morphometric analyses, free-swimming Artemia were collected in a sieve by directing light over the sieve to attract the shrimp. Shrimp were rinsed thoroughly in 0.5x E3 medium and immediately fed to larval zebrafish.

2.4. Feeding Tests

Larval zebrafish feeding tests were performed using larvae from 5-15 dpf. Before testing, one tank was randomly selected and handled following the normal husbandry regimen with one modification: at the last feeding of formulated food, GP 5-50 (pale color) was substituted for the usual food mix (orange color) to enable unambiguous distinction between ingested brine shrimp (orange) and any remnants of the previous meal. The meal of pale formulated food was typically administered in the morning, 3 hours before the brine shrimp meal at noon. In some cases, the pale formulated food was instead administered in the evening, and the brine shrimp meal was delivered at 9 am the next morning. For the shrimp feeding tests, larvae in the selected tank were fed live, newly-hatched (instar I) brine shrimp nauplii and allowed to feed for 15-30 minutes before being collected for imaging. Each day, larvae were sampled from a new tank that had not been previously sampled so that each fish was sampled once, except for one tank that was measured on two subsequent days. Each sampled fish was assessed for whether or not a brine shrimp had been ingested. Multiple mating pairs were used for each experiment to generate multiple clutches. The SFB feeding test was performed two independent times and the GSL feeding test was performed once. On each imaging day, either a subset of the larvae from one tank was randomly selected for imaging or all larvae in the tank were imaged.

2.5. Larval Zebrafish Imaging

Larvae were anesthetized using several drops of MS-222 (4 mg/mL, pH 7) or by gradual addition to the tank water of ice chips made from 0.5x E3 medium, as described previously [

16]. Immediately after anesthetizing, a wide bore fire-polished Pasteur pipet was used to transfer larvae to a mold (#TU-1, Adaptive Science Tools) for imaging. The mold was made with 3% agarose in 0.5x E3 medium. Larvae were positioned laterally on the mold using a loop of fishing line. The intestinal contents were imaged through the transparent body wall using an Olympus SZX12 stereomicroscope. Larvae were immediately transferred to a recovery tank containing pre-warmed 0.5x E3 medium. Images were analyzed for presence or absence of

Artemia in the intestinal bulb.

To video record fish during feeding, a custom fish tank was constructed using glass slides and cover glass: 75 x 50 x 1 mm glass slides (Ted Pella Inc.), 25 x 75 x 1 mm microslides (VWR), and 36 x 60 mm number 1.5 cover glass (Ted Pella Inc.). The glass was cut using glass pliers (Ted Pella Inc.) to make a chamber that was 45 mm length x 35 mm height x 25 mm depth. The edges were glued together using aquarium sealant (Aqueon). The finished tank held 30 mL 0.5x E3 embryo medium. Several larval zebrafish at 9 dpf were transferred to the tank shortly before feeding brine shrimp and recording.

2.6. Artemia Morphometrics

Free-swimming

Artemia were collected either 24 or 48 hours after the start of the culture and were immobilized using club soda added to the culture medium as a narcotizing agent [

17].

Artemia were randomly selected with respect to sex. To sort metanauplii from nauplii in 48 hour cultures, we identified nauplii as shrimp with unsegmented bodies in the post-mandibular region, while metanauplii were recognized by segmented bodies, as described in Schrehardt [

18]. Immobilized

Artemia were transferred with culture medium to a 0.1 mm stage micrometer (Peak Glass scale 50) and imaged using an Olympus SZX12 stereomicroscope with a 0.5x plan fluorite objective, 70 mm working distance.

Artemia were positioned on the micrometer and imaged using transmitted light and an external light source. For consistency, each shrimp was oriented flatly on the dorsal side with the median naupliar eye (central eye spot) visible. Digital images were analyzed using ImageJ [

19]. For each image, the software was recalibrated using the stage micrometer before taking a measurement. Body length was determined by measuring the maximum length down the midline of the body from anterior to posterior. Width was determined at the widest point, excluding the appendages. For length and width, measurements were performed two independent times per strain and developmental stage by two different people.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism 7. For comparisons of shrimp length by strain and age, two-way ANOVA was used, followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. For comparisons of shrimp width by strain and age, two-way ANOVA was used, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

3. Results

3.1. Larval Zebrafish Feeding Tests

In previous studies, we found that zebrafish larvae can be raised successfully using newly-hatched

Artemia as a supplemental live food beginning with the onset of exogenous feeding at 5 dpf [

8]. However, this practice may not be typical, as only a few reports use a similar husbandry regimen. For young larval zebrafish, the gape is generally thought to be too small to ingest

