1. Introduction

Aquaculture is crucial for food supplies and is attracting attention as a source of protein and nutrition. Furthermore, as it affects the economy and prevents overharvesting, which is considered by some to be a major threat to marine resources, it can also play a role in mitigating poverty and is expected to contribute to multiple Sustainable Developing Goles (SDGs) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, aquaculture still faces challenges, such as poor feed efficiency, high cost, and environmental problems [

2,

4] There is an urgent need to improve aquaculture using fish meal and oil, called “fish in fish out.” In other words, the effective use of terrestrial plants and other surpluses as feed must be optimized [

5,

6]. The feed conversion ratio (FCR) is an index of feed efficiency that indicates the amount of meat produced for a given unit of feed. Improvements in feed are always required to obtain more meat. In particular, in aquaculture, the FCR varies greatly depending on the type of farmed fish. However, fish species that are less human-palatable, nutritional, or easy to eat have little value. Therefore, the FCR must be optimized for fish species to be worth farming.

Plectropomus leopardus (leopard coral grouper) belongs to the order perciformes and is a carnivorous coral reef fish that inhabits the temperate to tropical regions of the Western Pacific and Indian Oceans, from southern Japan to Australia, and changes sex by becoming male over time [

7,

8,

9].

P. leopardus is a commercially important fish in Asia, particularly in Hong Kong, traded at a high price both alive and chilled for food use. Furthermore, the total capture of groupers is reported to be increasing yearly, and demand is also increasing [

10]. Carnivorous fish, including

P. leopardus, eat fish and crustaceans, while herbivorous fish eat aquatic plants and algae, and fish that eat both are omnivorous. These differences in dietary habits divide the available nutritional components, particularly the ability to utilize carbohydrates including glucose [

11].

Carbohydrates, including starch, store energy in terrestrial plants and can be easily and cost-effectively obtained due to their abundance. Additionally, reusing nitrogen and phosphorus while the plants are growing is possible in collaboration with microorganisms through composting and waste recycling, thereby affecting their environment [

12]. Moreover, substituting carbohydrates with fish meal and oil can help preserve marine resources [

2,

13]. In aquaculture, carbohydrates are primarily used as glue in baits containing fish meat and oil, but their uses vary among fish species. When farming carnivorous fish, carbohydrates such as starch are used as binders in artificial feed, with more emphasis on developing substitute proteins and lipids [

11,

14]. However, carbohydrates provide energy and help prevent proteolysis, indirectly contributing to increased protein [

15,

16]. In addition, carbohydrates have the advantage that stable carbon isotopes (13C) can be obtained relatively easily and experimentally tracked, and direct observations are feasible while tracking metabolic pathways [

17,

18].

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy uses magnetic fields to help understand the structure and motion of molecules. In recent years, mixtures such as muscle, feces, water, and soil have been measured, and multivariate analyses have been performed [

19,

20,

21,

22]. With recent computational advances, machine learning and deep learning have become possible for analyzing big data. Additionally, by combining various analysis techniques from other fields, it has become possible to narrow down variables and extract important factors. Furthermore, to estimate correlations and causal relationships, the use of numerical information is no longer necessary, and relationships with environmental factors can be extracted[

23,

24,

25]. The acquisition of large amounts of data and improvements in analysis technology have made it possible to infer causal relationships in a data-driven manner from observed facts, without examining multiple hypothesis-driven experimental conditions [

26,

27].

In this study, to evaluate the function of feed components on growth during breeding, we farmed a large population of P. leopardus in a single tank, and by sampling high-growth (Large) and low-growth (Small) individuals over time, we clarified the components in muscles important for growth in this species. In the farming protocol, we adopted a breeding method that allows P. leopardus to consume the appropriate type of feed according to its body length, by providing sufficient nutrients in fortified feed suitable for each stage from larva to adult, then gradually reducing the type of feed based to the day after hatching. Finally, the fish were raised only with artificial bait.

The feed given at each stage and the sampled fish tissue were measured using NMR spectroscopy to understand their characteristics. Using machine learning methods, components in the muscles that characterize the size of P. leopardus were identified. Several characteristic factors were deduced, but there were two primary components, namely, taurine, one of the fortified nutrients in feed, and glycine, a typical amino acid, which was not fortified and contributes in collagen formation. Furthermore, to identify substances in muscle important for size-related factors, we used machine learning methods and a Bayesian network for probabilistic causal inference. Surprisingly, our study indicated that even in P. leopardus, which is a carnivorous fish, providing sufficient glucose, a carbohydrate, and some small molecules are beneficial in the early stages of growth. Based on the identification of these important variables, we administered bait containing carbohydrates (starch) composed of 13C, a stable isotope, and attempted to visualize its metabolism. We found that starch can be used as a carbon source for glycine and other low-molecular-weight compounds. These results suggest a new way to improve the efficiency of aquaculture feed, which also contributes to the SDGs, by adjusting the timing of feeding carbohydrates such as starch, which are abundantly obtained from terrestrial plants, and some small molecules. Our results suggest that an improvement in aquaculture strategy is possible.

2. Results

2.1. Differences in Feed Components Based on NMR Spectroscopy Data

We farmed P. leopardus in a single tank and fed them three types of food, brachionus, artemia, and artificial bait. Based on the facility’s experience, the food type ingested depends on the physical size of the oral cavity. Therefore, we assumed that the fish ate brachionus in the early stage of farming and artemia in the next stage. We measured the differences in the components of these feed types using NMR spectroscopy and calculated Euclidean distance i and the similarity of individual spectra (

Figure 1). In

Figure 1a, the calculated distance information is shown on a Nonmetric Multidimensional Scaling map, indicating that each feed had different components. In

Figure 1b, scaling and clustering were performed for each feed component to show the similarity between each feed type, indicating that each contained characteristic components.

