Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

16 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area and Experimental Procedures

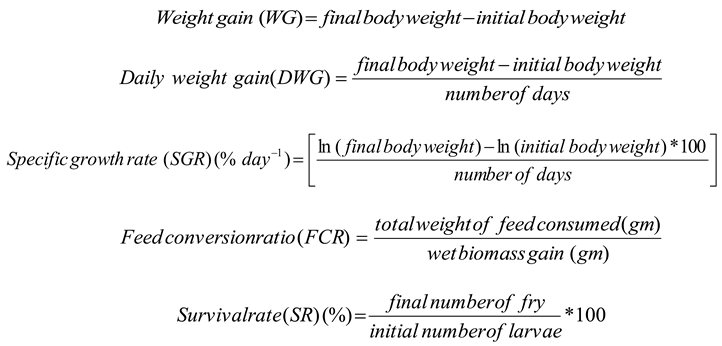

2.2. Growth Parameters and Nutritional Utilization

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Water Quality Paramters

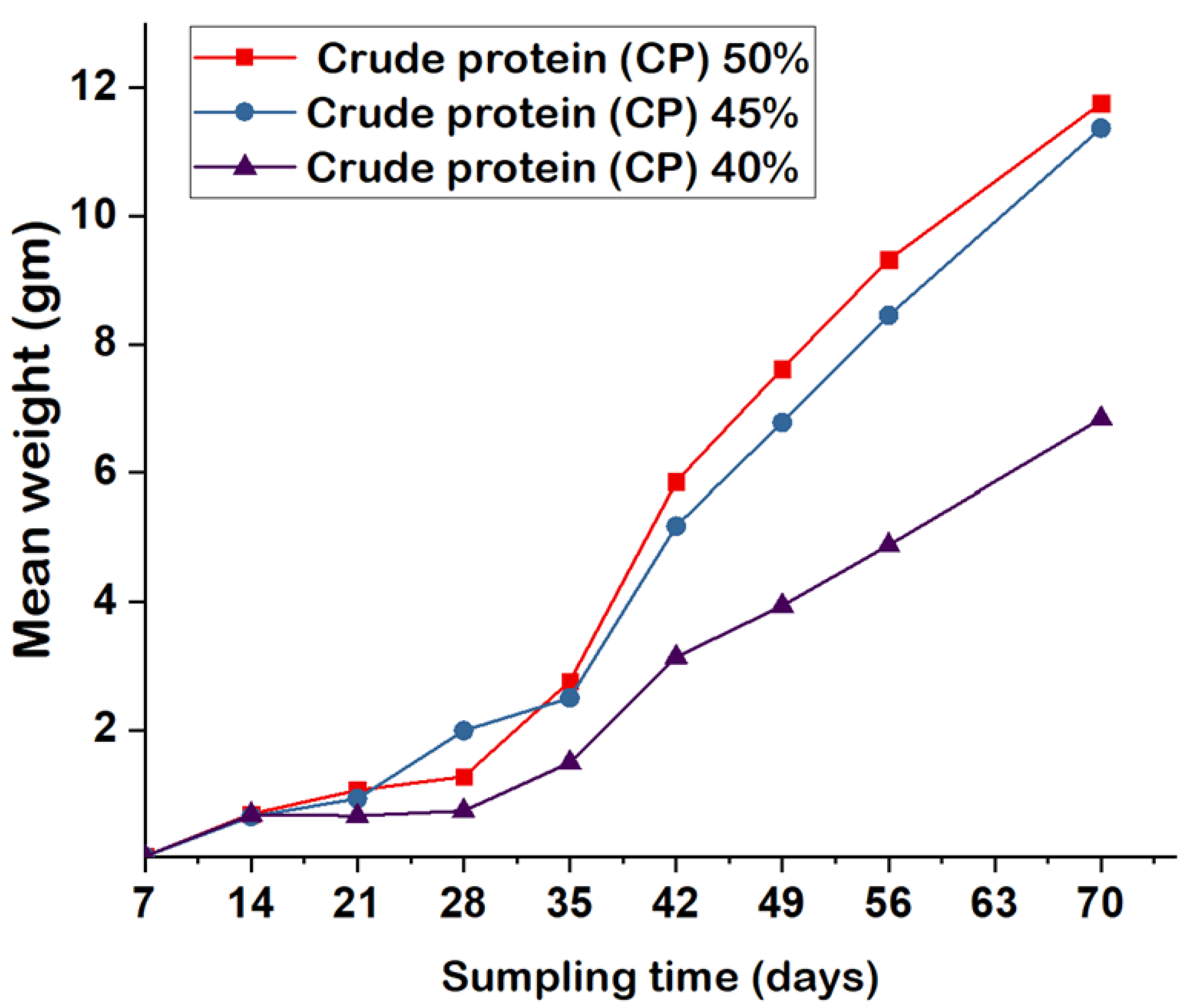

3.2. Growth Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Water Quality Paramters

4.2. Growth Performance

5. Conclusion and Recommendation

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Ponzoni RW, Nguyen NH. Proceedings of a Workshop on the Development of a Genetic Improvement Program for African Catfish, Clarias gariepinus. Accra, Ghana, 2008; 131 pages.