Artemia [

10,

15,

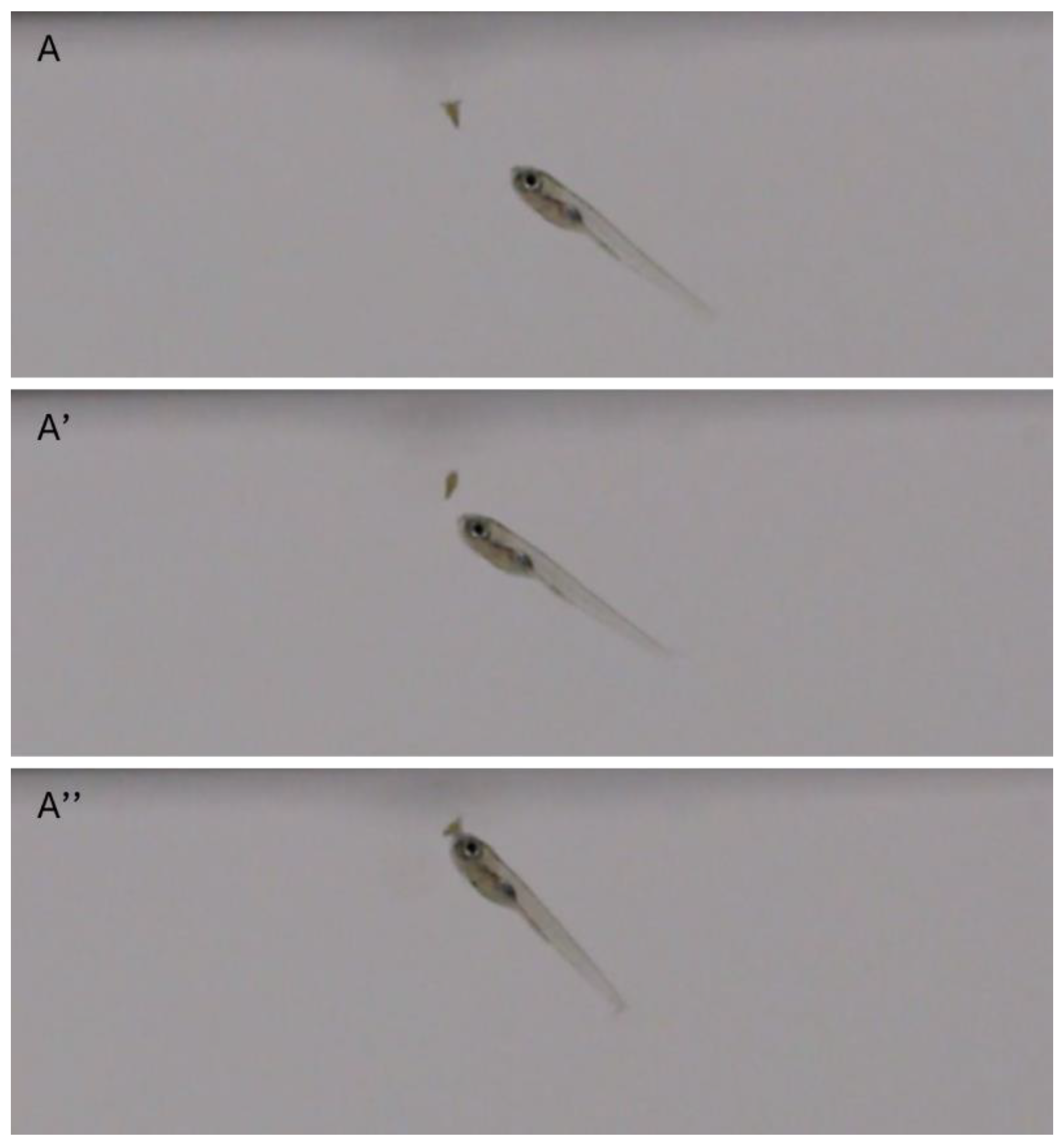

20]. Nevertheless, casual observation shows that shortly after delivering brine shrimp to a tank, at least a few larvae appear to have orange intestines, indicating they have ingested shrimp. Video recording of 9 dpf larvae suggests that suction feeding is used (

Figure 1 and Supplemental Video S1), and thus gape may not limit their ability to capture relatively large