2.2. Changes in Muscle Components during Growth Stages and Comparing Farmed and Wild-Captured Adult Fish

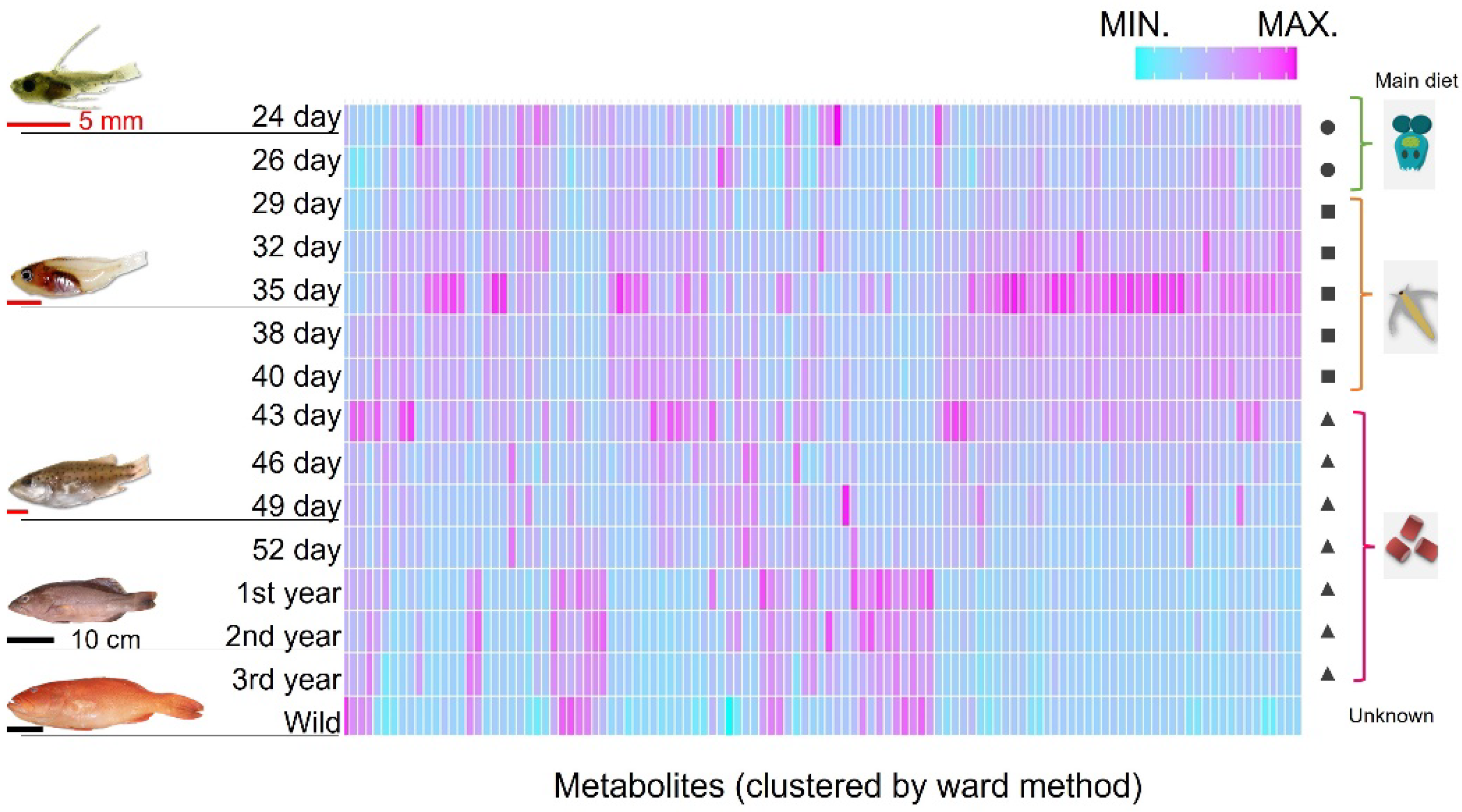

Next, we clustered the muscular components and visualized them in a heatmap to clarify how these components changed during P. leopardus growth. We also investigated whether these components were different from those in captured fish from the sea (

Figure 2). The brachionus were removed from the tank after 26th day of hatching, and the artemia were removed after the 43rd day. Afterward, the P. leopardus were farmed only with artificial bait. Conversely, the diet of wild P. leopardus was unknown. Although the cells of heatmap were clustered by muscle components, the components differed by growth stage and the main diet. Additionally, the 1–3-year-old adult farmed fish and wild-captured fish clustered closer together than the dispersion observed between juvenile clusters.

2.3. Extraction of Important Factors Determining Body Size in the Early Stages of Farming Using Machine Learning Methods

Individual size variation emerged early. At the final sampling point, 52 days after hatching, mean length differed by 61% and mean weight differed by 350% between the high-growth and low-growth groups. Under our farming conditions, each feed type had characteristic components, and the main feed also changed over time. Although the muscle components changed at each stage, we used machine learning methods to explore whether there were universally important factors for body size when classifying the high-growth and low-growth groups. We used a random forest approach, which is a machine learning method using decision trees for classification. Since the Gini impurity, which is an index of importance calculated by the random forest, changes slightly with each calculation, we averaged 20 calculations (

Figure 3). The figure shows components with an average Gini impurity of >1. Although many components had a value <3, there were two components that had a value close to 4: glycine and taurine.

2.4. Probabilistic Causal Inference Using Components That Explain Important Factors of Body Size Classification by Bayesian Networks

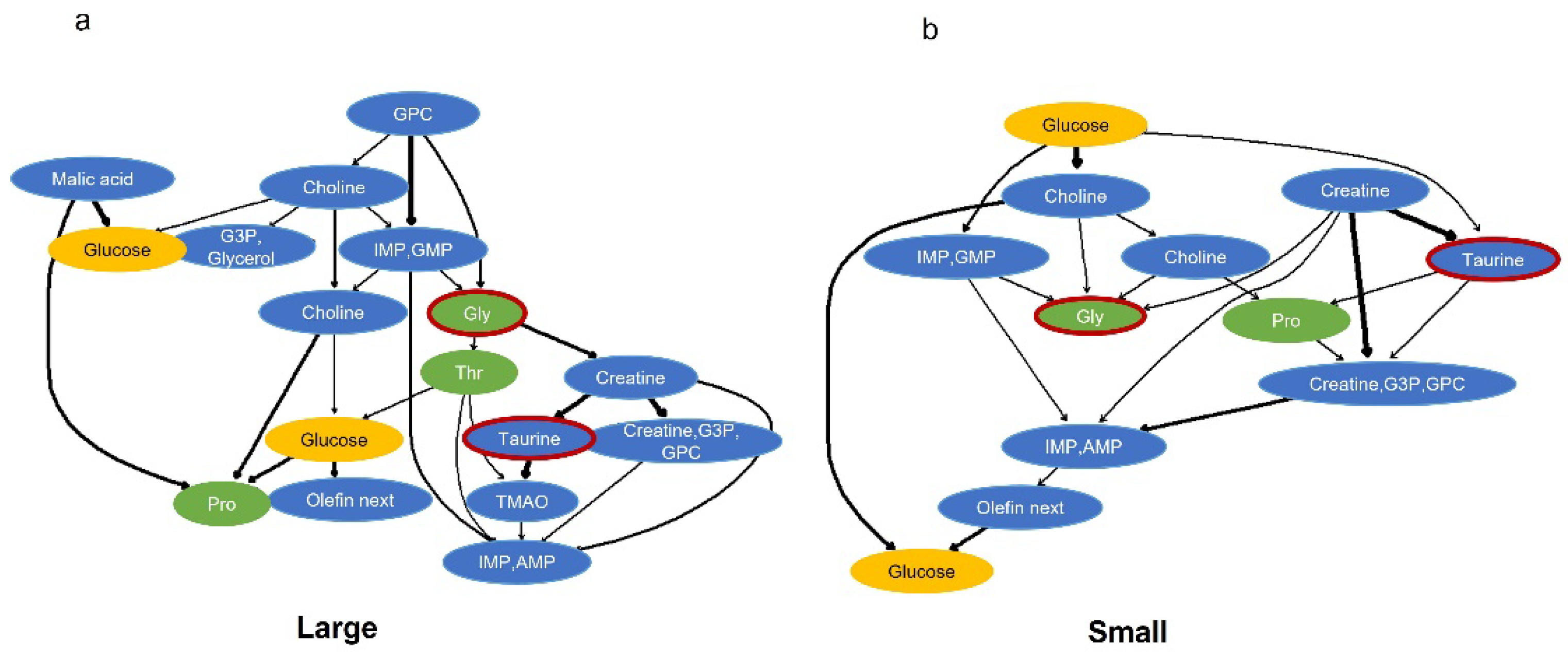

Subsequently, we performed causal inference using Bayesian network analysis with the identified variables glycine and taurine (

Figure 4). The analyses were conducted separately for the top 10% (Large) and bottom 10% (Small) of fish samples. The reason for analyzing each size group separately is that Bayesian networks are directed acyclic graphs, and if different size group were analyzed at the same time, the relationship between groups might become noise, leading to confusion. The results showed that both networks included glucose and the amino acids proline and threonine.

