Submitted:

13 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Molecular Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

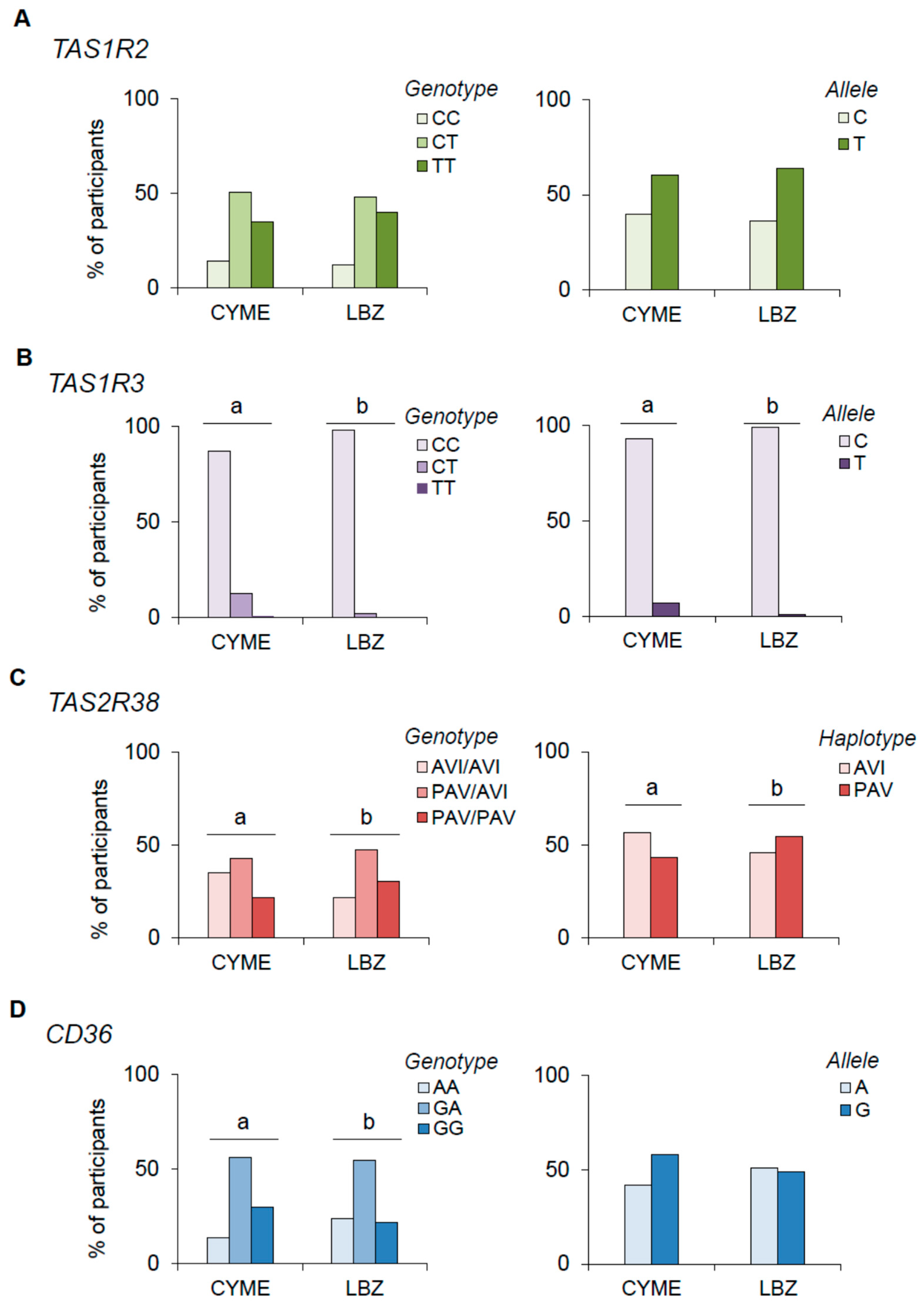

3.1. Genotype Distributions and Allele Frequencies of the TAS1R2, TAS1R3, TAS2R38, and CD36 SNPs in LBZ and CYME Cohorts

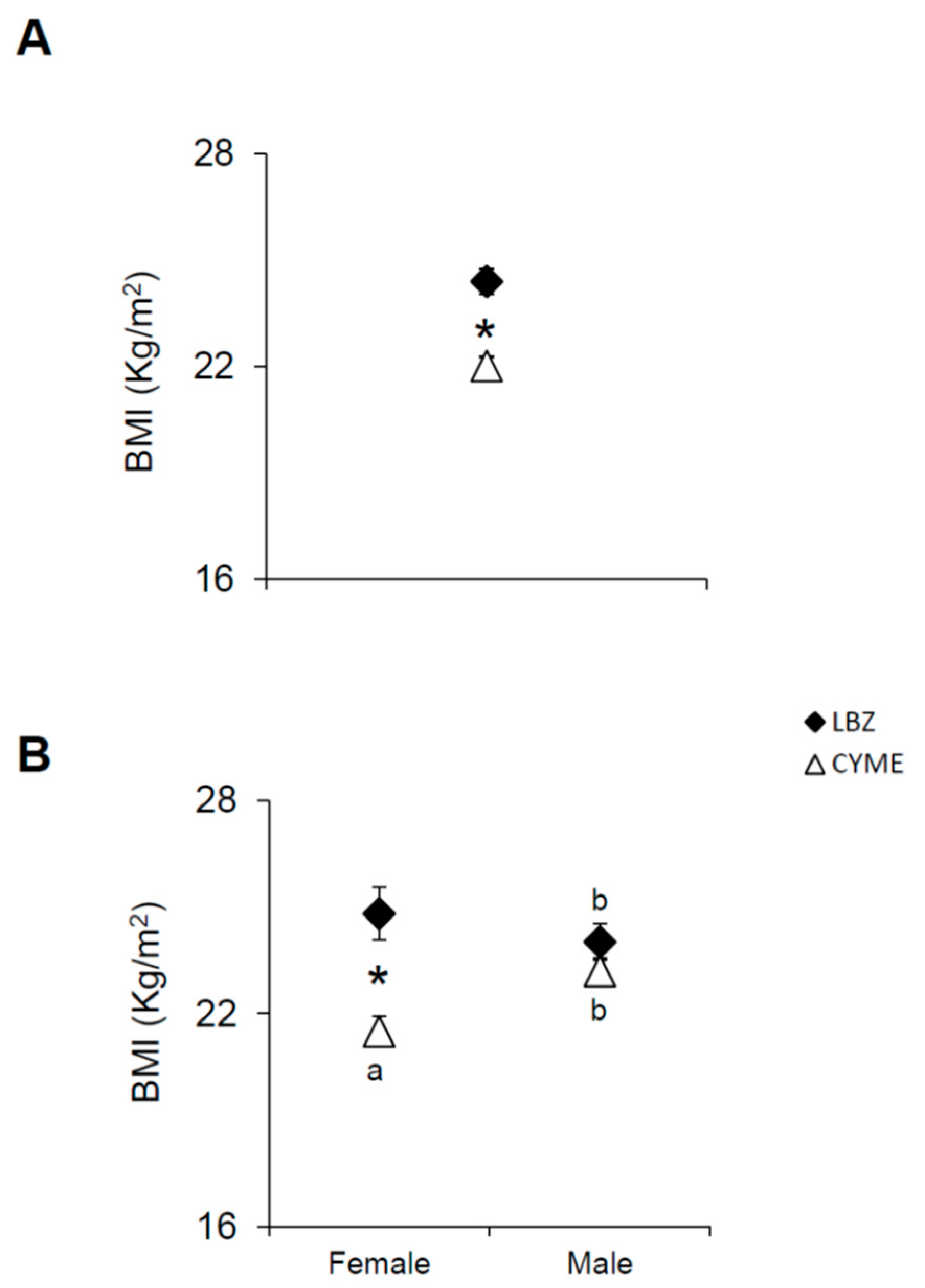

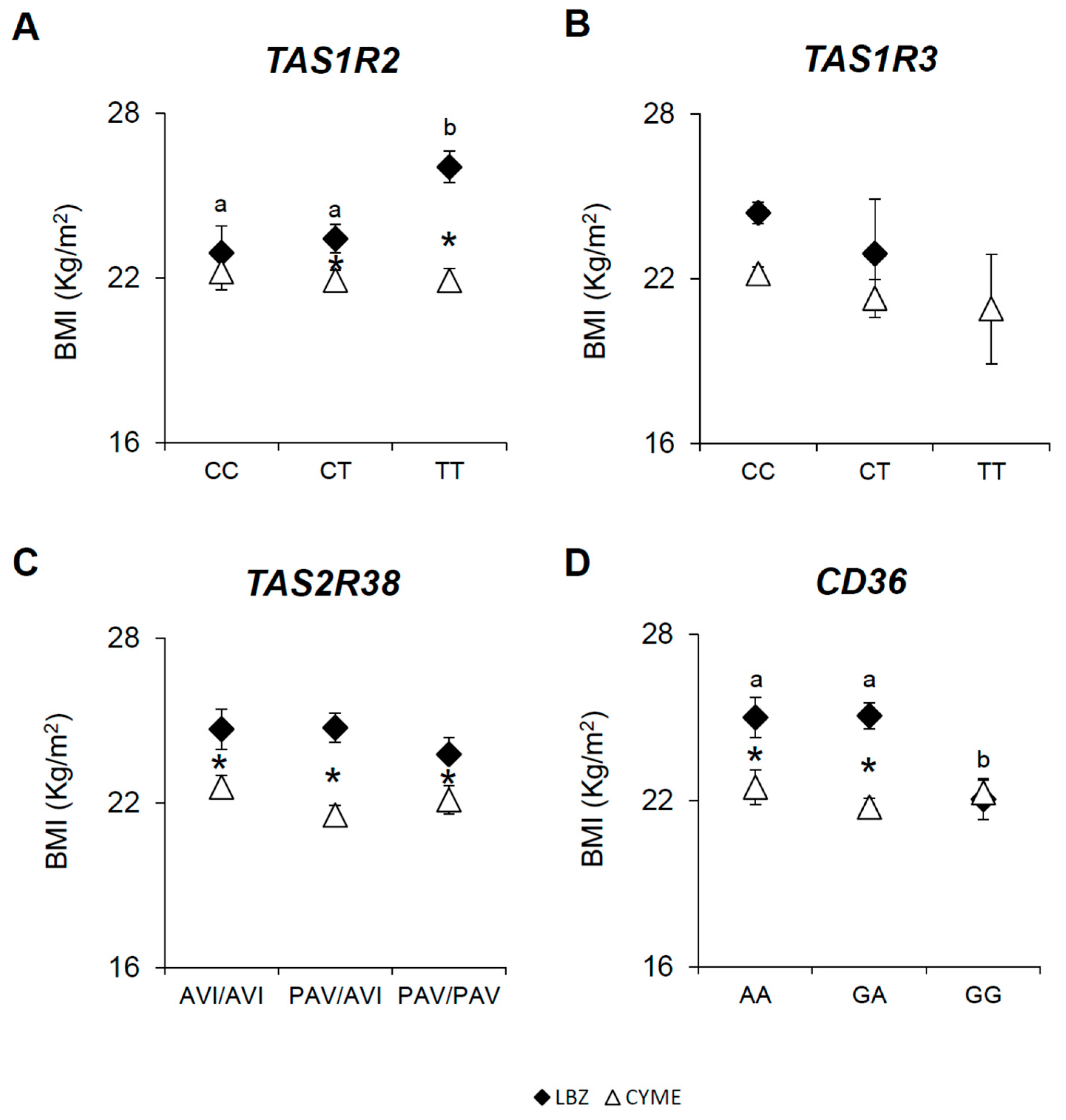

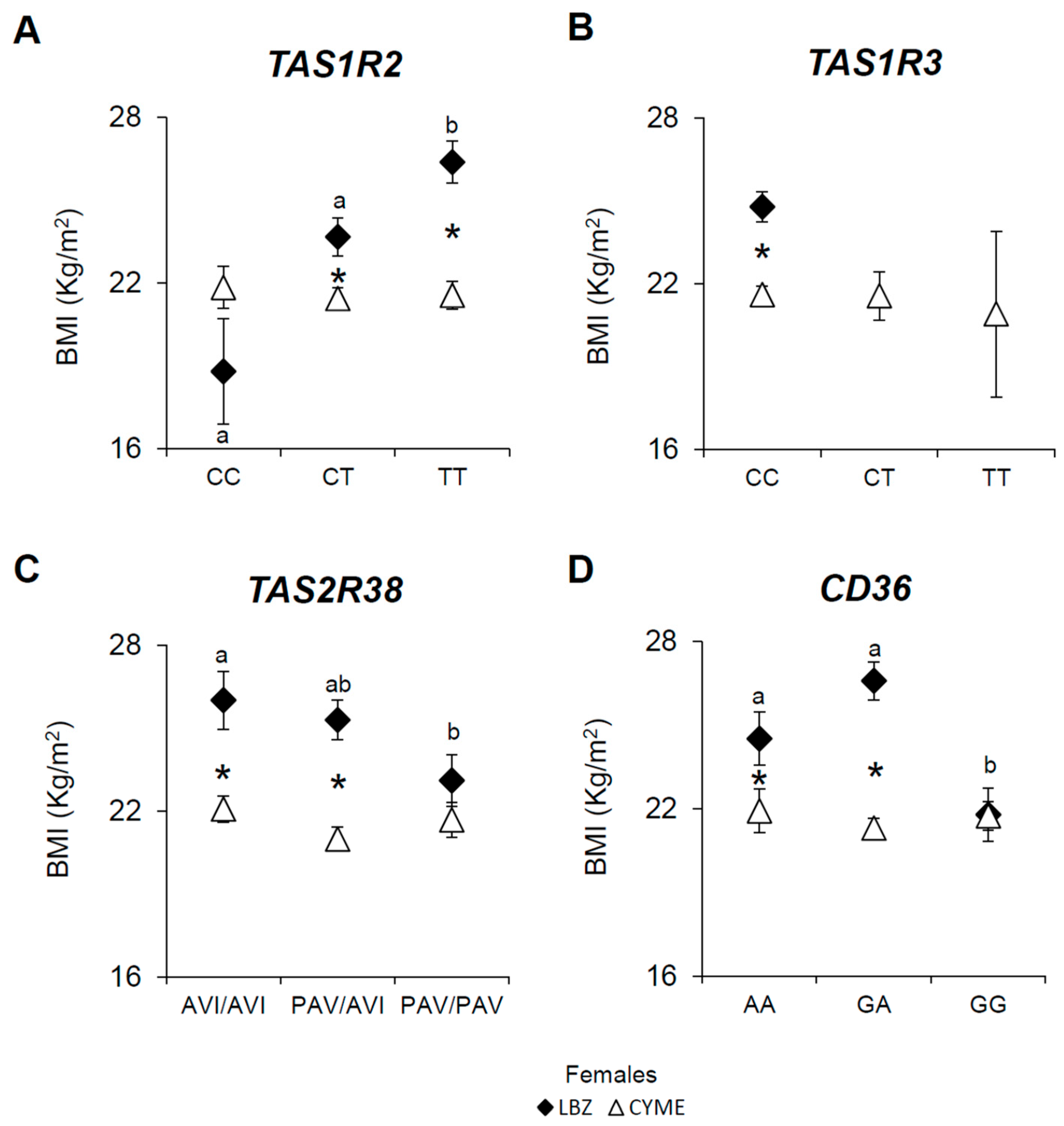

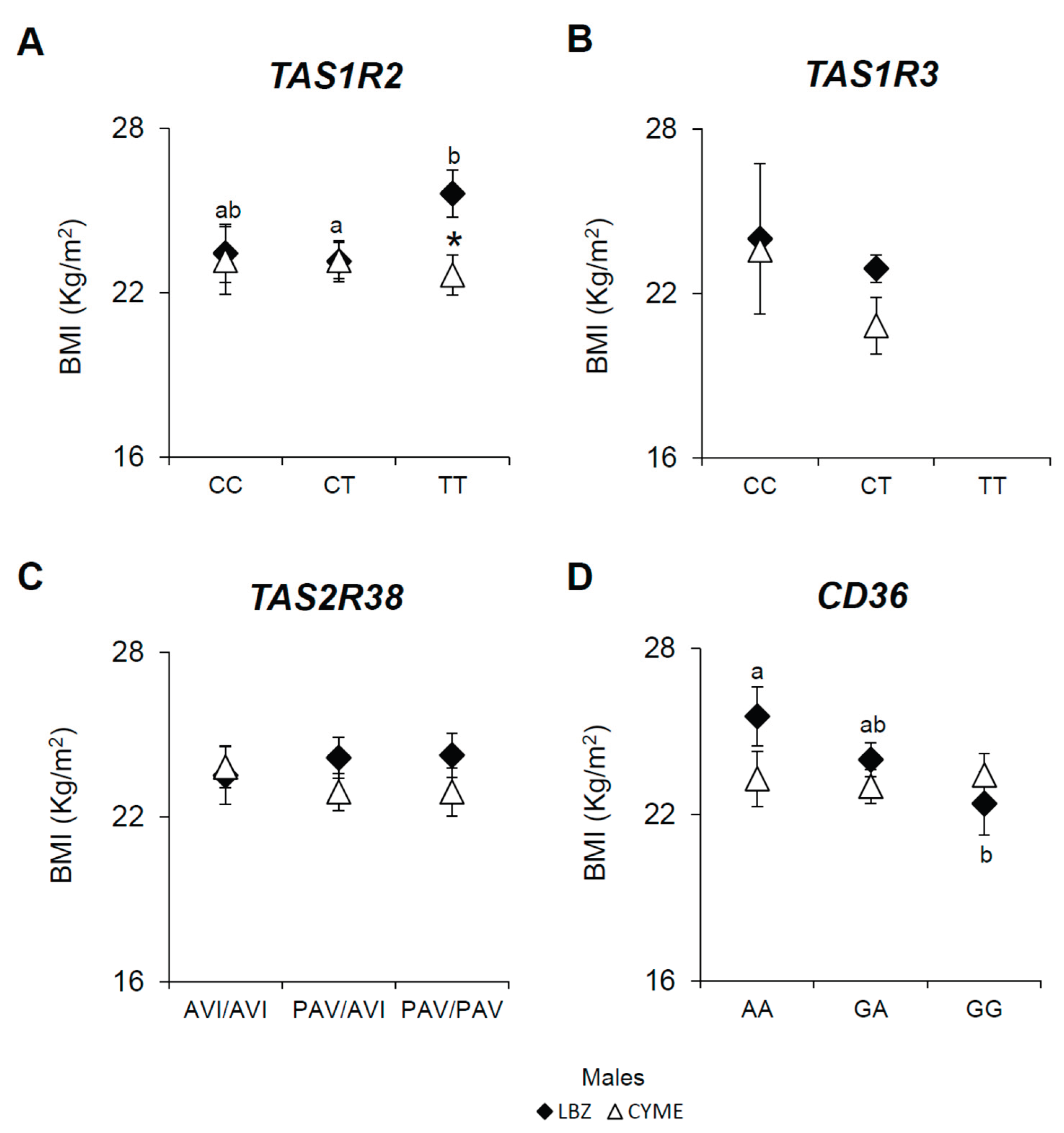

3.2. Associations Between the TAS1R2, TAS1R3, TAS2R38, and CD36 SNPs, BMI, and Gender in LBZ and CYME Cohorts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tepper, B.J. Nutritional implications of genetic taste variation: the role of PROP sensitivity and other taste phenotypes. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2008, 28, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, B.J.; et al. Genetic sensitivity to the bitter taste of 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) and its association with physiological mechanisms controlling body mass index (BMI). Nutrients 2014, 6, 3363–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, M.; Meyerhof, W. Oral and extraoral bitter taste receptors. In Sensory and Metabolic Control of Energy Balance. Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation, 2010/09/25 ed.; Meyerhof, W., Beisiegel, U., Joost, HG., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; Volume 52, pp. 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Depoortere, I. Taste receptors of the gut: emerging roles in health and disease. Gut 2014, 63, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.A.; et al. Extraoral bitter taste receptors as mediators of off-target drug effects. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 4827–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laffitte, A.; et al. Functional roles of the sweet taste receptor in oral and extraoral tissues. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2014, 17, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, K.; Ishimaru, Y. Oral and extra-oral taste perception. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013, 24, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.; et al. Extraoral bitter taste receptors in health and disease. J. Gen. Physiol. 