Artemia. Because the success rate for larval zebrafish capturing

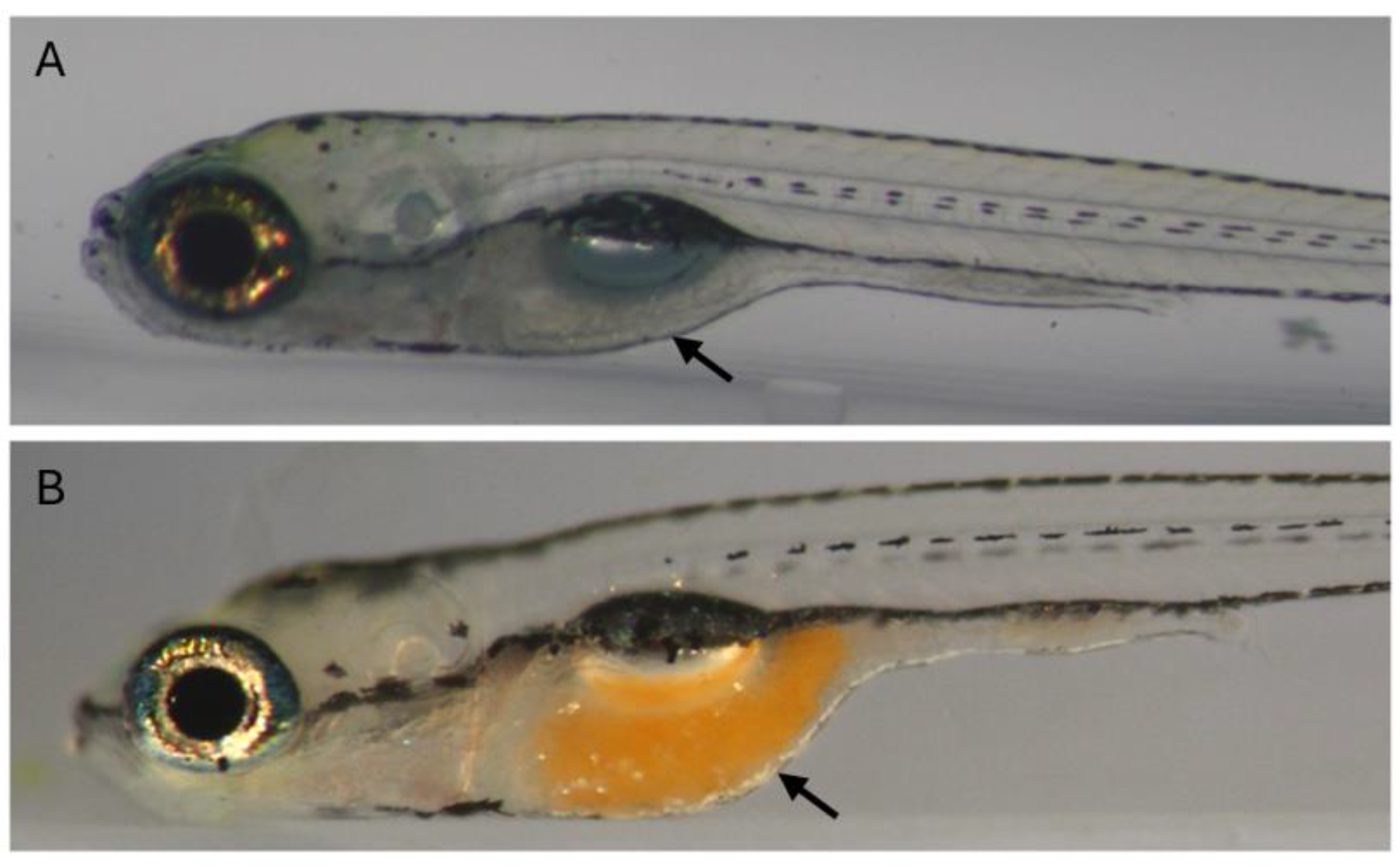

Artemia has not been formally investigated, we determined the capture success rate for larvae from 5-15 dpf. Because larval zebrafish have transparent body walls, our strategy was to image the intestinal contents through the body wall of live larvae to determine the presence or absence of shrimp (

Figure 2, panels). Newly-hatched live

A. franciscana SFB strain nauplii were delivered daily to tanks of wild-type zebrafish larvae. After 15-30 minutes of feeding, larvae were collected, anesthetized, and imaged. We found that larvae initially had limited success in capturing shrimp at 5 dpf and gradually became more adept with age (