- Adewolu M A, Adeniji CA, Adejobi B. Feed utilization, growth and survival of Clarias gariepinus (Burchell 1822) fingerlings cultured under different photoperiods. Aquaculture, 2008; 283: 64–67. [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture Sustainability in action, 2020; Rome.https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9229en. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid AM, Radwan AI, Mehrim AF. Improving the survival rate of the African catfish, Clarias gariepinus. Journal of Animal and Poultry Production, Mansoura University, 2010; 1: 409-414.

- Chepkirui-Boit V, Ngugi CC, Bowman J. Growth performance, survival, feed utilization, and nutrient utilization of African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) larvae co-fed Artemia and a micro-diet containing freshwater atyid shrimp (Caridina nilotica) during weaning. Journal of aquaculture nutrition, 2011; 17: 82-89. [CrossRef]

- Giri SS, Sahoo SK, Sahu BB, Sahu AK, Mohanty SN. Larval survival and growth in Wallago mattu (Bloch and Schneider): Effects of light, photoperiod and feeding regimes. Aquaculture, 2002; 213: 151–161.

- Kolkvoski S. Digestive enzymes in fish larvae and juveniles: implications and application to formulated diets. Aquaculture, 2001: 181–201.

- Verreth J. Nutrition and Related Ontogenetic Aspect in Larvae of the African Catfish, Clarias gariepinus. Ph.D Thesis, University of Wageningen, 1994; Wageningen.

- Nyina-Wamwiza L, Wathelet B, Kestemont P. Potential of local agricultural by-products for the rearing of African catfish Clarias gariepinus in Rwanda: effects on growth, feed utilization, and body composition, Aquaculture Research, 2007; 38: 206–214. [CrossRef]

- Jones DA, Karnarudin MH, Le Vay L. The potential for replacement of live feeds in larval culture. J. World Aquaculture. Soc., 1993; 24: 199–207. [CrossRef]

- Person-Le Ruyet J, Alexandre JC, Thebaud L, Mugnier C. Marine fish larvae feeding: formulated diets or live prey. J. World Aquaculture. Soc.1993; 24: 211–224. [CrossRef]

- Moshood KM, Bolarinwa FA, Charles AF. Comparative effect of local and foreign commercial feeds on the growth and survival of Clarias gariepinus juveniles. Journal of Fisheries, 2014; 2 (2): 106-112. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.17017/jfish.v2i2.2014.25. [CrossRef]

- Ogugua NM, Eyo JE. Fish feed technology in Nigeria. Journal of Research in Bioscience, 2014; 3. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231683748.

- Halver JE, Hardy RW. Fish nutrition, London, Academic Press, 2002: An imprint of Elsevier Science.

- Ibrahim EH. A review of some fish nutrition methodologies, Bioresource Technology, 2005: 395–402.

- Kassahun A, Waidbacher H, Munguti JM, Zollitsch WJ. Locally available feedstuffs for small-scale aquaculture in Ethiopia- a review, 2012.

- Zenebe T, Abeba W, Mulugeta J, Fekadu T, Fasil D. Effect of supplementary feeding of agro-industrial by-products on the growth performance of Nile Tilapia (O.niloticusl) in concrete ponds.Ethiopian J. Biol.Sci., 2012; 11: 29-41.

- Abelneh Y, Zenebe T. Growth performance and economic viability of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.) fed on two formulated diets in the concrete pond, Sebeta/ Ethiopia, publish, pp. 13-34. In: EFASA (2017). Proceedings of the 9th annual conference of EFASA, 24-25 February 2017, Dessie, Ethiopia, 2017; 191 pp. ISBN: 978-999444-910-3-2.

- Alemayehu W, Adamneh D. Survival rate of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) larvae reared in a hatchery. IJASR, 2022; 5:43-46.

- Olurin KB, Oluwo AB. Growth and Survival of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) Larvae Fed Decapsulated Artemia, Live Daphnia, or Commercial Starter Diet, 2010; 62(1): 50-55. [CrossRef]

- Horváth LJr, Tamás G, Coche AG. Common carp: Mass production of eggs and early fry. FAO Train. Ser. No. 8. Rome, 1985; FAO. 87 pp. (also available at www.fao.org/DOCREP/X5085E/X5085E00.HTM).