2017, 149, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; et al. Functional bitter taste receptors are expressed in brain cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 406, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhari, N.; Roper, S.D. The cell biology of taste. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 190, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattes, R.D. Is there a fatty acid taste? Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2009, 29, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, G.; et al. An amino-acid taste receptor. Nature 2002, 416, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponnusamy, V.; et al. T1R2/T1R3 polymorphism affects sweet and fat perception: Correlation between SNP and BMI in the context of obesity development. Human Genetics 2025, 144, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, B.J.; et al. Factors Influencing the Phenotypic Characterization of the Oral Marker, PROP. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, G.L.; et al. Influence of PROP taster status and maternal variables on energy intake and body weight of pre-adolescents. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 90, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorovic, N.; et al. Genetic variation in the hTAS2R38 taste receptor and brassica vegetable intake. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 2011, 71, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, V.B.; Bartoshuk, L.M. Food acceptance and genetic variation in taste. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2000, 100, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, J.E.; Duffy, V.B. Revisiting sugar-fat mixtures: sweetness and creaminess vary with phenotypic markers of oral sensation. Chem. Senses 2007, 32, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, B.J.; et al. Genetic variation in taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil and its relationship to taste perception and food selection. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1170, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, B.J.; Nurse, R.J. PROP taster status is related to fat perception and preference. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998, 855, 802–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverstein, R.L.; Febbraio, M. CD36, a scavenger receptor involved in immunity, metabolism, angiogenesis, and behavior. Sci Signal 2009, 2, re3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Abumrad, N.A. Cellular fatty acid uptake: a pathway under construction. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2009, 20, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; et al. A common haplotype at the CD36 locus is associated with high free fatty acid levels and increased cardiovascular risk in Caucasians. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, 2197–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love-Gregory, L.; et al. Variants in the CD36 gene associate with the metabolic syndrome and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Hum Mol Genet 2008, 17, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwenk, R.W.; et al. Regulation of sarcolemmal glucose and fatty acid transporters in cardiac disease. Cardiovasc Res 2008, 79, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; et al. Hepatic fatty acid transporter Cd36 is a common target of LXR, PXR, and PPARgamma in promoting steatosis. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuwatari, T.; et al. Role of gustation in the recognition of oleate and triolein in anosmic rats. Physiol. Behav. 2003, 78, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; et al. CD36 as a lipid sensor. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 105, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; et al. The lipid-sensor candidates CD36 and GPR120 are differentially regulated by dietary lipids in mouse taste buds: impact on spontaneous fat preference. PLoS One 2011, 6, e24014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melis, M.; et al. Associations between orosensory perception of oleic acid, the common single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs1761667 and rs1527483) in the CD36 gene, and 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) tasting. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2068–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepino, M.Y.; et al. The fatty acid translocase gene CD36 and lingual lipase influence oral sensitivity to fat in obese subjects. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laugerette, F.; et al. CD36 involvement in orosensory detection of dietary lipids, spontaneous fat preference, and digestive secretions. J. Clin. Invest. 