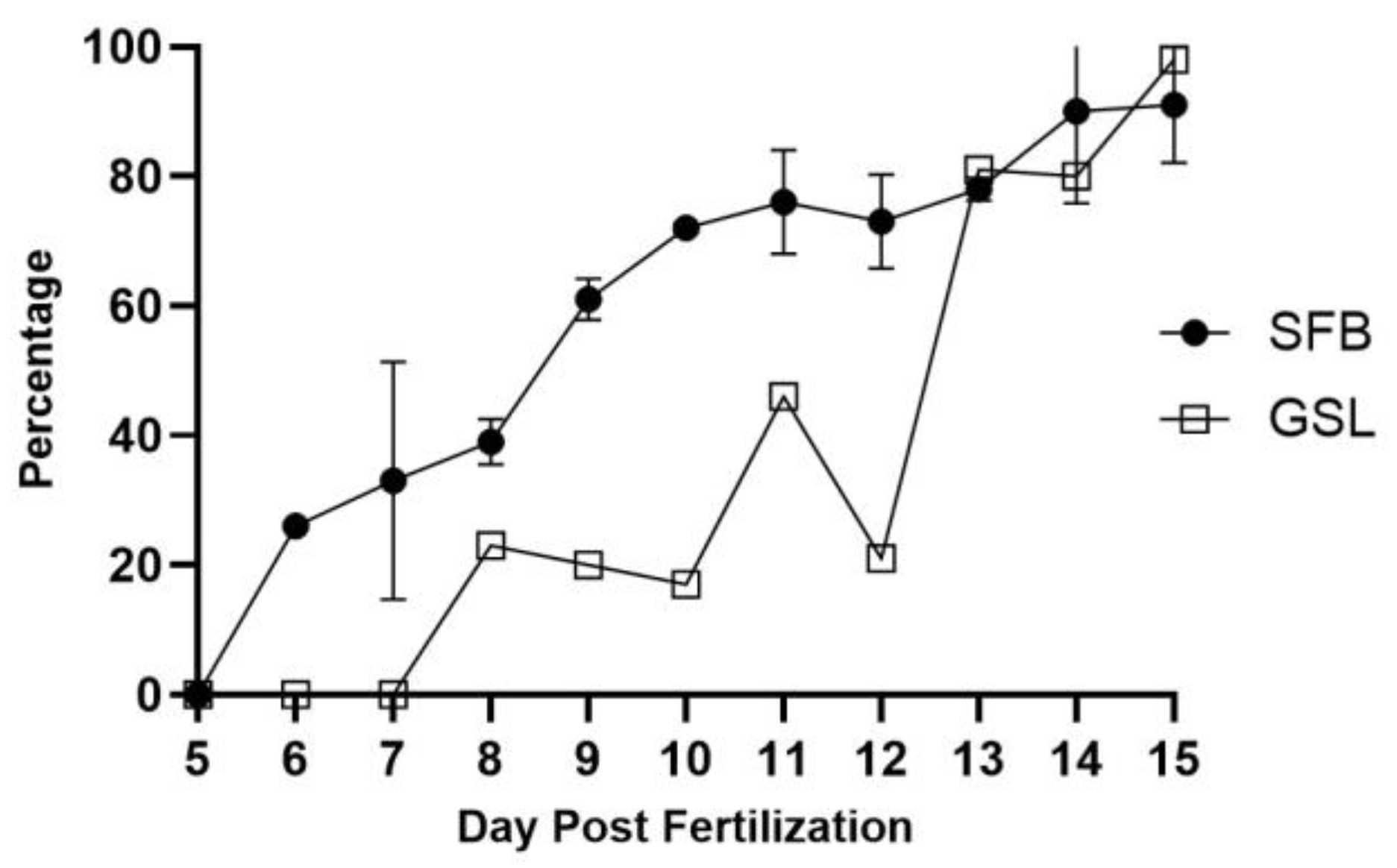

Figure 3 graph).

Next, we asked whether larvae would show a difference in ability to capture a different strain of

A. franciscana. We raised zebrafish larvae from 5-15 dpf using the same feeding strategy as above, but using the GSL strain instead of SFB. As shown in

Figure 2, larvae younger than 13 dpf captured the GSL strain less successfully than age-matched larvae fed the SFB strain. Given this delay in capturing shrimp, we asked whether larval progression to metamorphosis would be delayed. To assess this, we used swim bladder morphology to determine the percentage of larvae that were metamorphic at 15 dpf after being maintained on the GSL-supplemented diet versus larvae maintained on the SFB-supplemented diet. The swim bladder is an easily identifiable characteristic, as the larval swim bladder consists of a single, posterior lobe while larvae that have begun metamorphosis develop a second, anterior lobe [

21]. Based on swim bladder development at 15 dpf, 25% of GSL-supplemented larvae were metamorphic (of 44 screened), while 21% of SFB-supplemented larvae were metamorphic (of 58 screened). Therefore, we concluded that the lack of early feeding on

Artemia, particularly when feeding with the GSL strain, did not delay progression to metamorphosis.

