The study also investigates arginine’s role in nitric oxide synthesis and its metabolic benefits in Indigenous Australian diets. Furthermore, nitrogen metabolism is analysed through the lens of quantum biology, revealing novel insights into ammonium ion signalling and energy optimisation. Part three delves into altitude adaptations in nitrate utilisation and nitric oxide production, emphasising the metabolic efficiency of high-altitude populations. Finally, the significance of nasal breathing and nitric oxide in sleep regulation is discussed, providing a preference for a holistic view of dietetics, that integrates biochemistry, epigenetics, and evolutionary biology.

1. Introduction

The field of dietetics has traditionally relied on standardised nutritional guidelines that often overlook critical variables such as food preparation methods, environmental influences, and individual genetic predispositions. These variations have profound implications for dietary sufficiency and epigenetic health outcomes. Part three seeks to address these gaps by providing a comprehensive analysis of dietary amino acids, fatty acids, hormones, and their elemental ratios.

2. Amino Acids

As discussed in part two, (Sedley L 2025), due to many variables, there is a lack of consensus in food composition data (Editors at Food Standards Australia and New Zealand 2020). Standard nutritional guidelines provide an estimation of the amino acid (AA) content of the raw food product, but no consideration is taken for heating induced deamination and transamination, changes in AA ratios (Ito H, Kikuzaki H et al. 2019). Therefore, the future of nutrition and food composition is set to advance significantly, with modern computational technologies.

Currently, the source of food also impacts AA ratios in food composition data (Editors at Food Standards Australia and New Zealand 2020), for example, eggs can have different AA levels depending on the chickens feed and the environment (Attia YA, Al-Harthi MA 2020). Skeletal muscles of animals contain approximately 75% water, 20% protein, 1-10% fat and 1% glycogen, (Listrat A, Lebret B et al. 2016), yet most nutritional datasets do not account for the sugar content in meat products. The same can be said for the AA content of carbohydrate foods.

Animal and plant protein contain approximately 16% nitrogen, (Sriperm N, Pesti GM et al. 2011), however, if we calculate the ratio of total elements in all 220 primary amino acids, nitrogen comprises an average of only 7.26%. This suggests that there is significantly more nitrogen in the constituents which are not accounted for in nutritional composition data.

AA composition is based on a conversion factor which correlates to 16% nitrogen (US Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service—Nutrient Data Laboratory 2015), and the source of protein influences the conversion factor (Sriperm N, Pesti GM et al. 2011).

An accurate estimation of plant and animal nitrogen will help to determine the extent of dietary elemental deficiencies. With this information, it is possible to advance body composition and energy metabolism by utilising specific cuts of meat and organs containing unique elemental ratios and functional proteins.

As discussed in part one, (Sedley L 2025), the nitrogenous contamination of water, during the extraction of proteins, in a N2 atmosphere, can also result in increased quantification of nitrogen (Kim SY, Kim BM et al. 2014). Therefore, inaccurate quantification of nitrogen concentration in amino acids, is possible (Editors at Food Standards Australia and New Zealand 2020).

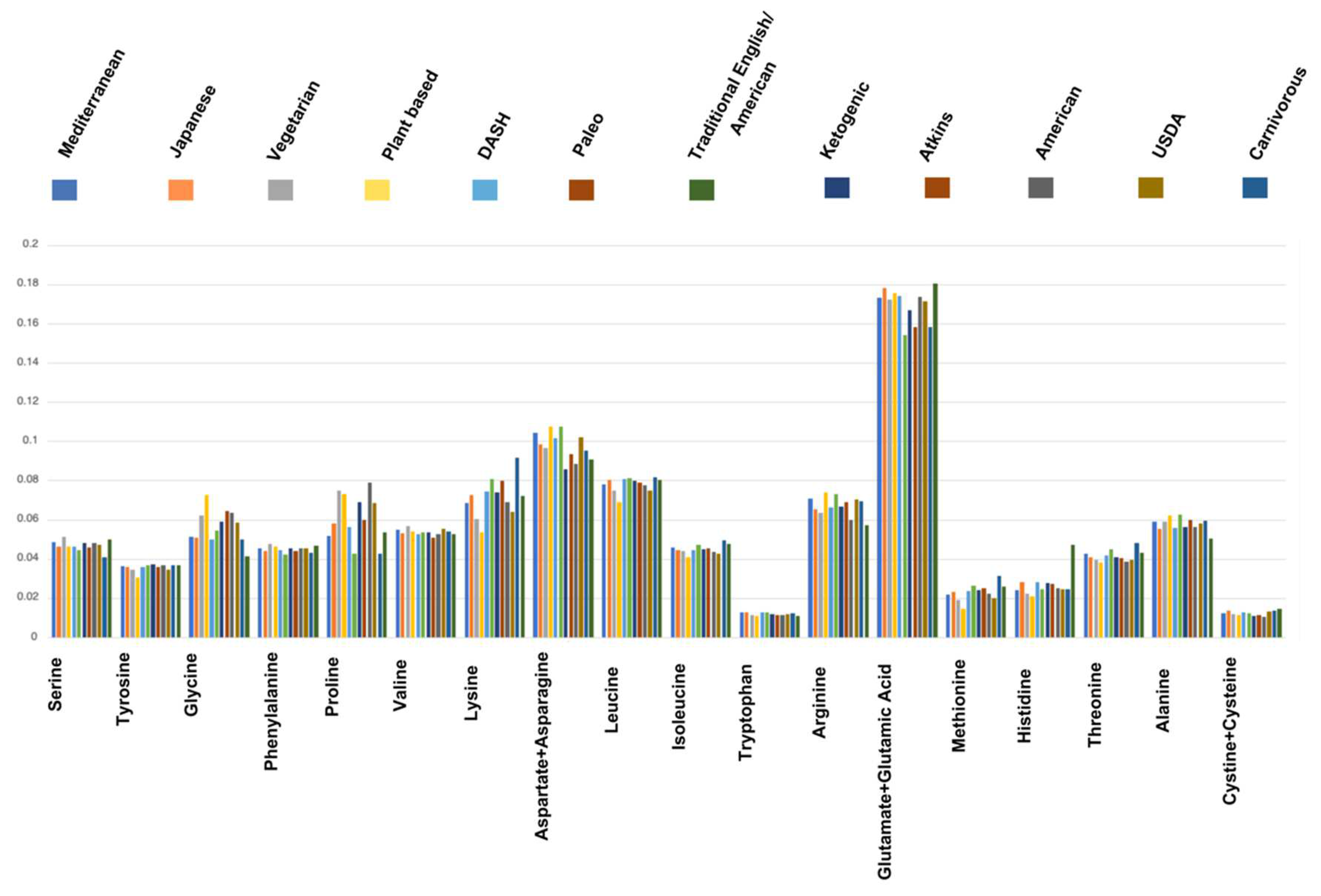

When different diets are compared, AA ratios are relatively equal. But this does not necessarily imply sufficiency and can be a source of confusion for nutrition professionals (

Figure 1).