2005, 115, 3177–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.; et al. Platelet CD36 surface expression levels affect functional responses to oxidized LDL and are associated with inheritance of specific genetic polymorphisms. Blood 2011, 117, 6355–6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love-Gregory, L.; et al. Common CD36 SNPs reduce protein expression and may contribute to a protective atherogenic profile. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, K.; et al. Pathophysiology of human genetic CD36 deficiency. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2003, 13, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, G.; et al. Targeting metastasis-initiating cells through the fatty acid receptor CD36. Nature 2017, 541, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melis, M.; et al. Polymorphism rs1761667 in the CD36 Gene Is Associated to Changes in Fatty Acid Metabolism and Circulating Endocannabinoid Levels Distinctively in Normal Weight and Obese Subjects. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasumatsu, K.; Tokita, K. Fat Taste Nerves and Their Function in Food Intake Regulation. Current Oral Health Reports 2022, 9, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pes, G.M.; et al. Sociodemographic, clinical and functional profile of nonagenarians from two areas of Sardinia characterised by distinct longevity levels. Rejuvenation Res. 2019, 0, null. [Google Scholar]

- Pes, G.M.; et al. Male longevity in Sardinia, a review of historical sources supporting a causal link with dietary factors. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulain, M.; et al. Identification of a geographic area characterized by extreme longevity in the Sardinia island: the AKEA study. Exp. Gerontol. 2004, 39, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, C.; et al. CD36: an emerging therapeutic target for cancer and its molecular mechanisms. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 2022, 148, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diószegi, J.; et al. Genetic Background of Taste Perception, Taste Preferences, and Its Nutritional Implications: A Systematic Review. Front Genet 2019, 10, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soranzo, N.; et al. Positive selection on a high-sensitivity allele of the human bitter-taste receptor TAS2R16. Curr Biol, 2005, 15, 