3.2. Artemia Morphometrics

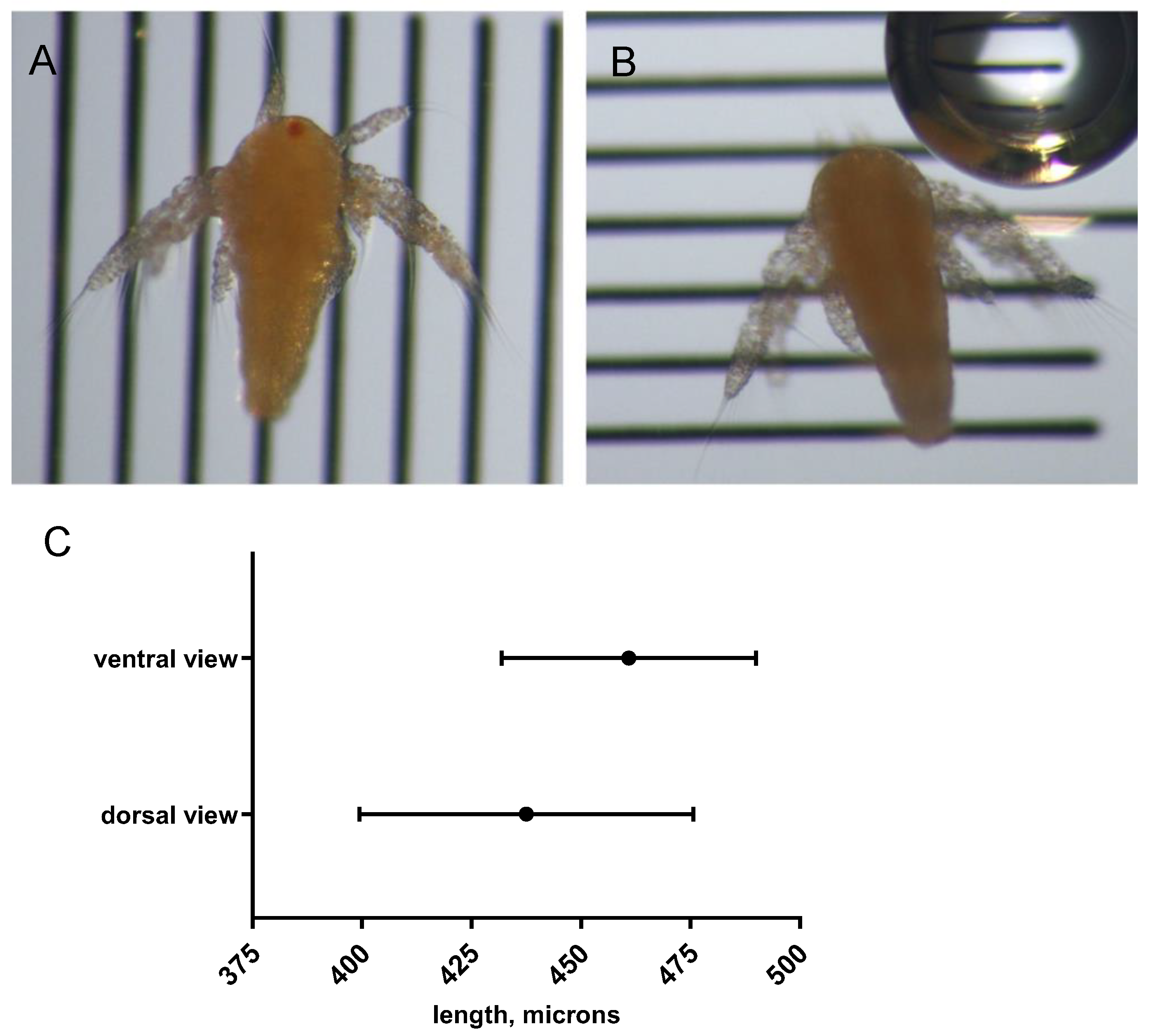

We next sought to determine whether size differences between the two shrimp strains contributed to the observed differences in larval zebrafish feeding behavior. To develop a strategy for measuring the brine shrimp, we first considered that nauplii have a relatively large labrum that projects from the ventral surface, which might tilt the nauplius enough to produce a foreshortened image when positioned on the ventral side (dorsal view). Additionally, the lateral appendages (antennae) curve ventrally at rest when nauplii are narcotized and could also contribute to tilting and foreshortening. Therefore, we tested whether the orientation mattered for length measurements. To do so, free-swimming nauplii of the SFB strain were collected after 24 hours of culture. We imaged 19 newly-hatched SFB nauplii in both orientations (dorsal and ventral views) and measured the maximum length (

Figure 4). We found that ventrally-positioned nauplii (in dorsal view) showed a shorter average length and a larger standard deviation (437.5 ± 38.13 μm) compared to orienting the same nauplii dorsally (in ventral view), which resulted in an average length of 460.9 ± 29.02 μm. The difference in length was statistically significant at P < 0.0001 (paired t-test, one-tailed). Therefore, we concluded that orienting the nauplius on its relatively flat, dorsal side improves the accuracy and precision of length measurements.