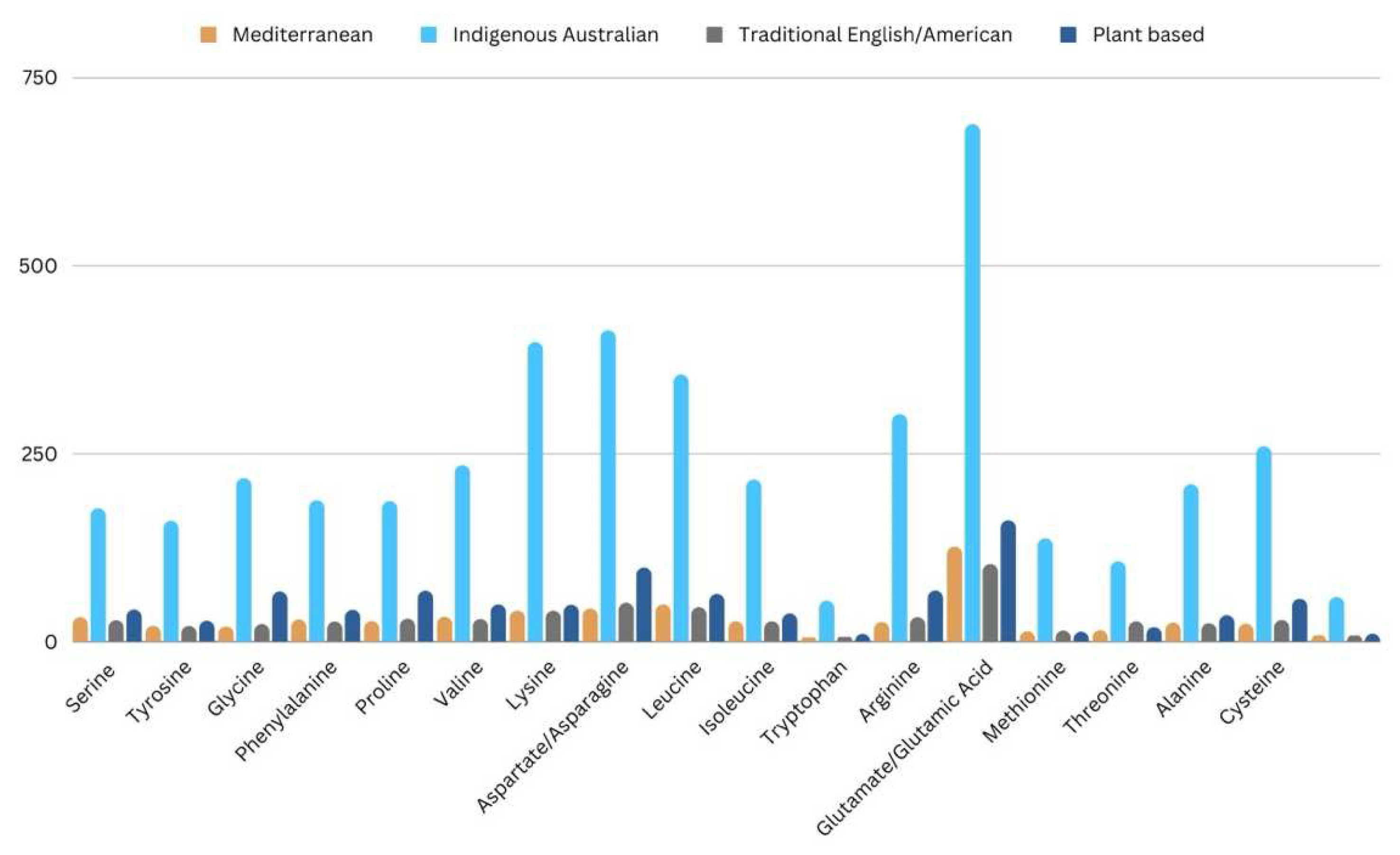

When the AA ‘levels’ of the Mediterranean, English American, Carnivorous, and plant-based diets are compared, (Supplementary data S1 & S2), significant differences can be seen, which may influence health and epigenetic mechanisms (

Figure 2).

3. Tyrosine

Although the ratios are relatively the same, there is over 5 times more phenylalanine and tyrosine in a carnivorous diet, than the other plant-based diets (

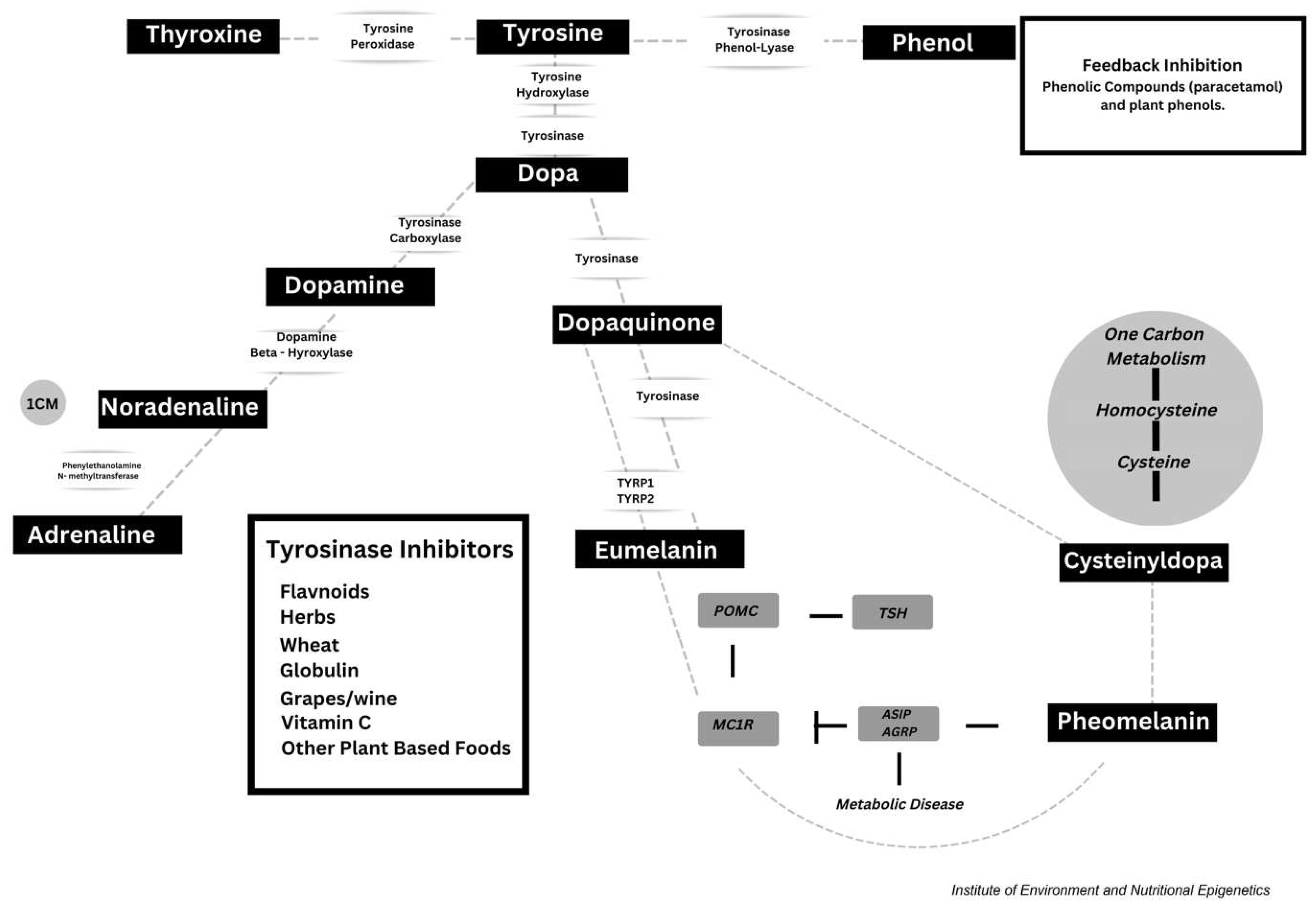

Figure 3). Figure 5, shows a highly simplified schematic of the tyrosine pathway, which does not take epigenetic mechanisms into consideration. However, it is determined that tyrosine is essential for the synthesis of melanin, thyroid hormones and several neuropeptides (Kanehisa M, 2019, 2000).