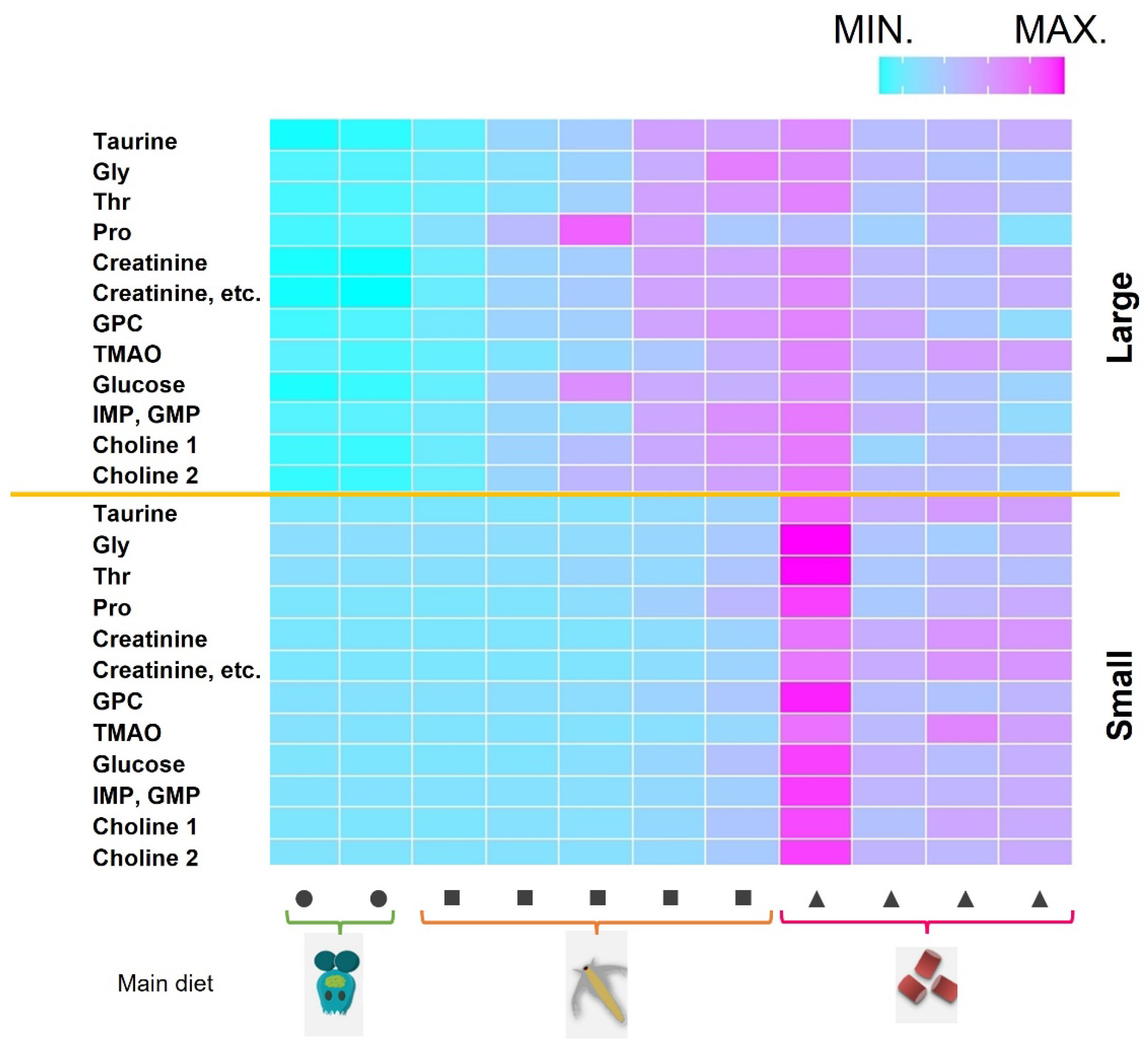

2.5. Analysis of Time-Series Changes in Important Factors for Body Size

We analyzed time-series scaled metabolic fluctuations to determine when during early farming important factors for growth are most effective (

Figure 5). The heatmap was depicted with important elements for growth, such as taurine, glycine, threonine, proline, creatinine, glycerylphosphorylcholine (GPC), trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), glucose, inosine or guanosine monophosphate (IMP/GMP), and choline. These components were used in the random forest and Bayesian network mentioned above, the Small group had the highest value of all heatmap elements on the first day after switching to solely artificial bait, whereas the corresponding values of the Large group gradually increased after brachionus was removed. The highest amounts of proline and glucose were recorded when artemia was the main diet. Additionally, many components showed peak values at 1–2 sampling points before switching to artificial bait only, and these values were maintained. We also saw that there were no significant changes after the second sampling point following the switch to artificial bait only.