- Freund F, Hörstgen-Schwark G, Holtz W. Seasonality of the reproductive cycle of female Heterobranchus longifilis in tropical pond culture. Aquatic Living Resources, 1995; 8: 297–302.

- Legendre M, Linhart O, Billard R. Spawning and management of gametes, fertilized eggs and embryos in Siluroidei. Aquatic Living Resources, 1996; 9: 59–80. [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis. 17th edition. AOAC, Washington, DC, 2003; USA.

- Khosravi A, Esmhosseini M, Jalili J, Khezri S. Optimization of ammonium removal from wastewater by natural zeolite using a central composite design approach. Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry, 2012; 74, 383-390.

- El-Shafai SA, El-Gohary FA, Nasr FA, Van der Steen NP, Gijzen HJ. Chronic ammonia toxicity to duckweed-fed tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). J. Aquac., 2004; 232: 117-127. [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed A-F M. Tilapia culture, CABI publishing, 2006; ISBN: 13-978-0-85199-014 9(alk. paper).

- Kwiatkowski M, Daniel A, Dariusz K, Krzysztof K. Influence of feeding natural and formulated diets on chosen rheophilic cyprinid larvae. Arch.Pol. Fish., 2008; 16: 383-396.

- Craig S, Helfrich L A. Understanding Fish Nutrition, Feeds and Feeding.Cooperative Extension Service, Virginia State University, 2002, USA.

- Safina MM, Christopher MA, Charles CN, Rodrick K. The Effect of Three Different Feed Types on Growth Performance and Survival of African Catfish Fry (Clarias gariepinus) Reared in a Hatchery. International Scholarly Research Network, 2012:6 doi:10.5402/2012/861364. [CrossRef]

- Oso JA, Edward JB, Ogunleye OA, Majolagbe FA. Growth Response and Feed Utilization of Clarias gariepinus Fingerlings Fed with Bambara Groundnut as protein source. Journal of Natural Sciences Research, 2013; ISSN 2225-0921, 3, 2013.

- Tarkegn A. Growth performance and survival rate of African catfish larvae Clarias gariepinus (Burchell 1822) fed on different types of live and formulated feeds. Master thesis, the University of Natural Resources and Life Science (BOKU), 2015; Vienna.

- Keremah RI, Beregha O. Effect of varying dietary protein levels on growth and nutrient utilization of African catfish Clarias gariepinus fingerlings. Journal of Experimental Biology and Agricultural Sciences, 2014; 2(1): 13-18.

- Corn’elio FHG, Cunha DA, Silveira J, Alexandre D, Silva C, Fracalossi DM. Dietary protein requirement of juvenile Cachara Catfish, Pseudoplatystoma reticulatum. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 2014; 45(1): 45-54, DOI: 10.1111/jwas.12090. [CrossRef]

- De Silva SS, Anderson TA. Fish nutrition in aquaculture. Chapman and Hall, 1995; London. 319 pp.

- Ali MZ, Jauncey K. Effect of feeding regime and dietary protein on growth and body composition of Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822). Indian Journal of Fisheries, 2004; 51:407-416.

- Goda AM, El-Haroun ER, Chowdhury MA. Effect of totally or partially replacing fish meal by alternative protein sources on growth of African catfish Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822) reared in concrete tanks. Aquaculture Research, 2007; 38(3): 279-287. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2007.01663. x. [CrossRef]

- Hecht T. Consideration of African aquaculture, World Aquaculture, 2000;1, 31: 12-19.

- Wetzel R.G. Limnology: Lake and river ecosystems. 3rd edition. Academic press. N.Y., 2001; 1006pp.

- Azaza MS, Dhraief MN, Kraiem M M. Effects of water temperature on growth and sex ratio of juvenile Nile tilapia O. niloticus (Linnaeus) reared in geothermal waters in southern Tunisia. J Therm. Biol., 2008;33: 98-105.

- Vladimirov VI. Razokaèestvennost’ ontogeneza kak odin iz faktorov dinamiki èislennosti stada ryb Gidrobiol. Journal, 1970; 6: 14-27.

- Dabrowski K. Critical period in the life of newly-hatched fish. An attempt to determine the minimum food requirements in terms of energy Wiad. Ekol., 1975; 21: 277-293.