Tyrosine is considered a non-essential amino acid, meaning the human body can synthesise it in sufficient quantities. Due to a mutation and reduced expression of phenylalanine hydroxylase, some people have a complete inability to synthesise tyrosine, resulting in a condition known as phenylketonuria or PKU (Matthews DE 2007) & (Williams RA, Mamotte CD et al. 2008). PKU presents with neurological impairment and a fair phenotype due to a lack of melanin (Williams RA, Mamotte CD et al. 2008). However, we now understand that a mutation is not the only factor influencing gene expression. Epigenetic mechanisms also influence the rate in which we synthesise any molecule; these mechanisms are unique to the individual and depend entirely on evolutionary history (Sedley L 2023). This means that depending on our dietary evolution, not all of us are capable of synthesising sufficient tyrosine.

Thyroid hormones are pivotal in the thermoregulatory response of the skin. The skin of patients with hypothyroidism is dryer, cooler, and rougher, compared to hyperthyroid patients who excessively perspire; are hot, itchy and can display abnormal pigmentation (Antonini D, Sibilio A et al. 2013). There is a lack of research conducted in eumelanin dominant populations regarding thermoregulation (Lang JA 2020), but given that eumelanin absorbs greater UV-R, epigenetic thermoregulatory differences as evidenced by Indigenous Australians, are likely to be essential in preventing overheating.

The agouti signalling protein (ASIP), its alleles, and the agouti related protein (AGRP), are responsible for skin and hair pigmentation (Yu S, Wang G et al. (2019) & (Bonilla C, Boxill LA et al. 2005) & (Deem JD, Faber CL et al. 2022) & (Barsh GS, Ollmann MM et al. 2006). ASIP action on the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) at the skin, results in reduced tyrosinase activity, and a diversion in synthesis from dark black eumelanin to the lighter red pheomelanin (Hida T, Kamiya T et al. 2020) (Figure 5).

Pheomelanin differs from eumelanin in that it incorporates cysteine into its structure which is derived from homocysteine as part of the trans-sulfation pathway (Morgan AM, Lo J et al. 2013). Extensive ASIP expression, gives rise to a characteristic metabolic phenotype that includes type 2 diabetes, yellow/red hair, and obesity (Hida T, Kamiya T et al. 2020) & (McNulty JC, Jackson PJ et al. 2005) & (Kempf E, Landgraf K et al. 2022).

Endogenous phenols derived from the degradation of eumelanin, inhibit tyrosinase and eumelanin synthesis (Shane B 2011). Phenol based topical pharmaceuticals are used to inhibit pigmentation (Hida T, Kamiya T et al. 2020). Many phenolic constituents of plant-based foods and herbs contain tyrosinase inhibitors, (Zolghadri S, Bahrami A et al. 2019), including wheat bran globulin (Zolghadri S, Bahrami A et al. 2019) wine, and vitamin C (Zolghadri S, Bahrami A et al. 2019).

Thus, a weighty dietary change from a carnivorous diet, may have played a key role in evolutionary skin lightening, neurological differences, metabolic health, and thyroid hormone regulated metabolism.

Interestingly, it was documented very early, that an Australian Indigenous tribes recalled an epidemic of feet swelling and ulcerations that swept through the nation (Morgan J 1979). This is symptomatic of poor glycaemic control, and may have been the first indication of poor adaptation to increasing plant foods in this population. Moreover, the tribe that recalled the epidemic had unusually lighter skin, than other tribes in the region, suggesting that a reduction in tyrosine due to the switch to consume more plants may have already commenced to influence skin pigmentation in Australia, as early as 1803.

4. Arginine

Arginine is essential for nitric oxide (NO) synthesis; the semi-carnivorous Indigenous Australian consumed 10 times more arginine compared to those consuming a standard western diet (

Figure 4). In addition, from animal protein, they also derived active transcription factors like oestrogen, which plays a key role in endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) synthesis (Sharma M, Singh K et al. 2020). Nitric oxide (NO) mechanisms are complex. If we recall back to carbon, in part two (Sedley L 2025), NO’s actions are compartmentalised. It inhibits one carbon metabolism (1-CM), and its translocation activates methylation in hypoxia, moreover, eNOS is self-regulated in that the protein’s S-nitrosylation inhibits its own expression (Sedley L 2023)

5. NH4+ (Ammonium Ion)

When it comes to nitrogen metabolism, there is still a wealth of knowledge to be gained. We have only commenced amalgamating physics with biology. Quantum biology advances our understanding of nutritional biochemistry by exploring atomic and subatomic interactions at the biological level (Sedley L 2025). NH4+; a waste product of excitatory neurotransmission, is now said to be an intracellular signalling molecule which is transported to astrocytes via potassium (K+) channels. It diverts pyruvate towards lactate production (Lerchundi R, Fernández-Moncada I et al. 2015), optimising alternative fuel substrates. Increased astrocytic K+ stimulates glycogen degradation and concomitant glycolysis (Choi HB, Gordon GRJ 2012). In contrast, its hydrolysed counterpart ammonia, competes with K+ at its channel, and impairs extracellular buffering, resulting in seizure (Rangroo Thrane V, Thrane A S et al. 2013). Thermodynamic studies of human energy metabolism have not considered compounds like guanine triphosphate (GTP) or NH4+, which undertake exothermic reactions, and may be more efficient than glycolysis and ATP production, in some populations (Clarke A, Pörtner HO 2010).

6. Altitude, Carbon, and Nitrogen

Those that reside at high altitudes are adapted to O2 poor conditions. Recalling back to part two, we discussed how active 1-CM is essential for the synthesis of phosphocreatine (Sedley L 2025). The Sherpa population of the Himalayas, have low baseline phosphocreatine, which increases during ascent. In contrast, lowlanders, have higher phosphocreatine, which declines during ascent, showing increased and decreased utilisation of epigenetic 1-CM and methylation respectively (Horscroft JA, Kotwica AO et al. 2017).

A highlander exhales double the NO of a lowlander (Beall CM, Laskowski D et al. 2011), and increased nitric oxide synthase (NOS) is said to be responsible (Horscroft JA, Kotwica AO et al. 2017). NO produced in the lungs, dilates pulmonary blood vessels, increases blood flow, reduces hypertension and enhances O2 uptake from the lungs, allowing highlanders to tap into lung O2 reserves by utilising environmental NO (Beall CM, Laskowski D et al. 2011). Together, this demonstrates the importance of evolutionary differences in respiratory mechanisms and metabolism.

Therefore, as discussed in part two, (Sedley L 2025), given the significantly lower oxygen in the carnivorous diet than other diets of the same calories, and the significantly reduced metabolism in the study of Indigenous Australians, (Part two Sedley L 2025), suggests this population also have a more efficient way to utilise oxygen.

7. Nitrate Utilisation at Altitude

In hypoxic conditions, reduced HO activity reduces the carbon monoxide inhibition of Cystathionine Beta Synthase (CBS), ultimately activating the trans-sulphation extension of 1-CM, producing H2S and SO2 (Sedley L 2023). Prolonged anaerobicity of muscle cells, influence the accumulation of H2S. In normoxic conditions, H2S is oxidised to form SO2 (Veeranki S, Tyagi SC 2015), which plays a highly specific role in cardiovascular function (Huang Y, Tang C et al. 2016). The consequent sulphydryl oxidation of xanthine oxidoreductase, transforms the enzymes so that it functions as xanthine oxidase (Guenter Schwarz C, Kohl JB et al. 2019) & (Battelli MG, Polito L et al. 2016). NOS utilises O2 as a substrate; but in its absence, the uncoupling of NOS promotes the release of superoxide anion (Battelli MG, Polito L et al. 2016). This reduces xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) affinity for xanthine, while increasing affinity for competitive nitrites, which are reduced to NO, by the enzyme (Battelli MG, Polito L et al. 2016) & (Bortolotti M, Polito L et al. 2021).