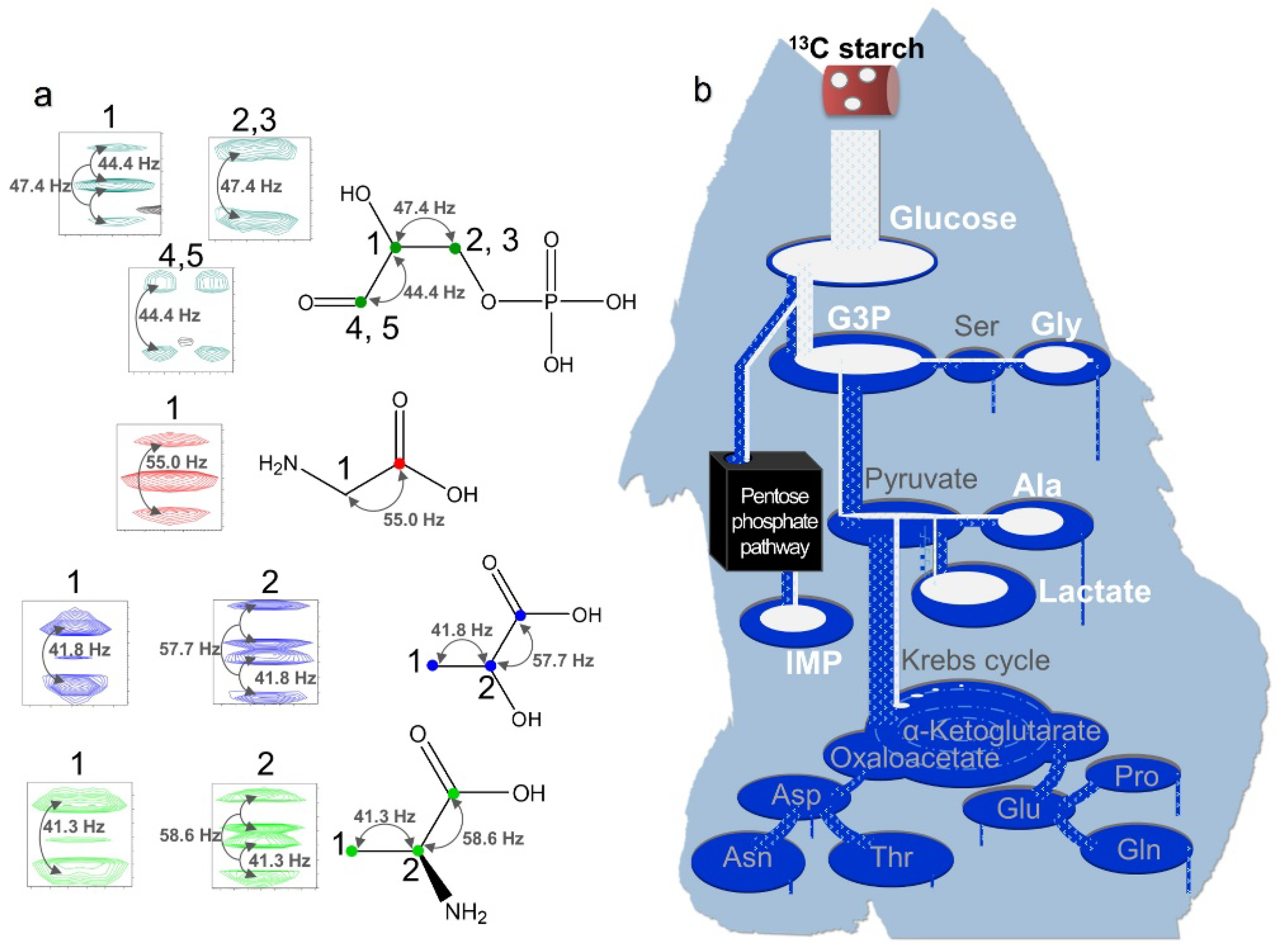

2.6. Monitoring Starch Metabolism with 13C Labeling

The metabolism +C-labeled algal starch incorporated into P. leopardus muscle tissue with long-term (6 months) feeding was observed using heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectroscopy. The metabolites from

13C-labeled algal starch exhibited strong

13C–

13C couplings and were easily distinguished from the other metabolites (Figs. 6 and 7). Our results confirmed that feed including

13C-labeled algal starch was digested into glucose and incorporated into muscle tissue (

Figure 6). Surprisingly, some carbon in the fed starch was directly metabolized into glycine, while some was metabolized into inosinic acid monophosphate, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, alanine, and lactate.

3. Discussion

To clarify the relationship between the influence of feed on fish meat in aquaculture, we examined the components of feed and fish tissue over time (Figs. 1 and 2). In adult fish, although wild-caught fish and those that were farmed had distinctly different diets, the constituent components of their muscles were more similar than those during the changes occurring during early growth. Adult wild fish are believed to prey mainly on other fish [

28], whereas the main ingredient of our artificial bait was fish meal. Conversely, some values were observed to have characteristic differences between wild and farmed fish. These included glucose (wild/farmed = 0.466), glycine (= 0.788), and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) (= 5.472). Based on the stable isotope study (

Figure 6), some of the glucose and glycine may be derived from carbohydrates such as starch. Additionally, seawater fish contain more TMAO than freshwater fish, and the compound has reported associations with carnivorous fish that mainly eat other fish [

21,

29,

30,

31]. In fact, the artificial bait we used contained up to 15% carbohydrates and 60% animal-derived ingredients, including fishmeal and shrimp meal. However, wild-caught fish may consume little carbohydrate. Compared to the stability of the constituent components of adult fish, the components extracted from the muscle of farmed fish may be significantly influenced by the feed type and timing of feeding.

In the early stages of farming, the muscle components differed depending on the developmental stage and the influence of diet, but at every sampling point, there were individuals that grew quickly and slowly. We investigated whether there were factors that universally influenced growth variation by random forest classification (

Figure 3). The results clearly showed that two constituent factors were important, glycine and taurine. Glycine is present in large amounts in collagen, and it has been reported that, together with proline, glycine is important for collagen synthesis [

32]. Proline also contributed to the classification of high-growth and low-growth fish, although to a lesser extent than glycine. Additionally, since glycine is involved in the osmoregulation response [

33], and growth is affected by salt concentration [

34], it may be possible to increase the size of fish by adjusting the salt concentration in aquaculture. Taurine is reported to be a critical nutrient for fish maturation, including for

P. leopardus [

35,

36,

37]. Therefore, it is reasonable that glycine and taurine were identified as important factors separating the high-growth and low-growth groups using the random forest approach.

We set glycine and taurine as objective variables and performed random forest regression to identify components or metabolic networks related to glycine and taurine within each group. Furthermore, by conducting Bayesian network analysis using the extracted constituent factors, we estimated components that influence glycine and taurine (

Figure 4). Bayesian network analysis suggested a relationship between glycine, threonine, and proline in the Large group, and a relationship between taurine and creatine in both groups. Furthermore, since two signals derived from glucose were embedded in the network, implying that the factors belonging to this module were equivalent to glucose, we inferred that the module was closely related to glucose utilization. To investigate at which stage of early farming these factors were important, we created a heatmap in which each component was scaled over time (

Figure 5). In the Small group, there was little fluctuation after reaching a peak the day we switched to artificial bait. Conversely, in the Large group, proline and glucose reached peaks when artemia was the main diet, and other components tended to be higher during that period. Although differences in muscle composition were not clear even after switching to artificial bait, there were differences in body size. Thus, intake of growth-related components such as glucose and proline when artemia was the main diet impacted later growth. The third sampling when artemia was the main diet was 35 days after hatching, and it was suggested that the transfer of glucose and required amino acids to the muscles before then might influence body size 43 days after hatching, when artificial bait was switched.

Finally, to answer the question of how the carnivorous fish

P. leopardus utilize glucose, we performed an experiment using artificial bait containing

13C stable isotopes incorporated into starch (

Figure 6). The results revealed that after the starch was degraded, it was absorbed into glucose, and some of the carbon originating from the starch was directly metabolized into glycine. Carnivorous fish use glucose as an energy source, but the availability of glucose is low, and high doses lead to hyperglycemia [

11,

14,

38,

39]. However, our experiment using a stable carbon isotope showed that glucose was directly metabolized into amino acids that constitute collagen. However, no isotopes were found for proline or threonine, suggesting that some amino acids may be required when carbohydrates are ingested.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics Statement

All experiments were conducted according to the principles and procedures approved by the guidelines for the care and use of live fish at the National Research Institute of Fisheries Science and RIKEN. As anesthetic chemicals such as 2-phenoxyethanol may influence metabolic profiling, all fish in our study were rapidly subjected to ice tightening—similar to other fishery and aquaculture products—during sampling. For wild fish, no specific permission was required at any sampling locations, as fishing in public places is legal in Japan.

4.2. Fish Samples

To control the feed and environment, nearly all aquaculture samples were cultured at the Research Center for Subtropical Fisheries, Fishery Research and Education Organization. Brachionus, artemia, and artificial feed were used as feed. The artificial feed contained protein (>46.0%), fat (>10.0%), carbohydrates (<15.0%), fiber (<2.5%), calcium (>2.0%), and phosphorus (>1.0%) (Himezakura; Higashimaru, Kagoshima, Japan). The artificial bait comprised 60% animal-derived materials. Brachionus and artemia were cultured at the same institution as P. leopardus. Until 52 days of age, the body length of 96 individuals was measured every 3 days. The five largest individuals were considered the high-growth group (Large) and the five smallest individuals were the poor-growth group (Small). Wild samples were collected off the coast of Okinawa, Japan.

Three 18 cm, 1-year-old P. leopardus individuals were cultured at RIKEN (Yokohama, Japan). To evaluate changes in dietary metabolism, carbon isotope labeling and fecal measurements were performed. For this experiment, feed was mixed with 20% w/w 13C-labeled algal starch (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, Massachusetts, USA) and 80% w/w artificial feed (Himezakura). Feed was administered to P. leopardus for 6 months.