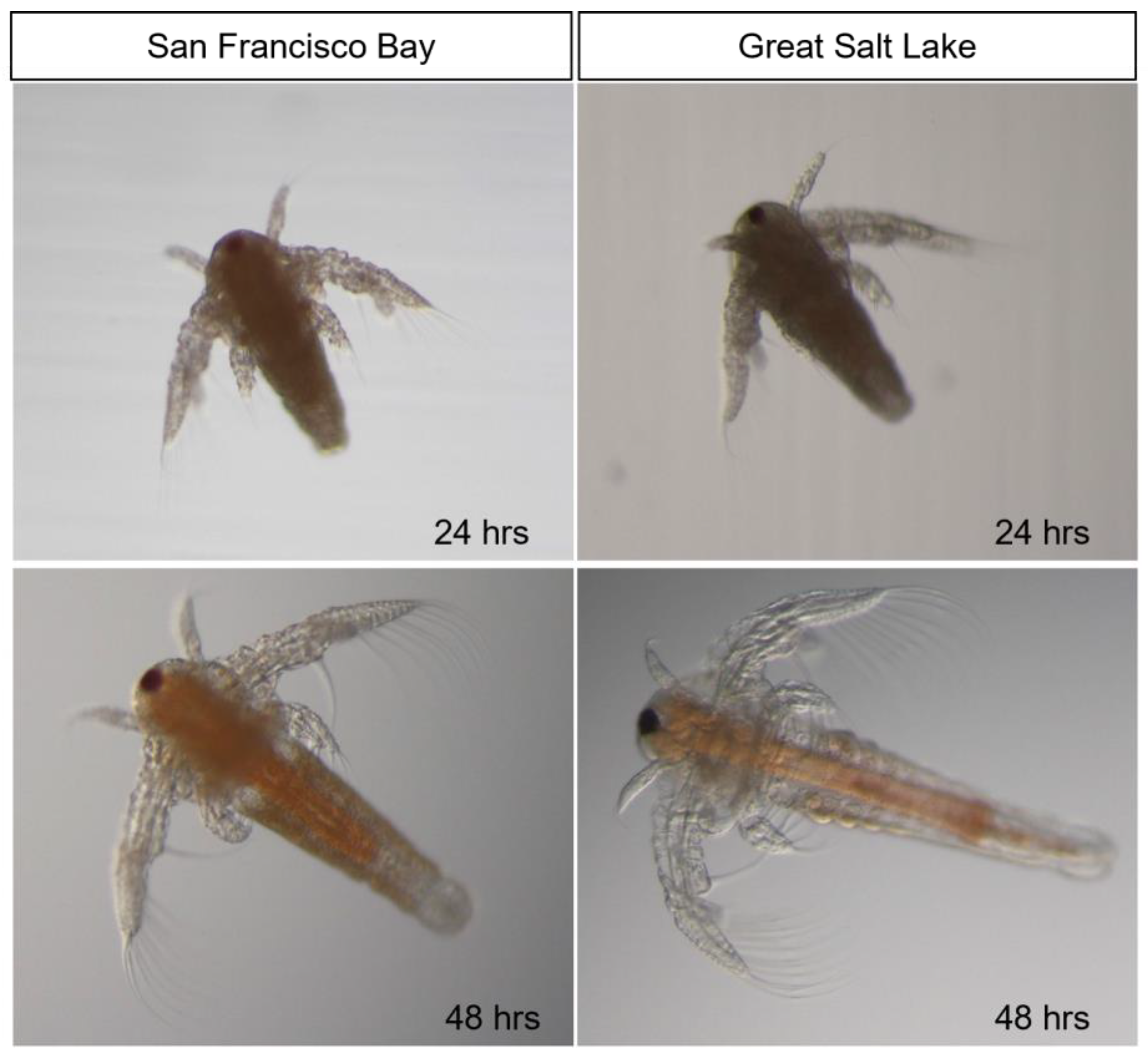

For subsequent

Artemia morphometric analysis, length measurements of both strains were made with each nauplius oriented on its dorsal side (

Figure 5). Because young zebrafish larvae showed relatively poor capture success when fed the GSL strain of

Artemia, we asked whether the GSL strain shrimp are significantly larger than the SFB strain and thus more difficult to capture. We first measured shrimp size at 24 hours after the onset of culturing, as our larval zebrafish feeding regimen utilizes 24 hour cultured brine shrimp. A comparison of the SFB and GSL strains by length at 24 hours was not significantly different (P = 0.9594,

Table 1). We further tested for a size difference by measuring maximum width of the same individual nauplii (

Table 1). This test also failed to distinguish between the strains (P > 0.9999). We concluded that there was no significant size difference between newly-hatched (24 hour cultured) SFB and GSL strains of brine shrimp.

Because these size comparisons contradicted the literature [

11,

22,

23] showing that the GSL strain is larger than the SFB strain, we tested whether a difference would become apparent after an additional day of culture. Because

Artemia hatch continuously, by 48 hours of culture the population is a mix of metanauplii and newly-hatched nauplii. Therefore, we sorted the metanauplii from obviously younger nauplii (

Figure 5) based on morphological criteria [

18]. We found that, when measuring metanauplii after 48 hours of culture, the strains were significantly different in length (

Table 1, P < 0.0001). However, we detected no significant difference in width between strains at 48 hours (P > 0.9649) or when comparing the newly-hatched nauplii with the metanauplii (P > 0.9823). This suggested that, between 24 and 48 hours of culturing, shrimp of both strains primarily grew in length.

4. Discussion

The larval zebrafish feeding tests confirmed our casual observations that larvae can capture live

A. franciscana beginning shortly after the onset of external feeding. Indeed, some researchers, including ourselves, have reported raising larval zebrafish successfully with

Artemia as the only live food included in the diet [

4,

8,

24,

25]. Here, we find that the small larval gape does not prevent capturing relatively large prey, similar to other teleosts. Bremigan and Stein [

26] showed that at least some larval teleosts eat zooplankton that are larger than larval gape. Our video recordings suggest that larval zebrafish use suction feeding to ingest the nauplius whole, without biting or otherwise crushing it. This may be analogous to how other teleosts with small gapes ingest prey. For example, seahorses and pipefish, despite having narrow jaws and small buccal cavities, are able to capture relatively large prey, including prey larger than their gape [

27,

28].

Our tests also demonstrated that larval zebrafish become more adept at capturing prey over time, similar to other larval species [

29]. For larval zebrafish, it is not clear whether increased prey capture over time is the result of physical maturation or learning. Studies by Cox and Pankhurst [

30] showed that greenback flounder larvae learn to capture prey, such that earlier exposure to live prey improves later capture ability. With a potential learning curve in mind, we routinely introduce brine shrimp to larval zebrafish starting at 5 dpf despite few larvae capturing shrimp in the first few days of external feeding.

To attempt to identify why young larval zebrafish were less successful at capturing the GSL strain compared with the SFB strain of

Artemia, we measured individual shrimp of both strains and found no differences in length or width after 24 hours of culture. This was unexpected, as zebrafish husbandry recommendations generally call for using the SFB strain of

A. franciscana, based in part on early studies reporting that the SFB nauplii are smaller than the GSL nauplii [

11,

22,

23,

31,

32]. However, we found that the SFB nauplii had a larger average length than previous reports indicated. Discrepancies between studies may result from employing different methods. In the earlier literature, the methods for measuring length were often not reported in detail, making it difficult to compare across studies. For example, some studies report using a microscope with an ocular micrometer (increments not specified), with no further details. We found no studies that reported how the nauplii were oriented, and here we have shown that measuring in dorsal view underestimates the length. Further, previous studies did not always report whether nauplii were live or fixed for the analysis. Fixation may introduce artifacts, including when using Lugol’s solution, a common fixative for zooplankton. For example, Vanhaecke and Sorgeloos [

11] reported fixing nauplii in 5% Lugol’s solution before measuring length. Lugol’s solution is known to swell or shrink tissues, depending on the length of fixation [

33,

34,

35].