Hypoxia is a potent stimulus of uric acid synthesis in some populations (Sinha S, Singh SN et al. 2009). At high altitude, lowlanders have significantly more venous uric acid (383 umol/l) than highlanders (159.3 umol/l), which doubles during ascent (298 umol/l), suggesting highlanders utilise the nitrate reductase function of XOR more efficiently than lowlanders. Nitrates and nitrites have acquired a negative reputation, but their NO producing physiological benefits out way their deleterious effects in some populations (Thomas DD 2015). Interestingly, the microbiome of highlanders is sixfold more abundant in nitrate reducing proteobacteria bacteria (Quagliariello A, Di Paola M et al. 2019), which thrive in low O2 conditions (Dib JR, Eugenia MF et al. 2011), indicating the increased NO production through NOS oxidation, dietary nitrates, and the microbiome, play an essential role in altitudinal adaptation.

8. Oxygen, NO, Sulphur and Thiamine

Since sulphur can be endogenously produced by muscle tissue during anaerobic metabolism, it may play a mediating role between aerobic and anaerobic processes. For example, an excess of sulphur can disrupt glycolysis, interacting with thiamine and leading to lactate accumulation.

In Part One (Sedley L 2025), we discussed thiamine’s critical role in maintaining the balance of sulphur, nitrogen, and carbon within the body and imbalances in these elements can contribute to pathological effects. Thiamine functions as an essential cofactor in aerobic glucose metabolism (Nakamura H et al. (2020). As discussed in part two (Sedley L 2025), in early studies, despite consuming minimal carbohydrates, the Australian Indigenous population were able to maintain an RQ of 1 for up to five hours post prandial, animal meat. This suggests efficient aerobic metabolism, which is potentially supported by alternative oxygen utilisation pathways, such as nitric oxide (NO) or sulphur dioxide (SO₂). Thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) found in animal-based foods appears sufficient to support this form of aerobic metabolism, especially under conditions of limited dietary and respiratory oxygen. However, a sudden dietary shift that reduces NO production and increases oxygen consumption, heightens the demand for thiamine as a cofactor.

9. NO and Sleep

The reliance on nasal breathing may have been metabolically advantageous in the Australian population discussed in part two. The early Australians slept on the ground, outdoors, which would require a shut mouth to prevent intrusion by local insects. Nasal breathing has proven useful in preventing hypertension, infection, allergy, halitosis, attention deficits, fatigue and snoring (Ruth A 2015). Playing the didgeridoo, which requires cyclic nasal breathing (The Editors of IDIDJ Australia 2023), can substantially improve sleep apnoea (Puhan MA, Suarez A et al. 2005). In contrast, mouth breathing is typically characteristic of over breathing (Ruth A 2015), and is associated with poor attention, sleep disorders, (Sano M, Sano S et al. 2013), and learning ability (Ribeiro GCA, dos Santos ID et al. 2016).

NO produced by the cells of the paranasal sinuses, accumulates during periods of non-nasal ventilation, suggesting sufficient NO production may be essential for the very process of nasal breathing in itself (Bazak R, Elwany S et al. 2020) & (Chatkin JM, Qian W et al. 1999).

It is estimated that 50% of children are now mouth breathers (Grippaudo C, Paolantonio EG et al. 2016) & (Leal RB, Gomes MC et al. 2016). This evolutionary, physiological adaptation could serve as a method of energy conservation subsequently following a transition to consuming more dietary oxygen and producing less heat (Part two, Sedley L 2025) Generally, nasal breathing increases NO in the blood stream, contributing to vasodilation, allowing the heart to share the metabolic load, whilst reducing respiratory stress. (Lundberg JON, Settergren G et al. 1996) & (Lee YC, Lu CT e t al 2022) & (Recinto C, Efthemeou T et al. 2017). 23% of resting energy expenditure comes from cardiopulmonary function, that is, 20% from the lung function, and 80% from the heart (Horiuchi M, Fukuoka Y 2017). Neurological activity, stimulating the heart, requires direct energy (Sedley L 2023), whereas the lungs use less energy due to the mechanical elastic recoil (Hocquette J F 2004). In this case, nasal breathing would require more energy and produce more heat. Therefore, given the compartmentalised function of NO’s which involves limiting MAT induced up-regulation of 1-CM, which occurs in anaerobic conditions, and the optimisation of oxygen utilisation, may provide a dual metabolic advantage, resulting in sustaining anaerobic capacity, whilst simultaneously optimising oxygen efficiency (Sedley L 2023).

Heme oxygenase orchestrates governance of gasotransmitters for the circadian rhythm (Lee Y, Wisor JP 2022). This means that seasonal or diurnal shifts in environmental gases can influence circadian rhythms. This can be observed by general diurnal changes in respiratory patterns, such as increased C O2 production in seen at the onset of the sleep phase (Spengler CM, Czeisler CA et al. 2000). Collectively, these findings point to an exciting new direction, for future research, into sleep disorders.

10. Fatty Acid Ratios

For a long time, saturated fats and cholesterol have been associated with cardiovascular disease, however, some populations, like the French and German, paradoxically consume a diet high in cholesterol and saturated fat, and have the lowest rates of cardiovascular disease in the world (Ferriè J 2004). Elevated systolic blood pressure, which is associated with cardiovascular disease mortality, is highest in the countries that rely on a rapidly changing and convenience-based diet, which contrasts to lower rates are seen in countries who have maintained tradition (Ferriè J 2004). Precise levels of fatty acids, are tightly regulated by synthesis and oxidation pathways, which in turn are regulated by epigenetic mechanisms and the circadian rhythm (Gooley JJ, Chua ECP 2014).