4.3. NMR Spectroscopy

A total of 10 mg dried, powdered muscle tissue (or the total amount of muscle tissue if <10 mg) was extracted using 600 µL standardized potassium phosphate NMR buffer in deuterium oxide (2H > 90%) with 2, 2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate (DSS) at 60ºC for 15 min and shaken for 15 min. After centrifugation at 25ºC for 5 min, the extracted supernatant was transferred into a 5-mm NMR tube for NMR measurements.

All 2D-Jres NMR spectra (magnitude-mode, gradient-enhanced, J-resolved with presaturation) were measured at 298 K on a Bruker Avance II DRU 700 NMR spectrometer. The measurement parameters of the 2D-Jres were as follows: the time domain data size was 16,384 for F2 (

1H) and 32 for F1 (J-coupling), the spectral width was 16 ppm for F2 and 50 Hz for F1, and the number of scans was 32. Following previous reports [

40,

41,

42], 2D-Jres spectroscopy was performed in a tilted manner, symmetrical to the horizontal axis through the F center. Skyline or sum-projection was performed as indicated. Additionally, Jres projections were referenced and baseline-corrected. The obtained spectra were processed with TopSpin software (Bruker BioSpin, Rheinstetten, Germany) with a sine-bell window function, zero fillings to 128 points, tilt correction, and symmetrization. We selected the 2D-Jres NMR projection due to a reduction in peak overlap as well as for its high sensitivity, which aids metabolite identification and data mining in spectral areas [

40].

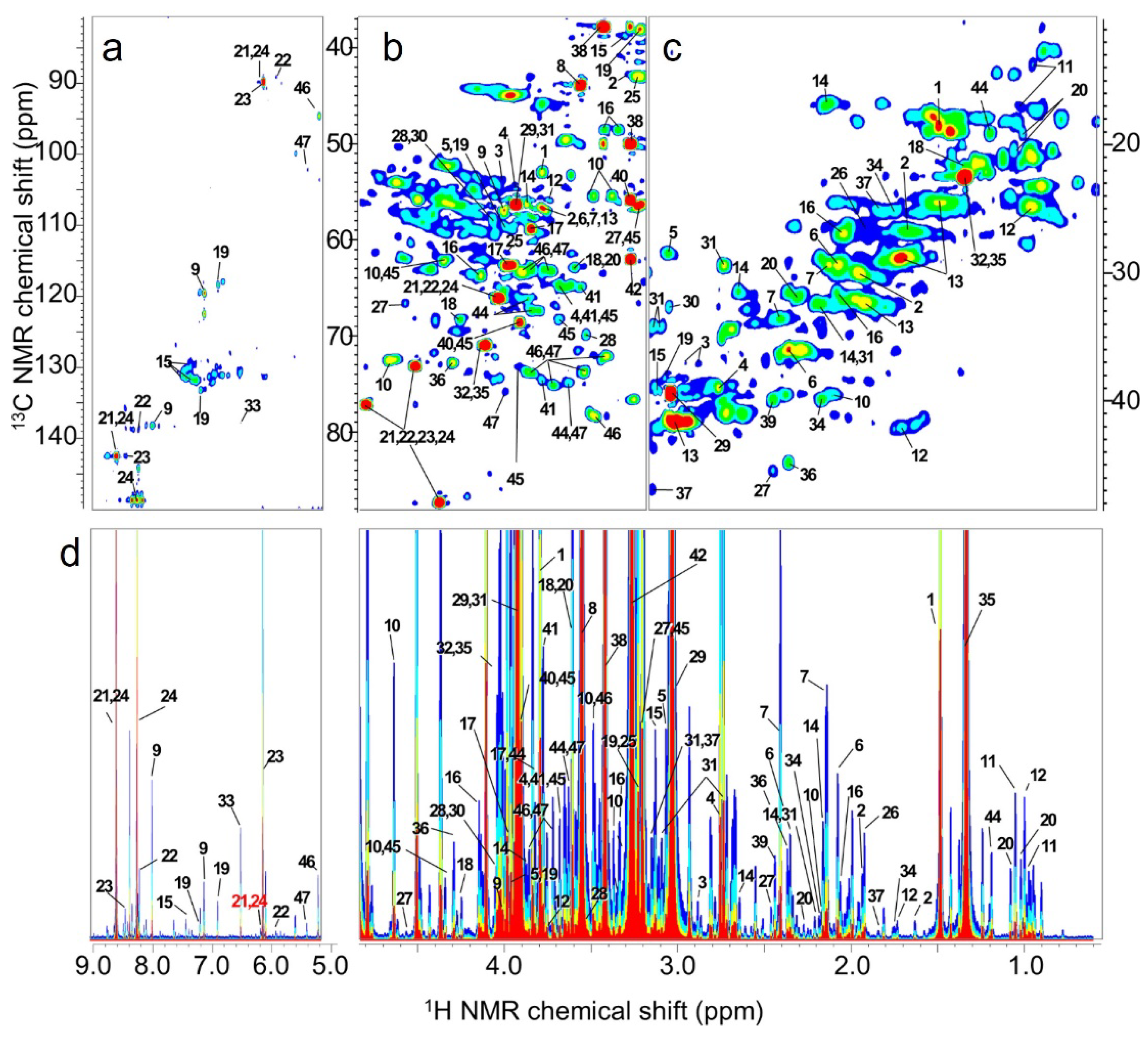

To assign the chemical shifts of metabolites, a 1-year-old fish was used and analyzed with

1H–

13C HSQC using 320 scans with 256 data points for F1 (

13C) and 1,024 data points for F2 (

1H) with spectral widths of 150 ppm for F1 and 14 ppm for F2. The HSQC spectra were processed using TopSpin software (Bruker) and annotated using SpinAssign [

43]. For the

13C-labeling experiment, one fish cultured by labeled feeding underwent analysis with HSQC using 48 scans with 1,300 data points for F1 (

13C) and 1,024 data points for F2 (

1H) with spectral widths of 40 ppm for F1 and 14 ppm for F2. HSQC spectra were similarly processed and annotated. These extraction methods and parameters were based on previous studies [

44,

45,

46].

4.4. Annotation and Normalization of NMR Spectra

Based on the position of the H–C correlation in the 1H–13C HSQC spectrum and the J-coupling constants from 2D-Jres projection, 47 substances were detected in the water-soluble fraction of the metabolites from P. leopardus muscle tissue (Figure S1). These substances were assigned to distinguishable peaks in the 2D-Jres projection spectrum. In subsequent analyses, intensity was taken as a composition ratio where necessary.

4.5. Analytics and Statistics

The 2D-Jres spectra were processed into a data matrix using a peak-picking software based on the region of interest (ROI) using rNMR [

47]. ROIs comprised information related to peak intensity and chemical shifts indicative of the region. ROIs that could not be annotated were excluded from the analyses. All calculations were performed using R software version 4.0.2 (

http://www.R-project.org/) [

48,

49]. Additionally, we used the following packages: “vegan” for Nonmetric Multidimensional Scaling analysis, “bnlearn” for Bayesian network analysis, and “randomForest” for random forest analysis.