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooding, S.; et al. Natural Selection and Molecular Evolution in PTC, a Bitter-Taste Receptor Gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 74, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; et al. Relaxation of selective constraint and loss of function in the evolution of human bitter taste receptor genes. Hum Mol Genet 2004, 13, 2671–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, U.K.; et al. Variation in the human TAS1R taste receptor genes. Chem Senses 2006, 31, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fushan, A.A.; et al. Allelic polymorphism within the TAS1R3 promoter is associated with human taste sensitivity to sucrose. Curr Biol. 2009, 19, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecati, M.; et al. TAS1R3 and TAS2R38 Polymorphisms Affect Sweet Taste Perception: An Observational Study on Healthy and Obese Subjects. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melis, M.; et al. Associations between Sweet Taste Sensitivity and Polymorphisms (SNPs) in the TAS1R2 and TAS1R3 Genes, Gender, PROP Taster Status, and Density of Fungiform Papillae in a Genetically Homogeneous Sardinian Cohort. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, L.D.; et al. Sweet Taste Perception is Associated with Body Mass Index at the Phenotypic and Genotypic Level. Twin Res Hum Genet 2016, 19, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melis, M.; et al. TAS2R38 bitter taste receptor and attainment of exceptional longevity. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 18047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adappa, N.D.; et al. TAS2R38 genotype predicts surgical outcome in nonpolypoid chronic rhinosinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016, 6, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adappa, N.D.; et al. Correlation of T2R38 taste phenotype and in vitro biofilm formation from nonpolypoid chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016, 6, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adappa, N.D.; et al. T2R38 genotype is correlated with sinonasal quality of life in homozygous DeltaF508 cystic fibrosis patients. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016, 6, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adappa, N.D.; et al. The bitter taste receptor T2R38 is an independent risk factor for chronic rhinosinusitis requiring sinus surgery. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014, 4, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.J.; et al. T2R38 taste receptor polymorphisms underlie susceptibility to upper respiratory infection. J. Clin. Invest. 2012, 122, 4145–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.J.; Cohen, N.A. The emerging role of the bitter taste receptor T2R38 in upper respiratory infection and chronic rhinosinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2013, 27, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.J.; Cohen, N.A. Role of the bitter taste receptor T2R38 in upper respiratory infection and chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 15, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Workman, A.D.; Cohen, N.A. Bitter taste receptors in innate immunity: T2R38 and chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Rhinol.-Otol. 2017, 5, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wendell, S.; et al. Taste genes associated with dental caries. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, S.; et al. Genotype-specific regulation of oral innate immunity by T2R38 taste receptor. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 68, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latorre, R.; et al. Expression of the Bitter Taste Receptor, T2R38, in Enteroendocrine Cells of the Colonic Mucosa of Overweight/Obese vs. Lean Subjects. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0147468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carta, G.; et al. Participants with Normal Weight or with Obesity Show Different Relationships of 6-n-Propylthiouracil (PROP) Taster Status with BMI and Plasma Endocannabinoids. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, K.I.; Tepper, B.J. Short-term vegetable intake by young children classified by 6-n-propylthoiuracil bitter-taste phenotype. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Bailo, B.; et al. Genetic variation in taste and its influence on food selection. Omics 2009, 13, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrai, M.; et al. Association between TAS2R38 gene polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk: a case-control study in two independent populations of Caucasian origin. PLoS