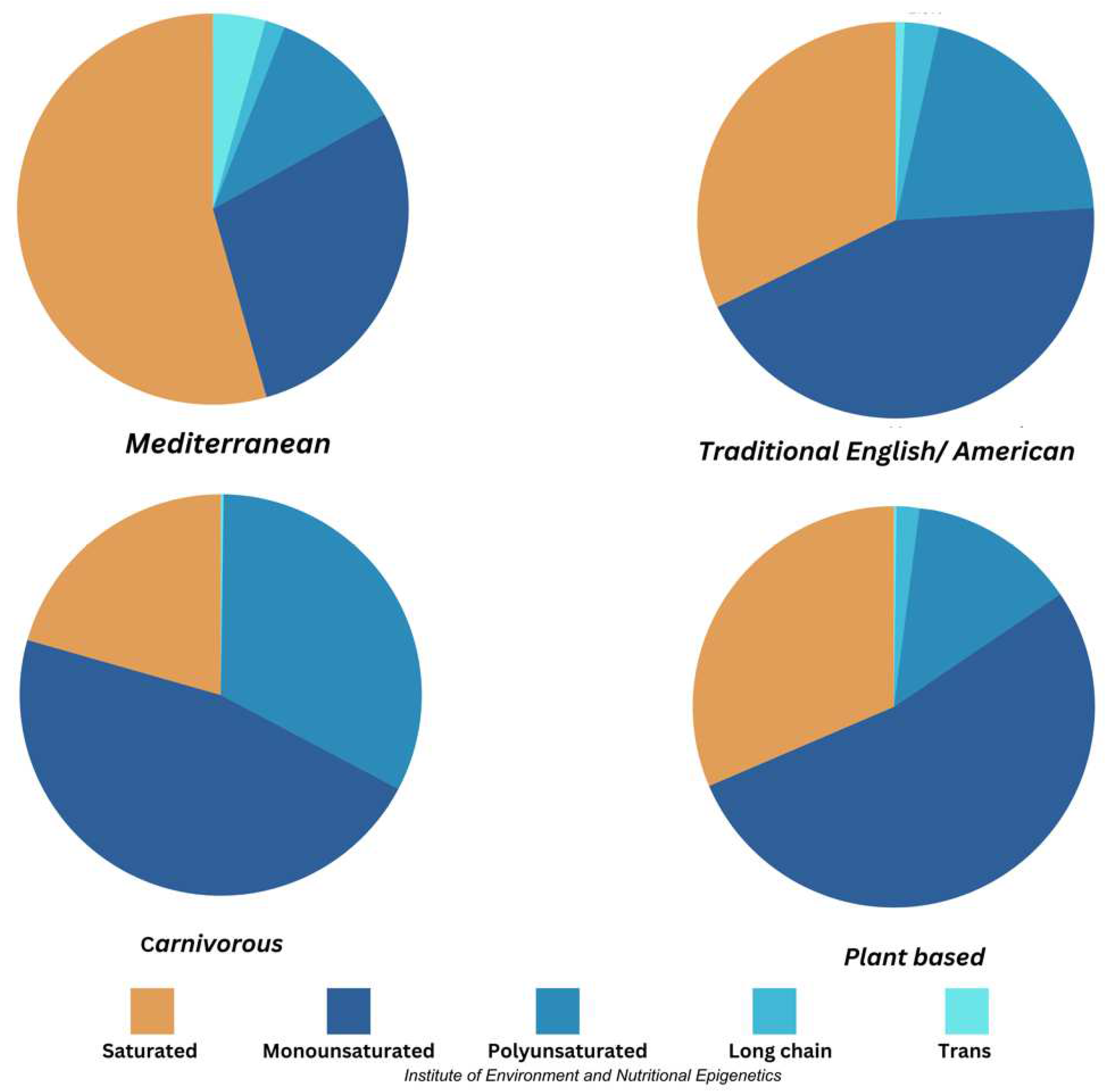

Substrates capable of epigenetic histone acylation has recently expanded with the identification of fatty acids and other acyl containing metabolic by-products showing non-histone and histone acylation properties (Resh MD 2016). Therefore, dietary fatty acid ratios play an important role in epigenetic mechanisms (Resh MD 2016). So far, over 1200 fatty acids (Li S, Gao D et al. 2019) and over 1000 acylated carnitines have been identified in the human body (Dambrova M, Makrecka-Kuka M et al. 2022). The predominant fatty acids that can acylate proteins are saturated; mono and polyunsaturated fatty acids (Resh MD 2016). Figure 6 shows the macronutrient fat ratios of the Mediterranean, English American, Carnivorous, and plant-based diets.

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPAR) are a group of nuclear receptors that behave as transcription factors (Chen L, Yang G 2014). PPAR-a regulates hepatic ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters for liver efflux of cholesterol and cholesterol transport across the blood brain barrier (Duan LP, Wang HH et al. 2006), and knock-out studies of PPAR-a show elevated plasma LDL cholesterol (More VR, Campos CR 2017).

PPAR-a is activated and inhibited by a variety of fatty acids, depending on the dose, and the chain length (Popeijus HE, van Otterdijk SD et al. 2014). Oleoylethanolamide (OEA) is the primary unsaturated activating fatty acid ligand of PPAR-a, and is derived from the saturated oleic acid (More VR, Campos CR 2017), followed closely by the unsaturated palmitoleic and oleic acids (Popeijus HE, van Otterdijk SD et al. 2014). Activation of PPAR-a stimulates beta-oxidation (Palomer X, Barroso E et al. 2018). PPAR-a activation by OEA regulates feeding, reduces body weight, prevents dyslipidemia and insulin resistance (More VR, Campos CR 2017).

Arachidonic, eicosapentaenoic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid activate and inhibit PPAR-a and its target carnitine-palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT-1) in a dose dependant manner (Popeijus HE, van Otterdijk SD et al. 2014). Saturated palmitic and stearic acids, inhibit PPAR-a expression in Hepatoblastoma cells (Popeijus HE, van Otterdijk SD et al. 2014). The Sherpa are an excellent example of unique lipid metabolism. The highlanders undergo remarkably more PPAR-a stimulated beta-oxidation than lowlanders (Horscroft JA, Kotwica AO et al. 2017). Therefore, in the absence of O2 , peroxisomal beta-oxidation may be a more efficient energy source, fascinatingly, due to the production of reactive O2 species (Sandalio LM, Rodríguez-Serrano M et al. 2013).

11. Palmitoylation

Palmitic acid (C:16) comprises 20-30% of the body’s fatty acids (Carta G, Murru E et al. 2017). ABC transporters are regulated by palmitoylation (Tada H, Nohara A et al. 2018). The ABC transporters are responsible for extra-hepatic excretion of cholesterol and plant sterols (Berge KE, Tian H et al. 2000). Mutations in ABC transporters have been implicated in a variety of diseases including schizophrenia and bipolar (ABCA13), skin disorders (ABCA12 and ABCA4), tissue cholesterol accumulation and reduced HDL (ABCA1) (Segrest JP, Tang C et al. 2022). Palmitoylation of ABC’s are primarily mediated by Zinc Finger DHHC domain containing family of palmitoyl-transferases (De I, Sadhukhan S 2018). Palmitoyl- transferase ZDHHC8 palmitoylation by ABCA1 is essential for lipid efflux (Tada H, Nohara A et al. 2018). Impaired ZDHHC5 and ZDHHC8 transporters are associated with mental health. ZDHHC9 deficient mice display altered excitatory/inhibitory synaptic balance, altered hippocampal- based learning and memory and seizure-like activity (Wang HH, Liu M et al. 2020). Impaired palmitoylation is associated with Huntington’s disease, epilepsy, speech and language impairment, and impaired neurological development (De I, Sadhukhan S 2018).

We already have a clear understanding of the macro-level fatty acid ratios across different diets (Figure 6), but future advancements in nutritional medicine will rely heavily on the precise quantification of individual fatty acids, which may profoundly influence mental health outcomes and the development of personalised treatment strategies.

12. Plant Sterols

Plant sterols are recommended by physicians and dieticians to reduce plasma cholesterol and increase high-density lipoproteins and low-density lipoprotein ratios (Tada H, Nohara A et al. 2018). Sitosterolemia is the pathological vascular accumulation of the plant sterol sitosterol due to impaired ABC cassette binding (Berge KE, Tian H et al. 2000). It is estimated, that 1 in 200,000 people, carry a pathogenic mutation, however, epigenetic research indicates, a mutation is not required to suffer the negative side-effects of altered gene expression. It is highly unlikely that any human would have had sufficient time to evolutionarily adapt to large quantities of isolated plant sterols, thus, inadequate gene expression and the global burden of arterial plant sterol accumulation may be far greater than currently assumed. Plant sterols are highly methylated and can behave as endocrine disruptors; binding and interfering with transcription factors such as oestradiol receptor-alpha, ultimately inhibiting essential enzymes for downstream cholesterol metabolism like 17-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (Qasimi MI, Nagaoka K et al. 2017). The future of diagnostic arterial disease requires specific analysis of the constituent’s contributing to a patient’s arterial disease, for better personalised health care.

13. Hormone Related Disease

The global burden of endocrine disorders is astronomical, with most adults suffering some sort of endocrine or hormone related illness (Crafa A, Calogero AE et al. 2021). Endogenously synthesised hormones or those obtained from our diet possess epigenetic activity through activation of transcription factors. Therefore, rapid modifications to diet require efficient epigenetic adaptation, which may be impaired under specific circumstances (Sedley L 2023). Due to molecular mimicry, many environmental chemicals disrupt normal endocrine epigenetic mechanisms influencing the burden (Sedley 2020).

14. Thyroid Hormones

Besides synthesis from tyrosine, the GIT acts as a reservoir of thyroid hormones. Thyroid hormone is taken up by the liver from mesenteric circulation and its excess is excreted in bile. Gastrointestinal cells take up a greater proportion of thyroid hormone when endogenous thyroid hormone is depleted (Hays MT 1988). 48-hour starvation experiments result in reduced thyroid hormones in plasma (DeGroot LJ, Coleoni AH 1977).

Participants of the Adventist Health Study—2 were analysed for a correlation with hypothyroidism and diet. The study showed a considerable portion of subjects, 5.79% of vegans, 6.2% of omnivores, and 8.3% of lacto/ovo vegetarians, were hypothyroid within the preceding 12 months (Tonstad S, Nathan E et al. 2011). This implies that adaptation to consuming more plants is still affecting a large portion of this plant-based population.