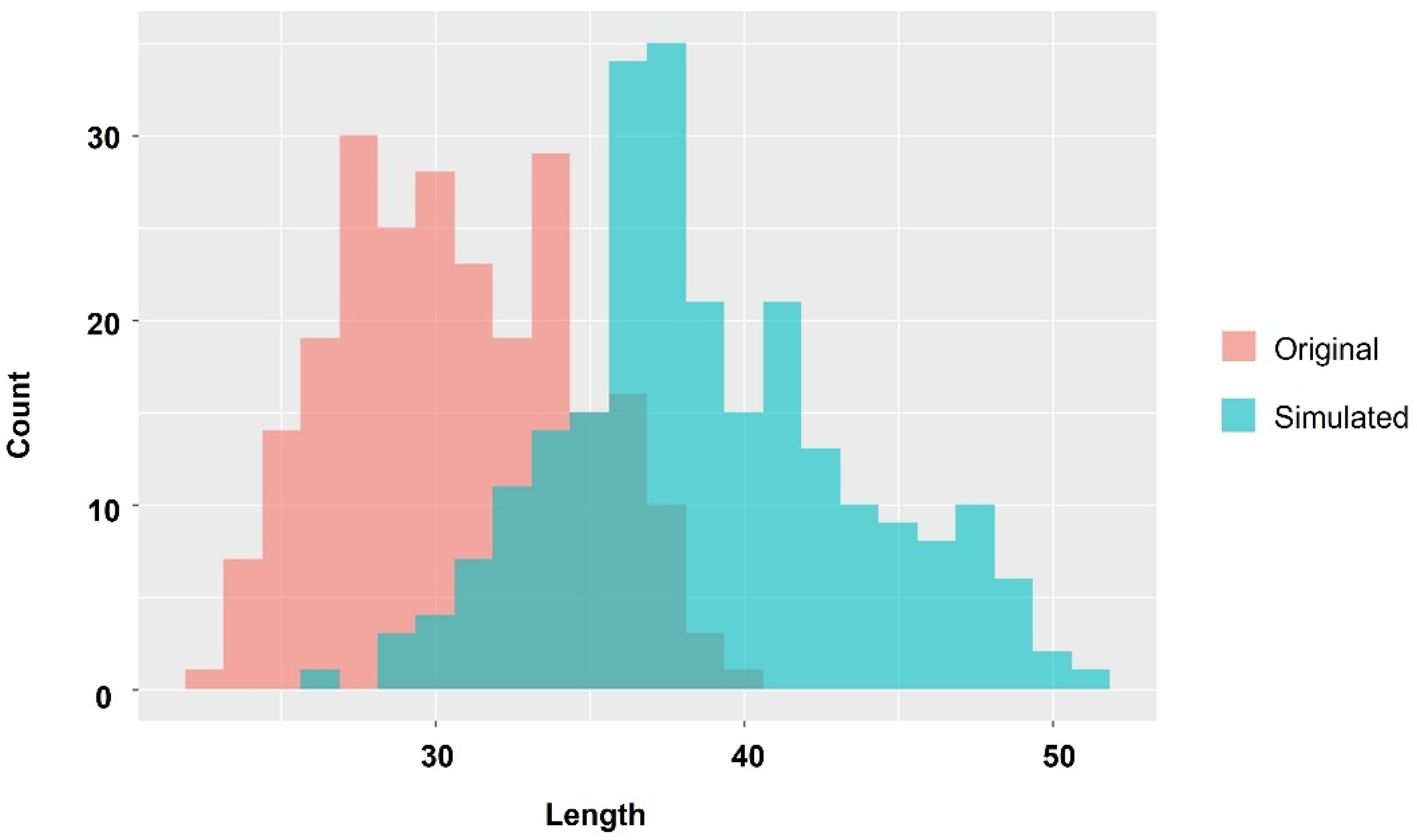

5. Conclusions

In this study, we aimed to improve the FCR of farmed fish to improve food security. To clarify factors causing variation in body size during aquaculture, we farmed

P. leopardus in a single tank and analyzed the components of their diets and muscle components measured by NMR spectroscopy and

13C stable isotope analysis over time. The results revealed that

P. leopardus, a carnivorous fish, could utilize carbohydrates and metabolize them into glycine, a characteristic component in the muscle of high-growth fish. We also identified amino acids that are considered essential for their effective use. At 52 days after hatching, body length of the Large group was approximately 60% larger than Small group and on approximately 350% heavier than the Small group. Based on these results, we conducted a simple simulation in which the Small group became average, and the average group was slightly larger. This simple simulation estimated an improvement of about 25% in body length and about 100% in FCR (

Figure 8).

However, previous reports, including this study, have shown that other issues remain when farming saltwater fish, such as osmotic pressure and temperature. Therefore, to avoid a food crisis, improvement of the FCR in aquaculture must be considered not only when using starch from terrestrial plants, but also in improving the aquaculture environment. Additionally, by applying our methods in other fields, the efficiency of agriculture and livestock farming can be improved.

Author Contributions

Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review and Editing, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, H. S.; Writing – Review and Editing, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, T.A.; Writing – Review and Editing, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, K.S.; Writing – Review and Editing, Investigation, Validation, Resource, M.K.; Writing – Review and Editing, Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Project Administration, Supervision, J.K.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Tomoko Shimizu, Yachiyo Ootaka, and Shiori Fujinuma (RIKEN) for technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

References

- Stead, S.M. Using systems thinking and open innovation to strengthen aquaculture policy for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. J Fish Biol 2019, 94, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, A. Thought of alternate aquafeed: conundrum in aquaculture sustainability? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Zoological Society; 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, A.J.; Elliott, V.; Phang, S.C.; Claussen, J.E.; Harrison, I.; Murchie, K.J.; Steel, E.A.; Stokes, G.L. Inland fish and fisheries integral to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat Sustain 2020, 3, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R.L.; Hardy, R.W.; Buschmann, A.H.; Bush, S.R.; Cao, L.; Klinger, D.H.; Little, D.C.; Lubchenco, J.; Shumway, S.E.; Troell, M. A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature 2021, 591, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, R.A.; Nowara, G.B.; Hartmann, K.; Green, B.S.; Tracey, S.R.; Carter, C.G. Marine foods sourced from farther as their use of global ocean primary production increases. Nat Commun 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, B.; Malcorps, W.; Tlusty, M.F.; Eltholth, M.M.; Auchterlonie, N.A.; Little, D.C.; Harmsen, R.; Newton, R.W.; Davies, S.J. Fish as feed: using economic allocation to quantify the fish in: fish out ratio of major fed aquaculture species. Aquaculture 2020, 528, 735474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoilys, M.A.; Squire, L.C. Preliminary observations on the spawning behavior of coral trout, Plectropomus leopardus (Pisces: Serranidae), on the Great Barrier Reef. J Mar Sci 1994, 54, 332–342. [Google Scholar]

- Mekuchi, M.; Asakura, T.; Sakata, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Teruya, K.; Kikuchi, J. Intestinal microbiota composition is altered according to nutritional biorhythms in the leopard coral grouper (Plectropomus leopardus). PLoS One 2018, 13, e0197256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker Jr, J.W. Grouper aquaculture. Southern Regional Aquaculture Center Publication 1999, 721, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sadovy de Mitcheson, Y.; Craig, M.T.; Bertoncini, A.A.; Carpenter, K.E.; Cheung, W.W.; Choat, J.H.; Cornish, A.S.; Fennessy, S.T.; Ferreira, B.P.; Heemstra, P.C. Fishing groupers towards extinction: a global assessment of threats and extinction risks in a billion dollar fishery. Fish Fish 2013, 14, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalam, B.S.; Panserat, S. Carbohydrates in fish nutrition. International Aquafeed 2016, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, H.; Shigeta, K.; Suda, W.; Ichihashi, Y.; Nihei, N.; Matsuura, M.; Tsuboi, A.; Tominaga, N.; Aono, M.; Sato, M. An agroecological structure model of compost—soil—plant interactions for sustainable organic farming. ISME Commun 2023, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Zanten, H.; Simon, W.; Van Selm, B.; Wacker, J.; Maindl, T.; Frehner, A.; Hijbeek, R.; Van Ittersum, M.; Herrero, M. Circularity in Europe strengthens the sustainability of the global food system. Nat Food 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Polakof, S.; Panserat, S.; Soengas, J.L.; Moon, T.W. Glucose metabolism in fish: a review. J Comp Physiol B 2012, 182, 1015–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.P.; Halver, J.E. Protein and amino acid requirements of fishes. Annu Rev Nutr 1986, 6, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, S.R.; Helfrich, L.A.; Kuhn, D.; Schwarz, M.H. Understanding fish nutrition, feeds, and feeding. 2017.