One 2011, 6, e20464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cossu, G.; et al. 6-n-propylthiouracil taste disruption and TAS2R38 nontasting form in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melis, M.; et al. Taste disorders are partly genetically determined: Role of the TAS2R38 gene, a pilot study. Laryngoscope 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.H.; et al. Genetic Variation in the TAS2R38 Bitter Taste Receptor and Gastric Cancer Risk in Koreans. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pes, G.M.; et al. Association between Mild Overweight and Survival: A Study of an Exceptionally Long-Lived Population in the Sardinian Blue Zone. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camillo, L.; et al. Bitter Taste Receptors 38 and 46 Regulate Intestinal Peristalsis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.J.; Cohen, N.A. Taste receptors in innate immunity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015, 72, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzago, M.; et al. Genetic Variants in CD36 Involved in Fat Taste Perception: Association with Anthropometric and Clinical Parameters in Overweight and Obese Subjects Affected by Type 2 Diabetes or Dysglycemia-A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepino, M.Y.; et al. Structure-function of CD36 and importance of fatty acid signal transduction in fat metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2014, 34, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F. Sex differences in energy metabolism: natural selection, mechanisms and consequences. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2024, 20, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, S.S.-C.; Egan, J.M. The endocrinology of taste receptors. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2015, 11, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahir, N.S.; et al. Sex differences in fat taste responsiveness are modulated by estradiol. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2021, 320, E566–E580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participants | Age range | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Males | Females | ||

| (n) | (n) | (n) | (y) | |

| LBZ | 114 | 54 | 60 | 90 - 103 |

| CYME | 160 | 49 | 111 | 18 - 67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).