Ketogenic diets demonstrate a reduction in T3 and an increase in serum T4 (Lacovides S, Maloney SK et al. 2022). A Polish study of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis examined the effects of different diets in the management of the disease, over a two-year period. All those consuming the carnivorous diet had an improvement in their condition; showing no increase in lipid related illness compared to the other diets, nor did they suffer from gout or kidney related illness, which are often associated with increased red meat consumption (Ihnatowicz P, Wątor P et al. 2021).

15. Insulin

Metabolic differences in the consumed animal, influence the nutritional properties of it produce. Due to animal domestication, much of the World’s population have adapted to consuming herbivorous animals. Some countries allow hunting and consumption of carnivorous game, but due to the risk of parasitic infection, seafood is the most widely consumed carnivorous animal meat (Kadohira M Phiri BJ 2019).

Like discussed in part one (Sedley L 2025), injection or consumption of animal extracts used to treat disease was beginning to be explored in the late 19th century (The Hospital 1894). In 1889, complete removal of the dog’s pancreas resulted in severe and fatal diabetes. Researchers demonstrated the successful treatment of diabetes mellitus by feeding or injecting pancreatic extracts, but the consumption of the pancreas caused negative gastrointestinal discomfort, due to the concomitant presence of concentrated digestive enzymes (Banting FG, Best CH et al. 1922). It was noted that the removal of the pancreas caused disruptions due to the blood glucose: nitrogen ratio (Meting JV, Minkowski O 1890).

A cow fed different diets can have a blood insulin level ranging from 19.2 to 117 ug/ml and likely plays an important role in glucose homeostasis for animal consuming populations (Evans E, Buchanan-Smith JG et al. 1975) & (Jenny BF, Polan CE 1975). In contrast to the myocyte insulin receptors, the insulin receptors in the GIT do not promote the absorption of glucose (Macdonald RS, Thornton WH et al. 1993), but are still potent targets of insulin (Sodoyez- Goffaux F, Sodoyez JC et al. 1985). Insulin in the GIT promotes signalling via the MEK(ERK1/2) pathway, which regulates secretion of glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP), which stimulates insulin secretion by pancreatic beta cells via cross talk with the vagus nerve (Langlois A, Dumond A et al. 2022) & (Spreckley E, Murphy KG 2015). Blocking the activation of insulin receptors results in insulin resistance, and reduced GLP secretion (Lim GE, Huang GJ et al. 2009).

The new anti-obesity medication Ozempic, is a receptor agonist, that selectively binds the GLP-1 receptor, assisting in the body’s natural insulin synthesis (NovoMedLink 2025).

Meat hydrolysate and essential AA’s are the most powerful stimulators of the MEK(ERK1/2) pathway, and GLP secretion, in enteroendocrine cells (Reimer RA 2006). This demonstrates how important dietary meat constituents are in the regulation of insulin and glucose for populations who rely on a meat-based diet for sustenance. Moreover, it highlights how the timing of macronutrient consumption can be used to prevent glucose or insulin dysregulation.

16. Conclusions

This critical analysis reveals significant gaps in current nutritional guidelines. The complexity of dietetics is highlighted here by integrating biochemical processes with epigenetic mechanisms and evolutionary adaptations.

Part three of the critical analysis discusses arginine’s essential role in nitric oxide synthesis within Indigenous Australian diets, demonstrating unique metabolic advantages tied to higher arginine intake. Altitude adaptations provide compelling evidence of nitrate utilisation among highland populations, emphasising unique metabolic capacity. The discussion on nasal breathing connects the importance of nitric oxide production in sleep regulation and overall health.

Quantum biology offers promising avenues for understanding nitrogen metabolism at deeper levels, such as alternative energy pathways, like ammonium ion signalling, and reactive oxygen species.

Current evidence suggests, tyrosine metabolism influences melanin synthesis, thyroid hormone production, and neurological function. The study reveals that dietary shifts from carnivorous to plant-based diets reduce tyrosine intake by over 80%, potentially driving evolutionary skin lightening and metabolic changes in populations like Indigenous Australians. This reduction correlates with historical accounts of metabolic disturbances, including glycaemic dysregulation and ulcerations, observed during early dietary transitions in Australia.

Epigenetic regulation, further complicates tyrosine sufficiency, as evidenced by phenylketonuria (PKU) cases, where impaired tyrosine synthesis leads to neurological deficits, and hypopigmentation. These findings emphasize that standardised nutritional guidelines fail to account for population-specific adaptations to tyrosine metabolism, particularly in eumelanin-dominant groups with evolutionary reliance on high-tyrosine diets.

The fatty acid composition of the diet also influences epigenetic marks, with implications for mental health, neurological function, and overall well-being. Excessive intake of widely recommended plant sterols could pose health risks, highlighting the need for closer examination of their role in coronary artery disease.

Finally, Part three advocates for a focus on individual variability, environmental influences, and evolutionary history in nutritional care. These findings pave the way for advancements in personalised nutrition strategies that optimise health outcomes across diverse populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

References

- Antonini D, Sibilio A et al. (2013) An intimate relationship between thyroid hormone and skin: regulation of gene expression. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 4 . [CrossRef]

- Attia YA, Al-Harthi MA (2020) Protein and AA content in four brands of commercial table eggs in retail markets in relation to human requirements. Animals, 10(3) . [CrossRef]

- Banting FG, Best CH et al. (1922) Pancreatic extracts in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 12(3):141–146.

- Barsh GS, Ollmann MM et al. (2006) Molecular pharmacology of agouti protein in vitro and in vivo. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 885(1):143–152. [CrossRef]

- Battelli MG, Polito L et al. (2016) Xanthine oxidoreductase-derived reactive species: Physiological and pathological effects. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. [CrossRef]

- Bazak R, Elwany S et al. (2020) Nitric oxide unravels the enigmatic function of the paranasal sinuses: a review of literature. Egyptian Journal of Otolaryngology 36(1) . [CrossRef]

- Beall CM, Laskowski D et al. (2011) Pulmonary nitric oxide in mountain dwellers. Nature 414(6862):411–412.

- Berge KE, Tian H et al. (2000) Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science 290 (5497):1771–1775. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla C, Boxill LA et al. (2005) The 8818G allele of the Agouti Signaling Protein (ASIP) gene is ancestral and is associated with darker skin color in African Americans. Human Genetics, 116(5):402– 406. [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti M, Polito L et al. (2021) Xanthine oxidoreductase: One enzyme for multiple physiological tasks. Redox Biology, 41. [CrossRef]

- Carta G, Murru E et al. (2017) Palmitic acid: physiological role metabolism and nutritional implications. Frontiers in Physiology, 8.

- Chatkin JM, Qian W et al. (1999) Nitric oxide accumulation in the non-ventilated nasal cavity, Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery,125(6):682 . [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Yang G (2014) PPARs integrate the mammalian clock and energy metabolism. PPAR Research. [CrossRef]

- Choi HB, Gordon GRJ (2012) Metabolic Communication between Astrocytes and Neurons via Bicarbonate-Responsive Soluble Adenylyl Cyclase. Neuron 75(6):1094–1104.

- Clarke A, Pörtner HO (2010) Temperature, metabolic power and the evolution of endothermy. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 85(4):703-727 . [CrossRef]

- Crafa A, Calogero AE et al. (2021) The burden of hormonal disorders: a Worldwide overview with a particular look in Italy. Frontiers in Endocrinology, (Lausanne) 12. [CrossRef]

- Dai Z, Zheng W et al. (2022) AA variability tradeoffs and optimality in human diet. Nature Communications, 13(1) . [CrossRef]

- Dambrova M, Makrecka-Kuka M et al. (2022) Acylcarnitines: Nomenclature Biomarkers Therapeutic Potential Drug Targets and Clinical Trials. Pharmacological Reviews 74 (3):506–551 Pharmacological Reviews / Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. [CrossRef]

- Deem JD, Faber CL et al. (2022) AgRP neurons: regulators of feeding energy expenditure and behavior. The FEBS Journal, 289(8):2362–2381 . [CrossRef]

- DeGroot LJ, Coleoni AH (1977) Reduced nuclear triiodothyronine receptors in starvation-induced hypothyroidism. Endocrine Research, 79(1).