- Roscher, A.; Kruger, N.J.; Ratcliffe, R.G. Strategies for metabolic flux analysis in plants using isotope labelling. J Biotechnol 2000, 77, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petropoulou, K.; Salt, L.J.; Edwards, C.H.; Warren, F.J.; Garcia-Perez, I.; Chambers, E.S.; Alshaalan, R.; Khatib, M.; Perez-Moral, N.; Cross, K.L. A natural mutation in Pisum sativum L.(pea) alters starch assembly and improves glucose homeostasis in humans. Nat Food 2020, 1, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugase, K.; Dyson, H.J.; Wright, P.E. Mechanism of coupled folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Nature 2007, 447, 1021–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, K.; Miyamoto, H.; Matsuura, M.; Ishii, C.; Tsuboi, A.; Tsuji, N.; Nakaguma, T.; Nakanishi, Y.; Kato, T.; Suda, W.; et al. Noninvasive fecal metabolic profiling for the evaluation of characteristics of thermostable lactic acid bacteria, Weizmannia coagulans SANK70258, for broiler chickens. J Biosci Bioeng 2022, 134, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shima, H.; Sato, Y.; Sakata, K.; Asakura, T.; Kikuchi, J. Identifying a correlation among qualitative non-numeric parameters in natural fish microbe dataset using machine learning. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, H.; Asano, F.; Ishizawa, K.; Suda, W.; Miyamoto, H.; Tsuji, N.; Matsuura, M.; Tsuboi, A.; Ishii, C.; Nakaguma, T.; et al. A potential network structure of symbiotic bacteria involved in carbon and nitrogen metabolism of wood-utilizing insect larvae. Sci Total Environ 2022, 836, 155520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, H.; Masuda, S.; Date, Y.; Shino, A.; Tsuboi, Y.; Kajikawa, M.; Inoue, Y.; Kanamoto, T.; Kikuchi, J. Exploring the impact of food on the gut ecosystem based on the combination of machine learning and network visualization. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shima, H.; Murata, I.; Feifei, W.; Sakata, K.; Yokoyama, D.; Kikuchi, J. Identification of salmoniformes aquaculture conditions to increase creatine and anserine levels using multiomics dataset and nonnumerical information. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiokawa, Y.; Misawa, T.; Date, Y.; Kikuchi, J. Application of market basket analysis for the visualization of transaction data based on human lifestyle and spectroscopic measurements. Anal Chem 2016, 88, 2714–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Prabhat, f. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 2019, 566, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, P.; Parkkinen, J.A.; Willighagen, E.L.; Ceder, R.; Wennerberg, K.; Kaski, S.; Grafström, R.C. A transcriptomics data-driven gene space accurately predicts liver cytopathology and drug-induced liver injury. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 15932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St John, J. Ontogenetic changes in the diet of the coral reef grouper Plectropomus leopardus (Serranidae): patterns in taxa, size and habitat of prey. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 1999, 180, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibel, B.A.; Walsh, P.J. Trimethylamine oxide accumulation in marine animals: relationship to acylglycerol storagej. J Exp Biol 2002, 205, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, G.; Wibisono, R.; Hedderley, D.; Fletcher, G. Trimethylamine oxide content and spoilage potential of New Zealand commercial fish species. N Z J Mar Freshw Res 2017, 51, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Gibbons, H.; Rundle, M.; Frost, G.; McNulty, B.A.; Nugent, A.P.; Walton, J.; Flynn, A.; Brennan, L. The relationship between fish intake and urinary trimethylamine-N-oxide. Mol Nutr Food Res 2020, 64, 1900799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, G. Roles of dietary glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline in collagen synthesis and animal growth. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamushaki, V.A.J.; Kasumyan, A.O.; Abedian, A.; Abtahi, B. Behavioural responses of the Persian sturgeon (Acipenser persicus) juveniles to free amino acid solutions. Mar Freshw Behav Phy 2007, 40, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiz-Carrión, R.; Sangiao-Alvarellos, S.; Guzmán, J.M.; del Río, M.P.M.; Soengas, J.L.; Mancera, J.M. Growth performance of gilthead sea bream Sparus aurata in different osmotic conditions: implications for osmoregulation and energy metabolism. Aquaculture 2005, 250, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salze, G.P.; Davis, D.A. Taurine: a critical nutrient for future fish feeds. Aquaculture 2015, 437, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostika, R.; Herawati, T.; Bangkit, I.; Banthani, G.; Dewanti, L. Growth of Sunu Grouper (Plectropomus leopardus) larvae that given rotivera (Bachionus rotundiformus) enriched with taurine and glutamine. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series; 2019; p. 012019. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, G.; Wang, S.; Dong, J.; Feng, J.; Xu, J.; Xia, F.; Wang, X.; Ye, J. Metabolic effect of dietary taurine supplementation on Grouper (Epinephelus coioides): a (1)H-NMR-based metabolomics study. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, R.D.; German, D.P.; Manjakasy, J.M.; Farr, I.; Hansen, M.J.; Tibbetts, I.R. Enzymatic digestion in stomachless fishes: how a simple gut accommodates both herbivory and carnivory. J Comp Physiol B 2011, 181, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogdahl, Å.; Hemre, G.I.; Mommsen, T. Carbohydrates in fish nutrition: digestion and absorption in postlarval stages. Aquac Nutr 2005, 11, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonville, J.M.; Maher, A.D.; Coen, M.; Holmes, E.; Lindon, J.C.; Nicholson, J.K. Evaluation of full-resolution J-Resolved H-1 NMR projections of biofluids for metabonomics information retrieval and biomarker identification. Anal Chem 2010, 82, 1811–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, J.; Tsuboi, Y.; Komatsu, K.; Gomi, M.; Chikayama, E.; Date, Y. Spin Couple: Development of a web tool for analyzing metabolite mixtures via two-dimensional J-Resolved NMR database. Anal Chem 2016, 88, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misawa, T.; Komatsu, T.; Date, Y.; Kikuchi, J. SENSI: signal enhancement by spectral integration for the analysis of metabolic mixtures. Chem Commun 2016, 52, 2964–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikayama, E.; Sekiyama, Y.; Okamoto, M.; Nakanishi, Y.; Tsuboi, Y.; Akiyama, K.; Saito, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Kikuchi, J. Statistical indices for simultaneous large-scale metabolite detections for a single NMR spectrum. Anal Chem 2010, 82, 1653–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Date, Y.; Kikuchi, J. Application of a deep neural network to metabolomics studies and its performance in determining important variables. Anal Chem 2018, 90, 1805–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakura, T.; Sakata, K.; Date, Y.; Kikuchi, J. Regional feature extraction of various fishes based on chemical and microbial variable selection using machine learning. Anal Methods 2018, 10, 2160–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, T.; Ohishi, R.; Shino, A.; Akashi, K.; Kikuchi, J. Multi-Spectroscopic Analysis of Seed Quality and 13C-Stable-Iotopologue Monitoring in Initial Growth Metabolism of Jatropha curcas L. Metabolites 2014, 4, 1018–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, I.A.; Schommer, S.C.; Markley, J.L. rNMR: open source software for identifying and quantifying metabolites in NMR spectra. Magn Reson Chem 2009, 47, S123–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.G.; Psychogios, N.; Young, N.; Wishart, D.S. MetaboAnalyst: a web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, W652–W660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikunov, Y.; Lommen, A.; de Vos, C.H.R.; Verhoeven, H.A.; Bino, R.J.; Hall, R.D.; Bovy, A.G. A novel approach for nontargeted data analysis for metabolomics. Large-scale profiling of tomato fruit volatiles. Plant Physiol 2005, 139, 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Differences based on feed type using distance information and the corresponding heatmap. a) Shows Nonmetric Multidimensional Scaling. Each circle shows distance information of feed similarity. b) Shows the ratio of signal intensities measured by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy between feed types. Data is sorted by metabolite similarity (Ward method, dendrogram not shown). A normalization step was performed for each metabolite.