Despite potential artifacts and differences in methodologies for measuring size, previous studies spanning multiple years and sampling different populations consistently demonstrate that the SFB strain is smaller than the GSL strain beginning with instar I nauplii. Evaluations of multiple strains from different geographical locations suggest that naupliar size and nutritional value vary not just between strains, but within populations of the same strain and from year to year, likely from changing environmental influences [

36,

37,

38]. Thus, it is difficult to predict the precise biometric characteristics of a specific sample. In addition, simply measuring length and width may not be a good predictor of overall size. We did not measure volume, which would account for the appendages that project from the body including the antennae, mandibles, and ventral labrum. The sizes of these structures may vary by

Artemia strain, and therefore volume measurements may show that the SFB strain used in the current study is indeed smaller than the GSL strain. We conclude that, while our measurements of the SFB strain of

Artemia were larger than expected, the size of the strain did not hinder larval feeding, and the SFB strain was more often captured by larvae compared with the GSL strain.

Finally, we include the SFB strain in our larval feeding regimen not only because the larval zebrafish capture these more readily at younger ages, but because several studies have shown that the SFB strain is more nutritious than the GSL strain, reviewed in Leger et al. [

39]. The SFB strain is typically recommended by commercial suppliers and by husbandry resources because it is higher in highly-unsaturated fatty acids (HUFA) than the GSL strain, and therefore likely better supports the rapid growth of larval fish. A drawback is the higher cost of the SFB strain. To mitigate cost, we raise larvae using the SFB strain until 15-21 dpf when the larvae have gone through metamorphosis. At that point, they are considered juveniles, are transferred from static tabletop nurseries to a recirculating system, and the diet is adjusted to include the GSL strain instead of the SFB. In the current study, while we did not find differences in time to metamorphosis for larvae fed on either strain, future studies should track additional metrics, for example, whether choice of

Artemia strain leads to differences in fecundity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Video S1: Larval zebrafish approaching brine shrimp.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K., S.S., T.D.; validation, M.K., S.S. and T.D.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, M.K., S.S., T.D.; resources, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, S.S., T.D.; project administration, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The vertebrate animal study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Appalachian State University, protocol number 2022-003 approved 08/19/2022, and protocol number 2023-0057 approved 03/16/2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Biology Department and the Office of Student Research of Appalachian State University for internal funding support. We thank Victor Nasr for contributing raw data included in Figure 3 and the vivarium staff of the College of Arts and Sciences at Appalachian State University for zebrafish husbandry support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample sizes for

Figure 3, capture success study.

Table A1.

Sample sizes for

Figure 3, capture success study.

Day post

fertilization |

SFB |

GSL |

| 5 |

|

50 |

50 |

| 6 |

|

50 |

50 |

| 7 |

|

85 |

50 |

| 8 |

|

87 |

43 |

| 9 |

|

149 |

40 |

| 10 |

|

88 |

36 |

| 11 |

|

93 |

48 |

| 12 |

|

72 |

34 |

| 13 |

|

70 |

47 |

| 14 |

|

25 |

49 |

| 15 |

|

70 |

45 |

References

- Arunachalam, M.; Raja, M.; Vijayakumar, C.; Malaiammal, P.; Mayden, R.L. Natural History of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) in India. Zebrafish 2013, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, R.; Fatema, M.K.; Reichard, M.; Huq, K.A.; Wahab, M.A.; Ahmed, Z.F.; Smith, C. The Distribution and Habitat Preferences of the Zebrafish in Bangladesh. Journal of Fish Biology 2006, 69, 1435–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, R.; Gerlach, G.; Lawrence, C.; Smith, C. The Behaviour and Ecology of the Zebrafish, Danio Rerio. Biological Reviews 2008, 83, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C. Aspects of Larval Rearing. ILAR Journal 2012, 53, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licitra, R.; Fronte, B.; Verri, T.; Marchese, M.; Sangiacomo, C.; Santorelli, F.M. Zebrafish Feed Intake: A Systematic Review for Standardizing Feeding Management in Laboratory Conditions. Biology 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerfield, M. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio); 5th ed.; University of Oregon Press: Eugene, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, T.F. The Morphology of Larval and Adult Zebrafish. In Zebrafish: A Practical Approach; Oxford University Press, 2002; pp. 59–94.

- Norton, A.; Franse, K.F.; Daw, T.; Gordon, L.; Vitiello, P.F.; Kinkel, M.D. Larval Rearing Methods for Small-Scale Production of Healthy Zebrafish. East Biol 2019, 2019, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, M.; Granato, M.; Nusslein-Volhard, C. Keeping and Raising Zebrafish. In Zebrafish: A Practical Approach; Oxford University Press, 2002; pp. 7–37 ISBN 978-0-19-963808-6.

- Harper, C.; Lawrence, C. The Laboratory Zebrafish; 1st, *!!! REPLACE !!!* (Eds.) ; CRC Press, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4398-0744-6.

- Vanhaecke, P.; Sorgeloos, P. International Study on Artemia. IV. The Biometrics of Artemia Strains from Different Geographical Origin. In The Brine Shrimp Artemia; Universa Press: Wetteren, Belgium, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski, K.; Miller, M. Contested Paradigm in Raising Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Zebrafish 2018, 15, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C. Advances in Zebrafish Husbandry and Management. In Methods in Cell Biology; Elsevier, 2011; Vol. 104, pp. 429–451 ISBN 978-0-12-374814-0.