- De I, Sadhukhan S (2018) Emerging roles of DHHC-mediated protein s-palmitoylation in physiological and pathophysiological context. European Journal of Cell Biology, 97(5):319–338.

- Dib JR, Eugenia MF et al. (2011) A harsh life to indigenous proteobacteria at the Andean mountains: microbial diversity and resistance mechanisms towards extreme conditions, Repositorio Institucional Conicet Digital.

- Dietitian/Nutritionists from the Nutrition Education Materials Online “NEMO” team (Queensland Government) & (2021) Mediterranean-style die. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/nutrition Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Duan LP, Wang HH et al. (2006) Role of intestinal sterol transporters Abcg5 Abcg8 and Npc1l1 in cholesterol absorption in mice: gender and age effects. American Journal of Physiology—Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 290(2):G269–G276. [CrossRef]

- Editors at Food Standards Australia and New Zealand (2020) Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) Australian Food Composition Database. https://www,foodstandards,gov,au/science/monitoringnutrients/afcd/Pages/foodsbynutrientsearch,a spx, Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Editors at Nutrition Australia (2013) Nutrition Australia. Australian Dietary Guidelines.

- Editors of IDIDJ Australia (2023) IDIDJ Australia. Didgeridoo History and Timeline. https://www.ididj.com.au/didgeridoo-history/.

- Evans E, Buchanan-Smith JG et al. (1975) Glucose metabolism in cows fed low— and high— roughage diets. Journal of Dairy Science, 5(5):672–677. [CrossRef]

- Ferriè J (2004) Coronary disease The French Paradox: Lessons from other countries. Heart 90.

- Glasse H (1747) The art of cookery made plain and easy.

- Gooley JJ, Chua ECP (2014) Diurnal regulation of lipid metabolism and applications of circadian lipidomics. Journal of Genetics and Genomics, 41(5):231–250y . [CrossRef]

- Grippaudo C, Paolantonio EG et al. (2016) Association between oral habits mouth breathing and malocclusion. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica, 36(5):386–394. [CrossRef]

- Guenter Schwarz C, Kohl JB et al. (2019) Homeostatic impact of sulfite and hydrogen sulfide on cysteine catabolism. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176 554. [CrossRef]

- Jenny BF, Polan CE (1975) Postprandial blood glucose and insulin in cows fed high grain. Journal of Dairy Science, 5(4):512–514.

- Hays MT (1988) Thyroid hormone and the gut. Endocrine Research, 14(2–3):203–224. [CrossRef]

- Hess JM (2022) Modeling dairy-free vegetarian and vegan USDA food patterns for non-pregnant nonlactating adults. The Journal of Nutrition, 152(9):2097–2108. [CrossRef]

- Hicks CS (1963) Climatic adaptation and drug habituation of the central Australian Aborigine. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 42 39–57.

- Hida T, Kamiya T et al. (2020) Elucidation of Melanogenesis Cascade for Identifying Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Approach of Pigmentary Disorders and Melanoma. International Journal of Medical Students, 21(17):6129.

- Hocquette J F (2004) Analogies for understanding statistics. American Journal of Physiology , 28(3):124–125.

- Horiuchi M, Fukuoka Y (2017) Measuring the Energy of Ventilation and Circulation during Human Walking using Induced Hypoxia. Scientific Reports, 7(1) . [CrossRef]

- Horscroft JA, Kotwica AO et al. (2017) Metabolic basis to sherpa altitude adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(24):6382–6387. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Tang C et al. (2016) Endogenous sulfur dioxide: A new member of gasotransmitter family in the cardiovascular system. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. [CrossRef]

- Kadohira M, Phiri BJ (2019) Game meat consumption and foodborne illness in Japan: a web- based questionnaire survey. Journal of Food Protection, 82(7):1224–1232. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa M (2000) KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research, 2(1):27–30. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa M (2019) Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Science, 2(11):1947–1951. [CrossRef]

- Kempf E, Landgraf K et al. (2022) Aberrant expression of agouti signaling protein (ASIP):as a cause of monogenic severe childhood obesity. Nature Metabolism, 4 1697-1712.

- Kim SY, Kim BM et al. (2014) Effect of steaming blanching and high temperature/high pressure processing on the AA contents of commonly consumed Korean vegetables and pulses. Preventative Nutrition in Science 19(3):220–226.

- Kommissionen for Ledelsen af de Geologiske og Geografiske Undersøgelser i Grønland, Meddelelser om Grønland (1915) København C, A, Reitzels Forlag 49.

- Ihnatowicz P, Wątor P et al. (2021) Are nutritional patterns among polish hashimoto thyroiditis patients differentiated internally and related to ailments and other diseases? Nutrients, 13(11) . [CrossRef]

- Irwin D (1830) The housewife’s guide or an economical and domestic art of cookery. William Mason, London.

- Ito H, Kikuzaki H et al. (2019) Effects of cooking methods on free AA contents in vegetables. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology, (Tokyo) 65.

- Lacovides S, Maloney SK et al. (2022) Could the ketogenic diet induce a shift in thyroid function and support a metabolic advantage in healthy participants? A pilot randomized-controlled- crossover trial. Public Library of Science: One, 17 . [CrossRef]

- Lang JA (2020) Thermoregulation in the heat: not so black and white. Experimental Physiology, 105(1):1–2. [CrossRef]

- Leal RB, Gomes MC et al. (2016) Impact of breathing patterns on the quality of life of 9- to 10- year-old school children. American Journal of Rhinology and Allergy, 30(5):e147–e152 . [CrossRef]

- Lee YC, Lu CT et al. (2022) The impact of mouth-taping in mouth-breathers with mild obstructive sleep apnea: a preliminary study. Healthcare (Switzerland):10(9).

- Lee Y, Wisor JP (2022) Multi-modal regulation of circadian physiology by interactive features of biological clocks. Biology (Basel) 11(1) . [CrossRef]

- Lerchundi R, Fernández-Moncada I et al. (2015) NH4+ triggers the release of astrocytic lactate via mitochondrial pyruvate shunting. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, (35):11090–11095. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Barry EL et al. (2017) Effects of supplemental calcium and vitamin D on the APC/β-catenin pathway in the normal colorectal mucosa of colorectal adenoma patients. Molecular Carcinogenesis, 56(2):412– 424. [CrossRef]

- Langlois A, Dumond A et al. (2022) Crosstalk communications between islets cells and insulin target tissue: the hidden face of iceberg. Frontiers in Endocrinology (Lausanne), 13. [CrossRef]

- Lim GE, Huang GJ et al. (2009) Insulin regulates glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from the enteroendocrine L cell. Endocrinology 150(2):580–591. [CrossRef]

- Listrat A, Lebret B et al. (2016) How muscle structure and composition influence meat and flesh quality. Scientific World Journal, 2016 . [CrossRef]

- Lundberg JON, Settergren G et al. (1996) Inhalation of nasally derived nitric oxide modulates pulmonary function in humans. Acta Physiologica Scandinavia, 15(4):343–347. [CrossRef]

- Macdonald RS, Thornton WH et al. (1993) Insulin and IGF-1 receptors in a human intestinal adenocarcinoma cell line (Caco-2) regulation of Na + glucose transport across the brush border. Journal Receptor Research, 13(7):1093–1113.