Figure 1.

Differences based on feed type using distance information and the corresponding heatmap. a) Shows Nonmetric Multidimensional Scaling. Each circle shows distance information of feed similarity. b) Shows the ratio of signal intensities measured by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy between feed types. Data is sorted by metabolite similarity (Ward method, dendrogram not shown). A normalization step was performed for each metabolite.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of the components in the muscles of P. leopardus sorted by time (days) after hatching. Fish are arranged in descending order from top to bottom, with natural ocean fish at the bottom. Left, number of days since hatching; right, main feed type. Circles, squares, and triangles indicate brachionus, artemia, and artificial bait, respectively. The graph is sorted by metabolite similarity (Ward method, dendrogram not shown). A normalization step was performed for each metabolite.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of the components in the muscles of P. leopardus sorted by time (days) after hatching. Fish are arranged in descending order from top to bottom, with natural ocean fish at the bottom. Left, number of days since hatching; right, main feed type. Circles, squares, and triangles indicate brachionus, artemia, and artificial bait, respectively. The graph is sorted by metabolite similarity (Ward method, dendrogram not shown). A normalization step was performed for each metabolite.

Figure 3.

Distribution of common relevant factors to time fluctuations for separating high- and low-growth by machine learning. Relevant factors for classifying fish into high- and low-growth groups on each sampling day were calculated using the random forest method. It was repeated 20 times, and each Gini impurity was used as an importance score. The x-axis represents the values on the right. In the list on the right, numbers next to names indicate multiple signals measured from the same component. Conversely, a signal with multiple names indicates overlapping signals. The horizontal black line indicates the average, and the vertical bar indicates one standard deviation.

Figure 3.

Distribution of common relevant factors to time fluctuations for separating high- and low-growth by machine learning. Relevant factors for classifying fish into high- and low-growth groups on each sampling day were calculated using the random forest method. It was repeated 20 times, and each Gini impurity was used as an importance score. The x-axis represents the values on the right. In the list on the right, numbers next to names indicate multiple signals measured from the same component. Conversely, a signal with multiple names indicates overlapping signals. The horizontal black line indicates the average, and the vertical bar indicates one standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Probabilistic network for large and small fish based on important growth factors. Those components used were extracted from random forest regression and those that suggest a relationship between taurine and glycine. (a) was drawn using large sample data(top 10%), and (b) was drawn using small sample data(bottom 10%). The arrows indicate the probabilistic direction, and the line width indicates the strength of the connection. Red borders indicate important factors for growth (objective variables for regression), green indicates amino acids, yellow indicates glucose and blue indicates other components.

Figure 4.

Probabilistic network for large and small fish based on important growth factors. Those components used were extracted from random forest regression and those that suggest a relationship between taurine and glycine. (a) was drawn using large sample data(top 10%), and (b) was drawn using small sample data(bottom 10%). The arrows indicate the probabilistic direction, and the line width indicates the strength of the connection. Red borders indicate important factors for growth (objective variables for regression), green indicates amino acids, yellow indicates glucose and blue indicates other components.

Figure 5.

Time-series heatmap of growth-related components for fish groups with large and small body sizes. Fish growth increases from left to right. The top half shows large fish, and the bottom shows the small fish. Scaling was performed in the time direction. The main feed type is shown at the bottom. Circles, squares, and triangles indicate brachionus, artemia, and artificial bait, respectively.

Figure 5.

Time-series heatmap of growth-related components for fish groups with large and small body sizes. Fish growth increases from left to right. The top half shows large fish, and the bottom shows the small fish. Scaling was performed in the time direction. The main feed type is shown at the bottom. Circles, squares, and triangles indicate brachionus, artemia, and artificial bait, respectively.

Figure 6.

1H–13C HSQC spectra of water-soluble metabolites in P. leopardus muscle tissue. a: Coupling constants between carbon atoms shown in Hz and indicated by arrows. Carbon atoms of the amino acids are successively numbered from the carboxyl carbon next to those carrying the amino group. Colored signals are 13C-labeled metabolites derived from 13C-labeled starch in the feed. Green, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P); red, glycine; blue, lactate; light green, alanine. b: Illustration of the metabolism of 13C-labeled starch into other compounds based on visual inspection of NMR data.

Figure 6.

1H–13C HSQC spectra of water-soluble metabolites in P. leopardus muscle tissue. a: Coupling constants between carbon atoms shown in Hz and indicated by arrows. Carbon atoms of the amino acids are successively numbered from the carboxyl carbon next to those carrying the amino group. Colored signals are 13C-labeled metabolites derived from 13C-labeled starch in the feed. Green, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P); red, glycine; blue, lactate; light green, alanine. b: Illustration of the metabolism of 13C-labeled starch into other compounds based on visual inspection of NMR data.

Figure 7.

1H–13C correlation and 1H–1H J-resolved NMR spectrum of muscle tissue. a, b: Two-dimensional HSQC spectrum. c: Two-dimensional 2D-Jres spectrum. d: Skyline plot of c. The color indicates intensity. When blue is one, green is twice as strong, yellow is four times as strong, and red is eight times as strong.

Figure 7.

1H–13C correlation and 1H–1H J-resolved NMR spectrum of muscle tissue. a, b: Two-dimensional HSQC spectrum. c: Two-dimensional 2D-Jres spectrum. d: Skyline plot of c. The color indicates intensity. When blue is one, green is twice as strong, yellow is four times as strong, and red is eight times as strong.

Figure 8.

Histogram showing original growth distribution of P. leopardus and simulation results of aquaculture using starch effectively. Red histogram indicates length of P. leopardus at 52 days after hatching, and blue histogram indicates the simulated result. The simulation was scaled such that the average improvement is 30% and deviation is 10%.

Figure 8.

Histogram showing original growth distribution of P. leopardus and simulation results of aquaculture using starch effectively. Red histogram indicates length of P. leopardus at 52 days after hatching, and blue histogram indicates the simulated result. The simulation was scaled such that the average improvement is 30% and deviation is 10%.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).