- Osborne, N.; Paull, G.; Grierson, A.; Dunford, K.; Busch-Nentwich, E.M.; Sneddon, L.U.; Wren, N.; Higgins, J.; Hawkins, P. Report of a Meeting on Contemporary Topics in Zebrafish Husbandry and Care. Zebrafish 2016, 13, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, Z.M. Aquaculture and Husbandry at the Zebrafish International Resource Center. In Methods in Cell Biology; Elsevier, 2011; Vol. 104, pp. 453–478 ISBN 978-0-12-374814-0.

- Eames Nalle, S.C.; Franse, K.F.; Kinkel, M.D. Analysis of Pancreatic Disease in Zebrafish. In Methods in Cell Biology; Elsevier, 2017; Vol. 138, pp. 271–295 ISBN 978-0-12-803473-6.

- Goswami, S.C. Zooplankton Methodology, Collection and Identification: A Field Manual; National Institute of Oceanography: Goa, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schrehardt, A. A Scanning Electron-Microscope Study of the Post-Embryonic Development of Artemia. In Artemia Research and its Applications; 1987; Vol. 1, pp. 5–32.

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, L.P. Intraspecific Scaling of Feeding Mechanics in an Ontogenetic Series of Zebrafish, Danio Rerio. Journal of Experimental Biology 2000, 203, 3033–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parichy, D.M.; Elizondo, M.R.; Mills, M.G.; Gordon, T.N.; Engeszer, R.E. Normal Table of Postembryonic Zebrafish Development: Staging by Externally Visible Anatomy of the Living Fish. Developmental Dynamics 2009, 238, 2975–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, C.D.; Lovell, R.T. Quality Evaluation of Four Sources of Brine Shrimp Artemia Spp. J World Aquaculture Soc 1990, 21, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.E. Larval Feeding and Rapid Maturation of Bluegills in the Laboratory. The Progressive Fish-Culturist 1976, 38, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.P.; Araujo, L.; Santos, M.M. Rearing Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Larvae without Live Food: Evaluation of a Commercial, a Practical and a Purified Starter Diet on Larval Performance. Aquaculture Res 2006, 37, 1107–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minchin, J.E.N.; Rawls, J.F. In Vivo Imaging and Quantification of Regional Adiposity in Zebrafish. In Methods in Cell Biology; Elsevier, 2017; Vol. 138, pp. 3–27 ISBN 978-0-12-803473-6.

- Bremigan, M.T.; Stein, R.A. Gape-Dependent Larval Foraging and Zooplankton Size: Implications for Fish Recruitment across Systems. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1994, 51, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, B.; Xie, S.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Y.; Cui, P.; Yu, X.; Xia, S.; Lin, Q.; Qin, G. Kinematics of Prey Capture and Histological Development of Related Organs in Juvenile Seahorse. Aquaculture 2021, 541, 736732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.M.; Geraldi, R.M.; Vieira, J.P. Diet Composition and Feeding Strategy of the Southern Pipefish Syngnathus Folletti in a Widgeon Grass Bed of the Patos Lagoon Estuary, RS, Brazil. Neotrop. ichthyol. 2005, 3, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.M.; Lenz, P.H. Predator-Prey Interactions in the Plankton: Larval Fish Feeding on Evasive Copepods. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 33585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, E.S.; Pankhurst, P.M. Feeding Behaviour of Greenback Flounder Larvae, Rhombosolea Tapirina (Günther) with Differing Exposure Histories to Live Prey. Aquaculture 2000, 183, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stappen, G. Artemia. In Manual on the Production and Use of Live Food for Aquaculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 1996; pp. 79–106. [Google Scholar]

- Torrentera, L; Dodson, S. I. Morphological Diversity of Populations of Artemia (Branchiopoda) in Yucatan. Journal of Crustacean Biology 1995, 15, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinabu, G.M.; Bott, T.L. The Effects of Formalin and Lugol’s Iodine Solution on Protozoal Cell Volume. Limnologica - Ecology and Management of Inland Waters 2000, 30, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, P.R.; Holliday, J.; Kathuria, A.; Bowling, L. Change in Cyanobacterial Biovolume Due to Preservation by Lugol’s Iodine. Harmful Algae 2005, 4, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menden-Deuer, S.; Lessard, E.; Satterberg, J. Effect of Preservation on Dinoflagellate and Diatom Cell Volume, and Consequences for Carbon Biomass Predictions. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001, 222, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, P.S.; Johns, D.M.; Olney, C.E.; Simpson, K.L. International Study on Artemia IX. Lipid Level, Energy Content and Fatty Acid Composition of the Cysts and Newly Hatched Nauplii from Five Geographical Strains of Artemia. In The Brine Shrimp Artemia. In The Brine Shrimp Artemia; Universa Press: Wetteren, Belgium, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, J.; Castro, T.; Sánchez, J.; Castro, G.; Castro, A.; Zaragoza, J.; De Lara, R.; Monroy, M.D.C. Cysts and Nauplii Biometry Characteristics of Seven Artemia Franciscana (Kellog, 1906) Populations from Mexico. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 2006, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Naceur, H.; Ben Rejeb Jenhani, A.; Romdhane, M.S. Variability of Artemia Salina Cysts from Sabkhet El Adhibet (Southeast Tunisia) with Special Regard to Their Use in Aquaculture. Inland Water Biol 2010, 3, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, P.; Bengtson, D.A.; Simpson, K.L.; Sorgeloos, P. The Use and Nutritional Value of Artemia as a Food Source. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev. 1986, 24, 521–623. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).