- Mantzioris E, Villani A (2019) Translation of a Mediterranean-style diet into the Australian Dietary Guidelines: a nutritional ecological and environmental perspective. Nutrients, 11(10):2507 . [CrossRef]

- Matthews DE (2007) An overview of phenylalanine and tyrosine kinetics in humans 1,2. The Journal of Nutrition,137(6).

- McNulty JC, Jackson PJ et al. (2005) Structures of the agouti signaling protein. Journal of Molecular Biology, 346(4):1059–1070 . [CrossRef]

- Meting JV, Minkowski O (1890) Diabetes mellitus After Pancreatic Resection, Archives of Experimental Pathology, 26 371–387.

- More VR, Campos CR (2017) PPAR-α a lipid-sensing transcription factor regulates blood–brain barrier efflux transporter expression. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, 37(4):1199–1212. [CrossRef]

- Morgan AM, Lo J et al. (2013) How Does Pheomelanin Synthesis Contribute to Melanogenesis? Two Distinct Mechanisms Could Explain the Carcinogenicity of Pheomelanin Synthesis. BioEssays 35(8):672–676 . [CrossRef]

- Morgan J (1979) The life and adventures of William Buckley. ANU Press.

- Nakamura H, Utsunomiya A, Ishida Y, Horita T (2020), Thiamine Deficiency in a Nondrinker and Secondary Pulmonary Edema after Thiamine Replenishment. Internal Medicine. Feb 1;59(3):373-376. [CrossRef]

- NovoMedLink. (2025) Consumer CMI for adults with T2D: Once-weekly Ozempic® (semaglutide) injection mechanism of action. Retrieved from https://www.novomedlink.com/diabetes/products/treatments/ozempic/about/mechanism-of-action.html.

- Palomer X, Barroso E et al. (2018) PPARβ/δ: a key therapeutic target in metabolic disorders. International Journal of Medical Students, 19(3):913.

- Popeijus HE, van Otterdijk SD et al. (2014) Fatty acid chain length and saturation influences PPARα transcriptional activation and repression in HepG2 cells. Molecular Nutrititional Food Research, 5(12):2342-9.

- Puhan MA, Suarez A et al. (2005) Didgeridoo playing as alternative treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal, 332(7536) 266–270. [CrossRef]

- Qasimi MI, Nagaoka K et al. (2017) The effects of phytosterols on the sexual behavior and reproductive function in the Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) Poultry Science, 96(9):3436– 3444 . [CrossRef]

- Quagliariello A, Di Paola M et al. (2019) Gut microbiota composition in Himalayan and Andean populations and its relationship with diet lifestyle and adaptation to the high-altitude environment. Journal Anthropological Science, 97 189–208.

- Rangroo Thrane V, Thrane A S et al. (2013) Ammonia triggers neuronal disinhibition and seizures by impairing astrocyte potassium buffering. Nature Medicine, 19(12): 1643–1648. [CrossRef]

- Recinto C, Efthemeou T et al. (2017) Effects of nasal or oral breathing on anaerobic power output and metabolic responses. International Journal of Exercise Science, 10(4).

- Resh MD (2016) Fatty acylation of proteins: The long and the short of it. Progress in Lipid Research, 63 120– 13.

- Reimer RA (2006) Meat hydrolysate and essential amino acid-induced glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion in the human NCI-H716 enteroendocrine cell line is regulated by extracellular signal- regulated kinase1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Journal of Endocrinology, 191(1):159–170. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro GCA, dos Santos ID et al. (2016) Influence of the breathing pattern on the learning process: a systematic review of literature. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, 82(4):466–478 . [CrossRef]

- Ruth A (2015) The health benefits of nose breathing. Nursing in General Practice.

- Sandalio LM, Rodríguez-Serrano M et al. (2013) Role of Peroxisomes as a Source of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) signalling molecules. Subcellualar Biochemistry, 231–255 . [CrossRef]

- Sano M, Sano S et al. (2013) Increased oxygen load in the prefrontal cortex from mouth breathing: A vector-based near-infrared spectroscopy study. NeuroReport, 24(17):935–940. [CrossRef]

- Sedley, L. (2020). Advances in nutritional epigenetic a fresh perspective for an old idea; lessons learned limitations and future directions. Epigenetics Insights, 13. [. [CrossRef]

- Sedley, L (2025) A Critical Analysis of Dietetics—Part 1: Elemental Ratios, Sulphur, and Nitrogen (Preprint).

- Sedley, L (2025) A Critical Analysis of Dietetics—Part 2: A Critical Analysis of Dietetics—Part 1: Elemental Ratios, Carbon, Oxygen, Hydrogen and Body Composition (Preprint).

- Sedley, L (2023). Epigenetics. In T. G. Dinan (Ed.), Nutritional Psychiatry: A Primer for Clinicians, pp. 172-211 Cambridge University Press.

- Sedley, L (2025). Illuminating the Connection: Breastfeeding, Lactose Intolerance, and Early Life Disease Prevention. Preprints, 2025030262. [CrossRef]

- Segrest JP, Tang C et al. (2022) ABCA1 is an extracellular phospholipid translocase Nature Communications, 13(1):4812. [CrossRef]

- Shane B (2011) Folate status assessment history: Implications for measurement of biomarkers in NHANES. American Journal of Clininical Nutrition, 94(1):337S-342S.

- Sharma M, Singh K et al. (2020) Estrogen receptor (ESR1 and ESR2)-mediated activation of eNOS–NO–cGMP pathway facilitates high altitude acclimatisation. Nitric Oxide 102 12–20 . [CrossRef]

- Simmons A (1796) American cookery or the art of dressing viands fish poultry and vegetables. Hudson Goodwin, Hartford.

- Sinha S, Singh SN et al. (2009) Total antioxidant status at high altitude in lowlanders and native highlanders: role of uric acid. High Altitude Medical & Biology, 10(3):269–274.

- Sodoyez-Goffaux F, Sodoyez JC et al. (1985) Insulin receptors in the GIT of the rat fetus: quantitative autoradiographic studies. Diabetologia 28.

- Spengler CM, Czeisler CA et al. (2000) An endogenous circadian rhythm of respiratory control in humans. Journal of Physiology 526(3):683–694.

- Sriperm N, Pesti GM et al. (2011) Evaluation of the fixed nitrogen-to-protein (N:P) conversion factor (6,25) versus ingredient specific N:P conversion factors in feedstuffs. Journal of the Science of Food Agriculture, 91(7):1182– 1186 . [CrossRef]

- Tada H, Nohara A et al. (2018) Sitosterolemia hypercholesterolemia and coronary artery disease. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis, 25(9):783–789.

- The Hospital (1894) The treatment of disease by animal extracts. Hospital (Lond 1886)15(386):345.

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2014) Mediterranean diet: reducing cardiovascular disease risk. Available via: https://www.racgp.org.au Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- Thomas DD (2015) Breathing new life into nitric oxide signaling: A brief overview of the interplay between oxygen and nitric oxide. Redox Biology, 5 225–233 . [CrossRef]

- Tonstad S, Nathan E et al. (2011) Vegan diets and hypothyroidism. Nutrients, 5(11):4642–4652 . [CrossRef]

- US Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service—Nutrient Data Laboratory (2015) Composition of foods raw processed prepared. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference 2016.

- Veeranki S, Tyagi SC (2015) Role of hydrogen sulfide in skeletal muscle biology and metabolism. Nitric Oxide 46 p66–71 . [CrossRef]

- Williams RA, Mamotte CD et al. (2008) Mini-review phenylketonuria: an inborn error of phenylalanine metabolism. Clinical Biochemist Reviews, 29.

- Yu S, Wang G et al. (2019) Association of a novel SNP in the ASIP gene with skin color in black- bone chicken. Animal Genetics, 50(3):283–286.

- Zolghadri S, Bahrami A et al. (2019) A comprehensive review on tyrosinase inhibitors. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition of Medical Chemistry, 34(1):279.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.F |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).