- Kujawa R, Kucharczyk D, Mamcarz A. Rearing asp (Aspius aspius L.) and ide (Leuciscus idus L.) hatch under controlled conditions on natural and granulated feed in Rheophilic cyprinid fish (Eds) H. Jakucewicz, R. Wojda, Wyd. PZW, Warszawa: 1998; 71-78.

- Sawhney S, Gandotra R. Effects of photoperiod on growth feed conversion, efficiency and survival of fry and fingerlings of Mahseer, Tor putitora. Israel Journal of Aquaculture, 2010; 62(4): 266-271.

- Tan Q, Xie S, Xhu X, Lei W, Yang Y. Effect of carbohydrate to lipid ratios on growth and feed efficiency in Chinese long snout catfish (Leiocasis longirostris). Journal of Applied Ichthyology, 2007; 23(5): 605-610. DOI: 10.1111/j.1439-0426.2007.00846. x. [CrossRef]

- Hjort J. Fluctuations in the great fisheries of northern Europe, Rapp P-v Réun Cons Int Explor Mer, 1914; 20: 1–228.

| Ingredients | Experimental feeds | ||

| CP 50 % | CP 45 % | CP 40 % | |

| Inclusions % | Inclusions % | Inclusions % | |

| blood meal | 36.9 | 31.79 | 26.66 |

| Fish meal | 28.2 | 25.15 | 22.06 |

| Soybean meal | 18.5 | 17.68 | 16.88 |

| maize (BH660) flour | 3.7 | 5.61 | 8.52 |

| wheat (durum) flour | 2.6 | 5.65 | 8.86 |

| Barley flour | 2.7 | 6.61 | 9.52 |

| Soy oil | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| premix | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| methionine (g/kg) | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| lysine(g/kg) | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Proximate composition (g 100 g-1) | |||

| DM | 92.4 | 91.6 | 86.2 |

| Energy Kcal/g | 468.2 | 477.6 | 559.5 |

| CP | 50.0 | 45.0 | 40.0 |

| Lipid | 11.5 | 11.3 | 7.9 |

| NFE | 13.0 | 18.7 | 24.4 |

| CF | 1.4 | 1.6 | 8.8 |

| Ash | 4.9 | 4.7 | 9.4 |

| Amino acids | CP 50% |

CP 45% | CP 40% | Recommended amount |

| Inclusion (% of dietary protein) | ||||

| Arginine | 4.3 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 4.3 |

| Histidine | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.5 |

| Iso leucine | 2.5 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 2.6 |

| Leucine | 3.5 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 3.5 |

| Lysine | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 5.1 |

| Methionine | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 2.3 |

| Phenylalanine | 4.9 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 5.0 |

| Threonine | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 2.0 |

| Tryptophan | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Valine | 2.9 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 3.0 |

| Feeding procedure | ||||

| Day | CP 50% | CP 45% | CP 40% | Amount of feed |

| ~7 | Yolk sac | Yolk sac | Yolk sac | - |

| 7-14 | live feed | live feed | live feed | 15 individuals /larvae |

| 14 - 21 | 80% live + 20% dry feed |

80% live + 20% dry feed |

80% live + 20% dry feed | 30 ind/larvae +20 % BW |

| 21-28 | 20% live + 80% dry feed |

20% live + 80% dry feed |

20% live + 80% dry feed | 40 ind/larvae + 15 % BW |

| 28-70 | 100% dry feed | 100% dry feed | 100% dry feed | 10 % BW, |

| Experimental feeds | |||

| Parameters | CP 50 % | CP 45 % | CP 40 % |

| DO (mgL−1) | 5.30 ± 0.37 | 5.26 ± 0.57 | 5.37 ± 0.27 |

| Temperature (oC) | 24.55 ±3.34 | 24.32 ± 3.35 | 24.24 ± 3.34 |

| pH | 7.30 ± 0.02 | 7.26 ± 0.05 | 7.31 ± 0.08 |

| TAN (mgL−1) | 0.011 ± 0.008 | 0.012 ± 0.004 | 0.013 ± 0.003 |

| Treatments | |||

| parameters | CP 50 % | CP 45 % | CP 40 % |

| Mean initial weight (gm) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Mean final weight (gm) | 11.76 ± 1.52a | 11.37 ± 1.47a | 6.94 ± 1.34b |

| Weight gain (gm fish-1) | 11.73 ± 1.52a | 11.35 ± 1.47a | 5.84 ± 1.34b |

| Average daily gain (gm fish-1 day-1) | 0.17a | 0.16a | 0.08b |

| Specific growth rate (%) | 8.79 | 8.74 | 7.79 |

| Feed conversion ratio | 2.43a | 2.46a | 3.14b |

| Survival rate (%) | 81.5a | 80a | 66.5b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).